ABSTRACT

Unobserved heterogeneity causing overdispersion and the excessive number of zeros take a prominent place in the methodological development on count modeling. An insight into the mechanisms that induce heterogeneity is required for better understanding of the phenomenon of overdispersion. When the heterogeneity is sourced by the stochastic component of the model, the use of a heterogenous Poisson distribution for this part encounters as an elegant solution. Hierarchical design of the study is also responsible for the heterogeneity as the unobservable effects at various levels also contribute to the overdispersion. Zero-inflation, heterogeneity and multilevel nature in the count data present special challenges in their own respect, however the presence of all in one study adds more challenges to the modeling strategies. This study therefore is designed to merge the attractive features of the separate strand of the solutions in order to face such a comprehensive challenge. This study differs from the previous attempts by the choice of two recently developed heterogeneous distributions, namely Poisson–Lindley (PL) and Poisson–Ailamujia (PA) for the truncated part. Using generalized linear mixed modeling settings, predictive performances of the multilevel PL and PA models and their hurdle counterparts were assessed within a comprehensive simulation study in terms of bias, precision and accuracy measures. Multilevel models were applied to two separate real world examples for the assessment of practical implications of the new models proposed in this study.

KEYWORDS: Multilevel modeling, count data, overdispersion, zero-inflation, Poisson–Lindley distribution, Poisson–Ailamujia distribution

1. Introduction

Count modeling literature has long been engaged with various modifications of conventional Poisson regression to account for high overdispersion. Such extensions proposed are all tailored to accomodate the possible sources of the extra dispersion at hand. Zeros in excess to what can be expected constitute a part in this problem and the zero-modified generalized linear models appear to be viable solutions. One of the two forms, zero-inflated (ZI) or hurdle, is usually preferred depending on the underlying mechanisms that produce either structural or sampling zeros (also known as random zeros). Structural zero is the value of an outcome that is always zero due to the existence of a subgroup within the sample under consideration that are not at risk for that outcome. Sampling zero is observed as zero in the current sample, but instead could possibly be a positive count. In contrast to ZI models which involve both types of zeros, hurdle models assume that all zero data come from one ‘structural’ source [29,54]. It is known as the two-part model with one part being binary for modeling whether the outcome is zero or positive, and the second part for modeling the positive counts through a truncated model, such as a truncated Poisson. A hurdle model is also frequently referred as being an advantageous tool to accomodate the underdispersion as well as the overdispersion [51].

Additional to the comprehension about excess zeros, one needs to reach a greater understanding of what factors induce the unobserved heterogeneity in order to justify the overdispersion properly. Heterogeneity in the data falls into two classes as ‘observed’ and ‘unobserved or hidden’ heterogeneity. As far as generalized linear models (GLMs; [48]) are concerned, observed heterogeneity is directly related to how the systematic part of the model is constructed. Failure to capture the full systematic structure in the data also looks like an excess variation around the fitted values, which create a misleading impression of overdispersion. Omitted predictors and incorrect functional forms specified for the conditional means are mainly responsible for this result and there is not an all set solution rather than repeating the modeling process by including the omitted variables or trying other functional forms. Therefore it must be emphasized that the true definition of the overdispersion is the excess variation when the systematic structure of the model is correctly specified [8].

In practice, empirical data generally exhibit overdispersion as a consequence of unobserved heterogeneity which is solely related to the stochastic component of GLMs. Random variation around the conditional expectation give the implication of unobserved heterogeneity that is absorbed within the residual variance. If the stochastic distribution, like Poisson, fails to adequately control for unobservable effects as the cause of outlying observations, sampling errors or non-homogenous populations, severe bias in the parameter estimates or misleading inferences become inevitable [47]. A viable precaution against this result is to change the restrictive Poisson form to a more flexible one through the inclusion of additional parameters that can generate overdispersion. The compounding method, proposed by Greenwood and Yule [24], appears handy in addressing this solution. The most famous example is Negative Binomial distribution which is obtained by compounding Poisson with Gamma distribution (also termed as Poisson–Gamma mixture). In the literature, compounding Poisson with some lifetime distributions has also attracted attention with the aim of evaluating the enlarged complexities of real world problems. An earliest example of this trend is the discrete Poisson–Lindley (PL) distribution obtained by using Lindley as the mixing distribution [59]. The most recent attempt is performed by compounding Poisson with Ailamujia lifetime distribution, resulting Poisson–Ailamujia (PA) model [27]. Assessment of their various properties have promoted the use of PL and PA mixture models in addressing the unobserved heterogeneity and they are worthwhile alternatives to NB model [22].

Various concerns of the count modeling mentioned so far is the matter of subjects at a single level. However, count data frequently present multilevel nature as a consequence of clustering subjects within two or higher-level units (e.g. hospitals) in longitudinal, repeated measures or hieararchical studies. Any counted feature of, for example, patients nested within hospitals, residents within regions, employees within companies etc. present inherent correlation structures. Possible association between subjects within the same group or cluster render the single-level Poisson (or its modified forms) inappropriate due to the violation of the assumption of independence in events that constitute counts. It must be emphasized that ignorance of this lack of independence also amplifies the problem of overdispersion. Although the generalized linear modeling framework is quite satisfactory to model the most of the mechanisms producing single level count data, it fails to address correlated counts of hierarchical study design. This deficiency has therefore created an avenue for the development of new strategies for the multilevel count data in the literature.

The usual attitude is to extend GLM by the inclusion of cluster-specific or observation-specific random parameters that account for the dependency by partitioning the total variance as between-cluster variation and within-subjects variation. Typical way of achieving this is to fit a conventional generalized linear mixed model (GLMM; [49]) that estimates the variation on the covariation of intercepts and slopes across clusters or individual subjects. The intercept-only model is one of the most basic GLMMs which does not contain any explanatory variable. This model is particularly useful to determine whether the hierarchical analysis of the data is necessary. The random intercept model (containing cluster-specific random intercept parameters) is an extension of the intercept-only model that can be used to account for the unobserved heterogeneity in the overall response. In this model, the intercept is the only random effect meaning that the clusters differ with respect to the average value of the response variable, but the relation between predictors and the response variable cannot differ between clusters [15,21]. The model assumes that the slopes (stated otherwise the effects of explanatory variables) are fixed, namely, they do not vary across the groups of observations (or for each individual observation). Lamarche et al. [38] have introduced an approach using conditional quantile functions in conjunction with models containing individual-specific random intercepts (and fixed slopes) for analyzing zero-inflated count responses in longitudinal data. Anastasopoulos [6] has investigated the unobserved heterogeneity across the individual observations when estimating accident injury-severity rates and frequencies on roadway segments. The author has proposed a new multivariate approach on tobit and zero-inflated models in which observation-specific random parameters are allowed to vary across the injury-severity rates and frequencies using a simulation-based maximum likelihood method for estimation [7,10,50]. Bhowmik et al. [12] have developed a hybrid model framework using two different studies [11,70] to inspect the zonal crash counts of different types with individual-specific random parameters by applying a similar simulation-based maximum likelihood method for estimation [9,17]. Two types of multilevel models with cluster-specific random parameters are used in the simulations and applications presented in this study: (1) the random intercept model containing random intercept and fixed slope parameters (see Example 1) and (2) the random slope model containing random intercept and random slope parameters (see Example 2). Since the data are random across the groups of observations in the data, the second model is called a slope-varying multilevel model in this study in line with the terminology used in Hox [33]. It is also called the model with grouped random parameters in the literature [2,55,63].

As possible sources of overdispersion; excessive number of zeros, unobserved heterogeneity and clustering induced association present special challenges in their own right and treatment of each creates a separate strand of statistical modeling strategy. Most of the modified models deal with one or two additional sources of overdispersion. However, all the features listed above may occur simultaneously in one single study, which further compound the issue of model fitting. Such a challenge has been undertaken within the generalized linear mixed modeling framework, however, predominantly via multilevel zero-inflated Poisson models for counts of particularly longitudinal studies [26,35,36,40,71,74]. Although gaining momentum in the recent years, compelling challenge of this kind for hurdle models has received less attention. It is important to distinguish between the multilevel ZI and multilevel hurdle models, as they conceptualize the excess zeros in the data differently. The multilevel ZI models conceptualize the excess zeros as either sampling or structural zeros, whereas the multilevel hurdle models consider them only as structural zeros. The two types of models produce nearly identical results if the mechanisms generating the sampling and structural zeros in the data are not significantly different from each other [19]. This study examines the multilevel hurdle models, since these models are investigated less in the literature in comparison to their zero-inflated counterparts. These models are also advantegous over the ZI models as they can deal with both the underdispersion and overdispersion in the data [51]. Moreover, the hurdle models can be used not only for the zero-inflation in the data, but also for the zero-deflation, where the ZI models yield biased results [19]. The model of multilevel hurdle Poisson is first raised by Min and Agresti [51] and analytical aspects of model fitting via h-likelihood are discussed by Molas and Lesaffre [52], a marginalized modeling framework is developed for both ZI and hurdle models by Kassahun et al. [37]. Besides, no matter whether zero-inflation is addressed by ZI or hurdle models, overdispersion due to unobserved heterogeneity in the counts is accomodated by the replacement of Poisson with only Negative Binomial in limited number of real world applications [34,41,72,73].

The objective of this study is therefore to merge the attractive features of the recently developed two heterogenous Poisson distributions, namely Poisson–Lindley (PL) and Poisson–Ailamujia (PA) for multilevel count data inflated by structural zeros. The PL and PA distributions are more flexible than the usual Poisson distribution which assumes that the mean and variance of the data are equal to each other (also known as the assumption of equi-dispersion). Therefore, these distributions provide more accurate parameter estimates and their standard errors in comparison to the Poisson distribution when the data contain the problem of overdispersion. Moreover, their distributional forms are not complicated as both of them are one-parameter distributions. However, inclusion of these two new distributional forms complicates the model fitting process and derivation of model parameters is less than straightforward. Therefore, the novelty of this study also stems from the approach undertaken here which is the customizing the link function adapted from the work of Akdur [5]. To estimate the model parameters in GLMMs, maximum marginal likelihood method was used with the numerical integrations over random effects using both Laplace and adaptive Gaussian-Hermite quadrature algorithms. The distribution of random effects are here assumed to be normal according to general consensus [33,55,64,67]. The relevance of the choice to use normally distributed random effects has been evaluated and confirmed for two main reasons: (1) Most of the procedures in standard softwares (e.g. R, SAS, MPlus, Python etc.) use normally distributed random effects as the default option to account for the variation across clusters or individual observations. Many of these procedures do not even provide flexibility to replace normally distributed random effects with the effects following another distribution. Therefore, for practical reasons, it is more plausible to use normally distributed random effects to simplify the procedure for parameter estimation using standard softwares. (2) Since the multilevel modeling with normally distributed random effects has been well-researched, the possible problems that may be encountered in the case of using these random effects [25,28,44,45] and solutions to these problems [1,18,20,32,39,68] can be anticipated based on the results of previous studies. More caution and care should be taken when using non-normally distributed random effects (e.g. uniform, gamma, beta, Weibull etc.), as less research has been conducted to analyze variation between groups or individual observations using these effects.

The outline of the present study is therefore as follows: Next section gives the formal definitions of Poisson–Lindley (PL) and Poisson–Ailamujia (PA) distributions. Multilevel forms (MPL and MPA) are also constructed here by incorporating random effects to the linear predictor. Then, the models are extended to hurdle expression by the assignment of the new distributional forms to the truncated part of the model (MPLH and MPAH). Following section evaluates the parameter estimation process via both Laplace and adaptive Gaussian–Hermite quadrature algorithms for comparative purposes. Four comprehensive simulation settings each of which generate MPA, MPL, MPAH and MPLH models are conducted in order to assess their performances in terms of bias, precision and accuracy measures. The examples section demonstrates applications of random intercept and random slope models on two separate real world examples for the assessment of practical implications of the new heterogeneous Poisson hurdle models proposed in this study. The paper is then finalized by the discussion of the results and future developments.

2. The MPL and MPA models

The PL and PA distributions are two examples of compound Poisson distribution that can be used to cope with the problem of overdispersion for count data. The definition of the probability mass function (pmf) of the PL distribution [59] is

| (1) |

where , .

The pmf of the PA distribution [27] is given by

| (2) |

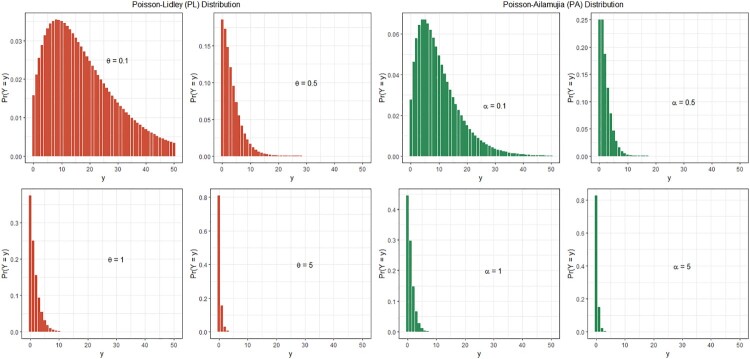

where , . Figure 1 shows the plots for the pmfs of PL and PA distributions with varying values of θ and α, respectively. As can be seen from this figure, both PL and PA distributions become positively skewed with increasing values of θ and α parameters, respectively.

Figure 1.

The pmf plots of PL and PA distributions with different values of θ and α.

The models depending on these distributions are special cases of the family of GLMs for count data which is defined as

| (3) |

where is the mean for the ith observation of outcome, is the ith row of the design matrix containing predictors in the model and is the vector of model parameters for . The log link function is used to relate to the linear predictor, . The functional characteristic of mean vector μ depends on the underlying distribution for the model under evaluation. That is, for the Poisson model, for the PL model [62, p. 104], and for the PA model [27, p. 104].

The PL and PA models are only appropriate to analyze non-clustered (stated otherwise single level) data, and thus, do not perform well for overdispersed data sets with two-level hierarchical structure in which subjects of lower-level are nested within a higher-level (e.g. people are grouped in terms of their political parties and nationalities or multiple measurements are assessed on individuals at different time points). It is therefore necessary to modify PL and PA models to incorporate the unobservable effects of various levels. It must be noted that development of multilevel form of PL and PA (i..e, MPL and MPA) models is the first attempt here and achieved by incorporating random effects to the linear predictor. The generalized linear mixed modeling framework is best suited for this purpose and is defined for count data as

| (4) |

where and are the ith row of design matrix in the jth group in the fixed and random parts, respectively, for and . The design matrix in the random part contains the values of predictors whose effects on the outcome are allowed to vary across J groups of observations (not for each individual observation). This variation has been taken into account by the vector of random effects from a multivariate normal distribution with mean vector 0 and covariance matrix Σ, that is, .

If the model under consideration is an (only) intercept-varying model where , these J random intercepts, that is, the 's, are at the group (stated otherwise cluster) level and they are normally distributed with a mean of zero and a variance of , that is, . However, if the model additionally contains a set of random slopes (i.e. 's) where , then these cluster-level random effects follow a multivariate normal distribution with mean vector zero and covariance matrix:

where represents the covariance between the random effects and . Note that, the random effects are often assumed to be independent from each other, that is, . The influences of these effects on the outcome are allowed to vary across the J groups:

| (5) |

where is the cluster-specific vector of random effects, is the vector of means for the random effects, and contains the cluster-level residuals with and for . Notably, since and in the vector of means are fixed values, and .

The MPL and MPA models are suitable for analyzing data sets containing sampling zeroes, but they are not appropriate when the data consist of true (stated otherwise structural) zeroes. The multilevel hurdle models are used to take the true zeroes into account when analyzing hierarchical data structures. A hurdle model is composed of two sub-models such that binary model measures whether the outcome falls below or above the hurdle and truncated model explains the non-zero outcomes. With such a modeling process, these models are more flexible than their usual counterparts not only for the overdispersed data with excess zeroes but also for the underdispersed data with too few zeros. This study therefore proposes two new multilevel hurdle models for count data, namely, the multilevel Poisson–Lindley hurdle (MPLH) and the multilevel Poisson–Ailamujia hurdle (MPAH) models which are elaborated in the next section.

3. The MPLH and MPAH models

The MPLH and MPAH models depend on the multilevel hurdle power series distribution which is defined as

| (6) |

where η denotes the parameter vector, is the value of outcome, is the binary part containing the probability of attaining a structural zero and is the truncated part containing the non-zero count for the ith observation in the jth group ( and ). Table 1 displays the components of the multilevel hurdle power series distribution for the MPH, MPLH and MPAH models, respectively. Notably, for the multilevel hurdle models presented in this paper, the parameter vector η contains only one parameter, that is, for the MPH model, for the MPLH model and for the MPAH model.

Table 1.

The components of the multilevel hurdle power series distribution for the MPH, MPAH and MPLH models.

The multilevel hurdle models presented in this paper using the power series distribution in (6) above are of the form

and

| (7) |

where the first part models the structural zeroes and the second part, involving fixed and random effects, models the non-zero (stated otherwise truncated at zero) counts. Logit link function in the first part relates 's to the linear predictor, and thus, . Here, is the ith row of the design matrix for the jth group containing the values of predictors in the logit model and is the corresponding vector of model parameters. The second part is analogous to expression given in (4) which is a special case of GLMMs, namely, mixed truncated at zero count model. That part relates the mean for the ith observation in the jth group to the linear predictor containing fixed and random parts for and .

Expert knowledge is an ideal solution when deciding on the choice of proper sets of predictors in the logit and truncated count components of multilevel hurdle models. However, it is often difficult to access this resource for methodological studies like this one. Many researchers use simple (but ad-hoc) solutions when choosing the predictors in the model. For example, some researchers use full (stated otherwise saturated) models to account for all possible relationships between the outcome and predictors in the model, while others remove predictors causing high multicollinearity from the model. Both of these techniques are often considered inadequate research practices in the literature because saturated models often suffer from the problem of overfitting, and removing a relevant predictor from the model may result in obtaining bias parameter estimates [53]. Variable selection methods such as Stepwise regression [16,30] and Lasso regression [60,66] can be used to obtain a reasonable set of predictors in the model. As will be elaborated in the real life applications, a simple strategy using Backward stepwise regression technique is followed in this study to determine the sets of predictors in the multilevel (hurdle) models.

4. Parameter estimation via laplace and AGQ approximations

We use the R package glmmAdaptive to estimate model parameters and their standard errors by customizing the link function depending on the two-level model under evaluation. This package implements two well known numerical integration approaches for estimation, that are, Laplace approximation and Adaptive Gauss-Hermite quadratures approach (AGQ). Both methods aim to maximize a full marginal likelihood function which contains multiplications of integrals over the J groups for the hierarchical data structures. The full marginal likelihood function is defined as

| (8) |

where is the conditional distribution of outcome for the jth group, , given and β. Besides, is the distribution of q-dimensional (latent) 's which are assumed to follow a multivariate normal distribution with mean vector 0 and covariance matrix Σ.

In the sequel, the formulations of and are first introduced for the MPA model. Similar functions can also be formulated for the MPL, MPLH and MPAH models which are not presented here, but, would be available upon request. Then, we explain how to obtain the marginal likelihoods used in Laplace and AGQ methods to approximate the full marginal likelihood function in (8). To clarify the framework of GLMMs for the MPA model, we benefit from the formulations presented in Akdur [5] and Rizopoulos [58].

The conditional distribution of given and β for the MPA model is

| (9) |

where is the conditional mean for the ith observation in the jth group. The probability density function of 's with mean vector zero is given by

| (10) |

where Σ is the positive-definite covariance matrix of q-dimensional random effects. Therefore, the integral in (8) for the jth group can be defined as

| (11) |

where [5, p. 4]. The function for the MPA model is provided by

| (12) |

Both the Laplace and AGQ approximations of the integral in (8) involve the first and second derivatives of function with respect to random effects which are described below:

| (13) |

Both approximations implemented in the package glmmAdaptive utilize a set of empirical Bayes estimates (i.e. 's) to maximize . Calculating the minus inverse of the second derivative of with respect to and replacing with results in the marginal likelihood function used in Laplace approximation which is defined as

| (14) |

where . The corresponding log likelihood function is given by

| (15) |

Increasing the quadrature points in each integral presented in (8) increases not only the accuracy in parameter estimates, but also the computation time. Thus, there is a tradeoff between accuracy in estimation and computational efficiency. The Laplace approximation uses only one quadrature point for each integral in (8), and thus, it is often computationally efficient. However, because of the same reason it is prone to produce less reliable estimates than the AGQ approximation which enables the use of multiple quadrature points in the integrations.

Let 's are normally distributed random effects with mean vector 's and covariance matrix for which the Kernel function is defined as

| (16) |

where 's are the empirical Bayes estimates and with I being the identity matrix. Based on Pinheiro and Bates [56], the marginal likelihood function used in AGQ approximation is defined as

| (17) |

where ( and ) is the weight of the mth quadrature for the kth random effect and

with .

5. Simulation studies

In this section, we conduct four comprehensive simulation studies in each of which the data are generated according to the MPL, MPA, MPLH and MPAH models, respectively. In each of the simulation studies, the data sets are generated in line with one of these models and its corresponding probability mass function. The performance of each model is evaluated in terms of bias, precision and accuracy measures given in Walther and Moore [69]. In each of these simulations we generate 1000 independent data sets for an intercept-varying multilevel model since the use of a slope-varying multilevel model in the simulations substantially increases the computational time especially for data sets containing large numbers of groups and observations in these groups. We used the integration approach AGQ in estimating model parameters with nAGQ=7 which is one of the default number of quadrature points in the R package glmmAdaptive. Sometimes when the number of groups is only 10 and the number of observations in these groups are small (i.e, or 30), we receive an error message indicating that the model under evaluation does not converge. In such cases, we discard the corresponding loop runs from the study and continue the simulation until achieving successfully converged 1000 trials.

We first set the population values of β's for each model as . In line with Maas and Hox [46], we set set the number of groups as J=10,30,50 or 100; the number of observations in each group as , 30 or 50; and the population value of the variance for the random intercept as , 0.11 or 0.18. The design matrix contains the values of two continuous predictors and and one dummy predictor . The values of and are generated from the standard normal distribution. Note that these predictors are independent from each other in the simulation and standardization is still required to ensure that they have a mean value of zero and standard deviation of one. The values of are generated such that the success probability, that is, the probability of obtaining one against zero, is 0.5. The values of random-intercept of size J are generated from normal distribution with a mean of zero and a variance of and these values are repeated times for each group for . Note that grand mean centering, that is, , is required after repeating 's times for each group to ensure that they have a mean of zero. The values of mean vector which is the exponentiated linear predictor are calculated using the population values of β's, the design matrix and the values of random-intercept , that is, for and . Notably, the design matrix in the random part contains only ones in this case as the model under consideration is an intercept-varying model, but not a slope-varying model. The values of mean vector are used to calculate the values of θ in the MPL model, that is, and the values of α in the MPA model, that is, for and . Then, the corresponding pmfs in (1) and (2) are utilized to generate the values of outcomes. We use the Runuran package in R [43] to generate the values of outcomes based on the corresponding pmfs which implements the method of discrete automatic rejection inversion (DARI) presented in Hörmann et al. [31]. Finally, the AGQ integration method with nAGQ=7 quadrature points is used to estimate model parameters and their standard errors.

The multilevel hurdle models bifurcated into two parts for the non-zero counts and structural zeroes. The above procedure applies to the non-zero counts in these models. Therefore, for only the MPLH and MPAH models in the study, the structural zeroes are modeled using a logit link function. We first set the population values of γ's as . In the simulations, we use the same design matrices in the logit model for the structural zeroes and the fixed part of the log model for the non-zero counts, and thus, . Therefore, creating predictors in applies analogously to that in . Then, the binary part containing the probabilities of obtaining structural zeroes is attained using the logit link function by . These probabilities are used to generate the dummies in the logit part which are in turn multiplied by the non-zero counts obtained in the log model to obtain the values of outcomes in the MPLH and MPAH models.

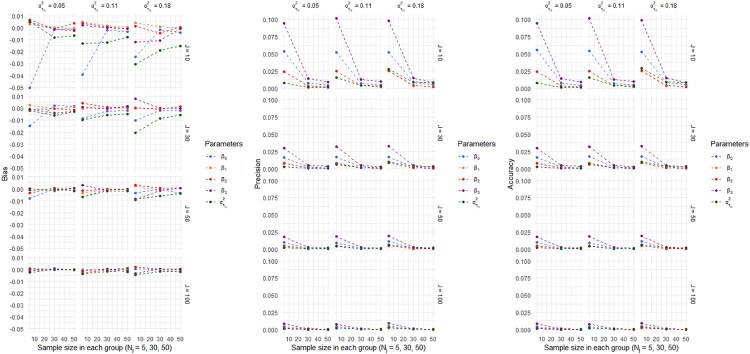

Figures 2–5 display the bias, precision and accuracy measures given in Walther and Moore [69] for the MPL, MPA, MPLH and MPAH models, respectively. With these simulation studies, it has been shown that increasing the number of groups improves the fit of each model especially when the number of observations in these groups are relatively small (e.g. in the cases of or 30). As the sample size of the groups gets larger, goodness of fit for each model gets better, independently from the number of groups. It appears that increasing the population values of the variance for the random-intercept, , does not exert a negative influence on the performance of each model in estimating model parameters. Thus, the performance of each model with respect to the bias, precision and accuracy measures appears convincing. In the next section, we provide two real life applications using these models in the context of multilevel models.

Figure 3.

The values of bias, precision and accuracy measures with varying values of the number of groups (J), number of observations in each group ( ) and the intercept variance for the MPA model.

Figure 4.

The values of bias, precision and accuracy measures with varying values of the number of groups (J), number of observations in each group ( ) and the intercept variance for the MPLH model.

Figure 2.

The values of bias, precision and accuracy measures with varying values of the number of groups (J), number of observations in each group ( ) and the intercept variance for the MPL model.

Figure 5.

The values of bias, precision and accuracy measures with varying values of the number of groups (J), number of observations in each group ( ) and the intercept variance for the MPAH model.

6. Examples

6.1. Example 1: salamanders data

We first employ the Salamanders data (N=644) presented in Price et al. [57] which was previously obtained from Dryad repository. These data were used to address the impacts of human-induced maintaintop removal mining and valley filling on the counts of salamanders in streams (data available in the glmmTMB package in R [13]). An intercept-varying model is used to illustrate the performance of our new random effects (hurdle) models against the usual multilevel Poisson (MP) and multilevel Poisson hurdle (MPH) models on hierarchical analysis of count data. In each of these models, the outcome the count of salamanders (CS) is predicted by the status of location ( ) indicating whether the location is affected by coal mining, the scaled values of the amount of cover objects in the stream (C), the scaled values of days since precipitation (DP), the scaled values of water temperature (T), the scaled values of day of year (D) and the type of salamander species ( . monticola adults, . cirrigera adults, . cirrigera larvae, Desmognathus larvae and . fuscus adults). Table 2 shows the descriptives for the seven variables in the Salamanders data. The counts of salamanders are measured at J=23 different locations making the data more suitable for hierarchical modeling than the standard Poisson modeling.

Table 2.

Descriptives of the Salamanders data.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| TS | ||

| GP | 92 | 0.143 |

| PR | 92 | 0.143 |

| DM | 92 | 0.143 |

| EC-A | 92 | 0.143 |

| EC-L | 92 | 0.143 |

| DES-L | 92 | 0.143 |

| DF | 92 | 0.143 |

| SL | ||

| no | 336 | 0.522 |

| yes | 308 | 0.478 |

| Mean | Standard deviation | Median | Min | Max | Range | Standard error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 1.32 | 2.64 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 36.00 | 36.00 | 0.10 |

| C | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.05 | 1.59 | 1.89 | 3.48 | 0.04 |

| DP | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.09 | 2.20 | 3.17 | 5.37 | 0.04 |

| T | 0.00 | 0.98 | 0.04 | 3.02 | 2.21 | 5.23 | 0.04 |

| D | 0.00 | 1.00 | 0.06 | 2.71 | 1.46 | 4.17 | 0.04 |

A Backward stepwise regression [16,30] technique is used to determine the predictors in the models presented in this study. Based on this technique, model building begins with a saturated model containing all the predictors. Then, the predictor with the highest p-value is discarded from the model and the resulting model is fitted to the data. This removal and fitting procedure continues until all the remaining predictors have p-values smaller than 0.05. As mentioned in the section ‘Parameter Estimation via Laplace and AGQ Approximations’, the AGQ approach provides more reliable sets of parameter estimates than the Laplace approximation, since the latter approach is a special case of the former approach with only one quadrature point. Therefore, parameter estimation during the model building is performed by using the AGQ approach with 11 quadrature points. Then, the created models are also used with the Laplace approximation (see the online supplementary material).

The intercept-varying MP regression model is determined based on the Backward stepwise regression model building technique is defined as

| (18) |

where and the β's are the coefficients of the variables in the model. Notably, parameter is the overall (fixed) intercept which is the mean of the J=23 random intercepts. Here, denotes the value of the random error around the overall intercept for the jth location ( ). So, is the value of the random intercept for the jth location ( ). The observed counts of CS according to the type of species across 23 different locations contains excess zeroes (see Figure 1 in the online supplementary material). This indicates that the usual MP model may not fit adequately, as it does not sufficiently take into account the heterogeneity in the data when estimating model parameters. Thus, the data are also analyzed using the proposed MPL and MPA intercept-varying models both of which better take into account heterogeneity across the locations. Moreover, Price et al. [57, p. 462] state that occupancy of streams (i.e. unoccupied locations and occupied locations) should be modeled separately from the non-zero counts of salamanders to avoid biases in estimating model parameters. Thus, the hurdle counterparts of these three models, namely, the MPH, MPLH and MPAH intercept-varying models are used to take into account the two-piece structure of the data.

Table 3 shows the observed and expected counts of salamanders for each model under consideration using AGQ approach with 11 quadrature points. The multilevel hurdle models (MPH, MPLH and MPAH) produce the expected number of zero counts that are equal to the observed zeros in the data.

Table 3.

Observed and expected number of Salamander counts (CS) for each model using AGQ approach with 11 quadrature points.

| Expected frequencies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed frequencies | MP | MPL | MPA | MPH | MPLH | MPAH | |

| 0 | 387 | 221.49 | 298.61 | 271.47 | 387 | 387 | 387 |

| 1 | 79 | 236.40 | 167.33 | 190.43 | 67.56 | 92.82 | 88.50 |

| 2 | 61 | 126.16 | 88.75 | 100.19 | 76.43 | 62.19 | 65.06 |

| 3 | 30 | 44.88 | 45.41 | 46.85 | 57.63 | 39.92 | 42.52 |

| 4 | 29 | 11.98 | 22.65 | 20.54 | 32.60 | 24.88 | 26.05 |

| 5 | 17 | 2.56 | 11.09 | 8.65 | 14.75 | 15.18 | 15.32 |

| ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| 36 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total | 644 | 644 | 644 | 644 | 644 | 644 | 644 |

| Averages of | |||||||

| linear predictors | |||||||

Table 4 displays the MLEs and their standard errors and model evaluation indices for these models. The model evaluation indices the Akaike information criterion (AIC; [3,4]) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC; [61]) take both the log likelihood (ℓ) and complexity into account when evaluating the models under consideration. The log likelihood represents the fit of a model to the data. The complexity penalizes the model based on the number of parameters in the model. The models with large log likelihoods and small complexities have small AIC and BIC values, and consequently are considered as the best models in the set. The resutls show that the MP and MPH models are the worst models in the set of models as they render the largest minus log likelihoods among the others. The MPLH and MPAH models provide the smallest minus log likelihoods in the set, and thus, they fit the data better than the others. However, note that, the multilevel hurdle models have advantage over the usual multilevel models in terms of model fit as they also have the logit component containing additional parameters. Since these models contain more parameters in modeling the data, they should be penalized more than their usual counterparts. For example, the complexities for the MPL and MPLH models are 9 and 19, respectively, which means that the MPLH model is penalized more than the MPL model (see Table 4). Based on the values of information criteria in Table 4, the MPL, MPLH and MPAH models performed similarly and better than the MP, MPA and MPH models as the former models provided smaller AIC and BIC values than the latter models using the AGQ approach with 11 quadrature points. Similar results are obtained using the Laplace approximation for estimation (see the online supplementary material).

Table 4.

The MLEs and their standard errors and model fit indices obtained by each model under consideration for the Salamanders data using AGQ approach with 11 quadrature points.

| MP | MPL | MPA | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | β | SE | γ | SE | β | SE | γ | SE | β | SE | γ | SE |

| (Intercept) | 1.64*** | 0.24 | – | – | 1.66*** | 0.27 | – | – | 1.65*** | 0.26 | – | – |

| SL(yes) | 2.28*** | 0.28 | – | – | 2.25*** | 0.28 | – | – | 2.26*** | 0.28 | – | – |

| C | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| DP | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| T | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D | 0.10** | 0.04 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| TS(PR) | 1.39*** | 0.22 | – | – | 1.35*** | 0.27 | – | – | 1.36*** | 0.25 | – | – |

| TS(DM) | 0.23 | 0.13 | – | – | 0.33 | 0.20 | – | – | 0.31 | 0.18 | – | – |

| TS(EC-A) | 0.77*** | 0.17 | – | – | 0.74** | 0.24 | – | – | 0.74*** | 0.22 | – | – |

| TS(EC-L) | 0.62*** | 0.12 | – | – | 0.57** | 0.20 | – | – | 0.56** | 0.18 | – | – |

| TS(DES-L) | 0.68*** | 0.12 | – | – | 0.75*** | 0.19 | – | – | 0.75*** | 0.17 | – | – |

| TS(DF) | 0.08 | 0.13 | – | – | 0.23 | 0.21 | – | – | 0.21 | 0.19 | – | – |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||

| (Intercept) | ||||||||||||

| 0.32 | 0.57 | 0.30 | 0.55 | 0.31 | 0.56 | |||||||

| Model fit indices | ||||||||||||

| 968.39 | 826.64 | 839.55 | ||||||||||

| Complexity | 10 | 9 | 9 | |||||||||

| AIC | 1956.78 | 1671.28 | 1687.10 | |||||||||

| BIC | 1968.14 | 1681.50 | 1707.32 | |||||||||

| MPH | MPLH | MPAH | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | β | SE | γ | SE | β | SE | γ | SE | β | SE | γ | SE |

| (Intercept) | 0.17 | 0.19 | 1.76*** | 0.28 | 0.54 | 0.30 | 1.76*** | 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.26 | 1.76*** | 0.28 |

| SL(yes) | 1.24*** | 0.16 | 2.40*** | 0.21 | 1.35*** | 0.24 | 2.40*** | 0.21 | 1.26*** | 0.22 | 2.40*** | 0.21 |

| C | 0.28*** | 0.06 | – | – | 0.24** | 0.09 | – | – | 0.22** | 0.08 | – | – |

| DP | 0.10* | 0.04 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| T | 0.11* | 0.05 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| D | 0.25*** | 0.04 | – | – | 0.21** | 0.08 | – | – | 0.20** | 0.07 | – | – |

| TS(PR) | 0.60* | 0.28 | 1.68*** | 0.40 | 0.59 | 0.44 | 1.68*** | 0.40 | 0.56 | 0.39 | 1.68*** | 0.40 |

| TS(DM) | 0.20 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.29 | 0.26 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.43 | 0.35 |

| TS(EC-A) | 0.04 | 0.20 | 1.11** | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.35 | 1.10** | 0.37 | 0.01 | 0.31 | 1.10** | 0.37 |

| TS(EC-L) | 0.61*** | 0.13 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.57* | 0.25 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.53* | 0.22 | 0.43 | 0.35 |

| TS(DES-L) | 0.61*** | 0.13 | 0.67 | 0.35 | 0.75** | 0.25 | 0.67 | 0.35 | 0.70** | 0.22 | 0.67 | 0.35 |

| TS(DF) | 0.02 | 0.16 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.27 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.43 | 0.35 |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||

| (Intercept) | ||||||||||||

| 0.006 | 0.08 | 0.003 | 0.05 | 0.003 | 0.05 | |||||||

| Model fit indices | ||||||||||||

| 855.67 | 812.82 | 812.64 | ||||||||||

| Complexity | 21 | 19 | 19 | |||||||||

| AIC | 1753.34 | 1663.64 | 1663.28 | |||||||||

| BIC | 1777.19 | 1685.21 | 1684.85 | |||||||||

Notes: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

+ 2 × Complexity. + Complexity ×log(J).

Complexity: The number of model parameters. J: The number of clusters in the data. AIC and BIC values are calculated in line with the summary output of mixed_model function in the R package GLMMadaptive.

Figure 6 displays diagnostic plots for the location-level random errors 's using the MP, MPA and MPAH models. Similar diagnostic plots can also be obtained for other models under consideration which would be available upon request. The quantile-quantile plot (left panel) for each of the three models shows that the assumption with respect to the normality of the location-level random errors appears to be satisfied, because their values fluctuate around the straight line. The scatter plots (middle panel) show that the assumption of the constancy of variance between random errors are satisfied for each of the three models as no discernable pattern has been observed around the zero in the y-axes. The caterpillar plots (right panel) display the location effects in ascending order with 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 6.

Diagnostic plots for the location-level random effect using the MP, MPA and MPAH models.

6.2. Example 2: epilepsy data

We use the Epilepsy data (N=236) presented in Thall and Vail [65] to exemplify the potentiality of the MPL and MPA models and their hurdle counterparts in the context of a slope-varying hierarchical model. This clinical trial is conducted over J=59 patients, each of whom has 4 consecutive measures on the outcome the number of patient seizure counts (CS) in a period of 2 weeks (data are obtained from the MASS package in R [42]). The outcome is predicted by the type of treatment ( ), the log of the average counts of seizures in the 8-week period before the study (logCS8) and the indicator of the fourth measure during the study ( ). The main objective of the study is to investigate whether the patients in the treatment group have relatively less amount of epileptic seizures in comparison to the patients in the placebo group after taking chemotherapy. Table 5 displays the descriptives of the variables in the Epilepsy data.

Table 5.

Descriptives of the Epilepsy data.

| Variables | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| T | ||

| Placebo | 112 | 0.475 |

| Drug | 124 | 0.525 |

| P4 | ||

| no | 117 | 0.750 |

| yes | 59 | 0.250 |

| Mean | Standard deviation | Median | Min | Max | Range | Standard error | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | 8.26 | 12.36 | 4.00 | 0.00 | 102.00 | 102.00 | 0.80 |

| logCS8 | 1.77 | 0.75 | 1.70 | 0.41 | 3.63 | 3.23 | 0.05 |

The slope-varying multilevel model in which the ith measure on the jth patient is defined as

| (19) |

where , , and are the coefficients of patient-level variables T, logCS8 and P4, respectively and and are the random errors for the intercepts and slopes at the patient-level with and for i=1,2,3,4 and . Note that, the random errors and are assumed to be independent from each other, that is, . Parameters and are the overall (fixed) intercept and slope terms which are the means of the J=59 random intercepts and random slopes, respectively. Therefore, and are the values of the random intercept and random slope for the jth patient, respectively ( ). In addition to the MP model above and its hurdle counterpart, the MPL and MPA models and their hurdle counterparts are applied to investigate and compare their fitting performance. Estimation during the model building is performed by using the AGQ approach with the Backward stepwise regression technique.

Table 6 displays the observed and expected counts of patient seizures for each model under evaluation using the AGQ approach. The MPL and MPA models provide expected frequencies that are closer to the observed frequencies in the data when compared to the usual MP model. The same assessment applies in the context of multilevel hurdle models. That is, the MPLH and MPAH models provide better expected frequencies than the usual MPH model in terms of their closeness to the observed frequencies. Table 7 shows the MLEs and their standard errors, the minus log likelihood, the complexity, and the model evaluation indices for each model under consideration using the AGQ approach. The MPA model performs better than the other models as it produces the smallest AIC and BIC values in the set. However, note that, the values of AIC and BIC model evaluation indices are quite sensitive to the sample size, the heterogeneity in the data, the predictors used in the model and their statistical significance on the dependent variable. Considering that only 4 measures were taken on each patient during the study period, it is also important to note that the models for this real life application will serve only for demonstrative purposes. In this manner, studies with large sample sizes or more advanced model selection tools that perform well in the presence of small samples will be considered good research practices for the future practical applications of the proposed modeling framework.

Table 6.

Observed and expected number of patient seizure counts (CS) for each model using AGQ approach with 11 quadrature points.

| Expected frequencies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed frequencies | MP | MPL | MPA | MPH | MPLH | MPAH | |

| 0 | 23 | 0.27 | 16.52 | 10.81 | 23 | 23 | 23 |

| 1 | 16 | 1.83 | 19.17 | 17.00 | 1.14 | 18.91 | 16.26 |

| 2 | 20 | 6.20 | 20.14 | 20.04 | 4.10 | 19.81 | 19.14 |

| 3 | 33 | 14.00 | 19.98 | 21.00 | 9.85 | 19.61 | 20.02 |

| 4 | 29 | 23.69 | 19.10 | 20.63 | 17.76 | 18.70 | 19.64 |

| 5 | 17 | 32.09 | 17.79 | 19.46 | 25.60 | 17.38 | 18.49 |

| ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· | ··· |

| 102 | 1 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Total | 236 | 236 | 236 | 236 | 236 | 236 | 236 |

| Averages of | |||||||

| linear predictors | |||||||

Table 7.

The MLEs and their standard errors and model fit indices obtained by each model under consideration for the Epilepsy data using AGQ approach with 11 quadrature points.

| MP | MPL | MPA | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | β | SE | γ | SE | β | SE | γ | SE | β | SE | γ | SE |

| (Intercept) | 1.83*** | 0.11 | – | – | 1.86*** | 0.11 | – | – | 1.85*** | 0.11 | – | – |

| T(drug) | 0.34* | 0.15 | – | – | 0.31* | 0.15 | – | – | 0.32* | 0.15 | – | – |

| logCS8 | 1.00*** | 0.11 | – | – | 1.00*** | 0.11 | – | – | 1.00*** | 0.11 | – | – |

| P4 | 0.16** | 0.05 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||

| (Intercept) | ||||||||||||

| 0.25 | 0.50 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.35 | |||||||

| logCS8 | ||||||||||||

| 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.22 | 0.05 | 0.22 | |||||||

| Model fit indices | ||||||||||||

| 667.23 | 654.48 | 646.42 | ||||||||||

| Complexity | 6 | 5 | 5 | |||||||||

| AIC | 1346.46 | 1318.96 | 1302.84 | |||||||||

| BIC | 1358.93 | 1329.35 | 1313.23 | |||||||||

| MPH | MPLH | MPAH | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed effects | β | SE | γ | SE | β | SE | γ | SE | β | SE | γ | SE |

| (Intercept) | 1.89*** | 0.10 | 2.39*** | 0.25 | 1.65*** | 0.08 | 2.39*** | 0.25 | 1.69*** | 0.08 | 2.39*** | 0.25 |

| T(drug) | 0.28* | 0.14 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| logCS8 | 0.96*** | 0.10 | 0.88* | 0.34 | 1.06*** | 0.12 | 0.88* | 0.34 | 1.02*** | 0.11 | 0.88* | 0.34 |

| P4 | 0.15** | 0.06 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Random effects | ||||||||||||

| (Intercept) | ||||||||||||

| 0.18 | 0.42 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.08 | 0.29 | |||||||

| logCS8 | ||||||||||||

| 0.07 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.09 | 0.30 | |||||||

| Model fit indices | ||||||||||||

| 658.02 | 655.12 | 649.74 | ||||||||||

| Complexity | 8 | 6 | 6 | |||||||||

| AIC | 1332.04 | 1322.24 | 1311.48 | |||||||||

| BIC | 1348.66 | 1334.71 | 1323.95 | |||||||||

Notes: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

AIC = -2 + 2 × Complexity. BIC = -2 + Complexity (J).

Complexity: The number of model parameters. J: The number of clusters in the data. AIC and BIC values are calculated in line with the summary output of mixed_model function in the R package GLMMadaptive.

Figure 7 shows diagnostic plots of the patient-level random errors for slopes, 's, using the MP, MPL and MPLH models. Similar diagnostic plots can also be attained for other models under evaluation and for the random errors of the intercepts, 's, which would be made available upon request. Similar conclusions with the diagnostic plots presented in the previous section are made in terms of the assumptions of normality and constancy of the variance of random errors for slopes. Notably, the caterpillar plots contain quite large confidence intervals around the random errors in ascending order, since only four measures are attained for each patient in the study.

Figure 7.

Diagnostic plots for the patient-level random effect using the MP, MPL and MPLH models.

7. Discussion

Statistical practices for count modeling present several problematic issues that urge the methodological developments in their respect. Amongst the all problems, overdispersion takes the focal part of the literature and promotes the consideration of the mechanisms that generate the excess variation. Unobserved heterogeneity and excessive number of zeros are expressed as the prominent causes of overdispersion. Hierarchical or clustered design of the study also adds to the heterogeneity as the unobservable effects at various levels also contribute to the overdispersion. In such cases, extension of GLMs by the inclusion of cluster-specific random effects account for the dependency between the observations within the same cluster. Facing a problem characterized by excessive number of zeros, overdispersed counts and intraclass correlation due to clustering is therefore a real challenge that is the subject of this study.

When study design is at a single level, assuming the conventional Poisson form for the stochastic component is not appropriate the overdispersion due to unobserved heterogeneity is present in the data. Within the GLM framework, general attitude towards this problem is to change the distributional assumption of Poisson to a more flexible one. Heterogenous Poisson distributions provide such flexibility and they are obtained by compounding Poisson distribution with a continuous distribution, e.g. Poisson–Gamma mixture, namely Negative Binomial. Compounding Poisson with lifetime distributions has also attracted attention, Poisson–Lindley (PL) and Poisson–Ailamujia (PA) are the most recent evaluations. For the comprehensive challenge described above, we here developed a GLMM strategy by incorporating Poisson–Lindley and Poisson–Ailamujia heterogeneous distributions for the stochastic component of the model to account for the unobserved heterogeneity. Due the limited number of such approaches developed for the structural zeros, we also concentrated on the hurdle models. Derivation of the parameters for multilevel PL and PA hurdle models proposed here was achieved by means of Laplace approach and adaptive Gaussian-Hermite quadrature (AGQ) algorithms comparatively.

The predictive performances of each model under consideration are separately investigated using Laplace algorithm, by means of bias, precision and accuracy measures within a comprehensive simulation study. By considering different aspects of multilevel simulation design, it is concluded that enhancing the number of clusters and the number of observations in these clusters play an essential role to achieve a satisfying predictive performance for each model. Besides, the population value of the variance for random-intercepts does not have much influence on the performance of the models. In two real world applications, observed and expected number of counts for outcomes, MLEs and standard errors of model parameters and model fit indices such as AIC and BIC are inspected by means of both Laplace and AGQ approaches (see also the online supplementary material). It is concluded that the AGQ performs better than Laplace, since the latter approach is only a special case of the former approach.

Supplementary Material

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- 1.Agresti A., Caffo B., and Ohman-Strickland P., Examples in which misspecification of a random effects distribution reduces efficiency, and possible remedies, Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 47 (2004), pp. 639–653. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed S.S., Pantangi S.S., Eker U., Fountas G., Still S.E., and Anastasopoulos P.Ch., Analysis of safety benefits and security concerns from the use of autonomous vehicles: A grouped random parameters bivariate probit approach with heterogeneity in means, Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 28 (2020), pp. 100134. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akaike H., Information theory and extension of the maximum likelihood principle, B.N. Petrov and F. Csaki, eds., Proceedings 2nd international symposium information theory, Akademiai kiado, Budapest, 1973, pp. 267–281.

- 4.Akaike H., A new look at the statistical model identification, IEEE Trans. Automat. Contr. 19 (1974), pp. 716–723. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akdur H.T.K., Unit-Lindley mixed-effect model for proportion data, J. Appl. Stat. 48 (2021), pp. 2389–2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anastasopoulos P.Ch., Random parameters multivariate tobit and zero-inflated count data models: Addressing unobserved and zero-state heterogeneity in accident injury-severity rate and frequency analysis, Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 11 (2016), pp. 17–32. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anastasopoulos P.Ch., Mannering F., Shankar V., and Haddock J., A study of factors affecting highway accident rates using the random-parameters tobit model, Accid. Anal. Prev. 45 (2012), pp. 628–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berk R.A. and MacDonald J.M., Overdispersion and Poisson regression, J. Quant. Criminol. 24 (2008), pp. 269–284. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bhat C., Quasi-random maximum simulated likelihood estimation of the mixed multinomial logit model, Transp. Res. Part B. 35 (2001), pp. 677–693. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhat C., Simulation estimation of mixed discrete choice models using randomized and scrambled Halton sequences, Transp. Res. Part B. 37 (2003), pp. 837–855. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhowmik T., Yasmin S., and Eluru N., Do we need multivariate modeling approaches to model crash frequency by crash types? A panel mixed approach to modeling crash frequency by crash types, Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 24 (2019), pp. 100107. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhowmik T., Yasmin S., and Eluru N., Accommodating for systematic and unobserved heterogeneity in panel data: Application to macro-level crash modeling, Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 33 (2022), pp. 100202. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks M.E., Kristensen K., van Benthem K.J., Magnusson A., Berg C.W., Nielsen A., Skaug H.J., Maechler M., and Bolker B.M., glmmTMB: Balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling, R. J. 9 (2017), pp. 378–400. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cantoni E., Flemming J.M., and Welsh A.H., A random-effects hurdle model for predicting bycatch of endangered marine species, Ann. Appl. Stat. 11 (2017), pp. 2178–2199. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen J., Cohen P., West S.G., and Aiken L.S., Applied Multiple Regression/correlation Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 3rd ed. Routledge, New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Efrymson M.A., Multiple regression analysis, in Mathematical Methods for Digital Computers, A. Ralston and H. S. Wilf, eds., John Wiley, New York, 1960.

- 17.Eluru N., Bhat C.R., and Hensher D.A., A mixed generalized ordered response model for examining pedestrian and bicyclist injury severity level in traffic crashes, Accid. Anal. Prev. 40 (2008), pp. 1033–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Everitt B.S. and Hand D.J., Finite Mixture Distributions, Chapman & Hall, London, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feng C.X., A comparison of zero-inflated and hurdle models for modeling zero-inflated count data, J. Stat. Distrib. Appl. 8 (2021), pp. 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gallant A.R. and Nychka D.W., Semi-nonparametric maximum likelihood estimation, Econometrica 55 (1987), pp. 363–390. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garson G.D., Hierarchical Linear Modeling: Guide and Applications, SAGE Publications, Inc., Thousand Oaks, California, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghitany M.E. and Mutairi D.K., Estimation methods for the discrete Poisson–Lindley distribution, J. Stat. Comput. Simul. 79 (2009), pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghosal S., Lau T.S., Gaskins J., and Kong M., A hierarchical mixed effect hurdle model for spatiotemporal count data and its application to identifying factors impacting health professional shortages, J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. C. Appl. Stat. 69 (2020), pp. 1121–1144. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenwood M. and Yule G.U., An inquiry into the nature of frequency distribution representative of multiple happenings with particular reference to the occurence of multiple attacks of disease or of repeated accidents, J. R. Stat. Soc. 83 (1920), pp. 255–279. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grilli L. and Rampichini C., Specification of random effects in multilevel models: A review, Qual. Quant. 49 (2015), pp. 967–976. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall D., Zero-inflated Poisson binomial regression with random effects: A case study, Biometrics 56 (2000), pp. 1030–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hassan A., Shalbaf G.A., Bilal S., and Rashid A., A new flexible discrete distribution with applications to count data, J. Stat. Theory. Appl. 19 (2020), pp. 102–108. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heagerty P.J. and Kurland B.F., Misspecified maximum likelihood estimates and generalized linear mixed models, Biometrika 88 (2001), pp. 973–985. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Heilbron D., Zero-altered and other regression models for count data with added zeros, Biom. J. 36 (1994), pp. 531–547. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hocking R.R., The analysis and selection of variables in linear regression, Biometrics 32 (1976), pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hörmann W., Leydold J., and Derflinger G., Automatic Nonuniform Random Variate Generation, Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Houseman E.A., Ryan L.M., and Coull B.A., Cholesky residuals for assessing normal errors in a linear model with correlated outcomes, J. Amer. Statist. Assoc. 99 (2004), pp. 383–394. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hox J.J., Multilevel Analysis: Techniques and Applications, 2nd ed. Routledge, New York, NY, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huh D., Kaysen D.L., and Atkins D.C., Modeling cyclical patterns in daily college drinking data with many zeroes, Multivariate Behav. Res. 50 (2015), pp. 184–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Iddi S. and Molenberghs G., A combined overdispersed and marginalized multilevel model, Comput. Stat. Data. Anal. 56 (2012), pp. 1944–1951. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kassahun W., Neyens T., Molenberghs G., Faes C., and Verbeke G., A zero-inflated overdispersed hierarchical Poisson model, Stat. Modelling. 14 (2014), pp. 439–456. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kassahun W., Neyens T., Molenberghs G., Faes C., and Verbeke G., Marginalized multilevel hurdle and zero-inflated models for overdispersed and correlated count data with excess zeros, Stat. Med. 33 (2014), pp. 4402–4419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lamarche C., Shi X., and Young D.S., Conditional quantile functions for zero-inflated longitudinal count data Conditional quantile functions for zero-inflated count data, Econ. Stat. (2021). in press. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lange N. and Ryan L., Assessing normality in random effects model, Ann Stat. 17 (1989), pp. 624–642. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee A.H., Wang K., Scott J.A., Yau K.K.W., and Mclachlan G.J., Multi-level zero-inflated Poisson regression modelling of correlated count data with excess zeros, Stat. Methods Med. Res. 15 (2006), pp. 47–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee K., Joo Y., Song J.J., and Harper D.W., Analysis of zero-inflated clustered count data: A marginalized model approach, Comput. Stat. Data. Anal. 55 (2011), pp. 824–837. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee Y., Molas M., and Noh M., mdhglm: Multivariate double hierarchical generalized linear models, R package version 1.8. (2018).

- 43.Leydold J. and Hörmann W., Runuran: R interface to the ‘UNU.RA’ random variate generators, R package version 0.27. (2019).

- 44.Litière S., Alonso A., and Molenberghs G., Type I and type II error under random-effects misspecification in generalized linear mixed models, Biometrics 63 (2007), pp. 1038–1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Litière S., Alonso A., and Molenberghs G., The impact of a misspecified random-effects distribution on the estimation and the performance of inferential procedures in generalized linear mixed models, Stat. Med. 29 (2010), pp. 2166–2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maas C.J.M. and Hox J.J., Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling, Methodol. Eur. J. Res. Methods Behav. Soc. Sci. 1 (2005), pp. 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mannering F., Shankar V., and Bhat C., Unobserved heterogeneity and the statistical analysis of highway accident data, Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 11 (2016), pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 48.McCullagh P. and Nelder J., Generalized Linear Models, 2nd ed. Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, FL, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 49.McCullogh C.E. and Searle S.R., Generalized Linear and Mixed Models, Wiley, New York, NY, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Milton J., Shankar V.N., and Mannering F.L., Highway accident severities and the mixed logit model: An exploratory empirical analysis, Accid. Anal. Prev. 40 (2008), pp. 260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Min Y. and Agresti A., Random effect models for repeated measures of zero-inflated count data, Stat. Modelling. 5 (2005), pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Molas M. and Lesaffre E., Hurdle models for multilevel zero-inflated data via h-likelihood, Stat. Med. 29 (2009), pp. 3294–3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mood C., Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it, Eur. Sociol. Rev. 26 (2010), pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mullahy J., Specification and testing of some modified count data models, J. Econom. 33 (1986), pp. 341–365. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pantangi S.S., Fountas G., Sarwar Md.T., Anastasopoulos P.Ch., Blatt A., Majka K., Pierowicz J., and Mohan S.B., A preliminary investigation of the effectiveness of high visibility enforcement programs using naturalistic driving study data: A grouped random parameters approach, Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 21 (2019), pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pinheiro J.C. and Bates D.M., Approximations to the log-likelihood function in the nonlinear mixed-effects model, J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 4 (1995), pp. 12–35. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Price S.J., Muncy B.L., Bonner S.J., Drayer A.N., and Barton C.D., Effects of mountaintop mining and valley filling on the occupancy and abundance of stream salamanders, J. Appl. Ecol. 53 (2016), pp. 459–468. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rizopoulos D., GLMMadaptive: Generalized linear mixed models using adaptive gaussian quadrature, R package version 0.5-1. (2019).

- 59.Sankaran M., The discrete Poisson–Lindley distribution, Biometrics 26 (1970), pp. 145–149. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Santosa F. and Symer W.W., Linear inversion of band-limited reflection seismograms, SIAM J. Sci. Stats. Comput. 7 (1986), pp. 1307–1330. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schwarz G., Estimating the dimension of a model, Ann. Stat. 6 (1978), pp. 461–464. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shanker R. and Fesshaye H., On Poisson–Lindley distribution and its applications to biological sciences, Biom. Biostat. Int. J. 2 (2015), pp. 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sharma A., Zheng Z., Kim J., Bhaskar A., and Haque Md.M., Is an informed driver a better decision maker? A grouped random parameters with heterogeneity-in-means approach to investigate the impact of the connected environment on driving behaviour in safety-critical situations, Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 27 (2020), pp. 100127. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Snijders T.A.B., Fixed and random effects, in Wiley Stats Ref: Statistics Reference Online, N. Balakrishnan, T. Colton, B. Everitt, W. Piegorsch, F. Ruggeri and J.L. Teugels, eds., 2014.

- 65.Thall P.F. and Vail S.C., Some covariance models for longitudinal count data with overdispersion, Biometrics 46 (1990), pp. 657–671. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tibshirani R., Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso, J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Methodol. 58 (1996), pp. 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Venkataraman N., Ulfarsson G.F., and Shankar V.N., Random parameter models of interstate crash frequencies by severity, number of vehicles involved, collision and location type, Accid. Anal. Prev. 59 (2013), pp. 309–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Verbeke G. and Molenberghs G., Linear Mixed Models for Longitudinal Data, Springer, Berlin, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Walther B.A. and Moore J.J., The concepts of bias, precision and accuracy, and their use in testing the performance of species richness estimators, with a literature review of estimator performance, Ecography 28 (2005), pp. 815–829. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yasmin S. and Eluru N., Latent segmentation based count models: Analysis of bicycle safety in Montreal and Toronto, Accid. Anal. Prev. 95 (2016), pp. 157–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yau K.K. and Lee A.H., Zero-inflated poisson regression with random effects to evaluate an occupational injury prevention programme, Stat. Med. 20 (2001), pp. 2907–2920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yu R., Wang Y., Quddus M., and Li J., A marginalized random effects hurdle negative binomial model for analyzing refined-scale crash frequency data, Anal. Methods Accid. Res. 22 (2019), pp. 100092. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang X. and Yi N., NBZIMM: Negative binomial and zero-inflated mixed models, with application to microbiome/metagenomics data analysis, BMC Bioinform. 21 (2020), pp. 488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhu H., Luo S., and DeSantis S.M., Zero-inflated count models for longitudinal measurements with heterogeneous random effects, Stat. Methods. Med. Res. 26 (2017), pp. 1774–1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.