Abstract

Background:

Although care management approaches have potential to improve clinical outcomes and reduce high health care costs of patients with complex substance use disorders, characterized by high psychosocial, psychological and/or medical needs and high acute healthcare utilization, little is known about patients’ perspectives or experiences with these interventions.

Aims:

To identify barriers and facilitators to patient engagement in care management services for complex substance use disorders from patients’ perspectives.

Methods:

This pilot study invited 22 men with complex substance use disorders and high healthcare utilization who were enrolled in a 1-year open trial of a care management model to complete semi-structured interviews at 1- and 3-months post baseline. Interviews were recorded, transcribed and analyzed using template analysis.

Results:

Five themes related to engagement were identified: barriers to conventional substance use disorder treatment, facilitators of care management services, patient-provider relationship, patient-related factors and enhancements to a care management model. Results highlighted the importance of the patient-provider relationship, individual visits with providers, flexible and personalized treatment and a focus on recovery over abstinence in promoting patient engagement in care management services. Results also highlighted a need for increased outreach and assistance with housing and transit to treatment.

Conclusion:

Patients’ perspectives support key elements of the care management services that are designed to facilitate patient engagement and suggest the need for additional outreach and assistance with obtaining shelter and transportation. Additional research is needed to evaluate if care management approaches enhance retention, improve outcomes and reduce health care utilization of patients with complex and chronic substance use disorders.

Keywords: complex substance use disorders, chronic substance use disorders, care management, patient perspective, high utilization

Introduction

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are among the most common and costly medical conditions treated in the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system and are associated with significant comorbidity and mortality.[1–3] For a subset of patients substance-use problems are severe and complex, characterized by recurrent use of SUD specialty-care, recurring relapse, high rates of mental health and medical comorbidity and disproportionate use of acute care services.[4–9] Based on the widely accepted Chronic Care Model, care management is an approach with potential to improve clinical outcomes while also reducing health care costs of these patients.[10] However, little is known about patients’ perspectives of care management approaches when applied specifically to SUD.

The central goal of care management is to shift the focus of health care from expensive crisis driven care toward proactive and planned management of chronic illnesses over time Such services typically provide or coordinate the delivery of comprehensive services to address the medical, mental health and psychosocial needs of patients.[10, 11] While care management approaches for elderly patients and patients with complex medical needs, such as congestive heart failure, have been evaluated,[10, 12–14] there is a lack of literature on care management approaches specifically adapted for patients with complex SUDs.[15–17]

We piloted a care management model (CMM) adapted for patients with severe and complex substance use conditions and persistent high health care utilization. CMM was designed to enhance patient engagement and retention by delivering flexible and efficient substance use and psychiatric care and improving coordination with other hospital clinics when needed (e.g., specialized medical services), while simultaneously addressing the limitations of conventional SUD treatment, such as time-limited episodes of care, requirements to abstain from substances, uniform delivery of services, lack of total coordinated care and minimal or no follow-up.[18–22] Although traditional case management is often a component of conventional SUD care, it typically involves large caseloads managed by individual case managers, occurs for short periods or ceases if patients relapse to substance use and seldom includes active coordination with other medical services or a proactive approach.[19] The goals of CMM services include patient engagement and retention, improved substance use and mental health outcomes and reduction in acute services’ utilization.

Historically, patients who utilize SUD treatment services have had limited involvement in the design, refinement and implementation of those services. Patient involvement provides opportunities to identify facilitators and barriers to participation and to use this information to refine services to meet patients’ needs and preferences.[23, 24] Further, services directly informed by patients are more likely to be appealing, relevant and meaningful to the target population, which contributes to the overall successful implementation and sustainability of treatments.[25]

Little information on patients’ perspectives about and experiences with care management interventions is available in the literature.[26–28] Qualitative research with patients with complex health and social needs highlights life experiences, including early-life instability and trauma, and relationships with health care providers (e.g. difficult interactions with health care providers, positive and “caring” relationships with primary health care providers and outreach teams)[29, 30] as factors that impact patients’ care needs and engagement with services. Social and economic determinants, such as social connectedness, unemployment, housing instability and lack of financial resources, have also been identified as negatively impacting patients’ health and adherence to care management interventions.[30, 31] Although not directly related to care management, patient-identified reasons for early termination from SUD treatment include dislike of treatment staff, program features, other priorities and relapse to substances.[32]

This pilot study conducted semi-structured interviews to evaluate patients’ acceptance of and satisfaction with a CMM adapted for patients with complex SUDs and high health care utilization. The specific aim of this study was to identify barriers and facilitators to patient engagement with CMM services from patients’ perspectives. To address this aim, we assessed patients’ beliefs regarding: 1) reasons for initiating treatment; 2) experience with CMM, including how this experience differed from past SUD treatment; 3) features of CMM that facilitated or hindered early engagement; and 4) how to improve the CMM under study.

Methods

Design

This qualitative study represents one aim of a mixed-method, prospective pilot study designed to assess the feasibility and acceptability of a CMM for patients with complex SUD and high utilization of inpatient and/or emergency department (ED) services. Patients enrolled in a 1-year open trial of CMM were invited to complete qualitative interviews at one and three months.

Setting and sample

The study recruited patients at the VA Puget Sound Health Care System over a 16-month period during 2013 and 2014. Using the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW), a national data repository of patients receiving VA health care services, we developed a registry of 419 patients (390 men, 29 women) who met the following criteria: 1) ≥ 2 episodes of SUD specialty-care in prior two years and 2) ≥1 inpatient SUD and/or mental health admission in two of three prior consecutive years, or ≥2 ED visits in each of the prior two consecutive years. Patients were considered to have initiated a new episode of VA SUD treatment if they had: 1) an intake evaluation, 2) an inpatient admission for SUD specialty-care, or 3) ≥ 2 outpatient SUD specialty-care visits in a 30 day period (excluding telephone visits), after a lapse in SUD treatment of ≥ 60 days. A mental health diagnosis was not required to receive CMM services. Our recruitment goal was 20 participants.

Using CDW encounter data, reports were generated daily to monitor registry patients’ recent and pending appointments. Reports included utilization in four key clinical pathways: 1) ED, 2) inpatient mental health care or SUD detoxification services, 3) primary care or 4) SUD specialty-care. These reports, in conjunction with cooperative arrangements with clinical providers in the clinical pathways, allowed for targeted recruitment of eligible patients engaged in hospital but not SUD specialty-care. The study coordinator (BH) contacted clinical providers in advance of pending appointments to encourage them to introduce the study to patients. If patients were interested in participation following introductions by their provider, they were further screened via telephone or in person by the study coordinator. Patients were excluded from participation if they had 1) moderate to severe cognitive impairment, as assessed by the Minicog; 2) expected incarceration; 3) current enrollment in SUD-specialty care; 4) current opioid use disorder with a history of methadone treatment, which the current study could not provide due to federal regulations or 5) abstinence from substances in the prior 90 days.[33] All others were provided with a study overview and invited to participate. Study approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of VA Puget Sound Health Care System.

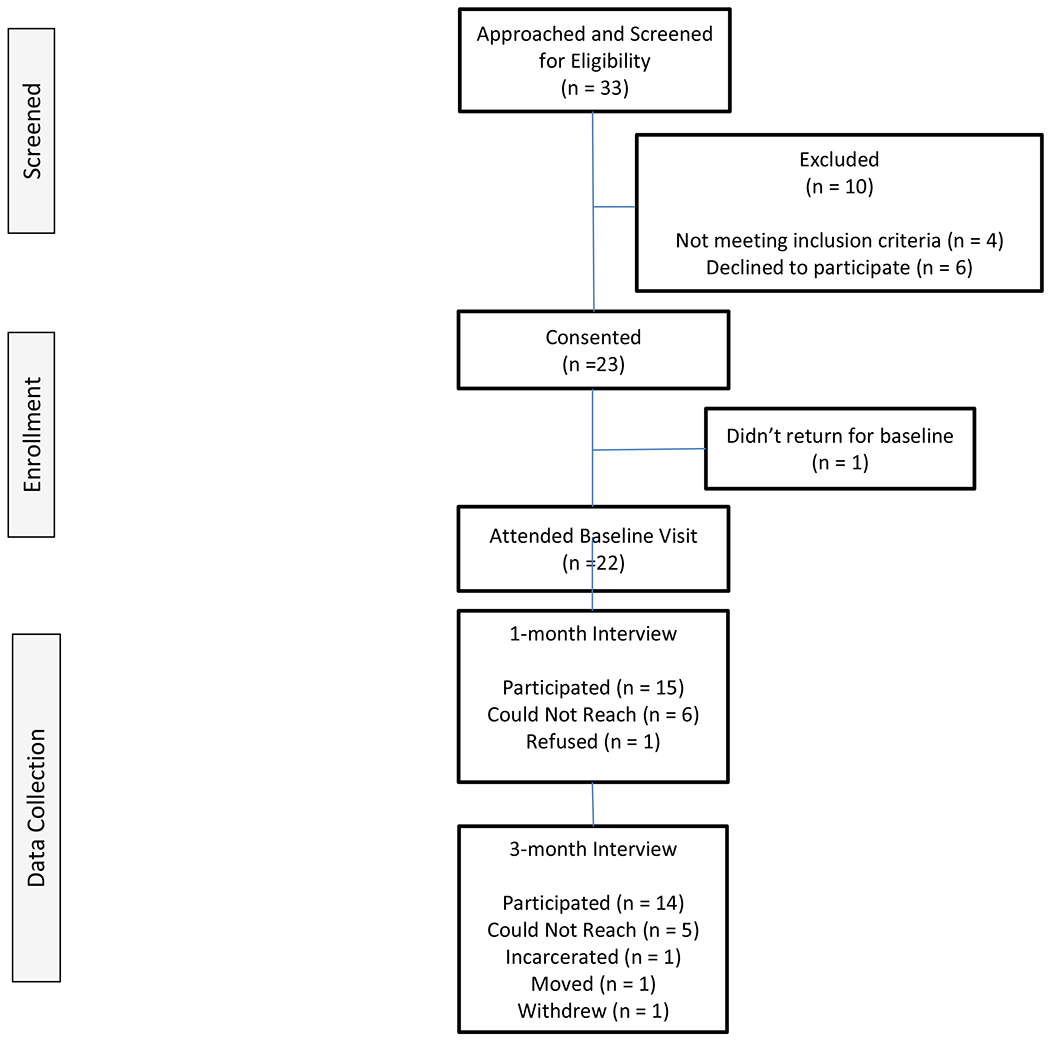

Overall, 33 patients were approached and screened and 23 were enrolled (70% recruitment rate) and offered CMM services for one year (Figure 1). One patient could not be contacted after completing consent procedures, and therefore did not participate further. Recruitment took longer than expected due to logistical and system barriers to screening, particularly in ED and primary care clinical pathways.

Figure 1.

Consort Flow Chart

Care Management Team

The CMM team is comprised of a social worker and psychiatrist, who were assigned to the study at 0.50 and 0.10 full-time equivalents, respectively. The CMM team received motivational interviewing training, including didactic review, tailored skill building (role playing with feedback) and measurement-based care prior to the study.

Care Management Model Intervention (See Table 1)

Table 1.

Phases, goals and strategies of the Care Management Model (CMM) for Complex Substance Use Disorders

| Treatment Phase | Model Goal | Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Early (Initial 3 months) | Engage patients using one-to-one brief contacts in person or by telephone | • Assessment of substance use and psychiatric conditions • Develop patient-provider alliance • Same-day access • Address psychosocial deficits (e.g., food, housing) • Psychiatric and substance use stabilization • Education about risky behaviors, interaction between substances and psychiatric disorders and self-monitoring |

| Intermediate (3-24 months) | Address ambivalence about psychiatric and substance use disorders and improve self-management skills | • Skills training (coping with cravings, drink refusal, social pressure, money management) • Education about medication options • Medication management and compliance • Evidence-based alcohol, opioid and psychiatric pharmacotherapies (extended release encouraged) • Monitor psychotropic mediation use and refills’ availability • Urine specimen collection • Encourage participation in community mutual recovery programs • Referral to mental health specialty-care if appropriate |

| Late | • Relapse prevention counseling • Consider transition to traditional continuing care |

|

| Relevant to all phases | Reduce emergency department and/or inpatient utilization | • Coordinate all care • Motivational interviewing • Supportive counseling • Assessment/feedback on monthly treatment progress • Follow-up calls and letters |

While patient care was supported by team-based delivery of services, interventions were delivered using one-to-one, brief contacts with providers, providing the flexibility to adapt interventions to patients’ treatment needs, goals and progress. CMM utilized individual drop-in visits for emergent issues as well as proactive scheduled visits in-person or by telephone in order to promote patient engagement, enhance the likelihood of preventing inpatient and ED utilization, and support continuity of care, which has been associated with reduced hospitalization.[34, 35]

At the initial CMM visit the social worker reviewed the baseline assessment, evaluated treatment needs and assessed barriers to early stabilization and long term recovery. Initial treatment goals and frequency of planned visits were mutually determined with patients and individualized to meet their unique needs. Plans for coordination of other services such as VA housing programs, mental health, and primary and specialty medical care were developed based on patient needs and self-identified goals. Patients received information about drop-in services, the importance of contacts for monthly assessment and contact attempts if patients miss scheduled visits or are out of contact with the team for >2 weeks. Patients were provided with opportunities to meet with the study psychiatrist for diagnostic, medication or treatment planning.

The initial focus of CMM was on interventions that facilitate early treatment engagement, including motivational interviewing, psychiatric and substance use stabilization, practical assistance with current needs such as food, clothing, community housing resources, and education about risky behaviors and development of an early patient-provider alliance.[36–39] The next stage of treatment addressed self-management of substance use and psychiatric disorders, encouraged use of evidenced-based alcohol and/or opioid pharmacotherapies (disulfiram, oral and extended release naltrexone, acamprosate or buprenorphine)[40], and educated patients’ about medications and medication compliance.[37, 41, 42] Specific interventions offered include relapse prevention counseling (e.g., coping with cravings), collection of urine specimens and medication management. Mental health symptoms were addressed with supportive therapy, evidence-based pharmacotherapies, and referrals to specialty-care if clinically indicated (e.g., Cognitive Processing Therapy for PTSD). This stage also included skills training.[43] Patients also were encouraged to participate in community recovery support programs (e.g. AA, NA).

Throughout treatment, CMM focused on symptom improvement using measurement-based care strategies instead of abstinence – substance use did not reduce or greatly change care.[44] Patients are assessed monthly for substance use and psychological distress and monitored with respect to psychotropic medication use and availability of refills. These data are used by the CMM team in weekly meetings to determine if changes to treatment or strategies to enhance medication adherence are needed, and to provide opportunities to preemptively prevent emergent mental health crises. Additionally, team members evaluated the need for additional services, including those provided outside of the CMM clinic (e.g., inpatient, residential or specialty-medical care). Additional details on CMM interventions are shown in Table 1. Patients received CMM services for 12 months in the study due to funding constraints, but in practice services would continue based on shared decision making, improved patient-management of symptoms and reduced use of acute care services.

Data collection

The baseline assessment included an in-person diagnostic interview using the Mini Neuropsychiatric Interview and demographic, substance use, and psychological distress self-report questionnaires.[45] Substance use was assessed with the Quick Drinking Screen [46] and the number of days of drug use in the past 30 days. Psychological distress was assessed with the Kessler-10.[47] Patients completed semi-structured interviews at 1- and 3-months after baseline assessment. Interview guides were informed by SUD treatment engagement and retention literatures. The interview guides ensured uniformity of key topics identified, but allowed for exploration of unanticipated ideas generated by patients. One-month interviews assessed patient-level factors related to engagement with CMM services and addressed: experience reentering treatment, experience in standard SUD treatment, and facilitators/barriers to treatment participation (Appendix A). Three-month interviews assessed patients’ perspectives on how to refine CMM services and addressed: patient experience and the type and helpfulness of CMM services provided (Appendix B).

Patients were compensated $15 to complete each interview. Interviews were conducted in private and digitally recorded by the female study coordinator (BH), who was trained in qualitative interviewing techniques by a male qualitative methodology expert (GS). BH was introduced to patients at study onset as the study coordinator and administered all study assessments, including baseline. As an employee involved in research, BH may have had previous contact with patients. Six 1-month and four 3-month interviews were audited by GS to ensure compliance with interview protocols, including review of interview techniques and question effectiveness. Feedback and additional training were provided to BH as needed.

Data Analysis

Demographics and baseline diagnostic information were summarized using descriptive statistics. Recordings were transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy. Qualitative interviews were analyzed with Atlas.ti using template analysis. Template analysis involves the development and application of a coding template that is iteratively modified and refined throughout the analysis process.[48] Using Brooks and colleagues’ methodology, the research team developed a coding template informed by a priori codes identified during interview guide development and augmented by preliminary coding of the first 2 interviews.[49] The coding template was applied to the full dataset by two female team members (BH and AF) who independently coded the remaining transcripts. Emergent codes were reviewed by two additional team members, male (EH) and female (AL), who modified the template accordingly. Previously coded interviews were reviewed using the updated coding template. Team members, two male (EH and JB) and two female (AL and CM), met to review and discuss relationships between codes, resulting in several thematic maps.

Results

All patients (n=22) were male and the majority were Caucasian (59.1%), with a mean age of 55 (Table 2). Fifty-five percent of patients had an alcohol and drug use disorder, 40.9% had a psychotic disorder, 59.1% had two or more mental health diagnoses and 45.4% were homeless/unstably housed. The mean psychological distress score, measured by the Kessler-10, was 29.2 (SD=6.9), reflecting moderate distress. Fifteen of 22 patients (68%) completed 1-month interviews and 14 (64%) completed 3-month interviews, with 13 (59%) patients completing both interviews (reasons for not completing interviews provided in Figure 1). One- and 3-month interviews were completed, on average, in 20 and 17 minutes, respectively.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients

| All Patients | Patients Interviewed | Patients Not Interviewed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Men | 22 | (100) | 16 | (100) | 6 | (100) |

| Age, years M(SD) | 55.2 | (10) | 58.3 | (8.1) | 47.2 | (10.8) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||||

| White/Caucasian | 13 | (59.1) | 10 | (62.5) | 3 | (50.0) |

| Black or African American | 7 | (31.8) | 4 | (25.0) | 3 | (50.0) |

| American Indian or Alaskan Native | 2 | (9.1) | 2 | (12.5) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Education, years M(SD) | 12.3 | (1.6) | 12.0 | (1.7) | 13.0 | (0.9) |

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Married | 2 | (9.1) | 2 | (12.5) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Divorced | 12 | (54.5) | 10 | (62.5) | 2 | (33.3) |

| Never Married | 8 | (36.4) | 4 | (25.0) | 4 | (66.7) |

| Housing | ||||||

| Stable | 12 | (54.5) | 10 | (62.5) | 2 | (33.3) |

| Unstable | 5 | (22.7) | 3 | (18.8) | 2 | (33.3) |

| Homeless | 5 | (22.7) | 3 | (18.8) | 2 | (33.3) |

| Psychological Distress M(SD) | 29.2 | (6.9) | 30.5 | (6.8) | 25.8 | (6.6) |

| Mental Health Diagnoses | ||||||

| No mental health disorder | 4 | (18.2) | 2 | (12.5) | 2 | (33.3) |

| Depressive episode | 9 | (40.9) | 9 | (56.3) | 0 | (0.0) |

| Manic episode | 14 | (63.6) | 10 | (62.5) | 4 | (66.7) |

| Psychotic disorder | 9 | (40.9) | 6 | (37.5) | 3 | (50.0) |

| PTSD | 9 | (40.9) | 7 | (43.8) | 2 | (33.3) |

| Alcohol use disorder only | 10 | (45.5) | 8 | (50.0) | 2 | (33.3) |

| Alcohol and drug use disorder | 12 | (54.5) | 8 | (50.0) | 4 | (66.7) |

| ≥ 2 mental health diagnoses | 13 | (59.1) | 9 | (56.3) | 4 | (66.7) |

| Days of drinking ≥ 5 drinks in prior 30 days M(SD) | 7.9 | (11.8) | 7.0 | (2.0) | 10.2 | (13.6) |

| Days of drug use in prior 30 days M(SD) | 4.2 | (9.1) | 5.4 | (10.7) | 0.6 | (0.9) |

Note: Data for 1 patient is not included on this table because the patient could not be reached after the consent process and therefor did not complete a baseline assessment.

Note: There were no patients with a drug use disorder only.

M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation

Analysis identified several thematic maps, including five main themes, sub-themes and underlying codes.[48] During analysis it was evident that patients’ perspectives did not change between 1- and 3-month interviews. As interviews at the two time points corroborated one another, the data were analyzed as one data set. Themes, sub-themes (identified as a priori or emergent) and relevant quotes are reported in Table 3. Quotes most representative of the theme and/or subtheme were included in results. The sample of quotes selected represent 11 unique patients.

Table 3.

Patient Quotes

| Sub-theme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: Barriers to conventional substance use disorder treatment | |

| Group Treatment (emergent) | I’m not comfortable and tend to not open up at all. [Patient 1] I didn’t identify much with people in groups. So I didn’t feel like I had a lot of information to give in groups, so I felt pretty much left out. [Patient 1] When I did stop going, it was a relief, because it’d gotten to the point where it’d become dogmatic for me. Sitting in there lost its effect with me. [Patient 2] |

| Abstinence Policy (emergent) | Again, it’s a failed course, down there. “Okay, you screwed up, you’re out of here.” At that level, I feel discarded… [Patient 3] |

| Theme 2: Perceived facilitators of CMM features | |

| Personalized Care (a priori) See Appendix A (Question 1) See Appendix B (Question 2) |

I can’t say enough about how you are adapting. It just keeps coming up, things keep coming up as far as ‘if you need this or need that, we can work with you on it.’ You’ve been working with me, I just can’t see anymore that you could do. Going out of your way for me. [Patient 1] Just the personal care that people take when you come in and talk to people and how they’re willing to go out of their way to get things to help you or talk with you, that’s really good. There’s nothing wrong with that. That’s why I’m up here, and not down there. Because it doesn’t work like that down there. [Patient 4] |

| Individual Appointments (a priori) See Appendix A (Question 1) See Appendix B (Question 2) |

So the one-on-one is what I wanted, so I could talk to each of you individually, and I feel a lot more comfortable opening up and being able to talk to you guys. [Patient 5] A more relaxed environment that makes me feel more comfortable. In general I feel a lot more comfortable coming here for one on one than when in groups. I’m more apt to open up and say what’s going on. [Patient 1] |

| Team-based (emergent) | …it’s a team and everybody is working with me… [Patient 4] |

| Treatment Focus (emergent) | I feel like this would be a better program for me to be in because it’s not something you know, you gotta’ be clean and sober or they don’t want to deal with you and stuff, but they give you a chance, you know, you make some mistakes, don’t worry about it, just keep on coming and keep on trying. [Patient 6] |

| Theme 3: Relational factors | |

| Familiarity with Providers (a priori) See Appendix A (Question 1) See Appendix B (Question 2) |

It’s just, they know me. They’ve known me since ‘96 or something like this. I trust them. I can get into my feelings. [Patient 7] I’ve known [Name] for years. I feel good talking to her and laying out my troubles. I hate to say it like this, but I kind of, I look forward to just talking to her. But I’ve known her for years, not just a week or a month; I have known her for years. And I’ve known [Name] for years. Sometimes it feels good to just be in their presence. [Patient 8] |

| Providers caring/taking an interest in them (emergent) | And they’re there for me. That’s just the bottom line. I feel they’re there for me not only as their job duties require, but because they care about me and want to be a part of my life. [Patient 2] |

| Trust (emergent) | Whatever happened to you in the past, they’ll help you deal with it and move on. And it’s a good place, that’s what I’d tell them, it’s a good, safe place. [Patient 9] I feel like I can honestly open up to them. We have a bonding, a trust bond and [Name] will let me vent. [Patient 10] |

| Theme 4: Patient factors | |

| Psychosocial, Barriers ( a priori) See Appendix A (Question 4) See Appendix B (Question 3) |

If I ever had the thought of not bothering to pick up the phone when called, it would be my choice and there wouldn’t be anything anyone could do about it, so it’s up to me. [Patient 11] |

| Psychosocial, Facilitators (emergent) | The people that are trying to help me, I don’t want to let down, at all cost. I never felt this way before. [Patient 9] |

| Theme 5: Program Refinement | |

| Existing Services (emergent) | But I get isolated. That’s why I said letters would help me with appointments. More phone calls. [Patient 10] |

| Additional Services (emergent) | Yeah, because when I came back here I was pretty broke. All of the money was stolen from me in Tent City. So the difficulty was trying to get on the bus or even walk. [Patient 7] At the VA back East, the outpatient Veterans they had these trips. We’d go fishing, or to the park or to the lake. All of the Veterans, inpatients and outpatients, were eligible. If you guys had that, that’d be nice. [Patient 8] |

Barriers to conventional substance use disorder treatment

Barriers to conventional SUD treatment resulted in two subthemes: group treatment and abstinence.

Patients reported group treatment as not a good fit for people who are quiet and/or have social anxiety, and described group treatment as uncomfortable. Patients also reported that they cannot focus and get lost in groups and are often unable to relate to other members. Several patients described how group treatment did not address their needs, with group content becoming stale and restrictive.

Patients described the abstinence policy of conventional SUD treatment as an inflexible ‘pass or fail’ approach to evaluating treatment progress that resulted in them feeling negatively judged and discarded. Patients expressed the belief that in conventional SUD treatment there is a perception that if you are not sober you are not trying.

Perceived facilitators of CMM services

Patients’ responses to queries regarding their experiences with CMM fell into four subthemes: personalized care, individual appointments, team-based and treatment focus.

Patients described CMM as personalized treatment that was responsive to their needs, allowed them to have input in treatment decisions and was adaptive/flexible. Specific examples noted by patients included accommodating scheduling, an open door policy and assistance with personal matters (e.g. filling out paperwork, making phone calls). Individual appointments were an appealing component of CMM and described as both a necessary part of their recovery and a special treatment opportunity. Further, patients reported feeling more comfortable opening up and talking about personal concerns during these appointments. Patients noted their need to receive support from everyone on the team and reported that the team-based approach provided a supportive foundation.

With regard to treatment focus, patients reported feeling less pressured to abstain from substances, as compared to experiences in conventional SUD treatment, and appreciative of the opportunity to remain in treatment even if substance use occurred.

Relational factors

The patient-provider relationship emerged as an important theme throughout the interviews. Subthemes included: familiarity with providers, providers caring/taking an interest in them and trusting CMM providers.

Several patients discussed their level of familiarity with CMM providers based on prior treatment experiences with them, as many had a long history with the treatment system. Patients attributed their comfort with providers to these experiences.

A majority of patients also described CMM providers as caring and interested in them as persons. This sub-theme recurred throughout interviews, but notably was observed when patients were asked about CMM services considered helpful to their recovery. Patients noted these attributes helped them feel listened to and understood and contributed to a belief that providers were concerned about their welfare and genuinely interested in them. Patients also referred to time and effort providers devoted to calling them and responding to their voicemails as additional examples of providers’ concern.

Patients reported feeling a level of trust with providers, which they defined as being able to safely address their concerns or issues without fear of being judged.

Patient factors

When responding to the questions addressing engagement in CMM, patients identified personal psychosocial factors that serve as either barriers or facilitators. Not wanting to disappoint CMM providers was reported as a facilitator to continued engagement. Barriers to remaining in treatment included exposure to individuals who use substances and lack of motivation or personal responsibility.

Program Refinement

Patients identified CMM services that needed to be enhanced or highlighted at treatment onset. Services that needed to be enhanced were related to outreach attempts including more phone calls, letters and outreach in the community (e.g. home visits). Patients also requested assistance with resources such as housing and transportation, noting that these services are necessary for continued engagement. Further, patients identified a need for help arranging outside activities, including employment or volunteer work.

Discussion

Although widely recommended for reducing health care costs of high cost patients, this study represents one of the few studies that have assessed patients’ perspectives about and experience with a care management approach that was adapted for treatment of complex SUD and high healthcare utilization. Our findings regarding barriers to conventional SUD treatment have been reported infrequently in the addiction literature, perhaps because research rarely seeks input from patients about their experiences in SUD treatment. However, prior research with Veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan noted a strong preference for individual over group mental health treatments.[50] Though not commonly reported in the addiction literature, strict program rules, such as abstinence, have been reported by patients with serious mental illness and co-occurring substance use problems as a barrier to recovery.[27] Of particular concern were patients’ reports of feeling as though they were “failures”‘ and “discarded” by the treatment program, if they did not comply with program rules. When programs are perceived by consumers as hindering the recovery process, changes in policy are likely needed. Few medical conditions are viewed with as much stigma as substance use disorders, a view that has negative implications for those in need of care.[51, 52] Stigma is associated with delayed treatment seeking, treatment dropout, and dimished self-esteem/self-efficacy and potentially impairs recovery.[53–56] Thus, it may be especially important for patients who have been difficult to engage in treatment to have opportunities to participate in flexible treatments such as the CMM. Indeed, patients included in this study were not engaged in standard care and accessing high cost services, suggesting that a different approach to care is indicated.

Consistent with prior studies, our findings also highlight the importance of the patient-provider relationship in the context of SUD treatment.[39] Patients specifically identified “trust” in providers as a factor contributing to engagement in CMM services, a component of the patient-provider relationship that has received little attention in the SUD treatment literature, but has been reported in the hepatitis C and human immunodeficiency virus treatment literatures among patients with comorbid drug use conditions,[57, 58] as well as patients in assertive community-based and other mental health treatments.[59–61] Trust in providers may be particularly important for stigmatized and marginalized populations, such as those with complex SUDs, and yet more difficult to achieve because of prior negative health care experiences, vulnerabilities and greater risks associated with misplaced trust.[62] Theories of trust further suggest that familiarity is involved in determining whether to trust another individual or not, a relationship that appears to be supported in patients’ reports that familiarity with providers of CMM services was important to their treatment engagement.[63] Although familiarity was identified as a facilitator to treatment engagement, it is important to note that length of patient-provider relationship is weakly associated with trust[64] and can also serve as a barrier, if prior experiences with a provider fostered distrust.[29]

One of the more striking findings was the value patients placed on interactions with CMM providers. Although interviews queried patients about CMM services that were helpful, with the exception of individual appointments, few specific services were identified. Instead, patients highlighted the importance of feeling listened to, understood and cared for and how these qualities fostered a perception that providers were genuinely interested in them. Similar findings have been reported among patients with extended and prior engagement in assertive community-based treatment and recovery from serious mental illness.[59, 60, 65] These qualities appear to represent constructs related to empathy and the patient-provider alliance. Interestingly, prior research with patients with multiple chronic health diseases has referred to this finding as an unanticipated benefit or reward of care management interventions.[66] Similar findings have also been reported in the psychotherapy literature, suggesting these qualities are of critical importance to clinical outcomes.[67] Meta-analyses on factors associated with psychotherapy outcomes consistently report the largest effects for empathy and the provider-alliance, even larger than those observed for treatments.[68] Because CMM offers more opportunities for patients to interact individually with team members, it is possible that the CMM fosters development of positive patient-provider relationships more efficiently than conventional SUD treatment, which is typically delivered in group interactions.

Our findings have several clinical and policy implications for care management interventions for patients with complex SUDs. Although not intentional, program policies that require abstinence or even the legacy of such policies given that many of these patients have previous involvement in VA treatment may prevent or delay patients’ reengagement with treatment and overall recovery. In the context of evidence suggesting that self-efficacy and motivation are associated with modest improvements in substance use outcomes, feelings of rejection and shame likely reduce the likelihood of successful recovery, particularly among those patients with complicated SUD histories.[68–70] Although often underappreciated, our findings that highlight the potential impact of a patient-provider alliance on patients’ engagement in CMM services suggest that factors supportive of the alliance, such as provider empathy should be considered in selecting care management providers. Further, monitoring therapeutic alliance and provider empathy, which are associated with treatment retention and drinking outcomes,[39, 71] could occur using patient-completed questionnaires throughout treatment to make adjustments to patient/provider relationships and provider behaviors as needed.[44]

Our study has several limitations. Data were obtained from patients who agreed to participate in a study assessing the feasibility of a care management approach and results are reflective only of patients who completed qualitative interviews. Although the demographic and clinical characteristics are mostly representative of the larger population of VA patients,[72] the sample was small, recruited from a single VA and did not include women. Thus, results may not generalize to women receiving care in the VA or to the larger group of patients in other VA or non-VA health care systems. Interviews were conducted at 1- and 3-months after baseline and thus interpretations are limited to patients’ early experiences in treatment. Further, perspectives are limited to patients and do not reflect those of important stakeholders, such as CMM providers and clinical leaders, which may differ from or contradict those of patients. In addition, the cost-effectiveness of CMM relative to standard SUD treatment is unknown.

CMM may be more appealing and effective at engaging patients with complex substance use conditions and persistent high health care utilization than conventional SUD treatments that rely on group therapy and adhere to strict program policies. Patients’ responses suggested a preference for individual encounters with therapists, flexible programming, team-based approach and patient-centered care, treatment elements that are more consistent with care management approaches. Further, responses highlight the importance of patient-provider relationships to engagement, especially patients’ trust in providers and beliefs that providers cared for them as persons. Greater outreach efforts, improved communication about specific services and assistance with housing and transportation were identified as potential facilitators to engagement in CMM services. This study was limited to 12 months of treatment due to funding constraints. Future research is required to determine whether the effectiveness of CMM differs by different time frames, or whether particular milestones could be used to determine when patients may return to care as usual. Research also is needed to assess whether CMM improves engagement, retention, and clinical outcomes in the short and long-term relative to standard care among those with complex SUDs and persistent high health care utilization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors wish to thank Meghan Deal, MSW, Nicholas Barry, MSW and Joseph Reoux, MD for their invaluable assistance with this project.

Funding & Support:

The project described was supported by the United States (U.S.) Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, the VA Center of Excellence in Substance Abuse Treatment & Education, and Pilot Project Award Number 1 I21 HX00147306-01A1 from the United States (U.S.) Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development. The funding sources had no such involvement in the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosures/Conflicts of Interest:

The authors report no relevant financial conflicts. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or University of Washington.

References

- 1.Yu W, et al. , Prevalence and costs of chronic conditions in the VA health care system. Med Care Res Rev, 2003. 60(3 Suppl): p. 146S–167S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Room R, Babor T, and Rehm J, Alcohol and public health. Lancet, 2005. 365(9458): p. 519–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moss HB, Chen CM, and Yi HY, Subtypes of alcohol dependence in a nationally representative sample. Drug Alcohol Depend, 2007. 91(2-3): p. 149–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McKay JR, Is there a case for extended interventions for alcohol and drug use disorders? Addiction, 2005. 100(11): p. 1594–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McLellan AT, et al. , Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA, 2000. 284(13): p. 1689–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawkins EJ, et al. , Prevalence, predictors, and service utilization of patients with recurrent use of Veterans Affairs substance use disorder specialty care. J Subst Abuse Treat, 2012. 43(2): p. 221–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Neighbors CJ, et al. , Medicaid care management: description of high-cost addictions treatment clients. J Subst Abuse Treat, 2013. 45(3): p. 280–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walley AY, et al. , Acute care hospital utilization among medical inpatients discharged with a substance use disorder diagnosis. Journal of Addiction Medicine, 2012. 6(1): p. 50–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grant BF, et al. , Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 2004. 61(8): p. 807–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodenheimer T and Berry-Millett R, Care management of patients with complex health care needs. Research Synthesis Report no 19. Princeton, NJ, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thomas-Henkel C, Hendricks T, and Church K, Opportunities to Improve Models of Care for People with Complex Needs: Literature Review. Health Care, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liaw W, et al. , Lessons for Primary Care from the First Ten Years of Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration Projects. J Am Board Fam Med, 2015. 28(5): p. 556–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd CM, et al. , A Pilot Test of the Effect of Guided Care on the Quality of Primary Care Experiences for Multimorbid Older Adults. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2008. 23(5): p. 536–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stewart S, Pearson S, and Horowitz JD, Effects of a home-based intervention among patients with congestive heart failure discharged from acute hospital care. Arch Intern Med, 1998. 158(10): p. 1067–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raven MC, et al. , An intervention to improve care and reduce costs for high-risk patients with frequent hospital admissions: a pilot study. BMC Health Serv Res, 2011. 11(1): p. 270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bell JF, et al. , A Randomized Controlled Trial of Intensive Care Management for Disabled Medicaid Beneficiaries with High Health Care Costs. Health Serv Res, 2015. 50(3): p. 663–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saitz R, et al. , Chronic care management for dependence on alcohol and other drugs: the AHEAD randomized trial. JAMA, 2013. 310(11): p. 1156–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McLellan AT, Carise D, and Kleber HD, Can the national addiction treatment infrastructure support the public’s demand for quality care? J Subst Abuse Treat, 2003. 25(2): p. 117–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.White WL, Recovery Management and Recovery-Oriented Systems of Care: Scientific Rationale and Promising Practices. 2008, Philadelphia: Northeast Addiction Tecnology Transfer Center, Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center, Philadelphia Department of Behavioral Health/Mental Retardation Services. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saitz R, et al. , The Case for Chronic Disease Management for Addiction. J Addict Med, 2008. 2(2): p. 55–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scott CK and Dennis ML, Results from two randomized clinical trials evaluating the impact of quarterly recovery management checkups with adult chronic substance users. Addiction, 2009. 104(6): p. 959–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Institute of Medicine, Improving the quality of mental health care for mental and substance-use conditions. Quality Chasm Series, ed. Committee on Crossing the Quality Chasm: Adaptation to Mental Health and Addictive Disorders. 2006, Washington DC: The National Academies Press. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodare H and Smith R, The rights of patients in research. British Medical Journal, 1995. 310(6990): p. 1277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parloff MB, Who will be satisfied by “consumer satisfaction” evidence? Behavior Therapy, 1983. 14(2): p. 242–246. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenhalgh T, et al. , Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Q, 2004. 82(4): p. 581–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith SM, et al. , How to design and evaluate interventions to improve outcomes for patients with multimorbidity. Journal of Comorbidity, 2013. 3(1): p. 10–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green CA, et al. , Dual recovery among people with serious mental illnesses and substance problems: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 2015. 11(1): p. 33–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bayliss EA, et al. , Understanding the context of health for persons with multiple chronic conditions: moving from what is the matter to what matters. Ann Fam Med, 2014. 12(3): p. 260–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mautner DB, et al. , Generating Hypotheses About Care Needs of High Utilizers: Lessons from Patient Interviews. Population Health Management, 2013. 16(S1): p. S26–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Webster F, et al. , Capturing the experiences of patients across multiple complex interventions: a meta-qualitative approach. BMJ, 2015. 5(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braveman P, Egerter S, and Williams DR, The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health, 2011. 32: p. 381–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laudet AB, Stanick V, and Sands B, What could the program have done differently? A qualitative examination of reasons for leaving outpatient treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat, 2009. 37(2): p. 182–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lorentz WJ, Scanlan JM, and Borson S, Brief screening tests for dementia. Can J Psychiatry, 2002. 47(8): p. 723–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saultz JW and Lochner J, Interpersonal continuity of care and care outcomes: a critical review. Ann Fam Med, 2005. 3(2): p. 159–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Walraven C, et al. , The association between continuity of care and outcomes: a systematic and critical review. J Eval Clin Pract, 2010. 16(5): p. 947–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carroll KM, et al. , Motivational interviewing to improve treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: A multisite effectiveness study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2005. 81(3): p. 301–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brunette MF and Mueser KT, Psychosocial interventions for the long-term management of patients with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorder. J Clin Psychiatry, 2006. 67 Suppl 7: p. 10–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rapp RC, et al. , Improving linkage with substance abuse treatment using brief case management and motivational interviewing. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2007. 94(1): p. 172–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meier PS, Barrowclough C, and Donmall MC, The role of the therapeutic alliance in the treatment of substance misuse: a critical review of the literature. Addiction, 2005. 100(3): p. 304–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Department of Veterans Affairs and Deparment of Defense. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Substance Use Disorders. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horsfall J, et al. , Psychosocial treatments for people with co-occurring severe mental illnesses and substance use disorders (dual diagnosis): a review of empirical evidence. Harv Rev Psychiatry, 2009. 17(1): p. 24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shimokawa K, Lambert MJ, and Smart DW, Enhancing treatment outcome of patients at risk of treatment failure: meta-analytic and mega-analytic review of a psychotherapy quality assurance system. J Consult Clin Psychol, 2010. 78(3): p. 298–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bellack AS, et al. , A randomized clinical trial of a new behavioral treatment for drug abuse in people with severe and persistent mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 2006. 63(4): p. 426–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McLellan AT, et al. , Reconsidering the evaluation of addiction treatment: from retrospective follow-up to concurrent recovery monitoring. Addiction, 2005. 100(4): p. 447–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sheehan DV, et al. , The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry, 1998. 59 Suppl 20: p. 22–33;quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sobell LC, et al. , Comparison of a quick drinking screen with the timeline followback for individuals with alcohol problems. J Stud Alcohol, 2003. 64(6): p. 858–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andrews G and Slade T, Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Australian and New Zeland journal of Public Health, 2001. 25(6): p. 494–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Braun V and Clarke V, Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 2006. 3(2): p. 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brooks J and King N. Qualitative psychology in the real world: The utility of template analysis. in 2012 British Psychological Society Annual Conference. 2012. London, UK: University of Huddersfield Repository. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kracen AC, et al. , Group Therapy Among OEF/OIF Veterans: Treatment Barriers and Preferences. Military Medicine, 2013. 178(1): p. e146–e149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van Boekel LC, et al. , Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend, 2013. 131: p. 23–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Room R, Stigma, social inequality and alcohol and drug use. Drug Alcohol Rev, 2005. 24(2): p. 143–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luoma JB, et al. , An investigation of stigma in individuals receiving treatment for substance abuse. Addict Behav, 2007. 32(7): p. 1331–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clement S, et al. , What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine, 2015. 45(1): p. 11–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ball SA, et al. , Reasons for dropout from drug abuse treatment: Symptoms, personality and motivation. Addict Behav, 2006. 31(2): p. 320–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keyes KM, et al. , Stigma and Treatment for Alcohol Disorders in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology 2010. 172(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harris M, Rhodes T, and Martin A, Taming systems to create enabling environments for HCV treatment: Negotiating trust in the drug and alcohol setting. Social Science & Medicine, 2013. 83: p. 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuchinad KE, et al. , A qualitative study of barriers to and facilitators of optimal engagement in care among PLWH and substance use/misuse. BMC Research Notes, 2016. 9(1): p. 229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Priebe S, et al. , Processes of disengagement and engagement in assertive outreach patients: qualitative study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 2005. 187(5): p. 438–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pettersen H, et al. , Engagement in assertive community treatment as experienced by recovering clients with severe mental illness and concurrent substance use. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 2014. 8(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Smith TE, et al. , Disengagement From Care: Perspectives of Individuals With Serious Mental Illness and of Service Providers. Psychiatric Services, 2013. 64(8): p. 770–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gilson L, Trust and the development of health care as a social institution. Social Science & Medicine, 2003. 56(7): p. 1453–1468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Luhmann N, Familiarity, Confidence, Trust: Problems and Alternatives. Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations, 2000. 6: p. 94–107. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hall MA, et al. , Trust in physicians and medical institutions: what is it, can it be measured, and does it matter? Milbank Q, 2001. 79(4): p. 613–39, v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Green CA, et al. , Understanding how clinician-patient relationships and relational continuity of care affect recovery from serious mental illness: STARS study results. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 2008. 32(1): p. 9–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Webster F, et al. , Capturing the experiences of patients across multiple complex interventions: a meta-qualitative approach. BMJ Open, 2015. 5(9): p. e007664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wampold BE, How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry, 2015. 14(3): p. 270–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Longshore D and Teruya C, Treatment motivation in drug users: a theory-based analysis. Drug Alcohol Depend, 2006. 81(2): p. 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Adamson SJ, Sellman JD, and Frampton CM, Patient predictors of alcohol treatment outcome: a systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat, 2009. 36(1): p. 75–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maisto SA, Connors GJ, and Zywiak WH, Alcohol treatment, changes in coping skills, self-efficacy, and levels of alcohol use and related problems 1 year following treatment initiation. Psychol Addict Behav, 2000. 14(3): p. 257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miller WR and Moyers TB, The forest and the trees: relational and specific factors in addiction treatment. Addiction, 2015. 110(3): p. 401–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Painter JM, et al. , Prevalence rates and predictors of high inpatient utilization among Veteran Health Administration patients with substance use disorders and co-occurring mental health conditions. Manuscript submitted for publication, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.