Abstract

This study examined perceived barriers to help-seeking as mechanisms by which masculinity may generate risk for psychiatric distress in men. An online sample of 558 men completed self-report measures of masculine discrepancy stress (i.e. distress about one’s perceived gender nonconformity), barriers to help-seeking, and psychiatric distress. A significant indirect effect of masculine discrepancy stress on psychiatric distress emerged through perceived barriers to help-seeking; notably, this effect was stronger among Men of Color (vs White men). The promotion of optimal psychiatric functioning in men may necessitate interventions that target the effects of masculine socialization and race-related stress on help-seeking attitudes.

Keywords: help-seeking, masculine discrepancy stress, masculinity, psychiatric distress, race

Introduction

Compared to women, men experience higher rates of externalizing psychiatric disorders (e.g. attention-deficit/hyperactivity, conduct, substance use, and antisocial disorders) and death by suicide (Affleck et al., 2018; Seedat et al., 2009). Beyond directly affecting the man in question, men’s psychiatric problems may also negatively impact families and broader social networks. The societal and interpersonal impact of men’s psychiatric distress is further compounded by evidence that men use health care services less (Mankowski and Smith, 2016) and hold more negative attitudes toward seeking professional help than women (Nam et al., 2010).

While the identification of epidemiological differences between men and women in mental health conditions and treatment behaviors is useful, a focus on sex or gender differences reveals little about the mechanisms of these differences. Nor does it take into account the variability in mental health processes and outcomes within groups (i.e. diversity that exists among men). Indeed disparities in men’s mental health exist as a function of racial identity, including greater chronicity of psychiatric disorders (Breslau et al., 2005), reduced access to and utilization of mental health services (Jones et al., 2018), and lower quality of accessed care (Mays et al., 2017; Minsky et al., 2003) among racial and ethnic minority (vs White) populations. However, models with the potential to elucidate psychosocial processes that may underlie gender-based differences yet manifest differently across men as a function of social context are lacking.

As such, the current study aims to contextualize extant models of men’s mental health by attending to the influence that socio-cultural constructions of masculinity have on men’s help-seeking attitudes and psychiatric distress. Specifically, the current study aims to (1) examine perceived barriers to help-seeking as mechanisms by which masculine socialization processes generate risk for psychiatric distress in men and; (2) assess the extent to which this risk varies across racial lines.

Masculinity and barriers to help-seeking

Consideration of the role of masculinity in shaping men’s psychiatric distress places models of men’s health behaviors and outcomes within a broader social-ecological context. Masculinity refers to the set of socially-prescribed rules within a particular culture governing the behavior, attributes, and attitudes of boys and men (Mosher and Tomkins, 1988; Thompson and Bennett, 2015). For example, in many cultures, prevailing norms hold that men should achieve social dominance, appear aggressive, be physically and emotionally strong, and avoid stereotypically feminine behaviors (Thompson and Pleck, 1995). Beliefs about how men should behave, feel, or act may influence men’s behavior to the extent that the behavior provides a means to express or establish one’s masculine self-image (Berke et al., 2018; Berke and Zeichner, 2016). Help-seeking attitudes and behaviors may provide one context for men to express socialized masculine beliefs. Research consistently indicates that stronger conformity to masculine norms is related to less favorable attitudes toward help-seeking (Seidler et al., 2016; Wong et al., 2017).

However, theoretical and empirical literature suggests that men’s gender-related stress may be more proximally related to psychiatric outcomes than the extent to which they adhere to traditional masculine norms (Good and Wood, 1995; Pleck, 1995; Reidy et al., 2018; Vandello and Bosson, 2013). Although most men violate masculine norms in some way (Pleck, 1995), boys and men learn to expect that deviation from prevailing societal standards of masculinity (i.e. gender role discrepancy) will result in social and/or physical reprisal (Moss-Racusin et al., 2010; Rummell and Levant, 2014). Given potential penalties for masculine gender role discrepancy, boys and men may experience masculine discrepancy stress, a form of gender role stress stemming from fear of being perceived as falling short of normative masculine expectations (Pleck, 1995; Reidy et al., 2014).

Masculine discrepancy stress has been linked with psychiatric maladjustment among adolescent boys (Reidy et al., 2018) as well as elevated anxiety symptoms (Yang et al., 2018) and difficulties with emotion regulation (i.e. a core underlying feature of psychiatric symptoms; Bekh Bradley et al., 2011; Berke et al., 2019) in samples of adult men. Importantly, masculine discrepancy stress is also associated with a range of stereotyped masculine behaviors over and above the effects of conformity to prescribed gender norms (e.g. aggression, riskier sexual behavior; Reidy et al., 2014, 2016). These data suggest that masculine discrepancy stress may motivate men to avoid behaviors (i.e. help-seeking) that are construed as a violation of masculine expectations in favor of behaviors that assert masculinity to themselves and others (Reidy et al., 2014, 2016; Vandello and Bosson, 2013). To the extent that help-seeking is construed as a violation of masculine ideals, masculine discrepancy stress may thwart adaptive help-seeking attitudes (Mahalik et al., 2003).

Importantly, negative attitudes toward help-seeking are a well-established barrier to help-seeking behavior. Data from global and U.S. epidemiological samples have found that among those with diagnosed mental disorders who recognized a need for treatment but did not get any, a majority (72.6%-96.3%) reported attitudinal barriers (e.g. wanting to handle issue on their own) as the most common reason for not seeking treatment (Andrade et al., 2014; Mojtabai et al., 2011). Thus, attitudinal barriers to help-seeking may ultimately prevent discrepancy-stressed men from receiving needed professional care. In this vacuum of care, psychiatric distress may emerge or worsen. As such, masculine discrepancy stress may lead to psychiatric maladjustment among men both directly and indirectly through its influence on help-seeking attitudes and attendant behavior (i.e. help-seeking avoidance).

Masculinity and help-seeking in the context of race

Societal standards of masculinity and resultant discrepancy stress may operate in tandem with social by-products of race and ethnicity to differentially influence help-seeking and mental health outcomes for Men of Color. First, culturally-specific values and norms intersect with masculine gender socialization to produce a variety of unique “multi-cultural masculinities” while rendering certain traditional masculine norms more salient than others for Men of Color (Connell and Messerschmidt, 2005; Nam et al., 2010). For example, Asian-American men appear to place a greater importance on emotional self-control than other hegemonic masculine norms (Kim and Lee, 2014); this may stem from culturally-specific values around saving face (Gong et al., 2003) and avoiding bringing shame to one’s family and community at large (Yang et al., 2008). Among Latino-American men, both “machismo” (i.e. hypermasculine stereotyped attitudes and behaviors) and “caballerismo” (i.e. emotional connectedness and chivalry) norms shape constructions of masculinity, with greater adherence to machismo norms predicting diminished help-seeking attitudes (Arciniega et al., 2008; Davis and Liang, 2015; Rivera-Ramos and Buki, 2011). Racially-specific constructions of masculinity among African American men tend to center on fulfilling the traditionally masculine “provide/protector” role in the context of familial and community relationships; this emphasis may be motivated by a desire to oppose structural racial oppression through collective, interdependent networks of support (Hammond and Mattis, 2005; Rogers et al., 2015).

Second, structural racial oppression —cumulative institutional pathways that indirectly reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources through inequitable systems of income, employment, education, and judicial treatment (Bailey et al., 2017)—may intersect with masculine norms to exacerbate low help-seeking attitudes and behaviors. A wide range of social and health inequities reflective of structural racism (e.g. limited access to employment-based insurance, residential housing segregation that adversely restricts healthcare access, utilization, and quality) disproportionately affect Men of Color in the U.S. (Bailey et al., 2017; Sohn, 2017). Finally, the impact of masculine discrepancy stress on barriers to help-seeking and concomitant psychiatric distress may operate differently for Men of Color than for White men as a consequence of interpersonal racism. Relative to White, non-Hispanic men, Men of Color experience unique stressors related to having a marginalized identity (i.e. racism, discrimination) both in their general day-to-day existence (Boutwell et al., 2017) and in the context of their engagement with healthcare settings (Abramson et al., 2015). Such experiences are predictive of medical care delays, nonadherence, diminished help-seeking, and elevated mistrust of the medical establishment among Men of Color (Casagrande et al., 2007; Cheatham et al., 2008; Hammond, 2010; LaVeist et al., 2000; Oakley et al., 2019; Powell et al., 2016).

Theoretical integration

Evidence suggests a direct link between stress that accompanies men’s concern about falling short of normative masculine expectations (i.e. masculine discrepancy stress) and elevations in psychiatric distress among boys and men (Berke et al., 2018, 2019; Yang et al., 2018). Theoretical and empirical support also exists for an indirect link between discrepancy stress and general psychiatric distress via increased barriers to help-seeking. Specifically, health behaviors and beliefs may be a context in which men who are distressed by their perceived gender role discrepancy signal and reaffirm their masculinity (Addis and Mahalik, 2003; Courtenay, 2000; Mahalik et al., 2003). Thus, discrepancy-stressed men may hold negative attitudes toward help-seeking that ultimately block receipt of care. Psychiatric distress may emerge as a function of this lack of care. To the extent that masculinity is racially constructed and operates synergistically with social by-products of race to produce additional barriers to help-seeking for Men of Color, the impact of masculine discrepancy stress on general psychiatric distress through barriers to help-seeking may vary as a function of race.

The current study aims to build on this empirical and theoretical rationale while addressing several key empirical and theoretical gaps that characterize prior work on masculinity, help-seeking, and men’s mental health. First, despite considerable evidence linking (1) masculinity to help-seeking barriers (Seidler et al., 2016; Wong et al., 2017) and (2) barriers to help-seeking with psychiatric distress (Möller-Leimkühler, 2002), there is a paucity of research that directly examines these constructs in conjunction with one another. Even fewer studies have accounted for the role of race in these processes (for notable exceptions see Hammond, 2012; Powell et al., 2016). In addition, the majority of studies examining men’s help-seeking utilize Fischer and Turner’s (1970) attitudes toward help-seeking scale (Mansfield et al., 2005), which does not measure specific barriers to help-seeking and is geared toward assessment of general, cross-situationally stable individual differences. As such, past research has been limited in its ability to account for variation in the specific presenting health problems and contexts in which men seek help (Mansfield et al., 2005). Finally, the bulk of prior work on the topic focuses on the adverse impact of rigid adherence to traditional masculine norms (Seidler et al., 2016; Wong et al., 2017). However, given that nonconformity to traditionally-prescribed masculine norms may only pose a threat to the mental health of gender role discrepant men who are distressed by their nonconformity (Reidy et al., 2018), masculine discrepancy stress may be a more proximal indicator of the consequences of masculinity on men’s mental health.

The current study addresses these aforementioned limitations and builds on previous research by: (1) assessing masculinity, barriers to help-seeking, and race in an integrated model of men’s psychiatric distress; (2) examining context-specific barriers to men’s use of health care; and (3) measuring distress associated with self-perceptions of deficient masculinity (i.e. masculine discrepancy stress). Several hypotheses were advanced to test these aims in a large community sample of men:

Hypothesis 1: Consistent with previous research (Berke et al., 2019; Reidy et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018), we predicted that men who report greater masculine discrepancy stress would report greater levels of general psychiatric distress.

Hypothesis 2: Given empirical evidence linking conformity to masculine norms with negative help-seeking attitudes (Seidler et al., 2016; Wong et al., 2017) and negative help-seeking attitudes with diminished help-seeking behavior (Andrade et al., 2014; Mojtabai et al., 2011), we predicted that the effect of masculine discrepancy stress on general psychiatric distress would be mediated by barriers to help-seeking (i.e. men who endorse greater masculine discrepancy stress would report greater perceived barriers to help-seeking, and, in turn, greater psychiatric distress).

Hypothesis 3: We predicted that the hypothesized mediational effect of barriers to help-seeking on the relationship between masculine discrepancy stress and general psychiatric distress would be stronger for Men of Color than for White men given the legacy of institutional racism on factors that influence health-related help-seeking (Suite et al., 2007). However, given the dearth of empirical research in this area, a priori hypotheses regarding where along the mediated pathway the social by-products of race exert their influence were not specified; these analyses were deemed exploratory.

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were 558 U.S. cis-gender men recruited through Amazon’s Mechanical Turk (MTurk) website (76.5% Caucasian, 6.6% Asian, 7.7% Black or African American, and 6.6% Hispanic/Latino). MTurk permits the collection of national data from individuals via an online method that proffers valid and reliable data with more diversity in samples than traditional convenience samples (Paolacci and Chandler, 2014). Only participants who were 18 years old and above, male, and native English speakers were eligible for enrollment. Eligible participants were compensated US$2.00 each for completion of the questionnaires. The university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved all study procedures.

Materials

Demographics survey.

Participants answered questions about age, gender, race, income, education level, and relationship status. A dichotomous race variable was computed by dummy coding White men and Men of Color (Hispanic or Latino, American Indian or Alaskan Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander).

Brief Symptom Inventory.

Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis and Spencer, 1993). The BSI is a self-report psychological assessment consisting of 53 symptom items across 9 dimensions: Somatization, Obsessive-Compulsive, Interpersonal Sensitivity, Depression, Anxiety, Hostility, Phobic Anxiety, Paranoid Ideation, and Psychoticism. In keeping with the university’s IRB ethics guidelines, the current study omitted three symptom items assessing suicidal and homicidal ideation from the original 53-item measure. Participants endorse the relevance of each symptom to their experience in the past week on 5-point scales from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely). A Global Severity Index (GSI) is calculated by averaging all item responses, with higher scores reflecting greater current levels of general psychiatric distress. The BSI has demonstrated good psychometric properties (Derogatis and Melisaratos, 1983). Excellent internal reliability was found for the 50-item measure used in the current study (α = 0.98).

Masculine Discrepancy Stress Scale.

Masculine Discrepancy Stress Scale (MDSS; Reidy et al., 2014). We used the 5-item Discrepancy Stress subscale of the MDSS, which measures the extent to which men are distressed by their own gender role discrepancy (i.e. masculine discrepancy stress). Participants rate their level of agreement with various statements regarding their experience of masculine discrepancy stress (e.g. “I worry that people judge me because I am not like the typical man”) on 7-point Likert scales that range from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree), with higher scores reflecting greater levels of masculine discrepancy stress. The Discrepancy Stress subscale exhibited good internal consistency within the current sample (α = 0.89) and has demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties in prior work (Reidy et al., 2014).

Barriers to Help Seeking Scale.

Barriers to Help Seeking Scale (BHSS; Mansfield et al., 2005). We used the 31-item BHSS to assess participants’ perceived barriers to seeking professional help for mental health concerns. Participants are presented with a hypothetical situation in which they are in pain and are then asked to rate the personal importance of 31 hypothetical reasons that someone might not seek help (e.g. “I’d feel better about myself knowing that I didn’t need help from others”) on 7-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (Not at all important) to 7 (Extremely important). The BHSS consists of five subscales: (1) Need for Control and Self-Reliance, (2) Minimizing Problems and Resignation, (3) Concrete Barriers and Distrust of Caregivers, (4) Privacy, and (5) Emotional Control. A total score was computed by adding together all items to create a total sum score with higher scores reflecting greater perceived barriers to help-seeking. Psychometric analyses have supported the factorial, construct, and criterion validity of the BHSS subscales (Mansfield et al., 2005). The BHSS total score demonstrated good internal consistency in the current sample (α = 0.97).

Analytic strategy

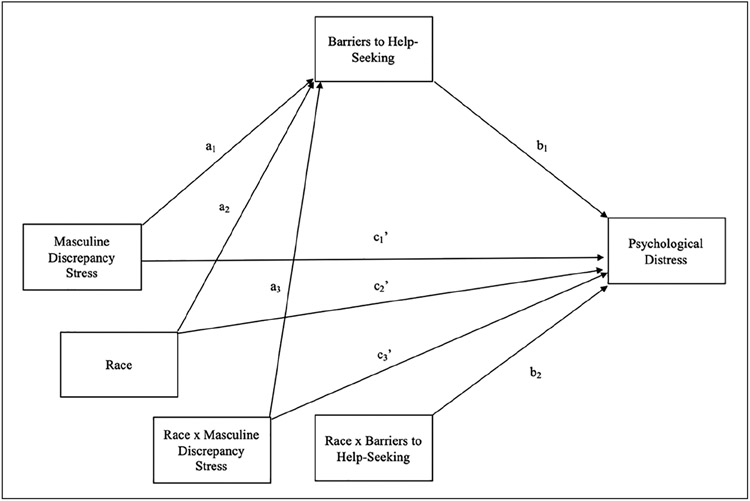

Data were modeled within a path analytic framework using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, 2017). The hypothesized models were tested using a two-step process. In the first step, a mediational model (Model 4 in Hayes, 2017) was constructed to estimate the direct and indirect effect of discrepancy stress on psychiatric distress through barriers to help-seeking. In the second step, a moderated mediation model (Model 59 in Hayes, 2017) was constructed to estimate the influence of race on this mediated path. See Figure 1 for the conceptual moderated mediation model. For all analyses, demographic variables (i.e. age, education level, income, sexual orientation, and relationship status) were included as planned covariates. As the products of regression coefficients are non-normally distributed, all analyses utilized 5,000 bootstrap resamples.

Figure 1. Conceptual model.

Note. Age, relationship status, education level, yearly income, and sexual orientation are not depicted in the conceptual model but were included as planned covariates in all statistical models.

Data sharing statement

De-identified individual participant data, including data dictionary, are available. This data includes all raw and calculated variables used in the present study for all participants deemed eligible for inclusion in analyses. The dataset, analytic code, and SPSS output file are available on FigShare.

Results

Data reduction and preliminary analyses

A total of 811 responses were collected. Participants were excluded from analyses if they withdrew consent (n = 18), were more than two standard deviations above the mean completion time of the survey (M = 43.22 minutes, SD = 67.65 seconds; n = 28), did not reach the end of the survey (n = 159), or were found to have completed the survey multiple times (n = 48). In cases where multiple submissions were found, the participant’s first submission, determined by date and time of completion, was kept. Thus, the final analytic sample comprised 558 participants with a mean duration time to complete the survey of 36.75 (SD = 18.51) minutes.

Table 1 displays descriptive statistics for the sample’s demographic characteristics. Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for pertinent study variables are displayed in Table 2. Consistent with Hypothesis 1, the bivariate association between masculine discrepancy stress and GSI was positive and statistically significant, r = 0.49, p < 0.01.

Table 1.

Sample descriptives for demographic variables.

| Demographic variables | Mean (SD) or % |

|---|---|

| Age | 33.97 (11.17) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 76.7 |

| Asian | 6.6 |

| Black or African American | 7.7 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 6.6 |

| Native Hawaiian or other | 0.2 |

| Pacific Islander | |

| American Indian or Alaskan | 0.7 |

| Native | |

| Other | 1.4 |

| Yearly household income | |

| <$5000–$24,999 | 25.3 |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 32.1 |

| $50,000–$99,999 | 34.6 |

| >$100,000 | 8.1 |

| Educational attainment | |

| <Some high school | 2.0 |

| High school graduate | 11.3 |

| Some college or vocational training | 34.8 |

| Four year college | 38.7 |

| Graduate or professional training | 13.3 |

| Current relationship status | |

| Single (never married) | 44.1 |

| Married (first marriage) | 36.6 |

| Remarried | 3.8 |

| Separated | 1.1 |

| Divorced | 4.1 |

| Long-term domestic partnership | 10.4 |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Straight | 92.1 |

| Gay | 2.2 |

| Bisexual | 4.7 |

| Transgender | 0.4 |

| Queer | 0.7 |

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of study variables.

| M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Race | — | — | — | 0.01 | 0.07 | 0.13* |

| 2. Masculine discrepancy stress | 11.84 | 6.70 | — | 0.26** | 0.49** | |

| 3. BHSS total | 107.16 | 41.27 | — | 0.36** | ||

| 4. GSI | 0.62 | 0.77 | — |

Note. BHSS: Barriers to Help Seeking Scale, GSI: Global Severity Index. Race: 0: Men of Color; 1: White men.

p ⩽ 0.01.

p ⩽ 0.001.

Step 1: Mediation.

Coefficients associated with the hypothesized mediation model are reported in Table 3. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, higher levels of masculine discrepancy stress predicted greater reported barriers to help-seeking; in turn, greater endorsement of barriers to help-seeking predicted greater levels of psychiatric distress. Bootstrap confidence intervals (CI) for the product of these paths that does not include zero provides evidence for an indirect effect of masculine discrepancy stress on GSI via barriers to help-seeking (ab = 0.052, 95% CI [0.028, 0.080]).

Table 3.

Model coefficients for mediation path analysis.

| Coefficients | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of masculine discrepancy stress on BHSS | 1.430 | 0.265 | [0.896, 1.946] |

| Effect of BHSS on GSI | 0.004 | 0.001 | [0.003, 0.006] |

| Direct effect of masculine discrepancy stress on GSI | 0.046 | 0.005 | [0.035, 0.056] |

| Indirect effects of masculine discrepancy stress on GSI via BHSS | 0.052 | 0.014 | [0.028, 0.080] |

Note. Bolded values indicate significance of p < 0.05. BHSS: Barriers to Help-Seeking Scale Total Score; GSI: Global Severity Index; CI17: confidence interval.

Step 2: Moderated mediation.

The main effects of masculine discrepancy stress on barriers to help-seeking and of barriers to help-seeking on psychiatric distress remained significant after adjusting for race (Table 4). The interaction of race and barriers to help-seeking on psychiatric distress (path b2) was significant (β = 0.004, 95% CI [0.001, 0.008]). Explication of this interaction effect for Men of Color versus White men revealed that the strength of the association between barriers to help-seeking and psychiatric distress varied as a function of race (see Figure 2). Although barriers to help-seeking were found to significantly predict psychiatric distress for both White men and Men of Color, the magnitude of this association was stronger for Men of Color. Race did not moderate the relationship between masculine discrepancy stress and barriers to help-seeking (path a3) or masculine discrepancy stress and psychiatric distress (path c3’).

Table 4.

Model coefficients for moderated mediation path analysis.

| Coefficients | SE | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effects on barriers to help seeking | |||

| (a1) Masculine discrepancy stress | 1.254 | 0.328 | [0.599, 1.867] |

| (a2) Race | −3.452 | 8.257 | [−19.761, 12.727] |

| (a3) Masculine discrepancy stress * race | 0.684 | 0.542 | [−0.370, 1.750] |

| Effects on GSI | |||

| (b1) Barriers to help-seeking | 0.003 | 0.001 | [0.002, 0.005] |

| (b2) Barriers to help-seeking * race | 0.004 | 0.002 | [0.000, 0.008] |

| (c1’) Masculine discrepancy stress | 0.043 | 0.006 | [0.031, 0.055] |

| (c2’) Race | −0.381 | 0.187 | [−0.750, −0.013] |

| (c3’) Masculine discrepancy stress * race | 0.010 | 0.012 | [−0.013, 0.033] |

| Conditional direct effect of DS on GSI | |||

| (c1’ + c3’*White men) | 0.043 | 0.005 | [0.033, 0.052] |

| (c1’ + c3’*Men of Color) | 0.053 | 0.008 | [0.037, 0.069] |

| Conditional Indirect Effects of DS on GSI via BHSS | |||

| (a1 + a3* White men) (b1 + b2*White men) | 0.004 | 0.002 | [0.001, 0.007] |

| (a1 + a3* Men of Color) (b1 + b2*Men of Color) | 0.014 | 0.005 | [0.006, 0.024] |

| Index of moderated mediation (difference of conditional effects) | 0.010 | 0.005 | [0.002, 0.020] |

Note. Letters in parentheses refer to regression paths in Figure 1. Bolded values indicate significance of p < 0.05. BHSS: Barriers to Help-Seeking Scale Total Score; DS: discrepancy stress; GSI: Global Severity Index; CI: confidence interval.

Figure 2. Moderating effect of race on the association between barriers to help-seeking and psychiatric distress.

Note. BHSS: Barriers to Help-Seeking Scale Total Score; GSI: Global Symptom Index of the Brief Symptom Inventory.

Investigation of conditional indirect effects revealed that race also moderated the indirect effect of masculine discrepancy stress on psychiatric distress via BHSS (Table 4). Results revealed a significant effect of masculine discrepancy stress on psychiatric distress via barriers to help-seeking for both Men of Color and White men. However, a significant index of moderated mediation emerged (Index = 0.01; 95% CI [0.002, 0.020]), indicating that the indirect effect from masculine discrepancy stress to psychiatric distress via barriers to help-seeking was stronger among Men of Color (vs White men).

Discussion

The overall goals of the current study were to (1) examine perceived barriers to help-seeking as mechanisms by which masculinity may generate risk for psychiatric distress in men, and (2) assess the extent to which this risk is culturally shaped and maintained by contextual cues and structural resources across racial lines. Specifically, we extended previous models of men’s psychiatric distress by evaluating associations among masculine discrepancy stress, perceived barriers to help-seeking, and race in an integrated model. Results indicate that men who are concerned that they deviate from prescribed gender role expectations were more likely to report attitudinal barriers to help-seeking; in turn, these men reported higher levels of psychiatric distress. However, relative to White men, help-seeking barriers were associated with more pronounced psychiatric distress for Men of Color.

Consistent with Hypothesis 1, we found a significant positive effect of masculine discrepancy stress and psychiatric distress at the bivariate level. Although there exists a sizeable body of previous research linking masculinity to adverse mental health outcomes (for a metaanalysis see Wong et al., 2017), this research has traditionally focused on men who strongly adhere to traditional gender norms. Findings from the current study add to the burgeoning body of quantitative data (Berke et al., 2019; Reidy et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2018) demonstrating that men who fall short of these norms may also be at increased risk of psychiatric maladjustment.

Importantly, this study is the first to demonstrate associations between masculine discrepancy stress and perceived barriers to help-seeking. Men who are concerned that they are violating prevailing expectations of what is means to “be a man” reported greater perceptions of context-specific barriers to help-seeking, including attitudinal, interpersonal, and structural impediments to help-seeking. These findings suggest that masculine discrepancy stress may activate traditional attitudes that construe help-seeking and/or health problems as a violation of masculine norms prescribing social dominance, self-reliance, and physical and emotional toughness (Thompson and Pleck, 1995). Masculine discrepancy stress may also inform men’s evaluation of available social and structural resources available to address their psychological and/or physical health needs.

In keeping with Hypothesis 2, significant indirect effects emerged from masculine discrepancy stress to psychiatric distress via perceived barriers to help-seeking. For men who experience distress in relation to perceived violations of masculine expectations, concerns about the ability to access treatment may understandably generate or exacerbate psychiatric distress, particularly if these concerns block men from seeking and/or receiving needed professional care. Likewise, as violations of masculine norms are often punished with physical threat or social condemnation (Moss-Racusin et al., 2010; Rummell and Levant, 2014), men who believe that help-seeking threatens traditional masculine expectations (i.e. of autonomy, emotional control, toughness) may fear social sanction should they seek help. This form of gender role stress may directly generate psychological distress. It may also indirectly impede psychiatric well-being by motivating discrepancy-stressed men to avoid attending to physical/psychiatric pain as a means of reasserting masculine status. Although such a response may proximally alleviate masculine discrepancy stress for men in the short-term, in the long-term, such barriers to help-seeking behavior may confer distal risk for psychiatric maladjustment (O’Brien et al., 2005).

Consistent with Hypothesis 3, we found that the indirect effect of masculine discrepancy stress on psychiatric distress via perceived barriers to help-seeking was significantly stronger among Men of Color (vs White men). Specifically, we found that the association between perceived barriers to help-seeking and psychiatric distress were exacerbated among Men of Color, relative to White men. These findings suggest that societal standards of masculinity and resultant masculine discrepancy stress may operate in tandem with social by-products of race and ethnicity to exacerbate the role of perceived barriers to help-seeking on mental health outcomes for Men of Color. It is likely that such processes contribute to the lower rates of help-seeking observed among men from non-majority relative to majority cultural backgrounds (Chandra et al., 2009). Our findings also point to the need to move beyond measurement of gender prescriptions in predominantly White, non-Hispanic samples to mutually consider the impact of race-related factors on help-seeking motivations and health outcomes of Men of Color (Hammond, 2012; Powell et al., 2016).

Although more research is needed to investigate mechanisms by which race-related factors exacerbate pathways linking perceived barriers to help-seeking psychiatric distress, it is likely that these effects are exerted across multiple psychosocial levels. For example, the effects of race observed in the current study may reflect culturally-specific group-level differences in the values and norms of masculinity internalized by Men of Color (Davis and Liang, 2015; Kim and Lee, 2014; Rogers et al., 2015). They may also reflect the broader legacy of institutional racism on factors that influence health-related help-seeking including inequitable systems of housing, education, employment, earnings, etc. that reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources (Bailey et al., 2017; Suite et al., 2007). Finally, the race effects observed in the current study may reflect the intrapersonal impact of chronic experiences of interpersonal and systematic racism that Men of Color face (Casagrande et al., 2007; Cheatham et al., 2008; Powell et al., 2016). Overall, results from the current study highlight the importance of considering the intersecting role of both gender- and race-related stressors in examining the mental health implications of men’s help-seeking attitudes.

Limitations

Study findings should be evaluated in light of several limitations. First, given the design of this study, causal determinations cannot be made about interrelations among assessed variables. Research employing longitudinal and experimental designs is needed to establish whether intervening to reduce men’s experience of gender discrepancy stress and/or challenge traditional masculine norms that proscribe help-seeking may mitigate help-seeking barriers and reduce subsequent mental health risk.

Second, although we measure attitudes and barriers to help-seeking, we did not measure actual help-seeking behaviors. Compared to research on help-seeking attitudes, a substantial body of work is yet to be conducted on the latter. Research that examines the intersecting contributions of gender and race-related stressors on help-seeking behavior and healthcare utilization is especially lacking and constitutes an important direction for future research.

Third, due to the use of a dichotomous race variable, all Men of Color were analyzed together; we were not able to assess differences among African Americans, Latinos, Asians, American Indians, and Native Hawaiians. Given the paucity of data regarding between- and within-group variation in how masculinity is understood and expressed among Men of Color and the implications of such differences on help-seeking and psychological well-being, future research assessing these questions in a large and diverse sample of Men of Color is necessary.

Finally, our use of quantitative measures to assess gender and race-related constructs do not capture the full diversity of men’s experience or the ways that specific health behaviors and outcomes may be shaped by intersecting aspects of identity (Bowleg, 2008). Rich heterogeneity exists among men in terms of race, sexual orientation, gender expression, disability status, and other key dimensions of identity. These social identities may contribute in unique and synergistic ways to shape how men experience and perform masculinity (American Psychological Association, 2018). Quantitative measures of race and masculinity may neglect, miss, or misrepresent the numerous external and situational factors that shape expressions of masculinity among Men of Color (Griffith et al., 2012). Qualitative or mixed methods approaches may be better suited than exclusively quantitative studies to explore the impact of gender, race, and their mutual intersection with other aspects of identity on men’s help-seeking attitudes and mental health.

Implications and conclusions

Despite these limitations, results from the current study are of considerable theoretical and practical significance. Numerous scholars have called for a framework for understanding the relationship between masculinity and health that accounts for individual differences in perception and health-related choices as well as the social structures that shape health behaviors and outcomes (Addis and Mahalik, 2003; Griffith et al., 2012; Smiler, 2004). However, few studies have examined contextually bound mechanisms of mental health outcomes in men who perceive themselves to be in violation of masculine expectations. Moreover, Men of Color are all but invisible in this literature. Findings from the current study illustrate the value of attending to the intersecting influence of social by-products of race and gender on health-related perceptions and outcomes. Specifically, results suggest that the psychiatric health risk posed by the ongoing pressure for men to be viewed as sufficiently masculine, may be accounted for, in part, by the activation of perceived barriers to help-seeking among discrepancy stressed men. Importantly, this risk may be more pronounced for Men of Color.

In terms of practical implications, our findings suggest that promoting optimal psychiatric functioning in men necessitates interventions that address and challenge the ways in which social pressures to feel, think, and act “like a man” impede access to and engagement with healthcare professionals. Consistent with recent guidelines for psychology practice with boys and men (American Psychological Association, 2018), results from the current study suggest that accounting for the stress men may experience while trying to conform to traditional masculinity could enhance health promotion programming. Boys and men are bombarded daily by messages from society about what it means to be a man (Berke et al., 2018). At the same time, racial discrimination is entrenched within the social structures in which men live and obtain healthcare (Powell et al., 2016). As such, the development of public health strategies that reach outer level contexts (e.g. media, politics) are of chief necessity.

Our findings suggest that it may be especially important to target barriers to help-seeking for Men of Color. Men of Color face both gender-related stress as well as stressors shaped by the social-by-products of race and ethnicity, including interpersonal and systemic racism. As such, attending to the impact of gender socialization on Men of Color in isolation of race-related factors is likely to result in missed opportunities to understand and intervene to alleviate help-seeking barriers and attendant psychiatric distress (Griffith et al., 2012). Our results suggest that practitioners and researchers committed to redressing disparities in psychiatric health among men work to better understand and address the ways in which gender- and race-related factors work in tandem across social systems to hinder access to professional help and optimal psychiatric functioning.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Abramson CM, Hashemi M and Sánchez-Jankowski M (2015) Perceived discrimination in US healthcare: Charting the effects of key social characteristics within and across racial groups. Preventive Medicine Reports 2: 615–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addis ME and Mahalik JR (2003) Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. American Psychologist 58(1): 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Affleck W, Carmichael V and Whitley R (2018) Men’s mental health: Social determinants and implications for services. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 63(9): 581–589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association (2018) APA Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Boys and Men. Washington DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade LH, Alonso J, Mneimneh Z, et al. (2014) Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the WHO World Mental Health surveys. Psychological Medicine 44(6): 1303–1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arciniega GM, Anderson TC, Tovar-Blank ZG, et al. (2008) Toward a fuller conception of Machismo: Development of a traditional Machismo and Caballerismo Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology 55(1): 19. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, et al. (2017) Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: Evidence and interventions. Lancet 389 (10077): 1453–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekh Bradley D, DeFife JA, Guarnaccia C, et al. (2011) Emotion dysregulation and negative affect: Association with psychiatric symptoms. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 72(5): 685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke DS, Reidy D and Zeichner A (2018) Masculinity, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: A critical review and integrated model. Clinical Psychology Review 66: 106–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke DS, Reidy DE, Gentile B, et al. (2019) Masculine discrepancy stress, emotion-regulation difficulties, and intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 34(6): 1163–1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berke DS and Zeichner A (2016) Man’s heaviest burden: A review of contemporary paradigms and new directions for understanding and preventing masculine aggression. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 10(2): 83–91. [Google Scholar]

- Boutwell BB, Nedelec JL, Winegard B, et al. (2017) The prevalence of discrimination across racial groups in contemporary America: Results from a nationally representative sample of adults. PloS One 12(8): e0183356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowleg L (2008) When Black+ lesbian+ woman ≠ Black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles 59(5–6): 312–325. [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Kendler KS, Su M, et al. (2005) Lifetime risk and persistence of psychiatric disorders across ethnic groups in the United States. Psychological Medicine 35(3): 317–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casagrande SS, Gary TL, LaVeist TA, et al. (2007) Perceived discrimination and adherence to medical care in a racially integrated community. Journal of General Internal Medicine 22(3): 389–395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Scott MM, Jaycox LH, et al. (2009) Racial/ethnic differences in teen and parent perspectives toward depression treatment. Journal of Adolescent Health 44(6): 546–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheatham CT, Barksdale DJ and Rodgers SG (2008) Barriers to health care and health-seeking behaviors faced by Black men. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners 20(11): 555–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell RW and Messerschmidt JW (2005) Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender & Society 19(6): 829–859. [Google Scholar]

- Courtenay WH (2000) Constructions of masculinity and their influence on men’s well-being: A theory of gender and health. Social Science and Medicine 50(10): 1385–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis JM and Liang CT (2015) A test of the mediating role of gender role conflict: Latino masculinities and help-seeking attitudes. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 16(1): 23. [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR and Melisaratos N (1983) The brief symptom inventory: An introductory report. Psychological Medicine 13(3): 595–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derogatis LR and Spencer P (1993) Brief Symptom Inventory: BSI. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer EH and Turner JI (1970) Orientations to seeking professional help: Development and research utility of an attitude scale. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 35: 79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong F, Gage SJL and Tacata LA, Jr. (2003) Helpseeking behavior among Filipino Americans: A cultural analysis of face and language. Journal of Community Psychology 31(5): 469–488. [Google Scholar]

- Good GE and Wood PK (1995) Male gender role conflict, depression, and help seeking: Do college men face double jeopardy? Journal of Counseling & Development 74(1): 70–75. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DM, Gunter K and Watkins DC (2012) Measuring masculinity in research on men of color: Findings and future directions. American Journal of Public Health 102(S2): S187–S194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WP (2010) Psychosocial correlates of medical mistrust among African American men. American Journal of Community Psychology 45(1–2): 87–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WP (2012) Taking it like a man: Masculine role norms as moderators of the racial discrimination–depressive symptoms association among African American men. American Journal of Public Health 102(S2): S232–S241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WP and Mattis JS (2005) Being a man about it: Manhood meaning among African American men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 6(2): 114. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF (2017) Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd edn. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones AL, Cochran SD, Leibowitz A, et al. (2018) Racial, ethnic, and nativity differences in mentalhealth visits to primary care and specialty mental health providers: Analysis of the medical expenditures panel survey, 2010–2015. Healthcare 6(2): 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim PY and Lee D (2014) Internalized model minority myth, Asian values, and help-seeking attitudes among Asian American students. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 20(1): 98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ and Bowie JV (2000) Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Medical Care Research and Review 57(1 Suppl): 146–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalik JR, Good GE and Englar-Carlson M (2003) Masculinity scripts, presenting concerns, and help seeking: Implications for practice and training. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice 34(2): 123. [Google Scholar]

- Mankowski E and Smith R (2016) Men’s mental health and masculinities. In Friedman HS (ed.) Encyclopedia of Mental Health, 2 edn., vol. 3, pp. 66–74. Waltham, MA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield AK, Addis ME and Courtenay W (2005) Measurement of men’s help seeking: development and evaluation of the barriers to help seeking scale. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 6(2): 95. [Google Scholar]

- Mays VM, Jones A, Delany-Brumsey A, et al. (2017) Perceived discrimination in healthcare and mental health/substance abuse treatment among blacks, latinos, and whites. Medical Care 55(2): 173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minsky S, Vega W, Miskimen T, et al. (2003) Diagnostic patterns in Latino, African American, and European American psychiatric patients. Archives of General Psychiatry 60(6): 637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Sampson NA, et al. (2011) Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine 41(8): 1751–1761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möller-Leimkühler AM (2002) Barriers to help-seeking by men: A review of sociocultural and clinical literature with particular reference to depression. Journal of Affective Disorders 71(1–3): 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher DL and Tomkins SS (1988) Scripting the macho man: Hypermasculine socialization and enculturation. Journal of Sex Research 25(1): 60–84. [Google Scholar]

- Moss-Racusin CA, Phelan JE and Rudman LA (2010) When men break the gender rules: Status incongruity and backlash against modest men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 11(2): 140. [Google Scholar]

- Nam SK, Chu HJ, Lee MK, et al. (2010) A metaanalysis of gender differences in attitudes toward seeking professional psychological help. Journal of American College Health 59(2): 110–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien R, Hunt K and Hart G (2005) ‘It’s caveman stuff, but that is to a certain extent how guys still operate’: Men’s accounts of masculinity and help seeking. Social Science and Medicine 61(3): 503–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakley LP, López-Cevallos DF and Harvey SM (2019) The association of cultural and structural factors with perceived medical mistrust among young adult Latinos in rural Oregon. Behavioral Medicine 45(2): 118–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolacci G and Chandler J (2014) Inside the Turk: Understanding Mechanical Turk as a participant pool. Current Directions in Psychological Science 23(3): 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Pleck JH (1995) The gender role strain paradigm: An update. In Levant RF and Pollack WS (eds) A New Psychology of Men. New York: Basic Books, pp.129–163. [Google Scholar]

- Powell W, Adams LB, Cole-Lewis Y, et al. (2016) Masculinity and race-related factors as barriers to health help-seeking among African American men. Behavioral Medicine 42(3): 150–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy DE, Berke DS, Gentile B, et al. (2014) Man enough? Masculine discrepancy stress and intimate partner violence. Personality and Individual Differences 68: 160–164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy DE, Brookmeyer KA, Gentile B, et al. (2016) Gender role discrepancy stress, high-risk sexual behavior, and sexually transmitted disease. Archives of Sexual Behavior 45(2): 459–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy DE, Smith-Darden JP, Vivolo-Kantor AM, et al. (2018) Masculine discrepancy stress and psychosocial maladjustment: Implications for behavioral and mental health of adolescent boys. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 19(4): 560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Ramos ZA and Buki LP (2011) I will no longer be a man! Manliness and prostate cancer screenings among Latino men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 12(1): 13. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers BK, Sperry HA and Levant RF (2015) Masculinities among African American men: An intersectional perspective. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 16(4): 416. [Google Scholar]

- Rummell CM and Levant RF (2014) Masculine gender role discrepancy strain and self-esteem. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 15(4): 419. [Google Scholar]

- Seedat S, Scott KM, Angermeyer MC, et al. (2009) Cross-national associations between gender and mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Archives of General Psychiatry 66(7): 785–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler ZE, Dawes AJ, Rice SM, et al. (2016) The role of masculinity in men’s help-seeking for depression: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review 49: 106–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smiler AP (2004) Thirty years after the discovery of gender: Psychological concepts and measures of masculinity. Sex Roles 50(1–2): 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn H (2017) Racial and ethnic disparities in health insurance coverage: Dynamics of gaining and losing coverage over the life-course. Population Research and Policy Review 36(2): 181–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suite DH, La Bril R, Primm A, et al. (2007) Beyond misdiagnosis, misunderstanding and mistrust: relevance of the historical perspective in the medical and mental health treatment of people of color. Journal of the National Medical Association 99(8): 879. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EH Jr, and Bennett KM (2015) Measurement of masculinity ideologies: A (critical) review. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 16(2): 115. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EH Jr, and Pleck JH (1995) Masculinity ideologies: A review of research instrumentation on men and masculinities. In Levant RF and Pollack WS (eds) A New Psychology of Men. New York: Basic Books, pp.129–163. [Google Scholar]

- Vandello JA and Bosson JK (2013) Hard won and easily lost: A review and synthesis of theory and research on precarious manhood. Psychology of Men and Masculinity 14(2): 101. [Google Scholar]

- Wong YJ, Ho M-HR, Wang S-Y, et al. (2017) Metaanalyses of the relationship between conformity to masculine norms and mental health-related outcomes. Journal of Counseling Psychology 64(1): 80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LH, Phelan JC and Link BG (2008) Stigma and beliefs of efficacy towards traditional Chinese medicine and Western psychiatric treatment among Chinese-Americans. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 14 (1): 10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Lau JT, Wang Z, et al. (2018) The mediation roles of discrepancy stress and self-esteem between masculine role discrepancy and mental health problems. Journal of Affective Disorders 235: 513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]