Abstract

Borrelia crocidurae is an etiologic agent of relapsing fever in Africa and is transmitted to humans by the bite of soft ticks of the genus Ornithodoros. The role of the plasminogen (Plg) activation system for the pathogenicity of B. crocidurae was investigated by infection of Plg-deficient (plg−/−) and Plg wild-type (plg+/+) mice. No differences in spirochetemia were observed between the plg−/− and plg+/+ mice. However, signs indicative of brain invasion, such as neurological symptoms and/or histopathological changes, were more common in plg+/+ mice. Quantitative immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated infection of spirochetes in kidney interstitium and brain as soon as 2 days postinoculation. Lower numbers of extravascular spirochetes in plg−/− mice during the first days of infection suggested a less efficient invasion mechanism in these mice than in the plg+/+ mice. The invasion of the kidneys in plg−/− mice produced no significant inflammation, as seen by quantitative immunohistochemistry of the CD45 common leukocyte marker. However, significant kidney inflammation was observed with infection in the plg+/+ mice. In brain, inflammation was more severe in plg+/+ mice than in plg−/− mice, and the numbers of CD45+ cells increased significantly with duration of infection in the plg+/+ mice. The results show that invasion of brain and kidney occurs as early as 2 days after inoculation. Also, Plg is not required for establishment of spirochetemia by the organism, whereas it is involved in the invasion of organs.

Lyme disease and relapsing fever (RF) are caused by distinct species of Borrelia (3, 9). Lyme disease, most common in the Northern hemisphere, is caused by infection by, e.g., Borrelia burgdorferi, B. afzelii, and B. garinii, which are transmitted by the bite of hard-shelled Ixodes ticks. There are two types of RF, louse-borne and tick-borne RF. Louse-borne RF is induced by transmission of B. recurrentis by the crushing of feeding lice, and tick-borne RF is induced by transmission of, e.g., B. hermsii, B. duttonii, or B. crocidurae by the bite of soft-shelled Ornithodoros ticks (9). Lyme disease has been more extensively studied than RF and may involve several organ systems, most prominently the skin, nervous system, heart, and joints. Disease manifestations are induced by spirochete invasion of organ tissues, where Borrelia lipoproteins are likely to be involved in the early mechanisms of immune cell activation (29, 32, 45).

Unlike in Lyme disease, patients with RF experience one or more cycles of spirochetemia. Each cycle is characterized by a febrile period with microscopically visible spirochetemia lasting for 3 to 7 days, followed by nonfebrile periods of increasing lengths (18, 19, 40). The relapsing nature of the infection depends on the ability of the RF spirochetes to undergo antigenic variation, which has been studied in depth in the North American RF species B. hermsii (4, 7, 41). Similar to Lyme disease Borrelia, RF species also disseminate from the blood to many distant organs. Symptoms of brain invasion can include meningitis, focal deficits, hemiplegia, paraplegia, epilepsy, paresthesias, pains, pupillary abnormalities, peripheral and cranial neuritis, and myelitis (5, 24, 27, 31, 34, 42).

The mechanism by which Borrelia species enter blood and invade organs is still largely unknown. In higher vertebrates, plasminogen (Plg), the key component of the fibrinolytic system, can be converted to plasmin, a broad-spectrum serine protease, by the tissue-type Plg activator and the urokinase-type Plg activator (uPA) (6). In addition to fibrinolysis, plasmin-mediated proteolysis has been associated with many other biological processes, e.g., macrophage migration, tumor cell invasion, angiogenesis, and atherosclerosis (6). In vitro, a number of invasive bacteria have the ability to interact with the Plg activation system by binding plasmin(ogen) to the bacterial surface and/or by expressing endogenous Plg activators (12, 26). The activation of surface-bound Plg to plasmin is suggested to be a mechanism that enhances their ability to penetrate endothelium and tissue barriers. In addition, Plg binding may result in direct pathological effects due to the proteolytic activity of plasmin. Interestingly, besides the implication of Plg binding in bacterial pathogenicity, a recent study by Fischer and colleagues suggests that the binding of a pathological prion protein to Plg is of importance for pathogenicity in transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (20).

B. crocidurae was first isolated from the blood of a musk shrew in Senegal and was identified as the cause of endemic RF in western Africa (2, 11, 19, 28, 44), where it is considered a major cause of morbidity and neurologic disease (43). B. crocidurae organisms have the uncommon (among Borrelia species) ability to bind and cover themselves with erythrocytes, a phenomenon called erythrocyte rosetting, which is thought to result in a delayed immune response in the host (8). However, B. crocidurae shares with Lyme disease agents (i.e., B. burgdorferi) the ability to activate the adhesion molecules on the endothelium (35, 36), which could be a key pathophysiologic mechanism in B. crocidurae-induced vascular damage (37, 38). In this study, we investigated the role of host-derived Plg in the ability of B. crocidurae to produce spirochetemia and disseminate to organs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and bacterial strain.

B. crocidurae was obtained from Alan G. Barbour (Irvine, Calif.), cloned by limiting dilution to serotype 2, and subsequently used in the infection experiments (8). BALB/c mice (Bomholtgård, Ry, Denmark) were used for passage of spirochetes from −80°C to C57BL/6J mice. Adult Plg-deficient (plg−/−) and Plg wild-type (plg+/+) mice, generated from Plg-heterozygous (plg+/−) breeding pairs, were used for the infection experiments. The plg−/− mice were generated by Carmeliet et al. (11) and genotyped by a rapid chromogenic assay and PCR as described by Ny et al. (30).

Dose-dependent coating of B. crocidurae with plasmin.

Plasmin labeling of spirochetes was done as described earlier (14). Briefly, B. crocidurae organisms were cultivated and passaged at least four times in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelly medium II supplemented with 10% gelatin but without rabbit sera. Spirochetes were removed from the medium by centrifugation at 7,000 × g for 20 min. The pellet was resuspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) and divided into aliquots. One tube received 0.2 mg of Plg (Biopool, Umeå, Sweden)/ml and 10 ml (30 IU) of uPA, purchased from Sigma (plasmin labeled). A second tube received only Plg (Plg labeled), and a third tube received only uPA (uPA labeled). The fourth tube received HBSS only (untreated). Another tube (sham) contained Plg and uPA but no spirochetes. All samples were incubated 90 min at 32°C prior to three washes with HBSS and addition of FlavigenPli (Biopool), a chromogenic plasmin substrate. After incubation for 60 min at 32°C, the samples were centrifuged and supernatants were placed in a 96-well plate. The absorbance was read immediately at 410 nm with an MR700 microplate reader (Dynatech Laboratories, Chantilly, Va.).

Experimental infection.

For revival of frozen B. crocidurae, a passage in mice was performed prior to the animal experiments. Four BALB/c mice were infected intraperitoneally with approximately 107 spirochetes. Spirochetemias were monitored by microscopy of blood sampled daily from the tails. When the spirochetemia was pronounced, blood was collected in citrate buffer (0.11 M sodium citrate) by cardiac exsanguination under anesthesia (Dormicum [Roche, Basel, Switzerland] and Hypnorm [Janssen, Saunderton, United Kingdom]). Spirochetes were collected by removing supernatants after centrifugation of citrated blood for 5 s at 8,000 × g and two washes with 500 μl of PBS (0.02 M phosphate-buffered saline, pH 7.4). Samples were diluted with PBS, and 15 plg−/− and 15 plg+/+ mice were each inoculated subcutaneously with 0.1 ml containing 105 B. crocidurae organisms. Five uninfected mice of each category were included as controls. Blood was sampled from the tail each day for 14 days, diluted 1:10 in citrate buffer, and spirochetes were quantified in a Petroff-Hausser chamber using light microscopy. A spirochete was considered positive for rosette formation when it was attached to at least one erythrocyte. The mice were examined daily for visible neurological symptoms of Borrelia infection, as determined by the inability to coordinate movements when lifted by the tail and/or swimming inability (10, 38, 39). At day 0 postinoculation (p.i.), the uninfected mice were anaesthetized as described above and sacrificed by cardiac exsanguination. At days 2, 5, 8, 12, and 14 p.i., three plg−/− and three plg+/+ animals were sacrificed similarly. All mice had been randomly selected for day of sacrifice prior to the experiment. Organs were immediately perfused in situ with PBS through the left heart ventricle until the kidneys were macroscopically free of blood. Tissue samples of heart, brain, and kidneys were fixed with 4% phosphate-buffered formalin, paraffin embedded, sectioned to a 5-μm thickness, stained with hematoxylin-eosin, and analyzed for histopathological changes. Samples of kidney and brain were embedded in OCT compound medium (Tissue Tek; Miles Inc. Diagnostics Division, Elkhart, Ind.) for frozen tissue specimens, snap-frozen in isopentane prechilled with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C until sectioned.

Immunohistochemistry.

Frozen tissues were sectioned to 8 μm using a cryostat (HM505E; Microm, Laborgeräte, GbH, Walldorf, Germany) and fixed in 50% acetone for 30 s and 100% acetone at 4°C for 3 min. The sections were kept at −80°C until use. For staining of immune cells in kidney and brain tissue sections, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation in 3% H2O2 for 10 min. To block unspecific binding, the sections were incubated for 30 min with normal rabbit serum (1:5; GIBCO BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.) followed by avidin and biotin (blocking kit; Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, Calif.) for 30 min, respectively. Sections were incubated with rat monoclonal antibody to mouse CD45 (YW62.3; Harlan Sera-Lab Ltd., Loughborough, England) overnight at 4°C, followed by incubation with biotinylated rabbit anti-rat antibodies (DAKO Corporation, Carpinteria, Calif.) for 1 h. StreptABComplex-horseradish peroxidase (DAKO) was used according to the manufacturer's recommendations for amplification of signals and developed using 3,3-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) chromogen tablets (DAKO). Mayer's hematoxylin (Apoteksbolaget, Malmö, Sweden) was used as a counterstain.

For staining of spirochetes, thawed sections were blocked with 5% normal goat serum for 45 min, followed by incubation overnight at 4°C with the Borrelia-specific mouse antiflagellin monoclonal antibody H9724 and subsequently with the secondary antibody Cy3-conjugated F(ab′)2 anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (heavy plus light chain) (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories Inc., West Grove, Pa.) for 1 h in the dark. DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Molecular Probes) or fluorescein wheat germ agglutinin (Vector) was used as a counterstain. A monoclonal fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated rat anti-mouse CD31/PECAM-1 antibody (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc, Birmingham, Ala.) was used for double staining of endothelium. A nonfading mounting medium (Vectashield; Vector) was used, and sections were analyzed using a fluorescence microscope. For all immunostaining, specificity was shown by lack of staining following replacement of monoclonal antibodies with PBS.

Quantitative analysis of spirochetes and immune cells in kidney tissue.

The quantitation of bacteria and immune cells in sequential sections of kidney and brain tissue was performed essentially as described by Hooke et al. (25). Briefly, the number of cells in kidney interstitium and glomeruli, as well as cerebrum and cerebellum, was determined by immunostaining, and values were reported per square millimeter of respective tissue area using an ocular inserted square pattern (01B21210; Graticules Pyser-SGI Ltd., Edenbridge, United Kingdom). Tissue close to the edge of sections was excluded from calculation. A total area of approximately 3.75 mm2 was evaluated per mouse for quantitation of interstitial leukocytes and a glomerular area of about 0.1 mm2 (15 glomeruli) was evaluated for cells located within glomeruli. Approximately 50 mm2 per mouse was evaluated for the presence of spirochetes. The total area evaluated for immune cells included sections taken at two depths of the organs; the area evaluated for spirochetes included three depths. The analyses were performed in a blinded fashion, i.e., the observer did not know the origin of the microscopic sections.

Statistical analysis.

For spirochetemia, the design of the experiment does not allow a statistical test involving a test statistic with an asymptotic distribution, because of the small samples at each time point. Thus, a test of homogeneity between plg−/− and plg+/+ mice was made with the Fisher exact test, with the variable transformed to an indicator variable with value 0 for bacteria in blood and 1 for no bacteria in blood. For analyses of spirochetes and CD45+ cells in tissues, the Mann-Whitney test was used. Comparisons of proportions of mice with clinical and histopathological symptoms (Table 1) were performed according to a normal approximation of binomial distribution (17). The criterion for significant differences throughout the material was that the probability for random occurrence was less than 0.05.

TABLE 1.

Number of mice with histopathological and clinical symptoms indicative of spirochete invasion after infection with B. crocidurae

| Infection group | No. of mice with symptoms of invasion

|

Total no. of mice with signs of invasion | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Histopathological

|

Clinical (brain)a | ||||

| Kidney | Heart | Brain | |||

| plg+/+ | 2 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 8/15b |

| plg−/− | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3/15 |

Neurological symptoms were defined as the inability to coordinate movements when lifted by the tail and/or swimming inability.

P < 0.05 compared to proportion of plg−/− mice.

RESULTS

Dose-dependent coating of B. crocidurae with plasmin.

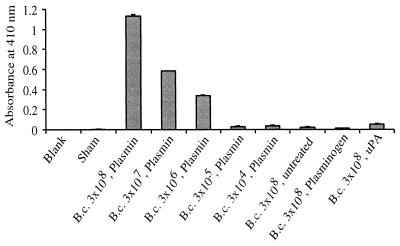

Addition of Plg to in vitro-cultivated B. crocidurae resulted in dose-dependent coating of the protein to the surface of the spirochetes. Bound Plg was activated by uPA, whereupon surface-associated plasmin activity was observed as proteolysis of a plasmin chromogenic substrate (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Dose-dependent coating of B. crocidurae (B.c.) by plasmin. Different concentrations of B. crocidurae were incubated with Plg and uPA, forming active plasmin on the surface of the spirochetes. Some of the borrelial preparations received only Plg, uPA, or HBSS. The sham control received Plg and uPA but no spirochetes. Data are means plus standard deviations for three replicate samples.

Development of spirochetemia and erythrocyte rosetting during infection.

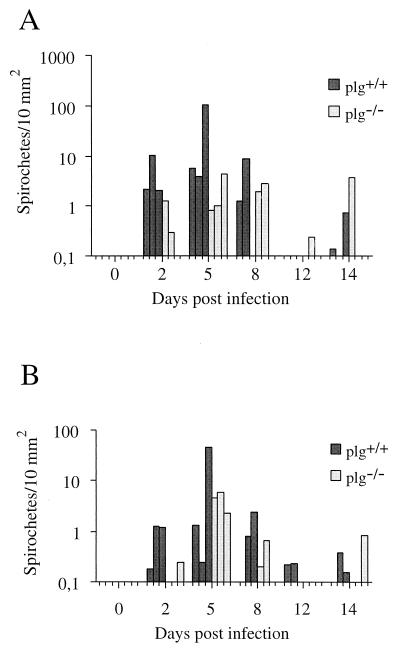

The plg−/− and plg+/+ mice exhibited similar patterns and numbers of spirochetemia (Fig. 2A), and there were no significant differences between the two groups on any day (P > 0.05). A test of the order of infection and no infection was also carried out, showing no significant differences. A somewhat higher percentage of the spirochetes were found in rosettes (i.e., were attached to at least one erythrocyte) in plg−/− mice than in plg+/+ mice, as seen by mean (Fig. 2B) and median (data not shown) values. This indication was most prominent during the first spirochetemic peak, on days 3 to 7 p.i. Attachment of spirochetes to more than two erythrocytes occurred to the same degree in the two mouse groups (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

(A) Mean course of spirochetemia of plg−/− and plg+/+ mice during infection with B. crocidurae. (B) Mean percentage of spirochetes associated with erythrocyte rosettes during the infection process. Error bars for each point were omitted for clarity.

Development of neurological symptoms.

Of the inoculated mice, three plg+/+ mice and one plg−/− mouse developed neurological symptoms. The plg+/+ mice failed both the coordination and swim tests, whereas the plg−/− mouse failed only the swim test (Table 1). In all cases, the neurological symptoms appeared on day 8 p.i. The symptoms persisted until the day of sacrifice, i.e., day 12 p.i. for two of the plg+/+ mice. The other two symptomatic mice were sacrificed on the day of the appearance of symptoms, day 8 p.i., due to the method of random selection for day of sacrifice which was used. The spirochetemias did not differ between mice with or without neurological symptoms, as seen by comparison of both mean and median values.

Quantitative analysis of spirochetes and inflammation.

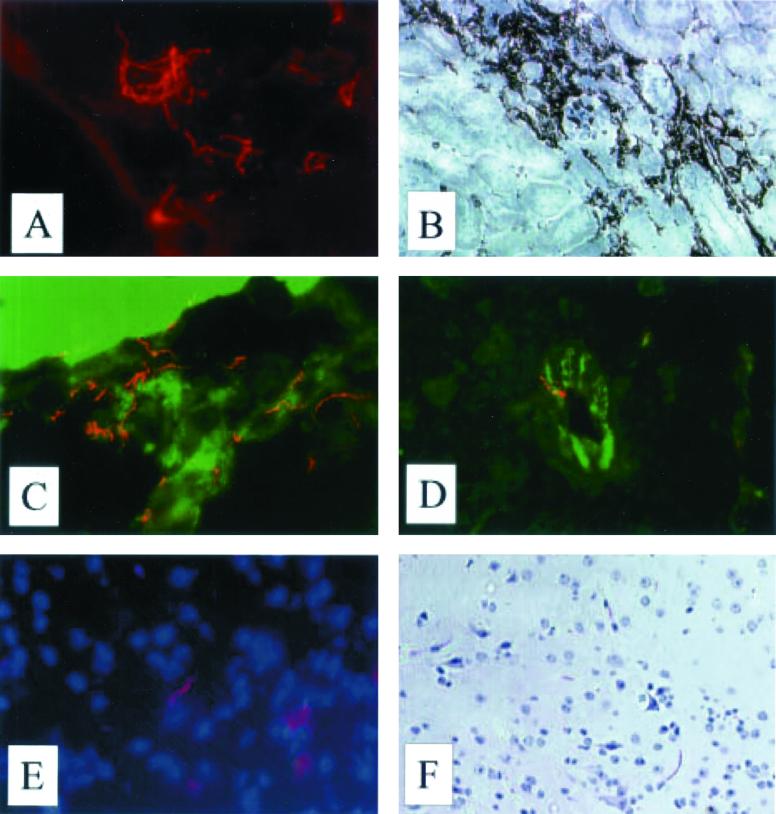

Representative staining of spirochetes in kidney, brain, and CD45+ cells, histopathology, and endothelial staining are illustrated in Fig. 3. The localization of spirochetes in the organs was similar to earlier findings (38). The overall pattern of detected extravascular spirochetes in kidney tissue paralleled the pattern of spirochete fluctuation observed in blood, with the highest number of spirochetes detected at day 5 p.i. also in the tissue, and with the next peak at day 14 p.i. (Fig. 4A). The corresponding pattern was indicated to also occur in brain (Fig. 4B). The spirochetes were most often demonstrated in the proximity of blood vessels on days 2 and 5 p.i., whereas they were detected further away and more homogeneously across the sections at later stages. Among plg−/− mice, the number of spirochetes detected in interstitium increased with time and at day 8 p.i. approached those observed on day 2 p.i. in plg+/+ mice. The difference in spirochete numbers in kidney interstitium was significant early, i.e., days 2 to 5 p.i. (P = 0.02), and stayed significant throughout the first spirochetemic peak, i.e., days 2 to 8 p.i. (P = 0.04).

FIG. 3.

Micrographs of kidney and brain tissue from plg+/+ mice. (A) Immunofluorescence staining showing B. crocidurae spirochetes in kidney interstitium, day 12 p.i. (B) Immunoperoxidase staining of CD45+ cells in kidney, day 2 p.i. (C) Spirochetes in plexus choroideus, day 5 p.i. (D) Spirochete associated with vessel wall in cerebrum. The sample was double stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated antibody to endothelium (CD31/PECAM-1). (E) Spirochete in the brain parenchyma. Counterstaining with DAPI shows nuclei. (F) Activated microglia.

FIG. 4.

Numbers of spirochetes in kidney interstitium (A) and cerebrum (B) of B. crocidurae-infected plg−/− and plg+/+ mice, as demonstrated by immunohistochemistry. Analyses included five mice of each category sacrificed on day 0 and three of each category for days 2, 5, 8, 12, and 14 p.i.

In brain, a more efficient invasion was indicated in plg+/+ mice day 2 p.i. than in plg−/− mice. Similar numbers of spirochetes were demonstrated in the mouse groups on day 5 p.i., with a tendency toward higher numbers on days 8 and 12 in plg+/+ mice. Spirochetes in the process of extravasating were frequently detected (data not shown). Double staining of spirochetes and PECAM-1, an endothelial marker, was performed to confirm the extravascular location of spirochetes. The numbers of spirochetes associated with endothelium were the same for plg+/+ and plg−/− mice. On day 2 p.i., an average of 71% of all spirochetes detected in brains of plg+/+ mice were located extravascularly, compared to 25% in plg−/− mice.

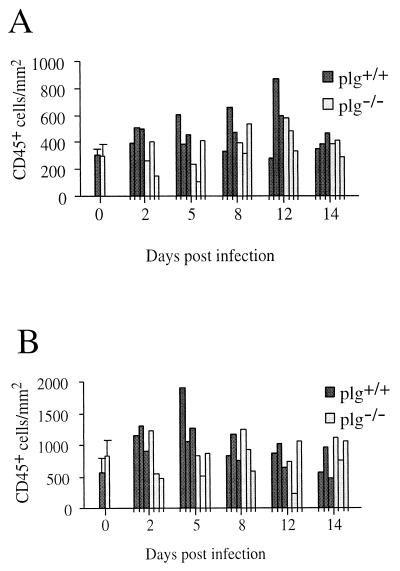

The numbers of CD45+ cells were higher in both kidney interstitium and glomeruli of plg+/+ mice than of plg−/− mice (Fig. 5). There was a significant inflammatory response in glomeruli of plg+/+ mice during the entire process (P = 0.02, days 2 to 14 p.i.), most pronounced on days 2 to 5 (P = 0.01), but not in plg−/− mice (P > 0.05). The difference in inflammation was significant early, i.e., days 2 to 5 p.i. (P = 0.02). Similarly, in interstitium, more CD45+ cells were present in plg+/+ mice than in plg−/− mice (P = 0.03, days 2 to 14 p.i.). The difference was established early, i.e., days 2 to 5 p.i. (P = 0.03). No significant inflammation was detected in interstitium of plg−/− mice (P > 0.05), although a slight increase was indicated on days 8 to 12 p.i.

FIG. 5.

Numbers of leukocytes in kidney interstitium (A) and glomeruli (B) after infection of plg−/− and plg+/+ mice with B. crocidurae, as demonstrated by immunohistochemical detection of the CD45 antigen. Day 0 values are means for five mice from each group; others are values for individual mice, with three plg−/− and plg+/+ mice represented at each time point.

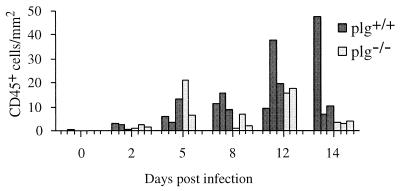

In brain, inflammation was more severe in plg+/+ than plg−/− mice (P = 0.047) (Fig. 6). From day 2 p.i., numbers of leukocytes increased, and throughout the infection process, a decline was indicated only in plg−/− mice on day 14 p.i. In contrast, regression analysis showed an increase in CD45+ cells over time, from day 2 to 14 p.i., in the brains of plg+/+ mice (P = 0.001).

FIG. 6.

Numbers of leukocytes in cerebrum after infection of plg−/− and plg+/+ mice with B. crocidurae, as demonstrated by immunohistochemical detection of the CD45 antigen. Day 0 values are means for five mice from each group; others are values for individual mice, with three plg−/− and plg+/+ mice represented at each time point.

Histopathology.

Histopathological changes were detected in two plg−/− mice and eight plg+/+ mice (Fig. 3F). Changes in plg−/− mice were observed in kidney and central nervous system samples. Changes in plg+/+ mice also included heart and were more common in all three organs (Table 1). Clinical signs of central nervous system involvement were detected in one additional plg−/− mouse (one total) and one additional plg+/+ mouse (three total). Thus, signs of brain invasion, as indicated by histopathological and/or clinical symptoms, were more commonly found among plg+/+ mice (7 of 15) than plg−/− mice (2 of 15) (P < 0,05). Whereas the symptoms in plg+/+ mice were detected on all days of sacrifice from day 8 p.i. onward, except for a heart symptom on day 2 p.i., any symptoms in plg−/− mice were seen on day 8 p.i. and were absent on the later days of sacrifice. A larger proportion of mice with histopathological and/or clinical symptoms of organ invasion was found in the plg+/+ mouse group than in the plg−/− group (P = 0.03).

The histopathological observations in brains of plg+/+ mice were meningeal leukocytosis and leukocytosis in meningeal vessels on day 8 p.i. and, at the later stages, inflammation showing granulocytes, monocytes, macrophages, and lymphocytes, suggestive of subacute meningitis. The plg−/− mouse with histopathological changes in the brain showed focal cell infiltrates of mononuclear leukocytes in a single site in meninges.

Histopathological symptoms observed in kidneys in plg+/+ mice included capillary thrombi in medullary rays as well as a perivascular infiltrate showing mononuclear leukocytes, with several protein casts in tubuli of the inner cortex. In the plg−/− mouse, the symptoms were leukocyte infiltration of perirenal fat tissues.

Symptoms in hearts were acute focal myocardial degeneration and interstitial myocarditis on day 8 p.i. and chronic myocardial degeneration on days 2 and 14 p.i.

DISCUSSION

Binding of Plg to the surface of bacteria has been proposed to be of importance for the invasion capacity of a number of pathogenic bacterial species belonging to several genera, including Borrelia (13, 16, 22). So far, in vivo studies of the role of Plg binding in pathogenicity have been performed for few organisms. Two such studies have been performed for Borrelia species, i.e., the Lyme disease species B. burgdorferi and a hitherto-uncharacterized Spanish RF isolate, and have indicated a role for Plg binding at different stages of the pathogenic process for the two species (15, 23). Whereas Plg binding appeared to be important for tissue invasion but not for the capacity to cause spirochetemia for the RF species, the opposite was indicated for the Lyme disease species. A major hindrance to evaluating invasion has been the requirement to use PCR for detection, due to the low numbers of spirochetes in tissues. Thus, until now, studies of in vivo invasion have required analysis at later stages of the infection process, when the blood is free from spirochetes with contaminating DNA. Thus, it is not clear if differences observed in spirochete load at later stages were due to utilization of Plg in invasion or in spreading through tissue postinvasion. As B. crocidurae invades organs in unusually (for Borrelia) high numbers, quantitative immunohistochemistry could be used to evaluate invasion during the early phase of infection. In addition to brain, which is known to be inflamed after infection of mice with the Spanish RF isolate (1, 21) and B. crocidurae (38), kidney was analyzed for invasion and inflammation, as the organ is consistently inflamed during murine B. crocidurae infection (38).

In this study, we show that Plg is not required for B. crocidurae to cause spirochetemia, as no differences could be observed in spirochetemic patterns between plg+/+ and plg−/− mice. The findings that both the rosette-forming B. crocidurae and a nonrosetting Spanish RF isolate (1, 23) use a Plg-independent mechanism to establish spirochetemia is intriguing, as it indicates that RF species may use a different mechanism(s) than Lyme disease Borrelia to accomplish this step. Tick-borne RF spirochetes are transmitted quickly by species of Ornithodoros that feed for 2 h or less. In contrast, Lyme disease spirochetes generally are not transmitted until after 48 h or more by the slow-feeding species of Ixodes ticks (33). Whether these differences may be attributed to different mechanisms used by the bacteria to spread and/or cross the endothelium from the site of infection or are related to different feeding mechanisms of the tick species remains to be elucidated.

Erythrocyte rosettes have been proposed to be a mechanism for B. crocidurae spirochetes to evade the immune response to the organism (8, 38). Thus, the rosetting may provide a longer period during which the bacteria can reach and invade distant organs as well as be ingested by new ticks. A slightly but not significantly higher rate of rosette formation was observed in plg−/− mice than plg+/+ mice. A possible explanation for this finding may be that plasmin plays a role in the resolution of spirochete-erythrocyte complexes. However, if this is true, the importance of plasmin(ogen) for such a resolution appears to be limited, as no difference was observed between the mouse groups in formation of larger rosettes, i.e., when the criterion was binding to at least two erythrocytes per bacterium.

Despite similar spirochetemias, there was a higher incidence of symptoms of organ invasion in plg+/+ mice than in plg−/− mice.

Spirochetes were also demonstrated in greater numbers in kidney interstitium of plg+/+ than plg−/− mice, where the slowly increasing numbers in plg−/− kidneys on day 8 p.i. were similar to those reached on day 2 p.i. in plg+/+ mice. The interstitial spirochetes were most often demonstrated close to blood vessels during the early phase, days 2 and 5 p.i., of the infection period, whereas they were further away from vessels at later stages, day 8 p.i. and onward. Thus, the spirochetes have the ability to move rather rapidly through the interstitium. A corresponding delayed invasion was also indicated in brains of plg−/− mice. By the method used, spirochetes were detected on day 2 p.i. in brain, which is the earliest demonstration of B. crocidurae in this tissue. The findings of extravascular spirochetes on day 2 p.i. in both kidney and brain, despite the high integrity of the blood-brain barrier, points to a very high efficiency of barrier crossing by B. crocidurae.

All spirochetes detected on day 2 p.i. were unassociated with cells, which indicates that the mechanism of crossing the blood-brain barrier is not accomplished by “hitchhiking” with other cell types. The delayed invasion into both organs of plg−/− mice strongly indicates that Plg aids the bacterium to accomplish this step.

The frequency of spirochete dissemination from the blood to brain was high: 93.3% in plg+/+ and 53.3% in plg−/− mice with brain invasion and 86.7% in plg+/+ and 60% in plg−/− mice with kidney invasion. For brain, the numbers of mice with spirochetes associated with vessels on day 2 p.i. were the same, i.e., two in each group, and no apparent difference between the mouse groups was noted in the numbers of spirochetes associated with vessels at this stage. Despite this fact, a higher percentage of all spirochetes detected in brain were located extravascularly in plg+/+ mice than in plg−/− mice on day 2 p.i. This finding may indicate that the association with, and possibly adhesion to, vessels is the same whether Plg is present or not and that the Plg-related difference is to be found in the actual barrier crossing.

Spirochetes were competent at invading both kidney and brain of plg−/− mice, although seemingly by a less efficient mechanism than in plg+/+ mice. As opposed to the difference observed on day 2 p.i., no differences were seen in numbers of Borrelia organisms in brains of plg+/+ and plg−/− mice on day 5 p.i. In addition, the presence of RF Borrelia in tissues of plg−/− mice on day 28 to 30 p.i. has been reported by Gebbia and colleagues (23). Thus, at least one additional mechanism of invasion other than Plg binding is used by these RF species. Rosette formation may contribute to organ invasion, by a resulting burst of blood vessels, a mechanism that may explain the high invasion efficiency of this organism compared to nonrosetting species. However, as DNA of the Spanish RF isolate was demonstrated in heart and brain tissue of plg−/− mice although it does not form erythrocyte rosettes, rosetting is not the sole explanation for Plg-independent invasion among RF Borrelia (23). Whether the Plg-dependent and Plg-independent invasion mechanisms are mutually exclusive or acting in synergy remains to be elucidated. Borrelia spirochetes have been shown to activate matrix metalloproteinases, and a differential activation pattern was indicated when plasmin was bound to the bacterial surface (22). Thus, the different capabilities of invading organs observed in the present study may in part be related to differential activation of matrix metalloproteinases in the presence or absence of Plg.

A general assessment of inflammation was accomplished by quantification of the number of CD45+ cells in situ in brain as well as kidney glomeruli and interstitium. Both kidney compartments were significantly inflamed in plg+/+ but not in plg−/− mice, although a slight, but not significant, increase in inflammatory cells was indicated over time in interstitium of the latter mice. During the first 5 days of infection, a slight increase in CD45+ cells was seen in brains of plg+/+ and plg−/− mice. On day 8 p.i. and at later stages, the inflammation tended to be more pronounced in plg+/+ than in plg−/− mice, which fits with the more commonly demonstrated occurrence of mice with histopathological and/or clinical symptoms and the indication of a higher total spirochete burden in brains of plg+/+ mice. The inflammation was shown to be more severe in the brains of plg+/+ mice on day 2 to 14 p.i. than in plg−/− mice.

Thus, the Plg-independent mechanism for invading tissues was not sufficient to gain numbers high enough to cause significant inflammation or other investigated symptoms of organ invasion.

Despite the lower degree of invasion which resulted in the plg−/− mice showing less severe symptoms, spirochetes that have invaded with low efficiency may have the capacity to persist in the tissues for an extended length of time, as indicated by the presence of spirochetes in brains and kidneys of plg−/− mice on day 14 p.i. in the present study and by the study by Gebbia and colleagues (23), where spirochetes were present in low numbers in plg−/− mice on days 28 to 30 p.i. after infection with a Spanish RF isolate. Thus, the findings indicate that spirochete invasion in low numbers may lead to absence of invasion sequelae, masking a process during which the asymptomatic individual may acquire Borrelia persistently residing in tissues. The extent to which spirochetes residing in low numbers are associated with low-grade inflammation that does not manifest as clinical symptoms and the extent to which such spirochetes may cause a more significant inflammation at a later stage are unclear at this point.

Whereas inflammation in plg+/+ mice showed a tendency to decrease in glomeruli after the first spirochetemic peak, and possibly in interstitium day 14 p.i., no obvious indication of a decrease was observed in brain, despite decreased detection of spirochetes. In contrast, an increase of CD45+ cells over time was observed in the brains of these mice. Further investigations of the longer perspective of inflammatory changes in the brain, as a result of B. crocidurae infection, should be of great interest for evaluating the long-term effects of spirochete invasion.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council (07922), the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (Infection and Vaccinology), and the Medical and Odontological Faculty of Umeå university.

For statistical consultation, we thank Ingeborg Nordström and Per Arnqvist for evaluating spirochetemia and tissue data, respectively. We are grateful to Tor Ny for providing us with plg−/− and plg+/+ mice and to Tom Schwan for critical reading and discussion of the manuscript.

The first two authors contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anda P, Sánchez-Yebra W, del Mar Vitutia M, Perez Pastrana E, Rodríguez I, Miller N S, Backenson P B, Benach J L. A new Borrelia species isolated from patients with relapsing fever in Spain. Lancet. 1996;348:162–165. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)02332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aubry P, Renambot J, Teyssier J, Buisson Y, Granic G, Brunetti G, Dano P, Bauer P. Borreliosis caused by ticks in Senegal; apropos of 23 cases. Dakar Med. 1983;28:413–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbour A G, Hayes S F. Biology of Borrelia species. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:381–400. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.381-400.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barstad P A, Coligan J E, Raum M G, Barbour A G. Variable major proteins of Borrelia hermsii. Epitope mapping and partial sequence analysis of CNBr peptides. J Exp Med. 1985;161:1302–1314. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.6.1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergeret C, Raoults A. Notes sur les formes nerveuses de la fievre recurrente—fievre recurrente a tiques en Afrique Occidentale Francaise. Bull Med Afr Occidentale Fr. 1948;5:271–279. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bugge T H, Flick M J, Daugherty C C, Degen J L. Plasminogen deficiency causes severe thrombosis but is compatible with development and reproduction. Genes Dev. 1995;9:794–807. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.7.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burman N, Bergström S, Restrepo B I, Barbour A G. The variable antigens Vmp7 and Vmp21 of the relapsing fever bacterium Borrelia hermsii are structurally analogous to the VSG proteins of the African trypanosomes. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1715–1726. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burman N, Shamaei-Tousi A, Bergström S. The spirochete Borrelia crocidurae causes erythrocyte rosetting during relapsing fever. Infect Immun. 1998;66:815–819. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.2.815-819.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cadavid D, Barbour A G. Neuroborreliosis during relapsing fever: review of the clinical manifestations, pathology, and treatment of infections in humans and experimental animals. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:151–164. doi: 10.1086/516276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cadavid D, Thomas D D, Crawley R, Barbour A G. Variability of a bacterial surface protein and disease expression in a possible mouse model of systemic Lyme borreliosis. J Exp Med. 1994;179:631–642. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carmeliet P, Achoonjans L, Kieckens L, Ream B, Degen J, Bronson R, De Vos R, van den Oord J J, Collen D, Mulligan R C. Physiological consequences of loss of plasminogen activator gene function in mice. Nature. 1994;368:419–424. doi: 10.1038/368419a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colebunders R, De Serrano P, Van Gompel A, Wynants H, Blot K, Van den Enden E, Van den Enden J. Imported relapsing fever in European tourists. Scand J Infect Dis. 1993;25:533–536. doi: 10.3109/00365549309008539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coleman J L, Benach J L. Use of the plasminogen activation system by microorganisms. J Lab Clin Med. 1999;134:567–576. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2143(99)90095-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman J L, Benach J L. The generation of enzymatically active plasmin on the surface of spirochetes. Methods. 2000;21:133–141. doi: 10.1006/meth.2000.0984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coleman J L, Gebbia J A, Piesman J, Degen J L, Bugge T H, Benach J L. Plasminogen is required for efficient dissemination of B. burgdorferi in ticks and for enhancement of spirochetemia in mice. Cell. 1997;89:1111–1119. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coleman J L, Sellati T J, Testa J E, Kew R R, Furie M B, Benach J L. Borrelia burgdorferi binds plasminogen, resulting in enhanced penetration of endothelial monolayers. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2478–2484. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2478-2484.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colton T. Statistics in medicine. Boston, Mass: Little, Brown and Co.; 1974. Inference on proportions, p 151–188. In T. Colton (ed.) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felsenfeld O. Borrelia, human relapsing fever, and the parasite-vector-host relationships. Bacteriol Rev. 1965;342:1213–1215. doi: 10.1128/br.29.1.46-74.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felsenfeld O. Borrelia: strains, vectors, human and animal borreliosis. St. Louis, Mo: Warren H. Green Inc.; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fischer M B, Roecki C, Paricek P, Schwartz H P, Aguzzi A. Binding of disease-associated prion protein to plasminogen. Nature. 2000;408:479–483. doi: 10.1038/35044100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia-Monco J C, Miller N S, Backenson P B, Anda P, Benach J L. A mouse model of Borrelia meningitis after intradermal injection. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:1243–1245. doi: 10.1086/593681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gebbia J A, Coleman J L, Benach J L. Borrelia spirochetes upregulate release and activation of matrix metalloproteinase gelatinase B (MMP-9) and collagenase 1 (MMP-1) in human cells. Infect Immun. 2001;69:456–462. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.456-462.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gebbia J A, Monco J C, Degen J L, Bugge T H, Benach J L. The plasminogen activation system enhances brain and heart invasion in murine relapsing fever borreliosis. J Clin Investig. 1999;103:81–87. doi: 10.1172/JCI5171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goubau P F. Relapsing fevers. A review. Ann Soc Belge Med Trop. 1984;64:335–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hooke D H, Gee D C, Atkins R C. Leukocyte analysis using monoclonal antibodies in human glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int. 1987;31:964–972. doi: 10.1038/ki.1987.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klempner M S, Noring R, Epstein M P, McCloud B, Rogers R A. Binding of human urokinase type plasminogen activator and plasminogen to Borrelia species. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:97–104. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levaditi C, Anderson T. Neurotropisme du Spirochaeta duttoni. C R Acad Sci. 1928;186:653–654. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mooser H. Die Rückfallfeber. Ergeb Mikrobiol. 1958;31:184–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nordstrand A, Barbour A G, Bergström S. Borrelia pathogenesis research in the post-genomic and post-vaccine era. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3:86–92. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(99)00056-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ny A, Leonardsson G, Hägglund A-C, Hägglöf P, Ploplis V A, Carmeliet P, Ny T. Ovulation in plasminogen-deficient mice. Endocrinology. 1999;140:5030–5035. doi: 10.1210/endo.140.11.7113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olchovsky D, Pines A, Sadeh M, Kaplinsky N, Frankl O. Multifocal neuropathy and vocal cord paralysis in relapsing fever. Eur Neurol. 1982;21:340–342. doi: 10.1159/000115501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Radolf J D, Arndt L L, Akins D R, Curetty L L, Levi M E, Shen Y, Davis L S, Norgard M V. Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins and synthetic lipopeptides activate monocytes/macrophages. J Immunol. 1995;154:2866–2877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schwan T. Ticks and Borrelia: model systems for investigating pathogen-arthropod interactions. Infect Agents Dis. 1996;5:167–181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scott R. Neurological complications of relapsing fever. Lancet. 1944;247:436–438. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sellati T J, Burns M J, Ficazzola M A, Furie M B. Borrelia burgdorferi upregulates expression of adhesion molecules on endothelial cells and promotes transendothelial migration of neutrophils in vitro. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4439–4447. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4439-4447.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shamaei-Tousi A, Burns M J, Benach J L, Furie M B, Gergel E I, Bergström S. The relapsing fever spirochete, Borrelia crocidurae, activates human endothelial cells and promotes the transendothelial migration of neutrophils. Cell Microbiol. 2000;2:591–599. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shamaei-Tousi A, Collin O, Bergh A, Bergström S. Testicular damage by microcirculatory disruption and colonization of an immune privileged site during Borrelia crocidurae infection. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1–11. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.9.995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shamaei-Tousi A, Martin P, Bergh A, Burman N, Brännström T, Bergström S. Erythrocyte-aggregating relapsing fever spirochete Borrelia crocidurae induces formation of microemboli. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:1929–1938. doi: 10.1086/315118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Simpson S. Ataxia, head tilt, nystagmus, circling, and hemiparesis, p 257. In: Ford R B, editor. Clinical signs and diagnosis in small animal practice. New York, N.Y: Churchill Livingstone; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Southern P, Sanford J. Relapsing fever: a clinical and microbiological review. Medicine. 1969;48:129–149. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stoenner H G, Dodd T, Larsen C. Antigenic variation of Borrelia hermsii. J Exp Med. 1982;156:1297–1311. doi: 10.1084/jem.156.5.1297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taft W, Pike J. Relapsing fever. Report of a sporadic outbreak including treatment with penicillin. JAMA. 1945;129:1002–1005. doi: 10.1001/jama.1945.02860490014004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Trape J F, Duplantier J M, Bouganali H, Godeluck B, Legros F, Cornet J P, Camicas J L. Tick-borne borreliosis in West Africa. Lancet. 1991;337:473–475. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93404-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trape J F, Godeluck B, Diatta G, Rogier C, Legros F, Albergel J, Pepin Y, Duplantier J M. The spread of tick-borne borreliosis in West Africa and its relationship to sub-Saharan drought. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:289–293. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vidal V, Scragg I G, Cutler S J, Rockett K A, Fekade D, Warrell D A, Wright D J, Kwiatkowski D. Variable major lipoprotein is a principal TNF-inducing factor of louse-borne relapsing fever. Nat Med. 1998;4:1416–1420. doi: 10.1038/4007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]