PURPOSE

Many hospitals have established goals-of-care programs in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic; however, few have reported their outcomes. We examined the impact of a multicomponent interdisciplinary goals-of-care program on intensive care unit (ICU) mortality and hospital outcomes for medical inpatients with cancer.

METHODS

This single-center study with a quasi-experimental design included consecutive adult patients with cancer admitted to medical units at the MD Anderson Cancer Center, TX, during the 8-month preimplementation (May 1, 2019-December 31, 2019) and postimplementation period (May 1, 2020-December 31, 2020). The primary outcome was ICU mortality. Secondary outcomes included ICU length of stay, hospital mortality, and proportion/timing of care plan documentation. Propensity score weighting was used to adjust for differences in potential covariates, including age, sex, cancer diagnosis, race/ethnicity, and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score.

RESULTS

This study involved 12,941 hospitalized patients with cancer (pre n = 6,977; post n = 5,964) including 1,365 ICU admissions (pre n = 727; post n = 638). After multicomponent goals-of-care program initiation, we observed a significant reduction in ICU mortality (28.2% v 21.9%; change −6.3%, 95% CI, −9.6 to −3.1; P = .0001). We also observed significant decreases in length of ICU stay (mean change −1.4 days, 95% CI, −2.0 to −0.7; P < .0001) and in-hospital mortality (7% v 6.1%, mean change −0.9%, 95% CI, −1.5 to −0.3; P = .004). The proportion of hospitalized patients with an in-hospital do-not-resuscitate order increased significantly from 14.7% to 19.6% after implementation (odds ratio, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.3 to 1.5; P < .0001), and do-not-resuscitate order was established earlier (mean difference −3.0 days, 95% CI, −3.9 to −2.1; P < .0001).

CONCLUSION

This study showed improvement in hospital outcomes and care plan documentation after implementation of a system-wide, multicomponent goals-of-care intervention.

INTRODUCTION

Goals-of-care discussions play an important role in supporting shared decision making and promoting goal-concordant care.1 These discussions represent an iterative communication process between patients and their clinicians to enhance the patients' level of illness understanding, to elicit their values and preferences, and to formulate a personalized care plan.2-4 Several longitudinal observational studies suggested that the presence of timely goals-of-care conversations was associated with improved end-of-life care5,6; however, other studies have yielded negative findings and the literature remains mixed.7 Because goals-of-care discussions are complex communication interventions, it remains unclear how best to implement such programs.

CONTEXT

Key Objective

The objective of this study was to examine the impact of a multicomponent interdisciplinary goals-of-care program on intensive care unit (ICU) mortality and other hospital outcomes in medical inpatients with cancer. Although coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has catalyzed the development of goals-of-care programs at many hospitals, to our knowledge, no study has reported the real-world impact of such programs on hospital outcomes.

Knowledge Generated

In this propensity score analysis, we found that the ICU mortality reduced significantly from 28.2% to 21.9% after program implementation. The length of ICU stay and in-hospital mortality also improved significantly, whereas do-not-resuscitate orders were established more frequently and earlier during the hospital course in the postimplementation period.

Relevance (S.B. Wheeler)

-

This study highlights that system-wide implementation of a complex multicomponent interdisciplinary goals-of-care intervention may contribute to improvement in hospital outcomes.*

*Relevance section written by JCO Associate Editor, Stephanie B. Wheeler, PhD, MPH.

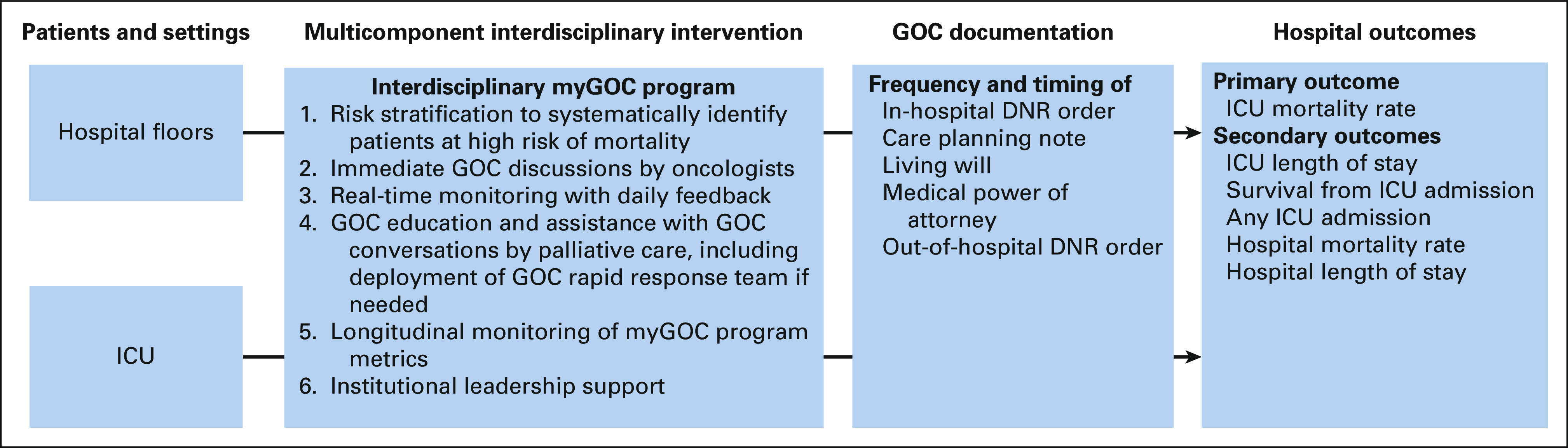

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to a substantial increase in hospitalizations and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions worldwide.8 Patients with cancer are at particularly high risk of COVID-19–related hospitalizations and death.9 The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center is a National Cancer Institute–designated comprehensive cancer center with more than 500 inpatient care beds. In preparation for this unprecedented health crisis with an anticipated sharp rise in demand for ICU beds related to COVID-19 diseases, our hospital leadership implemented a multicomponent interdisciplinary goals-of-care (myGOC) program in March 2020 to optimize ICU and hospital bed utilization, minimize inappropriate intensive interventions at the end of life, and maximize goal-concordant care by increasing goals-of-care discussions (Fig 1).

FIG 1.

myGOC intervention and outcomes. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic with an anticipated increase in the number of patients requiring intensive care, the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center implemented the myGOC program in March 2020 with six main components on the basis of input from multiple disciplines, including medical oncology, surgical oncology, palliative care, hospitalist service, emergency medicine, intensivists, social work, ethics, case management, chaplaincy, and nursing. The aim of this program was to increase GOC discussions, maximize goal-concordant care, optimize ICU and hospital bed utilization, and minimize inappropriate intensive interventions at the end of life. COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; ICU, intensive care unit; myGOC, multicomponent interdisciplinary goals-of-care.

Randomized controlled trials on goals-of-care discussions have traditionally examined narrowly defined communication approaches, which often had only a limited impact on downstream outcomes.10 We believe that multicomponent interdisciplinary approaches could be more impactful; however, these complex interventions are not amenable to investigation with randomized trials. Quality improvement studies examining real-world data could be informative.11 The COVID-19 pandemic has catalyzed the development of goals-of-care programs at many hospitals12-14; however, there is a paucity of literature on actual hospital outcomes associated with these programs. A better understanding of the impact of implementation of goals-of-care programs in the real-world setting may provide valuable insights into how hospitals can improve patient care, resource utilization, and end-of-life care outcomes for hospitalized patients during the pandemic and beyond. In this study, we examined the impact of the myGOC program on ICU mortality among hospitalized medical patients with cancer. We hypothesize that ICU mortality would decrease after implementation of the myGOC program. We also assessed the program's impact on other ICU and hospitalization outcomes.

METHODS

Study Design

This retrospective study used a quasi-experimental design to assess the impact of our myGOC program on patient outcomes. The myGOC program was launched institution-wide in March 2020 with optimization of processes over the next 2 months. We examined the outcomes over an 8-month postimplementation period (May 1, 2020-December 31, 2020) and compared these outcomes with the same time period 1 year before (May 1, 2019-December 31, 2019). The Institutional Review Board at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center approved this study and provided waiver for informed consent. This study focuses on examining the impact of the myGOC program on hospitalization outcomes.

Eligibility Criteria

Consecutive adult patients (age ≥ 18 years) who were admitted to the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, TX, were eligible for this study if they were under the care of a medical team during either the preimplementation (May 1, 2019-December 31, 2019) or postimplementation (May 1, 2020-December 31, 2020) time frame. Many surgeries were canceled during the COVID-19 pandemic; we excluded surgical ICU patients because their outcomes were not comparable across the two time periods.

Care for Patients With Active SARS-COV-2 Infections

During the COVID-19 pandemic, our institution created a COVID-19 unit specifically for any inpatients with active severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) infections. Life-sustaining measures including mechanical ventilation were provided in this unit if needed, and patients remained there until they were deemed no longer infectious or died. These patients were included in the primary analysis and excluded in the sensitivity analysis. Patients without active SARS-CoV-2 infections who required critical care were transferred to the 52-bed ICU same as before the pandemic.

myGOC Program

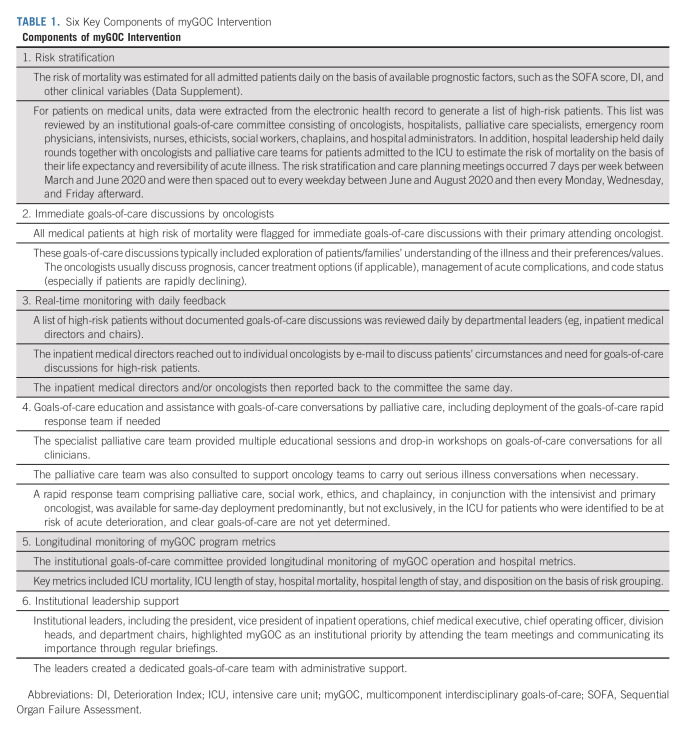

The myGOC program was developed rapidly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. Senior leadership at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center was acutely aware of the potential surge that the COVID-19 disease held for health care systems and tasked a workgroup including inpatient physician leaders, case managers, and a clinical ethicist to lead and develop a plan to maximize goals-of-care conversations with patients and families. The main goal of this program was to reduce inappropriate ICU utilization. A stakeholder group was formed in March 2020 to discuss various approaches. This interdisciplinary group consisted of approximately 20 members, including representatives from medical oncology, surgical oncology, palliative care, hospitalist service, emergency medicine, intensivists, social work, ethics, case management, chaplaincy, and nursing. Each stakeholder reviewed the literature on prognostication and best practices to support goals of care in their respective fields. Between March and April 2020, daily meetings were held with active discussions among stakeholders to formulate and optimize different components of the multicomponent program with rapid implementation under the direction of institutional leadership. The myGOC program consisted of six components (Table 1, Fig 1, and Data Supplement, online only) with concurrent rollout to all medical units and the ICU.

TABLE 1.

Six Key Components of myGOC Intervention

Data Collection

Data were retrieved by the informatics team via the electronic health record, supplemented by chart review where necessary. We retrieved patient demographics on admission, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, and cancer diagnosis. Data on hospital admission included primary admitting service, admission type, COVID-19 disease, and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score15,16 and Deterioration Index17 (Data Supplement).

The primary outcome was ICU mortality, defined as the number of patients who died in the ICU divided by the number of total ICU discharges. ICU mortality was selected because it is one of the quality of end-of-life care measures identified by the National Quality Forum and because of its role as a standardized metric of ICU utilization.18 For this outcome, patients with multiple ICU admissions during the same hospital stay were only counted once by examining mortality status at the last ICU discharge during that hospitalization. Secondary outcomes included ICU length of stay, need for ICU admission during the same hospital visit, hospital mortality, and hospital length of stay.

The processes of myGOC were assessed by examining both the proportion and timing of completion of key documents relative to the index hospital admission, including the goals-of-care discussions using a note template, do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders, living will, medical power of attorney, and out-of-hospital DNR (OOHDNR) orders.

Statistical Analysis

Preliminary estimates indicated that there were approximately 600 medical ICU patients over both time periods. Assuming a baseline ICU mortality of 28%, we had an 80% power to detect a 5% reduction in mortality using a two-tailed test at the 5% significance level.

Descriptive statistics such as proportions, 95% CIs, means, standard deviations (SDs), medians, and interquartile ranges were used to summarize patient characteristics and outcomes.

There were 13,312 and 10,796 hospitalizations for medical patients in the 2019 and 2020 study periods, respectively. To keep observations independent, we randomly selected a single hospitalization incident for patients with repeated admissions within each cohort period (n = 2,802 in 2019; n = 2,264 in 2020). Each visit had an equal probability of being chosen for inclusion in the study, and only ICU visits associated with those stays were included in the analysis of ICU data. Because there was a minimal overlap in the patient population between the two cohort periods (< 1%), we compared the hospital outcomes between 2019 and 2020 using two-tailed t tests, Wilcoxon rank-sums tests, and log-rank tests for continuous variables and logistic regression for binary outcomes.

To account for differences in patient characteristics between the two time periods, we used propensity score weighting to adjust for differences in potential covariates, including age, sex, cancer diagnosis, race/ethnicity, and SOFA score. A logistic regression model was constructed in which the dependent variable was the probability of being assigned to study intervention (myGOC) and the independent variables were patient age, sex, cancer type (solid, hematologic, others, and unknown), race/ethnicity, SOFA score at hospital admission, and ICU admission during hospital stay. Inverse proportion weights using the average treatment effect on the entire sample were calculated and used to adjust the data when summarizing and conducting hypotheses tests. Propensity scores were also evaluated for adequacy by examining the standardized difference between cohorts and percent reduction of standardized differences. Although the propensity score distribution was well balanced between the two cohorts as assessed using overlaid histograms, we excluded from our analysis patients whose propensity scores were extreme outliers because of the potential influence that they could have on the statistical model. In total, 125 (3.2%) medical patients, including 48 ICU patients, had propensity scores either 1.5 times higher than the upper quartile or 1.5 times lower than the lower quartile and were excluded. Furthermore, six patients were omitted from the analyses as their propensity scores were not calculable because of missing data. All standardized differences after applying inverse proportion weights were < 0.1 in magnitude. The same set of propensity scores were used for all cohorts examined for the study.

To assess the impact of COVID-19 diseases on the results, a second set of analyses were completed excluding patients with active SARS-COV-2 infection during the index admission.

The Statistical Analysis System (SAS version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R statistical software (R version 4.2.2; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) were used for statistical analysis. Summary statistics and hypothesis testing were adjusted by inverse-weighted propensity scores using the weight option in SAS procedures and the R survey package (version 4.1-1). A P value of .05 or less was considered to be statistically significant for the primary outcome. To account for multiple testing, a P value of .005 or less was considered to be statistically significant for secondary outcomes after adjustment with Bonferroni correction.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

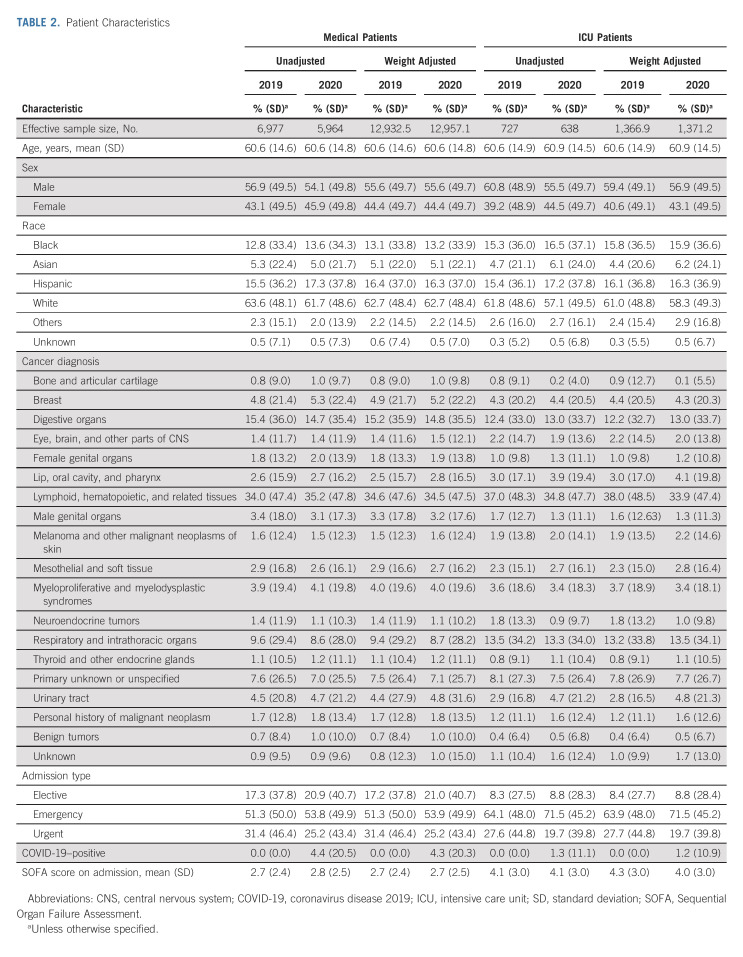

This study included 12,941 medical patients over the 16-month study period, with 6,977 patients in the preintervention period and 5,964 patients in the postintervention period (Table 2). The mean age was 60.6 years (SD 14.7); 5,747 (44.4%) were female, 8,116 (62.7%) were White, and 4,987 (38.5%) had hematologic malignancies. A total of 261 (4.4%) patients had an active diagnosis of COVID-19 disease in the 2020 cohort. The mean SOFA score on hospital admission was 2.7 (SD 2.4).

TABLE 2.

Patient Characteristics

A total of 727 (10.4%) patients in 2019 and 638 (10.7%) patients in 2020 were admitted to the ICU. The mean SOFA score on hospital admission was 4.1 (SD 3.0) for these ICU patients.

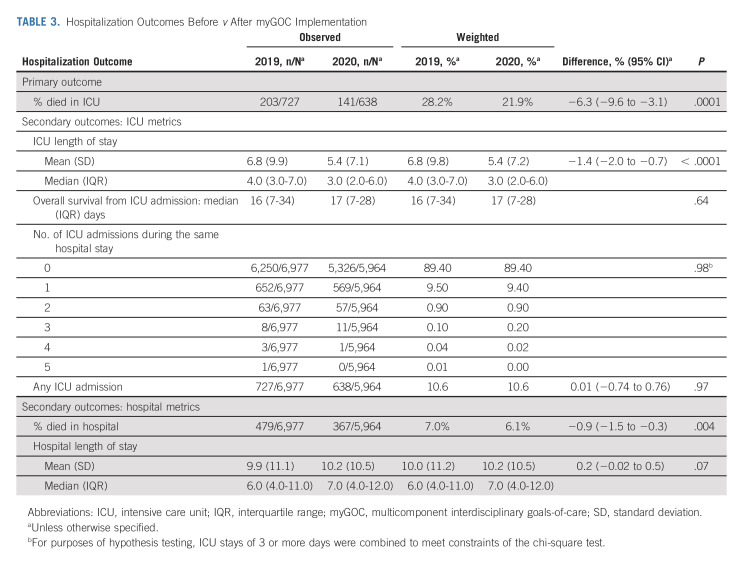

ICU Outcomes

Compared with 2019, we observed a significant reduction of ICU mortality in 2020 (28.2% v 21.9%; change −6.3%, 95% CI, −9.6 to −3.1; P = .0001; Table 3). The length of ICU stay was also significantly shorter (median, 4 v 3 days; mean change −1.4 days, 95% CI, −2.0 to −0.7; P < .0001). There was no significant difference in the number of patients requiring ICU admission, the number of patients with ICU readmission during the index hospitalization, or overall survival from ICU admission.

TABLE 3.

Hospitalization Outcomes Before v After myGOC Implementation

Hospital Outcomes

Among all medical patients, the in-hospital mortality reduced significantly from 7% in 2019 to 6.1% in 2020 (mean change −0.9%, 95% CI, −1.5 to −0.3; P = .004). There was no significant difference in the length of hospitalization.

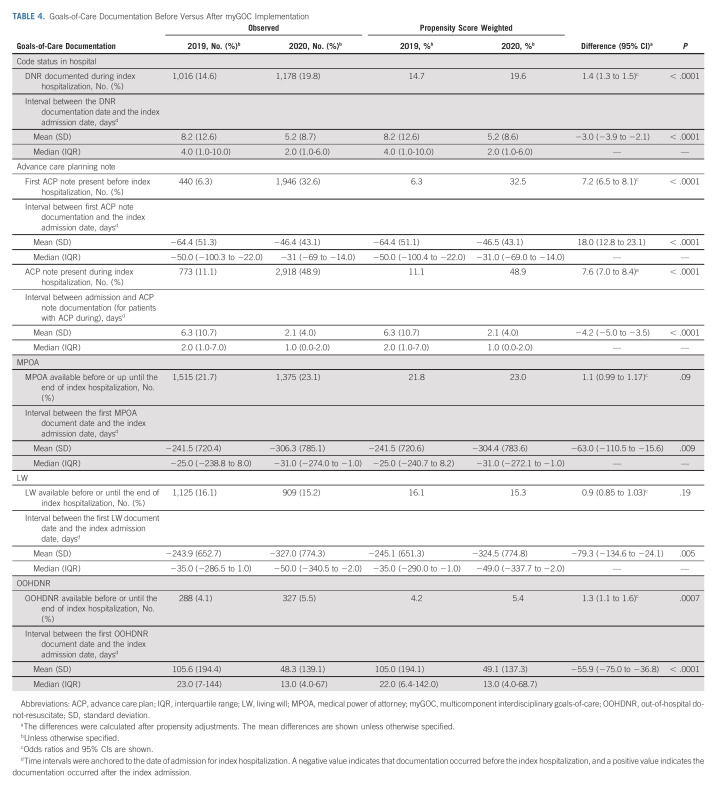

Goals-of-Care Documentation

Table 4 shows the proportion of hospitalized patients with an in-hospital DNR order increased significantly from 14.7% to 19.6% after program implementation (odds ratio [OR], 1.4; 95% CI, 1.3 to 1.5; P < .0001), and they were established earlier (mean −3.0 days, 95% CI, −3.9 to −2.1). There was a significant increase between 2019 and 2020 in the proportion of patients with documentation of goals-of-care discussions before (6% v 33%; OR, 7.2; 95% CI, 6.5 to 8.1; P < .0001) and during the index admission (11% v 49%; OR, 7.6; 95% CI, 7.0 to 8.4; P < .0001). In addition, the timing of completion of these documents occurred earlier relative to the indexed admission. Similarly, OOHDNR was documented in a greater proportion of patients, and living will, medical power of attorney, and OOHDNR were documented earlier relative to the index hospitalization in 2020 compared with 2019.

TABLE 4.

Goals-of-Care Documentation Before Versus After myGOC Implementation

Sensitivity Analysis

To account for different disease trajectories among patients admitted with SARS-COV-2 infections, we repeated the analyses but excluded 261 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 positivity in 2020. The outcomes were consistent with the main findings reported above (Data Supplement).

DISCUSSION

In this propensity score–adjusted analyses, we found that the multicomponent, interdisciplinary goals-of-care program was associated with a significant reduction in ICU mortality, ICU length of stay, and in-hospital mortality and increased goals-of-care documentation. These outcomes are consistent with our main program goal of optimizing ICU utilization in response to an anticipated need for more ICU beds during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study highlights the potential impact of a system-wide goals-of-care program to improve patient and hospital outcomes.

Several important ICU metrics improved significantly in the postintervention period. We believe that the findings are robust because of the large sample size with consecutive patients, rapid change in these outcomes in relation to program implementation, propensity score adjustments, and sensitivity analysis. In addition to proactively identifying patients at high risk of mortality and thus less likely to benefit from intensive measures such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, and continuous dialysis, the myGOC program reinforced goals-of-care discussions with close follow-up, which likely contributed to the improved outcomes.

The literature on outcomes of goals-of-care interventions has been mixed. Existing randomized clinical trials are often limited to structured interventions with a narrower focus, which may explain why many were not able to demonstrate substantial changes in system outcomes.10,19-21 A systematic review included seven randomized trials, and 3,477 patients at high risk of mortality reported that protocolized family support interventions significantly reduced ICU length of stay by 0.89 days (95% CI, −1.5 to −0.27); however, ICU mortality rate and hospital mortality rate did not differ.22 In a study of 86 hospitalized patients with advanced cancer, Apostol et al23 reported that patients who reported a goals-of-care discussion had lower rates of ICU admission and hospital mortality. More recently, Chang et al11 reported in a quality improvement study that introduction of a multicomponent ICU family meeting communication intervention was associated with the reduced ICU length of stay from 8.7 to 7.4 days but no change in ICU mortality. By contrast, our study found improvement in both ICU mortality and length of stay while including unselected hospitalized patients with cancer. The actual impact on patients with advanced disease is likely greater.

Because care planning is a highly complex process, multicomponent, interdisciplinary engagement with system-wide involvement is more likely to have an impact than interventions with a more restricted scope.24 Our myGOC program incorporated multiple advances in communication science, interdisciplinary teamwork, and electronic health records. For example, skilled goals-of-care discussions have been found to be associated with decreased aggressiveness of care at the end of life.5 Timely introduction of palliative care has been reported to improve the quality of end-of-life care.25-29 Similarly, spiritual care might play a role in modulating the intensity of care in the last months of life.30 Findings from this study suggest that hospital outcomes may be highly responsive to change when goals of care are a unifying mission of the hospital. Because of the intercalated nature of these interventions and study design, it is not possible to determine the active ingredient. Rather than a single component, we postulate that interdisciplinary teamwork likely contributed to the outcomes. Further research is needed.

The COVID-19 pandemic has catalyzed system-wide implementation in an unprecedented manner to integrate goals-of-care discussions with urgency, attention, and resource.12-14 Our findings might have implications beyond the pandemic given that a majority (95.6%) of our patients did not have COVID-19 disease and sensitivity analysis that excluded the patients with COVID-19 diseases showed similar findings. Longer-term studies are needed to examine the sustainability of this initiative.

This study has several limitations. First, the data were from a single tertiary cancer care center with a unique patient population. Our findings may not be generalizable to other settings. Second, because the myGOC program was created in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, it is not possible to separate the effect of the myGOC program from confounders given our quasi-experimental design. From the mechanistic standpoint, the observed changes were consistent with our predefined program goals, supporting our study hypothesis. Moreover, propensity score adjustments allowed us to adjust for important covariates. However, we could not exclude the possibility that other factors might have contributed to the observed changes. For example, patients might be more interested to be discharged early because of the restrictive visitation policies during the pandemic. The lower patient volume in 2020 might have also allowed clinicians more time to discuss goals of care with patients even if the myGOC program was not in place. Other study designs such as randomized controlled trials and stepped wedged trials may reduce the confounding effect; however, they were not possible given the urgency of the situation and the complexity of the intervention. Longer-term observation of the myGOC program to determine if the outcomes fluctuated with COVID-19 hospitalization rates may be informative. Third, our electronic health record was unable to capture some important data, such as cancer stage and performance status. More research is needed to test our hypothesis that patients with advanced cancer were more likely to be affected by myGOC. Fourth, the study period was relatively short; longer-term studies should be conducted to assess if the myGOC program had a sustained effect on various outcomes. Fifth, this study only focused on key hospital metrics. Other relevant outcomes such as goal-concordant care, quality of life, quality of end-of-life care, and cost of care remain areas for future investigations.

In conclusion, this study highlights the development of our multicomponent, interdisciplinary goals-of-care program, its implementation on an institution-wide scale, and potential impact of key hospital metrics. Our experience supports implementation of hospital-based goals-of-care programs during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank all the patients who were part of this study and all clinicians at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center who contributed to the myGOC program.

Christopher Flowers

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Foresight Diagnostics

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer, Gilead Sciences, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Celgene, Denovo Biopharma, BeiGene, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Pharmacyclics/Janssen, Genentech/Roche, Epizyme, Genmab, Seattle Genetics, Foresight Diagnostics, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Curio Science, AstraZeneca, MorphoSys

Research Funding: Acerta Pharma (Inst), Janssen Oncology (Inst), Gilead Sciences (Inst), Celgene (Inst), TG Therapeutics (Inst), Genentech/Roche (Inst), Pharmacyclics (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Millennium (Inst), Alimera Sciences (Inst), Xencor (Inst), 4D Pharma (Inst), Adaptimmune (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Cellectis (Inst), EMD Serono (Inst), Guardant Health (Inst), Iovance Biotherapeutics (Inst), Kite/Gilead (Inst), MorphoSys (Inst), Nektar (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Sanofi (Inst), Takeda (Inst), ZIOPHARM Oncology (Inst)

David Hui

Research Funding: Helsinn Healthcare (Inst)

Thomas Aloia

Employment: BioIntelliSense

Tito Mendoza

Honoraria: Bristol Myers Squibb, Amgen

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb

Research Funding: Bayer (Inst), Lilly (Inst)

Jennifer McQuade

Honoraria: Merck, Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myer Squibb, Roche Pharma AG

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Merck

Eduardo Bruera

Research Funding: PharmaCann (Inst)

Sairah Ahmed

Honoraria: Seattle Genetics, Novartis

Consulting or Advisory Role: Tessa Therapeutics, Sanofi, Myeloid Therapeutics

Research Funding: Seattle Genetics (Inst), Merck (Inst), Tessa Therapeutics (Inst), Xencor (Inst), Chimagen (Inst)

Marina George

Honoraria: UpToDate

Consulting or Advisory Role: Marvin Health, Daiichi Sankyo

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented as an oral abstract at the 2022 ASCO Annual Meeting (abstract 6502), Chicago, IL, June 4, 2022.

SUPPORT

P.P. was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health Cancer Center Support Grant (P30CA016672). D.H. and E.B. were supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01CA214960, R01CA225701, and R01CA231471). M.D.-G. was supported in part by a National Institutes of Health Grant (R01CA200867).

D.H. and N.N. contributed equally to this work.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: David Hui, Nico Nortje, Marina George, Susannah Kish Wallace, Sajid Haque, Marvin Delgado-Guay, Shalini Dalal, Nisha Rathi, Akhila Reddy, Jennifer McQuade, Peter Pisters, Thomas Aloia, Eduardo Bruera

Financial support: Christopher Flowers

Administrative support: Christopher Flowers, Peter Pisters, Thomas Aloia, Eduardo Bruera

Provision of study materials or patients: Sairah Ahmed, Christopher Flowers

Collection and assembly of data: David Hui, Nico Nortje, Marina George, Kaycee Wilson, Caitlin A. Lenz, Susannah Kish Wallace, Sajid Haque, Eduardo Bruera

Data analysis and interpretation: David Hui, Nico Nortje, Marina George, Diana L. Urbauer, Susannah Kish Wallace, Clark R. Andersen, Tito Mendoza, Sairah Ahmed, Marvin Delgado-Guay, Christopher Flowers, Thomas Aloia, Eduardo Bruera

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Impact of an Interdisciplinary Goals of Care Program Among Medical Inpatients at a Comprehensive Cancer Center During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Propensity Score Analysis

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Christopher Flowers

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Foresight Diagnostics

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bayer, Gilead Sciences, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Celgene, Denovo Biopharma, BeiGene, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Pharmacyclics/Janssen, Genentech/Roche, Epizyme, Genmab, Seattle Genetics, Foresight Diagnostics, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, Curio Science, AstraZeneca, MorphoSys

Research Funding: Acerta Pharma (Inst), Janssen Oncology (Inst), Gilead Sciences (Inst), Celgene (Inst), TG Therapeutics (Inst), Genentech/Roche (Inst), Pharmacyclics (Inst), AbbVie (Inst), Millennium (Inst), Alimera Sciences (Inst), Xencor (Inst), 4D Pharma (Inst), Adaptimmune (Inst), Amgen (Inst), Bayer (Inst), Cellectis (Inst), EMD Serono (Inst), Guardant Health (Inst), Iovance Biotherapeutics (Inst), Kite/Gilead (Inst), MorphoSys (Inst), Nektar (Inst), Novartis (Inst), Pfizer (Inst), Sanofi (Inst), Takeda (Inst), ZIOPHARM Oncology (Inst)

David Hui

Research Funding: Helsinn Healthcare (Inst)

Thomas Aloia

Employment: BioIntelliSense

Tito Mendoza

Honoraria: Bristol Myers Squibb, Amgen

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb

Research Funding: Bayer (Inst), Lilly (Inst)

Jennifer McQuade

Honoraria: Merck, Roche, Bristol Myers Squibb

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myer Squibb, Roche Pharma AG

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: Merck

Eduardo Bruera

Research Funding: PharmaCann (Inst)

Sairah Ahmed

Honoraria: Seattle Genetics, Novartis

Consulting or Advisory Role: Tessa Therapeutics, Sanofi, Myeloid Therapeutics

Research Funding: Seattle Genetics (Inst), Merck (Inst), Tessa Therapeutics (Inst), Xencor (Inst), Chimagen (Inst)

Marina George

Honoraria: UpToDate

Consulting or Advisory Role: Marvin Health, Daiichi Sankyo

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. McNiff KK, Caligiuri MA, Davidson NE, et al. Improving goal concordant care among 10 leading academic U.S. cancer hospitals: A collaboration of the alliance of dedicated cancer centers. Oncologist. 2021;26:533–536. doi: 10.1002/onco.13850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Klement A, Marks S. The pitfalls of utilizing "goals of care" as a clinical buzz phrase: A case study and proposed solution. Palliat Med Rep. 2020;1:216–220. doi: 10.1089/pmr.2020.0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication about serious illness care goals: A review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1994–2003. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hui D, Con A, Christie G, et al. Goals of care and end-of-life decision making for hospitalized patients at a Canadian tertiary care cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38:871–881. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wright AA, Zhang B, Ray A, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussions, patient mental health, medical care near death, and caregiver bereavement adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300:1665–1673. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.14.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mack JW, Cronin A, Keating NL, et al. Associations between end-of-life discussion characteristics and care received near death: A prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4387–4395. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cripe LD, Vater LB, Lilly JA, et al. Goals of care communication and higher-value care for patients with advanced-stage cancer: A systematic review of the evidence. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105:1138–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2021.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wiersinga WJ, Prescott HC. What is COVID-19? JAMA. 2020;324:816. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Siempos II. Effect of cancer on clinical outcomes of patients with COVID-19: A meta-analysis of patient data. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:799–808. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Curtis JR, Downey L, Back AL, et al. Effect of a patient and clinician communication-priming intervention on patient-reported goals-of-care discussions between patients with serious illness and clinicians: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:930–940. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chang DW, Neville TH, Parrish J, et al. Evaluation of time-limited trials among critically ill patients with advanced medical illnesses and reduction of nonbeneficial ICU treatments. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:786–794. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Epstein AS, Riley M, Nelson JE, et al. Goals of care documentation by medical oncologists and oncology patient end-of-life care outcomes. Cancer. 2022;128:3400–3407. doi: 10.1002/cncr.34400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Petriceks AH, Schwartz AW. Goals of care and COVID-19: A GOOD framework for dealing with uncertainty. Palliat Support Care. 2020;18:379–381. doi: 10.1017/S1478951520000474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Thery L, Vaflard P, Vuagnat P, et al. Advanced cancer and COVID-19 comorbidity: Medical oncology-palliative medicine ethics meetings in a comprehensive cancer centre. BMJ Support Palliat Care. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-002946. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-002946 [epub ahead of print on April 29, 2021] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Minne L, Abu-Hanna A, de Jonge E. Evaluation of SOFA-based models for predicting mortality in the ICU: A systematic review. Crit Care. 2008;12:R161. doi: 10.1186/cc7160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ferreira FL, Bota DP, Bross A, et al. Serial evaluation of the SOFA score to predict outcome in critically ill patients. JAMA. 2001;286:1754–1758. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Singh K, Valley TS, Tang S, et al. Evaluating a widely implemented proprietary deterioration index model among hospitalized patients with COVID-19. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2021;18:1129–1137. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202006-698OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Quality Forum . Palliative Care and End-of-Life Care—A Consensus Report. Washington, DC: National Quality Forum; 2012. https://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2012/04/Palliative_Care_and_End-of-Life_Care%E2%80%94A_Consensus_Report.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bernacki R, Paladino J, Neville BA, et al. Effect of the serious illness care program in outpatient oncology: A cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:751–759. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.0077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Paladino J, Koritsanszky L, Neal BJ, et al. Effect of the serious illness care program on health care utilization at the end of life for patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2020;23:1365–1369. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2019.0437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Curtis JR, Back AL, Ford DW, et al. Effect of communication skills training for residents and nurse practitioners on quality of communication with patients with serious illness: A randomized trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2271–2281. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee HW, Park Y, Jang EJ, et al. Intensive care unit length of stay is reduced by protocolized family support intervention: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45:1072–1081. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05681-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Apostol CC, Waldfogel JM, Pfoh ER, et al. Association of goals of care meetings for hospitalized cancer patients at risk for critical care with patient outcomes. Palliat Med. 2015;29:386–390. doi: 10.1177/0269216314560800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Bensink ME, et al. End-of-life care in the intensive care unit: Can we simultaneously increase quality and reduce costs? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:587–592. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201206-1020CP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hui D, Hannon BL, Zimmermann C, et al. Improving patient and caregiver outcomes in oncology: Team-based, timely, and targeted palliative care. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:356–376. doi: 10.3322/caac.21490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hui D, Bruera E. Models of palliative care delivery for patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:852–865. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hui D, Kim SH, Roquemore J, et al. Impact of timing and setting of palliative care referral on quality of end-of-life care in cancer patients. Cancer. 2014;120:1743–1749. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer: Results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2319–2326. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schockett E, Ishola M, Wahrenbrock T, et al. The impact of integrating palliative medicine into COVID-19 critical care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62:153–158.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al. Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: Associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:445–452. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.8005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]