Abstract

The National Occupational Competency Profile (NOCP)-the competency framework for paramedics in Canada-is presently undergoing revision. Since the NOCP was published in 2011, paramedic practice, healthcare, and society have changed dramatically. To inform the revision, we sought to identify emerging concepts in the literature that would inform the development of competencies for paramedics. We conducted a restricted literature review and content analysis of all published and grey literature pertaining to or informing Canadian paramedicine from 2011 to 2022. Three authors performed a title, abstract, and full-text review to identify and label concepts informed by existing findings. A total of 302 articles were categorized into 11 emerging concepts related to competencies: inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility (IDEA) in paramedicine; social responsiveness, justice, equity, and access; anti-racism; healthy professionals; evidence-informed practice and systems; complex adaptive systems; learning environment; virtual care; clinical reasoning; adaptive expertise; and planetary health. This review identified emerging concepts to inform the development of the 2023 National Occupational Standard for Paramedics (NOSP). These concepts will inform data analysis, the development of group discussions, and competency identification.

Keywords: emerging concept, competency framework, competency, emergency medical services, paramedic

Introduction and background

The Paramedic Association of Canada (PAC) published the first National Occupational Competency Profile (NOCP) for paramedics in 2001 [1]. The NOCP has since been used by regulatory bodies, paramedic services, educators, and education accreditation agencies. Recognizing the shifting role of paramedicine in Canada in public safety and healthcare contexts, PAC renewed the NOCP in 2011 [1]. In 2016, additional work commissioned by PAC examined the roles paramedics should embody as part of their work (e.g., clinician, reflective practitioner) [2,3]. Given the central role that the NOCP plays within paramedicine in Canada, the planned 2023 revision must respond to evolving patient and societal needs through the identification of new competencies and the revision or removal of outdated competencies [4]. To this effect, in 2021, PAC partnered with the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) Group to manage the renewal of the NOCP and incorporate it into a new standard following the accredited processes of the Standards Council of Canada-the National Occupational Standard for Paramedics (NOSP).

The NOSP, while developed for the Canadian context, represents one of several ongoing international efforts to better understand and more accurately reflect contemporary paramedicine and paramedic practice [5-8]. We continue to experience a disconnect between paramedic practice and activities such as education, warranting a re-examination. For example, paramedics in Canada care for patients from differing environmental, social, and cultural contexts daily that are not sufficiently represented in existing practice documents [9]. Further, the perspectives and considerations of other minority and vulnerable populations that paramedics regularly care for have also historically been ignored. Examining and understanding contemporary (and future) paramedic practice in Canada will ensure that activities such as initial and continuing education, regulation, and assessment are better informed [10].

The development of the NOSP is guided by recent advances in the competency framework literature [4,9]. By adopting a systems-thinking approach, we recognize that we need to understand not only contemporary issues in paramedicine but also historical developments since 2011 and predicted future requirements to develop the NOSP. As such, this review aims to identify the emerging concepts in the paramedicine literature since 2011 to inform the development of the NOSP.

Review

Methods

The purpose of this review is to provide new insights rather than summarize past research [11]. Therefore, we elected to perform a restricted review [12,13] focused on literature informing paramedicine in Canada, published from 2011 through 2022. A restricted review (an approach in which systematic review methods are streamlined and accelerated) [13] was considered appropriate due to the need for timely information and the aim of the review. Restricted review recommendations in this study included date restrictions, setting restrictions, database limits, single reviewer extraction, and narrative synthesis [13]. This review is not intended to be a comprehensive review of the literature. To begin, we defined emerging concepts for the purpose of this study as concepts that have emerged in the paramedicine literature since the 2011 NOCP but were not well represented within that document.

Next, we searched the Cumulated Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE), and Excerpta Medica Database (EMBASE) from 2011 to 2022. In addition, we conducted grey literature searches with guidance from the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH) Grey Matters toolkit [14] on multiple organizational websites, Google Scholar [15], and Google Web. The search terms used included terms to describe paramedicine and paramedic service delivery (e.g., paramedic, EMT, EMS) [16], and an additional search was conducted with terms used to describe the Canadian context (e.g., Canada, Canadian). Subject headings were used where appropriate, and keywords and subject headings were adapted as required for individual databases. To complement these searches, we conducted a manual search and review of all 'Canadian Paramedicine' magazine issues from 2014 to 2022. This publication represents a central venue where paramedic discourse in Canada has occurred over the past four decades. We included articles of all types that discussed paramedicine in Canada but excluded news reports, media updates, those about a specific non-Canadian context, and conference abstracts. Studies in both English and French were included. Two reviewers (PP and JB) screened articles at the abstract and full-text levels, and a third reviewer (AB) resolved any conflicts. One reviewer (PP or JB) extracted the data, and a third reviewer (AB) performed a quality check on 20% of the articles. Records were imported into EndNote X20 (Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA) for full-text retrieval, Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia) for screening and extraction, and Microsoft Excel 365 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA) for further analysis.

Analysis

We conducted continuous content analysis to identify emerging concepts that were related to or could inform paramedic competencies. Informed by the frameworks of Thoma et al. [17] and Van Melle [18], we modified their original emerging concepts to reflect: a) the differences in language between physicians and paramedics; and b) the methodology of the NOSP development [5,9]. For example, we changed 'physician humanism' [17] to 'healthy professionals' [5]. One author (AB) analyzed the extracted data and deductively categorized the results into emerging concepts. This was checked with the remaining authors, and we made minor amendments to the wording of concepts, but none were removed or amalgamated.

Positionality

Author JB is a paramedic researcher and faculty member whose clinical portfolio involves substance use and mental health. Author PP is a paramedic and research assistant. Author AB is a Ph.D. paramedic researcher and faculty member who teaches professional and emerging issues in paramedicine to undergraduate and graduate students.

Results

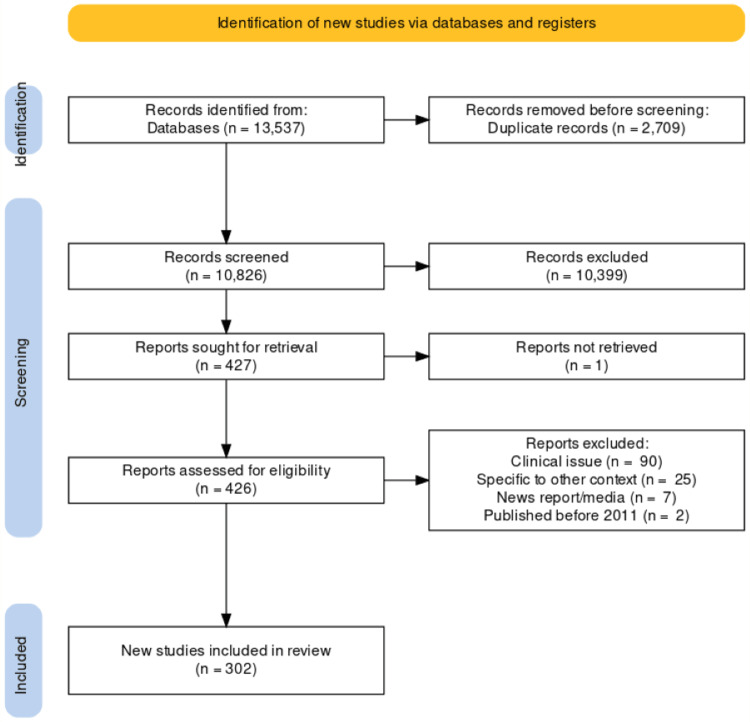

The search strategy identified 13,537 studies. After the removal of duplicates, and title and abstract screening, we excluded 10,399 studies. The remaining 427 studies underwent full-text review, during which we excluded a further 117. A final total of 302 studies and reports (216 peer-reviewed articles; 86 grey literature items), informed this manuscript (see Figure 1). Articles were published from January 2011 to April 2022. A list of included studies can be accessed online at https://bit.ly/3FFXycZ [19].

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

PRISMA: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

Table 1 outlines the emerging concepts and the number of studies that were categorized by main concept and additional concept.

Table 1. Counts of emerging concepts in the literature.

| Emerging concept | Number of articles exploring a concept as the main concept (n=) | Number of articles exploring a concept as an additional concept (n=) |

| Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility (IDEA) in paramedicine | 11 | - |

| Social responsiveness, justice, equity, and access | 49 | 15 |

| Anti-racism | 1 | - |

| Healthy Professionals | 60 | 2 |

| Evidence-Informed Practice and Systems | 76 | 10 |

| Complex Adaptive Systems | 25 | 23 |

| Learning Environment | 27 | 5 |

| Virtual Care | 2 | - |

| Clinical Reasoning | 26 | 9 |

| Adaptive Expertise | 21 | 5 |

| Planetary Health | 4 | 2 |

| Total | 302 | 71 |

Table 2 outlines the 11 emerging concepts, along with a description of the potential competencies discussed within each theme. Changes made to the names and definitions of the emerging concepts detailed in the existing literature were approved by all authors, and are referenced where applicable.

Table 2. Emerging concepts to inform the development of competencies for paramedics.

* Denotes an emerging concept that was amended to reflect differences in language between physicians and paramedics, or to reflect elements guiding the methodology of the NOSP development process.

NOSP: National Occupational Standard for Paramedics

| Emerging concept | Included topics | Principles and enabling factors | Description to inform the development of competencies |

| Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Accessibility (IDEA) in paramedicine* | Inclusion, diversity, equity; accessibility and disability; gender | Social responsiveness, shift in professional culture and identity, evidence-informed practice & systems | Competencies related to equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility within the paramedic population |

| Social responsiveness, justice, equity, and access* | Social determinants of health; equity of access to care; urban/rural disparity; structural competency | Health care along a health and social continuum, social responsiveness | Competencies related to access, equity, inclusion, and social justice within the care provided to patients [17] |

| Anti-racism | Anti-racism | Social responsiveness, health care along a health and social continuum | Competencies related to recognizing the existence of racism and actively seeking to identify, prevent, reduce, and remove the racially inequitable outcomes and power imbalances between groups and the structures that sustain these inequities [17] |

| Healthy Professionals* | Physical health; fitness; physical demands; mental health; empathy; quality of life | Healthy professionals | Competencies related to the experience of being a paramedic in a holistic sense incorporating physical health, mental health, wellbeing, spirituality, social and systemic supports. |

| Evidence-Informed Practice and Systems* | Big data; data informing practice; machine learning; technological advances; dispatch systems; evidence use | Integrate data environments, leverage advancing technology, intelligent access to and distribution of services, evidence-informed practice & systems | Competencies related to the role, collection, analysis and use of evidence and information in educational, service design and delivery, and clinical work. |

| Complex Adaptive Systems | Leadership; change; health systems science; community paramedicine program design; quality improvement; integrated care | Shift in professional culture and identity, integrated health care framework | Competencies related to the navigation of complexity within patient care, health and social care systems, and the integration of paramedic care. |

| Learning Environment* | Learning environment; research capacity; research priorities; culture; hidden curriculum; assessment | Enhance knowledge, quality based framework, continuous learning environment | Competencies related to clinical and non-clinical learning environments, and research to guide the profession. |

| Virtual Care | Telehealth; virtual clinical assessment | Evidence-informed practice & systems, intelligent access to and distribution of services | Competencies related to assessing and providing patient care in virtual environments. |

| Clinical Reasoning | Medical errors; patient safety; values-based approaches; patient/person-oriented care; efficiency; ethics; patient assessment | Patients & their communities first, quality-based framework | Competencies related to how paramedics think and function effectively in providing patient care. |

| Adaptive Expertise | Adaptive expertise; scene management; mentorship and sponsorship; team collaboration; reflective practice; self-regulation; professional development; autonomy | Promote shared understanding of paramedicine advance policy, regulation, legislation professional autonomy | Competencies related to the evolution, refinement, and development of the tools and skills required to practice effectively in a rapidly changing world. [17] |

| Planetary Health | Climate change; sustainability | Social responsiveness | Competencies related to the impact of climate and the environment on patients and paramedic services; and of patient care and paramedic service operations on climate and the environment. |

Discussion

We sought to identify the emerging concepts in the paramedicine literature in Canada since 2011 to inform a revision and update of a pan-Canadian paramedic competency framework. To do this, we performed a restricted review and a content analysis informed by the existing literature. Our study identified 11 emerging concepts in the literature that could guide or inform the development of paramedic competencies. Each of these concepts is broad and similar to the findings of Thoma et al. [17]; they mirror broader influences in paramedicine, healthcare, and society as a whole over the last decade. We will now briefly discuss a number of observations in our findings.

Despite the impact and arguable importance of contemporary social issues, we observed a lack of literature related to a number of emerging concepts in paramedicine, in particular structural competency [20,21]. For example, despite the calls to action related to Indigenous healthcare in the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada [22], only a handful of papers have explored the provision of paramedic care to Indigenous communities [23,24]. Yet Indigenous communities in Canada have faced health inequity and inequalities for decades [25,26]. Closely related to this, an area that received considerably less attention was the concept of anti-racism, with only one paper [27] outlining a call to action on anti-racism in paramedicine education and service delivery. We observed a similar lack of guiding literature related to the unique health and social care needs of members of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBTQ+) community, refugees, individuals experiencing homelessness, and many other marginalized and vulnerable populations [28-31]. Of particular concern was an observable lack of meaningful engagement with patients and caregivers from these communities in the literature we reviewed, suggesting that the needs and expectations of communities may be poorly understood. Therefore, the NOSP development process will not only need to identify the competencies required of paramedics when caring for members of diverse communities but will also need to have a concerted effort to engage, collaborate, and consult with such communities [20].

Climate change and sustainability in paramedicine have received little attention in the literature despite the serious consequences they hold for us all paramedics and communities alike. Medical education literature has acknowledged the need for current and future physicians to understand the impacts of climate change on health and wellness [32,33], and we suggest it is now past time for paramedicine in Canada to play a responsible role in this issue. While healthcare system and policy change lie outside the remit of developing the NOSP (e.g., paramedic services switching to hybrid or electric vehicles), we should endeavor to identify the competencies paramedics will need to respond to climate-related illnesses and injuries, which are predicted to increase in the coming years.

While the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has increased the use of virtual care and telehealth delivery by paramedic services [34,35], we still lack a clear understanding of the role of paramedics as virtual care providers, primary care extenders, and facilitators of virtual care visits. The COVID-19 pandemic further emphasized the benefits of keeping people out of hospitals if they can be cared for at home or in their community [34]. We, therefore, need to better understand the competencies that paramedics require to work in this novel context of virtual care, as it is closely linked to the concepts of social justice and improving access to and equity of care among isolated and remote communities. Depending on the model of virtual care employed, paramedics may need to have additional or expanded competencies in assessment, communication, care planning, and multidisciplinary collaboration, as well as technological capabilities.

Finally, we observed an encouraging and considerable increase in literature exploring health and well-being in paramedicine over the past decade. We identified a total of 60 reports exploring paramedic physical health [36,37], safety [38,39], mental health [40,41], violence against paramedics [42], mental health supports and interventions [43], and family and social supports [44]. However, we observed a continued lack of understanding related to spirituality, holistic self-care, empathy, compassion, and the impacts and influences on paramedicine culture. The existing lack of competencies related to holistic self-care and wellness in the 2011 NOCP is a priority we aim to address when developing the NOSP.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study rest in the transparent methods outlined in this manuscript, the guidance provided by existing publications [17,18], and the inclusion of grey literature representing paramedic community discourse over the last decade. We also used elements of the NOSP development process [2,4,5,9] to sensitize us and decrease the chance that important concepts were missed. However, this study has several limitations that we must acknowledge. First, we performed a restricted review that may not have captured all literature related to paramedicine in Canada. Despite the potential to have missed some themes, it is reassuring that no additional concepts were identified during analysis when compared to similar publications. Second, this study was conducted in parallel with a larger project related to standard development, and this placed logistical boundaries on the work (e.g., timeframes). Despite this, we suggest this study offers a comprehensive overview of emerging concepts that should be considered when developing the NOSP.

Conclusions

This study identified 11 emerging concepts that should be considered when developing competencies as part of the NOSP: inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility (IDEA) in paramedicine; social responsiveness, justice, equity, and access; anti-racism; healthy professionals; evidence-informed practice and systems; complex adaptive systems; learning environment; virtual care; clinical reasoning; adaptive expertise; and planetary health. We hope that in addition to informing the NOSP, the publication of this work will create greater transparency around the development process. These emerging concepts would also benefit from further engagement among the paramedic community. In doing so, we may begin to understand how they intersect with our established understanding of the system of paramedicine.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

Funding Statement

Open-access publication funded by the Paramedic Association of Canada

Footnotes

AB is a member of the Paramedic Association of Canada and is involved as a consultant and committee member across multiple projects with both the Paramedic Association of Canada and the Canadian Standards Association (CSA) Group.

JB, PP, AB declare(s) employment from Fanshawe College. AB declare(s) a grant, personal fees and Support for attending meetings/travel from Paramedic Association of Canada. AB declare(s) personal fees and Support for attending meetings/travel from CSA Group.

References

- 1.Paramedic Association of Canada. Paramedic Association of Canada: National Occupational Competency Profile for Paramedics. Ottawa, Canada: Paramedic Association of Canada; 2011. Paramedic Association of Canada: National Occupational Competency Profile for Paramedics. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Informing a Canadian paramedic profile: framing concepts, roles and crosscutting themes. Tavares W, Bowles R, Donelon B. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:477. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1739-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Four dimensions of paramedic practice in Canada: defining and describing the profession. Bowles RR, van Beet C, Anderson GS. Australas J Paramed. 2017;14:0. [Google Scholar]

- 4.A six-step model for developing competency frameworks in the healthcare professions. Batt A, Williams B, Rich J, Tavares W. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021;8:789828. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.789828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Principles to guide the future of paramedicine in Canada. Tavares W, Allana A, Beaune L, Weiss D, Blanchard I. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2022;26:728–738. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2021.1965680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The definition of paramedicine: an international delphi study . Williams B, Beovich B, Olaussen A. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:3561–3570. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S347811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Defining two novel sub models of the Anglo-American paramedic system: a Delphi study. Makrides T, Ross L, Gosling C, Acker J, O'Meara P. Australas Emerg Care. 2022;25:229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.auec.2021.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.At odds: How intraprofessional conflict and stratification has stalled the Ontario paramedic professionalization project. Brydges M, Dunn JR, Agarwal G, Tavares W. J Prof Organ. 2022016 [Google Scholar]

- 9.New ways of seeing: supplementing existing competency framework development guidelines with systems thinking. Batt AM, Williams B, Brydges M, Leyenaar M, Tavares W. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021;26:1355–1371. doi: 10.1007/s10459-021-10054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Developing the National Occupational Standard for Paramedics in Canada - update 2. Batt A, Poirier P, Bank J, et al. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/359143167_Developing_the_National_Occupational_Standard_for_Paramedics_in_Canada_-_Update_1 Canadian Paramedicine. 2022;45:6–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.On the limits of systematicity. Eva KW. Med Educ. 2008;42:852–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2008.03140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Redefining rapid reviews: a flexible framework for restricted systematic reviews. Plüddemann A, Aronson JK, Onakpoya I, Heneghan C, Mahtani KR. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018;23:201–203. doi: 10.1136/bmjebm-2018-110990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. Garritty C, Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, et al. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;130:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grey Matters: a practical tool for searching health-related grey literature. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health: Ottawa. [ Dec; 2022 ]. 2019. https://www.cadth.ca/grey-matters-practical-tool-searching-health-related-grey-literature https://www.cadth.ca/grey-matters-practical-tool-searching-health-related-grey-literature

- 15.The Role of Google Scholar in Evidence Reviews and Its Applicability to Grey Literature Searching. Haddaway NR, Collins AM, Coughlin D, Kirk S. PLoS One. 2015;10:0. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paramedic literature search filters: optimised for clinicians and academics. Olaussen A, Semple W, Oteir A, Todd P, Williams B. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2017;17:146. doi: 10.1186/s12911-017-0544-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emerging concepts in the CanMEDS physician competency framework. Thoma B, Karwowska A, Samson L, et al. Can Med Ed J. 2022 doi: 10.36834/cmej.75591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Melle E. New and emerging concepts as related to the CanMEDS roles: overview. Ottawa, Canada: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada: Ottawa; 2015. New and emerging concepts as related to the CanMEDS roles: overview. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Included studies in emerging concepts restricted review. [ Dec; 2022 ]. 2022. https://bit.ly/3FFXycZ https://bit.ly/3FFXycZ

- 20.Reconsidering systems-based practice: advancing structural competency, health equity, and social responsibility in graduate medical education. Castillo EG, Isom J, DeBonis KL, Jordan A, Braslow JT, Rohrbaugh R. Acad Med. 2020;95:1817–1822. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Toward structural competency in emergency medical education. Salhi BA, Tsai JW, Druck J, Ward-Gaines J, White MH, Lopez BL. AEM Educ Train. 2020;4:0. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Honouring the truth, reconciling for the future: summary of the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. [ Dec; 2022 ]. 2015. http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/301/weekly_acquisition_lists/2015/w15-24-F-E.html/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-7-2015-eng.pdf http://epe.lac-bac.gc.ca/100/201/301/weekly_acquisition_lists/2015/w15-24-F-E.html/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-7-2015-eng.pdf

- 23.Ashton C. Toronto, Canada: CSA Group; 2017. Health in the North: The Potential for Community Paramedicine in Remote and/or Isolated Indigenous Communities. [Google Scholar]

- 24.How air ambulance services can improve care delivered to remote indigenous communities. Tien H. Air Med J. 2018;37:294–295. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Social determinants of health inequities in indigenous Canadians through a life course approach to colonialism and the residential school system. Kim PJ. Health Equity. 2019;3:378–381. doi: 10.1089/heq.2019.0041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Improving the clinical care of Indigenous peoples. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5507231/ Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:542. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Call to action: antiracism in paramedicine. Lunn TM, Logan S, Doiron M, Cameron C. Canadian Paramedicine. 2021;44:16–19. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emergency medical services utilization by homeless patients. Abramson TM, Sanko S, Eckstein M. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2021;25:333–340. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2020.1777234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.A drug-related Good Samaritan Law and calling emergency medical services for drug overdoses in a Canadian setting. Moallef S, Choi J, Milloy MJ, DeBeck K, Kerr T, Hayashi K. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18:91. doi: 10.1186/s12954-021-00537-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.At a glance—what can paramedic data tell us about the opioid crisis in Canada? Do MT, Furlong G, Rietschlin M, et al. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2018;38:339–342. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.38.9.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paramedic identification and management of victims of intimate partner violence: a literature review. Mackey B. https://ajp.paramedics.org/index.php/ajp/article/view/510 Australas J Paramed. 2017;14 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Core competencies for health workers to deal with climate and environmental change. Jagals P, Ebi K. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18 doi: 10.3390/ijerph18083849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Climate change: what competencies and which medical education and training approaches? Bell EJ. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:31. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-10-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Batt A, Hultink A, Lanos C, Tierney B, Grenier M, Heffern J. Advances in community paramedicine in response to COVID-19 . Toronto, Canada: CSA Group; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 35.A rapid review of pandemic studies in paramedicine. Cavanagh N, Tavares W, Taplin J, Hall C, Weiss D, Blanchard I. Australas J Paramed. 2020;17 [Google Scholar]

- 36.A physical demands description of paramedic work in Canada. Coffey B, MacPhee R, Socha D, Fischer SL. Int J Ind Ergon. 2016;53:355–362. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Implementing powered stretcher and load systems was a cost effective intervention to reduce the incidence rates of stretcher related injuries in a paramedic service. Armstrong DP, Ferron R, Taylor C, McLeod B, Fletcher S, MacPhee RS, Fischer SL. Appl Ergon. 2017;62:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2017.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.What influences safety in paramedicine? Understanding the impact of stress and fatigue on safety outcomes. Donnelly EA, Bradford P, Davis M, Hedges C, Socha D, Morassutti P, Pichika SC. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1:460–473. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Developing a Canadian fatigue risk management standard for first responders: defining the scope. Yung M, Du B, Gruber J, Yazdani A. Safety Science. 2021;134:105044. [Google Scholar]

- 40.The relationship between role identity and mental health among paramedics. Mausz J, Donnelly EA, Moll S, Harms S, Tavares W, McConnell M. J Workplace Behav Health. 2021;1:16. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sleep quality and mental disorder symptoms among Canadian public safety personnel. Angehrn A, Teale Sapach MJ, Ricciardelli R, MacPhee RS, Anderson GS, Carleton RN. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:2708. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.The role of organizational culture in normalizing paramedic exposure to violence. Mausz J, Johnston M, Donnelly EA. JACPR. 2022;14:112–122. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stakeholder perspectives on internet-delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for public safety personnel: a qualitative analysis. McCall HC, Beahm JD, Fournier AK, Burnett JL, Carleton RN, Hadjistavropoulos HD. Can J Behav Sci. 2021;53:232–242. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Predictors of posttraumatic stress and preferred sources of social support among Canadian paramedics. Donnelly EA, Bradford P, Davis M, Hedges C, Klingel M. CJEM. 2016;18:205–212. doi: 10.1017/cem.2015.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]