Abstract

Objective:

This study aimed to examine the association between mindsets—established, but mutable beliefs that a person holds—and health-related quality of life in survivors of breast and gynecologic cancer.

Methods:

A cross-sectional survey study was conducted with breast and gynecologic cancer survivors. Measures included the Illness Mindset Questionnaire and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G).

Results:

273 survivors (74% breast / 26% gynecologic) who were on average 3.9 years post-diagnosis (SD=4.2), mean age 55 (SD=12) completed the survey (response rate 80%). 20.1% of survivors (N=55) endorsed (“agree” or “strongly agree”) that Cancer is a Catastrophe, 52.4% (N=143) endorsed that Cancer is Manageable, and 65.9% (N=180) endorsed that Cancer can be an Opportunity (not mutually exclusive). Those who endorsed a maladaptive mindset (Cancer is a Catastrophe) reported lower health-related quality of life (HRQOL) compared to those who did not hold this belief (p < .001). Alternatively, those who endorsed more adaptive mindsets (Cancer is Manageable or Cancer can be an Opportunity) reported better HRQOL compared to those who disagreed (all p-values < .05). All three mindsets were independent correlates of HRQOL, explaining 6-15% unique variance in HRQOL, even after accounting for demographic and medical factors.

Conclusions:

Mindsets about illness are significantly associated with HRQOL in cancer survivors. Our data come from a one-time evaluation of cancer survivors at a single clinic and provide a foundation for future longitudinal studies and RCTs on the relationship between mindsets and psychosocial outcomes in cancer survivors.

Keywords: illness mindsets, cancer survivors, health-related quality of life, gynecologic cancer, breast cancer

Lay summary:

Illness mindsets are assumptions about what an illness is, how it works, and what it means. Emerging evidence from research on breast and gynecologic cancer survivors suggests that they relate to mental and physical health and may significantly affect health-related quality of life. Given that mindsets are relatively easy to assess and can have wide-reaching effects, mindset assessments in clinical settings may offer valuable, practical advantages to enhance patient care.

Association of Illness Mindsets with Health-Related Quality of Life in Breast and Gynecologic Cancer Survivors

A cancer diagnosis does not occur in a vacuum, but rather exists in an environment rich with social, cultural, and emotional associations. As a result, cancer survivors hold certain perceptions and beliefs about their cancers, often informed by cultural narratives and personal experiences about illness, which are diverse and pervasive. Illness mindsets (e.g. “cancer is manageable”) are core assumptions about what an illness is, how it works, and what it means for a person’s life. They orient us towards certain sets of associations and expectations, ultimately influencing how we understand and act upon complex information (Zion, 2021; Zion, Dweck, et al., 2019; Zion, Schapira, et al., 2019).

Mindsets, beliefs, and attitudes are all related constructs with some overlap. Although the terms mindsets and beliefs are sometimes used interchangeably, mindsets are specific types of belief that have motivational value and are central to creating and organizing systems of meaning (Dweck & Yeager, 2019). Mindsets also differ from beliefs in that a mindset is not necessarily held to be true, but rather, is understood to be a selective viewpoint that may be useful in a given context. By using the term ‘mindset’ we capture these nuances (e.g. while cancer may have negative impacts, it is something that can be accepted, dealt with, and to some degree controlled with medical intervention) (Zion, 2021; Zion, Dweck, et al., 2019).

It is hypothesized that people use illness mindsets to make sense of the complexity inherent in being diagnosed with chronic or life-threatening illness (Zion, Schapira, et al., 2019). The terms adaptive and maladaptive are widely used in psychooncology to describe coping behaviors (Nipp et al., 2016). Evolving theories suggest that illness mindsets may also be adaptive or maladaptive, and work in self-fulfilling ways to influence the mental and physical health of cancer patients (Zion, Schapira, et al., 2019).

In cancer survivors, illness mindsets have been related to physical, social, and emotional functioning, independent of disease characteristics (e.g., cancer stage) and psychological traits (e.g., trait optimism) (Zion, 2021; Zion, Dweck, et al., 2019). Prior work suggests that mindsets may play an important role in the psychosocial outcomes of cancer survivors (Gutkin et al., 2020; Heathcote et al., 2020; Zion, Schapira, et al., 2019), who suffer disproportionate symptom burden compared to the general population (Lokich, 2019; Okonji & Ring, 2016). For example, 25% of cancer survivors report poor levels of physical health and 10% of cancer survivors report poor mental health-related quality of life (HRQOL) compared to only 10% and 6% of adults, respectively, without a cancer history (Weaver et al., 2012). While demographic and clinical factors have been shown to relate to HRQOL in cancer survivors, including among breast and gynecologic cancer populations (Mols et al., 2005; Zandbergen et al., 2019), these factors do not fully explain variability observed in HRQOL outcomes (Ashley et al., 2015).

Illness mindsets may be one of the modifiable factors related to HRQOL outcomes. This cross-sectional study examines: 1) the prevalence of three different illness mindsets among our sample of breast and gynecologic cancer survivors 2) the association between different illness mindsets and demographic and clinical variables, and 3) the association between different illness mindsets and HRQOL in this population. By studying these relationships, we can begin to provide insight into factors that may influence how illness mindsets are formed and how mindsets impact a patient’s lived experience.

Methods

Transparency and Openness

We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions, all manipulations, and all measures that were included in the study. Data may be made available to qualified researchers by request. Analytic code needed to reproduce the major analyses and survey forms used by participants is available in the supplemental materials. The study was not a clinical trial and thus the registration on clinicaltrials.gov was not required but the study was reviewed by Stanford Scientific Research Committee. Data was analyzed using SPSS Statistics 27.0.

Participants and Data Collection

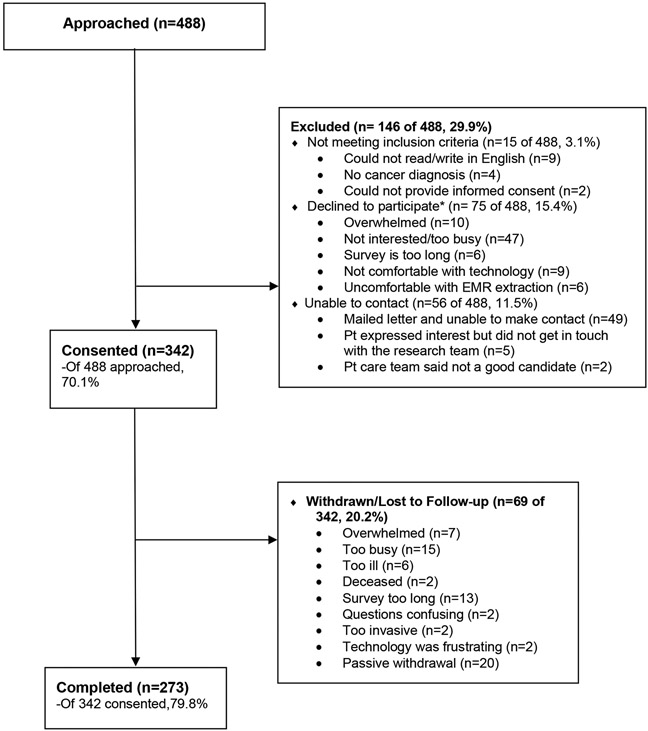

From July 2018 to March 2019, all (100% of) patients seen at the Stanford Women’s Cancer Center (serving women treated for breast and gynecologic cancers) were asked to participate in an Institutional Review Board-approved study. The questionnaire was open to all patients coming into clinic, all potential participants were approached and given an opportunity to participate. See the participant flow diagram in Figure 1. Consented participants received an email with a personalized link to an electronic survey on REDCap. Eligibility criteria included: 1) female sex at birth; 2) patient at the Stanford Women’s Cancer Center; 3) diagnosis of breast or gynecologic cancer; 4) aged 18 or older; 5) able to read and write in English; 6) able to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included: patient’s medical state made it impossible or unsafe for them to participate in the study.

Figure 1. Stanford SDP CONSORT participant flow diagram.

*Some people are counted under more than one category, 75 total people declined to participate.

Reproduced with permission of Wiley. Benedict C, Fisher S, Schapira L, Chao S, Sackeyfio S, Sullivan T, Pollom E, Berek JS, Kurian AW, Palesh O. Greater financial toxicity relates to greater distress and worse quality of life among breast and gynecologic cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology. Pages 1-12 copyright 2021 Jul 5.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the mean, median, and standard deviation of demographic and medical variables. T-tests or chi-square tests were conducted to evaluate the differences between variables. Pearson correlations were conducted to determine the degree of associations between normally distributed variables. A series of linear regressions were performed using demographic variables (i.e., age, race, income, education, ethnicity), medical variables (i.e., metastatic versus non-metastatic cancer, type of cancer, time since diagnosis, receipt of chemotherapy, radiation, hormonal therapy, surgery, and/or targeted or biologic therapy), and illness mindsets as correlates, and HRQOL as an outcome.

Measures

Demographic and medical variables

Self-reported demographic variables included age, race, ethnicity, income, and education. Participants’ medical history was extracted from their medical records and included cancer type, cancer stage at diagnosis, time since diagnosis, current treatment status, and receipt of chemotherapy, radiation, hormonal therapy, surgery, and/or targeted or biologic therapy.

Illness mindsets

Illness mindsets were measured using the Cancer version of the Brief Illness Mindset Inventory (Cancer Brief IMI), a 3-item measure of illness mindsets (Zion, 2021; Zion, Dweck, et al., 2019). The IMI has demonstrated good reliability and validity in both healthy and chronically ill patients (Zion, 2021; Zion, Dweck, et al., 2019). The IMI demonstrated strong internal consistency (α = 0.88 – 0.90), test-retest reliability (r = 0.70–0.74), and appropriate convergent validity as demonstrated by moderate effect size (correlation coefficients) in the hypothesized direction with a related measure such as illness perceptions (Brief Illness Perceptions Questionnaire, Brief-IPQ). Discriminant validity was examined looking at correlations with coping strategies (Coping Strategies Inventory - Short Form, CSI-SF), and affect (Positive and Negative Affect Scale, PANAS-S) in both healthy and chronically ill participants and was determined to be valid (Zion, 2021; Zion, Dweck, et al., 2019). For this study, we looked at the three cancer mindsets measured by the scale: the mindset that Cancer is a Catastrophe (‘cancer ruins or spoils most parts of your life’), the mindset that Cancer is Manageable (‘cancer can be managed so that you can live a relatively normal life’), and the mindset that Cancer can be an Opportunity (‘cancer can be an opportunity to make positive life changes’). Respondents rated agreement with each mindset on a 6-point Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (6). The mindsets were not mutually exclusive, and participants could endorse agreement with multiple mindsets. For data reduction purposes to preserve power, we dichotomized illness mindsets to indicate endorsement (which we defined as ‘agree’ (5) or ‘strongly agree’ (6)) and non-endorsement (‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘somewhat agree’ (4)).

Health-related quality of life

HRQOL was measured using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G), a 27-item measure comprised of four subscales: physical well-being (7 items), social/family well-being (7 items), emotional well-being (6 items), and functional well-being (7 items). All FACT-G questions were scored on a 5-point scale from ‘not at all’ (0) to ‘very much’ (4), with higher scores indicating better HRQOL (Cella et al., 1993; Yost et al., 2013).

Results

Participants

488 potential participants were approached in clinic, 342 (70.1%) agreed to participate. Sixty-nine participants withdrew from the study or were lost to follow-up (20.2%). A total of 273 participants (74% breast and 26% gynecologic cancer survivors) completed the survey (response rate 80%). The majority of participants had non-metastatic cancers (n = 240; 88%). Most participants were fewer than five years post-diagnosis (n = 208; 76%) and were on active treatment (i.e., chemotherapy, radiation, hormone, or targeted or biologic therapy) (n = 160; 59%).

The average age was 55 (SD = 12) years. Two-thirds (67%) of participants reported their race as White/Caucasian and 22% were Asian/Asian-American. Eighty-eight percent of participants identified themselves as non-Hispanic/Latino. The majority of the sample (70%) had the equivalent of a bachelor’s degree or higher. Fifty-four percent of the sample reported an income of $100,000 or more, although 43 participants (15.8%) did not report income. See Table 1 for complete demographic and medical information.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| No. (%) Participants |

|

|---|---|

| Characteristics | (N = 273) |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 55 (12) |

| Cancer type | |

| Breast | 201 (73.6) |

| Gynecologic | 72 (26.4) |

| Race | |

| White | 182 (66.7) |

| Asian/Asian American | 61 (22.3) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 4 (1.5) |

| Black/African-American | 4 (1.5) |

| Mixed race | 8 (2.9) |

| Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.4) |

| Unknown | 13 (4.8) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic/Latino | 32 (11.7) |

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 240 (87.9) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.4) |

| Income | |

| Less than $100,000 | 81 (29.7) |

| $100,000 and over | 149 (54.6) |

| Prefer not to answer | 40 (14.7) |

| Don’t know | 3 (1.1) |

| Educational level | |

| No Bachelor’s degree | 83 (30.4) |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 190 (69.6) |

| Time since diagnosis: | |

| Less than 5 years | 208 (76.2) |

| 5 or more years | 65 (23.8) |

| Cancer stage | |

| Nonmetastatic | 240 (87.9) |

| Metastatic | 31 (11.4) |

| No response | 2 (0.7) |

| Illness mindsets, mean agreement (SD) | |

| Cancer is a Catastrophe | 3.35 (1.48) |

| Cancer is Manageable | 4.45 (1.20) |

| Cancer can be an Opportunity | 4.84 (1.19) |

Illness mindset descriptive results

Participants could endorse more than one mindset. Endorsement of a mindset was defined as a response of ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree.’ Of the sample, 20.1% (n = 55) endorsed the Cancer is a Catastrophe mindset, 52.4% (n = 143) endorsed the Cancer is Manageable mindset, and 65.9% (n = 180) endorsed the Cancer can be an Opportunity mindset. There was a negative correlation between the Cancer is a Catastrophe and Cancer can be an Opportunity mindsets (r = −.19, p = .002), and between the Cancer is a Catastrophe and Cancer is Manageable mindsets (r = −.39, p < .001). Cancer is Manageable and Cancer can be an Opportunity correlated positively (r = .48, p < .001). See Table 1 for item-level data of each mindset on the 6-point Likert scale.

Illness mindsets across demographics

We found that the Cancer is a Catastrophe mindset was negatively associated with age (r = −.19, p = .002) such that younger patients were more likely to respond that cancer ruins or spoils life, while other mindsets had no significant associations with age. Asian/Asian-American participants reported higher agreement (M = 3.84, SD = 1.46) with the Cancer is a Catastrophe mindset compared to White/Caucasian participants (M = 3.16, SD = 1.39), t (241) = −3.22, p = .001. Hispanic/Latino participants reported higher agreement (M = 4.03, SD = 1.51) with the Cancer is a Catastrophe mindset compared to non-Hispanic/Latino participants (M = 3.25, SD = 1.45), t (270) = 2.83, p = .005. There were no differences by race for the Cancer is Manageable or Cancer can be an Opportunity mindsets. Mindsets did not differ across levels of educational attainment or income.

Illness mindsets and medical variables

No significant differences in any of the three illness mindsets were found across cancer type or time since diagnosis.

Cancer stage (metastatic vs. non-metastatic disease) varied with the mindsets that Cancer is Manageable and that Cancer can be an Opportunity, but not Cancer is a Catastrophe. Participants with metastatic disease reported less agreement that Cancer is Manageable (M = 3.97, SD = 1.35) compared to those who had non-metastatic disease (M = 4.51, SD = 1.18), t (269) = 2.39, p = .018. Participants with metastatic disease also reported less agreement that Cancer can be an Opportunity (M = 4.32, SD = 1.56) compared to those who had non-metastatic disease (M = 4.91, SD = 1.12), t (34.10) = 2.03, p = .05.

Treatment type varied with the mindset that Cancer is a Catastrophe only. Participants who were receiving active chemotherapy reported more agreement that Cancer is a Catastrophe (M = 3.84, SD = 1.44) compared to those who were not on active chemotherapy (M=3.29, SD = 1.48), t (271) = −2.02, p = .045. Participants who had received prior targeted or biologic therapy reported more agreement that Cancer is a Catastrophe (M = 3.78, SD = 1.45) compared to those who had not (M=3.23, SD = 1.47), t (271) = −2.54, p = .012. No significant differences were found across those on hormonal therapy, or those who had undergone prior surgery or radiation.

Illness mindsets and health-related quality of life

Participants who agreed that Cancer is a Catastrophe reported lower HRQOL (FACT-G: M = 69.15, SD = 18.37) compared to those who did not endorse this mindset (M = 81.21, SD = 15.58), t (271) = −4.94, p < .001. Participants who agreed that Cancer is Manageable reported better HRQOL (M = 85.5, SD = 14.54) compared to those who did not endorse this mindset (M = 71.38, SD = 16.15), t (271) = 7.6, p < .001. Those who agreed that Cancer can be an Opportunity also reported higher HRQOL (M = 80.91, SD = 16.95) compared to those who did not endorse this mindset (M = 74.64, SD = 15.96), t (271) = 2.99, p = .003 (Figure 2). All three mindsets maintained the associations they had with the FACT-G overall with each of the FACT-G sub-scores, which included social/family well-being, physical well-being, functional well-being, and emotional well-being (Table 2).

Figure 2. Illness Mindsets and Differences in HRQOL (FACT-G total scores) Compared to U.S. Cancer Population.

Note. The red line represents the mean FACT-G total score across the U.S. cancer population. The yellow line represents the mean FACT-G total score across our study participants. The numbers above each column represent the change in the FACT-G total score compared to the mean FACT-G total score across the U.S. cancer population.

Table 2.

Correlations Between Illness Mindsets and Quality of Life

| Pearson Correlation |

P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| FACT-G Physical Well-Being | Cancer is a Catastrophe | −0.28 | <.001 |

| Cancer is Manageable | 0.28 | <.001 | |

| Cancer Can be an Opportunity | 0.15 | 0.02 | |

| FACT-G Social/Family Well-Being | Cancer is a Catastrophe | −0.24 | <.001 |

| Cancer is Manageable | 0.25 | <.001 | |

| Cancer Can be an Opportunity | 0.14 | 0.02 | |

| FACT-G Emotional Well-Being | Cancer is a Catastrophe | −0.41 | <.001 |

| Cancer is Manageable | 0.44 | <.001 | |

| Cancer Can be an Opportunity | 0.28 | <.001 | |

| FACT-G Functional Well-Being | Cancer is a Catastrophe | −0.39 | <.001 |

| Cancer is Manageable | 0.39 | <.001 | |

| Cancer Can be an Opportunity | 0.21 | <.001 | |

| FACT-G Total score | Cancer is a Catastrophe | −0.42 | <.001 |

| Cancer is Manageable | 0.43 | <.001 | |

| Cancer Can be an Opportunity | 0.25 | <.001 |

Illness mindsets as independent correlates of HRQOL

Cancer is a Catastrophe Correlate

A stepwise linear regression was performed using a set of demographic and medical variables (i.e., age, race, income, education, ethnicity, metastatic versus non-metastatic cancer, type of cancer, time since diagnosis, receipt of chemotherapy, radiation, hormonal therapy, or surgery) and the mindset, Cancer is a Catastrophe. The selected variables accounted for 31% of the observed variance in HRQOL (adj R2 = .26; F (19, 250) = 5.92, p <.001). Correlates of higher HRQOL included older age (β = .13, p = .02), not being on active chemotherapy (β = −.24, p = <.001), and less agreement that Cancer is a Catastrophe (β = −.39, p <001). The mindset, Cancer is a Catastrophe, accounted for 15% of unique variance in explaining HRQOL.

Cancer is Manageable Correlate

A linear regression was performed using a set of demographic and medical variables as above and the mindset, Cancer is Manageable. The selected variables accounted for 32% of the observed variance in predicting HRQOL (adj R2 = .27; F (19, 250) = 6.25, p <.001), with older age (β = .16, p = .01), not being on active chemotherapy (β = −.25, p <001) and higher agreement that Cancer is Manageable (β = .39, p < .001) being significant correlates of higher HRQOL. The mindset, Cancer is Manageable, accounted for 14% of unique variance in explaining HRQOL.

Cancer can be an Opportunity Correlate

A linear regression was performed using a set of demographic and medical variables as above and the mindset, Cancer can be an Opportunity. The selected variables accounted for 24% of the observed variance in predicting HRQOL (adj R2 = .24; F (19, 250) = 4.12, p <.001), with older age (β = .21, p = .001), not being on active chemotherapy (β = −.27, p < .001), and higher agreement that Cancer can be an Opportunity (β = .25, p < .001) being significant correlates of higher HRQOL. The mindset, Cancer can be an Opportunity, accounted for 6% of unique variance in explaining HRQOL

Discussion

Illness mindsets are a new concept in behavioral health. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate illness mindsets among breast and gynecologic cancer survivors, although similar concepts, such as “health mindset” and “illness perception”, have been examined in cancer populations previously (Ashley et al., 2015; Gutkin et al., 2020). We examined three mindsets specific to cancer (Cancer is a Catastrophe, Cancer is Manageable, and Cancer can be an Opportunity) and found that these mindsets are independent correlates of HRQOL even after accounting for demographic and medical factors.

In this study, mindsets varied by age, race, ethnicity, and cancer stage, but did not differ across income, level of education, cancer type, or time since diagnosis. Specifically, younger survivors, Asian/Asian American survivors, and Hispanic/Latino survivors were more likely to hold the mindset that Cancer is a Catastrophe. Participants with metastatic cancer were less likely to hold the mindsets that Cancer is Manageable and Cancer can be an Opportunity. Participants on active chemotherapy or with prior chemotherapy or targeted or biologic therapy were more likely to hold the mindset that Cancer is a Catastrophe.

Our findings are consistent with previous research showing that health mindsets vary with age, perhaps because older patients have more experience with illness, more resources to draw from, and more nuanced understandings of health (Conner et al., 2019). Similarly, people of different racial, cultural, and socioeconomic backgrounds likely hold different beliefs about health and resources to cope, given inequalities in this country (USA) (Wardle & Steptoe, 2003). It is possible that demographic differences in illness mindsets may contribute to differences in HRQOL, and that patients with similar disease and prognosis, but different backgrounds, may hold different mindsets about their cancer.

We compared FACT-G scores from our sample to those of a larger sample of adult U.S. cancer patients (n = 4912, as reported by Pearman et al. 2014)(Pearman et al., 2014). A recent meta-analysis showed that 4–14-point changes in FACT-G scales represent small to medium clinically meaningful difference in HRQOL (King et al., 2010). In our sample, we found 4–10-point differences in FACT-G scales between those who endorsed or did not endorse specific mindsets. Further research is needed to determine the directionality of the relationship between illness mindsets and HRQOL. However, our findings suggest that illness mindsets might be a clinically important target for improving HRQOL for survivors or for identifying patients at risk for low HRQOL.

Those who endorsed the Cancer is a Catastrophe mindset showed clinically meaningful lower HRQOL compared to those who did not endorse this mindset. By contrast, those who endorsed the Cancer is Manageable and Cancer can be an Opportunity mindsets showed clinically meaningful higher scores on HRQOL compared to those who did not. Of the three mindsets, Cancer is a Catastrophe accounted for the most variance in HRQOL, while Cancer can be an Opportunity accounted for the least.

Our study has several limitations. Our data are derived from a one-time evaluation of breast and gynecologic cancer patients and survivors at a single clinic. Additionally, compared to the general U.S. cancer survivor population, Black/African-American and Hispanic/Latino patients are underrepresented in our sample and Asian/Asian-American patients are overrepresented, which may limit generalizability of the findings to other populations (Siegel et al., 2019). However, our relatively large proportion of Asian/Asian-American participants is also a strength of our study, as this is an understudied population that suffers a substantial cancer burden (Chen, 2005; Wen et al., 2014). Our sample is also exclusive to female breast and gynecologic cancer patients, which limits our ability to examine potential gender differences in health mindsets (Conner et al., 2019). The patients in our sample were also somewhat younger than the average cancer patient, with higher SES (DeSantis et al., 2010) and education levels (DeSantis et al., 2010) and more severe and complicated treatment needs, as is typical of large academic comprehensive cancer centers. Thus, our patients may be different from those seen in the community and our findings may not be generalizable to those settings.

This cross-sectional study does not allow us to determine the directionality of the relationship between illness mindsets and HRQOL. Previous randomized-controlled trials (RCTs) with healthy participants have provided preliminary evidence that altering mindsets can influence health and psychosocial outcomes (Crum et al., 2013; Howe et al., 2019; Walton & Wilson, 2018). Further research including RCTs and longitudinal studies with cancer patients are needed to determine if illness mindsets influence HRQOL in this population specifically. Given that illness mindsets are relatively easy to assess and are significantly associated with HRQOL, illness mindsets may offer valuable, practical advantages as an assessment tool in clinical settings to help clinicians monitor patient well-being or as a self-assessment tool for patients. Future research is needed to evaluate the potential of illness mindsets to be used as an interventional target for HRQOL in cancer patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose. Funding provided by Stanford Cancer Institute Innovation Grant, NCI R01CA239714.

Footnotes

Data may be made available to qualified researchers by request. Analytic code needed to reproduce the major analyses and survey forms used by participants is available in the supplemental materials.

References

- Ashley L, Marti J, Jones H, Velikova G, & Wright P (2015). Illness perceptions within 6 months of cancer diagnosis are an independent prospective predictor of health-related quality of life 15 months post-diagnosis. Psycho-Oncology, 24(11), 1463–1470. 10.1002/pon.3812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, Silberman M, Yellen SB, Winicour P, & Brannon J (1993). The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 11(3), 570–579. 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen MS (2005). Cancer health disparities among Asian Americans. Cancer, 104(S12), 2895–2902. 10.1002/cncr.21501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner AL, Boles DZ, Markus HR, Eberhardt JL, & Crum AJ (2019). Americans’ Health Mindsets: Content, Cultural Patterning, and Associations With Physical and Mental Health. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 53(4), 321–332. 10.1093/abm/kay041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crum AJ, Salovey P, & Achor S (2013). Rethinking stress: The role of mindsets in determining the stress response. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 716–733. 10.1037/a0031201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSantis C, Jemal A, & Ward E (2010). Disparities in breast cancer prognostic factors by race, insurance status, and education. Cancer Causes & Control: CCC, 21(9), 1445–1450. 10.1007/s10552-010-9572-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dweck CS, & Yeager DS (2019). Mindsets: A View From Two Eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science : A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 14(3), 481–496. 10.1177/1745691618804166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutkin PM, Fero KE, Jacobson CE, Chen JJ, Liang RV, Kolar C, Eyben R, & Horst KC (2020). Health mindset is associated with anxiety and depression in patients undergoing treatment for breast cancer. The Breast Journal, tbj.13765. 10.1111/tbj.13765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heathcote LC, Zion SR, & Crum AJ (2020). Cancer Survivorship—Considering Mindsets. JAMA Oncology. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.2482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe LC, Leibowitz KA, Perry MA, Bitler JM, Block W, Kaptchuk TJ, Nadeau KC, & Crum AJ (2019). Changing Patient Mindsets about Non-Life-Threatening Symptoms During Oral Immunotherapy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. In Practice, 7(5), 1550–1559. 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King MT, Cella D, Osoba D, Stockler M, Eton D, Thompson J, & Eisenstein A (2010). Meta-analysis provides evidence-based interpretation guidelines for the clinical significance of mean differences for the FACT-G, a cancer-specific quality of life questionnaire. Patient Related Outcome Measures, 1, 119–126. 10.2147/PROM.S10621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokich E (2019). Gynecologic Cancer Survivorship. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America, 46(1), 165–178. 10.1016/j.ogc.2018.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mols F, Vingerhoets AJJM, Coebergh JW, & van de Poll-Franse LV (2005). Quality of life among long-term breast cancer survivors: A systematic review. European Journal of Cancer, 41(17), 2613–2619. 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.05.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Fishbein JN, Eusebio J, Stagl JM, Gallagher ER, Park ER, Jackson VA, Pirl WF, Greer JA, & Temel JS (2016). The Relationship Between Coping Strategies, Quality of Life, and Mood in Patients with Incurable Cancer. Cancer, 122(13), 2110–2116. 10.1002/cncr.30025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okonji D, & Ring A (2016). Introduction. In Ring A & Parton M (Eds.), Breast Cancer Survivorship: Consequences of early breast cancer and its treatment (pp. 1–12). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-41858-2_1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pearman T, Yanez B, Peipert J, Wortman K, Beaumont J, & Cella D (2014). Ambulatory cancer and US general population reference values and cutoff scores for the functional assessment of cancer therapy. Cancer, 120(18), 2902–2909. 10.1002/cncr.28758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, & Jemal A (2019). Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 69(1), 7–34. 10.3322/caac.21551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton GM, & Wilson TD (2018). Wise interventions: Psychological remedies for social and personal problems. Psychological Review, 125(5), 617–655. 10.1037/rev0000115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, & Steptoe A (2003). Socioeconomic differences in attitudes and beliefs about healthy lifestyles. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 57(6), 440–443. 10.1136/jech.57.6.440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver KE, Forsythe LP, Reeve BB, Alfano CM, Rodriguez JL, Sabatino SA, Hawkins NA, & Rowland JH (2012). Mental and Physical Health–Related Quality of Life among U.S. Cancer Survivors: Population Estimates from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers, 21(11), 2108–2117. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen K-Y, Fang CY, & Ma GX (2014). Breast cancer experience and survivorship among Asian Americans: A systematic review. Journal of Cancer Survivorship : Research and Practice, 8(1), 94–107. 10.1007/s11764-013-0320-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yost K, Thompson C, Eton D, Allmer C, Ehlers S, Habermann T, Shanafelt T, Maurer M, Slager S, Link B, & Cerhan J (2013). The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General (FACT-G) is valid for monitoring quality of life in non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients. Leukemia & Lymphoma, 54(2), 290–297. 10.3109/10428194.2012.711830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandbergen N, de Rooij BH, Vos MC, Pijnenborg JMA, Boll D, Kruitwagen RFPM, van de Poll-Franse LV, & Ezendam NPM (2019). Changes in health-related quality of life among gynecologic cancer survivors during the two years after initial treatment: A longitudinal analysis. Acta Oncologica (Stockholm, Sweden), 58(5), 790–800. 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1560498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zion SR (2021). From Cancer to COVID-19: The Self-Fulfilling Effects of Illness Mindsets on Physical, Social, and Emotional Functioning. [Doctoral dissertation]. Stanford University. [Google Scholar]

- Zion SR, Dweck C, & Crum AJ (2019, July 8). Illness Mindsets: Improving Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Illness. The Society for Interdisciplinary Placebo Studies 1st Annual Conference, Leiden, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Zion SR, Schapira L, & Crum AJ (2019). Targeting Mindsets, Not Just Tumors. Trends in Cancer, 5(10), 573–576. 10.1016/j.trecan.2019.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.