Abstract

The Circle of Trust is a new conceptual model that can help investigators and the American Indian/Alaska Natives (AI/AN) community work together to promote inclusion of AI/AN populations in clinical trials to improve health outcomes. Racial/ethnic minority groups remain underrepresented in clinical trials and this creates the need and opportunity for novel approaches. Indigenous populations are particularly underrepresented in clinical trials. Studies show that AI/AN have the lowest representation of race/ethnic groups in the United States. American Indian/Alaska Natives suffer from significant health disparities with higher rates of morbidity and mortality and lower rates for preventative measures and access to health services. A variety of barriers to recruitment of minority patients exist at several levels including the system/institutional, interpersonal, and the individual. The authors, experts in AI/AN health and recruitment of minorities into research, collaborated to modify the currently existing and published “trust triangle” model that focuses on minority recruitment to include participants, researcher, and trusted entity. We advocate for expanding the trust triangle into a circle of trust inclusive of community. The “circle of trust” is a new conceptual model that can help investigators and the AI/AN community work together to promote inclusion of AI/AN populations in clinical trials to improve health outcomes.

Key words: American Indians, Alaska Natives, patient recruitment for clinical trials, circle of trust, triangle of trust, barriers to recruitment, trust

INTRODUCTION

Inclusion of historically underrepresented racial and ethnic groups in clinical research has been low, remains low, and does not mirror the diversity of the US population.1 For example, of the 35 million samples included in genome-wide association studies in 2016, only 5% were collected from individuals from historically underrepresented groups, although these racial and ethnic groups comprised nearly 39% of the US population.2 The lack of clinical research studies in racial and ethnic communities leads to the misapplication and overgeneralization of findings from non-Hispanic White populations to all other populations, complicating efforts at promoting health equity.

Indigenous populations are particularly underrepresented in clinical trials. One recent review of 1,500 studies on cancer showed that American Indian/Alaska Natives (AI/AN) have the lowest representation of racial/ethnic groups in the United States.3 Even among 1,800 clinical studies conducted by the National Institutes of Health’s Intramural Research Program (NIH-IRP), AI/AN individuals have remained stable at 1% of all participating individuals, a disproportionately low level. Some unique cultural and historical issues may play a significant role in the recruitment of Indigenous populations into clinical trials4 and the current strategies used to recruit AI/AN populations into medical research appear to remain inadequate as reflected by the level of participation by AI/AN populations in studies.

American Indian/Alaska Natives suffer as a result of significant health disparities with higher rates of morbidity and mortality and lower rates for preventive measures such as cancer screening and access to health services. They are often not included as a racial/ethnicity category in national data sets which negatively affects recruiting AI/AN subjects into trials. This racial/ethnicity category needs to be included in order to appropriately characterize the population, to determine health needs, and to develop effective policy and public health programs. Exclusion from data sets inhibits effective research and advocacy and gives a message of disinterest to AI/AN populations. A dearth of AI/AN researchers adds to this message and leads to difficulties in recruiting participants from this population.5 Unfortunately, there have been multiple incidents that have led to mistrust between AI/AN populations and medical researchers.6,7

The Trust Triangle for Minority Recruitment

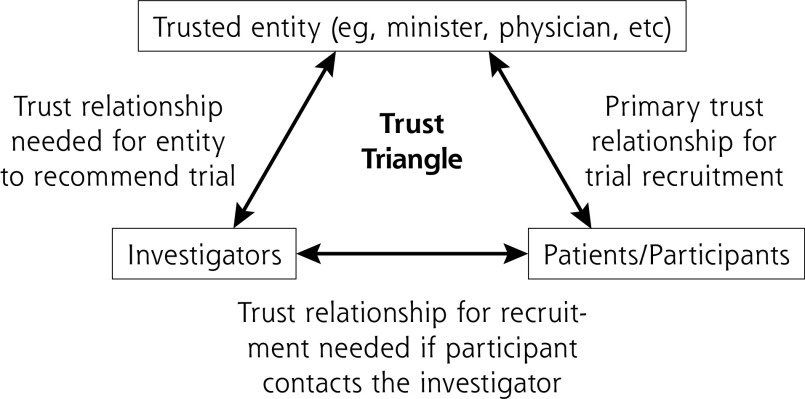

Fear and mistrust play key roles in the recruitment of ethnic and racial groups into clinical trials. A variety of barriers to recruitment of historically underrepresented patients exist at system/institutional, interpersonal, and individual levels.8 These issues are present even when the focus on minority recruitment is oriented toward referrals from clinicians. Building from points of influence and change at these different levels, the authors, experts in AI/AN health and recruitment of minorities into research, collaborated to conceptualize and implement a model, the “trust triangle” (Figure 1). This model identifies several points between the patient and the trial including the linkage between: (1) the patient and the investigator; (2) the patient and trusted entities like physicians, ministers, community leaders; and (3) the trusted entity and the investigator.

Figure 1.

The trust triangle.

A Circle of Trust May Better Fit AI/AN Populations

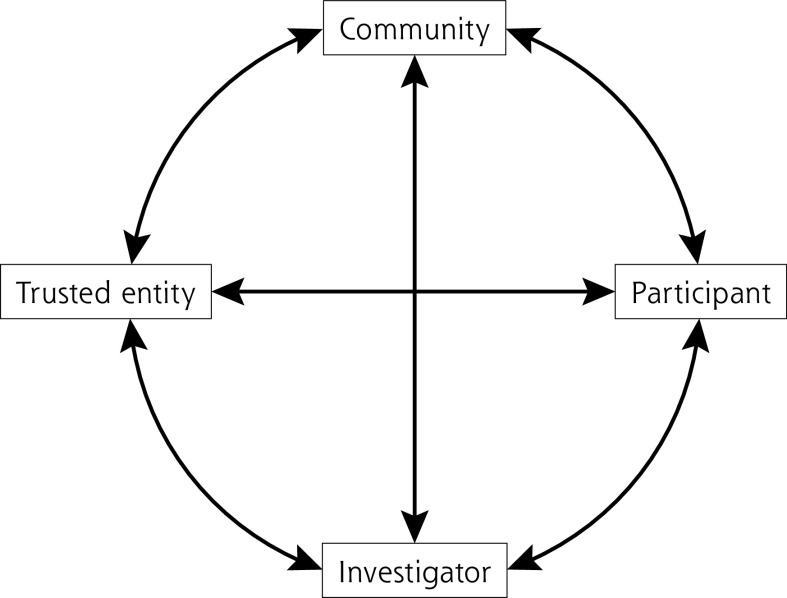

Although the trust triangle has substantial utility as a conceptual framework for the recruitment of underrepresented racial and ethnic groups into clinical research, some unique challenges in AI/AN communities may lead to a rethinking of the trust triangle into a “circle of trust.” This new circle of trust model for AI/AN populations was developed through discussions with AI/AN investigators who conduct research in the AI/AN community. This circle allows for the community perspective, involvement, and sharing to facilitate recruitment and retention in a manner that considers cultural safety and cultural humility. The 4 quadrants in the circle of trust are interdependent and balanced with reciprocity. The arrows within the figure indicate this.

The trusted entity in the circle of trust specific to AI/AN communities may be cultural leaders, elders, physicians, religious or spiritual leaders, traditional healers, tribal leaders, community leaders, nurses, traditional birth workers, community health workers, community health representatives, tribal board members, or other stakeholders. The role of the community is central to many AI/AN cultures, and the communitarian approach has helped tribes survive and thrive in the face of federal policies designed to destroy tribal nations. Such policies have contributed to significant health disparities among AI/AN populations. Novel, appropriate, and safe approaches to inclusion, recruitment, and retention of AI/AN participants are needed. Further, development and retention of AI/AN investigators is critical to enhance trust and improve subject recruitment. A proposed paradigm for community-based participatory research (CBPR) includes the community as an equal partner with the research institution and the funding agency.5

The combined influences of communitarian indigenous societies and the need for CBPR approaches to research make involving the community in clinical research a high priority in working with tribal nations. In this way, the AI/AN population can comment on how meaningful the research question is for them and the community. Therefore, the circle of trust model we propose includes the community as a key influencer in the recruitment of AI/AN participants into clinical trials, along with the investigator, participant, and trusted entity (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The circle of trust.

Although there is notable diversity among AI/AN tribes, each with their own characteristics and cultural practices and identity, defining “community” is relatively easy in tribal populations because of distinct physical borders, citizenship and enrollment processes, cultural practices, and genetic ties. Another common element is a shared history related to colonization in which tribes were often displaced from homelands, marginalized, and mistreated by colonizers. The system of research can be seen as a continuation of the colonization process through establishing control over AI/ANs by noninclusive approaches to the conduct of research, disregard for the role of the community, exclusion from data sets, and by marginalizing Indigenous academics.

Community engagement builds upon strengths of involving local people and networks, facilitating relationship building, bidirectional communication, trustworthiness, and facilitates relevant interventions. Community engagement in tribal nations has a unique history and process based on tribal sovereignty when compared with other populations. Tribes are political entities with elected officials and have a government-to-government relationship with the United States. Many tribal leaders are well aware of the history of research misconduct that has been documented with AI/AN populations.6,7 Specific strategies are needed to distinguish community approaches to research with AI/ANs, including the nuances and uniqueness of tribal institutional review boards, data ownership, lack of AI/AN academic leaders, significant poverty, and disparities that further burden populations, and a long history of justified distrust of colonized systems.

American Indian/Alaska Natives communities inherently understand interdependence upon each other, building upon each other’s strengths and weaknesses. When compared with mainstream Americans, they are far more communitarian and place a greater value on the whole rather than the individual, particularly when it comes to accumulation of money and possessions. Systems of reciprocity are commonly built into AI/AN cultures, allowing for redistribution of resources and abundance to ensure that each individual in the community has basic needs met.9 Reciprocity in the AI/AN community is much more complex than a 2-way exchange of favors, it is a deeply embedded value and practice. The value systems differ fundamentally, thus requiring a unique and individualized approach for each AI/AN community engaged in biomedical research. Without community engagement and involvement in the scientific process, including hypothesis development, data collection, analysis, and dissemination, impactful interventions are not possible.

Trust-based approaches are essential to increase diversity in clinical trials, and investigators must make recruitment of underrepresented groups a priority. For AI/AN populations, the relationship between the investigator and the subject may require conceptualizing trust in a unique and culturally sensitive manner. The circle of trust is a new conceptual model that can help investigators and the AI/AN community work together to promote inclusion of AI/AN populations in clinical trials to improve health outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: authors report none.

Funding support: Supported in part by Award Number U54GM128729 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Javier-DesLoges J, Nelson TJ, Murphy JD, et al. Disparities and trends in the participation of minorities, women, and the elderly in breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2021; 128(4): 770-777. 10.1002/cncr.33991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popejoy AB, Fullerton SM.. Genomics is failing on diversity. Nature. 2016; 538 (7624): 161-164. 10.1038/538161a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldrighetti CM, Niemierko A, Van Allen E, Willers H, Kamran SC.. Racial and ethnic disparities among participants in precision oncology clinical studies. JAMA Netw Open. 2021; 4(11): e2133205. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.33205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vigil D, Sinaii N, Karp B.. American Indian and Alaska Native enrollment in clinical studies in the national institutes of health’s intramural research program. Ethics Hum Res. 2021; 43(3): 2-9. 10.1002/eahr.500090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Warne D. Research and educational approaches to reducing health disparities among American Indians and Alaska Natives. J Transcult Nurs. 2006; 17(3): 266-271. 10.1177/1043659606288381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pacheco CM, Daley SM, Brown T, Filippi M, Greiner KA, Daley CM.. Moving forward: breaking the cycle of mistrust between American Indians and researchers. Am J Public Health. 2013; 103(12): 2152-2159. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sterling RL. Genetic research among the Havasupai—a cautionary tale. Virtual Mentor. 2011; 13(2): 113-117. 10.1001/virtualmentor.2011.13.2.hlaw1-1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thakur N, Lovinsky-Desir S, Appell D, et al. Enhancing recruitment and retention of minority populations for clinical research in pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine: an Official American Thoracic Society research statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021; 204(3): e26-e50. 10.1164/rccm.202105-1210ST [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cuc IS, Camp M.. Philanthropy as reciprocity. Cultural Survival Quarterly. Published Dec 2014. Accessed Aug 23, 2022. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/philanthropy-reciprocity

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.