Abstract

Microcirculation facilitates blood-tissue exchange of nutrients and regulates blood perfusion. It is, therefore, essential in maintaining tissue health. Aberrations in microcirculation are potentially indicative of underlying cardiovascular and metabolic pathologies. Thus, quantitative information about it is of great clinical relevance. Photoacoustic imaging (PAI) is a capable technique that relies on the generation of imaging contrast via the absorption of light and can image at micron-scale resolution. PAI is especially desirable to map microvasculature as hemoglobin strongly absorbs light and can generate a photoacoustic signal. This paper reviews the current state of the art for imaging microvascular networks using photoacoustic imaging. We further describe how quantitative information about blood dynamics such as the total hemoglobin concentration, oxygen saturation, and blood flow rate is obtained using PAI. We also discuss its importance in understanding key pathophysiological processes in neurovascular, cardiovascular, ophthalmic, and cancer research fields. We then discuss the current challenges and limitations of PAI and the approaches that can help overcome these limitations. Finally, we provide the reader with an overview of future trends in the field of PAI for imaging the microcirculation.

1. Introduction

The microvascular networks regulate blood flow to biological tissue and is the primary site for the exchange of hormones, gasses, nutrients, water and waste between blood and interstitial fluid 1,2. Microvessels, i.e. arterioles, venules and capillaries, form the microvascular networks 1. The walls of arterioles mainly comprise a layer of endothelium and smooth muscles to allow for the flow of blood into capillaries through vasoconstriction and vasodilation which are regulated by tissue oxygen concentration, autonomic nervous system and hormones1. Capillaries, the smallest blood vessels, receive blood from arterioles; and they have a single cell thick layer of the endothelium to facilitate exchange of nutrients and gasses between blood and interstitial fluid1. Capillaries terminate into venules whose walls contain fibrous tissue, which allow them to primarily act as volume reservoirs1. Any loss in blood flow, changes in oxygen concentration, dysregulation in the autonomic nervous system etc. due to various pathologies, such as diabetes, sickle cell anemia, hypertension, bodily injury and tumor growth cause disruptions in microcirculation and, in severe cases, lead to irreparable harm and even death3. Moreover, recently Covid-19 was also shown to alter tissue perfusion in severe cases of disease progression4. The ability to quantitatively image and derive functional parameters such as hemoglobin concentration, oxygen saturation, blood flow, oxygen consumption rate etc. can therefore help understand physiological and pathological processes, identify pathologies during the early onset of diseases and provide better treatment strategies to clinicians for treatment.

1.1. Microvascular imaging

Ultrasound, magnetic resonance, and optical-based techniques leverage different contrasts to image the microvasculature. A comparison of current techniques is presented in Table 1. Three dimensional noninvasive imaging of the biological target can be accomplished by modalities such as blood oxygen-level dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging (BOLD fMRI) based on variability in MRI signal due to paramagnetic property difference between oxygenated hemoglobin (HbO2) and deoxygenated hemoglobin (HbR)11,12; positron emission tomography (PET) based on the injection of radioactive substances and their subsequent detection and reconstruction13,14; X-Ray computed tomography (X-Ray CT) based on X-ray attenuation in the tissue and subsequent reconstruction at multiple angles15,16. However, these techniques suffer in terms of spatial resolution and require bulky and expensive imaging systems17. Moreover, PET and X-Ray CT employ ionizing radiation that has detrimental effects when used frequently17. Ultrasound imaging, on the other hand, is a nonionizing, inexpensive modality and leverages the mechanical contrast of the tissue to provide structural information. Recent ultrasound imaging techniques such as power Doppler and functional ultrasound (fUS), based on the Doppler effect, have been shown to be capable of imaging blood flow and volume of small vessels such as arterioles and venules18–20. Imaging capillaries, though, remains a challenge for the above imaging techniques. Various optical techniques such as optical coherence tomography (OCT) and multiphoton imaging (MPM) provide capillary level resolution while using different optical contrasts21,22 but suffer from limited penetration depth due to optical scattering within the tissue. Moreover, in cases where contrast is generated with the help of exogenous contrast agents, such as in the case of fluorescence and enhanced magnetic resonance imaging; they increase costs, require regulatory approval, and their potential toxicity may harm as well as lead to unwanted biases in the biological target23–26. Photoacoustic imaging (PAI) has emerged, in the past decade, as a reliable multi-scale imaging modality for imaging the microvasculature. PAI overcomes the above limitations by utilizing the rich optical contrast generated by the inherent optical absorption of various endogenous chromophores such as lipids, melanin, and hemoglobin17,23,27–32.

Table 1.

Comparison of different imaging modalities fUS: functional ultrasound, OCT: Optical Coherence Tomography, MPM: multiphoton microscopy, PAT: photoacoustic tomography, AR-PAM: acoustic resolution photoacoustic microscopy, OR-PAM: optical resolution photoacoustic microscopy.

1.2. Major Implementations of Photoacoustic imaging

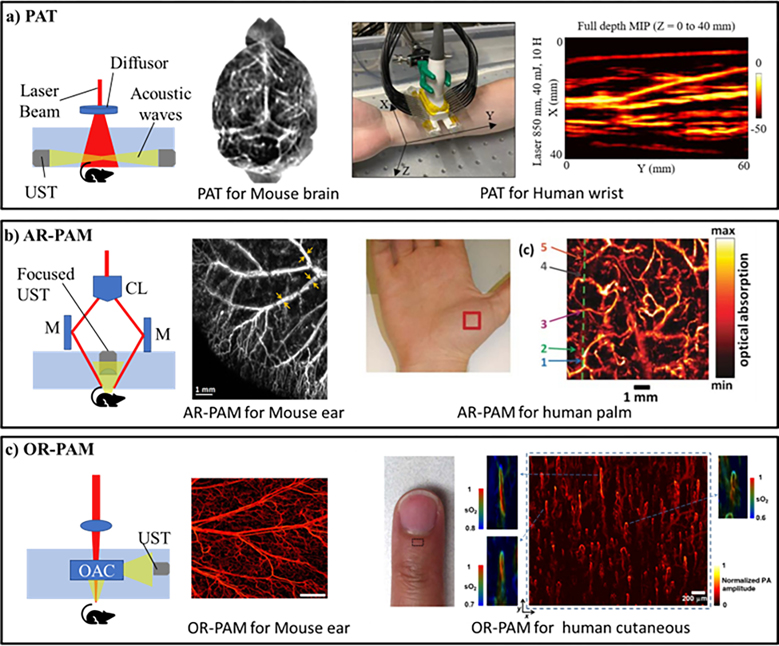

PAI, based on the photoacoustic effect33, relies on the generation of acoustic waves by the biological tissue when illuminated by a laser pulse. Photons absorbed by chromophores in biological tissue generate heat which leads to the localized expansion and contraction of tissue leading to the generation of pressure waves which are then captured by an ultrasound transducer. PAI is a versatile imaging modality and can be implemented from macroscopic to microscopic scales32; the basic setups of some of its major implementations are shown in Figure 1. The figure insets show representative maximum intensity projection (MIP) images of tissue vasculature at different scales.

Figure 1:

Implementations of photoacoustic imaging: a) Photoacoustic tomography (PAT) setup with maximum intensity projection (MIP) image of mouse brain and human wrist. b) Acoustic resolution photoacoustic microscopy (AR-PAM) setup with MIP image of mouse ear and human palm vasculature. c) Optical resolution photoacoustic microscopy (OR-PAM) setup with MIP image of mouse ear and human cutaneous vasculature. UST: Ultrasound transducer, M: Mirror, CL: Conical lens, OL: Objective lens, and OAC: Opto-acoustic combiner Reprinted with permission from34–39

Photoacoustic tomography (PAT) employs wide-field illumination with a single element scanning transducer or an array of transducers for multi-dimension imaging17,40. A handheld probe using multispectral optoacoustic tomography (MSOT) is another powerful form of PAT and relies upon an extended spectrum to identify different chromophores based on their spectral characteristics41. While PAT setups are important for studying the macrovasculature at several centimeters depth within the tissue with no to minimum invasiveness, the use of unfocused light limits its capability to resolve the capillary network. Photoacoustic microscopy overcomes the limitation at the cost of imaging depth and can achieve sub-micrometer resolutions31. Depending on acoustic or optical focusing, photoacoustic microscopy setups can be broadly classified into acoustic resolution photoacoustic microscopy (AR-PAM)28,42 and optical resolution photoacoustic microscopy (OR-PAM)31,43,44. AR-PAM employs a tighter acoustic focus than optical focus allowing it to image deeper as biological tissue scatters optical waves more than acoustic waves45. On the other hand, OR-PAM employs tighter optical focus allowing it to achieve superior sub-micron resolution at the cost of depth46. Overall, OR-PAM is most suitable to image and quantitatively assess capillary networks information due to its sub-micrometer resolutions. Another implementation of photoacoustic microscopy is photoacoustic remote sensing (PARS) which relies on intensity changes in reflected probe beam due to refractive index changes in the absorbers47. The key merit of PARS is its ability to remove the need for a coupling medium to transmit the acoustic waves and allows for all-optical detection. PAI has also been demonstrated to be capable of super-resolution imaging based on nonlinear effects, wavefront shaping, blind speckle illumination, photoacoustic temporal fluctuations and tracking and localization of flowing microbeads48. Overall, the various implementations of PAI demonstrate its versatility and its multi-scale capabilities.

In the subsequent sections, we discuss the quantitative analysis in PAI useful for deriving functional information about the microvasculature. This is followed by applications of photoacoustic imaging for different biological studies in brain, cardiovascular, ophthalmic and cancer studies. Finally, we discuss the current limitations of PAI, followed by discussions on various approaches undertaken to overcome these limitations and future trends.

2. Quantitative analysis

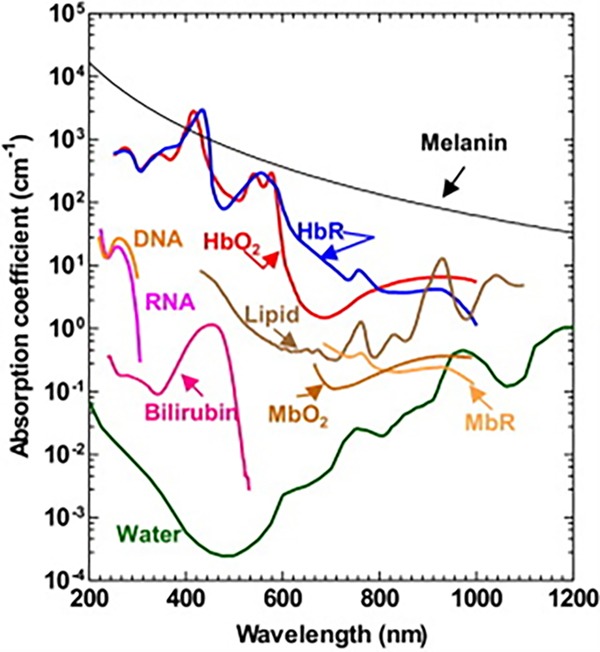

One of the key advantages of PAI is the presence of many endogenous chromophores in biological tissue that absorb light and can provide a photoacoustic response. These include lipids and water (found in tissue); DNA and RNA (found in cell nuclei); reduced myoglobin (MbR) and oxy-myoglobin (MbO2) (found in skeletal muscles); melanin (found in inner layers of the epidermis and iris); oxy-hemoglobin (HbO2), de-oxy hemoglobin (HbR) and bilirubin (circulating in blood). The absorption spectrum for each chromophore is plotted in Figure 2 at nominal concentrations. Hemoglobin is the most commonly imaged chromophore as it absorbs 100 times more photons than the surrounding tissue (lipids) in the visible light region. The photoacoustic signal (p) from photon absorption in PAI is directly proportional to the detection system’s proportionality constant: k, Grueneisen parameter: Γ, heat conversion efficiency: η, absorption coefficient: μa (cm−1) and optical fluence: ϕ (J/cm2), and is given as17,27

| (1) |

Figure 2.

Absorption spectrum of endogenous chromophores found in tissue at nominal concentrations. HbO2: Oxy-hemoglobin, HbR deoxy-hemoglobin, MbR: reduced myoglobin, and MbO2: oxy-myoglobin. Reprinted with permission from49.

The ultrasonic transducer provides an electrical signal proportional to the pressure wave from which the optical absorption coefficient for the chromophore can be extracted. In the case of hemoglobin, at a particular wavelength, we receive the combined absorption coefficient from its two major components, HbO2 and HbR. They both exhibit distinct absorption spectra; therefore, methods such as using two wavelength28, utilizing different relaxation times in optical absorption saturation profiles50, using ultrashort pulses with different pulse widths27, etc. can provide us with two photoacoustic signals under different parameters from which relative HbO2 and HbR concentrations (CHb and CdHb) can be calculated. The photoacoustic signals in the case for two different wavelengths (λ1 and λ2) are given as17

| (2) |

| (3) |

where ϵHb and ϵdHb are the molar excitation coefficients and A=kΓηϕ. Solving the two linear equations, the relative HbO2 and HbR concentrations are given as

| (4) |

| (5) |

The above equations assume depth and wavelength independent optical fluence, however this assumption can induce quantitative inaccuracies in hemoglobin concentrations. Therefore, optical fluence compensations methods such as treating optical fluence as a combination of a base spectral function to account for wavelength dependency51 and maximum entropy based reconstruction52 have been employed. Parameters such as total hemoglobin concentration and oxygen saturation of hemoglobin can further be derived from equations (4) and (5). The total hemoglobin concentration is the addition of HbO2 and HbR concentrations and is given as

| (6) |

The hemoglobin oxygen saturation can be computed using,

| (7) |

Additionally, PAI has also been investigated to measure blood flow, by utilizing the photoacoustic Doppler effect53,54. Assessment of hemoglobin concentration, oxygen saturation and flow speed allows for further quantification of the metabolic rate of oxygen (MRO2)55. For a region of interest with draining and feeding vessels, MRO2 is given as55

| (8) |

where β is oxygen binding capacity of hemoglobin, vin and vout are feeding and draining average blood flow velocities, Ain and Aout are the cross-sectional areas of the feeding and draining vessels, sO2in and sO2out are the oxygen saturation of feeding and draining vessels, and W is the region of interest. MRO2 gives the oxygen consumed by a region the tissue and is an important indicator of tissue health and viability. PAM, with its superior resolution, is well suited to quantitatively provide multiple hemodynamic parameters with important biological applications.

3. Applications of Photoacoustic Imaging

3.1. PAI for brain studies

Microcirculation in the brain plays a vital role in meeting the ever-dynamic metabolic requirements of the brain. This demand is met by a large capillary network (~3% of brain volume56) in close proximity to neurons (mean distance of ~15 μm from individual neurons57). In essence, synchrony between neural activity and regulation of microcirculation (through vessel dilation and contraction) exists, called neurovascular coupling58,59. Microcirculation in the brain is additionally associated with the blood-brain barrier function, which acts as a protective shield around the brain to inhibit entry of toxins60. Dysfunction in the microcirculation, therefore, may not only be indicative of existing brain diseases but could also play an essential role in their pathenogenesis, such as in the case of Alzheimer’s61,62. PAI has gone through two decades of extensive development and has demonstrated its viability in imaging brain vasculature in rodents and humans63,64. Besides being able to image cerebral microvasculature, photoacoustic imaging can also leverage voltage sensitive dyes to provide a measure of membrane potentials at larger depths in comparison to fluorescence imaging 65,66.

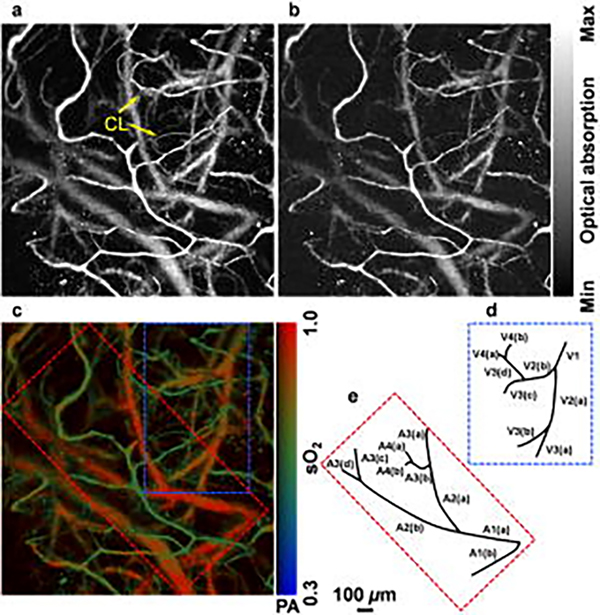

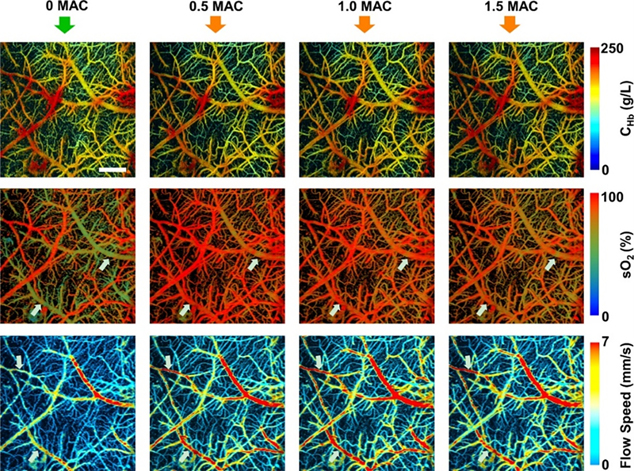

Wang et al.68,69 first reported the use of PAT for imaging hemodynamic responses in the rat brain noninvasively; they observed localized hemodynamic changes to right and left whisker stimulations. Later, Hu et al.67 improved upon the resolution to a single capillary level using OR-PAM in a rat brain through the intact skull with the scalp surgically removed. The OR-PAM setup, due to its <10 μm resolution, was able to resolve capillaries down to a depth of 0.6 mm even with the skull intact. Moreover, they mapped gradients of blood oxygen saturation allowing for possible studies of brain metabolism. A portion of their results are shown in Figure 3. Another important study with an OR-PAM setup by Yao et al.27 mapped vascular morphology and assessed blood oxygenation and metabolism changes in the anesthetized mouse brain through the intact skull. This allowed them to study mouse cortical hemodynamics under electrical stimulation. The study showed OR-PAM’s capability to provide multi-parametric information, which is its key advantage over other neuro-imaging modalities. Skull bone limits the penetration depth and induce acoustic distortions which leads to imaging artifacts70. Techniques such as skull thinning and craniotomy can circumvent acoustic scattering caused by the skull71–73. Post processing techniques such as deconvolution and vector space similarity models have also been proposed to correct the effects of acoustic aberrations caused by the skull74,75. Moreover, earlier photoacoustic neuroimaging used anaesthetized rodent models. However, it is now known that anesthesia can induce changes in the brain and can potentially create biases in functional studies76. Recent studies, therefore, have moved towards imaging the brain in awake states. Cao et al. 72 used a head restraint OR-PAM setup for awake mouse brain imaging through a cranial window on a thinned skull. The results are shown in Figure 4. Interestingly, the study also assessed anesthesia (isoflurane) induced cerebral hemodynamic and metabolic changes and studied the possible mechanism of neuroprotection by anesthetics. OR-PAM setup has also been demonstrated in freely moving rats in wearable form, allowing for imaging cerebral neurovascular variations through a cranial window under ischemic and perfused conditions73. Motion artefacts from breathing and heart pulsations, can be a limiting factor on image quality especially in head mounted setups. Therefore, motion correction methods such as deblurring methods and deep learning algorithms have been studied to improve imaging quality77–80. PAI has also been demonstrated for functional imaging of the human brain with 1024 parallel ultrasonic transducers placed hemispherically over the human head with the subject having a hemicraniectomy63. The study had a field of view of 10 cm diameter, a spatial resolution of 350 μm and a temporal resolution of 2 sec. The study demonstrated PAI’s potential to be an alternative to fMRI for the functional study of the human brain. Additionally, the lack of magnetic waves could make it more suitable for patients with metal implants.

Figure 3.

(a), (b) Maximum intensity projection of PAI at 570 and 578 nm through the intact mouse skull. (c) Oxygen saturation map. (d),(e) Venular and arteriolar tree derived from the oxygen saturation map blue and red subsets. Reprinted with permission from67.

Figure 4.

Total hemoglobin concentration (CHb), oxygen saturation and blood flow speed at different concentrations of isoflurane in mouse brain. The white arrows indicate the changes induced by isoflurane in sO2 and blood flow speed at different concentrations. Reprinted with permission from72

3.2. PAI for Cardiovascular Studies

Cardiovascular diseases remain the leading cause of death worldwide, with an estimated 17.9 million deaths due to cardiovascular diseases in 2019 of which 85% were the result of heart attack and stroke81. Microcirculatory dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases can lead to death due to septic shock and heart failure independent of changes in systemic macrocirculation82. The severity of microcirculatory dysfunction and its early onset are also potential indicators of the severity of the disease progression 82–85. Furthermore, in the case of patients under shock, the resuscitation attempts are targeted at correcting systemic hemodynamic variables such as blood pressure, flow and blood oxygen saturation with the underlying assumption that microcirculatory changes correlate favorably with macroscopic alterations (hemodynamic coherence)86. However, for reasons such as the nature of diseases or ineffectiveness of the administered treatment, an adequate degree of tissue perfusion and oxygen supply may not be achieved, leading to the breakdown of coherence between microscopic and macroscopic alterations87. In other cases such as diabetes mellitus and hypertension, microcirculatory alterations have been shown to bring forth complications like microvessel rarefaction, retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy88–90. Therefore, imaging modalities providing information for the evaluation of functional microcirculatory parameters, such as PAI, are of prime importance for the assessment of cardiovascular diseases as well as the administration of effective treatment. Conventionally, for cardiovascular disease assessment, the microvasculature is imaged at the cutaneous, sublingual or over the organ of interest directly during surgery using handheld vital microscopes87. PAI offers a potential alternative with its high penetration depth and ability to provide multi-parametric information. PAI has been employed for studying the morphology of atherosclerotic plaques as well as the detection of blood clots 91–95. Another application of PAI is its ability to aid radiofrequency ablation to treat atrial fibrillation as it can provide reliable imaging of lesions in real time with high resolution and depth91,96.

Lv et al.97 used PAT to image thoracic vessels and whole heart morphology with a spatial resolution of ~200 μm at 10 mm deep of a mouse heart. They could ascertain areas affected by myocardial infractions and show their progression with time. Another study98 using PAT demonstrated volumetric imaging of the entire Langendorff-perfused mouse heart with a spatial resolution ~150 μm using myoglobin as the primary optical contrast agent. Zemp et al.99 employed a the photoacoustic microscopy setup for the first time in 2008 for studying Murine cardiovascular dynamics, achieving a lateral resolution of 100 μm and an axial resolution of 25 μm. While they achieved this in real time, the lack of optical focusing limited the system’s spatial resolution. Song et al.43 employed an OR-PAM setup to the ear of a nude mouse in-vivo; they were able to resolve down to the scale of a single microvessel with a lateral resolution of 5 μm and axial resolution of 15 μm. More importantly, they used the functional parameters obtained to study microhemodynamic activities i.e. vasomotion under systemic hyperoxic and hypoxic conditions; results are shown in Figure 5. These parameters are important indicators in assessing cardiovascular events such as ischemia, where vasomotion is hypothesized to compensate tissue oxygenation under low oxygen conditions100. Furthermore, a study by Chen et al.101 utilized two different objectives to image cardio-cerebrovascular development and the whole body vascular development in zebrafish embryo using an OR-PAM setup, showing the potential of PAI for multi-scale imaging; the results are shown in Figure 6. This study had powerful applications in understanding various cardiovascular pathologies such as hypertension, atherosclerosis and myocardial infarctions. AR-PAM was used for human palm microvasculature imaging and showed that arterial occlusion decreased blood oxygen saturation in addition to its transient increase over nominal levels immediately after the occlusion event102. Another study used switchable optical and acoustic resolution photoacoustic setups and resolved features of human skin layers and microvascular networks down to 1.8 mm of depth103. MSOT has also been used for cardiovascular studies such as carotid artery imaging104,105 and evaluating microvascular dysfunction in systemic sclerosis106. Yang et al.107 further utilized a multi-modal ultrasound and photoacoustic system to image radial and carotid arteries. The system used structural information from ultrasound images to guide photoacoustic reconstruction which led to 50% higher contrast to noise ratio and 17% higher structural similarity index.

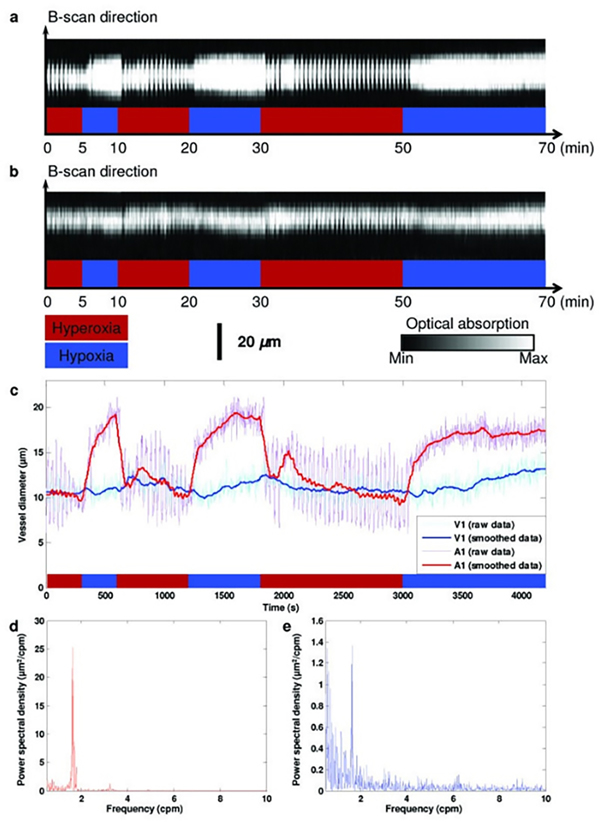

Figure 5.

a) B-scan for temporal monitoring of A1 arteriole. b) B-scan for temporal monitoring of V1 venule. c) Changes in the vessel’s diameter in response to changes in physiological state, with vasodilation clearly observed in smoothed data. d), e) Power spectrum of vasomotions tone in arteriole and venule, respectively. A1: a representative arteriole; V1: a representative venule. Reprinted with permission from43.

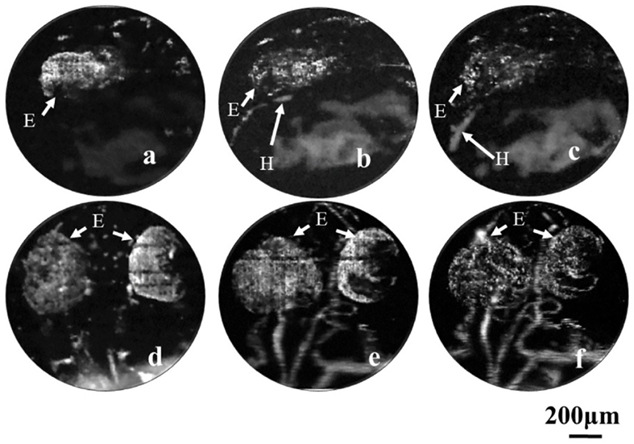

Figure 6.

a)-c): Longitudinal monitoring of heart development in zebrafish embryo using ORPAM at 22, 25 and 28 hours after fertilization, respectively. d)-f) Zebrafish embryo longitudinal vascular development at 36, 48 and 72 hours after fertilization, respectively. H: Heart E: Eye. Reprinted with permission from101.

3.3. PAI for Ophthalmic Studies

Vision results from multiple components of the eye working in harmony to process the input optical sensory data and converting it into electrical signals for further processing. The eye is formed by three coats: the outer coat consists of cornea and sclera; the middle coat (uvea) consists of the choroid, ciliary body and iris; the innermost layer comprises of the retina108. The uveal layer contains the main blood supply to the eye and nourishes different retinal layers108. Several pathologies in the eye lead to changes in microcirculation; for example, diabetic retinopathy has been associated with leukostasis, where leukocytes attach themselves to the endothelium of capillaries leading to ischemia and neovascularization108,109. Retinopathy of prematurity is another pathology seen in infants which results from aberrations in retinal vascularization110. Other pathologies which affect optical pathways, such as multiple sclerosis, have been shown to alter microcirculation in the eye as well111. Moreover, studies have shown alterations in microcirculation in the eye from conditions like aging and long term contact lens wear112–114. Therefore, imaging microcirculation has various potential applications in understanding the eye’s pathophysiological processes. The transparent nature of the eye makes optical imaging techniques well suited to observe its microcirculation. However, the eye is a fragile organ, and it is important to consider safety properties, especially in the case of optical techniques, to check for any photodamage115. A discussion on safety levels for radiation for ophthalmic imaging can be found here116,117. Types of PAI techniques used to image the eye can be broadly categorized based on contrast; hemoglobin and melanin being the primary endogenous chromophores in the eye117. Due to the topic of this review, we will limit our discussion to microcirculation imaging and refer the reader to various excellent studies117–121 using PAI for melanin imaging in the eye.

Zerda et al. first proposed and demonstrated in-vivo photoacoustic ocular imaging in 2010 to study blood distribution across choroid, sclera and optic nerve in a rabbit eye 123. The employed AR-PAM setup led to resolutions of >200 μm laterally and >50 μm axially. Hu et al.122 used OR-PAM to achieve a far superior lateral resolution of 5 μm allowing them to image iris microvasculature and resolve single RBC traveling in iris capillaries in an albino mouse. By employing two wavelengths, they were able to measure blood oxygen gradients and observe oxygenation transition from arteries to veins; the results are shown in Figure 7. Wu et al.124 used an OR-PAM setup at a similar lateral resolution of 5 μm and imaged the posterior segments of the mouse eye. However, the laser energy used was 2.6 times above the safety limit. Moreover, the photoacoustic microscopy setup discussed above used a coupling medium that needed to be in contact with the target. This is undesirable for clinical translations as it may lead to patient discomfort and create further complications in the eye. To overcome this, Hosseinaee et al.125 used a PARS setup to image vasculature and oxygenation in the mouse eye at 4.3 μm spatial resolution; the results are shown in Figure 8. The study provided structural and functional information about the vasculature and melanin using contact and label free photoacoustic imaging. PAM has been rapidly advancing towards in-vivo human imaging, with feasibility studies demonstrated recently in more closely resembling animal models such as rabbit126–128 and ex-vivo human cadavers129.

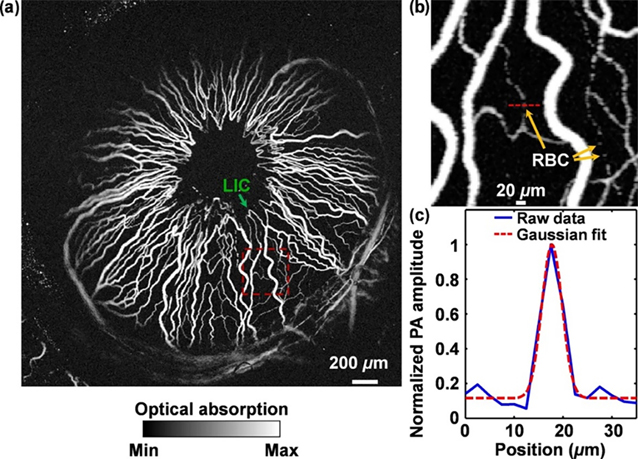

Figure 7.

a) Photoacoustic MIP of the iris microvasculature of a living adult Swiss Webster mouse. b) Close up image of red dashed box in a). c) RBC profile across the red dashed line in b). LIC, lesser iris circle; PA, photoacoustic signal. Reprinted with permission from122

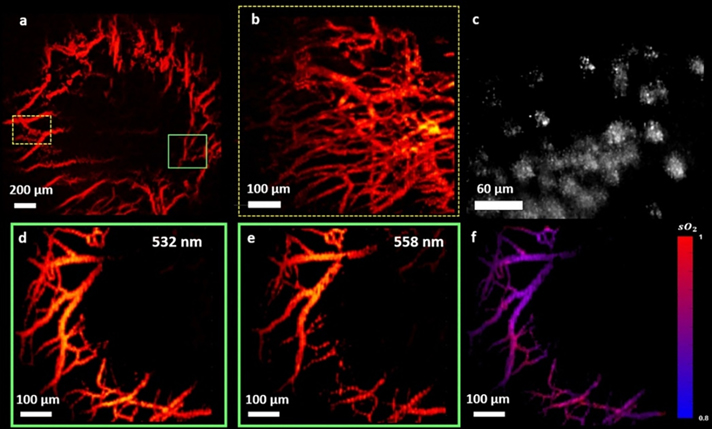

Figure 8.

a) Micovasculature MIP of iris imaged using PARS in-vivo of mouse eyes. b) Vascular image around the iris across yellow dashed box region in a). c) Melanin content of retinal pigment epithelium and choroid layers. d), e) Dual wavelength (532 and 558 nm) MIP photoacoustic images of vasculature across the green box in a). f) Corresponding sO2 map derived from the two wavelengths photoacoustic signal. Reprinted with permission from125.

3.4. PAI for Cancer Studies

Cancer is one of the leading causes of death globally, with an estimated 10 million deaths globally in 2020130,131. A large number of these deaths result from cancer spreading to other organs in the body; this is due to the ability of tumor cells to circulate through the intravascular system leading to secondary malignant growth at a distant site. This process is called metastasis132. For tumor cells to grow beyond a certain limit or metastasize, they require the formation of new blood vessels for oxygen and nutrients; this process of new vessel formation is called angiogenisis133,134. Moreover, clinical therapies such as antiangiogenic drugs target neovascularization by inhibiting the supply of nutrients and consequently starving the tumor135. Hypoxia is another condition that has been studied for tumors and has correlations with malignancy and affects the efficacy of therapy136. Monitoring the microvessels functionally has important application in understanding tumor development, early detection of cancer and monitoring the efficacy of new therapeutic drugs. PAI, using hemoglobin as the chromophore, can image tissue microvasculature as well as blood oxygen saturation and therefore is well suited to study angiogenesis and hypoxia in tumors. Additionally, melanoma, the malignant growth of melanocytes, contains melanin that can provide photoacoustic contrast, making PAI well suited for melanoma studies as well137–139.

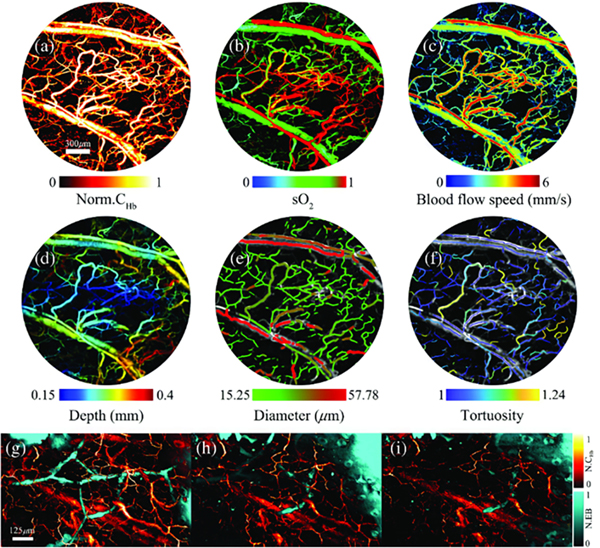

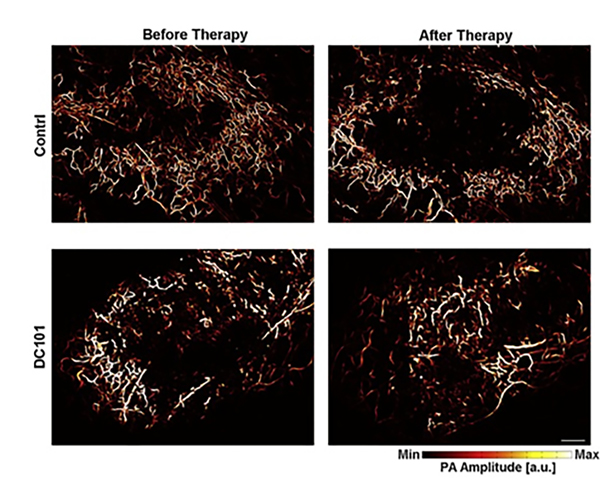

Photoacoustic tomography setups have been implemented for both in-vivo rat brain studies and clinical applications, leading to various functional assessments of different cancer processes, especially angiogenesis and hypoxic conditions in tumor cells140–145. However, due to resolution limitations, tomographic setups cannot provide information about the subtle alterations in capillary networks, which have applications in understanding tumor physiology and early detection of therapeutic response146. Photoacoustic microscopy has therefore been employed for the visualization of finer vasculature. Lin et al.147 employed OR-PAM to monitor angiogenesis in a mouse subcutaneous dorsal tumor model. They were able to quantitatively assess the morphological changes in the vasculature network over days, showing the potential of OR-PAM in studying the pathophysiology of tumors. Liu et al.148 recently used a five wavelengths based OR-PAM to image blood vessels as well lymphatic vessels at the same time while quantifying multiple contrasts from hemoglobin concentration, blood flow, oxygen saturation, and exogenous dyes. These measurements allowed them to study tumor growth by visualizing angiogenesis and oxygen saturation changes in a mouse ear with implanted with 4T1 breast cancer cells, as shown in Figure 9. OR-PAM was also utilized for imaging efficacy of anticancer drugs146,149; Figure 10 shows the OR-PAM images of changes by therapeutic effects of DC101, an antiangiogenic agent, for treating prostate cancer in a mouse ear xenograft model146. The analysis showed how after the administration of drugs, intratumoral vessels developed in contrast to the control group where they remained at the periphery; this normalization of tumor vasculature can increase the efficacy of conventional therapies for treating tumors due to more efficient oxygen and drug delivery150. OR-PAM, therefore, has important applications for studying cancer pathology and understanding the efficacy of therapeutic drugs.

Figure 9.

a)–f) OR-PAM imaging of tumor region functional parameters in breast cancer cell implanted mouse ear i.e. hemoglobin concentration, oxygen saturation, blood flow speed, depth, diameter, and tortuosity. (g)–(i) Simultaneous OR-PAM imaging of hemoglobin and dye labeled lymphatic vessels at 0, 10, and 20 min after dye injection. Reprinted with permission from148.

Figure 10.

OR-PAM characterization of vascular response to cancer drug administration in the prostate. Photoacoustic MIP images in control and drug administered tumors before and after therapy. Scale bar, 0.5mm. Reprinted with permission from146.

4. Current Challenges and Future Trends

Although PAI has demonstrated significant potential to image microcirculation, the modality suffers from inherent limitations; for example, PAI can only provide functional information with contrasts arising from optical absorption in endogenous chromophores such as hemoglobin but misses the surrounding tissue morphology. One way is the use of exogenous agents (molecular probes) which can significantly expand the imaging capabilities of photoacoustic setups by improving contrast as well as allow imaging of targeted molecules151,152. Multimodal setups can overcome this limitation by leveraging different imaging contrast such as optical backscattering (OCT), fluorescence (confocal and multiphoton microscopy) and acoustic impedance mismatch (ultrasound) to provide complementary anatomical, structural and functional information153. Song et al.154 demonstrated simultaneous imaging of green fluorescent protein expressing neurons and cortical microvasculature, providing insights into the cortical microarchitecture of neurons and vasculature. The study has the potential to be beneficial in studying neurovascular coupling. OCT has been extensively used to study structural information in the eye 155 but cannot provide functional information. PAI, therefore, has been combined with OCT to provide comprehensive anatomical and functional details of structures within the eye126,128,129,156,157. Since PAI uses an ultrasound receiver, US modalities have also been explored for multimodal setups as they can be easily integrated158–160. For example, a recent study integrated power Doppler, brightness mode (B-mode), photoacoustic computed tomography (PACT) and OR-PAM to reveal comprehensive morphological and functional information about tissue161. However, challenges remain in seamless integration while keeping the setup complexity and cost in check; for example, different optical modalities require different laser sources and need to be combined using additional components such as dichroic mirrors154. One way to reduce complexity is to use a single laser source that meets the requirements for different modalities, such as supercontinuum laser sources, which have been employed for combined PAI and OCT162.

Moreover, conventional OR-PAM setups have bulky imaging heads, hindering their integration with other imaging modalities163. The bulky imaging head results from the need to accommodate opaque transducers. This requires a large coupling medium that is in contact with the imaged target. In contrast, PARS overcomes this limitation but requires the use of an additional laser. A solution to this is to employ transparent ultrasound detectors as they can be placed in close proximity to the biological tissue. This allows them to capture acoustic waves without an external coupling medium. Different transparent ultrasound detectors based on interferometric, piezoelectric and micromachined detection have been studied164,165. Furthermore, the transparent transducers allow for coaxial transmission and reception of laser and acoustic beams, which simplifies the PAI setup and allows seamless integration with other optical and ultrasound modalities. Optical transducers such as Fabry Perot based on interferometric detection of ultrasound are promising transducers that have been explored for endoscopic PAI applications166,167. Piezoelectric transparent ultrasound transducers (TUTs) based on lithium niobate (LiNbO3)168 and lead magnesium niobate-lead titanate (PMN-PT)163,169 have also been investigated for photoacoustic applications; they significantly reduce imaging head size, require minimum coupling and can be used in either a single element or linear array form factor. Overall, piezoelectric transducers exhibit higher sensitivity in comparison to optical transducers17. However, the latter is more suitable for miniaturization as the piezoelectric transducer’s sensitivity per unit area reduces significantly with a reduction in size, whereas optical transducer’s sensitivity is independent of size17.

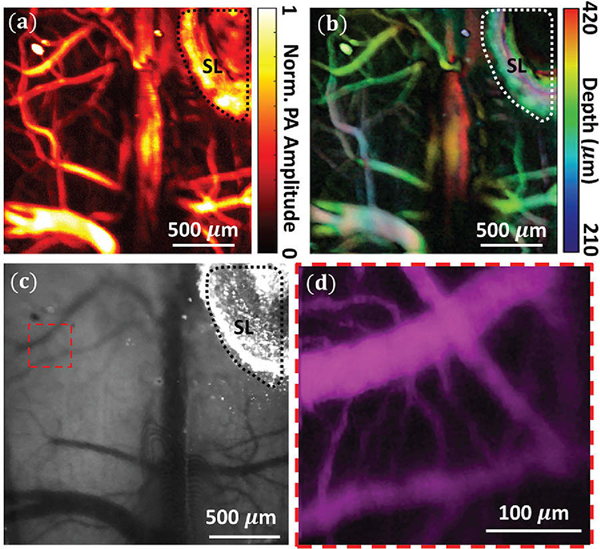

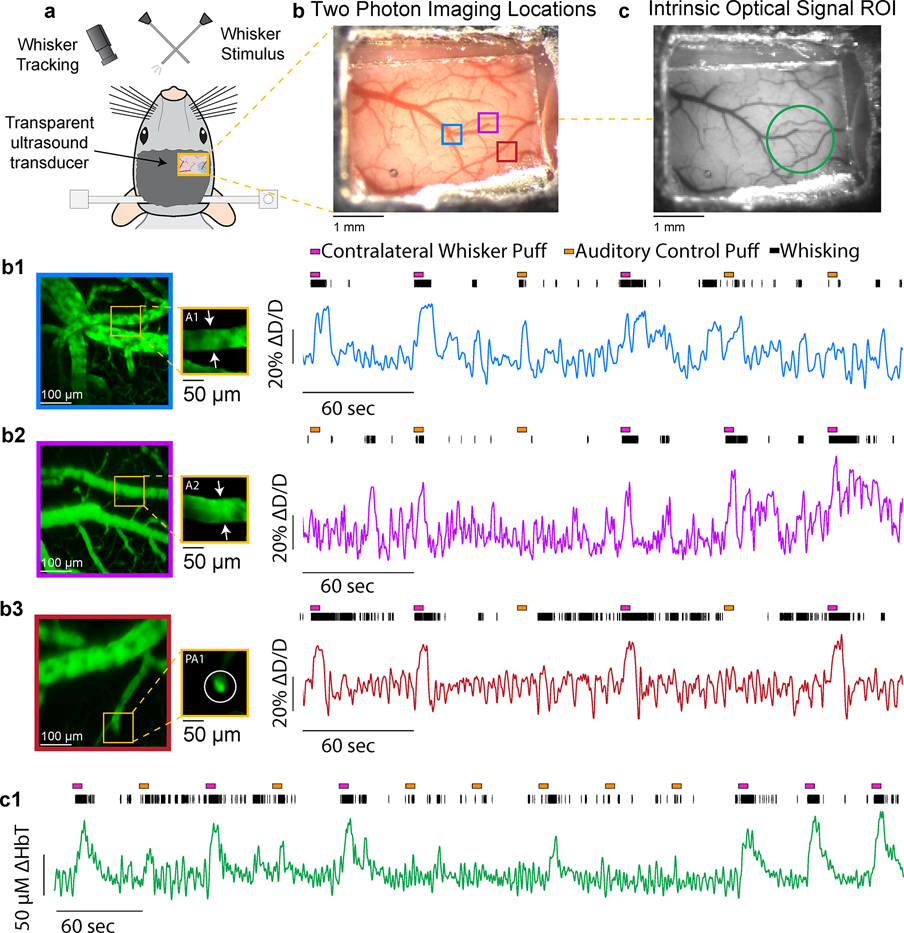

Recently, TUTs based on piezoelectric active element in particular have gained significant interest from multiple groups in photoacoustic and ultrasound community due to their versality and cost effectiveness 170–176. For example, Chen et al. 177 used LiNbO3 based TUT to image chicken embryo vasculature as well as for melanoma detection. The OR-PAM setups utilizing these TUTs have been shown to exhibit capillary level resolution71 and are therefore well suited for microcirculation imaging. In conventional optical neuroimaging using techniques such as two photon microscopy (TPM) and intrinsic optical signal imaging (IOSI)178, glass based cranial windows are often used to circumvent optical scattering induced by skull, the transparent nature of TUT makes them a viable alternation to glass cranial windows. We demonstrated this by implanting TUT (~ 1.25 mm thick) instead of the standard glass coverslip onto a polished and reinforced thinned-skull window179,180. The TUT cranial window allowed us to use three different modalities OR-PAM, TPM and IOSI to image awake mouse brain vasculature using a head restraint setup71. The results are shown in Figure 11. To further show the TUT cranial window’s viability for functional neuroimaging studies, we created another TUT cranial window located above the whisker barrel field of somatosensory cortex (Figure 12a). The surgery followed the process outlined in our previous study71 and was done in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Pennsylvania State University. Using TPM181, we measured changes in the diameter of individual pial and penetrating arterioles during volitional whisking and whisker stimulation (Figure 12b). Dilations in these arterioles during prolonged sensory stimulation showed consistent diameter increases in excess of 20% above resting baseline, consistent with previous findings178,182–185 along with 5–10% changes during volitional whisking186. We noted no difference in image quality while imaging through the TUT when compared to standard glass coverslips typically used in thinned-skull windows. When imaging the pial surface, we used comparable power levels as through a standard glass coverslip (10–20 mW), showing the TUT window is not an impediment to multiphoton imaging. We then checked changes in cortical blood volume using intrinsic optical signal imaging187, by measuring a collection of veins, arteries, and the capillary bed178,184,185,188,189. Changes in total hemoglobin measured in a region of interest above the vibrissa cortex (Figure 12c) showed large increases in cortical perfusion during both whisker stimulation and volitional behavior188,189, with the microvasculature clearly visible. Taken together, these examples demonstrate how common imaging techniques used to study the brain vasculature can be used through TUTs. Furthermore, A recent study showed the potential of TUTs potential for cell stimulation190. The ability to combine traditional optical measurements and ultrasound stimulation opens several avenues for new questions to be explored.

Figure 11.

(a) Photoacoustic maximum intensity projection image over a ~2×2 mm2 area. (b) Depth color-coded photoacoustic image ranging from 0.21–0.42 mm. (c) IOSI image of the thinned mouse skull through the TUT cranial window (d) TPM image of dashed box in (c), with a field of view of 300×300 μm2. SL: Silver Epoxy. Reprinted with permission from 71.

Figure 12.

Optical imaging through a transparent ultrasound transducer. a) Schematic of transparent transducer located above the somatosensory cortex in a head-fixed mouse. Whiskers were stimulated with puffs of air, and the whisker movement was tracked with a high-speed camera. b1) Colored squares show locations where arterioles were imaged with two-photon microscopy. b1)-3) Z-Stacks and individual diameter measurements of example pial and penetrating arterioles show clear and consistent dilation during volitional whisking and whisker stimulation. c) Grayscale image through window showing region of interest (ROI-green circle) where hemoglobin concentration changes (ΔHbT) we measured. Large increases in total hemoglobin are seen during sensory stimulation within a region of interest located above the whisker representation of the somatosensory cortex.

PAI has gone through decades of extensive system development which has propelled the community’s focus towards clinical translation studies. One direction for clinical translation has been in developing handheld probes for both photoacoustic tomography and microscopy. Handheld setups have been employed for various clinical applications including cancerous tissue, oral and skin monitoring137,138,191–195. The main limitation of handheld probes is the penetration depth which limits its application to sub-surface imaging. Therefore, to image deeper tissues with minimal invasion, photoacoustic endoscopes have also been investigated196. Various types of photoacoustic endoscopes ranging from side viewing197,198 to forward viewing167 have been demonstrated for various clinical applications such as prostarte199 and ovarian cancer studies200 as well as plaque imaging201. Lastly, challenges remain to image deep tissue at high resolution. Recent advances in machine learning and post-processing can further be leveraged by PAI to enhance resolution, improve the signal to noise ratio and pave the way for deep tissue imaging80,202–205.

5. Perspective

Photoacoustic imaging is a multiscale, multiparametric imaging technique that can provide information about the microvasculature without the use of exogenous contrast agents. Photoacoustic imaging has been demonstrated for mapping the microcirculation with clinical relevance in diverse fields such neurovascular, cardiovascular, ophthalmic and cancer research. One of the long-standing challenges for photoacoustic imaging is the need to integrate it with other imaging modalities based on different contrasts such as scattering and fluorescence. Optically transparent ultrasound transducers offer a potential solution as they can simplify the imaging head considerably and allow for seamless integration with other imaging modalities, thereby opening avenues for powerful, complementary multimodal imaging platforms.

List of Abbreviations

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- BOLD fMRI

Blood oxygen-level dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging

- HbO2

Oxygenated hemoglobin

- HbR

Deoxygenated hemoglobin

- X-Ray CT

X-Ray computed tomography

- fUS

Functional ultrasound

- OCT

optical coherence tomography

- MPM

Multiphoton imaging

- PAI

Photoacoustic imaging

- MIP

Maximum intensity projection

- PAT

Photoacoustic tomography

- MSOT

Multispectral optoacoustic tomography

- AR-PAM

Acoustic resolution photoacoustic microscopy

- OR-PAM

Optical resolution photoacoustic microscopy

- PARS

Photoacoustic remote sensing

- MbO2

Oxy-myoglobin

- MbR

Reduced myoglobin

- TUT

Transparent ultrasound transducer

- PACT

Photoacoustic computed tomography

- TPM

Two photon microscopy

- IOSI

Intrinsic optical signal imaging

- LiNbO3

Lithium niobate

- PMN-PT

Lead magnesium niobate-lead titanate

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Ethics approval statement

All animal procedure were carried out in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at Pennsylvania State University.

Data availability statement

Not applicable

References

- 1.Silverthorn DU Human Physiology. (Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuma RF, Duran WN & Ley K Microcirculation. (Academic Press, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Popel AS & Johnson PC Microcirculation and Hemorheology. Annu Rev Fluid Mech 37, 43–69 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanoore Edul VS et al. Microcirculation alterations in severe COVID-19 pneumonia. Journal of Critical Care 61, 73–75 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Edelman BJ & Macé E Functional ultrasound brain imaging: Bridging networks, neurons, and behavior. Current Opinion in Biomedical Engineering 18, 100286 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baran U, Choi WJ & Wang RK Potential use of OCT-based microangiography in clinical dermatology. Skin Research and Technology 22, 238–246 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akbari N, Rebec MR, Xia F, Xia F & Xu C Imaging deeper than the transport mean free path with multiphoton microscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express, BOE 13, 452–463 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toi M et al. Visualization of tumor-related blood vessels in human breast by photoacoustic imaging system with a hemispherical detector array. Sci Rep 7, 41970 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moothanchery M, Sharma A, Periyasamy V & Pramanik M High resolution and deep tissue imaging using a near infrared acoustic resolution photoacoustic microscopy. in Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing 2018 vol. 10494 553–558 (SPIE, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hai P, Yao J, Maslov KI, Zhou Y & Wang LV Near-infrared optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. Opt. Lett., OL 39, 5192–5195 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Logothetis NK, Pauls J, Augath M, Trinath T & Oeltermann A Neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the fMRI signal. Nature 412, 150–157 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Logothetis NK What we can do and what we cannot do with fMRI. Nature 453, 869–878 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bar-Shalom R, Valdivia AY & Blaufox MD PET imaging in oncology. Seminars in Nuclear Medicine 30, 150–185 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Basu S et al. Fundamentals of PET and PET/CT imaging. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1228, 1–18 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiriyannaiah HP X-ray computed tomography for medical imaging. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 14, 42–59 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Villarraga-Gómez H, Herazo EL & Smith ST X-ray computed tomography: from medical imaging to dimensional metrology. Precision Engineering 60, 544–569 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li L, Yao J & Wang LV Photoacoustic Tomography of Neural Systems. in Neural Engineering (ed. He B.) 349–378 (Springer International Publishing, 2020). doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-43395-6_12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deffieux T, Demene C, Pernot M & Tanter M Functional ultrasound neuroimaging: a review of the preclinical and clinical state of the art. Current Opinion in Neurobiology 50, 128–135 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mace E et al. Functional ultrasound imaging of the brain: theory and basic principles. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control 60, 492–506 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanter M & Fink M Ultrafast imaging in biomedical ultrasound. IEEE Transactions on Ultrasonics, Ferroelectrics, and Frequency Control 61, 102–119 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang B, Lu R, Zhang Q & Yao X Breaking diffraction limit of lateral resolution in optical coherence tomography. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery 3, 24348–24248 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Larson AM Multiphoton microscopy. Nature Photon 5, 1–1 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yao J & Wang LV Photoacoustic microscopy. Laser & Photonics Reviews 7, 758–778 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alford R et al. Toxicity of Organic Fluorophores Used in Molecular Imaging: Literature Review. Mol Imaging 8, 7290.2009.00031 (2009). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi JW & Moon W-J Gadolinium Deposition in the Brain: Current Updates. Korean J Radiol 20, 134–147 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cavaco M et al. To What Extent Do Fluorophores Bias the Biological Activity of Peptides? A Practical Approach Using Membrane-Active Peptides as Models. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 8, 1059 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yao J et al. High-speed Label-free Functional Photoacoustic Microscopy of Mouse Brain in Action. Nat Methods 12, 407–410 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang HF, Maslov K, Stoica G & Wang LV Functional photoacoustic microscopy for high-resolution and noninvasive in vivo imaging. Nat Biotechnol 24, 848–851 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu M & Wang LV Photoacoustic imaging in biomedicine. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 23. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beard P Biomedical photoacoustic imaging. Interface Focus 1, 602–631 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maslov K, Zhang HF, Hu S & Wang LV Optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy for in vivo imaging of single capillaries. Opt. Lett., OL 33, 929–931 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang LV & Hu S Photoacoustic Tomography: In Vivo Imaging from Organelles to Organs. Science 335, 1458–1462 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bell AG On the production and reproduction of sound by light. American Journal of Science s3–20, 305–324 (1880). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L, Maslov KI, Xing W, Garcia-Uribe A & Wang LV Video-rate functional photoacoustic microscopy at depths. JBO 17, 106007 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yao J et al. Noninvasive photoacoustic computed tomography of mouse brain metabolism in vivo. NeuroImage 64, 257–266 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agrawal S et al. Photoacoustic Imaging of Human Vasculature Using LED versus Laser Illumination: A Comparison Study on Tissue Phantoms and In Vivo Humans. Sensors 21, 424 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hsu H-C, Wang L & Wang LV In vivo photoacoustic microscopy of human cuticle microvasculature with single-cell resolution. JBO 21, 056004 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Favazza CP, Wang LV, Jassim OW & Cornelius LA In vivo photoacoustic microscopy of human cutaneous microvasculature and a nevus. JBO 16, 016015 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhou Y et al. Optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy with ultrafast dual-wavelength excitation. Journal of Biophotonics 13, e201960229 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xia J, Yao J & Wang LV Photoacoustic tomography: principles and advances. Electromagn Waves (Camb) 147, 1–22 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Diot G et al. Multispectral Optoacoustic Tomography (MSOT) of Human Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 23, 6912–6922 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park S, Lee C, Kim J & Kim C Acoustic resolution photoacoustic microscopy. Biomed. Eng. Lett. 4, 213–222 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu S, Maslov K & Wang LV Noninvasive label-free imaging of microhemodynamics by optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. Opt. Express, OE 17, 7688–7693 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu S, Maslov K & Wang LV Second-generation optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy with improved sensitivity and speed. Opt. Lett., OL 36, 1134–1136 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cai D, Li Z & Chen S-L In vivo deconvolution acoustic-resolution photoacoustic microscopy in three dimensions. Biomed. Opt. Express, BOE 7, 369–380 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang C et al. Reflection-mode submicron-resolution photoacoustic microscopy in vivo. in Biomedical Optics and 3-D Imaging (2012), paper BSu3A.42 BSu3A.42 (Optical Society of America, 2012). doi: 10.1364/BIOMED.2012.BSu3A.42. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hajireza P, Shi W, Bell K, Paproski RJ & Zemp RJ Non-interferometric photoacoustic remote sensing microscopy. Light Sci Appl 6, e16278–e16278 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shi J, Tang Y & Yao J Advances in super-resolution photoacoustic imaging. Quant Imaging Med Surg 8, 724–732 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yao J & Wang LV Sensitivity of photoacoustic microscopy. Photoacoustics 2, 87–101 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Danielli A, Favazza CP, Maslov K & Wang LV Single-wavelength functional photoacoustic microscopy in biological tissue. Opt Lett 36, 769–771 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tzoumas S et al. Eigenspectra optoacoustic tomography achieves quantitative blood oxygenation imaging deep in tissues. Nat Commun 7, 12121 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maximum Entropy Based Non-Negative Optoacoustic Tomographic Image Reconstruction | IEEE Journals & Magazine; | IEEE Xplore. https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/8611130?casa_token=x0J2A3Gm-_kAAAAA:sC0KRTxAPmDu1R7lyBFPeSNXogYECyrfHq-kLSA4DYgVbVpE4sJDRSwKC3BEQSrSZkjpF3xOTLI. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van den Berg PJ, Daoudi K & Steenbergen W Review of photoacoustic flow imaging: its current state and its promises. Photoacoustics 3, 89–99 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yao J, Maslov KI, Shi Y, Taber LA & Wang LV In vivo photoacoustic imaging of transverse blood flow by using Doppler broadening of bandwidth. Opt. Lett., OL 35, 1419–1421 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yao J, Maslov KI, Zhang Y, Xia Y & Wang LV Label-free oxygen-metabolic photoacoustic microscopy in vivo. JBO 16, 076003 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nicholson C Diffusion and related transport mechanisms in brain tissue. Rep. Prog. Phys. 64, 815–884 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsai PS et al. Correlations of Neuronal and Microvascular Densities in Murine Cortex Revealed by Direct Counting and Colocalization of Nuclei and Vessels. J. Neurosci. 29, 14553–14570 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Erdem Ö, Ince C, Tibboel D & Kuiper JW Assessing the Microcirculation With Handheld Vital Microscopy in Critically Ill Neonates and Children: Evolution of the Technique and Its Potential for Critical Care. Frontiers in Pediatrics 7, 273 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaplan L, Chow BW & Gu C Neuronal regulation of the blood–brain barrier and neurovascular coupling. Nat Rev Neurosci 21, 416–432 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Abbott NJ, Patabendige AAK, Dolman DEM, Yusof SR & Begley DJ Structure and function of the blood–brain barrier. Neurobiology of Disease 37, 13–25 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kolinko Y, Krakorova K, Cendelin J, Tonar Z & Kralickova M Microcirculation of the brain: morphological assessment in degenerative diseases and restoration processes. Reviews in the Neurosciences 26, 75–93 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De La Torre JC Critically Attained Threshold of Cerebral Hypoperfusion: Can It Cause Alzheimer’s Disease? Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 903, 424–436 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Na S et al. Massively parallel functional photoacoustic computed tomography of the human brain. Nat Biomed Eng 1–9 (2021) doi: 10.1038/s41551-021-00735-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yao J & Wang LV Photoacoustic brain imaging: from microscopic to macroscopic scales. NPh 1, 011003 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang HK et al. Listening to membrane potential: photoacoustic voltage-sensitive dye recording. JBO 22, 045006 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu Q, Wang X & Nie L Optical recording of brain functions based on voltage-sensitive dyes. Chinese Chemical Letters 32, 1879–1887 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hu S, Maslov KI, Tsytsarev V & Wang LV Functional transcranial brain imaging by optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. JBO 14, 040503 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang X et al. Noninvasive laser-induced photoacoustic tomography for structural and functional in vivo imaging of the brain. Nat Biotechnol 21, 803–806 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang X, Pang Y, Ku G, Stoica G & Wang LV Three-dimensional laser-induced photoacoustic tomography of mouse brain with the skin and skull intact. Opt. Lett., OL 28, 1739–1741 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Liang B et al. Impacts of the murine skull on high-frequency transcranial photoacoustic brain imaging. Journal of Biophotonics 12, e201800466 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mirg S et al. Awake mouse brain photoacoustic and optical imaging through a transparent ultrasound cranial window. Opt. Lett., OL 47, 1121–1124 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cao R et al. Functional and oxygen-metabolic photoacoustic microscopy of the awake mouse brain. NeuroImage 150, 77–87 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chen Q, Xie H & Xi L Wearable optical resolution photoacoustic microscopy. Journal of Biophotonics 12, e201900066 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Estrada H et al. Virtual craniotomy for high-resolution optoacoustic brain microscopy. Sci Rep 8, 1459 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mohammadi L et al. Skull acoustic aberration correction in photoacoustic microscopy using a vector space similarity model: a proof-of-concept simulation study. Biomed. Opt. Express, BOE 11, 5542–5556 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gao Y-R et al. Time to wake up: Studying neurovascular coupling and brain-wide circuit function in the un-anesthetized animal. NeuroImage 153, 382–398 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Taruttis A, Claussen J, Razansky D & Ntziachristos V Motion clustering for deblurring multispectral optoacoustic tomography images of the mouse heart. JBO 17, 016009 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhao H et al. Motion Correction in Optical Resolution Photoacoustic Microscopy. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 38, 2139–2150 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen X, Qi W & Xi L Deep-learning-based motion-correction algorithm in optical resolution photoacoustic microscopy. Visual Computing for Industry, Biomedicine, and Art 2, 12 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Manwar R, Zafar M & Xu Q Signal and Image Processing in Biomedical Photoacoustic Imaging: A Review. Optics 2, 1–24 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cardiovascular-diseases-(cvds).

- 82.Slovinski AP, Hajjar LA & Ince C Microcirculation in Cardiovascular Diseases. Journal of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia 33, 3458–3468 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.De Backer D, Creteur J, Preiser J-C, Dubois M-J & Vincent J-L Microvascular Blood Flow Is Altered in Patients with Sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166, 98–104 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.De Backer D, Ortiz JA & Salgado D Coupling microcirculation to systemic hemodynamics. Current Opinion in Critical Care 16, 250–254 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Spanos A, Jhanji S, Vivian-Smith A, Harris T & Pearse RM EARLY MICROVASCULAR CHANGES IN SEPSIS AND SEVERE SEPSIS. Shock 33, 387–391 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ince C Hemodynamic coherence and the rationale for monitoring the microcirculation. Critical Care 19, S8 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ince C et al. Second consensus on the assessment of sublingual microcirculation in critically ill patients: results from a task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 44, 281–299 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hammes H-P, Feng Y, Pfister F & Brownlee M Diabetic Retinopathy: Targeting Vasoregression. Diabetes 60, 9–16 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fowler MJ Microvascular and Macrovascular Complications of Diabetes. Clinical Diabetes 26, 77–82 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hinkel R et al. Diabetes Mellitus–Induced Microvascular Destabilization in the Myocardium. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 69, 131–143 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yang D-Y et al. “Light in and Sound Out”: Review of Photoacoustic Imaging in Cardiovascular Medicine. IEEE Access 7, 38890–38901 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wu M, FW van der Steen A, Regar E & van Soest G Emerging Technology Update Intravascular Photoacoustic Imaging of Vulnerable Atherosclerotic Plaque. Interv Cardiol 11, 120–123 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang B et al. Detection of lipid in atherosclerotic vessels using ultrasound-guided spectroscopic intravascular photoacoustic imaging. Opt. Express, OE 18, 4889–4897 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Karpiouk AB et al. Combined ultrasound and photoacoustic imaging to detect and stage deep vein thrombosis: phantom and ex vivo studies. JBO 13, 054061 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tang Y et al. Deep thrombosis characterization using photoacoustic imaging with intravascular light delivery. Biomed. Eng. Lett. (2022) doi: 10.1007/s13534-022-00216-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Iskander-Rizk S et al. Real-time photoacoustic assessment of radiofrequency ablation lesion formation in the left atrium. Photoacoustics 16, 100150 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lv J et al. Hemispherical photoacoustic imaging of myocardial infarction: in vivo detection and monitoring. Eur Radiol 28, 2176–2183 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lin H-CA et al. Ultrafast Volumetric Optoacoustic Imaging of Whole Isolated Beating Mouse Heart. Sci Rep 8, 14132 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zemp RJ, Song L, Bitton R, Shung KK & Wang LV Realtime Photoacoustic Microscopy of Murine Cardiovascular Dynamics. Opt. Express, OE 16, 18551–18556 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Salvi P et al. Increase in slow-wave vasomotion by hypoxia and ischemia in lowlanders and highlanders. Journal of Applied Physiology 125, 780–789 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chen Q, Jin T, Qi W, Mo X & Xi L Label-free photoacoustic imaging of the cardio-cerebrovascular development in the embryonic zebrafish. Biomed. Opt. Express, BOE 8, 2359–2367 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Favazza CP, Wang LV & Cornelius LA In vivo functional photoacoustic microscopy of cutaneous microvasculature in human skin. JBO 16, 026004 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ma H, Cheng Z, Wang Z, Zhang W & Yang S Switchable optical and acoustic resolution photoacoustic dermoscope dedicated into in vivo biopsy-like of human skin. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 073703 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 104.Merčep E, Deán-Ben XL & Razansky D Imaging of blood flow and oxygen state with a multi-segment optoacoustic ultrasound array. Photoacoustics 10, 48–53 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Merčep E, Deán-Ben XL & Razansky D Combined Pulse-Echo Ultrasound and Multispectral Optoacoustic Tomography With a Multi-Segment Detector Array. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 36, 2129–2137 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Multispectral optoacoustic tomography of systemic sclerosis - Masthoff - 2018. - Journal of Biophotonics - Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jbio.201800155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yang H et al. Soft ultrasound priors in optoacoustic reconstruction: Improving clinical vascular imaging. Photoacoustics 19, 100172 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sciences KRSE, Biomedical. The Eye: The Physiology of Human Perception. (The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 109.Herdade AS et al. Effects of Diabetes on Microcirculation and Leukostasis in Retinal and Non-Ocular Tissues: Implications for Diabetic Retinopathy. Biomolecules 10, E1583 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hellström A, Smith LE & Dammann O Retinopathy of prematurity. The Lancet 382, 1445–1457 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Jiang H et al. Impaired retinal microcirculation in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 22, 1812–1820 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Shi C, Jiang H, Gameiro GR & Wang J Microcirculation in the conjunctiva and retina in healthy subjects. Eye and Vision 6, 11 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wei Y et al. Age-Related Alterations in the Retinal Microvasculature, Microcirculation, and Microstructure. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science 58, 3804–3817 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chen W et al. Altered Bulbar Conjunctival Microcirculation in Response to Contact Lens Wear. Eye & Contact Lens 43, 95–99 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Organisciak DT & Vaughan DK Retinal light damage: Mechanisms and protection. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research 29, 113–134 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Delori FC, Webb RH & Sliney DH Maximum permissible exposures for ocular safety (ANSI 2000), with emphasis on ophthalmic devices. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A, JOSAA 24, 1250–1265 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Liu W & Zhang HF Photoacoustic imaging of the eye: A mini review. Photoacoustics 4, 112–123 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Silverman RH et al. High-Resolution Photoacoustic Imaging of Ocular Tissues. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology 36, 733–742 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhang X M.d, C. A. P., Jiao S & Zhang HF Simultaneous in vivo imaging of melanin and lipofuscin in the retina with photoacoustic ophthalmoscopy and autofluorescence imaging. JBO 16, 080504 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Shu X, Li H, Dong B, Sun C & Zhang HF Quantifying melanin concentration in retinal pigment epithelium using broadband photoacoustic microscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express, BOE 8, 2851–2865 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Liu W et al. In vivo corneal neovascularization imaging by optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. Photoacoustics 2, 81–86 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Hu S, Rao B, Maslov K & Wang LV Label-free photoacoustic ophthalmic angiography. Opt. Lett., OL 35, 1–3 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zerda A de la et al. Photoacoustic ocular imaging. Opt. Lett., OL 35, 270–272 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wu N, Ye S, Ren Q & Li C High-resolution dual-modality photoacoustic ocular imaging. Opt. Lett., OL 39, 2451–2454 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hosseinaee Z et al. Functional and structural ophthalmic imaging using noncontact multimodal photoacoustic remote sensing microscopy and optical coherence tomography. Sci Rep 11, 11466 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zhang W et al. High-resolution, in vivo multimodal photoacoustic microscopy, optical coherence tomography, and fluorescence microscopy imaging of rabbit retinal neovascularization. Light Sci Appl 7, 103 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhang W, Li Y, Nguyen VP M.d, Y. M. P. & Wang X Integrated simultaneous multimodality photoacoustic microscopy, optical coherence tomography, and fluorescence microscopy for rabbit ocular imaging in vivo and safety evaluation. in Ophthalmic Technologies XXXI vol. 11623 116230O (SPIE, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 128.Nguyen VP et al. Contrast Agent Enhanced Multimodal Photoacoustic Microscopy and Optical Coherence Tomography for Imaging of Rabbit Choroidal and Retinal Vessels in vivo. Sci Rep 9, 5945 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Dadkhah A, Zhou J, Yeasmin N & Jiao S Integrated multimodal photoacoustic microscopy with OCT- guided dynamic focusing. Biomed. Opt. Express, BOE 10, 137–150 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Sung H et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians 71, 209–249 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Cancer. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer.

- 132.Geiger TR & Peeper DS Metastasis mechanisms. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 1796, 293–308 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Nishida N, Yano H, Nishida T, Kamura T & Kojiro M Angiogenesis in Cancer. Vasc Health Risk Manag 2, 213–219 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Carmeliet P & Jain RK Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature 407, 249–257 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Lewis MR Looking Through the Vascular Normalization Window: Timing Antiangiogenic Treatment and Chemotherapy with 99mTc-Annexin A5. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 52, 1670–1672 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Höckel M & Vaupel P Tumor Hypoxia: Definitions and Current Clinical, Biologic, and Molecular Aspects. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute 93, 266–276 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Zhou Y, Xing W, Maslov KI, Cornelius LA & Wang LV Handheld photoacoustic microscopy to detect melanoma depth in vivo. Opt. Lett., OL 39, 4731–4734 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Zhou Y et al. Noninvasive Determination of Melanoma Depth using a Handheld Photoacoustic Probe. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 137, 1370–1372 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Wang Y, Xu D, Yang S & Xing D Toward in vivo biopsy of melanoma based on photoacoustic and ultrasound dual imaging with an integrated detector. Biomed. Opt. Express, BOE 7, 279–286 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Ku G, Wang X, Xie X, Stoica G & Wang LV Imaging of tumor angiogenesis in rat brains in vivo by photoacoustic tomography. Appl. Opt., AO 44, 770–775 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Lao Y, Xing D, Yang S & Xiang L Noninvasive photoacoustic imaging of the developing vasculature during early tumor growth. Phys. Med. Biol. 53, 4203–4212 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Mallidi S, Luke GP & Emelianov S Photoacoustic imaging in cancer detection, diagnosis, and treatment guidance. Trends in Biotechnology 29, 213–221 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Valluru KS & Willmann JK Clinical photoacoustic imaging of cancer. Ultrasonography 35, 267–280 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Mehrmohammadi M, Joon Yoon S, Yeager D & Emelianov Y, S. Photoacoustic Imaging for Cancer Detection and Staging. Current Molecular Imaging 2, 89–105 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Laufer JG et al. In vivo preclinical photoacoustic imaging of tumor vasculature development and therapy. JBO 17, 056016 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Zhou H-C et al. Optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy for monitoring vascular normalization during anti-angiogenic therapy. Photoacoustics 15, 100143 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Lin R et al. Longitudinal label-free optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy of tumor angiogenesis in vivo. Quantitative Imaging in Medicine and Surgery 5, 239–229 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Liu C, Chen J, Zhang Y, Zhu J & Wang L Five-wavelength optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy of blood and lymphatic vessels. AP 3, 016002 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 149.Bi R et al. Photoacoustic microscopy for evaluating combretastatin A4 phosphate induced vascular disruption in orthotopic glioma. Journal of Biophotonics 11, e201700327 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Jain RK Normalization of Tumor Vasculature: An Emerging Concept in Antiangiogenic Therapy. Science 307, 58–62 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Gujrati V, Mishra A & Ntziachristos V Molecular imaging probes for multi-spectral optoacoustic tomography. Chemical Communications 53, 4653–4672 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Upputuri PK & Pramanik M Recent advances in photoacoustic contrast agents for in vivo imaging. WIREs Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 12, e1618 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Senarathna J et al. A miniature multi-contrast microscope for functional imaging in freely behaving animals. Nat Commun 10, 99 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Song W et al. Fully integrated reflection-mode photoacoustic, two-photon and second harmonic generation microscopy in vivo. Sci Rep 6, 32240 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Rebolleda G et al. OCT: New perspectives in neuro-ophthalmology. Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology 29, 9–25 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Liu X et al. Optical coherence photoacoustic microscopy for in vivo multimodal retinal imaging. Opt. Lett., OL 40, 1370–1373 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Liu T, Wei Q, Wang J, Jiao S & Zhang HF Combined photoacoustic microscopy and optical coherence tomography can measure metabolic rate of oxygen. Biomed. Opt. Express, BOE 2, 1359–1365 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Kolkman RGM, Brands PJ, Steenbergen W & Leeuwen T. G. C. van. Real-time in vivo photoacoustic and ultrasound imaging. JBO 13, 050510 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Kim J et al. Programmable Real-time Clinical Photoacoustic and Ultrasound Imaging System. Sci Rep 6, 35137 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Li Y et al. High-Speed Integrated Endoscopic Photoacoustic and Ultrasound Imaging System. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 25, 1–5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Pang Z et al. Multi-modality photoacoustic/ultrasound imaging based on a commercial ultrasound platform. Opt. Lett., OL 46, 4382–4385 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Lee C et al. Combined photoacoustic and optical coherence tomography using a single near-infrared supercontinuum laser source. Appl. Opt., AO 52, 1824–1828 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Chen H et al. A High Sensitivity Transparent Ultrasound Transducer Based on PMN-PT for Ultrasound and Photoacoustic Imaging. IEEE Sensors Letters 5, 1–4 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Wissmeyer G, Pleitez MA, Rosenthal A & Ntziachristos V Looking at sound: optoacoustics with all-optical ultrasound detection. Light Sci Appl 7, 53 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Dong B, Sun C & Zhang HF Optical Detection of Ultrasound in Photoacoustic Imaging. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 64, 4–15 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Zhang E, Laufer J & Beard P Backward-mode multiwavelength photoacoustic scanner using a planar Fabry-Perot polymer film ultrasound sensor for high-resolution three-dimensional imaging of biological tissues. Appl. Opt., AO 47, 561–577 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Ansari R, Zhang EZ, Desjardins AE & Beard PC All-optical forward-viewing photoacoustic probe for high-resolution 3D endoscopy. Light Sci Appl 7, 75 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Dangi A, Agrawal S & Kothapalli S-R Lithium niobate-based transparent ultrasound transducers for photoacoustic imaging. Opt. Lett., OL 44, 5326–5329 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Chen H et al. Transparent ultrasound transducers for multiscale photoacoustic imaging. in Photons Plus Ultrasound: Imaging and Sensing 2021 vol. 11642 142–149 (SPIE, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 170.Ren D, Sun Y, Shi J & Chen R A Review of Transparent Sensors for Photoacoustic Imaging Applications. Photonics 8, 324 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 171.Liao T et al. Centimeter-scale wide-field-of-view laser-scanning photoacoustic microscopy for subcutaneous microvasculature in vivo. Biomed. Opt. Express, BOE 12, 2996–3007 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Park J et al. Quadruple ultrasound, photoacoustic, optical coherence, and fluorescence fusion imaging with a transparent ultrasound transducer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 118, e1920879118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Park B et al. A photoacoustic finder fully integrated with a solid-state dye laser and transparent ultrasound transducer. Photoacoustics 23, 100290 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Park S, Kang S & Chang JH Optically Transparent Focused Transducers for Combined Photoacoustic and Ultrasound Microscopy. J. Med. Biol. Eng. 40, 707–718 (2020). [Google Scholar]