Abstract

Objective

To explore recurrent themes in diaries kept by intensive care unit (ICU) staff during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Design

Qualitative study.

Setting

Two ICUs in a tertiary level hospital (Milan, Italy) from January to December 2021.

Methods

ICU staff members wrote a digital diary while caring for adult patients hospitalized in the intensive care unit for >48 hours. A thematic analysis was performed.

Findings

Diary entries described what happened and expressed emotions. Thematic analysis of 518 entries gleaned from 48 diaries identified four themes (plus ten subthemes): Presenting (Places and people; Diary project), Intensive Care Unit Stay (Clinical events; What the patient does; Patient support), Outside the Hospital (Family and topical events; The weather), Feelings and Thoughts (Encouragement and wishes; Farewell; Considerations).

Conclusion

The themes were similar to published findings. They offer insight into care in an intensive care unit during a pandemic, with scarce resources and no family visitors permitted, reflecting on the patient as a person and on daily care. The staff wrote farewell entries to dying patients even though no one would read them.

Implications for clinical practice

The implementation of digital diaries kept by intensive care unit staff is feasible even during the COVID-19 pandemic. Diaries kept by staff can provide a tool to humanize critical care. Staff can improve their work by reflecting on diary records.

Keywords: Diary, Digital diary, COVID-19, Humanizing, Intensive care unit, Qualitative research, Thematic analysis

Introduction

Intensive care unit (ICU) diaries are gaining widespread acceptance worldwide (Garrouste-Orgeas et al., 2014). The concept of creating and maintaining a diary were born in Northern Europe, initially involved nurses in writing a narrative of what was happening to their critically ill unconscious patients. Diary writing was later extended to include physicians, patients’ family members, and patients themselves (Bergbom et al., 1999, Nortvedt, 1987).

Diary entries directly address the patient in an empathetic and reflective style using everyday language. They document a patient’s current clinical status and describe situations and surroundings (Egerod and Christensen, 2010) in which the patient might find recognition (Pattison et al., 2019). Diary entries are not a clinical report minus the medical terms but rather a collection of notes that describe the patient's ICU stay from the writer's point of view (Egerod and Christensen, 2010). Furthermore, diaries are low-cost tools: either a paper notebook kept at the bedside or a digital record that can be accessed by other devices or journaling applications (Beg et al., 2016). Sometimes photos or pictures are attached to the diary (Åkerman et al., 2013, Gawronski et al., 2022).

Patients and family members generally welcome the use of diaries (Nielsen et al., 2019) because they enable patients to evaluate their recovery and to tell their family about their experience in the ICU (Egerod et al., 2011).

The objective of keeping a diary is to help ICU patients recover during and after critical illness; reading diary entries can help patients better understand their perceptions and orientate factual memory (Pattison et al., 2019). For many, ICU admission is a life-disrupting event: patients may experience physical, cognitive, psychological, and social problems after ICU discharge; their family members may suffer anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress (Davidson et al., 2012, Parker et al., 2013). These issues suggest an increase in psychological distress following changes in ICU visiting policies due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Mistraletti et al., 2021). Controversy surrounds the efficacy of ICU diaries in reducing PTSD, anxiety, and depression in patients and family members (Barreto et al., 2019, Schofield et al., 2021). Finally, diary writing provides an opportunity for the whole ICU team, especially for nursing staff, to personalize care of ICU patients (Strandberg et al., 2018).

Aim

With this study we wanted to explore recurrent themes in diaries, kept by ICU staff during the coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Methods

Design, setting, participants

For this qualitative study we applied thematic analysis to investigate ICU staff diaries (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The study was conducted at two ICUs (26 beds) at the Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico (Milan, Italy), a tertiary hospital operated as a coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) hub during the pandemic. The medical and nursing staff of the two ICUs were members of the same working group of physicians and nurses with similar levels of competence and experience in both ICUs. The multidisciplinary research group was made up of six critical care nurses (two with a bachelor degree, three with a master degree, and one with a doctor of philosophy degree) and two intensivist physicians (a consultant and a full professor); a psychologist was involved in the thematic analysis for methodological support. The researcher group was made up of four women and four men. The researchers held different positions in the ICUs (nurse, physician, researcher, nurse manager, medical director); seven had experience in research.

The ICU staff received training in diary writing and were informed about the study purpose and procedures in face-to-face and remote meetings. The presentations were disseminated via booklets left in the ICUs and sent by email.

Because of changes in the visiting policies for family members during the COVID-19 pandemic (Multidisciplinary Working Group “ComuniCovid” [Italian Society of Anesthesia and Intensive Care (SIAARTI), Italian Association of Critical Care Nurses (Aniarti), Italian Society of Emergency Medicine (SIMEU), and Italian Society of Palliative Care (SICP)], 2020), the diaries were created and maintained by the ICU staff. During their work shift the ICU staff wrote notes to their patients; they could either sign the notes or leave them anonymous. The option of remaining anonymous protected the writer’s identity and was conceived as a way to motivate participation in the study because not all ICU staff wanted their entries to be read by coworkers. The staff were informed that the entries would be analyzed later for research purposes. The staff could attend to the patients for whom the diary was started regardless of study participation. The diaries were addressed to adult patients hospitalized in the ICU for at least 48 hours and who were able to understand Italian. Exclusion criteria were: patient age <18 years, psychiatric disorder, dementia-type illness, conditions leading to death or intention to withdraw life support within 72 hours after ICU admission.

Data collection

From January to December 2021 the diaries were created and maintained in digital format, as a specific section within the clinical electronic records (Digistat, United Medical Software). At ICU discharge the diary notes were printed, bound with a colored journal cover with the patient's name printed on it. The first page of the diary described the present project. All notes, including the anonymous ones, included the writer’s job title, the entry date and time. Patient demographics, clinical characteristics, and information on diary management and writing were entered in a database accessible only to the study researchers. To ensure quality assurance, the diaries were read by two nurses (research team members) before being given to the patients prior to discharge. These ICU nurses arranged the time for handing over the diaries, as agreed with ward colleagues and with patient’s family members, whenever possible.

Unfortunately, the initially planned follow-up was not possible due to COVID-19-related restrictions but patients could contact the researchers via hospital telephone numbers and emails for further information. Psychological support was provided all ICU patients and their family members independent of study participation. Family members of deceased patients were not given the patient’s diary.

Data analysis

All diary entries were anonymized and numbered in chronological order. Qualitative data analysis was performed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The method entails six steps: 1) familiarization with the data, i.e., data transcription, reading, and rereading, then writing down the initially selected topics; 2) systematic classification of interesting data characteristics, then assigning the data a code; 3) coding the potential topics, i.e., collection of relevant data for each potential topic; 4) checking whether the themes worked in relation to the coded extracts (level 1) and the entire dataset (level 2), then generating a thematic map of the analysis; 5) continuous analysis to refine the specifics of each theme, then generating clearer categories; 6) writing the final report with examples of notable and convincing extracts and final analysis of the selected extracts.

These steps were carried out by two independent researchers, a third author resolved any disagreement; themes were discussed and approved by the research team. The notes published here were translated from the original Italian to English by a native English speaker and professional translator. The present study was conducted according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research Recommendations (O’Brien et al., 2014).

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of our Institution (ethic approval number 997_2020). Patients gave their written informed consent to participate in the study. Participation in the study by ICU staff was voluntary. ICU staff were informed of the study aims, writing a diary meant consent to participation in the study.

Findings

A total of 49 diaries were kept, one patient declined participation in the study. The final sample was 518 entries gleaned from 48 diaries. Patients for whom an ICU diary was kept were mostly admitted for respiratory distress due to COVID-19 (34, 69.4 %); 11 patients (22.9 %) died during ICU stay (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Demographic characteristics | N = 48 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 35 (71.4%) |

| Female | 14 (28.6%) |

| Age (years) | 58 (47–67) |

| Reason for admission | |

| ARDS COVID-19 | 34 (69.4%) |

| Septic shock | 6 (12.2%) |

| ARDS other etiology | 5 (10.2%) |

| Lung transplantation | 4 (8.2%) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| ICU length of stay (days) | 20 (14–37) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation (days) | 18 (10–32) |

| Sedation (days) | 16 (9–31) |

| Prone positioning | 24 (50%) |

| Tracheotomy | 10 (20.8%) |

| ECMO | 8 (16.7%) |

| CRRT | 4 (8.3%) |

| Discharged alive from ICU | 37 (77.1%) |

Data are presented as counts (%) or median (IQR).

Abbreviations: ARDS, Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. COVID-19, Coronavirus Disease 2019. ICU, Intensive Care Unit. ECMO, Extra Corporeal Membrane Oxygenation. CRRT, Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy.

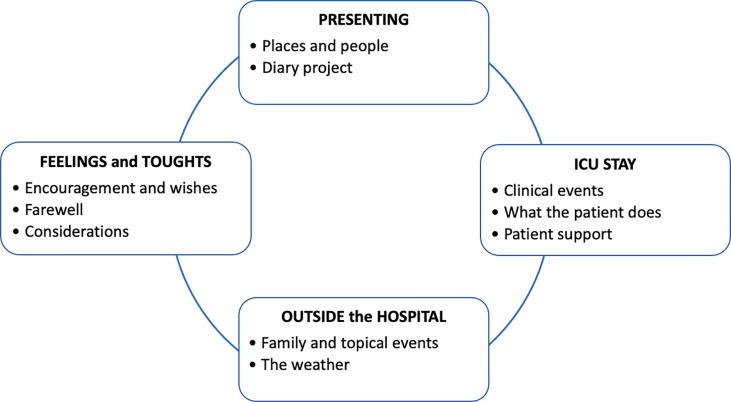

ICU diary entries were written by nurses (428/518, 82.6 %), physicians (70, 13.5 %), physiotherapists (10, 1.9 %), healthcare assistants (6, 1.2 %), and perfusionists (4, 0.8 %). Two physicians acting as consultants for the ICU (a pulmonologist and a thoracic surgeon) also wrote notes. Diary entries were written at night more often than during the afternoon or the morning shift: 230 (44.4 %), 186 (35.9 %), and 102 (19.7 %), respectively. The majority of the entries described what happened and expressed emotions using the second person singular or first person plural. Four recurrent themes and ten subthemes were identified (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Themes and subthemes identified.

Presenting

The diaries always began with an introduction of the patient to the hospital, the writer, and the ICU diary project. Sometimes they were short descriptions, sometimes they were detailed. The writers look toward a future when the patient would be well and could read the diary. This theme had two subthemes.

Places and people

The staff described the ICU where the patient was hospitalized, introduced themselves, and stated their job title. The nurses often introduced themselves to the patient as “your nurse”. For patients transferred from other hospitals, the first diary entry usually described the new hospital setting.

“Hello, Andrea, I’m your nurse and I’ll take care of you tonight. You were admitted to our intensive care unit at 8 PM after transfer from another hospital (name of the city). Now you’re in the COVID-19 intensive care unit, at Policlinico of Milan, for severe respiratory distress.” (diary 36, nurse)

Diary project

The ICU staff, usually nurses, presented the diary project to the patient and the reasons for keeping such a diary, namely, to help reconstruct the period of time spent in the ICU.

“When you read this note you’ll have the diary in your own hands, which means that your intensive care unit stay is over and that your condition has improved. I hope that the diary will help you put together what you experienced in the intensive care.” (diary 41, nurse)

ICU Stay

This theme recurred in most of the diary entries written by staff and described anything related to ICU stay. Three subthemes were identified.

Clinical events

Clinical events included particularly nursing procedures and medical events. Nursing procedures were often mentioned the first time the patient ate, moved (e.g. legs outside the bed) or transferred to a wheelchair. Body care and hygiene were often mentioned, especially if the patient was conscious and able to collaborate even minimally with the nurse. Hair washing and/or hair cutting when done were always mentioned in the notes.

“Today was the first time you could be transferred to a wheelchair and you even started to take food; those are big steps forward.” (diary 22, physiotherapist)

“This morning we asked you if we could give you a haircut; you agreed, so we shampooed your hair and shaved your beard to make you feel refreshed.” (diary 10, nurse)

Among the medical events, extubation was always described as a sign of improvement in the patient's condition and of restored ability to communicate verbally. Other notes frequently related awakening from sedation, prone position or tracheostomy.

“Today we removed the tracheotomy; now you have a tiny ‘war wound’ like you called it and you can speak again.” (diary 6, physician)

“You’re getting better. The problem you had seems to have resolved. We no longer pronated you. Now we’re gradually reducing the sedation so you can gain consciousness and we’ll take out the ventilator tube. They took you off extracorporeal circulation a couple of hours ago when you came out of the operating room. That’s good news.” (diary 27, nurse)

What the patient does

These entries described what the patient did (e.g., what she/he said, how appeared, wrote, wanted to do) alone or with the staff during ICU stay. The patient had a predominantly active role in contrast to the previous subtheme in which the patient was mostly passive.

“This afternoon we had our first video call with your wife; your children and dogs were there too. Than you watched the Music Festival on TV” (diary 6, nurse)

Patient support

These entries described the support ICU staff or family members gave the patient. Support by family members was usually reported as conversations between ICU staff and family members during telephone calls, video calls or visits.

“Your daughter calls every day to find out how you’re doing; even if you’re sleeping she wants to come and visit. On the phone today she was worried but sure that it will all be over soon.” (diary 10, physician)

Outside the Hospital

This theme concerned any events occurring outside the hospital walls. Basically, it was the passing of life regardless of a patient's illness or hospital events. Two subthemes were identified.

Family and topical events

These entries described events concerning the patient’s family members (e.g., graduations, weddings, births) or actualities (e.g., breaking news, sports games, concerts). They were events that patients would have followed if they had been well.

“You’ll be happy to know that your grandson has graduated.” (diary 35, nurse).

“Today is Easter Sunday. It’s strange being here on Easter. Let’s hope you’ll celebrate it in a nicer place next year.” (diary 9, nurse)

The weather

The weather was often described as change of seasons. The diaries covered a whole calendar year from winter to autumn and weather events. As observed through the ICU windows, the weather was described in both factual and emotional terms.

“It’s a beautiful afternoon outside; the sun is shining and there’s a scent of spring in the air.” (diary 21, nurse)

Feelings and Thoughts

These entries reported on the emotions of the ICU staff, the patients or their family or thoughts that the staff wanted to tell the patient. Three subthemes were identified.

Encouragement and wishes

There were notes of encouragement when the patient’s medical conditions worsened or the patient was readmitted to hospital. Many notes encouraged the will to fight against COVID-19. At ICU discharge, the final diary entry was often a wish for getting better.

“You kept us busy last night; you had some problems but they’re gone now. We’re here for you and we’re doing everything we can to get you out of here as soon as possible and back home. Don’t give up, we will defeat this damned virus!” (diary 11, physician)

“This afternoon you’ll be transferred to another ward because your condition has improved. Best wishes.” (diary 2, nurse)

Farewell

In the event of a patient's death, the diaries sometimes ended with a salutation by the nurse or the physician. The farewell entries often conveyed an awareness that everything possible had been done to cure the patient and that the patient had never been left alone.

“I feel very touched writing to you now; and it hurts to know that I’m doing it after your heart has stopped beating. I wanted to say ‘good-bye’ together with my coworkers who accompanied you on your treatment path. We wanted to let you know that you were never alone.” (diary 19, physician)

“People who don’t know what it’s like to work in an intensive care unit might think that because so many patients go through the unit we can’t remember them all. But I remember well, maybe not all the names but certainly the faces and the gazes.” (diary 19, nurse)

Considerations

The ICU staff reflected on what was happening to the patient and on their own work.

“You were happy that I straightened your hair; you smiled the whole time at me and my coworkers. I was glad to make you feel pretty and feminine in this difficult situation.” (diary 1, nurse)

“You experienced episodes of delirium last night; you called for your sister, who wasn’t here. It must have been a frightening experience but it was over at dawn.” (diary 11, nurse)

Discussion

The study findings are based on a thematic analysis of entries gleaned from 48 diaries kept by ICU staff over the course of a year of the COVID-19 pandemic, in which the ICU work environment and the daily care routine were profoundly affected. The recurrent themes reflect elements of the care provided from the writer’s point of view. Nurses are noted to be prolific diary keepers (Brandao Barreto et al., 2021). For this study the entire ICU staff wrote entries, whereas the patients’ family members did not because of COVID-19-related visiting restrictions (Mistraletti et al., 2021). Diary writing was done primarily during the night shift when the workload is lighter and the staff have more time for writing. Indeed, the main barrier to maintaining a diary is lack of time (Nydahl et al., 2014), which was even more limited by the greater nursing workload during the pandemic.

The themes we identified are shared by previous work (Garrouste-Orgeas et al., 2017) and used in analysis of ICU diaries (Iannuzzi et al., 2021). Comparison between the themes and the subthemes we identified and those reported in methodologically similar studies involving adult patients (Negro et al., 2022, Pattison et al., 2019, Roulin et al., 2007), which included notes written by the patients’ family members, revealed differences in the number of themes or subthemes and their categories but no substantial difference in content, regardless of COVID-19. No COVID-19-specific theme was identified because it was considered a transversal element. A Swiss study (Roulin et al., 2007) did not distinguish between the themes Presenting, ICU Stay and Outside the Hospital but rather collated them within a more general theme of “sharing the story”. A UK study (Pattison et al., 2019) differentiated between “engagement” and “encouraging” and singled out “communication” as a separate theme. An Italian study (Negro et al., 2022) classified “references to the usefulness of the diary” and “reflection on the likely death of the patient” as distinct themes, whereas we defined them as subthemes. A review of the literature on content analysis of ICU diaries identified the term “gaining understanding” as a recurrent theme along with other categories, underlining the basic objective of ICU diary writing (Strandberg et al., 2018).

The diary entries offer multiple starting points for reflection on the delivery of critical care (Egerod and Christensen, 2009): what is done and how it is done. The notes serve a dual function for the benefit of patients and their families, and for ICU staff (Brandao Barreto et al., 2021). By recounting an event or a procedure a healthcare worker documents that she or he has perceived that action as being more relevant than routine tasks and attributes it a personal meaning within the course of her or his professional duty (Ednell et al., 2017, Gjengedal et al., 2010). The healthcare worker explains a procedure in simple terms to the patient but is thinking about what is being done and is describing elements of care that go beyond the technique itself (Johansson et al., 2019).

The diary notes clearly indicated the difficulty of communicating with patients in a lowered state of consciousness or who are intubated or have a tracheotomy that impedes phonation. It was a source of frustration and discomfort for the patient and for the healthcare worker alike (Holm et al., 2020). In such situations the healthcare worker’s role is to facilitate communication between patients and their family members during visits or via video calls (Multidisciplinary Working Group “ComuniCovid” [Italian Society of Anesthesia and Intensive Care (SIAARTI), Italian Association of Critical Care Nurses (Aniarti), Italian Society of Emergency Medicine (SIMEU), and Italian Society of Palliative Care (SICP)], 2020). Extubation was always noted in the diaries, followed by the mention of joy to hear the patient’s voice and the shift from augmented alternative communication to verbal communication, the means that adults prefer.

There was also frequent mention of prone position, in which half of the patients were placed to treat severe respiratory distress (Binda et al., 2021). The notes documented that changing the position of the critically ill depended completely upon the healthcare workers. Differently, active mobilization was noted as a sign of recovery, often together with taking food by mouth. Sitting upright in bed was welcomed by patients and staff as a further sign of improvement (Liew et al., 2021) that progressed to transfer from bed, a symbol of disease, to a wheelchair to take meals.

Personal hygiene involves intimacy with the patient, particularly hair cutting and washing since they are not part of daily care but rather belong to a patient’s personal sphere into which a healthcare worker enters. Body hygiene belongs to nursing fundamental care (Palese et al., 2019) that is as essential for preventing infection as it is for give back an immobile patient his or her human dignity.

Instances of ICU delirium were also documented in which nurses play a central role in its prevention (Galazzi et al., 2021). One entry described the anxiety a patient experienced during a nighttime episode and the support that staff provided by staying with him. In this way diaries are a useful tool for explaining to patients that they need never fear being alone (Johansson et al., 2019) and for setting distorted memories right (what was experienced as hallucination) or filling memory gaps resulting from reduced consciousness (Engström et al., 2009, Pattison et al., 2019).

Involvement of the healthcare workers with their patients can be understood from the notes of salutation and best wishes for recovery after ICU discharge. Situations of end-of-life-care were also described in which the writers reflected on death, the patient’s severe condition and therapy, while ensuring that no patient will be left alone, even at death with no family members present because of COVID-19-related visiting restrictions (Galazzi et al., 2022b). A novel finding is that the ICU staff wrote farewell entries to the dying patients despite the fact that no one (patients and relatives) would ever read them. It is interesting that they wrote intimate notes to the patients but for themselves. COVID-19 placed ICU staff in a new and vulnerable context of death (Rabow et al., 2021) and diaries could be useful to realize and deal with the loss of their patients.

Intensive care is humanized to patients and family members when the patient is cared for as a unique person and when they feel cared for (Nielsen et al., 2023), in this situation the humanization was realized by the ICU staff by writing the diary. Diary writing was also a means for the healthcare workers to take time they would have devoted to the patients’ family (Floris et al., 2021) where open ICU policies were in place (Ning and Cope, 2020).

Taking time to write a diary entry addressed to a comatose or sedated patient for reading upon awakening or that the family could read after a patient’s death (Galazzi et al., 2022a) should be counted as care time (Italian National Federation of Orders of Physicians and Dentists, 2014, Italian National Federation of Orders of Nursing Professions, 2019). Diaries can provide a source for personalizing the delivery of critical care (Perier et al., 2013).

Strengths and limitations

Few studies about ICU diaries have been conducted in Italy to date. In this single-center study the diaries were written during COVID-19 pandemic, which may have overestimated or underestimated some aspects of ICU care. The number of diaries kept over the period of a year might seem small, however, the COVID-19 pandemic meant an enormous increase in ICU admissions and in workload for ICU staff. In such circumstances, time limitations necessarily impacted on diary keeping. For the same reason, not all the diaries were equal in number of entries and richness of content. Finally, the thematic analysis did not take into account the job title of the writer or the time point during the pandemic when the entries were written.

Conclusions

The identified themes and subthemes were similar to previous reports. Diary writing provided the ICU staff with a means to reflect on their daily work and on caring for the critically ill patient as a person also during the COVID-19 pandemic. Creating and maintaining a diary in ICU over the course of a year proved useful to humanize intensive care, particularly when resources became scarce, no family visitors were allowed, and regardless of whether the notes are later read by the patients or their relatives.

Funding source

This study was partially funded by Italian Ministry of Health – Current Research IRCCS.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by Ethical Committee of Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico – Milan, Italy (approval number 997_2020).

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the ICU staff for devoting time to share their thoughts and feelings with their patients and colleagues. Particular thanks are due Dr. Rita Maria Nobili for her assistance with the qualitative research methodology.

References

- Åkerman E., Ersson A., Fridlund B., Samuelson K. Preferred content and usefulness of a photodiary as described by ICU-patients—A mixed method analysis. Aust. Crit. Care. 2013;26:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2012.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto, B.B., Luz, M., Rios, M.N. de O., Lopes, A.A., Gusmao-Flores, D., 2019. The impact of intensive care unit diaries on patients’ and relatives’ outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care 23, 411. 10.1186/s13054-019-2678-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Beg M., Scruth E., Liu V. Developing a framework for implementing intensive care unit diaries: a focused review of the literature. Aust. Crit. Care. 2016;29:224–234. doi: 10.1016/j.aucc.2016.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergbom I., Svensson C., Berggren E., Kamsula M. Patients’ and relatives’ opinions and feelings about diaries kept by nurses in an intensive care unit: pilot study. Intensive Crit. care Nurs. 1999;15:185–191. doi: 10.1016/s0964-3397(99)80069-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binda F., Marelli F., Galazzi A., Pascuzzo R., Adamini I., Laquintana D. Nursing management of prone positioning in patients with COVID-19. Crit. Care Nurse. 2021;41:27–35. doi: 10.4037/ccn2020222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandao Barreto, B., Luz, M., do Amaral Lopes, S.A.V., Rosa, R.G., Gusmao-Flores, D., 2021. Exploring family members’ and health care professionals’ perceptions on ICU diaries: a systematic review and qualitative data synthesis. Intensive Care Med. 47, 737–749. 10.1007/s00134-021-06443-w. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson J., Jones C., Bienvenu O. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit. Care Med. 2012;40:618–624. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E318236EBF9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ednell A.-K., Siljegren S., Engström Å. The ICU patient diary–A nursing intervention that is complicated in its simplicity: A qualitative study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2017;40:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2016.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egerod I., Christensen D. Analysis of patient diaries in Danish ICUs: A narrative approach. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2009;25:268–277. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egerod I., Christensen D. A comparative study of ICU patient diaries vs. hospital charts. Qual. Health Res. 2010;20:1446–1456. doi: 10.1177/1049732310373558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egerod I., Christensen D., Schwartz-Nielsen K.H., Ågård A.S. Constructing the illness narrative: A grounded theory exploring patientsʼ and relativesʼ use of intensive care diaries. Crit. Care Med. 2011;39:1922–1928. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31821e89c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engström Å., Grip K., Hamrén M. Experiences of intensive care unit diaries: ‘touching a tender wound’. Nurs. Crit. Care. 2009;14:61–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2008.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floris, L., Madeddu, A., Deiana, V., Pasero, D., Terragni, P., 2021. The use of the ICU diary during the COVID-19 pandemic as a tool to enhance critically ill patient recovery. Minerva Anestesiol. 87. 10.23736/S0375-9393.20.15161-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Galazzi A., Giusti G.D., Pagnucci N., Bambi S. Assessment of delirium in adult patients in Intensive Care Unit: Italian Critical Care Nurses Best Practices. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2021;66 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galazzi A., Adamini I., Bazzano G., Cancelli L., Fridh I., Laquintana D., Lusignani M., Rasero L. Intensive care unit diaries to help bereaved family members in their grieving process: a systematic review. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2022;68 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galazzi, A., Binda, F., Gambazza, S., Cantù, F., Colombo, E., Adamini, I., Grasselli, G., Lusignani, M., Laquintana, D., Rasero, L., 2022b. The end of life of patients with COVID ‐19 in intensive care unit and the stress level on their family members: A cross‐sectional study. Nurs. Crit. Care. 10.1111/nicc.12783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Garrouste-Orgeas M., Périer A., Mouricou P., Grégoire C., Bruel C., Brochon S., Philippart F., Max A., Misset B. Writing in and reading ICU diaries: qualitative study of families’ experience in the ICU. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrouste-Orgeas M., Flahault C., Fasse L., Ruckly S., Amdjar-Badidi N., Argaud L., Badie J., Bazire A., Bige N., Boulet E., Bouadma L., Bretonnière C., Floccard B., Gaffinel A., de Forceville X., Grand H., Halidfar R., Hamzaoui O., Jourdain M., Jost P.-H., Kipnis E., Large A., Lautrette A., Lesieur O., Maxime V., Mercier E., Mira J.P., Monseau Y., Parmentier-Decrucq E., Rigaud J.-P., Rouget A., Santoli F., Simon G., Tamion F., Thieulot-Rolin N., Thirion M., Valade S., Vinatier I., Vioulac C., Bailly S., Timsit J.-F. The ICU-Diary study: prospective, multicenter comparative study of the impact of an ICU diary on the wellbeing of patients and families in French ICUs. Trials. 2017;18:542. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2283-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawronski, O., Sansone, V., Cancani, F., Di Nardo, M., Rossi, A., Gagliardi, C., De Ranieri, C., Satta, T., Dall’Oglio, I., Tiozzo, E., Alvaro, R., Raponi, M., Cecchetti, C., 2022. Implementation of paediatric intensive care unit diaries: Feasibility and opinions of parents and healthcare providers. Aust. Crit. Care. 10.1016/j.aucc.2022.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gjengedal E., Storli S.L., Holme A.N., Eskerud R.S. An act of caring – patient diaries in Norwegian intensive care units. Nurs. Crit. Care. 2010;15:176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-5153.2010.00402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm A., Viftrup A., Karlsson V., Nikolajsen L., Dreyer P. Nurses’ communication with mechanically ventilated patients in the intensive care unit: Umbrella review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2020;76:2909–2920. doi: 10.1111/jan.14524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iannuzzi L., Villa S., Vimercati S., Villa M., Pisetti C.F., Viganò G., Fumagalli R., Rona R., Lucchini A. Use of intensive care unit diary as an integrated tool in an Italian general intensive care unit. Dimens. Crit. Care Nurs. 2021;40:248–256. doi: 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Italian National Federation of Orders of Nursing Professions, 2019. [Code of Ethics of Nursing Professions]. URL https://www.fnopi.it/aree-tematiche/codice-deontologico/ (accessed 9.21.22).

- Italian National Federation of Orders of Physicians and Dentists, 2014. [Code of Medical Ethics]. URL https://portale.fnomceo.it/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/CODICE-DEONTOLOGIA-MEDICA-2014-e-aggiornamenti.pdf (accessed 9.21.22).

- Johansson M., Wåhlin I., Magnusson L., Hanson E. Nursing staff’s experiences of intensive care unit diaries: a qualitative study. Nurs. Crit. Care. 2019;24:407–413. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liew S.M., Mordiffi S.Z., Ong Y.J.A., Lopez V. Nurses’ perceptions of early mobilisation in the adult Intensive Care Unit: A qualitative study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2021;66 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2021.103039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistraletti G., Giannini A., Gristina G., Malacarne P., Mazzon D., Cerutti E., Galazzi A., Giubbilo I., Vergano M., Zagrebelsky V., Riccioni L., Grasselli G., Scelsi S., Cecconi M., Petrini F. Why and how to open intensive care units to family visits during the pandemic. Crit. Care. 2021;25:191. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03608-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multidisciplinary Working Group “ComuniCovid” [Italian Society of Anesthesia and Intensive Care (SIAARTI), Italian Association of Critical Care Nurses (Aniarti), Italian Society of Emergency Medicine (SIMEU), and Italian Society of Palliative Care (SICP)], 2020. How to communicate with families of patients in complete isolation during SARS-CoV-2 pandemic multidisciplinary working group “ComuniCoViD”. Recenti Prog. Med. 111, 357–367. 10.1701/3394.33757. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Negro A., Villa G., Zangrillo A., Rosa D., Manara D.F. Diaries in intensive care units: An Italian qualitative study. Nurs. Crit. Care. 2022;27:36–44. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen A.H., Angel S., Hansen T.B., Egerod I. Structure and content of diaries written by close relatives for intensive care unit patients: A narrative approach (DRIP study) J. Adv. Nurs. 2019;75:1296–1305. doi: 10.1111/jan.13956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen A.H., Kvande M.E., Angel S. Humanizing and dehumanizing intensive care: thematic synthesis (HumanIC) J. Adv. Nurs. 2023;79:385–401. doi: 10.1111/jan.15477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ning J., Cope V. Open visiting in adult intensive care units – A structured literature review. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2020;56 doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2019.102763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nortvedt L. Vellykket prosjekt: dialog i sykepleie [Successful project: dialogue in nursing] Sykepleien. 1987;74:6–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nydahl P., Bäckman C.G., Bereuther J., Thelen M. How much time do nurses need to write an ICU diary? Nurs. Crit. Care. 2014;19:222–227. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien B.C., Harris I.B., Beckman T.J., Reed D.A., Cook D.A. Standards for reporting qualitative research. Acad. Med. 2014;89:1245–1251. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palese A., Mattiussi E., Fabris S., Caruzzo B.D., Achil I. The “Back to the Basics” movement: return to the past or sign of a “mature” nursing? Assist. Inferm. Ric. 2019;38:49–52. doi: 10.1702/3129.31110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker A.M., Sricharoenchai T., Needham D.M. Early rehabilitation in the intensive care unit: preventing impairment of physical and mental health. Curr. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Reports. 2013;1:307–314. doi: 10.1007/s40141-013-0027-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattison N., O’Gara G., Lucas C., Gull K., Thomas K., Dolan S. Filling the gaps: A mixed-methods study exploring the use of patient diaries in the critical care unit. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2019;51:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perier A., Revah-Levy A., Bruel C., Cousin N., Angeli S., Brochon S., Philippart F., Max A., Gregoire C., Misset B., Garrouste-Orgeas M. Phenomenologic analysis of healthcare worker perceptions of intensive care unit diaries. Crit. Care. 2013;17:R13. doi: 10.1186/cc11938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabow M.W., Huang C.S., White-Hammond G.E., Tucker R.O. Witnesses and victims both: healthcare workers and grief in the time of COVID-19. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;62:647–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.01.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roulin M.J., Hurst S., Spirig R. Diaries written for ICU patients. Qual. Health Res. 2007;17:893–901. doi: 10.1177/1049732307303304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield R., Dibb B., Coles-Gale R., Jones C.J. The experience of relatives using intensive care diaries: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2021;119 doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strandberg S., Vesterlund L., Engström Å. The contents of a patient diary and its significance for persons cared for in an ICU: A qualitative study. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs. 2018;45:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]