Abstract

Corruption has always existed in the field of national disaster management. Although many case studies on (anti)corruption have been carried out, these works have not dealt sufficiently with the evidence. The present research aims to study how to shift from corruption to anti-corruption, or simply, how to decrease corruption within the system. The comparative perspective is applied as the major methodology. The “damp-ground” style is where corruption breeds, whereas the “sunshine-based” style is where disaster management ethics, structure, transparency, and regional characteristics are established, sustained, and maximized. Therefore, the personnel, system, operating principles, and other relevant factors need to evolve and change to contribute significantly to the sunshine-based model. In this regard, stakeholders should carry out their roles and responsibilities effectively to succeed in disaster impact mitigation and overall disaster management. The contribution of this work lies in providing a comprehensive viewpoint on the shift from damp-ground corruption to sunshine-based anti-corruption toward the ultimate goal of disaster mitigation.

Keywords: Anti-corruption, Stakeholder ethics, Disaster management structure, Management transparency, Regional characteristics

Introduction

Various disasters have struck almost all nations in the international community. Accordingly, each nation has responded to these disasters with its own disaster management efforts. However, these efforts have not dramatically decreased the impacts of disasters, as evidenced by the amount of human losses, economic damages, and reported disasters over the years (IFRC, 2013; Newburn, 1993). One reason for this is corruption, which has adversely affected national efforts, as shown in Table 1. The field of disaster management is always tainted with certain kinds of corruption. Therefore, the issue of corruption is an urgent concern that should be appropriately addressed (Leeson & Sobel, 2008).

Table 1.

Examples of corruption in national disaster management

| Units | Specific examples |

|---|---|

| Africa |

- The large extent of corruption in disaster management systems in many African nations made the continental response against the Ebola outbreak worse in 2014 (McKenna, 2014) - Relief workers in West Africa often exchange food for sex during or after the occurrence of a disaster (Chonghaile, 2002) |

| Australia | - The Independent Commission Against Corruption in New South Wales investigated a water infrastructure company in 2014, which led to the resignation of the premier because of allegations of bribery (Parliament of Australia, 2017) |

| European Union |

- In a 2014 survey, about 74% of residents responded that they were affected by corruption in the field of disaster management (European Commission, 2014) - In 2006, the Bulgarian National Audit Agency discovered nationwide corruption infringements after the occurrence of natural disasters (The New Humanitarian, 2010) |

| Chile | In the twenty-first century, cases of noncompliance with building codes were discovered after the occurrence of earthquakes in Chile, although the extent of related corruption was not very high (Rojas et al., 2010) |

| China | After Li Wenliang, an ophthalmologist in Wuhan, revealed the potential outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) at the end of 2019 (BBC News, 2020), he was summoned and admonished by the police for allegedly spreading false information. He died of COVID-19, which eventually became a pandemic |

| Peru | After the Pisco earthquake in 2007, the congressional commission found financial irregularities in six reconstruction projects (Rapp, 2017) |

| India | In 2001, some administrators diverted a large amount of relief food intended for poor villages in India (Banik, 2016) |

| South Korea | Incidences of corruption were discovered during the emergency response to the sinking of the Sewol ferry in 2014, such as ethical failure on the part of the captain, religious corruption, and societal nepotism (Dostal et al., 2015) |

| Russia | Corruption prosecutors themselves were found to have obstructed effective national disaster management efforts (Brovkin, 2003) |

| Canada | Corporate corruption led to the Quebec train crash in 2013, which killed about 50 people (Murphy, 2018) |

| United States | In the aftermath of hurricane Katrina in 2005, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) approved contracts worth several hundred billion dollars without competition or proper bidding (Louisville, KY Courier - Journal, 2005) |

In the field of disaster management, a few researchers have studied the issue of corruption or anti-corruption through case studies. However, they have not sufficiently looked into the related evidence (Fenner, 2020b; Saharan, 2015). That is, these previous works have not fully explored how corruption has become pervasive and how it can be corrected or decreased to restore order in the system. As a result, many people continue to find it difficult to view corruption in disaster management from a macro perspective. Given these considerations, the present work addresses the need to comprehensively curb corruption in the field of disaster management by sufficiently evaluating the related evidence.

Specifically, the goal of this research is to examine how to substantially decrease the extent of corruption in the field of disaster management toward the ultimate goal of disaster management, including mitigating human losses, economic damages, and psychological impacts. The comparative perspective is used as the primary methodology. The “damp-ground” corruption style is systematically compared with the “sunshine-based” anti-corruption style through the analysis of four variables, namely, stakeholder ethics, disaster management structure, management transparency, and other regional characteristics.

The terms “damp-ground” and “sunshine-based” styles are specific to this work, partly in reference to the sunshine policy of South Korea toward North Korea. This policy (applied from 1998 to 2007) sought to bring about a peaceful coexistence between the two nations (Honarvar, 2018) and aimed to encourage reform and openness. It provides an analogy in relation to the present study. The sunshine-based style or approach to disaster management is meant to address or stop corruption, in reference to damp ground in which seeds of corrupt or shady practices grow. Damp ground can be dried up by sunshine to the point that the soil can no longer sustain growth, thus ending corruption and initiating anti-corruption.

Literature review

How corruption leads to disasters

Researchers have defined the concept of corruption differently (Aidt et al., 2008; Bose, et al., 2008). In this work, corruption is regarded as a global issue and as an illegal act or a dishonest behavior. However, corruption is also evaluated as a process, specifically as a complicated political process. Moreover, the scope of corruption is bigger than is commonly perceived, even including sex for food as another deviancy of sexual exploitation. From the comparative perspective, corruption will play a role in providing insights (or a comprehensive viewpoint) under different cultures or various development stages. Further, the legitimacy of corruption does matter in different regions in this article.

The concept of corruption in this paper continues to have unique nature in terms of criminology. As such, corruptive political decisions or government inaction under the title of state power results in massive violations of human rights during incidences of natural disasters or technological hazards and thus may be regarded as state crime (Green & Ward, 2000). At the same time, corporate power partially or fully relies on trade-off relations with state power for economic gains and thus ends up as corporate crime. In many aspects, corruption has been substantially embedded into the political economy (Sumah, 2018; Tillman, 2009). When the economy is limited or regulated, politicians have to make a series of decisions. The possibility of corruption is always present during such period, in particular because many people are willing to pay to evade economic restrictions.

Similarly, the concept of corruption in this research has its own legal standpoint. The definition of World Bank has been “abuse of public office for private gain,” as Transparency International has defined it as “the abuse of entrusted power for private gain” (Williams, 2021). Indeed, corruption has undermined the rule of laws in the field of disaster management, and thus many offenders have been punished. For example, in the twenty-first century, a majority of corrupt people in China have received imprisonment with reprieve or without reprieve. The number of falsified medical products such as unauthorized medications, coronavirus diagnostic kits, and others increased in many regions during the outbreak of COVID-19, and the corrupt medical providers have been prosecuted. Multiple offenders have been held responsible for violating statutes and regulations including politicians, businessmen, educators, members of the public, and others.

In the field of disaster management, corruption can be a cause or an effect of a disaster. A case of noncompliance with building codes caused a man-made disaster in Chile (Martin, 2017). Another case of noncompliance caused the sinking of the Sewol ferry in South Korea in 2014. Corrupt practices can also be consequences of disasters, such as the Ebola outbreak in Africa and the hurricane Katrina in the United States in 2005. In these cases, certain actions that followed disasters were deemed unethical or fraudulent (Houdek, 2020).

Corruption has a negative effect not only in the field of disaster management but also in any other areas in which it exists. Regardless of whether it is a cause or an effect, corruption is a critical factor that causes poverty and vulnerability in the event of disasters and other hazards. For example, an earthquake of a small magnitude (2.5 or less) may not cause major property damages and casualties. However, because of corruption, as manifested by the use of substandard building materials, some structures may collapse, causing property damages and loss of lives (USGS, 2023). In this case, a natural disaster is no longer a purely natural event but consequently becomes a man-made incident.

Additionally, failure to identify the connection between and among poverty, vulnerability, risks, and corruption may heighten the risks of disaster impacts (Bosher, 2008; Lewis, 2011, 2017; Lewis & Kelman, 2012). Without an awareness or recognition of the need to end corruption in disaster management, the extent of disaster impacts is likely to increase. In the process, corruption interferes with many activities, such as the merit discourse, management efforts, and decision-making that are meant to achieve efficient disaster management (Bo & Rossi, 2007; Hodgson & Jiang, 2007).

Corruption comes in many forms and has been shaped in many ways, such as by bureaucratic power and materialism (Dong & Torgler, 2013). It has diverse manifestations, including power, money, bribery, sexual exploitation, and special favors that benefit not only the greedy in society but also the political system and the processes of state formation, among many others. As a similar token, when corruption encompasses extensive or collective interests beyond individual interests, each type of corruption is differently born (DFID, 2015). At any rate, the field of disaster management must decrease the extent of corruption; for instance, stakeholders should use all means possible to prevent sexual exploitation through public awareness, screening, training, risk assessment, and outreach. Notwithstanding, corruption is still prevalent, mainly because the mode of corruption is too complicated among individuals, relations, contingency, and environments so that nobody can entirely abolish it.

Silence of disaster management literature on corruption

The subject of corruption and ways to manage it has been theoretically and empirically discussed by a number of researchers in various academic areas, such as criminal justice, public governance, economics, and world development. These works have reported that corruption causes political, economic, and social impacts by exchanging monetary and nonmonetary favors. However, many of these researches have been based on a multidisciplinary approach rather than on a single discipline because of the complicated connections of corruption to society (Gutierrez-Garcia & Rodriguez, 2016; Othman et al., 2014; Rodrigues-Neto, 2014).

Many researchers have also examined the importance of (anti)corruption in the field of disaster management (Katzarova, 2018), with the goal of raising the significance of international norms on anti-corruption by discussing global problems of corruption. Among these works, the core literature has looked into incidences of building collapse and malfeasance by officials and contractors in China, Italy, and Turkey.

During the earthquake in Sichuan, China in 2008, more than 5,000 children who were in school died. The investigation showed that corruption contributed to the disaster; substandard or low-quality materials were used in the school construction, causing the buildings to collapse easily during the earthquake and leading to the huge number of lives lost. In other words, the contractors focused on the monetary gains of the project and failed to regard safety as a major factor in the construction (The Guardian, 2009).

Similarly, a series of earthquakes have killed more than 115,600 people in Italy since the 1900s (Lewis, 2010). Not only corrupt procurement processes but also criminal fraud has been involved in construction and public works projects. In short, corruption has contributed to the large human losses resulting from building collapses in Italy.

In Turkey, several major earthquakes hit the nation toward the end of the twentieth century. The impacts of these disasters were due not so much to the magnitude of the earthquakes but to the conflicts and issues regarding government power, corporate interests, organized crime, and corruption (Green, 2005). During an earthquake in 2011, about 300 people were killed in Turkey. This number would have been smaller had national building codes been appropriately enforced (Black, 2011). However, whereas contractors sought financial gains without considering building safety, seismic regulators committed fraud, thus leading to a catastrophe.

The majority of the above-mentioned studies in the field of disaster management have explored the issue of corruption through case studies, particularly by focusing on related contexts. For example, many researchers have attempted to investigate the status of corruption in local areas or within a limited scope (Barone & Mocetti, 2014; Mendez & Sepulveda, 2010), thus providing unique viewpoints on corruption through the study of specific cases.

Some researchers, such as in the field of international relation or international law, have analyzed environmental migration in relation to disaster occurrences. Rising global temperatures have already displaced large populations, including those in sub-Saharan Africa, coastal regions, and low-lying areas. Given that the patterns of climate-based population displacement vary with the specific population, area, or related issues, including corruption, different public policies are needed to ensure the survival of those displaced (Gemenne, 2011). At the same time, international treaties or international institutions for forced migration should be formed to provide assistance in a timely manner (McAdam, 2012).

When applicable, support for environmental migration may help to address the extent of corruption in the field of disaster management. Corruption, including dirty politics, must be dealt with directly. A culture of change is necessary to shift from a heavily corrupted system to one that is corruption-free (Jensen & Bang, 2015). Therefore, it is critical and important that corruption in the field of disaster management be analyzed and resolved from an international perspective. As a reference, the reality of international perspective or international community has not been always right, when thinking some international attempts were much involved in corruption. For instance, an earthquake hit Haiti in 2010, but until 2020 the nation had not fully recovered from its impacts, partly due to the disorganized international aid (Savard et al., 2020). Nonetheless, an international perspective has been evaluated as one of the most open, adaptable, and reliable criteria in the field of disaster management (WHO, 2017).

The above discussion indicates that a thorough evaluation or analysis of corruption and anti-corruption has not yet been carried out and that an ideal model for eradicating corruption has not yet been established. Despite the detailed perspectives applied to (anti)corruption, many researchers have overlooked the comprehensive viewpoint on how to control corruption in the field (Foster et al., 2012). Hence, the value of this work lies in its focus on providing a holistic picture of corruption or anti-corruption in national disaster management from an international perspective.

Methods

Previous researchers or old styles on (anti)corruption have not sufficiently dealt with evidence on how to wholly get rid of corruption in the field of disaster management. Old styles are defined as those researches, which are related to case studies, micro-perspective, or the limited scope of (anti)corruption during research process. In other words, old styles have gathered various experiences, changed them to different levels of experience, and then connected them to new styles by piecemeal. Old styles have linked to their special agendas, items, or experiences via their own interpretation. Therefore, the application of a new approach in the present study contributes to conceptualizing the related problem or logical process from a system-wide perspective; that is, it provides a holistic approach (Jreisat, 2005; Kuhn, 1962; Mahmud & Prowse, 2012).

The comparative analysis was used in this study. Data on disaster management that discussed corruption and anti-corruption were collected from Google Scholar, Yahoo.com, OUP, RISS, and ScienceDirect, among others, and then interpreted. Most of the data came from reports from international journals; some were from books, government documents, and website contents. The majority of the contents were qualitative, but some numerical data were also included.

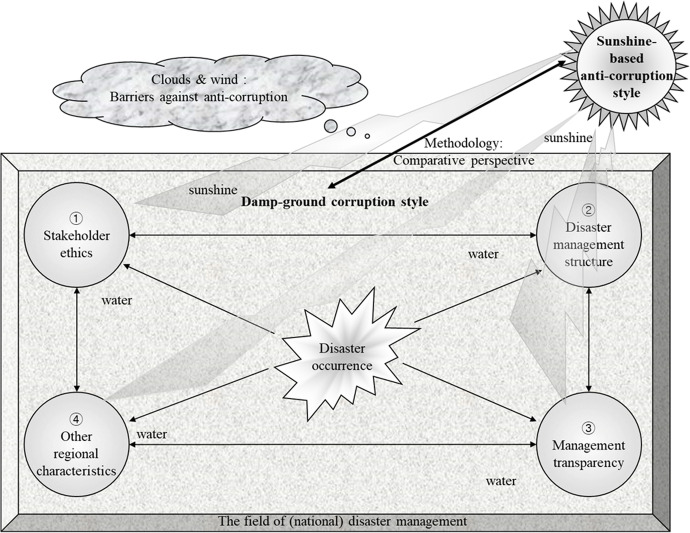

Figure 1 shows the framework of a disaster management system with the interplay of corruption (damp ground) and anti-corruption (sunshine-based).

Fig. 1.

Analytical framework

All major variables on corruption and anti-corruption in the field of disaster management were included in the framework, particularly on the basis of the qualitative content analysis (Elo et al., 2014). That is, the data were coded or sorted in terms of the big picture according to the keywords used in the search engines, including “corruption,” “anti-corruption,” “disasters,” “disaster management,” “corruption culture,” or any combination of these terms. Then, the same four variables, namely, stakeholder ethics, disaster management structure, management transparency, and other regional characteristics, were classified as comparative variables under the damp-ground corruption and the sunshine-based anti-corruption style, to achieve a scientific or systematic comparison of the two styles. When reflecting that this paper is to compare corruption (damp-ground corruption style) with anti-corruption (sunshine-based anti-corruption style) via those four variables, they are called to be comparative variables between two styles.

It can be expected that the above-mentioned four comparative variables may fold back all-important aspects of corruption or anti-corruption in the field of disaster management, when thinking that they are parallel to personnel, system, operating principles, and other features, respectively. For example, because personnel refers to human resources or human capital, then stakeholder ethics could serve as a guide in the field of disaster management. That is, stakeholder ethics could be considered as a call to action regarding disaster management (Johnstone, 2009). System refers to the dynamic structure of defining components, interfaces, data, and other aspects in the field; thus, a strong disaster management structure is an important foundation of disaster management. In short, a disaster management structure is a priority in the field and could serve as the basis of disaster management (Okada & Ogura, 2014).

Whereas operating principles are about meaningful strategies, management transparency is a starting point of a trust relationship among people. In other words, management transparency is a key characteristic of effective disaster management that strongly fosters disaster mitigation (Ahrens & Rudolph, 2006). In addition, considering that other features may include the rest of the components in the field, other regional characteristics may encompass complex aspects in diverse regions. In particular, this variable includes any additional factors, in cases when other researchers provide it with this grand model in the future. That is, regional characteristics should be regarded as inevitable environmental factors in the field (Xiao & Drucker, 2013). Given the above, the four variables considered play important roles either in sufficiently shaping corruption or in promoting anti-corruption.

By including all four comparative variables on (anti)corruption, this grand model has its own rational justification. In terms of feasibility, the grand model has the viability of a unique idea (Orsmond & Cohn, 2015). Because it includes all the important disaster variables, interactions, and environment, the model may feasibly or viably address the mechanism or operation of (anti)corruption. Regarding usefulness, the grand model may provide scientific information and knowledge on (anti)corruption for various disaster management practitioners (Hasan, 2014), as well as serve as a research guideline on how to efficiently curb corruption.

Besides, the original source of grand model is not a specific (anti)corruption theory. Rather, its provenance goes back to diverse previous case studies or theories, while admitting that the grand model has been fundamentally based on them and then initiated its new perspective on how to mitigate corruption at the macro level. Nevertheless, the grand model is somewhat different from those previous studies as well, when analyzing that those previous studies focused on (anti)corruption at macro level (Ashour & AboRemila, 2019). In a similar token, the grand model has approached the mechanism of disaster management or the matter of (anti)corruption more inclusively than previous studies did.

Damp-ground corruption style

Stakeholder ethics

Corruption creeps into and breeds in various organizations in which ethics and discipline are not basically observed and enforced (Gorsira et al., 2018). Some entities may even regard corruption as normal, thus causing further decay of morals, such as during the 2014 Kelantan flood in Malaysia and in the ethical issues on radiological protection in medical companies, among others (Bochud et al., 2020). A corrupt behavior may be a result of power, money, pride, or else; for some, the behavior may not necessarily be wrong and may even be considered desirable. Given this kind of thinking and behavior, stakeholders in the field of disaster management should put in place flexible controls in the system to end corruption and promote anti-corruption (Ashforth & Anand, 2003; Perera-Mubarak, 2012).

Disaster management structure

The nations that face corruption in disaster management are usually those that have not yet developed a disaster management structure (Miller & Rivera, 2011). Without such structure, corruption in the field could quickly spread throughout the nation. Based on natural disaster analyses from 1990 to 2010, the lack of a disaster management structure caused more corruption in developed nations than in developing nations (Yamamura, 2014). A disaster management structure includes the mechanism of disaster relief fund distribution, the system of voluntary organizations, and the overall national disaster management system.

The lack of appropriate structures in a society may foster corruption. This problem does not exist in the field of disaster management alone. Rather, it may be observed or experienced in the whole society, given that disaster management involves all the important components of society (Coppola, 2011). A good example is the natural disaster management in North Korea, in particular under the authoritarian regime. The level of corruption in the field of disaster management is very similar to that in the whole society.

Management transparency

Management transparency is vital to an organization aiming for zero corruption. When controls are vague, when there is no definite way to clarify instructions, and when there is no venue for discussion, some decisions may be influenced negatively, leading to corruption (UNDP, 2023). In Europe, the level of corruption regarding antibiotic resistance has generally increased during the health crisis, mainly because corruptive governments have not provided adequate supervision transparency on antibiotic resistance within the health industry (Vian, 2020). In Ecuador, the lack of a systematic approach to disaster risk reduction during the COVID-19 outbreak made the impacts of the pandemic bigger than expected (Cahuenas, 2021). Dirty politics and gimmickry result to a corrupt setting. Therefore, management principles and standards should be clear and firm, especially when it comes to compensating certain actions and distributing emergency or disaster-related resources.

Other regional characteristics

The way the field of disaster management operates basically depends on the cultural setting in the region. Under such cultural circumstances, corruption has also been shaped against disaster management. In South Korea, having a relationship with powerful individuals has been traditionally supported. As a result, nepotism has corrupted a variety of human relations than other tools (Kalinowski, 2016). In Japan, many residents have been unwilling to reveal their travel history to officials during the COVID-19 response because the Japanese culture holds that each person, and not other people, is responsible for coronavirus infection. Infected patients are thus afraid of getting negative reactions from other people in disclosing their travel history (Yamaguchi, 2020).

Similarly, the various religions in the region have played different roles in influencing the general trend of corruption in the field of disaster management. For instance, hierarchical religions, including Islam, Eastern Orthodoxy, and Catholicism have facilitated the challenges to the government less than egalitarian religions to include Protestantism. In so doing, these hierarchical religions have caused more corruption than egalitarian ones (Treisman, 2000).

Sunshine-based anti-corruption style

Stakeholder ethics

In educating all stakeholders on disaster management, the importance of anti-corruption as part of the field should be emphasized. Toward this end, educators need to substantially discuss the relationship between the extent of corruption and its effect on disaster management, as shown in Table 2. Furthermore, educators may form multiple coalitions among themselves and their trainees toward implementing anti-corruption measures (Giommoni, 2021).

Table 2.

Examples in support of the sunshine-based anti-corruption model

| Variables | Specific examples |

|---|---|

| ① Stakeholder ethics |

- In 2009, the Estonian Ministry of Finance planned and implemented an integrity training for public employees, which led to a proportional increase in awareness of anti-corruption in disaster management (Kasemets & Lepp, 2010; The World Bank, 2012) - According to an interview with 31 healthcare workers in Turkey in 2017, ethical intervention at the macro-level should be a significant factor for anti-corruption during a health crisis (Civaner et al., 2017) |

| ② Disaster management structure |

- After losing 6 million U.S. dollars during the Ebola outbreak in 2014/2016, the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) implemented a fraud prevention framework in 2017 (Jenkins et al., 2020) - In Sweden, an actual incident led to the establishment of a countrywide, rather than a single-agency, framework for disaster management (European Commission, 2021). Under this framework, Sweden has had the lowest level of corruption among nations in Europe (Gan Integrity, 2020) |

| ③ Management transparency |

- The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) lent 100 million U.S. dollars to Uruguay in 2020, on the condition of adequate financial transparency during natural hazards and health emergencies (IDB, 2020) - The FEMA introduced the Open FEMA Initiative to improve management transparency by supporting the efforts of public organizations to promote responsibility, effectiveness, and innovation (FEMA, 2020, 2023) |

| ④ Other regional characteristics |

- Despite challenges, some faith-based nongovernmental organizations tried to improve the anti-corruption culture in disaster management in Zambia in 2006, particularly by publishing related manuals (Zimba, 2006) - With the support of national governments, airlines in several regions have started to address the issue of manipulated COVID-19 certificates of passengers (Katz, 2021) |

Despite the apparent normalization of corruption in some areas, the field of disaster management has to continue the recruitment of stakeholders who will not be corrupted. However, it is not easy to distinguish which stakeholders will be corrupted and which ones will not. Although some tools have been applied, such as character references, Internet searches, and other informal security checks, the field may consider applying an intersectional approach to important posts. This approach uses multiple ground viewpoints, rather than a single ground viewpoint, during the recruitment process (Hankivsky, 2012).

Stakeholders must know how to control the extent of corruption in the system, such as by making the system economically and socially progressive while embodying the rule of law. Civil society should also contribute to monitoring corruption while promoting democratic values (UNODCCP, 1999). For example, civil society as a watchdog may dis-incentivize the extent of corruption by openly debating against corruption-prone entities; at the same time, as an interest group it may help regulate the issue of (anti)corruption by frequently associating with lawmakers. Similarly, because each community is in the best position to identify the diverse problems related to corruption, the whole community needs to coordinate their efforts toward anti-corruption as a sort of community-driven approach. All stakeholders in a community should thus participate in promoting anti-corruption (Sakib, 2022).

Disaster management structure

To effectively promote anti-corruption, the field of disaster management needs to establish its own structure. At the national level, a disaster operation framework should be set up (Bang, 2014). National efforts to eliminate corruption in all stakeholders should include governments, industries, volunteer organizations, the military, media, and all communities. The nation may locally subdivide its structure.

The leadership has to be involved in the establishment of a national disaster management structure. For example, in contrast to the Trump administration, U.S. president Joe Biden has nationally implemented COVID-19 vaccination, vaccine distribution, and related measures with full reliance on evidence-based science (Gostin et al., 2021). Leaders in both governments and private sectors should provide the momentum for putting order in the system and should be flexible in addressing complicated relationships (FEMA, 2011). Although leadership alone may not completely resolve the matter of a disaster management structure, without a strong leadership, the field cannot initiate or facilitate its attempts to establish an effective disaster management structure (Kerrissey & Edmondson, 2020).

Based on a national disaster management structure with a strong leadership, the field must consider combating corruption within the context of the whole society. Corruption cases should be investigated and then addressed at the societal level through the cooperative efforts of government authorities and nongovernment entities. A national campaign against corruption can be expected to defuse, if not eradicate, complex corrupt networks (Shiyanbade et al., 2017).

Management transparency

By flexibly adopting consistent procedures and policies, the field may improve its level of management transparency. For example, by implementing and evaluating consistent processes, transparency in the resource distribution process could be considerably enhanced. Also, by requiring a unified procedure, the field will send a strong message of transparency to all stakeholders (Neu et al., 2014).

Similarly, the field of disaster management must ensure that understandable and accessible information flows freely and as far as possible (Transparency International, 2006). Each nation may examine and then select neutral information for its own field or, if this is too difficult, the field may borrow and then apply internationally accepted information to its specific area. By using accredited information and formats, the field should be able to adhere to international standards.

Further, the field of disaster management should set up various networks to achieve the goal of management transparency. Individuals may compare and contrast how their disaster management works toward (anti)corruption through those networks. These networks aid the investigation or prosecution of corruption (Haanzadeh & Bashiri, 2016). That is, in gathering and sharing information, evidence, and human intelligence, they may partially or fully contribute to the investigation of corruption, which may then lead to prosecution. These stakeholders may actively rely on advanced technologies, such as network-driven ones, in their interactions with one another.

Other regional characteristics

In initiating efforts against disasters, the field of disaster management should determine how to approach the culture surrounding corruption or anti-corruption in its specific region (Huynh, 2020). By considering the unique nature of the regional culture, which is a macro-variable, the field may provide more appropriate alternatives to anti-corruption practices. As long as it sticks to micro-variables, the field will come up with conventional alternatives.

Moreover, religious leaders can help promote anti-corruption practices. In Nigeria, religious leaders, including Muslims and Christians, have played a major role in facilitating an understanding of the interrelationship among corruption, anti-corruption, and disaster management, in particular the benefits of collective action (Hoffmann & Patel, 2021). By preaching about the importance of integrity and morality (Adebayo, 2013), these religious leaders also become valuable partners in decreasing corruption in the field of disaster management.

Discussion

Interrelationship around (anti)corruption

Corruption is nothing new. It breeds and thrives in many fields, including that of disaster management. In any system, seeds of corruption may grow in the presence of damp ground, thus the need to work toward zero corruption. Anti-corruption is not an alternative, but it is what is needed (Schultz & Soreide, 2008). This is where the sunshine-based style comes in. The sunshine represents the solution: it dries up the damp ground and, as a result, decreases corruption.

To achieve this state, a strong interrelationship among the four above-mentioned variables is necessary. An interrelationship as a close relationship refers to the way in which two or more factors are related to each other. All stakeholders need to work hard and together to promote ethics, a solid structure, transparency, and positive regional characteristics (Jain, 2011).

The road to transformation will not be easy and is likely to include vital changes, such as replacing management and personnel, modifying procedures and policies, and constant policing and vigilance. Consistent ethical and moral actions and continuous progressive interaction are essential to achieve a corruption-free system (Novella-Garcia & Cloquell-Lozano, 2021).

In the end, the sunshine should prevail. That is, the sunshine-based anti-corruption style is the one that the field of disaster management should pursue. As the sunshine dries up the damp ground, corruption dies (Alt & Lessen, 2012). A new ground becomes ready and available for a corruption-free system, in this case, in the field of disaster management.

Other recommendations for a style shift

The results of the comparison between the two styles emphasize the need for the field of disaster management to shift from damp-ground corruption to sunshine-based anti-corruption. Without eradicating or lessening the prevailing corruption, the impacts of disasters, such as human losses, economic damages, and psychological impacts, would not be significantly decreased. Ultimately, the field may not achieve its goal of effective disaster management.

The shift from corrupt to anti-corrupt practices is not easy (Fjeldstad & Isaksen, 2008). There is no silver bullet to embody the extent of anti-corruption in the field of disaster management. Similarly, disaster management agencies in each nation are pressurized by activists during and after disasters such as the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004 and the outbreak of COVID-19. While a high number of goods, services, and cashes move into the affected areas in a short time, some disaster management agencies are involved in corruption without moral dilemma (Fenner, 2020a). To this end, these agencies have to check the humanitarian response to achieve anti-corruption. This task is challenging in general; however, by sticking to specific and clear-cut stakeholder responsibilities, the road to anti-corruption becomes navigable.

Moreover, appropriate leaders in the field of disaster management have to commit their leadership on the way to the style shift. Whereas the role of the four comparative variables should not be disregarded, leaders should pull the trigger toward anti-corruption (Stoller, 2020). Without efficient leadership or a clear vision against corruption, the four stakeholders will find it difficult to triumph against corruption.

With the right initiative and leadership, the field of disaster management may use employment system for the goal of anti-corruption style. That is, the field may assign specific duties and responsibilities to both employers and employees in relation to the style shift. Policies on good governance and whistleblowing may also be established (Carr & Lewis, 2010).

The field of disaster management needs to work further on internal controls against corruption. For example, it may lend strong support to traditional alternatives against corruption, such as the application of policy manuals, the maintenance of related documents and records, and the complaint reporting system within each organization (Volkov, 2014). Moreover, the field has to monitor the progress of disaster management from the beginning until the completion of the style shift.

The field of disaster management should also continue to set up diverse networks. Those who are keenly interested in pursuing anti-corruption may establish their own network among their members. The field may set up a unified network toward the goal of advancing anti-corruption, particularly by integrating a series of small-scale networks. Vice versa, small-scale networks may more actively or flexibly react to corruption or anti-corruption (Wang et al., 2012).

In a similar token, the field of disaster management must apply the sunshine-based anti-corruption style as a community-driven approach. One or two individuals will not solve the problem. Given its size and complexity, resolving the issue of corruption requires the collective efforts of the community. Hence, the sunshine-based anti-corruption style may serve as a comprehensive solution against corruption.

The reality of corruption has a long history in many nations, and eliminating the problem has not been easy throughout history. Among the many tools against corruption, however, the field of disaster management needs to apply cutting-edge technology (Adam & Fazekas, 2018). Such reliance on technological developments, such as individual soldier’s access to his or her cellular phone in military system, would be an effective tool in facilitating the style shift.

For instance, the field of disaster management can disseminate anti-corruption information to all stakeholders through the Internet. Some scientific reports have empirically proven that the Internet could help decrease the extent of corruption in the field of disaster management by opening diverse communication channels, regardless of national boundaries. Additionally, the field may use many related technologies, such as global satellite data and lightning density, for information dissemination (Andersen et al., 2011).

Conclusion

Corruption and anti-corruption are opposing acts. The former impairs integrity and morals, whereas the latter counters such impairment. The goal of this research was to provide a framework on how to shift from corruption to anti-corruption in the field of disaster management. Toward this end, mostly qualitative and some quantitative data were used. By providing two distinctive styles, namely, damp-ground corruption and sunshine-based anti-corruption, the objective of the work was achieved. In particular, qualitative content analysis was used to explore a style shift regarding (anti)corruption.

In disaster management, corruption is likened to damp ground in which corrupt practices can grow, whereas anti-corruption is the sunshine that can stop such growth. Among the many variables on corruption and anti-corruption in this field, this study focused on stakeholder ethics, structure, transparency, and regional characteristics. To achieve a style shift from corruption to anti-corruption, these variables must be nurtured by implementing control measures and policies, including education and training to combat and eradicate corruption. For example, whereas decision-makers fully rely on the principle of fairness during decision-making, first responders have to respond to diverse emergencies without intentional delay.

Certain kinds of corruption have long existed in the field of disaster management. Thus, the effects of corruption on disaster management have been frequently suspected. To decrease corruption, the field should not allow any barriers or challenges to overcome moral actions; otherwise, the damp ground on which corruption breeds would not dry up. Instead, the field must let the sunshine dry up the damp ground; if not, the shift toward the sunshine-based anti-corruption style would fail, and the field would not achieve the goal of disaster management.

In the style shift from corruption to anti-corruption, the field of disaster management should consider applying a comprehensive perspective. Without incorporating or relying on the macro-perspective, the minute efforts of the field toward anti-corruption would not be so effective, like the negative aspect discussed in many case studies. The main contribution of this work is its application of a comprehensive viewpoint on the style shift toward the ultimate goal of disaster mitigation.

Future researchers in the field of disaster management should further study the relationship between corruption and anti-corruption. They may examine the big picture of (anti)corruption to a greater extent; carry out case studies using the comprehensive viewpoint, as shown in this work; or apply an empirical approach to the style shift. These could aid the international community toward achieving more efficient ways to mitigate the impacts of catastrophes.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Adam, I., & Fazekas, M. (2018). Are emerging technologies helping win the fight against corruption in developing countries? Pathways for Prosperity Commission.

- Adebayo, R. I. (2013). The imperative for integrating religion in the anti-corruption crusade in Nigeria: A Muslim perspective. Centrepoint Journal,15, 1–24. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/29767193

- Ahrens J, Rudolph PM. The importance of governance in risk reduction and disaster management. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 2006;14(4):207–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5973.2006.00497.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aidt T, Dutta J, Sena V. Governance regimes, corruption and growth: Theory and evidence. Journal of Comparative Economics. 2008;36(2):195–220. doi: 10.1016/j.jce.2007.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alt JE, Lessen DD. Enforcement and public corruption: Evidence from the American states. The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization. 2012;30(2):306–338. doi: 10.1093/jleo/ews036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen TB, Bentzen J, Dalgaard C-J, Selaya P. Does the Internet reduce corruption? Evidence from U.S. states and across countries. The World Bank Economic Review. 2011;25(3):387–417. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhr025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth BE, Anand V. The normalization of corruption in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior. 2003;25:1–52. doi: 10.1016/S0191-3085(03)25001-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashour AS, AboRemila HS. A conceptual analysis of macro corruption: Dimensions and forward and backward linkages. Journal of Public Administration and Governance. 2019;19(2):277–299. doi: 10.5296/jpag.v9i2.14983. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bang HN. General overview of the disaster management framework in Cameroon. Disasters. 2014;38(3):562–586. doi: 10.1111/disa.12061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banik D. The hungry nation: Food policy and food politics in India. Food Ethics. 2016;1:29–45. doi: 10.1007/s41055-016-0001-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barone G, Mocetti S. Natural disasters, growth and institutions: A tale of two earthquakes. Journal of Urban Economics. 2014;84:52–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jue.2014.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black, W. K. (2011). Corruption and crony capitalism kill. World Press. Retrieved March 9, 2020, from https://neweconomicperspectives.org/2011/10/corruption-and-crony-capitalism-kill.html

- Bo ED, Rossi MA. Corruption and inefficiency: Theory and evidence from electric utilities. Journal of Public Economics. 2007;91(5/6):939–962. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2006.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bochud F, Cantone MC, Applegate K, Coffey M, Damilakis J, Perez MR, Fahey F, Jesudasan M, Kurihara-Saio C, Guen B, Malone J, Murphy M, Reid J, Zolzer F. Ethical aspects in the use of radiation in medicine: Update from ICRP Task Group 109. Annals of the ICRP. 2020;49(1 suppl.):143–153. doi: 10.1177/0146645320929630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose N, Capasso S, Murshid AP. Threshold effects of corruption: Theory and evidence. World Development. 2008;36(7):1173–1191. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.06.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bosher L. Introduction: The need for built-in resilience. In: Bosher L, editor. Hazards and the built environment. Routledge; 2008. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Brovkin VN. Corruption in the 20th century Russia. Crime, Law and Social Change. 2003;40:195–230. doi: 10.1023/A:1025741929051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cahuenas, H. (2021). Forum: Disaster risk governance and COVID-19 accountability, transparency, and corruption. Yale Journal of International Law. Retrieved June 6, 2021, from https://www.yjil.yale.edu/forum-disaster-risk-governance-and-covid-19-accountability-transparency-and-corruption/

- Carr I, Lewis D. Combating corruption through employment law and whistleblower protection. Industrial Law Journal. 2010;39(1):52–81. doi: 10.1093/indlaw/dwp027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chonghaile CN. Sex-for-food scandal in West African refugee camps. The Lancet. 2002;359(9309):860–861. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07985-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civaner M, Vatansever K, Pala K. Ethical problems in an era where disasters have become a part of daily life: A qualitative study of healthcare workers in Turkey. Plos One. 2017;12(3):e0174162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola DP. Introduction to international disaster management. Elsevier; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Department for International Development (DFID) Why corruption matters: Understanding causes, effects and how to address them. Department for International Development; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dong B, Torgler B. Causes of corruption: Evidence from China. China Economic Review. 2013;26:152–169. doi: 10.1016/j.chieco.2012.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dostal JM, Kim H-J, Ringstad A. A historical-institutionalist analysis of the MV Sewol and MS Estonia tragedies: Policy lessons from Sweden for South Korea. The Korean Journal of Policy Studies. 2015;30(1):35–71. doi: 10.52372/kjps30102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S, Kaariainen M, Kanste O, Polkki T, Utriainen K, Kyngas H. Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open. 2014;4(1):1–10. doi: 10.1177/2158244014522633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- European Commission . Report from the commission to the council and the European Parliament: EU anti-corruption report. European Commission; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission (2021). Sweden. European Commission. Retrieved January 12, 2023, from https://civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu/what/civil-protection/national-disaster-management-system/sweden_en

- Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Leadership in emergency management. FEMA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- FEMA (2020). FEMA’s natural disaster preparedness and response efforts during the coronavirus pandemic. FEMA. Retrieved December 31, 2022, from https://www.fema.gov/fact-sheet/femas-natural-disaster-preparedness-and-response-efforts-during-coronavirus-pandemic

- FEMA (2023). Open FEMA. FEMA. Retrieved January 4, 2023, from https://www.fema.gov/about/reports-and-data/openfema

- Fenner, G. (2020a). Corruption in natural disaster situation: Can our experiences help prevent corruption related to covid-19? Basel Institute on Governance. Retrieved November 13, 2022, from https://baselgovernance.org/blog/corruption-natural-disaster-situations-can-our-experiences-help-prevent-corruption-related

- Fenner, G. (2020b). How to curb corruption in natural disaster situations – and pandemics. Basel Institute on Governance. Retrieved December 7, 2020b, from https://baselgovernance.org/blog/how-curb-corruption-natural-disaster-situations-and-pandemics

- Fjeldstad O-H, Isaksen J. Anti-corruption reforms: Challenges, effects and limits of World Bank support. The World Bank; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Foster JE, Horowitz AW, Mendez F. An axiomatic approach to the measurement of corruption: Theory and applications. The World Bank Economic Review. 2012;26(2):217–235. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhs008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gan Integrity (2020). Sweden risk report. Gan Integrity. Retrieved January 1, 2023, from https://ganintegrity.com/country-profiles/sweden/

- Gemenne F. Climate-induced population displacements in a 4°C+ world. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 2011;369:182–195. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2010.0287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giommoni T. Exposure to corruption and political participation: Evidence from Italian municipalities. European Journal of Political Economy. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2021.102000. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorsira M, Steg L, Denkers A, Huisman W. Corruption in organizations: Ethical climate and individual motives. Administrative Sciences. 2018;8(1):4. doi: 10.3390/admsci8010004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gostin LO, Shalala DE, Hamburg MA, Bloom BR, Koplan JP, Rimer BK, Williams MA. A global health action agenda for the Biden administration. The Lancet. 2021;397(10268):5–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32585-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green P. Disaster by design: Corruption, construction and catastrophe. The British Journal of Criminology. 2005;45(4):528–546. doi: 10.1093/bjc/azi036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Green, P., & Ward, T. (2000). State crime, human rights, and the limits of criminology. Social Justice, 27(1), 101–115. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.jstor.org/stable/29767193

- Gutierrez-Garcia JO, Rodriguez L-F. Social determinants of police corruption: Toward public policies for the prevention of police corruption. Policy Studies. 2016;37(3):216–235. doi: 10.1080/01442872.2016.1144735. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haanzadeh H, Bashiri M. An efficient network for disaster management: Model and solution. Applied Mathematical Modelling. 2016;40(5/6):3688–3702. doi: 10.1016/j.apm.2015.09.113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hankivsky O, editor. An intersectionality-based policy analysis framework. Simon Fraser University; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan L. The usefulness of user testing methods in identifying problems on university websites. Journal of Information Systems and Technology Management. 2014;11(2):229–256. doi: 10.4301/S1807-17752014000200002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, G. M., & Jiang, S. (2007). The economics of corruption and the corruption of economics: An institutionalist perspective. Journal of Economic Issues,41(4), 1043–1061. Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://ssrn.com/abstract=1174283

- Hoffmann LK, Patel RN. Collective action on corruption in Nigeria: The role of religion. The Royal Institute of International Affairs; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Honarvar K. Sunshine: Bright over decades. ASIANetwork Exchange: A Journal for Asian Studies in the Liberal Arts. 2018;25(1):149–159. doi: 10.16995/ane.259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houdek P. Fraud and understanding the moral mind: Need for implementation of organizational characteristics into behavioral ethics. Science and Engineering Ethics. 2020;26:691–707. doi: 10.1007/s11948-019-00117-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh, T. L. D. (2020). Does culture matter social distancing under the COVID-19 pandemic? Safety Science, 130(130), 104872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Inter-American Development Bank (IDB). (2020). IDB supports Uruguay tackle natural disaster and health emergency impacts. IDB. Retrieved May 25, 2021, from https://www.iadb.org/en/news/idb-supports-uruguay-tackle-natural-disaster-and-health-emergency-impacts

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) World disasters report 2013: Focus on technology and the future of humanitarian action. IFRC; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A. K. (2011). Corruption: Theory, evidence and policy. CESifo DICE Report,2(9), 3–9. https://www.ifo.de/DocDL/dicereport211-forum1.pdf

- Jenkins, M., Khaghahordyan, A., Rahman, K., & Duri, J. (2020). The costs of corruption during humanitarian crises, and mitigation strategies for development agencies. CMI. Retrieved June 4, 2021, from https://www.u4.no/publications/the-costs-of-corruption-during-humanitarian-crises-and-mitigation-strategies-for-development-agencies

- Jensen MJ, Bang H. Digitally networked movements as problematization and politicization. Policy Studies. 2015;36(6):573–589. doi: 10.1080/01442872.2015.1095879. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnstone M-J. Health care disaster ethics: A call to action. Australian Nursing Journal. 2009;17(1):27. doi: 10.1177/2158244014522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jreisat JE. Comparative public administration is back in, prudently. Public Administration Review. 2005;65(2):231–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6210.2005.00447.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalinowski T. Trends and mechanisms of corruption in South Korea. The Pacific Review. 2016;29(4):625–645. doi: 10.1080/09512748.2016.1145724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kasemets A, Lepp U. Anti-corruption programmes, studies and projects in Estonia 1997–2009: An overview. European Research Centre for Anti-Corruption and State-Building; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, B. (2021). Fake COVID-19 certificates hit airlines, which now have to police them. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 29, 2021, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/fake-covid-19-certificates-hit-airlines-which-now-have-to-police-them-11618330621

- Katzarova E. From global problems to international norms: What does the social construction of a global corruption problem tell us about the emergence of an international anti-corruption norm. Crime, Law and Social Change. 2018;70:299–313. doi: 10.1007/s10611-017-9733-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrissey, M. J., & Edmondson, A. C. (2020). What good leadership looks like during this pandemic. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved December 9, 2020, from https://hbr.org/2020/04/what-good-leadership-looks-like-during-this-pandemic

- Kuhn, T. S. (1962). The structure of scientific revolutions. The University of Chicago Press.

- Leeson PT, Sobel RS. Weathering corruption. Journal of Law and Economics. 2008;51(4):667–681. doi: 10.1086/590129. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. Corruption: The hidden perpetrator of under-development and vulnerability to natural hazards and disasters. Journal of Disaster Risk Studies. 2011;3(2):464–475. doi: 10.4102/jamba.v3i2.43. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J. Social impacts of corruption upon community resilience and poverty. Journal of Disaster Risk Studies. 2017;9(1):a391. doi: 10.4102/jamba.v9i1.391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- J Lewis I Kelman 2012 The good, the bad and the ugly: Disaster risk reduction (DRR) versus disaster risk creation (DRC) Plos: Current Disasters 10.1371/4f8d4eaec6af8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lewis, J. (2010). Corruption and earthquake destruction: Observations on events in Turkey, Italy and China. Research Gate. Retrieved February 29, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/266477383_Corruption_and_earthquake_destruction_Observations_on_events_in_Turkey_Italy_and_China

- Louisville, KY Courier - Journal (2005). FEMA awarded $100s of billions of Katrina contracts without bidding or with curtailed competition. Most Corrupt Agencies. Retrieved March 6, 2020, from https://mostcorrupt.com/Agencies--FEMA.htm

- Mahmud T, Prowse M. Corruption in cyclone preparedness and relief efforts in coastal Bangladesh: Lessons for climate adaptation? Global Environmental Change. 2012;22(4):933–943. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2012.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JD. Chile disaster management reference handbook. Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- McAdam J. Climate change, forced migration, and international law. Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, M. (2014). African scientist: African corruption made Ebola worse. WIRED. Retrieved March 15, 2020, from https://www.wired.com/2014/11/ebola-africa/

- Mendez F, Sepulveda F. What do we talk about when we talk about corruption? The Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization. 2010;26(3):493–514. doi: 10.1093/jleo/ewp003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DS, Rivera JD, editors. Comparative emergency management: Examining global and regional responses to disasters. Taylor & Francis Group; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, J. (2018). Lac-Megantic: The runaway train that destroyed a town. BBC News. Retrieved December 21, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-42548824

- Neu D, Everett J, Rahaman AS. Preventing corruption within government procurement: Constructing the disciplined and ethical subject. Critical Perspectives on Accounting. 2014;28:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cpa.2014.03.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newburn T. Footing the bill after disaster. Policy Studies. 1993;14(3):41–49. doi: 10.1080/01442879308423643. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- BBC News (2020). Li Wenliang: Coronavirus death of Wuhan doctor sparks anger. BBC. Retrieved March 4, 2020, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-51409801

- Novella-Garcia C, Cloquell-Lozano A. The ethics of maxima and minima combined with social justice as a form of public corruption prevention. Crime, Law and Social Change. 2021;75:281–295. doi: 10.1007/s10611-020-09921-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Okada A, Ogura K. Japanese disaster management system: Recent developments in information flow and chains of command. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management. 2014;22(1):58–62. doi: 10.1111/1468-5973.12041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orsmond, G. I., & Cohn, E. S. (2015). The distinctive features of a feasibility study: Objectives and guiding questions. QTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health, 35(3), 169–177. 10.1177/1539449215578649 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Othman, Z., Shafie, R., & Hamid, F. Z. A. (2014). Corruption – Why do they do it? Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences,164, 248–257. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.11.074

- Parliament of Australia (2017). Chapter 3: State, territory and international integrity commissions. In: Commonwealth of Australia,Select Committee on a National Integrity Commission (1st ed., pp. 105–180). Senate Printing Unit.

- Perera-Mubarak KN. Reading ‘stories’ of corruption: Practices and perceptions of everyday corruption in post-tsunami Sri Lanka. Political Geography. 2012;31(6):368–378. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2012.05.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rapp, J. (2017). 2007 Peru earthquake 10 years on: Is Peru prepared for the next big one? Peru Reports. Retrieved January 23, 2021, from https://perureports.com/2007-peru-earthquake-10-years-peru-prepared-next-one/6197/

- Rodrigues-Neto JA. On corruption, bribes and the exchange of favors. Economic Modelling. 2014;38:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.econmod.2013.12.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas F, Lew M, Naeim F. An overview of building codes and standards in Chile at the time of the 27 February 2010 offshore Maule, Chile earthquake. The Structural Design of Tall and Special Buildings. 2010;19(8):853–865. doi: 10.1002/tal.676. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saharan V. Disaster management and corruption: Issues, interventions and strategies. In: Ha H, Fernando R, Mahmood A, editors. Strategic disaster risk management in Asia. Springer; 2015. pp. 193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Sakib NH. Community organizing in anti-corruption initiatives through spontaneous participation: Bangladesh perspective. Community Development Journal. 2022;57(2):360–379. doi: 10.1093/cdj/bsaa027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Savard, J. F., Sael, E., & Clormeus, J. (2020). A decade after the earthquake, Haiti still struggles to recover. The Conversation. Retrieved June 15, 2021, from https://theconversation.com/a-decade-after-the-earthquake-haiti-still-struggles-to-recover-129670

- Schultz JL, Soreide T. Corruption in emergency procurement. Disasters. 2008;32(4):516–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2008.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiyanbade BW, Bello AM, Diekola OJ, Wahab YB. Assessing the efficiency and impact of national anti-corruption institutions in the control of corruption in Nigeria society. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 2017;22(7):36–64. doi: 10.9790/0837-2207055664. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stoller JK. Reflections on leadership in the time of COVID-19. BMJ Leader. 2020;4:77–79. doi: 10.1136/leader-2020-000244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sumah S. Corruption, causes and consequences. In: Bobek V, editor. Trade and global market. IntechOpen; 2018. pp. 63–79. [Google Scholar]

- The Guardian (2009). Sichuan earthquake killed more than 5,000 pupils, says China. The Guardian. Retrieved December 2, 2020, from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/may/07/china-quake-pupils-death-toll

- The New Humanitarian (2010). Fighting corruption in disaster response. PreventionWeb. Retrieved January 7, 2021, from https://www.preventionweb.net/news/view/12581

- The World Bank (2012). Latin America: Putting disaster preparedness on the radar screen. World Bank Group. Retrieved February 11, 2020, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2012/10/09/desastres-naturales-america-latina-crecimiento-riesgo

- Tillman R. Making the rules and breaking the rules: The political origins of corporate corruption in the new economy. Crime, Law and Social Change. 2009;51:73–86. doi: 10.1007/s10611-008-9150-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Transparency International (2006). Working paper #03/2006: Corruption in humanitarian aid. Transparency International.

- Treisman D. The causes of corruption: A cross-national study. Journal of Public Economics. 2000;76(3):399–457. doi: 10.1016/S0047-2727(99)00092-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Geological Society (USGS) (2023). Earthquake facts & earthquake fantasy. USGS. Retrieved January 11, 2023, from https://www.usgs.gov/natural-hazards/earthquake-hazards/science/earthquake-facts-earthquake-fantasy?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects

- UN Office for Drug Control and Crime Prevention (UNODCCP) (1999). Prevention: An effective tool to reduce corruption. Centre for International Crime Prevention.

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) (2023). Transparency, accountability and anti-corruption. UNDP. Retrieved January 5, 2023, from https://www.asia-pacific.undp.org/content/rbap/en/home/democratic-governance-and-peacebuilding/transparency-and-anti-corruption.html

- Vian T. Anti-corruption, transparency and accountability in health: Concepts, frameworks, and approaches. Global Health Action. 2020;13(1):1694744. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2019.1694744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkov, M. (2014). A close look at internal controls. Volkov Law Group. Retrieved December 6, 2020, from https://blog.volkovlaw.com/2014/04/a-close-look-at-internal-controls/

- Wang Z, Ma M, Wu J. Securing wireless mesh networks in a unified security framework with corruption-resilience. Computer Networks. 2012;56(12):2981–2993. doi: 10.1016/j.comnet.2012.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A. (2021). Corruption definitions and their implications for targeting natural resource corruption. Bergen: U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, Chr. Michelsen Institute (TNRC Publication). Retrieved January 24, 2023, from https://www.cmi.no/publications/file/7849-corruption-definitions-and-their-implications-for-targeting-natural-resource-corruption.pdf

- World Health Organization (WHO) A strategic framework for emergency preparedness. WHO Document Production Services; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Drucker J. Does economic diversity enhance regional disaster resilience? Journal of the American Planning Association. 2013;79(2):148–160. doi: 10.1080/01944363.2013.882125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, M. (2020). In Japan, pandemic brings outbreaks of bullying, ostracism. Bell Media. Retrieved June 22, 2021, from https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/in-japan-pandemic-brings-outbreaks-of-bullying-ostracism-1.4932762

- Yamamura E. Impact of natural disaster on public sector corruption. Public Choice. 2014;161:385–405. doi: 10.1007/s11127-014-0154-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zimba, W. (2006). Managing humanitarian programmes in least-developed countries: The case of Zambia. Humanitarian Practice Network. Retrieved January 7, 2023, from https://odihpn.org/publication/managing-humanitarian-programmes-in-least-developed-countries-the-case-of-zambia/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.