Abstract

Background

There are approximately 352,000 pharmacists practicing in the United States with most (59%) being female. Editorial board membership and publications with a female as the first author in selected pharmacy journals has increased in the past two decades. This study determined if these positive trends are also occurring in critical care pharmacy.

Objective(s)

To report publication rate stratified by male and female gender amongst pharmacists designated Fellow of Critical Care Medicine (FCCM).

Methods

Pharmacists designated FCCM from inception through the 2020 convocation year were identified in January 2021 using a list provided by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Pharmacists were excluded if they were designated Master of Critical Care Medicine, did not have an active pharmacist license, or did not have data in the Scopus database. Data were collected in February 2021 including year of first publication, total number of publications, citations, and Hirsch index (h-index).

Results

134 pharmacists were evaluable including 76 (57%) males and 58 (43%) females. Males had an earlier first publication year compared to females (2005 vs. 2010; p=0.0002). Males have produced a higher number of publications per individual pharmacist (29 vs. 13; p=0.002) and a similar number of publications per year (2 vs. 1; p=0.05). When comparing publication impact, males generated more citations (384 vs. 139; p=0.001) and had a higher h-index (10 vs. 6, p=0.0005). These trends persisted when data from only the past five years were used.

Conclusion

There is significant gender disparity in publication rate and impact. However, this disparity seems to be decreasing with time as the rate of females designated FCCM is increasing. This is consistent with an overall increase in the proportion of pharmacists who are female and deserves further exploration.

Keywords: gender disparity, critical care pharmacists, critical care

Background

Legislation regulating pharmacy practice in the United States was introduced around 1736, and by the late 1700s, pharmacists were standalone practitioners. In the 1870 census, 34 women (0.2%) and 17,335 men (99.8%) were “druggists”.1 Most pharmacists were males until the 2010s when females surpassed them for the first time. Today, there are approximately 352,000 pharmacists in the United States with most (59%) being female.1

In 1970, 29 physicians founded the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM). In 2000, the SCCM and the American College of Clinical Pharmacy (ACCP) published a first-ever position paper on critical care pharmacy services.2 Today, pharmacists represent 12% of the SCCM’s total membership of approximately 16,000 people, and many engage in scholarly activities.3

The 2020 SCCM, ACCP and American-Society of Health-Systems Pharmacists Position Paper on Critical Care Pharmacy Services stated research is essential at level I centers, and desirable at level II and III centers.4 A benchmarking study reported pharmacists designated as a Fellow within the American College of Critical Care Medicine (ACCM; FCCM) are academically productive, but data were not stratified by gender, meaning conclusions could not be drawn on differences between genders.5

Gender disparities have been reported across various disciplines and specialties of medicine. Within academic pharmacy, female involvement in editorial boards and as a primary author in selected pharmacy journals has been increasing over the last two decades.6,7 It is unknown whether these positive trends are also occurring in critical care pharmacy.

Objective(s)

The primary objective was to report publication rate stratified by gender amongst pharmacists designated FCCM by the ACCM. The secondary objective was to stratify the results using data from the past five convocation years. The tertiary objective was to place the results into context given the change in pharmacist demographics in the past 40 years in the United States.

Methods

Pharmacist Identification

Pharmacists designated FCCM from the inception of the ACCM in 1988 through the 2020 convocation year were identified by the SCCM in January 2021. Pharmacists were excluded if they were designated Master of Critical Care Medicine (MCCM), did not have an active pharmacist license using a State Board of Pharmacy, or did not have data in the Scopus citation database. The methods for this study have been previously published and are updated here.5

Online Citation Databases

Scopus is an online citation database established in 2004 by Elsevier Incorporated. It contained 84 million records as of December 2021 with 17.6 million user profiles.8 Scopus Preview is free to use and does not require registration. A last and first name were entered into the “Authors” search function to identify pharmacists. Profiles were reviewed based on author name, affiliation, city, and country. Each author’s citation list was manually reviewed to ensure publication dates, journals, and subject matter was appropriate.

Demographic Data

Demographic data included state and geographic region of practice, number of staffed beds, and hospital designation (i.e., academic or community). Current practice site and gender was determined using an online search and the SCCM Member Directory. Number of staffed beds and hospital designation was obtained from the American Hospital Association’s (AHA) 2018 Annual Survey.9 Region within the United States was defined according to the United States Census Bureau.1

Scholarly Activity Data

Data were collected in February 2021 including year of first publication, total number of publications, citations, and Hirsch index (h-index). An h-index of 10 means an author has 10 publications with at least 10 citations. Article type was obtained from Scopus’ citation export function including original research, review, letter or note, editorial, conference paper, book or book chapter, or erratum. If two authors, both designated FCCM appeared on the same publication, the citation counted for each individual but duplicated for the cohort as a whole. Duplicate publications appearing in an author’s list more than once were removed. Publications from the year of convocation were not included because convocation typically occurs in January or February. Published abstracts were not included. The author could appear in any place on the author list.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are reported as median (Q1, Q3) and were compared using the nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test. Proportions are presented as number (%) and compared with the chi-squared test for categorical variables. A stratified analysis using data from the past five convocation years within the data (2015 to 2020) set was also conducted. A p-value <0.05 was statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

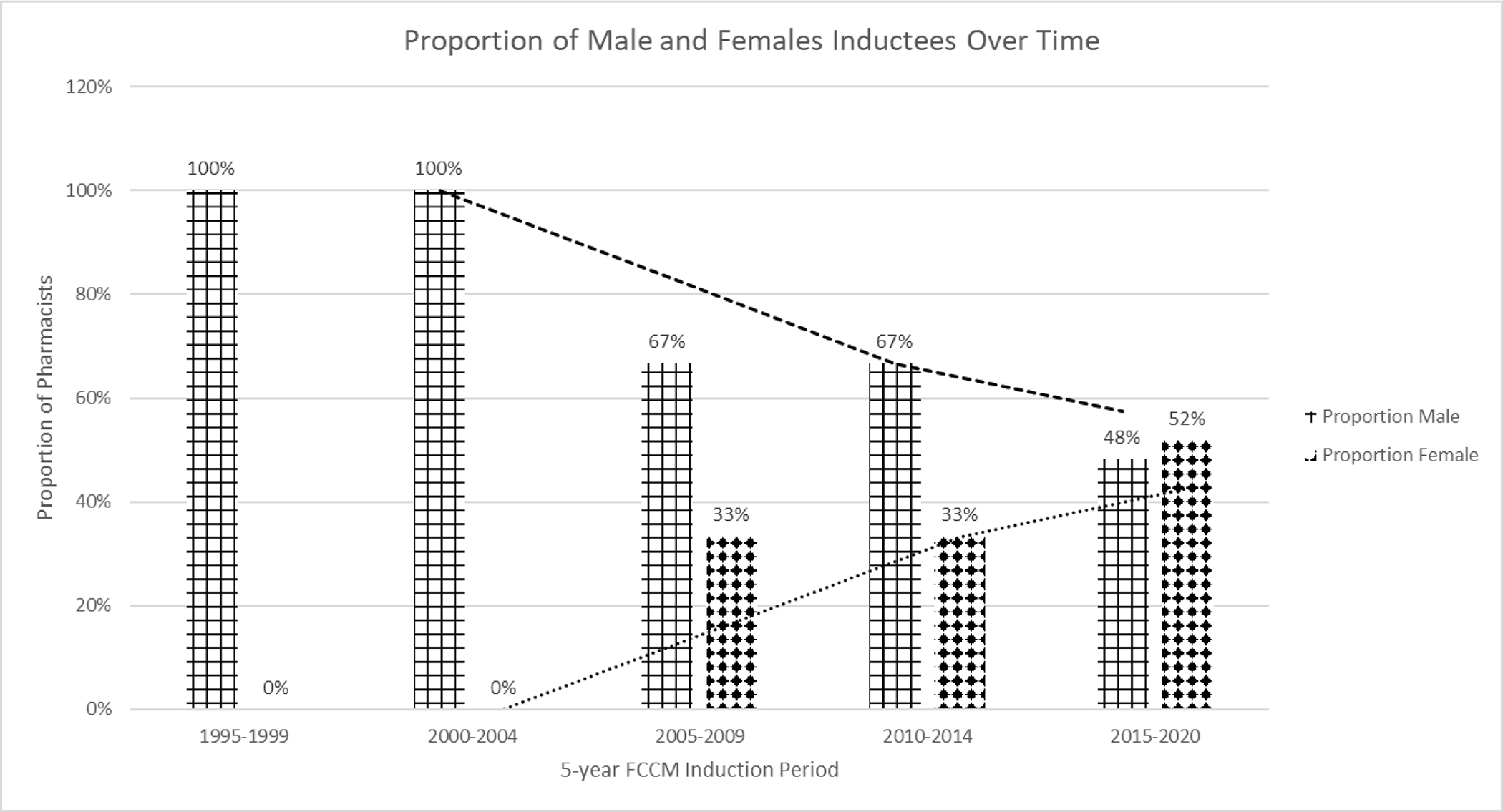

Of the 152 pharmacists designated FCCM, 134 (88%) were evaluable including 76 (57%) males and 58 (43%) females. Reasons for exclusion included MCCM (n=7; 5%), no data in Scopus (n=8; 6%) or no active pharmacist license (n=3; 2%). The majority of males and females practiced in the South (41% vs. 52%; p=0.3) and at an academic medical center (82% vs. 88%; p=0.4) (Table 1). Females practiced at institutions with more staffed beds than males (808 vs. 695; p= 0.0003). Year of FCCM convocation was between 2015 and 2020 for 46% of males and 67% for females (p=0.02) (Figure 1).

Table 1:

Demographic and publication rate and impact data stratified by gender

| All n=134 |

Male n=76 |

Female n=58 |

p-valueA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Region, no. (%) | 0.3 | |||

| South | 61 (46) | 31 (41) | 30 (52) | |

| Midwest | 37 (28) | 26 (34) | 11 (19) | |

| Northeast | 22 (16) | 12 (16) | 10 (17) | |

| West | 10 (7) | 6 (8) | 4 (7) | |

| Other | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 3 (5) | |

|

| ||||

| Hospital setting, no. (%)B | 0.4 | |||

| Academic | 113 (84) | 62 (82) | 51 (88) | |

| Community | 9 (8) | 5 (7) | 4 (7) | |

| Other/unknown | 12 (9) | 9 (12) | 3 (5) | |

|

| ||||

| Staffed hospital bedsB | 727 (466, 926) | 695 (436, 824) | 808 (547, 973) | 0.0003 |

|

| ||||

| Year of first publication | 2007 (2001, 2010) | 2005 (1999, 2009) | 2010 (2006, 2012) | 0.0002 |

|

| ||||

| Publications per pharmacist | 20 (10, 44) | 29 (14, 49) | 13 (7, 29) | 0.002 |

|

| ||||

| Publications per yearC | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | 1 (0.5, 3) | 0.05 |

|

| ||||

| Citations per pharmacist | 244 (99, 661) | 384 (133, 800) | 139 (61, 363) | 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| Hirsch index | 8 (5, 13) | 10 (6, 15) | 6 (3, 9) | 0.0005 |

Continuous data are reported as median (IQR)

Comparisons between male and female pharmacists designated FCCM; geographic region is proportion in the South

Data for pharmacists at a hospital practice site only

Calculated by dividing the total number publications by years since first publication

Figure 1:

FCCM convocation year of male and female pharmacists designated FCCM

Publication Rate and Impact for All Pharmacists Designated FCCM

A total of 4,436 publications were identified, and after removing duplicates (n=684; 15%), 3,752 publications were evaluable (Table 1). The oldest publication was from 1984 and the most recent was in 2021. The minimum number of publications per individual pharmacist was one, and the maximum was 198. Individual pharmacists produced 20 (10, 44) publications in their career and published 2 (1, 3) times per year. Pharmacists have generated 244 (99,661) citations and an h-index of 8 (5, 13).

Publication Rate and Impact for Pharmacists Designated FCCM Stratified by Gender

Male pharmacists had an earlier first publication year when compared to females (2005 vs. 2010; p=0.0002). Similarly, males produced a higher number of publications per individual pharmacist (29 vs. 13; p=0.002) and a similar number of publications per year (2 vs. 1; p=0.05). When comparing publication impact, males generated more citations (384 vs. 139; p=0.001) and had a higher h-index (10 vs. 6, p=0.0005).

Publication Rate and Impact Stratified by Gender for Pharmacists Designated FCCM from 2015 to 2020

82 pharmacists were designated FCCM from 2015 to 2020 including 39 males and 42 females. A similar proportion of males and females practiced in the South (41% vs. 50%; p=0.3) and at an academic hospital (90% vs. 90%; p=1). Year of first publication was earlier for males (2008 vs. 2010; p=0.005) and females had fewer publications (13 vs. 22; p=0.02), publications per year (1 vs. 2; p=0.08), citations (114 vs. 239; p=0.02) and a lower h-index (5 vs. 7; p=0.01).

Discussion

This study found female pharmacists designated FCCM practice in a similar geographic region in the United States and hospital setting. Publication rate and impact were higher amongst males than females when assessing all convocations years. Data stratification by convocation during 2015 to 2020 resulted in less disparity compared to all time periods, but differences remained. These findings must be considered within the construct of changing pharmacist demographics and an earlier year of first publication for males.

Differences in publication rate and impact may reflect an increasing proportion of female pharmacists joining the profession and achieving FCCM status within the last five years. The high proportion of female designees within this timeframe aligns with the expansion of females in pharmacy. These data may be used to encourage female authorship and participation in scholarly activities in pursuit of FCCM designation. This is the first study examining publication rate and impact between genders in critical care pharmacy. Similar studies have been conducted in other areas of pharmacy and medicine.

Two studies have described gender disparities in authorship or editorial board membership in selected pharmacy journals.6,7 Sarna and colleagues investigated the proportion and trend in gender ratios of 21 journal editorial boards in medicine, nursing, and pharmacy. The proportion of females increased by 12% (p<0.001) in editorial board membership and increased by 9% (p=0.067) in editorial board leadership in pharmacy journals from 1995 to 2016.6

Hoover and colleagues found an increase in the proportion of articles with women as the first author from 2007 to 2017 in all journals except one, with a significant increase throughout the decade (45.1% to 56.1%; p<0.001). This study differs from our study as it focuses only on first authorship, does not evaluate impact, and is not restricted to critical care pharmacy.7 Both articles demonstrate that females are underrepresented in academic pharmacy but that the gender gap is closing.

Mayer and colleagues described publication productivity differences in male and female urologists with a higher h-index in males compared to females (11.7 vs. 6.3, p<0.001).11 Purdy and colleagues reported that males had a higher h-index (5 vs. 3, p<0.001) and number of citations (OR 1.068) than females in emergency medicine.11 Pakpoor and colleagues identified a significant increase in the percentage of female neurologist authorship in three neurology journals over a 35-year period (p<0.01).12 These studies support our findings in a change over time in female representation in scholarly activity.

In 2022, a study by Mehta and colleagues examined gender disparities in critical care medicine between January 1994 and October 2020. It described the diversity of authors of publications from the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group in 1,205 individual authors of which 37% were women. Only 1.5% of authors were pharmacists. In total, 40.1% of publications had a female first author and 33.6% had a female last author. The proportion of female total authors increased by 3.8% each 5 years (p=0.006). This study does not examine publications by individual, number of citations, or impact. Additional studies are needed to describe gender disparities in impact and publication productivity in critical care medicine.

Our study has several limitations. It did not evaluate the quality of publication or the journal’s impact factor, but instead used citations and h-index as a surrogate marker. It did not include other factors of disparity such as race or age that may influence the results. Additionally, this study did not evaluate other areas of critical care pharmacy practice or influence such as faculty positions or involvement in postgraduate training in residency leadership or preceptorship. Further evaluations should focus on journal impact factor, place on the author list, and pharmacy subspecialty (e.g., medical, surgical, cardiac, cardiothoracic surgery, or neurologic critical care). It is possible publications were missed if pharmacists published under a married name or other name. Lastly, determination of gender was not self-reported and may not align with how the pharmacist identifies. We elected to use gender because an internet search was used and individuals may have represented themselves differently than their assigned sex at birth. Future directions could focus on evaluation of the reasons for/against pursuit of FCCM designation between males and females or the difference in convocation selection with applications received compared to applicants inducted.

Conclusion

There is significant gender disparity in publication rate and impact amongst pharmacists designated FCCM from 1988 to 2020. However, this disparity seems to be decreasing with time as the rate of females designated FCCM is increasing. This is consistent with an overall increase in the proportion of pharmacists who are female and deserves further exploration.

Key points:

-

What was already known

Gender disparities have been reported in medical subspecialties and within academic pharmacy.

A recent study of the Canadian Critical Care Trials Group publications showed an increase in the proportion of female authors, by 38% every five years.

No study has compared publication rate and impact between male and female critical care pharmacists.

-

What this study adds

This study describes 134 pharmacists that are designated Fellow of Critical Care Medicine (FCCM) by the American College of Critical Care Medicine with 76 (57%) males and 58 (43%) females.

This study aligns with previous reports of gender disparities in publication rates and impact among other specialties in medicine and academic pharmacy. Male pharmacists had an earlier first publication year, a higher number of publications, more citations, and a higher h-index.

A higher proportion of females have been designated FCCM in the most recent five-year period. Data stratification using this timeframe resulted in less disparity, but differences persisted.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Gagnon is supported in part by a National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant (1P20GM139745) and is a consultant for Lexicomp.

Footnotes

All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

These data have been presented in part at the 2022 Society of Critical Care Medicine’s virtual Annual Congress from April 18–21, 2022.

References

- 1.United States Census Bureau: Census data. Available at: https://www.census.gov/data.html. Accessed February 14, 2022.

- 2.Rudis MI, Brandl KM. Position paper on critical care pharmacy services. Society of Critical Care Medicine and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Task Force on Critical Care Pharmacy Services . Crit Care Med 2000;28(11):3746–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Society of Critical Care Medicine: Society of Critical Care Medicine 2019 Annual Report. Available at: https://www.sccm.org/Home. Accessed February 14, 2022.

- 4.Lat I, Paciullo C, Daley MJ, et al. Position paper on critical care pharmacy services (executive summary): 2020 update. Crit Care Med 2020; 48:1375–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sherman KM, Gagnon DJ. Benchmarking scholarly activity by pharmacists who are fellows within the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Explor 2021;3(9):e0520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sarna KV, Griffin T, Tarlov E, Gerber BS, Gabay MP, Suda KJ. Trends in gender composition on editorial boards in leading medicine, nursing, and pharmacy journals. J Am Pharm Assoc 2020;60(4):565–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoover RM, Aré A, Ludvigson K, Nguyen E. Trends in women’s authorship in pharmacy literature. J Am Pharm Assoc 2019;59(3):356–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scopus: Scopus Author Search. 2021. Available at: https://www.scopus.com/home.uri. Accessed February 2021.

- 9.AHA Hospital Statistics, 2018 Edition. 2018. Available at: https://www.aha.org/statistics/2016-12-27-aha-hospital-statistics-2018-edition. Accessed December 10, 2020.

- 10.Mayer EN, Lenherr SM, Hanson HA, et al. Gender differences in publication productivity among academic urologists in the United States. Urology 2017; 103:39–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Purdy ME, Zmuda BN, Owens AM, et al. Gender differences in publication in emergency medicine journals. Am J Emerg Med 2021;49:P338–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pakpoor J, Liu L, Yousem D. A 35-year analysis of sex differences in neurology authorship. Neurology 2018; 90: 472–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta S, Ahluwalia N, Heybati K, et al. Diversity of authors of publications from the Canadian critical care trials group. Crit Care Medicine 2022; 50(4):535–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]