Abstract

Introduction and hypothesis

We aim to review iatrogenic bladder and ureteric injuries sustained during caesarean section and hysterectomy.

Methods

A search of Cochrane, Embase, Medline and grey literature was performed using methods pre-published on PROSPERO. Eligible studies described iatrogenic bladder or ureter injury rates during caesarean section or hysterectomy. The 15 largest studies were included for each procedure sub-type and meta-analyses performed. The primary outcome was injury incidence. Secondary outcomes were risk factors and preventative measures.

Results

Ninety-six eligible studies were identified, representing 1,741,894 women. Amongst women undergoing caesarean section, weighted pooled rates of bladder or ureteric injury per 100,000 procedures were 267 or 9 events respectively. Injury rates during hysterectomy varied by approach and pathological condition. Weighted pooled mean rates for bladder injury were 212–997 events per 100,000 procedures for all approaches (open, vaginal, laparoscopic, laparoscopically assisted vaginal and robot assisted) and all pathological conditions (benign, malignant, any), except for open peripartum hysterectomy (6,279 events) and laparoscopic hysterectomy for malignancy (1,553 events). Similarly, weighted pooled mean rates for ureteric injury were 9–577 events per 100,000 procedures for all hysterectomy approaches and pathologies, except for open peripartum hysterectomy (666 events) and laparoscopic hysterectomy for malignancy (814 events). Surgeon inexperience was the prime risk factor for injury, and improved anatomical knowledge the leading preventative strategy.

Conclusions

Caesarean section and most types of hysterectomy carry low rates of urological injury. Obstetricians and gynaecologists should counsel the patient for her individual risk of injury, prospectively establish risk factors and implement preventative strategies.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00192-022-05339-7.

Keywords: Bladder, Ureter, Caesarean, Hysterectomy, Iatrogenic, Injury

Introduction

Iatrogenic injury of the bladder or ureter is a known complication of abdominal, pelvic or vaginal surgery. Potential sequelae include haemorrhage, sepsis, renal loss and death [1–3]. The majority of such injuries occur secondary to caesarean section and hysterectomy [2, 4, 5], with a rising proportion now due to ureteroscopy [6, 7]. However, there remains great variation in the estimation of the frequency of urological injury during these major obstetric and gynaecological procedures, which limits the mandate for quality improvement exercises. Therefore, the objective of this review is to determine the incidence of urological injury during caesarean section and each type of hysterectomy.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

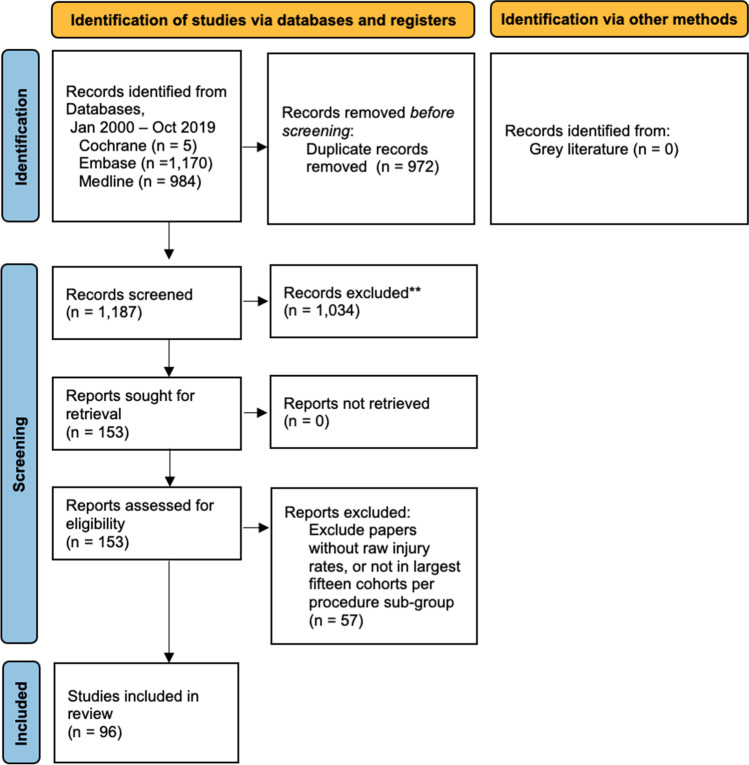

Systematic searches were performed of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Embase and Medline. Searches were performed by Title or Abstract, utilising keywords and Boolean operators as follows: (obstetric, gynaecolog*, gynecolog*, caesarean OR hysterectomy) AND (urolog*, kidney, renal, ureter, bladder OR urethra) AND (iatrogenic, accidental, inadvertent, injur* OR trauma). Grey literature was also searched and eligible, by review of the above search results, bibliographies of retrieved articles and proceedings of the 2010–2019 annual scientific conventions of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons. Inclusion criteria were agreed upon by all authors. Our method for identifying and evaluating data complied with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses criteria [8] (Appendix 1, Fig. 1). This included pre-publication of our intended analysis on PROSPERO (CRD42020161389). Note that although this protocol was intended to restrict inclusion to studies of ≥100 women, this was later reduced to ≥50 women, to reduce instances where identification of insufficient studies precluded meta-analysis. After protocol publication, preventative measures was demoted to a secondary outcome, to allow the study to focus on injury incidence as the sole primary outcome. Identified studies were screened by title and abstract, followed by full-text review. Articles then progressed to data extraction, including review of references. Two independent authors performed study screening and data extraction using a pre-defined form, with a third author involved for instances of disagreement (Appendix 2). Data extraction was performed twice to confirm accuracy. The final list of included articles was determined by compliance with the inclusion criteria and with the consensus of all authors.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram. **Based on title/abstract screen against study eligibility criteria

Study eligibility

Study eligibility was determined utilising the patient population, intervention, comparator, outcome and study (PICOS) method [9]. Eligible studies reported cohorts of ≥50 women (P) undergoing open or laparoscopic pelvic or abdominal surgery by an obstetrician/gynaecologist (I), were not required to have a comparator cohort (C) and stated raw incidence of iatrogenic injury to the urinary bladder or ureter (O). Eligible publications were original full-length articles, published in English between 01 January 2000 and 20 October 2019 (S). All databases and sources were last searched on 30 November 2019. Studies were collated and analysed separately based on procedure type (caesarean section, hysterectomy), access (open trans-abdominal, open vaginal, laparoscopic trans-abdominal, laparoscopically assisted vaginal, vaginal only, robot assisted) and histology (benign, malignant, any). Studies were ranked by cohort size. When >15 studies were identified within a given sub-group, only the largest 15 studies were included. This limitation, not prespecified in the Prospero protocol, was to ensure that meta-analyses were of manageable size.

Intended analyses

The primary outcomes were the incidence of iatrogenic bladder and ureteric injury during caesarean section and each type of hysterectomy. Secondary outcomes were identified risk factors for injury and suggested preventative measures.

Qualitative summary was intended for all data, tabulating the key features of included studies. Raw proportions of each injury type were combined in a random effects meta-analysis using the R package “meta” [10]. Studies with zero events were not excluded from this pooled analysis. All analyses were two-tailed and significance was assessed at the 5% alpha level. Injury rates were reported as events per 100,000 procedures.

Bias

The authors did not anticipate identifying any randomised controlled trials. Consequently, risk of bias was assessed with the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale, in accordance with the Cochrane Handbook [11, 12]. Each study was independently reviewed by two reviewers (GW, NK) against pre-defined criteria (Appendix 3). Instances of disagreement were resolved by consensus. Risk of bias was not used to exclude studies.

Results

Initial database searches returned 2,159 articles. After removing 972 duplicate results and a further 1,034 irrelevant publications based on title and abstract review, 153 articles were retrieved for full text review (Appendix 4). After excluding ineligible studies and applying the pre-specified limitation of the 15 largest cohorts in each procedure sub-category, 96 eligible articles were included, describing caesarean section or hysterectomy in 130 cohorts, totalling 1,741,894 women (Fig. 1, Table 1) [3, 13–107].

Table 1.

Enrolled studies

| Year | Author | Nation | Procedure | Design | Sites | Cases | Bladder injuries | Ureteric injuries | Age | BMI | Exclusions | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Conde-Agudelo [13] | Colombia | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Prospective | Single | 867 | 3 | 1 | 43 | – | Cancer | 45a |

| 2001 | Cosson et al. [14] | France | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Multiple | 166 | 3 | 0 | – | – | Cancer | – |

| Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Multiple | 1,248 | 11 | 0 | – | – | Cancer | – | |||

| 2001 | Leanza et al.[15] | Italy | Abdominal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 2,765 | 4 | 4 | – | – | – | – |

| Vaginal hysterectomy (Mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 373 | 2 | 1 | – | – | – | – | |||

| 2001 | Liapis et al. [16] | Greece | Abdominal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 3,741 | – | 13 | – | – | – | – |

| Vaginal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 1,381 | – | 0 | – | – | – | – | |||

| 2001 | Mathevet et al. [17] | France | Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 3,076 | 54 | 1 | 48 | – | – | – |

| 2001 | Milad et al. [18] | USA | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 105 | 3 | 0 | 47 | – | Simultaneous procedures | – |

| 2001 | Seman et al. [19] | Australia | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 436 | – | 6 | – | – | – | – |

| 2002 | Wattiez et al. [20] | France | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 1,647 | 19 | 6 | – | – | Total uterine prolapse, cancer | – |

| 2003 | Boukerrou et al. [21] | France | Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Prospective | Multiple | 741 | 10 | 0 | 46 | – | – | – |

| 2003 | Khashoggi [22] | Saudi Arabia | Caesarean section | Retrospective | Single | 290 | 3 | 0 | 34 | 31 | <2 prior LSCS, missing data | – |

| 2003 | Shen et al. [23] | Taiwan | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 2,702 | 11 | 4 | 46 | – | – | – |

| 2004 | Dorairajan et al. [24] | India | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 2,095 | 4 | 5 | – | – | – | – |

| Abdominal hysterectomy (malignant) | Retrospective | Single | 617 | 3 | 1 | – | – | – | – | |||

| Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 3,270 | 10 | 0 | – | – | – | – | |||

| 2004 | Koh et al. [25] | Taiwan | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 2,006 | 5 | 0 | 45 | – | – | 1b |

| 2004 | Parkar et al. [26] | Egypt | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 149 | 6 | 0 | – | – | Missing data | – |

| 2004 | Rashid and Rashid [27] | Saudi Arabia | Caesarean section | Retrospective | Single | 308 | 4 | – | 35 | 34 | <5 prior LSCS, incomplete records | – |

| 2004 | Steed et al. [28] | Canada | Abdominal hysterectomy (malignant) | Prospective | Single | 205 | 7 | 1 | 44 | – | Lymph node metastases | 21a |

| 2005 | Chang et al. [29] | Taiwan | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 225 | 2 | 0 | 46 | 23 | – | 12c |

| 2005 | Phipps et al. [30] | USA | Caesarean section | Retrospective | Single | 14,757 | 42 | – | 31 | 32 | – | – |

| 2005 | Tae Kim et al. [31] | South Korea | Abdominal hysterectomy (malignant) | Retrospective | Single | 338 | 0 | 1 | 43 | 23 | – | – |

| 2005 | Vakili et al. [32] | USA | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Prospective | Multiple | 278 | 7 | 6 | 42 | 31 | Cancer | – |

| 2006 | Akyol et al. [33] | Turkey | Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 886 | 22 | 1 | 53 | – | Nil | – |

| 2006 | Bojahr et al. [34] | Germany | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 1,706 | 3 | 1 | 46 | 25 | Cancer, endometriosis | – |

| 2006 | Dauleh et al. [35] | Qatar | Caesarean section | Retrospective | Single | 21,337 | 16 | 4 | – | – | – | – |

| 2006 | Ghezzi et al. [36] | Italy | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (malignant) | Prospective | Multiple | 101 | 1 | 0 | 63 | 26 | Severe cardiorespiratory disease, metastases | 24b |

| 2006 | Kafy et al. [37] | Canada | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 1,349 | 2 | 1 | 47 | 26 | Peripartum or malignant hysterectomy | – |

| Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 223 | 2 | 0 | 47 | 28 | Peripartum or malignant hysterectomy | – | |||

| 2006 | Mahdavi et al. [38] | USA | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 159 | 1 | 0 | 54 | 26 | – | – |

| 2006 | Roman [39] | New Zealand | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 418 | 0 | 0 | 46 | – | – | – |

| 2006 | Sharon et al. [40] | Israel | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 480 | 1 | 1 | 50 | – | Uterus size >16 weeks, PID | – |

| 2007 | Johnston et al. [41] | Australia | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Prospective | Multiple | 69 | 2 | 0 | – | – | – | – |

| 2007 | Karaman et al. [42] | Turkey | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Prospective | Multiple | 542 | 0 | 0 | – | – | Cancer, suspicious adnexal mass, uterine size >16 weeks | – |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Prospective | Multiple | 552 | 0 | 0 | – | – | Cancer, suspicious adnexal mass, uterine size >16 weeks | – | |||

| 2007 | Leonard et al. [43] | France | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 1,300 | – | 4 | 48 | 23 | POP, SUI | – |

| 2007 | Nawaz et al. [44] | Pakistan | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 3,910 | 21 | 14 | – | – | – | – |

| Caesarean section | Retrospective | Single | 12,567 | 31 | 2 | – | – | – | – | |||

| Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 481 | 9 | 2 | – | – | – | – | |||

| 2007 | Ng and Chern [45] | Singapore | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 503 | 2 | 1 | 47 | 19 | – | – |

| 2007 | O'Hanlan et al. [46] | USA | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Multiple | 830 | 13 | 10 | 50 | 28 | – | – |

| 2007 | Soong et al. [47] | Taiwan | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 7,725 | 30 | 8 | – | – | – | – |

| 2007 | Tian et al. [48] | Taiwan | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 2,174 | 10 | 2 | – | – | Simultaneous diagnostic procedures | – |

| 2007 | Xu et al. [49] | China | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (malignant) | Retrospective | Single | 317 | 9 | 5 | – | – | – | 6b |

| 2008 | Chen et al. [50] | China | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (malignant) | Retrospective | Single | 290 | 5 | 1 | 43 | – | – | 46a |

| 2008 | Kyung et al. [51] | South Korea | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 1,178 | 15 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| 2009 | Ark et al. [52] | Turkey | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 367 | 1 | 0 | 51 | 32 | Cancer, prior surgery, <2 finger vaginal width, POP | – |

| 2009 | Chopin et al. [53] | France | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 1,460 | 14 | 3 | 48 | 24 | Cancer, POP, SUI, missing data | – |

| 2009 | Donnez et al. [54] | Belgium | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 409 | 3 | 0 | – | – | – | 24b |

| Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 906 | 4 | 3 | – | – | – | 24c | |||

| 2009 | Ibeanu et al. [55] | USA | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Prospective | Multiple | 544 | 12 | 9 | – | – | Cancer, prior hysterectomy | – |

| Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Prospective | Multiple | 61 | 2 | 0 | – | – | Cancer, prior hysterectomy | – | |||

| 2009 | Juillard et al. [56] | USA | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Multiple | 172,344 | 1,239 | 19 | 46 | – | – | – |

| 2009 | Lafay Pillet et al. [57] | France | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 1,501 | 15 | 5 | 48 | 24 | Subtotal hysterectomy, cancer | – |

| 2009 | Lee et al. [58] | Hong Kong | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 512 | 3 | 0 | 45 | – | Cancer, uterine size >18 weeks | 1.5b |

| 2009 | Rahman et al. [59] | Saudi Arabia | Caesarean section | Retrospective | Single | 7,708 | 34 | 0 | 29 | 30 | Simultaneous hysterectomy | 1.5b |

| 2009 | Yan et al. [60] | China | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (malignant) | Retrospective | Single | 117 | 6 | 1 | 41 | – | – | – |

| 2010 | Gungorduk et al. [61] | Turkey | Caesarean section | Retrospective | Single | 56,799 | 76 | – | – | – | Simultaneous hysterectomy | 1.5b |

| 2010 | Wang et al. [62] | Australia | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Multiple | 574 | 12 | 2 | – | – | Missing data | 1.5b |

| 2010 | Wright et al. [63] | USA | Abdominal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Multiple | 578,179 | 6,178 | 711 | – | – | Cancer | – |

| Peripartum hysterectomy | Retrospective | Multiple | 4,967 | 458 | 33 | – | – | Cancer | – | |||

| 2011 | Anpalagan et al. [64] | Australia | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Multiple | 87 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | 1.5b |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Multiple | 991 | 14 | 0 | – | – | – | 1.5b | |||

| 2011 | Brummer et al. [65] | Finland | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Prospective | Multiple | 1,255 | 11 | 4 | – | – | Nil | – |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Prospective | Multiple | 1,679 | 17 | 5 | – | – | Nil | – | |||

| Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Prospective | Multiple | 2,345 | 14 | 1 | – | – | Nil | – | |||

| 2011 | Doganay et al. [66] | Turkey | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 4,398 | 30 | 8 | 54 | – | Cancer, other procedures, clotting disorders | – |

| Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 1,944 | 7 | 2 | 54 | – | Cancer, other procedures, clotting disorders | – | |||

| 2011 | Jung and Lee [67] | South Korea | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 458 | 0 | 0 | 49 | 25 | Cancer | – |

| 2011 | Kavallaris et al. [68] | Germany | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Multiple | 1,255 | 11 | 2 | 46 | 27 | – | – |

| 2011 | Song et al. [69] | South Korea | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 2,012 | 26 | 1 | 45 | 24 | – | 80a |

| 2012 | Al-Shahrani et al. [70] | Saudi Arabia | Caesarean section | Retrospective | Single | 10,765 | 24 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2012 | Cho et al. [71] | South Korea | Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 686 | 3 | 0 | 45 | 24 | Cancer, ovary >5 cm | 0.25b |

| 2012 | Grosse-Drieling et al. [72] (71) | Germany | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 1,584 | 4 | 1 | 46 | 25 | Cancer | – |

| 2012 | Khan et al. [73] | Pakistan | Peripartum hysterectomy | Retrospective | Single | 218 | 6 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| 2012 | Kobayashi et al. [74] | Japan | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 1,253 | 6 | 4 | 46 | 23 | Nil | – |

| 2012 | Lee et al. [75] | South Korea | Abdominal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 6,792 | 19 | 7 | – | – | – | 6b |

| Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 2,891 | 8 | 7 | – | – | – | 6b | |||

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 1,625 | 0 | 0 | – | – | – | 6b | |||

| Vaginal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 5,182 | 16 | 5 | – | – | – | 6b | |||

| 2012 | Mueller et al. [76] | Germany | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 567 | 4 | 1 | 48 | 26 | Simultaneous POP surgery, cancer | – |

| 2012 | Rao et al. [77] | China | Caesarean section | Retrospective | Single | 6,732 | 8 | 1 | – | – | – | 5b |

| 2012 | Sandberg et al. [78] | USA | Abdominal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 644 | 5 | 0 | – | – | Peripartum hysterectomy | – |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 1,011 | 7 | 4 | – | – | Peripartum hysterectomy | – | |||

| Robot–assisted hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 77 | 0 | 1 | – | – | Peripartum hysterectomy | – | |||

| Vaginal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 250 | 2 | 0 | – | – | Peripartum hysterectomy | – | |||

| 2012 | Teerapong et al. [79] | Thailand | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 101 | 4 | 3 | – | – | – | 1.5b |

| 2012 | Tuuli et al. [80] | USA | Caesarean section | RCT | Single | 258 | 0 | 0 | 27 | – | Emergency LSCS, prior surgery, gestation <32 weeks | 1b |

| 2013 | Choi et al. [81] | South Korea | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 250 | 3 | 0 | 49 | 23 | Cancer | – |

| 2013 | Mäkinen et al. [82] | Finland | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Multiple | 7,130 | 38 | 13 | 49 | 26 | – | – |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Multiple | 4,113 | 47 | 31 | 48 | 25 | – | – | |||

| Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Multiple | 4,146 | 16 | 1 | 57 | 26 | – | – | |||

| 2013 | Sheth [83] | India | Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Multiple | 536 | 5 | 0 | – | – | <2 prior LSCS, POP, adhesions, uterus >20-week size, tubo-ovarian pathological condition | – |

| 2014 | Dutta and Dutta [84] | India | Abdominal hysterectomy (mixed) | Prospective | Single | 1,450 | 6 | 1 | – | – | – | – |

| 2014 | Han et al. [85] | China | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (malignant) | Prospective | Single | 176 | 0 | 6 | 45 | – | – | – |

| 2014 | Nguyen et al. [86] | USA | Robot-assisted hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Multiple | 229 | 0 | 0 | 58 | 33 | Convert robot-assisted to laparotomy | 1b |

| 2014 | Park and Nam [87] | South Korea | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (malignant) | Retrospective | Single | 260 | 3 | 1 | 48 | 23 | Nil | – |

| 2014 | Zia and Rafique [88] | Saudi Arabia | Caesarean section | Retrospective | Single | 519 | 6 | 0 | 33 | – | Placental adhesion disorders, <28 weeks gestation | – |

| 2015 | Garabedian et al. [89] | France | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (malignant) | Retrospective | Single | 170 | 3 | 2 | 47 | 26 | – | 48a |

| 2015 | Kaplanoglu et al. [90] | Turkey | Caesarean section | Retrospective | Single | 2,460 | 28 | 0 | 30 | – | Syrian refugees, lack of follow-up | 1.5b |

| 2015 | Tan-Kim et al. [91] | USA | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 140 | 5 | 2 | – | – | – | 42c |

| 2016 | Dolanbay et al. [92] | Turkey | Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 184 | 2 | 0 | 46 | – | – | – |

| 2016 | Kang et al. [93] | South Korea | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 746 | 6 | 3 | 46 | – | Advanced malignancy | 1b |

| 2016 | Tinelli et al. [94] | Italy | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (malignant) | Retrospective | Single | 110 | 3 | 4 | 62 | 37 | Stage III or IV cancer, prior chemo- or radio-therapy, systemic infection, uterus >12-week size, significant cardiorespiratory disease, unclear follow-up | 38c |

| 2017 | Clave and Clave [91] | France | Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 1,000 | 12 | 0 | 51 | 26 | – | 12b |

| 2017 | Lim et al. [96] | South Korea | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 482 | 1 | 0 | 49 | 24 | Prior abdominal surgery, simultaneous surgery | – |

| 2017 | Satitniramai and Manonai [97] | Thailand | Abdominal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 13,288 | 36 | 18 | – | – | – | – |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 2,131 | 4 | 6 | – | – | – | – | |||

| 2017 | Singla et al. [98] | India | Peripartum hysterectomy | Retrospective | Single | 194 | 13 | 0 | – | – | – | – |

| 2017 | Yaman Tunc et al. [99] | Turkey | Caesarean section | Retrospective | Single | 1,133 | 14 | 0 | 31 | – | <24 weeks gestation, multiparous, prior surgery, stillbirth, missing data | – |

| 2018 | Benson et al. [100] | USA | Abdominal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Multiple | 355,812 | 3,760 | 1,686 | – | – | Cancer | – |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Multiple | 31,389 | 830 | 158 | – | – | Cancer | – | |||

| Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Multiple | 123,139 | 1,133 | 61 | – | – | Cancer | – | |||

| 2018 | Blackwell et al. [3] | USA | Abdominal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Multiple | 99,693 | – | 953 | – | – | Exenteration, prior hydro or ureteric stricture | 12d |

| Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Multiple | 27,158 | – | 245 | – | – | Exenteration, prior hydro or ureteric stricture | 12d | |||

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Multiple | 16,584 | – | 182 | – | – | Exenteration, prior hydro or ureteric stricture | 12d | |||

| Peripartum hysterectomy | Retrospective | Multiple | 1,528 | – | 21 | – | – | Exenteration, prior hydro or ureteric stricture | 12d | |||

| Vaginal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Multiple | 45,002 | – | 100 | – | – | Exenteration, prior hydro or ureteric stricture | 12d | |||

| 2018 | Koroglu et al. [101] | Turkey | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 504 | 2 | 1 | 49 | 32 | Abscess, PID, POP, prior surgery, cancer, missing data | – |

| 2018 | Li et al. [102] | China | Abdominal hysterectomy (malignant) | Retrospective | Single | 551 | 5 | 12 | – | – | LUTS, loss to follow-up | 42a |

| 2018 | Petersen et al. [103] | USA | Abdominal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 940 | 4 | 5 | 50 | 33 | – | 3b |

| Laparoscopic hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 782 | 3 | 4 | 50 | 33 | – | 3 | |||

| Robot-assisted hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 1,088 | 3 | 7 | 50 | 33 | – | 3b | |||

| Vaginal hysterectomy (mixed) | Retrospective | Single | 304 | 0 | 1 | 50 | 33 | – | 3b | |||

| 2019 | Inan et al. [101] | Turkey | Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 547 | 7 | 4 | 49 | 26 | Cancer, other procedures | – |

| 2019 | Otkjaer et al. [105] | Denmark | Caesarean section | Retrospective | Multiple | 4,039 | 12 | 0 | 31 | 24 | Gestation <37 weeks, infant <2.5 kg, maternal comorbidity, emergency LSCS | – |

| 2019 | Sirota et al. [105] | USA | Vaginal hysterectomy (benign) | Retrospective | Single | 452 | 13 | 3 | 57 | – | POP | – |

| 2019 | Sondgeroth et al. [107] | USA | Caesarean section | Retrospective | Single | 5,144 | 14 | 0 | 27 | – | Non-singleton | – |

LSCS lower section caesarean section, LUTS lower urinary tract symptoms, PID pelvic inflammatory disease, POP pelvic organ prolapse, SUI stress urinary incontinence

aMedian

bPlanned, not measured

cMean

dMethodology searched for readmissions with bladder or ureteric injuries within 12 months of primary procedure

One study was a randomised controlled trial [80], whereas all the others were non-randomised observational studies. All but 12 studies were retrospective in nature. Mean or median age was reported by 67 of the 130 cohorts and ranged from 27 to 63 years. Similarly, mean or median body mass index was available for 42 cohorts, and varied from 19 to 37 kg/m2. Average American Society of Anaesthesiology score or Charlson Comorbidity Index were available for only 4 [34, 36, 95, 103] or 3 studies [3, 56, 87] respectively. Meta-analyses of bladder and ureteric injury rates are presented in Table 2 and Appendix 5.

Table 2.

Meta-analyses by procedure sub-group

| Procedure | Bladder | Ureteric | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies identified | Studies reporting bladder injury rate | Patients (n) | Weighted pooled mean injury rates; events per 100,000 procedures | 95% CI; events per 100,000 procedures | Studies reporting ureteric injury rate | Patients (n) | Weighted pooled mean injury rates; events per 100,000 procedures | 95% CI; events per 100,000 procedures | |

| Caesarean section | 15 | 15 | 144,558 | 267 | 190–343 | 11 | 62,187 | 9 | 0–18 |

| Hysterectomy | |||||||||

| Open abdominal (benign) | 15 | 15 | 550,784 | 641 | 445–837 | 15 | 550,784 | 255 | 6–446 |

| Open abdominal (any histology) | 9 | 7 | 604,058 | 473 | 46–900 | 9 | 707,492 | 261 | 33–489 |

| Open abdominal (malignant) | 4 | 4 | 1,711 | 614 | 0–1,302 | 4 | 1,711 | 577 | 0–1,191 |

| Open abdominal (peripartum) | 4 | 3 | 5,379 | 6,279 | 1,731–10,826 | 4 | 6,907 | 666 | 178–1,153 |

| Vaginal (benign) | 15 | 15 | 144,856 | 878 | 635–1,120 | 15 | 144,856 | 39 | 23–55 |

| Vaginal (any histology) | 6 | 4 | 6,109 | 295 | 156–435 | 6 | 52,492 | 122 | 5–239 |

| Laparoscopic (benign) | 15 | 14 | 48,814 | 997 | 401–1,594 | 15 | 50,114 | 262 | 126–399 |

| Laparoscopic (any histology) | 13 | 11 | 10,002 | 375 | 173–577 | 13 | 27,022 | 417 | 127–707 |

| Laparoscopic–(malignant) | 8 | 8 | 1,541 | 1,553 | 610–2,496 | 8 | 1,541 | 814 | 222–1,406 |

| Laparoscopic–assisted vaginal (benign) | 14 | 14 | 12,077 | 445 | 190–699 | 14 | 12,077 | 87 | 26–147 |

| Laparoscopic assisted vaginal (any histology) | 9 | 8 | 13,530 | 506 | 248–764 | 9 | 40,688 | 186 | 0–415 |

| Robot-assisted (any histology) | 3 | 3 | 1,394 | 212 | 0–486 | 3 | 1,394 | 398 | 0–939 |

CI confidence interval,

Caesarean section

As >15 caesarean section cohorts were identified, the largest 15 were selected, representing 144,816 women [22, 27, 30, 35, 44, 59, 61, 70, 77, 80, 88, 90, 99, 105, 107]. In total, 312 bladder and 7 ureteric injuries were reported. Weighted pooled mean injury rates were 267 and 9 events per 100,000 procedures respectively.

Open abdominal hysterectomy (benign histology)

The 15 largest cohorts were selected, comprising 550,784 women [13, 14, 24, 32, 37, 44, 54–56, 64–66, 82, 91, 100]. Cumulatively, 5,138 bladder and 1,768 ureteric injuries were detected. Weighted pooled mean injury rates were 641 and 255 events per 100,000 cases respectively.

Open abdominal hysterectomy (malignant histology)

Four cohorts were found, representing 1,711 women [24, 28, 31, 102]. Together, 15 bladder and 15 ureteric injuries were described. Weighted pooled mean injury rates were 614 and 577 events per 100,000 cases respectively.

Open abdominal hysterectomy (any histology)

Nine cohorts were located, totalling 707,492 women [3, 15, 16, 63, 75, 78, 84, 97, 103]. Summatively, 6,252 bladder and 1,712 ureteric injuries were reported. Weighted pooled mean injury rates were 473 and 261 events per 100,000 cases respectively.

Open abdominal hysterectomy (peripartum)

Amongst 6,907 women in four cohorts, 477 bladder and 55 ureteric injuries were reported in total [3, 63, 73, 98]. Weighted pooled mean injury rates were 6,279 and 666 events per 100,000 cases, respectively.

Vaginal hysterectomy (benign histology)

The largest 15 cohorts were selected, comprising 144,856 women [14, 17, 21, 24, 33, 44, 54, 65, 66, 71, 82, 83, 95, 100, 106]. In aggregate, 1,323 bladder and 75 ureteric injuries occurred. Weighted pooled mean injury rates were 878 and 39 events per 100,000 cases respectively.

Vaginal hysterectomy (any histology)

From the six identified cohorts representing 52,492 women, 20 bladder and 100 ureteric injuries were noted [3, 15, 16, 75, 78, 103]. Weighted pooled mean injury rates were 295 and 122 events per 100,000 cases respectively.

Laparoscopic hysterectomy (benign histology)

Within the 15 largest cohorts constituting 50,114 women, 988 bladder and 222 ureteric injuries were observed [20, 34, 42, 43, 53, 57, 62, 64, 65, 72, 76, 82, 100, 101, 104]. Weighted pooled mean injury rates were 997 and 262 events per 100,000 cases respectively.

Laparoscopic hysterectomy (malignant histology)

Eight cohorts were found, comprising 1,541 women [36, 49, 50, 60, 85, 87, 89, 94]. Thirty bladder and 20 ureteric injuries were reported. Weighted pooled mean injury rates were 1,553 and 814 events per 100,000 cases respectively.

Laparoscopic hysterectomy (any histology)

Thirteen cohorts incorporating 27,022 women were identified, with 44 bladder and 221 ureteric injuries recorded [3, 19, 38, 40, 45, 46, 74, 75, 78, 93, 96, 97, 103]. Weighted pooled mean injury rates were 375 and 417 events per 100,000 cases respectively.

Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (benign)

Within 14 cohorts totalling 12,077 women, 65 bladder and 13 ureteric injuries were detailed [18, 29, 37, 41, 42, 47, 52, 55, 58, 67, 68, 79, 81, 92]. Weighted pooled mean injury rates were 445 and 87 events per 100,000 cases respectively.

Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy (any histology)

Nine cohorts were identified, representing 40,688 women. A total of 81 bladder and 260 ureteric injuries were recorded [3, 23, 25, 26, 39, 48, 51, 69, 75]. Weighted pooled mean injury rates were 506 and 186 events per 100,000 cases respectively.

Robot-assisted hysterectomy (any histology)

Three cohorts were found, constituting 1,394 women [78, 86, 103]. Together, 3 bladder and 8 ureteric injuries were noted. Weighted pooled mean injury rates were 212 and 398 events per 100,000 cases respectively.

Risk factors for urological injury

Fifty-two studies identified one or more risk factors for bladder or ureteric injury (Appendix 6). In descending order of frequency, the most common elements were surgeon inexperience or low volume (18 studies), prior caesarean section (17), other previous pelvic surgery (14), adhesions (10), large uterus or tumour (10), endometriosis (8), cancer (5), radiotherapy (5), above average haemorrhage (5), low or high body mass index (5), placental adhesion disorder (4), concomitant surgery (4) and emergency procedure (2). Note that “surgeon inexperience or low volume” was self-defined by each study, and included undefined [28, 34, 49, 50, 59, 62, 77, 78, 93, 96], a surgical trainee [97], a consultant with <8 years’ experience [41] or having been primary operator for a given hysterectomy approach for fewer than 20 [23], 30 [40, 82], 50 [43, 87] or 100 cases [57].

Preventing urological injury

Strategies to reduce the risk of bladder or ureteric injury during caesarean section or hysterectomy were promoted by 35 studies (Appendix 7). From most to least common, recommended measures included improved anatomical knowledge (12 studies), strong uterine traction (12), careful dissection generally (9), prophylactic identification of ureters (8), bladder distension with fluid to clarify planes (7), avoiding diathermy near ureters (6), actively dissecting (as opposed to blunt traction) the bladder away from uterus (3), urethral catheterisation at the start of the case (3), prophylactic ureteric catheters/stents (3) and shielding the bladder with retractors (2).

Assessment of bias

The Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale suggested that the risk of bias was intermediate (46 studies) or high (35 studies) for most of the 96 works identified (Appendix 8). Key methodological and governance information was frequently absent, including typical post-operative follow-up (missing in 70% of studies), financial disclosure (missing in 73%), conflict of interest (missing in 53%) and ethics approval (missing or explicitly not present in 52%). Eighty four of the 96 studies were retrospective and therefore at an increased risk of selection bias. Publication bias was not assessed, given the studies’ heterogenous methodology and array of procedure sub-types.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this represents the largest systematic review to date of urological injury during major obstetric and gynaecological surgery. For clinicians performing caesarean section or hysterectomy, these findings may aid their daily practice in three ways. First, the pooled mean injury incidence may aid in counselling patients on the risk of bladder or ureteric injury for caesarean section or their specific surgical approach to hysterectomy. Our findings suggest that rates of bladder and ureteric injury are low for caesarean section and most approaches to hysterectomy. It is clear that both bladder and ureteric injury risk are highest during peripartum and laparoscopic radical hysterectomy. We believe that for peripartum hysterectomy this relates to poor visibility from haemorrhage from the gravid uterus and to placental invasion disorders, which may distort anatomical planes and invade the bladder, and for malignant hysterectomy to the desire to dissect widely to achieve negative margins and challenges from tumour infiltration. Analyses between tumour stage and injury incidence were not performed. Second, the collated risk factors can aid in the pre-operative assessment of a specific patient’s risk of urological injury. This information may be used to involve a senior surgeon, prophylactically identify and safeguard the ureters, refer to a tertiary centre or employ other cautionary steps. Third, the advocated preventative strategies can be both incorporated into routine practice and utilised more intensively in settings of known increased risk, as identified above.

This review’s relevance is underlined by the ongoing high volume and changing surgical approaches of major obstetric and gynaecological surgery. Globally, there is a trend towards more caesarean sections [108], with >30 million performed annually, comprising >20% of all births. Well over 1 million hysterectomies are performed annually [109], although the incidence is slowly declining in most [110, 111] but not all nations [112]. Simultaneously, as with other specialties, the approach to hysterectomy continues to shift towards minimally invasive means. Twenty years ago, abdominal (open) hysterectomy was the most common technique in both developed and developing nations [82, 110, 111, 113, 114]. From this baseline, minimally invasive approaches are now the most common in developed nations. Robot-assisted hysterectomy is the most common approach in the United States of America [115], laparoscopic hysterectomy predominates in Australia [114], Denmark [111] and Taiwan [113], whereas the vaginal approach is customary in Austria [116]. In developing nations, abdominal hysterectomy remains the norm [117].

Some authors recommended preventative strategies of routine cystoscopy (often with intravenous indigo carmine [3, 15, 23, 32, 40, 41, 43, 45, 51, 55, 93]) or prophylactic placement of ureteric stents. However, the evidence suggests that neither of these might be sufficiently sensitive or cost effective. Intra-operative cystoscopy seems a logical precaution, allowing prompt inspection for haematuria, intact urothelium, ureteric jets and blood from the ureteric orifices. However, where practised, cystoscopy is diagnostic and not preventative, being performed at the end of the gynaecological procedure to detect an injury that has already occurred. Furthermore, cystoscopy has low sensitivity for both bladder [91] and ureteric [19, 78, 91] injuries. Regarding prophylactic stents, randomised controlled trials of their use in gynaecological procedures have given mixed results regarding reduced rates of ureteric injury [118, 119]. However, ureteric stent use may reduce diagnostic delay and post-operative morbidity [120].

Many clinicians may not appreciate the significant risk of death in women with ureteric injuries. Although most bladder injuries are diagnosed intra-operatively, most ureteric injuries are detected post-operatively, with a typical diagnostic delay of 10–14 days [3, 40, 47, 65]. A study of >200,000 women undergoing hysterectomy found that compared with patients with no ureteric injury, patients with a delayed diagnosis of ureteric injury have significantly lower 1-year overall survival (99.7% vs 91.7%) [3]. The reasons for the reduced survival were not assessed. This 1 in 12 risk of death at 1 year, akin to stage IIIC colorectal cancer [121], is a terrifying prospect for these patients, who are predominantly women aged 30–50 years undergoing hysterectomy for a benign indication [110]. Separate to death is the inconvenience and morbidity of further interventions. Although some ureteric injuries may be managed by minimally invasive means such as ureteric stent insertion, most will require formal repair via ureteric reimplantation (neoureterocystostomy) [40, 46, 47, 122]. Some selected cases will require additional measures such as a psoas hitch, Boari flap, uretero-ureterostomy or bowel interposition [65]. Some require up to six further procedures [91].

The leading risk factor for urological injury was surgeon inexperience or low volume, identified by 18 studies [23, 28, 34, 40, 41, 43, 49, 50, 57, 59, 62, 77, 78, 82, 87, 93, 96, 97]. A strong demonstration of this is Mäkinen et al.’s Finnish study of >10,000 hysterectomies. This found that, compared with surgeons who had performed ≤30 laparoscopic hysterectomies, those with experience of >30 procedures had a significantly lower rate of injury to the bladder (2.2% vs 0.8%) or ureter (2.0% vs 0.5%) [123]. Gynaecological trainees and consultants early in their learning curve may benefit their patients by increasing their supervision during this time, as well as incorporating the most commonly advocated preventative strategies of improving their anatomical knowledge, and intra-operative techniques of strong uterine traction and careful dissection generally.

This review’s strengths are its comprehensive curation and critique of the literature. It is limited by the lack of randomised trials and the heterogeneous methodology of the studies included. Non-randomised studies are more prone to bias; thus, these results should be interpreted with caution. However, as pointed out by some of the identified studies [82], national registry-based observational studies may better reflect clinical reality in the hands of the “average” gynaecological surgeon than randomised controlled trials. Exclusion of non-English publications is another limitation. Additionally, this review’s inclusion criteria sought to balance broad inclusion with manageable data collection. The decision to include the 15 largest studies for each surgical approach, regardless of whether or not they observed any bladder or ureteric complications, may have reduced the number of studies for which sub-group meta-analysis was possible. Furthermore, the small number of eligible works identified for open abdominal hysterectomy for malignant histology (4 studies), vaginal hysterectomy for any histology (6 studies) and robot-assisted hysterectomy for any histology (3 studies) limits confidence in the findings for these sub-groups.

Many studies may have had inadequate follow-up to detect ureteric injuries. Sixty-eight of the 97 studies included did not detail their post-operative follow-up (Table 1). Of those that did, 19 out of 29 studies stated only their planned consultations, without measuring whether these occurred or not [3, 25, 36, 49, 54, 58, 59, 61, 62, 64, 71, 75, 77, 79, 80, 86, 90, 93, 95, 103]. As highlighted by Wang et al., “both short- and long-term follow up are required because complications may occur greater than four weeks after the initial surgery” [62]. Hence, this opaque provision of aftercare limits certainty that all events have been captured, and pooled complication rates may be higher than our findings suggest.

This study’s methodology confined its scope to bladder and ureteric injury. Caesarean section and hysterectomy may cause other urological complications, such as transient urinary retention, nerve injury causing atonic bladder [89], vesico-vaginal fistula or uretero-vaginal fistula [49]. These were not assessed by this review.

Conclusion

Caesarean section and most types of hysterectomy carry low rates of bladder and ureteric injury. Surgeon inexperience represents the leading risk factor for iatrogenic injury. Improved anatomical knowledge is the most commonly suggested preventative strategy. Obstetricians and gynaecologists should counsel the patient for her individual risk of injury, prospectively establish risk factors and implement preventative strategies to minimise risk.

Supplementary information

(PDF 4.42 mb)

Authors’ contributions

G.W. and N.K. created the concept, acquired and analysed the data and wrote the initial manuscript. M.O.C. performed the statistical analyses. All authors refined the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Declarations

Ethical standards including informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Carley ME, McIntire D, Carley JM, et al. Incidence, risk factors and morbidity of unintended bladder or ureter injury during hysterectomy. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2002;13(1):18–21. doi: 10.1007/s001920200004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mariotti G, Natale F, Trucchi A, et al. Ureteral injuries during gynecologic procedures. Minerva Urol Nefrol. 1997;49(2):95–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blackwell RH, Kirshenbaum EJ, Shah AS, et al. Complications of recognized and unrecognized iatrogenic ureteral injury at time of hysterectomy: a population based analysis. J Urol. 2018;199(6):1540–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.12.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Symmonds RE. Ureteral injuries associated with gynecologic surgery: prevention and management. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1976;19(3):623–644. doi: 10.1097/00003081-197609000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dowling R, Corriere J, Jr, Sandler C. Iatrogenic ureteral injury. J Urol. 1986;135(5):912–915. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)45921-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engelsgjerd JS, LaGrange CA. Ureteral injury [internet] Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls; 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding G, Li X, Fang D, et al. Etiology and ureteral reconstruction strategy for iatrogenic ureteral injuries: a retrospective single-center experience. Urol Int. 2021;105(5–6):470–6. doi: 10.1159/000511141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Balduzzi S, Rücker G, Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. Evid Based Ment Health. 2019;22(4):153–160. doi: 10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reeves BC, Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, et al. Including non-randomized studies on intervention effects. In: Higgins JGS, et al., editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: Wiley; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wells GA SB, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in metaanalyses. [Internet] Ottawa, Canada: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2000. Accessed 1 September 2017. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 13.Conde-Agudelo A. Intrafascial abdominal hysterectomy: outcomes and complications of 867 operations. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2000;68(3):233–239. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(99)00197-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cosson M, Lambaudie E, Boukerrou M, et al. Vaginal, laparoscopic, or abdominal hysterectomies for benign disorders: immediate and early postoperative complications. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;98(2):231–236. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(01)00341-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leanza F, Bianca G, Cinquerrui G, et al. Lesions of the urinary organs during abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy. Urogynaecol Int J. 2001;15(2):25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liapis A, Bakas P, Giannopoulos V, et al. Ureteral injuries during gynecological surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2001;12(6):391–393. doi: 10.1007/PL00004045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mathevet P, Valencia P, Cousin C, et al. Operative injuries during vaginal hysterectomy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;97(1):71–75. doi: 10.1016/S0301-2115(00)00484-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milad MP, Morrison K, Sokol A, et al. A comparison of laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy vs laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy. Surg Endosc. 2001;15(3):286–288. doi: 10.1007/s004640000328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Seman EI, O'Shea RT, Gordon S, et al. Routine cystoscopy after laparoscopically assisted hysterectomy: what's the point? Gynaecol Endosc. 2001;10(4):253–256. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2508.2001.00459.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wattiez A, Soriano D, Cohen SB, et al. The learning curve of total laparoscopic hysterectomy: comparative analysis of 1647 cases. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9(3):339–345. doi: 10.1016/S1074-3804(05)60414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boukerrou M, Lambaudie E, Collinet P, et al. A history of cesareans is a risk factor in vaginal hysterectomies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003;82(12):1135–1139. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0412.2003.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khashoggi TY. Higher order multiple repeat cesarean sections: maternal and fetal outcome. Ann Saudi Med. 2003;23(5):278–282. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2003.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shen CC, Wu MP, Kung FT, et al. Major complications associated with laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy: ten-year experience. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10(2):147–153. doi: 10.1016/S1074-3804(05)60289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dorairajan G, Rani PR, Habeebullah S, et al. Urological injuries during hysterectomies: a 6-year review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2004;30(6):430–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2004.00226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koh LW, Koh PH, Lin LC, et al. A simple procedure for the prevention of ureteral injury in laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2004;11(2):167–169. doi: 10.1016/S1074-3804(05)60192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parkar RB, Thagana NG, Otieno D. Laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy for benign uterine pathology: is it time to change? East Afr Med J. 2004;81(5):261–266. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v81i5.9171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rashid M, Rashid RS. Higher order repeat caesarean sections: how safe are five or more? BJOG. 2004;111(10):1090–1094. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Steed H, Rosen B, Murphy J, et al. A comparison of laparoscopic-assisted radical vaginal hysterectomy and radical abdominal hysterectomy in the treatment of cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93(3):588–593. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chang WC, Torng PL, Huang SC, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy with uterine artery ligation through retrograde umbilical ligament tracking. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(4):336–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phipps MG, Watabe B, Clemons JL, et al. Risk factors for bladder injury during cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(1):156–160. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000149150.93552.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tae Kim Y, Sung Yoon B, Hoon Kim S, et al. The influence of time intervals between loop electrosurgical excision and subsequent hysterectomy on the morbidity of patients with cervical neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;96(2):500–503. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vakili B, Chesson RR, Kyle BL, et al. The incidence of urinary tract injury during hysterectomy: a prospective analysis based on universal cystoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192(5):1599–1604. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akyol D, Esinler I, Guven S, et al. Vaginal hysterectomy: results and complications of 886 patients. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;26(8):777–781. doi: 10.1080/01443610600984529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bojahr B, Raatz D, Schonleber G, et al. Perioperative complication rate in 1706 patients after a standardized laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy technique. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13(3):183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dauleh W, Al Sakka M, Shahata M. Urinary tract injuries during caesarean section. Qatar Med J. 2006;15(2):8–10. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Bergamini V, et al. Laparoscopic management of endometrial cancer in nonobese and obese women: a consecutive series. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13(4):269–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kafy S, Huang JY, Al-Sunaidi M, et al. Audit of morbidity and mortality rates of 1792 hysterectomies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13(1):55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahdavi A, Peiretti M, Dennis S, et al. Comparison of laparoscopic hysterectomy morbidity for gynecologic, oncologic, and benign gynecologic conditions. JSLS. 2006;10(4):439–442. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Roman JD. Patient selection and surgical technique may reduce major complications of laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2006;13(4):306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharon A, Auslander R, Brandes-Klein O, et al. Cystoscopy after total or subtotal laparoscopic hysterectomy: the value of a routine procedure. Gynecol Surg. 2006;3(2):122–127. doi: 10.1007/s10397-005-0164-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnston K, Rosen D, Cario G, et al. Major complications arising from 1265 operative laparoscopic cases: a prospective review from a single center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14(3):339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Karaman Y, Bingol B, Gunenc Z. Prevention of complications in laparoscopic hysterectomy: experience with 1120 cases performed by a single surgeon. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14(1):78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Leonard F, Fotso A, Borghese B, et al. Ureteral complications from laparoscopic hysterectomy indicated for benign uterine pathologies: a 13-year experience in a continuous series of 1300 patients. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(7):2006–2011. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nawaz FH, Khan ZE, Rizvi J. Urinary tract injuries during obstetrics and gynaecological surgical procedures at the Aga Khan University Hospital Karachi, Pakistan: a 20-year review. Urol Int. 2007;78(2):106–111. doi: 10.1159/000098065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ng CC, Chern BS. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy: a 5-year experience. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2007;276(6):613–618. doi: 10.1007/s00404-007-0385-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Hanlan KA, Dibble SL, Garnier AC, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy: technique and complications of 830 cases. JSLS. 2007;11(1):45–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Soong YK, Yu HT, Wang CJ, et al. Urinary tract injury in laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14(5):600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tian YF, Lin YS, Lu CL, et al. Major complications of operative gynecologic laparoscopy in southern Taiwan: a follow-up study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2007;14(3):284–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xu H, Chen Y, Li Y, et al. Complications of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy for invasive cervical cancer: experience based on 317 procedures. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(6):960–964. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-9129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen Y, Xu H, Li Y, et al. The outcome of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy for cervical cancer: a prospective analysis of 295 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(10):2847–2855. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kyung MS, Choi JS, Lee JH, et al. Laparoscopic management of complications in gynecologic laparoscopic surgery: a 5-year experience in a single center. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(6):689–694. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ark C, Gungorduk K, Celebi I, et al. Experience with laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy for the enlarged uterus. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;280(3):425–430. doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-0944-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chopin N, Malaret JM, Lafay-Pillet MC, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign uterine pathologies: obesity does not increase the risk of complications. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(12):3057–3062. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dep348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Donnez O, Jadoul P, Squifflet J, et al. A series of 3190 laparoscopic hysterectomies for benign disease from 1990 to 2006: evaluation of complications compared with vaginal and abdominal procedures. BJOG. 2009;116(4):492–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ibeanu OA, Chesson RR, Echols KT, et al. Urinary tract injury during hysterectomy based on universal cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):6–10. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818f6219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Juillard C, Lashoher A, Sewell CA, et al. A national analysis of the relationship between hospital volume, academic center status, and surgical outcomes for abdominal hysterectomy done for leiomyoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(4):599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lafay Pillet MC, Leonard F, Chopin N, et al. Incidence and risk factors of bladder injuries during laparoscopic hysterectomy indicated for benign uterine pathologies: a 14.5 years experience in a continuous series of 1501 procedures. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(4):842–849. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee ET, Wong FW, Lim CE. A modified technique of LAVH with the Biswas uterovaginal elevator. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16(6):755–760. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rahman MS, Gasem T, Al Suleiman SA, et al. Bladder injuries during cesarean section in a University Hospital: a 25-year review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;279(3):349–352. doi: 10.1007/s00404-008-0733-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yan X, Li G, Shang H, et al. Complications of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy—experience of 117 patients. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19(5):963–967. doi: 10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a79430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gungorduk K, Asicioglu O, Celikkol O, et al. Iatrogenic bladder injuries during caesarean delivery: a case control study. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;30(7):667–670. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2010.486086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wang L, Merkur H, Hardas G, et al. Laparoscopic hysterectomy in the presence of previous caesarean section: a review of one hundred forty-one cases in the Sydney West Advanced Pelvic Surgery Unit. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(2):186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wright JD, Devine P, Shah M, et al. Morbidity and mortality of peripartum hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(6):1187–1193. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181df94fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anpalagan A, Hardas G, Merkur H. Inadvertent cystotomy at laparoscopic hysterectomy—Sydney West Advanced Pelvic Surgery (SWAPS) Unit January 2001 to June 2009. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;51(4):325–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2011.01334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brummer THI, Jalkanen J, Fraser J, et al. FINHYST, a prospective study of 5279 hysterectomies: complications and their risk factors. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(7):1741–1751. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Doganay M, Yildiz Y, Tonguc E, et al. Abdominal, vaginal and total laparoscopic hysterectomy: perioperative morbidity. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284(2):385–389. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1678-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jung MH, Lee BY. Transumbilical single-port laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy via 12-mm trocar incision site. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21(7):599–602. doi: 10.1089/lap.2010.0396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kavallaris A, Kalogiannidis I, Chalvatzas N, et al. Laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy with and without laparoscopic transsection of the uterine artery: an analysis of 1,255 cases. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284(2):379–384. doi: 10.1007/s00404-010-1662-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Song T, Kim TJ, Kang H, et al. A review of the technique and complications from 2,012 cases of laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy at a single institution. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;51(3):239–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2011.01296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Al-Shahrani M. Bladder injury during Cesarean section: a case control study for 10 years. Bahrain Med Bull. 2012;34(3):1–6. Available from: https://www.bahrainmedicalbulletin.com/september_2012/Bladder-Injury.pdf. Accessed 30 Nov 2019.

- 71.Cho HY, Kang SW, Kim HB, et al. Prophylactic adnexectomy along with vaginal hysterectomy for benign pathology. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;286(5):1221–1225. doi: 10.1007/s00404-012-2451-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Grosse-Drieling D, Schlutius JC, Altgassen C, et al. Laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy (LASH), a retrospective study of 1,584 cases regarding intra- and perioperative complications. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(5):1391–1396. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-2170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Khan B, Khan B, Sultana R, et al. A ten year review of emergency peripartum hysterectomy in a tertiary care hospital. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2012;24(1):14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kobayashi E, Nagase T, Fujiwara K, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy in 1253 patients using an early ureteral identification technique. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38(9):1194–1200. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2012.01849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee JS, Choe JH, Lee HS, et al. Urologic complications following obstetric and gynecologic surgery. Korean J Urol. 2012;53(11):795–799. doi: 10.4111/kju.2012.53.11.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Mueller A, Boosz A, Koch M, et al. The Hohl instrument for optimizing total laparoscopic hysterectomy: results of more than 500 procedures in a university training center. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(1):123–127. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-1905-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rao D, Yu H, Zhu H, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of iatrogenic ureteral and bladder injury caused by traditional gynaecology and obstetrics operation. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285(3):763–765. doi: 10.1007/s00404-011-2075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sandberg EM, Cohen SL, Hurwitz S, et al. Utility of cystoscopy during hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1363–1370. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318272393b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Teerapong S, Rungaramsin P, Tanprasertkul C, et al. Major complication of gynaecological laparoscopy in Police General Hospital: a 4-year experience. J Med Assoc Thail. 2012;95(11):1378–1383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tuuli MG, Odibo AO, Fogertey P, et al. Utility of the bladder flap at cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(4):815–821. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824c0e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Choi YS, Park JN, Oh YS, et al. Single-port vs. conventional multi-port access laparoscopy-assisted vaginal hysterectomy: comparison of surgical outcomes and complications. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;169(2):366–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mäkinen J, Brummer T, Jalkanen J, et al. Ten years of progress—improved hysterectomy outcomes in Finland 1996–2006: a longitudinal observation study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(10):e003169. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sheth SS. Vaginal hysterectomy in women with a history of 2 or more cesarean deliveries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013;122(1):70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Dutta DK, Dutta I. Abdominal hysterectomy: a new approach for conventional procedure. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8(4):OC15–OC18. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2014/7263.4307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Han L, Cao R, Jiang JY, et al. Preset ureter catheter in laparoscopic radical hysterectomy of cervical cancer. Genet Mol Res. 2014;13(2):3638–3645. doi: 10.4238/2014.May.9.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Nguyen ML, Stevens E, LaFargue CJ, et al. Routine cystoscopy after robotic gynecologic oncology surgery. JSLS. 2014;18(3):e2014.00261. doi: 10.4293/JSLS.2014.00261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Park JY, Nam JH. Laparotomy conversion rate of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer in a consecutive series without case selection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(9):3030–3035. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3707-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zia S, Rafique M. Intra-operative complications increase with successive number of cesarean sections: myth or fact? Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2014;57(3):187–192. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2014.57.3.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Garabedian C, Merlot B, Bresson L, et al. Minimally invasive surgical management of early-stage cervical cancer: an analysis of the risk factors of surgical complications and of oncologic outcomes. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2015;25(4):714–721. doi: 10.1097/IGC.0000000000000390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kaplanoglu M, Bulbul M, Kaplanoglu D, et al. Effect of multiple repeat cesarean sections on maternal morbidity: data from southeast Turkey. Med Sci Monit. 2015;21:1447–1453. doi: 10.12659/MSM.893333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tan-Kim J, Menefee SA, Reinsch CS, et al. Laparoscopic hysterectomy and urinary tract injury: experience in a health maintenance organization. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2015;22(7):1278–1286. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Dolanbay M, Kutuk MS, Ozgun MT, et al. Laparoscopically-assisted vaginal hysterectomy for enlarged uterus: operative outcomes and the learning curve. Ginekol Pol. 2016;87(5):333–337. doi: 10.5603/GP.2016.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kang HW, Lee JW, Kim HY, et al. Total laparoscopic hysterectomy via suture and ligation technique. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2016;59(1):39–44. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2016.59.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tinelli R, Cicinelli E, Tinelli A, et al. Laparoscopic treatment of early-stage endometrial cancer with and without uterine manipulator: our experience and review of literature. Surg Oncol. 2016;25(2):98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Clave H, Clave A. Safety and efficacy of advanced bipolar vessel sealing in vaginal hysterectomy: 1000 cases. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24(2):272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lim S, Lee S, Choi J, et al. Safety of total laparoscopic hysterectomy in patients with prior cesarean section. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(1):196–201. doi: 10.1111/jog.13191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Satitniramai S, Manonai J. Urologic injuries during gynecologic surgery, a 10-year review. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2017;43(3):557–563. doi: 10.1111/jog.13238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Singla A, Mundhra R, Phogat L, et al. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: indications and outcome in a tertiary care setting. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(3):QC01–QQC3. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/19665.9347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Yaman Tunc S, Agacayak E, Sak S, et al. Multiple repeat caesarean deliveries: do they increase maternal and neonatal morbidity? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30(6):739–744. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1183638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Benson CR, Thompson S, Li G, et al. Bladder and ureteral injuries during benign hysterectomy: an observational cohort analysis in New York State. World J Urol. 2018;07:07. doi: 10.1007/s00345-018-2541-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Koroglu N, Cetin BA, Turan G, et al. Characteristics of total laparoscopic hysterectomy among women with or without previous cesarean section: retrospective analysis. Sao Paulo Med J. 2018;136(5):385–389. doi: 10.1590/1516-3180.2018.0197030718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li F, Guo H, Qiu H, et al. Urological complications after radical hysterectomy with postoperative radiotherapy and radiotherapy alone for cervical cancer. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97(13):e0173. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Petersen SS, Doe S, Rubinfeld I, et al. Rate of urologic injury with robotic hysterectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25(5):867–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Inan AH, Budak A, Beyan E, et al. The incidence, causes, and management of lower urinary tract injury during total laparoscopic hysterectomy. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2019;48(1):45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Otkjaer AM, Jorgensen HL, Clausen TD, et al. Maternal short-term complications after planned cesarean delivery without medical indication: a registry-based study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98(7):905–912. doi: 10.1111/aogs.13549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sirota I, Tomita SA, Dabney L, et al. Overcoming barriers to vaginal hysterectomy: an analysis of perioperative outcomes. J Turk Ger Gynecol Assoc. 2019;20(1):8–14. doi: 10.4274/jtgga.galenos.2018.2018.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sondgeroth KE, Wan L, Rampersad RM, et al. Risk of maternal morbidity with increasing number of cesareans. Am J Perinatol. 2019;36(4):346–351. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1673653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Betran A, Ye J, Moller A, et al. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(6):e005671. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Liu F, Pan Y, Liang Y, et al. The epidemiological profile of hysterectomy in rural Chinese women: a population-based study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e015351. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wright J, Herzog T, Tsui J, et al. Nationwide trends in the performance of inpatient hysterectomy in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122(2):233–241. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318299a6cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lycke K, Kahlert J, Damgaard R, et al. Trends in hysterectomy incidence rates during 2000–2015 in Denmark: shifting from abdominal to minimally invasive surgical procedures. Clin Epidemiol. 2021;13(1179–1349 (Print)):1179–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 112.Isobe M, Kataoka Y, Chikazawa K, et al. The number of overall hysterectomies per population with the perimenopausal status is increasing in Japan: a national representative cohort study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2020;46(12):2651–2661. doi: 10.1111/jog.14517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lin C, Long C, Huang K, et al. Surgical trend and volume effect on the choice of hysterectomy benign gynecologic conditions. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther. 2021;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.4103/GMIT.GMIT_68_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Cure N, Robson S. Changes in hysterectomy route and adnexal removal for benign disease in Australia 2001–2015: a national population-based study. Minim Invasive Surg. 2018;2018:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2018/5828071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Papalekas E, Fisher J. Trends in route of hysterectomy after the implementation of a comprehensive robotic training program. Minim Invasive Surg. 2018;2018:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2018/7362489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Edler KM, Tamussino K, Fülöp G, et al. Rates and routes of hysterectomy for benign indications in Austria 2002–2014. Geburtshilfe Frauenheilkd. 2017;77(5):482–486. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-107784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rudnicki M, Shayo B, McHome B. Is abdominal hysterectomy still the surgery of choice in sub-Saharan Africa? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2021;100(4):715–717. doi: 10.1111/aogs.14087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Chou M, Wang C, Lien RC. Prophylactic ureteral catheterization in gynecologic surgery: a 12-year randomized trial in a community hospital. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20(6):689–693. doi: 10.1007/s00192-008-0788-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Feng D, Tang Y, Yang Y, et al. Does prophylactic ureteral catheter placement offer any advantage for laparoscopic gynecological surgery? A urologist' perspective from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl Androl Urol. 2020;9(5):2262–2269. doi: 10.21037/tau-20-674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Dumont SA-O, Chys BA-O, Meuleman CA-OX, et al. Prophylactic ureteral catheterization in the intraoperative diagnosis of iatrogenic ureteral injury. Acta Chir Belg. 2021;121(4):261–268. doi: 10.1080/00015458.2020.1753148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Crooke H, Kobayashi M, Mitchell B, et al. Estimating 1- and 5-year relative survival trends in colorectal cancer (CRC) in the United States: 2004 to 2014. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(4 Supp):587. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.4_suppl.587. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Alanwar A, Al-Sayed HM, Ibrahim AM, et al. Urinary tract injuries during cesarean section in patients with morbid placental adherence: retrospective cohort study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32(9):1461–1467. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1408069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mäkinen J, Johansson J, Tomás C, et al. Morbidity of 10,110 hysterectomies by type of approach. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(7):1473–1478. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.7.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 4.42 mb)