Abstract

Introduction

Internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint is defined as an abnormal position of the articular disc in relation with mandibular condyle and articular eminence presenting as disc displacement with or without reduction.

Methodology

This study was conducted on thirty patients diagnosed with Internal derangement of TMJ consisting of 8 males and 22 females averaging 34.6 years. Two groups Conventional Arthrocentesis (Group A) and Level 1 Arthroscopy (Group B) consisted of 15 cases each divided alternately. Clinical evaluation parameters included VAS for pain, maximal interincisal opening, deviation on mouth opening, range of motion including lateral excursion & protrusion movements recorded at 1 week, 1 month & 6 months postoperatively. Wilke’s Staging according to MRI findings was recorded preoperatively and 6 months postoperatively.

Results

At 6 month follow-up, average reduction in VAS for pain & deviation on mouth opening was 72.43% & 24.73% in Group A and 77.66% & 65.41% in Group B, respectively. Average increase in MIO, right & left excursion & protrusion movements was 29.55%, 31.33%, 20.12% & 32.45% in Group A and 34.94%, 41.37%, 39.29% and 36.51% in Group B, respectively. Improved results were obtained clinically for all Wilke’s stages in both groups with more number of patients improving in Group B.

Conclusion

On comparing results, improvement was observed in various clinical evaluation parameters of both the groups at 6 months follow-up. However, statistically significant & better results were obtained for the Arthroscopy group.

Keywords: Internal derangement, Temporomandibular joint, Arthrocentesis, Arthroscopy, MRI

Introduction

Internal derangement (ID) of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is defined as an abnormal position of the articular disc in relation with mandibular condyle and articular eminence. Disc displacement with reduction refers to a biomechanical disorder of the mandibular condyle and articular disc wherein in the closed mouth position, the articular disc is seen anterior to the condyle, but when the mouth is opened, it assumes its normal position. Disc displacement without reduction occurs when the articular disc does not assume its normal position in relation with the condyle even upon mouth opening. ID in India has been found to be in the range of 9–50% [1, 2].

To manage ID, the causative factors have to be identified & controlled and the functional loads need to be reduced, allowing joint adaptation/remodelling, thereby, causing decrease in pain, increase in range of motion and restoration of function [3]. Treatment may be divided into various nonsurgical & surgical compartments. A TMJ pathology that does not respond to nonsurgical therapy even after 6–8 weeks requires surgical treatment [4].

TMJ Arthrocentesis involves lavage of the upper joint space (UJS) – hydraulic distention, allowing dilution & removal of inflammatory mediators, breaking adhesions, restoring synovial fluid flow, therefore, lubricating the joint and improving the range of motion [5–7]. Level 1 TMJ Arthroscopy allows lysis of adhesions and debridement of pathologic tissues, all under direct visualization of the joint [8].

The purpose of this study was to compare and evaluate the results of Conventional Arthrocentesis with Level 1 Arthroscopy in the treatment of ID of TMJ.

Material and Method

This prospective comparative study was conducted on thirty patients diagnosed with TMJ ID at the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery from October 2018 to February 2021. The sample consisted of 8 males and 22 females averaging 34.6 years (range 19–62 years). Two groups Conventional Arthrocentesis (Group A) and Arthroscopy Guided Arthrocentesis (Group B) consisted of 15 cases each divided alternately. The Institutional Ethics Committee approval was obtained.

Inclusion criteria were patients with disc derangement with or without reduction, diagnosed both clinically and radiographically and having pain with or without clicking in the TMJ region aggravated by mouth opening, protrusion or lateral excursions of the mandible.

Exclusion criteria were chronic subluxation/ dislocation of TMJ, painless clicks, joint tumour/infection/ankylosis, blood dyscrasias and prior open TMJ surgery.

Clinical evaluation parameters included VAS for pain, MIO, deviation on mouth opening, range of motion including lateral excursion & protrusion movements recorded at 1 week, 1 month & 6 months postoperatively. The patient satisfaction score was evaluated using PGIC scale.

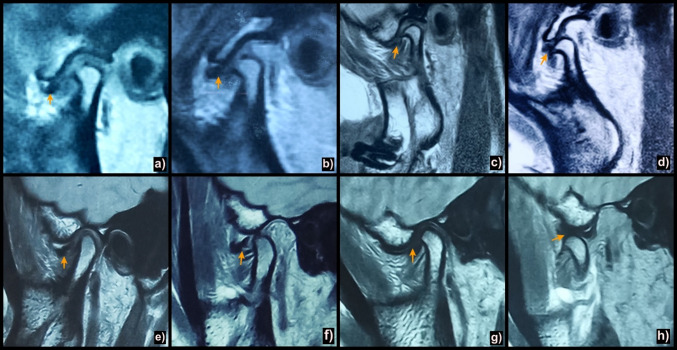

Radiographic parameters included Wilke’s Staging according to MRI findings preoperatively and 6 months postoperatively (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Sagittal oblique T1 weighted MR images depicting articular disc position (arrows) & Wilke's staging a Pre-op closed mouth position showing anteriorly displaced disc; b Pre-op open mouth position showing anterior disc displacement without reduction (Wilke’s Stage IV); c 6 months post-op closed mouth position of the same patient (in a & b) treated with conventional arthrocentesis showing anteriorly displaced disc; d 6 months post-op open mouth position of the same patient (in a & b) treated with conventional arthrocentesis showing increased translation of condyle with anteriorly displaced disc (Wilke’s Stage IV); e) Pre-op closed mouth position showing anteriorly displaced disc; f Pre-op open mouth position showing anterior disc displacement without reduction (Wilke’s Stage III); g 6 months post-op closed mouth position of same patient (in e & f) showing anteriorly displaced disc after treatment with level 1 arthroscopy; h 6 months post-op open mouth position of same patient (in e &f) showing anterior disc displacement with reduction (Wilke’s Stage II) after treatment with level 1 arthroscopy

Procedure

Conventional Arthrocentesis

After administering Auriculotemporal nerve block, a single puncture double needle technique was used to perform arthrocentesis [9]. The needles were directed anteriorly, medially and superiorly into the UJS. The entry point was 10 mm anterior to the tragus and 2 mm beneath the canthotragal line [10]. The joint was lavaged with 300 ml Lactated Ringer's solution [11].

Arthroscope Guided Arthrocentesis

The deepest point of the glenoid fossa and articular eminence were palpated & marked, taking into consideration the anterior & posterior reference points (Fig. 2). The joint was insufflated with 3 ml local anaesthetic. A cannula with a sharp trocar was inserted at 10˚ to the axial plane using rotational and advancing motion through inferolateral approach. A backflow of irrigation fluid indicated entry into the joint which was then backwashed with 30 ml Ringer’s Lactate. The arthroscope (1.9 mm, 30˚) was then inserted and entry into the joint was visually confirmed. An outflow needle was inserted for irrigating the field of vision [12]. Level 1 Arthroscopy was done by walking through the joint examining the medial synovial drape, pterygoid shadow, retrodiscal synovium, posterior slope of articular eminence and glenoid fossa, articular disc, intermediate zone and the anterior recess [13]. During examination, joint was continuously lavaged with approximately 300 mL of Lactated Ringer’s solution. At the termination of the procedure, simple interrupted sutures were taken followed by application of pressure dressing.

Fig. 2.

a Markings over the skin indicating location of the glenoid fossa and articular eminence of the TMJ. Canthotragal line showing Posterior reference point (Point A, entry point into UJS), 10 mm infront of the mid tragus and 2 mm below the canthotragal line and the Anterior reference point (Point B), 10 mm farther along the line & 10 mm below it; b Conventional arthrocentesis technique using single puncture double needle technique; c Arthroscope guided arthocentesis; d Arthroscopic image showing synovitis & fibrillation

Postoperative management included ice application, antibiotics, analgesics, passive mouth opening exercises for the first week from first postoperative day, isometric exercises from the second postoperative week and soft diet for two weeks.

Data were analysed with Microsoft Excel SPSS 13.0 and Chi-square, Paired t test and Pearson correlation tests. Results were considered significant at P < 0.05.

Observations & Results

Of 30 patients of ID, the average age was 34.6 years (range 19—62 years).The age group of 31–40 years comprised of maximum number of patients.

Of 30, 22 patients were female and 8 male. In Group A, there were 12 females and 3 males while in Group B, there were 10 females and 5 males. The difference in the distribution of gender was statistically insignificant (p value – 0.409).

Chronic psychological stress associated with TMJ disorders was reported in 18 (60%) subjects. Of these, 14 were female and 4 male. More females were noted in both the groups.

Average duration of symptoms was 12.1 months (range: 1 month-36 months) and maximum number of patients had a history of duration of 7 – 12 months.

The mean values of various clinical parameters evaluated preoperatively & at follow-up at 1 week, 1 month & 6 months are summarized in Table 1 & Fig. 3.

Table 1.

Mean values of clinical evaluation parameters among Group A & B

| Variables | Group | Mean Pre-op | 1 Week | Mean Difference | 1 Month | Mean Difference | 6 Months | Mean Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | A (n = 15) | 8.2 | 5.73 | 2.47 | 3.66 | 4.54 | 2.26 | 5.94 |

| B (n = 15) | 8.07 | 4.86 | 3.2 | 2.8 | 5.8 | 1.8 | 6.26 | |

| MIO in mm | A (n = 15) | 24.7 | 30.3 | 5.6 | 33.1 | 8.4 | 34 | 7.3 |

| B (n = 15) | 26.9 | 32.2 | 5.3 | 35.6 | 8.7 | 36.3 | 9.4 | |

| Deviation on Mouth Opening in mm | A (n = 15) | 1.86 | 2.8 | 0.94 | 1.66 | 0.2 | 1.4 | 0.46 |

| B (n = 15) | 1.33 | 1.93 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.87 | |

| Right Lateral Excursion in mm | A (n = 15) | 5.33 | 4.86 | 0.47 | 6.73 | 1.4 | 7 | 1.67 |

| B (n = 15) | 5.8 | 5.6 | 0.2 | 7.46 | 1.66 | 8.2 | 2.4 | |

| Left Lateral Excursion in mm | A (n = 15) | 6.66 | 6.13 | 0.53 | 7.86 | 1.2 | 8 | 1.34 |

| B (n = 15) | 5.93 | 5.86 | 0.07 | 7.46 | 1.53 | 8.26 | 2.33 | |

| Maximal Protrusion Movement in mm | A (n = 15) | 4.53 | 4.46 | 0.07 | 6.13 | 1.6 | 6 | 1.47 |

| B (n = 15) | 4.93 | 4.73 | 0.2 | 6.06 | 1.13 | 6.73 | 1.8 |

(n = number of patients; mm = millimetres)

Fig. 3.

Graph illustrating comparison of various clinical evaluation parameters (Gp A—Group A; Gp B—Group B; DOM—deviation on mouth opening; RLE —right lateral excursion; LLE—left lateral excursion; MPM—maximal protrusion movement)

As regards the mean VAS score at 6 months postoperatively, a statistically significant difference was found between the groups (p value 0.022) from preoperative values which decreased by a mean difference of 5.94 (72.43%) in Group A and 6.26 (77.66%) in Group B, with a greater decrease noted in Group B.

As regards the mean MIO at 6 months postoperatively, a statistically significant difference was found between the groups (p value 0.03) from preoperative values which increased by a mean difference of 7.30 mm (29.55%) in Group A and 9.4 mm (34.94%) in Group B, with a greater increase noted in Group B.

As regards the mean deviation on mouth opening at 6 months postoperatively, a statistically significant difference was found between the groups (p value 0.022) from preoperative values which decreased by a mean difference of 0.46 mm (24.73%) in Group A and 0.87 mm (65.41%) in Group B, with a greater decrease noted in Group B.

As regards the mean right lateral excursion at 6 months postoperatively, a statistically significant difference was found between the groups (p value 0.029) from preoperative values which increased by a mean difference of 1.67 mm (31.33%) in Group A and 2.40 mm (41.37%) in Group B, with a greater increase noted in Group B.

As regards the mean left lateral excursion at 6 months postoperatively, a statistically significant difference was found between the groups (p value 0.0337) from preoperative values which increased by a mean difference of 1.34 mm (20.12%) in Group A and 2.33 mm (39.29%) in Group B, with a greater increase noted in Group B.

As regards the mean maximal protrusion movement at 6 months postoperatively, a statistically significant difference was found between the groups (p value 0.017) from preoperative values which increased by a mean difference of 1.47 mm (32.45%) in Group A and 1.80 mm (36.51%) in Group B, with a greater increase noted in Group B.

Comparison of all the above according to Wilke’s staging is given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of clinical evaluation parameters with respect to Wilke’s staging

| Wilke's staging | N | Pre-op | 6 months post-op | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | MIO | Range of Motion | VAS | MIO | Range of Motion | ||||||

| Right | Left | Protrusion | Right | Left | Protrusion | ||||||

| GROUP A | |||||||||||

| II | 7 | 7.85 | 26.85 | 5.42 | 7.85 | 5.42 | 2.14 | 34.71 | 7.57 | 8.85 | 6.71 |

| III | 6 | 8.16 | 23 | 5 | 5.66 | 3.33 | 2.5 | 30 | 6.66 | 7.5 | 4.83 |

| IV | 1 | 9 | 28 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 37 | 6 | 6 | 7 |

| V | 1 | 10 | 17 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 2 | 21 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| GROUP B | |||||||||||

| II | 8 | 8 | 29.62 | 6.25 | 5.37 | 5 | 1.25 | 36.87 | 8.75 | 8.37 | 6.62 |

| III | 5 | 7.8 | 24.2 | 5 | 6.2 | 5.2 | 2 | 35.4 | 7.6 | 8.27 | 7.2 |

| IV | 2 | 9 | 23 | 6 | 7.5 | 4 | 2 | 36.5 | 7.5 | 9 | 6 |

| – | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Wilke's staging | N | Mean Difference | P value | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VAS | MIO | Range of Motion | VAS | MIO | Range of Motion | ||||||

| Right | Left | Protrusion | Right | Left | Protrusion | ||||||

| GROUP A | |||||||||||

| II | 7 | 5.71 | 7.86 | 2.15 | 1 | 1.29 | 0.001 | 0.035 | 0.002 | 0.233 | 0.012 |

| III | 6 | 5.66 | 7 | 1.66 | 1.84 | 1.5 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.153 | 0.11 | 0.045 |

| IV | 1 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 2 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 |

| V | 1 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 | > 0.05 |

| GROUP B | |||||||||||

| II | 8 | 6.75 | 7.25 | 2.5 | 3 | 1.62 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| III | 5 | 5.8 | 11.2 | 1.6 | 2.01 | 2 | 0.005 | 0.019 | 0.0001 | 0.049 | 0.022 |

| IV | 2 | 7 | 13.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 2 | 0.017 | 0.421 | 0.5 | 0.205 | 0.2 |

| – | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

(N = number of patients; MIO & Range of motion measured in millimetres)

The distribution of patients according to Wilke’s staging at 6 months postoperatively is given in Table 3.

Table 3.

Distribution of patients according to Wilke’s staging postoperatively at 6 months

| Wilke's Staging | AC (GROUP A) | AS (GROUP B) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = Pt | N | I | II | III | IV | V | n = Pt | N | I | II | III | IV | V | |

| II | 7 | 1 | 2 | 4 | – | – | – | 8 | 2 | 4 | 2 | – | – | – |

| III | 6 | – | 1 | 2 | 3 | – | – | 5 | – | 2 | 2 | 1 | – | – |

| IV | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | 2 | – | – | – | – | 2 | – |

| V | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

(n = number of patients; N = Normal; AC = Arthrocentesis; AS = Arthroscopy)

In Group A, preoperatively 7 patients were at stage II. At 6 months postoperatively, of those 7, 4 remained at stage II, 2 improved to Stage 1 and 1 patient recovered completely. A total of 6 patients were at stage III preoperatively, out of which, 3 remained at stage III, 2 improved to stage II and 1 improved to stage I. One patient was at stage IV and remained at stage IV only. One was at stage V, and she too remained at stage V.

In Group B, preoperatively 8 patients were at stage II. At 6 months postoperatively, of those 8, 2 remained at stage II, 4 improved to Stage 1 and 2 patients recovered completely. A total of 5 patients were at stage III preoperatively, out of which, 1 remained at stage III, 2 improved to each stage I & II, respectively. 2 patients were at stage IV and remained at stage IV only at 6 months postoperatively. No patient was at stage V preoperatively.

During Arthroscopy Guided Arthrocentesis, the various arthroscopic findings observed were synovitis in 11 patients, fibrous adhesions in 10 patients, fibrillations in 8, hyperemia of posterior attachment in 6 & chondromalacia in 5 patients.

Intraoperative complications like transient facial nerve paralysis was reported in 66.6% of patients in Group A and 0% in Group B. Fluid extravasation was seen in 46.6% in Group A and 26.6% in Group B. Bleeding was reported in 26.6% in Group A and 40.0% in Group B.

The mean patient satisfaction score in Group A was 4.73 and that in Group B was 5.53.

Discussion

There have been ongoing issues regarding the management of TMJ disorders ranging from observation and conservative treatment to aggressive surgery to minimally invasive arthroscopic approach more recently. This study compared the results of arthocentesis & arthroscopy to treat patients of ID of TMJ.

In this study, the average age of patients was 34.6 years. This is in correlation with studies by Goudot et al. [14], (38 yrs) and Murakami et al. [15] (32.7yrs). Average duration of symptoms was 12.1 months and the reason for patients presenting with long duration of symptoms can be attributed to misdiagnosis or inadequate treatment over a course of time.

More number of female patients (73.3%) reported with this condition than male patients as reported by Goudot et al. [15] (75%). Psychological stress may be the cause of difference in distribution of gender, similar results were found by Ahuja et al. [16].

For arthrocentesis, a single puncture double needle technique was used instead of two puncture double needle, as it prevents one extra puncture to the joint and also increases the success rate as suggested by Alkan A & Bas B (9). Stock made cannula of two needles is costly; the cost was overcome by indigenously soldering two 18 gauge needles together at 45° angle as described by Khaleeq-Ur Rehman et al. [17] & Rahal et al. [18].

The average preoperative VAS score for pain was 8.2 in Group A and 8.07 in Group B, which was statistically insignificant (p value-0.7760). So, both the groups were comparable preoperatively. A statistically significant difference was found from the preoperative values to 1 week, 1 month and 6 months postoperatively between groups A and B.

The mean reduction in pain was more in Group B at all the three follow-ups, signifying that Arthroscopy has superior efficacy in decreasing pain, as in accordance with Al-Moraissi [19]. The substantial reduction in pain can be attributed to the large diameter of the port enabling lavage under high pressure causing aggressive & extensive removal of inflammatory cytokines.

The average preoperative MIO in between Group A and Group B was statistically insignificant (p value-0.4130). So, both groups were comparable preoperatively.

There was better improvement in MIO at 1 week in Group A, while at 1 month and 6 months it was better in Group B. Thus, the long term improvement in MIO was better in patients treated with arthroscopy. Goudot et al. [14] observed that the average increase in MIO in arthrocentesis group was 4.3 ± 4.4 mm and that in arthroscopy group was 9.6 ± 5.8 mm. The results of meta-analysis by Al-Moraissi [19] revealed that Arthroscopy had greater efficiency than Arthrocentesis in increasing range of motion and reducing pain.

In this study, in both groups, patients with a shorter duration of symptoms had better outcome of MIO. In Group B, these patients reported greater reduction in pain. Emshoff and Rudich [20] & Israel HA et al. [21] suggested that arthrocentesis provided less pain reduction in patients with chronic rather than acute TMJ pain.

The average preoperative deviation on mouth opening in Group A and in Group B was statistically insignificant (p value-0.3230, paired t test). So, both the groups were comparable preoperatively.

At 1 week postoperatively, there was statistically significant increase in mean deviation on mouth opening in both groups. At 1 month and 6 months, statistically significant decrease in deviation on mouth opening was found in both groups. At 6-month follow-up, substantial decrease by 65.41% was observed in Group B compared to 24.73% in Group A. However, Fridrich et al. [22] did not found statistically significant difference in outcome between the two groups.

The lateral excursion movements and maximal protrusion movements in both the groups at 1 week were found to be less than the preoperative values but significant improvement was observed at 1 month & 6-month follow-up in Group B. Similar results were attained by Al-Moraissi [19]. The reason behind the marginal decrease of the 1 week postoperative values may be attributed to the postoperative pain, probably more significant after arthroscopy because of larger diameter portal compared to conventional arthrocentesis.

Classified according to the Wilke’s staging [23], 15 patients belonged to stage II, 7 in group A and 8 in group B. A statistically significant difference was found at 6 months with respect to VAS, MIO and lateral excursion movements in all stages in both groups.

Eleven patients belonged to stage III, 6 in group A and 5 in group B. A statistically significant difference was found at 6 months with respect to VAS and MIO.

Three patients belonged to stage IV. Of those 3, 1 in group A and 2 in group B. There was a single patient of stage V, in group A. There was no statistically significant difference at 6 months with respect to VAS, MIO and lateral excursion movements.

Intergroup comparison between Group A & Group B for all Wilke’s stages with respect to VAS, MIO and lateral excursions was statistically insignificant at 6 months as the number of patients in each stage for each group were very low. However, though improved results were obtained clinically for all Wilke’s stages in both groups, more number of patients improved in group B.

The patients with Wilke’s Stage IV & V improved clinically, they remained at the same Wilke’s stages at 6 months as hard tissue changes take time for remodelling. Ahmed et al. [24] too concluded that there was improvement in mouth opening & pain scores irrespective of the Wilke’s score.

Due to chronic overloading of the joint, muscle tenderness was present in 10 out of 30 study patients. They were advised physiotherapy consisting of ‘stretching’ exercises, massage, ultrasound, TENS, muscle relaxants and referral to physiotherapist. Similar protocol was followed by Goudot et al. [14].

Intraoperative complications like Transient Facial Nerve paralysis were reported in 66.6% of patients in Group A and 0% in Group B which resolved with the effect of anaesthesia in about 60–90 min. Fluid extravasation was seen in 46.6% in Group A and 26.6% in Group B which was managed by application of pressure dressing. Bleeding was reported in 26.6% in Group A and 40.0% in Group B which was controlled by pressure packing. The rate of complications reported was slightly higher than studies by Goudot et al. [14] and Fridrich et al. [22].

Conclusion

While comparing results of arthrocentesis with arthroscopy, improvement was observed in various clinical evaluation parameters such as VAS for pain, MIO, deviation on mouth opening and range of motion including lateral excursion & protrusion movements of both the groups at 6-month follow-up. However, statistically significant & better results were obtained for the Arthroscopy group.

According to Wilke’s staging, even though the results were statistically insignificant, a higher number of patients showed improvement with Arthroscopy. The reason may be that Arthroscopy releases negative pressure on the disc causing lysis of adhesions, increasing the narrowed joint space, decreasing surface friction & reducing thickness of the synovial fluid. The arthroscope passing directly through the adhesions also may lead to better outcomes. Direct visual examination of the joint by Arthroscopy also aids in diagnosis, therefore, providing information regarding the need for further surgery in case of residual symptoms. Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size and short follow-up period (6 months).

Acknowledgements

None

Abbreviations

- ID

Internal derangement

- TMJ

Temporomandibular joint

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MIO

Maximal interincisal opening

- VAS

Visual analog scale

- UJS

Upper joint space

Author’s Contribution

Dr. Dewanshi Rajpoot did all preoperative preparations, history taking, postoperative care, proper follow-up, maintained the records & prepared the first draft of the manuscript alongwith subsequent editing & formatting, Dr. Sonal Anchlia performed arthroscopic surgeries, drafted the study conception & design & reviewed the entire paper critically for important intellectual content, revision & editions, Dr. Utsav Bhatt performed the arthrocentesis procedures and contributed to the analysis & writing of this paper. Dr. Jigar Dhuvad reviewed the paper & suggested editions accordingly. Dr. Hiral Patel & Zaki Mansuri positively contributed to write the paper.

Funding

This study was not supported by any funding.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors have any conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Muthukrishnan A, Sekar GS. Prevalence of temporomandibular disorders in Chennai population. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2015;27:508–515. doi: 10.4103/0972-1363.188686. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karthik R, Hafila MI, Saravanan C, Vivek N, Priyadarsini P, Ashwath B. Assessing prevalence of temporomandibular disorders among university students: a questionnaire study. J Int Soc Prevent Communit Dent. 2017;7(Suppl 1):S24–S29. doi: 10.4103/jispcd.JISPCD_146_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Israel HA. Internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint: new perspectives on an old problem. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin N Am. 2016;28(3):313–333. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moses JJ. Temporomandibular joint arthrocentesis and arthroscopy: rationale and technique. Peterson’s Princ Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;963–88.

- 5.Nitzan DW, Dolwick MF, Martinez GA. Temporomandibular joint arthrocentesis: a simplified treatment for severe, limited mouth opening. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Off J Am Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1991 Nov;49(11):1163–7; discussion 1168–1170. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Dimitroulis G, Dolwick MF, Martinez A. (1995) Temporomandibular joint arthrocentesis and lavage for the treatment of closed lock: a follow-up study. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 33(1):23–6; discussion 26–27. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Hosaka H, Murakami K, Goto K, Iizuka T. Outcome of arthrocentesis for temporomandibular joint with closed lock at 3 years follow-up. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;82(5):501–504. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(96)80193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimitroulis G. Temporomandibular joint surgery: what Does it mean to India in the 21st Century? J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2012;11(3):249–257. doi: 10.1007/s12663-012-0419-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alkan A, Baş B. The use of double-needle canula method for temporomandibular joint arthrocentesis: clinical report. Eur J Dent. 2007;1(3):179–182. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1698335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nitzan DW. (2006) Arthrocentesis--incentives for using this minimally invasive approach for temporomandibular disorders. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin N Am. 18(3):311–28, vi. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Kaneyama K, Segami N, Nishimura M, Sato J, Fujimura K, Yoshimura H. The ideal lavage volume for removing bradykinin, interleukin-6, and protein from the temporomandibular joint by arthrocentesis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Off J Am Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(6):657–661. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCain JP, de la Rua H, LeBlanc WG. Puncture technique and portals of entry for diagnostic and operative arthroscopy of the temporomandibular joint. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg. 1991;7(2):221–232. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(91)90111-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCain JP. Principles and practice of temporomandibular joint arthroscopy. Mosby-Year Book; 1996.

- 14.Goudot P, Jaquinet AR, Hugonnet S, Haefliger W, Richter M. Improvement of pain and function after arthroscopy and arthrocentesis of the temporomandibular joint: a comparative study. J Cranio-Maxillofac Surg. 2000;28(1):39–43. doi: 10.1054/jcms.1999.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murakami K, Hosaka H, Moriya Y, Segami N, Iizuka T. Short-term treatment outcome study for the management of temporomandibular joint closed lock: a comparison of arthrocentesis to nonsurgical therapy and arthroscopic lysis and lavage. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1995;80(3):253–257. doi: 10.1016/S1079-2104(05)80379-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahuja V, Ranjan V, Passi D, Jaiswal R. Study of stress-induced temporomandibular disorders among dental students: An institutional study. Natl J Maxillofac Surg. 2018;9(2):147–154. doi: 10.4103/njms.NJMS_20_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rehman K-U, Hall T. Single needle arthrocentesis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;47(5):403–404. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh S, Shivamurthy DM, Varghese D. Re: Rahal A, et al (2011) Single-puncture arthrocentesis--introducing a new technique and a novel device. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Off J Am Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 69(1):311; author reply 312. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Al-Moraissi EA. Arthroscopy versus arthrocentesis in the management of internal derangement of the temporomandibular joint: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44(1):104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emshoff R, Rudisch A. Determining predictor variables for treatment outcomes of arthrocentesis and hydraulic distention of the temporomandibular joint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004;62(7):816–823. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2003.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Israel HA, Behrman DA, Friedman JM, Silberstein J. Rationale for early versus late intervention with arthroscopy for treatment of inflammatory/degenerative temporomandibular joint disorders. J Oral Maxillofac Surg Off J Am Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010;68(11):2661–2667. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fridrich KL, Wise JM, Zeitler DL. Prospective comparison of arthroscopy and arthrocentesis for temporomandibular joint disorders. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54(7):816–820. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(96)90526-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkes CH (1989) Internal derangements of the temporomandibular joint. Pathological variations. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 115(4):469–77. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Ahmed N, Sidebottom A, O’Connor M, Kerr H-L. Prospective outcome assessment of the therapeutic benefits of arthroscopy and arthrocentesis of the temporomandibular joint. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;50(8):745–748. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]