Abstract

Service failures of online travel agencies (OTAs) occur frequently, which makes the OTA business operation model face huge risks. However, the current academic circles still pay insufficient attention to OTA service recovery. This study obtained research data through scenario experiment method, and analyzed data through SPSS25.0, HLM6.08 and other statistical software to explore the impact mechanism of consumers’ repurchase intention in OTA service recovery. The empirical results of this study are as follows: Consumers’ negative emotions weaken their relationship with tourism suppliers and OTAs. If the relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers is improved, the relationship quality between consumers and OTAs will also be improved. The relationship quality between consumers and OTAs has a positive impact on consumers’ repurchase intention, and consumer forgiveness has a positive moderating effect between them. This study provides a consumer psychology perspective for discussing OTA’s service recovery, which is conducive to promoting the healthy development of OTA’s business operation model and benefiting consumers.

Keywords: OTA, Service recovery, Negative emotion, Relationship quality, Consumers’ repurchase intention

1. Introduction

The service industry in the Internet era is changing quietly, information technology is the key factor supporting the success of emerging services, and supports service enterprises to innovate service management models [1]. Online travel agencies (OTAs) are the product of the integration of the Internet and tourism. They are changing and subverting the traditional tourism business model and have become a new medium and carrier for tourism destination marketing [2]. To date, many hotels have signed cooperation agreements to join OTAs, such as Priceline, TripAdvisor, and Ctrip. OTAs have obvious advantages in tourism management. Consumers can easily compare the product types, prices, geographical locations, and consumer reviews of various hotels through the OTA platform, which meets the diversified and personalized needs and preferences of consumers. Therefore, OTAs have won extensive relationships with consumers.

Service recovery refers to actions taken by service enterprises to eliminate negative impacts and maintain customer satisfaction after service failure [3,4]. Tourism products are a type of service products, which have the general attributes of service products. Consumers can truly perceive the service quality in the interaction process [5]. Tourism products are a type of service product and have the general attributes of service products. Due to the interaction of service products, it is inevitable that OTA and hotels will fail in the service process, so service recovery must be carried out [6]. On news media and social platforms, we can often see reports about OTAs and hotel service failures. Take China as an example. Since the outbreak of COVID-19, many consumers have stopped traveling abroad due to national prevention and control regulations but will choose to travel at home. Consumers will book tourism services through OTA platforms. Therefore, in many cities in China, OTAs have become one of the key objects of consumer complaints.

This is a case of service failure in China, which is regrettable. The protagonist of the story is Mr. Zhao, a professional manager in Chengdu, China. On December 20, 2021, Mr. Zhao booked M Hotel in OTA, and paid the full cost (US $117) as required. According to the scheduled date, on December 22, 2021, Mr. Zhao checked into M Hotel. He found that the air conditioner in the room he checked in was bad, which affected his mood, so he asked for a room change or a refund. However, Meituan and M Hotel refused to change rooms on the grounds of no room, and did not refund the full amount, only $56.4. Mr. Zhao was very disappointed and dissatisfied with the refund scheme of Meituan and M Hotel, complained about them through the official complaint platform of China, and exposed them through microblog. Mr. Zhao’s complaint had a huge negative effect. The number of Meituan bookings decreased significantly, and the economic losses of M Hotel were also very serious. The turnover in January 2022 decreased by 60%.

From the abovementioned cases, it can be seen that the operation of OTAs has become a service complex with hotels. Hotels are also called tourism suppliers. Tourism supplier is a more formal term. In this study, tourism supplier refers to hotel. In this research scenario, there is a ternary interactive structure of consumers-OTA-hotel. Consumers book tourism services through OTA, while hotel provide direct services. Service failure is very destructive to OTA and hotel. Service failure will cause consumers to have negative emotions toward merchants, reduce their willingness to repurchase from them, and damage their reputation. Merchants need to carry out effective service recovery [7]. Many literatures use the word “merchant”, but the specific meaning is not necessarily the same. In this study, “merchants” include OTA and hotel. Because in OTA services, although hotels provide direct services, consumers conduct transactions with OTA and hotel at the same time, forming a ternary interactive structure of consumers-OTA-hotel. Therefore, OTA and hotel are both consumers’ businesses. The existing literature analyzes the impact of some factors on service recovery, such as consumer participation, perceived risk, consumer sentiment, consumer and merchant joint recovery, consumer emotional balance, and consumer emotional infection [4,8]. In traditional research on service recovery in the tourism industry, consumers’ negative emotions will reduce their trust and satisfaction with businesses [14]. However, the current research still pays little attention to OTA and hotel service recovery, and lacks scientific analysis of the impact mechanism and strategy of service recovery in this field.

Based on the reality and characteristics of frequent service failures of OTAs and hotels, and based on the research foundation and shortcomings of the current academic community, this study deeply explores the impact of consumer negative emotions, relationship quality, consumer forgiveness, and consumer repurchase intention in service recovery through empirical research and applies consumer psychology theory to OTA service recovery, expanding the new field and its theoretical applications.

2. Theoretical analysis and hypothesis

2.1. Negative emotions

Consumer emotion is a subjective experience of whether objective things meet their needs, and it is the experience and feeling of consumers under external stimulation [9]. Main sources of consumer emotions: Evaluation of business products and services; emotions generated by comparing with other products and services; emotions due to attribution [10]. Positive emotions include states such as concentration, confidence, optimism, appreciation, and devotion. The negative emotions include helplessness, loss, fear, communication, and anger [11]. Negative emotions affect consumers’ conversion intention and negative reputation [12]. In the failure of OTA services, as consumers’ perceived risk increases, it will enhance their negative emotions [13]. Whether in the general service scenario or the service failure scenario, consumers’ negative emotions will reduce their trust and satisfaction with merchants, that is, reduce the relationship quality between consumers and merchants [14]. It can be seen that, the current academic research on emotion types and negative emotions has gradually extended from the field of psychology to the field of management. However, there is still a lack of attempts to introduce negative emotions into the research on OTA ecosystem service failure.

2.2. Relationship quality

Relationship quality refers to the strength of continuous connection between customers and enterprises, which is a second-order construct composed of trust, commitment and relationship satisfaction [15]. According to the differences in input, status, and content of bilateral relations, the quality of bilateral relations can be divided into two types: Economic and social [16]. Research has also discussed the impact of peer-to-peer communication, directness, resource dependence, network attachment, perceived service quality, and other factors on relationship quality. These studies have mainly been carried out through empirical research [17,18,19,20]. Compared with consumers who encounter each other, consumers with a trusting relationship have better relationship quality with online stores, and it is confirmed that relationship quality can promote their repurchase intention [21]. In online shopping service failure, consumers’ perceived risk will enhance their negative emotions [13]. Whether in the general service scenario or the service failure scenario, consumers’ negative emotions will reduce their trust and satisfaction with merchants, that is, reduce the relationship quality between consumers and merchants [14,22]. It is envisaged that in the real OTA ecosystem, when tourism suppliers fail to provide services, consumers will feel disappointed, angry, and regretful, reducing the relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers. At the same time, as consumers make travel service reservations through OTAs, after service failure, consumers’ negative emotions will also damage the relationship quality between consumers and OTAs. On the basis of the above theoretical analysis, we propose research hypotheses H1 and H2.

H1

Negative consumer emotions will reduce the relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers.

H2

Negative consumer emotions will reduce the relationship quality between consumers and OTAs.

In the service recovery research of China’s platform economy, the findings show that the quality of the relationship between consumers and service providers can promote the improvement of the quality of the relationship between consumers and platforms [13]. The OTA ecosystem and the broad platform ecosystem have a similar three-way interaction model, and the business operation model is also very comparable. Imagine that consumers have booked a hotel (tourism supplier) through an OTA, the service fails due to the hotel, and the relationship between angry consumers and hotels becomes very poor. In turn, consumers will think that the OTA has poor management and will inevitably blame the OTA. Therefore, we propose research hypothesis H3.

H3

The relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers will improve the relationship quality between consumers and OTAs.

2.3. Consumers’ purchase intention and consumers’ forgiveness

Consumers’ purchase intention is one of the hot spots in the field of consumer psychology. Consumers’ purchase intention includes consumers’ initial purchase intention and consumers’ repurchase intention [23]. Generally speaking, consumers’ repurchase intention is the intention of consumers to buy from a business again after a comprehensive evaluation of the business after the initial purchase [24]. Customer satisfaction is an important driving force for adjusting expectations and customers’ repurchase intention [25]. The factors that affect consumers’ repurchase intention in retail stores, and confirmed that consumer experience, in store emotion, perceived value, satisfaction and loyalty have a direct impact on consumers’ repurchase intention [26]. Xu et al. (2017) based on online consumer text comments, discussed customers' satisfaction and dissatisfaction with hotel products and service attributes, and through regression analysis, discussed the impact of travel purposes, hotel types, hotel stars, etc. On hotel products and service attributes [27]. Big data analysis provided tools and opportunities to explain hotel management and provide decision-making, and discussed how to use user generated content (UGC) to bridge the gap between customer satisfaction and online reviews [28]. Service failure has a negative impact on customer satisfaction, which is an important factor in improving customers’ repurchase intention [29]. For traditional travel agency services, the relationship quality between consumers and merchants will improve consumers’ repurchase intention [30]. Zhao & Wang (2012) conducted in-depth research on online shopping service recovery in China, they confirmed that if the relationship between merchants and consumers is improved, it will promote consumers’ repurchase intention [21]. In real service recovery, if the relationship between consumers and OTAs is relatively harmonious, consumers will be more willing to repurchase. We propose the following three research hypotheses, including two mediating effect hypotheses.

H4

The quality of the relationship between consumers and OTAs will improve consumers’ repurchase intention.

H5

The relationship quality between consumers and OTAs has a mediating effect on the relationship between consumers’ negative emotions and consumers’ repurchase intention.

H6

In the relationship between consumers’ negative emotions and consumers’ repurchase intention, the relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers, the relationship quality between consumers and OTAs play a chain mediating effect.

Consumer forgiveness refers to the tendency of consumers to give up negative behaviors such as retaliation and boycott after being offended or injured by crisis events, but to forgive enterprises or brands [31,32]. In consumer activities, relationship quality and situational factors will affect consumer forgiveness [33]. The form of apology (emoticons vs. no emoticons) will affect consumers’ willingness to forgive, while empathy plays a mediating role, and the severity of errors plays a moderating role in the impact of the form of apology on empathy and consumers’ willingness to forgive [34]. The attribution and severity of service failure significantly negatively affect consumer forgiveness, while brand trust, brand intimacy, and empathy significantly positively affect consumer forgiveness [35]. On this basis, if consumers’ willingness to forgive is strong, it will further improve consumers’ repurchase intention.

Therefore, we propose research hypothesis H7 that consumer forgiveness plays a moderating effect.

H7

Consumers’ forgiveness has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between the relationship quality of consumers and OTAs and consumers’ repurchase intention.

With the above theoretical analysis and seven research hypotheses, we have fully discussed and analyzed and established the research model. See Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Research model.

3. Research methods and data collection

3.1. Design of scenario experiment

In the design of the scenario experiment, this study refers to the practice of the scenario experiment of Zhang et al. (2019), Wei and Lin (2022) [6,36]. In order to improve the scientificity and pertinence of the scenario experiment, our experimental materials are from the OTA service failure cases reported by the Chinese media, and are adapted appropriately according to the variable settings and research needs of this study. Service failure cases are as follows:

“Mr. Hao, from Hangzhou, China, booked a hotel on an OTA platform. After checking in, he found that the door lock of the room was broken, and there were cockroaches and ants in the washroom. Based on this situation, Mr. Hao insisted on a refund from OTA and the hotel but was refused. During the negotiation with the hotel, the hotel service staff also mocked Mr. Hao, causing his dissatisfaction. Later, Mr. Hao complained to China’s tourism administration.”

It should be noted that in the context of China’s cultural environment and service, if consumers are not satisfied with OTAs (such as Ctrip, Meituan, etc.) and hotel service personnel, they can express their disappointment and anger by phone. OTA have complaint phones, and hotels also have complaint phones. This feedback mechanism is relatively perfect. The researcher once booked a hotel in Ctrip. During the check-in process, I found that the hotel room area was not as large as that introduced online, but I didn't mention it at that time. After the service, I informed OTA of my dissatisfaction by phone. Their customer manager apologized to me and modified the online information.

Four research scenarios were designed in this study.

Scenario 1 (high consumer negative emotions × high consumer forgiveness): After Mr. Hao complained, the merchants (OTA and hotel) made service recovery. As Mr. Hao suffered from service failure, he had a strong negative emotion toward the business. Mr. Hao expressed his disappointment and anger to the service personnel of the OTA and the hotel by phone and expressed his dissatisfaction on TikTok and WeChat. However, because the business had made service recovery such as compensation, a refund, and an apology, to a certain extent, it made up for Mr. Hao’s economic loss and emotional loss. He thus showed a tendency of understanding and tolerance toward the businesses.

Scenario 2 (high consumer negative emotions × low consumer forgiveness): After Mr. Hao complained, the merchants (OTA and hotel) made service recovery. As Mr. Hao suffered from service failure, he had strong negative emotions toward the business. Mr. Hao expressed his disappointment and anger to the service personnel of the OTA and the hotel by phone and expressed his dissatisfaction on TikTok and WeChat. Although the merchants took service recovery measures, such as apologies, compensation, and refunds, Mr. Hao believed that his expectations had not been met, that the management of the merchants was poor, and that these service failures would occur again in the future, so he was not understanding and tolerant toward the merchants.

Scenario 3 (low consumer negative emotions × high consumer forgiveness): After Mr. Hao complained, the merchants (OTA and hotel) made service recovery. Although Mr. Hao suffered from service failure, he was a person with relatively high emotional intelligence, good at controlling his own emotions, and had relatively low negative emotions toward the businesses. Because the businesses had taken service recovery measures, such as compensation, a refund, and an apology, this made up for Mr. Hao’s economic loss and emotional loss to a certain extent, and he was a considerate person, so he showed a tendency of understanding and tolerance toward the businesses.

Scenario 4 (low consumer negative emotions × low consumer forgiveness): After Mr. Hao complained, the merchants (OTA and hotel) made service recovery. Although Mr. Hao suffered from service failure, he was a person with high emotional intelligence, good at controlling his own emotions, and had low negative emotions toward the businesses. Although the businesses took service recovery measures, such as apologies, compensation, and refunds, Mr. Hao believed that his expectations had not been met and that the service failure was a management problem of the businesses, so he was not understanding and tolerant toward the businesses.

3.2. Variable measurement

In the scenario experiment, we needed the subjects to fill out a questionnaire after reading the corresponding scenario experimental materials. Therefore, it was necessary to develop a questionnaire for the scenario experiments in this study. The measurement items of the five variables referred to the research results of the current mature scales, as shown in Table 1. We invited 18 citizens from Guilin, China, 21 OTA and hotel practitioners, and four professors and associate professors of consumer psychology to revise the variables, measurement item settings, and language expressions of the first draft of the questionnaire. The 22 measurement items are shown in Table 3. These measurement items were measured on a 5-point Likert scale.

Table 1.

Sources of measurement items.

| Measurement variable | Reference source | Number of measurement items |

|---|---|---|

| Consumers’ negative emotions | Fang et al. (2019) [37], Wei & Lin (2022) [6] | 5 |

| Relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers | Jessica et al. (2015) [18], Wang & Guo (2019) [38] | 4 |

| Relationship quality between consumers and OTAs | Jessica et al. (2015) [18], Liu et al. (2020) [15], Wang & Guo (2019) [38] | 4 |

| Consumers’ forgiveness | Chen et al. (2020) [39], Lee & Cun (2018) [40] | 4 |

| Consumers’ repurchase intention | Lee (2018) [30], Qi & Zhang (2021) [23] | 5 |

Table 3.

Test for reliability and convergent and construct validity.

| Normalized | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Items | load factor | t | Cronbach’s α | CR | AVE |

| Consumers’ negative emotions | 1.I am disappointed with the service recovery | 0.863 | 3.276 | 0.806 | 0.894 | 0.629 |

| 2.I complain about service failure | 0.774 | 2.941 | ||||

| 3. I am angry with the hotel | 0.799 | 2.488 | ||||

| 4.I regret my purchase choice | 0.812 | 3.023 | ||||

| 5.I will not cooperate with service recovery | 0.709 | 5.107 | ||||

| Relationship quality between consumers and tourism supplier | 6.I have a smooth communication with the hotel | 0.894 | 6.449 | 0.735 | 0.847 | 0.583 |

| 7.The hotel fulfilled its commitments | 0.734 | 5.137 | ||||

| 8. I trust the hotel more | 0.726 | 3.908 | ||||

| 9.I have formed emotional dependence on the hotel | 0.682 | 3.012 | ||||

| Relationship quality between consumers and OTAs | 10.The OTA is fair and just | 0.777 | 4.014 | 0.844 | 0.860 | 0.606 |

| 11.The OTA is reliable | 0.743 | 5.138 | ||||

| 12.The OTA is very attractive to me | 0.861 | 6.922 | ||||

| 13. After service recovery, I trust the OTA more | 0.726 | 4.971 | ||||

| Consumers’ forgiveness | 14. I think service failure is inevitable | 0.817 | 4.408 | 0.793 | 0.855 | 0.596 |

| 15.I forgave the service staff | 0.722 | 3.753 | ||||

| 16.Service recovery makes me willing to forgive | 0.697 | 4.626 | ||||

| 17.I accepted the apology from the hotel and OTA | 0.843 | 5.825 | ||||

| Consumers’ repurchase intention | 18.I will continue to book services at OTA | 0.674 | 2.034 | 0.868 | 0.876 | 0.587 |

| 19.I will recommend the OTA to people around me | 0.873 | 3.906 | ||||

| 20.I will become a loyal customer of the OTA | 0.772 | 3.542 | ||||

| 21. I trust the OTA more | 0.765 | 5.857 | ||||

| 22.I will maintain the reputation of the OTA | 0.734 | 6.639 | ||||

3.3. Experimental process

The scenario experiment of this study began on April 19, 2022, and ended on May 25, 2022. The subjects came from some cities and rural areas in Guangxi, China. The scenario experiment strictly followed China’s COVID-19 prevention policy. In addition, to encourage qualified subjects to actively participate in the scenario experiment, the researcher gave each participant in the scenario experiment 50 yuan in cash or a bottle of Guilin Sanhua wine worth 50 yuan. The funds needed were taken from the researcher’s research project funds.

In the implementation of scenario experiments, we required all subjects to carefully read the scenario experimental materials according to the randomly assigned experimental scenarios. In the process of filling out the questionnaire, we gave the participants guidance, including explaining the professional terms and dimension division. A total of 328 subjects filled out the questionnaire, but a small number of questionnaires were unqualified for analysis due to factors such as incomplete filling. There were 306 valid questionnaires. The specific conditions of the subjects are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sample structure of formal experiment.

| One class indicator | Two class indicators | Sample size | Percentage | One class indicator | Two class indicators | Sample size | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 158 | 48.36% | Education | Secondary school and below | 115 | 37.58% |

| Female | 148 | 51.64% | College degree | 97 | 31.70% | ||

| Region | Guilin | 87 | 28.43% | Bachelor, | 76 | 24.84% | |

| Nanning | 72 | 23.52% | master’s, or doctorate | 18 | 5.88% | ||

| Yulin | 69 | 22.54% | Occupation | Enterprise staff | 65 | 21.24% | |

| Pingle | 37 | 12.09% | Professional | 58 | 18.95% | ||

| Yangshuo | 41 | 13.40% | Self-employed person | 51 | 16.66% | ||

| Age | Under 22 years | 77 | 25.16% | Civil service staff | 13 | 4.25% | |

| 23–40 years | 102 | 33.33% | Student | 27 | 8.82% | ||

| 41–59 years | 99 | 32.35% | Farmer | 78 | 25.49% | ||

| Over 60 years | 28 | 9.15% | Other | 14 | 4.58% |

4. Test and analysis of research data

4.1. Reliability and validity

We next tested the reliability and validity of the questionnaire, using the test criteria of Wu (2010), Hair and Black (2006) [41,42]. The reliability analysis is shown in Table 3. Cronbach’s α values of the five variables were 0.806, 0.735, 0.844, 0.793, and 0.868, which confirmed that the reliability of the research data was relatively good.

The standardized load coefficient, combined reliability (CR), and average variance extracted (AVE) of the research data are shown in Table 3. These data meet the test criteria of convergent validity [41]. Table 4 shows that the discrimination validity of the research data is good because the square root of AVE is larger than the other corresponding correlation coefficients. As shown in Table 5, the model of this study is a good model, which indicates that the construction validity is relatively good.

Table 4.

Square root of AVE and correlation coefficient between variables.

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Consumers’ negative emotions | 0.793 | ||||

| 2. Relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers | −0.507 | 0.764 | |||

| 3. Relationship quality between consumers and OTAs | −0.285 | –0.616 | 0.778 | ||

| 4. Consumers’ forgiveness | −0.532 | 0.631 | 0.496 | 0.772 | |

| 5. Consumers’ repurchase intention | −0.438 | 0.473 | 0.597 | 0.628 | 0.766 |

Table 5.

Research model fit.

| Index | χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Index value | 261.862 | 86 | 3.045 | 0.946 | 0.943 | 0.038 | 0.056 |

4.2. Research hypothesis test

4.2.1. Test for direct impact relationship

Because we were worried about the problem of multicollinearity, we carried out centralized analysis of the independent variables and moderating variables. The analysis results confirmed that the variance inflation factor (VIF) was between 4.125 and 6.698, which was lower than 10, confirming that the research model did not have multicollinearity.

In this study, the direct relationship test and the adjustment effect test involve hierarchical linear model (HLM), and the researchers test the data results through HLM6.08 software. It should be noted that at present, some literatures also call multilevel linear model (MLM) analysis [43,44]. In this study, we use the name “hierarchical linear model (HLM)”, because it is easier for readers to understand. After all, this study uses HLM6.08 software to test the data results. HLM is based on the general linear regression analysis model, which can simultaneously process data at individual and group levels [45].

The reason why we chose HLM to analyze the direct and moderating effects of this study is that HLM can effectively solve the problem of solving organizational effects (or background effects), and it has more advantages than traditional linear regression models in terms of parameter estimation, model assumptions and data requirements. The basic assumptions of the conventional linear model (OLS) are normality, linearity, homogeneity of variance and independence between observations. However, in real life, there are many problems with multi-layer nested data structures, and homogeneity and independence of variance are often difficult to establish in these data structures. HLM has the advantage of being able to handle non independent data with multi-layer nested structures [44]. When processing hierarchical data, first establish a regression equation with the first level (individual level) explanatory variables, then use the intercept and slope in the equation as dependent variables, and then use the second level (group level) explanatory variables as independent variables for secondary regression [46]. As shown in Table 6, this study shows the results of HLM analysis, which are used to analyze the direct impact relationship and moderating effects.

Table 6.

HLM analysis of direct impact relationship and moderating effect.

|

Variable |

Relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers |

Relationship quality between consumers and OTAs |

Consumers’ repurchase intention |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | |

| Intercept | 3.438** | 2.599* | 3.281** | 2.784* | 3.627*** | 3.427** | 2.832* | 3.268** |

| Control variable | ||||||||

| Gender | 0.011 | 0.012 | 0.034 | 0.024 | 0.043 | 0.082 | 0.028 | 0.048 |

| Region | 0.008 | 0.014 | 0.008 | 0.045 | 0.017 | 0.033 | 0.091 | 0.027 |

| Age | 0.063 | 0.036 | −0.066 | 0.002 | −0.111 | −0.024 | −0.079 | −0.046 |

| Education | 0.037 | 0.021 | −0.032* | 0.103* | 0.014 | 0.051 | 0.036 | 0.019* |

| Occupation | 0.014 | 0.023 | 0.024 | 0.092 | 0.025 | 0.014 | 0.037 | 0.032 |

|

Independent Variable | ||||||||

| Consumers’ negative emotions | −0.685* | −0.504* | ||||||

| Relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers | 0.723*** | |||||||

| Relationship quality between consumers and OTAs | 0.511* | |||||||

|

Moderating Variable | ||||||||

| Consumers’ forgiveness | 0.246** | |||||||

|

Interaction Item | ||||||||

| Relationship quality between consumers and OTAs × consumers’ forgiveness | 0.324* | |||||||

| R2 | 0.039 | 0.236 | 0.103 | 0.124 | 0.294 | 0.212 | 0.129 | 0.234 |

| ΔR2 | 0.063 | 0.083 | 0.059 | 0.087 | 0.065 | |||

| F | 4.102** | 2.917* | 4.073** | 2.087* | 3.423* | 2.746* | 3.554* | 2.959** |

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Model 2 in Table 6 shows that consumers’ negative emotions reduced the relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers (γ = −0.685, p < 0.05). Model 3 shows that consumers’ negative emotions weakened the relationship quality between consumers and OTAs (γ = −0.504, p < 0.05); thus, H1 and H2 were verified. According to the statistical results of model 5, the relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers improved the relationship quality between consumers and OTAs (γ = 0.723, p < 0.01); thus, H3 passed validation. The research results of model 8 show that the relationship quality between consumers and OTAs improved consumers’ repurchase intention (γ = 0.511, p < 0.05), and H4 was also supported.

4.2.2. Moderating effect test

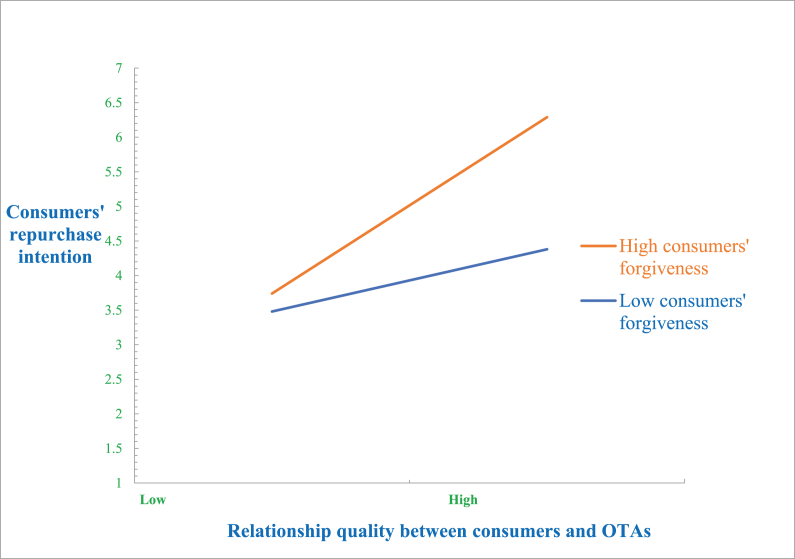

This study draws on the practices of Zhang et al. (2019) and Li et al. (2019) [36,43], and uses HLM6.08 software to test the moderating effect hypothesis (H7). As shown in Table 6, in model 6, the interaction coefficient between the relationship quality between consumers and OTAs and consumers’ forgiveness was positive (γ = 0.324, p < 0.05), confirming that consumers’ forgiveness has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between the relationship quality of consumers and OTAs and consumers’ repurchase intention, supporting H7.

Fig. 2 shows the moderating effect diagram of this study. We can see that when the level of consumers’ forgiveness is low, the relationship quality between consumers and OTAs has a weak promotion of consumers’ repurchase intention (γ = 0.211, p < 0.05), but when the level of consumers’ forgiveness is high, the opposite is true. Therefore, consumers’ forgiveness exerts a positive moderating effect, and H7 is further verified.

Fig. 2.

Moderating effect chart.

4.2.3. Mediating effect test

In the mediating effect hypothesis of this study, H5 and H6 belong to simple mediating effects. According to Preacher et al. (2007) [47], Bootstrap method is most suitable for simple mediating effect test. In terms of the operation method of simple mediating effect, we refer to the practice of Chen et al. (2004), Ma and Zhou (2020) [48,49]. We use model 6 in PROCESS macro to test the mediating effect of H5 and H6. The specific operations are as follows: We install the PROCESS macro into SPSS 25.0, run SPSS 25.0, select “Analyze-Regression-PROCESS” to enter the operation, select the operating variables (independent variables, mediating variables and dependent variables) into the option box, select 6 in the “Model Number”, set the “Bootstrap Samples” to 5000 times, select “Bia Corrected” as the sampling method, set the 95% confidence interval, and click “OK” to run the mediating effect test.

The indicators in Table 7 confirm that the competition model is not a good model, but the chain mediating effect model is a good model. Therefore, the chain mediating effect does exist. In Table 8, the indirect effect value of “consumers’ negative emotions → relationship quality between consumers and OTAs → consumers’ repurchase intention” is equal to 0.219, and the indirect effect value of “consumers’ negative emotions → relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers → relationship quality between consumers and OTAs → consumers’ repurchase intention” is equal to 0.237. Thus, H5 and H6 passed the test.

Table 7.

Test of two models.

|

Model |

χ2 | df | χ2/df | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chain mediating model | 53.072 | 15 | 3.538 | 0.929 | 0.925 | 0.044 | 0.074 |

| Competition model | 127.367 | 19 | 6.704 | 0.743 | 0.787 | 0.071 | 0.124 |

Table 8.

Statistics of mediating effect.

| Mediating effect path | Indirect effect value | Standard error | Upper limit | Lower limit | Effect proportion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Consumers’ negative emotions → relationship quality between consumers and OTAs → consumers’ repurchase intention | 0.219 | 0.007 | 0.325 | 0.113 | 31.60% |

| 2. Consumers’ negative emotions → relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers → relationship quality between consumers and OTAs → consumers’ repurchase intention | 0.237 | 0.008 | 0.357 | 0.114 | 34.20% |

| 3. Total mediating effect | 0.456 | 0.024 | 0.617 | 0.295 | 65.80% |

| 4. Total effect | 0.693 | 0.019 | 0.822 | 0.392 | 100% |

5. Conclusions and discussion

5.1. Conclusion and theoretical significance

First, this research shows that consumers’ negative emotions reduce the relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers, and consumers’ negative emotions reduce the relationship quality between consumers and OTAs. Thus, H1 and H2 have passed verification. In addition, the relationship quality between consumers and tourism suppliers has a positive impact on the relationship quality between consumers and OTAs, and H3 has also passed the test. For these research conclusions, our analysis suggests that under the service failure scenario, it is inevitable for consumers to have negative emotions. They will directly be dissatisfied with the tourism suppliers and vent their anger on the OTA platform, resulting in a chain effect. In previous studies, Qian (2018) and Tan (2019) found that consumers’ negative emotions reduce the relationship quality between consumers and businesses [14,22], but previous studies have rarely involved OTA service recovery, and there are still large unknown “black holes” in this research field. Therefore, compared with previous studies, this study innovates the research scenario, involves OTA service recovery, and expands the empirical research content of relationship quality and negative emotions.

Second, this study confirms that the relationship quality between consumers and OTAs will improve consumers’ repurchase intention and verifies the mediating effect of the two relationship quality variables, supporting H4, H5, and H6. The conclusions of this study develop the findings of Lee (2018), Zhao & Wang (2012), although previous studies have analyzed the impact of relationship quality on consumers’ repurchase intention, their research was related to online shopping and traditional travel agency scenarios and did not involve OTA service recovery scenarios [21,40]. Therefore, compared with previous studies, this study realizes innovation in the research field, introduces relationship quality and consumers’ repurchase intention into the OTA research field, expands the theoretical application scenarios of the two variables, and provides a reference for colleagues in the academic community to carry out OTA service remediation research in the future.

Third, this study also confirms that consumers’ forgiveness has a positive moderating effect on the relationship between the relationship quality of consumers and OTAs and the impact of consumers’ repurchase intention, supporting H7. The research conclusions of this study are comparable with previous studies. This study develops the research conclusions of Ho (2020), Huang & Chang (2020) [32,50]. Existing research has not examined the moderating effect of consumers’ forgiveness on the relationship between relationship quality and consumers’ repurchase intention. Therefore, this study is of great significance for online tourism research and consumer psychology research. We introduce the theory of relationship quality and consumer forgiveness into the field of online tourism research and integrate psychological theory with tourism service theory to better explain consumer psychology and behavior problems in online tourism.

5.2. Practical significance

First, OTAs should formulate a scientific service recovery plan. Based on our research conclusions, consumers’ negative emotions will weaken the relationships between all parties and then affect the willingness of consumers to buy again, which is very harmful to the OTAs and hotels involved. Therefore, OTAs should, with the support of the hotels, organize a service recovery plan formulation group composed of employees, consumers, psychology experts, and tourism experts, including the formulation of scientific emotion management plans. Service recovery should be carried out according to the service recovery plan, and flexible use and adjustments should be made. For example, enterprises should carry out personalized negative emotion counseling according to individual differences among consumers and implement one person one program, to effectively reduce consumers’ dissatisfaction and complaints, improve the quality of relations among all parties, and improve consumers’ repurchase intention.

Second, OTAs and tourism suppliers should cultivate good relationship quality with consumers, which is the key to improving consumers’ repurchase intention. For example, after the service failure of Hotel A, Ctrip (OTA) and Hotel A gave consumers effective service remedies, including refunds, apologies, and cash compensation. The relationship between consumers and Hotel A is improved, and the relationship between consumers and the OTA is also improved. These consumers have the intention to buy again. Therefore, OTA and tourism suppliers should pay attention to improving remediation methods and strategies and use effective scientific methods to calm consumers’ dissatisfaction and anger, rather than confronting consumers, which can intensify the conflict. Service recovery personnel should be good at communicating with consumers, understand their dissatisfaction, and solve their problems pertinently.

Third, OTAs should make it an important task to improve consumers’ willingness to forgive. Take Ctrip (OTA) and Hotel A as examples. Ctrip and Hotel A should strive to guide consumers to understand and forgive the result of service failure. In terms of specific measures, Ctrip and Hotel A should set up an emergency public relations team to explain the reasons for the service failure in detail to consumers, take the initiative to assume responsibility, and carry out service recovery in a fair and just manner. At the same time, through certain material compensation, we should reduce the negative emotions of consumers after service failure, improve the quality of relationships, and improve consumers’ willingness to forgive.

5.3. Limitations and prospects

First, the research content of this study did not include studies on face, cognitive dissonance, or the stereotype effect. These variables may have a certain impact on relationship quality and consumer forgiveness. To improve the scientific nature of the research, in future empirical research on OTA service recovery, we will try to explore the impact of face, cognitive dissonance, the stereotype effect, and other variables.

Second, the source of our research sample was not wide enough. The sample of our scenario experiment came from Guangxi, a frontier province in China. The subjects included citizens and farmers. However, China has a vast territory, and it may not be representative to conduct experiments in only one province. Therefore, in the future, samples for scenario experiments should be taken from many provinces in China. If conditions permit, scenario experiments and comparative studies can also be conducted in some countries in East and Southeast Asia.

Third, the scenario experiment method used in this study has certain limitations. The research data collected in the scenario experiment were all from the subjective evaluation of consumers, which can involve certain cognitive biases. Therefore, in follow-up research, we will also collect data generated by the OTA platform, which can be obtained using web crawler methods, including the time when consumers visit the OTA platform again after service recovery, the number of logins, the number of messages, and the purchase amount.

Production notes

Author contribution statement

Jiahua Wei: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Yi Lian; Qiu Lu: Conceived and designed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Wrote the paper.

Lei Li: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Zhizeng Lu: Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Wenhui Chen: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data.

Hualong Dong: Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

Prof Dr. Jiahua Wei was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China [72262009], Guangxi Natural Science Foundation [2021GXNSFAA220066].

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China [72074058].

Contributor Information

Jiahua Wei, Email: jiahua6688@163.com.

Yi Lian, Email: lianyi63@263.net.

Lei Li, Email: lileiguilin@foxmail.com.

Zhizeng Lu, Email: luzhizeng2022@163.com.

Qiu Lu, Email: 2002021@glut.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Kitsios F., Kamariotou M. Service innovation process digitization: areas for exploitation and exploration. J. Hospit. Tourism Technology. 2021;12(1):4–18. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu Z.J., Jia B.Y., Zhao Y.Z. Research on the impact of OTA online reputation system on consumers' purchase decision. China Soft Sci. 2021;(1):147–155. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spreng R.A., Harrell G.D., Mackoy R.D. Service recovery: impact on satisfaction and intentions. J. Serv. Market. 1995;9(1):15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia W., Zhao Z. Will service recovery lead to customer satisfaction: from the perspective of customer emotion. J. Northeast. Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2018;20(1):44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Browning V., So K.K.F., Sparks B. The influence of online reviews on consumers' attributions of service quality and control for service standards in hotels. J. Trav. Tourism Market. 2013;30(1–2):23–40. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei J.H., Lin X. Research on the influence of compensation methods and customer sentiment on service recovery effect. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excel. 2022;33(5–6):489–508. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inkson C. Service failures and recovery in tourism and hospitality: a practical manual. Tourism Manag. 2019;70(2):176–177. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ashraf H.A., Manzoor N. An examination of customer loyalty and customer participation in the service recovery process in the Pakistani hotel industry: a pitch. Account. Manag. Inform. Sys. 2017;16(1):199–205. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo Y.P. Situational factors, consumer sentiment and online impulse buying. Bus. Econ. Res. 2021;(6):68–71. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song H., Kim J.H. The cause-effect relationship between negative food incidents and tourists' negative emotions. Int. J. Hospit. Manag. 2021;95(5) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu X.Y. Research on the effect of service staff and customer emotional interaction. Econ. Manag. 2011;33(12):77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu B.Q., Li S.D., Zhang C.B. Research on the relationship between emotional response and post purchase behavior after service failure, Modern Finance and Economics. J. Tianjin Univers. Financ. Econom. 2018;38(5):91–100. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wei J.H. The impacts of perceived risk and negative emotions on the service recovery effect for online travel agencies: the moderating role of corporate reputation. Front. Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.685351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan B.H. Guangxi Normal University; 2019. Research on the Relationship between Service Recovery Quality, Relationship Quality and Customer Loyalty under B2C Mode: the Regulatory Role of Customer Participation. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu W., Wang Z.S., Zhao H. Research on the influence of relationship quality with enterprises before customer churn on win back intention. J. Manag. 2020;(6):891–898. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li D., Yang J.J., Deng C. The effect mechanism of relationship quality on enterprise knowledge creation performance: a regulated intermediary model. Scientif. Technolog. Progr. Countermeas. 2021;38(21):108–117. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei F.X. Empirical study on the correlation between customer perceived service quality and customer satisfaction. J. Tianjin Busin. Univer. 2003;(1):21–25. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jessica J.H., David A.G., Ryan C.W. Reciprocity in relationship marketing: a cross-cultural examination of the effects of equivalence and immediacy on relationship quality and satisfaction with performance. J. Int. Market. 2015;23(4):67–84. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong X.Z. Research on online customer loyalty of platform shopping websites : a double intermediary path based on relationship quality and website attachment. J. Market. Sci. 2015;11(4):104–128. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jia S.H., Wu B., Wang Chengzhe. An Empirical Study on the influence of resource dependence and relationship quality on alliance performance. Sci. Res. (N. Y.) 2007;(2):334–339. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao Y.S., Wang S.H. The impact of service failure on relationship quality and customer repurchase intention in online shopping: an empirical study based on the regulation of relationship type. J. Cent. S. Univ. 2012;18(3):123–130+134. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qian J.J. Anhui University of Finance and Economics; 2018. Research on the Impact of Online Shopping Service Recovery on Customer Secondary Satisfaction. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qi Y.Z., Zhang M.X. The impact of multi-channel integrated service quality of new retail enterprises on repurchase intention: the regulatory effect of customer involvement. China Circul. Econ. 2021;35(4):58–69. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mei J. The impact of virtual community service recovery on consumers' repurchase intention: from the perspective of customer citizenship behavior. Bus. Econ. Res. 2016;(6):46–48. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin C.H., Lekhawipat W. Factors affecting online repurchase intention. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2014;114(4):597–611. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chatzoglou P., Chatzoudes D., Savvidou A., Fotiadis T., Delias P. Factors affecting repurchase intentions in retail shopping: an empirical study. Heliyon. 2022;8(9) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu X., Wang X., Li Y., Haghighi M. Business intelligence in online customer textual reviews: understanding consumer perceptions and influential factors. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017;37(6):673–683. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitsios F., Kamariotou M., Karanikolas P., Grigoroudis E. Digital marketing platforms and customer satisfaction: identifying eWOM using big data and text mining. Appl. Sci. 2021;11(17) Article 8032. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Z.J., He J., Li C., Yu Y.F. Analysis on the repurchase intention of star hotel customers in the context of service recovery. J. Yanbian Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2018;51(1):78. 85+141-142. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee J.B. The Effects of relationship marketing of land operator on relationship quality and repurchase intention. J. Tourism Manag. Res. 2018;22(7):419–437. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ran Y., Wei H., Li Q. Forgiveness from emotion fit: emotional frame, consumer emotion, and feeling-right in consumer decision to forgive. Front. Psychol. 2016;7(1775):1–16. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang Z., Chang Z.P. Online service recovery, consumer forgiveness and sustained Trust: based on the test of mediating and moderating effects. Bus. Econ. 2020;(3):97–99. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun N.J. Review and prospect of foreign consumer forgiveness research. China's Circul. Econom. 2012;26(4):86–90. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ma R.J., Fan W.Q., Liu J.W. Pure text or "expression"? The influence of the form of apology on consumers' willingness to forgive: an intermediary perspective of empathy. Nankai Manag. Rev. 2021;24(6):187–196. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quan D.M., Li H.C. Research on the relationship between brand trust, e-commerce service recovery and consumer repurchase: based on the scenario analysis of consumer forgiveness after online shopping service failure. Price Theory Prac. 2021;(4):129–132+170. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Y.J., Shang G.Q., Zhang J.W., Zhou F.F. Overqualification and employee performance: a perspective of psychological rights. Manag. Rev. 2019;31(12):194–203. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fang S.J., Li Y.Q., Fu Y.X. Reparation or money: research on service recovery strategy of tourist attractions based on emotional infection theory. Journal of Tourism. 2019;34(1):44–57. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang X.H., Guo Y.F. Research on the impact of platform e-commerce reputation on platform seller performance: based on the research perspective of customer relationship quality. J. Southwest Univer. Nationalit. 2018;(11):124–131. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen S.Y., Wei H.Y., Ran Y.X., Meng L. Rally or repeat the mistakes: the impact of new starting point thinking and brand crisis types on consumer forgiveness. Nankai Manag. Rev. 2020;23(4):49–58+ 83. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee Y.L., Cun J.A. Study on consumer confusion by consumer information search types. J. Consum. Stud. 2018;29(2):95–121. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu M.L. Chongqing University Press; 2010. Structural Equation Model: Operation and Application of Amos. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hair J.F., Black B. Prentice Hall Press; 2006. Multivariate Data Analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li P., Peng Y.N., Kang J. Research on the Impact of platform market assets on business loyalty: the regulatory effect of platform competition. Manag. Rev. 2019;31(2):103–118. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ren Y.K., Zhao S.M., Du H.F. Rural development and farmer works site selection: - based on HLM model. J. Agric. Fores. Econom. Manag. 2020;(2):244–251. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu Y. The application of multilevel linear analysis model in network collaborative learning. Open Educ. Res. 2011;17(1):80–85. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Su T., Yang H.J., Xian X.J., Tao X.F., Cao X.L. A study on the influencing factors of rural households' income difference in suburban villages based on HLM model: a case study of 1441 rural households in Xi’an. Agric. Res. Regionaliz. China. 2020;(4):273–282. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Preacher K.J., Rucker D.D., Hayes A.F. vol. 42. Multivariate Behavioral Research; 2007. pp. 185–227. (Addressing Moderated Mediation Hypotheses: Theory Methods and Prescriptions). 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chen R., Zheng Y.H., Liu W.J. Mediation effect analysis: principle, program, Bootstrap method and its application. J. Market. Sci. 2013;9(4):120–135. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ma C., Zhou W.B. The influence mechanism of whole situation support on the innovation behavior of skilled employees: the chain intermediary effect of innovation efficacy and work engagement. Finance Econ. 2020;(1):95–103. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ho K.K. The influence of subjective temporal distance on consumer brand forgiveness. Korean Manag. Consulti. Rev. 2020;20(1):265–273. [Google Scholar]