Abstract

Objectives

Buprenorphine is a highly effective medication for the treatment of opioid use disorder, but it can cause precipitated withdrawal (PW) from opioids. Incidence, risk factors, and best approaches to management of PW are not well understood. Our objective was to describe adverse outcomes after buprenorphine administration among emergency department (ED) patients and assess whether they met the criteria for PW.

Methods

This study is a case series using retrospective chart review in a convenience sample of patients from 3 hospitals in an urban academic health system. This study included patients who were reported by clinicians as potential cases of PW. Relevant clinical data were abstracted from the electronic health record using a structured retrospective chart review instrument.

Results

A total of 13 cases were included and classified into the following 3 categories: (1) PW after buprenorphine administration consistent with guidelines (n = 5), (2) PW after deviating from guidelines (n = 4), and (3) protracted opioid withdrawal with no increase in Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale score (n = 4). A total of 11 patients had urine drug testing positive for fentanyl, and 11 patients received additional doses of buprenorphine for symptom management. Of the patients, 5 had self‐directed hospital discharges, and 6 were ultimately discharged with prescriptions for buprenorphine.

Conclusions

Cases of adverse outcomes after buprenorphine administration in the ED and hospital meet criteria for PW, although some cases may have represented protracted opioid withdrawal. Further investigation into the incidence, risk factors, management of PW as well as patient perspectives is needed to expand and sustain the use of buprenorphine in EDs and hospitals.

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background

Implementation of buprenorphine protocols in emergency departments (EDs) has become a public health priority with the goal of increasing low‐barrier access to this evidence‐based treatment. 1 , 2 Buprenorphine is a partial mu‐opioid agonist with a high affinity for the mu‐opioid receptor. 3 Because of its pharmacologic profile, a risk of initiating this medication is that it can displace lower affinity agonists from opioid receptors and cause precipitated opioid withdrawal (PW). 3 Although definitions vary, PW is characterized by a rapid worsening of opioid withdrawal symptoms shortly after buprenorphine administration. 4 To avoid PW, guidelines recommend that buprenorphine should only be administered after patients experience moderate to severe withdrawal, typically 6 to 24 hours after the last opioid use. 5

1.2. Importance

Adverse outcomes from buprenorphine induction are associated with poor retention in opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment for patients and may deter further implementation efforts. 6 , 7 However, the incidence and risk factors for PW have not been well described in any population. 4 , 8 Emerging evidence suggests that the prevalence of fentanyl may further complicate buprenorphine induction. 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 In addition, inadequate treatment of withdrawal may discourage patients from future use of buprenorphine. 6 Newer strategies have altered traditional buprenorphine protocols in individuals who use fentanyl, including low‐dose induction, high‐dose induction, and deferral of treatment for longer periods of abstinence.

1.3. Objective

In this study, we describe a series of cases in which emergency and hospital clinicians reported adverse outcomes after the administration of buprenorphine. We describe the characteristics of patients who experienced these complications, the progression of withdrawal symptoms over time, and the strategies used to manage symptoms. The goals were to characterize common features of these events, including whether they met the criteria for PW and whether the induction protocols were followed, and generate hypotheses for future studies examining the incidence, prevention, and management of precipitated withdrawal.

The Bottom Line

Buprenorphine is a highly effective medication for the treatment of opioid use disorder, but it can cause precipitated withdrawal. In this case series of 13 emergency department patients with reported precipitated withdrawal, some cases met the criteria, whereas others resembled protracted opioid withdrawal. Nearly all patients tested positive for fentanyl, used opioids in the preceding 24 hours, and received subsequent doses of buprenorphine for symptom control. These observations underscore the challenges that concern for precipitated withdrawal may pose for buprenorphine initiation in acute care settings.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study design and setting

This study is a case series using a retrospective chart review in a convenience sample of patients from hospitals in an urban academic health system. The study period was December 2020 to March 2022. During the study period, the health system implemented a coordinated program to increase buprenorphine treatment for OUD in acute care hospitals and EDs. 11 The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board determined this study was exempt from review. This study followed recommended guidelines for reporting case series. 12 , 13

2.2. Selection of participants

This study included patients identified by an emergency or hospitalist clinician as having an adverse outcome of worsening withdrawal symptoms after buprenorphine administration. As part of a quality improvement initiative, cases were referred for review at the discretion of the treating clinician via messaging in the electronic health record (EHR) to a study author (J.P.), a physician with expertise in addiction medicine, emergency medicine, and medical toxicology. 11 All patients initially presented to the ED; however, this study included cases in which buprenorphine was administered either in the ED or inpatient ward within 1 day of admission. For additional context, we extracted EHR data for patients during the study period who were administered buprenorphine but not reported to have concern for PW, although we do not directly compare characteristics between these groups nor intend to estimate PW incidence within this population.

2.3. Measurements and outcomes

Relevant clinical data were abstracted from the EHR. We developed a structured chart review instrument to standardize the abstraction of chart elements, which is available in Supplement S1, and developed according to optimal practices for retrospective chart review. 14 After pilot testing and training with senior members of the study team (A.S.K. and J.P.), 2 unblinded chart reviewers (A.S. and S.F.) independently reviewed 2 patient charts, selected at random, to compare the reliability of the instrument. Interrater reliability was calculated at 97%. 15 The remainder of the charts were abstracted by 1 reviewer (S.F.). Any chart elements that were ambiguous during abstraction were resolved through discussion with the study team. To describe the characteristics of study participants in the context of all ED patients who were administered buprenorphine during the study period, we used additional data extracted from the EHR as previously described. 11

For all participants, we used the medication administration record to identify the dose and timing for medication administration. The first dose of buprenorphine administered in the ED or hospital setting was labeled as the anchor event before the adverse outcome suspected to represent PW. We then identified the values, individual components, and timing of all Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) scores recorded in the EHR using a structured flowsheet tool as well as clinician documentation. In addition to structured COWS documentation, we extracted additional free‐text descriptions of symptoms attributed to PW from physician and nursing documentation.

We identified additional patient and clinical characteristics through the systemic review of EHR problem lists and clinical encounters within the prior 6 months. Using physician and nursing documentation, we identified patient‐reported patterns of substance use, including time and modality of last illicit opioid use. We obtained the results of urine drug testing (UDT) collected during the encounter. Of note, the routine UDT performed in this health system detects fentanyl and reports it separately from other opioids. Finally, we extracted the available data on the clinical course after buprenorphine administration, including the time to symptom improvement and patient disposition.

2.4. Data analysis

Analysis of the extracted data focused on 2 main objectives. First, we determined whether cases met the criteria for PW and whether clinicians deviated from the local buprenorphine induction guidelines that existed during the study period (Supplement S2). We defined PW as an increase in COWS score by 6 within 2 hours of receiving buprenorphine and/or documentation that specifically describes acutely worsening withdrawal symptoms. 4 , 16 , 17 We also defined protracted opioid withdrawal as a persistent elevation in the COWS score for 2 hours after buprenorphine administration without evidence of acute increase. 4 We then classified cases according to the following categories: (1) PW after guideline‐based buprenorphine administration, (2) PW after deviating from guideline‐based buprenorphine administration, or (3) protracted opioid withdrawal, characterized by no acute change in recorded COWS score or other specific documentation of acutely worsening withdrawal symptoms.

The second objective was to describe the clinical course of patients after the event, including medications administered to manage withdrawal symptoms, duration of symptoms, and patient outcomes. We performed a qualitative analysis of free‐text descriptions of clinician documentation on the features and clinical course of PW that were not captured in quantitative measures. Descriptive tables and figures were created using Microsoft Office 2011.

3. RESULTS

A total of 14 cases were referred to the study team. We excluded 1 case after referral because the patient received buprenorphine before ED arrival, leaving 13 cases for review.

3.1. Patient and clinical characteristics

Demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The mean age of the patients was 37.0 years (SD, 10.1). A total of 7 (54%) patients were non‐Hispanic Black, 4 (31%) were non‐Hispanic White, and 2 (15%) were Hispanic. Of the patients, 10 (77%) presented to the ED for chief complaints related to OUD, including 5 (39%) for symptoms of withdrawal, 3 (23%) seeking treatment, and 2 (15%) for medical complications of OUD. We compare key characteristics between the study participants and ED patients who were administered buprenorphine but were not reported as having concern for precipitated withdrawal in Supplement S3.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics (N = 13)

| Patient characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 37.0 (10.1) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 7 (53.8) |

| Female | 6 (46.2) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Non‐Hispanic White | 4 (30.8) |

| Non‐Hispanic Black | 7 (53.8) |

| Hispanic | 2 (15.4) |

| Mood disorder, n (%) | 6 (46.2) |

| Anxiety disorder, n (%) | 3 (23.1) |

| Psychosis, n (%) | 1 (7.7) |

| ED visits in preceding 1 year, mean (SD) | 3.0 (5.7) |

| Hospitalizations in preceding 1 year, mean (SD) | 1.7 (3.0) |

| Stably housed, n (%) | 8 (61.5) |

| Reason for ED visit, n (%) | |

| Opioid withdrawal symptoms | 5 (38.5) |

| Treatment for OUD | 3 (23.1) |

| Medical complication of OUD a | 2 (15.4) |

| Medical | 3 (23.1) |

| Setting of buprenorphine induction, n (%) | |

| ED | 9 (69.2) |

| Hospital | 4 (30.8) |

| ED disposition, n (%) | |

| Discharge to self‐care | 2 (15.4) |

| Discharge to OUD treatment facility | 2 (15.4) |

| Left against medical advice | 0 (0.0) |

| Acute care hospital admission | 9 (69.2) |

| Hospital disposition (n = 9), n (%) | |

| Discharge to self‐care | 2 (15.4) |

| Discharge to OUD treatment facility | 1 (7.7) |

| Left against medical advice | 5 (38.5) |

| Deceased | 1 (7.7) |

| Primary encounter diagnosis, a n (%) | |

| OUD‐related | 7 (53.4) |

| Infectious disease | 4 (30.8) |

| Other medical | 2 (15.4) |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; OUD, opioid use disorder.

OUD‐related category includes opioid use disorder, opioid withdrawal, opioid dependence, opioid abuse, and other substance use disorders. Infectious disease category includes sepsis and pneumonia, cellulitis, abscess, endocarditis, spinal epidural abscess, and osteomyelitis. Other medical includes all other diagnosis that did not fall into either of the aforementioned pre‐specified categories, for example, stroke, heart failure, or acute kidney injury.

Clinical data relevant to buprenorphine induction are shown in Table 2. For the last illicit opioid used, 6 (46%) patients reported fentanyl alone, 2 (15%) reported heroin alone, 4 reported both fentanyl and heroin (31%), and 1 patient reported “Percocet” (8%). Of the 12 patients for whom UDT was collected, 11 (92%) were positive for fentanyl. The time since last reported opioid use varied from <12 hours (5, 39%), between 12 and 24 hours (7, 54%), or >24 hours (1, 8%).

TABLE 2.

Selected clinical and historical data for individual patients related to buprenorphine administration

| Patient | Total dose of buprenorphine before event, mg | COWS preceding buprenorphine | COWS after buprenorphine | Last reported illicit opioid used | Reported time since last use, hours | Modality of use | Other reported substance use | UDT results | Opioid agonist given before buprenorphine | Concurrent adjunctive medications a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category 1: precipitated opioid withdrawal | ||||||||||

| 1 | 8 | 13 | 22 |

Fentanyl Heroin |

12–24 | Not reported | None |

Fentanyl Other opioid b |

No |

Clonidine Lorazepam |

| 2 | 8 | 8 | 21 | Fentanyl | 12–24 | Injection | None |

Fentanyl Other opioid Stimulant c |

No |

Ondansetron Acetaminophen |

| 3 | 2 | 12 | 19 | “Percocet” d | 12–24 | Oral | THC |

Fentanyl Stimulant Benzodiazepine THC |

No | None |

| 4 | 4 | 14 | 23 | Fentanyl | >24 | Injection | None |

Fentanyl Stimulant |

No | None |

| 5 | 4 | 13 | 21 |

Fentanyl Heroin |

<12 | Injection |

Alcohol Cocaine Benzodiazepine |

Fentanyl Other opioid Stimulant Benzodiazepine THC |

No |

Acetaminophen Hydroxyzine Ketorolac |

| Category 2: precipitated opioid withdrawal after nonstandard buprenorphine initiation | ||||||||||

| 6 | 2 | 5 | 10 |

Fentanyl Heroin |

<12 | Injection Nasal |

Cocaine Benzodiazepine K2 |

Fentanyl Other opioid Stimulant Benzodiazepine |

Yes |

Clonidine Cyclobenzaprine Hydroxyzine Lorazepam |

| 7 | 4 | 5 | 15 | Fentanyl | <12 | Injection |

Alcohol THC Methamphetamine LSD PCP |

Not collected | No |

Clonidine Diphenhydramine Lorazepam Metoclopramide |

| 8 | 8 | 7 | 12 | Heroin | <12 | Not reported |

THC Methamphetamine |

Fentanyl Other opioid Stimulant THC |

No | None |

| 9 | 4 | 6 | 21 |

Fentanyl Heroin |

<12 | Nasal |

Cocaine Benzodiazepine |

Fentanyl Other opioid Stimulant THC |

No | None |

| Category 3: protracted opioid withdrawal | ||||||||||

| 10 | 2 | 17 | 17 | Fentanyl | 12–24 | Nasal |

Alcohol THC |

Fentanyl THC |

No | None |

| 11 | 4 | 11 | 10 | Heroin | 12–24 | Injection |

Alcohol THC Cocaine Benzodiazepine |

Fentanyl Other opioid Stimulant Benzodiazepine THC |

No | Chlordiazepoxide |

| 12 | 4 | 12 | 11 | Fentanyl | 12–24 | Nasal | Cocaine |

Fentanyl Other opioid |

No | Ondansetron |

| 13 | 2 | 13 | 17 | Fentanyl | 12–24 | Injection |

Cocaine Benzodiazepine |

None | Yes | None |

Abbreviations: COWS, Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale; K2, synthetic tetrahydracannibinol; LSD, lysergic acid diethylamide; PCP, phencyclidine; THC, tetrahydracannabinol; UDT, urine drug testing.

Given at the same time or at most 1 hour before buprenorphine.

Other opioid category includes codeine, oxycodone, morphine, hydromorphone, oxymorphone, buprenorphine, and norbuprenorphine (no samples tested positive for methadone).

Stimulants include amphetamine, methamphetamine, and cocaine.

Patient‐reported brand name referring to oral oxycodone–acetaminophen.

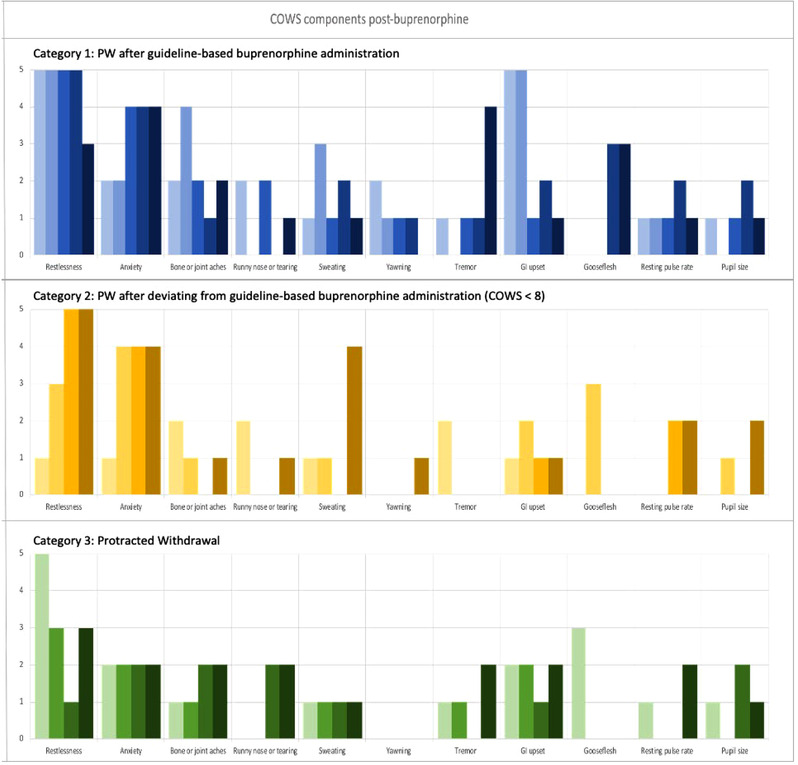

Individual components of the recorded COWS score before and immediately after buprenorphine administration are shown in Figures 1 and 2. The median preceding COWS score was 12 (interquartile range [IQR], 7–13; range, 5–17). Commonly recorded signs or symptoms included anxiety (n = 12, 92%), restlessness (n = 10, 77%), and bone and joint aches (n = 11, 85%). Infrequently recorded signs and symptoms included piloerection (n = 5, 39%) and mydriasis (n = 4, 31%).

FIGURE 1.

Individual components of COWS score recorded before buprenorphine administration for individual patients by patient category. Each unique color represents a score for a specific individual study participant (N = 13). COWS components are arrayed from left to right, with the total score equaling the sum of the individual components (restlessness, anxiety, bone or joint aches, sweating, yawning, tremor, GI upset, gooseflesh, resting pulse rate, and pupil size). The top panel (blue shades) indicates patients in category 1 (n = 5, PW after guideline‐based buprenorphine administration), the middle panel (yellow shades) shows patients in category 2 (n = 4, PW after deviating from guideline‐based buprenorphine administration), and the bottom panel (green shades) shows patients in category 3 (n = 4, protracted opioid withdrawal). COWS, Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale; GI, gastrointestinal; PW, precipitated opioid withdrawal

FIGURE 2.

Individual components of COWS score recorded after buprenorphine administration for individual patients by patient category. Each unique color represents a score for a specific individual study participant (N = 13). COWS components are arrayed from left to right, with the total score equaling the sum of the individual components (restlessness, anxiety, bone or joint aches, sweating, yawning, tremor, GI upset, gooseflesh, resting pulse rate, and pupil size). The top panel (blue shades) indicates patients in category 1 (n = 5, PW after guideline‐based buprenorphine administration), the middle panel (yellow shades) shows patients in category 2 (n = 4, PW after deviating from guideline‐based buprenorphine administration), and the bottom panel (green shades) shows patients in category 3 (n = 4, protracted opioid withdrawal). COWS, Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale; GI, gastrointestinal; PW, precipitated opioid withdrawal

3.2. Categories of PW

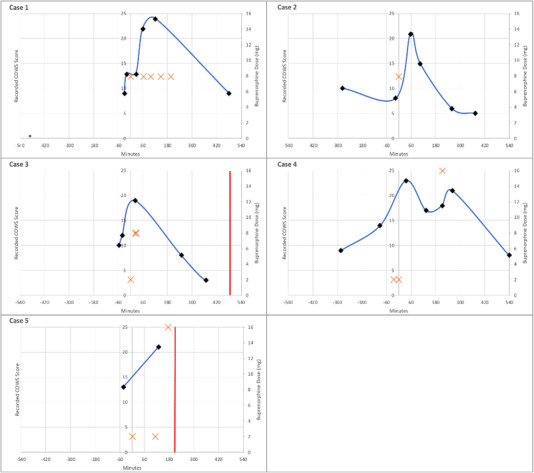

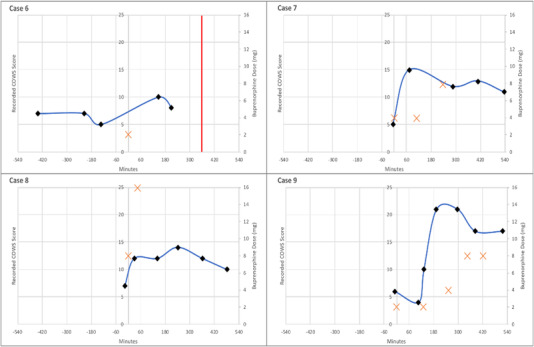

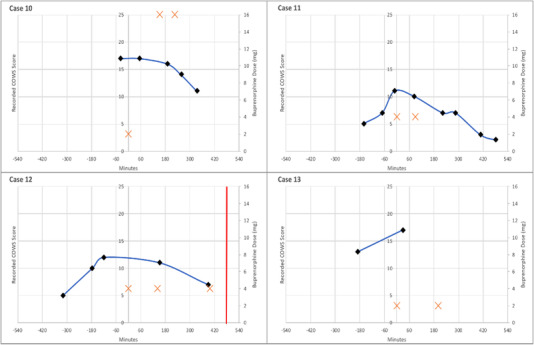

Cases were classified into the 3 categories defined previously. A total of 5 (39%) cases were classified in the first category of PW after guideline‐based buprenorphine administration, and 4 (31%) cases were classified in the second category of PW after deviation from guideline‐based buprenorphine initiation. In all 4 of the cases in the second category, the last recorded COWS score before buprenorphine dosing was <8, which was lower than the treatment guidelines recommended during the study period. Of note, all 4 patients in the second category had used illicit opioids <12 hours before presentation. The remaining 4 (31%) cases were classified in the third category of protracted opioid withdrawal without documentation of acutely worsening opioid withdrawal despite clinicians labeling the case as a potential occurrence of PW. Plots of COWS scores and buprenorphine doses over time for individual patients in each of these categories are shown in Figures 3, 4, 5. A summary of the qualitative analysis of clinician documentation describing PW symptoms is available in Supplement S4.

FIGURE 3.

Plot of recorded COWS, buprenorphine administrations, and discharge events over time (minutes) for patients categorized as precipitated opioid withdrawal (category 1). A black diamond indicates the recorded COWS score at the time (minutes) relative to the first dose of buprenorphine, the orange cross indicates the dose of buprenorphine (mg) at the time (minutes) relative to the first dose of buprenorphine, and the red vertical line indicates the time of departure from the ED or hospital. Note: Case 3 received 2 doses of 8–2 mg buprenorphine–naloxone 5 minutes apart after a recoded COWS score of 19. COWS, Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale

FIGURE 4.

Plot of recorded COWS, buprenorphine administrations, and discharge events over time (minutes) for patients categorized as precipitated opioid withdrawal after non‐standard buprenorphine initiation (category 2). A black diamond indicates the recorded COWS score at the time (minutes) relative to the first dose of buprenorphine, the orange cross indicates the dose of buprenorphine (mg) at the time (minutes) relative to the first dose of buprenorphine, and the red vertical line indicates the time of departure from the acute care setting. COWS, Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale

FIGURE 5.

Plot of recorded COWS, buprenorphine administrations, and discharge events over time (minutes) for patients categorized as protracted opioid withdrawal (category 3). A black diamond indicates the recorded COWS score at the time (minutes) relative to the first dose of buprenorphine, the orange cross indicates the dose of buprenorphine (mg) at the time (minutes) relative to the first dose of buprenorphine, and the red vertical line indicates the time of departure from the acute care setting. COWS, Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale

3.3. Clinical course and outcomes

We summarize the clinical course and management of patients after the anchor event in Table 3. Of the patients, 11 (85%) received additional doses of buprenorphine, with a median total dose receiving 18 mg (IQR, 8–22; range, 4–40). All patients received adjunctive medication, most commonly lorazepam (10, 77%), clonidine (7, 54%), and ondansetron (6, 46%). For 7 cases, symptom improvement was documented, with a median time of 6.5 hours (IQR, 5.25–24; range, 4.5–28). Ultimately, 7 (54%) patients were discharged from the ED or hospital with prescriptions for buprenorphine, 5 (38.5%) patients had patient‐directed medical discharges, and 1 patient expired as a result of medical illness during hospitalization.

TABLE 3.

Clinical data for individual patients on the management of precipitated opioid withdrawal symptoms

| Case | Received additional buprenorphine doses | Total additional buprenorphine dose, mg | Additional adjunctive medications | Patient outcome | Documented time to symptom improvement | Consultations | Discharged with prescription for buprenorphine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category 1: precipitated opioid withdrawal | |||||||

| 1 | Yes | 32 |

Loperamide Lorazepam Ondansetron Acetaminophen Ketorolac |

Discharged from ED after symptoms improved | 7 hours |

Toxicology Peer recovery |

Yes |

| 2 | No | 0 |

Loperamide Ondansetron Oxycodone |

Admitted for medical condition, left AMA | 4.5 hours | None | No |

| 3 | yes | 16 |

Clonidine Loperamide Hydroxyzine Diphenhydramine Diazepam Lorazepam |

Discharged from ED after symptoms improved | 6 hours | None | Yes |

| 4 | yes | 16 |

Clonidine Lorazepam Dicyclomine Ondansetron Gabapentin |

Admitted for medical condition, discharged home | 28 hours |

Psychiatry Peer recovery Toxicology |

Yes |

| 5 | Yes | 16 |

Clonidine Lorazepam Dicyclomine |

Admitted for medical condition, left AMA | No improvement | Peer recovery | No |

| Category 2: precipitated opioid withdrawal after non‐standard buprenorphine initiation | |||||||

| 6 | No | 0 |

Lorazepam Hydromorphone |

Admitted for medical condition, left AMA | No improvement | Peer recovery | No |

| 7 | Yes | 12 | Lorazepam | Admitted for medical condition, discharged to facility for inpatient rehabilitation | Not documented |

Toxicology Psychiatry Peer recovery |

Yes |

| 8 | Yes | 16 |

Lorazepam Hydroxyzine Nicotine |

Admitted to ICU for medical condition, expired | Patient expired | Psychiatry | Expired |

| 9 | Yes | 20 |

Clonidine Dicyclomine Ondansetron Ketorolac |

Discharged to inpatient OUD treatment facility | 20 hours |

Toxicology Peer recovery |

No |

| Category 3: protracted opioid withdrawal | |||||||

| 10 | Yes | 32 |

Clonidine Ketamine Lorazepam Haloperidol Ondansetron Promethazine Acetaminophen Maalox Lidocaine oral |

Admitted for withdrawal symptoms, left AMA | 6 hours |

Toxicology Peer recovery |

Yes |

| 11 | Yes | 4 |

Clonidine Lorazepam Acetaminophen |

Admitted for withdrawal symptoms, discharged home | 7 hours | Psychiatry | Yes |

| 12 | Yes | 8 | Ondansetron | Discharged to inpatient OUD treatment facility | Not documented |

Psychiatry Toxicology |

Yes |

| 13 | Yes | 2 |

Clonidine Hydroxyzine Lorazepam Dicyclomine Ketorolac |

Admitted for medical condition, left AMA | Not documented | Psychiatry | No |

Abbreviations: AMA, against medical advice; ED, emergency department; OUD, opioid use disorder.

4. LIMITATIONS

This study has several limitations. First, this study was a small case series involving a convenience sample of patients. Cases were identified through clinician report to a local addiction medicine expert, possibly leading to selection bias. Second, this study did not include controls to allow comparisons of patients who developed PW and those who did not. Third, this study collected retrospective data from the EHR, limiting the data to that entered by clinicians in the course of clinical care as well as introducing inconsistencies in timing, length of follow‐up, and adequate documentation. Fourth, the chart abstractors were not blinded to the study objective. Finally, an additional unmeasured variable in the local opioid supply is xylazine, which is increasingly prevalent and may impact opioid withdrawal and response to buprenorphine in this population. 18

5. DISCUSSION

In this study, we describe a case series of patients with adverse outcomes after buprenorphine administration. This exploratory study is one of few to examine PW among patients in an acute care setting. There are 4 findings that merit further investigation.

First, we identified that potential instances of PW could be further categorized. Our findings suggest that PW did occur among patients with moderate to severe opioid withdrawal. For other patients, it is possible that gradually worsening or undertreated withdrawal symptoms were interpreted as PW. 16 , 19 In those instances, concern for PW may prevent clinicians and patients from proceeding with additional doses of buprenorphine. 7 Overall, our findings suggest that it may be challenging for acute care clinicians to pinpoint where patients are on the arc of this withdrawal syndrome. 20 , 21 Better discrimination may allow for alternate buprenorphine induction strategies, which may include low‐dose titration with initial doses ranging between 100 and 500 μg or high‐dose treatment with doses >16 mg. 16 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 Of note, all patients in this study received an initial dose ranging from 2 to 8 mg.

Second, we observed common features between cases, although this study was not designed to quantify risk factors for PW. Regardless, it is notable that nearly all patients tested positive for fentanyl. Emerging evidence suggests that fentanyl may increase the risk for PW, possibly due to prolonged storage in adipose tissue. 10 In addition, many patients either reported or tested positive for other substances, which may complicate the interpretation of COWS scores. 4 , 16 It is also worth noting that nearly all patients reported that their last use of opioids was within 24 hours. Finally, we observed that commonly scored components of the preinduction COWS scores were subjective symptoms, such as anxiety and pain, rather than objective signs such as piloerection or mydriasis. For these reasons, recent guidelines have recommended an increased COWS threshold of 13 for buprenorphine induction. 26

Third, patient outcomes fell into 2 general categories. First, 5 of 13 patients had patient‐directed discharges (formerly termed “against medical advice”). Patient‐directed discharges for individuals with OUD are associated with subsequent increased mortality and rehospitalization. 27 , 28 , 29 Second, all other patients who survived hospitalization received a prescription for buprenorphine at discharge, indicating ongoing interest in medication treatment despite a difficult induction. Additional buprenorphine was commonly used to treat PW. As further evidence is generated, it will be essential for clinicians to develop protocols to manage suspected PW and communicate with patients in advance that additional buprenorphine may be indicated.

There is limited evidence regarding the incidence of PW. A supplemental analysis of randomized clinical trial data estimated incidence to be 1% across multiple EDs, whereas a survey of patients using fentanyl who were entering residential treatment found that 36.5% reported having experienced severe withdrawal after buprenorphine. 2 , 4 , 8 , 30 , 31 Going forward, it is essential to describe the full range of suboptimal outcomes after buprenorphine administration in real‐world settings. It is essential to anticipate the negative impact of even rare cases in individual EDs to sustained implementation. Most important, there is an urgent need to address patient concerns about the risks of buprenorphine. 7

In summary, we describe a case series of potential PW after buprenorphine induction among ED or hospitalized patients. Although buprenorphine remains a highly safe and effective medication to treat OUD, anticipation of the possible risk of PW should be considered through discussions with patients as well as protocols for clinicians. More evidence is urgently needed to predict and avoid PW after buprenorphine induction in the fentanyl era.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Anthony Spadaro, Austin S. Kilaru, Sophia Faude, Ashish P. Thakrar, Margaret Lowenstein, and Jeanmarie Perrone conceived the study. Anthony Spadaro, Sophia Faude, and Austin S. Kilaru supervised the conduct of the study and data collection. Margaret Lowenstein, Ashish P. Thakrar, and Jeanmarie Perrone undertook patient identification and recruitment in the study. Anthony Spadaro and Sophia Faude managed the data, including quality control. M. Kit Delgado, Ashish P. Thakrar, Margaret Lowenstein, and Jeanmarie Perrone provided advice on study design. All authors analyzed the data. Anthony Spadaro and Sophia Faude drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. Austin S. Kilaru takes responsibility for the article as a whole.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

Supporting information

Supplementary Information

Biography

Anthony Spadaro, MD, MPH, is a resident physician in the Department of Emergency Medicine at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Spadaro A, Faude S, Perrone J, et al. Precipitated opioid withdrawal after buprenorphine administration in patients presenting to the emergency department: A case series. JACEP Open. 2023;4:e12880. 10.1002/emp2.12880

Supervising Editors: Brittany Punches, PhD, RN; Henry Wang, MD, MS.

Funding and support: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (5K12HS026372‐04).

REFERENCES

- 1. Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta‐analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. D'Onofrio G, O'Connor PG, Pantalon Mv, et al. Emergency department‐initiated buprenorphine/naloxone treatment for opioid dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(16):1636‐1644. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cisewski DH, Santos C, Koyfman A, Long B. Approach to buprenorphine use for opioid withdrawal treatment in the emergency setting. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(1):143‐150. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Whitley SD, Sohler NL, Kunins Hv, et al. Factors associated with complicated buprenorphine inductions. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010;39(1):51‐57. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guo CZ, D'Onofrio G, Fiellin DA, et al. Emergency department‐initiated buprenorphine protocols: a national evaluation. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2021;2(6):e12606. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cunningham CO, Roose RJ, Starrels JL, Giovanniello A, Sohler NL. Prior buprenorphine experience is associated with office‐based buprenorphine treatment outcomes. J Addict Med. 2013;7(4):287‐293. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31829727b2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Silverstein SM, Daniulaityte R, Martins SS, Miller SC, Carlson RG. “Everything is not right anymore”: buprenorphine experiences in an era of illicit fentanyl. Int J Drug Policy. 2019;74:76‐83. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. D'Onofrio G, Perrone J, Herring AA, et al. Low incidence of precipitated withdrawal in emergency department‐initiated buprenorphine, despite high prevalence of fentanyl use. Acad Emerg Med. 2022;29(S1):83‐87. doi: 10.1111/acem.14511 34288254 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Antoine D, Huhn AS, Strain EC, et al. Method for successfully inducting individuals who use illicit fentanyl onto buprenorphine/naloxone. Am J Addict. 2021;30(1):83‐87. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Huhn AS, Hobelmann JG, Oyler GA, Strain EC, Protracted renal clearance of fentanyl in persons with opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;214:108147. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lowenstein M, Perrone J, Xiong RA, et al. Sustained implementation of a multicomponent strategy to increase emergency department‐initiated interventions for opioid use disorder. Ann Emerg Med. 2022;79(3):237‐248. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kempen JH. Appropriate use and reporting of uncontrolled case series in the medical literature. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(1):7‐10.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.08.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kaji AH, Schriger D, Green S. Looking through the retrospectoscope: reducing bias in emergency medicine chart review studies. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64(3):292‐298. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gregory KE, Radovinsky L. Research strategies that result in optimal data collection from the patient medical record. Appl Nurs Res. 2012;25(2):108‐116. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2010.02.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hunt RJ. Percent agreement, pearson's correlation, and kappa as measures of inter‐examiner reliability. J Dental Res. 1986;65(2):128‐130. doi: 10.1177/00220345860650020701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Spadaro A, Long B, Koyfman A, Perrone J. Buprenorphine precipitated opioid withdrawal: prevention and management in the ED setting. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;58:22‐26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2022.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Strain EC, Preston KL, Liebson IA, Bigelow GE. Buprenorphine effects in methadone‐maintained volunteers: effects at two hours after methadone. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;272(2):628‐638. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kariisa M, Patel P, Smith H, Bitting J. Notes from the field: xylazine detection and involvement in drug overdose deaths — United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;70:1300‐1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hailozian C, Luftig J, Liang A, et al. Synergistic effect of ketamine and buprenorphine observed in the treatment of buprenorphine precipitated opioid withdrawal in a patient with fentanyl use. J Addict Med. https://journals.lww.com/journaladdictionmedicine/Fulltext/9000/Synergistic_Effect_of_Ketamine_and_Buprenorphine.98971.aspx. Published online 9000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lowenstein M, Kilaru A, Perrone J, et al. Barriers and facilitators for emergency department initiation of buprenorphine: a physician survey. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(9):1787‐1790. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2019.02.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Walley AY, Alperen JK, Cheng DM, et al. Office‐based management of opioid dependence with buprenorphine: clinical practices and barriers. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(9):1393‐1398. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0686-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Spadaro A, Sarker A, Hogg‐Bremer W, et al. Reddit discussions about buprenorphine associated precipitated withdrawal in the era of fentanyl. Clin Toxicol. Published online 2022;60(6):694‐701. doi: 10.1080/15563650.2022.2032730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moe J, Doyle‐Waters MM, O'Sullivan F, Hohl CM, Azar P. Effectiveness of micro‐induction approaches to buprenorphine initiation: a systematic review protocol. Addict Behav. 2020;111:106551. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thakrar AP, Jablonski L, Ratner J, Rastegar DA, Micro‐dosing Intravenous buprenorphine to rapidly transition from full opioid agonists. J Addict Med. 2022;16(1):122‐124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Klaire S, Zivanovic R, Barbic SP, Sandhu R, Mathew N, Azar P. Rapid micro‐induction of buprenorphine/naloxone for opioid use disorder in an inpatient setting: a case series. Am J Addict. 2019;28(4):262‐265. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Samhsa . Buprenorphine Quick Start Guide. www.findtreatment.samhsa.gov

- 27. Eaton EF, Westfall AO, McClesky B, et al. In‐hospital illicit drug use and patient‐directed discharge: barriers to care for patients with injection‐related infections. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(3):ofaa074. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Southern WN, Nahvi S, Arnsten JH. Increased risk of mortality and readmission among patients discharged against medical advice. Am J Med. 2012;125(6):594‐602. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2011.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Saitz R, Ghali WA, Moskowitz MA. The impact of leaving against medical advice on hospital resource utilization. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(2):103‐107. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.12068.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Herring AA, Vosooghi AA, Luftig J, et al. High‐dose buprenorphine induction in the emergency department for treatment of opioid use disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2117128. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.17128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Varshneya NB, Thakrar AP, Hobelmann JG, Dunn KE, Huhn AS. Evidence of buprenorphine‐precipitated withdrawal in persons who use fentanyl. J Addict Med. November 23, 2021. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000922. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information