Abstract

Despite major structural shifts in the international monetary system over the past six decades, the US dollar remains the dominant international reserve currency. Using a newly compiled database of individual economies’ reserve holdings by currency, this paper finds that financial links have been an increasingly important driver of reserve currency configurations since the global financial crisis, particularly for emerging market and developing economies. The paper also finds a rise in inertial effects, implying that the US dollar dominance is likely to endure. But historical precedents of sudden changes suggest that new developments, such as the emergence of digital currencies and new payments ecosystems, could accelerate the transition to a new landscape of reserve currencies.

Keywords: Reserve currencies, Currency composition, International monetary system

Introduction

The international monetary system has evolved over the past decades in response to major structural shifts in the global economy prompted by trade and financial integration, technological developments, and geopolitical events. More recently, the sustained growth and rapid integration of emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have increased their economic heft and created a less-concentrated structure of global output and trade and a more multipolar global economy (IMF 2016).

Yet the currency composition of international reserves has remained remark- ably stable. The US dollar has been the dominant reserve currency for more than 60 years, notwithstanding the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in the 1970s and the emergence of new reserve currencies such as the euro and the renminbi over the past two decades. The dollar’s reserve currency status has been supported and reinforced by its global use for trade invoicing and cross-border investment, among others, and as an exchange rate anchor.

This paper investigates the drivers of reserve currencies at the global and country level, how these drivers have changed over time, and how they differ across advanced economies (AEs) and EMDEs. In addition to aggregate data from the IMF Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves (COFER) database, the paper carefully compiles and uses a database of individual economies’ reserve holdings by currency.1 The paper finds that inertia and financial links are important drivers of reserve currency shares, and their importance has increased since the global financial crisis (GFC) of 2008–09.

The paper complements the empirical analysis with a discussion of ongoing trends and uncertainties that could accelerate the transition to new reserve currencies. A number of possible factors could lead to an eventual change in the status quo. For instance, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and global supply chain disruptions could alter the global economic landscape; rising geopolitical tensions could trigger strategic shifts in reserve holdings; or technological advances, in particular the emergence of digital currencies and advances in payment systems, could speed up the transition to alternative, and perhaps less stable, configurations of reserve currencies.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 1 outlines what constitutes a reserve currency and provides a short description of current and past trends. Section 3 reviews the existing literature on drivers of reserve currency shares. Section 4 introduces the conceptual framework underpinning the empirical analysis and presents the findings using both global and country-level data. Section 4.1 considers potential triggers for future shifts, and Sect. 4.1.1 offers conclusions.

Current and Past Reserve Currencies

Countries hold foreign exchange reserves to finance balance of payments needs, intervene in foreign exchange markets, provide foreign exchange liquidity to domestic economic agents, and for other related purposes, such as maintaining confidence in the domestic currency and facilitating foreign borrowing. As such, reserves are generally denominated in currencies widely used for international payments and widely traded in global foreign exchange markets.2,3

The accumulation of foreign exchange reserves by the official sector is but one of many examples of the international use of currencies. Other countries’ currencies can be also used by the private sector for external trade invoicing and settlement, cross-border investment, and as a vehicle for financial transactions. Different international uses are complementary and tend to reinforce each other. For instance, widespread use by the private sector for trade invoicing and financial transactions often goes hand-in-hand with official sector use as exchange rate anchor and reserve currency, which, in turn, can bolster credibility and reinforce private sector use. Also, more trade invoicing is often associated with a greater denomination of financial claims (Gopinath and Stein 2018; Chahrour and Valchev 2017).

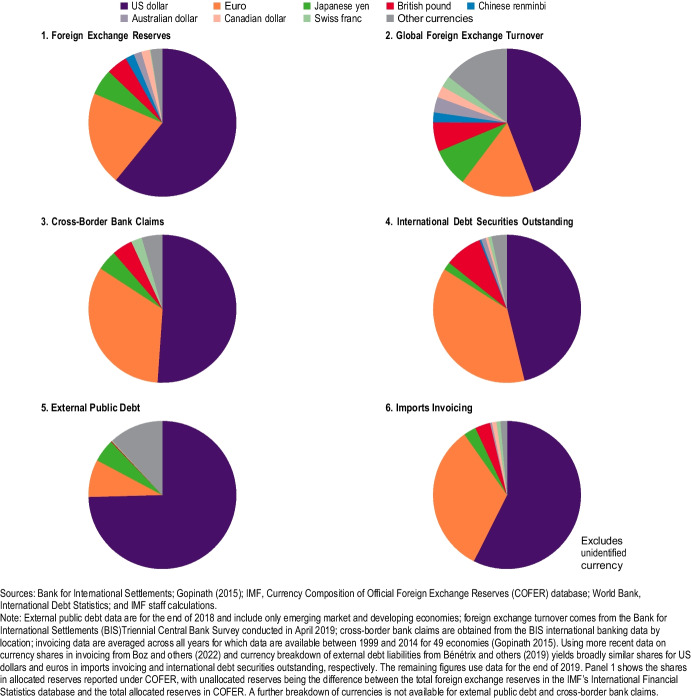

The US dollar is currently the dominant reserve currency, with a share of 61 percent of global reserves at the end of 2019. The euro comes second with 21 percent of reserves, and other currencies’ shares are much smaller still (Fig. 1). The dollar’s leading role as a reserve currency is consistent with its wide international use: it stands out as the currency most traded in the foreign exchange market (44 percent of turnover), and most used for trade invoicing (54 percent of global trade) and financial claim denomination (for example, 51 percent of cross-border bank claims) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Currency Composition of Reserves, Foreign Exchange Turnover, Financial Claims, and Trade Invoicing, 2019 or Most Recent (Percent)

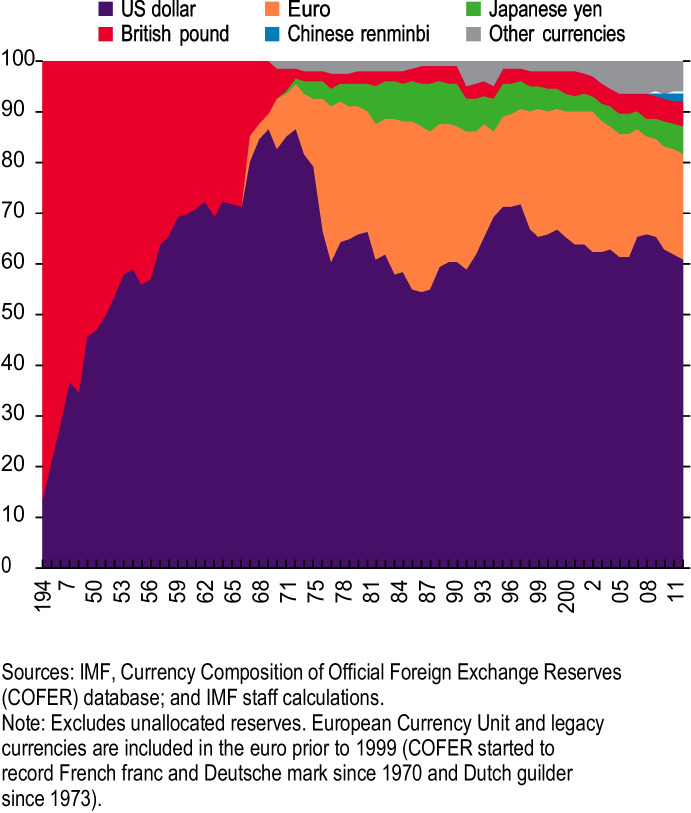

The US dollar has held this dominant position for more than 60 years, notwithstanding significant shifts in the international monetary system (IMS) (Fig. 2). Some of these shifts have included, in chronological order, the creation of the SDR in the 1960s to help address the so-called Triffin dilemma4; the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in the 1970s that diminished the link to the dollar in exchange rate arrangements; the emergence of Japan in the 1980s as a global creditor; the introduction of the euro in 1999; trends toward greater reserve diversification following the GFC5; and China’s efforts to boost the internationalization of the renminbi and promote its reserve currency status over the last decade (Eichengreen et al. 2022). Despite all these changes, the dollar’s share in global reserves has remained above 50 percent, while its share in global foreign exchange turnover has been remarkedly stable at close to 45 percent since 1989 (Fig. 3). And while other currencies, particularly the renminbi, have been reportedly gaining some ground in trade invoicing,6 the dollar’s use for financial asset denomination, in particular EMDEs debt, has been on the rise.

Fig. 2.

Currency Composition of Allocated Reserves, 1947–2019 (Percent of total)

Fig. 3.

Currency Composition of Foreign Exchange Turnover and Financial Claims, 1989–2019 (Percent)

The IMS has often been dominated by a few currencies that were used widely for significant periods of time. In recent decades, these currencies have been the US dollar and, to some extent, the euro (Figs. 2 and 3). The transition from one dominant currency to another has taken anywhere between several years to many decades, but there have also been periods without a dominant currency (Iancu et al. 2020).

Literature Review

The literature examining the drivers of reserve currency shares at the global level finds a significant role for the economic characteristics of reserve issuers, such as their global reach (generally captured by their economic size and/or role in international trade and finance, also aiming to capture “network effects”)7 and credibility (Li and Liu 2008; Eichengreen et al. 2016; Aizenman et al. 2020). Some studies also point to the role of national policies in either supporting or preventing the internation- alization of currencies (Eichengreen et al. 2016).8 Furthermore, some studies capture the reserve currencies’ perceived safety and effective medium of exchange by relating it to the depth and liquidity of onshore and offshore financial markets (Chinn and Frankel 2008).9

In addition to global reach, network effects, and credibility, the literature finds that inertia plays an important role; that is, holding a larger share of a given reserve currency in the past tends to be a good predictor of reserve shares in the future, as discussed by Triffin (1960). This suggests that reserve currency take-up may be nonlinear, with a high degree of inertial bias in favor of the incumbent reserve currency (Frankel 2012). As such, reserve currency choices may be informed less by short-term economic fundamentals and more by historical ties.10 The literature also concludes that, after the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, inertial effects became stronger, which may reflect the higher stability in the US dollar’s share after the shift from the pound to the dollar. By contrast, the network effects seem to be weaker post-Bretton Woods, which may reflect lower switching costs due to advances in financial and transactions technology (Eichengreen et al. 2016).

A few studies argue that geopolitical considerations can also play a role, as countries may choose to hold reserves in a given currency because of geopolitical or strategic considerations, or as a result of military alliances, and so reserve currencies’ perceived safety can be linked to reserve issuers’ geopolitical or military power (Cohen 2015; Kindleberger 1970; Posen 2008; Liao and McDowell 2016). Eichengreen et al. (2019) show that military alliances boosted the shares of the currencies of alliance partners in foreign reserve portfolios by close to 30 percent in the run up to World War I.

Studies using aggregate data, however, fail to account for shifts within individual countries’ portfolios and cannot capture reserve holders’ potential transactional demand (the intended uses of the reserves). Central banks’ reserve portfolio decisions are often influenced by the pattern of a country’s transactional demands, including the structure of its trade and financial payments, and foreign exchange arrangements.11 More specifically, the trade links can be captured by the share of trade with the reserve currency issuer in the absence of granular data on trade invoicing, financial links by the currency composition of public debt or cross-border bank claims, and the foreign exchange market intervention by de facto anchoring to a reserve currency.

The literature using individual country data is relatively sparse due to lack of publicly available data. Studies using confidential COFER country-level data find evidence that the reserve holders’ potential transactional demand for trade and finance-related payments and foreign exchange market intervention drives the currency composition of their reserves (Heller and Knight 1978; Dooley et al. 1989; Eichengreen and Mathieson 2000).12

More specifically, Heller and Knight (1978), using data for 55 countries during 1970–76, find that the exchange rate regime (choice of peg) and trade linkages with reserve issuers matter. In turn, Dooley et al. (1989) show that the currency denomination of debt service payments is also a significant driver. Eichengreen and Mathieson (2000) highlight the stability of the currency composition of reserves over time and in relation to its main determinants (exchange rate links and trade and financial flows) during 1971–95, and find evidence that capital account liberalization in emerging market economies raises the share of currencies from reserve issuers with particularly active financial markets (United States and United Kingdom).

More recent work has focused on the links between reserve currencies and the currencies used for trade invoicing and financial claim denomination. Gopinath (2015), Gopinath and Stein (2018), Gopinath et al. (2020) emphasize the dominance of the US dollar and euro in trade invoicing, beyond direct trade links with the United States and the euro area.13,14 Ito et al. (2015) and Ito and McCauley (2019) also highlight the role of the trade invoicing and financial liabilities denomination, as well as exchange rate comovements with reserve currencies, using publicly available country-level data.

Drivers of Reserve Currencies

This section uses an empirical model to investigate the main drivers of reserve currencies, how their importance has changed over time, and how they differ across AEs and EMDEs. Understanding these drivers could help tackle the question of how and when (if at all) a transition to a new reserve currency configuration might occur, which is discussed in Section 4.1.

This paper overcomes an important gap in the existing literature by carefully compiling and using a database of individual economies’ reserve holdings by currency15. Compared to earlier papers, it also considers a broader range of specifications to check the robustness of the results.

Conceptual Framework

The existing literature emphasizes four key elements in determining reserve currency status:

The economic size/dominance of reserve issuers: In theory, the larger the economy and its role in international trade and financial networks, the more likely its currency will be used for those international transactions and as a reserve asset.

The credibility of reserve issuers: Reserve assets should, in theory, offer a stable store of value over time, and be widely used and traded, emphasizing the importance of reserve issuers’ policy credibility and their financial markets’ depth and liquidity.

The transactional demand of reserve holders: Central banks’ reserve portfolio decisions are likely to be influenced by the intended uses of reserves, particularly for trade- and finance-related payments or foreign exchange market intervention.

Inertia: Reserve currency status tends to change very slowly, inducing inertia. There is a strong inertial bias in favor of using whichever currency has been the reserve currency in the past. Network effects exacerbate this inertia and create strong path dependence.

Data

The analysis in this paper relies on aggregate data from the IMF COFER database, Eichengreen et al. (2016), and individual country data collected from a select group of central banks.

Aggregate reserve currency shares cover the period 1947–2018 and are sourced from Eichengreen et al. (2016) before 1995 and COFER since 1995.16 The COFER database contains data reported to the IMF on a voluntary and confidential basis. As of the end of 2019, there are 149 reporters accounting for roughly 94 percent of global reserves.17 Individual responses are confidential, and only the aggregate data are publicly available.18

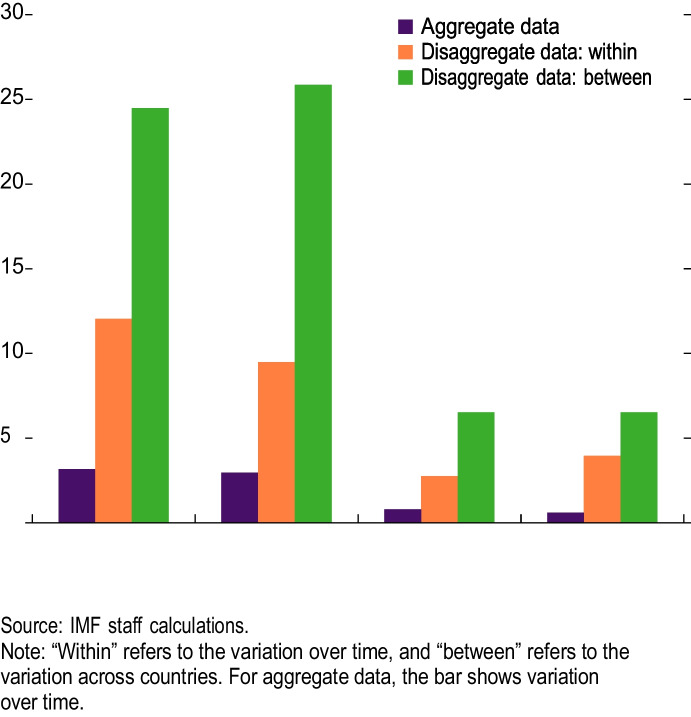

Aggregate data may mask significant shifts within individual countries’ portfolios, potentially over-emphasizing inertia. Indeed, the variation in individual countries’ reserve currency shares is significantly higher than in the aggregate data (Figure 4). Furthermore, the use of country-level data allows for the examination of more granular drivers—for instance, trade or financial links to the reserve issuer or its currency and the de facto use of the reserve currency as an anchor. It can also provide additional insights into how aggregate shares may evolve in the future.

Fig. 4.

Variation (S.D.) in Reserve Currency Shares, 1999–2018

Individual country reserve currency shares are compiled using various central bank publications for 57 economies—19 AEs and 38 EMDEs—over the period 1999–2018. Lack of trade and financial data for some countries further limits the sample to 10 AEs and 32 EMDEs, accounting for 28 percent of global reserves in 2018.19

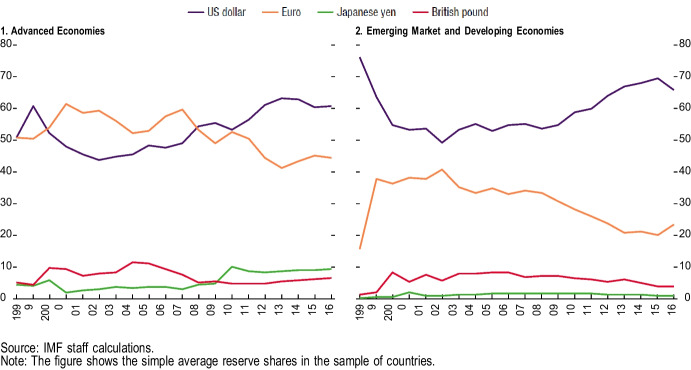

Country-level data confirm the main trend observed in the aggregate data: the average share of US dollar-denominated reserves slipped some- what following the introduction of euro but recovered after the GFC and the eurozone debt crisis (Figure 5). In addition, the average share of euro-denominated reserves is higher in AEs compared to EMDEs, most likely due to the country composition in each sample, but has trended down forboth groups of countries over the sample period.20 The share of British pound has been relatively small at about 4–6 percent in the last decade, while the Japanese yen experienced a slight surge after the GFC in AEs and remains negligible in EMDEs.

Fig. 5.

Disaggregated Data: Average Reserve Shares (Percent)

Drivers of Reserve Currencies using Aggregate Data

Empirical Specification

Building upon previous literature, we investigate global reserve currency shares using data sourced from Eichengreen et al. (2016) before 1995 and COFER since 1995, and covering the period 1947–2018. The core specification, in line with the existing literature, considers the three factors typically found to be important drivers of aggregate reserve shares: inertia, global reach/size, and credibility.21 Specifically, the aggregate reserve share of currency i in year t is modeled as:

in which:

αi is a currency random/fixed effect

δt is a time fixed effect

GDP Share is the share of the reserve issuer’s economy in global GDP

Credibility is the average appreciation of the reserve issuer’s currency against the SDR in the previous five years.

The methodology improves on previous studies. The baseline specification is a fixed effects model (for currencies and time), as the unobserved effects appear to be systematic (that is, correlated with predictors).22 The Hausman test rejects random effects and the Arellano-Bond (1991) estimator has limitations due to the small cross section relative to the time horizon (Arellano 2003).

We also split the sample into 1947–98 and 1999–2018 to assess whether the importance of different drivers has changed since the introduction of the euro. The Deutsche mark, the French franc, and the Dutch guilder are used prior to 1999, and the euro is used starting in 1999.23

Results

Results under the baseline specification highlight the importance of inertia and credibility (Table 1)24:

Inertia: Consistent with previous literature, inertia effects are large and significant across econometric specifications. The coefficients on lagged reserve shares are about 0.9, indicating a high degree of persistence.

Credibility: Coefficients are significant over the full sample period, but the economic effect is more limited, with a 10 percent appreciation of a currency associated with a 0.4 percentage point increase in its share of global reserves.

Size: In contrast to previous literature, the relative size of the economy of the reserve currency issuer, measured by its share of global GDP, is not robustly significant across specifications. Although the coefficient on size is positive and significant in the random effects specification, consistent with Eichengreen et al. (2016), the sign is negative in other specifications and insignificant when using fixed effects.

Time variation: Results (Table 1, columns 4 and 5) indicate that inertia and credibility effects may have been more important in the earlier period (1947–98).

Table 1.

Baseline Specification

| Fixed Effects | Random Effects | Arellano-Bond | Fixed Effects | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1947–2018 | 1947–2018 | 1947–2018 | 1947–1998 | 1999–2018 | 1947–2018 | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Lagged Reserve Share | 0.888*** | 0.946*** | 0.908*** | 0.864*** | 0.758*** | 0.885*** |

| (0.004) | (0.015) | (0.014) | (0.013) | (0.059) | (0.003) | |

| Credibility | 0.046** | 0.040* | 0.044** | 0.055*** | 0.014 | 0.069*** |

| (0.016) | (0.022) | (0.018) | (0.014) | (0.036) | (0.013) | |

| GDP | –0.027 | 0.178*** | –0.122** | –0.523** | 0.209** | –0.072* |

| (0.03) | (0.057) | (0.051) | (0.197) | (0.067) | (0.038) | |

| Credibility * USD | –0.103*** | |||||

| (0.013) | ||||||

| GDP * USD | 0.052*** | |||||

| (0.015) | ||||||

| Observations | 315 | 315 | 300 | 207 | 108 | 315 |

| No. of groups | 11 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 8 | 11 |

| R-squared | 0.994 | 0.995 | 0.971 | 0.998 | 0.994 | |

| Hausman Test (p-value) | 0.004 | |||||

Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***, **, * indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. All specifications include time fixed effects. Reserve shares are sourced from Eichengreen et al. (2016) for 1947–2013 and the Currency Composition of Official Foreign Exchange Reserves database for 2014–18. GDP data is sourced from the Maddison Project database for 1947–2016, with data for 2017 calculated using IMF data on GDP based on PPP. “Credibility” is the average appreciation of the reserve currency against the SDR in the previous five years. “GDP” is the share of world GDP, which the reserve currency issuer accounts for. “USD” is a dummy variable equal to one if the reserve currency is the US dollar and zero otherwise. “No of groups” refers to the number of reserve currencies included. PPP = purchasing power parity; SDR = special drawing rights.

Robustness Checks

We test for heterogeneity in coefficients for specific currencies and whether longer lags matter. In particular, we consider whether the effects of credibility and size vary for the US dollar (Table 1, column 6), which is the currency with the largest share of reserves throughout the sample period. Results suggest that credibility is not an important factor for the US dollar share of aggregate reserves. This may indicate that once a reserve currency is widely used, short-term episodes of depreciation are less important.

Alternatively, periods when the US dollar is appreciating may reflect flight to safety effects, rather than the underlying credibility of the United States as a reserve issuer. We also include longer lags of reserve shares and credibility and size measures, but these generally are not statistically significant and do not materially change the results.

The coefficient for the reserve currency issuer’s share of global GDP is only positive and significant in the random effects specification, suggesting that GDP shares could be a poor proxy for the global reach of reserve issuers and their importance in global trade and financial networks. Instead, direct measures of trade and financial reach are considered as alternative measures of global reach.

To measure the importance of a reserve currency issuer in global trade networks, the country’s share of world exports and a measure of its centrality in the global trade network are used (Porter et al. 2022).25 While the estimated coefficients are positive, they are not statistically significant (Table 2, column 3). Thus, we find weak evidence that prominence in global trade networks matters for reserve currency shares.

Table 2.

Alternative Measures of Global Reach: Trade and Financial Reach

|

1947–2018 (1) |

1950–2017 (2) |

1948–2018 (3) |

1980–2018 (4) |

1976–2018 (5) |

1977–2018 (6) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lagged Reserve Share | 0.888*** | 0.875*** | 0.885*** | 0.872*** | 0.840*** | 0.887*** |

| (0.004) | (0.005) | (0.005) | (0.029) | (0.017) | (0.016) | |

| Credibility | 0.046** | 0.008 | 0.038 | 0.035 | 0.03 | 0.060* |

| (0.016) | (0.038) | (0.031) | (0.023) | (0.025) | (0.024) | |

| GDP | -0.027 | -0.208* | -0.082 | -0.011 | -0.041 | 0.054 |

| (0.03) | (0.1) | (0.109) | (0.068) | (0.055) | (0.077) | |

| Export Share | 3.806 | |||||

| (3.461) | ||||||

| Export Centrality | 0.126 | |||||

| (0.255) | ||||||

| FX Turnover | -0.027 | |||||

| (0.035) | ||||||

| Debt Securities | 0.037*** | |||||

| (0.009) | ||||||

| Bank Claims | -0.054** | |||||

| (0.013) | ||||||

| Observations | 315 | 301 | 315 | 226 | 264 | 178 |

| No. of groups | 11 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 5 |

| R-squared | 0.994 | 0.993 | 0.994 | 0.997 | 0.995 | 0.997 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***, **, * indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. All specifications include currency and time fixed effects. For comparison, column 1 shows the baseline specification presented in Table 1. “Export share” is the share of the reserve currency issuer’s exports in world exports, using the Direction of Trade Statistics. “Export Centrality” is a measure of eigenvector centrality of the reserve currency issuer in the world trade network, calculated using the Direction of Trade Statistics. “FX Turnover” is the currency share of turnover in over-the-counter foreign exchange markets (BIS, Triennial Central Bank Survey). “Debt Securities” is the share of long-term external debt of low- and middle-income countries in a given currency share of the outstanding stock of long-term external debt for low and middle-income countries (World Bank, International Debt Statistics). “Bank claims” is the currency share of total cross-border bank claims excluding unallocated currencies (Bank for International Statistics, Locational Banking Statistics). “No of groups” refers to the number of reserve currencies included

The currency denomination of external debt in low- and middle-income countries matters for global reserves shares (Table 2, column 5). Other measures of financial development—the share of foreign exchange turnover in a given currency and the share of cross-border bank claims in a given currency— are not found to be significant drivers of reserve shares.26 A possible explanation: reserve currency issuers typically tend to be highly financially developed and their currencies have usually achieved international status, so incremental gains in this context may not be important for reserve currency shares.

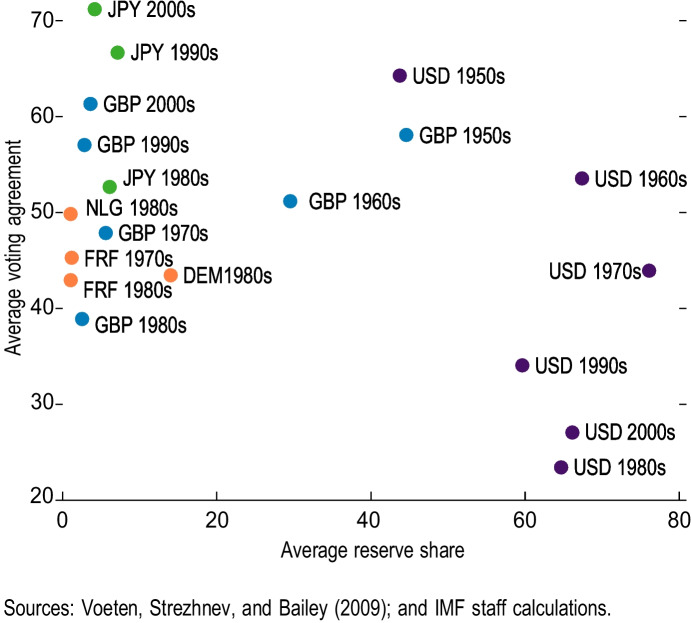

Eichengreen et al. (2019) suggest that reserve currency choices may be influenced by geopolitical interests, with countries choosing to hold reserves of issuers which have diplomatic or military power. Since military alliances display little variation during the sample period, four alternative measures of geopolitical influence are considered: GDP per capita relative to the average GDP per capita of reserve issuers; the proportion of countries that have voted in the same direction as the reserve issuer country at the UN General Assembly in a given year using the data set detailed in Voeten et al. (2009)27; spending on official development assistance (ODA) as a share of GDP using OECD data; and military spending as a share of total military spending by reserve issuers using Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) data. We find no evidence that geopolitical factors have driven aggregate reserve shares during the sample period, once other factors are con trolled for (Table 3)—the sign on the geopolitical variables is negative for three of the measures and is insignificant for all measures. For instance, the proportion of countries voting in line with the United States has fallen sharply while the dollar’s share of reserves has been resilient (Figure 6).28 Whether the measures used are poor proxies for geopolitical considerations, or whether political considerations are less relevant than they have been historically remain open questions.

Table 3.

Alternative Measures of Global Reach: Geopolitics

|

1947–2018 (1) |

1947–2017 (2) |

1947–2015 (3) |

1960–2018 (4) |

1949–2018 (5) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lagged Reserve Share | 0.888*** | 0.888*** | 0.880*** | 0.851*** | 0.865*** |

| (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.008) | (0.012) | (0.004) | |

| Credibility | 0.046** | 0.053** | 0.064*** | 0.065** | 0.047*** |

| (0.016) | (0.019) | (0.015) | (0.019) | (0.014) | |

| GDP | -0.027 | 0.175 | -0.166** | -0.040 | -0.066** |

| (0.030) | (0.163) | (0.070) | (0.065) | (0.022) | |

| GDP per capita | -0.040 | ||||

| (0.035) | |||||

| UN Votes | -0.001 | ||||

| (0.011) | |||||

| ODA | 0.791 | ||||

| (0.817) | |||||

| Military Spending | -0.085** | ||||

| (0.029) | |||||

| Observations | 315 | 307 | 248 | 233 | 291 |

| No. of groups | 11 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| R-squared | 0.994 | 0.993 | 0.992 | 0.994 | 0.99 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***, **, * indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. All specifications include currency and time fixed effects. For comparison, column 1 shows the baseline specification presented in Table 1. GDP per capita data is sourced from the Maddison Project dataset. “UN Votes” is the share of votes by all countries at the UN General Assembly which have been in agreement with the votes of the reserve currency issuing countries, where abstentions are counted as “no” votes (Voeten 2013). “ODA” is the amount of official development assistance provided by the reserve currency issuer country as a share of the currency issuer’s GDP (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). “Military Spending” is the military expenditure of the reserve currency issuer country as a share of total military spending by all reserve currency issuers (Stockholm International Peace Research Institute). “No of groups” refers to the number of reserve currencies included

Fig. 6.

UN Voting Agreement and Reserve Currency Shares

Drivers of Reserve Currencies using Disaggregate Data

Empirical Specification

In line with previous literature, the baseline specification focuses on reserve holders’ potential transactional demands (the intended uses of the reserves) and bilateral links to reserve issuers as drivers of reserve currency shares. More specifically, the trade share with the reserve currency issuer proxies for trade links, the currency denomination of public debt or cross-border bank claims captures financial considerations, while the de facto anchoring to a reserve currency captures exchange rate stability considerations for intervening in the foreign exchange market.29 We use a panel of 42 economies with data available for some or all years from 1999 to 2018 for reserve holdings in the main four reserve currencies (US dollar, euro, Japanese yen, and British pound),30 and model the reserve share of currency i in country c’s reserve portfolio in year t as:

where:

αc,i is a country-currency random/fixed effect

δt is a time fixed effect

Trade Sharec,i is the share of country c’s trade with reserve issuer i.

FX Alignmentc,i is country c’s estimated exchange rate comovement with the reserve currency i, following Ilzetzki et al. (2019)

Financial Linksc,i is either the share of country c’s public debt or cross-border bank claims denominated in reserve currency i.31

The baseline specification uses a model with country-currency and year fixed effects, as the Hausman test rejects the random effects model and the

Arellano-Bond estimator has limitations due to the small sample size. A Tobit model addressing the fractional nature of the dependent variable provides qualitatively similar results.32

Our model is estimated separately for AEs and EMDEs due to different drivers of reserve holdings and also different data availability across the two sets of countries. For example, debt considerations are much more relevant for EMDEs than for AEs, while the currency denomination of cross-border bank claims is available for AEs but not for EMDEs.33 We use the 2019 World Economic Outlook (WEO) classification to split the sample into EMDEs (32) and AEs (10, of which 6 are European). The findings do not change if instead the 2001 WEO or the contemporaneous WEO country classification is used.

Results

Results under baseline specification highlight the importance of inertia and financial considerations (Table 4):

Inertia: The findings suggest relatively large and significant inertia effects although of smaller magnitude than in aggregate data, with coefficients on the lagged reserve currency share in a range of 0.6–0.7 for EMDEs and 0.7–0.8 for AEs.

Financial considerations: The currency denomination of public debt (EMDEs) and cross-border bank claims (AEs) are also statistically significant, although economically less significant than inertia. A 10 percent increase in the share of a given currency denomination in public debt or bank claims is associated with about 1 percentage points increase in that currency’s reserve share.

Trade links and FX alignment: The measures of trade links and exchange rate comovement are not statistically significant determinants of reserve currency shares.

Table 4.

Econometric Specifications

| Fixed Effects | Random Effects | Arellano-Bond | Tobit | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMDE | AE | EMDE | AE | EMDE | AE | EMDE | AE | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| Lagged Reserve Share | 0.68*** | 0.79*** | 0.88*** | 0.97*** | 0.57*** | 0.70*** | 0.68*** | 0.80*** |

| (0.02) | (0.06) | (0.02) | (0.01) | (0.05) | (0.11) | (0.03) | (0.04) | |

| Trade Share | -0.08 | 0.09 | 0.05*** | -0.02 | -0.23 | 0.02 | -0.08 | 0.08 |

| (0.10) | (0.13) | (0.02) | (0.03) | (0.16) | (0.19) | (0.10) | (0.07) | |

| FX Alignment | -0.06*** | 0.06*** | 0.01 | -0.08 | 0.00 | -0.06** | -0.03 | |

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.06) | (0.00) | (0.03) | (0.03) | ||

| Debt Share | 0.10*** | 0.03** | 0.16*** | 0.10*** | ||||

| (0.04) | (0.02) | (0.06) | (0.03) | |||||

| Bank Claims Share | 0.08*** | 0.03** | 0.05* | 0.08 | ||||

| (0.03) | (0.01) | (0.03) | (0.05) | |||||

| Observations | 1,585 | 417 | 1,585 | 417 | 1,450 | 385 | 1,585 | 417 |

| Hausman Test (p-value) | 0.00 | 0.00 | ||||||

Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***, **, * indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. All specifications include time and country-currency fixed (random) effects. Reserve shares for four reserve currencies (US dollar, British pound, Japanese yen, and euro) are obtained from the central banks’ websites. “Trade Share” is the share of trade with the reserve issuer, obtained from the Direction of Trade Statistics. “FX Alignment” is a dummy variable equal to one if the exchange rate co-moves with the reserve currency, as estimated by Ilzetzki et al. (2019). “Debt Share” is the share of public debt denominated in a given reserve currency, obtained from the World Bank International Debt Statistics dataset. “Bank Claims Share” is the share of cross-border bank claims denominated in a given reserve currency obtained from the BIS international banking data by location. AE 5 advanced economies; EMDE 5 emerging market and developing economies

The importance of financial considerations has increased since the GFC (Table 5). Also, the currency denomination of public debt is a significant determinant of reserve holdings in EMDEs in all regions except Middle East and Central Asia, and economically significant in Africa and Asia-Pacific, while the currency denomination of cross-border bank claims is only statistically significant in AEs in Europe.

Table 5.

Alternative Region and Time Periods

| EMDE | AE | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999–2007 | 2008–2018 | Africa | Middle East | Asia and Pacific | Europe | Americas | 1999–2007 | 2008–2018 | Europe | Americas | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) | (11) | |

| Lagged Reserve Share | 0.47*** | 0.68*** | 0.60*** | 0.70*** | 0.69*** | 0.65*** | 0.64*** | 0.63*** | 0.69*** | 0.78*** | 0.83*** |

| (0.06) | (0.03) | (0.06) | (0.05) | (0.09) | (0.04) | (0.06) | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.08) | (0.08) | |

| Trade Share | –0.28 | –0.10 | 0.48** | –0.50*** | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.24*** | 0.21*** | –0.57** |

| (0.20) | (0.13) | (0.19) | (0.13) | (0.33) | (0.23) | (0.10) | (0.29) | (0.07) | (0.05) | (0.19) | |

| FX Alignment | –0.03*** | –0.08*** | |||||||||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | ||||||||||

| Debt Share | 0.13 | 0.15*** | 0.35*** | 0.08 | 0.28* | 0.03* | 0.10* | ||||

| (0.10) | (0.06) | (0.12) | (0.06) | (0.15) | (0.01) | (0.05) | |||||

| Bank Claims Share | –0.05 | 0.09*** | 0.07*** | –0.05 | |||||||

| (0.15) | (0.03) | (0.02) | (0.12) | ||||||||

| Observations | 369 | 1,216 | 379 | 334 | 152 | 436 | 284 | 124 | 293 | 316 | 85 |

| R-squared | 0.28 | 0.50 | 0.57 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.57 | 0.69 | 0.78 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***, **, * indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. All specifications include time and country-currency fixed effects. Reserve shares for four reserve currencies (US dollar, British pound, Japanese yen, and euro) are obtained from the central banks’ websites. “Trade Share” is the share of trade with the reserve issuer, obtained from the Direction of Trade Statistics

“FX Alignment” is a dummy variable equal to one if the exchange rate co-moves with the reserve currency, as estimated by Ilzetzki et al. (2019). “Debt Share” is the share of public debt denominated in a given reserve currency, obtained from the World Bank International Debt Statistics dataset. “Bank Claims Share” is the share of cross-border bank claims denominated in a given reserve currency obtained from the BIS international banking data by location. AE = advanced economies; EMDE = emerging market and developing economies

After the GFC, inertia effects appear to have become stronger for both EMDEs and AEs (Table 5, columns 1–2 and 8–9), with inertia effects for EMDEs converging with those for AEs in terms of magnitude. Inertia effects are largest among AEs in the Americas, and generally larger in AEs compared to EMDEs across all regions.

Trade links have become more important for AEs since the GFC (Table 5, column 9). This is particularly striking for European countries, although not surprising given their trade links with euro area economies.

Robustness Checks

Alternative measures of trade links and exchange rate comovement do not change the main results (Table 6). The coefficient on trade links becomes positive but continues to be statistically insignificant when the share of trade is replaced by the share of imports, to account for the fact that for some countries the reserves are held mainly to cover purchases of foreign goods and services. Similarly, when the trade shares are replaced with currency shares in imports invoicing, obtained from Boz et al. (2022), the coefficients continue to be imprecisely measured, possibly due to little variability in invoicing shares over time and hence collinearity with the fixed effects.

Table 6.

Alternative Measures: Imports and Invoicing Share, De Jure Peg, Total Level of Reserves

| Imports Share | Invoicing Share | EMDE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

EMDE (1) |

AE (2) |

EMDE (3) |

AE (4) |

Total reserves (5) |

De jure Peg (6) |

|

| Lagged Reserve Share | 0.68*** | 0.79*** | 0.68*** | 0.51*** | 0.68*** | 0.69*** |

| (0.02) | (0.06) | (0.03) | (0.08) | (0.02) | (0.02) | |

| Trade Share | 0.04 | 0.09 | –0.07 | –0.05 | 1.29** | –0.08 |

| (0.07) | (0.09) | (0.08) | (0.32) | (0.58) | (0.10) | |

| FX Alignment | –0.06*** | –0.07*** | –0.06*** | 0.00 | ||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | |||

| Debt Share | 0.10*** | 0.05* | 0.12*** | 0.11*** | ||

| (0.03) | (0.03) | (0.04) | (0.04) | |||

| Bank Claims Share | 0.08*** | 0.08 | ||||

| (0.03) | (0.05) | |||||

| Trade Share*Log Reserves | –0.06** | |||||

| (0.02) | ||||||

| Observations | 1,585 | 417 | 380 | 104 | 1,585 | 1,585 |

| R-squared | 0.52 | 0.69 | 0.57 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.52 |

Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***, **, * indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. All specifications include time and country-currency fixed effects. Reserve shares for four reserve currencies (US dollar, British pound, Japanese yen, and euro) are obtained from the central banks’ websites. “Trade Share” is the share of imports with the reserve issuer, obtained from the Direction of Trade Statistics., or share in imports invoicing, obtained from Boz et al. (2022). “FX Alignment” is a dummy variable equal to one if the exchange rate co-moves with the reserve currency, as estimated by Ilzetzki et al. (2019). In column (4), “FX Alignment” dummy is replaced with the de jure peg to a reserve currency from the IMF’s Annual Report on Exchange Arrangements and Exchange Restrictions database. “Debt Share” is the share of public debt denominated in a given reserve currency, obtained from the World Bank’s International Debt Statistics dataset. “Bank Claims Share” is the share of cross-border bank claims denominated in a given reserve currency obtained from the Bank for International Settlements international banking data by location. Data on the levels of total reserves come from IMF’s International Financial Statistics database. AE = advanced economies; EMDE = emerging market and developing economies

We also find that trade links are a significant determinant of reserve shares in EMDEs with lower level of total reserves (measured by the log

of total reserves from IMF IFS database), becoming less important as the level of reserves rises (Table 6, column 5).34 Finally, the coefficient on anchoring turns positive, as expected, but remains statistically insignificant when using the measure of the de jure peg to a reserve currency from the IMF AREAER database.35

Geopolitical measures deliver mixed results (Table 7). We consider three measures of geopolitical influence: the proportion of votes cast the same way as the reserve issuer at the UN General Assembly in a given year; the share of official development assistance (ODA) received from a given reserve issuer (for EMDEs only); and the share of imports of arms and ammunition (classified under Harmonized System Chapter 93) from a given reserve issuer. The results are mixed, and only the UN votes in AEs and the share of arms imports from reserve issuers in EMDEs are positively associated with the reserve currency share.

Table 7.

Alternative Geopolitical Measures

| UN Voting | ODA | Arms Imports | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMDE (1) | AE (2) | EMDE (3) | EMDE (4) | AE (5) | ||||||

| Lagged Reserve Share | 0.54*** | 0.74*** | 0.68*** | 0.67*** | 0.78*** | |||||

| (0.05) | (0.09) | (0.02) | (0.02) | (0.06) | ||||||

| Trade Share | -0.02 | 0.13 | -0.06 | -0.08 | 0.11 | |||||

| (0.11) | (0.09) | (0.10) | (0.09) | (0.13) | ||||||

| FX Alignment | -0.10*** | -0.06*** | -0.05*** | |||||||

| (0.01) | (0.01) | (0.01) | ||||||||

| Debt Share | 0.12*** | 0.11*** | 0.10*** | |||||||

| (0.04) | (0.03) | (0.03) | ||||||||

| Bank Claims Share | 0.06 | 0.08*** | ||||||||

| (0.05) | (0.03) | |||||||||

| UN Votes | 0.06 | 0.17*** | ||||||||

| (0.04) | (0.06) | |||||||||

| ODA Share | -0.03** | |||||||||

| (0.01) | ||||||||||

| Share in Arms Imports | 0.04*** | 0.02 | ||||||||

| (0.02) | (0.02) | |||||||||

| Observations | 1,102 | 288 | 1,585 | 1,585 | 417 | |||||

| R-squared | 0.35 | 0.62 | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.69 | |||||

Robust standard errors in parentheses. ***, **, * indicates significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. All specifications include time and country-currency fixed effects. Reserve shares for four reserve currencies (US dollar, British pound, Japanese yen, and euro) are obtained from the central banks’ websites. “Trade Share” is the share of trade with the reserve issuer, obtained from the Direction of Trade Statistics

“FX Alignment” is a dummy variable equal to one if the exchange rate co-moves with the reserve currency, as estimated by Ilzetzki et al. (2019). “Debt Share” is the share of public debt denominated in a given reserve currency, obtained from the World Bank’s International Debt Statistics dataset. “Bank Claims Share” is the share of cross-border bank claims denominated in a given reserve currency obtained from the Bank for International Settlement’s international banking data by location. “UN Votes” is the share of votes cast the same way as the reserve issuer at the UN General Assembly, with abstentions counted as “no” votes (Voeten 2013). “ODA Share” is the share of official development assistance received from the reserve issuer, sourced from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. “Share in Arms Imports” is the share of imports of arms and ammunition (classified under Harmonized System Chapter 93) from the reserve issuer, obtained from UN Comtrade. AE = advanced economies; EMDE = emerging market and developing economies; ODA = official development assistance

Summary on Drivers of Reserve Currencies

The econometric analysis of reserve currency shares reveals that (1) the drivers of reserve currency shares vary across AEs and EMDEs; (2) inertial effects are important throughout the entire period and increasingly important in recent decades; and (3) financial links are becoming more important, while trade links do not appear to be a robust driver of reserve currency shares.

Drivers of reserve configurations vary between AEs and EMDEs and over time. Financial links seem to be particularly relevant for EMDEs, while trade links appear more important for AEs, possibly reflecting the large concentration of non-euro area European countries in the AEs sample, with the bulk of their trade with eurozone countries and reserve holdings predominantly in euros.

On inertial effects, holding a large share of a given reserve currency in a given year appears to be a good predictor of reserve shares the following year, especially if the currency has been long in use as a reserve currency. Inertial effects are weaker in the disaggregated data, pointing to shifts in some countries’ reserve portfolios, but have become more important since the GFC, particularly in EMDEs. Inertial effects appear to dominate economic and geopolitical effects, such as the reserve issuers’ economic size and geopolitical influence,36 and the credibility of its currency. Credibility, in particular, seems to matter only up to a point—once a reserve currency becomes “dominant,” short-term episodes of depreciation are less important.

Contrary to previous studies, trade links/networks do not seem to be a robust driver of aggregate reserve shares. Reserve issuers’ centrality in global trade networks has some limited explanatory power. When using disaggregated data, we also find that trade links with reserve issuers generally fail to explain the observed reserve shares.37 It could be that a country’s trading partners are less relevant for reserve currency considerations in a world where export prices are set in a dominant currency, most likely the US dollar, rather than the producer’s currency (Gopinath et al. 2020). Unfortunately, the lack of comprehensive data on currencies used for trade invoicing does not allow for a further investigation of this link.

In contrast, financial links appear important and have become more significant over time. The currency denomination of external public debt and cross-border bank claims is an important driver of reserve shares, and increasingly so since the GFC. Moreover, the currency denomination of public debt is an especially important determinant of reserve holdings in EMDEs, particularly those in Africa and Asia. The currency denomination of debt also matters for aggregate reserve shares. But other measures of financial depth/reach of a currency, such as its share in foreign exchange turnover or cross-border bank claims do not matter. This may indicate threshold effects—deep financial markets are likely a precondition for reserve currencies, with incremental changes less relevant.

What Could Alter the Status Quo?

The findings in Sect. 4 and the empirical literature suggest that the currency composition of reserves is influenced by a range of slow-moving factors (historical ties, trade, and finance). This section offers a discussion of trends and uncertainties, including those related to the COVID-19 crisis, that could affect the status quo and lead to different currency configurations of reserve holdings with significant implications for the IMS.

Current Trends

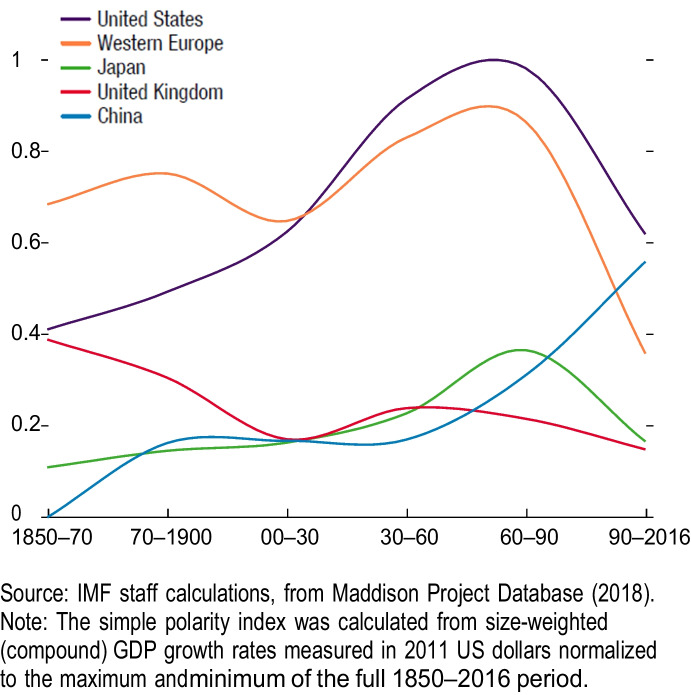

The sustained economic growth and rapid trade integration of EMDEs— particularly China—have led to less-concentrated global output and trade and gradually shifted the world’s economic center of gravity (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Historical Evolution of Simple Growth Polarity

Financial integration has also become more pronounced, with global capital flows, measured as the sum of gross capital inflows across all countries relative to the global GDP, three times as large in recent years than in 1970s. These trends have not (yet) affected the role of the US dollar as the dominant reserve and international currency. Further, the COVID-19 crisis has led to a global flight to safe assets, and to the dollar in particular, supported by the US Federal Reserve’s actions to provide liquidity.38

Going forward, China could overtake the United States as the world’s largest economy by 2030, while the share of EMDEs in global GDP is expected to exceed 50 percent by 2030. Despite this ongoing shift to a more multipolar global economy, the high degree of inertia in the currency composition of global reserves suggests that the US dollar will remain the dominant reserve currency for the foreseeable future.39

Uncertainties Going Forward

There are many uncertainties regarding current trends, including related to the COVID-19 crisis, that could have a lasting impact on trade and financial relationships, with implications for the currency composition of reserve holdings and the IMS.

Financial Considerations

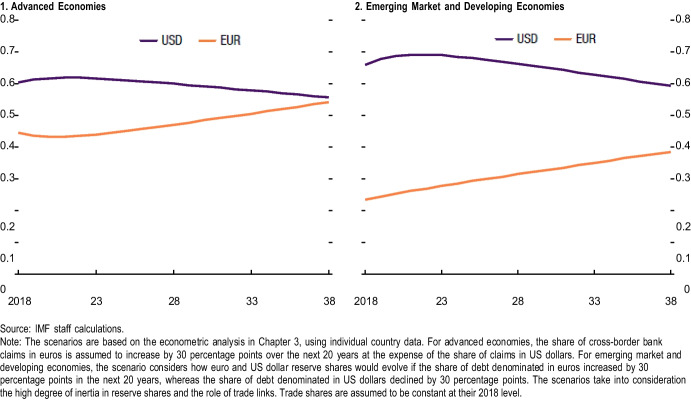

The empirical analysis in Section 4 highlights the growing importance of financial links and suggests that reserve issuers may be able to increase the prominence of their currencies as a reserve asset if they are able to materially expand their use in cross-border banking and debt markets.

Consider the following thought experiments. If the share of cross-border bank claims in euros were to increase by 30 percentage points over the next 20 years, the share of euro-denominated reserves of an average country in the sample would go up by about 5 percentage points, according to estimates from the country-level regression.40 Similar extrapolation suggests a greater impact of increased financial links for the reserve portfolios of EMDEs: if the share of euro-denominated public debt were to increase by 30 percentage points over the next 20 years at the expense of debt denominated in US dollars, the average share of the euro in EMDEs’ reserve portfolios could increase almost two-fold, from 23 percent to 40 percent (Figure 8).

Fig. 8.

Scenarios on the Impact of Financial Links on Reserve Currency Shares

The debt landscape, in which new creditors—including China—have become increasingly important (Horn et al. 2021), was evolving rapidly before the pandemic. Such shifts could accelerate in a post-pandemic world. Given the large scale of EMDEs’ financing needs, it is plausible that EMDEs’ renminbi-denominated debt could rise in future—consistent with a larger share of reserves held in renminbi.

Trade Links

The empirical analysis in Section 4 suggests that trade links have become less relevant as a driver of reserve currency configurations. Whether this trend persists depends on how trade patterns evolve in future.

The pandemic has highlighted the fragility of global supply chains and countries’ interest in ensuring the future security of critical supplies. Such factors could lead to more diversified supply chains and/or localized production to avoid overreliance on a single dominant supplier country in the future, with implications for the demand for reserves.41 This paper’s findings suggest that, post crisis, lower trade shares with reserve issuers could lead to lower reserve shares in some countries. However, this potential development in trade links could be countered by any reserve issuer’s ability to elevate the status of its currency as an invoicing currency.

Credibility

The existing literature and our empirical analysis find that credibility matters. The US dollar’s dominance has been related, in part, to a lack of credible alternatives. For instance, stalling use of the euro as a reserve currency has been linked to institutional gaps in the European monetary union—including a lack of risk sharing—exposed during the eurozone debt crisis (Maggiori et al. 2019). Iancu et al. (2020) find a roughly similar number of shifts away from the US dollar toward the euro as from the euro toward the US dollar prior to the GFC, but significantly larger number of shifts away from the euro since 2018. If the euro or other currencies were to overcome such impediments, they could provide more credible alternatives to the US dollar, and the currency composition of reserves could shift.42

Despite significant inertia observed in the past, the dominance of a single reserve currency might not be a sustainable equilibrium going forward. In the short term, swift actions by the US Federal Reserve during the COVID-19 crisis may have reinforced the credibility of the US dollar.43 But if the US economy continues to decline in size relative to the global economy, the demand for reserves might eventually outstrip the supply of US dollars, prompting the official sector to look for alternatives. Rising demand for reserve assets, particularly in the context of a global shortage of safe assets (Caballero et al. 2017), may create incentives for other potential suppliers to take proactive steps to develop new reserve currencies.

In light of the COVID-19 pandemic, the credibility of any reserve currency may depend on how the issuing country performs in bringing the pandemic under control and restarting its economy while managing the rising levels of debt. Failure to contain the spread of the virus and enact sound policies to avert a longer-lasting downturn and maintain the country’s economic health could lead to a depreciation of the issuer’s currency. This paper’s findings suggest that this would lead to a lower share in global reserves.

Exchange Rate Anchor

The number of countries with exchange rate pegs has declined in recent years, lowering the need to hold the reserve currency for foreign exchange intervention purposes. Reluctance to change fixed exchange rate arrangements, owing to fears of inducing instability, may have contributed to previously observed persistence, but such ties have loosened over time with an increasing use of alternative monetary frameworks (Figure 9).44 This could partly explain why the empirical analysis does not find a positive relationship between anchoring and reserve currency shares. It is also possible that the effect of exchange rate regimes and anchoring is poorly identified given the small sample size.

Fig. 9.

Monetary Policy Frameworks and Exchange Rate Anchors

Geopolitics as a Trigger of Currency Switches

Geopolitical or strategic considerations may trigger changes in reserve holdings beyond those driven by economic factors. For example, decisions to hold reserves in any currency may also be motivated by foreign policy considerations and security ties or military alliances.

Although it is difficult to pin down the geopolitical effects in the empirical analysis, we cannot rule them out, given the historical evidence. In fact, a recent example of a significant and sustained shift from one reserve currency to another point to a possible correlation with the introduction of sanctions (Iancu et al. 2020). More specifically, in the Spring of 2018, the Bank of Russia implemented a significant reallocation of its reserve portfolio away from the US dollar, mostly into renminbi, following the imposition of US sanctions.45

Going forward, spillovers from the COVID-19 pandemic and global supply chain disruptions, including as reflected in volatile oil prices, export bans on medical supplies and food, and less cooperation between countries, could result in strategic changes in reserve holdings of individual countries.

A deliberate push to internationalize currencies could also drive change. National policies have played a role in supporting the internationalization of currencies for economic as well as political benefits, including international prestige and the enhanced ability to project military power abroad. More recently, China has been actively promoting a wider use of the renminbi for trade and investment, which was supported by the addition of the renminbi to the SDR basket in 2016.46 Between 2010 and 2014, 37 central banks have reportedly added the renminbi to their reserve portfolios (Liao and McDow- ell 2016), with the share of renminbi in global reserves reaching 2 percent in 2019. The next stage in the internationalization of the renminbi could depend, to some extent, on the landscape of China’s economic and political ties that emerge after the COVID-19 crisis.

Technology as a Disruptor

The current configuration of reserve currencies could be altered by the rapid pace of financial innovation, underpinned by technology. Advances in financial and payments technologies can reduce switching costs and informational asymmetries, and thus further reduce the strength of existing network effects and inertia. Technology might also facilitate the circumvention of capital controls and sanctions, potentially facilitating the use of alternative currencies.47 In the short term, the two most potent channels are (1) the emergence of digital currencies and (2) changes in existing networks, including payment ecosystems.

Digital Currencies

Digital currencies can take on various forms and can be issued by both the public and private sectors. The implications of digital currencies for reserve holdings would depend on which kind of digital currency prevails.

Many central banks have considered or are considering issuing a central bank digital currency (CBDC). A recent BIS survey of central banks indicates that about 80 percent are engaging in work related to CBDCs, and 40 percent have progressed to experiments or proof of concept (Boar et al. 2020).48 Reserve implications of a CBDC issuance would depend on country and global circumstances. A CBDC issued by current issuers could increase the demand for reserves denominated in these currencies, whereas a CBDC issued by smaller countries with highly credible policy frameworks could make their currencies easier to use as reserves.49

Recently, the idea of a universal CBDC has also gained prominence. A syn- thetic hegemonic currency, backed by a basket of CBDCs, could provide more efficient domestic and cross-border payment services, benefiting from the credibility of multiple central banks that support it (Carney 2019). Such an architecture could change the demand for reserves denominated in currencies in the basket based on their relative weight.

Private digital currencies (PDCs) could also emerge as important international currencies.50 In 2019, Facebook announced plans to launch Libra, a single-currency private stablecoin with potentially global reach and the ambition to become the first example of a global stablecoin (GSC).51 The project later faltered, but the idea of a GSC has still traction. The launch of a GSC could increase the demand for fiat reserve currencies it is backed by. But GSCs do not need to be backed by existing fiat reserve currencies provided they gain credibility with users and investors, and could in principle attain reserve currency status on their own. It is also conceivable that more than one global stablecoin could become a reserve asset.

Digital currency competition may differ from traditional currency competition by differentiating along associated networks and users rather than being based on macroeconomic performance (Brunnermeier et al. 2019), hence possibly altering the traditional drivers of reserve currency con- figurations. But, while these “digital currency areas” may cut across borders in ways that existing currencies do not, variations in regulatory frameworks could lead to increased fragmentation of currency use.

Payment Systems

Most existing cross-border transfer and payment systems face challenges. They rely on correspondent banking relationships, which can be complex, slow, expensive, and nontransparent (Iancu et al. 2020). Alternative systems, using technologies such as distributed ledgers, could overcome existing constraints and inefficiencies. New payment systems (and some existing ones) may offer the opportunity to settle in multiple currencies, reducing the need for vehicle and invoicing currencies going forward and moving the IMS toward decentralization.52 Other new systems may be centered around one established international currency and boost its position among regional or global reserve currencies.

Digital platforms could offer alternative networks for emerging (fiat or digital) currencies to tap into. For instance, as discussed above, some digital assets might gain rapid traction if they are able to tap into large pre-existing networks or attract users with bundled services. Both features could be accomplished by Big Tech companies with operations transcending national borders.

Longer-Term Considerations

With accelerating digitalization and technological innovations, the impact of technology on international reserves and global configurations could become more prominent over time. In addition to creating new classes of assets, reshaping the financial industry, and transforming reserve management— trends that are already underway—technology can affect reserve holdings by transforming the traditional drivers of reserve configurations (such as network effects, trade and financial linkages, geopolitics, and institutions and the legal system) and their impact on reserves.

Future reserve currency configurations will be shaped by many factors which are explored using a well-established scenario planning approach in Iancu et al. (2020).53 Scenarios are narratives that illustrate how an unpredictable future might play out; they are not forecasts or predictions but help generate perspectives sufficiently different from those currently held. The scenarios outlined in Iancu et al. (2020) illustrate how technology can either strengthen the role of a dominant currency or facilitate a shift toward a multipolar world. They also highlight the importance of other factors, such as the credibility, scale, and stability of traditional and nontraditional reserve assets, as well as emerging considerations, such as climate change risks. The scenarios particularly underscore the importance of credibility and trust, which generally benefit currencies of countries offering geopolitical neutrality and/or strong institutions. However, it may no longer be unthinkable to see currencies issued by a more socially responsible and accountable private sector to replace those from the public domain, or to simply see a trend toward greater decentralization of economic power as well as reserve currencies.

Reserve configurations may also be less stable in the future, particularly due to the prominence of cyber risks. The scenarios highlight risks ranging from cyberattacks to network and technology vulnerabilities to “shortage” of personal data.54 And, while risk insurance and regulation may take a different shape in the future, they would still be needed in an interconnected world.

Conclusion

This paper investigates the drivers of the currency composition of international reserves using both COFER data of aggregate reserve shares and a newly compiled panel data set of individual countries’ reserve holdings by currency. Findings suggest that inertia in reserve currency shares remains important and in fact has grown in significance since the GFC. With continued financial globalization, financial links have also become a more significant driver over time, while the significance of trade links has waned. We also find that drivers of reserve currency shares vary between AEs and EMDEs, with financial links appearing to be particularly relevant for EMDEs.

This paper’s empirical evidence suggests that, extrapolating recent trends, the US dollar’s dominance as a reserve currency is expected to endure. However, several significant shocks have happened recently that could alter this equilibrium. The COVID-19 pandemic and global supply chain disruptions raise significant uncertainties concerning key trends in economic drivers of reserve configurations going forward. The buildup in geopolitical tensions could trigger sudden strategic adjustments in reserve holdings. Furthermore, technological advances, particularly the emergence of digital currencies and advances in payment systems, could alter the importance of traditional drivers of reserve currencies, speed up the transition to alternative reserve configurations, result in the emergence of new reserve currencies, and even lessen the stability of future reserve currency configurations.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on an IMF Departmental Paper which was completed under the overall guidance of Ana Corbacho and Kristina Kostial. We thank Martin Mühleisen and Louis Marc Ducharme for their generous sponsorship and support and Carlos Sánchez-Muñoz and Marcelo Dinenzon for their support and collaboration in a companion project that helped improve the empirical analysis. We are also grateful for useful comments received from two anonymous referees. Remaining errors are our responsibility. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF Management.

Annex

Table 8.

List of Economies

| Country | Years | Country Group | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azerbaijan | 1999–2018 | EMDE | Central Bank of Azerbaijan |

| Bangladesh | 2005–18 | EMDE | Bangladesh Bank |

| Bolivia | 2008–18 | EMDE | Central Bank of Bolivia |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2001–18 | EMDE | Central Bank of Bosnia and Herzegovina |

| Brazil | 2002–18 | EMDE | Central Bank of Brazil |

| Bulgaria | 2000–18 | EMDE | Bulgarian National Bank |

| Canada | 1999–2018 | AE | Bank of Canada and Department of Finance Canada |

| Colombia | 2007–18 | EMDE | Bank of the Republic |

| Costa Rica | 2011–18 | EMDE | Central Bank of Costa Rica |

| Denmark | 1999–2018 | AE | Danmarks Nationalbank |

| Finland | 2001–18 | AE | Bank of Finland |

| Georgia | 1999–2018 | EMDE | National Bank of Georgia |

| Germany | 2000–18 | AE | Deutsche Bundesbank |

| Ghana | 2003–18 | EMDE | Bank of Ghana |

| Hong Kong SAR | 1999–2018 | AE | Hong Kong Monetary Authority |

| Kazakhstan | 1999–2018 | EMDE | National Bank of Kazakhstan |

| Kenya | 2001–18 | EMDE | Central Bank of Kenya |

| Korea | 2007–18 | AE | Bank of Korea |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 2003–18 | EMDE | National Bank of the Kyrgyz Republic |

| Malawi | 2008–18 | EMDE | Reserve Bank of Malawi |

| Moldova | 2011–18 | EMDE | National Bank of Moldova |

| Nigeria | 2011–15 | EMDE | Central Bank of Nigeria |

| North Macedonia | 2001–18 | EMDE | National Bank of the Republic of North Macedonia |

| Norway | 1999–2018 | AE | Norges Bank |

| Papua New Guinea | 2005–18 | EMDE | Bank of Papua New Guinea |

| Paraguay | 2002–18 | EMDE | Central Bank of Paraguay |

| Peru | 2000–18 | EMDE | Central Reserve Bank of Peru |

| Philippines | 2005–18 | EMDE | Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas |

| Romania | 2001–18 | EMDE | National Bank of Romania |

| Russia | 2007–18 | EMDE | Bank of Russia |

| Serbia | 2005–18 | EMDE | National Bank of Serbia |

| South Africa | 2005–18 | EMDE | South African Reserve Bank |

| Sweden | 2006–18 | AE | Sveriges Riksbank |

| Switzerland | 1999–2018 | AE | Swiss National Bank |

| Tajikistan | 2008–18 | EMDE | National Bank of Tajikistan |

| Tanzania | 2003–18 | EMDE | Bank of Tanzania |

| Tunisia | 2009–18 | EMDE | Central Bank of Tunisia |

| Turkey | 2004–18 | EMDE | Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey |

| Uganda | 2006–18 | EMDE | Bank of Uganda |

| Ukraine | 2001–18 | EMDE | National Bank of Ukraine |

| United States | 1999–2018 | AE | Federal Reserve |

| Zambia | 2004–18 | EMDE | Bank of Zambia |

| Source: Authors’ compilations |

Footnotes

In this paper, the terms “country” and “economy” do not in all cases refer to a territorial entity that is a state as understood by international law and practice. These terms cover some territorial entities that are not states but for which statistical data are maintained on a separate and independent basis.

IMF Balance of Payments and International Investment Position Manual, sixth edition (BPM6).

“Reserve currencies” for the purpose of this paper are the currencies separately identified and reported in the IMF COFER database: eight currencies currently in use (the SDR currencies—US dollar, euro, Japanese yen, British pound, and Chinese renminbi, plus the Swiss franc, Canadian dollar, and Australian dollar—comprising 97 percent of total allocated reserves), and three currencies preceding and later replaced by the euro (the Deutsche mark, French franc, and Dutch guilder).

The Triffin dilemma refers to the fundamental tension between the heightened global demand for reserve currencies and the domestic policy incentives of reserve issuers, with implications for global financial stability. As such, the outsized role of the US dollar as a reserve currency was seen to impart instability in the system.

A 2012 IMF survey of reserve managers showed that many central banks were contemplating shifts to currencies such as the Australian and Canadian dollars (Morahan and Mulder 2013).

For instance, Ito et al. (2019) show that the share of renminbi invoicing in Japanese exports to China increased from 1.3 percent in 2009 to 12.3 percent in 2017.

Network effects could promote the use of a new reserve currency (by reducing the switching costs) once it reaches a critical mass or create a lock-in effect for an incumbent currency used widely because of high switching costs.

For example, the Federal Reserve system acted as a market maker for the US dollar. On the other hand, cap- ital controls were used to limit access to the Deutsche mark in the 1960s and 1970s to better control inflation and allay exporters’ fears of loss of international competitiveness, while the internationalization of the Japanese yen also occurred despite initial domestic political resistance—the Foreign Exchange Law of 1980 allowed capital controls.

Chiţu et al. (2012) and Eichengreen and Flandreau (2010) also provide evidence that the development of US financial markets supported the increased role of the US dollar in trade finance and international debt markets.

Historical (political and economic) ties continued to support the sterling area and the international role of the British pound despite the declining role of the United Kingdom in the global economy. More specifically, after the United Kingdom left the gold standard in 1931, it encouraged key trading partners and colonies to peg their currencies against the pound to facilitate trade. Following World War II, the sterling area was formalized into a legally defined group with pegged exchange rates to sterling, common exchange controls against the rest of the world, and the maintenance of national reserves in sterling. Despite episodes of sterling devaluation, in 1970 the sterling area still comprised the United Kingdom and 35 other countries together with all British dominions, protectorates, protected states, and trust territories except Canada and Zimbabwe. The sterling area effectively dissolved with the demise of the Bretton Woods system in 1972. Vicquery (2022) provided a measure of relative global dominance of key currencies covering a longer timespan compared to Ilzetzki et al. (2019).

Survey data also confirm that for EMDEs, the currency composition of reserves is driven by the currency composition of external liabilities, the composition of trade, and currency pegs (Morahan and Mulder 2013). For AEs, depth and liquidity of markets are the dominant considerations.

More recently, Laser and Jan (2020) confirm the earlier findings, using the same methodology as Eichengreen and Donald (2000) but employing country-specific data on currency composition of reserves disclosed by various central banks. The methodology used in these papers is not robust to various specifications and does not account for the inertial effects.

Gopinath (2015) highlights that, in a sample of 43 economies, the dollar’s share for imported goods invoicing is about 4.7 times the share of US goods in imports.

The choice of the invoicing currency itself is influenced by the size and centrality of countries in global trade networks reflecting natural advantages, and the coalescence of exporters to limit competitive disadvantages (Bacchetta and van Wincoop 2005; Goldberg and Tille 2013). Mukhin (2022) and Chung (2016) discuss the role of integration in global value chains for trade invoicing currency choice.

Ito and McCauley (2020) also use data published by 58 central banks in the 1999–2018 period, but, unlike this paper, do not include the US or the euro area economies. Their dataset was expanded by Chinn et al. (2022) to 74 economies over 1999–2020. Aizenman et al. (2020) assembled data for 58 countries from reports to the IMF on reserves in the form of nontraditional currencies. Arslanalp et al. (2022) used more detailed data disclosed by 80 economies utilizing the dataset compiled by Ito and McCauley (2020) as updated by Chinn et al. (2022), the IMF's Data Template and central bank annual reports.

Data from Eichengreen et al. (2016) are originally sourced from IMF Annual Reports and Horsefield (1969).

The remaining 6 percent of global reserves are the unallocated reserves for which the currency breakdown is not available.

The reported shares of the US dollar and British pound cover the entire period of analysis (1947–2018). Other currencies cover shorter periods consistent with their status of “reserve currencies,” including the French franc and Deutsche mark since 1970 and Dutch guilder since 1973 (all three were replaced by the euro in 1999), Swiss franc and Japanese yen since 1973, Australian dollar and Canadian dollar since 2012, and Chinese renminbi since 2016.

The list of countries, year coverage, and sources are provided in Annex Table 8. The sample consists of 15 countries in Europe, 8 in the Americas, 8 in Africa, 5 in Asia, and 6 in the Middle East and Central Asia. The panel is unbalanced; for example, only 8 countries report data for the full period and 3 for less than 10 years. In addition, the number of currencies reported varies by country, with some countries reporting separately only a few currencies. Limiting the sample to US dollar and euro shares, the two currencies consistently reported by most countries in the sample, yields qualitatively similar results.

Six out of 10 AEs in the sample are in Europe, whereas the comparable figure for EMDEs is 9 out of 32.

The analysis presented here uses reserve shares unadjusted for valuation effects; however, the results are robust to using the valuation adjusted shares of Eichengreen et al. (2016).

In contrast, Eichengreen et al. (2016) rely on a random effects model.

The main findings are robust to using, as a dependent variable, the share of synthetic euro reserves, which aggregates the shares of pre-1999 legacy currencies (Deutsche mark, French franc, Dutch guilder).

The high R-squared in all tables using aggregate reserve shares is due to the latter being a very slow-moving variable, which provides yet another reason to examine the reserve shares at country level.

We use a measure of the “eigenvector centrality” of the reserve issuer in the global trade network.

In using measures of financial development, the time horizon of the sample is substantially reduced due to their limited availability. Findings are robust to controlling for the GDP share alongside measures of financial development.

For more information on the UN voting data set, see Voeten (2013).

A similar pattern emerges when average reserve shares are plotted against official development assistance; the US ODA as a share of GDP has fallen since the 1960s.

Time-series data for trade by invoicing currency are not available for many countries.

Other reserve currency shares, including renminbi shares, are not included due to the lack of data on cross-border bank claims and external public debt denominated in those currencies.

The currency denomination of public debt and cross-border bank claims are obtained from the World Bank International Debt Statistics dataset and the BIS international banking data by location, respectively.

In contrast from previous studies that use disaggregated data, we include the lagged reserve share as a regressor, which makes the panel dynamic and introduces dynamic panel bias, that is, strict exogeneity of the regressors no longer holds. The fixed effects model is no longer consistent when the number of country-currency pairs tends to infinity and T is fixed, while the interpretation of the random effects model depends on the assumption of initial values of a dynamic process. The Arellano-Bond estimator overcomes these issues but is designed for “small T large N” panels, which might not be applicable in this case given relatively small N. Also, all these models ignore the fractional nature of the dependent variable, that is, predicted values should always lie in the unit interval. A Tobit model addresses this issue but might suffer from the incidental parameters problem in the presence of fixed effects.

An alternative measure capturing the financial links is the currency breakdown of external debt liabilities constructed by Bénétrix et al. (2019). However, using this measure will further limit the sample (to 23 countries).

We do not find similar effect for financial links.