Abstract

Cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 and Pasteurella multocida toxin induced dose- and time-dependent increases in focal adhesion kinase (FAK) Tyr397 phosphorylation in Swiss 3T3 cells. FAK autophosphorylation was sensitive to inhibitors of p160/ROCK and coincided with the formation of stable complexes between FAK and Src family members.

Bacterial toxins that modify proteins involved in cell signaling cascades have dramatic effects on target cells. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 (CNF1) is produced by some Escherichia coli isolates that can cause extraintestinal infections in humans (4). The principal biological effects of this toxin are the formation of giant, multinucleated cells in tissue culture and a strong necrotic reaction following intradermal injection (5, 8). CNF1 directly activates members of the Rho family of small GTPases: RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42 (10, 24, 25, 42, 43). CNF1 deamidates a glutamine residue near the active site of the Rho proteins, thereby blocking the hydrolysis of GTP to GDP and constitutively activating the GTPases (11, 25, 43). More recently, the transglutamination of Rho Gln63 by CNF1 through the addition of ethylenediamine, putrescine, or dansyl cadavarine has been described and also linked to constitutive activation (42).

Pasteurella multocida toxin (PMT) causes the turbinate bone atrophy associated with porcine atrophic rhinitis. PMT is an extremely potent mitogen for Swiss 3T3 cells, other fibroblast cell lines, and early-passage cultures and promotes anchorage-independent growth of Rat-1 cells (16, 40). Although the precise biochemical activity and target of PMT are still unknown, several lines of evidence indicate that PMT enters cells and acts intracellularly to initiate signaling and sustain DNA synthesis (40, 47). PMT is known to activate the alpha subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein Gq (29, 44, 53), to induce inositol phosphate signaling, protein kinase C activation, intracellular calcium mobilization, and extracellularly stimulated receptor kinase cascade activation (23, 46).

CNF1 and PMT share the ability to induce Rho-dependent actin stress fiber formation, focal adhesion assembly, and tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) in Swiss 3T3 cells (22, 23). The serine/threonine protein kinases of the Rho-associated coiled-coil-forming protein kinase (p160/ROCK) family have been identified as downstream targets of Rho-GTP (1, 26, 50) that transduce Rho activation into stress fiber formation and focal adhesion assembly (2, 21). PMT has been shown to induce a Rho-dependent increase in endothelial cell permeability mediated by p160/ROCK phosphorylation and inactivation of myosin light-chain phosphatase (9). Phosphorylation of FAK and stress fiber formation also occur in response to a large number of stimuli, including bioactive lipids such as lysophosphatidic acid, polypeptide growth factors such as platelet-derived growth factor and insulin growth factor, neuropeptides such as bombesin (36, 38), integrin engagement, and activated variants of Src (31). These observations indicate that FAK is a point of convergence in a variety of signal transduction pathways (3, 37, 55).

Tyrosine phosphorylation plays a critical role in promoting the recruitment of active signaling molecules into multiprotein signaling networks (32). The major site of FAK autophosphorylation, Tyr397, is potentially a high-affinity binding site for the SH2 domain of Src family proteins (collectively referred to as Src). Phosphorylation of this site can facilitate the formation of an FAK-Src signaling complex in which both kinases are active (14, 31, 35).

In this study, we investigated FAK Tyr397 phosphorylation in quiescent Swiss 3T3 cells treated with CNF1 or PMT. Swiss 3T3 cells were plated in 100-mm-diameter dishes or eight-well chamber slides with Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum and were used when the cells were confluent and quiescent (39). Lysates from E. coli XL1 Blue harboring plasmid pISS392 (expressing CNF1) and E. coli XL1 Blue harboring the plasmid pBluescript SK(−) were prepared (23). Recombinant PMT and inactive, mutant (C1165S) PMT were expressed and purified (51).

The stimulation of FAK phosphorylation at Tyr397 by PMT or CNF1 was investigated, as described previously (41), by exposing quiescent Swiss 3T3 cells to each of the toxins at different concentrations for 4 h. After treatment, the cells were solubilized and FAK was immunoprecipitated from the cleared lysate by using polyclonal rabbit anti-FAK antibody C-20 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane, and probed with a specific rabbit anti-FAKpTyr397 antibody (Biosource). Bound antibody was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence, using donkey anti-immunoglobulin G rabbit antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham Pharmacia). Stripping the membrane of antibody and reprobing with anti-FAK antibody C-20 confirmed that equal amounts of FAK were recovered after immunoprecipitation.

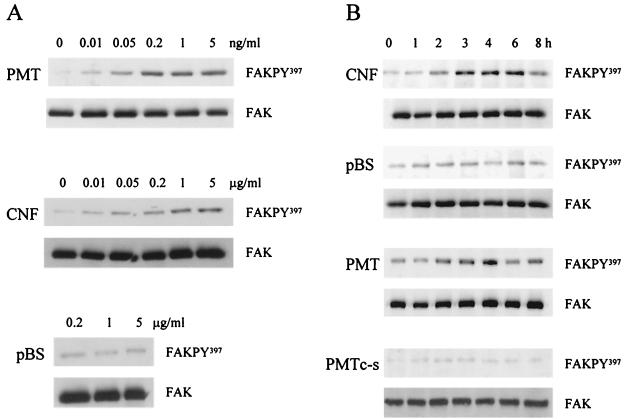

Treatment with PMT induced a striking dose-dependent increase in the phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr397 (Fig. 1A). PMT elicited a detectable increase in FAK Tyr397 phosphorylation at concentrations as low as 10 pg ml−1, and a maximal effect was achieved at 1 ng ml−1. Treatment with bacterial lysates containing CNF1 also induced phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr397 in a dose-dependent manner, with an effect being detectable at 200 ng ml−1 of bacterial lysate (Fig. 1A). A control E. coli lysate harboring pBluescript stimulated a low level of phosphorylation only at concentrations above 1 μg ml−1. For subsequent experiments, the lysates were diluted in DMEM to a protein concentration of 0.5 μg ml−1.

FIG. 1.

Dose- and time-dependent induction of tyrosine 397 autophosphorylation of FAK by CNF1 and PMT. (A) Quiescent Swiss 3T3 cells were treated with purified PMT over a concentration range of 0.01 to 5 ng ml−1, with lysates from recombinant E. coli expressing CNF1 over a concentration range of 0.01 to 5 μg ml−1, or with lysates from E. coli harboring pBluescript (pBS) for 4 h. The cellular FAK was immunoprecipitated, and the isolated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. A Western blot of the gel was probed with a polyclonal antiserum specific for the Tyr397 autophosphorylation site (FAKPY397). The antibodies were stripped from the membranes and probed with the anti-FAK antibody (FAK). (B) Quiescent Swiss 3T3 cells were treated with lysates from E. coli expressing CNF1 or harboring control pBluescript plasmid at a final concentration of 0.5 μg ml−1 or with PMT or the C1165S mutant PMT (PMTc-s) at a final concentration of 5 ng ml−1. Cells were harvested before the toxin preparations were added and at 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, and 8 h after addition of the toxins. The cellular FAK was immunoprecipitated, and the isolated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. A Western blot of the gel was probed with a polyclonal antiserum specific for the Tyr397 autophosphorylation site. The antibodies were stripped from the membranes and probed with the anti-FAK antibody.

The induction of FAK Tyr397 phosphorylation following CNF1 or PMT treatment was also examined as a function of time (Fig. 1B). Quiescent cultures of Swiss 3T3 cells were exposed to PMT, the nonmitogenic C1165S PMT mutant (51), or CNF1 for up to 8 h and then analyzed for FAK Tyr397 phosphorylation as described above. There was a lag period of 1 to 2 h between toxin addition and a detectable increase in the phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr397 (Fig. 1B). This lag period did not reflect a requirement for de novo FAK protein synthesis, since we verified that similar amounts of FAK protein were recovered after different lengths of treatment with PMT, C1165S PMT, or CNF1 (Fig. 1B). The delay was probably due to the period required for the toxins to bind to the cell surface, become internalized, and perhaps be processed to an active form. The enhanced phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr397 induced by these toxins was maximal at 4 h and persisted for at least 8 h, presumably because the toxins constitutively activate targets upstream of FAK. In contrast, FAK autophosphorylation induced by bombesin is a rapid consequence of receptor stimulation, reaching a peak 10 to 15 min after treatment, with the level of FAK Tyr397 phosphorylation returning to almost baseline levels after 30 min (data not shown). The biologically inactive C1165S PMT did not induce a significant increase in FAK autophosphorylation at any time point examined.

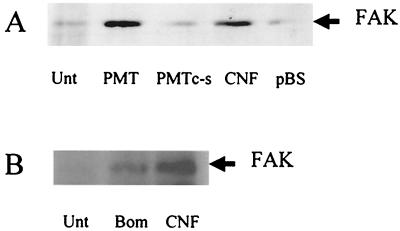

The phosphorylation of FAK Tyr397 in response to bombesin and other agonists facilitates the formation of a stable FAK-Src signaling complex (41). The formation of such a complex in cells treated with PMT or CNF1 for 4 h was investigated as described previously (41). The cells were solubilized in ice-cold lysis buffer, and the cleared lysates were then immunoprecipitated with protein A-agarose linked to polyclonal antibody SRC-2 (Santa Cruz), which recognizes the C-terminal sequence (residues 509 to 533) of Src, Yes, and Fyn (the Src family members expressed in fibroblasts). The immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE prior to Western blotting with anti-FAK polyclonal antibody (C-20). Both PMT and CNF1 induced the formation of a complex between FAK and Src which could be immunoprecipitated with the anti-Src family antibody (Fig. 2A). Formation of such a complex was not induced in cells treated with C1165S PMT or the control E. coli lysate. In agreement with recent results (41), Western blotting of Src immunoprecipitates with anti-FAK revealed an association of endogenous FAK with Src in cells stimulated with bombesin for 10 min (Fig. 2B). An even larger amount of FAK became complexed with Src following treatment with CNF1 over a 4-h period than with bombesin after 10 min. Consequently, the signaling events initiated by the toxin-induced FAK-Src complexes are of greater intensity and longer duration than signals from complexes formed in response to a transient stimulation of a receptor by its agonist.

FIG. 2.

Induction of FAK-Src association by CNF1 and PMT. (A) Quiescent Swiss 3T3 cells were either left untreated (Unt) or were treated with PMT or the C1165S mutant (PMTc-s) at a final concentration of 5 ng ml−1 or with lysates from E. coli expressing CNF1 or harboring the control pBluescript plasmid (pBS) at a final concentration of 1 μg ml−1. Cells were harvested after 4 h. The cellular Src was immunoprecipitated, and the isolated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. A Western blot of the gel was probed with a polyclonal anti-FAK antibody (FAK) to detect FAK that had coimmunoprecipitated with Src. (B) Quiescent Swiss 3T3 cells were treated with bombesin at a final concentration of 10 nM or with lysates from E. coli expressing CNF1 at a final concentration of 1 μg ml−1 for 15 min or 4 h, respectively, or were left untreated for 4 h. FAK coimmunoprecipitating with Src was detected as described above for panel A.

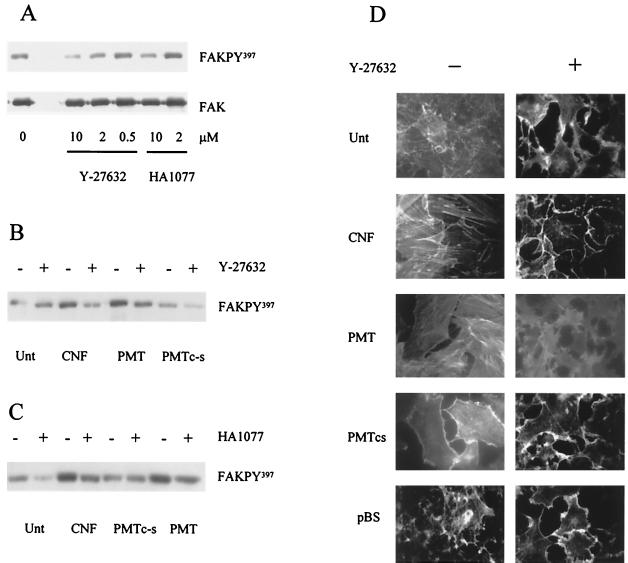

We investigated whether p160/ROCK activation was required for PMT and CNF1 to induce autophosphorylation of FAK. Quiescent cultures of Swiss 3T3 cells were treated with two inhibitors of p160/ROCK, HA1077 (Calbiochem) and Y-27632 (Welfide), individually. HA1077 inhibits a number of serine/threonine protein kinases, including p160/ROCK (30). Y-27632 is a specific inhibitor of p160/ROCK that blocks Rho-induced reorganization of the cytoskeleton (27). After 1 h, the cells were stimulated with toxin for a further 4 h. The two inhibitors attenuated the increase in the phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr397 induced by either CNF1 or PMT (Fig. 3A to C). Thus, the increase in the autophosphorylation of FAK induced by either CNF1 or PMT is mediated by protein kinases of the p160/ROCK family.

FIG. 3.

Effect of p160/ROCK inhibitors on CNF1- and PMT-induced FAK autophosphorylation and actin stress fiber formation. (A) Quiescent Swiss 3T3 cells were incubated in DMEM with p160/ROCK inhibitors HA1077 (2.0 and 10 μM) and Y-27632 (0.5, 2.0, and 10 μM) for 1 h prior to the addition of a lysate from E. coli expressing CNF1 at a final concentration of 0.5 μg ml−1. Cells were harvested after 4 h. The cellular FAK was immunoprecipitated, and the isolated proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE. A Western blot of the gel was probed with a polyclonal antiserum specific for the Tyr397 autophosphorylation site (FAKPY397). The antibodies were stripped from the membranes and reprobed with the anti-FAK antibody (FAK). Cells were similarly pretreated (+) or not pretreated (−) for 4 h with Y-27632 (B) or HA1077 (C) at a final concentration of 10 μM prior to the addition of wild-type PMT or mutant C1165S PMT (PMTc-s) at a final concentration of 5 ng ml−1. The basal level of Tyr397 phosphorylation was determined from cells not treated with toxin (Unt). (D) Quiescent Swiss 3T3 cells were incubated in DMEM with (+) or without (−) p160/ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (10 μM) for 1 h prior to the addition of lysate from E. coli harboring control pBluescript plasmid or expressing CNF1 at a final concentration of 0.5 μg ml−1 or wild-type or mutant PMT at a final concentration of 5 ng ml−1 or not treated with a toxin. After 16 h, the cells were fixed in paraformaldehyde (3.7%), permeabilized, and stained with phalloidin-rhodamine to demonstrate actin organization. The cells were examined by fluorescence microscopy.

CNF1 and PMT both induced the formation of parallel arrays of actin stress fibers in quiescent Swiss 3T3 fibroblasts within 4 h of toxin treatment (22, 23), and these stress fibers persisted for at least 18 h (Fig. 3D). Quiescent Swiss 3T3 cells were incubated in medium containing 10 μM Y-27632 for 1 h and then treated for 16 h with CNF1 lysate, purified PMT, or purified mutant C1165S PMT, which is known to have lost the ability to induce actin stress fiber formation (51). The polymerization state of the actin cytoskeleton was analyzed by using phalloidin conjugated to rhodamine (22). The results showed for the first time that exposure of the cells to the p160/ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 strongly inhibited the formation of actin stress fibers in response to either CNF1 or PMT (Fig. 3D). Thus, PMT and CNF1 both activate signaling pathways that converge at p160/ROCK, thereby stimulating the formation of actin stress fibers and leading to the autophosphorylation of FAK in Swiss 3T3 cells.

Like other toxins that act intracellularly, PMT and CNF1 have highly specific molecular targets that are modified to affect the physiology of those cells. Although the two toxins have different primary targets and induce different cellular outcomes, they both stimulate the Rho family of small GTPases, particularly RhoA. PMT and CNF1 have previously been shown to induce tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion proteins, including FAK, via a Rho-dependent pathway that leads to the formation of actin stress fibers and to the assembly of focal adhesions (22, 23). Considerable evidence indicates that translocation of FAK to nascent focal adhesions promotes its autophosphorylation as a result of clustering and/or conformational changes (38). Because the major site of FAK autophosphorylation, Tyr397, is potentially a high-affinity binding site for the SH2 domain of Src, the phosphorylation of this site facilitates the formation of an FAK-Src signaling complex (41). FAK and Src are thought to promote tyrosine phosphorylation of downstream targets, including the adapter proteins paxillin and Cas (6, 15, 33, 48, 49). The importance of FAK-mediated signal transduction is underscored by recent experiments showing that this tyrosine kinase is involved in embryonic development (18), the control of cell migration (7, 13, 19), cell proliferation (13, 45), and apoptosis (12, 17, 54).

Activated RhoA interacts with a number of targets that mediate intracellular signaling, including p160/ROCK (1, 20), protein kinase N (52), rhotekin, and rhophilin (34). We found that two structurally unrelated inhibitors of p160/ROCK activity attenuated the autophosphorylation of FAK and the formation of actin stress fibers induced by PMT or CNF1. Thus, the formation of stress fibers and the phosphorylation of FAK at Tyr397 in Swiss 3T3 cells treated with PMT or CNF1 are dependent on a pathway involving p160/ROCK. GDP-bound RhoA, which has been modified by Bordetella dermonecrotic toxin, a molecule with activity similar to that of CNF1, has a higher affinity for p160/ROCK than GTP-bound RhoA (28). The strength and duration of cell signals issuing from the FAK-Src complex induced by PMT and CNF1 may also be different from those observed under normal routes of stimulation, in view of the stable nature of the complex whose formation is induced by the toxins. CNF1 is known to simultaneously activate different members of the Rho family and thereby perhaps induce conflicting signaling processes. Consequently, CNF1 and PMT not only may activate pathways that are normally regulated by active Rho proteins but also may stimulate pathways that are unique to toxin-treated cells and, hence, unique to their respective bacterial infections. With increased understanding of the molecular processes that are initiated by these toxins, their role in pathogenicity will become clearer.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council grant 18/ICR07622, by Wellcome Trust grant 049649, by a travel award from Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds, and by National Institutes of Health grant DK 59630 (to E.R.).

We thank Z. Ascott and J. Sinnett-Smith for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amano M, Mukai H, Ono Y, Chihara K, Matsui T, Mamajima Y, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Kaibuchi K. Identification of a putative target for Rho as the serine-threonine kinase protein kinase N. Science. 1996;271:648–650. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5249.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amano M, Chihara K, Kimura K, Fukata Y, Nakamura N, Matsuura Y, Kaibuchi K. Formation of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions enhanced by Rho-kinase. Science. 1997;275:1308–1311. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5304.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burridge K, Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M. Focal adhesions: contractility and signaling. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1996;12:463–518. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caprioli A, Falbo V, Ruggeri F M, Baldassarri L, Bisicchia R, Ippolito G, Romoli E, Donelli G. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor production by hemolytic strains of Escherichia coli causing extraintestinal infections. J Clin Microbiol. 1987;25:146–149. doi: 10.1128/jcm.25.1.146-149.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caprioli A, Falbo V, Roda L G, Ruggeri F M, Zona C. Partial purification and characterization of an Escherichia coli toxic factor that induces morphological cell alterations. Infect Immun. 1983;39:1300–1306. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.3.1300-1306.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cary L A, Han D C, Polte T R, Hank S K, Guan J L. Identification of p130Cas as a mediator of focal adhesion kinase-promoted cell migration. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:211–221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.1.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cary L A, Chang J F, Guan J L. Stimulation of cell migration by overexpression of focal adhesion kinase and its association with Src and Fyn. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:1787–1794. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.7.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Rycke J, Phan-Thanh L, Bernard S. Immunochemical identification and biological characterization of cytotoxic necrotizing factor from Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:983–988. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.5.983-988.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Essler M, Hermann K, Amano M, Kaibuchi K, Heesemann J, Weber P C, Aepfelbacher M. Pasteurella multocida toxin increases endothelial permeability via Rho kinase and myosin light chain phosphatase. J Immunol. 1998;161:5640–5646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fiorentini C, Donelli G, Matarrese P, Fabbri A, Paradisi S, Boquet P. Escherichia coli cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1: evidence for induction of actin assembly by constitutive activation of the p21 Rho GTPase. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3936–3944. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.3936-3944.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Flatau G, Lemichez E, Gauthier M, Chardin P, Paris S, Fiorentini C, Boquet P. Toxin-induced activation of the G protein p21 Rho by deamidation of glutamine. Nature. 1997;387:729–733. doi: 10.1038/42743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frisch S M, Vuori K, Ruoslahti E, Chan-Hui P Y. Control of adhesion-dependent cell survival by focal adhesion kinase. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:793–799. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.3.793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilmore A P, Romer L H. Inhibition of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) signaling in focal adhesions decreases cell motility and proliferation. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1209–1224. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.8.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanks S K, Polte T R. Signaling through focal adhesion kinase. Bioessays. 1997;19:137–145. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harte M T, Hildebrand J D, Burnham M R, Parsons J T. p130CAS, a substrate associated with v-Src and v-Crk, localizes to focal adhesions and binds to focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13649–13655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins T E, Murphy A C, Staddon J M, Lax A J, Rozengurt E. Pasteurella multocida toxin is a potent inducer of anchorage-independent cell growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4240–4244. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hungerford T E, Compton M T, Matter M L, Hoffstrom B G, Otey C A. Inhibition of pp125FAK in cultured fibroblasts results in apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:1383–1390. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.5.1383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilic D, Damsky C H, Yamamoto T. Focal adhesion kinase: at the crossroads of signal transduction. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:401–407. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ilic D, Furuta Y, Kanazawa S, Takeda N, Sobue K, Nakatsuji N, Nomura S, Fujimoto J, Okada M, Yamamoto T, Aizawa S. Reduced cell motility and enhanced focal contact formation in cells from FAK-deficient mice. Nature. 1995;377:539–544. doi: 10.1038/377539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishizaki T, Maekawa M, Midori F, Fujisawa K, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Fujita A, Wantanabe N, Saito Y, Kakizuka A, Morii N, Narumija S. The small GTP-binding protein Rho binds to and activates a 160-kDa Ser/Thr protein kinase homologous to myotonic dystrophy kinase. EMBO J. 1996;15:1885–1893. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishizaki T, Naito M, Fujiwara K, Maekawa M, Watanabe N, Saito Y, Narumiya S. p160/ROCK, a Rho-associated coiled-coil forming protein kinase, works downstream of Rho and induces focal adhesions. FEBS Lett. 1997;404:118–124. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00107-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lacerda H M, Lax A J, Rozengurt E. Pasteurella multocida toxin, a potent intracellularly acting mitogen, induces p125FAK and paxillin tyrosine phosphorylation, actin stress fiber formation, and focal contact assembly in Swiss 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:439–445. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.1.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lacerda H M, Pullinger G D, Lax A J, Rozengurt E. Cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 from Escherichia coli and dermonecrotic toxin from Bordetella bronchiseptica induce p21rho-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation of focal adhesion kinase and paxillin in Swiss 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:9587–9596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.14.9587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lemichez E, Flatau G, Bruzzone M, Boquet P, Gauthier M. Molecular localization of the Escherichia coli cytotoxic necrotizing factor CNF1 cell-binding and catalytic domains. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1061–1070. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4151781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lerm M, Selzer J, Hoffmeyer A, Rapp U R, Aktories K, Schmidt G. Deamidation of Cdc42 and Rac by Escherichia coli cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1: activation of c-Jun N-terminal kinase in HeLa cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:496–503. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.496-503.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leung T, Chen X-Q, Manser E, Lim L. The p160 RhoA-binding kinase ROKα is a member of a kinase family and is involved in the reorganization of the cytoskeleton. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5313–5327. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maekawa M, Ishizaki T, Boku S, Watanabe N, Fujita A, Iwamatsu A, Obinata T, Ohasi K, Mizuno K, Narumiya S. Signaling from Rho to the actin cytoskeleton through protein kinases ROCK and LIM-kinase. Science. 1999;285:895–898. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Masuda M, Betancourt L, Matsuzawa T, Kashimoto T, Takao T, Shimonishi Y, Horiguchi Y. Activation of rho through a cross-link with polyamines catalyzed by Bordetella dermonecrotizing toxin. EMBO J. 2000;19:521–530. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.4.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy A C, Rozengurt E. Pasteurella multocida toxin selectively facilitates phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate hydrolysis by bombesin, vasopressin, and endothelin. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:25296–25303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagumo H, Sasaki Y, Ono Y, Okamoto H, Seto M, Takuwa Y. Rho kinase inhibitor HA-1077 prevents Rho-mediated myosin phosphatase inhibition in smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol. 2000;278:C57–C65. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.1.C57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Parsons J T, Parsons S J. Src family protein tyrosine kinases: cooperating with growth factor and adhesion signaling pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:187–192. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pawson T. Protein modules and signaling networks. Nature. 1995;373:573–580. doi: 10.1038/373573a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polte T R, Hanks S K. Interaction between focal adhesion kinase and Crk-associated tyrosine substrate p130Cas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10678–10682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reid T, Furuyashiki T, Ishizaki T, Watanabe G, Watanabe N, Fujisawa K, Morii N, Madaule P, Narumiya S. Rhotekin, a new putative target for rho bearing homology to a serine/threonine kinase, PKN, and rhophilin in the rho-binding domain. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13556–13560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Fernandez J L, Rozengurt E. Bombesin, bradykinin, vasopressin, and phorbol esters rapidly and transiently activate Src family tyrosine kinases in Swiss 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27895–27901. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rodriguez-Fernandez J L, Rozengurt E. Bombesin, vasopressin, lysophosphatidic acid, and sphingosylphosphorylcholine induce focal adhesion kinase activation in intact Swiss 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19321–19328. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rozengurt E. Convergent signaling in the action of integrins, neuropeptides, growth factors and oncogenes. Cancer Surv. 1995;24:81–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rozengurt E. Signal transduction pathways in the mitogenic response to G protein-coupled neuropeptide receptor agonists. J Cell Physiol. 1998;177:507–517. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4652(199812)177:4<507::AID-JCP2>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rozengurt E, Sinnett-Smith J. Bombesin stimulation of DNA synthesis and cell division in cultures of Swiss 3T3 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:2936–2940. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.10.2936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rozengurt E, Higgins T E, Chanter N, Lax A J, Staddon J M. Pasteurella multocida toxin: potent mitogen for cultured fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:123–127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salazar E P, Rozengurt E. Bombesin and platelet-derived growth factor induce association of endogenous focal adhesion kinase with Src in intact Swiss 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28371–28378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt G, Selzer J, Lerm M, Aktories K. The rho-deamidating cytotoxic necrotizing factor 1 from Escherichia coli possesses transglutaminase activity. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13669–13674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmidt G, Sehr P, Wilm M, Selzer J, Mann M, Aktories K. Gln 63 of Rho is deamidated by Escherichia coli cytotoxic necrotizing factor-1. Nature. 1997;387:725–729. doi: 10.1038/42735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Seo B, Choy E W, Maudseley S, Miller W E, Wilson B A, Luttrell L M. Pasteurella multocida toxin stimulates mitogen-activated protein kinase via Gq/11-dependent transactivation of the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2239–2245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.3.2239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seufferlein T, Withers D J, Mann D, Rozengurt E. Dissociation of mitogen-activated protein kinase activation from p125 focal adhesion kinase tyrosine phosphorylation in Swiss 3T3 cells stimulated by bombesin, lysophosphatidic acid, and platelet-derived growth factor. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1865–1875. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.12.1865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Staddon J M, Baker C J, Murphy A C, Chanter N, Lax A J, Michell R H, Rozengurt E. Pasteurella multocida toxin, a potent mitogen, increases inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate and mobilizes Ca2+ in Swiss 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4840–4847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Staddon J M, Chanter N, Lax A J, Higgins T E, Rozengurt E. Pasteurella multocida toxin, a potent mitogen, stimulates protein kinase C-dependent and -independent protein phosphorylation in Swiss 3T3 cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11841–11848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tachibana K, Urano T, Fujita H, Ohashi Y, Kamiguchi K, Iwata S, Hirai H, Morimoto C. Tyrosine phosphorylation of Crk-associated substrates by focal adhesion kinase. A putative mechanism for the integrin-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of Crk-associated substrates. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:29083–29090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.29083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thomas J W, Ellis B, Boerner R J, Knight W B, White II G C, Schaller M D. SH2- and SH3-mediated interactions between focal adhesion kinase and Src. J Biol Chem. 1999;273:577–583. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Uehata M, Ishizaki T, Ono T, Kawahara T, Morishita T, Tamakawa H, Yamagami K, Inui J, Maekawa M, Narumija S. Calcium sensitization of smooth muscle mediated by a Rho-associated protein kinase in hypertension. Nature. 1997;389:990–994. doi: 10.1038/40187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ward P N, Miles A J, Sumner I G, Thomas L H, Lax A J. Activity of the mitogenic Pasteurella multocida toxin requires an essential C-terminal residue. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5636–5642. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5636-5642.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watanabe G, Saito Y, Madaule P, Ishizaki T, Fujisawa K, Morii N, Mukai H, Ono Y, Kakizuka A, Narumiya S. Protein kinase N (PKN) and PKN-related protein rhophilin as targets of small GTPase Rho. Science. 1996;271:645–648. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5249.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson B A, Zhu X, Ho M, Lu L. Pasteurella multocida toxin activates the inositol triphosphate signaling pathway in Xenopus oocytes via a Gqα-coupled phospholipase C-β1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1268–1275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu L H, Owens L V, Sturge G C, Yang X, Liu E T, Craven R J, Cance W G. Attenuation of the expression of the focal adhesion kinase induces apoptosis in tumor cells. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:413–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zachary L, Rozengurt E. Focal adhesion kinase (p125FAK): a point of convergence in the action of neuropeptides, integrins, and oncogenes. Cell. 1992;71:891–894. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90385-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]