In the last few years, in the context of a growing interest in investigating novel pathways involved in heart failure (HF) pathophysiology, the association between the gastrointestinal (GI) system and HF represents an important model of attention, the so called ‘gut hypothesis’. 1 , 2 , 3 Despite being classically identified as a ‘simple’ intestinal dysfunction, the main hypothesis is currently focused on the role of inflammation and oxidative stress as a consequence of the intestinal wall ischaemia and/or congestion induced by HF, determining a gut barrier dysfunction and resulting in an increased gut bacterial translocation. 1 , 2 , 3 With this in mind, two main mechanisms have been proposed to link gut dysfunction and HF; (i) metabolism dependent, via gut‐derived metabolites entering the systemic circulation and exerting pro‐atherogenic effects and pro‐inflammatory effects and (ii) metabolism independent, via bacterial components (e.g. lipopolysaccharides and endotoxins) translocating in the systemic circulation and contributing to the systemic inflammatory state with its well‐known negative effects on HF. 4

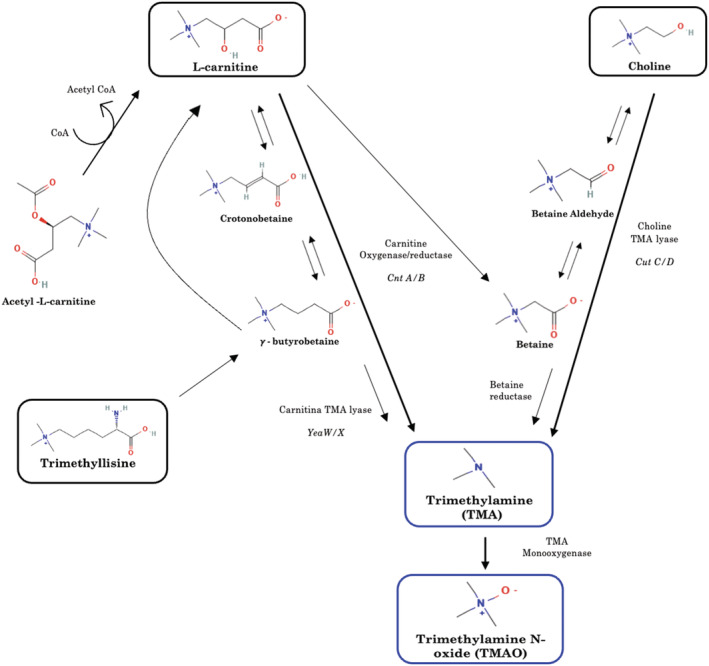

To date, most of the research has identified a choline and L‐carnitine metabolic by‐product, trimethylamine N‐oxide (TMAO), derived by the gut microbiota from the precursor trimethylamine (TMA) and subsequent oxidation via the liver enzyme flavin‐containing monooxygenase 3 (FMO3) (see Figure 1 ), as the key useful prognostic biomarker in several cardiovascular diseases (e.g. coronary artery disease, acute myocardial infarction, and HF), with an interesting role in risk stratification. 5 , 6 Notably, TMAO, produced through the anaerobic metabolism of choline and carnitine containing molecules, is widely considered as the possible missing link between the consumption of a Western diet and the well‐known increased cardiovascular diseases risk observed in the Western population. 7 Indeed, TMAO is produced through the anaerobic metabolism of choline and L‐carnitine, of which eggs and red meat are rich in the Western diet (i.e., based on high fat foods), and diet can be considered as one the of most important factors affecting the gut microbiota composition. 8

Figure 1.

Multiple pathways and metabolites involved in the synthesis of trimethylamine N‐oxide (TMAO).

Amongst the cardiovascular diseases, HF represents a widely investigated disease for association with the gut, with evidence available in both reduced (HFrEF) 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 and preserved (HFpEF) 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 phenotypes, as well as in acute 12 , 13 , 28 , 29 , 30 and chronic setting 9 , 10 , 11 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 27 (see Table 1 ). From a pathophysiological point of view, TMAO pathway affects HF in different ways. 1 , 3 First, TMAO increases the risk of conditions determining HF (i.e. cardiac ischemic diseases), through its pro‐atherosclerotic effects mediated by an increase in the expression of macrophage scavenger receptors with development of foam cells in the arterial wall, increasing thrombosis, increasing platelet reactivity, and causing endothelial dysfunction. 1 , 3 Second, TMAO increases HF susceptibility, directly acting on myocardial remodelling and fibrosis; in addition, it has been speculated that TMAO, being an organic osmolyte, altered cellular osmosis; lastly, it has been showed that TMAO worsens cardiomyocyte contractility, by acting on calcium cellular fluxes. 1 , 3 Worthy to be mentioned is the relationship between TMAO and renal function, with a possible effect on renal fibrosis and tubular injury further aggravating HF clinic. 1 , 3

Table 1.

Main reports for associations between trimethylamine N‐oxide and outcome in heart failure patients

| First author; year of publication | Location | Study population | Follow‐up length | Main findings | Trimethylamine N‐oxide levels (μmol/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tang WH 2014 9 | USA | CHF, N = 720 | 5 years |

|

5.0 (3.0–8.5) |

| Tang WH 2015 10 | USA | CHF, N = 112 | 5 years |

|

5.8 (3.6–12.1) |

| Trøseid M 2015 11 | Norway | CHF N = 115 | 5.2 years |

|

13.5 ± 18.5 (CAD), 7.1 ± 5.6 (DCM) |

| Suzuki T 2016 12 | UK | AHF, N = 972 | 1 years |

|

5.6 (3.4–10.5) |

| Schuett K 2017 22 | Germany | CHF (pEF and rEF), N = 823 | 9.7 years |

|

4.7 (3.4–6.8) rEF, 4.7 (3.2–6.9) pEF |

| Hayashi T 2018 13 | Japan | Decomp HF, N = 22 | Cross‐sectional |

|

17.3 ± 11.7 (Decomp), 17.7 ± 12.6 (Comp) |

| Salzano A 2019 23 | UK | CHF (pEF and rEF), pEF = 118 vs rEF = 38 vs C = 40, N = 196 | 5 years |

|

6.6 (4.3–12.2) pEF, 8.4 (3.7–13.8) rEF |

| Suzuki T 2019 14 | 11 European countries | Worsening or new‐onset HF, N = 2234 | 3 years |

|

5.9 (3.6–10.8) |

| Yazaki Y 2019 31 | 11 European countries | Worsening or new‐onset HF, N = 2234 | 2 years |

|

6.2 (4.8–7.8) CE, 7.2 (5.5–8.8) NW, 6.5 (5.0–8.2) S |

| Zhou X 2020 16 | China | HFrEF after MI, N = 1208 | 4 years |

|

4.5 |

| Yazaki Y 2020 28 | UK | AHF, N = 1087 | 1 year |

|

5.2–22.8 (Japanese), 3.6–10.8 (Caucasian), 3.1–8.4 (South Asian) |

| Guo F 2020 24 | China | HFpEF, N = 228 | 5 years |

|

12.65 (9.32–18.66) |

| Emoto T 2021 25 | CHF (pEF and rEF), CHF = 22 vs C = 11, N = 33 |

|

4.5–34.5 | ||

| Papandreou C 2021 17 | Spain | CHF (pEF and rEF), AF = 509 vs C = 618, CHF = 326 vs C = 426, N = 1879 | 10 years |

|

3.0–8.5 |

| Kinugasa Y 2021 26 | Japan | HFpEF, N = 146 | 5 years |

|

20.37 |

| Israr MZ 2021 30 | UK | AHF, N = 806 | 1 years |

|

10.2 (5.8–18.7) |

| Dong Z 2021 27 | China | HFpEF, CHF = 61 vs C = 57, N = 118 | 1 years |

|

6.84 |

| Yuzefpolskaya M 2021 18 | USA | CHF, N = 341 | 2 years + 8 months |

|

6.96 (HF), 5.81 (LVAD), 5.35 (HT) |

| Mollar A 2021 19 | Spain | Decomp HF, N = 102 | 1 years |

|

|

| Wargny M 2022 32 | France |

AHF, AHF = 209 vs C = 1140, N = 1468 |

7.3 years |

|

8.8 (5.3–17.0) |

| Li N 2022 29 | China | AMI and HF, N = 985 | 1 years |

|

6.7 (4.0, 11.7) |

| Wei H 2022 20 | China | HFrEF, N = 955 | 8 years |

|

2.52 (1.18–4.06) |

| Israr MZ 2022 21 | UK | HFrEF, N = 1783 | 3 years |

|

6.4 (3.9–11.6) |

Abbreviations: AF, atrial fibrillation; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; AHF, acute heart failure; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; C, controls; CAD, coronary artery disease; CE, Central/Eastern group (Germany, Poland, Serbia, and Slovenia); CHF, chronic heart failure; cntA/B, carnitine oxygenase/reductase; Comp, compensated; DCM, dilated cardiomyopathy; Decomp, decompensated; ET‐1, endothelin‐1; HF, heart failure; HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; HFrEF, heart failure with reduced ejection fraction; hsCRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; HT, heart transplant; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; MACE, major adverse cardiac events; MI, myocardial infarction; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal pro‐brain type natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; NW, the Northern/Western group (France, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and United Kingdom); S, Southern group (Greece and Italy); sCD14, soluble CD14; TMAO, trimethylamine N‐oxide; TNF‐α, tumour necrosis factor alpha. TMAO levels expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range).

From a clinical point of view, since the first investigations regarding the association between TMAO and HFrEF as of about 10 years ago, 9 several studies have demonstrated that TMAO levels were higher in CHF when compared with healthy controls showing associations between TMAO and clinical and biochemical parameters (i.e., renal function, age, comorbidities, and CRP), severity of disease (NYHA classes), 15 , 18 and clinical outcomes (death, HF hospitalization, composite). 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 As a prototype, in the BIOSTAT‐CHF (BIOlogy Study to TAilored Treatment in Chronic Heart Failure) population, in which 2234 patients with new‐onset or progressively worsening HF have been investigated, TMAO levels were associated with adverse outcomes (mortality and/or rehospitalisation) at different time‐points (1, 2, and 3 years). 14 Despite being the most prevalent phenotype in HF, only a few studies (when compared with the numerosity of study about HFrEF phenotype) have investigated the association of TMAO with outcome in HFpEF subjects. 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 The Developing Imaging And plasMa biOmarkers iN Describing Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction (DIAMONDHFpEF) cohort showed that TMAO was associated with adverse outcome in HFpEF and that its use allows a better stratification of HFpEF patients when used in combination with BNP. 23 Considering that natriuretic peptides are not as highly elevated in HFpEF compared with HFrEF, in this cohort elevated TMAO levels improved risk stratification of patients in which BNP levels show equivocal levels.

The role of TMAO in risk stratification is not limited to the chronic setting; indeed, TMAO showed its value also in the acute setting, in which elevated levels (except in one investigation) 32 showed to be associated with a poor prognosis. 12 , 13 , 28 , 29 , 30 For instance, in a cohort of 972 acute HF patients, TMAO levels were associated with a more reduced left ventricular ejection fraction, a more advanced clinical status (i.e. NYHA classes III‐IV), and with poor outcome. 12 Interestingly, even in this setting, TMAO showed to improve risk stratification when combined with clinical scores [i.e., Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE), Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE‐HF), Get With The Guidelines‐Heart Failure (GWTG‐HF)], and with NT‐proBNP. 12

Finally, when all these findings have been analysed in three independent meta‐analyses, consistent results show elevated TMAO levels are associated with poor prognosis (i.e., MACE and all‐cause mortality) in HF patients, even when adjusted for multiple confounders. 33 , 34 , 35

In this context, in the present issue of the ESC Heart Failure journal, Li et al. showed that elevated TMAO levels were associated with poor prognosis (i.e. all‐cause death and recurrence of myocardial infarction) in patients with acute myocardial infarction complicated by HF, 29 further validating current understanding. 12 , 36 Specifically, the authors found that patients with higher sensitivity C‐reactive protein (hsCRP) levels resulted in a further significant stratification of TMAO by tertiles for MACE. This is of great interest, because it has been suggested that, mechanistically, TMAO induces HF and myocardial ischaemia via mechanisms including inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, production of oxygen‐free radicals, and myocardial fibrosis. 1 These mechanisms play an important role in the development and progression of plaques, lipid deposition to plaque rupture, and its eventual complications. 37 In addition, it has been shown that bowel thickness was directly correlated with circulating hsCRP levels, 1 further supporting the role of a bacterial translocation in HF and their association with systemic inflammation. When investigating the role of TMAO considering its involvement with CRP, current evidence suggests that TMAO activates different signalling pathways; for example, the nuclear factor‐ᴋB signalling pathway to induce inflammation by TMAO 38 or by activating the nucleotide‐binding oligomerization domain‐like receptor family pyrin domain‐containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome and subsequently triggering systemic inflammation. 39 Intriguingly, the present paper showed that increasing hsCRP might increase the association of TMAO levels with HF outcome, suggesting a potential synergistic effect between TMAO and inflammation.

Another finding of interest of the present investigation, considering the positive dose‐dependent association between TMAO plasma levels and increased cardiovascular risk and mortality, 33 is the evidence that TMAO levels were significantly more increased in HFrEF than in HFpEF, reflecting the different pathophysiology underpinning the two phenotypes.

One important limitation for the present study is the lack of dietary information. Indeed, adjusting TMAO data for dietary information is paramount to ascribing the ‘true’ normal ranges, association with HF/MI and intervention in a ‘real‐world’ scenario. To elaborate, TMAO levels in Caucasian patients showed increased association with adverse outcomes, but not in non‐Caucasian patients despite any differences between ethnicity and association with outcome, suggesting that dietary sources could be the contributing factor. 28 Furthermore, when a diet‐based categorization of country was applied for a European‐wide study, TMAO levels in HF patients differed by region and a different association with outcome was observed for mortality risk. 31

Notably, TMAO is just the ‘tip of the iceberg’ of one of the complex pathways involved in the association between the gut and the cardiac metabolism (i.e. short‐chain fatty acids, bile acids, and TMA‐TMAO). 1 In this context, novel evidence showed that also other metabolites of the TMAO pathway (Figure 1 ) are involved in HF with a promising prognostic role. Specifically, the carnitine‐related metabolites have shown associations with adverse outcomes in acute HF, in particular L‐carnitine and acetyl‐L‐carnitine for short‐term outcomes. 30 In addition, data from the BIOSTAT‐CHF study showed that acetyl‐L‐carnitine, gamma‐butyrobetaine, and L‐carnitine were associated with outcome at 3 years, with a graded association when combined alone or with markers of gut dysfunction (i.e., a ‘panel of gut dysfunction’) with clinical status, NPs levels, and outcome. 21

The importance of the association between GI and HF goes further with the identification of novel biomarkers for risk stratification. 3 Considering that TMAO levels were not affected by recommended HF therapy, the ‘gut–HF axis’ may represent a novel field of interest for future research; specifically, a targeted therapy aimed to modify the gut microbiota could be a novel therapeutic approach. However, to date, no large‐scale trials have been performed to test this hypothesis.

In conclusion, data available from literature so far have shown that TMAO levels are increased in HF patients compared with healthy subjects and that elevated levels are associated with a poor prognosis. Although additional studies needed to address the current limitations in the field, TMAO, its precursors, and the gut‐derived biomarkers in general, represent a promising biomarkers of risk stratification with a possible role as a therapeutic target in the future.

Conflict of interest

None.

Crisci, G. , Israr, M. Z. , Cittadini, A. , Bossone, E. , Suzuki, T. , and Salzano, A. (2023) Heart failure and trimethylamine N‐oxide: time to transform a ‘gut feeling’ in a fact?. ESC Heart Failure, 10: 1–7. 10.1002/ehf2.14205.

[Correction added on 17 November 2022, after first online publication: The following changes have been made in this version: (1) the affiliation of Professor Toru Suzuki has been changed to affiliation 3; (2) Dr Andrea Salzano was set as the corresponding author.]

References

- 1. Tang WHW, Li DY, Hazen SL. Dietary metabolism, the gut microbiome, and heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol 2019; 16: 137–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Krack A, Sharma R, Figulla HR, Anker SD. The importance of the gastrointestinal system in the pathogenesis of heart failure. Eur Heart J 2005; 26: 2368–2374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Salzano A, Cassambai S, Yazaki Y, Israr MZ, Bernieh D, Wong M, Suzuki T. The gut axis involvement in heart failure: focus on trimethylamine N‐oxide. Heart Fail Clin 2020; 16: 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marra AM, Arcopinto M, Salzano A, Bobbio E, Milano S, Misiano G, Ferrara F, Vriz O, Napoli R, Triggiani V, Perrone‐Filardi P, Saccà F, Giallauria F, Isidori AM, Vigorito C, Bossone E, Cittadini A. Detectable interleukin‐9 plasma levels are associated with impaired cardiopulmonary functional capacity and all‐cause mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2016; 209: 114–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tousoulis D, Guzik T, Padro T, Duncker DJ, de Luca G, Eringa E, Vavlukis M, Antonopoulos AS, Katsimichas T, Cenko E, Djordjevic‐Dikic A, Fleming I, Manfrini O, Trifunovic D, Antoniades C, Crea F. Mechanisms, therapeutic implications, and methodological challenges of gut microbiota and cardiovascular diseases: a position paper by the ESC Working Group on Coronary Pathophysiology and Microcirculation. Cardiovasc Res 2022; cvac057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anderson KM, Ferranti EP, Alagha EC, Mykityshyn E, French CE, Reilly CM. The heart and gut relationship: a systematic review of the evaluation of the microbiome and trimethylamine‐N‐oxide (TMAO) in heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 2022; 27: 2223–2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cassambai S, Salzano A, Yazaki Y, Wong M, Israr MZ, Heaney LM, Suzuki T, Suzuki T. Impact of acute choline loading on circulating trimethylamine N‐oxide levels. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2019; 26: 1899–1902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA, Biddinger SB, Dutton RJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature 2014; 505: 559–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tang WH, Wang Z, Fan Y, Levison B, Hazen JE, Donahue LM, Wu Y, Hazen SL. Prognostic value of elevated levels of intestinal microbe‐generated metabolite trimethylamine‐N‐oxide in patients with heart failure: refining the gut hypothesis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 64: 1908–1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tang WH, Wang Z, Shrestha K, Borowski AG, Wu Y, Troughton RW, Klein AL, Hazen SL. Intestinal microbiota‐dependent phosphatidylcholine metabolites, diastolic dysfunction, and adverse clinical outcomes in chronic systolic heart failure. J Card Fail 2015; 21: 91–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trøseid M, Ueland T, Hov JR, Svardal A, Gregersen I, Dahl CP, Aakhus S, Gude E, Bjørndal B, Halvorsen B, Karlsen TH, Aukrust P, Gullestad L, Berge RK, Yndestad A. Microbiota‐dependent metabolite trimethylamine‐N‐oxide is associated with disease severity and survival of patients with chronic heart failure. J Intern Med 2015; 277: 717–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Suzuki T, Heaney LM, Bhandari SS, Jones DJ, Ng LL. Trimethylamine N‐oxide and prognosis in acute heart failure. Heart 2016; 102: 841–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hayashi T, Yamashita T, Watanabe H, Kami K, Yoshida N, Tabata T, Emoto T, Sasaki N, Mizoguchi T, Irino Y, Toh R, Shinohara M, Okada Y, Ogawa W, Yamada T, Hirata KI. Gut microbiome and plasma microbiome‐related metabolites in patients with decompensated and compensated heart failure. Circ J 2018; 83: 182–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Suzuki T, Yazaki Y, Voors AA, Jones DJL, Chan DCS, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Hillege HL, Lang CC, Ponikowski P, Samani NJ, van Veldhuisen DJ, Zannad F, Zwinderman AH, Metra M, Ng LL. Association with outcomes and response to treatment of trimethylamine N‐oxide in heart failure: results from BIOSTAT‐CHF. Eur J Heart Fail 2019; 21: 877–886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dong Z, Liang Z, Wang X, Liu W, Zhao L, Wang S, Hai X, Yu K. The correlation between plasma trimethylamine N‐oxide level and heart failure classification in northern Chinese patients. Ann Palliat Med 2020; 9: 2862–2871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Zhou X, Jin M, Liu L, Yu Z, Lu X, Zhang H. Trimethylamine N‐oxide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure after myocardial infarction. ESC Heart Fail 2020; 7: 189–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Papandreou C, Bulló M, Hernández‐Alonso P, Ruiz‐Canela M, Li J, Guasch‐Ferré M, Toledo E, Clish C, Corella D, Estruch R, Ros E, Fitó M, Alonso‐Gómez A, Fiol M, Santos‐Lozano JM, Serra‐Majem L, Liang L, Martínez‐González MA, Hu FB, Salas‐Salvadó J. Choline metabolism and risk of atrial fibrillation and heart failure in the PREDIMED study. Clin Chem 2021; 67: 288–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yuzefpolskaya M, Bohn B, Javaid A, Mondellini GM, Braghieri L, Pinsino A, Onat D, Cagliostro B, Kim A, Takeda K, Naka Y, Farr M, Sayer GT, Uriel N, Nandakumar R, Mohan S, Colombo PC, Demmer RT. Levels of trimethylamine N‐oxide remain elevated long term after left ventricular assist device and heart transplantation and are independent from measures of inflammation and gut dysbiosis. Circ Heart Fail 2021; 14: e007909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mollar A, Marrachelli VG, Núñez E, Monleon D, Bodí V, Sanchis J, Navarro D, Núñez J. Bacterial metabolites trimethylamine N‐oxide and butyrate as surrogates of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with a recent decompensated heart failure. Sci Rep 2021; 11: 6110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wei H, Zhao M, Huang M, Li C, Gao J, Yu T, Zhang Q, Shen X, Ji L, Ni L, Zhao C, Wang Z, Dong E, Zheng L, Wang DW. FMO3‐TMAO axis modulates the clinical outcome in chronic heart‐failure patients with reduced ejection fraction: evidence from an Asian population. Front Med 2022; 16: 295–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Israr MZ, Zhan H, Salzano A, Voors AA, Cleland JG, Anker SD, Metra M, van Veldhuisen D, Lang CC, Zannad F, Samani NJ, Ng LL, Suzuki T, BIOSTAT‐CHF investigators (full author list as appendix) . Surrogate markers of gut dysfunction are related to heart failure severity and outcome‐from the BIOSTAT‐CHF consortium. Am Heart J 2022; 248: 108–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schuett K, Kleber ME, Scharnagl H, Lorkowski S, März W, Niessner A, Marx N, Meinitzer A. Trimethylamine‐N‐oxide and heart failure with reduced versus preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017; 70: 3202–3204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Salzano A, Israr MZ, Yazaki Y, Heaney LM, Kanagala P, Singh A, Arnold JR, Gulsin GS, Squire IB, McCann G, Ng LL, Suzuki T. Combined use of trimethylamine N‐oxide with BNP for risk stratification in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: findings from the DIAMONDHFpEF study. Eur J Prev Cardiol 2019; 27: 2159–2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Guo F, Qiu X, Tan Z, Li Z, Ouyang D. Plasma trimethylamine n‐oxide is associated with renal function in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2020; 20: 394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Emoto T, Hayashi T, Tabata T, Yamashita T, Watanabe H, Takahashi T, Gotoh Y, Kami K, Yoshida N, Saito Y, Tanaka H, Matsumoto K, Hayashi T, Yamada T, Hirata KI. Metagenomic analysis of gut microbiota reveals its role in trimethylamine metabolism in heart failure. Int J Cardiol 2021; 338: 138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kinugasa Y, Nakamura K, Kamitani H, Hirai M, Yanagihara K, Kato M, Yamamoto K. Trimethylamine N‐oxide and outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail 2021; 8: 2103–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dong Z, Zheng S, Shen Z, Luo Y, Hai X. Trimethylamine N‐oxide is associated with heart failure risk in patients with preserved ejection fraction. Lab Med 2021; 52: 346–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yazaki Y, Aizawa K, Israr MZ, Negishi K, Salzano A, Saitoh Y, Kimura N, Kono K, Heaney L, Cassambai S, Bernieh D, Lai F, Imai Y, Kario K, Nagai R, Ng LL, Suzuki T. Ethnic differences in association of outcomes with trimethylamine N‐oxide in acute heart failure patients. ESC Heart Fail 2020; 7: 2373–2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li N, Zhou J, Wang Y, Chen R, Li J, Zhao X, Zhou P, Liu C, Song L, Liao Z, Wang X, Yan S, Zhao H, Yan H. Association between trimethylamine N‐oxide and prognosis of patients with acute myocardial infarction and heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 2022. 10.1002/ehf2.14009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Israr MZ, Bernieh D, Salzano A, Cassambai S, Yazaki Y, Heaney LM, Jones DJL, Ng LL, Suzuki T. Association of gut‐related metabolites with outcome in acute heart failure. Am Heart J 2021; 234: 71–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yazaki Y, Salzano A, Nelson CP, Voors AA, Anker SD, Cleland JG, Lang CC, Metra M, Samani NJ, Ng LL, Suzuki T. Geographical location affects the levels and association of trimethylamine N‐oxide with heart failure mortality in BIOSTAT‐CHF: a post‐hoc analysis. Eur J Heart Fail 2019; 21: 1291–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wargny M, Croyal M, Ragot S, Gand E, Jacobi D, Trochu JN, Prieur X, le May C, Goronflot T, Cariou B, Saulnier PJ, Hadjadj S, for the SURDIAGENE study group , Marechaud R, Javaugue V, Hulin‐Delmotte C, Llatty P, Ducrocq G, Roussel R, Rigalleau V, Pucheu Y, Montaigne D, Halimi JM, Gatault P, Sosner P, Gellen B. Nutritional biomarkers and heart failure requiring hospitalization in patients with type 2 diabetes: the SURDIAGENE cohort. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2022; 21: 101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Schiattarella GG, Sannino A, Toscano E, Giugliano G, Gargiulo G, Franzone A, Trimarco B, Esposito G, Perrino C. Gut microbe‐generated metabolite trimethylamine‐N‐oxide as cardiovascular risk biomarker: a systematic review and dose‐response meta‐analysis. Eur Heart J 2017; 38: 2948–2956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li W, Huang A, Zhu H, Liu X, Huang X, Huang Y, Cai X, Lu J, Huang Y. Gut microbiota‐derived trimethylamine N‐oxide is associated with poor prognosis in patients with heart failure. Med J Aust 2020; 213: 374–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li X, Fan Z, Cui J, Li D, Lu J, Cui X, Xie L, Wu Y, Lin Q, Li Y. Trimethylamine N‐oxide in heart failure: a meta‐analysis of prognostic value. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022; 9: 817396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Suzuki T, Heaney LM, Jones DJ, Ng LL. Trimethylamine N‐oxide and risk stratification after acute myocardial infarction. Clin Chem 2017; 63: 420–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Tan Y, Sheng Z, Zhou P, Liu C, Zhao H, Song L, Li J, Zhou J, Chen Y, Wang L, Qian H, Sun Z, Qiao S, Xu B, Gao R, Yan H. Plasma trimethylamine N‐oxide as a novel biomarker for plaque rupture in patients with ST‐segment–elevation myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2019; 12: e007281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Seldin MM, Meng Y, Qi H, Zhu WF, Wang Z, Hazen SL, Lusis AJ, Shih DM. Trimethylamine N‐oxide promotes vascular inflammation through signaling of mitogen‐activated protein kinase and nuclear factor‐κB. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5: e002767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen M‐L, Zhu X, Ran L, Lang HD, Yi L, Mi MT. Trimethylamine‐N‐oxide induces vascular inflammation by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through the SIRT3‐SOD2‐mtROS signaling pathway. J Am Heart Assoc 2017; 6: e006347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]