Abstract

Background:

Adolescent asthma is highly prevalent and frequently uncontrolled despite control being achievable with good self-management. Anxiety, depression, and stress are associated with worse asthma outcomes, and may impact self-management; no previous review has examined this relationship.

Aim:

This scoping review assessed the nature of the current literature on mental health and asthma self-management among adolescents ages 11 to 24 and synthesized their relationships.

Methods:

Guided by the PRISMA-ScR guidelines, we systematically searched the literature using MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo, and Scopus in September 2020 and updated it in June 2021. Included studies examined associations between anxiety, depression, and/or stress and asthma self-management in adolescents ages 11–24. We did not restrict study design, location, or date.

Results:

Out of 1,559 records identified, 14 met inclusion criteria. Types of self-management included trigger control, healthcare adherence, and overall symptom prevention and management. Anxiety symptoms were associated with poorer asthma self-management in four studies, but better in three. Depressive symptoms were associated with poorer asthma self-management in five studies, but better in two. Stress was associated with poorer self-management in one study. Mental health symptoms were nearly universally associated with poorer trigger control, but associations with healthcare adherence and overall symptom prevention and management varied.

Conclusion:

Mental health symptoms may facilitate or hinder asthma self-management depending on the types of mental health and self-management. Further research is needed to better understand this relationship and inform future interventions. Providers might assess mental health as a potential barrier to adolescent asthma self-management.

Keywords: anxiety, depression, pediatric, self-care, stress

1. Introduction

Asthma is among the most common medical conditions among adolescents ages 11–21, with a current prevalence rate of 8.7 percent in the United States.1 Current asthma prevalence among older adolescents ages 20–24 years is even higher at 9.9 percent.1 With proper self-management, the majority of asthma patients could achieve proper asthma control, yet uncontrolled asthma continues to be a source of significant health and economic burden.2 Uncontrolled asthma among adolescents, in particular, continues to be a major public health burden with missed school days and asthma-related emergency room visits and hospitalizations.3,4 The reasons underlying uncontrolled asthma are complex, and the specific causes of differences in asthma control outcomes across pediatric populations are not yet well-understood.5,6 Two factors that have been identified as challenges to asthma outcomes in adolescents are mental health and self-management.7

Asthma in adolescence is associated with increased incidence of anxiety and depressive symptoms and disorders.8–10 Among adolescents with asthma, anxiety and depression are associated with increased severity, worse control, increased emergency department visits, and reduced quality of life.5,11–16 Stress is another important aspect of mental health for youth living with asthma.17 Though fewer studies have been published on adolescents compared to children or adults, exposure to stress at any level (individual, family, or community) or duration (acute or chronic) has been found to be associated with higher asthma rates and worse asthma outcomes.18 Moreover, there is evidence suggesting a causal association between chronic psychosocial stress and asthma prevalence and morbidity, particularly among systematically oppressed demographic groups including some racial and ethnic minorities.19

Asthma self-management also has important implications for asthma outcomes. Self-management is defined as actions patients take to control their asthma, including engagement in health-promoting practices to prevent symptoms and management of acute symptoms.20,21 Better self-management has been linked to better asthma control and less morbidity.16,22 Therefore, improving adolescents’ self-management is important to helping them achieve asthma control. Understanding factors associated with self-management is an important first step in finding ways to improve self-management behaviors, and mental health is one such factor.

While both mental health symptoms and asthma self-management have consistently been found to be associated with asthma outcomes, associations between them are less widely studied. Increased understanding of the relationship between mental health symptoms and asthma self-management has the potential to improve asthma outcomes by informing targeted interventions. Despite the importance of understanding this relationship, preliminary searches of PubMed and Google Scholar indicated that associations of mental health and asthma self-management in adolescents have yet to be synthesized in a review paper. Therefore, given the relatively nascent state of research on adolescent mental health and asthma self-management, we conducted a scoping review.

2. Aims

The aims of this scoping review were (1) to assess the nature of the current literature on the mental health and asthma self-management among adolescents ages 11 to 24 and (2) to synthesize their relationships.

3. Methods

We conducted a scoping review to allow for a broad evaluation of the scientific evidence regarding mental health and asthma self-management among adolescents.23,24 To increase the rigor of this scoping review, we conducted it using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Guidelines for Scoping Reviews25 and adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).26 The protocol for this scoping review was uploaded to Open Science Framework on December 15, 2020, and can be accessed at the following link: https://osf.io/5pnrx/.

3.1. Search Strategy and Study Selection

A comprehensive search of the literature was conducted in the following databases on September 9, 2020: MEDLINE (PubMed), Embase, CINAHL (EBSCO), PsycInfo (Ovid), and Scopus. The full search strategies are available in Appendix A. Given the amount of time that passed between the search and completion of the manuscript, it was determined that an update of the search should be conducted. The search was run again on June 9, 2021. It should be noted that in the updated search, PsycInfo was no longer available through Ovid at the institution. Therefore, PsycInfo was searched via the EBSCO platform. The full search strategies of the re-run search are also available in Appendix A.

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

3.2.1. Study Characteristics and Population

Quantitative and qualitative empirical published studies examining associations between asthma self-management and anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms, and/or stress were included. Non-empirical studies, such as reviews or commentaries were excluded. Publications in English, Spanish, or French were included, and there was no publication date limit specified for this review. The population of interest was adolescents ages 11 to 24 with asthma. We chose the upper age limit of 24 because the end of adolescence, typically defined by social roles, has been recently expanded due to delayed timing of social transitions (e.g., completion of education and marriage);27 this broader range also is consistent with the purpose of a scoping review, namely, to have cast a broad net around the literature.

3.2.2. Predictors

Studies that assessed anxiety, depression or stress were included. We chose these three types of mental health because they are commonly experienced by adolescents with asthma8–10,17 and, as noted above, are known to be associated with worse asthma outcomes.5,11–16,18,19 Additionally, in our collective clinical and research experience, these are the types of mental health that are most often discussed by adolescents in the context of their asthma self-management.

Anxiety could be of any type (e.g., generalized anxiety, social anxiety, asthma-related anxiety). Studies that only assessed post-traumatic stress disorder were excluded because while it is considered an anxiety disorder, it is specific to trauma. There was no limit on the source of data collection; instead, mental health (i.e., anxiety, depression, and stress) could be assessed via self-report, report by another individual (e.g., parent, teachers), or chart review. For anxiety and depression, studies that assessed symptoms or diagnoses were included. For stress, all studies assessing acute or chronic psychosocial stress were included.

3.2.3. Outcomes

Studies must have reported some aspect of asthma self-management, which could have included trigger control, healthcare adherence, and overall measures of symptom prevention and management. For the purposes of this scoping review, self-management was defined broadly. Therefore, because inhaled substances are a known trigger and exposure to them indicates poor trigger control,16 studies measuring inhaled substance use were included. However, because exposure to environmental irritants such as second-hand smoke is often not within an adolescent’s individual control, only studies including inhaled substance use by the adolescent themself were included. Similarly, studies measuring any aspect of asthma-related healthcare adherence, such as receiving recommended preventive care, receiving care to address asthma symptoms, and adherence to prescribed asthma medications, were included. Outcomes could be assessed objectively or subjectively.

3.3. Study Selection

Search results were downloaded into an EndNote Citation Manager library. The EndNote library was used to remove duplicate records. The unique records to be considered for the review were then uploaded into Covidence (https://www.covidence.org), a web-based systematic review platform. Covidence was used to organize and facilitate screening and data extraction.

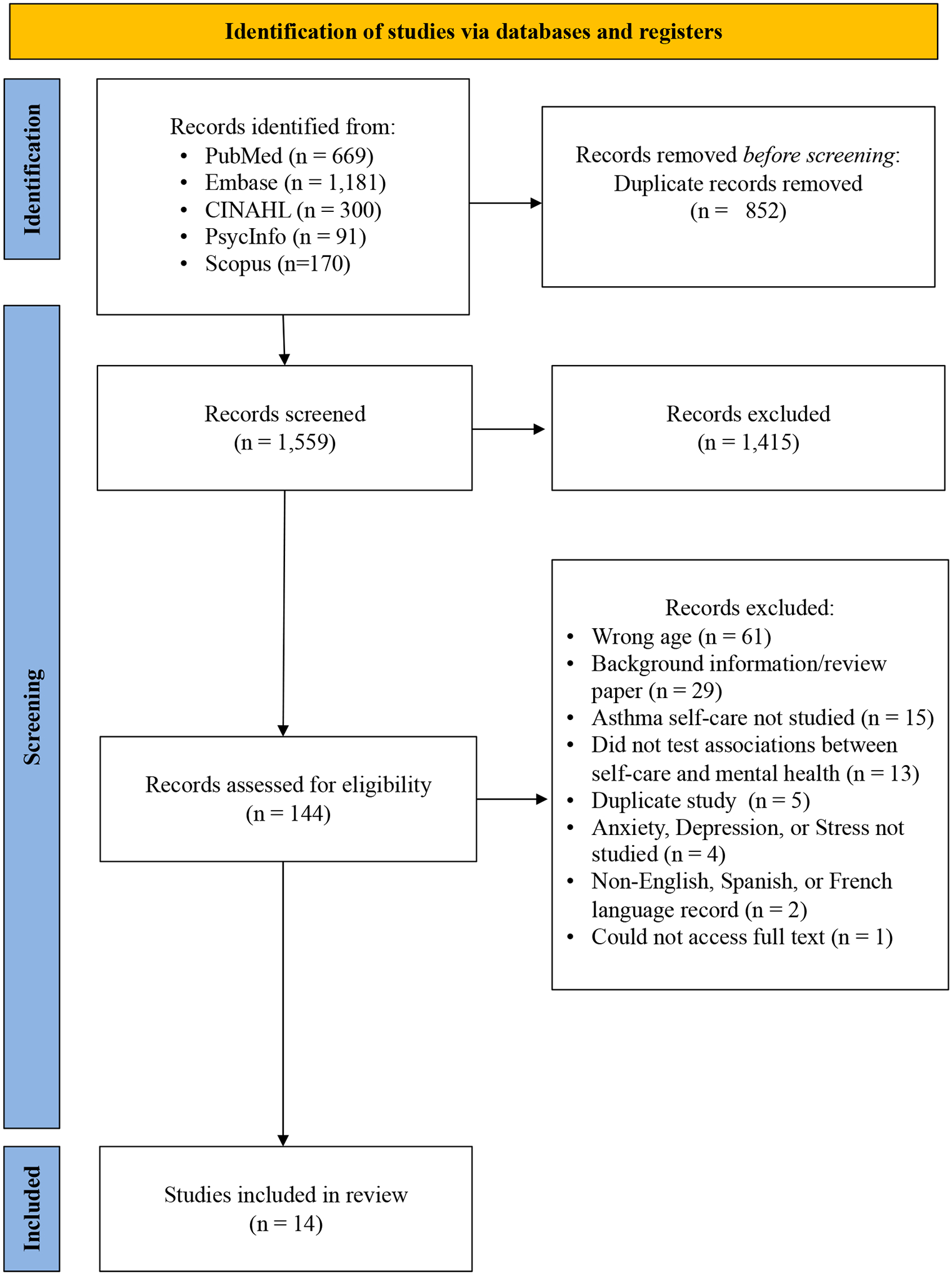

Each title and abstract was independently screened for inclusion by two independent reviewers. Disagreements were discussed and a consensus decision was made to include or exclude the record. Next, two reviewers independently reviewed the full text of the remaining records. Any disagreements were discussed, and a consensus decision was made whether to include or exclude the record. The PRISMA-ScR flow diagram26 summarizes the screening process (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study inclusion process

3.4. Data Extraction

The data extraction form was designed in Covidence. The data extraction fields included: first author, publication year, country, funding sources, study design, sample size, study inclusion and exclusion criteria, ages, race and ethnicity, sex, how asthma severity was diagnosed or assessed, characteristics of asthma control and severity, mental health characteristics, socioeconomic status, setting, whether anxiety or anxiety symptoms were measured, whether depression or depressive symptoms were measured, whether stress was measured, what measures were used, types of self-management, how self-management was measured, key findings, and other relevant results. Two reviewers independently extracted each record. Both extraction forms were reviewed by the team and consensus decisions were made for the final extraction of each record.

4. Results

4.1. Study Identification

A combined total of 1,559 unique records were identified in the initial and re-run searches. There were 1,415 records excluded during title and abstract screening, leaving 144 records to assess for full text eligibility. There were 130 records excluded during full text screening (most common exclusion reasons included: wrong age [n=61], background information/review paper [n=29], and that asthma self-management was not studied [n=15]). A total of 14 records were included in the scoping review synthesis (Figure 1).

4.2. Study and Participant Characteristics

Table 1 displays characteristics of included studies and their samples. All included studies were published between 2007 and 2020. Twelve studies were quantitative (eight cross-sectional28–35 and four longitudinal36–39) and two were qualitative.40,41 Of the quantitative studies, two used the same dataset and reported on different outcomes.32,33 As such, we summarized them separately. Nine studies were conducted in the United States,28–31,34–36,38,39 two in Korea,32,33 two in the United Kingdom,40,41 and one in Italy.37 No studies focused only on rural adolescents. Seven focused only on urban adolescents,28,29,34–36,38,39 and the remainder either included both urban and rural participants30–33 (three of these used nationally representative samples30,32,33), or did not report rural/urban characteristics of their samples.37,40,41 Nine studies reported participant race and/or ethnicity,28–30,34,35,38–41 twelve studies reported participant sex,28–35,37–40 and eight studies reported some element of participant socioeconomic status.28,29,31–35,39

Table 1:

Characteristics of Selected Studies (n = 14)

| Author(s) (year) | Setting (country, rural/ urban/ both) | Study design | Sample Size (n with asthma if not whole sample) | Age (years) | Race and ethnicity (%) | Sex (% female) | Socioeconomic Status | Asthma severity or control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bender (2007)30 | USa Both |

Cross-sectional | 13,917 (720) | Range = 12–18 | Black (24%) Hispanic (15%) White (44%) |

52% | NR | 100% had an episode or attack in the past year |

| Bruzzese, Reigada et al. (2016)28 | US Urban |

Cross-sectional | 386 | Range = 11– 14 Mean = 13 |

African American, not Hispanic (34%) Biracial (9%) Hispanic (48%) Another (9%) |

45% | From schools where free/reduced lunch eligibility was approximately 76% | Mild (33%), moderate (33%), and severe (34%) persistentc |

| Bruzzese, Kingston et al. (2016)29 | US Urban |

Cross-sectional | 349 | Mean = 16 | African American/ Black (37%) Hispanic (46%) Multiracial (6%) Another (11%) |

83% | Adolescents on Medicaid (67%); From schools where free/reduced lunch eligibility was approximately 76% |

Moderate (53%) and severe (47%) persistentc |

| Bush et al. (2007)31 | US Both |

Cross-sectional | 769 | Mean = 14 | NR | 47% | Parents on Medicaid: 14% | Average 4 symptom days in past 2 weeks |

| Guglani et al. (2013)36 | US Urban |

Longitudinal (6 months) | 123 | NR | NRb | NRb | NRb | NR |

| Holley et al. (2018)40 | UK NR |

Qualitative | 28 | Range = 12 – 18 | White (89%) | 50% | NR | 75% had long-term controller prescription and 43% used a quick reliever >4 days/week |

| Kim et al. (2020)32 | Koreaa Both |

Cross-sectional | 195,847 (17,403) | NR | NR | 41% | Adolescent-reported subjective economic status: high: 39%; middle: 44%; low: 17% | NR |

| Kyung et al. (2020)33 | Koreaa Both |

Cross-sectional | 62,276 (5,422) | NR | NR | 42% | Adolescent-reported subjective economic status: high: 42%, middle: 43%, low: 15% | NR |

| Licari et al. (2020)37 | Italy NR |

Longitudinal (12 months) | 40 | Mean = 14 | NR | 45% | NR | 100% severe at baselined |

| Luberto et al. (2012)38 | US Urban |

Longitudinal (12 months) | 151 | Range = 12–19 Mean = 16 |

African American (85%) | 60% | NR | Intermittent (48%), mild (25%), moderate (24%), and severe persistent (3%)c |

| Mosnaim et al. (2014)34 | US Urban |

Cross-sectional | 93 | Range = 10–16 Mean = 13 |

Black/ African American (88%) Hispanic (11%) Another (11%) |

56% | Adolescents on public insurance (75%) Free/reduced lunch (84%) | 100% persistent, 84% uncontrolledc |

| Pateraki et al. (2018)41 | UK NR |

Qualitative | 11 | Range = 11–15 Mean = 13 |

White (100%) | NR | NR | Self-reported severity: mild (n=3), moderate (n=5), and severe (n=3) |

| Shankar et al. (2019)35 | US Urban |

Cross-sectional | 277 | Range = 12–16 Mean = 13 |

Black/ African American (54%) Hispanic (34%) |

44% | Adolescents on Medicaid (84%) | 100% persistent/ poorly controlled Some with moderate/ severe persistentc |

| Weekes et al. (2011)39 | US Urban |

Longitudinal (11–14 months) | 110 | Mean = 16 | Black (100%) | 60% | Adolescent insurance: public (67%), no insurance (17%), private insurance (13%) | Intermittent (50%), mild (24%), moderate (22%), and severe persistent (4%)c |

Note: Abbreviations: NR, Not reported; US, United States; UK, United Kingdom

Nationally representative sample

Characteristics of larger sample of 422 from which the 123 participants in this study were drawn provided by senior author: African American (96.7%), female 59.7%), Medicaid (53%)

Severity assessed based on National Heart Lung and Blood Institute criteria

Severity assessed based on Global Initiative for Asthma criteria

Eleven studies reported asthma severity or control. Seven of these used established guidelines: six,28,29,34,35,38,39 all conducted in the United States, used the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) guidelines,42 and one,37 conducted in Italy, used the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines.16 Of the remaining studies, four reported other markers of control such as frequency or recency of symptoms or use of long-term controller and quick reliever medications.30,31,40,41

Regarding mental health, eight studies measured anxiety symptoms,28,29,31,37–41 ten measured depressive symptoms,29–38 and three measured stress;29,32,33 six studies measured more than one of these.29,31–33,37,38 As detailed in Table 2, methods for measuring mental health varied across studies. Six of the studies that measured anxiety symptoms used self-report instruments with demonstrated validity,28,29,37–39,41 one study used a diagnostic interview,31 and the remaining study included participant discussion of anxiety symptoms during qualitative interviews.40 Symptoms of different types of anxiety were measured and analyzed in association with self-management. Symptoms of generalized anxiety were measured in five studies,29,37,39–41 panic in four,38,40,41 social anxiety in three,28,38,41 separation anxiety in three;28,38 one study measured multiple types of anxiety, but collapsed them into one measure of whether the participant had symptoms of any anxiety disorder.31 Two studies measured asthma-related anxiety.28,29 Among studies measuring depressive symptoms, six used instruments with demonstrated validity,29,34–38 one used a diagnostic interview,31 and three used single self-report items,30,32,33 two of which used the same dataset. Finally, among studies measuring stress, one used an instrument with demonstrated validity.29 The remaining two studies, which utilized the same dataset, used a single self-report item that was not validated.32,33

Table 2:

Key Findings

| Author(s) (year) | Type(s) of Mental Health Assessed and Measure(s) Used | Asthma Self-management | Associations between mental health and self-management, with regression coefficients or odds ratios where available | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention | Management | Description | |||

| Bender (2007)30 | Depressive symptoms: Self-report; single item Depressive symptoms: Self-report; single item |

✓ | Trigger control: Self-report cigarette and cannabis use. | Depressive symptoms: Depressive symptoms associated with higher cigarette (p<.001) and cannabis (p<.001) use in past 30 days. | |

| Bruzzese, Reigada et al. (2016)28 | Anxiety symptoms: Self-report; Screen for Anxiety and Emotional Disorders (social and separation anxiety subscales) and Youth Asthma-related Anxiety Scale | ✓ | ✓ | Overall self-management: Self-report indices assessing barriers, prevention and management behaviors. | Anxiety symptoms: Asthma-related anxiety symptoms associated with greater prevention (p<.001, curvilinear, df=2.4), management (Beta=0.03, p=.02), and responsibility (Beta=0.11, p=.02); separation anxiety associated with greater prevention (Beta=0.13, p=.02); social anxiety not significantly related with asthma self-management. |

| Bruzzese, Kingston et al. (2016)29 | Anxiety symptoms: Self-report; Screen for Anxiety and Emotional Disorders; Youth Asthma-related Anxiety Scale Depressive symptoms: Self-report; Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale Stress: Self-report; Perceived Stress Scale |

✓ | Healthcare adherence: Self-report seeing a provider for symptoms. | Anxiety symptoms: Asthma-related anxiety significantly associated with increased odds of seeing provider (OR=1.6, p<.01); generalized anxiety not significantly associated with seeing provider. Depressive symptoms: Depressive symptoms associated with higher odds of seeing provider (OR=1.0, p=.02). Stress: Stress not significantly associated with seeing provider. |

|

| Bush et al. (2007)31 | Anxiety: Diagnostic interview; Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (anxiety modules) Depression: Diagnostic interview; Computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (depression modules) |

✓ | Trigger control: Self-report cigarette use. | Anxiety: Anxiety associated with smoking (OR=2.6, p<.01). Depression: Depressive symptoms associated with smoking (OR=2.6, p<.01). |

|

| Guglani et al. (2013)36 | Depressive symptoms: Self-report; Diagnostic Predictive Scale | ✓ | Healthcare adherence: Self-report controller medication adherence. | Anxiety symptoms: No significant association at baseline. After 6 months those in treatment group with depressive symptoms at baseline showed greater improvement in medication adherence in response to the intervention (aOR=9.5, p=.02). | |

| Holley et al. (2018)40 | Anxiety symptoms: Adolescents discussed anxiety symptoms in qualitative interviews | ✓ | ✓ | Overall self-management: Adolescents discussed staying calm and managing symptoms. | Anxiety symptoms: Participants reported anxiety/panic exacerbated symptoms and was a barrier to asthma self-management. |

| Kim et al. (2020)32 | Depressive symptoms: Self-report; single item Stress: Self-report; single item |

✓ | Trigger control: Self-report cigarette and e-cigarette use. | Depressive symptoms: Depressive symptoms associated with use of cigarettes (aOR=1.4, p<.001) and e-cigarettes (aOR=1.4, p<.001). Stress: More frequent perceived stress associated with e-cigarette use (p<0.001). |

|

| Kyung et al. (2020)33 | Depressive symptoms: Self-report; single item Stress: Self-report; single item |

✓ | Healthcare adherence: Self-report whether received the influenza vaccine. | Depressive symptoms: Depressive symptoms associated with not receiving influenza vaccination (aOR=0.8; 95% CI 0.64–0.95). Stress: Perceived stress not significantly associated with influenza vaccination. |

|

| Licari et al. (2020)37 | Anxiety symptoms: Self-report; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Depressive symptoms: Self-report; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

✓ | Healthcare adherence: Quick reliever medication use (unclear if reported by adolescent or caregiver). | Anxiety symptoms: No significant association between anxiety symptoms and short-acting bronchodilator use on-demand at baseline (i.e., first clinic visit). After 12 months guideline-based treatment, short-acting bronchodilator use decreased in non-anxious group but not in anxious group (p=.03). | |

| Luberto et al. (2012)38 | Anxiety symptoms: Self-report; Multidimensional Scale of Anxiety for Children Depressive symptoms: Self-report; Children’s Depression Inventory |

✓ | Trigger control: Self-report use of stress management techniques | Anxiety symptoms: No significant associations between anxiety symptoms and stress reduction techniques. Depressive symptoms: Depressive symptoms significantly associated with less use of guided imagery at baseline (p=.02). |

|

| Mosnaim et al. (2014)34 | Depressive symptoms: Self-report; Children’s Depression Inventory 2 | ✓ | Healthcare adherence: Controller medication adherence, assessed objectively with electronic medication monitoring. | Depressive symptoms: No significant association between depressive symptoms and adherence. | |

| Pateraki et al. (2018)41 | Anxiety symptoms: Self-report; Screen for Child Anxiety Related Emotional Disorders | ✓ | ✓ | Healthcare adherence: Self-report prescribed medication adherence. | Anxiety symptoms: Participants reported anxiety symptoms are associated with medication non-adherence/misuse. |

| Shankar et al. (2019)35 | Depressive symptoms: Self-report; Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale | ✓ | Healthcare adherence: Caregivers reported the adolescent’s preventive care use and adolescents self-reported controller medication adherence. | Depressive symptoms: No significant association between depressive symptoms and healthcare use or medication adherence. | |

| Weekes et al. (2011)39 | Anxiety symptoms: Self-report; Multidimensional Scale of Anxiety for Children | ✓ | Trigger control: Self-report cigarette and cannabis use. | Anxiety symptoms: Less anxiety symptoms at baseline significantly associated with increased odds of cannabis use at follow-up (OR=0.9, p<.01). Anxiety not significantly associated with cigarette use. | |

Regarding asthma self-management, twelve studies measured symptom prevention,28,30–36,38–41 five measured symptom management,28,29,37,40,41 and three studies measured both symptom prevention and management.28,40,41 Our team operationalized symptom prevention as trigger control (i.e., use of inhaled substances30–32,39 and stress management techniques38) and preventive treatment adherence (i.e., adherence to long-term controller medication,34–36 receipt of the influenza vaccine,33 and preventive care use35). Our team defined symptom management as acute treatment adherence (i.e., seeing a medical provider for symptoms29 and use of short-acting bronchodilator medications37).

Methods for measuring self-management varied, with all but one study using subjective measures. Among the 12 quantitative studies, seven used self-report items which were not part of instruments.29,30,32,33,35,36,40 Four used self-report instruments,28,31,38,39 two of which had demonstrated validity.28,31 In the remaining quantitative studies, one assessed self-management objectively using electronic medication monitoring to measure medication adherence,34 and one assessed self-management via self-report in the context of a clinical examination but it was unclear if the adolescent or caregiver was the respondent.37 In one of the two qualitative studies, adolescents discussed their overall adherence to prescribed medications for asthma, without specification of whether they were long-term controller medications, short-acting bronchodilator medications, or both.41 In the other qualitative study, participants discussed strategies used to stay calm in order to effectively prevent and manage symptoms.40

4.3. Associations of mental health to asthma self-management

4.3.1. Anxiety

As can be seen in Table 2, associations between anxiety symptoms and asthma self-management varied across studies. In four studies, symptoms of anxiety were associated with poorer self-management.31,37,40,41 Adolescents with symptoms of any type of anxiety were significantly more likely to smoke cigarettes.31 Those with symptoms of generalized anxiety were significantly more likely to over-use short-acting bronchodilator medications,37 and adolescents reported their anxiety symptoms were a barrier to proper medication adherence41 and overall self-management.40 At the same time, however, three other studies found that symptoms of anxiety were associated with better asthma self-management.28,29,39 One of these found that asthma-related anxiety symptoms were associated with higher odds of seeing a provider for symptoms.29 Another found that asthma-related anxiety symptoms were associated with taking more responsibility for asthma self-management and taking more steps to manage symptoms, and had a curvilinear relationship with symptom prevention; low levels of anxiety symptoms were associated with fewer prevention efforts and moderate levels of anxiety symptoms were associated with improved prevention, but this relationship plateaued when anxiety symptoms became more severe.28 In this same study, separation anxiety symptoms were also associated with greater symptom prevention.28 A third study found symptoms of generalized anxiety were associated with less cannabis use.39 Finally, the remaining study measuring anxiety found no significant associations between anxiety symptoms and stress-management techniques.38

4.3.2. Depression

Among the studies measuring depressive symptoms, the majority found these symptoms were associated with poorer asthma self-management. In five studies, depressive symptoms were found to be associated with worse trigger control, including higher rates of cigarette,30–32 e-cigarette,32 and cannabis30 use, lower rates of flu shot uptake,33 and less use of stress management techniques.38 At the same time, two studies found depressive symptoms were associated with better self-management, including higher odds of seeing a provider for symptoms,29 and a better response to an intervention to improve controller medication adherence.36 The remaining two studies that measured depressive symptoms found no significant associations between these symptoms and asthma self-management.34,35 Table 2 displays these findings for each study.

4.3.3. Stress

Of the three studies assessing stress, only one had significant findings. It found that stress was associated with increased e-cigarette use.32 See Table 2 for findings from each study.

5. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first scoping review addressing associations between adolescent mental health and asthma self-management. Overall, we found mixed results, with some studies indicating mental health symptoms impede self-management and others that mental health symptoms may facilitate self-management. This might be due to differences in the types of mental health and self-management measured across the studies as well as inconsistency in methods used to assess these variables. Additionally, because most studies we included are cross-sectional, we cannot make conclusions about causality or temporality in the relationships between anxiety, depression, and stress, and asthma self-management. Thus, given the heterogeneity and predominantly cross-sectional nature of the included studies, our findings can be considered preliminary; few definitive conclusions can be made. This highlights the need for more research to increase understanding of mental health as potentially both a barrier and facilitator to adolescent asthma self-management.

5.1. Type of Mental Health

Associations between mental health symptoms and asthma self-management varied across types of mental health symptoms. With respect to anxiety, different types of anxiety appeared to be differentially associated with self-management. The two studies assessing asthma-related anxiety found that it might be associated with better self-management;28,29 one of these found a curvilinear association with improved symptom prevention such that moderate levels of anxiety were associated with the greatest engagement in symptom prevention behaviors.28 Moderate levels of asthma-related anxiety may facilitate self-management, perhaps because of increased vigilance about preventing asthma symptoms.28 Associations between symptoms of other types of anxiety and asthma self-management were less consistent, indicating a need for additional research. Symptoms of any type of anxiety were associated with increased inhaled substance use in one study,31 but generalized anxiety symptoms were associated with less inhaled substance use in another.39 Additionally, qualitative findings indicate adolescents felt that their symptoms of various types of anxiety played an important role in hindering their self-management.40,41 Future research can examine whether specific types of anxiety have consistent associations with asthma self-management, and whether other factors, such as adolescents’ confidence in their ability to care for their asthma (i.e., self-efficacy), play a role in these relationships.

Whereas associations between anxiety symptoms and self-management may depend on anxiety type, associations between depressive symptoms and self-management appear to vary by the type of self-management studied. Depressive symptoms were consistently associated with poorer trigger control (including more inhaled substance use30–32 and less use of stress management techniques38), but the three studies that analyzed associations between depressive symptoms and healthcare adherence had conflicting findings.29,33,36 Adolescents with depressive symptoms were less likely to get an influenza vaccine,33 but they were more likely to see a healthcare provider for asthma symptoms,29 and more likely to respond favorably to treatment aimed at improving medication adherence.36 Future research can further explore why depressive symptoms may be differentially associated with different types of asthma self-management.

Finally, only one of the three studies that examined stress found it to be significantly associated with self-management: increased stress was related to increased e-cigarette use.32 This is consistent with our findings that anxiety and depressive symptoms might also be associated with increased inhaled substance use. Additional research on associations between stress and asthma self-management among adolescents is needed to further elucidate this relationship. It is notable that only three studies measured stress, and that only one did so with an instrument with demonstrated validity.29 Given the known disproportionate burden and impact of stress, particularly chronic stress, on asthma outcomes among individuals in systemically oppressed demographic groups,18,19 more research is needed on stress and asthma self-management, including its possible role in asthma disparities.

Alternatively, the inconclusive results may have been due to the inconsistent methods used to measure mental health across studies. Although most studies used validated mental health measures (see Table 2), there was a wide variety of measures used. It is plausible that different measures assess slightly different aspects of a given mental helath construct, which in turn changes the associations. As such, the inconclusive results may be due to the type of measure used.

5.2. Type of self-management

We found patterns in associations between mental health and asthma self-management based on type of self-management. Mental health symptoms were nearly universally associated with poorer trigger control, including inhaled substance use. It is well established that inhaled substances are often used as self-medication by individuals experiencing mental health symptoms.43,44 Our findings suggest self-medication with inhaled substances may occur among adolescents with asthma and comorbid mental health symptoms, despite the fact that inhaled substances trigger asthma.16 While we are unable to ascertain directionality of associations due to the predominantly cross-sectional designs of studies included in our review, it is plausible that adolescents experience their mental health symptoms so intensely that their asthma becomes secondary to alleviating the mental health symptoms; concerns about triggering asthma symptoms may not be sufficient to keep them from using substances. With regard to trigger control through stress management, adolescents with depressive symptoms were less likely to engage in stress management practices,38 perhaps due to the low levels of energy and motivation which are characteristic of depression.45

We found varied associations between healthcare adherence, which we broadly defined as including preventive care as well as symptom management, and mental health. Adolescents with undiagnosed asthma who reported anxiety or depressive symptoms were more likely to see a healthcare provider for their asthma symptoms.29 This is consistent with existing research indicating mental health symptoms are associated with increased healthcare use, regardless of asthma or other diagnoses, perhaps due to a need for relief from symptoms of either the mental health or physical illness.29 Depressive symptoms were associated with decreased influenza vaccination rates.33 However, other factors, such as lack of knowledge regarding how influenza may worsen asthma symptoms, access to healthcare, and parent/guardian views on vaccinations could also impact the association with influenza vaccination. In particular, access to healthcare, a social determinant of health,46 may impact associations between mental health symptoms and healthcare adherence. Some groups of adolescents may have limited access to healthcare and thus may not only be unable to receive to recommended healthcare for their asthma, but may also be more likely to experience mental health symptoms.46 Thus, further research is needed to examine the role of social determinants of health in associations between mental health symptoms and healthcare adherence.

Another component of healthcare adherence assessed in this review was medication adherence. Qualitative findings revealed adolescents perceived anxiety symptoms as an important barrier to medication adherence.41 In longitudinal studies, anxiety symptoms were significantly associated with over-use of short-acting bronchodilators even after treatment,37 while depressive symptoms were associated with improved medication adherence after an intervention.36 In the first case, adolescents might have trouble differentiating between their asthma and anxiety symptoms because the symptoms overlap, leading to continued overuse of quick relievers even after intervention.37 In the second case the improved intervention response among those with depressive symptoms may occur because these adolescents are particularly desperate for relief and so adhere to the intervention.36 Overall, more research is needed to determine the impact of mental health symptoms on healthcare adherence in general, and medication adherence (including in response to interventions and treatment) in particular.

As with the variability in measures assessing mental health symptoms, it is also plausible that the inconsistent findings by type of self-management may be due to variability in the methods to assess self-management. Even more so than for mental health symptoms, the methods varied widely and, for the most part, were not validated instruments.

There were some limitations to this review. While we our search strategy was comprehensive including articles in the English, Spanish, and French language, as well as searching five databases, it is possible that relevant articles were studies were missed. Also, study findings can only be generalized to adolescents. Additionally, we chose to focus on three types of mental health (i.e., anxiety, depression, and stress) because of their known importance for adolescents with asthma. However, mental health encompasses symptoms and disorders beyond those that we analyzed; additional research is needed to determine how other types of mental health might be associated with adolescent asthma self-management. Finally, because most studies we included were cross-sectional, we cannot make conclusions about causality or temporality in the associations we analyzed.

6. Conclusion

Findings from this scoping review indicate that the existing literature on associations between mental health and asthma self-management among adolescents is highly limited, and thus our findings could be seen as preliminary. Anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, and stress may all be associated with asthma self-management, but the directions of these relationships appear to vary. They may differ depending on the type of mental health symptoms, the type of asthma self-management, and/or the methods used to assess these constructs. Additionally, associations might be impacted by additional factors such as knowledge about asthma self-management and healthcare access. Given that this age group is known to experience high rates of both mental health disorders and poorly controlled asthma, greater understanding of the role of mental health and asthma self-management is critical if health care providers are to improve asthma outcomes among adolescents. Thus, more research into the underlying mechanisms by which different mental health symptoms may impact asthma self-management is warranted. Future research to further define these relationships, particularly with a focus on social determinants of health and health disparities, could have important implications for interventions aiming to improve asthma self-management among adolescents experiencing mental health symptoms.

6.1. Relevance to Clinical Practice

Although results were inconsistent across some studies in our review, based on our overall findings that mental health plays a role in asthma self-management, we recommend that, consistent with clinical guidelines,16 healthcare providers screen for mental health symptoms that may be comorbid with asthma. If indicated, we also recommend healthcare providers make appropriate referrals to mental health services as a part of developing and monitoring an asthma treatment plan with adolescent patients. Mental health symptoms, if present, might impact the patients’ ability to effectively manage their asthma. In particular, if an adolescent patient is struggling to adhere to recommended measures to manage their asthma, we recommend that providers assess whether mental health symptoms are present and inhibiting effective self-management. Linking patients to appropriate mental health support may help to improve their self-management and, in turn, their asthma outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Mental health and asthma self-management associations have yet to be synthesized.

Mental health symptoms appeared to impact asthma self-management among adolescents.

There was variability in methods used to assess mental health and self-management.

Providers should screen for mental health symptoms among adolescents with asthma.

Funding source:

Drs. Bruzzese and MacDonell’s efforts on this study, as well as that of Ms. Powell, were supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01 HL136753, PI=Bruzzese and R01 HL133506, PI=MacDonell). The content of this manuscript is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data: Supplementary data to this article can be found online at ___________.

Conflict of Interest Statement

No the authors have any actual or perceived conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most recent national asthma data. https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_national_asthma_data.htm. Published 2019. Accessed 7/6/21, 2021.

- 2.Yaghoubi M, Adibi A, Safari A, FitzGerald JM, Sadatsafavi M. The projected economic and health burden of uncontrolled asthma in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(9):1102–1112. 10.1164/rccm.201901-0016OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zahran HS, Bailey CM, Damon SA, Garbe PL, Breysse PN. Vital signs: Asthma in children - United States, 2001–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5):149–155. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6705e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schneider T. Asthma and academic performance among children and youth in north america: A systematic review. J Sch Health. 2020;90(4):319–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulikova A, Lopez J, Antony A, et al. Multivariate association of child depression and anxiety with asthma outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(6):2399–2405. 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.02.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naeem A, Silveyra P. Sex differences in paediatric and adult asthma. Eur Med J (Chelmsf). 2019;4(2):27–35. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31328173. Published 2019/07/23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson PD, Jayasuriya G, Haggie S, Uluer AZ, Gaffin JM, Fleming L. Issues affecting young people with asthma through the transition period to adult care. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2021. 10.1016/j.prrv.2021.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dudeney J, Sharpe L, Jaffe A, Jones EB, Hunt C. Anxiety in youth with asthma: A meta-analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52(9):1121–1129. 10.1002/ppul.23689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bardach NS, Neel C, Kleinman LC, et al. Depression, anxiety, and emergency department use for asthma. Pediatrics. 2019;144(4):e20190856. 10.1542/peds.2019-0856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goodwin RD. Toward improving our understanding of the link between mental health, lung function, and asthma diagnosis. The challenge of asthma measurement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;194(11):1313–1315. 10.1164/rccm.201610-2016ED [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Letitre SL, de Groot EP, Draaisma E, Brand PL. Anxiety, depression and self-esteem in children with well-controlled asthma: Case-control study. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(8):744–748. 10.1136/archdischild-2013-305396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fidler A, Lawless C, LaFave E, et al. Anxiety among adolescents with asthma: Relationships with asthma control and sleep quality. Clin Pract Pediatr Psychol. 2019;7(2):151–156. 10.1037/cpp0000267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cobham VE, Hickling A, Kimball H, Thomas HJ, Scott JG, Middeldorp CM. Systematic review: Anxiety in children and adolescents with chronic medical conditions. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(5):595–618. 10.1016/j.jaac.2019.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tibosch MM, Verhaak CM, Merkus PJ. Psychological characteristics associated with the onset and course of asthma in children and adolescents: A systematic review of longitudinal effects. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(1):11–19. 10.1016/j.pec.2010.03.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCauley E, Katon W, Russo J, Richardson L, Lozano P. Impact of anxiety and depression on functional impairment in adolescents with asthma. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2007;29(3):214–222. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2007.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. https://ginasthma.org. Published 2022. Accessed.

- 17.Yonas MA, Lange NE, Celedon JC. Psychosocial stress and asthma morbidity. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12(2):202–210. 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32835090c9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landeo-Gutierrez J, Celedon JC. Chronic stress and asthma in adolescents. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;125(4):393–398. 10.1016/j.anai.2020.07.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg SL, Miller GE, Brehm JM, Celedon JC. Stress and asthma: Novel insights on genetic, epigenetic, and immunologic mechanisms. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(5):1009–1015. 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mammen J, Rhee H. Adolescent asthma self-management: A concept analysis and operational definition. Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 2012;25(4):180–189. 10.1089/ped.2012.0150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riegel B, Dunbar SB, Fitzsimons D, et al. Self-care research: Where are we now? Where are we going? Int J Nurs Stud. 2021;116:103402. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Denford S, Taylor RS, Campbell JL, Greaves CJ. Effective behavior change techniques in asthma self-care interventions: Systematic review and meta-regression. Health Psychol. 2014;33(7):577–587. 10.1037/a0033080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters M, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Trico A, Khalil H. Chapter 11: Scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawyer SM, Azzopardi PS, Wickremarathne D, Patton GC. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2018;2(3):223–228. 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruzzese JM, Reigada LC, Lamm A, et al. Association of youth and caregiver anxiety and asthma care among urban young adolescents. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(8):792–798. 10.1016/j.acap.2016.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bruzzese JM, Kingston S, Zhao Y, DiMeglio JS, Cespedes A, George M. Psychological factors influencing the decision of urban adolescents with undiagnosed asthma to obtain medical care. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(5):543–548. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bender BG. Depression symptoms and substance abuse in adolescents with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;99(4):319–324. 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60547-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bush T, Richardson L, Katon W, et al. Anxiety and depressive disorders are associated with smoking in adolescents with asthma. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(5):425–432. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.11.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim CW, Jeong SC, Kim JY, et al. Associated factors for depression, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt among asthmatic adolescents with experience of electronic cigarette use. Tob Induc Dis. 2020;18:85. 10.18332/tid/127524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kyung Y, Choi MH, Lee JS, Lee JH, Jo SH, Kim SH. Influencing factors for influenza vaccination among south korean adolescents with asthma based on a nationwide cross-sectional study. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2020;181(6):434–445. 10.1159/000506336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mosnaim G, Li H, Martin M, et al. Factors associated with levels of adherence to inhaled corticosteroids in minority adolescents with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112(2):116–120. 10.1016/j.anai.2013.11.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shankar M, Fagnano M, Blaakman SW, Rhee H, Halterman JS. Depressive symptoms among urban adolescents with asthma: A focus for providers. Acad Pediatr. 2019;19(6):608–614. 10.1016/j.acap.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guglani L, Havstad SL, Ownby DR, et al. Exploring the impact of elevated depressive symptoms on the ability of a tailored asthma intervention to improve medication adherence among urban adolescents with asthma. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2013;9(1):45. 10.1186/1710-1492-9-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Licari A, Ciprandi R, Marseglia G, Ciprandi G. Anxiety in adolescents with severe asthma and response to treatment. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(4):e2020186. 10.23750/abm.v91i4.8806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luberto CM, Yi MS, Tsevat J, Leonard AC, Cotton S. Complementary and alternative medicine use and psychosocial outcomes among urban adolescents with asthma. J Asthma. 2012;49(4):409–415. 10.3109/02770903.2012.672612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weekes JC, Cotton S, McGrady ME. Predictors of substance use among black urban adolescents with asthma: A longitudinal assessment. J Natl Med Assoc. 2011;103(5):392–398. 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30335-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holley S, Walker D, Knibb R, et al. Barriers and facilitators to self-management of asthma in adolescents: An interview study to inform development of a novel intervention. Clin Exp Allergy. 2018;48(8):944–956. 10.1111/cea.13141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pateraki E, Vance Y, Morris PG. The interaction between asthma and anxiety: An interpretative phenomenological analysis of young people’s experiences. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2018;25(1):20–31. 10.1007/s10880-017-9528-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Expert panel report 3: Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. National Institutes of Health; 28 August 2007. 07–4051. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Turner S, Mota N, Bolton J, Sareen J. Self-medication with alcohol or drugs for mood and anxiety disorders: A narrative review of the epidemiological literature. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(9):851–860. 10.1002/da.22771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis of substance use disorders: A reconsideration and recent applications. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1997;4(5):231–244. 10.3109/10673229709030550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rice F, Riglin L, Lomax T, et al. Adolescent and adult differences in major depression symptom profiles. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:175–181. 10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grant T, Croce E, Matsui EC. Asthma and the social determinants of health. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;128(1):5–11. 10.1016/j.anai.2021.10.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.