Abstract

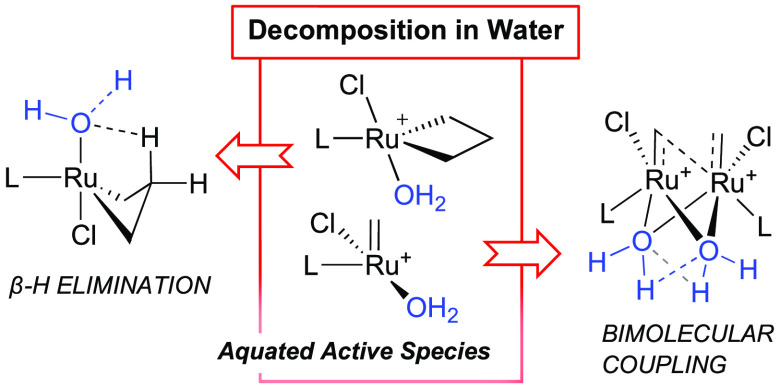

Water is ubiquitous in olefin metathesis, at levels ranging from contaminant to cosolvent. It is also non-benign. Water-promoted catalyst decomposition competes with metathesis, even for “robust” ruthenium catalysts. Metathesis is hence typically noncatalytic for demanding reactions in water-rich environments (e.g., chemical biology), a challenge as the Ru decomposition products promote unwanted reactions such as DNA degradation. To date, only the first step of the decomposition cascade is understood: catalyst aquation. Here we demonstrate that the aqua species dramatically accelerate both β-elimination of the metallacyclobutane intermediate and bimolecular decomposition of four-coordinate [RuCl(H2O)n(L)(=CHR)]Cl. Decomposition can be inhibited by blocking aquation and β-elimination.

Keywords: olefin metathesis, bimolecular decomposition, β-hydride elimination, ruthenium, aqueous metathesis, chemical biology

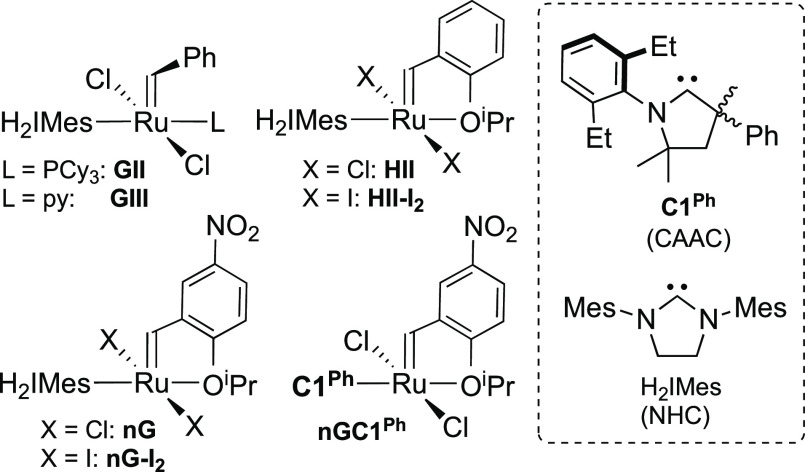

Olefin metathesis is an exceptionally versatile catalytic means of forging carbon–carbon bonds,1,2 with frontier applications spanning pharmaceutical manufacturing,3 materials science,4 and chemical biology.5,6 Water is ubiquitous in all of these contexts, at levels ranging from contaminant to cosolvent. This is important because water is now known to limit metathesis productivity even for relatively robust ruthenium catalysts (Chart 1). For demanding reactions in water-rich media (e.g., protein modification via cross-metathesis (CM)6 or assembly of DNA-encoded libraries (DEL) via ring-closing metathesis5c,5e (RCM)), the ruthenium complex must be used in significant stoichiometric excess, in part due to water-induced decomposition. Catalysis has been achieved only where the ruthenium complex is shielded in a lipophilic region.5a,5b,5d Catalytic metathesis is desirable not merely for efficiency: in certain chemical biology applications (DEL being a prominent recent example), it is critical, because the spent catalyst triggers DNA degradation.5c More broadly, understanding how water promotes decomposition of ruthenium metathesis catalysts is critical to expand opportunities in these and other forefront applications, in which water is either necessarily present or impractical to remove.

Chart 1. Olefin Metathesis Catalysts Discussed.a.

a GIII is a mono-/bis-pyridine mixture; for convenience, only the former is shown.7

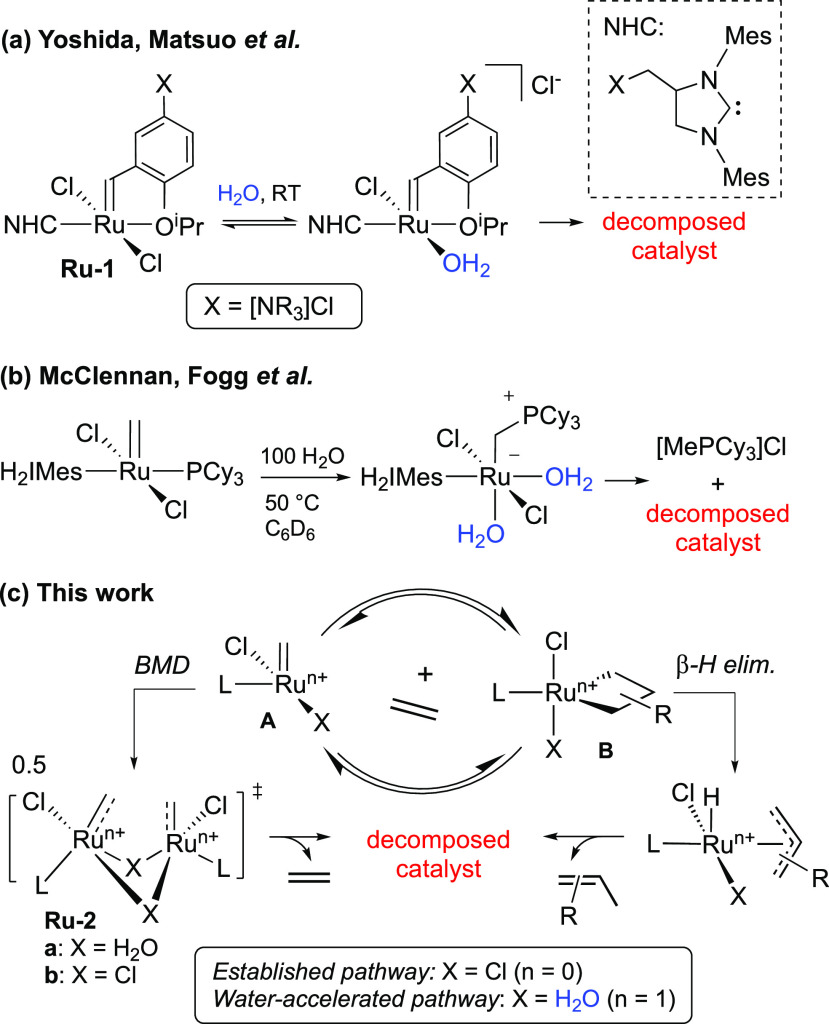

Metathesis in water has been described as a race against decomposition.6c Productivity is low and declines as the proportion of water increases. For example, a record turnover number (TON) of 640 was reported for a ruthenium-cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbene (CAAC) catalyst for metathesis in 1:1 H2O-MeOH: in neat water, TONs dropped to 200.8 In stark contrast, TONs up to 350 000 have been achieved in anhydrous solvent.9 For Ru-H2IMes catalysts, TONs for (R)CM in water are <100.10,11 The O’Reilly and Matsuo teams drew the logical inference that the ruthenium species present in aqueous solution are both less active and less stable.12,13 Decomposition of Ru-1 (Scheme 1a) or GIII was shown to commence with formation of an aqua complex (observed by UV-vis analysis at high water concentrations), with the ensuing pathways remaining speculative. Scheme 1a depicts the initial equilibrium (a classic aquation-anation exchange, where anation signifies replacement of bound water by the chloride counteranion).14 Consistent with decomposition via an aqua species,15 metathesis activity was restored by addition of chloride salts routinely used to shift the aquation equilibrium in biological media.16

Scheme 1. (a) Aquation-Initiated Catalyst Decomposition in Bulk Water. (b) Donor-Accelerated Decomposition of GII. (c) Water-Accelerated Degradation of Phosphine-Free Catalysts (Proposed).

The challenges associated with metathesis in the presence of trace water (important for both bench-scale17 and process3 chemistry) have been viewed as an independent problem. Metathesis productivity is severely degraded even at low concentrations of water, including the micromolar limits encountered in water-immiscible aromatic solvents (standard media for metathesis).18−22 It is unclear, however, whether aquation is relevant. The sole class of metathesis catalysts subjected to mechanistic study under such conditions are phosphine-stabilized Grubbs complexes, such as GII. Quantitative elimination of [MePCy3]Cl from GII in benzene-water supports an alternative mechanism, “donor-accelerated decomposition” (Scheme 1b).23 That is, coordination of water accelerates loss of PCy3, which then abstracts the methylidene ligand as [MePCy3]Cl.

Methylidene abstraction, however, is driven by the powerful nucleophilicity of PCy3.24 This mechanism is irrelevant to the decomposition of phosphine-free catalysts such as HII, but the latter are no less vulnerable than GII in “wet” aromatic solvents19−21 (indeed, fast-initiating variants are significantly more so).19 We therefore set out to clarify the pathways by which water degrades phosphine-free catalysts, with an explicit focus on the mechanism operative at low proportions of water. We considered two limiting possibilities: (1) that decomposition would proceed via aquation as in Scheme 1a, at a slower rate (in which case identification of post-aquation deactivation steps would be relevant to decomposition by both bulk and trace water) or (2) that aquation would be too slow to contribute, enabling an alternative pathway to take over. Here we report evidence for aquation even at millimolar concentrations of water and present the first insights into the ensuing decomposition pathways. Water is shown to accelerate two pathways operative in anhydrous media: bimolecular decomposition (BMD) of methylidene species A and β-H elimination of the metallacyclobutane intermediate B (Scheme 1c).

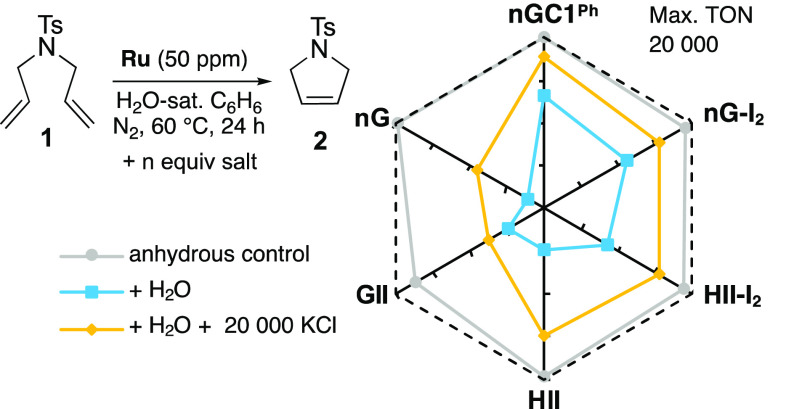

We began by examining whether decomposition follows a different mechanism in water-saturated benzene18 or if the pathway established in bulk water remains relevant. Building on the premise that decomposition commences with aquation and that added chloride salts inhibit this equilibrium reaction,15 we examined metathesis productivity in benzene-water and the extent to which it is mitigated by added chloride ion. If aquation does not contribute to decomposition, we reasoned that TONs should be unaffected. As substrate, we chose N-tosyl diallylamine 1, the facile cyclization of which permits low catalyst loadings (50 ppm = 0.005 mol %; 5 μM Ru), hence providing an aggressive test of the impact of water.

The radar plots of Figure 1 give a straightforward visual comparison of the impact of water and chloride salt. The outermost (dashed) line indicates the maximum attainable TON of 20 000; deviations toward the center signify lower productivity. While RCM is near-quantitative for all catalysts but GII in dry benzene (gray line), TONs drop significantly in the presence of water (blue line). Maximum negative impact was seen for nG and HII,25 and least for the iodide and CAAC catalysts, consistent with our prior report.19 Addition of KCl had a beneficial impact in all cases (in the case of HII, TONs are tripled), but in no case is activity completely restored to anhydrous levels. This is unsurprising, given restrictions on partitioning of KCl into the organic phase. Clearly, however, the positive effect of chloride established in bulk water is maintained at the lower proportions of water examined herein. These data point toward aquation as an important initial step in water-induced degradation even when the catalyst is confined to the organic phase.

Figure 1.

Effect of KCl on catalyst productivity28 in oxygen-free, water-saturated benzene with efficient volatilization of ethylene (see Supporting Information (SI)). Numerical values appear in Table S1; ±2 in replicate runs. Addition of NnBu4Cl was less effective: see Figure S1.

The increase for nGC1Ph holds more specific mechanistic significance. Whereas Ru-NHC catalysts undergo both decomposition pathways shown in Scheme 1c, an exceptional feature of the CAAC catalysts is their immunity to β-H elimination, but not bimolecular coupling. The higher productivity of nGC1Ph in the presence of added KCl thus implies that water-promoted BMD proceeds via an aqua complex. Also noteworthy is the resistance of the iodide complexes to decomposition by water. This may reflect the greater covalency of the Ru–iodide bond, which has been found to inhibit aquation in other contexts.26 The improved performance declines over time, however, owing to competing halide exchange with KCl.27

We previously suggested19 that the deleterious effects of water in metathesis primarily involve the active species, as also established in decomposition by nucleophiles and Bronsted base.29−31 Countering this hypothesis is the reported decomposition of the precatalysts Ru-1 and GIII in bulk water, as noted above. To resolve the discrepancy, we examined the stability of a series of precatalysts in anhydrous and “wet” benzene. In these experiments, the Ru complexes were stirred at 60 °C without substrate: decreases in the intensity of the benzylidene signal vs internal standard (IS) were monitored for 48 h or until decomposition was complete.

Py-stabilized GIII was completely decomposed after 4 h in water-saturated benzene, as compared to just 9% in the anhydrous control reaction (Table 1, entries 1, 2). Indeed, in the absence of water, 25% GIII remains even after 5 days at 60 °C.7 Water has less impact on GII (entry 3), consistent with the low lability of PCy3.32 For both GIII and GII, however, quantitative elimination of stilbene (Figure S6) offers unequivocal evidence that water degrades these complexes by accelerating bimolecular decomposition.7,33 (Nucleophilic attack of PCy3 on the substituted alkylidene carbon is not observed, in contrast with the facile abstraction of methylidene ligands shown in Scheme 1b.23) Equilibrium binding of water to form a spectroscopically unobservable,34 organic-soluble aqua complex is proposed to accelerate dimerization via intermolecular H-bonding (see Ru-2a, Scheme 1c).35 The chloride-bridged dimer Ru-2b was identified in computational studies of anhydrous BMD.7

Table 1. H2O-Induced Degradation of Precatalysts.

| Entry | Catalyst | t (h) | % [Ru]=CHAra,b | % Stilbeneb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | GIII | 2 | 34 (96) | 66 (4) |

| 2 | GIII | 4 | 0 (91) | 100 (9) |

| 3 | GII | 4 | 54 (100) | 46 (100) |

| 4 | GII | 24 | 0 (100) | 100 (0) |

| 5 | nG | 48 | >98 (>98) | 0 (0) |

| 6 | HII | 48 | >98 (>98) | 0 (0) |

| 7 | HII–I2 | 48 | >98 (>98) | 0 (0) |

| 8 | nG-I2 | 48 | >98 (>98) | 0 (0) |

| 9 | nGC1Ph | 48 | >98 (>98) | 0 (0) |

[Ru] = RuX2(L); L = H2IMes or C1Ph; X = Cl or I.

In brackets: anhydrous control. ±2% in replicate runs.

Neither HII nor nG underwent degradation after 2 days at 60 °C (entries 5, 6). In contrast, the water-soluble HII analogue Ru-1 is reported to be completely decomposed after 16 h at RT in neat H2O (Scheme 1a).12 We attribute the difference to the high concentrations of Ru and water under the literature conditions and a resulting shift of the aquation-anation equilibrium to the right.

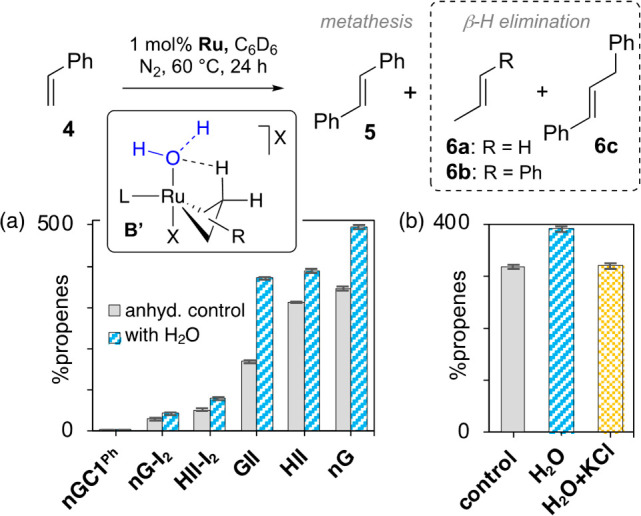

Bimolecular coupling is extremely sensitive to steric bulk.7,33 Given that water dramatically accelerates coupling of the benzylidene precatalysts GII and GIII, we anticipated that BMD would be the primary vector for catalyst decomposition in metathesis of terminal olefins in benzene-water, a reaction manifold propagated by methylidene species A (Scheme 1c, left). Unexpectedly, however, the rate of decomposition does not show a squared dependence on [Ru]; rather, it lies between first and second order (Figure S3). We thus questioned whether water also promotes a second major decomposition pathway intrinsic to the majority of olefin metathesis catalysts: β-H elimination of the metallacyclobutane B (Scheme 1c, right).36 To assess the impact of water on the latter pathway, we quantified the propenes eliminated during self-metathesis of styrene (Figure 2). Styrene is an invaluable substrate for this purpose because—unlike other 1-alkenes—it cannot isomerize to generate “false” propene markers.7 Propene yields were assessed by quantitative 1H NMR analysis at 24 h,37 to ensure full catalyst decomposition.

Figure 2.

Impacts of H2O or KCl on β-H elimination from the putative aqua complex B′ (X = Cl, I). (a) Acceleration by H2O. (b) Inhibition by KCl; shown for HII. For tabulated data, see SI. All reactions were carried out under oxygen-free conditions, with efficient removal of ethylene.

No propenes (6a−c, Figure 2a) were detected for the CAAC catalyst nGC1Ph in these experiments. In earlier studies conducted under anhydrous conditions, we reported that the CAAC catalysts, exceptionally, resist β-H elimination,38 because the high trans-influence of the carbene destabilizes the transition state for decomposition.39 The absence of propenes for nGC1Ph indicates that water is unable to overcome this resistance. In contrast, the yields of 6a–c for the NHC catalysts increase in the presence of water, as indicated by the other data in Figure 2a. Hydrogen-bonding interactions between bound water and Hβ (see B′) are proposed to aid in the H-transfer step. The effect is greatest for HII and nG, which spend the most time in the active cycle. The inhibiting effect of added chloride on production of propenes (shown for HII in Figure 2b) is consistent with the involvement of an aqua species in the transition state for β-H elimination.

Among the NHC complexes, the bis-iodide catalysts (nG-I2, HII-I2) underwent the least water-promoted β-H elimination, as anticipated from their relative water-tolerance.19,40,41 This heightened stability may reflect the resistance of the Ru–I bond to aquation, as discussed above.42 Also of note are changes in the distribution of propene products in the presence of water. Higher yields of substituted 6b/c vs 6a (approximately double; Figure S2) could plausibly be due to faster reductive elimination from B′, owing to increased steric pressure by the iodide ligands on the substituted metallacyclobutane.

An unexpected feature of these experiments is the superstoichiometric yield of propenes with respect to the initial catalyst charge. We infer regeneration of active catalyst from decomposed ruthenium species. In situ installation of an alkylidene ligand—standard practice in ROMP prior to development of “well-defined” metathesis catalysts43,44—has recently been demonstrated for simple 1-olefins.45 This observation holds considerable interest for the goal of recycling spent catalyst into the active cycle.45,46 Nevertheless, the key point in the present context is the increase in propene yields in the presence of water, signifying enhanced β-H elimination.

Water has long presented an under-recognized challenge to metathesis reactions. Expanding interest in applications where water is inevitable has turned a spotlight on ruthenium–water interactions and their role in catalyst decomposition. In bulk water, chloride ion improves the productivity of Ru metathesis catalysts by reversing aquation. The foregoing establishes that aquation occurs even at low water concentrations (i.e., the same mechanism is operative in bulk and trace water) and offers the first insights into the ensuing decomposition cascade. The water ligand greatly accelerates two decomposition pathways operative even in anhydrous media: bimolecular decomposition of the methylidene intermediate and β-H elimination of the metallacyclobutane.47 Recent discoveries that teach how to curb these pathways hence open the door to catalytic metathesis for demanding reactions in water. A high trans-influence ligand remains the key to inhibiting β-elimination; classic anchoring strategies, or aquation-resistant ligands, will aid further. These insights are anticipated to create major new opportunities in chemical biology and other contexts where water is essential.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Research Council of Norway (RCN project 288135) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC). We thank Apeiron Synthesis for gifts of nGC1Ph and nG-I2.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acscatal.2c05573.

Experimental and computational details; NMR spectra (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Grela K.Olefin Metathesis-Theory and Practice; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2014. [Google Scholar]; b Grubbs R. H., Wenzel A. G., O’Leary D. J., Khosravi E., Eds.; Handbook of Metathesis, 2nd ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- a Cossy J.; Arseniyadis S.; Meyer C.. Metathesis in Natural Product Synthesis: Strategies, Substrates and Catalysts; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2010. [Google Scholar]; b Fürstner A. Metathesis in Total Synthesis. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 6505–6511. 10.1039/c1cc10464k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Tyagi M.; Begnini F.; Poongavanam V.; Doak B. C.; Kihlberg J. Fabio; Poongavanam, Vasanthanathan, Drug Syntheses Beyond the Rule of 5. Chem. – Eur. J. 2020, 26, 49–88. 10.1002/chem.201902716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Fürstner A. Catalysis for Total Synthesis: A Personal Account. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 8587–8598. 10.1002/anie.201402719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Higman C. S.; Lummiss J. A. M.; Fogg D. E. Olefin Metathesis at the Dawn of Uptake in Pharmaceutical and Specialty Chemicals Manufacturing. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3552–3565. 10.1002/anie.201506846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Yu M.; Lou S.; Gonzalez-Bobes F. Ring-Closing Metathesis in Pharmaceutical Development: Fundamentals, Applications, and Future Directions. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2018, 22, 918–946. 10.1021/acs.oprd.8b00093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Farina V.; Horváth A.. Ring-Closing Metathesis in the Large-Scale Synthesis of Pharmaceuticals. In Handbook of Metathesis; Grubbs R. H., Wenzel A. G., O’Leary D. J., Khosravi E., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2015; Vol. 2, pp 633–658. [Google Scholar]

- For selected recent advances in ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP), see:; a Berger O.; Battistella C.; Chen Y.; Oktawiec J.; Siwicka Z. E.; Tullman-Ercek D.; Wang M.; Gianneschi N. C. Mussel Adhesive-Inspired Proteomimetic Polymer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 4383–4392. 10.1021/jacs.1c10936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Rizzo A.; Peterson G. I.; Bhaumik A.; Kang C.; Choi T.-L.. Sugar-Based Polymers from d-Xylose: Living Cascade Polymerization, Tunable Degradation, and Small Molecule Release. Angew. Chem. 2021, 133, 862–868 10.1002/ange.202012544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Arkinstall L. A.; Husband J. T.; Wilks T. R.; Foster J. C.; O’Reilly R. K. DNA–polymer conjugates via the graft-through polymerisation of native DNA in water. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 5466–5469. 10.1039/D0CC08008J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sathe D.; Zhou J.; Chen H.; Su H.-W.; Xie W.; Hsu T.-G.; Schrage B. R.; Smith T.; Ziegler C. J.; Wang J. Olefin metathesis-based chemically recyclable polymers enabled by fused-ring monomers. Nat. Chem. 2021, 13, 743–750. 10.1038/s41557-021-00748-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Yamauchi Y.; Horimoto N. N.; Yamada K.; Matsushita Y.; Takeuchi M.; Ishida Y. Two-Step Divergent Synthesis of Monodisperse and Ultra-Long Bottlebrush Polymers from an Easily Purifiable ROMP Monomer. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 1528–1534. 10.1002/anie.202009759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Feist J. D.; Xia Y. Enol Ethers Are Effective Monomers for Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization: Synthesis of Degradable and Depolymerizable Poly(2,3-dihydrofuran). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 1186–1189. 10.1021/jacs.9b11834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Sui X. L.; Zhang T. Q.; Pabarue A. B.; Fu L. B.; Gutekunst W. R. Alternating Cascade Metathesis Polymerization of Enynes and Cyclic Enol Ethers with Active Ruthenium Fischer Carbenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 12942–12947. 10.1021/jacs.0c06045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Song J.-A.; Peterson G. I.; Bang K.-T.; Ahmed T. S.; Sung J.-C.; Grubbs R. H.; Choi T.-L. Ru-Catalyzed, cis-Selective Living Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization of Various Monomers, Including a Dendronized Macromonomer, and Implications to Enhanced Shear Stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 10438–10445. 10.1021/jacs.0c02785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Church D. C.; Pokorski J. K. Cell Engineering with Functional Poly(oxanorbornene) Block Copolymers. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 11379–11383. 10.1002/anie.202005148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Hsu T. W.; Kim C.; Michaudel Q. Stereoretentive Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization to Access All-cis Poly(p-phenylenevinylene)s with Living Characteristics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 11983–11987. 10.1021/jacs.0c04068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Jung K.; Ahmed T. S.; Lee J.; Sung J. C.; Keum H.; Grubbs R. H.; Choi T. L. Living beta-selective cyclopolymerization using Ru dithiolate catalysts. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 8955–8963. 10.1039/C9SC01326A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selected recent examples of metathesis in chemical biology, see:; a Schunck N. S.; Mecking S. In vivo Olefin Metathesis in Microalgae Upgrades Lipids to Building Blocks for Polymers and Chemicals. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202211285. 10.1002/anie.202211285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Fischer S.; Ward T. R.; Liang A. D. Engineering a Metathesis-Catalyzing Artificial Metalloenzyme Based on HaloTag. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 6343–6347. 10.1021/acscatal.1c01470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Monty O. B. C.; Nyshadham P.; Bohren K. M.; Palaniappan M.; Matzuk M. M.; Young D. W.; Simmons N. Homogeneous and Functional Group Tolerant Ring-Closing Metathesis for DNA-Encoded Chemical Libraries. ACS Comb. Sci. 2020, 22, 80–88. 10.1021/acscombsci.9b00199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sauer D. F.; Bocola M.; Broglia C.; Arlt M.; Zhu L.-L.; Brocker M.; Schwaneberg U.; Okuda J. Hybrid Ruthenium ROMP Catalysts Based on an Engineered Variant of β-Barrel Protein FhuA ΔCVFtev: Effect of Spacer Length. Chem.: Asian J. 2015, 10, 177–182. 10.1002/asia.201403005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Lu X.; Fan L.; Phelps C. B.; Davie C. P.; Donahue C. P. Ruthenium Promoted On-DNA Ring-Closing Metathesis and Cross-Metathesis. Bioconjugate Chem. 2017, 28, 1625–1629. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Bhushan B.; Lin Y. A.; Bak M.; Phanumartwiwath A.; Yang N.; Bilyard M. K.; Tanaka T.; Hudson K. L.; Lercher L.; Stegmann M.; Mohammed S.; Davis B. G. Genetic Incorporation of Olefin Cross-Metathesis Reaction Tags for Protein Modification. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 14599–14603. 10.1021/jacs.8b09433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Masuda S.; Tsuda S.; Yoshiya T. Ring-closing metathesis of unprotected peptides in water. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 9364–9367. 10.1039/C8OB02778A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Grison C. M.; Burslem G. M.; Miles J. A.; Pilsl L. K. A.; Yeo D. J.; Imani Z.; Warriner S. L.; Webb M. E.; Wilson A. J. Double Quick, Double Click Reversible Peptide ″Stapling″. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 5166–5171. 10.1039/C7SC01342F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Cromm P. M.; Spiegel J.; Kuchler P.; Dietrich L.; Kriegesmann J.; Wendt M.; Goody R. S.; Waldmann H.; Grossmann T. N. Protease-Resistant and Cell-Permeable Double-Stapled Peptides Targeting the Rab8a GTPase. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11, 2375–2382. 10.1021/acschembio.6b00386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For recent reviews of olefin metathesis in chemical biology, see:; a Matsuo T. Functionalization of Ruthenium Olefin-Metathesis Catalysts for Interdisciplinary Studies in Chemistry and Biology. Catalysts 2021, 11, 359. 10.3390/catal11030359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Messina M. S.; Maynard H. D. Modification of Proteins using Olefin Metathesis. Mater. Chem. Front. 2020, 4, 1040–1051. 10.1039/C9QM00494G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Isenegger P. G.; Davis B. G. Concepts of Catalysis in Site-Selective Protein Modifications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 8005–8013. 10.1021/jacs.8b13187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Sabatino V.; Ward T. R. Aqueous Olefin Metathesis: Recent Developments and Applications. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2019, 15, 445–468. 10.3762/bjoc.15.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Vinogradova E. V. Organometallic Chemical Biology: An Organometallic Approach to Bioconjugation. Pure Appl. Chem. 2017, 89, 1619–1640. 10.1515/pac-2017-0207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey G. A.; Foscato M.; Higman C. S.; Day C. S.; Jensen V. R.; Fogg D. E. Bimolecular Coupling as a Vector for Decomposition of Fast-Initiating Olefin Metathesis Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6931–6944. 10.1021/jacs.8b02709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagyházi M.; Turczel G.; Balla Á.; Szálas G.; Tóth I.; Gál G. T.; Petra B.; Anastas P. T.; Tuba R. Towards Sustainable Catalysis – Highly Efficient Olefin Metathesis in Protic Media Using Phase Labelled Cyclic Alkyl Amino Carbene (CAAC) Ruthenium Catalysts. ChemCatChem. 2020, 12, 1953–1957. 10.1002/cctc.201902258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marx V. M.; Sullivan A. H.; Melaimi M.; Virgil S. C.; Keitz B. K.; Weinberger D. S.; Bertrand G.; Grubbs R. H. Cyclic Alkyl Amino Carbene (CAAC) Ruthenium Complexes as Remarkably Active Catalysts for Ethenolysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 1919–1923. 10.1002/anie.201410797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For recent reviews of aqueous metathesis, see ref (6d) and:; a Levin E.; Ivry E.; Diesendruck C. E.; Lemcoff N. G. Water in N-Heterocyclic Carbene-Assisted Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 4607–4692. 10.1021/cr400640e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lipshutz B. H.; Ghorai S.. Olefin Metathesis in Water and Aqueous Media. In Olefin Metathesis – Theory and Practice; Grela K., Ed.; Wiley, 2014; pp 515–521. [Google Scholar]; c Grela K.; Gulajski L.; Skowerski K.. Alkene Metathesis in Water. In Metal-Catalyzed Reactions in Water; Dixneuf P. H., Cadierno V., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2013; pp 291–336. [Google Scholar]

- TONs of 10 000 in ROMP and 650 in RCM have been reported in aqueous media using “artificial metalloenzymes” or catalysts incorporated into proteins, which shield them from water. See refs (5b) and (5d)

- Matsuo T.; Yoshida T.; Fujii A.; Kawahara K.; Hirota S. Effect of Added Salt on Ring-Closing Metathesis Catalyzed by a Water-Soluble Hoveyda–Grubbs Type Complex To Form N-Containing Heterocycles in Aqueous Media. Organometallics 2013, 32, 5313–5319. 10.1021/om4005302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Foster J. C.; Grocott M. C.; Arkinstall L. A.; Varlas S.; Redding M. J.; Grayson S. M.; O’Reilly R. K. It is Better with Salt: Aqueous Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization at Neutral pH. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 13878–13885. 10.1021/jacs.0c05499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richens D. T. Ligand Substitution Reactions at Inorganic Centers. Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 1961–2002. 10.1021/cr030705u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For reports of improved metathesis productivity on addition of chloride, see refs (5c−5g), (12), (13), and:; a Church D. C.; Takiguchi L.; Pokorski J. K. Optimization of Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization (ROMP) under Physiologically Relevant Conditions. Polym. Chem. 2020, 11, 4492–4499. 10.1039/D0PY00716A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Zhu C.; Wu X.; Zenkina O.; Zamora M. T.; Moffat K.; Crudden C. M.; Cunningham M. F. Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization in Miniemulsion Using a TEGylated Ruthenium-Based Metathesis Catalyst. Macromolecules 2018, 51, 9088–9096. 10.1021/acs.macromol.8b02240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Lynn D. M.; Mohr B.; Grubbs R. H.; Henling L. M.; Day M. W. Water-Soluble Ruthenium Alkylidenes: Synthesis, Characterization, and Application to Olefin Metathesis Polymerization in Protic Solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 6601–6609. 10.1021/ja0003167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levina A.; Mitra A.; Lay P. A. Recent developments in ruthenium anticancer drugs. Metallomics 2009, 1, 458–470. 10.1039/b904071d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajetanowicz A.; Chwalba M.; Gawin A.; Tracz A.; Grela K. Non-Glovebox Ethenolysis of Ethyl Oleate and FAME at Larger Scale Utilizing a Cyclic (Alkyl)(Amino)Carbene Ruthenium Catalyst. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2020, 122, 1900263. 10.1002/ejlt.201900263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The limiting concentration of water in benzene at 25 °C is 724 ppm. See:; a Karlsson R. Solubility of Water in Benzene. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1973, 18, 290–292. 10.1021/je60058a006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; In toluene: 330 ppm. See:; b László K.; Demé B.; Czakkel O.; Geissler E. Incompatible Liquids in Confined Conditions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 23723–23727. 10.1021/jp506100e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; At 60 °C, the calculated water concentration is 2000 ppm (2% v/v). See:; c Yaws C. L.; Rane P.; Nigam V. Solubility of Water in Benzenes As a Function of Temperature. Chem. Eng. 2011, 118, 42–46. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C.; Sims J.; Nascimento D. L.; Goudreault A. Y.; Steinmann S. N.; Michel C.; Fogg D. E. The Impact of Water on Ru-Catalyzed Olefin Metathesis: Potent Deactivating Effects Even at Low Water Concentrations. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 893–899. 10.1021/acscatal.0c04279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongkind L. J.; Rahimi M.; Poole D.; Ton S. J.; Fogg D. E.; Reek J. N. H. Protection of Ruthenium Olefin Metathesis Catalysts by Encapsulation in a Self-assembled Resorcinarene Capsule. ChemCatChem. 2020, 12, 4019–4023. 10.1002/cctc.202000111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guidone S.; Songis O.; Nahra F.; Cazin C. S. J. Conducting Olefin Metathesis Reactions in Air: Breaking the Paradigm. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 2697–2701. 10.1021/acscatal.5b00197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Water concentrations as low as 0.01% by volume were shown to dramatically reduce RCM productivity. See: ref (19). The higher the proportion of water, the higher the catalyst loadings required, and the greater the problems created by spent catalyst

- McClennan W. L.; Rufh S. A.; Lummiss J. A. M.; Fogg D. E. A General Decomposition Pathway for Phosphine-Stabilized Metathesis Catalysts: Lewis Donors Accelerate Methylidene Abstraction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 14668–14677. 10.1021/jacs.6b08372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PCy3 is insufficiently basic to form [HPCy3]OH even in THF containing 5% water (for 31P{1H} NMR analysis, see SI). This precludes the possibility that water accelerates bimolecular coupling of GII by rapidly consuming PCy3. In contrast, complete and immediate conversion to [HPCy3]Cl is observed on adding HCl to PCy3

- In comparison, decomposition of HII occurs within hours at RT during metathesis in toluene-water mixtures (ref (20)), despite the much lower concentrations of water attainable (ca. 300 ppm at saturation in toluene at RT: ref (18b))

- Romero-Canelón I.; Salassa L.; Sadler P. J. The Contrasting Activity of Iodido versus Chlorido Ruthenium and Osmium Arene Azo- and Imino-pyridine Anticancer Complexes: Control of Cell Selectivity, Cross-Resistance, p53 Dependence, and Apoptosis Pathway. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 1291–1300. 10.1021/jm3017442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Competing halide exchange of the bis-iodide catalysts with KCl occurs on the timescale of catalysis. Thus, speciation experiments in which nG-I2 was stirred with 1000 equiv KCl in water-saturated benzene at 60 °C for 2 h revealed 29% of the mono-iodo species and 5% nG (see Figure S5)

- GIII is omitted from the RCM study, as it fails with terminal olefins even in the absence of water. This presumably arises from rapid bimolecular decomposition: see below

- Santos A. G.; Bailey G. A.; dos Santos E. N.; Fogg D. E. Overcoming Catalyst Decomposition in Acrylate Metathesis: Poly-phenol Resins as Enabling Agents for Phosphine-Stabilized Metathesis Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 3181–3189. 10.1021/acscatal.6b03557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey G. A.; Lummiss J. A. M.; Foscato M.; Occhipinti G.; McDonald R.; Jensen V. R.; Fogg D. E. Decomposition of Olefin Metathesis Catalysts by Brønsted Base: Metallacyclobutane Deprotonation as a Primary Deactivating Event. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 16446–16449. 10.1021/jacs.7b08578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento D. L.; Reim I.; Foscato M.; Jensen V. R.; Fogg D. E. Challenging Metathesis Catalysts with Nucleophiles and Bronsted Base: The Stability of State-of-the-Art Catalysts to Attack by Amines. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 11623–11633. 10.1021/acscatal.0c02760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanford M. S.; Love J. A.; Grubbs R. H. Mechanism and Activity of Ruthenium Olefin Metathesis Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 6543–6554. 10.1021/ja010624k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento D. L.; Foscato M.; Occhipinti G.; Jensen V. R.; Fogg D. E. Bimolecular Coupling in Olefin Metathesis: Correlating Structure and Decomposition for Leading and Emerging Ruthenium-Carbene Catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 11072–11079. 10.1021/jacs.1c04424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The 1H NMR spectrum shows no change in the chemical shift of the [Ru]=CHPh proton for GIII or GII in H2O-saturated C6D6, relative to dry C6D6. The peak width is also unaffected (ω1/2 = 1.55 Hz). Similarly, the UV-vis spectra show no impact on the wavelength of the maximum absorption band for GIII in the presence of 1% H2O at RT

- Duan L.; Fischer A.; Xu Y.; Sun L. Isolated Seven-Coordinate Ru(IV) Dimer Complex with [HOHOH]–Bridging Ligand as an Intermediate for Catalytic Water Oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 10397–10399. 10.1021/ja9034686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Romero P. E.; Piers W. E. Direct Observation of a 14-Electron Ruthenacyclobutane Relevant to Olefin Metathesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 5032–5033. 10.1021/ja042259d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Romero P. E.; Piers W. E. Mechanistic Studies on 14-Electron Ruthenacyclobutanes: Degenerate Exchange with Free Ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 1698–1704. 10.1021/ja0675245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c van der Eide E. F.; Piers W. E. Mechanistic insights into the ruthenium-catalysed diene ring-closing metathesis reaction. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 571–576. 10.1038/nchem.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efforts to compile kinetics data were thwarted by the long acquisition times for qNMR even for the 1H nucleus. One 16-scan spectrum takes nearly 30 min to collect at the 140-sec D1 required for precise propene quantitation

- Nascimento D. L.; Fogg D. E. Origin of the Breakthrough Productivity of Ruthenium-CAAC Catalysts in Olefin Metathesis (CAAC = Cyclic Alkyl Amino Carbene). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 19236–19240. 10.1021/jacs.9b10750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Occhipinti G.; Nascimento D. L.; Foscato M.; Fogg D. E.; Jensen V. R. The Janus Face of High Trans-Effect Carbenes in Olefin Metathesis: Gateway to Both Productivity and Decomposition. Chem. Sci. 2022, 13, 5107–5117. 10.1039/D2SC00855F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C.; Nascimento D. L.; Fogg D. E. Routes to High-Performing Ruthenium-Iodide Catalysts for Olefin Metathesis: Phosphine Lability Is Key to Efficient Halide Exchange. Organometallics 2021, 40, 1811–1816. 10.1021/acs.organomet.1c00253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracz A.; Matczak M.; Urbaniak K.; Skowerski K. Nitro-Grela-Type Complexes Containing Iodides – Robust and Selective Catalysts for Olefin Metathesis Under Challenging Conditions. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2015, 11, 1823–1832. 10.3762/bjoc.11.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The susceptibility of Ru-iodide complexes to aquation can be amplified or curtailed, depending on the other ligands present. See ref (26) and:; Dougan S. J.; Habtemariam A.; McHale S. E.; Parsons S.; Sadler P. J. Catalytic organometallic anticancer complexes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 11628–11633. 10.1073/pnas.0800076105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivin K. J.; Mol J. C.. Olefin Metathesis and Metathesis Polymerization; Academic Press: New York, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Fogg D. E.; Foucault H. M.. Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. In Comprehensive Organometallic Chemistry III; Crabtree R. H., Mingos D. M. P., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, 2007; Vol. 11, pp 623–652. [Google Scholar]

- Engel J.; Smit W.; Foscato M.; Occhipinti G.; Törnroos K. W.; Jensen V. R. Loss and Reformation of Ruthenium Alkylidene: Connecting Olefin Metathesis, Catalyst Deactivation, Regeneration, and Isomerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 16609–16619. 10.1021/jacs.7b07694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabari D. S.; Tolentino D. R.; Schrodi Y. Reactivation of a Ruthenium-Based Olefin Metathesis Catalyst. Organometallics 2013, 32, 5–8. 10.1021/om301042a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whereas bulkier ligands can improve water-tolerance (albeit at the cost of slower reaction), attempts to curb decomposition by use of high dilutions is ineffective. See: ref (19). Significant negative impacts of water were established in RCM macrocyclization, despite Ru concentrations in the micromolar regime. The accelerating effect of the higher H2O:Ru ratio on aquation-enabled decomposition (both β-elimination and BMD) appears to dominate over the inhibiting effect of lower Ru concentrations on rates of BMD

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.