Abstract

Inflammation and resolution are dynamic processes comprised of inflammatory activation and neutrophil influx, followed by mediator catabolism and efferocytosis. These critical pathways ensure a return to homeostasis and promote repair. Over the past decade research has shown that diverse mediators play a role in the active process of resolution. Specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs), biosynthesized from fatty acids, are released during inflammation to facilitate resolution and are deficient in a variety of lung disorders. Failed resolution results in remodeling and cellular deposition through pro-fibrotic myofibroblast expansion that irreversibly narrows the airways and worsens lung function. Recent studies indicate environmental exposures may perturb and deregulate critical resolution pathways.

Environmental xenobiotics induce lung inflammation and generate reactive metabolites that promote oxidative stress, injuring the respiratory mucosa and impairing gas-exchange. This warrants recognition of xenobiotic associated molecular patterns (XAMPs) as new signals in the field of inflammation biology, as many environmental chemicals generate free radicals capable of initiating the inflammatory response. Recent studies suggest that unresolved, persistent inflammation impacts both resolution pathways and endogenous regulatory mediators, compromising lung function, which over time can progress to chronic lung disease. Chronic ozone (O3) exposure overwhelms successful resolution, and in susceptible individuals promotes asthma onset. The industrial contaminant cadmium (Cd) bioaccumulates in the lung to impair resolution, and recurrent inflammation can result in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Persistent particulate matter (PM) exposure increases systemic cardiopulmonary inflammation, which reduces lung function and can exacerbate asthma, COPD, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). While recurrent inflammation underlies environmentally induced pulmonary morbidity and may drive the disease process, our understanding of inflammation resolution in this context is limited. This review aims to explore inflammation resolution biology and its role in chronic environmental lung disease(s).

Keywords: Inflammation, Resolution, SPMs, Gasotransmitters, ALI, Asthma, IPF, COPD, Pollutants, Environment, Oxidative stress, Clearance

1. Introduction

Most environmentally induced injury is mediated by two important mechanisms, oxidative stress, and inflammation (Wiegman et al., 2020; Ghezzi et al., 2018; Peters et al., 2021; Elonheimo et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2009). Exposure to ambient air pollution is the fourth leading cause of pulmonary and extrapulmonary morbidity worldwide (Lancet., 2020) and a major public health concern (2021 WHO Air Quality Report; https://www.who.int/news/item/04-04-2022-billions-of-people-still-breathe-unhealthy-air-new-who-data, 2019 European Environment Agency report; https://www.eea.europa.eu/publications/air-quality-in-europe-2019). Air pollutants such as O3 and PM induce inflammation directly or indirectly through reactive metabolites, that can cause cellular injury, degeneration, and cell death (Clements, 2011; Ramaka et al., 2020). In vitro and acute exposure studies demonstrate a strong correlation between redox-active chemicals produced during exposure, and their capacity to promote oxidative injury and subsequent inflammation (Donaldson et al., 2003; Li et al., 2008; Rao et al., 2018; Bromberg, 2016). The environmental contaminant Cd, while less prevalent, is also a major public health concern (WHO).

The lungs are protected by the respiratory epithelium, a physical barrier buffered by a network of specialized immune cells that sense and initiate protective inflammatory responses to infection or environmental insults (Borger et al., 2019). Alveolar macrophages respond by secreting soluble inflammatory mediators (ie: cytokines, chemokines, free radicals), and cyclooxygenase (COX)-derived eicosanoids [ie: prostaglandins (PGs), leukotrienes (LTs)] to the site of injury (Fullerton and Gilroy, 2016). This triggers a complex coordinated sequence of events that increase vascular permeability, and recruit neutrophils (PMNs), monocytes and macrophages to the site of damage.

The resolution of inflammation was originally perceived to be a passive process to remove inflammatory stimuli, dilute the proinflammatory chemokine gradient, and prevent neutrophil influx. Instead, over the past two decades, research has shown it to be a dynamic, complex process involving parallel pathways and diverse endogenous mediators that act on key events of inflammation (Serhan and Petasis, 2011). This includes a set of specialized pro-resolving mediators, or SPMs (coined by Dr. Serhan’s group at Harvard), that limit or stop neutrophil influx, polarize macrophages from proinflammatory to anti-inflammatory phenotype, and clear cell debris (Serhan et al., 2000; Levy et al., 2001; Stables and Gilroy, 2011; Serhan et al., 2015). See comprehensive reviews on inflammation resolution for additional details (Serhan et al., 2015; Headland and Norling, 2015; Panigrahy et al., 2021).

Uncontrolled acute lung injury (ALI) due to dose or duration of exposure, and persistent non-resolving inflammation contribute to pulmonary morbidity (Nathan and Ding, 2010; Leitch et al., 2008). This review will present a brief overview of mechanisms and mediators of inflammation resolution (Fig. 1), the relationship between oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling, and examples of environmentally induced lung inflammation. Finally, we present impacts of chronic environmental exposures and potential research efforts to address inflammation resolution and lung disease susceptibility.

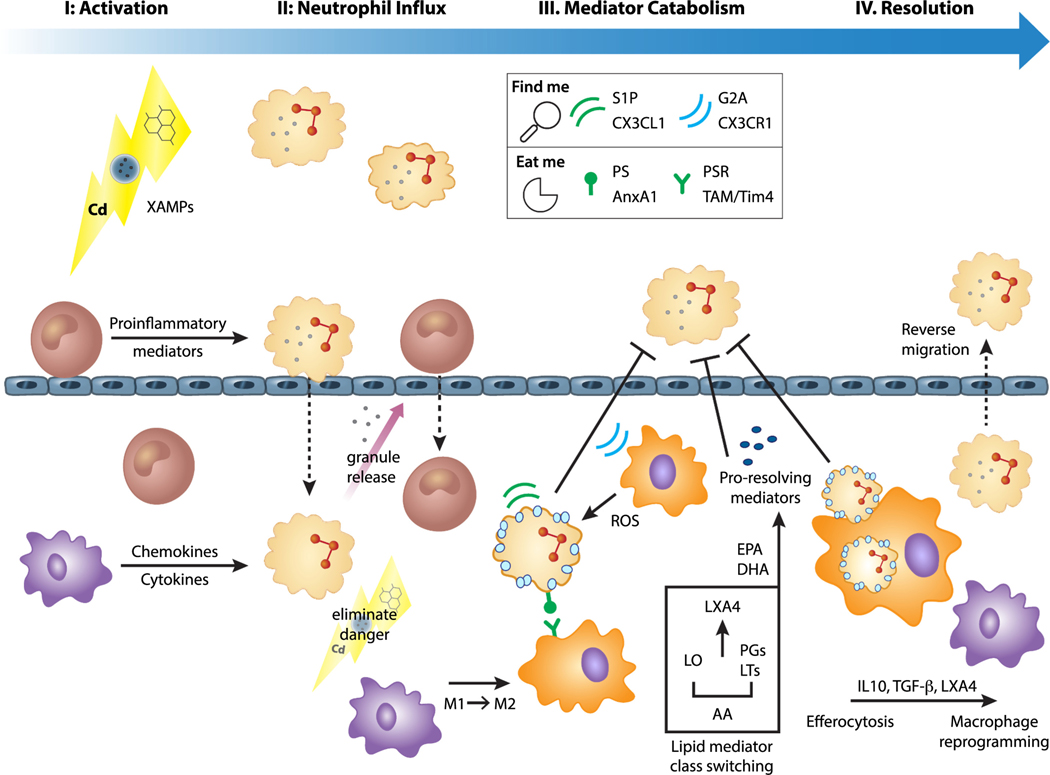

Fig. 1.

Phases of Inflammation Resolution

I. Inflammatory initiation Oxidative damage detected by monocytes (brown) and macrophages (purple) promotes the release of danger signals, or xenobiotic associated molecular patterns (XAMPs), recognized by resident airway cells. II. Neutrophil influx This initiates a signaling cascade that activates NFκB and stimulates release of inflammatory mediators that recruit neutrophils (beige) to the site of injury. Monocytes migrate to the damage site and differentiate from pro-inflammatory M1 into pro-resolving M2 macrophages (orange) to dampen inflammation and stimulate the release of prostaglandins (PGs) and anti-inflammatory IL10. III. Inflammatory mediator catabolism Overlapping programs mediate chemokine proteolysis, halt further neutrophil trafficking, and promote resolution. PGE2 initiates lipid mediator class switching to signal resolution, activating lipoxin A4 (LXA4) via arachidonic acid (AA) metabolism by lipoxygenase (LO). These specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) derived from polysaturated fatty acids [ie: docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA)] interact with leukocyte receptors to trigger monocyte locomotion and uptake of apoptotic neutrophils. Apoptotic cells express soluble chemotactic factors on their cell surface that help attract macrophages for phagocytosis. These chemotactic “find me” [ie: sphingosine 1 phosphate (S1P), G-protein coupled receptor 132 (GPR132 or G2A), C-X3-C motif chemokine ligand 1 and receptor 1 (CX3CL1 and CX3CR1)] and “eat me” factors [phosphatidyl serine and receptor (PS and PSR), annexin A1 (AnxA1), myeloproliferative syndrome transient locus (TAM)/(Tim4) T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain containing 4] promote efferocytosis. Additional feedback loops modify chemokine gradients to promote neutrophil efflux. IV. Efferocytosis Chemokine proteolysis proceeds through phagocytic recognition and clearance, and efferocytosis constitutes an additional resolution signal. Macrophage reprogramming proceeds through induction of transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) and other factors that ensure a return to homeostasis. While localization from the bone marrow to the targeted injury site is mainly unidirectional, neutrophil clearance can also occur by revere migration to locally resolve lung inflammation.

2. Resolution mediators

Broad acting resolution mediators stimulate and actively promote resolution during systemic and local inflammation. This includes diverse lipid mediators, such as SPMs [ie: lipoxins (LX), resolvins (Rv), protectins (PD), and maresins (MaR) (Serhan, 2007)] and annexin A1 (AnxA1) (Gobbetti and Cooray, 2016), as well as gasotransmitters [ie: nitric oxide (NO), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), and carbon monoxide (CO)] (Wallace et al., 2015) that activate the immune system. In addition, other endogenous proteins and inhibitors modulate resolution pathways during ALI-induced inflammation.

2.1. Specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs)

SPMs play a critical role in acute inflammation resolution and are produced by the coordinated actions of macrophages, neutrophils, platelets, and endothelial cells (Serhan, 2014). Main classes of SPMs are produced from ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) such as eicosapentaenoic (EPA), docosahexaenoic (DHA), docosapentaenoic acid (DPA), and from ω-6 PUFAs such as arachidonic acid (AA), through concerted enzymatic activity of lipoxygenases (LO), COX, and cytochrome P-450. Eicosanoids (ie: PGs, LTs) are produced by the COX pathway of AA metabolism during inflammation. PGE2 initiates lipid mediator class switching to signal resolution, activating lipoxins (LXs) through AA metabolism by LO. This shifts production of LTB4 and 5LO, to pro-resolving LXA4 and 15LO to enhance SPM synthesis (Levy et al., 2001).

COX and LO are differentially expressed and cell specific. 15LO is expressed in eosinophils and epithelial cells, 5LO in granulocytes, and 12LO in platelets, while COX2 is expressed in endothelial cells (Romano et al., 2015). The D-series resolvins 1–6 (RvD1–6), maresins (MaR1–2), protectins/neuroprotectins (PD1/NPD1, PDX), and their disulfido conjugates (cys-SPMs: RCTRs, MCTRs, PCTRs) are derived from DHA (Chiang and Serhan, 2017). A small set of E-series resolvins, which include RvE1–3 and their 18S-epimers (18S-RvE1–3), are synthesized from EPA. Biosynthetic pathways and downstream signaling mechanisms of SPMs that mediate inflammation resolution are well characterized and details are available in reviews by Serhan and Leuti (Serhan and Petasis, 2011; Chiang and Serhan, 2017; Leuti et al., 2020).

SPMs act on immune and tissue-resident cells through their cognate receptors or as partial agonists of inflammatory receptors (Chiang et al., 2008). SPMs bind high affinity G-protein-coupled receptors [ie: formyl peptide receptor (ALX/FPR2), GPR32, ChemR23], blocking neutrophil influx and promoting macrophage polarization for efferocytosis and repair (Hachicha et al., 1999; Chiang and Serhan, 2020). For instance, RvD5 targets phospholipase D, which promotes phagocytic activity (Ganesan et al., 2020). RvD1 supplementation suppresses inflammatory cytokine production in primary cells exposed to cigarette smoke (CS), with significant anti-inflammatory interleukin (IL10) activation (Hsiao et al., 2013). Additionally, SPMs induce an anti-fibrotic response by repressing matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and activating tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP) expression in fibroblasts (Jaén et al., 2021).

2.2. Gasotransmitters

Nitric oxide (NO), hydrogen sulfide (H2S), and carbon monoxide (CO) are considered gasotransmitters capable of mediating inflammation resolution (Wallace et al., 2015). They freely diffuse across membranes and have no specific receptors, instead interacting with multiple proteins and receptors with a wide range of biological effects. NO acts as a vasodilator and second messenger and its actions are mediated through soluble guanylate cyclase. Free radicals produced during inflammation include NO and it participates in resolution through modulation of apoptosis (Brüne, 2005). H2S is a potent vasorelaxant implicated in oxygen sensing and a recognized resolution mediator (Zhao et al., 2001). It polarizes macrophages to their pro-resolving phenotype to promote efferocytosis (Dufton et al., 2012) and facilitates leukocyte clearance from the vascular endothelium (Zanardo et al., 2006). Studies using an H2S donor showed a dose dependent increase in COX activity and decreased mucosal inflammation in a gut injury model (Blackler et al., 2015).

Inducible heme oxygenase-1 (HO1) acts as a cellular stress sensor, and limits tissue injury through CO production (Motterlini and Foresti, 2014). Cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory activities of CO are partly mediated by its effects on metal carbonyls that modify redox signaling, and CO has shown therapeutic potential in animal models of ALI (Ryter and Choi, 2011). Synergy between gasotransmitters and SPMs may amplify their resolution effects. Anti-inflammatory activity of H2S is mediated by AnxA1 (Brancaleone et al., 2014), and 15LO knockdown reduced CO-stimulated phagocytosis through increased production of RvD1 and MaR1 (Chiang et al., 2013). This constitutes a pro-resolving circuit whereby SPMs stimulate HO1 to release CO, and CO increases 15LO to promote SPM biosynthesis.

2.3. Acute lung injury (ALI) resolution mediators

Proteins that target inflammatory mediators to promote resolution have been identified in ALI models and other inflammatory diseases. Secreted proteins [ie: lactoferrin (Lf) (Bournazou et al., 2009), netrin-1 (Mirakaj et al., 2010)] are activated during ALI to suppress neutrophil influx. Chemotactic factors [ie: sphingosine 1 phosphate, S1P (Fettel et al., 2019)] and protease inhibitors [ie: TIMP2, secretory leucoprotease inhibitor, SLPI (Gipson et al., 1999)] also control and reduce neutrophil influx. In addition, adenosine receptor A2BAR (Sun et al., 2006) attenuates ALI through fluid clearance (Eckle et al., 2008), and neutrophil elastase (NE) inhibition reduces tissue damage from ALI (Polverino et al., 2017).

3. Oxidative stress and inflammation

Redox signaling is integral to almost all physiological systems. Reactive intermediates produced by detoxification enzymes and lipid mediators (ie: LO, COX) are by-products of normal biological functions and electron transfer in a variety of lung cells (Checa and Aran, 2020). These include free radicals (ie: superoxide, hydroxyl radical, NO), hydrogen peroxide, and singlet oxygen that act as second messengers in intracellular signaling (Finkel, 2011). The collection of ions and reactive species formed constitute reactive oxygen or nitrogen species (ie: ROS, RNS). Other redox active species have gained attention and are reviewed elsewhere (Olson, 2020; Labunskyy et al., 2014; Semchyshyn, 2014). ROS react with cysteine residues in target proteins, and thiol oxidation modulates activity during redox signaling (Poole, 2015; Ulrich and Jakob, 2019). Redox potential, or the ratio of redox pairs in reduced and oxidized forms [ie: glutathione (GSH/GSSG)] drives the rate at which they undergo electron transfer, differing spatiotemporally based on microenvironment (Sies et al., 2017). In moderation, ROS are kept in check by cytoprotective antioxidant defense systems [ie: superoxide dismutases (SODs), glutathione peroxidases] that neutralize reactive intermediates (Sies et al., 2017). For more information, readers are referred to excellent reviews on oxidative stress, redox signaling and the lung (Rogers and Cismowski, 2018; van der Vliet et al., 2018; Sarma and Ward, 2011).

Oxidative stress and inflammation are interrelated biological mechanisms that seem to occur simultaneously to amplify injury. In the lung, tissue injury triggers the release of xenobiotic danger signals or XAMPs [ie: serum amyloid A (SAA) or high mobility group box protein 1 (HMGB1)] into the extracellular space (Tolle and Standiford, 2013). Pattern recognition receptors [ie: toll like receptors (TLRs), nod-like receptors (NLRs)], activate the innate immune response (Tolle and Standiford, 2013). Overlapping intracellular signaling pathways induce redox sensitive transcription factors [ie: nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of B cells (NFκB), tumor protein p53 (p53), hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha (HIF1α), nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)] that regulate expression of inflammatory cytokines and anti-inflammatory molecules (Mittal et al., 2014). Similarly, mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) relays oxidative stress signals and promotes the inflammatory response through activation of NFκB (Ray et al., 2012). It is well established that NFκB signaling plays a central role in oxidative stress-induced inflammation (Bubici et al., 2006).

The release of oxidized peroxiredoxin-2 (PRDX2) and thioredoxin (TRX) from macrophages alters redox status of cell surface receptors and promotes tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα)-induced inflammation (Salzano et al., 2014). In addition, activation of COX2 and inducible NO synthase (iNOS) causes aberrant expression of inflammatory cytokines (ie: TNF, interleukins, IL1, IL6, IL8) and chemokines [ie: C-C motif (CCL2, CCL5), C-X-C motif (CXCL1, CXCL8)] (Bayarri et al., 2021; Becker et al., 2005). Oxidative stress-induced inflammation also affects expression of regulatory microRNAs (miRNAs) that modulate the immune response (Neudecker et al., 2017). SPMs regulate cellular oxidative stress both by inhibiting ROS production and by increasing antioxidant defense through modulation of SOD, HO1 and NRF2 expression (Leuti et al., 2019).

4. Pre- and post-resolution crosstalk and repair

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are potent mediators of intercellular crosstalk during lung inflammation. They ensure protein and lipid exchange, and intercellular transport of genetic material through EV-mediated signal transfer (Lee et al., 2018; Bissonnette et al., 2020; Andres et al., 2020). EVs encompass exosomes, microvesicles and apoptotic bodies, and the cargo transported (miRNAs, regulatory mediators, XAMPs, etc.) depends on environmental exposure and inflammatory state. Resident and phagocytosing macrophages release EVs in response to injury, targeting cargo to epithelial and endothelial lung cells (Lee et al., 2018). Epithelial cells, highly sensitive to inhaled pollutants, also produce EVs that contribute to the pro-inflammatory environment. Endothelial-derived EVs influence inflammatory macrophage activation. EV cargo (ie: miR-191, miR-126, miR-125a) can inhibit efferocytosis by macrophages (Lee et al., 2016) and miR-125a is involved in macrophage polarization and inflammatory damage (Placek et al., 2019).

Following inflammation resolution, macrophages secrete granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) to promote repair and must egress through the draining lymph nodes to reestablish homeostasis (Ortega-Gómez et al., 2013). This cellular crosstalk is critical to restore the injured lung endothelium. Intrinsic self-repair mechanisms, and the release of bioactive mediators promote barrier function restoration (Birukov and Karki, 2018). Growth factors, as well as anti-inflammatory chemokines, ILs, and PGs, activate proteins involved in cell spreading and migration (Crosby and Waters, 2010). Compartments within the respiratory system contain distinct basal progenitor cells for tissue regeneration, and repopulation leads to functional recovery (Zepp and Morrisey, 2019).

Intercellular crosstalk between stromal (ie: epithelial, endothelial cells and fibroblasts) and immune cells activates resolution and repair pathways (Worrell and MacLeod, 2021). The proximal airways contain alveolar type I and type II epithelial cells for maintenance of gas exchange and surfactant secretion (Robb et al., 2016). These cells engage in dynamic epithelial-endothelial crosstalk, through bridge connections with the endothelial capillary plexus to promote alveolar repair (Zepp and Morrisey, 2019). During repair, fibroblasts migrate from the lung interstitium to the site of injury. Subpopulations express different surface markers and growth characteristics according to cell type, activation stage or environmental cues (Hinz et al., 2007). Fibroblasts modulate immune cell behavior by adjusting the local cellular or cytokine microenvironment to initiate lung remodeling (Worrell and MacLeod, 2021).

5. Chronic inflammatory lung diseases and resolution

Unresolved inflammation in chronic lung diseases such as asthma, ALI, and COPD is often associated with defective efferocytosis (Leitch et al., 2008; Belchamber and Donnelly, 2017; Donnelly and Barnes, 2012). In asthmatics, apoptotic cell accumulation promotes chronic airway inflammation, excess mucus production, and scarring (Yang et al., 2021; Martinez and Cook, 2021). Reduced LX levels observed in asthmatic lungs could be due to SPM deficiencies in asthma (Yang et al., 2021), either from defective biosynthesis or dysregulated expression of the LXA4 receptor ALX/FPR2 (Levy et al., 2005; Levy et al., 2012; Kazani et al., 2013). Enhanced LT production and reduced LX synthesis is implicated in severe asthma exacerbation (Levy, 2005) and may also result from PUFA deficiency (AA, DHA) in the airway mucosa (Duvall and Levy, 2016). In vivo intravenous administration of PD1 prior to allergen challenge reversed airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) and eosinophilic inflammation in an allergic asthma model, supporting therapeutic potential of PUFA supplementation (Levy et al., 2007). Successful treatment of inflammatory diseases may depend on timing, as well as dietary ratio of ω-3 to ω-6 PUFA and deserves further study (Barros et al., 2011; Allan and Devereux, 2011).

COPD is characterized by airflow limitation along with chronic, persistent inflammation, and macrophages play a significant role in COPD pathogenesis (Shapiro, 1999). A marked increase in macrophages is detectable in the airways, lung parenchyma, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF), and sputum of COPD patients (Pesci et al., 1998; Keatings et al., 1996). Diverse macrophage subpopulations are present in COPD inflamed lungs (Vlahos and Bozinovski, 2014) and they do not conform to classical M1/M2 phenotypes. The inflammatory milieu may drive this polarization (Hodge et al., 2011; Mosser and Edwards, 2008) and their relative balance can profoundly impact disease progression (Eapen et al., 2017). The M1 and M2 (subtypes M2a, M2b, M2c, M2d) macrophage phenotypes are pro- and anti-inflammatory respectively (Chávez-Galán et al., 2015). M1 macrophages, or classically activated (cytotoxic) macrophages, produce high levels of proinflammatory cytokines (ie: TNFα, IL1ß, IL6, IL8) (Wynn and Vannella, 2016; Laskin et al., 2019) with bactericidal properties. Conversely, M2 macrophages, or alternatively activated (wound repair) macrophages, produce anti-inflammatory factors (ie: IL10, IL13) and participate in tissue remodeling (Laskin et al., 2019). The accumulation of specific subsets may affect inflammation resolution to restore lung homeostasis (Vlahos and Bozinovski, 2014).

LXA4 production is also decreased in induced sputum and exhaled breath condensates from COPD patients (Kim et al., 2016; Croasdell et al., 2015). Airflow obstruction correlated with decreased alveolar LXA4 and increased ALX/FPR2 in asymptomatic smokers, suggesting persistent airway inflammation perturbs resolution pathways (Bozinovski et al., 2014). RvD1 levels are also reduced in both serum and BALF of COPD patients (Croasdell et al., 2015). When macrophages isolated from COPD patients were incubated with either RvD1 or RvD2 and then exposed to cigarette smoke extract, both resolvins restored macrophage function, and administration of RvD2 alone increased the ratio of M2 to M1 macrophages (Croasdell et al., 2015).

Continued oxidative exposure at the mucosal surface disrupts miRNA biogenesis and can lead to increased permeability with uncontrolled bidirectional toxicant passage, chronic pulmonary inflammation, and immune dysfunction (Neudecker et al., 2017). Specific miRNA expression patterns are activated in inflamed lung tissue including the master regulator miR-155 (Mahesh and Biswas, 2019). Additional inflammatory factors (IL1, TNFα) modulate miRNA expression, and extracellular miRNAs themselves can be shuttled between cells and tissues to exacerbate or resolve the inflammatory response.

Chronic lung inflammation is associated with shifts in tissue metabolism and mtDNA damage (Aghapour et al., 2020). Anti-inflammatory macrophages use fatty acid oxidation and oxidative phosphorylation for energy production (Michaeloudes et al., 2020). In addition, low levels of endogenous PUFA restrict SPM biosynthesis and prevent proper resolution and airway remodeling (Table 1) (Michaeloudes et al., 2020). Other resolution mediators and gasotransmitters are dysregulated due to persistent oxidative stress (Sun et al., 2015; Varani et al., 2010; Thomas et al., 2022; Chalmers et al., 2017). Further studies are needed to confirm their role in resolution, especially in the context of pollutant-induced chronic inflammation.

Table 1.

Clinical and preclinical studies of SPMs and airway disease. Outcomes of either SPM deficiency (top) or SPM supplementation (bottom) are shown.

| Clinical and ex vivo SPM deficiency studies | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| - SPM | Airway disease | Deficiency outcome | Reference |

| LXA4 | asthma | ↓in EBCs (children); FEV1 decline ↓in WB; ↑airflow obstruction |

(Levy et al., 2005; Hasan et al., 2012) |

| neutrophilic asthma COPD | ↓precursors and LXA4 in EBCs | (Fritscher et al., 2012) | |

| aspirin-intolerant asthma | ↓biosynthetic capacity for LXs | (Sanak et al., 2000) | |

| asthma (LPS-stimulated AMs) | ↑ROS generation and vascular leakage | (Bhavsar et al., 2010) | |

| PD1 | asthma exacerbation | ↓in EBCs | (Levy et al., 2007) |

| allergic asthma | ↓biosynthesis in eosinophils | (Miyata et al., 2013) | |

| MCTRs | allergic asthma (precision cut lung slices) | ↑LTD4 contraction and narrowed airways | (Levy et al., 2020) |

|

| |||

| Preclinical SPM supplementation studies (in vivo) | |||

|

| |||

| + SPM | Airway disease | Supplementation outcome | Reference |

|

| |||

| PD1 | allergic asthma | ↑clearance of eosinophils and T cells | (Levy et al., 2007) |

| MaR1 | ARDS | ↓neutrophil influx and edema | (Abdulnour et al., 2014) |

| allergic inflammation | ↓ILC2; ↑amphiregulin | (Krishnamoorthy et al., 2015) | |

| RvD1 | LPS-induced ALI | ↓TNFα, IL6, IL23 | (Wang et al., 2011) |

| allergic asthma | ↓eosinophilia, mucus metaplasia, and AHR | (Rogerio et al., 2012) | |

| RvD1/RvD4 | allergic asthma | ↓eosinophilia; ↑macrophage polarization (LCPUFA combination) |

(Fussbroich et al., 2020) |

| AT-RvD1 | allergic asthma | ↑↑resolution of eosinophilia | (Rogerio et al., 2012) |

| ALI | ↑barrier integrity; ↓airway resistance | (Eickmeier et al., 2013) | |

| RvE1 | allergic asthma | ↓IL23 and IL6; ↑IFNγ | (Haworth et al., 2008) |

| ↓eosinophilia, AHR, and mucus metaplasia | (Aoki et al., 2008) | ||

| ↓inflammatory cells | (Flesher et al., 2014) | ||

| HCl-induced ALI | ↓HMGB1; ↑survival | (Seki et al., 2010) | |

| MCTR1 | LPS-induced ALI | ↓serum levels of inflammatory cytokines, heparan sulfate, and syndecan-1 | (Li et al., 2020b) |

| MCTR1/MCTR3 | allergic asthma | ↓eosinophilia | (Levy et al., 2020) |

| PCTR1 | LPS-induced ARDS | ↑fluid clearance and sodium channel expression | (Zhang et al., 2020) |

| RCTR2/RCTR3 | Ischemia-reperfusion secondary lung injury | ↓neutrophilia in lungs | (de la Rosa et al.,2018) |

LT = leukotriene, LCPUFA = long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Lipoxin (LX), protectin (PD), maresin (MaR), resolvin (RvD and RvE) series. AT = aspirin-triggered isomers, MaR, PD, or Rv conjugate tissue regeneration conjugates (MCTR, PCTR, RCTR). LPS = lipopolysaccharide; HCl = hydrochloric acid; EBC = exhaled breath condensate; WB = whole blood; AMs = alveolar macrophages, ILC2 = type 2 innate lymphoid cells. FEV1 = forced expiratory volume in 1 second; ALI = acute lung injury; ARDS = acute respiratory distress syndrome; AHR = airway hyperresponsiveness.

6. Chronic inflammation in environmental induced lung disease

Chronic exposure to environmental pollutants significantly contributes to global lung morbidity and mortality. In addition to dose and duration of exposure, factors that influence disease trajectory include genetic susceptibility and pre-existing disease status. As genetic susceptibility is beyond the scope of this review, we direct readers to epidemiological studies of interest (Pederson et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2016; Singh et al., 2020; Ciesielski et al., 2018; Imboden et al., 2015). Increasing evidence indicates air pollutant exposure affects epigenetic regulation. Studies have shown reduced DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) activity (Bontinck et al., 2020; Rider and Carlsten, 2019) and increased histone H4 acetylation are associated with obstructive lung diseases (Ito et al., 2005; Guo et al., 2021).

Numerous in vitro studies and diverse in vivo exposure models provide evidence that environmental exposures exacerbate chronic inflammatory diseases such as asthma, COPD, and IPF. Epidemiological studies of O3, PM, and Cd exposure show plausible association with these chronic inflammatory diseases (Zu et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2017; Thompson, 2018; Richter et al., 2017). Primary drivers of lung diseases are ROS-induced biochemical mediators that enhance cytokine production and the accumulation of inflammatory cells (Checa and Aran, 2020; Yang et al., 2017; Hirota and Martin, 2013).

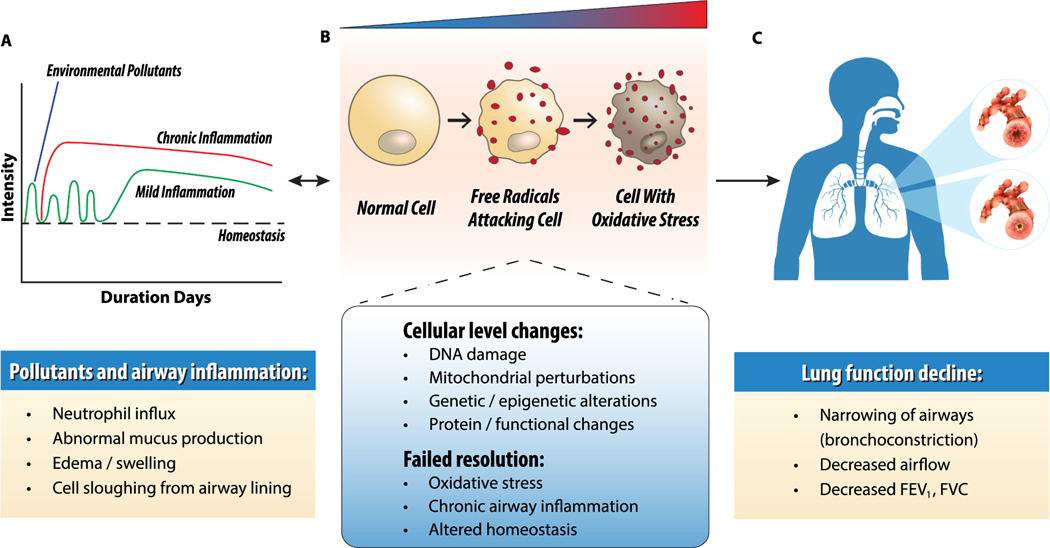

Toxicological and clinical studies of air pollution show persistent, prolonged exposure can induce chronic systemic inflammation (American Heart Association 2021; https://newsroom.heart.org/news/long-term-exposure-to-low-levels-of-air-pollution-increases-risk-of-heart-and-lung-disease). However, whether resultant chronic inflammation is due to failed resolution is unknown. Emerging research postulates that environmental pollutant(s)-induced chronic inflammatory diseases may largely result from failed inflammation resolution (Fig. 2). Here we outline environmental exposures that lead to chronic lung disease, identify potential mediators, and explore studies related to inflammation resolution.

Fig. 2.

Effects of environmental pollutants on lung inflammation. A. Environmental pollutant exposure causes oxidative stress, inflammation, and acute lung injury. Prolonged or high-dose exposure overwhelms resolution pathways and leads to chronic airway inflammation. Due to chronic inflammation, tissue injury persists and does not return to homeostasis. B. Oxidative stress and redox imbalance initiates physiological, cellular, and molecular perturbations that contribute to failed resolution, chronic airway inflammation, and respiratory disease. C. Chronic inflammation irreversibly narrows the airways (bronchoconstriction) to obstruct airflow and reduce lung function [forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), forced vital capacity (FVC)].

6.1. O3-induced neutrophilic asthma

Environmental ozone (O3) is generated by interactions of traffic-related air pollutants with sunlight. Acute exposures cause epithelial barrier disruption, neutrophil recruitment, and AHR (Sokolowska et al., 2019; Michaudel et al., 2018). O3 reacts directly with respiratory surface molecules to form free radicals and indirectly generates reactive by-products through aerobic metabolism (Lodovici and Bigagli, 2011). Chronic O3 exposure promotes progressive alveolar destruction, aberrant airway remodeling, and asthma onset. Asthma is classified by predominant inflammatory cell type, either eosinophilic (allergic or atopic) or neutrophilic (non-atopic or glucocorticoid (GC)-resistant), and O3 exposure exacerbates symptoms of both. While allergic asthma typically responds to rescue inhaler treatment, neutrophilic asthma is clinically more severe and resistant to corticosteroids due to glucocorticoid receptor (GR) deficiency (Tripple et al., 2020; Vervloet et al., 2020).

O3 activates TLRs, and signals through phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) or MAPK pathways to induce NFκB and inflammatory cytokine expression (IL17A, IL22, IL33) that promotes neutrophil influx. The aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) may contribute to GC-resistant asthma in response to O3. A recent study showed chronic O3-induced lung inflammation and tissue remodeling were associated with LXA4, AhR activation, and recruitment of IL17A and IL22 expressing cells (Michaudel et al., 2020). Acute O3 exposure (24 hours) significantly decreased 12/15-LO and ALX/FPR2 expression, reducing levels of SPM precursors (Kilburg-Basnyat et al., 2018). SPM biosynthetic intermediates (14-HDHA, 17-HDHA), and PDX were reduced in vivo and rescued by SPM precursor administration. Sex-specific differences were noted in subsequent O3 studies, and female mice produced higher levels of precursor PUFAs (AA, DHA) and SPMs (RvD5) compared to males (Yaeger et al., 2021).

Further, O3 oxidizes phosphatidylcholines (PCs) that make up lung surfactant (da Costa et al., 2020) which affects surface tension in the lung. O3-induced inflammation was increased in surfactant protein D (SP-D) knockout mice, and elevation was associated with dysregulated inflammation resolution (Kierstein et al., 2006). Additional studies by Laskin et al show surfactant protein D (Sftpd) modulates the O3-induced macrophage response in vivo. Loss of Sftpd prolonged lung injury and M2 activation, which caused functional changes to parenchymal integrity (Groves et al., 2012).

Recent in vivo studies suggest EVs enhance O3-induced toxicity through miRNAs transported to alveolar macrophages that promote inflammation (Carnino et al., 2022). BALF from O3-exposed mice had increased amounts of miR-17, miR-92a, and miR-199a (Andres et al., 2020). Further, EV adoptive transfer from O3-exposed mice to naïve controls increased inflammatory cytokines in alveolar macrophages. O3 reacts with cholesterol in the lung lining, to generate oxysterols that form adducts with macrophage cell surface receptors to block phagocytic function (Duffney et al., 2020). Additional research on perturbations that affect efferocytotic capacity and SPM synthesis will aid our understanding of inflammation resolution and its association with environmental asthma.

6.2. Cd-induced COPD

Heavy metal cadmium (Cd) is released by industrial mining and smelting and contaminates soil and water. Cd, ingested through food or inhaled through CS, has an extremely long half-life. Cd exposure indirectly generates ROS through oxidation of redox-sensitive cysteine thiols (Nemmiche, 2017). This affects intracellular glutathione levels and promotes ROS production (Kiran Kumar et al., 2016) which impacts immune cell function and redox balance through cellular depletion of antioxidant enzymes (Larson-Casey et al., 2020). Deleterious respiratory effects are seen in vivo of acute CdO nanoparticles at occupationally relevant medical imaging levels (Blum et al., 2014).

Chronic Cd exposure disrupts the epithelial barrier, promotes monocyte influx, and production of dysfunctional macrophages. Cd causes monocytic differentiation in vitro (Ober-Blöbaum et al., 2010¨) consistent with systemic inflammation seen in COPD patients (Hirota and Martin, 2013). While Cd does not directly generate free radicals, it alters superoxide to generate NO that activates NFkB (Ramirez and Gimenez, 2003). Cd also affects redox-active Trx1, increasing NfkB activity with downstream effects on Nrf2, p53, and glutathione reductase (Go et al., 2013).

Cd exposure leads to epigenetic changes in DNA methylation and altered DNMT3b activity in lung fibroblasts (Jiang et al., 2008). In addition, COPD patients had decreased HDAC2 and increased HAT activity (Ito et al., 2005; Barnes et al., 2005) and similar changes in histone activity were seen in chronic Cd treatment in vitro (Liang et al., 2018). Interestingly, miR-223 downregulates HDAC2 expression in lung tissues from COPD patients, leading to M2 macrophage retention and aberrant airway remodeling (Leuenberger et al., 2016). While epigenetic regulation modulates effects of CS-induced COPD, the precise contribution of Cd in these studies is difficult to deduce (Silverman, 2020).

Cd-induced lipid peroxidation affects biophysical membranes (Kiran Kumar et al., 2016) and PUFAs accumulate in phospholipid membranes of COPD patients (ie: AA, DPA), restricting bioavailability (Kotlyarov and Kotlyarova, 2021; Gangopadhyay et al., 2012). Studies investigating Cd-induced COPD have yet to explore potential interactions of Cd-induced oxidative stress and inflammation in the context of resolution mediators. Further characterization of macrophage polarization in Cd-induced COPD may identify candidates with therapeutic potential.

6.3. PM-exacerbated chronic lung diseases

Particulate matter (PM) is a heterogeneous mixture that varies with atmospheric conditions and geographical location in source, size, and composition (Brook et al., 2010). National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) are based on aerodynamic particulate size [PM10 < 10μM, PM2.5 < 2.5μM, and PM0.1 < 0.1μM or ultra-fine particulates (UFPs)]. Particulate size affects deposition in the lung, and composition affects recognition and differential inflammatory response. Trace elements in PM10, and insoluble biological and microbial contaminants (ie: lipopolysaccharide, LPS) trigger epithelial disruption in the upper and lower airways (Falcon-Rodriguez et al., 2016). Inhaled PM2.5 penetrates deep into the small airways, with diverse soluble components [ie: environmentally persistent radicals, metals (Cu, Ni, V, Fe)] that cause systemic oxidative stress, unresolved airway inflammation, and lung function decline (Rice et al., 2015; Riediker et al., 2019; Jiang et al., 2019). UFPs often carry reactive organics (ie: polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) that contribute to their toxicity (Oberdörster et al., 1994; Oberdörster and Utell, 2002; Oberdörster et al., 2005).

Redox-active PM components generate intracellular oxidative stress and inflammation (Bălă et al., 2021), that contributes to, and exacerbates lung disease (Nakayama Wong et al., 2011; Thurston et al., 2016; Feng et al., 2016). Seminal model particulate studies showed metal contaminants elicit oxidative stress through Fenton and Haber-Weiss reactions (Ghio et al., 2002). PM represses the Nrf2-dependent antioxidant response (Timblin et al., 1998), increasing inflammation and lipid peroxidation (Pardo et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2016a). It is hypothesized that PM2.5-induced inflammation from the pulmonary endothelium spills over into the systemic circulation, and the release of PM-constituents promotes chronic, low-level inflammation in extrapulmonary organs (Orona et al., 2020; Bevan et al., 2021; Wyatt et al., 2020). Repeated or chronic PM2.5 exposure may prolong the resolution phase or promote defective or unresolved inflammation.

PM inhalation activates immune programs in a size-dependent manner, to polarize immune cells (ie: Th17, Treg) and promote resolution. Disruptions are seen in vivo (Harding et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2014), where Th17/Treg imbalance exacerbates chronic obstructive lung disease. Mice exposed to sub-chronic PM2.5 (twice/week for 56 days) had severe airflow decrements (Hou et al., 2021). Interestingly, miR-146 was elevated after PM2.5 exposure, with miR-146b inversely related to airflow index. Sub-chronic PM exposure (8 weeks) decreased HO1 and IL6 tissue levels (Aztatzi-Aguilar et al., 2015) suggesting prolonged exposure-induced inflammation may result from perturbations in the initiation of resolution pathways.

Numerous studies have shown PM exacerbates lung function decline in COPD (Falcon-Rodriguez et al., 2016; Li et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018). Chronic PM exposure promotes alveolar wall destruction, airspace enlargement, and progressive airflow limitation. Chronic PM2.5 (3 months) triggers emphysematous lesions (Hadzic et al., 2020), lung inflammation, and airway remodeling in vivo (Li et al., 2020a). PM2.5 facilitates M2 polarization through HDAC2 inhibition, upregulating TGFβ, MMP9 and MMP12 (Jiang et al., 2020).

Recent studies suggest PM also exacerbates interstitial lung diseases such as IPF (Johannson et al., 2015; Harari et al., 2020; Winterbottom et al., 2018). PM2.5 increased acute inflammation and fibrosis after intratracheal administration in mice (Gangwar et al., 2020; Qin et al., 2018) and chronic exposure led to scar formation through progressive loss of alveolar structure (Günther et al., 2012; Selman et al., 2001). IPF is thought to occur from complex mechanisms, including dysregulated resolution due to PM interactions with pro-fibrotic TGFβ (Líbalová et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2020). IPF biomarkers (Phan et al., 2021; Heukels et al., 2019) are increased in the BALF and lung tissue of IPF patients following PM exposure, including extracellular adenosine (Haskó and Cronstein, 2004) and its receptor A2BAR (Zhong et al., 2005; Ohta and Sitkovsky, 2001). M2 macrophages retained in fibrosis secrete TGFβ, and additional growth factors that correlate with disease severity (Laskin et al., 2019; Ando et al., 2010). Investigating inflammation resolution pathways and mediators in the context of PM exposure will provide critical understanding of pulmonary and extrapulmonary effects involved in systemic chronic inflammation.

7. Future directions

Xenobiotics, specifically particulates and environmental chemicals, generate reactive free radicals capable of initiating the inflammatory response. Inflammation resolution is an orchestrated process whereby diverse endogenous mediators and signaling pathways coordinate to resolve inflammation. Efforts to boost endogenous H2S production through short-term theophylline treatment did not produce detectable increases in serum from COPD patients (Chen et al., 2008). Sputum neutrophil levels were reduced; however, the study was limited by low sample size. A recent clinical trial using injection of another H2S donor improved pulmonary hypertension and lung function in COPD patients (Zhao et al., 2016b). Further investigation into the therapeutic efficacy of gasotransmitters in inflammation resolution is needed.

Novel SPMs are especially relevant to environmental health, as nutritional and dietary interventions show promise in preclinical models of O3 exposure (Kilburg-Basnyat et al., 2018). As SPMs quickly degrade via 15-hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase (15-PGDH), there are concerns with their bioavailability and distribution during clinical administration (Salazar et al., 2022). Use of synthetic analogues that resist degradation or targeting via EVs or nano-based drug delivery provide feasible options. Several intervention trials using combinations of ω-3 and ω-6 PUFA have shown potential in allergic asthma (Okamoto et al., 2000; Jaudszus et al., 2016), but no studies specific to O3-induced neutrophilic asthma have been reported to date.

Epidemiological studies show an association with dietary ω-3 PUFA intake and reduced systemic inflammation in COPD patients (de Batlle et al., 2012; Almagro et al., 2012), and intervention studies have focused on both ω-3 and ω-6 supplementation to improve pulmonary function (Whyand et al., 2018; Ng et al., 2014; Atlantis and Cochrane, 2016; Lemoine et al., 2019; Pizzini et al., 2018). Self-reported improvement in respiratory symptoms (Kim et al., 2021) and reduced COPD exacerbations (Fekete et al., 2021) were noted in several ω−3 dietary intervention trials. ω-6 supplementation showed differing associations with AA intake and systemic inflammation in COPD patients (de Batlle et al., 2012; Julia et al., 2013). However, results often vary according to target, timing, dose, and duration of administration. Additional confounding factors specific to intervention participants (ie: age, genetics, co-morbidities, medication use, environmental exposures) can obscure results (Whyand et al., 2018; Simopoulos et al., 2021). PUFA supplementation may be more effective as a preventative intervention, or in early-stage disease, and its role in promoting resolution of environmental exposure-induced inflammation warrants further investigation.

The ideal approach to prevent lung inflammation would be to eliminate pollutants that initiate the inflammatory response, which is not practical or feasible. Another approach is to control activation by pollutants. Efforts to trap ROS/RNS through increased antioxidant availability are being explored in vitro, and acute animal exposures show inflammatory protection (Maleki et al., 2019). Research efforts of chronic air pollution exposure are needed, as reduced antioxidant status increases disease susceptibility and exacerbation (Weichenthal et al., 2017). Further, comprehensive characterization of NRF2 and NFκB signaling during PM-induced inflammation could identify additional resolution mediators that dampen the inflammatory response.

As discussed earlier, efferocytosis signals a halt to neutrophil recruitment and emigration, and removal by apoptosis reduces further harmful effects. Early data shows supplementation with DHA and SPMs prior to exposure may prevent O3-induced efferocytosis defects and promote inflammation resolution (Kilburg-Basnyat et al., 2018). Elucidating the molecular mechanisms involved in this protective process may reveal intervention strategies with potential translation to humans. Successful efferocytosis stimulates macrophage polarization or reprogramming from inflammatory to pro-resolving phenotypes or vice versa with distinct molecular markers and functions. Few studies have focused on macrophage reprogramming in relation to environmental exposure-induced lung injury (Laskin et al., 2019; Groves et al., 2012). Additional research is needed on the role of altered macrophage subpopulations, particularly in the context of persistent pollutant exposure, chronic inflammation, and immune memory in lung disease(s).

Pro-resolution mediators such as annexin A1 (AnxA1) and angiotensin [Ang-(1–7)] peptides are also promising candidates. AnxA1 inhibits phospholipase A2 and reduces the formation of eicosanoids, to induce neutrophil apoptosis and efferocytosis (Sugimoto et al., 2016; Sheikh and Solito, 2018). Similarly, Ang-(1–7) peptide was initially recognized for its ability to reduce inflammation induced by angiotensin II (Simoes ˜ e Silva et al., 2013). Like AnxA1, Ang-(1–7) mediates neutrophil efflux and promotes efferocytosis in experimental models of asthma (Magalhaes et al., 2018; Magalhaes et al., 2015˜ ), and more recently in SARS-CoV-2-induced acute respiratory failure (Files et al., 2021). Future studies will provide insight on their role in environmental morbidity, potential effects of co-exposures, and impact on resolution biology.

It is evident that acute viral infections induce chronic inflammation even after viral clearance, which exacerbate asthma and AHR (Walter et al., 2002). The continued presence of both monocyte-derived and resident macrophages in lung tissue after resolution of influenza A or bleomycin-induced injury (Misharin et al., 2013) indicates a locally altered or maladaptive immunological response. In a similar manner, pollutant exposure that is intense and/or chronic, may disturb inflammation resolution and contribute to unresolved or partially resolved inflammation. This resultant maladapted homeostatic memory, from normal to altered physiological and/or immunological status (Feehan and Gilroy, 2019), warrants full characterization in resolution biology.

8. Summary

Lung tissue is constantly exposed to the outside environment, and initiates responses to distinct environmental agents. Diverse endogenous mediators and signaling pathways play critical roles in the dynamic process of lung inflammation and resolution. While early research efforts focused on anti-inflammatory mediators, current approaches include activation of pro-resolution pathways and SPMs, with the goal of resolving and preventing development of chronic lung inflammation. Persistent environmental insults may promote an oxidative stress-induced inflammatory nexus that interferes with resolution processes and contributes to aberrant airway remodeling and chronic lung disease. Further research efforts are needed to understand the effects of persistent environmental exposures on inflammation resolution, in order to identify intervention strategies that reduce its global impact on chronic lung disease(s).

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Division of Extramural Research and Training program of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS). We would like to thank Dr. Michael Humble at the NIEHS for his critical review of the manuscript and Ms. Lois Wyrick from NIEHS Arts and Graphics for support with generating figures.

Abbreviations:

- AA

arachidonic acid

- ARDS

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- AhR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- AHR

airway hyperresponsiveness

- AMs

alveolar macrophages

- Ang (1–7)

angiotensin peptides (1–7)

- AnxA1

annexin A1

- ALI

acute lung injury

- ALX/FPR2

formyl peptide receptor (lipoxin A4)

- AT

aspirin-triggered isomers (SPMs)

- BALF

bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- CC

C-C motif cytokines

- Cd

cadmium

- CdO

cadmium oxide

- ChemR23

resolvin E1 receptor

- CO

carbon monoxide

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CS

cigarette smoke

- CXC

chemokines (family of small cytokines C-X-C motif)

- cys-SPMs

cysteinyl conjugate SPMs (RCTRs, MCTRs, PCTRs)

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- DNMT

DNA methyltransferase

- DPA

docosapentaenoic acid

- EBCs

exhaled breath condensates

- EPA

eicosapentaenoic acid

- EVs

extracellular vesicles

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in 1 second

- FVC

forced vital capacity

- GC

glucocorticoid

- GM-CSF

granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor

- GPR32

G-protein coupled receptor 32 (resolvin D1 receptor)

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- GSH

reduced glutathione

- GSSG

oxidized glutathione (glutathione disulfide)

- H2S

hydrogen sulfide

- HAT

histone acetyltransferase

- HCl

hydrochloric acid

- HDAC2

histone deacetylase 2

- HDHA

hydroxy docosahexaenoic acid

- HIF1α

hypoxia-inducible factor 1-alpha

- HMGB1

high mobility group box protein 1

- HO1

heme oxygenase 1

- IFNγ

interferon gamma

- ILs

interleukins

- ILC2

type 2 innate lymphoid cells

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IPF

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide (endotoxin)

- LXs

lipoxins (ie: LXA4)

- LO

lipoxygenase

- LTs

leukotrienes (ie: LTB4)

- M1

proinflammatory macrophage (cytotoxic)

- M2

anti-inflammatory macrophage (wound repair) – subtypes M2a, M2b, M2c, M2d

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MaR

maresin series (MaR1–2)

- miRNAs

small, non-coding micro RNAs

- MMPs

matrix metalloproteinases

- NE

neutrophil elastase

- NFκB

nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of B cells

- NLRs

nod-like receptors

- NO

nitric oxide

- Nrf2

nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2

- O3

ozone

- p53

tumor protein p53

- PCs

phosphatidylcholines

- PD/NPD

protectin/neuroprotectin D series (PD1/NPD1, PDX)

- PGs

prostaglandins (ie: PGE2)

- 15-PGDH

15 hydroxyprostaglandin dehydrogenase

- PI3K

phosphoinositide 3-kinase

- PM

particulate matter (includes PM10, PM2.5, and PM0.1 or ultrafine particles, UFP)

- PRDX2

oxidized peroxiredoxin-2

- PRRs

pattern recognition receptors (ie: TLRs, NLRs)

- PS (PSR)

phosphatidylserine (and PS receptor)

- PUFAs

ω−3 and ω−6 polyunsaturated fatty acids, aka long chain (LC) PUFAs

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Rv

resolvin series (RvD1–6, RvE1–3, and epimers 18S-RvE1–3)

- SAA

serum amyloid A

- S1P

spingosine-1-phosphate

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- SP-D

surfactant protein D (Sftpd)

- SPMs

specialized pro-resolving mediators

- TAM

myeloproliferative syndrome transient locus

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor beta

- Th

T helper cells [ie: Th17, T regulatory (Treg)]

- Tim4

T cell immunoglobulin and mucin domain containing 4

- TIMP

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase

- TLRs

toll-like receptors

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- TRX

thioredoxin

- UFPs

ultrafine particles (PM0.1)

- WB

whole blood

- XAMPs

xenobiotic associated molecular patterns

Footnotes

Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdulnour RE, Dalli J, Colby JK, Krishnamoorthy N, Timmons JY, Tan SH, et al. , 2014. Maresin 1 biosynthesis during platelet-neutrophil interactions is organ-protective. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 111 (46), 16526–16531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghapour M, Remels AHV, Pouwels SD, Bruder D, Hiemstra PS, Cloonan SM, et al. , 2020. Mitochondria: at the crossroads of regulating lung epithelial cell function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Phys. Lung Cell. Mol. Phys. 318 (1), L149–l64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan K, Devereux G, 2011. Diet and asthma: nutrition implications from prevention to treatment. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 111 (2), 258–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almagro P, Cabrera FJ, Diez J, Boixeda R, Alonso Ortiz MB, Murio C, et al. , 2012. Comorbidities and short-term prognosis in patients hospitalized for acute exacerbation of COPD: the EPOC en Servicios de medicina interna (ESMI) study. Chest. 142 (5), 1126–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ando M, Miyazaki E, Ito T, Hiroshige S, Nureki SI, Ueno T, et al. , 2010. Significance of serum vascular endothelial growth factor level in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lung. 188 (3), 247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres J, Smith LC, Murray A, Jin Y, Businaro R, Laskin JD, et al. , 2020. Role of extracellular vesicles in cell-cell communication and inflammation following exposure to pulmonary toxicants. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 51, 12–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki H, Hisada T, Ishizuka T, Utsugi M, Kawata T, Shimizu Y, et al. , 2008. Resolvin E1 dampens airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in a murine model of asthma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 367 (2), 509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlantis E, Cochrane B, 2016. The association of dietary intake and supplementation of specific polyunsaturated fatty acids with inflammation and functional capacity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 14 (2), 53–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aztatzi-Aguilar OG, Uribe-Ramírez M, Arias-Montaño JA, Barbier O, De Vizcaya-Ruiz A, 2015. Acute and subchronic exposure to air particulate matter induces expression of angiotensin and bradykinin-related genes in the lungs and heart: Angiotensin-II type-I receptor as a molecular target of particulate matter exposure. Part. Fibre. Toxicol. 12, 17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bălă GP, Râjnoveanu RM, Tudorache E, Motișan R, Oancea C, 2021. Air pollution exposure-the (in)visible risk factor for respiratory diseases. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 28 (16), 19615–19628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PJ, Adcock IM, Ito K, 2005. Histone acetylation and deacetylation: importance in inflammatory lung diseases. Eur. Respir. J. 25 (3), 552–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros R, Moreira A, Fonseca J, Delgado L, Castel-Branco MG, Haahtela T, et al. , 2011. Dietary intake of α-linolenic acid and low ratio of n-6:n-3 PUFA are associated with decreased exhaled NO and improved asthma control. Br. J. Nutr. 106 (3), 441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayarri MA, Milara J, Estornut C, Cortijo J, 2021. Nitric oxide system and bronchial epithelium: more than a barrier. Front. Physiol. 12, 687381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker S, Mundandhara S, Devlin RB, Madden M, 2005. Regulation of cytokine production in human alveolar macrophages and airway epithelial cells in response to ambient air pollution particles: further mechanistic studies. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 207 (2 Suppl), 269–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belchamber KBR, Donnelly LE, 2017. Macrophage dysfunction in respiratory disease. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 62, 299–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevan GH, Al-Kindi SG, Brook RD, Münzel T, Rajagopalan S, 2021. Ambient air pollution and atherosclerosis: insights into dose, time, and mechanisms. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 41 (2), 628–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhavsar PK, Levy BD, Hew MJ, Pfeffer MA, Kazani S, Israel E, et al. , 2010. Corticosteroid suppression of lipoxin A4 and leukotriene B4 from alveolar macrophages in severe asthma. Respir. Res. 11 (1), 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birukov KG, Karki P, 2018. Injured lung endothelium: mechanisms of self-repair and agonist-assisted recovery (2017 Grover Conference Series). Pulm. Circ. 8 (1), 2045893217752660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bissonnette EY, Lauzon-Joset JF, Debley JS, Ziegler SF, 2020. Cross-talk between alveolar macrophages and lung epithelial cells is essential to maintain lung homeostasis. Front. Immunol. 11, 583042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackler RW, Motta JP, Manko A, Workentine M, Bercik P, Surette MG, et al. , 2015. Hydrogen sulphide protects against NSAID-enteropathy through modulation of bile and the microbiota. Br. J. Pharmacol. 172 (4), 992–1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum JL, Rosenblum LK, Grunig G, Beasley MB, Xiong JQ, Zelikoff JT, 2014. Short-term inhalation of cadmium oxide nanoparticles alters pulmonary dynamics associated with lung injury, inflammation, and repair in a mouse model. Inhal. Toxicol. 26 (1), 48–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bontinck A, Maes T, Joos G, 2020. Asthma and air pollution: recent insights in pathogenesis and clinical implications. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 26 (1), 10–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borger JG, Lau M, Hibbs ML, 2019. The influence of innate lymphoid cells and unconventional T cells in chronic inflammatory lung disease. Front. Immunol. 10, 1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bournazou I, Pound JD, Duffin R, Bournazos S, Melville LA, Brown SB, et al. , 2009. Apoptotic human cells inhibit migration of granulocytes via release of lactoferrin. J. Clin. Invest. 119 (1), 20–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozinovski S, Anthony D, Vlahos R, 2014. Targeting pro-resolution pathways to combat chronic inflammation in COPD. J. Thorac. Dis. 6 (11), 1548–1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancaleone V, Mitidieri E, Flower RJ, Cirino G, Perretti M, 2014. Annexin A1 mediates hydrogen sulfide properties in the control of inflammation. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 351 (1), 96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromberg PA, 2016. Mechanisms of the acute effects of inhaled ozone in humans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1860 (12), 2771–2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook RD, Rajagopalan S, Pope CA 3rd, Brook JR, Bhatnagar A, Diez-Roux AV, et al. , 2010. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 121 (21), 2331–2378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brüne B, 2005. The intimate relation between nitric oxide and superoxide in apoptosis and cell survival. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 7 (3–4), 497–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bubici C, Papa S, Pham CG, Zazzeroni F, Franzoso G, 2006. The NF-kappaB-mediated control of ROS and JNK signaling. Histol. Histopathol. 21 (1), 69–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers JD, Moffitt KL, Suarez-Cuartin G, Sibila O, Finch S, Furrie E, et al. , 2017. Neutrophil elastase activity is associated with exacerbations and lung function decline in bronchiectasis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 195 (10), 1384–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chávez-Galán L, Olleros ML, Vesin D, Garcia I, 2015. Much more than M1 and M2 macrophages, there are also CD169(+) and TCR(+) macrophages. Front. Immunol. 6, 263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checa J, Aran JM, 2020. Airway redox homeostasis and inflammation gone awry: from molecular pathogenesis to emerging therapeutics in respiratory pathology. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21 (23). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YH, Yao WZ, Ding YL, Geng B, Lu M, Tang CS, 2008. Effect of theophylline on endogenous hydrogen sulfide production in patients with COPD. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 21 (1), 40–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang N, Serhan CN, 2017. Structural elucidation and physiologic functions of specialized pro-resolving mediators and their receptors. Mol. Asp. Med. 58, 114–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang N, Serhan CN, 2020. Specialized pro-resolving mediator network: an update on production and actions. Essays Biochem. 64 (3), 443–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang N, Schwab JM, Fredman G, Kasuga K, Gelman S, Serhan CN, 2008. Anesthetics impact the resolution of inflammation. PLoS One 3 (4), e1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang N, Shinohara M, Dalli J, Mirakaj V, Kibi M, Choi AM, et al. , 2013. Inhaled carbon monoxide accelerates resolution of inflammation via unique proresolving mediator-heme oxygenase-1 circuits. J. Immunol. 190 (12), 6378–6388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciesielski TH, Schwartz J, Bellinger DC, Hauser R, Amarasiriwardena C, Sparrow D, et al. , 2018. Iron-processing genotypes, nutrient intakes, and cadmium levels in the normative aging study: evidence of sensitive subpopulations in cadmium risk assessment. Environ. Int. 119, 527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements PJ, 2011. Xenobiotic-induced inflammation: pathogenesis and mediators. Gen. Appl. Syst. Toxicol. 10.1002/9780470744307.gat167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Croasdell A, Thatcher TH, Kottmann RM, Colas RA, Dalli J, Serhan CN, et al. , 2015. Resolvins attenuate inflammation and promote resolution in cigarette smoke-exposed human macrophages. Am. J. Phys. Lung Cell. Mol. Phys. 309 (8), L888–L901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby LM, Waters CM, 2010. Epithelial repair mechanisms in the lung. Am. J. Phys. Lung Cell. Mol. Phys. 298 (6), L715–L731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa Loureiro L., da Costa Loureiro L., Gabriel-Junior EA, Zambuzi FA, Fontanari C, Sales-Campos H, et al. , 2020. Pulmonary surfactant phosphatidylcholines induce immunological adaptation of alveolar macrophages. Mol. Immunol. 122, 163–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Batlle J, Sauleda J, Balcells E, Gómez FP, Méndez M, Rodriguez E, et al. , 2012. Association between Ω3 and Ω6 fatty acid intakes and serum inflammatory markers in COPD. J. Nutr. Biochem. 23 (7), 817–821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Rosa X, Norris PC, Chiang N, Rodriguez AR, Spur BW, Serhan CN, 2018. Identification and complete stereochemical assignments of the new resolvin conjugates in tissue regeneration in human tissues that stimulate proresolving phagocyte functions and tissue regeneration. Am. J. Pathol. 188 (4), 950–966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson K, Stone V, Borm PJ, Jimenez LA, Gilmour PS, Schins RP, et al. , 2003. Oxidative stress and calcium signaling in the adverse effects of environmental particles (PM10). Free Radic. Biol. Med. 34 (11), 1369–1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly LE, Barnes PJ, 2012. Defective phagocytosis in airways disease. Chest. 141 (4), 1055–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffney PF, Kim HH, Porter NA, Jaspers I, 2020. Ozone-derived oxysterols impair lung macrophage phagocytosis via adduction of some phagocytosis receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 295 (36), 12727–12738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufton N, Natividad J, Verdu EF, Wallace JL, 2012. Hydrogen sulfide and resolution of acute inflammation: A comparative study utilizing a novel fluorescent probe. Sci. Rep. 2, 499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duvall MG, Levy BD, 2016. DHA- and EPA-derived resolvins, protectins, and maresins in airway inflammation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 785, 144–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eapen MS, Hansbro PM, McAlinden K, Kim RY, Ward C, Hackett TL, et al. , 2017. Abnormal M1/M2 macrophage phenotype profiles in the small airway wall and lumen in smokers and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Sci. Rep. 7 (1), 13392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckle T, Grenz A, Laucher S, Eltzschig HK, 2008. A2B adenosine receptor signaling attenuates acute lung injury by enhancing alveolar fluid clearance in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 118 (10), 3301–3315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickmeier O, Seki H, Haworth O, Hilberath JN, Gao F, Uddin M, et al. , 2013. Aspirin-triggered resolvin D1 reduces mucosal inflammation and promotes resolution in a murine model of acute lung injury. Mucosal Immunol. 6 (2), 256–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elonheimo HM, Mattila T, Andersen HR, Bocca B, Ruggieri F, Haverinen E, et al. , 2022. Environmental substances associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-a scoping review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19 (7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falcon-Rodriguez CI, Osornio-Vargas AR, Sada-Ovalle I, Segura-Medina P, 2016. Aeroparticles, composition, and lung diseases. Front. Immunol. 7, 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feehan KT, Gilroy DW, 2019. Is resolution the end of inflammation? Trends Mol. Med. 25 (3), 198–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fekete M, Szőllősi G, Németh AN, Varga JT, 2021. Clinical value of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Orv. Hetil. 162 (1), 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Gao D, Liao F, Zhou F, Wang X, 2016. The health effects of ambient PM2.5 and potential mechanisms. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 128, 67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fettel J, Kühn B, Guillen NA, Sürün D, Peters M, Bauer R, et al. , 2019. Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) induces potent anti-inflammatory effects in vitro and in vivo by S1P receptor 4-mediated suppression of 5-lipoxygenase activity. FASEB J. 33 (2), 1711–1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Files DC, Gibbs KW, Schaich CL, Collins SP, Gwathmey TM, Casey JD, et al. , 2021. A pilot study to assess the circulating renin-angiotensin system in COVID-19 acute respiratory failure. Am. J. Phys. Lung Cell. Mol. Phys. 321 (1), L213–l8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel T, 2011. Signal transduction by reactive oxygen species. J. Cell Biol. 194 (1), 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flesher RP, Herbert C, Kumar RK, 2014. Resolvin E1 promotes resolution of inflammation in a mouse model of an acute exacerbation of allergic asthma. Clin. Sci. (Lond.) 126 (11), 805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritscher LG, Post M, Rodrigues MT, Silverman F, Balter M, Chapman KR, et al. , 2012. Profile of eicosanoids in breath condensate in asthma and COPD. J. Breath Res. 6 (2), 026001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullerton JN, Gilroy DW, 2016. Resolution of inflammation: a new therapeutic frontier. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 15 (8), 551–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fussbroich D, Colas RA, Eickmeier O, Trischler J, Jerkic SP, Zimmermann K, et al. , 2020. A combination of LCPUFA ameliorates airway inflammation in asthmatic mice by promoting pro-resolving effects and reducing adverse effects of EPA. Mucosal Immunol. 13 (3), 481–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganesan R, Henkels KM, Shah K, De La Rosa X, Libreros S, Cheemarla NR, et al. , 2020. D-series Resolvins activate Phospholipase D in phagocytes during inflammation and resolution. FASEB J. 34 (12), 15888–15906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangopadhyay S, Vijayan VK, Bansal SK, 2012. Lipids of erythrocyte membranes of COPD patients: a quantitative and qualitative study. Copd. 9 (4), 322–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangwar RS, Bevan GH, Palanivel R, Das L, Rajagopalan S, 2020. Oxidative stress pathways of air pollution mediated toxicity: Recent insights. Redox Biol. 34, 101545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghezzi P, Floridi L, Boraschi D, Cuadrado A, Manda G, Levic S, et al. , 2018. Oxidative stress and inflammation induced by environmental and psychological stressors: a biomarker perspective. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 28 (9), 852–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghio AJ, Silbajoris R, Carson JL, Samet JM, 2002. Biologic effects of oil fly ash. Environ. Health Perspect. 110 (Suppl. 1), 89–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gipson TS, Bless NM, Shanley TP, Crouch LD, Bleavins MR, Younkin EM, et al. , 1999. Regulatory effects of endogenous protease inhibitors in acute lung inflammatory injury. J. Immunol. 162 (6), 3653–3662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Go YM, Orr M, Jones DP, 2013. Increased nuclear thioredoxin-1 potentiates cadmium-induced cytotoxicity. Toxicol. Sci. 131 (1), 84–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobbetti T, Cooray SN, 2016. Annexin A1 and resolution of inflammation: tissue repairing properties and signalling signature. Biol. Chem. 397 (10), 981–993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves AM, Gow AJ, Massa CB, Laskin JD, Laskin DL, 2012. Prolonged injury and altered lung function after ozone inhalation in mice with chronic lung inflammation. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 47 (6), 776–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Günther A, Korfei M, Mahavadi P, von der Beck D, Ruppert C, Markart P, 2012. Unravelling the progressive pathophysiology of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 21 (124), 152–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C, Lv S, Liu Y, Li Y, 2021. Biomarkers for the adverse effects on respiratory system health associated with atmospheric particulate matter exposure. J. Hazard. Mater. 421, 126760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hachicha M, Pouliot M, Petasis NA, Serhan CN, 1999. Lipoxin (LX)A4 and aspirin-triggered 15-epi-LXA4 inhibit tumor necrosis factor 1alpha-initiated neutrophil responses and trafficking: regulators of a cytokine-chemokine axis. J. Exp. Med. 189 (12), 1923–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadzic S, Wu CY, Avdeev S, Weissmann N, Schermuly RT, Kosanovic D, 2020. Lung epithelium damage in COPD - An unstoppable pathological event? Cell. Signal. 68, 109540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harari S, Raghu G, Caminati A, Cruciani M, Franchini M, Mannucci P, 2020. Fibrotic interstitial lung diseases and air pollution: a systematic literature review. Eur. Respir. Rev. 29 (157). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding JN, Gross M, Patel V, Potter S, Cormier SA, 2021. Association between particulate matter containing EPFRs and neutrophilic asthma through AhR and Th17. Respir. Res. 22 (1), 275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan RA, O’Brien E, Mancuso P, 2012. Lipoxin A(4) and 8-isoprostane in the exhaled breath condensate of children hospitalized for status asthmaticus. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 13 (2), 141–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haskó G, Cronstein BN, 2004. Adenosine: an endogenous regulator of innate immunity. Trends Immunol. 25 (1), 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haworth O, Cernadas M, Yang R, Serhan CN, Levy BD, 2008. Resolvin E1 regulates interleukin 23, interferon-gamma and lipoxin A4 to promote the resolution of allergic airway inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 9 (8), 873–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headland SE, Norling LV, 2015. The resolution of inflammation: principles and challenges. Semin. Immunol. 27 (3), 149–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heukels P, Moor CC, von der Thüsen JH, Wijsenbeek MS, Kool M, 2019. Inflammation and immunity in IPF pathogenesis and treatment. Respir. Med. 147, 79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinz B, Phan SH, Thannickal VJ, Galli A, Bochaton-Piallat ML, Gabbiani G, 2007. The myofibroblast: one function, multiple origins. Am. J. Pathol. 170 (6), 1807–1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota N, Martin JG, 2013. Mechanisms of airway remodeling. Chest. 144 (3), 1026–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge S, Matthews G, Mukaro V, Ahern J, Shivam A, Hodge G, et al. , 2011. Cigarette smoke-induced changes to alveolar macrophage phenotype and function are improved by treatment with procysteine. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 44 (5), 673–681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou T, Chen Q, Ma Y, 2021. Elevated expression of miR-146 involved in regulating mice pulmonary dysfunction after exposure to PM2.5. J. Toxicol. Sci. 46 (10), 437–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao HM, Sapinoro RE, Thatcher TH, Croasdell A, Levy EP, Fulton RA, et al. , 2013. A novel anti-inflammatory and pro-resolving role for resolvin D1 in acute cigarette smoke-induced lung inflammation. PLoS One 8 (3), e58258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imboden M, Kumar A, Curjuric I, Adam M, Thun GA, Haun M, et al. , 2015. Modification of the association between PM10 and lung function decline by cadherin 13 polymorphisms in the SAPALDIA cohort: a genome-wide interaction analysis. Environ. Health Perspect. 123 (1), 72–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Ito M, Elliott WM, Cosio B, Caramori G, Kon OM, et al. , 2005. Decreased histone deacetylase activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 352 (19), 1967–1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaén RI, Sánchez-García S, Fernández-Velasco M, Boscá L, Prieto P, 2021. Resolution-based therapies: the potential of lipoxins to treat human diseases. Front. Immunol. 12, 658840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaudszus A, Mainz JG, Pittag S, Dornaus S, Dopfer C, Roth A, et al. , 2016. Effects of a dietary intervention with conjugated linoleic acid on immunological and metabolic parameters in children and adolescents with allergic asthma–a placebo-controlled pilot trial. Lipids Health Dis. 15, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang G, Xu L, Song S, Zhu C, Wu Q, Zhang L, et al. , 2008. Effects of long-term low-dose cadmium exposure on genomic DNA methylation in human embryo lung fibroblast cells. Toxicology. 244 (1), 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X, Xu F, Qiu X, Shi X, Pardo M, Shang Y, et al. , 2019. Hydrophobic organic components of ambient fine particulate matter (PM(2.5)) associated with inflammatory cellular response. Environ. Sci. Technol. 53 (17), 10479–10486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Zhao Y, Wang Q, Chen H, Zhou X, 2020. Fine particulate matter exposure promotes M2 macrophage polarization through inhibiting histone deacetylase 2 in the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann. Transl. Med. 8 (20), 1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannson KA, Balmes JR, Collard HR, 2015. Air pollution exposure: a novel environmental risk factor for interstitial lung disease? Chest. 147 (4), 1161–1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Julia C, Touvier M, Meunier N, Papet I, Galan P, Hercberg S, et al. , 2013. Intakes of PUFAs were inversely associated with plasma C-reactive protein 12 years later in a middle-aged population with vitamin E intake as an effect modifier. J. Nutr. 143 (11), 1760–1766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazani S, Planaguma A, Ono E, Bonini M, Zahid M, Marigowda G, et al. , 2013. Exhaled breath condensate eicosanoid levels associate with asthma and its severity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 132 (3), 547–553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keatings VM, Collins PD, Scott DM, Barnes PJ, 1996. Differences in interleukin-8 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in induced sputum from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 153 (2), 530–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierstein S, Poulain FR, Cao Y, Grous M, Mathias R, Kierstein G, et al. , 2006. Susceptibility to ozone-induced airway inflammation is associated with decreased levels of surfactant protein D. Respir. Res. 7 (1), 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilburg-Basnyat B, Reece SW, Crouch MJ, Luo B, Boone AD, Yaeger M, et al. , 2018. Specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators regulate ozone-induced pulmonary and systemic inflammation. Toxicol. Sci. 163 (2), 466–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KH, Park TS, Kim YS, Lee JS, Oh YM, Lee SD, et al. , 2016. Resolvin D1 prevents smoking-induced emphysema and promotes lung tissue regeneration. Int. J. Chron. Obstruct. Pulmon. Dis. 11, 1119–1128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]