Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the preventive efficacy of an extended version of the Knee Control injury prevention exercise programme (IPEP) compared with an adductor strength programme and to a comparison group using a self-selected IPEP in amateur adolescent and adult male and female football players.

Methods

Two-armed cluster-randomised trial with an additional non-randomised arm. All 251 amateur teams (players 14–46 years) in one regional football district were approached. Teams meeting inclusion criteria were randomised to (1) extended Knee Control or (2) an adductor strength programme. Teams already using an IPEP were allocated to a comparison group and received no new intervention. Players responded to weekly questionnaires about football exposures and injuries during a 7-month season.

Results

Seventeen teams in the extended Knee Control, 12 in the adductor and 17 in the comparison group participated, with 502 players. For the primary outcomes, no difference in injury incidence in three lower-limb injury locations combined (hamstring, knee and ankle) was seen between extended Knee Control and the adductor group, whereas extended Knee Control had 29% lower incidence than the comparison group (incidence rate ratio 0.71, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.98). No between-group differences in groin injury incidence were seen. The weekly injury prevalence rates in the three lower limb locations combined (hamstring, knee and ankle) were 17% lower (prevalence rate ratio (PRR) 0.83, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.00) and 26% lower (PRR 0.74, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.87) in extended Knee Control compared with the adductor and comparison groups, respectively.

Conclusion

No difference in injury incidence was seen between the extended Knee Control and the adductor programme whereas extended Knee Control reduced injury incidence by nearly one-third compared with a self-selected IPEP. Players in extended Knee Control had lower injury prevalence compared with an adductor or self-selected IPEP.

Trial registration number

NCT04272047; Clinical trials.

Keywords: Lower extremity, Preventive Medicine, Soccer, Sporting injuries, Athletic Injuries

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

General injury prevention exercise programmes may reduce injury rates in adolescent and adult football players.

The Adductor Strengthening Programme reduced groin injury rates in subelite male football players in a previous study.

Effectiveness of injury prevention exercise programmes is generally lower than the preventive efficacy shown in randomised controlled trials.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

Players who performed an extended version of the Knee Control programme had approximately one-third lower incidence of injuries to the hamstring, knee or ankle compared with a comparison group that conducted self-selected prevention exercises in adolescent and adult male and female amateur football players.

Players who used extended Knee Control had one-fifth to one-fourth lower prevalence of injuries to the hamstring, knee or ankle compared with the adductor and the comparison group

Players using the adductor strength programme had no reduction in incidence or prevalence of groin injuries compared with the other groups.

Players who used extended Knee Control had lower incidence of overall time-loss injuries and lower prevalence of substantial injuries than the adductor and comparison group.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

Teams using injury prevention exercise programmes may need more support to ensure an optimal training dosage and progression in order to maximise the preventive effect.

The extended Knee Control programme seems feasible for continued use within male and female amateur adolescent and adult football.

Continuous support may be needed to ensure that injury prevention exercise programmes are maintained during a full season and over subsequent seasons.

Introduction

General injury prevention exercise programmes (IPEPs) such as the Knee Control programme,1–3 the 11+ 4–6 and similar IPEPs7–10 focusing on lower limb balance, strength and muscle control, reduce the rate of acute lower extremity injuries in team sports. However, achieving broad-scale effectiveness of IPEPs is challenging.11 Coaches often modify programme content or dosage, potentially limiting the preventive effectiveness.12–14 We developed an extended version of the Knee Control programme, extended Knee Control, with the same six main exercises as in the original Knee Control programme but with more exercise variations to increase programme fidelity by offering greater variation of exercises, better fit and increased possibility for exercise progressions for football players at various proficiency levels.

Short-focused IPEPs, such as the Adductor Strengthening Programme, reduced the rate of groin injuries among male sub-elite football players by 41%,15 but the preventive efficacy in other settings is unknown.

The aim was to evaluate preventive efficacy of the extended Knee Control programme compared with an adductor strength programme and to a comparison group using a self-selected IPEP in amateur adolescent and adult male and female football players. The preventive efficacy of extended Knee Control has not been evaluated before. Our hypotheses were that: (1) extended Knee Control would show superior preventive effects on hamstring, knee and ankle injuries and (2) the adductor programme would show superior preventive effects on groin injuries.

Materials and methods

Design

This was a two-armed cluster-randomised trial with an additional non-randomised comparison arm. Teams in the randomised groups had not used injury prevention exercises regularly the previous season and were allocated to one of two interventions: Extended Knee Control focusing on lower extremity injuries in general, or an adductor programme focusing on groin injuries. The non-randomised comparison group comprised teams that already used an IPEP. Initially, as registered in the study protocol, we intended to include teams that used Knee Control 1 2 as comparison group. During inclusion it became apparent that many teams used modifications of the Knee Control programme, hence, we broadened the inclusion criteria to better reflect the reality. The study was single blinded with physiotherapists collecting injury data blinded to group allocation. The study covered one 7-month season from March to October/November 2020. The study complied with the declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The study has been checked against the CONSORT 2010 checklist, applicable parts of the CONSORT extension for cluster trials16 and the CONSERVE 2021 statement.17

Important modifications due to the COVID-19 pandemic

The competitive season was shortened with the start postponed from April to June 2020, and the pre-season correspondingly extended. On 1 April 2020, social distancing was recommended by the Public Health Agency of Sweden and was supported by the Swedish Football Association and the regional football districts. We, therefore, added two exercises to the adductor programme, as described under the Interventions section and table 1.

Table 1.

Programme descriptions

| Extended Knee Control | Adductor programme | |

| Exercises | Running warm-up (5 min) 6 main strengthening and neuromuscular control exercises (10 variations for each) (10–15 min):

Of these, 44 are individual exercises, including 6 with a resistance band and 16 partner exercises |

One exercise out of:

|

| Frequency | Every training session throughout the season. Running warm-up before matches. | 2–3 times/week pre-season 1 time/week competitive season |

| Dosage | 30–60 s per exercise 2 sets |

3–5 to 12–15 repetitions (Copenhagen adduction and Side-lying adduction) or 10 s maximal isometric contractions × 5 repetitions (Adductor squeeze) 1 set |

| Recommendations about progression | Start at a level that offered sufficient challenge to the players and to progress to more demanding exercises over time. Important that the exercises were done with proper technique before progressing. | Start with Copenhagen adduction long lever. Players unable to perform the exercise with correct technique, prescribed dosage, or who experienced pain >3 on a 0–10 numerical rating scale were recommended to use an easier exercise variant. Adductor squeeze recommended as alternative exercises to avoid close player-to-player contact. Progression mainly through more repetitions during preseason |

| Equipment | Football, resistance band for some exercises | Football (adductor squeeze) |

| Setup | Before training, as a warm-up, imbedded in the training, after training or a combination of these | Before or after training |

Study population and recruitment

Inclusion criteria for the randomised groups were teams (1) participating in the adolescent or adult 2020 series (male 5th–8th leagues (out of 8 leagues), female 3rd–5th leagues (out of 5 leagues), male and female 16–19 series) in one regional district (Östergötland, Sweden), (2) with at least two scheduled training sessions per week, (3) that had not used an IPEP regularly the previous year. Inclusion criteria 1 and 2 were identical for the comparison group, but these teams had used an IPEP regularly (at least once per week) the previous year and planned to continue in the 2020 season. All players 14 years and older were eligible.

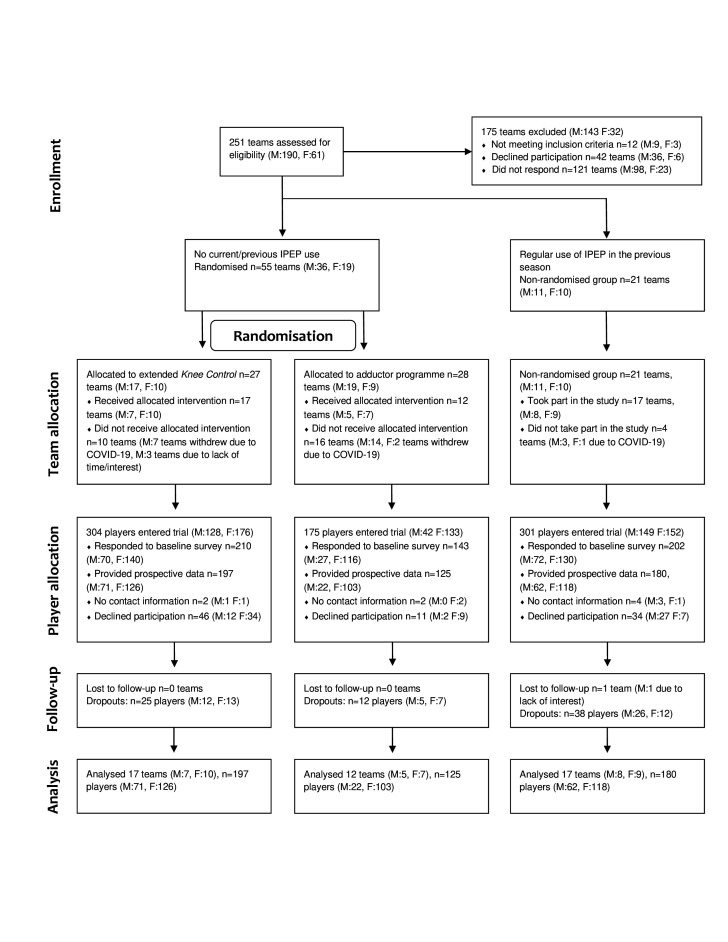

Coaches for eligible teams (n=251) were approached via e-mail and telephone (figure 1) and received oral and written information before accepting participation. Coaches for all participating teams were interviewed by telephone regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria and specifically their use of IPEPs to ascertain the right group allocation (randomised or non-randomised arm). In teams where the coach had accepted participation, players (and guardians for players <15 years) received written information about the study. Response to the questionnaires (baseline and/or weekly) was taken as consent to participate.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram over the inclusion and exclusion of teams and players in the study. F, female; IPEP, injury prevention exercise programme; M, male.

Randomisation

Eligible teams were cluster-randomised with the club as cluster unit, that is, all teams of the same sex in the same club were randomised to the same intervention to minimise risk of contamination. Randomisation was performed by a statistician and stratified by sex and league.

Interventions

For the randomised groups, coaches and player representatives for each team were invited to practical workshops where the intervention was introduced. Thereafter, coaches led the injury prevention training with their teams. Due to the pandemic, only two workshops were carried out before group gatherings were discouraged. Site visits where the intervention was introduced were made in the remaining teams (n=9), except one team that only received written material and information about the adductor programme via telephone. The workshops were led by two of the main researchers (HL or MH) together with a team of physiotherapists. These physiotherapists also led the practical sessions during site visits. Programme material was offered in written format (folder with pictures and instructions for each exercise) and digitally on a webpage (videos and instructions for each exercise). Teams were recommended to start with their intervention immediately after the workshop/site visit and to use the intervention throughout the season. Coaches were contacted via telephone 1 month after introduction to support training progress.

No workshops or information material were offered to the comparison group. At baseline, coaches from eight teams in the comparison group reported use of the Knee Control programme, the others used various self-selected exercises. The teams were instructed to carry on with their usual training throughout the season.

Extended Knee Control programme

Extended Knee Control included a running warm-up and six main exercises targeting muscle strength and neuromuscular control with 10 different variations/progression levels for each exercise (table 1, online supplemental material). The programme was built on the Knee Control programme (with 30 exercise options)1 but had 30 additional exercise options, that is, five extra for each main exercise. Some of the added exercises were easier, to fit younger players, and some were more demanding to fit adult players.

bjsports-2022-105890supp001.pdf (13.2MB, pdf)

Adductor strength programme

The adductor programme was initially identical to the Adductor Strengthening Programme with one exercise on three levels of difficulty (table 1).15 Due to the pandemic, two adductor squeeze exercises18 were added as an alternative to avoid close contact between players.

Data collection

Players responded to baseline and follow-up questionnaires on the use and experience of the IPEPs and adverse events (follow-up questionnaire), most of these data will be presented elsewhere. They also responded to weekly questionnaires about occurrence of injury in any body location based on the Oslo Sports Trauma Research Center (OSTRC) questionnaire (OSTRC-O2),19 and exposure to training and matches. Players responded to 1–28 questions per week. When the player reported new injury, additional questions were given regarding nature of the health problem. Injuries were defined in line with the International Olympic Committee consensus statement20 and covered any physical complaint injuries (irrespective of need of medical attention or time-loss), sudden-onset and gradual-onset injuries, time-loss injury (injury with reduced participation or absence from football training and/or matches as reported in question 1 of the OSTRC-O2) and medical attention injury (injury where the player sought medical advice or treatment). Substantial injury was defined as an injury with moderate or severe modifications in participation in football training and matches and/or moderate or severe effects on football performance, or inability to participate in football.19

One coach per team responded to weekly questionnaires throughout the season and reported number of team matches and training sessions, number of IPEP sessions and timing of IPEP use (before training, during warm-up, imbedded in training, after training, before matches). Players reported which days the IPEP was used in their weekly questionnaires.

All questionnaires were distributed via online software (esMakerNX3 V.3.0) on each Sunday evening with reminders on Tuesday and Thursday the week after. Players who reported time-loss or substantial injury to the groin or hamstrings (sudden-onset or gradual-onset), knee or ankle (sudden-onset) were contacted via telephone by a study physiotherapist who asked about the injury and filled in a standard injury report form. Players could report multiple injuries each week.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were any physical complaint injury to either of three lower limb injury locations: hamstring, knee or ankle (hypothesis 1) or to the groin (hypothesis 2). Secondary outcomes were all physical complaint injuries irrespective of location, time-loss injuries, sudden-onset or gradual-onset injuries, substantial and medical attention injuries, adverse events, team and player compliance.

Injury incidence rate (IR) was expressed as the number of new and recurrent injury events per 1000 football hours. All sudden-onset injuries occurring during football training or matches and all gradual-onset injuries regardless of whether symptoms first appeared during football or other activities were included. Weekly injury prevalence rate (PR) was expressed as number of player reports where a player reported new or ongoing injury divided by the total number of eligible player reports that same week.

Compliance to the interventions was described as the weekly dosage based on coach (team compliance) and player weekly reports (player compliance).

Statistical analyses

An a priori sample size calculation showed that for hypothesis 1, 252 players would be needed based on the assumption that 80% of players would report at least one injury during the season according to the study by Thorborg et al, on the 11 and 11+ programmes21 a 40% reduction in injury rate in extended Knee Control compared with the other groups, and adjusting for clustering effect (estimated design effect 1.28).

For hypothesis 2, 301 players would be needed based on the assumption that 67% of players would report a groin injury during the season according to the study by Harøy et al, on the Adductor Strengthening Programme 15 and similar injury reduction and design effect as above. With an expected dropout rate of 30%, we aimed to recruit 391 players (approximately 26 teams).

Baseline data are presented descriptively. IR and weekly PR are presented with 95% CI, and incidence and prevalence rate ratios (IRR, PRR) were calculated and compared between all three groups (according to intention-to-treat) using generalised linear models with Poisson distribution, log link and the natural logarithm of total exposure hours or total eligible weeks as offset denominator variables. All data collected from teams and players who dropped out were included in the analyses. Due to uneven sex distribution between groups, all analyses were sex-adjusted. In these calculations, contusions were excluded in line with Waldén et al,1 since we did not expect that the programmes would prevent these injuries. Sex-separated data were reported descriptively. Absolute rate reduction (ARR) was calculated as a crude estimate of the IR difference for the primary outcome using Poisson distribution and model-based methods to construct 95% CI. Numbers needed to treat (NNT) with 95% CI was calculated as the inverted ARR.22 The primary outcomes for incidence and prevalence were tested with regards to cluster effect. Since model fit did not improve, the cluster effect was deemed negligible, and all results are presented without consideration of clustering. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (V.27.0. Armonk, New York) was used for all analyses. An experienced statistician was mainly responsible for preparing the databases and analysing data.

Patient and public involvement

Extended Knee Control programme development was informed by a qualitative study with coaches,13 and pilot-tested with coaches and players.23

Results

Nineteen clusters with 29 teams were allocated to the randomised groups and received their intervention, 13 clusters with 17 teams were included in the comparison group. In total, 780 players in these 46 teams were eligible, and 502 players (14–46 years) completed the study (table 2). Another 30 teams first accepted participation but withdrew before study commencement without contributing any data. In total, participation rate was 18% of potentially eligible teams.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics for included players (n=502)

| Extended Knee Control (n=197) | Adductor programme (n=125) | Comparison group (n=180) | |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 19.3±5.0 | 20.5±5.8 | 20.5±6.3 |

| Sex, n male; female (% male) | 71;126 (36.0) | 22;103 (17.6) | 62;118 (34.4) |

| Response to baseline questionnaire presented below* | n=178 responses | n=120 responses | n=164 responses |

| Participating in other sports, n (%) | 40 (22.5) | 30 (25.0) | 33 (20.1) |

| Estimation of training volume, median (IQR) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Estimation of training load, median (IQR) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Current injury/complaint, ankle, n (%) | 24 (13.5) | 24 (20.0) | 25 (15.2) |

| Previous injury/complaint, ankle, n (%) | 70 (39.3) | 37 (30.8) | 67 (40.9) |

| Current injury/complaint, knee, n (%) | 28 (15.7) | 27 (22.5) | 34 (20.7) |

| Previous injury/complaint, knee, n (%) | 74 (41.6) | 41 (34.2) | 61 (37.2) |

| Current injury/complaint, hamstrings, n (%) | 9 (5.1) | 5 (4.2) | 13 (7.9) |

| Previous injury/complaint, hamstrings, n (%) | 41 (23.0) | 20 (16.7) | 31 (18.9) |

| Current injury/complaint, groin, n (%) | 21 (11.8) | 6 (5.0) | 13 (7.9) |

| Previous injury/complaint, groin, n (%) | 54 (30.3) | 38 (31.7) | 47 (28.7) |

Estimation of training volume and training load was made on a 1–7 Likert scale, where 1 represents low and 7 high-training volume or load (amount of training and intensity of training). Current and previous complaints describe the number of players who, at baseline, indicated current or previous complaints in the location of interest.

*Missing data from 19 players in extended Knee Control, 5 players in the adductor group and 16 players in the comparison group who did not respond to the baseline questionnaire.

In total, 6601 weekly player reports were collected. The average weekly response rate was 64.8% (men 55.7%, women 68.1%), 68.0% in extended Knee Control (men: 56.1%, women 73.8%), 60.4% in the adductor (men 53.8%, women 61.5%) and 64.4% in the comparison group (men 55.9%, women 67.8%).

Exposure and injury characteristics

Exposure to training and matches is presented in online supplemental table 1. In total, 458 unique injury events were reported (514 injury locations) in 279 players (online supplemental tables 1,2). Of these 458 injury events, 412 (90%) affected one body location, 39 (8.5%) two and 7 (1.5%) ≥ three locations. Of all injuries, 261 (57%) resulted in time loss.

bjsports-2022-105890supp002.pdf (87.3KB, pdf)

bjsports-2022-105890supp003.pdf (63.3KB, pdf)

Compliance

Team compliance during pre-season was 2.3, 1.7 and 1.9 sessions per week for the extended Knee Control, adductor and comparison groups (online supplemental table 1). Corresponding figures for the competitive season (summer break excluded) were 2.1, 0.7 and 2.1 sessions per week. Players in extended Knee Control used the IPEP 1.6 times/week on average, the adductor group 1.0 and the comparison group 1.4.

Intervention effect on the incidence of football injuries

For the primary outcomes, no difference in injury IR in the three lower-limb locations combined (hamstring, knee and ankle) was seen between the extended Knee Control and the adductor group, whereas extended Knee Control had 29% lower incidence (IRR 0.71, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.98) than the comparison group (table 3). The ARR between extended Knee Control and the comparison group was 3.2 (95% CI 0.3 to 6.1) injuries/1000 hours and the NNT was 316 (95% CI 165 to 3620) hours, meaning that to prevent one injury approximately seven players must perform extended Knee Control during one season. No differences in groin injury incidence were seen between groups. For secondary outcomes, time-loss injury incidence was 42% and 48% lower in extended Knee Control compared with the adductor and comparison groups.

Table 3.

Injury incidence rates per intervention group and sex-adjusted pair-wise incidence rate ratios between groups

| Extended Knee Control (1) | Adductor programme (2) | Comparison group (3) |

(1) vs (2) | (1) vs (3) | (2) vs (3) | |

| IR (95% CI) | IR (95% CI) | IR (95% CI) | IRR (95% CI) p value | IRR (95% CI) p value | IRR (95% CI) p value | |

| Primary outcomes | ||||||

| Three lower-limb locations combined* | 7.72 (6.18 to 9.66) | 9.36 (7.01 to 12.50) | 10.89 (8.72 to 13.59) | 0.80 (0.55 to 1.17) p=0.246 | 0.71 (0.52 to 0.98) p=0.036 | 0.80 (0.55 to 1.15) p=0.226 |

| Groin | 2.01 (1.29 to 3.11) | 2.85 (1.69 to 4.81) | 2.37 (1.47 to 3.82) | 0.58 (0.29 to 1.18) p=0.134 | 0.83 (0.43 to 1.58) p=0.564 | 1.20 (0.58 to 2.46) p=0.626 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Hamstring | 1.60 (0.98 to 2.62) | 1.02 (0.42 to 2.45) | 2.37 (1.47 to 3.82) | 1.45 (0.52 to 4.04) p=0.480 | 0.67 (0.34 to 1.33) p=0.254 | 0.41 (0.15 to 1.12) p=0.083 |

| Knee | 4.01 (2.94 to 5.47) | 3.66 (2.31 to 5.82) | 5.02 (3.62 to 6.97) | 1.09 (0.62 to 1.92) p=0.766 | 0.81 (0.51 to 1.27) p=0.351 | 0.65 (0.37 to 1.15) p=0.140 |

| Ankle | 2.11 (1.37 to 3.23) | 4.88 (3.27 to 7.29) | 4.05 (2.81 to 5.82) | 0.42 (0.23 to 0.76) p=0.005 | 0.53 (0.30 to 0.92) p=0.025 | 1.13 (0.65 to 1.96) p=0.661 |

| All physical complaints | 17.15 (14.76 to 19.92) | 23.20 (19.31 to 27.88) | 24.14 (20.80 to 28.02) | 0.73 (0.58 to 0.93) p=0.012 | 0.71 (0.58 to 0.88) p=0.002 | 0.94 (0.74 to 1.19) p=0.602 |

| Sudden-onset | 7.72 (6.18 to 9.66) | 11.81 (9.13 to 15.27) | 11.58 (9.34 to 14.36) | 0.63 (0.44 to 0.89) p=0.009 | 0.67 (0.49 to 0.91) p=0.011 | 1.03 (0.73 to 1.45) p=0.872 |

| Gradual-onset | 9.03 (7.34 to 11.10) | 10.79 (8.24 to 14.12) | 11.58 (9.34 to 14.36) | 0.85 (0.60 to 1.20) p=0.363) | 0.78 (0.58 to 1.05) p=0.107 | 0.87 (0.62 to 1.24) p=0.444 |

| Time-loss | 8.12 (6.53 to 10.10) | 13.64 (10.73 to 17.33) | 15.77 (13.11 to 18.96) | 0.58 (0.42 to 0.81) p=0.001 | 0.52 (0.39 to 0.69) p=0.001 | 0.85 (0.63 to 1.16) p=0.307 |

| Medical attention | 4.41 (3.28 to 5.93) | 5.90 (4.10 to 8.49) | 5.58 (4.09 to 7.61) | 0.69 (0.43 to 1.12) p=0.138 | 0.79 (0.51 to 1.21) p=0.272 | 0.97 (0.60 to 1.58) p=0.907 |

Injury incidence rate is reported per 1000 hours of football play. Incidence rates are unadjusted, whereas incidence rate ratios are adjusted for sex. Total exposure in extended Knee Control 9971 hours, adductor 4913 hours, comparison group 7165 hours.

*Injuries to any of the following locations: hamstring, knee or ankle. There were 77, 46 and 78 unique injury events to either of these three lower-limb injury locations, and 20, 14, 17 to the groin, in the extended Knee Control, adductor and comparison groups, respectively.

IR, incidence rate; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Intervention effect on the prevalence of football injuries

For the primary outcomes, injury PR in the three lower limb locations combined were 17% lower (PRR 0.83, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.00) and 26% lower (PRR 0.74, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.87) in extended Knee Control compared with the adductor and comparison groups. The adductor group had higher prevalence of groin injury than both other groups. For secondary outcomes, the prevalence of substantial injuries was 27% and 26% lower in extended Knee Control than in the adductor and comparison groups (table 4).

Table 4.

Weekly prevalence of injuries per intervention group and pair-wise prevalence rate ratios between groups

| Extended Knee Control (1) | Adductor programme (2) | Comparison group (3) |

(1) vs (2) | (1) vs (3) | (2) vs (3) | |

| PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PR (95% CI) | PRR (95% CI) p value | PRR (95% CI) p value | PRR (95% CI) p value | |

| Primary outcomes | ||||||

| Three lower-limb locations combined* | 10.87 (9.64 to 12.25) | 13.45 (11.67 to 15.50) | 14.76 (13.15 to 16.57) | 0.83 (0.69 to 1.00) p=0.048 | 0.74 (0.63 to 0.87) p<0.001) |

0.87 (0.72 to 1.05) p=0.143 |

| Groin | 3.19 (2.55 to 3.98) | 4.08 (3.16 to 5.28) | 2.26 (1.68 to 3.03) | 0.59 (0.42 to 0.83) p=0.003 | 1.39 (0.96 to 2.01) p=0.082 |

2.07 (1.39 to 3.09) p<0.001 |

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||

| Hamstring | 1.47 (1.06 to 2.04) | 2.25 (1.59 to 3.19) | 3.74 (2.97 to 4.71) | 0.63 (0.39 to 1.02) p=0.059 | 0.39 (0.26 to 0.58) p<0.001 |

0.62 (0.41 to 0.94) p=0.025 |

| Knee | 5.96 (5.07 to 7.01) | 7.11 (5.85 to 8.64) | 6.46 (5.42 to 7.69) | 0.90 (0.69 to 1.16) p=0.395 | 0.93 (0.74 to 1.19) p=0.571 | 1.03 (0.79 to 1.34) p=0.850 |

| Ankle | 3.47 (2.81 to 4.29) | 4.58 (3.59 to 5.84) | 5.13 (4.21 to 6.24) | 0.75 (0.54 to 1.04) p=0.082 | 0.68 (0.51 to 0.91) p=0.009 | 0.85 (0.62 to 1.17) p=0.314 |

| All physical complaints | 22.26 (20.47 to 24.21) | 27.82 (25.20 to 30.70) | 28.09 (25.83 to 30.54) | 0.81 (0.71 to 0.93) p=0.002 | 0.80 (0.71 to 0.90) p<0.001 |

1.00 (0.85 to 1.10) p=0.627 |

| Sudden-onset | 9.56 (8.41 to 10.87) | 11.06 (9.46 to 12.93) | 10.66 (9.31 to 12.21) | 0.90 (0.73 to 1.10) p=0.290 | 0.90 (0.75 to 1.08) p=0.256 | 1.06 (0.86 to 1.31) p=0.599 |

| Gradual-onset | 11.93 (10.64 to 13.38) | 15.49 (13.58 to 17.68) | 15.63 (13.97 to 17.49) | 0.77 (0.64 to 0.92) p=0.004 | 0.77 (0.65 to 0.90) p=0.001 | 0.94 (0.79 to 1.12) p=0.497 |

| Substantial | 12.21 (10.91 to 13.68) | 16.41 (14.43 to 18.66) | 16.45 (14.75 to 18.36) | 0.73 (0.61 to 0.87) p<0.001 |

0.74 (0.64 to 0.87) p<0.001 |

0.99 (0.83 to 1.17) p=0.898 |

Prevalence rates are unadjusted, whereas prevalence rate ratios are adjusted for sex. Total eligible weeks in extended Knee Control 2448, adductor 1420, comparison group 1951 weeks.

*Injuries to any of the following locations: hamstring, knee or ankle.

PR, prevalence rate; PRR, prevalence rate ratio.

Adverse events

At follow-up, 13 (10.8%), 15 (23.4%) and 21 (20.0%) of the players in the extended Knee Control, adductor and comparison groups, who responded to the post season surveys, reported episodes of pain or discomfort when performing injury prevention exercises. Pain intensity during the exercises was rated as 5.0, 3.0 and 3.5 in the respective group on a 0–10 numerical rating scale, where 10 represented the worst imaginable pain.

Discussion

The principal finding of this cluster-randomised trial was that hypothesis 1 was confirmed; players in extended Knee Control had 29% lower injury incidence in the three lower-limb injury locations (hamstring, knee and ankle) than in the comparison group, and 17% and 26% lower weekly injury prevalence than in the adductor and comparison groups. We also found significant injury rate reductions in extended Knee Control compared with the other groups for most secondary outcomes including incidence of time-loss injuries (42–48%) and prevalence of substantial injuries (26–27%). Considering the absence of a control group that did not use any IPEP, the injury risk reductions seen in extended Knee Control are encouraging. Our comparison group had used injury prevention exercises regularly in the previous year, about half the teams the Knee Control programme, and thus represent a ‘best-case real-world injury prevention example’. Our findings are in line with a previous systematic review showing a 39% risk reduction in football teams performing the 11+ programme versus control.21

Hypothesis 2 was, however, rejected; there were no between-group differences in groin injury incidence and, surprisingly, the highest prevalence of groin injuries was seen in the adductor group. This is in contrast with Harøy et al,15 who showed 41% lower risk of hip/groin injury with the Adductor Strengthening Programme, and from which we based our groin-focused intervention. The lack of preventive efficacy may be related to low compliance with the programme during the pre-season build-up period. We also had to implement alternative single player exercises due to COVID-19-related restrictions, and while the added adductor squeeze exercises have been included in successful rehabilitation programmes24 their preventive efficacy has not been established.18 25 Hence, it is difficult to compare results of this intervention to the study using only the Adductor Strengthening Programme.15 Additionally, whereas Harøy et al,15 included subelite male players, we included adolescent and adult amateur players of both sexes who may have been less devoted to training, and who had different training status and training tolerance. Challenges with low compliance and maintenance have been reported previously26 and we find it reasonable to assume that the lack of efficacy may be related to low fidelity with the programme protocol regarding number of repetitions, training frequency, exercise choice and progression. Additionally, players without groin problems may be more motivated to perform a broader generic programme aimed at overall injury risk reduction, rather than focusing on a specific injury. Hence, in line with adding adductor exercises to the 11+ programme,27 it could be valuable to integrate the adductor exercises within extended Knee Control, to facilitate regular training routines and player motivation. In fact, we incorporated 10 groin-focused exercises, including the five exercises used in the present study, into a further developed Knee Control programme; the Knee Control+.

Strengths and limitations

One major strength of this trial was the active comparison group representing real-world implementation of IPEPs. Other strengths were the use of structured validated self-report weekly questionnaires to players and coaches in combination with physiotherapist-collected data enabling detection of injuries and complaints irrespective of time-loss or medical attention and with cross-validation from different sources.

Some limitations should be mentioned. First, even though we met the a priori decided sample size, the low participation rate and the high pandemic-related dropout of teams and players must be considered. It is likely that the most motivated teams and players entered the study, which should be taken into account when considering compliance and external validity of findings. Participation rate among male players was particularly low and the dropout rendered unequal sex distribution between groups, and we therefore sex-adjusted all analyses. Ideally, programme effects should have been evaluated in men and women separately, but due to the small sample, sex-separated data are only presented descriptively. Second, the prolonged pre-season and shortened competitive season, and matches played without spectators due to the pandemic, limit the possibility of comparing injury rates with other samples. Importantly, the situation was the same within the three study arms and should have negligible impact on comparisons of injury rates. Third, we were forced to adapt the adductor programme due to the pandemic by adding two alternative adductor exercises. This complicates comparisons with studies using the original Adductor Strengthening Programme.20 Fourth, we relied on self-reported player data restricted to information about injury location and injury onset whereas specific diagnoses or injury types are unclear. Fifth, 20–25% of players engaged in other sports, most often indoor sports such as floorball and handball where the seasons do not overlap with the football season, but it is unknown how this may affect the players’ overall risk of injury. Sixth, the weekly response rate was rather low (65%) and minor injuries may have passed unnoticed, whereas more severe, long-lasting, injuries were detected. The response rate was similar between groups, and it is unlikely that this affected our injury rate comparisons, and was comparable with previous studies in adolescent athletes (58–66%).2 28 29 Seventh, due to the small sample and inaccurate data on playing experience and level, we were not able to analyse results based on player age, playing experience or level.

Conclusion

Amateur adolescent and adult male and female football players who performed extended Knee Control had nearly one-third lower incidence of injury to any of the three lower limb injury locations hamstring, knee and ankle compared with a comparison group conducting self-selected prevention exercises. Prevalence of injuries to the same three locations was one-fifth to one-fourth lower in extended Knee Control compared with an adductor strength programme and a comparison group. Lower incidence and prevalence of secondary outcomes, such as time-loss injuries and substantial injuries, were also seen in the extended Knee Control group compared with both other groups. In contrast, no preventive effect was seen from the adductor programme on groin injury.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participating coaches and players for taking part in the study. We thank Ida Åkerlund, Rebecca Samuelsson, Ida Elm and Hampus Viitanen for help with the data collection, and Mattias Karlén, Anton Svensson and Johan Lidén for help with the workshops and site visits to the teams. We thank the other members of the group, besides the authors, who participated in the development of extended Knee Control: Anne Fältström, Annica Näsmark, Mariann Gajhede Knudsen, Mia Ryding-Ederö and Tania Nilsson. We also thank Henrik Hedevik, statistician, for statistical support.

Footnotes

Twitter: @lindblom_hanna; @SWIPE__, @SofiSonesson; @SWIPE__, @torvaldssonk; @SWIPE__, @MarkusWalden; @SWIPE__, @MHgglund; @SWIPE__

Contributors: MH and HL planned the study and were responsible for data collection. MH, HL, MW and KT took part in the recruitment. HL and MH conducted the analyses together with the statistician. HL wrote the first draft of the paper, which was critically revised by MH, MW, KT and SS. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings and approved the final manuscript. MH is the study guarantor.

Funding: The study was funded by grants from the Swedish Research Council Reference number 2018-03135.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Board in Linköping (Reference number 2017/294-31) and the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Reference number 2019-06462). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1. Waldén M, Atroshi I, Magnusson H, et al. Prevention of acute knee injuries in adolescent female football players: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2012;344:e3042. 10.1136/bmj.e3042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Åkerlund I, Waldén M, Sonesson S, et al. Forty-five per cent lower acute injury incidence but no effect on overuse injury prevalence in youth floorball players (aged 12-17 years) who used an injury prevention exercise programme: two-armed parallel-group cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:1028–35. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Asker M, Hägglund M, Waldén M, et al. The effect of shoulder and knee exercise programmes on the risk of shoulder and knee injuries in adolescent elite handball players: a three-armed cluster randomised controlled trial. Sports Med Open 2022;8:91. 10.1186/s40798-022-00478-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Soligard T, Myklebust G, Steffen K, et al. Comprehensive warm-up programme to prevent injuries in young female footballers: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2008;337:a2469. 10.1136/bmj.a2469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Owoeye OBA, Akinbo SRA, Tella BA, et al. Efficacy of the FIFA 11+ warm-up programme in male youth football: a cluster randomised controlled trial. J Sports Sci Med 2014;13:321–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Silvers-Granelli H, Mandelbaum B, Adeniji O, et al. Efficacy of the FIFA 11+ injury prevention program in the collegiate male soccer player. Am J Sports Med 2015;43:2628–37. 10.1177/0363546515602009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Emery CA, Meeuwisse WH. The effectiveness of a neuromuscular prevention strategy to reduce injuries in youth soccer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:555–62. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.074377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Myklebust G, Engebretsen L, Braekken IH, et al. Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injuries in female team handball players: a prospective intervention study over three seasons. Clin J Sport Med 2003;13:71–8. 10.1097/00042752-200303000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pasanen K, Parkkari J, Pasanen M, et al. Neuromuscular training and the risk of leg injuries in female floorball players: cluster randomised controlled study. BMJ 2008;337:a295. 10.1136/bmj.a295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hislop MD, Stokes KA, Williams S, et al. Reducing musculoskeletal injury and concussion risk in schoolboy rugby players with a pre-activity movement control exercise programme: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:1140–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Åman M, Larsén K, Forssblad M, et al. A nationwide follow-up survey on the effectiveness of an implemented neuromuscular training program to reduce acute knee injuries in soccer players. Orthop J Sports Med 2018;6:232596711881384. 10.1177/2325967118813841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lindblom H, Waldén M, Carlfjord S, et al. Implementation of a neuromuscular training programme in female adolescent football: 3-year follow-up study after a randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1425–30. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lindblom H, Carlfjord S, Hägglund M. Adoption and use of an injury prevention exercise program in female football: a qualitative study among coaches. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2018;28:1295–303. 10.1111/sms.13012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O'Brien J, Young W, Finch CF. The delivery of injury prevention exercise programmes in professional youth soccer: comparison to the FIFA 11. J Sci Med Sport 2017;20:26–31. 10.1016/j.jsams.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harøy J, Clarsen B, Wiger EG, et al. The adductor strengthening programme prevents groin problems among male football players: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Br J Sports Med 2019;53:150–7. 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Campbell MK, Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, et al. Consort 2010 statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ 2012;345:e5661. 10.1136/bmj.e5661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Orkin AM, Gill PJ, Ghersi D, et al. Guidelines for reporting trial protocols and completed trials modified due to the COVID-19 pandemic and other Extenuating circumstances: the conserve 2021 statement. JAMA 2021;326:257–65. 10.1001/jama.2021.9941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hölmich P, Larsen K, Krogsgaard K, et al. Exercise program for prevention of groin pain in football players: a cluster-randomized trial. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010;20:814–21. 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.00998.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Clarsen B, Bahr R, Myklebust G, et al. Improved reporting of overuse injuries and health problems in sport: an update of the Oslo sport trauma research center questionnaires. Br J Sports Med 2020;54:390–6. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bahr R, Clarsen B, Derman W, et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement: methods for recording and reporting of epidemiological data on injury and illness in sport 2020 (including STROBE extension for sport injury and illness surveillance (STROBE-SIIS)). Br J Sports Med 2020;54:372–89. 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thorborg K, Krommes KK, Esteve E, et al. Effect of specific exercise-based football injury prevention programmes on the overall injury rate in football: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the FIFA 11 and 11+ programmes. Br J Sports Med 2017;51:562–71. 10.1136/bjsports-2016-097066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sahai H, Khurshid A. Statistics in epidemiology: methods, techniques, and applications. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lindblom H, Waldén M, Carlfjord S, et al. Limited positive effects on jump-landing technique in girls but not in boys after 8 weeks of injury prevention exercise training in youth football. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2020;28:528–37. 10.1007/s00167-019-05721-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hölmich P, Uhrskou P, Ulnits L, et al. Effectiveness of active physical training as treatment for long-standing adductor-related groin pain in athletes: randomised trial. Lancet 1999;353:439–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03340-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Engebretsen AH, Myklebust G, Holme I, et al. Prevention of injuries among male soccer players: a prospective, randomized intervention study targeting players with previous injuries or reduced function. Am J Sports Med 2008;36:1052–60. 10.1177/0363546508314432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Harøy J, Wiger EG, Bahr R, et al. Implementation of the Adductor Strengthening Programme: Players primed for adoption but reluctant to maintain - A cross-sectional study. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2019;29:1092–100. 10.1111/sms.13444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harøy J, Thorborg K, Serner A, et al. Including the Copenhagen adduction exercise in the FIFA 11+ provides missing eccentric hip adduction strength effect in male soccer players: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2017;45:3052–9. 10.1177/0363546517720194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moseid CH, Myklebust G, Fagerland MW, et al. The prevalence and severity of health problems in youth elite sports: a 6-month prospective cohort study of 320 athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2018;28:1412–23. 10.1111/sms.13047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. von Rosen P, Heijne A, Frohm A, et al. High injury burden in elite adolescent athletes: a 52-week prospective study. J Athl Train 2018;53:262–70. 10.4085/1062-6050-251-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bjsports-2022-105890supp001.pdf (13.2MB, pdf)

bjsports-2022-105890supp002.pdf (87.3KB, pdf)

bjsports-2022-105890supp003.pdf (63.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.