Abstract

Intracellular pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis are able to survive in the face of antimicrobial products generated by the host cell in response to infection. The product of the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase gene (ahpC) of M. tuberculosis is thought to be involved in protecting the organism against both oxidative and nitrosative stress encountered within the infected macrophage. Here we report that, contrary to expectations, ahpC expression in virulent strains of M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis grown in vitro is repressed, often below the level of detection, whereas expression in the avirulent vaccine strain M. bovis BCG is constitutively high. The repression of the ahpC gene of the virulent strains is independent of the naturally occurring lesions of central regulator oxyR. Using a green fluorescence protein vector (gfp)-ahpC reporter construct we present data showing that repression of ahpC of virulent M. tuberculosis also occurred during growth inside macrophages, whereas derepression in BCG was again seen under identical conditions. Inactivation of ahpC on the chromosome of M. tuberculosis by homologous recombination had no effect on its growth during acute infection in mice and did not affect in vitro sensitivity to H2O2. However, consistent with AhpC function in detoxifying organic peroxides, sensitivity to cumene hydroperoxide exposure was increased in the ahpC::Kmr mutant strain. The preservation of a functional ahpC gene in M. tuberculosis in spite of its repression under normal growth conditions suggests that, while AhpC does not play a significant role in establishing infection, it is likely to be important under certain, as yet undefined conditions. This is supported by the observation that repression of ahpC expression in vitro was lifted under conditions of static growth.

The success of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as a human pathogen is based on its ability to survive and grow within macrophages. Following infection, the bacteria are phagocytosed at the site of entry, usually in the lungs. M. tuberculosis survives this initial interaction with macrophages and may either grow to cause primary tuberculosis or enter a state of latency in which it can persist, sometimes for decades, within lung macrophages or other sites. Thus, while it is estimated that over 1 billion people are infected with M. tuberculosis worldwide (World Health Organization tuberculosis fact sheet [http://www.int]), only approximately 5 to 15% of the exposed individuals who undergo tuberculin conversion develop primary tuberculosis. The majority remain latently infected and run a 10% lifetime risk of developing active disease (33, 40). Latently infected individuals contribute to the persistence of M. tuberculosis in the population and affect the global tuberculosis control efforts. The sequencing and analysis of the complete M. tuberculosis genome (9) have made possible considerable progress in addressing the molecular basis of mycobacterial virulence. However, our understanding of how the organism survives in the face of hostile innate and acquired immune responses to produce primary disease and of the molecular basis for the establishment and maintenance of latency and for subsequent disease reactivation is far from complete.

M. tuberculosis infects macrophages and persists in granulomatous lesions in the host, where the bacilli are exposed to reactive oxygen intermediates (ROI) (11, 20, 44) and reactive nitrogen intermediates (6, 18, 26, 28, 30, 35) (RNI). The initial studies of the oxidative and nitrosative stress response in mycobacteria have yielded the paradoxical finding that the oxidative stress response is partially dysfunctional in the two most important mycobacterial pathogens, M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae (13–15, 27, 48). The M. tuberculosis equivalent of oxyR (13, 15, 39), the central regulator of the peroxide stress response (2, 8), which also acts as a regulator of the nitrosative stress response (21), has been shown to be a pseudogene, inactivated via multiple lesions (Fig. 1A). Similarly, the furA and katG genes of M. leprae are vestigial and carry multiple mutations (9, 14, 27, 32).

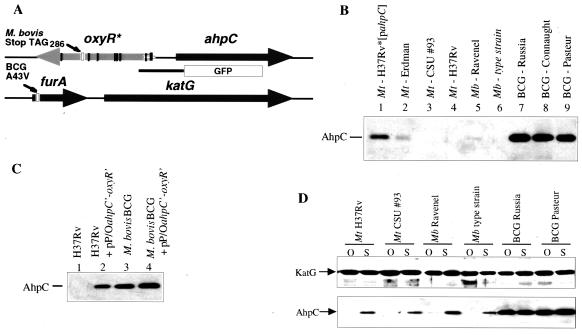

FIG. 1.

(A) Genetic organization of the oxyR-ahpC and furA-katG regions in the M. tuberculosis complex. The M. tuberculosis oxyR pseudogene (inactivated by multiple mutations; vertical bars) and ahpC are tightly linked and divergently transcribed. The furA and katG genes are linked in all mycobacteria. The M. bovis BCG furA carries a missense mutation (producing A43V). GFP box preceded by thick line, ahpC-gfp promoter fusion used in this work. (B) Low or undetectable ahpC expression in virulent M. tuberculosis and M. bovis and high level of AhpC production in M. bovis BCG. Shown is a Western blot with AhpC antibodies using extracts from various strains of M. tuberculosis (Mt), M. bovis (Mb), and M. bovis BCG (BCG) grown under standard aerated conditions in roller bottles. Equal amounts of protein were loaded in each lane. The same extracts tested for KatG showed no differences in all lanes (as in panel D). (C) Multicopy titration of ahpC repression in M. tuberculosis H37Rv. Plasmid pP/OahpC′-oxyR′-gfp, carrying the promoter region of ahpC (A), was introduced into M. tuberculosis H37Rv and M. bovis BCG by electroporation, with selection on media supplemented with antibiotics. Strains were grown under standard, aerated conditions, and cell extracts were examined by Western blotting using an antibody against M. tuberculosis AhpC (32). (D) Induction of AhpC production in M. tuberculosis H37Rv under static growth conditions. AhpC levels (Western blot) in M. bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis H37Rv grown under oxygenated (O) and static (S) growth conditions as previously described (45) are shown. Extracts were prepared, and Western blot analysis was carried out with KatG or AhpC antibodies.

Despite the loss of oxyR in M. tuberculosis and inactivation of furA and katG in M. leprae, several oxidative stress response genes are preserved in the tubercle and leprosy bacilli. One such gene, ahpC (9, 13, 23, 39, 48), encodes a subunit of an enzyme that detoxifies organic peroxides (25, 39) and possibly hydrogen peroxide (29). AhpC has been implicated in nitric oxide metabolism using heterologous systems (7). In the majority of mycobacterial species ahpC is expressed at normal levels (17, 32, 34, 49). However, the levels of AhpC in M. tuberculosis are usually undetectable or very low (17, 46, 51), although, according to some reports, AhpC can be detected in the tubercle bacillus (7). In mycobacterial species with a functional oxyR gene, OxyR binds to the ahpC promoter (15, 32, 44). Insertional inactivation of oxyR in Mycobacterium marinum results in reduced ahpC expression and abrogates its ability to respond to induction by exposure to hydrogen peroxide (Pagan-Ramos and Deretic, unpublished data). These studies support the notion that the loss of oxyR contributes to the low expression of ahpC in the tubercle bacillus. Nevertheless, the preservation of ahpC in M. tuberculosis suggests that, despite silencing, it plays a role in the physiology of this organism.

Here we extend our investigations of the silencing of ahpC in M. tuberculosis. We report a second level of ahpC regulation in the tubercle bacillus and the loss of repression in avirulent vaccine strain BCG. We also present data on in vivo expression of ahpC in infected macrophages and on the effect of targeted deletion of ahpC on the ability of M. tuberculosis H37Rv to produce acute infection in mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and in vivo stability of M. tuberculosis H37Rv.

M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis strains were from the American Type Culture Collection unless stated otherwise. Plasmids were introduced into mycobacteria as previously described (24). The construction and properties of M. tuberculosis H37Rv*, which overexpresses plasmid-borne ahpC, have been previously described (17). Mycobacteria were grown under aerated conditions or in static culture as previously described (45).

Insertional inactivation of ahpC in M. tuberculosis via homologous recombination.

The ahpC gene was inactivated using a previously published strategy for gene replacements in mycobacteria (36, 37). A BamHI fragment (H37Rv genomic coordinates 2723977 to 2729394) containing M. tuberculosis ahpC (cloned on a pBluescript plasmid containing wild-type rpsL from M. tuberculosis; vector ptrpA-1-rpsL+) was subjected to ahpC inactivation with a Kmr cassette by its insertion into the EcoRI site of ahpC (location 2726263 to 2726460). The nonreplicative plasmid was introduced into Strr M. tuberculosis H37Rv by electroporation, and Kmr colonies were screened by Southern blot analysis for single-crossover recombinants. Positively identified strains with the plasmid integrated on the chromosome via homologous recombination events were subjected to counterselection against rpsL, carried by the vector moiety, by plating on media containing streptomycin. Strr colonies were subjected to Southern blot analysis, and recombinants that underwent second crossover events were identified as strains with ahpC::Kmr gene replacements.

GFP fusions, macrophage infection, flow cytometry, and antibodies for Western blot analyses.

The ahpC-gfp and hsp60-gfp fusions and the gfp vector have been previously reported and characterized (16). Macrophage infection with mycobacteria passed through a 5-μm-pore-size filter to ensure removal of clumps and flow-cytometric analysis were carried out as previously described (16, 43). Flow cytometry of formaldehyde-fixed green fluorescence protein (GFP)-labeled mycobacteria, released from macrophages as described previously (16), was carried out in a Becton Dickinson FACSCAN, and data were analyzed by Lysis II software. The rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against purified M. tuberculosis AhpC has been previously reported (32). The rabbit polyclonal antibody raised against a KatG peptide was from C. Barry.

Mouse model of tuberculosis infection.

The wild-type strain and single-crossover and ahpC-deleted mutant strains of M. tuberculosis H37Rv Strr were grown in Dubos 7H9 broth for 14 days. Each strain was diluted in phosphate-buffered saline to give a suspension of approximately 2.5 × 105 CFU per ml, and 0.2 ml of these suspensions was inoculated intravenously (31) into 6- to 8-week-old female BALB/c mice. The infection was monitored by removing the lungs and spleens of infected mice and homogenizing them by shaking with 2-mm-diameter glass beads in chilled saline with a Mini-Bead Beater (Biospec Products, Bartlesville, Okla.). Serial 10-fold dilutions of the resultant suspensions were plated onto Dubos 7H11 agar with Dubos oleic albumin complex supplement (Difco Laboratories, Surrey, United Kingdom). The numbers of CFU were determined after the plates had been incubated at 37°C for 20 days.

Sensitivity to compounds and survival in macrophages.

Statically grown cultures of H37Rv and H37Rv ahpC::Kmr were allowed to reach stationary phase (about 3 weeks) in 7H9 broth. One milliliter of each culture was added individually to 4 ml of 7H9 broth and allowed to settle for 1 week before cumene hydroperoxide (Sigma Chemicals) or hydrogen peroxide (Sigma Chemicals) was added at the concentrations indicated in the legend for Fig. 5. The optical density at 600 nm (OD600) was determined immediately following addition of agents and on the third and seventh days following treatment.

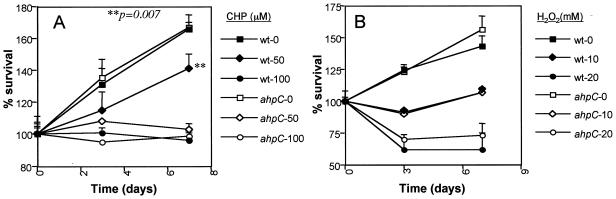

FIG. 5.

Survival curves of H37Rv and H37Rv ahpC::Kmr treated with cumene hydroperoxide (CHP) (A) or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) (B). Percent starting OD600 was determined from the OD600 (see Materials and Methods) normalized to the OD at the beginning of the experiment. Solid symbols, ahpC+ strain; open symbols, ahpC::Kmr mutant. wt, wild type.

Statistical analysis.

Analysis of variance and post hoc analyses were performed using SuperANOVA (version 1.11; Abacus Concepts).

RESULTS

Low levels of ahpC expression in virulent M. tuberculosis.

Our previous work using antibodies against heterologous AhpC suggested that levels of AhpC are very low or below detection limits in M. tuberculosis H37Rv (17). Here we used an antibody raised against M. tuberculosis AhpC (32) to compare the relative levels of ahpC expression in different M. tuberculosis strains. Very low levels of AhpC (or its apparent absence) were observed in M. tuberculosis strains H37Rv, Erdman, and CSU #93 (Fig. 1B). Similar silencing of ahpC expression was observed in virulent strain M. bovis Ravenel and the M. bovis type strain, ATCC 19210 (Fig. 1B). AhpC was detectable in the previously constructed (17) derivative of M. tuberculosis H37Rv (termed H37Rv*), which differs from H37Rv only in harboring a plasmid-borne ahpC gene (Fig. 1B, lane 1).

The very low level of ahpC expression in virulent M. tuberculosis complex strains could be attributed to the loss of oxyR in the tubercle bacillus (12, 14). However, our recent inactivation of oxyR in M. marinum (Pagan-Ramos and Deretic, unpublished data) has suggested that, while induction of ahpC is impaired in the oxyR mutant, the steady-state levels of ahpC remained relatively high and unchanged under normal growth conditions. Thus, the finding of very low levels of detectable AhpC in M. tuberculosis was difficult to explain by the loss of oxyR alone. To test the possibility that this phenomenon could be due to an additional process of active repression, we introduced into M. tuberculosis H37Rv the ahpC-oxyR intergenic region containing the ahpC promoter (17) on a plasmid and examined chromosomal ahpC expression by monitoring AhpC levels by Western blotting. We detected increased levels of AhpC in the strain harboring extra copies of the plasmid-borne ahpC promoter/operator region (Fig. 1C, lanes 1 and 2), indicating that the chromosomal copy of ahpC was derepressed, possibly due to a multicopy titration of a negative regulatory element(s), e.g., a transcriptional repressor. These observations suggest that ahpC may be actively silenced in M. tuberculosis via repression mechanisms in addition to the effects of the loss of activator oxyR. In search of conditions that may derepress ahpC in virulent strains, we found that growth of M. tuberculosis H37Rv under static conditions induced production of significantly higher levels of AhpC (Fig. 1D, lanes S) than growth under oxygenated conditions. The effect was specific for AhpC, as KatG levels did not change (Fig. 1D).

Loss of ahpC repression in avirulent vaccine strain BCG.

A similar set of experiments was carried out with M. bovis BCG (Pasteur). In contrast to various strains of M. tuberculosis, M. bovis BCG showed high levels of AhpC expression even in the absence of the repressor-titrating plasmid construct (Fig. 1C, lane 3), and expression of AhpC was only slightly increased in the strain harboring the oxyR-ahpC promoter/operator region. We next investigated different BCG strains and observed high levels of AhpC (Fig. 1B, lanes 7 to 9) compared to those for M. tuberculosis (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 to 4). Although levels of AhpC were relatively high in all BCG strains, they were low or undetectable in the parent organism, M. bovis (Fig. 1B, lanes 5 and 6). A recent study (3) suggested that BCG Russia (ATCC 35740) is probably the BCG strain that is the closest to the original strain of BCG derived from virulent M. bovis. BCG Russia also showed high levels of AhpC (Fig. 1B, lane 7), suggesting that the deregulation of ahpC expression in BCG is a property of all BCG strains. Thus, the mutation(s) causing overexpression of ahpC occurred early in the BCG lineage and most likely emerged during passages that led to avirulence of M. bovis BCG.

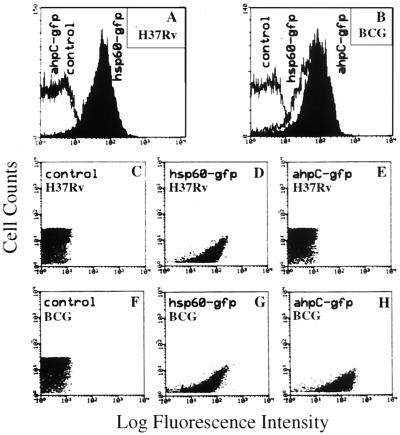

In vivo silencing of ahpC in M. tuberculosis H37Rv and expression in M. bovis BCG during macrophage infection. The experiments described in the previous sections suggest that ahpC repression in virulent strains may be an important aspect of M. tuberculosis biology and pathogenesis. However, the Western blot data were obtained using bacteria cultured in vitro. To test whether the silencing of ahpC observed in vitro also takes place in vivo, we examined ahpC expression in infected macrophages using GFP as a reporter of transcriptional activity (16). M. tuberculosis H37Rv and M. bovis BCG strains carrying the ahpC-gfp (Fig. 1A) or hsp60-gfp (16) transcriptional fusions were used to infect macrophages. The promoter activities were monitored by flow cytometry after 3 days of infection. The results (Fig. 2A and C to E) indicate that, whereas the hsp60 promoter was active (positive control), the ahpC promoter was inactive or was expressed below detection limits in M. tuberculosis H37Rv during macrophage infection. In contrast, the activity of the ahpC-gfp fusion in BCG exceeded that of strong promoter fusion hsp60-gfp (Fig. 2F to H). Hence, repression (silencing) of ahpC in virulent M. tuberculosis occurs in vivo during intraphagosomal growth, while ahpC is derepressed in BCG in infected macrophages.

FIG. 2.

Expression analyses of ahpC in M. tuberculosis H37Rv and M. bovis BCG in infected macrophages. Expression of ahpC-gfp was monitored by flow cytometry and compared with that in bacteria carrying no gfp (control) and the hsp60-gfp fusion. Macrophages (J774 cells) were infected with mycobacteria containing the gfp fusions indicated, and after 3 days samples were prepared and flow cytometry was carried out as described previously (16). (A and B) Fluorescence intensity distribution in macrophage-grown H37Rv and BCG. (C to E) Dot plots corresponding to panel A. (F to H) Dot plots corresponding to panel B.

Inactivation of ahpC in M. tuberculosis H37Rv by homologous recombination and analysis of infection in mice.

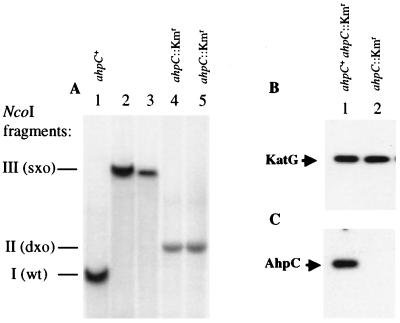

The silencing of ahpC during in vitro growth or in infected macrophages suggests that AhpC may not play a major role in M. tuberculosis in resistance against host-generated protective mechanisms during infection. To test this possibility, we inactivated the ahpC gene on the chromosome of M. tuberculosis H37Rv via homologous recombination using a selection procedure described in Materials and Methods. Southern blot hybridization analyses carried out with the parental ahpC+ strain of M. tuberculosis H37Rv, single-crossover intermediates, and the final ahpC::Kmr strain demonstrated that a true gene replacement had taken place (Fig. 3A). Western blot analyses also confirmed that, while KatG levels were unchanged (Fig. 3B), there was no detectable AhpC product in the ahpC knockout strain (Fig. 3C; the protein extracts were prepared from cells grown under conditions permitting induction of ahpC in M. tuberculosis H37Rv as in Fig. 1D).

FIG. 3.

Inactivation of ahpC in M. tuberculosis H37Rv. (A) Southern blot using ahpC as a probe. Two independent isolates in each case (lanes 2 and 3 and lanes 4 and 5) are shown. (B and C) Western blots with KatG and AhpC antibodies, respectively. Mycobacteria were grown under static conditions for Western blot analysis. Equal amounts of protein were loaded per lane. wt, wild type; sxo, single-crossover strain; dxo, double-crossover strain.

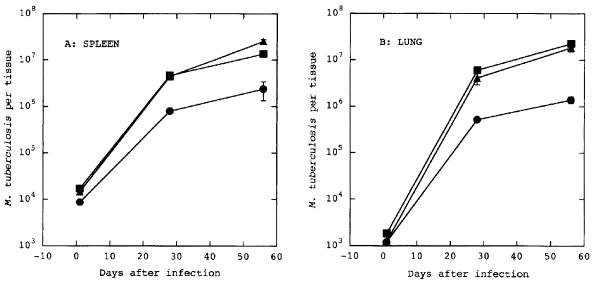

The mutant ahpC::Kmr strain was then compared with the parental strain and with the ahpC+ ahpC::Kmr merodiploid single-crossover intermediate strain, which carries both a mutant and wild-type ahpC, for virulence in a mouse model of tuberculosis. BALB/c mice were infected intravenously with 5 × 104 CFU of the three strains of M. tuberculosis, and growth was determined by plating serial dilutions of homogenized lungs and spleens at 28 and 56 days postinfection. No significant difference in growth rate between the mutant ahpC::Kmr strain and the ahpC+ strains was observed (Fig. 4). The apparent minor inferiority of the ahpC+ parental strain was, however, not seen with the ahpC+ ahpC::Kmr merodiploid intermediate, which showed a growth pattern identical to that of the ahpC mutant. Thus, we conclude that ahpC inactivation does not reduce the virulence of the tubercle bacillus in the murine model of tuberculosis.

FIG. 4.

Effects of ahpC inactivation on M. tuberculosis virulence in mice. BALB/c mice were infected intravenously with 5 × 104 M. tuberculosis H37Rv CFU. The numbers of CFU per tissue were determined for spleens (A) and lungs (B). Shown are results from one of the two separate experiments with similar outcomes (n = 6 per time point). Each point represents the mean ± standard errors. Circles, H37Rv Strr ahpC+; triangles, H37Rv Strr ahpC::Kmr mutant; squares, H37Rv Strr ahpC ahpC::Kmr merodiploid single-crossover strain (ahpC+ ahpC::Kmr).

AhpC role in protection against peroxide toxicity.

Despite the apparent silencing of ahpC in virulent M. tuberculosis, the preservation of an intact ahpC gene indicates that it confers a selective advantage under some circumstances encountered by the organism. The results presented previously (Fig. 1D) indicate that growth of M. tuberculosis under static conditions is associated with increased expression of ahpC. We therefore investigated the functional relevance of AhpC production during static incubation by exposing the ahpC+ parental strain of M. tuberculosis and the isogenic ahpC::Kmr mutant strain to different concentrations of organic peroxide cumene hydroperoxide and hydrogen peroxide under different aeration conditions. In aerated cultures, consistent with low levels of ahpC expression, no differences in sensitivity to peroxides were detected (data not shown). Under static conditions of growth, we observed increased sensitivity, specifically to organic peroxide cumene hydroperoxide, in the ahpC::Kmr mutant compared to the ahpC + parent (Fig. 5A). No detectable differences between the wild-type and ahpC::Kmr strains in sensitivity to hydrogen peroxide were observed (Fig. 5B).

DISCUSSION

The mechanisms by which M. tuberculosis is able to survive and grow within the hostile environment of a host macrophage are likely to be complex and multifactorial. In addition to the ability of the bacteria to influence their microenvironment within the phagosome (1, 19, 41), the ability of M. tuberculosis to produce agents which counter the toxicity of antimicrobial products produced by activated macrophages is thought to be important. There is considerable evidence that the production of RNI and/or ROI by macrophages is important in the generation of effective immunity against mycobacteria (6, 11, 18, 20, 26, 28, 30, 35, 44). Thus, detoxification of RNI and ROI by the bacteria is expected to influence their intracellular survival. Several genes in the M. tuberculosis genome which encode proteins thought to be involved in protection against RNI and/or ROI have been identified (9). In this study we have focused on one such gene, ahpC. This gene was chosen because of its reported role in the virulence of another member of the M. tuberculosis complex, M. bovis (46), and because of the role of AhpC in detoxifying organic peroxides (25, 39), hydrogen peroxide (29), and RNI (4, 7).

Our results with the ahpC::Kmr strain of M. tuberculosis, which carries an insertionally inactivated ahpC gene, indicate that AhpC plays no significant role during the acute-infection phase of mice. This is compatible with similar experiments with Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, in which inactivation of ahpC had no effect on virulence in BALB/c mice (42). Similarly, up-regulation of ahpC in a strain of M. tuberculosis which had lost KatG activity did not result in increased virulence in mice (22), again suggesting that AhpC is not involved in virulence, at least during the acute phase of infection. These results are in contrast to those of Wilson et al. (46), who used an antisense RNA strategy to down-regulate ahpC expression in M. bovis and found significantly decreased virulence in guinea pigs. These discrepancies may be explained by different methodologies used to generate a null mutant or phenotype, differences in virulence determinants between M. tuberculosis and M. bovis in spite of their close sequence similarity, or different animal models used to evaluate virulence.

Our results demonstrating a very low level of ahpC expression in M. tuberculosis and M. bovis, contrasting with the high level of ahpC expression in BCG, both in vitro and during growth in macrophages, also appear to argue against an overt role in virulence. Nevertheless, the retention of a functional ahpC gene by M tuberculosis in spite of the loss of oxyR, the gene encoding the major regulator of ahpC, suggests that a functional ahpC must confer some selective advantage. It is also noteworthy that M. leprae, a closely related pathogen which has undergone considerable genome downsizing, has retained functional ahpC and oxyR genes (10). The facts that we found elevated levels of expression of ahpC in static cultures compared to those in aerated cultures and that in static cultures the ahpC::Kmr strain of M. tuberculosis was more sensitive to organic peroxides lend support to the idea that there are environmental conditions for which AhpC production is advantageous. Whether such conditions are important during the infection cycle of M. tuberculosis remains to be determined.

While the lack of a functional oxyR gene in M. tuberculosis could explain the very low levels of ahpC expression, the regulation of ahpC in mycobacteria does not appear to simply involve the binding of OxyR to the ahpC promoter. Introduction of the plasmid-borne ahpC-oxyR intergenic region results in increased production of AhpC in M. tuberculosis, consistent with the presence of a transcriptional repressor. In addition, M. bovis BCG also lacks oxyR, as is the case with all other members of the M. tuberculosis complex (12, 14). Thus, differences in ahpC expression between BCG and virulent M. bovis cannot be attributed to the loss of oxyR. Overexpression of ahpC has been associated in some strains of M. tuberculosis and M. bovis with mutations in the ahpC promoter (17, 38, 51). We determined the nucleotide sequence of the oxyR-ahpC region in BCG strains, and no sequence alterations in the ahpC promoter were observed to account for the enhanced AhpC levels in BCG (data not shown). Recently, it has been reported that ahpC expression is regulated by PerR in gram-positive bacterium Bacillus subtilis (5). Sequence alignments (14, 32) have indicated that PerR is a close homologue of mycobacterial FurA, encoded by a gene upstream of katG (Fig. 1). DNA sequence analyses revealed that all M. bovis BCG strains tested carry a point mutation (C128→T128) within the furA coding sequence (GenBank accession no. AF130346 for BCG) relative to the wild-type sequences in virulent M. bovis strains (GenBank accession no. AF130347 for the M. bovis type strain, ATCC 19210) and in all other members of the M. tuberculosis complex. The C128→T128 change results in the A43V substitution in BCG FurA (Fig. 1A). The corresponding alanine residue is highly conserved in all FurA homologues, as shown in multiple sequence alignments of mycobacterial FurA (32), including the newly reported Mycobacterium smegmatis FurA (50). FurA missense mutations in the corresponding regions of PerR have been found to affect its repressor function and result in derepression of ahpC in B. subtilis (5). Thus, derepression of ahpC in M. bovis BCG could be the result of the A43V mutation in the furA gene.

The results reported here demonstrate that M. tuberculosis regulates expression of AhpC. In spite of the previous failure to produce a targeted deletion of the ahpC gene in members of the M. tuberculosis complex (47), ahpC is not an essential gene for M. tuberculosis, and the protein does not appear to play a significant role in establishing infection in mice. Nevertheless, the conservation of a functional ahpC gene, the ability to regulate its expression, the increased production of the gene product during specific conditions of in vitro growth, and its ability to protect the organism against the toxic activity of organic peroxides all point to a significant role in the physiology of M. tuberculosis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank C. Barry for the KatG antibody and T. Shinnick for help with transfers of biohazard materials.

B. Springer and S. Master contributed equally to this work.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant AI42999 to V.D., and Commission of the European Communities (QLK2-CT-1999-0193) and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (BO 820/11-2, BO 820/13-1) grants to E.B. J.S. and T.Z. were supported by NRSA postdoctoral fellowships from National Institutes of Health. M.M. was supported by an NIH training grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong J A, Hart P D. Phagosome-lysosome interactions in cultured macrophages infected with virulent tubercle bacilli. Reversal of the usual nonfusion pattern and observations on bacterial survival. J Exp Med. 1975;142:1–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.142.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aslund F, Zheng M, Beckwith J, Storz G. Regulation of the OxyR transcription factor by hydrogen peroxide and the cellular thiol-disulfide status. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6161–6165. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.11.6161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behr M A, Wilson M A, Gill W P, Salamon H, Schoolnik G K, Rane S, Small P M. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science. 1999;284:1520–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryk R, Griffin P, Nathan C. Peroxynitrite reductase activity of bacterial peroxiredoxins. Nature. 2000;407:211–215. doi: 10.1038/35025109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bsat N, Helmann J D. Interaction of Bacillus subtilis Fur (ferric uptake repressor) with the dhb operator in vitro and in vivo. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:4299–4307. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.14.4299-4307.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan J, Xing Y, Magliozzo R S, Bloom B R. Killing of virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis by reactive nitrogen intermediates produced by activated murine macrophages. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1111–1122. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.4.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L, Xie Q W, Nathan C. Alkyl hydroperoxide reductase subunit C (AhpC) protects bacterial and human cells against reactive nitrogen intermediates. Mol Cell. 1998;1:795–805. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80079-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christman M F, Morgan R W, Jacobson F S, Ames B N. Positive control of a regulon for defenses against oxidative stress and some heat-shock proteins in Salmonella typhimurium. Cell. 1985;41:753–762. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon S V, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry III C E, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Barrell B G, et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cole S T, Eiglmeier K, Parkhill J, James K D, Thomson N R, Wheeler P R, Honore N, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Mungall K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R M, Devlin K, Duthoy S, Feltwell T, Fraser A, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Lacroix C, Maclean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Quail M A, Rajandream M A, Rutherford K M, Rutter S, Seeger K, Simon S, Simmonds M, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Stevens K, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Woodward J R, Barrell B G. Massive gene decay in the leprosy bacillus. Nature. 2001;409:1007–1011. doi: 10.1038/35059006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper A M, Segal B H, Frank A A, Holland S M, Orme I M. Transient loss of resistance to pulmonary tuberculosis in p47phox−/− mice. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1231–1234. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1231-1234.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deretic V, Pagan-Ramos E, Zhang Y, Dhandayuthapani S, Via L E. The extreme sensitivity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to the front-line antituberculosis drug isoniazid. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:1557–1561. doi: 10.1038/nbt1196-1557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deretic V, Philipp W, Dhandayuthapani S, Mudd M H, Curcic R, Garbe T, Heym B, Via L E, Cole S T. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a natural mutant with an inactivated oxidative-stress regulatory gene: implications for sensitivity to isoniazid. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:889–900. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17050889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deretic V, Song J, Pagan-Ramos E. Loss of oxyR in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:367–372. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dhandayuthapani S, Mudd M, Deretic V. Interactions of OxyR with the promoter region of the oxyR and ahpC genes from Mycobacterium leprae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:2401–2409. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.7.2401-2409.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhandayuthapani S, Via L E, Thomas C A, Horowitz P M, Deretic D, Deretic V. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression and cell biology of mycobacterial interactions with macrophages. Mol Microbiol. 1995;17:901–912. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_17050901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dhandayuthapani S, Zhang Y, Mudd M H, Deretic V. Oxidative stress response and its role in sensitivity to isoniazid in mycobacteria: characterization and inducibility of ahpC by peroxides in Mycobacterium smegmatis and lack of expression in M. aurum and M. tuberculosis. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3641–3649. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3641-3649.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ehrt S, Shiloh M U, Ruan J, Choi M, Gunzburg S, Nathan C, Xie Q, Riley L W. A novel antioxidant gene from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 1997;186:1885–1896. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.11.1885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrari G, Langen H, Naito M, Pieters J. A coat protein on phagosomes involved in the intracellular survival of mycobacteria. Cell. 1999;97:435–447. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80754-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gordon A H, Hart P D. Stimulation or inhibition of the respiratory burst in cultured macrophages in a mycobacterium model: initial stimulation is followed by inhibition after phagocytosis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4650–4651. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4650-4651.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hausladen A, Privalle C T, Keng T, DeAngelo J, Stamler J S. Nitrosative stress: activation of the transcription factor OxyR. Cell. 1996;86:719–729. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heym B, Stavropoulos E, Honore N, Domenech P, Saint-Joanis B, Wilson T M, Collins D M, Colston M J, Cole S T. Effects of overexpression of the alkyl hydroperoxide reductase AhpC on the virulence and isoniazid resistance of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1395–1401. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1395-1401.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hillas P J, del Alba F S, Oyarzabal J, Wilks A, Ortiz De Montellano P R. The AhpC and AhpD antioxidant defense system of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:18801–18809. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001001200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jacobs W R, Jr, Kalpana G V, Cirillo J D, Pascopella L, Snapper S B, Udani R A, Jones W, Barletta R G, Bloom B R. Genetic systems for mycobacteria. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:537–555. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04027-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jacobson F S, Morgan R W, Christman M F, Ames B N. An alkyl hydroperoxide reductase from Salmonella typhimurium involved in the defense of DNA against oxidative damage. Purification and properties. J Biol Chem. 1989;264(3):1488–1496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacMicking J D, North R J, LaCourse R, Mudgett J S, Shah S K, Nathan C F. Identification of nitric oxide synthase as a protective locus against tuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5243–5248. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakata N, Matsuoka M, Kashiwabara Y, Okada N, Sasakawa C. Nucleotide sequence of the Mycobacterium leprae katG region. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3053–3057. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.9.3053-3057.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nicholson S, Bonecini-Almeida M, Lapa e Silva J R, Nathan C, Xie Q W, Mumford R, Weidner J R, Calaycay J, Geng J, Boechat N, et al. Inducible nitric oxide synthase in pulmonary alveolar macrophages from patients with tuberculosis. J Exp Med. 1996;183:2293–2302. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niimura Y, Poole L B, Massey V. Amphibacillus xylanus NADH oxidase and Salmonella typhimurium alkyl-hydroperoxide reductase flavoprotein components show extremely high scavenging activity for both alkyl hydroperoxide and hydrogen peroxide in the presence of S. typhimurium alkyl-hydroperoxide reductase 22-kDa protein component. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25645–25650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nozaki Y, Hasegawa Y, Ichiyama S, Nakashima I, Shimokata K. Mechanism of nitric oxide-dependent killing of Mycobacterium bovis BCG in human alveolar macrophages. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3644–3647. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3644-3647.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Orme I M, Collins F M. Mouse model of tuberculosis. In: Bloom B R, editor. Tuberculosis: pathogenesis, protection, and control. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1994. pp. 113–134. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pagan-Ramos E, Song J, McFalone M, Mudd M H, Deretic V. Oxidative stress response and characterization of the oxyR-ahpC and furA-katG loci in Mycobacterium marinum. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4856–4864. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4856-4864.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parrish N M, Dick J D, Bishai W R. Mechanisms of latency in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:107–112. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01216-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pessolani M C, Brennan P J. Molecular definition and identification of new proteins of Mycobacterium leprae. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5425–5427. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5425-5427.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruan J, St John G, Ehrt S, Riley L, Nathan C. noxR3, a novel gene from Mycobacterium tuberculosis, protects Salmonella typhimurium from nitrosative and oxidative stress. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3276–3283. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3276-3283.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sander P, Bottger E C. Gene replacement in Mycobacterium smegmatis using a dominant negative selectable marker. Methods Mol Biol. 1998;101:207–216. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-471-2:207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sander P, Meier A, Bottger E C. rpsL+: a dominant selectable marker for gene replacement in mycobacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:991–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sherman D R, Mdluli K, Hickey M J, Arain T M, Morris S L, Barry C E, Stover C K. Compensatory ahpC gene expression in isoniazid-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Science. 1996;272:1641–1643. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sherman D R, Sabo P J, Hickey M J, Arain T M, Mahairas G G, Yuan Y, Barry III C E, Stover C K. Disparate responses to oxidative stress in saprophytic and pathogenic mycobacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:6625–6629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.14.6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Snider D E, Jr, La Montagne J R. The neglected global tuberculosis problem: a report of the 1992 World Congress on Tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:1189–1196. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.6.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schlesinger P H, Chakraborty P, Haddix P L, Collins H L, Fok A K, Allen R D, Gluck S L, Heuser J, Russell D G. Lack of acidification in Mycobacterium phagosomes produced by exclusion of the vesicular proton-ATPase. Science. 1994;263:678–681. doi: 10.1126/science.8303277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Taylor P D, Inchley C J, Gallagher M P. The Salmonella typhimurium AhpC polypeptide is not essential for virulence in BALB/c mice but is recognized as an antigen during infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3208–3217. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.7.3208-3217.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Via L E, Fratti R A, McFalone M, Pagan-Ramos E, Deretic D, Deretic V. Effects of cytokines on mycobacterial phagosome maturation. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:897–905. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.7.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Walker L, Lowrie D B. Killing of Mycobacterium microti by immunologically activated macrophages. Nature. 1981;293:69–71. doi: 10.1038/293069a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wayne L G. Dynamics of submerged growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis under aerobic and microaerophilic conditions. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1976;114:807–811. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1976.114.4.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilson T, de Lisle G W, Marcinkeviciene J A, Blanchard J S, Collins D M. Antisense RNA to ahpC, an oxidative stress defence gene involved in isoniazid resistance, indicates that AhpC of Mycobacterium bovis has virulence properties. Microbiology. 1998;144:2687–2695. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-10-2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilson T, Wards B J, White S J, Skou B, de Lisle G W, Collins D M. Production of avirulent Mycobacterium bovis strains by illegitimate recombination with deoxyribonucleic acid fragments containing an interrupted ahpC gene. Tuber Lung Dis. 1997;78:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8479(97)90003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilson T M, Collins D M. ahpC, a gene involved in isoniazid resistance of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:1025–1034. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.449980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yamaguchi R, Matsuo K, Yamazaki A, Takahashi M, Fukasawa Y, Wada M, Abe C. Cloning and expression of the gene for the Avi-3 antigen of Mycobacterium avium and mapping of its epitopes. Infect Immun. 1992;60:1210–1216. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.3.1210-1216.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zahrt T C, Song J, Siple J, Deretic V. Mycobacterial FurA is a negative regulator of catalase-peroxidase gene katG. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:1174–1185. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2001.02321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang Y, Dhandayuthapani S, Deretic V. Molecular basis for the exquisite sensitivity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to isoniazid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:13212–13216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.23.13212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]