Abstract

As guidelines, therapies, and literature on cancer variants expand, the lack of consensus variant interpretations impedes clinical applications. CIViC is a public domain, crowd-sourced, and adaptable knowledgebase of evidence for the Clinical Interpretation of Variants in Cancer, designed to reduce barriers to knowledge sharing and alleviate the variant interpretation bottleneck.

Introduction

The demands of genetics-based clinical decision making in cancer are steadily increasing. For example, in 2018, NTRK gene fusions became the first cancer variants to receive FDA approval for targeted therapy irrespective of the type of solid tumor in which they were observed. PubMed articles mentioning ‘NTRK fusions’ have increased 10 fold since this approval, reflecting its dramatic impact on the cancer therapy and research landscape. The FDA’s “Novel Drug Approvals for 2021” list included 16 approvals related to the treatment of cancer, averaging one new approval approximately every 23 days. The lack of clear and comprehensive cancer variant interpretations creates a major bottleneck in this process leading to unnecessary delays in diagnosis and impeding the development of tailored clinical approaches. The timely review of clinically-relevant biomedical literature remains untenable for individual institutions with entirely internal (siloed) databases. Yet unlike the fixture of centralized publicly available repositories such as gnomAD (gnomad.broadinstitute.org) and ClinGen (clinicalgenome.org), that have become mainstays of germline variant interpretation, the field of somatic cancer variant interpretation has lagged behind in establishing guidelines, expert panels, and centralized resources to support clinical applications.

CIViC (Clinical Interpretation of Variants in Cancer; civicdb.org)1,2 is an open-access, open-source knowledgebase and curation system for cancer variant interpretation, which leverages an international team of experts designated as Curators and Editors, collaborating remotely within a centralized curation interface. Crowdsourced and expert-moderated variant interpretations are made freely available (public domain CC0 dedication) through web and application programming interfaces (APIs). CIViC is underlined by six founding principles to maintain a freely and computationally accessible resource with transparency, an open license, and interdisciplinary participation to support community consensus. The strong commitment to open-access and data provenance is a distinguishing feature of CIViC among somatic cancer variant interpretation resources. This open approach is necessary to engage participation from diverse stakeholders including researchers, clinicians, and patient advocates, allowing the CIViC knowledgebase to evolve with changing needs and standards, and successfully address the variant interpretation bottleneck.

Establishing and integrating the CIViC model

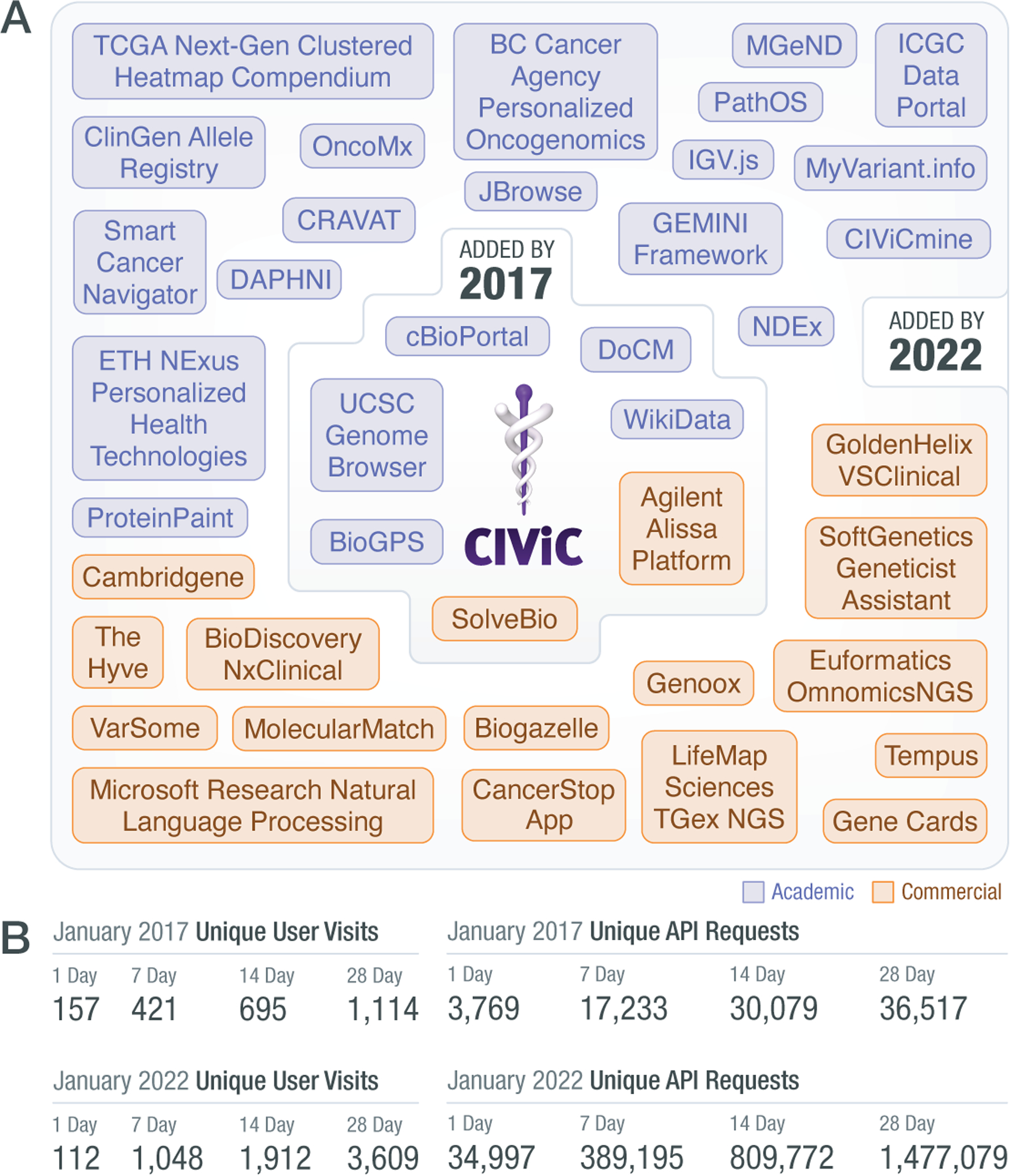

Anyone can access the CIViC knowledgebase without login. Users average >3,500 per month, span the globe, and API access to CIViC exceeds >1,000,000 requests per month, disseminating content to many more users and downstream applications. The steady growth in users and self-identified data clients illustrate the diversity of stakeholders, including clinicians, researchers, and educators, that consume the data (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Evolution of CIViC User Engagement.

A) The list of CIViC self-identified data clients has grown from the time of initial publication in 2017 to present (civicdb.org/data-clients), with many more commercial and academic organizations using the web and application programming interfaces (API) anonymously. B) Growth in user visits with the CIViC web interface (left) and the API (right), by comparing traffic snapshots from January of 2017 (top) and 2022 (bottom).

Over 300 Curators have to date been recruited to contribute curated Evidence Items, the foundational unit of the CIViC resource. Each Evidence Item is curated from the published literature and consists of a free-form summary of the clinical or preclinical evidence along with structured fields that provide important context such as variant name and origin, evidence type and quality, clinical significance, and cancer subtype1,2. For example, a single Evidence Item might describe clinical findings from a phase I trial that congenital fibrosarcoma tumors harboring ETV6::NTRK3 fusions are sensitive to larotrectinib. Though Evidence Item curation is one of the most time-intensive tasks in CIViC the knowledgebase has seen steady growth due to continued volunteer engagement of our Curators. Evidence Items from external Curators have even overtaken the contributions of Curators from Washington University School of Medicine, where CIViC originated (Figure 2). The responsibility of moderating contributed content to fit our curation standard operating procedure2, which includes evaluation of preclinical and clinical trial standards, falls to expert CIViC Editors. To meet the challenges of engaging external Editors, CIViC provides extensive support with live training, training videos, tutorials, and help documentation (available at docs.civicdb.org). For example, two of the 15 Curators from the Personalized OncoGenomics program3 (NCT02155621) at BC Cancer (British Columbia, Canada) have also been trained as Editors, allowing them to curate and moderate CIViC Evidence associated with real-world precision oncology cases, while also providing feedback to improve CIViC integration within their program’s variant interpretation workflow. To further address the accumulation of content in need of moderation, we have recruited new Editors from members of the Somatic Cancer Clinical Domain Working Group (SC-CDWG; https://clinicalgenome.org/curation-activities/somatic/)4 of the Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen), a related centralized resource for interpretation of genetic variants across human disease. In turn, CIViC has been adopted as the variant curation platform for current and future ClinGen Somatic Cancer Variant Curation Expert Panels (SC-VCEPs).

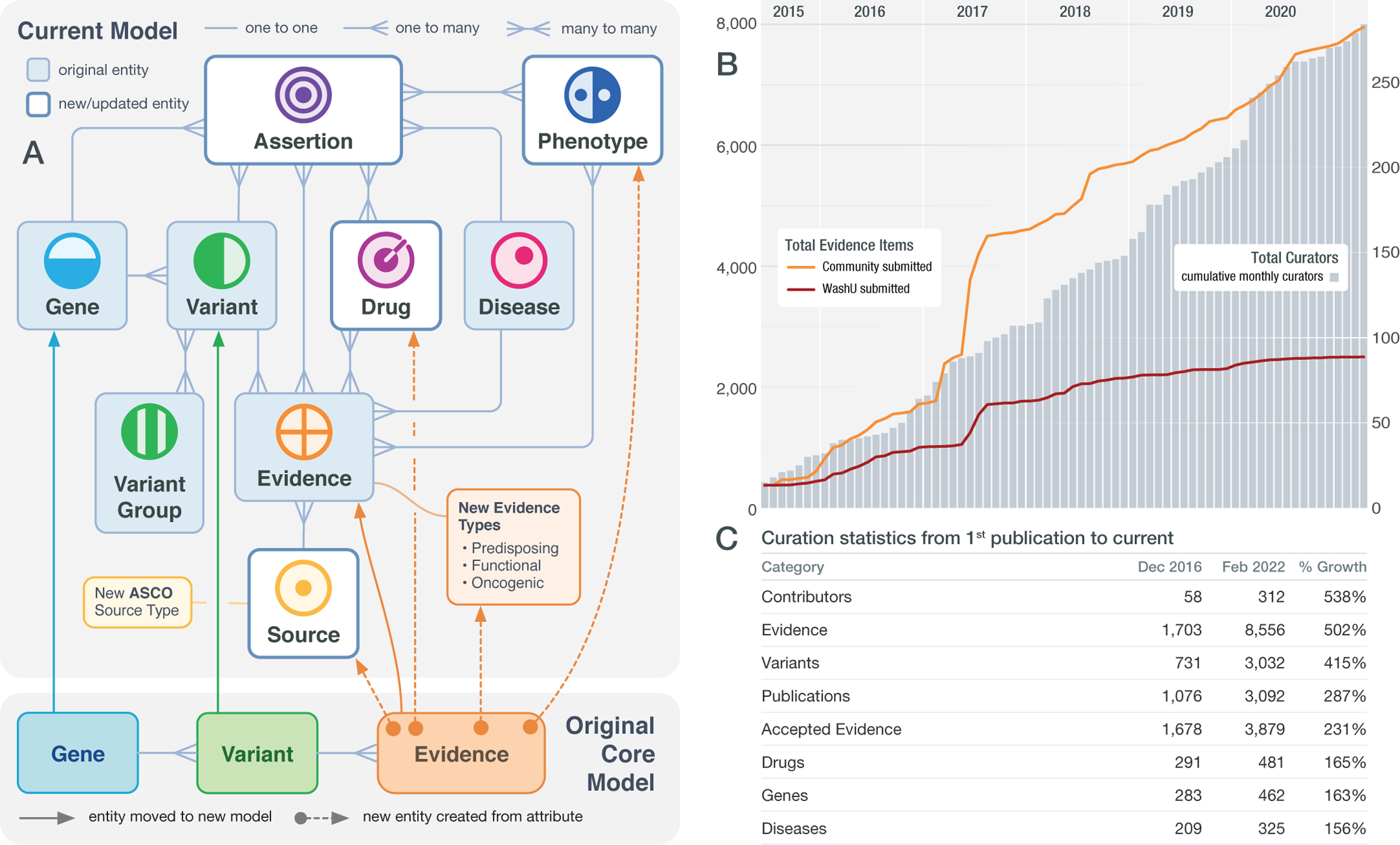

Figure 2. CIViC data model updates and curation activity.

A) Many upgrades have been made to the CIViC knowledgebase including the introduction of Assertions, Source Suggestions, Phenotypes, and linking Drug to a cancer-focused ontology as well as the expansion of Evidence Types and Sources. B) Early contributions to the knowledgebase were performed entirely by internal Curators (Washington University School of Medicine, red). However, by 2017, external curation (Community, orange) exceeded internal contributions. The gap between internal and external contribution continues to widen as new external users adopt and contribute to the knowledgebase. C) Statistics describing growth in multiple parameters of curation in the CIViC knowledgebase, with the largest growth seen in contributors and Evidence Items submitted.

The CIViC team has established collaborations with the Variant Interpretation for Cancer Consortium (cancervariants.org)5, ProteinPaint6, NCI Thesaurus, and many others7–9. Through integration with these other valuable platforms, we enhance the CIViC model, interoperability of cancer-relevant resources, and dissemination of highly curated CIViC data.

Community-driven evolution

Community engagement is additionally facilitated by in-person, biennial Hackathon and Curation Jamborees with community-driven discussion topics in the setting of an “unconference” informal gathering. One previous event explored the utility of germline cancer predisposing variants being represented in the same interface as second hit somatic variants that drive cancer development, and led to a patient-initiated collaboration focused on von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) disease. Somatic, inactivating VHL variants are the most frequent genetic aberration in clear cell renal cell carcinoma (ccRCC), while rare, pathogenic germline VHL variants are associated with VHL disease and cancer predisposition10. Approximately 70% of patients with VHL disease will develop ccRCC, the leading cause of disease-related mortality. Following these community requests at the Curation Jamboree, Predisposing Evidence was developed as a new Evidence Type in the CIViC model, to support germline variants in genes associated with cancer predisposition. As a result, CIViC now contains the largest known database of VHL disease-associated variants. By supporting both germline and somatic variant curation, CIViC is situated to propel understanding of the complex interplay between inherited and acquired genetic events in cancer, an area increasingly recognized in clinical guidelines internationally.

Adaptation to emerging guidelines and types of evidence

Several organizations have published guidelines for evaluating, interpreting, reporting, and cataloging evidence pertaining to cancer variants and their structured representation in databases. The 2017 AMP/ASCO/CAP guidelines for the interpretation and reporting of sequence variants in cancers12 have been incorporated into the CIViC knowledge model11 by developing the CIViC Assertion, which aggregates multiple Evidence Items for a clinical variant classification. Assertions provide a consensus interpretation for the clinical relevance of the variant in the context of a disease and therapy with all underlying Evidence Items displayed, allowing for rapid updating as new evidence emerges. Standard procedures were also developed to support germline variant evidence and interpretation guidelines13 and add Human Phenotype Ontology14 terms to Evidence Items (Figure 2). Aggregation of germline evidence is now supported by Assertions that are given ACMG/AMP classifications13 (e.g., Pathogenic, Likely Pathogenic), which provides clinical relevance of a variant to a disease, along with evidence criteria (e.g., PVS1, PP1, BS1) which assess and codify elements of pathogenicity. We also added Functional and Oncogenic Evidence Types, allowing evidence curation pertaining to a variant’s impact on protein function or tumorigenic properties and setting the stage for adoption of emerging guidelines for variant oncogenicity classification15. Through open-access and state-of-the-art programmatic approaches, expansion of the data model, and collaboration with existing public resources, CIViC is able to fulfill its commitment to adapt to the needs of the community and evolving guidelines.

Future perspectives

The global community of CIViC contributors continues to expand, including many new Curators from the ClinGen SC-CDWG and SC-VCEPs. In collaboration with ClinGen, CIViC is developing structured protocols to become an FDA-recognized public database of genetic variants. Upcoming developments including support for complex variant interactions, variant signatures (e.g., microsatellite instability), and multi-gene copy number and structural variants will address evolving community needs (Figure 2). Since the introduction of CIViC in 20171, we have shown that leveraging the efforts of volunteer biocurators and geneticists through structured and open data is a viable and robust way to tackle cancer variant interpretation and support the democratization of genomics in patient care. This openness and continued access enables engagement of experts and incorporation into external clinical resources.

CIViC is a massively collaborative effort that amplifies the skills of biocurators, bioinformaticians, and developers to produce a knowledgebase equipped to co-evolve with the ever-increasing demands of the cancer variant-related medical literature. However, this work is only as strong and diverse as the community that supports it. Therefore, we invite the community to consider contributing their time, resources, and/or expertise to further enhance this freely available resource.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

EKB is an owner, employee, and member of Geneoscopy Inc. EKB is an inventor of the intellectual property owned by Geneoscopy Inc. KMC is a shareholder in Geneoscopy LLC and has received honoraria from PACT Pharma and Tango Therapeutics. DTR provides consulting for Alacris Theranostics and has received honoraria from Bayer, Eli Lilly, and Bristol-Myers Squibb.

All other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Griffith M et al. CIViC is a community knowledgebase for expert crowdsourcing the clinical interpretation of variants in cancer. Nat. Genet 49, 170–174 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Danos AM et al. Standard operating procedure for curation and clinical interpretation of variants in cancer. Genome Med. 11, 76 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pleasance E et al. Pan-cancer analysis of advanced patient tumors reveals interactions between therapy and genomic landscapes. Nature Cancer 1, 452–468 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Madhavan S et al. ClinGen Cancer Somatic Working Group - standardizing and democratizing access to cancer molecular diagnostic data to drive translational research. Pac. Symp. Biocomput 23, 247–258 (2018). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wagner AH et al. A harmonized meta-knowledgebase of clinical interpretations of somatic genomic variants in cancer. Nat. Genet 52, 448–457 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou X et al. Exploring genomic alteration in pediatric cancer using ProteinPaint. Nat. Genet 48, 4–6 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pratt D et al. NDEx 2.0: A Clearinghouse for Research on Cancer Pathways. Cancer Res. 77, e58–e61 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pagel KA et al. Integrated Informatics Analysis of Cancer-Related Variants. JCO Clin Cancer Inform 4, 310–317 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pawliczek P et al. ClinGen Allele Registry links information about genetic variants. Hum. Mutat 39, 1690–1701 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen SM et al. Von Hippel-Lindau Disease: Genetics and Role of Genetic Counseling in a Multiple Neoplasia Syndrome. J. Clin. Oncol 34, 2172–2181 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Danos AM et al. Adapting crowdsourced clinical cancer curation in CIViC to the ClinGen minimum variant level data community-driven standards. Hum. Mutat 39, 1721–1732 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li MM et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation and Reporting of Sequence Variants in Cancer: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the Association for Molecular Pathology, American Society of Clinical Oncology, and College of American Pathologists. J. Mol. Diagn 19, 4–23 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richards S et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med 17, 405–424 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Köhler S et al. The Human Phenotype Ontology in 2021. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D1207–D1217 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horak P et al. Standards for the classification of pathogenicity of somatic variants in cancer (oncogenicity): Joint recommendations of Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen), Cancer Genomics Consortium (CGC), and Variant Interpretation for Cancer Consortium (VICC). Genet. Med (2022) doi: 10.1016/j.gim.2022.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]