Abstract

Background and aims

Compulsive sexual behavior disorder (CSBD) which includes problematic pornography use (PPU) is a clinically relevant syndrome that has been included in the ICD-11 as impulse control disorder. The number of studies on treatments in CSBD and PPU increased in the last years. The current preregistered systematic review aimed for identifying treatment studies on CSBD and PPU as well as treatment effects on symptom severity and behavior enactment.

Methods

The study was preregistered at Prospero International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42021252329). The literature search done in February 2022 at PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and PsycInfo, included original research published in peer-reviewed journals between 2000 to end 2021. The risk of bias was assessed with the CONSORT criteria. A quantitative synthesis based on effect sizes was done.

Results

Overall 24 studies were identified. Four of these studies were randomized controlled trials. Treatment approaches included settings with cognitive behavior therapy components, psychotherapy methods, and psychopharmacological therapy. Receiving treatment seems to improve symptoms of CSBD and PPU. Especially, evidence for the efficacy of cognitive behavior therapy is present.

Discussion and conclusions

There is first evidence for the effectiveness of treatment approaches such as cognitive behavior therapy. However, strong conclusions on the specificity of treatments should be drawn with caution. More rigorous and systematic methodological approaches are needed for future studies. Results may be informative for future research and the development of specific treatment programs for CSBD and PPU.

Keywords: problematic pornography use, hypersexual behavior, internet-use disorders, therapy, CONSORT, PRISMA

Introduction

Originally, the term “out-of-control sexual behavior” has been used by Bancroft (2008) to describe the loss of control over sexual behaviors such as using telephone hotlines, visiting strip clubs, prostitute visits, excessive sexual intercourses with consenting partners, masturbation, and watching pornography. A mandatory prerequisite to consider out-of-control sexual behavior as a clinically relevant disorder is that despite being confronted with substantial negative consequences the affected person is not able to stop the critical behavior (Brand et al., 2020; World Health Organization, 2020). Although this syndrome has been known for over a century (Krafft-Ebing, 1893), it was not until the popular scientific writings of Carnes in the 1980s that there was a greater interest on this phenomenon (Carnes, 1983) and scientific activity increased. There were different conceptualizations of out-of-control sexual behavior: as a compulsion (Coleman, 1991), as a paraphilia-related disorder (Kafka & Hennen, 1999), as an impulse control disorder (Barth & Kinder, 1987), as hypersexuality (Kafka, 2010), or as behavioral addiction (e.g. Antons & Brand, 2021; Kraus, Voon, & Potenza, 2016). While different conceptualizations of the behavior were discussed over the decades, also the sexual behaviors themselves changed with the increased distribution of pornography via the Internet in the early 2000s (Cooper, 1998; Döring, 2009; Lewczuk, Wójcik, & Gola, 2022), which probably contributed to the fact, that nowadays pornography use is the behavior most often develop into a problematic and pathological manner (Reid et al., 2012).

The clinical relevance of this syndrome suggested an entry in the classification systems. The attempt to integrate out-of-control sexual behavior as hypersexuality disorder into the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013) failed. However, in 2019 the responsible subgroup of the World Health Organization committee decided to add a new diagnosis in the impulse control disorder chapter (World Health Organization, 2020): “Compulsive sexual behavior disorder” (CSBD, ICD-11 Code: 6C72) which is characterized by a persistent pattern of failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges resulting in repetitive sexual behavior. The sexual activity increasingly becomes the central focus in one person's life and other important areas of life are neglected. Furthermore, obligatory for the diagnosis are unsuccessful attempts to reduce or stop the sexual activity despite adverse consequences or deriving little or no satisfaction from it. The problem must exist at least 6 months and cause marked distress or impairment in important areas of functioning. Distress that is entirely related to moral judgments and disapproval about sexual impulses, urges, or behaviors is not sufficient to meet this requirement (World Health Organization, 2020).

Within the current ICD-11 classification, pornography use is mentioned as one behavior besides others (e.g. sexual behavior with others, masturbation, cybersex, and telephone sex) that can become pathologic in CSBD (World Health Organization, 2020). It is discussed whether the similarity of mechanisms involved in the development and maintenance of the pathological use of pornography (most often referred to as problematic pornography use, PPU) and offline sexual activities is comprehensive enough to justify a common classification under the umbrella term CSBD (Antons & Brand, 2021). Especially, specificities with regard to using motives, use expectancies, and reinforcement mechanisms can be assumed (Antons & Brand, 2021). This heterogeneity between behaviors subsumed under the term CSBD and the fact that pornography use is the behavior most often shown by individuals with CSBD (Reid et al., 2012), may have been the reason why two streams of research have developed: one addressing CSBD in general focusing on individuals who pathologically engage in various sexual behaviors of which pornography use is the behavior engaged in most frequently and the other research area focusing on a more homogenous group of individuals presenting PPU without additional problems related to other sexual activities.

Since the diagnostic instruments used varied remarkably in the past (from single items to elaborated questionnaires), prevalence estimates of CSBD and PPU also cover a broader range. Studies reported prevalence rates for CSBD of 4.2–7% in men and 0–5.5% in women (Bőthe et al., 2020b; Briken et al., 2022; Fuss, Briken, Stein, & Lochner, 2019) and similarly for PPU of 3–10% in men and from 1 to 7% in women (Bőthe, Potenza, et al., 2020; Grubbs, Kraus, & Perry, 2019; Lewczuk, Glica, Nowakowska, Gola, & Grubbs, 2020).

One systematic review on interventions for PPU has been published seven years ago (Dhuffar & Griffiths, 2015). Nine relevant studies were identified (including 3 case reports). The interventions ranged from pharmacological treatment studies to acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), and cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). Due to the low compliance with CONSORT reporting guidelines and the small evidence for the positive effect of some psychological and pharmacological treatments, the authors conclude that further research is warranted to establish the efficacy of treatments. The number of treatment studies for CSBD and PPU substantially increased within the last decade (Grubbs et al., 2020), and even more so after the inclusion of CSBD in the ICD-11. To the best of our knowledge there is no current systematic review about treatment and intervention studies on CSBD and PPU, but only narrative reviews showing that research has increased since 2015 (von Franqué, Klein, & Briken, 2015; Grubbs et al., 2020; Hook, Reid, Penberthy, Davis, & Jennings, 2014; Sniewski, Farvid, & Carter, 2018). Accordingly, the current empirical evidence of the efficacy of the used treatments has not been summarized so far. Against this background, we decided to carry out a systematic review of treatments and interventions for CSBD and PPU after preregistration.

Within the systematic review, we aimed for identifying all treatment and intervention studies on CSBD and PPU conducted from January 2000 until end of December 2021. Primary outcomes included measures of symptoms (symptom severity, behavior enactment) and measures of core processes that are assumed to be involved in the development of the disorder, such as cue-reactivity/craving, reward processing inhibitory control, decision making, cognitive bias, and stress response (Brand et al., 2019). The quality of the studies has been assessed with the revised CONSORT 2010 criteria (Moher et al., 2012).

Methods

This systematic review was conducted following the Prisma guidelines for systematic reviews (see Prisma checklist in supplementary material, S1 and S2). The review's protocol was registered in the Prospero International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews with number CRD42021252329 and can be retrieved under https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/. The main methodological considerations and deviations from the protocol are listed below.

Study selection criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion in this review according to seven criteria. First, the studies needed to investigate individuals with CSBD or PPU receiving any type of intervention or treatment (e.g. psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, psychoeducation) to systematically reduce symptom severity, behavioral engagement, or core processes (cue-reactivity/craving; reward processing; inhibitory control; decision making; cognitive bias; stress response). Second, studies were included if CSBD/PPU was identified by screening questionnaires or clinical interviews, as well as when participants self-identified of having CSBD/PPU or were willing to participate in a treatment for CSBD/PPU. Third, studies were excluded if CSBD/PPU was a comorbidity of neurological diseases like frontal lobe syndrome, Parkinson's Disease, restless legs syndrome, or as result of dopaminergic or other medication or drugs. Fourth, studies should at least have a case-control, pre-post interventive or case series design. In addition, correlational designs with measures of change (e.g. in symptom severity) were included. Fifth, only original research published in scholarly peer-reviewed journals were included. Sixth, studies needed to be published between January 2000 (time when the Internet started to dominate the telecommunication and sexuality changed due to the new opportunities; Döring, 2009) and end of December 2021. Seventh, studies needed to be published in English or German language.

Some changes to the protocol were made after the preregistration. Due to delays in the screening procedure the timeframe for the search was enlarged from May 2021 to December 2021. The primary goal of the work was to review literature on treatments for PPU. Since studies have shown that pornography use is one of the behaviors most often shown by individuals with CSBD (Reid et al., 2012), we decided to include studies focusing on CSBD. Due to the small number of relevant studies, we decided to include studies with individuals who were in treatment, self-identified of having CSBD/PPU or willing to participate in a treatment for CSBD/PPU in addition to studies including participants with diagnosed CSBD/PPU. For the same reason we also decided after the preregistration to include studies with correlational designs. When reporting the results, the type of problematic sexual behavior (CSBD or PPU), the screening procedure (clinical interview, questionnaire, self-identified, willing in participating in a treatment study) as well as the type of study design will be reported.

Information sources and search strategy

The literature search was carried out using four online databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, PsycInfo. The databases were last consulted on February 10th, 2022 searching for studies published between January 2000 and end of December 2021. We used a combination of strings describing CSBD/PPU and treatment approaches. The search string should be present in titles or abstracts (see supplementary material S3 for full search strategy of all databases). An example of the search string for the PubMed database can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search string used for the systematic search at Pubmed database

| Search string | |

| CSBD/PPU | ((“porn addict*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“pornography addict*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“addictive porn*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“cybersex addict*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“addictive cybersex*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“sexual addict*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“addictive sex*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“problematic porn*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“problematic sex*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“problematic cybersex*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“hypersex*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“compulsive sex*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“compulsive porn*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“compulsive cybersex*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“sexual compul*” [Title/Abstract])) OR (“impulsive sex*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“impulsive porn*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“impulsive cybersex*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“sexual impuls*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“obsessive sex*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“obsessive porn*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“obsessive cybersex*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“sexual obsess*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“sexual preoccupation” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“sexual hyperactivity” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“out of control sexual” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“paraphilia related” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“non-paraphilic” [Title/Abstract]) AND |

| Treatment | ((“treat*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“therap*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“psychotherap*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“medic*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“train*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“counsel*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“intervent*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“educ*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“psychoeduc*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“drug*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“pharma*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“psychopharma*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“clinical trial” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“12 step*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“twelve step*” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“self-help” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“anonymous” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“case study” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“case series” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“program” [Title/Abstract]) OR (“manual” [Title/Abstract])) AND |

| Date | ((“2000/01/01” [Date - Publication]: “2021/12/31” [Date - Publication])) |

Note. Equivalent search strings were used for the searches in other databases. See supplementary material S3 for full search strategy of all databases.

Study selection

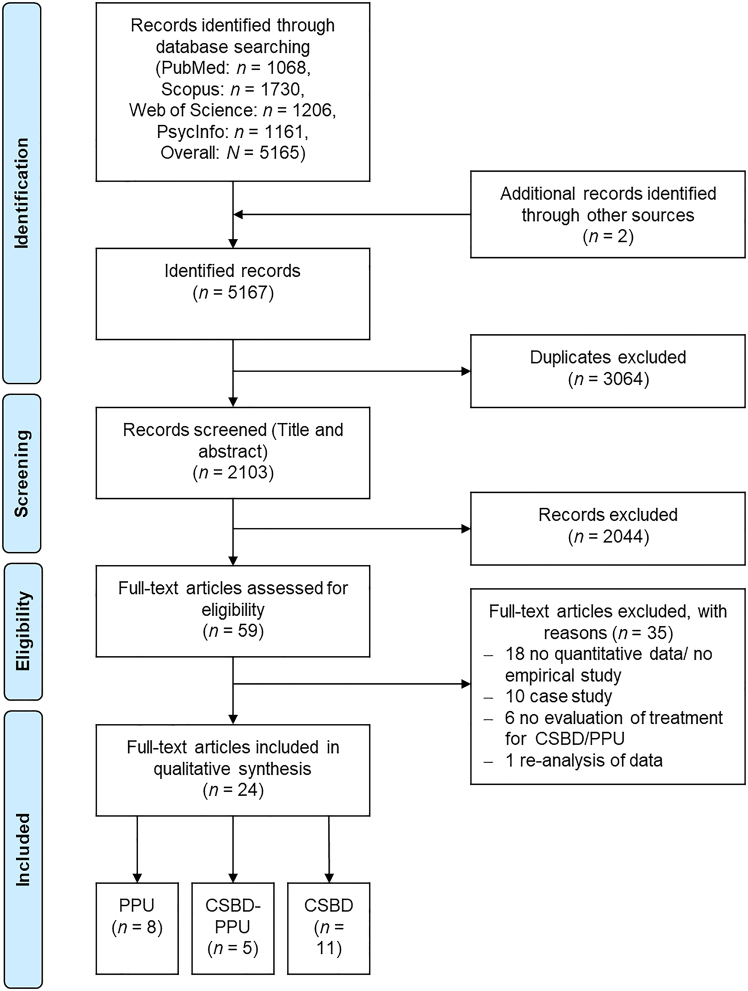

The search and initial screening of studies (title & abstract) was performed by three trained students with Bachelor's degree. The search was independently done at two sites by one team of two students (supervised by SA) and one single student (supervised by RS). Potential inconsistencies/doubts about the eligibility of studies were resolved by discussions involving SA as third instance. Additional screenings of reference lists of the identified studies as well as of the three reviews on the topic (Dhuffar & Griffiths, 2015; Grubbs et al., 2020; Sniewski et al., 2018) were performed by SA. The final selection of studies based on full-texts was done in a consensus meeting between RS and SA, and afterwards approved by all authors. Reasons for exclusions were: if studies were case studies, did not report quantitative data/were no empirical studies, did not include any evaluation of treatment for CSBD/PPU, or were no original research (e.g. the data presented is a re-analysis of data published within another study) (see supplementary material S4 for full list). See Fig. 1 for a full overview on the screening procedure.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram showing the inclusion and exclusion process during the systematic literature search

Data extraction and analysis

Symptom severity was defined in accordance with the ICD-11 criteria for CSBD that widely overlap with those for disorders due to addictive behaviors (e.g. gaming disorder). Measures of symptom severity should assess the persistent pattern of failure to control intense, repetitive sexual impulses or urges resulting in repetitive sexual behavior especially in pornography use and the marked distress resulting from the behavior (see supplementary material S5). Behavior enactment measures should assess the amount, frequency, or duration of behavior enactment either retrospectively or as a daily measure. Only one study reported results on craving as a core process. Therefore, this result is reported but subsumed under secondary outcomes. Further findings for example on comorbid mental disorders, quality of life, and treatment satisfaction are also reported as secondary outcomes. In addition, study characteristics are reported. Results are grouped by psychotherapy with focus on CBT, other psychotherapy approaches, and pharmacological treatment.

For the narrative and quantitative synthesis, the data was extracted by SA and then checked by JE. For the quantitative synthesis, if available means and standard deviations were extracted and Cohen's d and its confidence intervals were estimated for the contrasts baseline vs. post treatment assessment, and baseline vs. follow-up measure (if available for both the treatment and control group). Standard errors were transformed to standard deviations, if no standard deviations were reported. Results are reported in tabular form. Studies were highly heterogenous with regard to types and components of treatments as well as study design (see Table 3). Accordingly, no meta-analysis was done.

Table 3.

Description of interventions

| Intervention | Description of intervention | Studies |

| Psychotherapy with focus on cognitive behavioral therapy | ||

| Psychoeducation | Hall et al. (2020), Hallberg et al. (2017, 2019, 2020), Hardy et al. (2010), Holas et al. (2020), Wan et al. (2000), Wilson and Fischer (2018) | |

| Self-regulation/urge management | Bőthe et al. (2021), Hardy et al. (2010), Hallberg et al. (2017, 2019, 2020) | |

| Mindfulness/meditation | Hallberg et al. (2017, 2020), Holas et al. (2020), Levin et al. (2017), Sniewski et al. (2020) | |

| Awareness of thoughts, emotions, beliefs | Hallberg et al., (2020) | |

| Behavioral activation | Bőthe et al. (2021), Hallberg et al. (2017, 2019, 2020) | |

| Exposure | Hallberg et al., (2017) | |

| Identification of risk situations | ||

| Practice | Orzack et al., (2006) | |

| Readiness to change | Orzack et al., (2006) | |

| Skill training: Development of problem-solving skills/conflict management skills/time management/development of coping strategies | Hallberg et al. (2017, 2019, 2020), Orzack et al. (2006), Wan et al. (2000) | |

| Stimulation of motivation/Motivation for change/motivational interviewing | Bőthe et al., (2021), Hallberg et al. (2017, 2019, 2020), Orzack et al. (2006) | |

| Cognitive restructuring | Bőthe et al., (2021), Hallberg et al. (2017, 2019, 2020), Hardy et al. (2010), Orzack et al. (2006) | |

| Cognitive defusion | Levin et al., (2017) | |

| Acceptance | Crosby and Twohig (2016), Levin et al. (2017), Twohig and Crosby (2010) | |

| Identification of values | Crosby and Twohig (2016), Hallberg et al. (2017, 2019, 2020), Levin et al. (2017), Twohig and Crosby (2010) | |

| Self-as-context | Levin et al., (2017) | |

| Commitment | Crosby and Twohig (2016), Levin et al. (2017), Twohig and Crosby (2010) | |

| Identification of goals | Hallberg et al. (2019, 2020) | |

| Relapse prevention/maintenance program | Bőthe et al., (2021), Hallberg et al. (2017, 2019, 2020), Orzack et al. (2006), Twohig and Crosby (2010), Wan et al. (2000), Wilson and Fischer (2018) | |

| Other psychotherapy approaches | ||

| Art therapy: humanistic, insight-oriented, reflective approach that highlighted personal experience and expression of emotions; drawing tasks address consequences of behavior, public and private self, family dynamics, fantasy and reality of addiction, recovery |

Wilson and Fischer (2018) | |

| Experiential therapy: based on the theory and techniques of psychodrama, roleplaying, with philosophical and theoretical underpinnings in existential humanistic psychology, developmental theory, and models of systemic therapy; includes psychodrama therapy, music therapy, family sculpting and Gestalt techniques |

Klontz et al., (2005) | |

| 12-steps approach: Learning how to deal with the feeling of helplessness and take responsibility for own recovery, undertake value-related goals that bring about a feeling of satisfaction |

Efrati and Gola (2018), Hartman et al. (2012), Wan et al. (2000) | |

| Pharmacological treatment | ||

| Opioid-antagonist: Naltrexone |

Raymond et al. (2010), Savard et al. (2020) | |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI): Citalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, fluvoxamine |

Gola and Potenza (2016), Kafka and Hennen (2000), Wainberg et al. (2006), Raymond et al. (2010) | |

| Serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitor (SARI): Nefazodone |

Coleman et al., (2000) | |

| Psychostimulants: Methylphenidate, dextroamphetamine |

Kafka and Hennen (2000) | |

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias assessment followed the approach used in the systematic review by Dhuffar and Griffiths (2015) and King et al. (2017). Similarly to these two systematic reviews, all studies, including non-randomized controlled trials, were assessed for compliance with the CONSORT 2010 guidelines for randomized trials (Moher et al., 2012). Overall the 37 CONSORT items (assigned to 25 sections) were rated. A two-point grading system was used as scoring: ‘0’ the item was not present at all, ‘1’ the item was partially present, ‘2’ the item was present and clear. The score of ‘0’ was also given in cases in which the item was probably not applicable, e.g. due to the study design. Thus, each study could reach a score between 0 and 74. Higher scores indicate a higher compliance with reporting guidelines and thereby a higher compliance with the methodological gold standard for intervention studies (randomized controlled trials). The evaluation of each study with the CONSORT criteria was done by SA.

Results

Behavior and diagnosis

A total of 24 studies could be identified (see flow-diagram in Fig. 1). Characteristics and main results (primary and secondary outcomes) of these studies are summarized in Table 2. Eight studies explicitly focused on interventions for PPU (Bőthe, Baumgartner, Schaub, Demetrovics, & Orosz, 2021; Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Gola & Potenza, 2016; Holas, Draps, Kowalewska, Lewczuk, & Gola, 2020; Levin, Heninger, Pierce, & Twohig, 2017; Orzack, Voluse, Wolf, & Hennen, 2006; Sniewski, Krägeloh, Farvid, & Carter, 2020; Twohig & Crosby, 2010). Internet-related sexual behaviors as investigated by Orzack et al. (2006) are subsumed under this category. Five further studies focused on treatments for CSBD with reporting that PPU is the main problem or one of the main problems (Hallberg et al., 2017; Hardy, Ruchty, Hull, & Hyde, 2010; Kjellgren, 2018; Raymond et al., 2010; Savard et al., 2020). The majority of studies (n = 12) investigated CSBD without further information on the extent of pornography use (Coleman, Gratzer, Nesvacil, & Raymond, 2000; Efrati & Gola, 2018; Hallberg et al., 2019, 2020; Hall, Dix, & Cartin, 2020; Hartman, Ho, Arbour, Hambley, & Lawson, 2012; Kafka & Hennen, 2000; Klontz, Garos, & Klontz, 2005; Wainberg et al., 2006; Wan, Finlayson, & Rowles, 2000; Wilson & Fischer, 2018).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies and main results

| Study/study site | Sexual behavior/diagnostic procedure | Sample/study design | Main results | Treatment |

| Psychotherapy with focus on cognitive behavioral therapy | ||||

|

Bőthe et al. (2021); Switzerland, Hungary |

PPU; self-identified/willing in participating in an online treatment for PPU | TG: n = 123, dropout: 89%, M

age = 33 ± 11.5, 95.9% male, 74.8% heterosexual, 5.7% homosexual, 13.8% bisexual; CG: Waitlist, n = 141, dropout: 44.7%, M age = 33 ± 9.9, 96.5% male, 72.3% heterosexual, 4.3% homosexual, 21.3% bisexual; RCT; Within-between subject design; Measurements: BL, post |

↓ symptom severity [PPCS] (post-BL: TG < CG); ↓ behavior engagement [freq] (post-BL: TG < CG); ↔ behavior engagement [dur] (post-BL: TG = CG); ↓ craving (post-BL: TG < CG) ↔ moral incongruency (post-BL: TG = CG); ↑ pornography-related self-efficacy (post-BL: TG > CG) |

Web-based self-help tool including six core modules developed to reduce PPU based on motivational interviewing, CBT, mindfulness, and wise social-psychological intervention techniques; individual therapy; 6 weeks; 6 modules + booster module after 1 month; 45–60 min per module; digital therapy. |

|

Crosby and Twohig (2016); United States |

PPU; clinical interview, criteria: (a) engaged in problematic Internet pornography use for more than 6 months, (b) viewing frequency of at least two sessions per week, on average, for the month previous to enrolling in the study, (c) experiencing significant distress and/or functional impairment in his life; and (d) at least one unsuccessful attempt at stopping |

Overall (TG and CG): M

age = 29 ± 11.4, 100% male, sexual orientation: n/a; TG: n = 14; CG: Waitlist with subsequent therapy, n = 13 RCT; Within-between subject design; Measurements: BL, post, 3FU |

↓ symptom severity [SCS] (TG: BL > post, CG: BL = post, overall: BL > post/3FU); ↓ behavior enactment [am] (TG: BL > post; CG: BL = post); ↓ negative outcomes of sex. behavior (TG: BL > post, CG: BL = post, overall: BL > post/3FU); ↔ quality of life (TG: BL = post, CG: BL< post, BL < post) |

Modified ACT manual for PPU aiming to help the client determine effective strategies for responding to urges, to practice using these strategies outside of session, to gradually decrease pornography use and to increase occurrence of high quality-of-life activities; individual-therapy, 12 sessions à 1 h. |

| Hall et al. (2020); United Kingdom | CSBD; current clients, SASAT [no-cut-off criteria] | TG: N = 119, age: n/a, gender: n/a, sexual orientation: n/a; Within subject design, descriptive; Measurements: BL, post, 3FU, 6FU |

Only descriptive results

behavior enactment (BL vs. 3FU vs. 6FU: 82%/4%/11% answered most of the time/often); obsessive sexual thoughts (76%/80% report having fantasies/intrusive thoughts most of the time/often at BL, 7.5%/17% at 4FU, 13/19 at 6FU); psychological distress (change from BL to 3FU of 58% improvement, from Bl to 6FU 60% improvement) |

Psycho-educational program following the precept of ‘growth through knowledge’ and the philosophy of the CHOICE Recovery Model which incorporates principles from CBT, ACT, psychodynamic and relational psychotherapy theory and positive psychology. The program aims at giving clients greater insight into the root causes of their compulsive behavior, practical skills for preventing relapse, positive goals for the future and motivation to change, along with a long-term support network; group-therapy; 6 days. |

| Hallberg et al. (2017); Sweden | CSBD predominantly PPU (90% of participants); Kafka-criteriaa, validated through clinical interview | TG: Final n = 10, M

age = 39 ± 8.1, 100% males, drop out: n = 5, sexual orientation: n/a; Within subject design; Measurements: BL, mid, post, 3FU, 6FU |

Non-parametrical tests

↓ symptom severity [HD:CAS] (BL > mid/post/3FU/6FU); ↓ symptom severity [HDSI] (BL > mid/post/3FU); treatment satisfaction (70% high level of satisfaction) |

CBT program targeting different criteria of CSBD. The seven models include viewing CSBD from cognitive, behavioral, and functional perspectives, stress and time-management techniques, cognitive restructuring and diffusion techniques addressing negative thoughts and beliefs, identification of values, and relapse prevention; group-therapy, 7 weeks, 7 or 10 sessions à 2.5 h. |

| Hallberg et al. (2019); Sweden | CSBD; HDSI, Kafka-criteriaa validated in clinical interview | TG: BL: n = 58, M

age = 40 ± 12, 100% males, sexual orientation: n/a, mid: n = 52, post: n = 47, 3FU: n = 21, 6FU: n = 14; CG: During waitlist period BL: n = 54, M age = 40 ± 11, 100% males, sexual orientation: n/a, mid: n = 52, post: n = 50; Waitlist sample during treatment BL: n = 48, mid: n = 40, post: n = 35, 3FU: n = 22, 6FU: n = 11; RCT; Within-between subject design; Measurements: BL, mid, post, 3FU, 6FU |

↓ symptom severity [HD:CAS] (TG: BL > mid/post; post: TG < CG); ↓ symptom severity [SCS] (mid/post: TG < CG; BL > mid/post < 3FU/6FU); ↓ psychological distress (TG: BL > mid/post/3FU/6FU; mid/post: TG < CG); ↓ depression (TG: BL > mid > post > 3FU/6FU; mid/post: TG < CG); ↔ treatment satisfaction (TG = CG) |

CBT program as described in Hallberg et al. (2017); group-therapy; 7 weeks; 7 sessions à 2.5 h. |

| Hallberg et al. (2020); Sweden | CSBD with/without paraphilia; HDSI cut-off, clinical interview | TG: N = 36, M

age = 39 ± 8.5, 100% males, sexual orientation: n/a; Within subject design; Measurements: BL, mid, post, 3FU |

↓ symptom severity [HBI-19] (BL > mid/post/3FU); ↓ symptom severity [HD:CAS] (BL > post); ↓ symptom severity [SCS] (BL>mid/post/3FU); ↓ psychological distress (BL>mid/post/3FU); ↓ depression (BL>mid/post/3FU); ↔ paraphilic disorders (BL = mid = post = 3FU); Treatment satisfaction (88% high level of satisfaction) |

Internet-based CBT that is based on the CBT program by Hallberg et al. (2017), individual-therapy, 12 weeks, 10 modules, internet-based. |

| Hardy et al. (2010); United States | CSBD with emphasis on PPU and masturbation; self-identified/willing in participating in an online treatment for CSBD/PPU | TG: N = 138, M

age = 38 ± 12.4, 97% males, 91% heterosexual cross-sectional, retrospective evaluation |

Retrospective pre-post comparison

↓ behavior engagement; ↑ perceived recovery; ↓ obsessive sex. thoughts |

CBT program aiming to reduce causes of distress by self-paced, psychoeducation modules, delivered online through text, graphics, video, audio, and interactive exercises; individual self-help; 10 modules; online program. |

| Holas et al. (2020); Poland | PPU; clinical interview, fulfilling 4 of 5 Kafka criteriaa | TG: N = 13, M

age = 33 ± 5.74, 100% male, sexual orientation: n/a; Within subject design; Measurements: BL, post |

↔ symptom severity [BPS] (BL = post); ↓ behavior enactment (pornography use: BL > post); ↓ depression (BL > post); ↔ anxiety (BL = post); ↔ obsessive compulsive disorders (BL = post) |

Mindfulness-based intervention aimed at, among other things, reducing craving and negative affect—i.e. processes that are implicated in the maintenance of problematic sexual behaviors; group-therapy; 8 weeks; 8 sessions à 2 h. |

| Levin et al. (2017); United States | PPU; self-identified, treatment seeking; phone screening | TG: N = 19, M

age

= 23 ± 4.5, 90% male, sexual orientation: n/a, post: n = 11; Within subject design; Measurements: BL, post, 2FU |

↓ symptom severity [CPUI] (BL > post); ↓ behavior enactment [am] (BL > post); ↓ negative outcomes of sex. behavior (BL > post); ↔ quality of life (BL = post = 2FU); ↔ psychological flexibility (BL = post = 2FU) |

ACT self-help program for PPU in which clients work through a self-help book that emphasizes core ACT components and related skills including acceptance, cognitive defusion, mindfulness of the present, self-as-context, values, and committed action; 8 weeks; 15 chapters of self-help book. |

| Orzack et al. (2006); United States | PPU; Internet-related sexual behaviors, diagnosis with paraphilia not otherwise specified, impulse control disorder not otherwise specified | TG: N = 35, M

age = 45 ± 5.74, 100% male, sexual orientation: n/a Within subject design; Measurements: BL, mid, post |

↔ problematic use of computers (BL = Post); ↑ quality of life (BL < post); ↓ depression (BL > post) |

Treatment combined Readiness to Change, CBT, and Motivational Interviewing interventions within a group-therapy setting; 16 weeks; 16 sessions. |

| Sniewski et al. (2020); New Zealand | PPU; self-identified/willing in participating in a self-help treatment for PPU | TG: N = 12; Drop-out: n = 1; M age = 32 ± 8.9; 100% male; 100% heterosexual Within subject design; Measurements: BL, weekly assessment until post |

Only single case analyses

7 of 11 participants showed significant improvement in symptom severity [PPCS]; 2 of 11 participants showed significant improvement in behavior enactment [dur] |

Intervention included guided and unguided meditation sessions that were applied via an online platform; individual self-help intervention; overall 12 weeks; baseline between 2 and 5 weeks; intervention between 10 and 7 weeks; online meditation audio-tapes. |

| Twohig and Crosby (2010); United States | PPU; clinical interview, criteria: (a) viewing pornography more than three times a week on some weeks and (b) the viewing causes difficulty in general life functioning | TG: N = 6, M

age = 27 ± 6.1, 100% male, 83% heterosexual, 16% unsure Case series; Within design; Measurements: BL, post, 3FU |

Only descriptive results

5 of 6 showed reduced behavior enactment [freq] (BL vs. post); increase in quality of life (from BL to post 8%, from BL to 3FU 16.4%); decrease in obsessive compulsive disorder (from BL to post 51%, from BL to 3FU 68%) |

Modified ACT manual for PPU including core components of ACT such as acceptance, values, committed action, defusion, and self as a context; individual-therapy; 8 sessions. |

| Wan et al. (2000); Canada | CSBD (SAST, criteria unclear) | TG: N = 59, M

age = 43, 70% male; sexual orientation: n/a Within subject design; Measurements: post 0.8–43 months |

Only descriptive results

behavior enactment: 29% stayed abstinent/64% relapse |

Sexual dependency program consisting of core addiction treatment components and specialized sexual dependency components. The approach included a 12-steps approach development of knowledge and skills for recovery; group and individual therapy; M duration = 32 days, 2–12 h therapy/psychoeducation and 12-steps approach. |

| Wilson and Fischer (2018); United States | CSBD; criteria for hypersexual behavior [unclear which concrete criteria], individuals in treatment |

CBT subgroup: n = 27; Art therapy subgroup n = 27; overall: M age = 43 ± 10.8; 93% male; sexual orientation: n/a Within-between subject design; Measurements: BL, post, 3FU |

↓ symptom severity [HBI-19] (CBT: BL > post/3FU; art therapy: BL > post/3FU; post/3FU: art therapy = CBT); ↓ shame (CBT: BL > post/3FU; art therapy: BL > post/3FU; post/3FU: art therapy = CBT) |

CBT or art-therapy aiming at reducing shame and CSBD symptoms. Both interventions addressed the same topics including denial, the nature of sex addiction and surrender to the process; group-therapy; 6 weeks. |

| Other psychotherapy approaches | ||||

| Efrati and Gola (2018); Israel | CSBD; self-identified, participants of Sexoholics Anonymous | TG: N = 97, M

age = 30 ± 7.3, 100% male, sexual orientation: n/a Cross-sectional design |

Number of steps is correlated with (-) symptom severity [I-CSB]; (+) self-regulation; (-) psychological distress |

12-step program of Sexaholics Anonymous, group-therapy. |

| Hartman et al. (2012); Canada | CSBD with/without SUD; in treatment, SAST-R [no cut-off criteria] | TG: Subgroup without SUD n = 21, subgroup with SUD n = 36; Overall: M age = 39 ± 8.81, 91.2% males, sexual orientation: n/a Within subject design; Measurements: BL, post, 6FU |

↓ symptom severity [CSBI] (with and without SUD: BL > 6FU); ↑ quality of life (with and without SUD: BL < 6FU); ↓ substance use (with SUD: BL < 6FU) |

Inpatient treatment program that includes 12-steps approach, physical health education and training, psychosocial education, recovery planning; group- and individual therapy. |

| Kjellgren (2018); Sweden | CSBD; SAST [cut-off: core score ≥6]; 27% report main problem with pornography use | TG: N = 28, M

age = 40 ± 11.5, 96% male, 96% heterosexual Within subject design; Measurements: BL, post, 10FU |

↓ symptom severity [SAST] (BL > post); ↓ psychological distress (BL < 10FU); treatment satisfaction (100% positive/very positive) |

Treatment provided by specialized social welfare units without any standardized manual; methods applied were psychodynamic, cognitive-behavioral, or system-based approaches, individual therapy, about 25.6 sessions à 45–60 min. |

| Klontz et al. (2005); United States | CSBD; diagnosis, in treatment | TG: N = 38, M

age = 44 ± 8.9, 73% male, 79% heterosexual Within subject design; Measurements: BL, post, 6FU |

↓ symptom severity [GSBI] (sexual obsession: BL > post/6FU; discordance: BL/post > 6FU); ↓ psychological distress (BL > post > 6FU); ↓ anxiety (BL/post < 6FU); ↓ depression (BL > post); ↓ obsessive-compulsive disorder (BL > post) |

Brief residential, multimodal experiential group therapy treatment program including psychodrama (32 h), psychoeducation (12 h), mindfulness-based technique/meditation (16 h); group-therapy; attending at five 8-day-retreats within 12 months. |

| Pharmacological treatment | ||||

| Coleman et al. (2000); United States | CSBD; DSM-IV criteria for sexual disorder not otherwise specified, in treatment | TG: N = 14, M

age = 45, 100% males, sexual orientation: n/a Retrospective design; Measurements: retrospective evaluation through therapists |

Only descriptive results

self-regulation (55% report good control over obsessive thoughts; 45% report remission of obsessive thoughts) |

Nefazodone (Mdose = 200 mg/day, min-max dose: 50–400 mg/day), treatment duration about 13.4 months, parallel individual and group-CBT. |

| Gola and Potenza (2016); Poland | PPU; treatment seeking with preoccupations/urges, numerous failed quit attempts, and significant distress related to PPU and masturbation |

TG: N = 3, M

age = 30 ± 4.64, 100% male, 100% heterosexual Case study design; Measurements: weekly assessment, 3FU |

Only descriptive results

behavior enactment [am]: short-term reduction; new compulsive sexual behaviors after 3 months; anxiety: significant reductions after ten weeks |

SSRI (paroxetine; dose = 20 mg/day), in addition to CBT. |

| Kafka and Hennen (2000); United States | Paraphilias: DSM-IV criteria, clinical interview; CSBD: Kafka-criteria, clinical interview |

TG: N = 26, Paraphilia: n = 14, CSBD: n = 12, age: n/a, 100% males, 73.1% heterosexual Within subject design; Measurements: BL, post-SSRI, post-SSRI + psychostimulant |

Combined analysis for individuals with paraphilias and CSBD

↓behavior enactment [am] (BL > post-SSRI > post-SSRI + psychostimulant) |

8 weeks; SSRI (fluoxetine 49 mg/day: n = 19, sertraline 110mg/day: n = 3, paroxetine 35 mg/day: n = 2, fluvoxamine 100 mg/day: n = 2) and psychostimulant (methylphenidate SR 40 mg/day: n = 25, dextroamphetamine: n = 1). |

| Raymond et al. (2010); United States | Paraphilic and non-paraphilic CSBD, 58% CSBD, 31% PPU; individuals with diagnosis in treatment, criteria unclear | TG: N = 19, M

age = 4 4.1 ± 9.4, 100% males, 73.3% heterosexual Measurements: Investigation during treatment |

Only descriptive results

89% report reduction in symptom severity [S-SAS] |

Individual or group therapy and medical treatment with naltrexone (first 25–50 mg/day, after 1–2 weeks 100 mg/day). 79% also took SSRI or SNRI (venlafaxin). Treatment duration 2 months–2.3 years. |

| Savard et al. (2020); Sweden | CSBD, 85% with PPU; ICD-11 criteria and 3 of 5 A-criteria and 1 of 2 B-criteria DSM-5 conceptualization for hypersexual disorder | TG: N = 20, M

age = 38.8 ± 10.3, 100% males, 70% heterosexual Within subject design; Measurements: BL, mid, post, 1FU |

↓ symptom severity [HD:CAS] (BL > mid/post/1FU); ↓ symptom severity [HBI-19] (BL > mid/post/1FU); ↓ symptom severity [SCS] (BL > mid/post/1FU) |

4 weeks, naltrexone (25–50 mg/day). |

| Wainberg et al. (2006); United States | CSBD; YBOCS-CSB [no cut-off criteria], CSBD [no cut-off criteria] | TG: n = 13; CG: placebo, n = 15 Overall: M age = 36 ± 8.2, 100% males, 100% homo-/bisexual RCT; Within-between design; Measurements: BL, post |

↔ symptom severity [YBOCS-CSB] (post: TG = CG); ↔ symptom severity [CSBI] (post: TG = CG); ↓ behavior enactment [am] (pornography, masturbation) (post: TG < CG); ↓ sexual desire (post: TG < CG) |

12 weeks, citalopram. |

Note. Primary outcomes are highlighted in bold. a Kafka criteria as defined in Kafka (2010). 1FU/2FU/3FU/6FU/10FU = 1/2/3/6/10 months follow-up assessment, 6wFU = six-week follow-up assessment, ACT = acceptance and commitment therapy, am = amount of time spent on sexual behaviors, BL = baseline assessment, BPS = Brief Pornography Screener (Kraus et al., 2020), CBT = cognitive behavior therapy, CG = control group, CPUI = Cyber-Pornography Use Inventory (Grubbs, Sessoms, Wheeler, & Volk, 2010), CSBD = compulsive sexual behavior disorder, CSBI = Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory (Coleman, Miner, Ohlerking, & Raymond, 2001), dur = duration of behavior enactment, freq = frequency of behavior enactments, GSBI = Garos Sexual Behavior Inventory (Garos & Stock, 1998), HBI-19 = Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (Reid, Garos, & Carpenter, 2011), HD:CAS = Hypersexual Disorder: Current Assessment Scale (American Psychiatric Association's DSM-5 workgroup on sexual and gender identity disorders), HDSI = Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (Kafka, 2013), I-CSB = Individual-based CSB (Efrati & Mikulincer, 2018), mid = assessment in the middle of treatment, post = post treatment assessment, PPU = problematic pornography use, PPCS = Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (Bőthe et al., 2018), RCT = randomized controlled trial, TG = treatment group, SAST = Sexual Addiction Screening Test (Carnes, Green, & Carnes, 2010), SCS = Sexual Compulsivity Scale (Kalichman & Rompa, 1995), S-SAS = Sexual symptom assessment scale (Raymond, Lloyd, Miner, & Kim, 2007), YBOCS-CSB = Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale – Compulsive sexual behavior (Wainberg et al., 2006). ↓ statistically significant decrease in outcome, ↑ statistically significant increase in outcome, ↔ no statistically significant change in outcome.

Some studies used clinical interviews for diagnoses (Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Hallberg et al., 2017, 2019, 2020; Holas et al., 2020; Orzack et al., 2006; Twohig & Crosby, 2010), others used screening instruments (Hall et al., 2020; Hallberg et al., 2020; Hartman et al., 2012; Kjellgren, 2018; Wan et al., 2000; Wainberg et al., 2006). However, it is often unclear which concrete criteria have been applied (Hall et al., 2020; Hartman et al., 2012; Kjellgren, 2018; Klontz et al., 2005; Orzack et al., 2006; Raymond, Grant, & Coleman, 2010; Wainberg et al., 2006; Wan et al., 2000; Wilson & Fischer, 2018). Studies reporting concrete criteria reference to the Kafka-criteria (Hallberg et al., 2017, 2019, 2020; Holas et al., 2020; Kafka & Hennen, 2000; Savard et al., 2020), ICD-11 CSBD criteria (Savard et al., 2020), or self-defined criteria (Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Gola & Potenza, 2016; Twohig & Crosby, 2010). Some studies included individuals with self-identified CSBD/PPU, individuals seeking treatment because of CSBD/PPU, or individuals willing to participate in a study that incorporates a treatment on CSBD/PPU (Bőthe et al., 2021; Efrati & Gola, 2018; Hardy et al., 2010; Levin et al., 2017; Sniewski et al., 2020).

Sample characteristics

Overall within the identified studies, 1058 individuals received treatment for CSBD/PPU, 977 participants received a form of psychotherapy (757 received CBT focused therapy), and 81 received pharmacological treatment. A total of 223 participants have been in a waitlist or placebo control group. Of these participants 67 received the treatment subsequently. Most participants were male (94.83%) and were heterosexual (84.08%), with mean ages ranged between 27 and 45 years. However only 46% of studies reported sexual orientation. Most (90.17%) participants of studies reporting information about ethnicity were Caucasian/white.

In some studies participants were excluded before treatment if they took any psychoactive medication (Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Hallberg et al., 2019, 2020; Holas et al., 2020; Savard et al., 2020; Wainberg et al., 2006), were in an ongoing psychotherapy (Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Hallberg et al., 2017, 2019, 2020; Savard et al., 2020), or had comorbid disorders such as paraphilias (e.g., voyeurism, exhibitionism, frotteurism, sadism) (Coleman et al., 2000; Hallberg et al., 2017, 2019), pedophilia (Hallberg et al., 2017, 2019, 2020), severe mood disorders (anxiety, depression) (Hallberg et al., 2017, 2019, 2020; Holas et al., 2020; Savard et al., 2020; Sniewski et al., 2020; Wainberg et al., 2006), substance abuse/dependence (Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Hallberg et al., 2017, 2019, 2020; Holas et al., 2020; Savard et al., 2020; Wainberg et al., 2006), obsessive-compulsive disorders (Holas et al., 2020), psychotic disorders (Holas et al., 2020; Savard et al., 2020), personality disorders (Hall et al., 2020), intellectual or developmental disability (Crosby & Twohig, 2016), or suicidality (Wainberg et al., 2006). Individuals were also excluded in some studies if they had committed sexual offenses, such as sexual coercion or used illegal pornographic material (Hallberg et al., 2019; Hall et al., 2020; Savard et al., 2020; Sniewski et al., 2020).

Most studies reported relationship status/civil status (Bőthe et al., 2021; Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Efrati & Gola, 2018; Gola & Potenza, 2016; Hallberg et al., 2017, 2019, 2020; Hardy et al., 2010; Hartman et al., 2012; Kafka & Hennen, 2000; Kjellgren, 2018; Klontz et al., 2005; Levin et al., 2017; Savard et al., 2020; Twohig & Crosby, 2010; Wan et al., 2000; Wilson & Fischer, 2018), ethnicity/race/country of origin (Bőthe et al., 2021; Coleman et al., 2000; Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Efrati & Gola, 2018; Gola & Potenza, 2016; Hallberg et al., 2020; Hardy et al., 2010; Holas et al., 2020; Kafka & Hennen, 2000; Klontz et al., 2005; Levin et al., 2017; Savard et al., 2020; Sniewski et al., 2020; Twohig & Crosby, 2010; Wilson & Fischer, 2018), education (Bőthe et al., 2021; Efrati & Gola, 2018; Hallberg et al., 2017, 2019, 2020; Hardy et al., 2010; Hartman et al., 2012; Klontz et al., 2005; Savard et al., 2020; Sniewski et al., 2020; Twohig & Crosby, 2010; Wainberg et al., 2006; Wan et al., 2000; Wilson & Fischer, 2018), and occupation (Efrati & Gola, 2018; Gola & Potenza, 2016; Hallberg et al., 2017, 2019, 2020; Hartman et al., 2012; Kjellgren, 2018; Savard et al., 2020; Sniewski et al., 2020; Wan et al., 2000; Wainberg et al., 2006). Three studies reported religious affiliation (Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Hardy et al., 2010; Levin et al., 2017).

Study context

The majority of studies were conducted in the United States (Coleman et al., 2000; Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Hardy et al., 2010; Kafka & Hennen, 2000; Klontz et al., 2005; Levin et al., 2017; Orzack et al., 2006; Raymond et al., 2010; Twohig & Crosby, 2010; Wainberg et al., 2006; Wilson & Fischer, 2018). Further studies were conducted in Sweden (Hallberg et al., 2017, 2019, 2020; Kjellgren, 2018; Savard et al., 2020), Poland (Gola & Potenza, 2016; Holas et al., 2020), Canada (Hartman et al., 2012; Wan et al., 2000), New Zealand (Sniewski et al., 2020), Switzerland/Hungary (Bőthe et al., 2021) and the UK (Hall et al., 2020). Overall, 14 studies were conducted in public or private in- and outpatient clinics or (university) hospitals (Coleman et al., 2000; Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Gola & Potenza, 2016; Hall et al., 2020; Hallberg et al., 2017, 2019; Hartman et al., 2012; Kafka & Hennen, 2000; Orzack et al., 2006; Raymond et al., 2010; Savard et al., 2020; Twohig & Crosby, 2010; Wainberg et al., 2006; Wilson & Fischer, 2018). One study was conducted in social welfare centers (Kjellgren, 2018) and one study was conducted in a private meditation center (Holas et al., 2020). Four studies used digital/online interventions (Bőthe et al., 2021; Hallberg et al., 2020; Hardy et al., 2010; Sniewski et al., 2020) and one intervention was a self-help intervention including working through a therapeutic manual (Levin et al., 2017).

Intervention types

An overview on treatment approaches can be found in Table 3. Most studies used psychotherapy interventions (n = 18) integrating classical and new-wave CBT components such as psychoeducation, motivation, behavioral activation, cognitive restructuring, cue exposure/urge management, mindfulness, and identification of values or commitment. Further approaches were art therapy (n = 1), experiential therapy (n = 1), and a 12-steps approach (n = 3). In six studies participants were treated with psychopharmacological therapy. In three studies psychopharmacological therapy was conducted simultaneously to psychotherapy. Most psychotherapy intervention were conducted in groups (Hall et al., 2020; Hallberg et al., 2017, 2019; Holas et al., 2020; Klontz et al., 2005; Orzack et al., 2006; Wilson & Fischer, 2018), but some were individual interventions (Bőthe et al., 2021; Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Hallberg et al., 2020; Hardy et al., 2010; Kjellgren, 2018; Levin et al., 2017; Sniewski et al., 2020; Twohig & Crosby, 2010). Two studies had both group- and individual therapy components (Hartman et al., 2012; Wan et al., 2000). It was not always clear whether full abstinence or a controlled use/behavior execution was the treatment aim. Abstinence was the explicit aim of three studies (Efrati & Gola, 2018; Hartman et al., 2012; Wan et al., 2000), although abstinence was defined differently, and in one study it was even defined individually for each participant (e.g. aiming at no solitary or dyadic sexual activity outside of formal marriage). Within the study by Twohig and Crosby (2010) the decision if participants aimed for full abstinence or controlled use, was made by the participants themselves.

Primary outcomes

The measures used to assess changes in symptom severity are very heterogenous. Overall, 14 different scales have been used (Table 4). These measures assessed ICD-11 related criteria for CSBD at least in some parts (Table S4), however, they also assessed further facets of problematic sexual behavior that are not subsumed under the diagnostic criteria for CSBD. Orzack et al. (2006) used a more general scale on problematic use of computers. Since this scale assesses a more general problematic use of computers, this scale was not categorized as primary outcome for the current review.

Table 4.

Outcome Measures

| Outcome Measure | Studies | |

| Primary outcomes: Symptoms and behavioral engagement | ||

| Symptom severity | Brief Pornography Screener (BPS) (Kraus et al., 2020) | Holas et al., (2020) |

| Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI) (Coleman et al., 2001) | Hartman et al. (2012), Wainberg et al. (2006) | |

| Cyber-Pornography Use Inventory (CPUI) (Grubbs et al., 2010) | Levin et al., (2017) | |

| Garos Sexual Behavior Inventory (GSBI) (Garos & Stock, 1998) | Klontz et al., (2005) | |

| Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (HBI-19) (Reid et al., 2011) | Hallberg et al. (2020), Savard et al. (2020), Wilson and Fischer (2018) | |

| Hypersexual Disorder: Current Assessment Scale (HD:CAS, developed by American Psychiatric Association's DSM-5 workgroup on sexual and gender identity disorders) |

Hallberg et al. (2017, 2019, 2020), Savard et al. (2020) | |

| Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (HDSI) (Kafka, 2013) | Hallberg et al., (2017) | |

| Individual-based CSB (I-CSB) (Efrati & Mikulincer, 2018) | Efrati and Gola (2018) | |

| Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (PPCS) (Bőthe et al., 2018) | Bőthe et al. (2021), Sniewski et al. (2020) | |

| Sexual Addiction Screening Test (SAST) (Carnes et al., 2010) | Kjellgren (2018) | |

| Sexual Symptom Assessment Scale (S-SAS) (Raymond et al., 2007) | Raymond et al., (2010) | |

| Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale – Compulsive sexual behavior (YBOCS-CSB) (Wainberg et al., 2006) | Wainberg et al., (2006) | |

| Sexual Compulsivity Scale (SCS) (Kalichman & Rompa, 1995) | Crosby and Twohig (2016), Hallberg et al. (2020), Savard et al. (2020) | |

| Behavior engagement | Retrospective evaluation of amount, frequency, or duration engaged sexual behaviors (e.g. sexual activities, pornography use, masturbation), fantasies, thoughts before and after the treatment (different timeframes were used in different studies) | Bőthe et al. (2021), Hall et al. (2020), Hardy et al. (2010), Holas et al. (2020), Levin et al., (2017) |

| Daily/weekly self-monitoring of frequency of masturbation | Gola and Potenza (2016), Twohig and Crosby (2010), Sniewski et al. (2020) | |

| Daily Pornography Viewing Questionnaire (DPVQ) (Crosby & Twohig, 2016) |

Crosby and Twohig (2016) | |

| Sexual outlet inventory (Kafka & Prentky, 1992) | Kafka and Hennen (2000) | |

| Timeline follow back (Weinhardt et al., 1998) | Wainberg et al., (2006) | |

| Self-reported, post-treatment relapse/abstinence | Wan et al., (2000) | |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Sexual desire | Arizona sexual experience scale (McGahuey et al., 2000) | Wainberg et al., (2006) |

| Craving | Pornography Craving Questionnaire (Kraus & Rosenberg, 2014) |

Bőthe et al., (2021) |

| Obsessive sexual thoughts | 10 items; e.g., “I feel out of control of my sexual thoughts” | Hardy et al., (2010) |

| Fantasies about acting out behavior, intrusive thoughts about behavior | Hall et al., (2020) | |

| Negative outcomes of sexual behavior | Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes of Sexual Behavior Scale (CBOSB) (McBride, Reece, & Sanders, 2008) | Crosby and Twohig (2016), Levin et al., (2017) |

| Pornography-related self-efficacy | Pornography-Use Avoidance Self-Efficacy Scale (Kraus, Rosenberg, Martino, Nich, & Potenza, 2017) | Bőthe et al., (2021) |

| Self-regulation | Control of obsessive thoughts | Coleman et al., (2000) |

| Brief Self-Control Scale (Tangney, Baumeister, & Boone, 2004) | Efrati and Gola (2018) | |

| Psychological distress | Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation Outcome Measure (CORE-OM) (Evans et al., 2002) | Hall et al., (2020), Hallberg et al. (2019, 2020) |

| Symptom checklist-90 (L. R. Derogatis & Fitzpatrick, 2004) | Kjellgren (2018) | |

| Mental Health Index (Ware, 1993); lower scores mean higher psychological distress | Efrati and Gola (2018) | |

| Brief symptom inventory (L. Derogatis & Spencer, 1993) | Klontz et al., (2005) | |

| Treatment satisfaction | Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ-8) (Attkisson & Zwick, 1982) |

Hallberg et al. (2017, 2019, 2020) |

| Treatment satisfaction scale-2 (Clinton, Björck, Sohlberg, & Norring, 2004) | Kjellgren (2018) | |

| Perceived recovery | Retrospective self-report ratings of percent recovered prior to starting the intervention to the ratings of percent recovered to date | Hardy et al., (2010) |

| Quality of life | Behavioral and Symptom Identification Scale (BASIS-32) (Eisen & Cahill, 2000) |

Hartman et al. (2012), Orzack et al. (2006) |

| Quality of Life Scale (Burckhardt, Woods, Schultz, & Ziebarth, 1989) | Crosby and Twohig (2016), Levin et al., (2017), Twohig and Crosby (2010) | |

| Paraphilic disorders | Severity Self-Rating Measures for Paraphilic Disorders | Hallberg et al., (2020) |

| Problematic use of computers | Orzack Time Intensity Survey (OTIS) (Orzack et al., 2006) | Orzack et al., (2006) |

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | Obsessive-compulsive inventory (first or revised version) (OCI) (Foa, Kozak, Salkovskis, Coles, & Amir, 1998; Foa et al., 2002) | Holas et al. (2020), Twohig and Crosby (2010) |

| Brief symptom inventory (L. Derogatis & Spencer, 1993), obsessive-compulsive subscale | Klontz et al., (2005) | |

| Depression | Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS-S) (Svanborg & Åsberg, 2001) | Hallberg et al. (2019, 2020) |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Depression subscale (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983) | Holas et al., (2020) | |

| Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck, Guth, Steer, & Ball, 1997) | Orzack et al., (2006) | |

| Brief Symptom Inventory (L. Derogatis & Spencer, 1993), depression subscale | Klontz et al., (2005) | |

| Anxiety | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Anxiety subscale (Zigmond & Snaith, 1983) | Holas et al., (2020) |

| Weekly self-monitoring of subjective anxiety level | Gola and Potenza (2016) | |

| Brief Symptom Inventory (L. Derogatis & Spencer, 1993), anxiety subscale | Klontz et al., (2005) | |

| Substance use | Timeline follow back (Sobell & Sobell, 1992) | Hartman et al., (2012) |

| Psychological flexibility | Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (Hayes et al., 2004; Bond et al., 2011) | Levin et al., (2017), Twohig and Crosby (2010) |

| Moral incongruency | Perceived addiction and moral incongruence regarding pornography use (Grubbs et al., 2019) |

Bőthe et al., (2021) |

| Shame | Internalized shame scale (Cook & Coccimiglio, 2001) | Wilson and Fischer (2018) |

Psychotherapy with focus on CBT

The data of six studies on psychotherapy with focus on CBT (Table 5) could be integrated within the quantitative synthesis. All but one studies report significant effects of treatment on symptom severity in the treatment group (Bőthe et al., 2021; Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Hallberg et al., 2019; Wilson & Fischer, 2018, 2020). These effects remained stable all studies with a three months follow-up assessment (Hallberg et al., 2019, 2020; Wilson & Fischer, 2018) and in the study with a six months follow-up assessment (Hallberg et al., 2019). Three studies included a waitlist control group that showed only minor effects (Bőthe et al., 2021; Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Hallberg et al., 2019). Group by time interactions were identified in these studies with more pronounced changes in symptom severity in the treatment group compared to the control group. In three studies treatment effects on behavior enactment was reported (Bőthe et al., 2021; Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Holas et al., 2020). Effects were less stable than those for symptom severity. Effects could be identified for frequency and amount of behavior enactment within the treatment group in two studies (Bőthe et al., 2021; Crosby & Twohig, 2016). Holas et al. (2020) did not find significant effects for amount of time spend with pornography and Bőthe et al. (2021) did not find effects on duration of use. The waitlist control groups did not show any changes in behavior enactment (Bőthe et al., 2021; Crosby & Twohig, 2016).

Table 5.

Quantitative synthesis of studies on psychotherapy with focus on cognitive behavioral therapy sorted by risk of bias (RoB) assessment

| BL vs. post | BL vs. 3FU | BL vs. 6FU | ||||

| Reference | RoB | Scale | TG | CG | TG | TG |

| Symptom severity | ||||||

| Bőthe et al. (2021) a | 61 | PPCS | 1.19 [0.36, 2.03] | -0.02 [-0.35, 0.30] | ||

| Hallberg et al. (2019) b | 46 | HD:CAS | 0.82 [0.53, 1.11] | 0.06 [-0.30, 0.44] | 0.78 [0.42, 1.15] | 0.64 [0.20, 1.08] |

| Hallberg et al. (2019) b | 46 | SCS | 0.60 [0.30, 0.89] | 0.00 [-0.38, 0.39] | 0.89 [0.52, 1.26] | 0.93 [0.48, 1.38] |

| Wilson and Fischer (2018) | 36 | HBI-19 | 2.60 [1.88, 3.33] | 2.00 [1.35, 2.66] | ||

| Crosby and Twohig (2016) | 35 | SCS | 1.25 [0.44, 2.06] | 0.15 [-0.62, 0.92] | ||

| Hallberg et al. (2020) | 34 | HBI-19 | 1.53 [0.99, 2.06] | 1.43 [0.86, 2.00] | ||

| Hallberg et al. (2020) | 34 | HD:CAS | 4.89 [3.95, 5.82] | 5.12 [4.08, 6.16] | ||

| Hallberg et al. (2020) | 34 | SCS | 6.02 [4.92, 7.12] | 6.66 [5.37, 7.95] | ||

| Holas et al. (2020) | 25 | BPS | 0.51 [-0.40, 1.40] | |||

| Behavior enactment | ||||||

| Bőthe et al. (2021) a | 61 | freq | 1.45 [0.59, 2.32] | -0.07 [-0.40, 0.25] | ||

| Bőthe et al. (2021) a | 61 | dur | 0.03 [-0.73, 0.80] | 0.05 [-0.28, 0.37] | ||

| Crosby and Twohig (2016) | 35 | am | 1.72 [0.85, 2.58] | 0.29 [-0.49, 1.06] | ||

| Holas et al. (2020) | 25 | amc | 0.89 [-3.30, 2.07] | |||

Note. Cohen's d and 95% confidence intervals are reported. References are sorted from lowest to highest risk of bias with higher sum scores indicating lower risk of bias. Risk of bias evaluation is based on CONSORT criteria. asample consisting of individuals who self-identified as having PPU/were willing to participate in an online treatment for PPU, bpooled sample (treatment group and post waitlist treatment group), camount of time spent using pornography. 3/6FU = 3/6 months follow-up assessment, am = amount of behavior enactment, BL = baseline assessment, BPS = Brief Pornography Screener (Kraus et al., 2020), CG = control group, dur = duration of session when enacting in behavior, freq = frequency of behavior enactment, HBI-19 = Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (Reid et al., 2011), HD:CAS = Hypersexual Disorder: Current Assessment Scale (American Psychiatric Association's DSM-5 workgroup on sexual and gender identity disorders), HDSI = Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (Kafka, 2013), post = post treatment assessment, PPCS = Problematic Pornography Consumption Scale (Bőthe et al., 2018), RoB = risk of bias assessment, SCS = Sexual Compulsivity Scale (Kalichman & Rompa, 1995), TG = treatment group.

Other psychotherapy approaches

Data of four studies on other psychotherapy approaches could be integrated within the quantitative synthesis (Table 6). In two studies significant effects on symptom severity in the treatment group could be identified at post-treatment but only for men, not for women (Klontz et al., 2005; Wilson & Fischer, 2018). After three or six months, all treatment studies showed significant effects on symptom severity in treatment groups in both men and women.

Table 6.

Quantitative synthesis of studies on other psychotherapy approaches sorted by risk of bias (RoB) assessment

| BL vs. post | BL vs. 3FU | BL vs. 6FU | |||

| Reference | RoB | Scale | TG | TG | TG |

| Symptom severity | |||||

| Wilson and Fischer (2018) | 36 | HBI-19 | 2.59 [1.87, 3.31] | 2.79 [2.04, 3.54] | |

| Hartman et al. (2012) a | 29 | CSBI | 1.57 [0.88, 2.26] | ||

| Hartman et al. (2012) b | 29 | CSBI | 1.19 [0.69, 1.69] | ||

| Kjellgren (2018) | 27 | SAST | 0.42 [-0.11, 0.95] | ||

| Klontz et al. (2005) c | 20 | GSBI | 0.58 [0.05, 1.12] | 0.61 [0.07, 1.14] | |

| Klontz et al. (2005) d | 20 | GSBI | 0.51 [-0.55, 1.58] | 1.85 [0.60, 3.10] | |

Note. Cohen's d and 95% confidence intervals are reported. References are sorted from lowest to highest risk of bias with higher sum scores indicating lower risk of bias. Risk of bias evaluation is based on CONSORT criteria. aindividuals without substance use disorder; bindividuals with substance use disorder; cresults for males; dresults for females. 3/6FU = 3/6 months follow-up assessment, BL = baseline assessment, CSBI = Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory (Coleman et al., 2001), GSBI = Garos Sexual Behavior Inventory (Garos & Stock, 1998), HBI-19 = Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (Reid et al., 2011), post = post treatment assessment, RoB = risk of bias assessment, SAST = Sexual Addiction Screening Test (Carnes et al., 2010), TG = treatment group.

Pharmacological treatment

Data of two studies on pharmacological treatment approaches could be integrated within the quantitative synthesis (Table 7). Both studies show significant effects on symptom severity in the treatment group. However, Wainberg et al. (2006) also found effects on symptom severity in the placebo control group, no group differences between treatment and control group, and no effects on behavior enactment.

Table 7.

Quantitative synthesis of studies on pharmacological treatment sorted by risk of bias (RoB) assessment

| BL vs. post | BL vs. 1FU | ||||

| Reference | RoB | Scale | TG | CG | TG |

| Symptom severity | |||||

| Wainberg et al. (2006) | 48 | YBOCS-CSB | 1.73 [0.83, 2.63] | 1.32 [0.53, 2.11] | |

| Wainberg et al. (2006) | 48 | CSBI | 1.30 [0.45, 2.14] | 1.15 [0.37, 1.92] | |

| Savard et al. (2020) | 36 | HD:CAS | 1.32 [0.64, 2.01] | 0.56 [-0.08, 1.19] | |

| Savard et al. (2020) | 36 | HBI-19 | 1.98 [1.22, 2.74] | 1.36 [0.67, 2.05] | |

| Savard et al. (2020) | 36 | SCS | 1.83 [1.09, 2.56] | 0.98 [0.32, 1.64] | |

| Behavior enactment | |||||

| Wainberg et al. (2006) | 36 | ama | 0.72 [-0.7, 1.51] | 0.07 [-0.64, 0.79] | |

Note. Cohen's d and 95% confidence intervals are reported. References are sorted from lowest to highest risk of bias with higher sum scores indicating lower risk of bias. Risk of bias evaluation is based on CONSORT criteria. aamount of pornography use. 1FU = one month follow-up assessment, am = amount of behavior enactment, BL = baseline assessment, CG = control group, CSBI = Compulsive Sexual Behavior Inventory (Coleman et al., 2001), HBI-19 = Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (Reid et al., 2011), HD:CAS = Hypersexual Disorder: Current Assessment Scale (American Psychiatric Association's DSM-5 workgroup on sexual and gender identity disorders), post = post treatment assessment, RoB = risk of bias assessment, SCS = Sexual Compulsivity Scale (Kalichman & Rompa, 1995), TG = treatment group, YBOCS-CSB = Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale – Compulsive sexual behavior (Wainberg et al., 2006).

Risk of bias assessment

Four studies could be identified as randomized-controlled trials (Bőthe et al., 2021; Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Hallberg et al., 2019; Wainberg et al., 2006) with a waitlist or placebo control group. One further randomized study compared CBT with art therapy (Wilson & Fischer, 2018). The quality of most studies was low or very low. Detailed results of risk of bias assessment are presented in Table 8. Only four studies could reach a score higher than 50 percent of all possible points. However, even in these studies some risks of bias need to be mentioned. Although the design of the study is reasonable, the feasibility study by Bőthe et al. (2021) only included individuals interested in participating in a treatment study for PPU and report high drop-out rates. The study by Wainberg et al. (2006) focused on gay and bisexual men and the cut-off score as inclusion criteria is unclear. Finally, Sniewski et al. (2020) used a reasonable research design, but the sample size was very small. Only one study was pre-registered (see pre-registration: Bőthe et al., 2021; Bőthe, Baumgartner, Schaub, Demetrovics, & Orosz, 2020).

Table 8.

Risk of Bias (RoB) assessment with CONSORT items

| Randomized controlled trial | Non-randomized controlled trial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CONSORT item | Bőthe et al. (2021) | Wainberg et al. (2006) | Hallberg et al. (2019) | Crosby and Twohig (2016) | Sniewski et al. (2020) | Wilson and Fischer (2018) | Savard et al. (2020) | Hallberg et al. (2020) | Hallberg et al. (2017) | Raymond et al. (2010) | Hartman et al. (2012) | Twohig and Crosby (2010) | Kjellgren (2018) | Holas et al. (2021) | Levin et al. (2017) | Hardy et al. (2010) | Gola and Potenza (2016) | Coleman et al. (2000) | Kafka and Hennen (2000) | Klontz et al. (2005) | Efrati and Gola (2018) | Orzack et al. (2006) | Hall et al. (2020) | Wan et al. (2000) | |

| Title and abstract | 1a | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1b | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Background and objectives | 2a | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 2b | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Trial design | 3a | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Participants | 4a | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 4b | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | |

| Interventions | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Outcomes | 6a | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 6b | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sample size | 7a | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 7b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Sequence generation | 8a | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8b | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Allocation concealment mechanism | 9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Implementation | 10 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Blinding | 11a | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11b | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Statistical methods | 12a | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12b | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Participant flow | 13a | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 13b | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| Recruitment | 14a | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 14b | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Baseline data | 15 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Numbers analysed | 16 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Outcomes and estimation | 17a | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 17b | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Ancillary analyses | 18 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Harms | 19 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Limitations | 20 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Generalisability | 21 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Interpretation | 22 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Registration | 23 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Protocol | 24 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Funding | 25 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| RoB Sum | 61 | 48 | 46 | 35 | 43 | 36 | 36 | 34 | 30 | 30 | 29 | 28 | 27 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 23 | 23 | 20 | 18 | 18 | 15 | 13 | |

Note. Bold references have been included in the quantitative synthesis. We differentiate between randomized controlled trials and non-randomized controlled trials. Within these categories, references are sorted from lowest to highest risk of bias with higher sum scores indicating lower risk of bias. A detailed description of the CONSORT items can be retrieved from Moher et al. (2012). If an item was completely reported, it was rated with a score of ‘2’, if some information was missing, it was rated with ‘1’, if no information was given at all, it was rated with a score of ‘0’. This was also the case if the item was probably not applicable to the design. By this procedure studies which did not report a certain detail of the study were equally rated as studies which neglected this detail within the study design. 1a = Randomized trial in abstract, 1b = Structured abstract, 2a = Background/rationale, 2b = Objectives/hypotheses, 3a = Description, 3b = Changes, 4a = Eligibility criteria, 4b = Settings/locations data collection, 5 = For each group, 6a = Primary/secondary outcomes, 6b = Changes, 7a = How determined, 7b = Interim analyses/stopping guidelines, 8a = Method, 8b = Type of randomization, 9 = Mechanism, 10 = Who, 11a = Who blinded, 11b = Similarity of interventions, 12a = Statistical methods, 12b = Methods for additional analyses, 13a = Numbers of participants at each stage, 13b = Losses, exclusions, reasons, 14a = Dates defining the periods, 14b = Why the trial ended or was stopped, 15 = Table with characteristics, 16 = Number of participants, 17a = For each primary and secondary outcome, 17b = For binary outcomes, 18 = Results of any other analyses performed, 19 = All important harms or unintended effects, 20 = Trial limitations, 21 = Generalizability, 22 = Consistent with results, balanced, considering other relevant evidence, 23 = Registration number and name of trial registry, 24 = Where accessible, 25 = Sources of funding, role of funders, RoB = risk of bias assessment.

Discussion and conclusions

This systematic review of studies on treatments for CSBD and PPU shows that individuals treated in general experience positive effects from treatment such as reductions in symptom severity of CSBD/PPU. However, the high variance in assessment tools for symptom severity and criteria for diagnoses as well as the high heterogeneity in treatments make it difficult to attribute significant treatment effects to specific treatment approaches. In addition, the quality of studies with regard to risk of bias leaves room for improvement for future studies. Accordingly, strong conclusions should be drawn cautiously.

Since the systematic review by Dhuffar and Griffiths (2015) the literature base of case-control, pre-post interventive, and case series designs, as well as correlational designs with measures of change has been increased from six to 24 studies. Four randomized controlled studies could be identified. Treatment approaches differed considerably from various widely used CBT components (e.g. psychoeducation, training on self-regulation, cognitive restructuring), over newer approaches from the third wave of CBT (e.g. mindfulness, ACT), to alternative therapy approaches (art therapy, experiential therapy, 12 steps program), and pharmacological treatments (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, serotonin antagonist and reuptake inhibitors, psychostimulants). Overall, receiving treatment seems to improve symptoms of PPU and CSBD, indicated by studies in which the treatment group showed reductions in symptom severity that were not shown by individuals in the waitlist-control group (Bőthe et al., 2021; Crosby & Twohig, 2016; Hallberg et al., 2019) and the overall trend of significant improvements in symptom severity and behavior enactment from baseline to post treatment measures. Six of eight studies (all of which were psychotherapy studies) reported improvements in level of depression or quality of life. Two studies did not find any changes in quality of life. These results indicate that the treatments also have positive effects on general well-being and comorbid disorders. There is considerable evidence for the efficacy of approaches that include CBT. However, the study by Wainberg et al. (2006) in which individuals in the placebo control group showed similar reductions in symptom severity as compared to the group treated with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, indicates that the effect of taking part in a clinical trial may be higher than the specific effect of the treatment itself.

Observed studies focused on changes in symptom severity, behavior enactment as well as more broader measures of quality of life, and psychological distress including symptoms of other mental disorders. Less focus was put on core processes involved in the development and maintenance of CSBD and PPU such as cue-reactivity and craving. Only one study reported significant reductions in craving experienced by individuals in the treatment group as compared to the control group (Bőthe et al., 2021). Evidence on how single interventions effect specific core processes of CSBD and PPU may be informative for the development of specific treatments and prevention strategies. In this context the heterogeneity of individuals presenting symptoms of CSBD should be considered. While some mechanisms may be similar across behaviors, it can also be assumed that there are specificities in mechanisms, although detailed evidence is warranted (Antons & Brand, 2021).