Dear Editor,

Children, and young people (CYP) have a very low risk of severe or fatal COVID-19, especially when compared to adults.1 The recent UK seroprevalence study published in the Journal of Infection, reported that, by September 2022, 86.7% of children aged 1-17 years had been exposed to SARS-CoV-2, based on SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid (N) protein, mainly after the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant wave.2 The large number of Omicron infections reported in children, who were mainly unvaccinated at the time, raised concerns about increased hospitalisations and deaths in CYP.

In England, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) has been conducting COVID-19 surveillance in CYP since the start of the pandemic. We previously reported fatalities within 100 days of a positive SARS-CoV-2 test in CYP aged <20 years until the end of December 2021, which included the Wild-Type, Alpha and Delta variant waves in England.3 Detailed follow-up identified 185 deaths, of which 81 (43.8%) were due to COVID-19, with 91% of deaths occurring within 30 days of testing, mainly in CYP with severe and/or life-limiting underlying conditions.3 We have now extended our previous analysis to explore cases and deaths in CYP during the first Omicron (BA.1/BA.2) variant wave in England, where we have found very low infection fatality rates (IFR) despite higher numbers of infections.

Our surveillance methodology has been reported previously.3 Confirmed COVID-19 cases in CYP aged <20 years during January-March 2022 were linked to electronic vaccination records, Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and Personal Demographic Service (PDS) to identify fatalities within 30 days of testing and additional clinical information. We used multiple data sources to ascertain cause of death, including surveillance questionnaires sent to general practitioners, hospital discharge summaries, post-mortem reports, and death registration records. Any sudden/unexpected deaths where no other cause was identified was attributed to COVID-19. Age-specific IFR were calculated using estimated, rather than confirmed, national SARS-CoV-2 infections from PHE-Cambridge real-time modelling,4 as confirmed infections underestimated infection rates by up to four-fold.3 Published Office of National Statistics (ONS) mid-year population estimates,5 and all-cause deaths,6 were used to calculate mortality rates.

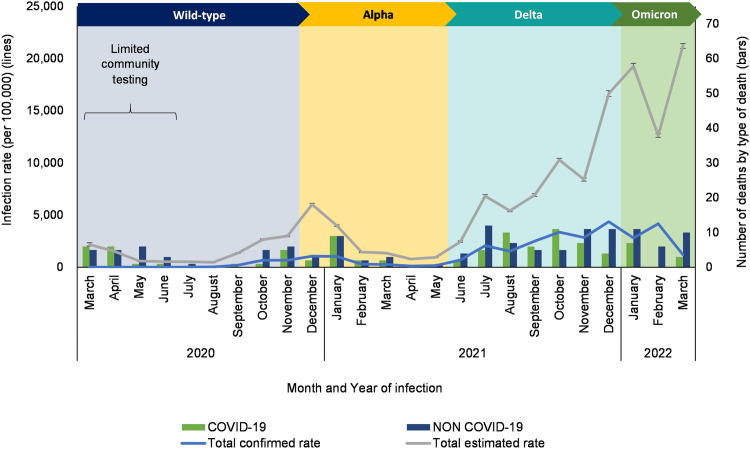

During January-March 2022, there were 879,944 confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections and 46 deaths within 30 days of a positive test, including 11 due to COVID-19 (Fig. 1 ). All followed primary SARS-CoV-2 infection, seven (64%) were male, six (55%) were of white ethnicity and seven (64%) had underlying comorbidities, including four with severe neurodisabilities (Supplement 1). Ten were hospitalised, with three requiring intensive care, while one case was diagnosed post-mortem. The median interval between testing and death was one (IQR 0-7) day. Of the eight CYP who were ≥12-years and eligible for vaccination, including six with underlying conditions, five had received two doses, one had one dose and two were unvaccinated.

Fig 1.

COVID-19 infection rates by age group and number of deaths by cause of death in CYP <20 years (predominant circulating variant shown by coloured chevrons).

There were 7,077,682 estimated infections in <20-year-olds (IFR, 0.2/100,000 [11/7,077,682] vs 0.7/100,000 [81/11,629,407] during March 2020 to December 2021): there were no fatalities in <1-year-olds (0.0 vs 1.7/100,000), two in 1-4-year-olds (0.2 vs 0.3/100,000), one in 5-11-year-olds (0.1 vs 0.3/100,000), two in 12-15-year-olds (0.1 vs 0.9/100,000) and six in 16-19-year-olds (0.2 vs 1.5/100,000).3 COVID-19 contributed to 1.1% (11/1,003) of deaths in <20-year-olds during January-March 2022, compared to 1.2% during March 2020 to December 2021.3 IFR during the Omicron wave was lower than Wild-Type (1.0/100,000; 21/2,062,780), Alpha (0.8/ 100,000; 15/1,980,140) and Delta (0.6/100,000; 45/7,586,488) waves.3

Despite very large infections during the Omicron wave compared to previous waves, there were 11 COVID-19 deaths in CYP in England, equivalent to 3.7 monthly fatalities, which was no different to the 81 deaths during the previous 22 months.3 Consequently, IFR during the Omicron wave were substantially lower than during all previous SARS-CoV-2 infection waves.3 Most fatalities involved CYP with severe comorbidities, especially neurodisabilities, similar to previous variant waves.3 Some deaths occurred despite vaccination against COVID-19. In England, we have previously reported less severe disease across all age groups with Omicron compared to Delta, in terms of hospital attendance, hospitalizations and death,7 which is consistent with a recent US study.8 In CYP, there were too few fatalities to assess differences between the two variants.7 , 8 One study from Qatar specifically focussed on CYP aged <18-years and found that primary infection with Omicron was associated with an 88% (95% CI, 82-93%) lower odds of moderate or severe/critical disease compared to Delta, with severe Omicron infections disproportionately affecting CYP with underlying comorbidities (aOR 3.16; 95% CI 1.11-9.00).9 In the US, too, the risk of severe disease was significantly lower with Omicron than Delta in under 5-year-olds.10 The lower risk of severe disease and fatalities is reassuring given the higher numbers of childhood hospitalisations during the Omicron wave in England7 and elsewhere.11 Potential reasons for lower severity of Omicron infections include a predilection for upper rather than lower airway infection as well as protection from prior infection and vaccination.12

In conclusion, we estimate the risk of death due to COVID-19 to be two in a million Omicron infections in CYP, being substantially lower than during the preceding waves. With increasing immunity from prior infection and vaccination, IFR is likely to drop further. Most COVID-19 fatalities occurred in CYP with severe/life-limiting comorbidities. This has important policy implications for COVID-19 vaccination and booster recommendations for CYP.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Acknowledgments

Funding

None.

Acknowledgments

We thank Natalie Mensah and Rashmi Malkani for case follow-up and administrative support. We thank all the general practitioners, hospital clinicians, healthcare professionals, coroners, and administrative staff within the NHS and Coroners’ offices for completing questionnaires and providing additional information where needed. We also thank the UKHSA COVID-19 Epidemiology Cell for monitoring fatalities in CYP with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2023.01.032.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Ludvigsson JF. Systematic review of COVID-19 in children shows milder cases and a better prognosis than adults. Acta Paediatr. 2020;109(6):1088–1095. doi: 10.1111/apa.15270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oeser C, Whitaker H, Borrow R, et al. Following the Omicron wave, the majority of children in England have evidence of previous COVID infection. J Infect. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2022.12.012. , S0163-4453(22)00701-0 (Online ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertran M, Amin-Chowdhury Z, Davies HG, et al. COVID-19 deaths in children and young people in England, March 2020 to December 2021: An active prospective national surveillance study. PLOS Med. 2022;19(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1004118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Birrell P, Blake J, van Leeuwen E, Gent N, De Angelis D. Real-time nowcasting and forecasting of COVID-19 dynamics in England: the first wave. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2021;376(1829) doi: 10.1098/rstb.2020.0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of National Statistics. Estimates of the population for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. [Mid-2020]. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/populationestimatesforukenglandandwalesscotlandandnorthernireland (accessed 18 January 2023).

- 6.Office for National Statistics. Deaths registered weekly in England and Wales, provisional (November 2022). Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/datasets/weeklyprovisionalfiguresondeathsregisteredinenglandandwales (accessed 18 January 2023).

- 7.Nyberg T, Ferguson NM, Nash SG, et al. Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet. 2022;399(10332):1303–1312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)00462-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewnard JA, Hong VX, Patel MM, Kahn R, Lipsitch M, Tartof SY. Clinical outcomes associated with SARS-CoV-2 Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant and BA.1/BA.1.1 or BA.2 subvariant infection in Southern California. Nat Med. 2022;28(9):1933–1943. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01887-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butt AA, Dargham SR, Loka S, et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 disease severity in children infected with the Omicron variant. Clinic Infect Dis. 2022;75(1):e361–e3e7. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciac275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang L, Berger NA, Kaelber DC, Davis PB, Volkow ND, Xu R. Incidence rates and clinical outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection with the omicron and delta variants in children younger than 5 years in the US. JAMA Pediatrics. 2022;176(8):811–813. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2022.0945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bahl A, Mielke N, Johnson S, Desai A, Qu L. Severe COVID-19 outcomes in pediatrics: an observational cohort analysis comparing Alpha, Delta, and Omicron variants. Lancet Reg Health – Americas. 2023;18 doi: 10.1016/j.lana.2022.100405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sigal A. Milder disease with Omicron: is it the virus or the pre-existing immunity? Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22(2):69–71. doi: 10.1038/s41577-022-00678-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.