To the Editor:

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) vaccines confer great protection against symptomatic and severe coronavirus disease (COVID-19) in healthy adults, but little is known for specialized patient populations despite billions of doses given worldwide. Asthma is one of the most common chronic respiratory diseases and affects approximately 25 million people in the United States alone. There are currently six U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved biologic therapies for the treatment of asthma, with some that target cytokines critical for asthma pathogenesis, but inhibition of these cytokines may also negatively affect B cell to plasma cell differentiation, somatic hypermutation in the germinal centers, and long-lived plasma cell generation and maintenance potentially through eosinophil depletion (1–3). Despite animal studies showing decreased vaccine-induced humoral immunity without these cytokines (4, 5), there is a paucity of literature available in this patient population following SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.

Two prior studies have evaluated short-term vaccine response in patients treated with biologic therapies approved for asthma. The first study enrolled patients with moderate or severe asthma who were treated with benralizumab or placebo and given the tetravalent influenza vaccine. They found a similar antibody response 4 weeks after vaccination in the treated group compared with placebo (6). Another study evaluated patients with moderate or severe atopic dermatitis treated with dupilumab or placebo and found that both groups had similar antibody responses 4 weeks after meningococcal or tetanus vaccination (7). Neither of these studies evaluated the durability of the antibody response beyond 4 weeks. In addition, since neither study compared responses to healthy adults, it is not clear if patients with asthma or atopic dermatitis indeed have similar vaccine responses to healthy adults that made up the majority of patients in the original SARS-CoV-2 vaccine trials. Therefore, it is unclear if patients with severe asthma and atopic dermatitis on biologic therapies have an adequate and durable humoral immune response after vaccination to SARS-CoV-2.

To address these questions, we conducted a prospective observational trial from February 2021 to September 2021 with adults who had severe asthma or atopic dermatitis treated with benralizumab (IL-5 receptor antagonist), mepolizumab (IL-5 antagonist), or dupilumab (IL-4 receptor α antagonist). Patients had received one of the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines, Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna. Blood samples were taken from 41 patients on dupilumab (57% treated for severe asthma, 37% for atopic dermatitis, 3% for both severe asthma and atopic dermatitis, and 3% for hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome), 23 patients on benralizumab, and 9 patients on mepolizumab for a total of 73 patients in addition to 39 healthy adults. After excluding patients with a prior history of COVID-19 or significant immunosuppression, the final cohort included 107 samples from 48 patients (average age of 53 yr, 60% women; 30 patients on dupilumab, 12 patients on benralizumab, and 6 patients on mepolizumab) in addition to 107 samples from 36 healthy control subjects (average age of 36 yr, 72% women). Samples were analyzed for specific SARS-CoV-2 antigen reactivities (wild-type and Delta variant receptor-binding domain [RBD], S1, S2, N-terminus binding domain, nucleocapsid, and ORF3a) with a high-throughput multiplex Luminex assay (8).

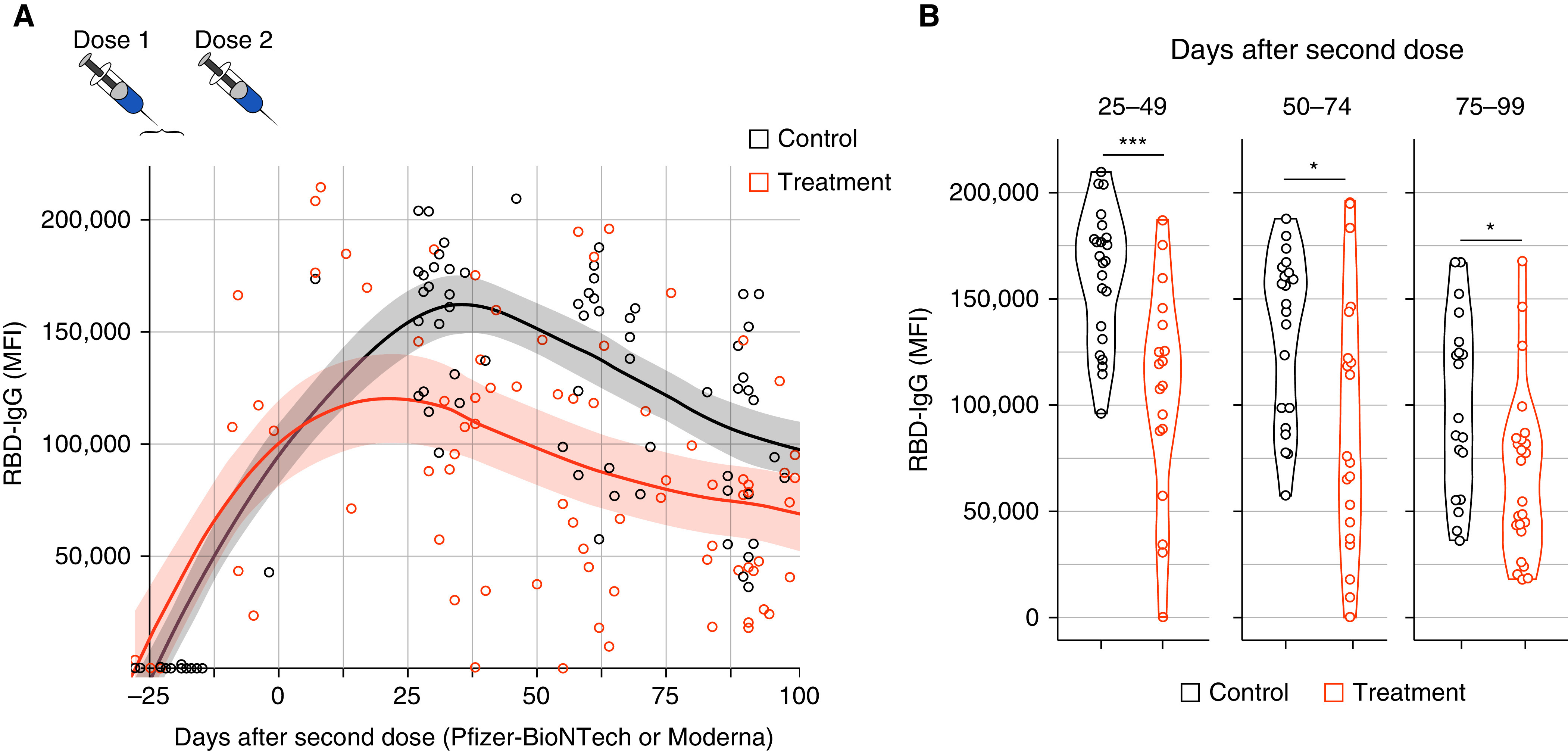

Patients on biologic therapies had lower IgG levels to the wild-type SARS-CoV-2 RBD compared with healthy adults (average median fluorescence intensity of 105,950 and 160,584, respectively; P = 0.0001) (Figure 1) on Days 25–49 after the second vaccine dose. At the later time point, antibody levels for patients on biologic therapies remained significantly lower compared with healthy adults (average median fluorescence intensity of 67,535 and 100,519, respectively; P = 0.012), at approximately 67% of the healthy adult’s antibody levels. Similar results were seen for other SARS-CoV-2 antigens, including Delta variant RBD and spike protein S1.

Figure 1.

(A) Time after dose 2 of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) mRNA vaccination and IgG titer to wild-type SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain (RBD). Shaded area indicates 95% confidence interval. Treatment group includes all patients on benralizumab, dupilumab, and mepolizumab. (B) IgG to wild-type SARS-CoV-2 RBD on Days 25–49, 50–74, and 75–99 after dose 2 of the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. Treatment group includes all patients on benralizumab, dupilumab, and mepolizumab; *P < 0.012 and ***P = 0.0001. MFI = median fluorescence intensity.

These data demonstrate that patients with severe asthma or atopic dermatitis on biologic therapies have lower antibody levels after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination compared with healthy adults, and that these differences persist for at least 3 months. The question remains whether the lower antibody levels in our specialized patient population are an effect of the biologic therapies, or if it is a combination of confounding factors such as higher average age in the treatment group compared with control subjects, more comorbid conditions, and a greater number of medications used in our treatment group compared with healthy control subjects. Although patients on high-dose oral corticosteroids were excluded (defined as a daily dose of >10 mg of oral prednisone or other corticosteroid equivalent), we raise the issue of whether the frequent use of high-dose inhaled corticosteroids that are routinely taken in patients with severe asthma (9) may have also confounded these results. As there is evidence that lower vaccine-specific titers afford less protection against COVID-19 (10), clinicians and patients should consider earlier or more frequent booster vaccinations in these patients who may unknowingly remain at high risk for severe disease.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the trial participants, healthcare providers, and research staff for their important contributions; Fabliha Anam and John L. Daiss, Ph.D., for help with developing and performing experiments; Ian Hentenaar for help processing samples; Merin Kuruvilla, M.D., Carmen Polito, M.D., Wendy Neveu, M.D., Ignacio Sanz, M.D., Colin Swenson, M.D., and Robert Swerlick, M.D., for help with patient recruitment; and Zhenxing Guo and Hao Wu, Ph.D., for help with statistical analysis.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: P01AI125180-01, P01A1078907, U54CA260563, R01AI121252, 1U01AI141993, and 5T32HL116271-09.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202111-2496LE on February 18, 2022

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Reinhardt RL, Liang H-E, Locksley RM. Cytokine-secreting follicular T cells shape the antibody repertoire. Nat Immunol . 2009;10:385–393. doi: 10.1038/ni.1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Takatsu K, Kouro T, Nagai Y. Interleukin 5 in the link between the innate and acquired immune response. Adv Immunol . 2009;101:191–236. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)01006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chu VT, Fröhlich A, Steinhauser G, Scheel T, Roch T, Fillatreau S, et al. Eosinophils are required for the maintenance of plasma cells in the bone marrow. Nat Immunol . 2011;12:151–159. doi: 10.1038/ni.1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Strestik BD, Olbrich ARM, Hasenkrug KJ, Dittmer U. The role of IL-5, IL-6 and IL-10 in primary and vaccine-primed immune responses to infection with Friend retrovirus (Murine leukaemia virus) J Gen Virol . 2001;82:1349–1354. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-82-6-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kühn R, Rajewsky K, Müller W. Generation and analysis of interleukin-4 deficient mice. Science . 1991;254:707–710. doi: 10.1126/science.1948049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zeitlin PL, Leong M, Cole J, Mallory RM, Shih VH, Olsson RF, et al. ALIZE study investigators Benralizumab does not impair antibody response to seasonal influenza vaccination in adolescent and young adult patients with moderate to severe asthma: results from the phase IIIb ALIZE trial. J Asthma Allergy . 2018;11:181–192. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S172338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blauvelt A, Simpson EL, Tyring SK, Purcell LA, Shumel B, Petro CD, et al. Dupilumab does not affect correlates of vaccine-induced immunity: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol . 2019;80:158–167.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Haddad NS, Nguyen DC, Kuruvilla ME, Morrison-Porter A, Anam F, Cashman KS, et al. One-stop serum assay identifies COVID-19 disease severity and vaccination responses. Immunohorizons . 2021;5:322–335. doi: 10.4049/immunohorizons.2100011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hanania NA, Sockrider M, Castro M, Holbrook JT, Tonascia J, Wise R, et al. American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Centers Immune response to influenza vaccination in children and adults with asthma: effect of corticosteroid therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2004;113:717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.12.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Earle KA, Ambrosino DM, Fiore-Gartland A, Goldblatt D, Gilbert PB, Siber GR, et al. Evidence for antibody as a protective correlate for COVID-19 vaccines. Vaccine . 2021;39:4423–4428. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]