Abstract

Introduction

KRAS, BRAF, and DNA mismatch repair (MMR) mutations aid clinical decision-making for colorectal cancer (CRC) patients. To ensure accurate predictions, the prognostic utilities of these biomarkers and their combinations must be individualized for patients with various TNM stages.

Methods

Here, we retrospectively analyzed the clinicopathological features of 904 Korean CRC patients who underwent CRC surgery in three teaching hospitals from 2011 to 2013; we also assessed the prognostic utilities of KRAS, BRAF, and MMR mutations in these patients.

Results

The overall frequencies of KRAS and BRAF mutations were 35.8% and 3.2%, respectively. Sixty-nine patients (7.6%) lacking expression of ≥1 MMR protein were considered MMR protein deficient (MMR-D); the remaining patients were considered MMR protein intact. KRAS mutations constituted an independent risk factor for shorter overall survival (OS) in TNM stage I–IV and stage III patients. BRAF mutations were associated with shorter OS in TNM stage I–IV patients. MMR-D status was strongly positive prognostic in TNM stage I–II patients.

Discussion/Conclusion

To our knowledge, this is the first multicenter study to explore the prognostic utilities of KRAS, BRAF, and MMR statuses in Korean CRC patients. Various combinations of KRAS, BRAF, and DNA MMR mutations serve as genetic signatures that affect tumor behavior; they are prognostic in CRC patients.

Keywords: KRAS mutation, BRAF mutation, Mismatch repair status, Colorectal cancer

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death worldwide [1]. The American Institute for Cancer Research has reported that the CRC incidence in South Korea is the second highest globally [2]. Various molecular mechanisms are involved in the CRC pathogenesis, of which chromosomal instability (CIN) (75%) and microsatellite instability (MSI) (15%) play major role [3]. CIN affects critical genes such as APC, KRAS, PI3K, and TP53 [4]. MSI is caused by the inactivation of genes involved in the correction of nucleotide − base mismatches in DNA [5]. Loss of expression of mismatch repair (MMR) genes including MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 can be caused by spontaneous events or germinal mutations such as Lynch syndrome [6, 7].

In order to correlate cancer cell phenotype with clinical implication and guide specific targeted therapies, the CRC Subtyping Consortium made a single consensus, based on gene expression data, into 4 distinct groups, known as the consensus molecular subtypes (CMSs) [8]. CMS1, known as MSI-immune subtype, is characterized by high BRAF mutation, hypermethylation of CpG islands, an association with an impaired MMR system, and the infiltration of immunogenic lymphocytes in the tumor microenvironment (14%) [9]. The majority of CRC previously described as CIN was divided into 3 subtypes based on transcriptomic profiling. CMS2, known as canonical subtype, displayed epithelial signatures with prominent WNT and MYC signaling activation (37%) [10]. CMS3, known as metabolic subtype, has genomic features consistent with CIN but has fewer DNA somatic copy number alterations and more hypermutated/MSI than CMS2 and CMS4 (13%) [8]. CMS4, known as mesenchymal subtype, exhibits high transforming growth factor β (TGFβ), extremely low levels of hypermutation, MSS status, and very high somatic copy number alteration counts (23%) [11].

KRAS and BRAF mutations are associated with upregulation of the RAS/RAF/MAPK signaling pathway, which has a critical role in CRC development [12]. The mechanisms that underlie CIN include changes in chromosomal segregation and the DNA damage response (e.g., KRAS mutations) [13]. Both BRAF mutation and MMR statuses distinguish sporadic tumors from Lynch syndrome-related tumors [14]. Among MMR protein deficient (MMR-D) CRCs, 34–70% have BRAF mutations [15]. MMR-D and the CpG island methylator phenotype are closely associated [16]. Most MMR-D tumors develop through CpG island methylator phenotype-associated methylation of MLH1 [17]. Moreover, the presence of a BRAF mutation in an MLH1-deficient CRC patient suggests a sporadic tumor rather than a Lynch syndrome tumor [14].

However, the prognostic utilities of KRAS and BRAF mutations, as well as MMR status, in CRC patients with specific TNM stages remain unclear [18]. We performed a large retrospective study in such Korean patients and evaluated their clinicopathological features and prognoses according to TNM stage. In addition, we assessed the associations of KRAS mutations, BRAF mutations, and MMR status with each TNM stage.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Treatment

Clinical and pathological information was collected regarding 904 patients who underwent CRC surgery in three teaching hospitals (Seoul St. Mary's Hospital, Gangdong; Kyung Hee University Hospital, and Yeungnam University Hospital) from 2011 to 2013.

Inclusion criteria were complete data concerning tumor markers, survival, and stage. Cases without any one of tumor marker records about KRAS mutation, BRAF mutation, or MMR status were excluded. A total of 210 patients with incomplete tumor marker records were excluded. Fifteen patients with histologically confirmed Tis were also excluded from the study. Medical records and pathology reports were analyzed. Adjuvant chemotherapy was recommended to stage III or high-risk (with cancer-related obstructions or perforations; with poorly differentiated cancers; with lymphovascular/perineural invasion; or with MMR protein intact [MMR-I] status) stage II patients, based on the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines. FOLFOX (fluorouracil, leucovorin, and oxaliplatin), FOLFIRI (fluorouracil, leucovorin, and irinotecan), LF (leucovorin and fluorouracil), XELODA (capecitabine), and XELOX (capecitabine and oxaliplatin) systemic chemotherapies were prescribed according to each patient's clinical situation. Depending on KRAS status, target therapy was offered as an adjunct to systemic chemotherapy.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary's Hospital (approval number: KC17RCDI0781). This study has been designed to review medical records retrospectively. Medical records that can perceive identities are anonymized. No one other than the researcher could browse these medical records. Consents from patients were waived.

Analysis of KRAS, BRAF, and MMR Status

Tissue samples from tumors and normal colonic mucosae were obtained from all patients after resection. Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue samples were sectioned at a thickness of 10 μm. After deparaffinization, tissue samples were digested with proteinase K (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA, USA); KRAS exon 2 DNA was then isolated and amplified via polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the forward primer (5′-AAGGCCTGCTGAAAATGAC-3′) and reverse primer (5′-TGGTCCTGCACCAGTAATATG-3′). The PCR products were purified using QI-Aquick PCR Purification Kits (Qiagen) and sequenced on an ABI 3730 automated platform (Applied Biosystems Inc., Foster City, CA, USA). Similarly, exon 15 of BRAF was amplified via PCR using the forward primer (5′-AATGCTTGCTCTGATAGGAAAAT-3′) and reverse primer (5′-TAATCAGTGGAAAAATAGCCTC-3′).

MMR status was determined by the immunohistochemical (IHC) absence of proteins encoded by MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, or PMS2. IHC for MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2 was performed on FFPE tumor tissue block on a Ventana BenchMark Ultra device (Ventana Medical Systems, Arizona, USA). As a multicenter study was conducted, each result was confirmed by different pathologists. IHC for the detection of MMR proteins in CRC samples is a simple tool to determine MMR deficiency [19, 20, 21]. To minimize interobserver variation between different pathologists, reporting format from the Gastrointestinal Pathology Study Group of the Korean Society of Pathologists has been used [22]. Tumors that had lost at least one MMR protein microsatellite marker were considered MMR-D; the remaining tumors were considered MMR-I.

Statistical Analysis

The Mann-Whitney U test was employed for univariate analysis of continuous variables; the results are expressed as means ± standard deviations. The χ2 or Fisher's test was used for univariate analysis of categorical variables. Variables significant in univariate analyses were included in multivariate logistic regression analysis. Overall survival (OS) was determined using the Kaplan-Meier method. All statistical analyses were conducted using R, version 4.0.4 (www.r-project.org), based on a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Clinicopathological Features

The clinicopathological features of the 904 patients are summarized in Table 1. Three patients with both KRAS and BRAF mutations were excluded. Mutations in KRAS codons 12 and 13 were detected in 242 (26.8%) and 76 (8.4%) patients, respectively. Four patients (0.4%) had mutations in both KRAS codons 12 and 13.

Table 1.

Clinicopathological features of patients

| Clinicopathological features | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Patients, n | 904 |

| Age, median | 62.64±11.78 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 541 (59.85) |

| Female | 363 (40.15) |

| HTN | |

| No | 518 (57.30) |

| Yes | 386 (42.70) |

| DM | |

| No | 727 (80.42) |

| Yes | 177 (19.58) |

| Smoking | |

| No | 697 (77.10) |

| Yes | 207 (22.90) |

| Cancer family history | |

| No | 759 (83.96) |

| Yes | 145 (16.04) |

| Tumor location | |

| Cecum | 32 (3.54) |

| Ascending colon | 150 (16.59) |

| Transverse colon | 54 (5.97) |

| Lt. colon | 385 (42.59) |

| Rectum | 262 (28.98) |

| Multiple | 21 (2.32) |

| TNM stage | |

| I | 184 (20.35) |

| II | 271 (29.98) |

| III | 335 (37.06) |

| IV | 114 (12.61) |

| Mucinous type | |

| No | 874 (96.68) |

| Yes | 30 (3.32) |

| KRAS mutant | 324 (35.84) |

| BRAF mutant | 29 (3.21) |

| MMR-D | 69 (7.63) |

Univariate and Multivariate Analysis of KRAS, BRAF, and MMR Status

The clinicopathological features of patients, stratified according to KRAS, BRAF, and MMR statuses, are summarized in Tables 2, 3, 4. KRAS mutations were significantly associated with smoking, tumor location, and mucinous-type tumors. BRAF mutations and MMR-D status were significantly associated with tumor location and tumor differentiation extent. In our study, smoking has been divided into ever smoker versus never smoker. In univariate analysis, KRAS mutations were significantly associated with never smoking.

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of KRAS mutation

| KRAS mutation | Mutant (N = 324) | Wild (N = 580) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 63.4±12.9 | 62.2±11.1 | 0.054 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 175 | 366 | 0.128 |

| Female | 149 | 214 | |

| HTN | |||

| No | 184 | 334 | 0.871 |

| Yes | 140 | 246 | |

| DM | |||

| No | 269 | 458 | 0.165 |

| Yes | 55 | 122 | |

| Smoking | |||

| No | 265 | 432 | 0.0153 |

| Yes | 59 | 148 | |

| Cancer family history | |||

| No | 272 | 487 | 0.996 |

| Yes | 52 | 93 | |

| Tumor location, n (%) | |||

| Cecum | 21 (6.5) | 11 (1.9) | |

| Ascending colon | 73 (22.5) | 77 (13.3) | |

| Transverse colon | 19 (5.9) | 35 (6.0) | 0.0001 |

| Lt. colon | 117 (36.1) | 268 (46.2) | |

| Rectum | 91 (28.1) | 171 (29.5) | |

| Multiple | 3 (0.9) | 18 (3.1) | |

| TNM stage | |||

| I | 69 | 115 | |

| II | 95 | 176 | 0.894 |

| III | 117 | 218 | |

| IV | 43 | 71 | |

| Mucinous type | |||

| No | 307 | 567 | 0.026 |

| Yes | 17 | 13 | |

| Differentiation | |||

| Well | 28 | 44 | |

| Moderate | 290 | 508 | 0.087 |

| Poor | 6 | 28 |

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of BRAF mutation

| BRAF mutation | Mutant (N = 29) | Wild (N = 875) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 63.2±13.8 | 62.63±11.7 | 0.834 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 19 | 522 | 0.659 |

| Female | 10 | 353 | |

| HTN | |||

| No | 15 | 503 | 0.670 |

| Yes | 14 | 372 | |

| DM | |||

| No | 23 | 704 | 0.815 |

| Yes | 6 | 171 | |

| Smoking | |||

| No | 22 | 675 | 0.825 |

| Yes | 7 | 200 | |

| Cancer family history | |||

| No | 25 | 734 | 0.938 |

| Yes | 4 | 141 | |

| Tumor location, n (%) | |||

| Cecum | 4 (13.8) | 28 (3.2) | |

| Ascending colon | 8 (27.6) | 142 (16.2) | |

| Transverse colon | 4 (13.8) | 50 (5.7) | 0.001 |

| Lt. colon | 7 (24.1) | 378 (43.2) | |

| Rectum | 5 (17.2) | 257 (29.4) | |

| Multiple | 1 (3.4) | 20 (2.3) | |

| TNM stage | |||

| I | 4 | 180 | |

| II | 6 | 265 | 0.119 |

| III | 14 | 321 | |

| IV | 5 | 109 | |

| Mucinous type | |||

| No | 27 | 847 | 0.250 |

| Yes | 2 | 28 | |

| Differentiation | |||

| Well | 0 | 72 | |

| Moderate | 23 | 775 | 0.001 |

| Poor | 6 | 28 |

Table 4.

Univariate analysis of MMR status

| MMR | MMR-D (N = 69) | MMR-I (N = 835) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 59.6±14.9 | 62.9±11.4 | 0.073 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 36 | 505 | |

| Female | 33 | 330 | 0.221 |

| HTN | |||

| No | 45 | 473 | 0.209 |

| Yes | 24 | 362 | |

| DM | |||

| No Yes | 62 7 | 665 170 | 0.058 |

| No | 62 | 665 | |

| Smoking | |||

| No | 53 | 644 | 0.953 |

| Yes | 16 | 191 | |

| Cancer family history | |||

| No | 54 | 705 | |

| Yes | 15 | 130 | 0.241 |

| Tumor location, n (%) | |||

| Cecum | 8 (11.6) | 24 (2.9) | |

| Ascending colon | 22 (31.9) | 128 (15.3) | |

| Transverse colon | 9 (13.0) | 45 (5.4) | 0.0001 |

| Lt. colon | 15 (21.7) | 370 (44.3) | |

| Rectum | 13 (18.8) | 249 (29.8) | |

| Multiple | 2 (2.9) | 19 (2.3) | |

| TNM stage | |||

| I | 18 | 166 | 0.116 |

| II | 23 | 248 | |

| III | 21 | 314 | |

| IV | 7 | 107 | |

| Mucinous type | |||

| No | 64 | 810 | 0.071 |

| Yes | 5 | 25 | |

| Differentiation | |||

| Well | 3 | 69 | |

| Moderate | 51 | 747 | 0.001 |

| Poor | 15 | 19 |

Multivariate analysis was performed by collecting variables that were likely to be highly related in univariate analysis. Table 5 summarizes the results of multivariate logistic regression analysis. Even though highly related, differentiation and KRAS mutation had no statistical significance in univariate analysis. When analyzed in multivariate analysis, differentiation was statistically meaningful in KRAS mutation. Similarly, in MMR-D, age and TNM stage were found to be statistically significant only in multivariate analysis.

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of KRAS mutation, BRAF mutation, and MMR status

|

KRAS mutant |

BRAF mutant |

MMR-D |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.99–1.02 | 0.313 | 1.03 | 1.01–1.06 | 0.014 | |||

| TNM stage | 1.34 | 0.88–2.05 | 0.173 | 1.42 | 1.02–1.97 | 0.038 | |||

| Location | 0.74 | 0.62–0.89 | 0.001 | 0.47 | 0.27–0.81 | 0.006 | 2.19 | 1.45–3.33 | 0.001 |

| Differentiation | 0.67 | 0.45–1.00 | 0.047 | 5.31 | 2.04–13.8 | 0.001 | 0.15 | 0.06–0.35 | 0.001 |

| Mucinous type | 2.59 | 1.21–5.51 | 0.013 | ||||||

| Smoking | 0.64 | 0.45–0.90 | 0.011 | ||||||

Survival Analysis

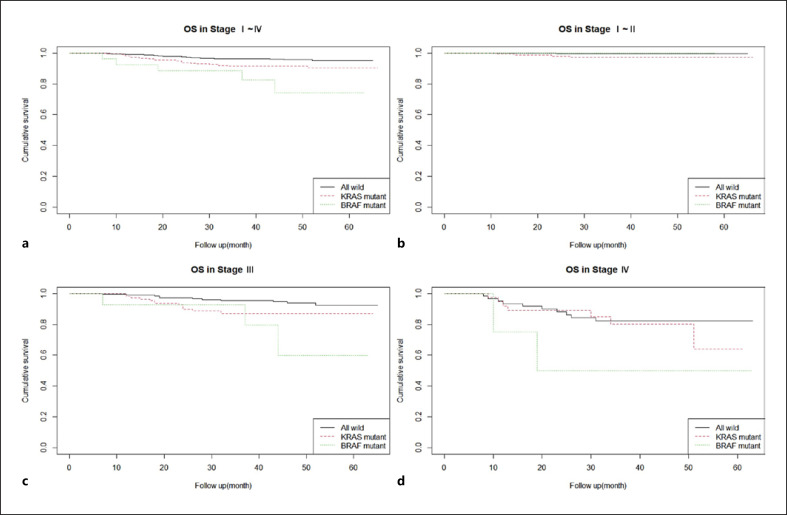

For OS analysis, all patients were categorized into three groups: wild type, KRAS mutant, and BRAF mutant. OSs were compared according to TNM stage (shown in Fig. 1) (i.e., stages I–IV, I–II, III, and IV). The results of Cox multivariate analyses are summarized in Table 6.

Fig. 1.

OS at stage I–IV (p value = 0.001, KRAS HR = 2.105, BRAF HR = 5.285) (a), stage I–II (p value = 0.09) (b), stage III (p value = 0.02, KRAS HR = 2.281, BRAF HR = 4.527) (c), and stage IV (p value = 0.2) (d) in wild type, KRAS mutant, and BRAF mutant.

Table 6.

Cox analysis of OS in stage I to stage IV patients

| Stage I–IV |

Stage I–II |

Stage III |

Stage IV |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Sex | 4.64 | 1.67–12.85 | 1.54 | 0.25–9.43 | 0.69 | 0.3–1.58 | 1.06 | 0.38–2.97 |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.99–1.04 | 0.99 | 0.93–1.07 | 1.03 | 0.99–1.07 | 1 | 0.96–1.04 |

| Location | 1.02 | 0.71–1.45 | 0.9 | 0.29–2.79 | 0.89 | 0.55–1.45 | 1.05 | 0.57–1.91 |

| Differentiation | 1.58 | 0.66–3.76 | 0.3 | 0.03–2.84 | 2.55 | 0.66–9.87 | 0.67 | 0.13–3.44 |

| Mucinous type | 1.54 | 0.47–5.04 | 3.74 | 1.01–13.76 | ||||

| KRAS | 2.12 | 1.18–3.81 | 6.89 | 0.75–62.99 | 2.73 | 1.17–6.39 | 1.32 | 0.48–3.63 |

| BRAF | 4.64 | 1.67–12.85 | 3.63 | 0.92–14.38 | 4.27 | 0.7–26 | ||

| MMR | 0.93 | 0.35–2.47 | 0.13 | 0.02–0.97 | 1.37 | 0.27–6.86 | 1.51 | 0.2–11.43 |

For stage I–IV patients, significant OS differences were apparent among the three groups in both univariate (p value = 0.001, KRAS HR = 2.105, BRAF HR = 5.285) and multivariate analyses. However, such differences were not apparent for stage I–II patients or stage IV patients. For stage III patients, the OSs of KRAS- and BRAF-mutant patients were shorter in univariate analysis (p value = 0.02, KRAS HR = 2.281, BRAF HR = 4.527). However, in multivariate analysis, only KRAS mutations were significantly prognostic.

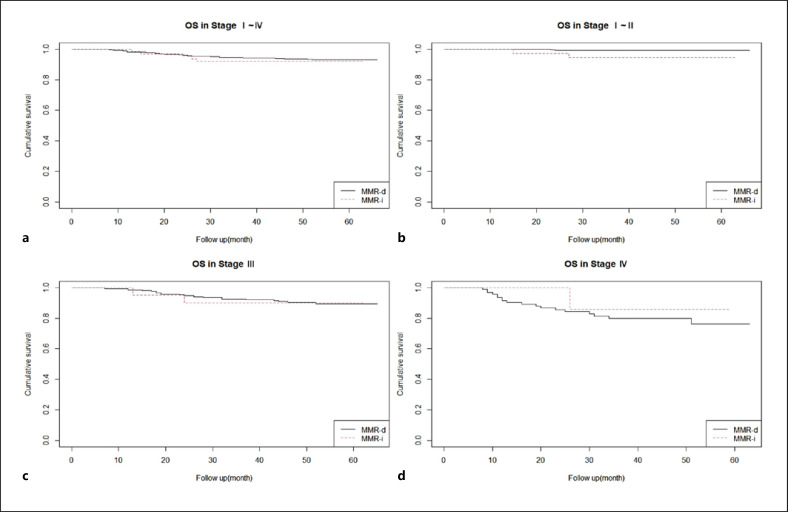

OSs were also compared according to TNM stage and MMR status (shown in Fig. 2). In stage I–II, the OSs significantly differed between MMR-D and MMR-I patients in both univariate (p value = 0.01, MMR-I HR = 6.913) and multivariate analyses.

Fig. 2.

OS at stage I–IV (p value = 0.7) (a), stage I–II (p value = 0.01, MMR-I HR = 6.913) (b), stage III (p value = 0.9) (c), and stage IV (p value = 0.6) (d) in MMR-D and MMR-I.

Conclusion

We evaluated KRAS, BRAF, and MMR statuses in 904 Korean CRC patients. Recent studies have explored the prognostic utilities of these parameters, as well as their combinations, in CRC patients [23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29]. The 5-year survival rates of patients with early stage CRC (TNM stage I–II) approach 90%. However, the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program database indicates that the survival rate of patients diagnosed with late-stage CRC is only 15.1% [30]. Thus, early diagnosis of CRC is important. There is a need for biomarkers that allow CRC screening and facilitate predictions of prognosis and treatment response.

We found a KRAS mutation rate of 35.8%, consistent with a previous report [31]. However, our BRAF mutation rate was lower than the rates previously reported (8–12%) [32]. Asian countries exhibit lower BRAF mutation rates than Western countries [33]; ethnic differences may influence these findings. Approximately 3–13% of Asian CRC patients have exhibited MMR-D status in previous studies; our results are similar [34]. In contrast, MMR-D CRC constituted approximately 15–20% of all CRCs in Western studies. MMR-D status can be detected by IHC or MSI analyses. CRC patients exhibit good concordance between MLH1/PMS2/MSH2/MSH6 IHC data and the results of MSI analysis via fluorescent PCR combined with fragment length measurement [35].

In univariate analysis of clinicopathological parameters, we found that the tumor locations significantly differed among patients. Compared with wild-type CRCs, KRAS- and BRAF-mutated CRCs were more common in the right colon. Furthermore, MMR-D CRCs were more frequent in the right colon compared with MMR-I CRCs. Salem et al. [36] reported KRAS mutations in 61–71% of right colon CRCs. Yamauchi et al. [37] found high MMR-D and BRAF mutation rates in CRCs of the ascending and transverse colons, as well as CRCs of the hepatic flexure. We subdivided right colon CRCs into cecal cancers, ascending CRCs, and transverse CRCs. MMR-D and BRAF mutations were common in all such tumors; however, KRAS mutations were only frequent in cecal and ascending colon tumors.

In our study, smoking was closely associated with CRCs characterized by KRAS mutation-negative. Consistent with our findings, Samadder et al. [38] reported that smoking-related risk estimates were higher for KRAS mutation-negative than for KRAS mutation-positive tumors. Chen et al. [39] performed a meta-analysis that smoking showed positive correlation with BRAF mutation and MSI positivity. However, in our study, smoking had no statistically significant relationship between BRAF mutation and MMR status. In the study by Chen et al. [39], smoking status was classified as nonsmokers who had less than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime and smokers (former or current). Smoking pack-years or cessation period has not been recorded in our study. Additionally, there were insufficient number of individuals with MMR-D and BRAF mutations who smoked (n = 16 and 7, respectively) to provide accurate assessment. Tailored smoking status and abundant subgroup patient number should be needed to validate precise relationship.

Patients with stag I–IV CRC who had KRAS mutations exhibited poor OS. However, the prognostic utility of KRAS mutations requires further investigation in patients with stages I–II and IV CRC; the results are controversial [18, 40, 41]. Hutchins et al. [40] reported that the risk of recurrence was higher in stage II and III patients with KRAS mutations than in such patients with wild-type tumors [42]. However, Roth et al. [18] found that KRAS mutations were not prognostic in stage II-III CRC patients. It may be difficult to predict prognosis using KRAS status alone; MMR status greatly influences chemotherapy decision-making for stage II patients. It may be necessary to examine multiple factors when determining the effects of KRAS mutations according to disease stage.

Most KRAS mutations are in codons 12 and 13 of exon 2 [31]. For the various RAS genes (HRAS, NRAS, and KRAS), specific exon/codon mutations are associated with typical clinical, pathological, and molecular features [42]. The RAS genes are highly homologous; they are nearly identical in the regions that encode the first 90% of all proteins [43]. Of all RAS mutations in human tumors, mutations in KRAS constitute approximately 85%, mutations in NRAS constitute approximately 15%, and mutations in HRAS constitute <1% [44]. In this study, we were unable to analyze differences according to codon mutation site; the sites were not defined in all patients. Because tumor activity can be affected by codon mutation site, any prognostic difference between KRAS codon 12 and 13 mutations requires further investigation.

We found that BRAF status was significantly associated with prognosis only in stage I–IV patients. A few small cohort studies have reported that BRAF mutations are poorly prognostic in stage II and III patients [45]. However, the prognostic utility of BRAF mutations varies when MMR status is considered. In other studies, BRAF mutations constituted an independent negative prognostic factor in MMR-I patients with stages II and III CRC [46, 47]. However, in MMR-D patients, BRAF mutations were not independently prognostic [48]. The differences may be attributed to the low BRAF mutation rate in Asian countries, where BRAF mutations are present in only 8–12% of all CRCs [49]. Our BRAF mutation rate was only 3.2%.

We found that MMR-D status was a useful prognostic factor in stage I–II patients. Klingbiel et al. [50] analyzed 1,254 patients; they found that MMR-D status was associated with better OS in stage II patients and longer relapse-free survival in stage III patients. In contrast, Phipps et al. [51] pooled data from seven studies with 5,010 patients; they found that non-MMR-D patients exhibited significantly shorter disease-specific survival (compared with MMR-D patients), regardless of other tumor markers or disease stage. The differences may be attributed to differences in sample size. As mentioned, various classifications by molecular subtype including CMS were introduced recently [5]. However, we could not compare prognosis by these classifications with our results because biomarkers from our study were limited. Further studies are required to validate prognosis with these classifications in Korean CRC patients.

Our study had some limitations. First, the number of patients with BRAF mutations was insufficient to yield reliable results in Cox analysis of OS among patients with stag I–II CRC. Second, we could not evaluate NRAS mutations because of insufficient data. Although KRAS- and NRAS-mutant CRCs exhibit similar clinical characteristics, previous studies suggested that NRAS mutations were predictive of resistance to anti-EGFR monoclonal antibodies [52]. Thus, further analysis is required. Third, we did not subdivide the BRAF mutations according to V600E/non-V600E status. Most BRAF mutations are V600E (>90%). BRAF non-V600E mutations are often accompanied by RAS mutations; such patients exhibit longer OS [53].

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first multicenter study to explore the prognostic utilities of KRAS, BRAF, and MMR statuses in Korean CRC patients. In Korean CRC patients, the prognostic utilities of KRAS and BRAF mutations, as well as MMR status, suggest that the various TNM stages are associated with different risk factors. KRAS mutation was an independent risk factor for shorter OS in stage I–IV and stage III. BRAF mutation was an independent risk factor for shorter OS in stage I–IV tumors. MMR-I status was an independent risk factor for shorter OS in stage I–II.

Statement of Ethics

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary's Hospital (approval number: KC17RCDI0781). The Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary's Hospital decided that written informed consent was not required because anonymizing the identifiable information in the patients' medical records would not have a negative impact on their rights or welfare. Also, without the waiver of consent, this study could not practicably be conducted.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This article was not funded.

Author Contributions

Tae-Woo Kim has contributed in writing and editing the paper as the first author; Soon Woo Hwang has contributed in drafting of the manuscript; Kyeong Ok Kim, Jae Myung Cha, and Young-Eun Joo have contributed in data acquisition and study design; and Young-Seok Cho has revised the manuscript critically.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Funding Statement

This article was not funded.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020 GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 May;71((3)):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold M, Sierra MS, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global patterns and trends in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Gut. 2017 Apr;66((4)):683–691. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunican DS, McWilliam P, Tighe O, Parle-McDermott A, Croke DT. Gene expression differences between the microsatellite instability (MIN) and chromosomal instability (CIN) phenotypes in colorectal cancer revealed by high-density cDNA array hybridization. Oncogene. 2002 May 9;21((20)):3253–3257. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012 Jul 18;487((7407)):330–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong SN. Genetic and epigenetic alterations of colorectal cancer. Intest Res. 2018 Jul;16((3)):327–337. doi: 10.5217/ir.2018.16.3.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boland CR, Goel A. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010 Jun;138((6)):2073.e3–2087.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mármol I, Sánchez-de-Diego C, Pradilla Dieste A, Cerrada E, Rodriguez Yoldi MJ. Colorectal carcinoma a general overview and future perspectives in colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Jan 19;18((1)):197. doi: 10.3390/ijms18010197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guinney J, Dienstmann R, Wang X, de Reyniès A, Schlicker A, Soneson C. The consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer. Nat Med. 2015 Nov;21((11)):1350–1356. doi: 10.1038/nm.3967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Müller MF, Ibrahim AEK, Arends MJ. Molecular pathological classification of colorectal cancer. Virchows Arch. 2016 Aug;469((2)):125–134. doi: 10.1007/s00428-016-1956-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thanki K, Nicholls ME, Gajjar A, Senagore AJ, Qiu S, Szabo C, et al. Consensus molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer and their clinical implications. Int Biol Biomed J. 2017;3((3)):105–111. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fessler E, Drost J, van Hooff SR, Linnekamp JF, Wang X, Jansen M. TGFβ signaling directs serrated adenomas to the mesenchymal colorectal cancer subtype. EMBO Mol Med. 2016 Jul;8((7)):745–760. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bellio H, Fumet JD, Ghiringhelli F. Targeting BRAF and RAS in colorectal cancer. Cancers. 2021 May 3;13((9)):2201. doi: 10.3390/cancers13092201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pino MS, Chung DC. The chromosomal instability pathway in colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010 Jun;138((6)):2059–2072. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leclerc J, Vermaut C, Buisine MP. Diagnosis of Lynch syndrome and strategies to distinguish Lynch-related tumors from sporadic MSI/dMMR tumors. Cancers. 2021 Jan 26;13((3)):467. doi: 10.3390/cancers13030467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim B, Park SJ, Cheon JH, Kim TI, Kim WH, Hong SP. Clinical meaning of BRAF mutation in Korean patients with advanced colorectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Apr 21;20((15)):4370–4376. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i15.4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahuja N, Mohan AL, Li Q, Stolker JM, Herman JG, Hamilton SR, et al. Association between CpG island methylation and microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 1997 Aug 15;57((16)):3370–3374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poynter JN, Siegmund KD, Weisenberger DJ, Long TI, Thibodeau SN, Lindor N. Molecular characterization of MSI-H colorectal cancer by MLHI promoter methylation and mismatch repair germline mutation screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008 Nov;17((11)):3208–3215. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roth AD, Tejpar S, Delorenzi M, Yan P, Fiocca R, Klingbiel D. Prognostic role of KRAS and BRAF in stage II and III resected colon cancer results of the translational study on the PETACC-3, EORTC 40993, SAKK 60-00 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010 Jan 20;28((3)):466–474. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.3452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Geiersbach KB, Samowitz WS. Microsatellite instability and colorectal cancer. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011 Oct;135((10)):1269–1277. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2011-0035-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pino MS, Chung DC. Microsatellite instability in the management of colorectal cancer. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Jun;5((3)):385–399. doi: 10.1586/egh.11.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Samowitz WS. Evaluation of colorectal cancers for Lynch syndrome practical molecular diagnostics for surgical pathologists. Mod Pathol. 2015 Jan;28((S1)):S109–S113. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2014.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang HJ, Park CK, Kim WH, Kim YB, Kim YW, Kim HG, et al. A standardized pathology report for colorectal cancer. Korean J Pathol. 2006;40((3)):193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Asaka S, Arai Y, Nishimura Y, Yamaguchi K, Ishikubo T, Yatsuoka T, et al. Microsatellite instability-low colorectal cancer acquires a KRAS mutation during the progression from Dukes' A to Dukes' B. Carcinogenesis. 2009 Mar;30((3)):494–499. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nash GM, Gimbel M, Cohen AM, Zeng ZS, Ndubuisi MI, Nathanson DR, et al. KRAS mutation and microsatellite instability two genetic markers of early tumor development that influence the prognosis of colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010 Feb;17((2)):416–424. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cushman-Vokoun AM, Stover DG, Zhao Z, Koehler EA, Berlin JD, Vnencak-Jones CL. Clinical utility of KRAS and BRAF mutations in a cohort of patients with colorectal neoplasms submitted for microsatellite instability testing. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2013 Sep;12((3)):168–178. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2013.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phipps AI, Limburg PJ, Baron JA, Burnett-Hartman AN, Weisenberger DJ, Laird PW. Association between molecular subtypes of colorectal cancer and patient survival. Gastroenterology. 2015 Jan;148((1)):77.e2–87.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu J, Yan WY, Xie L, Cheng L, Yang M, Li L, et al. Coexistence of MSI with KRAS mutation is associated with worse prognosis in colorectal cancer. Medicine. 2016 Dec;95((50)):e5649. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murcia O, Juárez M, Rodríguez-Soler M, Hernández-Illán E, Giner-Calabuig M, Alustiza M. Colorectal cancer molecular classification using BRAF microsatellite instability and CIMP status prognostic implications and response to chemotherapy. PLoS One. 2018;13((9)):e0203051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Niu W, Wang G, Feng J, Li Z, Li C, Shan B. Correlation between microsatellite instability and RAS gene mutation and stage III colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett. 2019 Jan;17((1)):332–338. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.NCICancerStats Cancer of the colon and rectum Cancer Stat Facts. 2022.

- 31.Afrăsânie VA, Marinca MV, Alexa-Stratulat T, Gafton B, Păduraru M, Adavidoaiei AM, et al. KRAS HER2 and microsatellite instability in metastatic colorectal cancer practical implications for the clinician. Radiol Oncol. 2019 Sep 24;53((3)):265–274. doi: 10.2478/raon-2019-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caputo F, Santini C, Bardasi C, Cerma K, Casadei-Gardini A, Spallanzani A, et al. BRAF-mutated colorectal cancer clinical and molecular insights. Int J Mol Sci. 2019 Oct 28;20((21)):E5369. doi: 10.3390/ijms20215369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guo TA, Wu YC, Tan C, Jin YT, Sheng WQ, Cai SJ, et al. Clinicopathologic features and prognostic value of KRAS NRAS and BRAF mutations and DNA mismatch repair status a single-center retrospective study of 1,834 Chinese patients with Stage I–IV colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2019 Sep 15;145((6)):1625–1634. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Battaglin F, Naseem M, Lenz HJ, Salem ME. Microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer overview of its clinical significance and novel perspectives. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2018 Nov;16((11)):735–745. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dedeurwaerdere F, Claes KB, Van Dorpe J, Rottiers I, Van der Meulen J, Breyne J, et al. Comparison of microsatellite instability detection by immunohistochemistry and molecular techniques in colorectal and endometrial cancer. Sci Rep. 2021 Jun 18;11((1)):12880. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91974-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salem ME, Battaglin F, Goldberg RM, Puccini A, Shields AF, Arguello D. Molecular analyses of left- and right-sided tumors in adolescents and young adults with colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2020 May;25((5)):404–413. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yamauchi M, Morikawa T, Kuchiba A, Imamura Y, Qian ZR, Nishihara R. Assessment of colorectal cancer molecular features along bowel subsites challenges the conception of distinct dichotomy of proximal versus distal colorectum. Gut. 2012 Jun;61((6)):847–854. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samadder NJ, Vierkant RA, Tillmans LS, Wang AH, Lynch CF, Anderson KE. Cigarette smoking and colorectal cancer risk by KRAS mutation status among older women. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 May;107((5)):782–789. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen K, Xia G, Zhang C, Sun Y. Correlation between smoking history and molecular pathways in sporadic colorectal cancer a meta-analysis. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8((3)):3241–3257. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hutchins G, Southward K, Handley K, Magill L, Beaumont C, Stahlschmidt J. Value of mismatch repair and BRAF mutations in predicting recurrence and benefits from chemotherapy in colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011 Apr 1;29((10)):1261–1270. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dienstmann R, Mason MJ, Sinicrope FA, Phipps AI, Tejpar S, Nesbakken A. Prediction of overall survival in stage II and III colon cancer beyond TNM system a retrospective, pooled biomarker study. Ann Oncol. 2017 May 1;28((5)):1023–1031. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dobre M, Dinu DE, Panaitescu E, Bîrlă RD, Iosif CI, Boeriu M. KRAS gene mutations prognostic factor in colorectal cancer? Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56((2 Suppl)):671–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Irahara N, Baba Y, Nosho K, Shima K, Yan L, Dias-Santagata D. NRAS mutations are rare in colorectal cancer. Diagn Mol Pathol. 2010 Sep;19((3)):157–163. doi: 10.1097/PDM.0b013e3181c93fd1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Downward J. Targeting RAS signalling pathways in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003 Jan;3((1)):11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fariña-Sarasqueta A, van Lijnschoten G, Moerland E, Creemers GJ, Lemmens V, Rutten HJT, et al. The BRAF V600E mutation is an independent prognostic factor for survival in stage II and stage III colon cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2010 Dec;21((12)):2396–2402. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gavin PG, Colangelo LH, Fumagalli D, Tanaka N, Remillard MY, Yothers G. Mutation profiling and microsatellite instability in stage II and III colon cancer an assessment of their prognostic and oxaliplatin predictive value. Clin Cancer Res. 2012 Dec 1;18((23)):6531–6541. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Taieb J, Le Malicot K, Shi Q, Penault Lorca F, Bouché O, Tabernero J. Prognostic value of BRAF and KRAS mutations in MSI and MSS stage III colon cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017 May;109((5)):djw272. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sinicrope FA, Shi Q, Allegra CJ, Smyrk TC, Thibodeau SN, Goldberg RM. Association of DNA mismatch repair and mutations in BRAF and KRAS with survival after recurrence in stage III colon cancers a secondary analysis of 2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Oncol. 2017 Apr 1;3((4)):472–480. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanz-Garcia E, Argiles G, Elez E, Tabernero J. BRAF mutant colorectal cancer prognosis, treatment, and new perspectives. Ann Oncol. 2017 Nov 1;28((11)):2648–2657. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klingbiel D, Saridaki Z, Roth AD, Bosman FT, Delorenzi M, Tejpar S. Prognosis of stage II and III colon cancer treated with adjuvant 5-fluorouracil or FOLFIRI in relation to microsatellite status results of the PETACC-3 trial. Ann Oncol. 2015 Jan;26((1)):126–132. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdu499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Phipps AI, Alwers E, Harrison T, Banbury B, Brenner H, Campbell PT. Association between molecular subtypes of colorectal tumors and patient survival based on pooled analysis of 7 international studies. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jun;158((8)):2158.e4–2168.e4. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schirripa M, Cremolini C, Loupakis F, Morvillo M, Bergamo F, Zoratto F, et al. Role of NRAS mutations as prognostic and predictive markers in metastatic colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;136((1)):83–90. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zarkavelis G, Boussios S, Papadaki A, Katsanos KH, Christodoulou DK, Pentheroudakis G. Current and future biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Ann Gastroenterol. 2017;30((6)):613–621. doi: 10.20524/aog.2017.0191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.