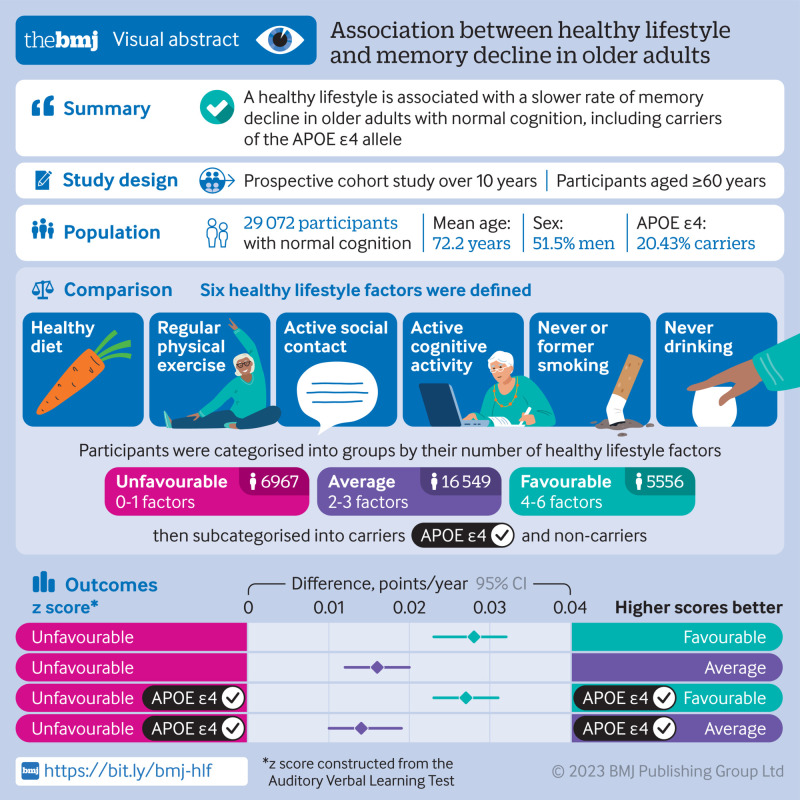

Abstract

Objective

To identify an optimal lifestyle profile to protect against memory loss in older individuals.

Design

Population based, prospective cohort study.

Setting

Participants from areas representative of the north, south, and west of China.

Participants

Individuals aged 60 years or older who had normal cognition and underwent apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotyping at baseline in 2009.

Main outcome measures

Participants were followed up until death, discontinuation, or 26 December 2019. Six healthy lifestyle factors were assessed: a healthy diet (adherence to the recommended intake of at least 7 of 12 eligible food items), regular physical exercise (≥150 min of moderate intensity or ≥75 min of vigorous intensity, per week), active social contact (≥twice per week), active cognitive activity (≥twice per week), never or previously smoked, and never drinking alcohol. Participants were categorised into the favourable group if they had four to six healthy lifestyle factors, into the average group for two to three factors, and into the unfavourable group for zero to one factor. Memory function was assessed using the World Health Organization/University of California-Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test, and global cognition was assessed via the Mini-Mental State Examination. Linear mixed models were used to explore the impact of lifestyle factors on memory in the study sample.

Results

29 072 participants were included (mean age of 72.23 years; 48.54% (n=14 113) were women; and 20.43% (n=5939) were APOE ε4 carriers). Over the 10 year follow-up period (2009-19), participants in the favourable group had slower memory decline than those in the unfavourable group (by 0.028 points/year, 95% confidence interval 0.023 to 0.032, P<0.001). APOE ε4 carriers with favourable (0.027, 95% confidence interval 0.023 to 0.031) and average (0.014, 0.010 to 0.019) lifestyles exhibited a slower memory decline than those with unfavourable lifestyles. Among people who were not carriers of APOE ε4, similar results were observed among participants in the favourable (0.029 points/year, 95% confidence interval 0.019 to 0.039) and average (0.019, 0.011 to 0.027) groups compared with those in the unfavourable group. APOE ε4 status and lifestyle profiles did not show a significant interaction effect on memory decline (P=0.52).

Conclusion

A healthy lifestyle is associated with slower memory decline, even in the presence of the APOE ε4 allele. This study might offer important information to protect older adults against memory decline.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03653156.

Introduction

Although a fundamental function of daily life, memory continuously declines as people age,1 impairing both life quality and work productivity and increasing the risk of dementia.2 3 4 However, age related memory decline is not always a prodrome of dementia; memory loss can merely be senescent forgetfulness, which is more prevalent among older individuals, and can be reversed or become stable rather than progress to a pathological state.5 Thus, the prevention and slowing of age related memory decline in older individuals is paramount. Fortunately, memory decline can be mutable because various contributing factors are reportedly associated with memory loss.

Studies have been conducted to identify factors that might affect memory, including ageing, the apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4 genotype, chronic diseases, and lifestyle patterns.6 7 Among these, lifestyle has received increasing attention as a modifiable behaviour because this factor is relatively easily amendable with potential benefits for overall health as well as memory. Studies on the effect of a healthy lifestyle on cognition are increasing.8 9 10 11 12 However, few studies have focused on its effect on memory, and most were cross sectional in nature,13 which is insufficient to evaluate the relationship between a long term healthy lifestyle and memory decline. Additionally, those studies did not consider the interaction between a healthy lifestyle and genetic risk; thus, the exact effect of a healthy lifestyle on memory decline in individuals with a higher genetic risk remains unknown. Therefore, longitudinal studies are needed to further investigate the effect of modifiable lifestyle factors on memory decline in older individuals, considering genetic risks, such as the presence of an APOE ε4 genotype.

We used data from a large population based cohort (the China Cognition and Ageing Study; COAST) to investigate whether adherence to a combination of healthy lifestyle factors was associated with a slower memory decline in cognitively normal older adults, even those genetically susceptible to memory decline.

Methods

Study design and participants

The COAST is a nationwide, population based, cohort study on dementia in China (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT03653156). This investigation included individuals from 12 provinces from the north, south, and west of China, representing the geographical characteristics, degree of urbanisation, economic status, dietary patterns, and cultural and social differences in China. We conducted a multistage, stratified, cluster sampling procedure, which considered sex and age distribution, among these provinces. A total of 96 study sites (48 urban and 48 rural) were randomly selected (supplementary 1). Written or oral informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The study enrolment procedure began on 8 May 2009 and comprised two sequential phases (lasting about six months together). In phase 1, individuals aged 60 years or older, who gave consent to participate in the study, were listed in the community census or village registry, and had resided there for at least one year preceding the survey date, were included in the study. We excluded participants with a life threatening disease, hearing loss, or vision loss. In phase 2, participants from phase 1 with available APOE genotyping and without mild cognitive impairment or dementia were included. Four rounds of follow-up were conducted—ie, a follow-up any time in 2012, 2014, 2016, and 2019. The end date of the study was 26 December 2019.

Diagnosis of dementia and mild cognitive impairment

The aim of this study was to investigate the association between lifestyle and memory in participants with normal cognitive function throughout the study period. Neuropsychological tests were done to determine the cognitive status of the participants at baseline and at each follow-up. For people who progressed to mild cognitive impairment or dementia during the follow-up period, the data after their diagnosis were excluded in the main analyses. Global cognitive function was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination,14 which evaluates orientation, attention, calculation, executive function, language, among others. The total score of the Mini-Mental State Examination ranges from 0 to 30, with higher scores representing a better cognitive function. Participants whose score was less than 26 were suspected of cognitive impairment and would receive further evaluation, including physical and other neuropsychological testing. The results and participants’ medical records were reviewed by neurologists who were masked to the genetic results. Dementia was diagnosed on the consensus of at least two neurologists, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edition, text revision criteria).15 Mild cognitive impairment was diagnosed according to the Peterson criteria.16 Having normal cognitive function was defined as having a score of 0 for the Clinical Dementia Rating.17 People for whom a consensus could not be reached were considered controversial cases. These cases would be discussed and diagnosed by an expert group, which included senior neurologists, psychiatrists, and neuropsychologists.

Assessment of lifestyle factors

Lifestyle information was collected at baseline and each follow-up based on each individual’s performance over the past year through a healthy behaviour questionnaire (supplementary 2). We assessed lifestyle status by six modifiable lifestyle factors: physical exercise, diet, drinking, smoking, cognitive activity, and social contact. For physical exercise, weekly frequency and total time were collected, and at least 150 min of moderate or 75 min of vigorous activity per week was considered a healthy factor, according to the American guidelines for physical activity in adults.18 For smoking, participants were categorised as smokes current, never (participants who had smoked <100 cigarettes in their lifetime) smokes, or used to smoke (participants who had quit smoking at least three years before). Never or former smoking was deemed a healthy lifestyle factor.19 For alcohol consumption, the current frequency and volume of alcohol consumption were recorded, and individuals were categorised into never drinking (never drank or drank occasionally), low to excess drinking (daily alcohol consumption of 1-60 g), and heavy drinking (daily alcohol consumption >60 g).20 The category of never drinking was deemed a healthy lifestyle factor.21 The remaining three lifestyle factors were deemed healthy based on the top 40% of the population distribution, according to previous studies.22 23 24 25 For diet, we recorded the participant’s daily intake of 12 food items (fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, dairy products, salt, oil, eggs, cereals, legumes, nuts, and tea) (supplementary 2).26 For cognitive activity (writing, reading, playing cards, mahjong, and other games) and social contact (participation in meetings or attending parties, visiting friends or relatives, travelling, and chatting online), engagement frequencies were investigated. Ultimately, these factors were deemed healthy when participants consumed appropriate daily amounts of at least 7 of the 12 food items for diet, and they engaged in cognitive activity or social contact at least twice weekly in this study.

We evaluated the association of each single lifestyle factor with memory function. For further investigation of the combined effect of lifestyle factors on memory function, we categorised participants into three groups based on the third of the number of healthy lifestyle factors: favourable (4-6 healthy factors), average (2-3), and unfavourable (0-1). To investigate the effect of lifestyle on memory stratified by APOE genotypes, participants were also grouped into people who were APOE ε4 carriers and people who were not carriers.

Outcomes

Memory function was measured at baseline and each follow-up using the World Health Organization/University of California-Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT),27 which included measurement of immediate recall, short delay free recall (3 min later), long delay free recall (30 min later), and long delay recognition. During the test, a rater read a list of words consisting of 15 nouns; immediately after its completion, the participant attempted to repeat as many words as possible. The score of immediate recall was 0-60, and the scores of all other tests were 0-15. The standard z scores for the auditory verbal learning test were calculated based on the respective mean and standard deviation test scores. The composite z score for memory function was constructed by averaging the z scores for each test in the auditory verbal learning test.

Covariates

Potential confounders were selected based on directed acyclic graphs (supplementary figure 1) depicting the best known relations between the variables in this study. Sociodemographic information obtained at baseline were sex, place of residence (rural or urban), region (north, west, or south), marital status (married, widowed, or divorced/separated/single), years of education (<1 year, 1-6 years, 7-12 years, >12 years), monthly household income (1000-2999, 3000-4999, 5000-10 000, >10000 Chinese Yuan), occupation (manual labourer, office worker, household, or others). Health related covariates were collected at baseline and each follow-up, including age, body mass index and medical illnesses (hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, heart attack, head injury, cerebrovascular disease, and depression). We also included the learning effect of each participant as a covariate due to repeated cognitive assessments.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics of the analytical sample were summarised across three lifestyle groups as a percentage for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. Missing values are summarised in supplementary table 1. A multiple imputation chain-equation was used to impute missing data. Data were assumed to be missing at random. Missing continuous variables were imputed using predictive mean matching method, and binary variables were imputed by Logistic regression model. We generated five imputed datasets with 100th iteration, and analysed each dataset separately, then combined their results by use of Rubin’s method.

Linear mixed effects models were used in this study, and all statistical assumptions were tested before interpretation of results. The data met the distributional requirements in each case. We examined the effects of different lifestyle profiles, APOE ε4 status, as well as their interactions on longitudinal memory trajectories in participants with normal cognition throughout the study by use of linear mixed effects models. The composite z score of the auditory verbal learning test was the dependent variable. The fixed effects were the following: lifestyle profiles (each respective lifestyle factor as well as the combination); APOE ε4 status; time (follow-up year from baseline); two way interactions of lifestyle with APOE ε4 status and time; and three way interactions between lifestyle, APOE ε4 status, and time. The random effects included intercept and time. Age (centred at 74 years to reduce the correlation between the age and age squared terms), age squared (to allow for the comparison of acceleration in the rate of memory decline between lifestyle groups), baseline memory score, learning effect (by assignment code to the first assessment as 1 versus subsequent assessments coded as 0), and other covariates were also adjusted in this model. In addition, the global cognitive trajectories in the cognitively normal population were evaluated using a linear mixed effects model with global cognition (standard z score of the Mini-Mental State Examination) as dependent variable. Furthermore, we investigated the interaction between lifestyle and age on memory decline.

As lifestyle status and some of the covariates changed over time, a time dependent Cox regression model (non-proportional hazard model) was used to assess the effect of lifestyle groups on progression to mild cognitive impairment or dementia in the total study population and APOE ε4 stratified population. In this model death and drop-out data were treated as censoring data. Additionally, we evaluated whether dropping out from the study affected the effects of lifestyle on mild cognitive impairment or dementia using an inverse probability weighting model. We also assessed the influence of death as a competing risk for mild cognitive impairment or dementia via competing risk analyses.

Sensitivity analyses

We conducted several additional sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of our findings. Firstly, we included the number of lifestyle factors as a continuous variable in the mixed model to test the rationale of our grouping method. Secondly, we derived a weighted standardised healthy lifestyle score based on the β coefficient of each lifestyle factor in the linear mixed effects model adjusted for covariates.28 Specifically, the original binary lifestyle variables were multiplied by the β coefficients, and all the β coefficients were summed. The score of each lifestyle factor was obtained via the β coefficient of each lifestyle factor divided by the sum of the β coefficients, multiplied by 100. Participants were categorised into three groups based on the third of weighted standardised score into low, intermediate, and high score groups. Third, we excluded each lifestyle factor to identify possible factors that might drive the associations with memory. The excluded lifestyle factor was used as a confounder. Fourthly, we excluded participants who later developed mild cognitive impairment or dementia to determine whether the results were consistent with the main results. Fifthly, we excluded participants who died or dropped out throughout the study in order to evaluate the possible effects of death or drop-out on the results (if the results were consistent when participants were excluded with when they were not excluded, death or drop-out would have had no effect on the results). Finally, to assess the reverse causality of memory decline and healthy lifestyle profile, we performed a cross-lagged panel model, which is used when examining reciprocal causal processes in longitudinal data with at least two waves of data. Each analysis included a cross-wave component that estimated the change in each outcome from one wave, characterised by relationships between outcomes from each specific wave. We examined changes in composite z scores for memory in relation to changes in healthy lifestyle profiles over time.

All statistical analyses were done in R (version 3.6.3). We used the following packages: mice, for imputing; lmerTest, for linear mixed effects models; cmprsk, for competing risk models; lavaan, for cross-lagged analysis; and ipw, for inverse probability weighting. The two tailed significance level was set at P<0.05.

Patient and public involvement

Participants of the COAST study were not involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for recruitment, design, or implementation of the study. No participants were asked for advice on interpreting or writing up of results. We know that the public involvement has great value in improving the quality of research; however, we did not have the necessary funding to invite participants for their advice. We intend to engage participants and the public to disseminate the results of our study.

Results

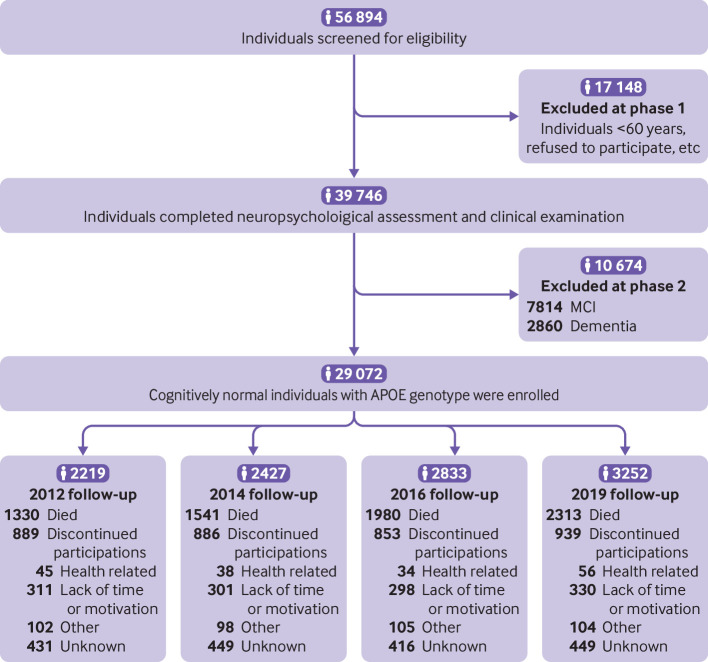

In total, 56 894 individuals were screened for eligibility. In phase 1, we excluded 17 148 individuals who were younger than 60 years or did not give permission to participate. In total, 39 746 individuals completed the neuropsychological assessment and clinical examination. In phase 2, we excluded 7814 individuals with mild cognitive impairment and 2860 individuals with dementia. Overall, we enrolled 29 072 with normal cognitive function who underwent APOE genotyping at baseline. During the 10 year follow-up period, 7164 individuals died and 3567 individuals discontinued participation for various reasons (fig 1).

Fig 1.

Study profile. MCI=mild cognitive impairment

Table 1 summarises the participants’ baseline demographic characteristics according to the three lifestyle groups. At baseline, all participants had normal cognitive function (48.54% female), with a mean age of 72.23 years (standard deviation 6.61), and 20.43% were carriers of APOE ε4 (supplementary table 2). Additionally, 6967 participants were enrolled in the unfavourable lifestyle group, 16 549 in the average group, and 5556 in the favourable group.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the cognitively normal population and time dependent healthy lifestyle groups at baseline. Data are number (%), unless otherwise specified

| Demographic characteristics | Total (n=29 072) | Healthy lifestyle groups | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unfavourable group (n=6967) | Average group (n=16 549) | Favourable group (n=5556) | |||||

| Female | 14 113 (48.54) | 3402 (48.83) | 7995 (48.31) | 2716 (48.88) | |||

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 72.23 (6.61) | 72.90 (6.74) | 72.30 (6.64) | 71.16 (6.22) | |||

| Place of residence: | |||||||

| Rural | 13742 (47.27) | 3263 (46.84) | 7812 (47.21) | 2667 (48.00) | |||

| Urban | 15 330 (52.73) | 3704 (53.16) | 8737 (52.79) | 2889 (52.00) | |||

| Region: | |||||||

| North | 8670 (29.82) | 2000 (28.71) | 4983 (30.11) | 1687 (30.36) | |||

| West | 9585 (32.97) | 2274 (32.64) | 5469 (33.05) | 1842 (33.15) | |||

| South | 10 817 (37.21) | 2693 (38.65) | 6097 (36.84) | 2027 (36.48) | |||

| Marital status: | |||||||

| Widowed | 2593 (8.92) | 595 (8.54) | 1483 (8.96) | 515 (9.27) | |||

| Divorced, separated, or single | 3670 (12.62) | 889 (12.76) | 2048 (12.38) | 733 (13.19) | |||

| Married | 22 809 (78.46) | 5483 (78.70) | 13 018 (78.66) | 4308 (77.54) | |||

| Years of education: | |||||||

| <1 | 4242 (14.59) | 1042 (14.96) | 2356 (14.24) | 844 (15.19) | |||

| 1-6 | 9618 (33.08) | 2286 (32.81) | 5593 (33.80) | 1739 (31.30) | |||

| 7-12 | 12 182 (41.90) | 2904 (41.68) | 6922 (41.83) | 2356 (42.40) | |||

| >12 | 3030 (10.42) | 735 (10.55) | 1678 (10.14) | 617 (11.11) | |||

| Monthly household income (Chinese Yuan): | |||||||

| 1000-2999 | 2208 (7.59) | 502 (7.21) | 1272 (7.69) | 434 (7.81) | |||

| 3000-4999 | 8715 (29.98) | 2132 (30.60) | 4872 (29.44) | 1711 (30.80) | |||

| 5000-10 000 | 17 369 (59.74) | 4147 (59.52) | 9964 (60.21) | 3258 (58.64) | |||

| >10 000 | 780 (2.68) | 186 (2.67) | 441 (2.66) | 153 (2.75) | |||

| Occupation: | |||||||

| Manual labourer | 12 271 (42.21) | 3026 (43.43) | 6922 (41.83) | 2323 (41.81) | |||

| Office worker | 9076 (31.22) | 2107 (30.24) | 5226 (31.58) | 1743 (31.37) | |||

| Household | 4913 (16.90) | 1146 (16.45) | 2809 (16.97) | 958 (17.24) | |||

| Others | 2812 (9.67) | 688 (9.88) | 1592 (9.62) | 532 (9.58) | |||

| Mean (SD) BMI | 23.30 (4.08) | 23.20 (4.07) | 23.31 (4.08) | 23.36 (4.07) | |||

| Mean (SD) MMSE score | 27.52 (1.30) | 27.51 (1.29) | 27.52 (1.30) | 27.56 (1.31) | |||

| Medical illnesses: | |||||||

| Hypertension | 11 042 (37.98) | 2513 (36.07) | 6323 (38.21) | 2206 (39.70) | |||

| Diabetes | 5823 (20.03) | 1386 (19.89) | 3361 (20.31) | 1076 (19.37) | |||

| Hyperlipidaemia | 7842 (26.97) | 1987 (28.52) | 4463 (26.97) | 1392 (25.05) | |||

| Heart attack | 1913 (6.58) | 448 (6.43) | 1112 (6.72) | 353 (6.35) | |||

| Head injury | 1586 (5.46) | 376 (5.40) | 886 (5.35) | 324 (5.83) | |||

| Depression | 1740 (5.99) | 401 (5.76) | 984 (5.95) | 355 (6.39) | |||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 3018 (10.38) | 765 (10.98) | 1679 (10.15) | 574 (10.33) | |||

| Healthy lifestyle factors: | |||||||

| Never or former smoking | 23 206 (79.82) | 3795 (54.47) | 14 139 (85.44) | 5272 (94.89) | |||

| Never drinking | 11 505 (39.57) | 740 (10.62) | 6998 (42.29) | 3767 (67.80) | |||

| Active cognitive activity | 7151 (24.60) | 120 (1.72) | 3558 (21.50) | 3473 (62.51) | |||

| Regular physical exercise | 6776 (23.31) | 112 (1.61) | 3395 (20.51) | 3269 (58.84) | |||

| Active social contact | 6936 (23.86) | 104 (1.49) | 3542 (21.40) | 3290 (59.22) | |||

| Healthy diet | 14 304 (49.20) | 1001 (14.37) | 8887 (53.70) | 4416 (79.48) | |||

| Number of healthy lifestyle factors: | |||||||

| 0 | 1095 (3.77) | — | — | — | |||

| 1 | 5872 (20.20) | — | — | — | |||

| 2 | 9128 (31.40) | — | — | — | |||

| 3 | 7421 (25.53) | — | — | — | |||

| 4 | 4293 (14.77) | — | — | — | |||

| 5-6 | 1263 (4.34) | — | — | — | |||

| APOE ε4 carriers | 5939 (20.43) | 1602 (22.99) | 3373 (20.38) | 964 (17.35) | |||

| Mean (SD) follow-up period (years) | 6.65 (2.28) | 6.29 (2.15) | 6.60 (2.28) | 7.24 (2.30) | |||

A healthy diet is defined as adherence to the appropriate amounts of at least 7 of the 12 dietary components. Regular physical exercise is defined as spending at least 150 min/week of moderate exercise or 75 min/week of vigorous physical activity. Active cognitive activity is defined as participating in cognitive activities (including writing, reading, playing cards, mah-jong, and gaming) at least twice per week. Active social contact is defined as participating in social activities (including attending meetings or parties, visiting friends or relatives, travelling, and chatting online) at least twice per week. Never drinking and never or former smoking were also regarded as healthy factors. Age, BMI, medical illnesses (including hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, heart attack, cerebrovascular disease, head injury, diabetes, and depression), lifestyle factors (including smoking status, alcohol consumption, diet, physical exercise, cognitive activity, and social contact), and neuropsychological assessments were time-dependent variables. Other demographic information (including sex, place of residence, region, marital status, years of education, monthly household income, and occupation) and the APOE genotype were assessed at baseline only. SD=standard deviation; BMI=body mass index; MMSE=Mini Mental State Examination; APOE=apolipoprotein E.

Lifestyle and memory function in older adults

We used linear mixed effects models to describe the trends in global cognition and memory function and to examine the influence of healthy lifestyle and APOE ε4 status on the annual rate of change in memory function over the 10 year follow-up period. The trajectories in the population with normal cognitive function indicated that, although the overall cognition state remained stable, memory declined continuously over time (supplementary figure 2, supplementary tables 3-4). This memory decline occurred faster in the APOE ε4 carriers than in the APOE ε4 non-carriers (0.002 points/year, 95% confidence interval 0.001 to 0.003, P=0.007) (supplementary figure 2, supplementary table 5).

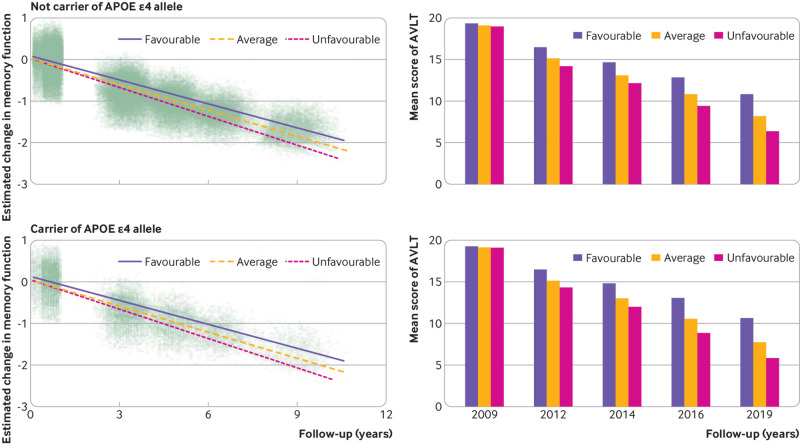

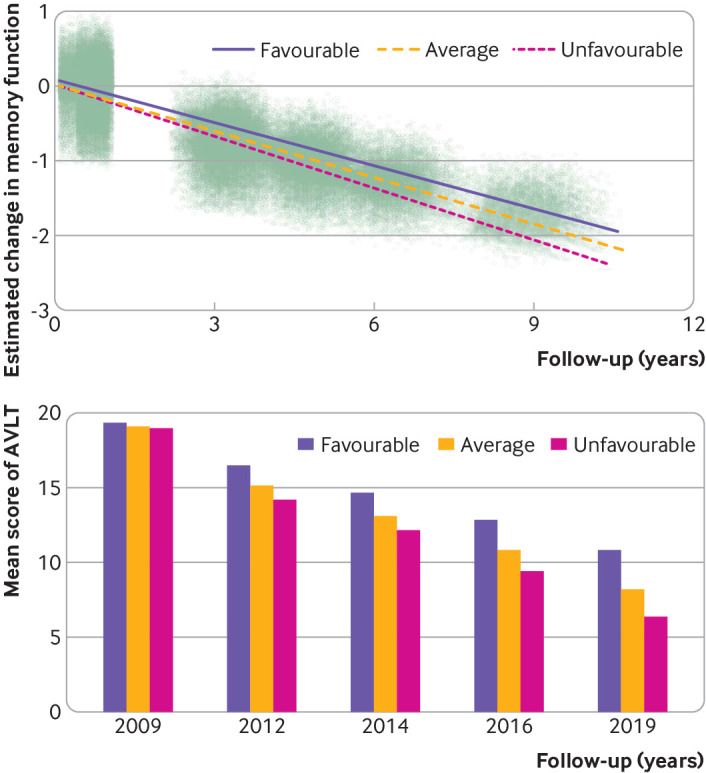

We evaluated the contribution of each binary lifestyle component on memory decline. The results showed that a healthy diet had the strongest effect on memory (β=0.016, 95% confidence interval 0.014 to 0.017, P<0.001), followed by active cognitive activity (β=0.010, 0.008 to 0.012, P<0.001), regular physical exercise (β=0.007, 0.005 to 0.009, P<0.001), active social contact (β=0.004, 0.002 to 0.006, P<0.001), never or former smoking (β=0.004, 0.000 to 0.008, P=0.026), and never drinking (β=0.002, 0.000 to 0.004, P=0.048) (supplementary table 6). Furthermore, we analysed the association between lifestyle groups and memory performance. Our results showed that participants with favourable and average lifestyles had a slower rate of memory decline than did participants with an unfavourable lifestyle (P<0.001) (fig 2). Specifically, the decline in the composite z score was slower by 0.028 points/year (95% confidence interval 0.023 to 0.032) in the favourable group and by 0.016 points/year (0.012 to 0.020) in the average group than in the unfavourable group. Figure 2 (bottom panel) shows that the mean composite Auditory Verbal Learning Test scores continuously declined over the 10 year period; the highest test scores were observed in the favourable group and the lowest in the unfavourable group.

Fig 2.

Longitudinal change in memory among favourable, average, and unfavourable groups in the cognitively normal population. (Top panel) Estimated change in memory function over 10 years, by group. Dots represent individuals’ estimated composite z scores for AVLT. (Bottom panel) Mean composite AVLT z scores of all groups. AVLT=Auditory Verbal Learning Test

Assessing the interaction between lifestyle and age showed a slower rate of age related memory decline in the favourable and average lifestyle groups compared with that in the unfavourable group. Compared with the unfavourable group, the memory score in the favourable lifestyle group was 0.007 (95% confidence interval 0.005 to 0.009, P<0.001) points higher per increased year of age and in the average group was 0.002 (0.000 to 0.003, P=0.033) (supplementary table 7).

Lifestyle and memory function in people with or without APOE ε4

Similar results were obtained in the analyses that were stratified according to the APOE genotype (fig 3). In people who carry APOE ε4 allele and in people who do not, a favourable lifestyle was associated with better memory performance over time compared with average and unfavourable lifestyles (P<0.001). Among people who carry APOE ε4, participants with favourable and average lifestyles exhibited a slower rate of memory decline than did those with an unfavourable lifestyle (0.027 (95% confidence interval 0.023 to 0.031) and 0.014 (0.010 to 0.019) points/year, respectively). Among people who did not carry the APOE ε4 allele, the estimated rates of decline were 0.029 (0.019 to 0.039) points/year slower for participants with favourable lifestyles and 0.019 (0.011 to 0.027) for participants with average lifestyles, compared with participants who had an unfavourable lifestyle. Further analysis showed no significant interaction effect between APOE ε4 status and lifestyle profiles on memory decline (P=0.52).

Fig 3.

Longitudinal change in memory among favourable, average, and unfavourable groups in the APOE ε4 stratified population. Dots in the left panels represent individuals’ estimated composite AVLT z scores. AVLT=Auditory Verbal Learning Test; APOE=apolipoprotein E

Lifestyle and mild cognitive impairment or dementia

Time dependent Cox regression models suggest that, over 10 years of follow-ups, a favourable lifestyle was associated with a lower probability of progression to mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Compared with an unfavourable lifestyle, the hazard ratios were 0.71 (95% confidence interval 0.68 to 0.73) for an average lifestyle and 0.11 (0.10 to 0.12) for a favourable lifestyle. The result was similar when considering the competing risk of death (supplementary table 8). The inverse probability weighting model showed that participants who dropped out of the study did not affect the association between lifestyle and mild cognitive impairment or dementia (supplementary table 9). The APOE stratified analysis showed a similar result with that of the total population (supplementary table 8).

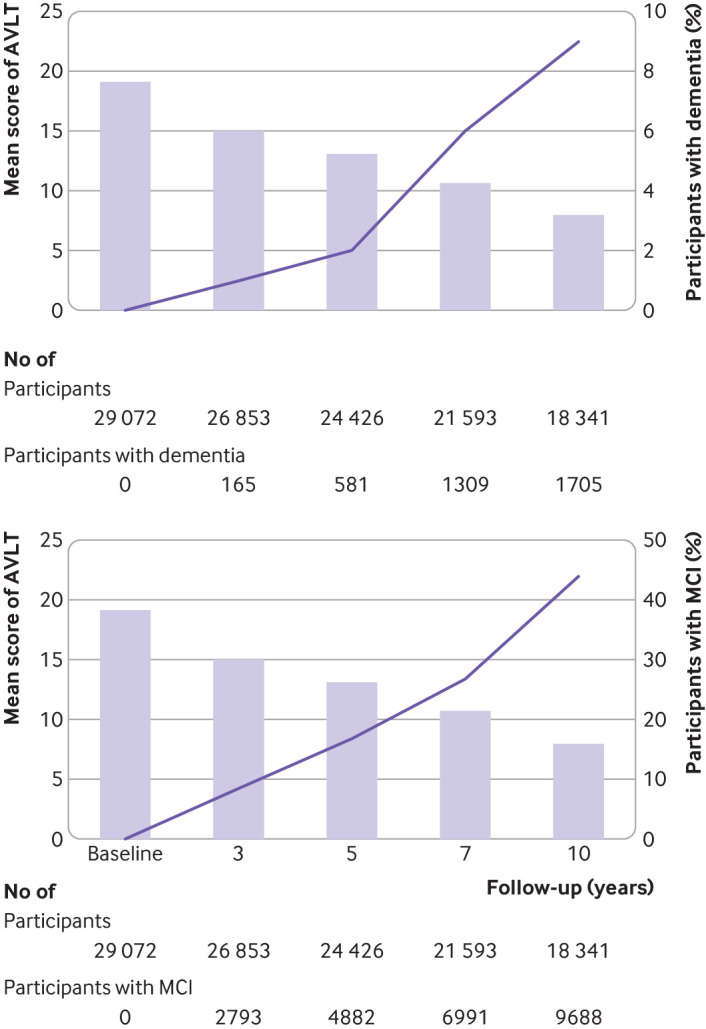

The relations between the mean auditory verbal learning test score and the percentage of participants with dementia or mild cognitive impairment are presented in figure 4. The percentage of participants with dementia or mild cognitive impairment increased as the mean Auditory Verbal Learning Test scores decreased among the older adults in our study.

Fig 4.

Mean AVLT scores and the percentage of participants with dementia (top panel) and mild cognitive impairment (bottom panel) among older adults, at different follow-up periods. The percentages of participants with dementia and mild cognitive impairment increase with a reduction in the mean AVLT scores. AVLT=Auditory Verbal Learning Test; MCI=mild cognitive impairment

Sensitivity analyses

The results of the sensitivity analyses are presented in the supplementary material. The first sensitivity analysis was conducted to test the robustness of the rationale of our grouping methods. When the number of lifestyle factors was considered as a continuous variable in the mixed effects model, two or more healthy lifestyle factors were associated with a slower rate of memory decline than did no healthy factors (supplementary table 10). The results of the analysis investigating the association between lifestyle and memory based on the weighted standardised healthy lifestyle scores showed that participants in the high and intermediate score groups had a slower rate of memory decline by 0.029 (0.025 to 0.033, P<0.001) and 0.017 (0.015 to 0.019, P<0.001) points/year, respectively, compared with participants in the low score group (supplementary tables 11-12). We found that no particular healthy lifestyle factor drove the association between lifestyle and memory (supplementary table 13). Additionally, among participants who did not develop mild cognitive impairment or dementia, did not drop out, and were alive throughout the follow-up period, the association between lifestyle profiles and memory decline remained significant (supplementary tables 14-15). Cross lagged analyses were done to assess the bidirectional, longitudinal associations between memory function and a healthy lifestyle during the 10 year follow-up period. The results supported the absence of a reverse causality between memory decline and healthy lifestyle profiles (supplementary figure 3).

Discussion

This large scale study is the first to our knowledge to estimate the effects of different lifestyle profiles, APOE ε4 status, and their interactions on longitudinal memory trajectories over a 10 year follow-up period. Our results show that a healthy lifestyle was associated with a slower rate of memory decline in cognitively normal older individuals, including in people who are genetically susceptible to memory decline.

Comparison with other studies

This study characterised the longitudinal memory trajectories of the participants with normal global cognition. Of note, the results showed that, although global cognition remained relatively stable, memory declined rapidly as the individual aged. Therefore, focusing on global cognition might lead to overlooking memory problems, especially among people older than 65 years, a third of whom are reported to experience memory complaints.29 Effective strategies for protecting against memory decline might benefit many older individuals. Previous studies have investigated the associations between lifestyle factors and memory loss; however, most have focused on a single lifestyle factor, such as smoking,30 drinking,31 32 diet,33 or physical activities.7 34 Few studies have been conducted to target the combined effects of multiple lifestyle factors on memory decline. Thus, comparison of the contribution of each factor to memory decline has been a challenge.

In this study, we investigated the contribution of each lifestyle factor and their combined effects in a large sample size over an entire decade. We found that diet had the strongest association with memory, followed by cognitive activity, physical exercise, and social contact. Although each lifestyle factor contributed differentially to slowing memory decline, our results showed that participants who maintained more healthy lifestyle factors had a significantly slower memory decline than those with fewer healthy lifestyle factors. This information could be useful in making personal choices that can help to protect against memory decline, and our results provide further evidence that memory loss is potentially modifiable. Although the mechanisms responsible for such changes were not determined in this study, they might include reduced cerebrovascular risk, enhancement of cognitive reserve, inhibition of oxidative stress and inflammation, and promotion of neurotrophic factors.11 13 35 36

Another defining feature of our study is that all participants underwent APOE genotyping. The APOE ε4 allele is reportedly correlated with earlier and more rapidly progressive memory decline,1 37 and the frequency of the ε4 allele dramatically increases to 40% in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.38 People who have the APOE ε4 allele are more likely to exhibit abnormally high Aβ levels in the brain and experience more rapid neurodegeneration and memory loss than people who do not.39 40 41 42 The APOE ε4 allele can also magnify the effects of other risk factors, including physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, and smoking.43 However, most studies that have explored the role of APOE have focused on the associations between lifestyle and global cognition rather than memory.44 45 46 Here, we observed a positive effect of a healthy lifestyle on memory in both carriers of APOE ε4 and non-carriers, and no interaction effect was observed between the APOE genotype and lifestyle profiles over time. These results provide an optimistic outlook, as they suggest that although genetic risk is not modifiable, a combination of more healthy lifestyle factors are associated with a slower rate of memory decline, regardless of the genetic risk.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Although many studies have investigated the relationship between a healthy lifestyle and dementia, few have focused on memory loss, which is a condition that older adults with normal cognitive function can experience and that differs from dementia. This multicentre study with a large sample and a long term follow-up period provided an opportunity to observe the longitudinal trajectories of memory function in older adults with different lifestyles. However, our study also has some limitations. Firstly, the assessments of lifestyle factors were based on self-reports and are, therefore, prone to measurement errors. Secondly, several participants were excluded due to missing data or not returning for follow-up evaluations, which might have led to selection bias. Thirdly, the proportion of individuals with an unhealthy lifestyle might have been underestimated in our study because people with poor health were less likely to have participated in the study. Fourthly, given the nature of our study design, we could not assess whether maintaining a healthy lifestyle had already started influencing memory by the time of enrolment in the study. Fifthly, we evaluated memory using a single neuropsychological test that does not comprehensively reflect overall memory function. However, the Auditory Verbal Learning Test is an effective instrument for memory assessment, and we used a composite score based on four Auditory Verbal Learning Test subscales to represent memory conditions to the greatest extent possible. Sixthly, as participants might become familiar with repeated cognitive testing, a learning effect could have influenced the results, although, we considered that possibility in the design of the statistical analysis method. Finally, we studied memory decline solely among older adults; however, memory problems commonly affect young individuals as well. Thus, further studies should be conducted to facilitate a more extensive investigation into the effects of a healthy lifestyle on memory decline across the lifespan. This approach would help to elucidate the crucial age window during which a healthy lifestyle can exert the most favourable effect.

Conclusions

The results of this study provide strong evidence that adherence to a healthy lifestyle with a combination of positive behaviours, such as never or former smoking, never drinking, a healthy diet, regular physical exercise, and active cognitive activity and social contact, is associated with a slower rate of memory decline. Importantly, our study provides evidence that these effects also include individuals with the APOE ε4 allele. This study might offer important information to protect older adults against memory decline.

What is already known on this topic

Memory is a fundamental function of daily life that continuously declines with increasing age

Evidence from cohort studies is insufficient to evaluate the effect of healthy lifestyle on memory trajectory

Given the multifactorial biological cause of memory decline, a combination of healthy lifestyle factors might be necessary for an optimal effect, even for people who are genetically susceptible to memory decline

What this study adds

A combination of positive healthy behaviours is associated with a slower rate of memory decline in cognitively normal older adults, including in people with the apolipoprotein E ε4 allele

These results might offer important information for public health initiatives to protect older adults against memory decline

Web extra.

Extra material supplied by authors

Web appendix: Supplementary material

Contributors: JJ and TZ are joint first authors. JJ designed and supervised the study. JJ, FangyuL, and TZ performed the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. JJ, SG, and JC critically revised the manuscript. JJ, SG, and JC obtained funding for the study. All authors have provided intellectual content and revised the manuscript. JJ is the guarantor. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: This study was supported by the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81530036); the National Key Scientific Instrument and Equipment Development Project (31627803); the Key Project of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U20A20354); Beijing Scholars Program; Beijing Brain Initiative from Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (Z201100005520016, Z201100005520017, Z161100000216137); CHINACANADA Joint Initiative on Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders (81261120571); Mission Program of Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals (SML20150801); National Natural Science Foundation of China (30370494, 30410303095, 30470615); The National Science and Technology Foundation of China (2004BA714B06-1, 2003CB517102, 2006CB500700, 2006BAI02B01, 2011CB504101, 2011ZX09307-001-03); Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7071004); Major project of Beijing Municipal Science and Technology Commission (D111107003111009); and Sailing Plan of Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals (ZY201301). The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/disclosure-of-interest/ and declare: support from the Xuanwu hospital of Capital Medical University for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Dissemination to participants and related patient and public communities: The results of the research will be disseminated to the public through broadcasts, newspaper, television, social media, conference, and popular science articles.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Ethical approval

The Xuanwu hospital of Capital Medical University and other participating institutes approved this study. All participants provided informed consent to be eligible to participate in this study.

Data availability statement

No additional data available.

References

- 1. Caselli RJ, Dueck AC, Osborne D, et al. Longitudinal modeling of age-related memory decline and the APOE epsilon4 effect. N Engl J Med 2009;361:255-63. 10.1056/NEJMoa0809437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jonker C, Geerlings MI, Schmand B. Are memory complaints predictive for dementia? A review of clinical and population-based studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000;15:983-91. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mitchell AJ, Beaumont H, Ferguson D, Yadegarfar M, Stubbs B. Risk of dementia and mild cognitive impairment in older people with subjective memory complaints: meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2014;130:439-51. 10.1111/acps.12336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Comijs HC, Deeg DJ, Dik MG, Twisk JW, Jonker C. Memory complaints; the association with psycho-affective and health problems and the role of personality characteristics. A 6-year follow-up study. J Affect Disord 2002;72:157-65. 10.1016/S0165-0327(01)00453-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zahodne LB, Wall MM, Schupf N, et al. Late-life memory trajectories in relation to incident dementia and regional brain atrophy. J Neurol 2015;262:2484-90. 10.1007/s00415-015-7871-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Rosenich E, Bransby L, Yassi N, et al. Differential effects of APOE and modifiable risk factors on hippocampal volume loss and memory decline in Aβ- and Aβ+ older adults. Neurology 2022;98:e1704-15. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000200118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Steffl M, Jandova T, Dadova K, et al. Demographic and Lifestyle Factors and Memory in European Older People. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:4727. 10.3390/ijerph16234727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sabia S, Nabi H, Kivimaki M, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG, Singh-Manoux A. Health behaviors from early to late midlife as predictors of cognitive function: The Whitehall II study. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170:428-37. 10.1093/aje/kwp161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kesse-Guyot E, Andreeva VA, Lassale C, Hercberg S, Galan P. Clustering of midlife lifestyle behaviors and subsequent cognitive function: a longitudinal study. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e170-7. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mueller KD, Norton D, Koscik RL, et al. Self-reported health behaviors and longitudinal cognitive performance in late middle age: Results from the Wisconsin Registry for Alzheimer’s Prevention. PLoS One 2020;15:e0221985. 10.1371/journal.pone.0221985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee Y, Kim J, Back JH. The influence of multiple lifestyle behaviors on cognitive function in older persons living in the community. Prev Med 2009;48:86-90. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Visser M, Wijnhoven HAH, Comijs HC, Thomése FGCF, Twisk JWR, Deeg DJH. A Healthy Lifestyle in Old Age and Prospective Change in Four Domains of Functioning. J Aging Health 2019;31:1297-314. 10.1177/0898264318774430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flöel A, Witte AV, Lohmann H, et al. Lifestyle and memory in the elderly. Neuroepidemiology 2008;31:39-47. 10.1159/000137378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. 5.2 Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Manual of Screeners for Dementia 2020:51.

- 15. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association Press, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Petersen RC. Mild cognitive impairment as a diagnostic entity. J Intern Med 2004;256:183-94. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2004.01388.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jia J, Wang F, Wei C, et al. The prevalence of dementia in urban and rural areas of China. Alzheimers Dement 2014;10:1-9. 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA 2018;320:2020-8. 10.1001/jama.2018.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Choi D, Choi S, Park SM. Effect of smoking cessation on the risk of dementia: a longitudinal study. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2018;5:1192-9. 10.1002/acn3.633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu Z, Song C, Suo C, Fan H, Zhang T, Jin L, Chen X. Alcohol consumption and hepatocellular carcinoma: novel insights from a prospective cohort study and nonlinear Mendelian randomization analysis. BMC Med 2022;28;413. 10.1186/s12916-022-02622-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators . Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2018;392:1015-35. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. van Dam RM, Li T, Spiegelman D, Franco OH, Hu FB. Combined impact of lifestyle factors on mortality: prospective cohort study in US women. BMJ 2008;337:a1440. 10.1136/bmj.a1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, et al. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. N Engl J Med 2001;345:790-7. 10.1056/NEJMoa010492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stampfer MJ, Hu FB, Manson JE, Rimm EB, Willett WC. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease in women through diet and lifestyle. N Engl J Med 2000;343:16-22. 10.1056/NEJM200007063430103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dhana K, Franco OH, Ritz EM, et al. Healthy lifestyle and life expectancy with and without Alzheimer’s dementia: population based cohort study. BMJ 2022;377:e068390. 10.1136/bmj-2021-068390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chinese Nutrition Society . Chinese dietary guideline (2007). 1st ed. the Tibet People's Publishing House, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lopez E. Validity study of the World Health Organization/University of California at Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test. Pepperdine University, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jiao L, Mitrou PN, Reedy J, et al. A combined healthy lifestyle score and risk of pancreatic cancer in a large cohort study. Arch Intern Med 2009;169:764-70. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Arvanitakis Z, Leurgans SE, Fleischman DA, et al. Memory complaints, dementia, and neuropathology in older blacks and whites. Ann Neurol 2018;83:718-29. 10.1002/ana.25189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lewis CR, Talboom JS, De Both MD, et al. Smoking is associated with impaired verbal learning and memory performance in women more than men. Sci Rep 2021;11:10248. 10.1038/s41598-021-88923-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rao R, Creese B, Aarsland D, et al. Risky drinking and cognitive impairment in community residents aged 50 and over. Aging Ment Health 2022;26:2432-9. 10.1080/13607863.2021.2000938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Woods AJ, Porges EC, Bryant VE, et al. Current Heavy Alcohol Consumption is Associated with Greater Cognitive Impairment in Older Adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2016;40:2435-44. 10.1111/acer.13211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zhu N, Jacobs DR, Meyer KA, et al. Cognitive function in a middle aged cohort is related to higher quality dietary pattern 5 and 25 years earlier: the CARDIA study. J Nutr Health Aging 2015;19:33-8. 10.1007/s12603-014-0491-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Folley S, Zhou A, Llewellyn DJ, Hyppönen E. Physical activity, APOE genotype, and cognitive decline: exploring gene-environment interactions in the UK Biobank. J Alzheimers Dis 2019;71:741-50. 10.3233/JAD-181132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dhana K, Evans DA, Rajan KB, Bennett DA, Morris MC. Healthy lifestyle and the risk of Alzheimer dementia: Findings from 2 longitudinal studies. Neurology 2020;95:e374-83. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Clare L, Wu YT, Teale JC, et al. CFAS-Wales study team . Potentially modifiable lifestyle factors, cognitive reserve, and cognitive function in later life: A cross-sectional study. PLoS Med 2017;14:e1002259. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lim YY, Williamson R, Laws SM, et al. AIBL Research Group . Effect of APOE Genotype on Amyloid Deposition, Brain Volume, and Memory in Cognitively Normal Older Individuals. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;58:1293-302. 10.3233/JAD-170072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Farrer LA, Cupples LA, Haines JL, et al. APOE and Alzheimer Disease Meta Analysis Consortium . Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. JAMA 1997;278:1349-56. 10.1001/jama.1997.03550160069041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Llibre-Guerra JJ, Li J, Qian Y, et al. Apolipoprotein E (APOE) genotype, dementia, and memory performance among Caribbean Hispanic versus US populations. Alzheimers Dement 2022; 10.1002/alz.12699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hostage CA, Choudhury KR, Murali Doraiswamy P, Petrella JR, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Mapping the effect of the apolipoprotein E genotype on 4-year atrophy rates in an Alzheimer disease-related brain network. Radiology 2014;271:211-9. 10.1148/radiol.13131041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chiang GC, Insel PS, Tosun D, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative . Impact of apolipoprotein E4-cerebrospinal fluid β-amyloid interaction on hippocampal volume loss over 1 year in mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement 2011;7:514-20. 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ossenkoppele R, Jansen WJ, Rabinovici GD, et al. Amyloid PET Study Group . Prevalence of amyloid PET positivity in dementia syndromes: a meta-analysis. JAMA 2015;313:1939-49. 10.1001/jama.2015.4669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kivipelto M, Mangialasche F, Ngandu T. Lifestyle interventions to prevent cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 2018;14:653-66. 10.1038/s41582-018-0070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Dhana K, Barnes LL, Liu X, et al. Genetic risk, adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and cognitive decline in African Americans and European Americans. Alzheimers Dement 2022;18:572-80. 10.1002/alz.12435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jin X, He W, Zhang Y, et al. Association of APOE ε4 genotype and lifestyle with cognitive function among Chinese adults aged 80 years and older: a cross-sectional study. PLoS Med 2021;18:e1003597. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Dhana K, Aggarwal NT, Rajan KB, Barnes LL, Evans DA, Morris MC. Impact of the apolipoprotein E ε4 allele on the relationship between healthy lifestyle and cognitive decline: a population-based study. Am J Epidemiol 2021;190:1225-33. 10.1093/aje/kwab033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Web appendix: Supplementary material

Data Availability Statement

No additional data available.