Abstract

Rationale

Care of emergency department (ED) patients with pneumonia can be challenging. Clinical decision support may decrease unnecessary variation and improve care.

Objectives

To report patient outcomes and processes of care after deployment of electronic pneumonia clinical decision support (ePNa): a comprehensive, open loop, real-time clinical decision support embedded within the electronic health record.

Methods

We conducted a pragmatic, stepped-wedge, cluster-controlled trial with deployment at 2-month intervals in 16 community hospitals. ePNa extracts real-time and historical data to guide diagnosis, risk stratification, microbiological studies, site of care, and antibiotic therapy. We included all adult ED patients with pneumonia over the course of 3 years identified by International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision discharge coding confirmed by chest imaging.

Measurements and Main Results

The median age of the 6,848 patients was 67 years (interquartile range, 50–79), and 48% were female; 64.8% were hospital admitted. Unadjusted mortality was 8.6% before and 4.8% after deployment. A mixed effects logistic regression model adjusting for severity of illness with hospital cluster as the random effect showed an adjusted odds ratio of 0.62 (0.49–0.79; P < 0.001) for 30-day all-cause mortality after deployment. Lower mortality was consistent across hospital clusters. ePNa-concordant antibiotic prescribing increased from 83.5% to 90.2% (P < 0.001). The mean time from ED admission to first antibiotic was 159.4 (156.9–161.9) minutes at baseline and 150.9 (144.1–157.8) minutes after deployment (P < 0.001). Outpatient disposition from the ED increased from 29.2% to 46.9%, whereas 7-day secondary hospital admission was unchanged (5.2% vs. 6.1%). ePNa was used by ED clinicians in 67% of eligible patients.

Conclusions

ePNa deployment was associated with improved processes of care and lower mortality.

Clinical trial registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03358342).

Keywords: pneumonia, emergency department, clinical decision support, mortality, antibiotic use

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Care of emergency department patients with pneumonia can be challenging. Treatment recommendations have been published in American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines, but adoption in clinical practice is challenging. In this study we report improved processes of care and 38% lower severity-adjusted 30-day all-cause mortality after deployment of electronic open loop clinical decision support embedded within the electronic health record (ePNa). ePNa extracts both real-time and historical data to guide diagnosis, risk stratification, microbiological studies, site of care, and antibiotic therapy. ePNa requires minimal input from clinicians and gathers/displays data to aid decision making and smoothen transitions of care.

What This Study Adds to the Field

After ePNa deployment, there was a 17% increase in outpatient disposition and decreased ICU admission without safety concerns. Antibiotic administration was earlier and more aligned with guideline recommendations. Vancomycin begun empirically was mostly discontinued after hospital admission. These findings replicate the lower mortality observed in our earlier prospective, quasi-experimental, controlled trial and validate the pneumonia treatment guidelines on which ePNa logic is based. We are developing a SMART (Substitutable Medical Applications and Reusable Technologies) on FHIR (Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources) version of ePNa interoperable among different electronic health records to allow validation outside Intermountain Healthcare.

Pneumonia is the eighth leading cause of death in the United States, with more than 6 million cases annually, 1 million hospitalizations, and more than $7 billion spent for inpatient treatment costs alone (1, 2). When a patient is suspected of having pneumonia, clinicians must 1) assess symptoms and clinical findings to determine whether pneumonia is likely compared with other diagnoses; 2) identify the most appropriate treatment site (home, hospital, or ICU); and 3) determine whether causative bacteria may be resistant to commonly prescribed antibiotics. These decisions are critical for patient safety, but, given their complexity and the fundamental limitations of human decision making, care often deviates from best practice. Studies have consistently demonstrated variability in hospital admission rates between different institutions and between physicians in a single emergency department (ED) (3–5). Electronic clinical decision support may decrease unnecessary variation and improve care (6).

Well-established scientific guidelines help clinicians diagnose and treat pneumonia, but they are underused (7). The 2007 and 2019 American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America pneumonia guidelines form the knowledge base within our electronic pneumonia clinical decision support tool (ePNa) (8, 9). ePNa extracts real-time and historical data from the electronic health record (EHR) to guide diagnosis, risk stratification, ordering of microbiological studies, site-of-care decisions, and treatment. A detailed description of ePNa function is provided in Appendix E2 in the online supplement and has been published previously (10).

ePNa was first deployed in four hospital EDs in 2011. A quasi-experimental study demonstrated lower all-cause 30-day mortality among patients with community-acquired pneumonia compared with three nearby usual-care hospitals (odds ratio [OR], 0.53; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.28–0.99) (11). Patients with severe illness were more likely to be admitted to ePNa hospitals for treatment and to receive guideline-recommended antibiotics compared with nearby usual care hospitals.

Hypothesizing that ePNa would improve mortality (primary outcome) and processes of care (secondary outcomes), we deployed ePNa across all remaining adult Intermountain Healthcare community hospitals ranging from 20 to 310 inpatient beds. Intermountain is an integrated nonprofit healthcare system with hospital EDs staffed by family practice physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and board-certified emergency medicine physicians. Annual ED volumes range from 5,090 to 60,000 patients with a staff of 5–37 clinicians at each hospital. We staged implementation with ED leadership support, active clinician engagement in tool development and deployment, educational meetings, academic detailing, and ongoing technical support. Local champions taught and encouraged use of ePNa, and study authors conducted audit and feedback at regular intervals. We have previously published the implementation science methods and qualitative results (10, 12).

Here we report 30-day all-cause mortality and processes of care in ED patients with pneumonia after deployment of ePNa in a pragmatic, stepped-wedge, cluster-controlled trial (13). Some of the results of this study have been reported previously (14).

Methods

Study Design

See Appendixes E1 and E3 for further details of the study design. We deployed ePNa into six geographic clusters of 16 Intermountain hospital EDs at 2-month intervals between December 2017 and November 2018 according to a prespecified plan (www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT03358342) (Figure 1). We chose the stepped-wedge, cluster-controlled design to deploy ePNa because our prior study demonstrated decreased mortality (11), and implementation requires intensive education, monitoring, and feedback on ePNa use facilitated by focusing on a few hospitals at a time (13). We grouped hospitals into six clusters by geographic proximity to each other and need to encompass ED, hospital, and critical care clinicians providing care at more than one hospital. Cluster order enacted our previous commitment to prioritize usual care hospitals from the prior study because of decreased mortality. Deployment had been delayed because Intermountain’s legacy EHR had differences that prevented ePNa from functioning beyond where it was first deployed. We began deployment after Intermountain had transitioned to the Cerner EHR and ePNa was reprogrammed. The baseline period lasted 18 months before deployment in each cluster beginning June 2016. We excluded patients with pneumonia for 2 months after deployment to allow uptake of ePNa into clinical practice. Data were collected until June 2019, 18 months after the first cluster deployment.

Figure 1.

Stepwise deployment into six hospital clusters at 2-month intervals. The predeployment period was 18 months before deployment in each cluster. The postdeployment period began after the 2-month washout period and ended in June 2019. The number of pneumonia patients per cluster per period is contained within the bars. Three larger urban hospitals with ICUs staffed by critical care physicians are included in clusters 1–3; five medium-sized hospitals in smaller cities and suburbs with ICUs staffed by hospitalists in consultation with telemedicine critical care physicians are included in clusters 2–5; eight smaller rural hospitals whose family practice clinicians transfer patients to hospitals with ICUs in consultation with telemedicine critical care physicians are included in clusters 2–6.

Patient Identification and Data

We included all ED patients ⩾18 years old with radiographic pneumonia on ED chest imaging plus discharge International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10), pneumonia codes (15, 16). Severely ill ED patients transferred from smaller Intermountain hospitals to regional referral centers were attributed to their initial cluster.

We gathered data through queries of Intermountain’s enterprise data warehouse. Mortality data were collected from Intermountain medical records and death certificate data from state departments of health. Missing data (most commonly ED mental status and oxygen supplementation during measurement of oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry) were identified by manual chart review; missing data ultimately were <1%. The Cerner EHR does not reliably record ePNa use after the current encounter. Percentage ePNa use was therefore calculated from physician review (N.C.D., C.G.V., J.R.C., N.J., and M.W.) of individual ED clinician notes identified by pneumonia ICD-10 codes and ED chest imaging, as previously described (12).

The Intermountain Institutional Review Board approved ePNa deployment and data collection with waiver of individual patient consent (1050688). Intermountain’s Office of Research provided a supporting grant but had no role in study design, conduct, or analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Because ePNa use is not recorded in the Cerner EHR and exact time of implementation in each cluster varied by provider meeting schedules, we analyzed the clusters using the intention-to-treat principle by planned deployment time. We had estimated a priori that approximately 9,370 subjects would be needed to measure a 2% absolute decrease in 30-day mortality with 80% power (see Appendix E3 for details). Our primary analysis used a mixed-effects model to evaluate the relationship between ePNa deployment and severity-adjusted 30-day mortality. To account for secular trends, we included scheduled implementation time as a fixed effect. To account for regional differences in practice patterns and patient characteristics, cluster was analyzed as both a random and a fixed effect using validated severity adjustors.

To thoroughly explore the possible influence of secular trends on mortality, we conducted several post hoc sensitivity analyses. We first truncated data to 12 months before and 12 months after the washout period at each cluster and then further truncated to 6 months before and after. To further differentiate secular trends from intervention-specific effects, we conducted an additional sensitivity analysis to compare predicted (risk-adjusted) mortality with observed mortality before and after implementation. This was performed using a mixed-effects model with factors influencing mortality (see Table 2 legend), but excluding the pre- and postimplementation variable, to estimate predicted mortality for each patient and compare with the actual observed outcomes. We also explored using segmented regression to conduct a post hoc interrupted time-series analysis, but the number of events was insufficient for model accuracy (see Appendix E4 for details).

Table 2.

Mixed-Effects Logistic Regression Model for 30-Day All-Cause Mortality Using Intention-to-Treat Principles, Adjusted for Severity of Illness with Cluster as the Random Effect

| Variable | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.00 (0.00–0.01) | <0.001 |

| Postdeployment | 0.62 (0.49–0.79) | <0.001 |

| Season* | 1.16 (0.94–1.44) | 0.171 |

| Age, yr | 1.03 (1.02–1.03) | <0.001 |

| Female | 0.90 (0.74–1.10) | 0.288 |

| eCURB | 1.05 (1.04–1.06) | <0.001 |

| PaO2/FiO2, standardized | 0.67 (0.60–0.75) | <0.001 |

| HCAP† | 2.08 (1.68–2.57) | <0.001 |

| Pleural effusion | 2.23 (1.49–3.35) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 0.90 (0.72–1.11) | 0.304 |

| Chronic renal disease | 0.91 (0.73–1.14) | 0.415 |

| Chronic liver disease | 1.59 (1.27–1.99) | <0.001 |

| Chronic heart disease | 1.54 (1.23–1.92) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 0.97 (0.78–1.21) | 0.811 |

Definition of abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; eCURB = electronically calculated confusion, blood urea nitrogen, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, 65 years of age and older; HCAP = healthcare-associated pneumonia.

November 1 to June 1.

Healthcare-associated pneumonia used as a severity of illness adjustor.

Patient disposition from the ED was compared with what ePNa would have recommended (regardless of whether ePNa was actually used). Change in disposition after ePNa deployment was adjusted for illness severity using the same mixed-methods model as that used for mortality. Hospital length of stay included only admitted patients who survived to hospital discharge. Seven-day secondary hospital admission included patients with initial outpatient disposition who were admitted to any Intermountain hospital for any reason within 7 days after the first ED visit. R version 4.1.0 was used for these analyses (17).

Results

Of 7,641 patients with discharge ICD-10 pneumonia codes confirmed by ED chest imaging consistent with radiographic pneumonia, we excluded 342 patients from washout periods, 37 who died in the ED or were directly transferred to hospice, 1 patient with missing mortality information, and 413 transferred to non-Intermountain hospitals for admission where subsequent data were not available, leaving 6,848 patients, of whom 4,536 were before and 2,312 were after deployment. Figure 1 illustrates the stepped-wedge study timeline and number of patients included in each cluster. The median age was 67 years (interquartile range, 50–79); 48% were female; 94% were White, including 7% who were of Hispanic origin; and 64.8% were initially admitted to the hospital. Patient demographics are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Variable | Before Deployment | After Deployment | P Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 4,536 | 2,312 | |

| Age, yr | 68 (53–79) | 63 (45–77) | <0.001 |

| Female | 2,175 (48%) | 1,146 (50%) | 0.21 |

| Race, % White* | 4,293 (95%) | 2,164 (94%) | 0.088 |

| eCURB†, mean | 7 ± 10% | 4 ± 7% | <0.001 |

| PaO2/FiO2, standardized | 314 (252–362) | 319 (271–390) | 0.002 |

| sCAP‡ | 1 (1–2) | 1 (0–2) | <0.001 |

| HCAP§ | 939 (21%) | 507 (22%) | 0.25 |

| Pleural effusion | 3% (128) | 5% (123) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1,628 (36%) | 736 (32%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic renal disease | 1,386 (31%) | 541 (23%) | <0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 943 (21%) | 471 (20%) | 0.71 |

| Chronic heart disease | 1,568 (35%) | 626 (27%) | <0.001 |

| COPD | 1,258 (28%) | 545 (24%) | <0.001 |

| No comorbid illnesses | 1,433 (32%) | 894 (39%) | <0.001 |

| Unadjusted mortality | 389 (8.58%) | 112 (4.84%) | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay, d | 3.2 (2.1–5.3) | 2.6 (1.8–4.0) | <0.001 |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; eCURB = electronically calculated confusion, blood urea nitrogen, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, 65 years of age and older; HCAP = healthcare-associated pneumonia; sCAP = severe community-acquired pneumonia.

P values for categorical variables were obtained using Fisher’s exact test. P values for continuous variables were obtained using t test.

White race includes 7% Hispanic.

Electronically calculated percentage predicted 30-day all-cause mortality (16).

American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases of America minor severe community-acquired pneumonia criteria, an ordinal scale of nine criteria (7, 8).

Healthcare-associated pneumonia criteria used as a severity adjustor.

Mortality

Observed 30-day all-cause mortality, including both outpatients and inpatients, was 8.6% before deployment versus 4.8% after deployment of ePNa. A mixed effects logistic regression model adjusting for severity of illness with cluster as the random effect demonstrated lower mortality after deployment with an OR of 0.62 (95% CI, 0.49–0.79; P < 0.001) (Table 2). This estimate was unchanged when modeling cluster as a fixed effect (OR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.49–0.79; P < 0.001), reflecting consistent changes in mortality among the six clusters. Between-cluster variance was 0.63 (SD, 0.79), the adjusted intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.17, and the conditional intraclass correlation coefficient was 0.13.

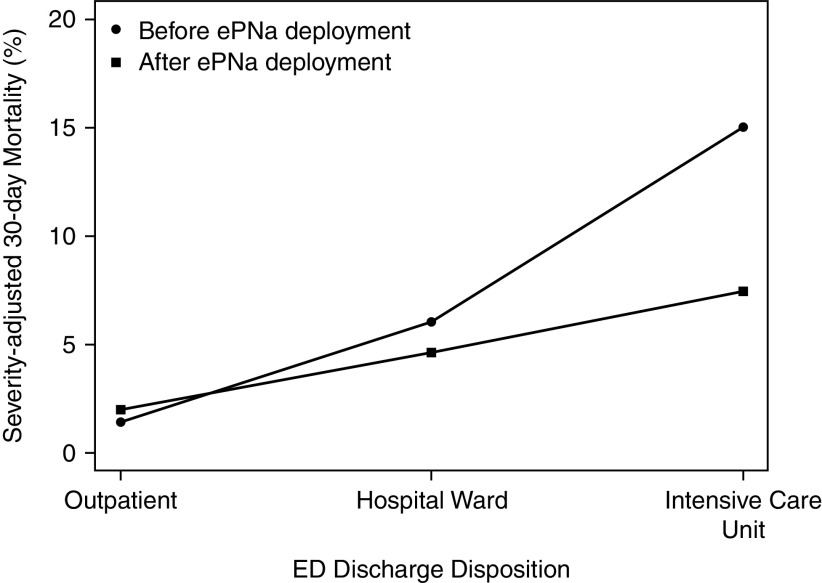

Results of sensitivity analyses to evaluate for a possible secular trend in mortality by limiting enrollment were consistent with the primary analysis. When truncated to 12 months before and 12 months after the washout period at each cluster, the OR was 0.66 (95% CI, 0.51–0.87; P = 0.003); when truncated to 6 months, the OR was 0.64 (95% CI, 0.44–0.93; P = 0.02). The addition of hospital type to the primary analysis as a random effect resulted in minor changes in estimates and P values but no changes to the ultimate conclusions (see Appendix E4 for details). In the mixed effects sensitivity model, observed (actual) mortality decreased by 3.8% after ePNa deployment (8.6% before deployment vs. 4.8% after), which was greater than the 1.4% difference in predicted (adjusted) mortality (7.8% before deployment vs. 6.4% after). Mortality reduction was greatest in patients directly admitted to ICUs from the ED (OR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.14–0.77; P = 0.01) compared with those admitted to the medical floor (OR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.25–1.1; P = 0.09) and with outpatient disposition (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Severity-adjusted mortality by site of care after emergency department (ED) discharge. Severity-adjusted mortality before ePNa deployment versus after ePNa deployment was 1.4% versus 2.0% for patients with outpatient disposition, 6.0% versus 4.6% for hospital ward disposition, and 15.0% versus 7.4% for ICU disposition. ePNa = electronic pneumonia clinical decision support.

Antibiotic Use

Among patients admitted to the hospital, guideline-/ePNa-concordant antibiotic prescribing increased in the 8 hours after ED arrival from 79.5% to 87.9%, after severity adjustment (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.54–2.30; P < 0.001). Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics (active against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus [MRSA] and/or Pseudomonas aeruginosa) within 8 hours was not significantly different, with 27% before and 25% after ePNa deployment, after severity adjustment (OR, 0.88; 95% CI, 0.75–1.04; P = 0.14). However, administration of antibiotics active against MRSA (mostly vancomycin) decreased from 13% before deployment to 10% after deployment, from 15% to 8% between 8 and 72 hours, and from 6% to 3% after 72 hours (all P < 0.001). Mean time from ED admission to first antibiotic was 159.4 (95% CI, 156.9–161.9) minutes at baseline and 150.9 (95% CI, 144.1–157.8) after ePNa deployment (P < 0.001).

Disposition

Overall outpatient disposition for treatment of pneumonia from the ED increased from 29.2% before ePNa to 46.9%; a similar increase was observed in patients for whom ePNa recommended outpatient care (49.2% before deployment vs. 66.6% after). Reciprocally, hospital ward disposition (57.3% vs. 47%) and ICU disposition (13.5% vs. 6.1%) both decreased after ePNa deployment. These changes in disposition after ePNa deployment were significantly different after severity adjustment (P = 0.036). Despite increased outpatient disposition, neither severity-adjusted 7-day secondary hospital admission (69 patients, 5.2%, vs. 66 patients, 6.1%; OR, 1.20; 95% CI, 0.84–1.71; P = 0.31) nor severity-adjusted 30-day mortality was significantly different before versus after ePNa deployment (1.4% vs. 2.0%; OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 0.72–2.72; P = 0.32).

Outpatient disposition also increased (from 15.1% to 24.2% after ePNa deployment) in patients recommended for hospital ward admission by ePNa. Both 30-day mortality (7.2%) and 7-day secondary hospital admission (7.7%) were higher among patients recommended for hospital ward admission but discharged home from the ED compared with patients recommended by ePNa for outpatient care (0.46% and 5.7%, respectively). To understand this result, ED clinician notes for 52 (25%) randomly selected patients were individually reviewed by N.C.D. ePNa was less commonly used than overall, in only 10 (19%) of 52 patients. The most common indication for admission in this subset of patients was hypoxemia in 34 patients (65%), of whom 22 (65%) were prescribed or continued home oxygen. Electronic CURB (confusion, blood urea nitrogen, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, 65 years of age and older) predicted mortality was ⩾5% (a criterion for hospital admission used by ePNa) in 11 patients (21%), mostly older patients with elevated blood urea nitrogen. Pleural effusions were present in 7 patients (13%), and 20 patients (38%) reportedly declined their clinician’s recommendation of hospital admission.

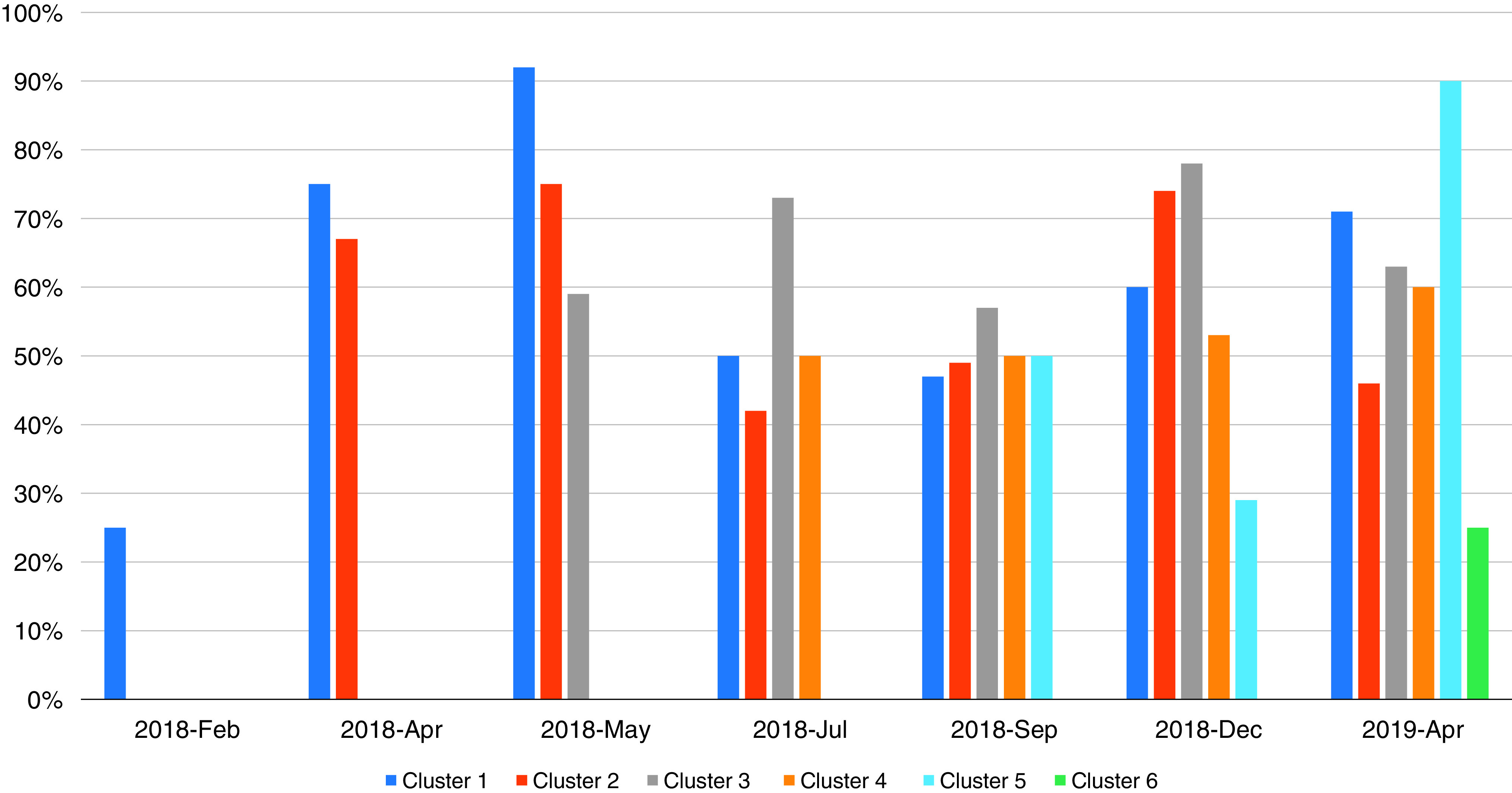

Use

Overall, ePNa was used by the ED clinician in 67% of eligible patients with pneumonia after deployment. Use was 69% in the 6 larger hospitals but 36% in the 10 smaller rural hospitals. Figure 3 shows ePNa use by cluster over time after the washout period.

Figure 3.

Electronic pneumonia clinical decision support use based on individual case reviews by cluster at intervals after the washout periods.

Discussion

Deployment of ePNa real-time, comprehensive, electronic clinical decision support across 16 community hospitals in a pragmatic, stepped-wedge, cluster-controlled trial was associated with a 38% relative reduction in 30-day all-cause mortality among ED patients with pneumonia. The largest reduction in mortality associated with ePNa deployment was observed among patients directly admitted from EDs to ICUs. Guideline-concordant antibiotic therapy increased and was administered sooner in the ED. A significantly higher percentage of ED patients with pneumonia were safely triaged to pneumonia management at home without significantly worsening 7-day secondary hospital admission readmission or mortality. This represents an important reduction in unnecessary healthcare use and cost savings while improving outcomes overall among ED patients. An intriguing possibility is that lower-risk ED patients with pneumonia might do better at home than on hospital wards and on hospital wards than in ICUs because of less nosocomial impact.

These results were achieved using intention-to-treat principles despite incomplete use of ePNa by ED clinicians, which was explored in prior work published by our group (10, 12, 18). These findings replicate the lower mortality observed in our earlier prospective, quasi-experimental, controlled trial in seven Intermountain hospitals (see the introductory section) (11). They also are a real-world validation of the 2007 and 2019 American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America pneumonia treatment guidelines on which ePNa logic is based. Although the 2019 guideline was not published until after study completion, N.C.D.’s guideline committee membership allowed adoption of recommendations before ePNa deployment.

ED disposition to home also significantly increased in patients recommended for hospital admission, but this subgroup had higher mortality than patients recommended by ePNa for outpatient disposition. Case review revealed oxygen prescribing for home use in selected patients whom ePNa recommended for hospital admission because of hypoxemia. Prior studies have shown that hypoxemic patients with pneumonia have increased risk of mortality (19, 20), but no randomized trial of home oxygen versus hospital admission has been published. Patients in this subgroup who declined their clinician’s recommendation of hospital admission might benefit from future plans to provide patient-centered severity of illness estimates calculated by ePNa.

The absolute difference in antibiotic prescribing after ePNa deployment was small, perhaps because Intermountain has had a paper-based guideline for community-acquired pneumonia in place for 20 years, yielding relatively high guideline-concordant antibiotic use at baseline compared with published reports (21–23). We hypothesize that ePNa guidance (Drug Resistance in Pneumonia [DRIP] score; see Appendix E2) for prescribing broad-spectrum antibiotics may have targeted patients at risk for drug-resistant pathogens. MRSA nasal swab testing recommended by ePNa for patients receiving vancomycin led to its discontinuation after hospital admission per pharmacy protocol (24). Some of the observed residual broad-spectrum antibiotic use is attributable to early prescribing for sepsis before chest imaging, as well as antibiotic allergy history.

Year-to-year variation in pneumonia severity reflects differences in circulating respiratory viruses, bacterial serotypes, weather, and degrees of air pollution. Mean age was 5 years younger after deployment despite inclusion and exclusion criteria being unchanged. Utah has the fastest-growing (2% net population increase per year during the study period) and youngest population of any American state (88.6% are <65 yr) (25). Age is a severity adjustor in the mixed effects logistic regression model for mortality (Table 2).

Smaller cluster randomized trials of pneumonia clinical decision support have demonstrated increased outpatient disposition but without reduction in mortality. The CAPITAL trial (Community-Acquired Pneumonia Intervention Trial Assessing Levofloxacin) studied a critical pathway with the Pneumonia Severity Index manually calculated by ED nurses and showed an 18% increase in outpatient disposition (26). Mortality at baseline was approximately 5% and did not change, although patients with severe pneumonia and many with comorbid illnesses were excluded. The EDCAP (Emergency Department Triage of Community-Acquired Pneumonia) study implemented a project-developed guideline for initial site of treatment based on the Pneumonia Severity Index and performance of evidence-based processes of care at the ED level (7). Three different strategies with escalating intensity of guideline implementation were used, none involving electronic clinical decision support. Outpatient disposition increased by 23% in the moderate- and high-intensity hospital clusters. Twenty percent of eligible patients were not enrolled. Mortality reported only in high-risk patients was unchanged at ∼9%. Compared with the CAPITAL and EDCAP studies, our study cohort had more community hospital patients exposed to the intervention and more severely ill patients, in whom the largest mortality benefit was observed. Unlike prior studies, ePNa is automated and EHR based, and it displays information to clinicians without requiring manual calculation because it only uses data routinely available in ED encounters.

Limitations

The trial was confined to a single healthcare system in one region of the United States with a patient population that may differ from other regions. Our decision not to randomize by cluster (see the first paragraph of Methods) may have affected the results. Patients were identified after their encounters by pneumonia discharge codes plus ED radiographic imaging, a method with high specificity but sensitivity of 68% versus physician review (11). Although this approach enrolls higher-risk patients unable to provide individual consent, we cannot determine whether results would be different if additional patients with pneumonia were included. Our inclusion criteria did not capture ED patients diagnosed with pneumonia and admitted to the hospital but discharged with a different diagnosis, such as pulmonary embolism or cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Because of limitations of the Cerner EHR, we were not able to perform a sensitivity analysis restricted to patients for whom ePNa was used. Because the DRIP score cannot be calculated retrospectively and was not stored within the Cerner EHR, we are not able to specifically link DRIP to antibiotic selection in individual patients.

Conclusions

Deployment of ePNa clinical decision support in 16 community hospitals in a pragmatic, stepped-wedge, cluster-controlled trial was associated with improved processes of care and lower mortality in ED patients with pneumonia.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the emergency department clinicians at Intermountain Healthcare hospitals for their interest in quality improvement and helpful suggestions during development and deployment of ePNa.

Footnotes

Supported by a grant from the Intermountain Healthcare Office of Research, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant R-18 1R18HS026886 (N.C.D., M.P.L., and J.A.I.), the NIH Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (5T32HL105321 to J.R.C.), and Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality grant R03 HS027208-2 (B.J.W.).

Author Contributions: N.C.D., C.G.V., B.J.W., S.M.B., and T.L.A. participated in ePNa development and study design. N.C.D., C.G.V., J.G.R., B.J.W., N.J., M.W., and T.L.A. supported ePNa deployment. J.A.I. and M.P.L. developed the CheXED image processing model and directed its use in the study. N.C.D. and C.G.V. managed the study. J.L., A.R.J., J.R.J., J.G.R., J.R.C., N.J., M.W., B.J.W., and N.C.D. participated in data collection, A.M.B. performed statistical analysis. N.C.D. wrote the first draft and revisions, C.G.V., J.R.C., S.M.B., N.J., B.J.W., J.R.J., A.M.B., and T.L.A. provided critical review and editing.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202109-2092OC on March 8, 2022

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Ramirez JA, Wiemken TL, Peyrani P, Arnold FW, Kelley R, Mattingly WA, et al. University of Louisville Pneumonia Study Group Adults hospitalized with pneumonia in the United States: incidence, epidemiology, and mortality. Clin Infect Dis . 2017;65:1806–1812. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Niederman MS, Luna CM. Community-acquired pneumonia guidelines: a global perspective. Semin Respir Crit Care Med . 2012;33:298–310. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1315642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rosenthal GE, Harper DL, Shah A, Covinsky KE. A regional evaluation of variation in low-severity hospital admissions. J Gen Intern Med . 1997;12:416–422. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1997.00073.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McMahon LF, Jr, Wolfe RA, Tedeschi PJ. Variation in hospital admissions among small areas. A comparison of Maine and Michigan. Med Care . 1989;27:623–631. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198906000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dean NC, Jones JP, Aronsky D, Brown S, Vines CG, Jones BE, et al. Hospital admission decision for patients with community-acquired pneumonia: variability among physicians in an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med . 2012;59:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.07.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mecham ID, Vines C, Dean NC. Community-acquired pneumonia management and outcomes in the era of health information technology. Respirology . 2017;22:1529–1535. doi: 10.1111/resp.13132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yealy DM, Auble TE, Stone RA, Lave JR, Meehan TP, Graff LG, et al. Effect of increasing the intensity of implementing pneumonia guidelines: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med . 2005;143:881–894. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-143-12-200512200-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Thoracic Society Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis . 2007;44:S27–S72. doi: 10.1086/511159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Metlay JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, Anzueto A, Brozek J, Crothers K, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. An official clinical practice guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2019;200:e45–e67. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dean NC, Vines CG, Rubin J, Collingridge DS, Mankivsky M, Srivastava R, et al. Implementation of real-time electronic clinical decision support for emergency department patients with pneumonia across a healthcare system. AMIA Annu Symp Proc . 2020;2019:353–362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dean NC, Jones BE, Jones JP, Ferraro JP, Post HB, Aronsky D, et al. Impact of an electronic clinical decision support tool for emergency department patients with pneumonia. Ann Emerg Med . 2015;66:511–520. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carr JR, Jones BE, Collingridge DS, Webb BJ, Vines C, Zobell B, et al. Deploying an electronic clinical decision support tool for diagnosis and treatment of pneumonia into rural and critical access hospitals: utilization, effect on processes of care, and clinician satisfaction. J Rural Health . 2022;38:262–269. doi: 10.1111/jrh.12543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hemming K, Haines TP, Chilton PJ, Girling AJ, Lilford RJ. The stepped wedge cluster randomised trial: rationale, design, analysis, and reporting. BMJ . 2015;350:h391. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dean NC, Rubin JG, Vines CG, Allen TL, Srivistava R, Webb BJ. Decreased mortality with rollout of electronic pneumonia clinical decision support across 16 Utah hospital emergency departments. Eur Respir J . 2020;56:4667. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Egelund GB, Jensen AV, Andersen SB, Petersen PT, Lindhardt BØ, von Plessen C, et al. Penicillin treatment for patients with community-acquired pneumonia in Denmark: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pulm Med . 2017;17:66. doi: 10.1186/s12890-017-0404-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Irvin JA, Pareek A, Long J, Rajpurkar P, Ken-Ming Eng D, Khandwala N, et al. CheXED: comparison of a deep learning model to a clinical decision support system for pneumonia in the emergency department. J Thorac Imaging . 2022;37:162–167. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0000000000000622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.R Core Team 2020https://www.R-project.org/.

- 18. Jones BE, Collingridge DS, Vines CG, Post H, Holmen J, Allen TL, et al. CDS in a learning health care system: identifying physicians’ reasons for rejection of best-practice recommendations in pneumonia through computerized clinical decision support. Appl Clin Inform . 2019;10:1–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1676587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sanz F, Restrepo MI, Fernández E, Mortensen EM, Aguar MC, Cervera A, et al. Neumonía Adquirida en la Comunidad de la Comunidad Valenciana Study Group Hypoxemia adds to the CURB-65 pneumonia severity score in hospitalized patients with mild pneumonia. Respir Care . 2011;56:612–618. doi: 10.4187/respcare.00853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Majumdar SR, Eurich DT, Gamble JM, Senthilselvan A, Marrie TJ. Oxygen saturations less than 92% are associated with major adverse events in outpatients with pneumonia: a population-based cohort study. Clin Infect Dis . 2011;52:325–331. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Arnold FW, LaJoie AS, Brock GN, Peyrani P, Rello J, Menéndez R, et al. Community-Acquired Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) Investigators Improving outcomes in elderly patients with community-acquired pneumonia by adhering to national guidelines: Community-Acquired Pneumonia Organization International cohort study results. Arch Intern Med . 2009;169:1515–1524. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McCabe C, Kirchner C, Zhang H, Daley J, Fisman DN. Guideline-concordant therapy and reduced mortality and length of stay in adults with community-acquired pneumonia: playing by the rules. Arch Intern Med . 2009;169:1525–1531. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Frei CR, Restrepo MI, Mortensen EM, Burgess DS. Impact of guideline-concordant empiric antibiotic therapy in community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med . 2006;119:865–871. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Buckel WR, Stenehjem E, Sorensen J, Dean N, Webb B. Broad- versus narrow-spectrum oral antibiotic transition and outcomes in health care–associated pneumonia. Ann Am Thorac Soc . 2017;14:200–205. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201606-486BC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Census.gov https://www.census.gov.

- 26. Marrie TJ, Lau CY, Wheeler SL, Wong CJ, Vandervoort MK, Feagan BG, CAPITAL Study Investigators A controlled trial of a critical pathway for treatment of community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA . 2000;283:749–755. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.6.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]