Abstract

Context

Guilu-Erxian-Glue (GLEXG) is a traditional Chinese formula used to improve male reproductive dysfunction.

Objective

To investigate the ferroptosis resistance of GLEXG in the improvement of semen quality in the oligoasthenospermia (OAS) rat model.

Materials and methods

Male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were administered Tripterygium wilfordii polyglycoside, a compound extracted from Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F. (Celastraceae), at a dose of 40 mg/kg/day, to establish an OAS model. Fifty-four SD rats were randomly divided into six groups: sham, model, low-dose GLEXG (GLEXGL, 0.25 g/kg/day), moderate-dose GLEXG (GLEXGM, 0.50 g/kg/day), high-dose GLEXG (GLEXGH, 1.00 g/kg/day) and vitamin E (0.01 g/kg/day) group. The semen quality, structure and function of sperm mitochondria, histopathology, levels of oxidative stress and iron, and mRNA levels and protein expression in the Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 pathway, were analyzed.

Results

Compared with the model group, GLEXGH significantly improved sperm concentration (35.73 ± 15.42 vs. 17.40 ± 4.12, p < 0.05) and motility (58.59 ± 11.06 vs. 28.59 ± 9.42, p < 0.001), and mitigated testicular histopathology. Moreover, GLEXGH markedly reduced the ROS level (5684.28 ± 1345.47 vs. 15500.44 ± 2307.39, p < 0.001) and increased the GPX4 level (48.53 ± 10.78 vs. 23.14 ± 11.04, p < 0.01), decreased the ferrous iron level (36.31 ± 3.66 vs. 48.64 ± 7.74, p < 0.05), and rescued sperm mitochondrial morphology and potential via activating the Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 pathway.

Discussion and conclusions

Ferroptosis resistance from GLEXG might be driven by activation of the Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 pathway. Targeting ferroptosis is a novel approach for OAS therapy.

Keywords: Guilu-Erxian-Glue, oligoasthenospermia, Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway, ferroptosis, Tripterygium wilfordii polyglycoside

Introduction

Infertility, which refers to the inability to conceive after at least one year of unprotected, regular sexual intercourse (Zegers-Hochschild et al. 2017), remains a major challenge affecting 8–12% couples of reproductive ages, of which males account for approximately 50% (Agarwal et al. 2021). Global epidemiological studies have consistently described decreased spermatozoa counts and motility in a persistent trend (Kilchevsky and Honig 2012; Barratt et al. 2017). Additionally, a decline in semen quality among young men in China has been observed between 2001 and 2015, especially in terms of total sperm counts and progressive motility (Huang et al. 2017). Male infertility, which remains poorly understood, is influenced by several factors including genetics, endocrinopathy, presence of varicocele, lifestyle, and adverse environmental exposure (Jensen et al. 2017; Krausz and Riera-Escamilla 2018; Kumar et al. 2019; Krzastek et al. 2020). Idiopathic oligoasthenospermia (OAS) accounts for 60–75% of cases of male infertility (Barratt et al. 2017).

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are excessively active oxidative free radicals. Sperm is vulnerable to ROS due to its limited antioxidant stress damage capacity and limited DNA damage monitoring and repair mechanisms (De Iuliis et al. 2009). Moreover, supraphysiological ROS levels can damage sperm DNA, RNA transcripts, telomere (Tamburrino et al. 2012) and sperm plasma membrane lipid peroxidation (Aitken et al. 1989), which is the main cause of functional defects of sperm. Therefore, oxidative stress injury of the male reproductive system is the main cause of OAS, male infertility and spontaneous abortion (Bisht et al. 2017; Villaverde et al. 2019; Ritchie and Ko 2021). Ferroptosis has recently been discovered as an iron-dependent form of regulated cell death resulting from accumulating lipid peroxidation production and lethal ROS originating from iron metabolism (Dixon et al. 2012; Stockwell et al. 2017). Glutathione peroxidase (GPX4) is a significant antioxidant enzyme in mammals that modulates ferroptotic cell death by protecting cells from lipid peroxidation (Yang et al. 2014). Additionally, GPX4 is highly present in testes and spermatozoa. A decrease in GPX4 levels in spermatozoa has been reported in approximately 30% of infertile men with OAS (Imai et al. 2001). Studies have also indicated that the modification of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway could inhibit oxidative stress in rats to attenuate testicular injury (He et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2019), and ferroptosis may be involved due to the inhibition of the Keap1/Nrf2 pathway (Sun et al. 2016). Additionally, suppressed Nrf2 levels in the spermatozoa are significantly linked to OAS (Chen et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2013).

Currently, drug strategies against OAS are lacking. Coenzyme Q10, L-carnitine, vitamin E, and other drug treatments can improve semen quality; however, rigorous experimental design and high-level randomized clinical trial evidence are lacking (Omar et al. 2019). The indications and efficacy of surgical treatments are also limited (Velasquez and Tanrikut 2014). Recently, advances in assisted reproductive technology have mitigated fertility problems. However, this technology harbors disadvantages, in terms of its cost, genetic risk, and medical ethics (Hansen et al. 2013; Inhorn and Patrizio 2015). Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) provides alternative treatment options, and its curative effects on male infertility have been demonstrated. For instance, Liuwei-Dihuang decoction, Wuzi-Yanzong formula, Jingui-Shenqi pill, and also acupuncture (Jiang et al. 2017; Zhou et al. 2019). Among them, Guilu-Erxian-Glue (GLEXG) is a TCM formula used in the treatment of infertility, which was first recorded in Yibian, an ancient book of TCM. This formula is extremely effective for male and female infertility in long term, especially for those who are suffering from a deficiency of kidney essence.

The inhibition of ferroptosis by GLEXG treatment in those with OAS has not been studied. Here, we established an OAS rat model induced by Tripterygium wilfordii polyglycoside (GTW), a compound extracted and purified from Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F. (Celastraceae), and evaluated the role of GLEXG in improving semen quality. We also determined the expression and role of the Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway and evaluated the ferroptosis inhibition by GLEXG treatment in the OAS rat model. The results may provide an experimental basis for the potential application of GLEXG in the treatment of OAS.

Materials and methods

GLEXG preparation

GLEXG is referenced by the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2020) (Xu et al. 2021) and consists of Cervi Cornus Colla [Cervus elaphus Linnaeus (Cervidae)] (9 g, batch No., 200102), Testudinis Carapacis et Plastri Colla [Chinemys reevesii (Geoemydidae)] (4.5 g, batch No., 2020002), Lycium barbarum L. (Solanaceae) (3 g, batch No., A210616), and Panax ginseng C.A.Mey (Acanthaceae) (3 g, batch No., 2104001). These herbs were purchased from the same batch at Kangmei Pharmaceuticals Co., Ltd. (Guangzhou, China), Prof. Na Yu from the Hunan University of Chinese Medicine authenticated all the herbs. The authenticated voucher specimens are kept in the College of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine, Hunan University of Chinese Medicine. The GLEXG was further prepared and decocted according to the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2020). The final GLEXG decoction was stored in a refrigerator at 4 °C for no more than 3 months. Then, a rotary evaporator was applied to prepare GLEXG at final concentrations of 0.125, 0.25, and 0.50 g/mL for further study.

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats (eight weeks old, weighing 250 ± 20 g) were obtained from Hunan SJA Laboratory Animal Co. Ltd. (Hunan, China). All rats were housed in standard animal cages with a humidity of 60% and temperature of 20 °C with12 h light/dark cycles with free access to water and food. Approval for this study was granted by the Ethical Committee of Hunan University of Chinese Medicine (Hunan, China) (Approval Number: LL2021071403). The protocol followed the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health Guide.

Experimental design and drug administration

After one week of adaptive feeding, the OAS rat model was subjected to GTW by gavage at a dose of 40 mg/kg/day for four weeks. The model was evaluated based on the histopathological features of the testicular tissue and the sperm concentration and motility (Chen et al. 2020; Li et al. 2020). Then, we stratified the model rats at random into five groups (n = 9) as follows: (1) model group: model rats administered distilled water; (2) low-dose GLEXG group (GLEXGL): model rats were subjected to GLEXG by gavage at a dose of 0.25 g/kg/day; (3) moderate-dose GLEXG group (GLEXGM): model rats were subjected to GLEXG by gavage at a dose of 0.50 g/kg/day; (4) high-dose GLEXG group (GLEXGH): model rats were subjected to GLEXG by gavage at a dose of 1.00 g/kg/day; (5) vitamin E group (VE, NO., H20073374, Hangzhou Yipin Xinwufeng Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd): model rats were subjected to VE by gavage at a dose of 0.01 g/kg/day. Additionally, the sham group (n = 9) was treated with distilled water. The rats were administered GLEXG, VE, or distilled water for four weeks. Then, they were anesthetized with ketamine (0.5 g/kg, i.p.). The testes and epididymis were removed for sperm quality assay or flow cytometry, and the rest testes and epididymis were frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution for further detection.

Chemical compounds of GLEXG using liquid chromatography to quadrupole/time-of-flight mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q/TOF-MS)

The chemical compounds in the alcohol extracts of GLEXG were characterized using an ACQUITY UPLC I-Class Plus UPLC system coupled with a XEVO TQ-XS Q/TOF-MS (Waters, USA) in positive and negative ion mode. Chromatography was performed on a Waters HSS T3 column (100.0 mm × 2.1 m, 1.7 μm) with a gradient elution of 0.1% formic acid aqueous solution (A) and acetonitrile (0–10 min, 0.2–20%; 10–20 min, 20–40%; 20–25 min, 40–50%; 25–33 min, 50–98%; 33 min, 50–98% (B). The mass spectrometry conditions were electrospray ionization with positive and negative ion mode scanning. For the negative ion mode, the ion source collision voltage was −4.5 kV, the ion source temperature was 100 °C, the dissolvent gas temperature was 550 °C, the sample and extraction cone voltages were 80 and 10 kV, respectively, and the ion source gas1 and gas2 were 55 Psi. For the positive ion mode, the ion source collision voltage was 5.5 kV, and the rest of the parameters were the same as in the negative ion mode. SCIEX OS (AB SCIEX, US) software was used for data acquisition and spectral processing, and the mass-to-charge ratio scan range was from 60 to 1000 m/z.

Epididymal sperm assay

Sperm concentration, motility, and the number of mobile sperm were detected as previously described (Chang et al. 2021). The cauda epididymis was minced into small pieces and incubated in PBS (37 °C, pH 7.4) for 15 min. Then, we transferred a drop of diluted sperm suspension into a glass slide for analysis using a computer-aided sperm analysis platform (Hamilton Thorn, MA, US) linked to a light microscope (Motic, Xiamen, China). In each rat, ≥10 fields were selected and captured, and the sperm quality index was judged by concentration and motility.

Total, ferric and ferrous iron assay

The total and ferrous iron content of testicular tissues were evaluated as described by the manufacturer. Testicular tissues were introduced to the buffer and homogenized on ice. They were then centrifuged, and the supernatant was obtained. We inoculated the supernatant with an iron probe as well as a microplate reader adopted to read OD values at 593 nm. The total and ferrous iron levels of testicular tissues were determined using an iron colorimetric assay kit as described by the manufacturer (DOJINDO, Beijing, China, I291). Ferric iron was obtained by subtracting ferrous iron from total iron.

Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining

The testes were fixed in 4% PFA for 48 h. They were then dehydrated as they were transferred through a series of mixtures of alcohol and water, and then they were paraffin-embedded. The testes were then sliced into 5 μm segments stained with H&E solution. Thereafter, slides were observed by light microscopy (Motic, Xiamen, China), and micrographs were acquired.

MDA, GPX4, and GSH assays

The testes were taken from liquid nitrogen for preparation of tissue homogenates, and spun at 14,000 g for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and utilized to measure MDA (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, S0131M), GPX4 (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, AF7020), and GSH (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, S0053) using commercial ELISA kits as described by the manufacturers.

Flow cytometry assay

The assay of sperm mitochondrial membrane potential was performed with the lipophilic cationic dye using a JC-1 kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, C2006) as described by the manufacturer. Concisely, 1 × 106 spermatozoa were incubated for 15 min in a JC-1 solution (37 °C; 5 μM). Subsequently, spermatozoa were flushed and analyzed using flow cytometry. Further cytometric experiments were conducted on a flow cytometer (Beckman, CA, US), and the debris was gated out according to light scattering measurements. Flow cytometry acquisition of stained spermatozoa was performed using FL1 and FL2 fluorescence; ≥10,000 spermatozoa were detected for each analysis. The content of testicular tissue ROS production was detected using a DCFH-DA dye based on the ROS kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China, S0033S) as described by the manufacturer. The testes were sliced into 5 μm sections and transferred to a centrifuge tube. Then, 3 mL collagenase II was added, digested at 37 °C for 40 min, filtered to obtain the cell suspension at 500 g, and spun for 5 min. Subsequently, 5 mL red blood cell lysate, which was added to resuspend the cells, lysed at RT (room temperature) for 5 min, and spun at 500 g for 5 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the cells were rinsed twice using PBS and cultured for 30 min in DMEM medium enriched with 10% FBS along with DCFH-DA dye. We digested the cells and analyzed them with a flow cytometer (Beckman, CA, US) to determine the intensity of DCFH-DA fluorescence.

Ultrastructural observation using transmission electron microscopy

Glutaraldehyde was slowly injected into fresh epididymis obtained from the rat using a syringe. Hardened testes were sliced (1 × 1 × 1 mm) and then pre-fixed with glutaraldehyde at 4 °C for 24 h. They were then, rinsed in 0.1 mol/L phosphate buffer and finally fixed in 1% osmic acid. Thereafter, gradient dehydration was performed, followed by embedment of the tissue with epoxy resin, which was processed into ultra-thin slices (1 μm). Finally, we dyed the sections using saturated acetate uranium and employed transmission electron microscopy (Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) to observe the images.

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence assay

The testes were fixed in 4% FPA overnight and sectioned into slices of 2–3 μm. The sections were rinsed three times in PBS, and endogenous peroxidase was blocked using 3% H2O2 at RT for 15 min. Thereafter, sections were blocked using 5% BSA in 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 1 h at RT. Subsequently, we inoculated the sections overnight with anti-GPX4 antibody (Proteintech, Wuhan, China, 14432-1-AP, 1:1,000 dilution) at 4 °C. Then, we rinsed the sections three times in PBS and inoculated them with a secondary antibody for 1 h at RT. Positive immunoreactivity was performed using DAB and assessed by microscopy (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). Images were analyzed using Image-Pro Plus 6.0 (Media Cybernetics, MD, US).

For fluorescent staining, the sections were blocked with 3% BSA for 30 min and incubated overnight with anti-GPX4 antibody (14432-1-AP, 1:100, Proteintech Group, Inc) and anti-FPN1 antibody (Cincinnati, OH, US, DF13561) at 4 °C. The following morning, the sections were rinsed three times in PBS and incubated with fluorescent secondary antibodies (SA00013-3, Proteintech, Wuhan, China) for 1 h in the dark at RT. Subsequently, the sections were rinsed in PBS, counterstained with DAPI (Wellbio, Guangzhou, China) and mounted using Prolong Gold anti-fade (Servicebio, Wuhan, China). The samples were then evaluated using a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

The TRI Reagent (Thermo Scientific, CA, US) was used to isolate the total RNA (tRNA), and cDNA was generated from the tRNA using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific, CA, US). Then, qRT-PCR was conducted using 25 μL of reaction volume consisting of dilute cDNA, specific primers (10 μM) and UItraSYBR Mixture (ComWin, Beijing, China) on the QPCR Platform (Agilent, Shenzhen, China), with β-actin acting as the endogenous standard. Findings are given as fold changes relative to the control group which was set to 100%. Table 1 shows the primers used in this study.

Table 1.

Primary primers for real-time PCR.

| Primer | Forward | Reverse | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| Keap1 | 5′-CCCATGCAGCCCGAACCCAA-3′ | 3′- GTCACCTCCGCCTTGCACTCC-5′ | 131bp |

| Nrf2 | 5′-ACGGCTAAAACTTCCTACTGTGA-3′ | 3′- ACACTTACACAGAAACTAGCCCAA-’5 | 193bp |

| HO1 | 5′-TTGTTATTTCCCCAGTTCTACCAG-3′ | 3′-CAAAAGACAGCCCTACTTGGTT’5 | 87bp |

| FPN1 | 5′-GCTTTGCTGTTCTTTGCCTTAGT-3′ | 3′- GTGTGAGGAACCGGAGATAGC-5′ | 90bp |

| β-actin | 5′-ACATCCGTAAAGACCTCTATGCC-3′ | 3′-TACTCCTGCTTGCTGATCCAC-’5 | 223bp |

Western blot

Testicular tissue preserved in liquid nitrogen was thawed, added to a grinder with the lysate, ground and lysed on ice for 15 min, transferred to a centrifuge tube, and span at 4 °C for 15 min at 14,000 g in an ultrafast freezing centrifuge. We collected the supernatant in an Eppendorf tube, total proteins were quantified using the BCA Kit (ComWin, Beijing, China, CW2011), and the protein sample was mixed with protein electrophoresis loading buffer, boiled for 10 min and set aside. Membranes were inoculated overnight with primary antibodies (Proteintech, Wuhan, China), including anti-Keap1 (10503-2-AP, 1:5,000 dilution), anti-Nrf2 (16396-1-AP, 1:2,000 dilution), anti-HO1 (10701-1-AP, 1:3,000 dilution), anti-FPN1(26601-1-AP, 1:1,000 dilution), anti-GPX4 (14432-1-AP, 1:1,000 dilution), anti-PCNA (60097-1-Ig, 1:6,000 dilution) and anti-β-actin (66009-1-Ig, 1:5,000 dilution) at 4 °C. They were then rinsed three times with PBST, and then inoculated for 2 h with HRP-linked goat anti-rabbit IgG (66009-1-Ig, 1:5,000 dilution). They were then rinsed three more times with PBST for 10 min each time and developed using ECL chemiluminescence. The hybridized bands were scanned for grey values via the Image J software (Bethesda, MDUS). The results are presented as the ratio of the grey values of the protein bands to that of the β-actin or PCNA bands and were corrected and normalized for β-actin or PCNA.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted in GraphPad Prism 8.01 software (La Jolla, CA, USA). The data are given as the mean ±standard deviation (SEM). One-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) followed by a post hoc least significant difference (LSD) test was adopted to calculate the statistical significance between groups, and p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Chemical compounds of GLEXG

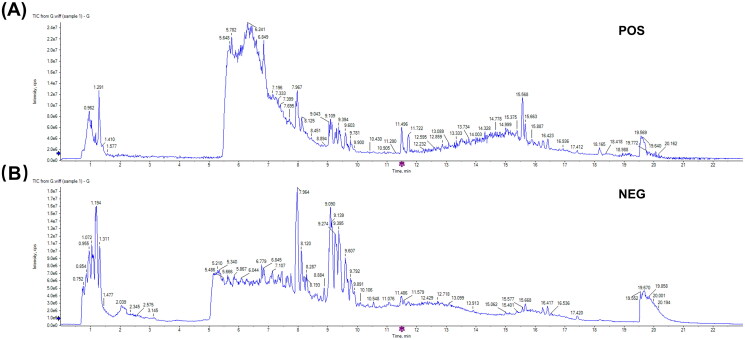

The chemical compounds of GLEXG were analyzed using UPLC-Q/TOF-MS, and the ion diagrams are illustrated in Figure 1(A–B)) and identified compounds are shown in Table 2. Ultimately, 122 compounds in positive ion mode and 66 in negative ion mode were identified in GLEXG.

Figure 1.

Ion flow diagram of GLEXG detected by UPLC-Q/TOF-MS. Positive ion mode (A) and negative ion mode (B).

Table 2.

Mass spectrometry data and elemental composition of compounds GLEXG by UPLC-Q/TOF-MS analysis.

| No. | Compounds | Formula | Library score | Retention time (min) | Precursor mass (m/z) | Area | Height |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive ion mode | |||||||

| 1 | γ-Glutamate-cysteine | C8H14N2O5S | 89.9 | 0.84 | 3.99E + 05 | 1.07E + 05 | 248.962 |

| 2 | Histidine | C6H9N3O2 | 97.6 | 0.88 | 8.29E + 04 | 3.19E + 04 | 154.064 |

| 3 | L-Arginine | C7H16N4O2 | 99.7 | 0.88 | 3.27E + 05 | 1.19E + 05 | 173.106 |

| 4 | Aspartic acid | C4H7NO4 | 98.3 | 0.9 | 1.61E + 05 | 5.31E + 04 | 132.032 |

| 5 | D-(+)-Mannose | C6H12O6 | 68.4 | 0.96 | 8.11E + 06 | 1.32E + 06 | 215.035 |

| 6 | Gluconic acid | C6H12O7 | 48.9 | 0.97 | 2.40E + 06 | 4.96E + 05 | 195.053 |

| 7 | Saccharate | C6H10O8 | 99.5 | 0.98 | 1.09E + 06 | 2.04E + 05 | 209.032 |

| 8 | D-Tagatose | C6H12O6 | 72.8 | 1 | 1.30E + 06 | 2.27E + 05 | 179.057 |

| 9 | Isomaltose | C12H22O11 | 84.9 | 1.04 | 3.89E + 06 | 8.97E + 05 | 377.087 |

| 10 | Quinic acid | C7H12O6 | 98.2 | 1.1 | 1.25E + 06 | 3.74E + 05 | 191.058 |

| 11 | Malate | C4H6O5 | 99.7 | 1.27 | 1.45E + 06 | 4.27E + 05 | 133.015 |

| 12 | N-Acetylglutamate | C7H11NO5 | 97.3 | 1.51 | 1.48E + 05 | 2.02E + 04 | 188.058 |

| 13 | Lactate | C3H6O3 | 98.9 | 1.59 | 3.54E + 05 | 2.91E + 04 | 89.025 |

| 14 | Oxoproline | C5H7NO3 | 93.5 | 2.37 | 1.14E + 06 | 1.26E + 05 | 128.037 |

| 15 | Methylmalonate | C4H6O4 | 99.5 | 2.7 | 2.55E + 05 | 2.26E + 04 | 117.02 |

| 16 | cis-Aconitic acid | C6H6O | 96.4 | 2.9 | 1.81E + 05 | 1.24E + 04 | 173.01 |

| 17 | N-Acetylalanin | C5H9NO3 | 98.2 | 3.03 | 8.61E + 04 | 9.59E + 03 | 130.088 |

| 18 | Xanthine | C5H4N4O2 | 99.2 | 3.06 | 1.13E + 05 | 1.21E + 04 | 151.027 |

| 19 | Tyrosine | C9H11NO3 | 96.9 | 3.13 | 3.56E + 05 | 3.40E + 04 | 180.068 |

| 20 | (S)-2-Hydroxybutanoic acid | C4H8O3 | 100 | 3.4 | 5.66E + 04 | 5.23E + 03 | 103.041 |

| 21 | Uridine | C9H12N2O6 | 89.1 | 3.42 | 2.63E + 05 | 2.28E + 04 | 243.064 |

| 22 | Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) | C8HF17O3S | 68.8 | 3.99 | 7.53E + 04 | 6.18E + 03 | 499.132 |

| 23 | Adenosine 2′,3′-cyclic phosphate | C10H12N5O6P | 98.6 | 4.18 | 3.74E + 05 | 3.02E + 04 | 328.047 |

| 24 | Guanosine monophosphate | C10H14N5O8P | 99 | 4.23 | 1.13E + 05 | 7.30E + 03 | 362.052 |

| 25 | L-Tryptophanamide | C11H13N3O | 94 | 4.44 | 1.62E + 05 | 7.33E + 03 | 202.11 |

| 26 | Neohesperidin | C28H34O15 | 35.5 | 5.04 | 2.18E + 04 | 6.06E + 03 | 609.077 |

| 27 | Acadesine | C9H14N4O5 | 45 | 5.05 | 5.69E + 04 | 1.19E + 04 | 337.079 |

| 28 | Citric acid | C6H8O7 | 99.2 | 5.12 | 4.38E + 05 | 4.82E + 04 | 191.021 |

| 29 | Inosine | C10H12N4O5 | 100 | 5.15 | 9.97E + 04 | 3.21E + 04 | 267.074 |

| 30 | 3,4,5-Trimethoxybenzoic acid | C10H11O5 | 63.8 | 5.2 | 3.29E + 05 | 6.00E + 04 | 211.074 |

| 31 | Resibufogenin | C24H32O4 | 53.3 | 5.27 | 1.51E + 05 | 2.36E + 04 | 429.162 |

| 32 | Phenylalanine | C9H11NO2 | 96.7 | 5.3 | 3.36E + 05 | 7.71E + 04 | 164.073 |

| 33 | Secalonic acid D | C32H30O14 | 74 | 5.34 | 1.04E + 05 | 2.04E + 04 | 637.298 |

| 34 | Heteroclitin D | C27H30O8 | 42.5 | 5.35 | 1.63E + 05 | 2.29E + 04 | 481.207 |

| 35 | Typhaneoside | C34H42O20 | 84.6 | 5.39 | 2.32E + 05 | 6.00E + 04 | 769.352 |

| 36 | Pedunculoside | C36H58O10 | 60.7 | 5.42 | 1.62E + 05 | 3.10E + 04 | 695.207 |

| 37 | Trehalose | C12H22O11 | 60.3 | 5.43 | 9.80E + 04 | 2.45E + 04 | 341.085 |

| 38 | Calceorioside B | C23H26O11 | 85.6 | 5.46 | 2.23E + 05 | 4.90E + 04 | 477.126 |

| 39 | D-Pantothenic acid | C9H17NO5 | 97.3 | 5.48 | 6.57E + 04 | 1.84E + 04 | 218.104 |

| 40 | Adipate | C6H10O4 | 93.2 | 5.77 | 4.65E + 04 | 1.34E + 04 | 145.051 |

| 41 | L-Tryptophan | C11H12N2O2 | 97.6 | 5.83 | 4.28E + 05 | 1.20E + 05 | 203.084 |

| 42 | 2-Chloro-L-phenylalanine | C9H10ClNO2 | 96.4 | 5.87 | 1.60E + 05 | 4.72E + 04 | 198.034 |

| 43 | 2-Hydroxyphenylacetate | C8H8O3 | 96.3 | 5.96 | 1.03E + 05 | 3.00E + 04 | 181.052 |

| 44 | Sibiricose A5 | C22H30O14 | 78.5 | 6.11 | 1.03E + 05 | 1.87E + 04 | 517.157 |

| 45 | Traumatic acid | C12H20O4 | 83.7 | 6.13 | 8.91E + 04 | 2.36E + 04 | 227.105 |

| 46 | 2′-Deoxyguanosine-5′-diphosphate trisodium salt | C10H12N5Na3O10P2 | 50 | 6.13 | 8.61E + 04 | 2.00E + 04 | 426.2 |

| 47 | Asiatic acid | C30H48O5 | 49.3 | 6.18 | 9.87E + 04 | 1.96E + 04 | 487.253 |

| 48 | 2-Isopropylmalic acid | C7H12O5 | 100 | 6.25 | 6.87E + 05 | 1.72E + 05 | 175.063 |

| 49 | Chlorogenic acid | C16H18O9 | 100 | 6.27 | 1.56E + 05 | 4.14E + 04 | 353.089 |

| 50 | 3-Methyladipic acid | C7H12O4 | 99 | 6.5 | 2.02E + 05 | 6.33E + 04 | 159.068 |

| 51 | Raffinose | C18H32O16 | 82.2 | 6.62 | 2.03E + 05 | 6.08E + 04 | 503.178 |

| 52 | (S)-(-)-2-Hydroxyisocaproic acid | C6H12O3 | 98.1 | 6.96 | 1.71E + 05 | 3.84E + 04 | 131.072 |

| 53 | Ginsenoside-Ro | C48H76O19 | 70.6 | 7.07 | 2.23E + 05 | 3.32E + 04 | 955.377 |

| 54 | 4-Coumarate | C9H8O3 | 98.1 | 7.29 | 5.41E + 05 | 1.61E + 05 | 163.041 |

| 55 | 6-Phenyl-2-thiouracil | C10H8N2OS | 50.6 | 7.31 | 1.02E + 05 | 3.21E + 04 | 203.131 |

| 56 | 8-Hydroxyoctanoic acid | C8H16O3 | 99.7 | 7.35 | 5.56E + 05 | 1.75E + 05 | 159.104 |

| 57 | L-3-Phenyllactic acid | C9H10O3 | 98.9 | 7.39 | 2.47E + 05 | 7.51E + 04 | 165.057 |

| 58 | N-Acetyl-L-tryptophan | C13H14N2O3 | 98.6 | 7.45 | 1.17E + 06 | 3.18E + 05 | 245.095 |

| 59 | Decanoate | C10H20O2 | 90.9 | 7.51 | 2.03E + 05 | 5.18E + 04 | 171.068 |

| 60 | Isoferulic acid | C10H10O4 | 100 | 7.53 | 1.81E + 05 | 5.42E + 04 | 193.052 |

| 61 | Scopoletin | C10H8O4 | 98.6 | 7.57 | 7.87E + 04 | 2.30E + 04 | 191.037 |

| 62 | Capric acid | C10H20O2 | 33.9 | 7.71 | 3.93E + 05 | 1.22E + 05 | 231.126 |

| 63 | Notoginsenoside R1 | C47H80O18 | 96.2 | 7.76 | 1.33E + 06 | 3.79E + 05 | 977.537 |

| 64 | Ginsenoside Re | C48H82O18 | 86.3 | 7.93 | 3.51E + 06 | 9.07E + 05 | 991.553 |

| 65 | Azelate | C9H16O4 | 97.3 | 7.94 | 4.79E + 06 | 1.37E + 06 | 187.099 |

| 66 | Ginsenoside Rg1 | C42H72O14 | 98.2 | 7.99 | 1.35E + 07 | 3.85E + 06 | 845.494 |

| 67 | Suberate | C8H14O4 | 54.1 | 8.1 | 4.11E + 05 | 1.39E + 05 | 173.12 |

| 68 | L-Dihydroorotic acid | C5H6N2O4 | 41 | 8.37 | 1.78E + 05 | 5.48E + 04 | 157.088 |

| 69 | Adenosine diphosphate ribose | C15H23N5O14P2 | 71.2 | 8.51 | 6.24E + 04 | 1.70E + 04 | 558.295 |

| 70 | Agistatin B | C11H18O4 | 33.5 | 8.54 | 3.18E + 04 | 9.17E + 03 | 213.114 |

| 71 | Oxoadipic acid | C6H8O5 | 91.9 | 8.58 | 8.13E + 05 | 2.37E + 05 | 159.104 |

| 72 | Sebacate | C10H18O4 | 99 | 8.64 | 1.21E + 06 | 3.48E + 05 | 201.115 |

| 73 | Crocetin | C20H24O4 | 38.2 | 8.75 | 1.21E + 05 | 2.56E + 04 | 327.219 |

| 74 | 10-Hydroxydecanoate | C10H20O3 | 80.2 | 8.83 | 1.60E + 05 | 4.73E + 04 | 187.135 |

| 75 | Astragaloside IV | C41H68O14 | 96.8 | 8.85 | 3.94E + 04 | 9.63E + 03 | 829.499 |

| 76 | 10-Hydroxydec-2-enoic acid | C10H18O3 | 72.3 | 8.89 | 4.11E + 05 | 1.17E + 05 | 185.119 |

| 77 | Astragaloside I | C45H72O16 | 90.8 | 8.96 | 6.94E + 04 | 2.06E + 04 | 913.52 |

| 78 | 4-Ethylbenzoic acid | C2H5C6H4CO2H | 100 | 8.98 | 7.47E + 04 | 2.40E + 04 | 149.062 |

| 79 | Ginsenoside Rf | C42H72O14 | 95.9 | 9.05 | 4.64E + 06 | 1.36E + 06 | 845.493 |

| 80 | Ginsenoside Rb1 | C54H92O23 | 40.1 | 9.1 | 1.44E + 06 | 4.10E + 05 | 1153.605 |

| 81 | Ginsenoside Rc | C53H90O22 | 87.5 | 9.25 | 4.56E + 05 | 1.35E + 05 | 1077.588 |

| 82 | Ginsenoside Rb2 | C53H90O22 | 98.1 | 9.26 | 1.37E + 06 | 4.20E + 05 | 1123.593 |

| 83 | Undecanedioic Acid | C11H20O4 | 99.6 | 9.3 | 4.58E + 05 | 1.31E + 05 | 215.13 |

| 84 | Ginsenoside Rg2 | C42H72O13 | 100 | 9.42 | 8.41E + 05 | 1.93E + 05 | 829.498 |

| 85 | 4-Bromophenylalanine | C9H10BrNO2 | 77.8 | 9.53 | 3.45E + 05 | 1.09E + 05 | 242.177 |

| 86 | 20(R)-Ginsenoside Rh1 | C36H62O9 | 98 | 9.55 | 7.28E + 05 | 2.40E + 05 | 683.439 |

| 87 | 11a-Hydroxyprogesterone | C21H30O3 | 89.4 | 9.61 | 2.33E + 06 | 5.27E + 05 | 659.476 |

| 88 | Ginsenoside Rd | C48H82O18 | 91 | 9.77 | 2.18E + 06 | 6.50E + 05 | 991.55 |

| 89 | Gypenoside XVII | C48H82O18 | 62.3 | 9.77 | 3.04E + 05 | 9.41E + 04 | 945.545 |

| 90 | Kaempferol | C15H10O6 | 92.5 | 9.85 | 2.41E + 05 | 5.48E + 04 | 285.208 |

| 91 | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate | C3H7O6P | 47.2 | 9.9 | 9.28E + 04 | 2.59E + 04 | 169.088 |

| 92 | Dodecanedioic acid | C12H22O4 | 100 | 9.93 | 3.04E + 05 | 8.56E + 04 | 229.146 |

| 93 | Notoginsenoside Ft1 | C47H80O17 | 98.2 | 10.28 | 1.06E + 05 | 1.98E + 04 | 961.541 |

| 94 | Arachidate | C20H40O2 | 56.4 | 10.51 | 1.68E + 05 | 3.13E + 04 | 311.224 |

| 95 | 1,11-Undecanedicarboxylic acid | C13H24O4 | 98.4 | 10.55 | 9.97E + 05 | 2.68E + 05 | 243.162 |

| 96 | Estriol | C18H24O3 | 70.1 | 10.94 | 2.10E + 05 | 5.63E + 04 | 287.224 |

| 97 | Geranyl-PP | C10H20O7P2 | 61.7 | 11.02 | 9.57E + 05 | 1.38E + 05 | 313.24 |

| 98 | Chikusetsusponin Iva | C42H66O14 | 100 | 11.09 | 2.90E + 05 | 7.32E + 04 | 793.44 |

| 99 | Stachyose | C24H42O21 | 97.4 | 11.23 | 2.49E + 05 | 7.13E + 04 | 665.429 |

| 100 | 20(R)-Ginsenoside Rg3 | C42H72O13 | 97.9 | 11.47 | 3.27E + 05 | 8.85E + 04 | 829.498 |

| 101 | Heptadecanoate | C17H34O2 | 73.2 | 12.18 | 1.41E + 05 | 3.92E + 04 | 269.214 |

| 102 | Isorhamnetin | C16H12O7 | 84.4 | 12.47 | 1.71E + 05 | 4.73E + 04 | 315.255 |

| 103 | 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol | C14H22O | 38.5 | 13.9 | 3.50E + 04 | 9.54E + 03 | 205.161 |

| 104 | All-trans-retinoic acid | C20H28O2 | 76.7 | 14.21 | 9.16E + 04 | 2.35E + 04 | 299.261 |

| 105 | Nonadecanoic acid | C19H38O2 | 80.5 | 14.51 | 5.03E + 04 | 1.44E + 04 | 297.244 |

| 106 | Sulfamethazine | C12H14N4O2S | 100 | 15 | 4.27E + 05 | 1.14E + 05 | 277.219 |

| 107 | 1-Pentadecanol | CH3(CH2)14OH | 98.1 | 15.15 | 9.93E + 04 | 2.82E + 04 | 227.202 |

| 108 | Shikimate-3-phosphate | C7H11O8P | 90.8 | 15.39 | 3.86E + 05 | 9.38E + 04 | 253.218 |

| 109 | Arachidonic acid | C20H32O2 | 99.8 | 15.51 | 1.37E + 05 | 3.78E + 04 | 303.234 |

| 110 | Linoleic acid | C18H32O2 | 100 | 15.67 | 1.31E + 06 | 3.34E + 05 | 279.234 |

| 111 | Palmitate | C16H32O2 | 92 | 16.26 | 9.61E + 05 | 2.37E + 05 | 255.234 |

| 112 | Glycerophosphocholine | C22H44NO6PS2 | 73.6 | 16.26 | 1.80E + 05 | 4.47E + 04 | 256.237 |

| 113 | Vaccenic acid | C18H34O2 | 89.3 | 16.42 | 1.51E + 06 | 3.68E + 05 | 281.25 |

| 114 | 1-Aminocyclopropanecarboxylate | C4H7NO2 | 88.8 | 16.64 | 5.40E + 03 | 1.49E + 03 | 99.926 |

| 115 | Estrone | C18H22O2 | 90.1 | 16.82 | 4.89E + 04 | 1.24E + 04 | 269.25 |

| 116 | Ethyl hexadecanoate1 | CH3(CH2)14COOC2H5 | 100 | 17.42 | 8.38E + 05 | 1.66E + 05 | 283.266 |

| 117 | Sulfadoxine | C12H14N4O4S | 97.2 | 17.52 | 6.31E + 04 | 1.27E + 04 | 309.281 |

| 118 | N, N-Dimethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine | C8H12N2 | 32.4 | 18.19 | 3.79E + 04 | 6.62E + 03 | 134.895 |

| 119 | Valine | C5H11NO2 | 63 | 19.54 | 2.82E + 04 | 1.30E + 04 | 115.921 |

| 120 | Mesoxalate | C3H2O5 | 100 | 19.87 | 5.29E + 05 | 4.31E + 04 | 116.929 |

| 121 | Diethanolamine | C4H11NO2 | 68.1 | 20.63 | 1.35E + 03 | 5.68E + 02 | 103.921 |

| 122 | Aicar | C9H15N4O8P | 45 | 5.05 | 5.69E + 04 | 1.19E + 04 | 337.079 |

| Negative ion mode | |||||||

| 1 | Caprolactone | C6H10O2 | 92.7 | 0.72 | 3.29E + 04 | 6.60E + 03 | 114.988 |

| 2 | Arginine | C6H14N4O2 | 89.7 | 0.89 | 4.71E + 04 | 2.05E + 04 | 349.231 |

| 3 | Glutamine | C5H10N2O3 | 99.7 | 0.92 | 9.45E + 04 | 2.82E + 04 | 147.076 |

| 4 | Glycerophosphocholine | C8H20NO6P | 97.2 | 0.97 | 3.96E + 05 | 1.11E + 05 | 258.11 |

| 5 | Betain | C5H11NO2 | 36.2 | 1.01 | 4.91E + 05 | 1.30E + 05 | 118.086 |

| 6 | Proline acid | C5H9NO2 | 53 | 1.09 | 3.97E + 05 | 1.15E + 05 | 116.07 |

| 7 | Tyrosin | C9H11NO3 | 98.7 | 1.43 | 3.91E + 05 | 5.39E + 04 | 182.081 |

| 8 | Vitamin C | C6H8O6 | 98.9 | 2.08 | 2.20E + 05 | 2.59E + 04 | 177.039 |

| 9 | Suberic acid | C8H14O4 | 32.3 | 2.2 | 6.20E + 04 | 8.17E + 03 | 175.024 |

| 10 | S-Methyl glutathione | C11H19N3O6S | 57.1 | 2.22 | 6.12E + 04 | 6.06E + 03 | 322.077 |

| 11 | Pyroglutamate | C5H7NO3 | 100 | 2.4 | 1.98E + 05 | 3.12E + 04 | 130.05 |

| 12 | Leucine | C6H13NO2 | 98.6 | 3.07 | 2.94E + 05 | 3.08E + 04 | 132.102 |

| 13 | Amphetamine | C9H13N | 50.1 | 3.17 | 6.25E + 04 | 6.71E + 03 | 136.075 |

| 14 | Fucose | C6H12O5 | 47.3 | 3.17 | 1.13E + 05 | 1.13E + 04 | 165.054 |

| 15 | Glyceraldehyde | C3H6O3 | 93.5 | 3.35 | 2.12E + 04 | 2.05E + 03 | 121.064 |

| 16 | Xanthosine | C10H12N4O6 | 53.8 | 3.42 | 2.50E + 04 | 2.85E + 03 | 285.102 |

| 17 | Uracil | C4H4N2O2 | 77.9 | 3.43 | 1.86E + 04 | 2.61E + 03 | 113.034 |

| 18 | Guanosine | C10H13N5O5 | 100 | 3.55 | 2.70E + 05 | 2.40E + 04 | 284.1 |

| 19 | 3′-Aenylic acid | C10H14N5O7P | 100 | 3.56 | 5.03E + 04 | 4.67E + 03 | 348.071 |

| 20 | 6-Hydroxypurine | C5H4N4O | 79.8 | 3.58 | 1.51E + 05 | 1.04E + 04 | 137.046 |

| 21 | Cyclic AMP | C10H12N5O6P | 98.8 | 4.27 | 2.07E + 05 | 1.80E + 04 | 330.06 |

| 22 | Cyclic GMP | C10H12N5O7P | 100 | 5.46 | 2.17E + 05 | 4.18E + 04 | 346.055 |

| 23 | Adenosine | C10H13N5O4 | 100 | 5.5 | 1.41E + 05 | 4.08E + 04 | 268.104 |

| 24 | Guanine | C5H5N5O | 92.4 | 5.53 | 5.25E + 04 | 8.79E + 03 | 152.056 |

| 25 | Rutin | C27H30O16 | 97.2 | 7.11 | 2.74E + 05 | 7.95E + 04 | 611.16 |

| 26 | 3,4-Dihydroxybenzoate | C7H6O4 | 95.4 | 8.89 | 3.26E + 04 | 9.44E + 03 | 155.106 |

| 27 | Pseuoginsenoside F11 | C42H72O14 | 98.2 | 9.09 | 2.88E + 05 | 8.36E + 04 | 801.498 |

| 28 | Uvaol | C30H50O2 | 91.3 | 9.12 | 3.79E + 05 | 5.86E + 04 | 443.388 |

| 29 | Cortisone 21-acetate | C23H30O6 | 37.5 | 9.56 | 2.59E + 04 | 8.23E + 03 | 405.351 |

| 30 | Androsterone | C19H30O2 | 34.1 | 9.77 | 3.27E + 04 | 9.51E + 03 | 291.195 |

| 31 | Sclareolide | C16H26O2 | 76.9 | 9.95 | 1.70E + 04 | 4.93E + 03 | 251.2 |

| 32 | Methyl linoleate | C19H34O2 | 68.1 | 10.52 | 1.49E + 05 | 1.25E + 04 | 295.227 |

| 33 | Methyl dihydrojasmonate | C13H22O3 | 85.4 | 10.55 | 6.06E + 04 | 1.46E + 04 | 227.164 |

| 34 | 6-Phosphogluconate | C6H13O10P | 40.5 | 10.61 | 6.00E + 04 | 6.32E + 03 | 277.216 |

| 35 | Palmitoleate | C16H30O2 | 44.2 | 10.65 | 2.50E + 04 | 6.40E + 03 | 255.159 |

| 36 | Corydaline | C22H27NO4 | 46.8 | 10.67 | 1.21E + 04 | 3.30E + 03 | 370.241 |

| 37 | Gamma-linolenate | C18H30O2 | 98.3 | 10.68 | 3.66E + 04 | 3.90E + 03 | 279.159 |

| 38 | 15-Hydroxyculmorone | C15H24O3 | 40.6 | 10.87 | 2.04E + 04 | 5.64E + 03 | 253.18 |

| 39 | Cytidine diphosphate | C9H15N3O11P2 | 60.3 | 10.92 | 5.14E + 04 | 1.41E + 04 | 404.206 |

| 40 | Panaxydol | C17H24O2 | 77.7 | 11.45 | 2.75E + 04 | 7.94E + 03 | 261.184 |

| 41 | Ursodeoxycholate | C24H40O4 | 100 | 11.51 | 1.76E + 06 | 4.55E + 05 | 393.285 |

| 42 | β-Sitosterol | C29H50O | 96.2 | 11.73 | 6.76E + 05 | 1.74E + 05 | 432.238 |

| 43 | Petroselinate | C18H34O2 | 97.8 | 15.67 | 4.40E + 05 | 1.19E + 05 | 282.278 |

| 44 | Stearate | C18H36O2 | 84.4 | 16.67 | 4.06E + 04 | 9.57E + 03 | 285.298 |

| 45 | Myristic acid (D27) | C14H54HO2 | 38.2 | 16.88 | 3.67E + 04 | 9.08E + 03 | 256.263 |

| 46 | Octadecanamide | CH3(CH2)16CONH2 | 64.1 | 16.95 | 6.19E + 05 | 1.39E + 05 | 284.295 |

| 47 | Monensin | C36H62O11 | 90.7 | 17.09 | 2.31E + 04 | 5.40E + 03 | 693.454 |

| 48 | Buspirone | C21H31N5O2 | 33.9 | 17.27 | 7.05E + 04 | 1.51E + 04 | 386.342 |

| 49 | Bisoprolol | C18H31NO4 | 32.6 | 17.4 | 4.59E + 04 | 1.07E + 04 | 326.342 |

| 50 | Trimethylamine | C3H9N | 91.6 | 17.52 | 1.14E + 04 | 1.76E + 03 | 60.044 |

| 51 | Phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate | C5H13O14P3 | 98.6 | 17.58 | 2.84E + 05 | 5.84E + 04 | 391.284 |

| 52 | Naratriptan | C17H25N3O2S | 79.8 | 17.76 | 3.93E + 04 | 7.49E + 03 | 336.326 |

| 53 | Allyl isothiocyanate | C4H5NS | 99.5 | 17.8 | 4.90E + 04 | 4.84E + 03 | 100.075 |

| 54 | Citramalate | C5H8O5 | 84.9 | 17.81 | 2.77E + 04 | 2.69E + 03 | 149.023 |

| 55 | o-Xylene | C6H4(CH3)2 | 97.5 | 17.92 | 6.34E + 04 | 3.15E + 03 | 107.07 |

| 56 | 7-Ketocholesterol | C27H44O2 | 94.7 | 17.92 | 9.92E + 04 | 2.07E + 04 | 401.341 |

| 57 | Danazol | C22H27NO2 | 58.6 | 18.18 | 3.34E + 05 | 7.39E + 04 | 675.675 |

| 58 | Leonurine | C14H21O5N3 | 84.1 | 18.47 | 8.53E + 04 | 1.59E + 04 | 312.326 |

| 59 | Dibutyl phthalate | C16H22O4 | 99.5 | 18.51 | 1.24E + 05 | 7.23E + 03 | 279.159 |

| 60 | Patchouli alcohol | C15H24 | 91.7 | 18.52 | 9.20E + 04 | 5.55E + 03 | 205.086 |

| 61 | 1-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone | C5H9NO | 98.1 | 18.53 | 8.25E + 04 | 6.82E + 03 | 100.075 |

| 62 | Benzoate | C7H6O2 | 44.5 | 19.65 | 2.47E + 05 | 2.71E + 04 | 122.964 |

| 63 | 5-Hydroxylysin | C6H14N2O3 | 86.1 | 19.91 | 1.84E + 04 | 5.38E + 03 | 163.132 |

| 64 | m-Xylene | C6H4(CH3)2 | 60.6 | 21.61 | 6.62E + 03 | 1.98E + 03 | 107.07 |

| 65 | 1,2-Dichloroethane | C2H4Cl2 | 97.2 | 21.68 | 1.27E + 04 | 5.46E + 03 | 100.076 |

| 66 | β-alanine | C3H7NO2 | 30.1 | 21.68 | 3.80E + 03 | 1.63E + 03 | 89.939 |

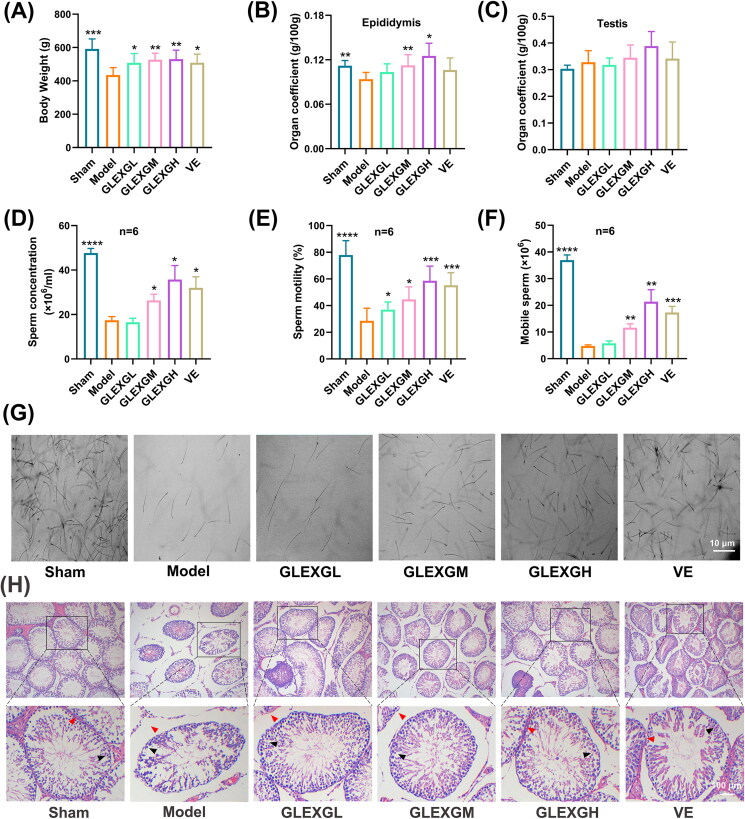

Body weight and organ coefficients

No differences in body weight were observed among the groups before the experiment. As the experiment progressed, the body weight of each group gradually increased. After the experiment, the body weight of the model group was significantly lower than those of the sham group. With the administration of GLEXG, the weight increased significantly (Figure 2(A)). The epididymal coefficients of the model group were significantly lower than those of the sham group, and those of the GLEXGM and GLEXGH group were significantly higher than those of the model group (Figure 2(B)). The testicular coefficient in each group was not statistically significant (Figure 2(C)).

Figure 2.

GLEXG treatment mitigated histopathological lesions of testes and improved semen quality in the epididymis of an OAS rat model induced by GTW. (A–C) Body weights of rats, and organ coefficients of testis and epididymis in each group. (D–F) Effect of GLEXG on sperm concentration, motility, and the number of mobile sperm. (G) Representative sperm images under microscopy in each group. (H) Representative H&E staining of testicular tissue in each group. Red and black arrowheads indicate seminiferous tubule space and spermatogenic cells, respectively. Data are shown as the means ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 vs. the model group, respectively.

GLEXG treatment improved semen quality in epididymis and mitigated histopathological lesions of testes in OAS rat model induced by GTW

GTW administration resulted in a remarkable decrease in sperm concentration, motility, and the number of mobile sperm. However, treatment with GLEXG significantly increased the sperm concentration, motility, and the number of mobile sperm (Figure 2(D–F)). Representative sperm images under microscopy from each group were shown in Figure 2(G). In histological analysis (Figure 2(H)), the sham group exhibited normal arrangement of spermatogenic cells in seminiferous tubules, without histopathologic lesions. In contrast, the model group had obvious damage to testicular tissues, consisting of intertubular edema, exfoliation of the seminiferous tubules, vacuolization in the cytoplasm of Sertoli cells, and unordered arrangement of spermatogenic cells. GLEXG treatment mitigated the histopathologic lesions and demonstrated the greatest improvement in the high dose group.

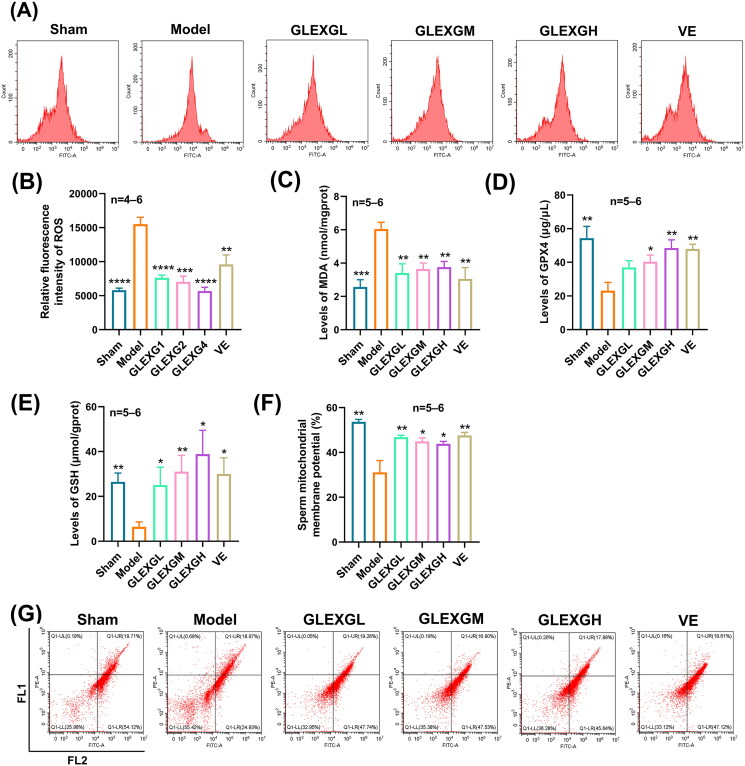

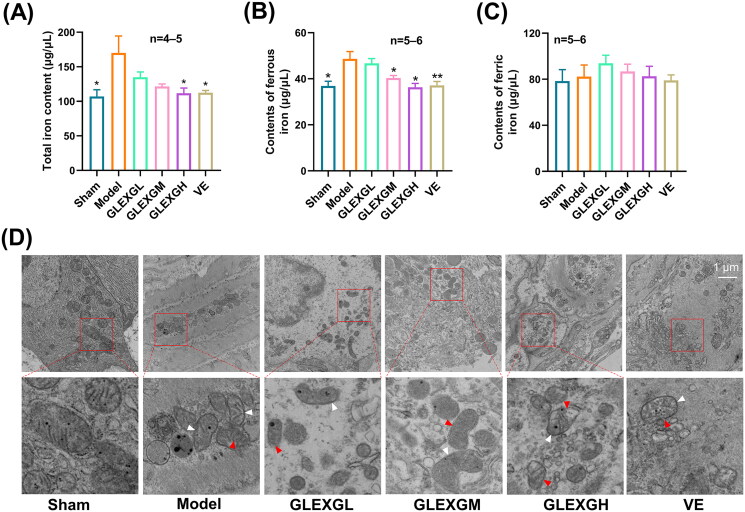

GLEXG improved oxidative stress and iron metabolism of testicular tissue in OAS rat model induced by GTW

Based on previous research (Hou et al. 2016), the MDA and ROS levels can be utilized as a measurement of lipid peroxidation in cells or tissues. GTW administration triggered a remarkable increase in MDA and ROS levels in the testes compared with the sham group, however, the GPX4 and GSH levels significantly decreased, which is a molecular signature of ferroptosis. After GLEXG treatment, the MDA and ROS levels were reduced, while the GPX4 and GSH levels increased (Figure 3(A–E)). In contrast with the sham group, the level of sperm mitochondrial membrane potential significantly decreased in the model group; however, after GLEXG treatment, there was a remarkable increase of the level in sperm mitochondrial membrane potential (Figure 3(F,G)). Additionally, GTW administration also resulted in increases in ferrous and total iron, but not ferric iron (Figure 4(A–C)). We also observed that GTW administration resulted in characteristic morphologic features associated with ferroptosis in the model groups, including shrunken mitochondria, diminished mitochondrial cristae, chromatin condensation, cytoplasmic and organelle swelling and plasma membrane rupture. After GLEXG treatment, sperm mitochondria morphology damage was mitigated (Figure 4(D)).

Figure 3.

GLEXG treatment improved oxidative stress of testicular tissues in OAS rat model induced by GTW. (A–B) Representative images of relative fluorescence intensity of testicular tissue ROS and the contents of ROS measured by flow cytometry in each group. (C–E) MDA, GPX4, and GSH levels in testes in each group. (F–G) Representative flow cytometry images of sperm mitochondrial membrane potential, and the levels of sperm mitochondrial membrane potential measured by flow cytometry in each group. Data are shown as the means ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 vs. the model group, respectively.

Figure 4.

GLEXG improved iron metabolism of testicular tissue in OAS rat model induced by GTW. (A–C) Levels of total, ferric and ferrous iron in each group. (D) Representative images of transmission electron microscopy of sperm mitochondria morphology in each group. White arrowheads indicate shrunken mitochondria; red arrowheads indicate cytoplasmic and organelle swelling, as well as plasma membrane rupture. Data are shown as the means ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. the model group, respectively.

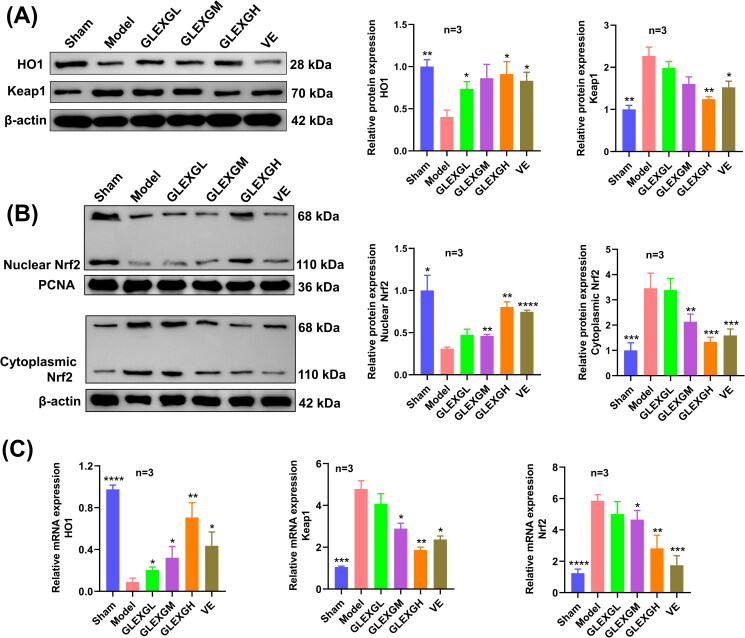

Protein and mRNA expression in Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway associated with ferroptosis

Compared with the sham group, HO1 and nuclear Nrf2 protein expression significantly decreased, while Keap1 and cytoplasmic Nrf2 protein expression increased in the model group. After GLEXG treatment, we observed an increase in HO1 and nuclear Nrf2 protein expression and a decrease in Keap1 and cytoplasmic Nrf2 protein expression. Moreover, Nrf2 and Keap1 mRNA expression significantly increased in the model group, while HO1 mRNA expression decreased. After GLEXG treatment, Nrf2 and Keap1 mRNA expression decreased and that of HO1 increased (Figure 5(A–C)).

Figure 5.

GLEXG treatment activated the Keap1/Nrf2 signaling pathway. (A) Representative gel images of Keap1 and HO1 and relative protein levels in each group. (B) Representative gel images of nuclear Nrf2 and cytoplasmic Nrf2, and relative protein levels in each group. (C) Relative mRNA expression levels of Keap1, HO1 and Nrf2 in each group. Data are shown as the means ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 vs. the model group, respectively.

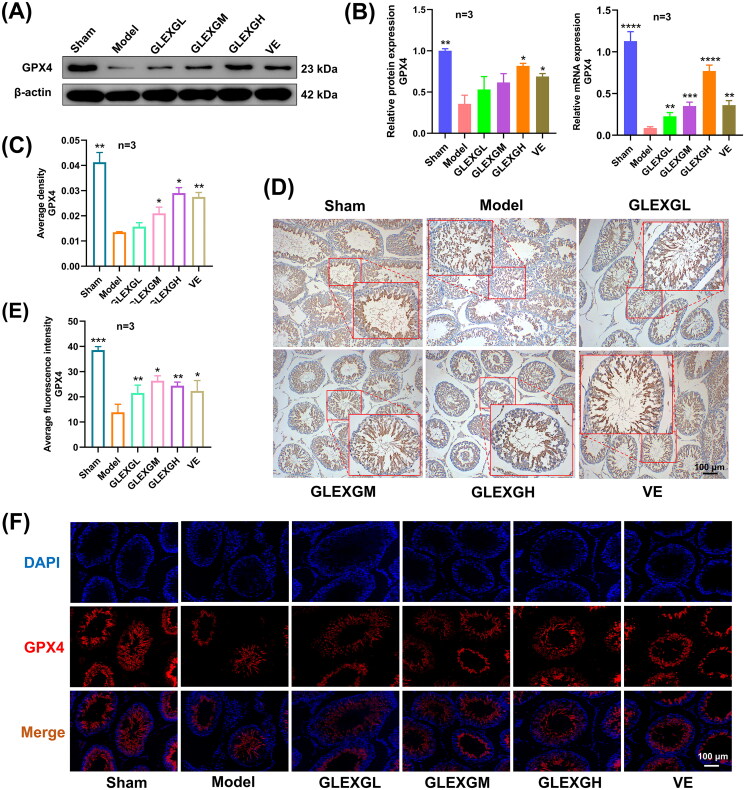

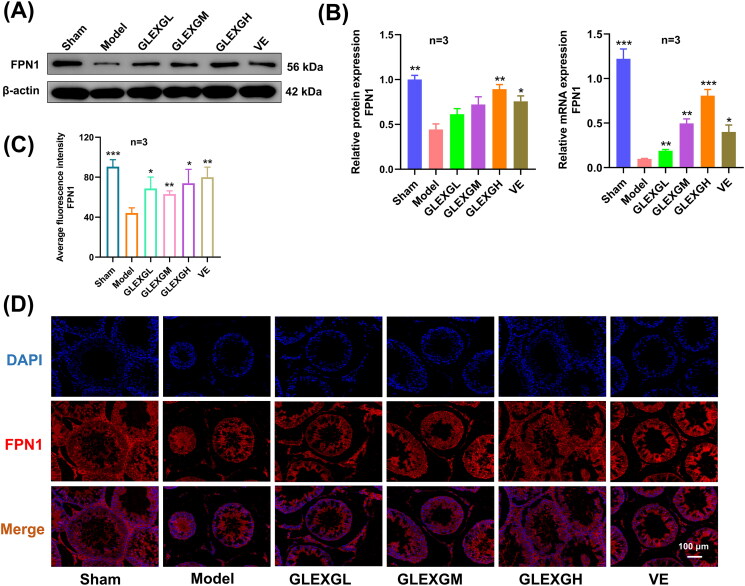

Additionally, we explored the expression of mRNA and proteins implicated in iron metabolism. In contrast with the sham group, GTW administration induced decreased protein and mRNA expression of GPX4 and FPN1. After GLEXG treatment, GPX4 and FPN1 expression significantly increased. (Figures 6(A–B) and 7(A–B)). Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis revealed that the level of GPX4 was significantly lower in the model groups compared with the sham group. After GLEXG treatment, the GPX4 level significantly increased (Figure 6(C–D)). Immunofluorescence analysis revealed that the level of GPX4 and FPN1 was extensively lower in the model group compared to the sham group. After GLEXG treatment, the GPX4 level significantly increased. (Figures 6(E–F) and 7(C–D)).

Figure 6.

GLEXG treatment improved the protein and mRNA expression of GPX4. (A) Representative gel images of GPX4 in each group. (B) Relative protein and mRNA expression levels of GPX4 in each group. (C–D) Immunohistochemical staining and quantification of GPX4 in each group. (E–F) Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification of GPX4 in each group. Data are shown as the means ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 vs. the model group, respectively.

Figure 7.

GLEXG treatment improved the protein and mRNA expression of FPN1. (A) Representative gel images of FPN1 in each group. (B) Relative protein and mRNA expression levels of FPN1 in each group. (C–D) Representative immunofluorescence images and quantification of FPN1 in each group. Data are shown as the means ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001 vs. the model group, respectively.

Discussion

Male infertility causes substantial social and psychological distress and imposes a considerable economic burden on patients and healthcare systems (Inhorn and Patrizio 2015), which remains poorly understood, and idiopathic OAS accounts for 60–75% of all cases (Barratt et al. 2017). Currently, treatment strategies against OAS remain limited. Thus, combinative therapy and the comprehensive management of OAS are urgent. Investigations involving TCM for OAS treatment have been ongoing for thousands of years. As a significant component of complementary and alternative medicine, TCM plays a crucial role in OAS treatment and is practiced worldwide. Previous animal experiments showed GLEXG to be orally applicable, very safe, and harbor low toxicity (Chou et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2020).

In this study, the chromatographic fingerprint of GLEXG was established and characterized using UPLC-Q/TOF-MS. We identified 122 compounds in positive ion mode and 66 in negative ion mode in GLEXG, indicating that GLEXG is chemically complex with hundreds or thousands of constituents. The exact chemical nature and interaction of these constituents remain still unknown. Among the compounds obtained from GLEXG, it is reported that the β-sitosterol could reduce oxidative stress in sperm, thus improving sperm counts and motility (Zhang et al. 2015). The kaempferol could significantly increase the levels of GPX, SOD in spermatozoa of rats with diabetes and reduce the levels of TNF-α, NF-κB in spermatozoa (Dobrzynska 2004; Jamalan et al. 2016). GLEXG also contains multiple amino acids, which play multiple roles in regulating cell metabolism, proliferation, and differentiation, and are involved in spermatogenesis and sperm maturation (Tosic 1947; Dai et al. 2015).

In this study, we showed that GLEXG (i) significantly improved the semen concentration, motility, and the number of mobile sperm in an OAS rat model induced by GTW; (ii) mitigated histopathological damage in the testicular tissues; (iii) improved the structure and function of sperm mitochondria; (iv) improved the level of oxidative stress and iron metabolism in testicular tissues; (v) activated the Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway to resist ferroptosis.

Ferroptosis is an atypical form of regulated cell death first proposed by Stockwell et al. (2012) and differs from autophagy, pyroptosis, apoptosis, necrosis, or other kinds of cell death studied in biochemistry, morphology, and genetics. Morphologically, ferroptosis is characterized by ruptured mitochondrial outer membranes, diminished mitochondrial cristae, and shrunken mitochondria (Dixon et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2014). The vital signatures of ferroptosis are iron dependence and aggregation of lipid ROS. Nevertheless, low ROS levels are required for various redox-sensitive physiological processes, such as sperm capacitation, insemination, as well as hyperactivation (Aitken et al. 2012). Emerging evidence shows that ROS-triggered damage to sperm contributes to 30–80% of male infertility (Guérin et al. 2001; Tremellen 2008; Bisht et al. 2017). Oxidative stress constitutes a primary cause of germ cell dysfunction given the impairment of the structural and functional integrity of spermatozoa (Aitken and Baker 2006; Agarwal et al. 2014). Previous research has indicated that excessive ROS could damage sperm membranes, thereby inhibiting sperm motility along with their ability to fuse with oocytes. High levels of ROS could also directly lead to sperm DNA lesions, compromising the paternal genomic contribution to the embryo (Agarwal et al. 2006). In this study, GTW-administered rats manifested typical features of OAS, including decreased semen concentration, motility and mobile sperm count in the epididymis, and histopathological damage in the testis. We also observed that the OAS rat model exhibited characteristic features of ferroptosis, such as increased MDA and ROS levels, decreased GSH and GPX4 levels, iron accumulation, and abnormal sperm mitochondrial morphology. We found that GLEXG treatment markedly improved the sperm quality in the model, mitigated histopathological damage in the testes and lesions in the sperm mitochondria morphology, increased the level of sperm mitochondrial membrane potential, and regulated the level of oxidative stress and iron metabolism in testicular tissue.

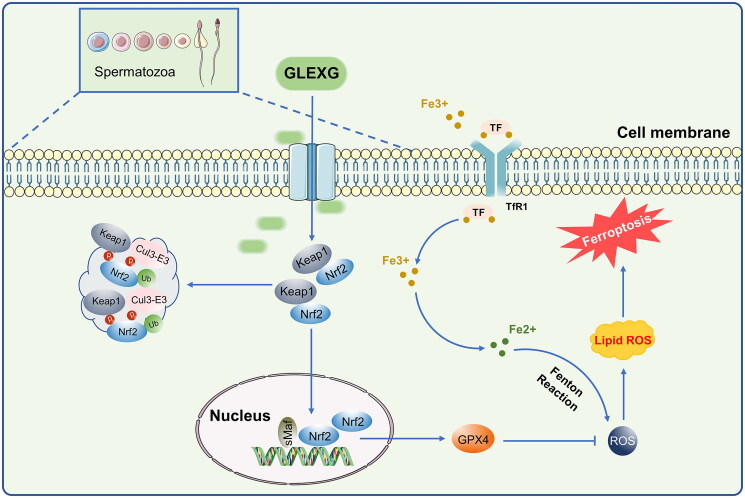

The Keap1/Nrf2 pathway is among the most remarkable defense mechanisms against oxidative stress and can regulate the redox process, maintaining cellular homeostasis (Lu et al. 2016). Keap1, a negative repressor of Nrf2, could target Nrf2 for ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation (Yamamoto et al. 2018). Nrf2 has been shown to play a crucial role in ferroptosis regulation, and the expression of Nrf2 along with its target gene, GPX4 can inhibit ferroptosis (Song and Long 2020; Takahashi et al. 2020; Ge et al. 2021). GPX4 is considered to be an indispensable modulator of ferroptosis. Repressing the activity of GPX4 or depleting GSH, the substrate of GPX4, induced ferroptosis (Yang et al. 2014). Male sperm quality and level of seminal plasma GPX4 are positively correlated (Ou et al. 2020), and low expression of GPX4 in rat testes could further influence semen concentration and motility, which could cause sperm deformity (Zhou et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2021). Nevertheless, the mechanism of GPX4-triggered male infertility remains poorly understood. Additionally, clinical investigations have demonstrated that Nrf2 mRNA levels were drastically diminished in the spermatozoa of individuals with OAS (Chen et al. 2012; Yu et al. 2013). Moreover, silencing of the Nrf2 gene in mice diminished sperm quality in an age-dependent manner, illustrating that Nrf2 has an indispensable role in spermatogenesis and maturation (Nakamura et al. 2010). Increasing evidence demonstrated that Nrf2 positively inhibits ferroptosis (Sun et al. 2016; Shin et al. 2018; Zhao et al. 2020). In this study, we demonstrated that Nrf2 and GPX4 expression significantly decreased, while Keap1 expression increased in the testes of rats with OAS induced by GTW. After GLEXG treatment, Nrf2 and GPX4 levels increased remarkably, while Keap1 expression decreased. Because ferroptosis is a newly discovered iron-dependent form of cell death, we also examined protein expression involved in iron metabolism. Specifically, FPN1 is the only iron exporter (Chen et al. 2020), and deletion of FPN1 in mice increases cellular iron burden (Zhang et al. 2011, 2012; Li et al. 2019). We established that FPN1 expression was lower in the testes of the OAS rats compared with normal rats. After GLEXG treatment, the expression of FPN1 increased significantly. Schematic representation of GLEXG resisting ferroptosis and improving semen quality via the Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway is presented in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Schematic representation of GLEXG resisting ferroptosis and improving semen quality via the Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway.

Conclusions

In this study, GLEXG improved the semen quality of an OAS rat model partially through ferroptosis resistance via the Keap1/Nrf2/GPX4 signaling pathway. These findings suggest that targeting ferroptosis could be a potential strategy for OAS therapy. In further studies, we intend to validate the underlying mechanism of ferroptosis regulated by GLEXG on mouse spermatogenic cell lines (GC-1 spg, GC-2 spd) in vitro.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all members of the andrology laboratory of the Hunan University of Chinese Medicine for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant Number: 81774324], the Open Fund Project of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine of Hunan University of Chinese Medicine [Grant Number: 2020ZXYJH29], the Fundamental Research Project of Medical and Health in Shenzhen Bao’an District [Grant Number: 2020JD505], the Key Discipline Projects of Hunan University of Chinese Medicine [Grant Number: 2021ZXYJH03], and the Dongjian Postgraduate Innovation Project of Hunan University of Chinese Medicine [Grant Number: 2021DJ03].

Author contributions

Qinghu He and Jin Ding designed and conceived the study. Jin Ding, Lumei Liu, Zixuan Zhong and Bonan Li conceived the study and drafted the manuscript. Jin Ding, Wen Sheng, Baowei Lu, and Neng Wang retrieved and analyzed the data. Qinghu He, Jin Ding, and Wen Sheng revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article.

References

- Agarwal A, Baskaran S, Parekh N, Cho C-L, Henkel R, Vij S, Arafa M, Panner Selvam MK, Shah R.. 2021. Male infertility. The Lancet. 397(10271):319–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A, Prabakaran S, Allamaneni S.. 2006. What an andrologist/urologist should know about free radicals and why. Urology. 67(1):2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A, Virk G, Ong C, Du Plessis SS.. 2014. Effect of oxidative stress on male reproduction. World J Mens Health. 32(1):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ, Baker MA.. 2006. Oxidative stress, sperm survival and fertility control. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 250(1–2):66–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ, Clarkson JS, Fishel S.. 1989. Generation of reactive oxygen species, lipid peroxidation, and human sperm function. Biol Reprod. 41(1):183–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ, Gibb Z, Mitchell LA, Lambourne SR, Connaughton HS, De Iuliis GN.. 2012. Sperm motility is lost in vitro as a consequence of mitochondrial free radical production and the generation of electrophilic aldehydes but can be significantly rescued by the presence of nucleophilic thiols. Biol Reprod. 87(5):110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt CLR, Bjorndahl L, De Jonge CJ, Lamb DJ, Osorio Martini F, McLachlan R, Oates RD, van der Poel S, St John B, Sigman M, et al. 2017. The diagnosis of male infertility: an analysis of the evidence to support the development of global WHO guidance-challenges and future research opportunities. Hum Reprod Update. 23(6):660–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisht S, Faiq M, Tolahunase M, Dada R.. 2017. Oxidative stress and male infertility. Nat Rev Urol. 14(8):470–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang Z, Qin W, Zheng H, Schegg K, Han L, Liu X, Wang Y, Wang Z, McSwiggin H, Peng H, et al. 2021. Triptonide is a reversible non-hormonal male contraceptive agent in mice and non-human primates. Nat Commun. 12(1):1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K, Mai Z, Zhou Y, Gao X, Yu B.. 2012. Low NRF2 mRNA expression in spermatozoa from men with low sperm motility. Tohoku J Exp Med. 228(3):259–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen PH, Wu J, Ding CC, Lin CC, Pan S, Bossa N, Xu Y, Yang WH, Mathey-Prevot B, Chi JT.. 2020. Kinome screen of ferroptosis reveals a novel role of ATM in regulating iron metabolism. Cell Death Differ. 27(3):1008–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WQ, Ding CF, Yu J, Wang CY, Wan LY, Hu HM, Ma JX.. 2020. Wuzi Yanzong Pill based on network pharmacology and in vivo evidence-protects against spermatogenesis disorder via the regulation of the apoptosis pathway. Front Pharmacol. 11:592827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou YJ, Chuu JJ, Peng YJ, Cheng YH, Chang CH, Chang CM, Liu HW.. 2018. The potent anti-inflammatory effect of Guilu Erxian Glue extracts remedy joint pain and ameliorate the progression of osteoarthritis in mice. J Orthop Surg Res. 13(1):259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z, Wu Z, Hang S, Zhu W, Wu G.. 2015. Amino acid metabolism in intestinal bacteria and its potential implications for mammalian reproduction. Mol Hum Reprod. 21(5):389–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Iuliis GN, Thomson LK, Mitchell LA, Finnie JM, Koppers AJ, Hedges A, Nixon B, Aitken RJ.. 2009. DNA damage in human spermatozoa is highly correlated with the efficiency of chromatin remodeling and the formation of 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine, a marker of oxidative stress. Biol Reprod. 81(3):517–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, Patel DN, Bauer AJ, Cantley AM, Yang WS, et al. 2012. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 149(5):1060–1072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobrzynska MM. 2004. Antioxidants modulate thyroid hormone-and noradrenaline-induced DNA damage in human sperm. Mutagenesis. 19(4):325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge MH, Tian H, Mao L, Li DY, Lin JQ, Hu HS, Huang SC, Zhang CJ, Mei XF.. 2021. Zinc attenuates ferroptosis and promotes functional recovery in contusion spinal cord injury by activating Nrf2/GPX4 defense pathway. CNS Neurosci Ther. 27(9):1023–1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guérin P, El Mouatassim S, Ménézo Y.. 2001. Oxidative stress and protection against reactive oxygen species in the pre-implantation embryo and its surroundings. Hum Reprod Update. 7(2):175–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen M, Kurinczuk JJ, Milne E, de Klerk N, Bower C.. 2013. Assisted reproductive technology and birth defects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 19(4):330–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Li P, Yu LH, Li L, Zhang Y, Guo Y, Long M, He JB, Yang SH.. 2018. Protective effects of proanthocyanidins against cadmium-induced testicular injury through the modification of Nrf2-Keap1 signal path in rats. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 57:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou W, Xie Y, Song X, Sun X, Lotze MT, Zeh HJ, 3rd, Kang R, Tang D.. 2016. Autophagy promotes ferroptosis by degradation of ferritin. Autophagy. 12(8):1425–1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Li B, Xu K, Liu D, Hu J, Yang Y, Nie H, Fan L, Zhu W.. 2017. Decline in semen quality among 30,636 young Chinese men from 2001 to 2015. Fertil Steril. 107(1):83–88 e82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai H, Suzuki K, Ishizaka K, Ichinose S, Oshima H, Okayasu I, Emoto K, Umeda M, Nakagawa Y.. 2001. Failure of the expression of phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase in the spermatozoa of human infertile males. Biol Reprod. 64(2):674–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inhorn MC, Patrizio P.. 2015. Infertility around the globe: new thinking on gender, reproductive technologies and global movements in the 21st century. Hum Reprod Update. 21(4):411–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamalan M, Ghaffari MA, Hoseinzadeh P, Hashemitabar M, Zeinali M.. 2016. Human sperm quality and metal toxicants: protective effects of some flavonoids on male reproductive function. Int J Fertil Steril. 10(2):215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen CFS, Østergren P, Dupree JM, Ohl DA, Sønksen J, Fode M.. 2017. Varicocele and male infertility. Nat Rev Urol. 14(9):523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang D, Coscione A, Li L, Zeng BY.. 2017. Effect of Chinese herbal medicine on male infertility. Int Rev Neurobiol. 135:297–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilchevsky A, Honig S.. 2012. Male factor infertility in 2011: semen quality, sperm selection and hematospermia. Nat Rev Urol. 9(2):68–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krausz C, Riera-Escamilla A.. 2018. Genetics of male infertility. Nat Rev Urol. 15(6):369–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzastek SC, Farhi J, Gray M, Smith RP.. 2020. Impact of environmental toxin exposure on male fertility potential. Transl Androl Urol. 9(6):2797–2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Sharma A, Kshetrimayum C.. 2019. Environmental & occupational exposure & female reproductive dysfunction. Indian J Med Res. 150(6):532–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Dong L, Wang J, Sun S, Wang B, Li H.. 2020. Effects of Zuogui Wan on testis structure and expression of c-Kit and Oct4 in rats with impaired spermatogenesis. Pharm Biol. 58(1):44–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Jiang L, Chew SH, Hirayama T, Sekido Y, Toyokuni S.. 2019. Carbonic anhydrase 9 confers resistance to ferroptosis/apoptosis in malignant mesothelioma under hypoxia. Redox Biol. 26:101297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu MC, Ji JA, Jiang ZY, You QD.. 2016. The Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway as a potential preventive and therapeutic target: an update. Med Res Rev. 36(5):924–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura BN, Lawson G, Chan JY, Banuelos J, Cortes MM, Hoang YD, Ortiz L, Rau BA, Luderer U.. 2010. Knockout of the transcription factor NRF2 disrupts spermatogenesis in an age-dependent manner. Free Radic Biol Med. 49(9):1368–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omar MI, Pal RP, Kelly BD, Bruins HM, Yuan Y, Diemer T, Krausz C, Tournaye H, Kopa Z, Jungwirth A, et al. 2019. Benefits of empiric nutritional and medical therapy for semen parameters and pregnancy and live birth rates in couples with idiopathic infertility: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol. 75(4):615–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou Z, Wen Q, Deng Y, Yu Y, Chen Z, Sun L.. 2020. Cigarette smoking is associated with high level of ferroptosis in seminal plasma and affects semen quality. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 18(1):55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie C, Ko EY.. 2021. Oxidative stress in the pathophysiology of male infertility. Andrologia. 53(1):e13581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin D, Kim EH, Lee J, Roh JL.. 2018. Nrf2 inhibition reverses resistance to GPX4 inhibitor-induced ferroptosis in head and neck cancer. Free Radic Biol Med. 129:454–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song X, Long D.. 2020. Nrf2 and ferroptosis: a new research direction for neurodegenerative diseases. Front Neurosci. 14:267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockwell BR, Friedmann Angeli JP, Bayir H, Bush AI, Conrad M, Dixon SJ, Fulda S, Gascon S, Hatzios SK, Kagan VE, et al. 2017. Ferroptosis: a regulated cell death nexus linking metabolism, redox biology, and disease. Cell. 171(2):273–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Ou Z, Chen R, Niu X, Chen D, Kang R, Tang D.. 2016. Activation of the p62-Keap1-NRF2 pathway protects against ferroptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Hepatology. 63(1):173–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N, Cho P, Selfors LM, Kuiken HJ, Kaul R, Fujiwara T, Harris IS, Zhang T, Gygi SP, Brugge JS.. 2020. 3D culture models with CRISPR screens reveal hyperactive NRF2 as a prerequisite for spheroid formation via regulation of proliferation and ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 80(5):828–844 e826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamburrino L, Marchiani S, Montoya M, Elia Marino F, Natali I, Cambi M, Forti G, Baldi E, Muratori M.. 2012. Mechanisms and clinical correlates of sperm DNA damage. Asian J Androl. 14(1):24–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosic J. 1947. Mechanism of hydrogen peroxide formation by spermatozoa and the role of amino-acids in sperm motility. Nature. 159(4042):544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremellen K. 2008. Oxidative stress and male infertility – a clinical perspective. Hum Reprod Update. 14(3):243–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velasquez M, Tanrikut C.. 2014. Surgical management of male infertility: an update. Transl Androl Urol. 3(1):64–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villaverde A, Netherton J, Baker MA.. 2019. From past to present: the link between reactive oxygen species in sperm and male infertility. Antioxidants. 8(12):616–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Ying YY, Chen ZH, Shao KD, Zhang WP, Lin SY.. 2020. Guilu Erxian Glue inhibits chemotherapy-induced bone marrow hematopoietic stem cell senescence in mice may via p16(INK4a)-Rb signaling pathway. Chin J Integr Med. 26(11):819–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Zhan S, Liu Y, Han F, Shi L, Han C, Mu W, Cheng J, Huang ZW.. 2021. Low-Se diet can affect sperm quality and testicular glutathione peroxidase-4 activity in rats. Biol Trace Elem Res. 199(10):3752–3758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X, Xu H, Shang Y, Zhu R, Hong X, Song Z, Yang Z.. 2021. Development of the general chapters of the Chinese Pharmacopoeia 2020 edition: a review. J Pharm Anal. 11(4):398–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Kensler TW, Motohashi H.. 2018. The KEAP1-NRF2 system: a thiol-based sensor-effector apparatus for maintaining redox homeostasis. Physiol Rev. 98(3):1169–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WS, SriRamaratnam R, Welsch ME, Shimada K, Skouta R, Viswanathan VS, Cheah JH, Clemons PA, Shamji AF, Clish CB, et al. 2014. Regulation of ferroptotic cancer cell death by GPX4. Cell. 156(1–2):317–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Chen J, Liu D, Zhou H, Xiao W, Xia X, Huang Z.. 2013. Cigarette smoking is associated with human semen quality in synergy with functional NRF2 polymorphisms. Biol Reprod. 89(1):5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zegers-Hochschild F, Adamson GD, Dyer S, Racowsky C, de Mouzon J, Sokol R, Rienzi L, Sunde A, Schmidt L, Cooke ID, et al. 2017. The international glossary on infertility and fertility care, 2017. Hum Reprod. 32(9):1786–1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Bao X, Zhang M, Zhu Z, Zhou L, Chen Q, Zhang Q, Ma B.. 2019. MitoQ ameliorates testis injury from oxidative attack by repairing mitochondria and promoting the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 370:78–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Song M, Rui X, Pu S, Li Y, Li C.. 2015. Supplemental dietary phytosterin protects against 4-nitrophenol-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in rat testes. Toxicol Rep. 2:664–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zhang F, An P, Guo X, Shen Y, Tao Y, Wu Q, Zhang Y, Yu Y, Ning B, et al. 2011. Ferroportin1 deficiency in mouse macrophages impairs iron homeostasis and inflammatory responses. Blood. 118(7):1912–1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z, Zhang F, Guo X, An P, Tao Y, Wang F.. 2012. Ferroportin1 in hepatocytes and macrophages is required for the efficient mobilization of body iron stores in mice. Hepatology. 56(3):961–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Liu Z, Gao J, Li H, Wang X, Li Y, Sun F.. 2020. Inhibition of ferroptosis attenuates busulfan-induced oligospermia in mice. Toxicology. 440:152489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou JC, Zheng S, Mo J, Liang X, Xu Y, Zhang H, Gong C, Liu XL, Lei XG.. 2017. Dietary selenium deficiency or excess reduces sperm quality and testicular mRNA abundance of nuclear glutathione peroxidase 4 in rats. J Nutr. 147(10):1947–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou SH, Deng YF, Weng ZW, Weng HW, Liu ZD.. 2019. Traditional Chinese medicine as a remedy for male infertility: a review. World J Mens Health. 37(2):175–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article.