Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to provide the clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and 5-year relative survival rates of lung cancer diagnosed in 2015.

Materials and Methods

The demographic risk factors of lung cancer were calculated using the KALC-R (Korean Association of Lung Cancer Registry) cohort in 2015, with survival follow-up until December 31, 2020. The 5-year relative survival rates were estimated using Ederer II methods, and the general population data used the death rate adjusted for sex and age published by the Korea Statistical Information Service from 2015 to 2020.

Results

We enrolled 2,657 patients with lung cancer who were diagnosed in South Korea in 2015. Of all patients, 2,098 (79.0%) were diagnosed with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and 345 (13.0%) were diagnosed with small cell lung cancer (SCLC), respectively. Old age, poor performance status, and advanced clinical stage were independent risk factors for both NSCLC and SCLC. In addition, the 5-year relative survival rate declined with advanced stage in both NSCLC (82%, 59%, 16%, 10% as the stage progressed) and SCLC (16%, 4% as the stage progressed). In patients with stage IV adenocarcinoma, the 5-year relative survival rate was higher in the presence of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation (19% vs. 11%) or anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) translocation (38% vs. 11%).

Conclusion

In this Korean nationwide survey, the 5-year relative survival rates of NSCLC were 82% at stage I, 59% at stage II, 16% at stage III, and 10% at stage IV, and the 5-year relative survival rates of SCLC were 16% in cases with limited disease, and 4% in cases with extensive disease.

Keywords: Lung neoplasms, Epidemiology, Korea, Relative survival rate

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of death worldwide. In Korea, although the mortality of patients with lung cancer has decreased in recent years [1], the mortality rate remains high, regardless of sex [2].

With the development of various therapeutic modalities, such as immunotherapy and targeted therapy, the overall lung cancer survival rate, which has been stagnant for decades, has improved [3]. However, although the 5-year survival rates in lung cancer varied depending on the clinical stage, all stages have low 5-year survival rates of only around 22% [4]. Especially in the United States, among patients diagnosed with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) from 2011 to 2017, the 5-year relative survival rate was 26% in all stages and only 8% in cases with distant metastases. Small cell lung cancer (SCLC) had a substantially lower 5-year relative survival rate of approximately 7% for the same time period [5].

Several studies have suggested that race and geography may have a role in lung cancer mortality [6]. According to recent domestic data, the 5-year lung cancer relative survival rate is reported as 63.7% in male and 84.3% in female for localized stage, in addition, 7.0% in male and 13.4% in female for distant stage [2]; however, there have been no large samples of domestic data on how the histopathologic subtype, clinical staging, and prognostic factors affect the 5-year survival rate of lung cancer.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the clinical characteristics and prognostic factors for the 5-year overall survival in patients with lung cancer using data from the KA-LC-R (Korean Association of Lung Cancer Registry) from 2015.

Materials and Methods

1. Study design and subjects

This study analyzed data from the KALC-R cohort—the second nationwide survey, a multi-center cancer Registry from 64 institutions with more than 400 beds in Korea [7]. In 2015, the KALC registered 2,657 patients who were newly diagnosed with lung cancer. The KALC-R has approximately 80 data fields comprising demographic data. Data on patient age, sex, body mass index (BMI), symptoms, smoking history, performance status (PS), histopathologic type, clinical stage (according to the eighth edition of the TNM International Staging System), initial treatment modality, results of molecular tests (i.e., epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR] mutation and anaplastic lymphoma kinase [ALK] translocation) were collected using a standardized protocol. Information such as BMI, symptoms, and smoking history was obtained at the initial visit at the time of diagnosis. Patients were followed up until December 2020.

2. Statistical analysis

Relative survival was developed to provide an objective assessment of cancer survival while accounting for disparities in mortality from other causes. Relative survival was defined as the ratio of the observed survival of a cohort of patients with cancer to the expected survival of a comparable group of cancer-free individuals. The relative survival rates were estimated using the Ederer II method, with some minor corrections based on an algorithm devised by Paul Dickman [8]. The 5-year relative survival rate was defined as the ratio of the observed survival of patients with cancer to the expected survival in the general population. The general population data used the source data for the death rate per 100,000 people adjusted for sex and age from 2015 to 2020, published by the Korea Statistical Information Service [9].

Data are expressed as the mean±standard deviation or median (interquartile range [IQR]). The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables, and the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Cox proportional hazards models were used to investigate mortality risk factors. Variables with a p-value < 0.20 on univariate analysis were used in multivariate analysis. Survival was analyzed by the Kaplan-Meier method. All p-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software ver. 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

1. Baseline characteristics

We enrolled a total of 2,657 patients with lung cancer who were diagnosed in South Korea in 2015. Of all patients, 2,098 (79.0%) were diagnosed with NSCLC and 345 (13.0%) were diagnosed with SCLC.

Patients diagnosed with NSCLC were analyzed by dividing them into survivor and non-survivor group (Table 1). Among the 2,098 patients with NSCLC, 1,446 (68.9%) died and 652 (31.1%) survived during the follow-up period. The median patient age was significantly older (70.0 [IQR, 62.0 to 76.0 years] vs. 65.0 [IQR, 57.0 to 72.0 years], p < 0.001) in the non-survivor group. The proportions of male sex (75.4% vs. 57.2%, p < 0.001) and ever-smoker status (67.5% vs. 54.0%, p < 0.001) were significantly higher in the non-survivor group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with NSCLC in 2015

| Total | Non-survivor | Survivor | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 2,098 | 1,446 (68.9) | 652 (31.1) | |

| Male sex | 1,464 (69.8) | 1,091 (75.4) | 373 (57.2) | < 0.001 |

| Age (yr) | 69.0 (60.0–75.0) | 70.0 (62.0–76.0) | 65.0 (57.0–72.0) | < 0.001 |

| Ever-smoker | 1,328 (63.3) | 976 (67.5) | 352 (54.0) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 23.0 (22.2–24.1) | 22.9 (21.6–24.2) | 23.4 (23.1–23.8) | 0.402 |

| Symptoms | 2,062 | 1,419 | 643 | |

| Asymptomatic | 322 (15.6) | 127 (8.9) | 195 (30.3) | < 0.001 |

| Cough | 697 (33.8) | 548 (38.6) | 149 (23.2) | < 0.001 |

| Sputum | 406 (19.7) | 310 (21.8) | 96 (15.0) | < 0.001 |

| Dyspnea | 374 (18.1) | 320 (22.6) | 54 (8.4) | < 0.001 |

| Hoarseness | 47 (2.3) | 42 (3.0) | 5 (0.8) | 0.002 |

| Hemoptysis | 128 (6.2) | 100 (7.0) | 28 (4.4) | 0.020 |

| Weight loss | 116 (5.6) | 94 (6.6) | 22 (3.4) | 0.004 |

| Pain | 381 (18.5) | 320 (22.6) | 61 (9.5) | < 0.001 |

| Histopathology | 2,098 | 1,446 | 652 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 1,308 (62.3) | 810 (56.0) | 498 (76.4) | < 0.001 |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 662 (31.6) | 522 (36.1) | 140 (21.5) | < 0.001 |

| Others | 247 (11.8) | 208 (14.4) | 39 (6.0) | < 0.001 |

| Performance status | 1,550 | 1,029 | 521 | < 0.001 |

| 0–1 | 1,371 (88.5) | 862 (83.8) | 511 (98.1) | |

| 2–4 | 177 (11.4) | 167 (16.2) | 10 (1.9) | |

| Clinical stage of NSCLC | 1,818 | 1,243 | 575 | < 0.001 |

| I | 390 (21.5) | 91 (7.3) | 299 (52.0) | |

| II | 261 (14.4) | 122 (9.8) | 139 (24.2) | |

| III | 653 (35.9) | 559 (45.0) | 94 (16.3) | |

| IV | 514 (28.3) | 471 (37.9) | 43 (7.5) |

Values are presented as the number (%) or median (interquartile range). BMI, body mass index; NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer.

Regarding the histopathology, adenocarcinoma was the leading subtype (62.3%) in patients with NSCLC, and adenocarcinoma was more common (56.0% vs. 76.4%, p < 0.001) in the survivor group. In addition, the proportions of patients with early-stage (stage I or II) NSCLC (17.1% vs. 76.2%, p < 0.001) and good PS (83.8% vs. 98.1%, p < 0.001) were higher in the survivor group.

Among the 345 patients diagnosed with SCLC in 2015, 321 (93.0%) died and only 24 (7.0%) survived during the follow-up period (Table 2). There were no significant differences in male sex (84.7% in non-survivor vs. 83.3% in survivor group, p=0.854), ever-smoker status (83.5% vs. 87.5%, p=0.381), BMI (25.9 vs. 22.5, p=0.166), subjective symptoms, and good PS (83.6% vs. 87.5%, p=0.681) between the two groups. The median patient age was significantly older (72.0 [IQR, 63.0 to 77.0 years] vs. 67.5 [IQR, 60.0 to 71.0 years], p=0.023), and the proportion of extended disease (63.9% vs. 33.3%, p=0.004) was significantly higher in the non-survivor group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of patients with SCLC in 2015

| Total | Non-survivor | Survivor | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of patients | 345 | 321 | 24 | |

| Male sex | 292 (84.6) | 272 (84.7) | 20 (83.3) | 0.854 |

| Age (yr) | 71.0 (63.0–76.0) | 72.0 (63.0–77.0) | 67.5 (60.0–71.0) | 0.023 |

| Ever-smoker | 289 (83.8) | 268 (83.5) | 21 (87.5) | 0.381 |

| BMI (kg/m 2 ) | 25.6 (22.4–30.0) | 25.9 (22.2–30.9) | 22.5 (20.0–24.3) | 0.166 |

| Symptoms | 342 | 318 | 24 | |

| Asymptomatic | 20 (5.8) | 18 (5.7) | 2 (8.3) | 0.581 |

| Cough | 157 (45.9) | 146 (45.9) | 11 (45.8) | 0.973 |

| Sputum | 99 (28.9) | 95 (29.9) | 4 (16.7) | 0.177 |

| Dyspnea | 108 (31.6) | 103 (32.4) | 5 (20.8) | 0.251 |

| Hoarseness | 11 (3.2) | 10 (3.1) | 1 (4.2) | 0.777 |

| Hemoptysis | 19 (5.6) | 17 (5.3) | 2 (8.3) | 0.529 |

| Weight loss | 31 (9.1) | 31 (9.7) | 0 | 0.111 |

| Pain | 62 (18.1) | 61 (19.2) | 1 (4.2) | 0.068 |

| Performance status | 272 | 256 | 16 | 0.681 |

| 0–1 | 228 (83.8) | 214 (83.6) | 14 (87.5) | |

| 2–4 | 44 (16.2) | 42 (16.4) | 2 (12.5) | |

| Clinical stage of SCLC | 345 | 321 | 24 | 0.004 |

| LD | 122 (35.4) | 106 (33.0) | 16 (66.7) | |

| ED | 213 (61.7) | 205 (63.9) | 8 (33.3) | |

| Unknown | 10 (2.9) | 10 (3.1) | 0 |

Values are presented as the number (%) or median (interquartile range). BMI, body mass index; ED, extensive disease; LD, limited disease; SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

2. Initial treatment methods

The initial treatment modalities of NSCLC patients was presented in S1 Table. In the survivor group, the proportion of surgery was higher than that of the non-survivor group (8.0% in non-survivor group vs. 67.6% in survivor group, p < 0.001). In the non-survivor group, the proportion of radiotherapy (10.0% vs. 4.4%, p < 0.001), concurrent chemoradiation therapy (14.1% vs. 5.5%, p < 0.001), chemotherapy (19.2% vs. 8.9%, p < 0.001), and best supportive care (31.1% vs. 6.3%, p < 0.001) was higher than that of the survivor group. Treatment for each clinical stage in the NSCLC was presented in S2 Table.

The initial treatment modalities of SCLC patients was presented in S3 Table. In SCLC, there was no statistical difference in each treatment methods between survivor and non-survivor groups.

3. Prognostic factor

In total, 2,098 patients with NSCLC were followed up for a median of 20.5 months (IQR, 6.0 to 61.0 months). Univariate Cox analysis showed that old age (hazard ratio [HR], 1.032; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.027 to 1.038; p < 0.001), male sex (HR, 1.714; 95% CI, 1.520 to 1.933; p < 0.001), ever-smoker status (HR, 1.490; 95% CI, 1.332 to 1.667; p < 0.001), poor PS (HR, 3.172; 95% CI, 2.681 to 3.753; p < 0.001), higher clinical stage (HR, 8,574; 95% CI, 6.836 to 10.754; p < 0.001; stage IV compared to stage I), squamous cell carcinoma (HR, 1.648; 95% CI, 1.476 to 1.841; p < 0.001) histopathology compared to adenocarcinoma, and non-surgical treatment (HR 6.889; 95% CI, 5.708 to 8.314; p < 0.001) or best supportive care (HR, 10.232; 95% CI, 8.399 to 12.466; p < 0.001) compared to surgery were significant predictors of mortality. On multivariate Cox analysis in these variables, except for male sex and ever-smoker status, remained significant prognostic factors (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk factors for mortality in patients with NSCLC assessed by Cox proportional hazards model

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Age | 1.032 | 1.027–1.038 | < 0.001 | 1.019 | 1.012–1.025 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Male sex | 1.714 | 1.520–1.933 | < 0.001 | 1.222 | 0.985–1.516 | 0.069 |

|

| ||||||

| Ever-smoker | 1.490 | 1.332–1.667 | < 0.001 | 1.112 | 0.899–1.375 | 0.327 |

|

| ||||||

| BMI | 0.998 | 0.995–1.002 | 0.444 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Performance status | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 0–1 (ref) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| 2–4 | 3.172 | 2.681–3.753 | < 0.001 | 1.995 | 1.655–2.405 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Clinical stage | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| I (ref) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| II | 2.434 | 1.855–3.194 | < 0.001 | 1.530 | 1.084–2.159 | 0.016 |

|

| ||||||

| III | 7.801 | 6.241–9.750 | < 0.001 | 3.263 | 2.407–4.423 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| IV | 8.574 | 6.836–10.754 | < 0.001 | 3.829 | 2.814–5.211 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Histology | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma (ref) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1.648 | 1.476–1.841 | < 0.001 | 1.203 | 1.033–1.402 | 0.018 |

|

| ||||||

| Treatment | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Surgery (ref) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| Non-surgical treatment | 6.889 | 5.708–8.314 | < 0.001 | 3.814 | 2.968–4.902 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Best supportive care | 10.232 | 8.399–12.466 | < 0.001 | 5.189 | 3.945–6.826 | < 0.001 |

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; NSCLC, non smallcell lung cancer.

The 345 patients with SCLC were followed up for a median 7 months (IQR, 3 to 16 months). Univariate and multivariate Cox analyses showed that older age, ever-smoker status, poor PS, and extensive stage were significant predictors of mortality (Table 4). There was no significant difference in survival rate according to the treatment methods.

Table 4.

Risk factors for mortality in patients with SCLC assessed by Cox proportional hazards model

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-value | Hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Age | 1.042 | 1.028–1.056 | < 0.001 | 1.041 | 1.026–1.057 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Male sex | 1.079 | 0.796–1.463 | 0.622 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Ever-smoker | 0.685 | 0.504–0.929 | 0.015 | 0.736 | 0.509–1.062 | 0.101 |

|

| ||||||

| BMI | 1.000 | 0.997–1.004 | 0.787 | |||

|

| ||||||

| Performance status | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 0–1 (ref) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| 2–4 | 1.943 | 1.391–2.714 | < 0.001 | 1.838 | 1.305–2.587 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Clinical stage | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| LD (ref) | 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||

|

| ||||||

| ED | 1.961 | 1.542–2.493 | < 0.001 | 2.144 | 1.636–2.810 | < 0.001 |

|

| ||||||

| Treatment | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Anti-cancer treatment (ref) | 1.000 | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Best supportive care | 1.160 | 0.924–1.455 | 0.200 | |||

BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; ED, extensive disease; LD, limited disease; SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

4. Survival analysis

The 5-year actual survival rates of patients with NSCLC was 0.78 for stage I, 0.55 for stage II, 0.15 for stage III, and 0.10 for stage IV. In addition, in patients with SCLC was 0.15 in those with limited disease, and 0.04 in patients with extensive disease.

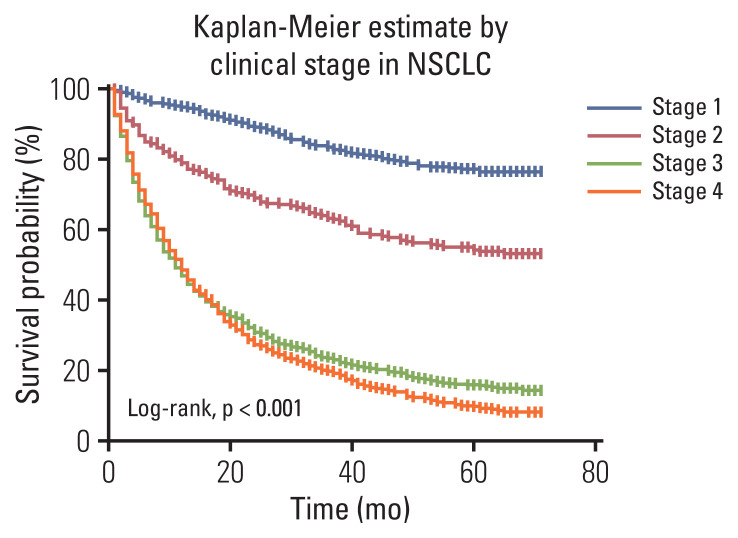

In the Kaplan-Meier survival curve according to clinical stage of NSCLC, as determined by the eighth edition of TNM, advanced stage demonstrated worse survival probability (Fig. 1). The 5-year relative survival rates of patients with NSCLC was 0.82 for stage I, 0.59 for stage II, 0.16 for stage III, and 0.10 for stage IV (Table 5).

Fig. 1.

Overall survival in patients with non–small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), according to clinical stage.

Table 5.

Five-year relative survival rates of patients with NSCLC according to stage at lung cancer diagnosis

| Stage | Time (yr) | No. at risk | No. of deaths | Observed survival ratea) | Expected survival rateb) | Relative survival (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.0–1.0 | 390 | 19 | 0.95 | 0.99 | 0.96 (0.93–0.98) |

| 1.0–2.0 | 371 | 22 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.91 (0.88–0.94) | |

| 2.0–3.0 | 349 | 22 | 0.84 | 0.97 | 0.87 (0.82–0.90) | |

| 3.0–4.0 | 327 | 16 | 0.80 | 0.96 | 0.83 (0.79–0.87) | |

| 4.0–5.0 | 311 | 9 | 0.78 | 0.94 | 0.82 (0.77–0.86) | |

| 2 | 0.0–1.0 | 261 | 54 | 0.79 | 0.98 | 0.80 (0.75–0.85) |

| 1.0–2.0 | 207 | 26 | 0.69 | 0.97 | 0.72 (0.65–0.77) | |

| 2.0–3.0 | 181 | 15 | 0.64 | 0.95 | 0.67 (0.60–0.73) | |

| 3.0–4.0 | 166 | 16 | 0.57 | 0.94 | 0.61 (0.55–0.67) | |

| 4.0–5.0 | 150 | 7 | 0.55 | 0.92 | 0.59 (0.53–0.66) | |

| 3 | 0.0–1.0 | 653 | 349 | 0.47 | 0.98 | 0.47 (0.43–0.51) |

| 1.0–2.0 | 304 | 105 | 0.30 | 0.97 | 0.31 (0.28–0.35) | |

| 2.0–3.0 | 199 | 52 | 0.23 | 0.96 | 0.24 (0.20–0.27) | |

| 3.0–4.0 | 147 | 27 | 0.18 | 0.94 | 0.20 (0.16–0.23) | |

| 4.0–5.0 | 120 | 21 | 0.15 | 0.92 | 0.16 (0.14–0.19) | |

| 4 | 0.0–1.0 | 514 | 262 | 0.49 | 0.98 | 0.50 (0.45–0.54) |

| 1.0–2.0 | 252 | 112 | 0.27 | 0.97 | 0.28 (0.24–0.32) | |

| 2.0–3.0 | 140 | 42 | 0.19 | 0.95 | 0.20 (0.17–0.24) | |

| 3.0–4.0 | 98 | 30 | 0.13 | 0.94 | 0.14 (0.11–0.17) | |

| 4.0–5.0 | 68 | 19 | 0.10 | 0.92 | 0.10 (0.08–0.13) |

CI, confidence interval; NSCLC, non small cell lung cancer.

Observed survival rate: probability of survival all causes of death in Korean Association of Lung Cancer Registry patients,

Expected survival rate: probability of expected survivors in a comparable cohort of cancer-free general population.

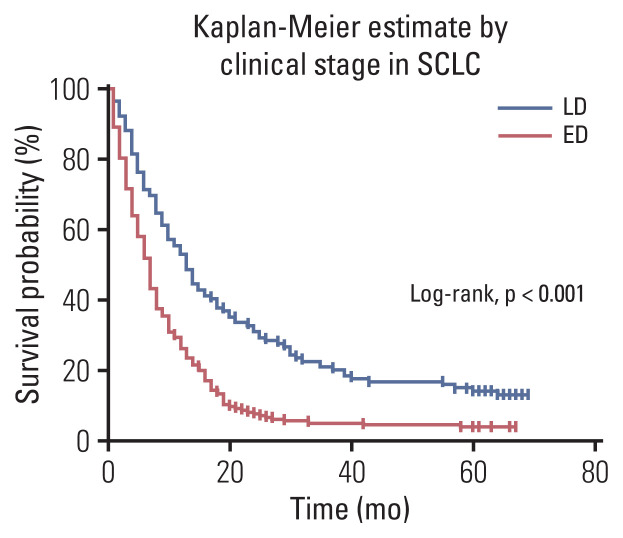

In the Kaplan-Meier survival curve according to the SCLC clinical stage, the extensive stage demonstrated worse survival probability (Fig. 2). The 5-year relative survival rates of patients with SCLC was 0.16 in those with limited disease, and 0.04 in patients with extensive disease (Table 6).

Fig. 2.

Overall survival in patients with small cell lung cancer (SCLC), according to clinical stage. ED, extensive disease; LD, limited disease.

Table 6.

Five-year relative survival rates of patients with SCLC according to stage at lung cancer diagnosis

| Stage | Time (yr) | No. at risk | No. of deaths | Observed survival ratea) | Expected survival rateb) | Relative survival (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LD | 0.0–1.0 | 122 | 56 | 0.54 | 0.98 | 0.55 (0.49–0.64) |

| 1.0–2.0 | 66 | 27 | 0.32 | 0.97 | 0.33 (0.25–0.42) | |

| 2.0–3.0 | 39 | 14 | 0.20 | 0.96 | 0.21 (0.14–0.29) | |

| 3.0–4.0 | 25 | 5 | 0.16 | 0.95 | 0.17 (0.11–0.25) | |

| 4.0–5.0 | 20 | 2 | 0.15 | 0.94 | 0.16 (0.10–0.23) | |

| ED | 0.0–1.0 | 213 | 156 | 0.27 | 0.98 | 0.27 (0.21–0.33) |

| 1.0–2.0 | 57 | 41 | 0.08 | 0.97 | 0.08 (0.05–0.12) | |

| 2.0–3.0 | 16 | 6 | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.05 (0.03–0.08) | |

| 3.0–4.0 | 10 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.95 | 0.04 (0.02–0.08) | |

| 4.0–5.0 | 9 | 1 | 0.04 | 0.95 | 0.04 (0.02–0.07) |

CI, confidence interval; ED, extensive disease; LD, limited disease; SCLC, small cell lung cancer.

Observed survival rate: probability of survival all causes of death in Korean Association of Lung Cancer Registry patients,

Expected survival rate: probability of expected survivors in a comparable cohort of cancer-free general population.

5. Subgroup analysis in patients with stage IV adenocarcinoma

Among the 348 patients with stage IV adenocarcinoma at diagnosis, 310 patients (89.1%) died and 38 patients (10.9%) survived. There were no significant differences in sex, age, ever-smoker status, BMI, subjective symptoms, and PS bet-ween the two groups. EGFR mutation status was analyzed in 304 patients (87.4%), and 118 patients (38.8%) had mutations. ALK translocation was analyzed in 233 patients (67.0%), and 19 patients (8.2%) showed ALK translocation. The ALK translocation frequency (5.7% vs. 29.2%, p < 0.001) was significantly higher in the survival group (S4 Table). The 348 patients with stage IV adenocarcinoma were followed up for a median of 14 months (IQR, 6 to 37 months). On univariate Cox analysis, older age (HR, 1.023; 95% CI, 1.013 to 1.022; p < 0.001), male sex (HR, 1.439; 95% CI, 1.143 to 1.812; p=0.002), ever-smoker status (HR, 1.405; 95% CI, 1.122 to 1.760; p=0.003), poor PS (HR, 2.327; 95% CI, 1.630 to 3.323; p < 0.001), EGFR mutation (HR, 0.651; 95% CI, 0.508 to 0.834; p < 0.001), and ALK translocation (HR, 0.442; 95% CI, 0.246 to 0.792; p=0.006) were associated with mortality. On multivariate Cox analysis, ever-smoker status (HR, 1.756; 95% CI, 1.080 to 2.855; p=0.023), poor PS (HR, 1.675; 95% CI, 1.082 to 2.594; p=0.021), and treatment with EGFR inhibitor (HR, 0.468; 95% CI, 0.262 to 0.835; p=0.010) remained significant independent predictors of mortality (S5 Table).

In the Kaplan-Meier survival curve according to the EGFR mutation and ALK translocation in stage IV adenocarcinoma, better survival probability was observed when EGFR or ALK was expressed (S6 Fig.). The 5-year relative survival rate was 0.11 in the EGFR-negative group, and 0.19 in the EGFR mutation group. In addition, the 5-year relative survival rates were 0.11 in the negative ALK group, and 0.38 in the ALK translocation group.

Discussion

In this nationwide survey, 2,657 patients with newly diagnosed with lung cancer in 2015 were followed up for a median of 16 months (IQR, 4 to 60 months). Among the included patients, 69.0% of patients with NSCLC and 93% of patients with SCLC died. The 5-year relative survival rates of NSCLC were 82% at stage I, 59% at stage II, 16% at stage III, and 10% at stage IV, while those of SCLC were 16% for patients with limited disease, and 4% for patients with extensive disease. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first nationwide-based study in Korea to focus on the 5-year survival of patients with lung cancer.

The KALC-R was created in 2013 to produce unbiased and reliable demographic data, following which, the data were collected annually. According to a previous study that analyzed the epidemiology and characteristics of patients with lung cancer in Korea using the KALC-R data in 2014 [10], adenocarcinoma (48.4%) was the most common histopathology type and was more common in women (74.8% vs. 38.0%, p < 0.001). In addition, more than 1/3 of patients with lung cancer had no smoking history, and the proportion of never-smokers was higher in women (87.5% vs. 16.0%, p < 0.001). In all histopathological types, old age and advanced clinical stage were significant risk factors for mortality. In our study, old age, poor PS, advanced clinical stage, squamous cell carcinoma compared to adenocarcinoma, and non-surgical treatment or best supportive care compared to surgery were independent prognostic factors in NSCLC, which is comparable to the findings of previous studies [11]. It is well known that old age is an important prognostic factor of NSCLC, and females have a better prognosis at a similar age and clinical stage than men [12]. In a large study that analyzed 2,500 patients, age < 70 years, female sex, and good PS were important factors that were predictive of favorable survival rate [13]. Additionally, in a previous systematic review, stage III and IV, and hypercalcemia were predictive factors in NSCLC [11]. In a Japanese lung cancer Registry survey over a 15-year period [14], PS, clinical stage, sex, age, and smoking status were all independent prognostic variables for survival in NSCLC. Recent data have shown that nutritional status and BMI are related to the prognosis of NSCLC, although further research is necessary.

In SCLC, old age, poor PS, and extensive disease were independent prognostic factors in our study. Previous studies reported that old age, male sex, and lower education level were associated with increased mortality of SCLC [15]. In another Korean single-center study [16], the extent of disease and PS were independent prognostic factors for long-term survival of SCLC. Compared to anti-cancer treatment, best supportive care showed no significant difference in prognosis, which is thought to be due to the poor prognosis of SCLC, resulting in a small number of survivors (< 25 patients) (S5 Table). Conventional chemotherapy with immunotherapy such as atezolizumab has recently been used for the treatment of SCLC in clinical practice, and efforts to identify biomarkers are ongoing [17]. Further research is needed on the factors responsible for improving the survival rate of SCLC.

In our study, the 5-year relative survival rate of stage III NSCLC was 16%, which was lower than in previous studies [18]. Recently, durvalumab maintenance treatment followed by chemotherapy was demonstrated favorable outcome in stage III NSCLC patients, with the 5-year survival rate 42.9% and progression-free survival was 33.1% in PACIFIC trial [19]. In our current study, patients were enrolled in 2015 year, before durvalumab was established as a treatment, this might be the reason for the survival difference. Further large-scale studies with stage III NSCLC patients who received durvalumab will be needed in near future.

According to clinical stage, differences in survival rate were identified in both NSCLC and SCLC in the present study. In particular, the 8th edition of the TNM classification was revised in 2017. By subdividing T staging than the 7th edition was found to be a superior predictor of prognosis in early stage lung cancer [20]. We used the 8th edition of the TNM classification for analysis in the present study. In particular, the 5-year relative survival rate was useful for identifying temporal trends in population-based cancer research [21], and may be beneficial for presenting survival rates by stage. In the past 40 years, the 5-year relative survival rate of lung cancer had gradually increased from 10.7% in 1973 to 19.8% in 2010 [22]. Between 2011 and 2017, according to the SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) cancer statistics data [5], the 5-year relative survival rate was 26% in NSCLC and 7% in SCLC. In addition, the relative survival rate of lung cancer was gradually increased over time in Korea [23]. According to the Korea National Cancer Innovation Database, the 5-year relative survival rate was 32.4% from 2014 to 2018 [2]. It will be possible to evaluate the time-trend of lung cancer survival rate by age, sex, and staging in Korea by using the KALC-R data every year, which might serve as a reference value for the epidemiology of lung cancer in Korea.

In the present study, poor PS and EGFR mutation status were independent prognostic factors of stage IV adenocarcinoma. According to the SEER database, male sex, ≥ 65 years, and poor familial support were poor prognostic factors for the overall survival of metastatic lung adenocarcinoma [24]. As previously shown, EGFR mutation was a strong predictive factor for metastatic lung adenocarcinoma. A previous study reported the 5-year survival rate of advanced NSCLC as being < 5% [25], but 14.6% among EGFR mutated metastatic lung adenocarcinoma [26]. In our analysis, the median survival was 58 months in the EGFR mutant group, which was comparable to that of previous studies of over 24 months [27].

There were several limitations in our study. First, this study had a retrospective study design in Korea. However, we believe this data was representative and reduced selection bias because the subjects were recruited from multi-centers and comprised approximately 10% of all lung cancer patients nationwide. Second, the progression-free survival rates could not be analyzed. Third, subgroup analysis could not be performed due to the lack of detailed information on the type of treatment method according to each stage, additional treatment after initial treatment, and treatment after recurrence or metastasis. Indeed, there were few preliminary data, such as initial treatment approaches, and the comprehensive sub-analysis had certain limitations. Fourth, although the large-scale nationwide-based data, the socioeconomic status, and education level were not included in our data, so it was not possible to analyze the effects of these factors on the prognosis of lung cancer. Despite these limitations, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first nationwide study in Korea to focus on the 5-year relative survival of lung cancer.

In this Korean nationwide survey, the 5-year relative survival rate of NSCLC was between 10% and 82%, while that of SCLC was from 4% to 16% according to clinical stage. Our study is valuable as a baseline reference value because it was analyzed based on large-scale domestic data and might be served for basis and trend analysis from future research.

Acknowledgments

The data used in this study were provided by the Korean Association for Lung Cancer (KALC) and the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Korea Central Cancer Registry (KCCR).

Footnotes

Ethical Statement

The KALC was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the National Cancer Center (approval number: NCC2018-0193). The requirement for informed consent was waived by the IRB due to the retrospective nature of the study. All methods were conducted in accordance with the relevant guidelines.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the analysis: Jeon DS, Kim HC, Choi CM.

Collected the data: Jeon DS, Kim HC, Kim TJ, Kim HK, Moon MH, Beck KS, Suh YG, Song C, Ahn JS, Lee JE, Lim JU, Jeon JH, Jung KW, Jung CY, Cho JS, Choi YD, Hwang SS, Choi CM.

Contributed data or analysis tools: Jeon DS, Kim HC, Kim SH, Kim TJ, Kim HK, Moon MH, Beck KS, Suh YG, Song C, Ahn JS, Lee JE, Lim JU, Jeon JH, Jung KW, Jung CY, Cho JS, Choi YD, Hwang SS, Choi CM.

Performed the analysis: Jeon DS, Kim HC, Kim SH, Choi CM.

Wrote the paper: Jeon DS, Kim HC, Choi CM.

Conflicts of Interest

Conflict of interest relevant to this article was not reported.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Supplementary materials are available at Cancer Research and Treatment website (https://www.e-crt.org).

References

- 1.Park S, Choi CM, Hwang SS, Choi YL, Kim HY, Kim YC, et al. Lung cancer in Korea. J Thorac Oncol. 2021;16:1988–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong S, Won YJ, Lee JJ, Jung KW, Kong HJ, Im JS, et al. Cancer statistics in Korea: incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence in 2018. Cancer Res Treat. 2021;53:301–15. doi: 10.4143/crt.2021.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bar J, Urban D, Amit U, Appel S, Onn A, Margalit O, et al. Long-term survival of patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer over five decades. J Oncol. 2021;2021:7836264. doi: 10.1155/2021/7836264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7–33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Cancer Institute . SEER*Stat Database. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2021. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong MC, Lao XQ, Ho KF, Goggins WB, Tse SL. Incidence and mortality of lung cancer: global trends and association with socioeconomic status. Sci Rep. 2017;7:14300. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14513-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim YC, Won YJ. The development of the Korean Lung Cancer Registry (KALC-R) Tuberc Respir Dis. 2019;82:91–3. doi: 10.4046/trd.2018.0032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dickman PW, Coviello E. Estimating and modeling relative survival. Stata J. 2015;15:186–215. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Statistics Korea [Internet] Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2020. [cited 2022 May 30]. Available from: https://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/index.action . [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi CM, Kim HC, Jung CY, Cho DG, Jeon JH, Lee JE, et al. Report of the Korean Association of Lung Cancer Registry (KALC-R), 2014. Cancer Res Treat. 2019;51:1400–10. doi: 10.4143/crt.2018.704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brundage MD, Davies D, Mackillop WJ. Prognostic factors in non-small cell lung cancer: a decade of progress. Chest. 2002;122:1037–57. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.3.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sachs E, Sartipy U, Jackson V. Sex and survival after surgery for lung cancer: a Swedish nationwide cohort. Chest. 2021;159:2029–39. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albain KS, Crowley JJ, LeBlanc M, Livingston RB. Survival determinants in extensive-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: the Southwest Oncology Group experience. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1618–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.9.1618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawaguchi T, Takada M, Kubo A, Matsumura A, Fukai S, Tamura A, et al. Performance status and smoking status are independent favorable prognostic factors for survival in non-small cell lung cancer: a comprehensive analysis of 26,957 patients with NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:620–30. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d2dcd9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou K, Shi H, Chen R, Cochuyt JJ, Hodge DO, Manochakian R, et al. Association of race, socioeconomic factors, and treatment characteristics with overall survival in patients with limited-stage small cell lung cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2032276. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.32276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong S, Cho BC, Choi HJ, Jung M, Lee SH, Park KS, et al. Prognostic factors in small cell lung cancer: a new prognostic index in Korean patients. Oncology. 2010;79:293–300. doi: 10.1159/000323333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hiddinga BI, Raskin J, Janssens A, Pauwels P, Van Meerbeeck JP. Recent developments in the treatment of small cell lung cancer. Eur Respir Rev. 2021;30:210079. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0079-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoon SM, Shaikh T, Hallman M. Therapeutic management options for stage III non-small cell lung cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2017;8:1–20. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v8.i1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spigel DR, Faivre-Finn C, Gray JE, Vicente D, Planchard D, Paz-Ares L, et al. Five-year survival outcomes from the PACIFIC trial: durvalumab after chemoradiotherapy in stage III non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:1301–11. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yun JK, Lee GD, Kim HR, Kim YH, Kim DK, Park SI, et al. Validation of the 8th edition of the TNM staging system in 3,950 patients with surgically resected non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:2955–64. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2019.07.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akhtar-Danesh N, Finley C. Temporal trends in the incidence and relative survival of non-small cell lung cancer in Canada: a population-based study. Lung Cancer. 2015;90:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu T, Yang X, Huang Y, Zhao M, Li M, Ma K, et al. Trends in the incidence, treatment, and survival of patients with lung cancer in the last four decades. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:943–53. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S187317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin A, Oh CM, Kim BW, Woo H, Won YJ, Lee JS. Lung cancer epidemiology in Korea. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49:616–26. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campos-Balea B, de Castro Carpeno J, Massuti B, Vicente-Baz D, Perez Parente D, Ruiz-Gracia P, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma: an analysis of the SEER database. Thorac Cancer. 2020;11:3357–64. doi: 10.1111/1759-7714.13681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giroux Leprieur E, Lavole A, Ruppert AM, Gounant V, Wislez M, Cadranel J, et al. Factors associated with long-term survival of patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Respirology. 2012;17:134–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin JJ, Cardarella S, Lydon CA, Dahlberg SE, Jackman DM, Janne PA, et al. Five-year survival in EGFR-mutant metastatic lung adenocarcinoma treated with EGFR-TKIs. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:556–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.12.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang CY, Chen BH, Chou WC, Yang CT, Chang JW. Factors associated with the prognosis and long-term survival of patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma: a retrospective analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2018;10:2070–8. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.03.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.