Abstract

The quality index method (QIM) is a widely accepted solution to establish the state of fish freshness quickly and effectively. The present study aims to determine increasingly reliable freshness parameters for fresh and whole Lophius piscatorius stored in ice. Sensory and microbiological analyses were performed on 148 anglerfishes. Sensory evaluations were performed based on the QIM, updating a previously proposed quality index (QI) scheme. Total viable count and specific spoilage organisms were determined through microbiological analyses of the tail musculature, evaluating their correlations with the QI scores over time. The updated QI scheme included 3 characters, namely appearance, eye, and fin, for a total of 18 demerits points. A positive linear correlation between QI score and storage time was observed such that the sensory rejection time (8th day) can be predicted within ± 1 day with the developed scheme. At the sensory rejection point, loads of the spoilage microbial flora were not high enough to be relatable to the appreciated alterations probably due to the anglerfish morphology in which the tail musculature is isolated from the gills and viscera, the main sources of bacterial contamination. The proposed scheme offers a ready-to-use freshness assessment of the anglerfish although further validations are needed.

Keywords: Lophius piscatorius, Quality index method, Sensory analysis, Spoilage bacteria

Introduction

The freshness loss of seafood is the result of biochemical, physicochemical, and microbiological post-mortem processes, influenced by handling on board and technological processing (Giuffrida et al. 2013; Giarratana et al. 2020). To date, sensory evaluation is the most suitable approach for a rapid freshness assessment of seafood according to the mandatory requirements established by Regulation (EC) No. 853/04. In this regard, food business operators must carry out an organoleptic examination of fishery products placed on the market for human consumption, ensuring compliance with any freshness criteria. Over time, several methods and protocols were implemented to assess seafood freshness and quality (Prabhakar et al. 2020). Technological advances led to the development of artificial intelligence (electronic nose, electronic tongue, and computer vision systems) able to measure and characterize the aroma, taste, and colours of food replacing the human senses (Tretola et al. 2017). However, the high costs and the analyses’ time do not allow the application of these tools for routine analysis. The grading scheme described in Regulation (EC) No. 2406/96 is currently adopted in the European Union to evaluate the freshness of seafood, rating in different freshness categories. However, only certain products or groups of products are considered and differences in ice storage of the various species are not entirely clarified since only general parameters are used (Regulation (EC) No. 2406/96). Nowadays, an alternative method increasingly adopted for sensory estimation of fishery products is the Quality index method (QIM). Proposed for the first time by the Tasmanian Food Research Unit (Bremner 1985), QIM ascribes demerit points to a descriptor set of different parameters, from 0 to 3 adjusted to the evaluated species (Bernardo et al. 2020). The single scores are added up to obtain an overall sensory score, the Quality Index (QI), that increase when freshness decrease. The advantage of QIM is the possibility of setting up and considering different parameters for each evaluated species; moreover, the minor differences for any criterion do not unduly influence the total QI score and the relative judgment of freshness (Esteves and Aníbal 2021). During the last decades, QIM was developed for several species and products, especially for those of most commercial value (Esteves and Aníbal et al. 2021). In a previous study (Pennisi et al. 2011), we have proposed a QI scheme for whole fresh Anglerfish (Lophius piscatorius—Linneo, 1758) consisting of 12 parameters related to 7 characters for a total of 23 demerit points, speculating on a maximum storage time on ice of 8 days. A linear correlation between QI score, the time of storage in ice, and H2S-producing bacteria counts had been found. Lophius piscatorius is a fish of high commercial value, marketed fresh or frozen, whole or headless, consumed and appreciated worldwide for the high organoleptic and nutritional quality of its lean meat. Commonly known as monkfish or anglerfish, it is a bony fish belonging to the teleost order (Lophiiformes) that inhabits sandy and stony bottom waters between 20 and 1000 m deep, widely spread in the Mediterranean Sea, the Black Sea, and Eastern Atlantic, from Norway to Senegal (Duarte et al. 2001). The name anglerfish comes from its predating behaviour whereby a fleshy outgrowth from its head (the esca or illicium) acts as a lure. During the last decades, various European and national strategy frameworks promoted the need to invest in new aquaculture species to increase the competitiveness of the sector industry (Bostock et al. 2016). To overcome the productivity dependence on farmed sea bream and sea bass of the European market, L. piscatorius was proposed among the main candidate species for new aquaculture breeding in the Mediterranean basin (Quéméner et al. 2002; Llorente et al. 2020). As autochthonous species, anglerfish farming allows a more sustainable approach to expanding the aquaculture productions making high-quality products more accessible to a wider market. Nowadays, the freshness rating of anglerfish is based on the scheme proposed by Regulation (EC) 2406/96 which establishes parameters only for headed fish. In this regard, the evaluation of the outline and colour of the blood vessels and surrounding muscles is required, parameters that cannot be evaluated in whole fish. Therefore, considering the growing economic and commercial value of the anglerfish, the present study is a contribution to determining increasingly reliable freshness parameters for fresh and whole L. piscatorius, by rephrasing and improving the QI scheme proposed in our previous study (Pennisi et al. 2011). In this regard, a shelf-life study of raw and whole anglerfish stored in ice was performed, correlating microbiological analysis results to data of a sensory evaluation.

Materials and methods

Anglerfish samples’ collection

The sampling occurred from April 2016 to September 2017 involving five different batches of fish for a total of 148 L. piscatorius caught along the Adriatic coast of the Abruzzo region (Italy). The weight of the tested fishes ranged between 588 and 1460 g with a mean value of ~ 860 ± 181 g while their length from the mouth to the tail ranged from 25 to 47 cm with a mean value of ~ 34 ± 5 cm. The fishes were packed in expanded polystyrene boxes with perforated bottoms, covered by a plastic film, surrounded by ice flakes, and transported to the laboratory of the University of Teramo (Teramo, Italy) within 1–2 h of harvesting. Once in the laboratory, each specimen was individually stored in a box under the same conditions described above and kept at refrigeration temperature (~ 2 ± 1 °C). The use of perforated boxes and the plastic layer covering the fish ensured that the water from the melted ice was properly drained remaining separated from the fish. The temperature of each box has been recorded with a data logger Smart-Vue™ 868 MHz SV204-101-LSB (Thermo fisher, Monza, Italy) set with a sampling frequency of 20 min to control significant fluctuations that could have influenced the sensory and microbiological parameters of the fishes. The flaked ice was daily added to the boxes as required.

Improvement and development of the QI scheme

Following guidelines for sensory evaluation for fish species proposed by Martinsdòttir et al. (2001) and Hyldig et al. (2007), five people (two women and three men) were involved in improving the previous QI scheme. All members had previously trained in developing and using fish QI schemes according to ISO 5492:2008 and ISO 8586-1:1993. Starting from the QI scheme of the previous work (Pennisi et al. 2011) with 23 demerit points, a new QI scheme was preliminary designed through the sensory analysis of 58 whole anglerfish specimens. The sensory analyses were daily performed by two sensory experts until the reaching of sensory rejection for all the samples. The anglerfishes were randomly collected from the boxes, placed on white plates for 30 min at room temperature, and then observed under a white light regime. Each sample was not washed with tap water before the presentation to panellists, since Huidobro et al. (2001) reported that it could influence the sensory quality of some species. The parameters to be used in the sensory analysis were chosen considering the previously developed QI scheme and according to ISO 11035:1994. In this regard, the major observed changes related to the general appearance, eyes, and fins, were used to establish parameters and relative descriptors for the new QI scheme. The score of each descriptor ranged from 0 to 3, with the higher demerit points (3) assigned to the most distinctive negative changes (Hyldig et al. 2007). Six 1-h sessions were used for the development of the scheme and training of the QIM sensory panel prior to the shelf-life study. The preliminary scheme was explained to the panellists during the first 2 days while observing anglerfish of varying freshness. During the evaluations, all comments and suggestions made by the panellists were considered by the panel leader to improve the new QI scheme by considering as few parameters as possible. Then the panellists were trained for the following 4 days and the scheme developed further. The storage time of each fish was unknown to the panellists until after the session. The ultimate version of the scheme was finalized by the panel leader and presented to the panel on the last day of training. For attributes that do not present four clear degradation stages, the score was attributed according to the stage that was clearly present when the fish was rejected during the trials.

Validation of the new QI scheme

The new version of the QI scheme was prepared by the panel leader and disclosed to the panellists. The sensory analysis of the remaining 90 anglerfishes was carried out as described above to validate and fix the new QI scheme. The specimens were split into 3 batches and daily analysed in triplicate until the time of sensory rejection. Immediately after each sensory evaluation, three fishes from each batch (for a total of 9 fishes) were daily subjected to microbiological analysis as described below.

Microbiological analysis

Flesh samples from each anglerfish were collected and analysed to determine the Total Viable Counts (TVC) and Specific Spoilage Organisms (SSOs). In detail, the portions of flesh sampled were aseptically collected from the epiaxial musculature immediately after the pectoral fins with the aid of scissors and tweezers, first removing the skin and ~ 1 cm of muscle and sampling the underlying portions. A total of ~ 10 g of muscle was weighed in a stomacher bag and diluted with peptone saline diluent (MRD—Oxoid Ltd., UK) in a ratio of 1:9 (w/v) at room temperature. The samples were then homogenized for 120 s at 230 rpm with a stomacher (Stomacher® 400 Circulator; International PBI s.p.a., Milan, Italy) and tenfold dilutions were prepared in peptone water as needed. The TVC was carried out on Standard Plate Count Agar (PCA, Oxoid Ltd., UK) by the pour plate technique according to ISO 4833-1:2013. The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 48 h. The SSO counts were carried out on Lingby Iron Agar (IA) by the pour plate technique with an overlay as described by Gram et al. (1987). The plates were incubated at 22 °C for 3 days. The H2S-producing bacteria (black colonies) and H2S-nonproducing bacteria (white colonies) grown in IA were identified by Gram staining, catalase and oxidase test, and micro-method screening with API 20 NE (bioMérieux SA, Marcy l’Etoile, France). Furthermore, the obtained identifications were confirmed with matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectroscopy (MALDI-TOF MS). These analyses were performed in the Food Inspection Laboratory of the Department of Veterinary Sciences at the University of Messina (Messina, Italy), according to Trabelsi et al. (2021). In this regard, a Vitek MS Axima Assurance mass spectrometer (bioMerieux, Firenze, Italy) was used in positive linear mode, with a laser frequency of 50 Hz, an acceleration voltage of 20 kV, and an extraction delay time of 200 ns. The mass spectra range was set to detect from 2000 to 20,000 Da. MALDI-TOF generated unique MS spectra for each tested colony that was transferred into the SARAMIS software (Spectral ARchive and Microbial Identification System—Database version V4.12—Software year 2013, bioMerieux, Firenze, Italy) and compared to the database of reference bacteria spectra and SuperSpectra.

Data analysis

The total QI scores and the results of the microbiological analyses were submitted to time-dependent linear regression analysis, also evaluating any potential correlation between them. The equation of the best fit and coefficient of determination (R2) of each regression were calculated by XL Stat (2010) software package. The observed and predicted values by linear regression were used to estimate the uncertainty (Standard Error of Estimate) of the QI prediction by testing the predictability of the QI scheme by partial least-squares regression (PLS). The microbiological results were expressed as colony-forming units per grams (CFU/g) of musculature.

Results and discussions

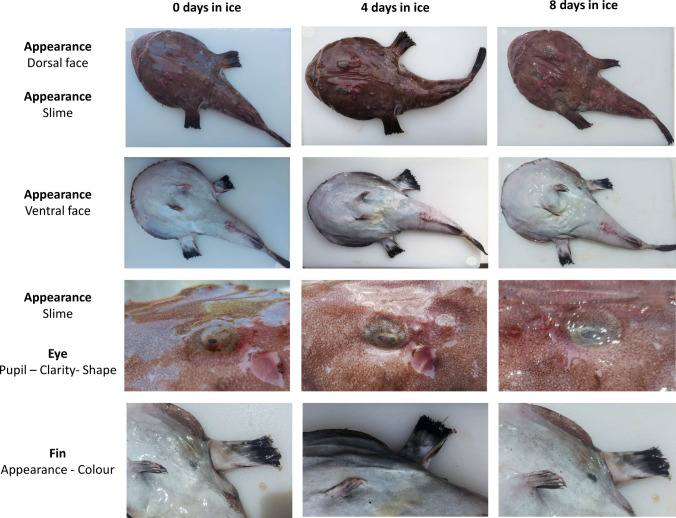

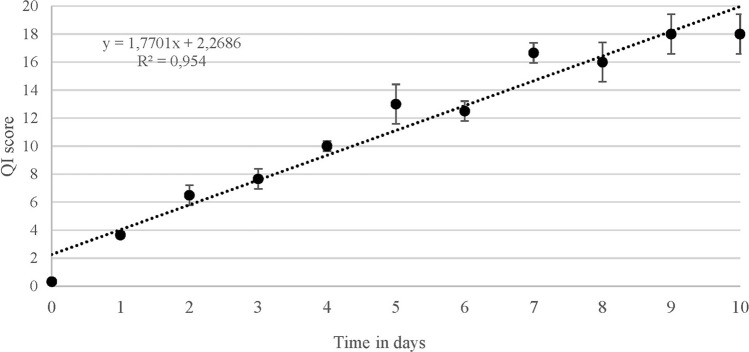

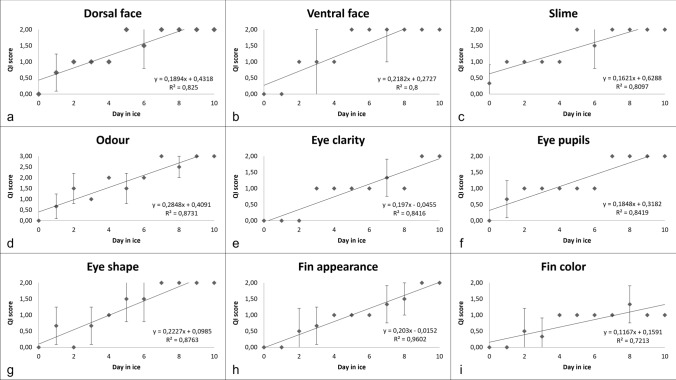

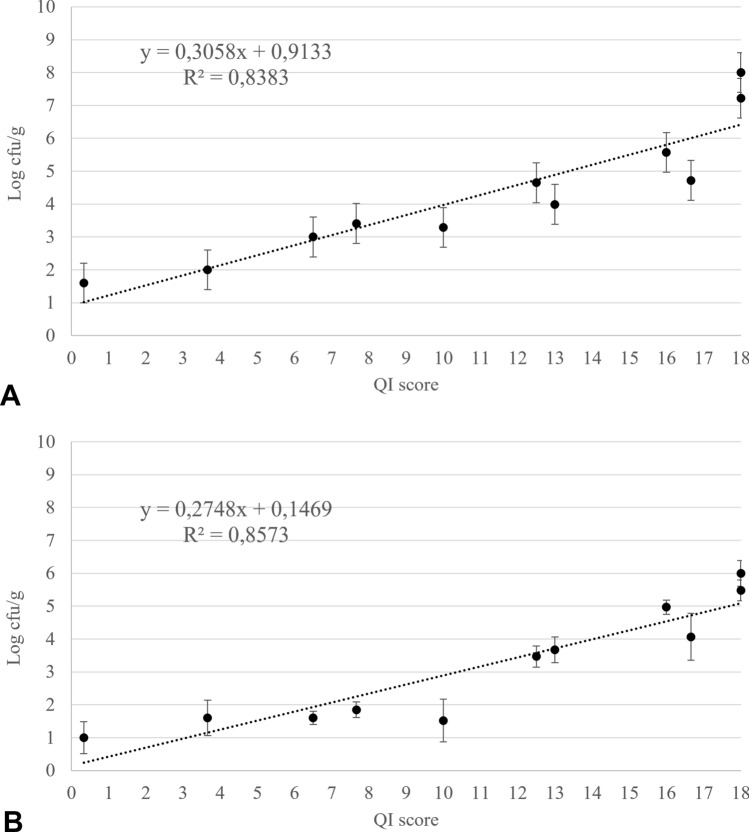

In a previous study (Pennisi et al. 2011), we developed a QI scheme for fresh anglerfish stored in ice consisting of 12 parameters related to 7 characters for a total of 23 demerit points. In the present study, the QI scheme was streamlined by excluding parameters that could not be assessed quickly and including only those whose changes were the same in all samples throughout the trial. In this regard, gills were no longer considered a suitable parameter since they were not easily and quickly observable within gill slits. Changes in texture (elasticity) and appearance of the anal region were also excluded as they proved to be fickle. The new revision of the QI scheme developed for the fresh and whole anglerfish stored in ice included 9 parameters relating to three main characters, namely appearance, eye, and fins, for a maximum demerit score of 18 points (Table 1). Among the changes in the appearance, the loss of brightness of dorsal and ventral faces, the clouding of the skin slime and the development of off-odours were appreciated in all the fish examined. The loss of brightness and hydration of the eye resulting in clouding and sinking was also constantly detected during storage as well as progressive dehydration of the fins and the subsequent appearance of a reddish colour on the margins. Figure 1 shows the changes in each character considered that occurred up to the time of sensory rejection. A positive linear relationship was observed between the QI score and the storage time (Fig. 2) such that the storage time of the anglerfish may be predicted within ± 1 day by using the implemented QI scheme. The demerit scores of each parameter also tended to increase linearly during storage but a greater correlation was found considering the total QI score rather than that of the individual parameters, except for the appearance of the fins (Fig. 3). Based on the sensory analysis, the shelf-life limit of the anglerfish stored in ice corresponded to the 8th day with a QI score of 16 points. It was the odour that compromised the general acceptability of the fish even if the other parameters were still acceptable. At the beginning of the test, the odour was described as fresh or seaweed and then became neutral as the days passed (starting from the 2nd to 3rd day). Around the fifth day, the odour was defined as fishy and then increased in intensity until it became unpleasant (off-odour) establishing the end of the shelf-life after 8 days. The occurrence of off-odours in fresh fish is mostly related to the metabolism of spoilage bacteria which use fish tissues as an energy source leading to the formation of ammonia, biogenic amines, organic acids, and sulphur compounds responsible for unpleasant odours (Cortesi et al. 2009; Zhuang et al. 2021). Therefore, understanding the relationship between sensory decay and microbial behaviour during storage is certainly desirable. At time 0, an average value of 1.60 ± 0.38 Log CFU/g was detected for TVC of the flesh samples, which is not unusual for newly caught fish (Ward and Hackney 2012), up to reaching average loads of 8.00 ± 0.45 Log CFU/g after 10 days of storage (Fig. 4a). The H2S-producing bacteria represented a low part of the starting microflora (1.00 ± 0.48 Log CFU/g) but significantly increased during storage up to a mean value of 6.00 ± 0.39 Log CFU/g after 10 days (Fig. 4b). Loads of H2S non-producing bacteria remained constantly low over time reaching the maximum value of 1.47 ± 0.22 Log CFU/g around the 5th day. Overall, loads of TVC and H2S-producing bacteria steadily increased during fish storage, unlike H2S-non-producing bacteria whose growth was overwhelmed by that of H2S-producing bacteria. Indeed, as confirmed by the identification tests, the H2S-producing bacteria were the dominant flora of flesh of the analysed anglerfishes at the time of sensory rejection. Through the biochemical screening tests and MALDI-TOFF analysis, most of the H2S-producing bacteria and TVC colonies were identified as Shewanella spp. (such as S. algae and S. putrefaciens) and Citrobacter spp., while the most H2S-nonproducing bacteria were identified as Pseudomonas spp. and Pseudomonas fluorescens. These identifications are consistent with several previous studies (Anagnostopoulos et al. 2022) concerning fish caught in temperate waters in which the appearance of offensive fishy, rotten, and H2S-off-odours are typical spoilage. Interestingly, although the growth of TVC and H2S-producing bacteria was in good agreement with the QI scores throughout the trial (Fig. 5), the bacterial loads detected for anglerfish flesh at the sensory rejection time (8th day) were considerably lower than those reported for other fishes stored in ice (Bernardo et al. 2020; Boziaris and Parlapani 2017). In this regard, average values of 4.97 ± 0.22 Log CFU/g were detected after 8 days of storage for SSOs while it is known that spoilage of fishery products is usually associated with higher loads (Log > 6–7 CFU/g) (Cortesi et al. 2009). However, these results are not surprising given the typical behaviour of the spoilage flora of fresh fish and the anglerfish anatomy. Overall, the flesh contamination of fresh fish occurs secondary to the irruption of microorganisms from other districts such as gills, digestive tract, and skin, which being in contact with the environment, are the main bacterial sources (Boziaris and Parlapani 2017; Arab et al. 2020). We could speculate that the microbial loads observed in the tail musculature, the portion usually consumed, were probably lower than those of other anatomical parts at the rejection time due to the morphology of the anglerfish, in which the gills and the digestive tract are mainly in the cranial region of the fish. This is also the reason for the differences that could be observed with other fishes in which microbial growth evolves more homogeneously throughout the body. These divergences between sensory decay and microbial loads could indicate that either the proposed QI scheme underestimates the results of the microbiological analysis or that flesh microbiology is not the best indicator of spoilage for whole anglerfish. Similar results were obtained by Vázquez-Sánchez et al. (2020) who found that mesophilic and psychotropic populations on tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) stored at 1 °C did not even reach 4 Log CFU/g at the time of sensory rejection (13th day). On this background, the evaluation of physico-chemical rather than microbiological parameters, such as k value, total volatile basic nitrogen, and thiobarbituric acid-reactive substances, could be useful to consolidate the findings of the present study and, as already carried out by other authors, to validate the QI scores and sensory rejection (Bernardo et al. 2020).

Table 1.

Quality index scheme proposed for fresh and whole anglerfish (Lophius piscatorius) stored in ice

| Character | Parameter | Descriptor | Demerit point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | Dorsal face | Very bright | 0 |

| Bright | 1 | ||

| Dull | 2 | ||

| Ventral face | Milky white/pink spread | 0 | |

| Off-white/pink spread | 1 | ||

| Off-white/grey spots | 2 | ||

| Slime | Clear/transparent | 0 | |

| Slightly cloudy | 1 | ||

| Cloudy | 2 | ||

| Odour | Fresh seaweed | 0 | |

| Neutral | 1 | ||

| Fishy | 2 | ||

| Off odours | 3 | ||

| Eye | Pupil | Bright black | 0 |

| Greyish black/less brilliant | 1 | ||

| Gray/milky | 2 | ||

| Clarity | Clear-translucent | 0 | |

| Slight opaque | 1 | ||

| Opaque | 2 | ||

| Shape | Convex | 0 | |

| Flat | 1 | ||

| Concave | 2 | ||

| Fin | Appearance | Hydrated | 0 |

| Apical part slightly dehydrated | 1 | ||

| Dehydrated | 2 | ||

| Colour | Pigmented | 0 | |

| Red halo on margins | 1 | ||

| Total QIM score 0–18 | |||

Fig. 1.

Changes occurring in Lophius piscatorius during 8 days of ice storage relative to the character considered in the QI scheme proposed in the present study

Fig. 2.

Average values of the QI scores for fresh and whole specimens of anglerfish (Lophius piscatorius) over each day of storage in ice

Fig. 3.

Average QI scores over time of different freshness descriptors (dorsal face a, ventral face b, slime c, odour d, eye clarity e, eye pupil f, eye shape g, fin appearance h, and fin colour i) assessed with the QI scheme proposed in the present study for fresh and whole anglerfish (Lophius piscatorius) stored in ice

Fig. 4.

Average loads over time of Total Viable Count A and H2S-producing bacteria B in the tail musculature of fresh specimens of whole anglerfishes (Lophius piscatorius) stored in ice

Fig. 5.

Correlation between the QI scores of fresh specimens of whole anglerfishes (Lophius piscatorius) and the average loads of the Total Viable Count A and H2S-producing bacteria B detected in the tail musculature of the fishes

Conclusion

In the present study, a QI scheme was developed for the fresh and whole L. piscatorius stored in ice consisting of 9 parameters related to 3 characters, resulting in a total of 18 demerit points. The proposed scheme offers a ready-to-use freshness assessment of the anglerfish providing detailed information on its sensory qualities and residual shelf-life. A positive linear relationship between QI score and storage time in ice was observed such that the time of sensory rejection (8th day) can be predicted within ± 1 day with the developed QI scheme. Loads of the SSOs in the tail musculature were still acceptable at the time of sensory rejection established by the implemented QI scheme stressing the need to consider further and different parameters for its validation.

Abbreviations

- QIM

Quality index method

- QI

Quality index

- MALDI

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- H2S

Hydrogen sulphide

- EC

European council

- ISO

International organization for standardization

- TVC

Total viable counts

- SSOs

Specific spoilage organisms

- MRD

Maximum recovery diluent

- w/v

Water/volume

- PLS

Partial least-squares

- CFU

Colony forming units

Author contributions

LP and FG: conceived the study designed. LP performed the experiment. FG, LN and ARDR: analysed the data. FG and LN: drafted and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Anagnostopoulos DA, Parlapani FF, Boziaris IS. The evolution of knowledge on seafood spoilage microbiota from the 20th to the 21st century: have we finished or just begun? Trends Food Sci Technol. 2022;120:236–247. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2022.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arab S, Nalbone L, Giarratana F, Berbar A. Occurrence of Vibrio spp. along the algerian Mediterranean coast in wild and farmed Sparus aurata and Dicentrarchus labrax. Vet World. 2020;13:1199. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2020.1199-1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernardo YA, Rosario DK, Delgado IF, Conte-Junior CA. Fish quality index method: principles, weaknesses, validation, and alternatives—a review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2020;19:2657–2676. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostock J, Lane A, Hough C, Yamamoto K. An assessment of the economic contribution of EU aquaculture production and the influence of policies for its sustainable development. Aquac Int. 2016;24:699–733. doi: 10.1007/s10499-016-9992-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boziaris IS, Parlapani FF. Food science, technology and nutrition. Cambridge: Woodhead Publishing; 2017. Specific spoilage organisms (SSOs) in fish, in the microbiological quality of food; pp. 61–98. [Google Scholar]

- Bremner HA. A convenient easy to use system for estimating the quality of chilled seafood. Fish Process Bull. 1985;7:59–70. [Google Scholar]

- Cortesi ML, Panebianco A, Giuffrida A, Anastasio A. Innovations in seafood preservation and storage. Vet Res Commun. 2009;33:15–23. doi: 10.1007/s11259-009-9241-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duarte R, Azevedo M, Landa J, Pereda P. Reproduction of anglerfish (Lophius budegassa Spinola and Lophius piscatorius Linnaeus) from the Atlantic Iberian coast. Fish Res. 2001;51:349–361. doi: 10.1016/S0165-7836(01)00259-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esteves E, Aníbal J. Sensory evaluation of seafood freshness using the quality index method: a meta-analysis. Int J Food Microbiol. 2021;337:108934. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2020.108934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giarratana F, Nalbone L, Ziino G, Giuffrida A, Panebianco F. Characterization of the temperature fluctuation effect on shelf life of an octopus semi-preserved product. Ital J Food Saf. 2020;9:8590. doi: 10.4081/ijfs.2020.8590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffrida A, Valenti D, Giarratana F, Ziino G, Panebianco A. A new approach to modelling the shelf life of Gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) Int J Food Sci Technol. 2013;48:1235–1242. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.12082. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gram L, Trolle G, Huss HH. Detection of specific spoilage bacteria from fish stored at low (0 °C) and high (20 °C) temperatures. Int J Food Microbiol. 1987;4:65–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(87)90060-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huidobro A, Pastor A, Lopez-Caballero ME, Tejada M. Washing effect on the quality index method (QIM) developed for raw gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) Eur Food Res Technol. 2001;212:408–412. doi: 10.1007/s002170000243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hyldig G, Bremner A, Martinsdottir E, Schelvis R. Quality index methods. In: Nollet LML, editor. Handbook of meat, poultry and seafood quality. New Jersey: Blackwell Publishing; 2007. p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 11035:1994 (1994) Sensory analysis-identification and selection of descriptors for establishing a sensory profile by a multidimensional approach. International Organization for Standardization

- ISO 4833-1:2013 (1994) Microbiology of the food chain—horizontal method for the enumeration of microorganisms—part 1: colony count at 30 °C by the pour plate technique. International Organization for Standardization

- ISO 5492:2008 (2008) International Standard 5492. Sensory analysis—sensory vocabulary. International Organization for Standardization

- ISO 8586-1:1993 (1993) Sensory analysis—general guidance for the selection, training and monitoring of assessors—part 1: selected assessors. International Organization for Standardization

- Llorente I, Fernández-Polanco J, Baraibar-Diez E, Odriozola MD, Bjørndal T, Asche F, Guillen J, Avdelas L, Nielsen R, Cozzolino M, Luna M, Fernández-Sánchez JL, Luna L, Aguilera C, Basurco B (2020) Assessment of the economic performance of the seabream and seabass aquaculture industry in the European Union. 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103876

- Martinsdóttir E, Sveinsdottir K, Luten J, Schelvis-Smit R, Hyldig G (2001) Sensory evaluation of fish freshness. IJmuiden, The Netherlands: QIM eurofish. https://www.esn-network.com/fileadmin/inhalte/documents/Conference-ESN-Martinsdottir.pdf. Accessed 23 Apr 2020

- Pennisi L, Olivieri V, D’Aurelio R, Piscione I. Application of quality index method (QIM) scheme in shelflife study of anglerfish (Lophius piscatorius) Ital J Food Saf. 2011;1:237–241. doi: 10.4081/ijfs.2011.871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhakar PK, Vatsa S, Srivastav PP, Pathak SS. A comprehensive review on freshness of fish and assessment: analytical methods and recent innovations. Food Res Int. 2020;133:109157. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quéméner L, Suquet M, Mero D, Gaignon JL. Selection method of new candidates for finfish aquaculture: the case of the French Atlantic, the Channel and the North Sea coasts. Aquat Living Resour. 2002;15:293–302. doi: 10.1016/S0990-7440(02)01187-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EC) No. 2406/96 (1996) of 26 November 1996 laying down common marketing standards for certain fishery products. OJEU L 334/1. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:31996R2406. Accessed 03 October 2020

- Regulation (EC) No. 853/04 (2004) Of the European parliament and of the council of 29April 2004 laying down specific hygiene rules for on the hygiene of foodstuffs. OJEU L 139/55. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32004R0853. Accessed 03 October 2020

- Tretola M, Ottoboni M, Di Rosa AR, Giromini C, Fusi E, Rebucci R, Leone F, Dell’Orto V, Chiofalo V, Pinotti L. Former food products safety evaluation: computer vision as an innovative approach for the packaging remnants detection. J Food Qual. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/1064580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trabelsi N, Nalbone L, Di Rosa AR, Ed-Dra A, Nait-Mohamed S, Mhamdi R, Giuffrida A, Giarratana F. Marinated Anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus) prepared with flavored olive oils (Chétoui cv.): anisakicidal effect, microbiological, and sensory evaluation. Sustainability. 2021;13:5310. doi: 10.3390/su13095310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez-Sánchez D, García EES, Galvão JA, Oetterer M. Quality index method (QIM) scheme developed for whole Nile tilapias (Oreochromis niloticus) ice stored under refrigeration and correlation with physicochemical and microbiological quality parameters. J Aquat Food Prod Technol. 2020;29:1–13. doi: 10.1080/10498850.2020.1724222. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward DR, Hackney CA. Microbiology of marine food products. Berlin: Springer; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang S, Hong H, Zhang L, Luo Y. Spoilage-related microbiota in fish and crustaceans during storage: research progress and future trends. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2021;20:252–288. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Not applicable.