Abstract

The purpose of this study was to identify the cell populations involved in recovery from oral infections with Candida albicans. Monoclonal antibodies specific for CD4+ cells, CD8+ cells, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes were used to deplete BALB/c and CBA/CaH mice of the relevant cell populations in systemic circulation. Monocytes were inactivated with the cytotoxic chemical carrageenan. Mice were infected with 108 C. albicans yeast cells and monitored for 21 days. Systemic depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes alone did not increase the severity of oral infection compared to that of controls. Oral colonization persisted in animals treated with head and neck irradiation and depleted of CD4+ T cells, whereas infections in animals that received head and neck irradiation alone or irradiation and anti-CD8 antibody cleared the infection in a comparable fashion. The depletion of polymorphonuclear cells and the cytotoxic inactivation of mononuclear phagocytes significantly increased the severity of oral infection in both BALB/c and CBA/CaH mice. High levels of interleukin 12 (IL-12) and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) were produced by lymphocytes from the draining lymph nodes of recovering animals, whereas IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IFN-γ were detected in the oral mucosae of both naïve and infected mice. The results indicate that recovery from oropharyngeal candidiasis in this model is dependent on CD4+-T-cell augmentation of monocyte and neutrophil functions exerted by Th1-type cytokines such as IL-12 and IFN-γ.

Clinical and laboratory studies have shown that neutrophils (polymorphonuclear leukocytes [PMNLs]) play a major role in host defense against systemic candidiasis (2, 3, 27, 31), although recent work suggests that there is also a role for T cells and their cytokines in recovery from this disease (45). Oral candidiasis, however, has been consistently associated with defects in the cell-mediated arm of the immune response (30, 33, 38). For example, children with thymic aplasia (DiGeorge syndrome) (11), patients suffering from human immunodeficiency virus and AIDS (34, 49), and those undergoing therapeutic chemotherapy and radiotherapy (42) are all more susceptible to oral candidiasis.

The essential role for CD4+ T cells in oral infection has been demonstrated in an immunodeficient nu/nu mouse model (C. S. Farah et al., submitted for publication). However, since T cells do not kill Candida spp. directly, phagocytic cells clearly play an important role in mediating clearance of the yeast from the oral cavity. Both neutrophils and macrophages have been shown to exert candidacidal activity and probably represent the first line of defense against this yeast (16, 24). Indeed, neutrophil infiltration is the hallmark of oral candidal lesions (44, 51), often forming microabscesses in the epithelium of infected tissue.

Many patients with defects in neutrophil and macrophage function are susceptible to oral candidiasis. Patients suffering from primary immunodeficiencies such as hereditary myeloperoxidase deficiency have defects in neutrophil and macrophage activity due to an absence of myeloperoxidase from their granules, while patients with Chediak-Higashi syndrome have abnormal PMNLs with neutropenia and impaired chemotaxis (55). These defects are thought to account for the impaired killing of Candida albicans in these patients, making them more susceptible to oral candidiasis.

Although the number and function of neutrophils and monocytes in T-cell-deficient nu/nu mice are normal (22), these mice could not clear an oral infection unless they were reconstituted with T lymphocytes (Farah et al., submitted). This finding suggests that, although phagocytic cells are present in these mice, their anticandidal activity is dependent on T-cell factors, most likely cytokines.

Therefore, the purposes of this study were to evaluate the relative contributions of CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in an inbred mouse model by monoclonal depletion and radiation treatment and to explore the contribution of neutrophils and macrophages to local defense against C. albicans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Specific-pathogen-free BALB/c and CBA/CaH female mice, 6 to 8 weeks of age, were purchased from the Animal Resources Centre, Perth, Australia. These mice undergo routine microbiological screening and do not harbor C. albicans in the gut. Animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee of the University of Queensland and carried out in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council's Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes, 1997. Mice were housed in standard cages and provided with food and water ad libitum.

Yeast.

C. albicans isolate 3630 was obtained from a patient with cutaneous candidiasis, submitted to the Mycology Reference Laboratory at the Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney, Australia, and stored at −70°C in Sabouraud's broth–15% (vol/vol) glycerol. For use, yeast cells were grown in Sabouraud's broth for 48 h at room temperature with continuous agitation on a magnetic stirrer. Blastospores were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and adjusted to the appropriate concentration for inoculation.

Oral infection.

Mice were inoculated orally with 108 live C. albicans yeast cells in 20 μl of PBS. The infection was monitored by swabbing the oral cavity with sterile cotton swabs moistened with sterile PBS and plating the yeast on Sabouraud's agar plates. Agar plates were incubated for 48 h at 37°C. All inoculation and sampling procedures were carried out with the mice being under halothane anaesthesia. CFU were counted on Sabouraud's agar plates. The counts were assigned into five groups correlating with the level of recoverable yeast from the oral cavity. This process provided a semiquantitative measure of the level of floridity of the infection. The scoring system used was as follows: 0, no detectable yeast; 1, 1 to 10 CFU/plate; 2, 11 to 100 CFU/plate; 3, 101 to 1,000 CFU/plate; and 4, 1,000 or more CFU/plate.

Histopathology.

Mice were sacrificed at various time points throughout the course of the experiment for histopathological examination of tissues. Skulls were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (pH 7.0) and decalcified in a 5% formic acid and sodium formate mixture. Frontal sections of the skulls were taken at approximately 3-mm intervals, with consecutive sections being stained with hematoxylin and eosin and according to the periodic acid-Schiff technique. Sections were examined by light microscopy.

CD4+- and CD8+-T-cell depletion.

The hybridoma cell lines YTS191.1.2 and YTS169.4.2.1 that produce monoclonal antibodies specific for mouse CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes, respectively (12, 41), were obtained courtesy of S. Cobbold, Sir William Dunn School of Pathology, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom. Cell lines were seeded into a miniPERM Bioreactor (Heraeus, Osterode/Harz, Germany) at 6 × 104 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 tissue culture medium (Trace Biosciences, Castle Hill, New South Wales, Australia). Antibodies were produced by the Antibody Facility at the Centre for Molecular and Cellular Biology, University of Queensland. The concentration of protein was calculated, and the supernatant was pretested in mice to determine the optimal dose for depletion. Mice were depleted of lymphocytes by intraperitoneal injection of 300 μg of antibody on day −2 and then every second day throughout the course of the experiment. Control mice were injected with PBS. Depletion was confirmed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of spleen and lymph node cells on days 1 and 4 following antibody injection and at the termination of the experiment using fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) conjugated and R-phycoerythrin (R-PE)-conjugated commercial antibodies specific for mouse CD4 and CD8, respectively.

Neutrophil depletion.

A cell line (RB6-8C5) that secretes a monoclonal antibody specific for mouse neutrophils was obtained courtesy of R. Coffman, DNAX Institute, Palo Alto, Calif. This rat immunoglobulin G2b (IgG2b) monoclonal antibody reacts with the Gr-1 surface antigen expressed on murine granulocytes but not with monocytes or lymphocytes (22, 43). The cell line was grown as described above. The supernatant was used without further purification and pretested to determine the optimal dose for depletion. Mice were depleted of neutrophils by intraperitoneal administration of 300 μg of the antibody preparation on day −2 and then at 48-h intervals until day 8. Control mice received a similar course of PBS injections. Complete depletion of PMNLs was confirmed by blood smears taken 1 and 4 days after treatment with the monoclonal antibody and stained with May-Grunwald–Giemsa stain. Granulocyte and monocyte numbers were monitored throughout the course of the experiment with the use of stained blood smears.

Macrophage inactivation.

Carrageenan (type IV λ; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Mo.) was dissolved in sterile PBS at 5 mg/ml. The solution was heated to 56°C to ensure complete solubilization. Mice were treated by intraperitoneal injection of 200 μl (1 mg) of carrageenan 2 days prior to oral inoculation. Control mice received 200 μl of sterile PBS.

Intramucosal injection of depleting antibodies.

Mice were injected with depleting antibody for CD4 or CD8 directly into the oral tissues. A dose of 50 μl was injected intramucosally into the left and right buccal mucosae according to the time scale noted above. The mice were infected with Candida yeast and monitored for 21 days. Control animals received an injection of an equal volume of PBS.

Radiation.

Mice received head and neck irradiation equivalent to 800 rads using a Cobalt-60 γ-radiation source. The mice were anesthetized and placed one at a time in a protective lead chamber, with only the head in the direct path of radiation. Mice were inoculated with the yeast immediately after irradiation as described above.

Cell surface antigen staining.

Lymphocytes were obtained by pressing either spleens or lymph nodes through a sterile metal sieve, followed by filtration through an 80-μm- pore-size nylon mesh. The cells were resuspended in 6 ml of PBS and separated on a Ficoll gradient by placing the cell suspension over 4 ml of Ficoll-Hypaque (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden). The gradient was centrifuged at 700 × g for 25 to 30 min at room temperature. The buffy coat interface was carefully removed, washed twice in PBS, and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS. Viable lymphocytes were counted in a hemocytometer after being stained with trypan blue and adjusted to the appropriate concentration for injection into recipient mice. Cells (106) were stained in 50 μl of 0.1% PBS-NaN3 for 30 min at 4°C in the dark, using an appropriate concentration of a fluorochrome-conjugated monoclonal antibody specific for a cell surface antigen or isotype control (1 μl of FITC-rat anti-mouse CD4 [IgG2a], 1.5 μl of R-PE-rat anti-mouse CD8 [IgG2a], 1 μl of FITC-rat IgG2a isotype control Ig, and 1.5 μl of R-PE-rat IgG2a isotype control Ig; PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.). The cells were washed twice in 0.1% PBS–NaN3, spun at 1,500 rpm for 5 min, and resuspended in 500 μl of 1% Formalin. Cells were analysed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting.

Cytokine ELISA.

Lymphocytes isolated from the submandibular and superficial cervical (SMSC) lymph nodes were cultured ex vivo for 3 days at 4 × 106 cells/ml in RPMI 1640 tissue culture medium, without antigen stimulation. The supernatant was collected, filtered through a 0.8-μm-pore-size filter, and stored at −20°C until analyzed. The culture supernatant was assayed for interleukin 4 (IL-4), IL-10, IL-12, and gamma interferon (IFN-γ) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using matched-antibody pairs and recombinant cytokines as standards. Briefly, immuno-polysorb microtiter plates (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with capture rat monoclonal anti-IL-4 (IgG1), IL-10 (IgG1), IL-12 (IgG2a), or IFN-γ (IgG1) antibody (PharMingen) at 1 μg/ml in sodium bicarbonate buffer overnight at 4°C. The wells were washed and then blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin–PBS before the culture supernatants and the appropriate standard were added to each well. Biotinylated rat monoclonal anti-IL-4, IL-10, IL-12, or IFN-γ antibody (PharMingen) at 2 μg/ml was added as the second antibody. Detection was carried out with streptavidin peroxidase and tetramethylbenzidine. The results were expressed as net Candida-induced counts from which the background was subtracted (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Cytokine production by BALB/c mouse SMSC lymph node cells after oral infection with 108 C. albicans yeast cellsa

| Day postinfection | Mean (±SEM) titer (pg/ml) of:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-4 | IL-10 | IL-12 | IFN-γ | |

| 4 | 0 (0) | 44.0 (5.1) | 95.7 (4.2) | 35.7 (10.3) |

| 8 | 0 (0) | 66.5 (5.9) | 293.6 (35.9) | 206.0 (16.6) |

| 14 | 39.6 (1.2) | 51.5 (18.2) | 46.1 (5.2) | 62.9 (29.2) |

| 21 | 0 (0) | 53.6 (6.8) | 451.2 (20.6) | 156.2 (7.7) |

Results are mean (±SEM) cytokine titers in supernatants from lymphocytes pooled from a minimum of three mice/group/time point. Lymph node cells were cultured for 3 days ex vivo, and supernatants were analyzed by ELISA.

RNA isolation.

Tissues were homogenized in 1 ml of Ultraspec RNA reagent (Biotecx Laboratories, Houston, Tex.) per 10 to 100 mg of tissue using an Ultra-Turrax T25 homogenizer. The homogenate was held for 5 min at 4°C to permit the complete dissociation of nucleoprotein complexes, at which time 200 μl of chloroform was added and the tubes were vigorously shaken for 15 and then stored on ice for another 5 min. The homogenate was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C, and the upper phase was transferred to a new Eppendorf tube without the interphase being disturbed. An equal volume of isopropanol was added, and samples were stored on ice for 10 min and then centrifuged at 10,000 × g for another 10 min at 4°C. The RNA pellet was washed twice in 1 ml of 75% ethanol by vortexing and subsequent centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The pellet was briefly dried for 5 to 10 min and dissolved in 25 μl of diethyl pyrocarbonate-water by vortexing for 1 min. The concentration and purity of the RNA samples were determined by spectrophotometry at 260 and 280 nm and then the samples were stored at −70°C until required.

RT-PCR.

cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription (RT) of 1 μg of each RNA, using an oligo(dT)15 primer and avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Briefly, 4 μl of 25 mM MgCl2 solution, 2 μl of 10× PCR amplification buffer (670 mM Tris-HCl, 166 mM [NH4]2SO4, 4.5% Triton X-100, 2 mg of gelatin/ml [BioTech International, Western Australia, Australia]), 2 μl of a 10 mM concentration of a deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix, 0.5 μl of RNasin, 0.75 μl (15 U) of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase, 0.5 μg of oligo(dT)15 primer, and 1 μg of an mRNA sample were incubated in a 20-μl reaction mix at 42°C for 1 h, heated to 99°C for 5 min, and then cooled on ice. cDNA was amplified by PCR in an amplification mix consisting of 2 μl of 25 mM MgCl2, 2.5 μl of 10× reaction buffer, 2 μl of 25 a mM concentration of the deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix, 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase, the appropriate primer, and 1 μl of cDNA in a total volume of 25 μl. Negative controls (without cDNA) were included for all primers used in each run. The mixture was amplified using a PTC-100 programmable thermal cycler (MJ Research, Inc., Watertown, Mass.). The amplification protocol was 35 to 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. Following amplification, 10 μl of product was analyzed by electrophoresis through 2.5% (wt/vol) agarose gels. The gels were stained with ethidium bromide, and the bands were visualized using a UV transilluminator (GelDoc 2000; Bio-Rad, Regents Park, New South Wales, Australia) with appropriate software (MultiAnalyst version 1.1; Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Primer sequences for IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) were obtained from published data (36) and synthesized at the Australian Neuromuscular Research Institute, Perth, Western Australia, Australia. The sequence for IL-10 was taken from published data (47) and synthesized by Bresatec, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia.

Statistics.

Quantitative data were analyzed using the statistical features of GraphPad Prism version 2.01 (GraphPad, Inc., San Diego, Calif.). Student's t test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used with a P of <0.05 unless otherwise specified.

RESULTS

CD4+- and CD8+-T-cell depletion.

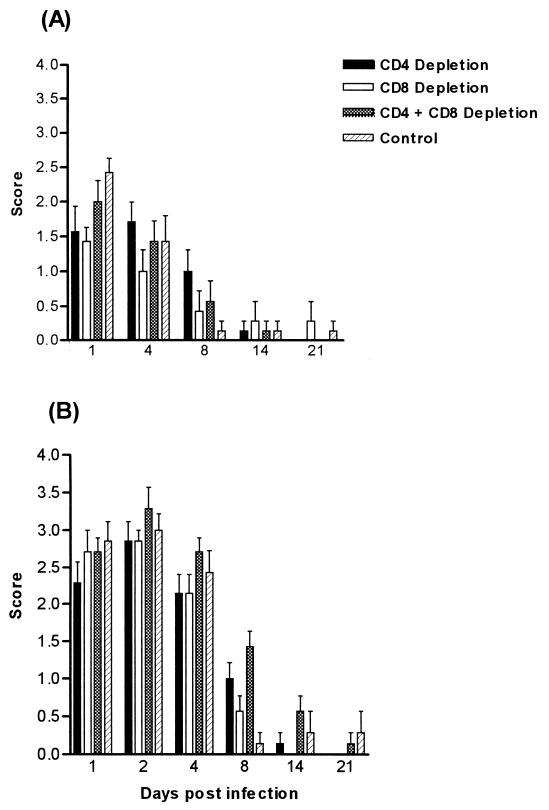

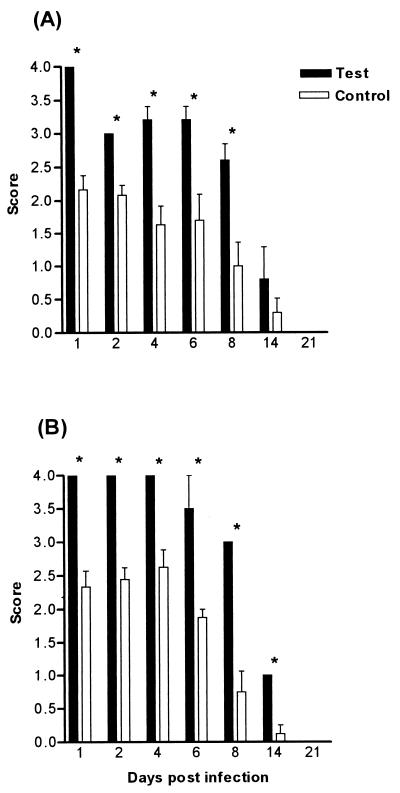

BALB/c and CBA/CaH mice were depleted of either CD4+ or CD8+ or both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by systemic administration of specific depleting monoclonal antibodies. Initially, the antibodies achieved approximately 90% depletion, which dropped to 50 to 60% by day 8. Animals were infected with 108 C. albicans yeast cells 2 days following the first antibody injection. Oral colonization in mice treated with depleting antibody was not significantly different from that of control animals, for both BALB/c and CBA/CaH mice (Fig. 1). Although spleen and lymph node T-cell populations were depleted, no effect was seen at the mucosal surface with regard to the clearance or colonization of the yeast in the oral cavity.

FIG. 1.

Oral infection after CD4+- and CD8+-T-cell depletion by monoclonal antibodies in BALB/c (A) and CBA/CaH (B) inbred mice. Bars represent scores (means ± standard errors of the means [SEM]) for a minimum of 10 mice/group. Control mice received no antibody. Systemic T-cell depletion did not significantly affect the severity of oral infection.

Intramucosal injection of CD4- and CD8-depleting antibodies.

Depleting antibodies were injected intramucosally into BALB/c and CBA/CaH mice. Control animals were injected with PBS to control for the effect of trauma. Both test and control groups were subsequently inoculated 2 days later with C. albicans. Treatment with CD4- and CD8-specific antibodies had no effect on the severity of oral colonization; however, the anti-CD4 antibody did prolong the infection compared to that of control mice (data not shown).

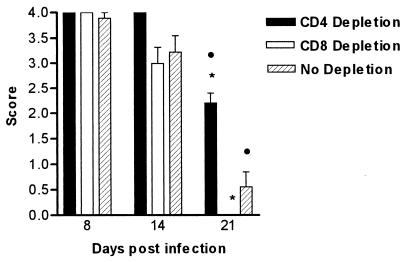

Radiation and depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

Failure to achieve an effect at the mucosal surface by systemic and intramucosal injections of anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies suggested that T cells resident in the oral mucosa were contributing to host defense in these animals. In order to eliminate the contribution of these resident T cells to responses in the oral mucosa, BALB/c mice were treated with irradiation to the head and neck and depleted systemically of either CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Control mice received an equivalent dose of irradiation with no antibody treatment. All animals were infected with 108 C. albicans yeast cells and monitored. Radiation treatment significantly exacerbated the severity of the oral infection with the yeast, as demonstrated by the high scores seen on days 8 and 14 following infection. Mice that were treated with irradiation alone were able to significantly eliminate the yeast by day 21, as were those that were irradiated and depleted of CD8+ T cells (Fig. 2). Mice that received antibody specific for CD4+ T cells did not clear the infection on day 21. This was significant (P < 0.01) compared to the responses of control mice that received irradiation alone and those that received head and neck irradiation in conjunction with anti-CD8 antibody (P < 0.001). There was no difference in the severity of the disease between control mice and nonirradiated animals that were only systemically depleted at any time point following infection (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Oral infection after CD4+- and CD8+-T-cell depletion in irradiated BALB/c mice. Irradiated mice were treated with 800 rads of γ-irradiation to the head and neck. Mice were depleted of either CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. Control mice received no antibody. Bars represent scores (means ± SEM) for a minimum of 10 mice/group. CD4+-T-cell depletion significantly prolonged the infection in irradiated mice compared to that in control mice (•, P < 0.01) and that in mice treated with anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody and irradiation ( , P < 0.001). SEM were 0 if error bars are not shown.

, P < 0.001). SEM were 0 if error bars are not shown.

Cytokine production by lymph node cells using ELISA.

ELISA performed on culture supernatants of SMSC lymphocytes isolated from BALB/c mice following oral infection demonstrated high levels of IL-12 on days 8 (293 pg/ml) and 21 (451 pg/ml), with moderate titers on day 4 (95 pg/ml) and low levels on day 14 (46 pg/ml). Concentrations of IFN-γ were moderate (35 to 206 pg/ml) and appeared to follow the pattern of production of IL-12. Low levels of IL-10 (44 to 66 pg/ml) were detected during the course of the infection, whereas IL-4 was detected only on day 14 (39 pg/ml). The concentrations of IL-12 and IFN-γ were significantly higher than those of IL-4 and IL-10 on days 8 and 21 but not so on days 4 and 14 (Table 1).

Cytokine gene expression in oral tissues using RT-PCR.

Oral mucosae and tongues from BALB/c and CBA/CaH mice were examined for the presence of RNA for IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α, and IFN-γ. Message for IL-2, IL-4, and IL-10 was undetectable in both naïve and infected BALB/c mice. IL-6, TNF-α, and IFN-γ were detected in both naïve and infected oral tissue. The cytokine profile for CBA/CaH mice was identical to that seen in BALB/c oral tissues.

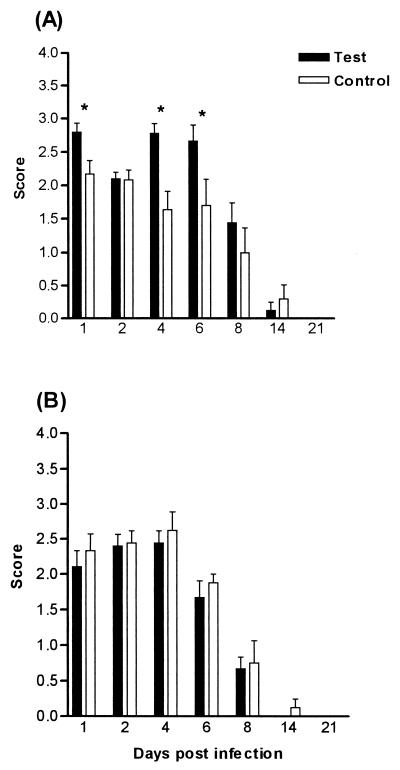

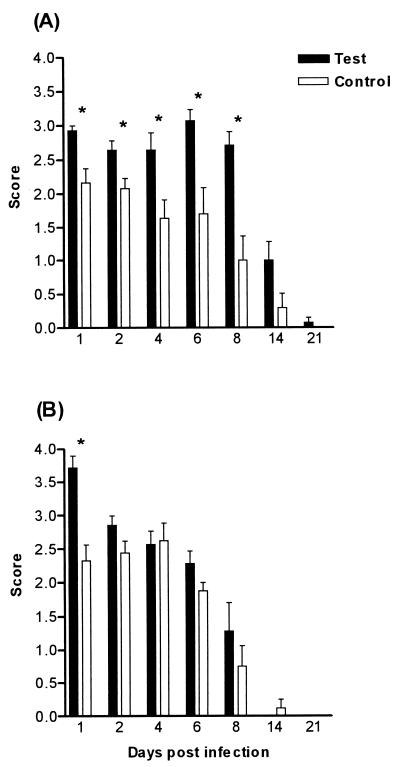

Neutrophil depletion and macrophage inactivation.

The effects of depletion of polymorphonuclear phagocytes and the inactivation of monocytes/macrophages on the severity and duration of oral colonization were determined in BALB/c and CBA/CaH mice. In BALB/c mice, PMNL depletion alone increased the severity of the infection compared to that of control mice (Fig. 3A). Results were significant (P < 0.05) only on days 1, 4, and 6. Macrophage inactivation alone significantly increased the severity of the infection (P < 0.01) compared to that of controls on days 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8 (Fig. 4A). Eliminating both phagocytic cell types significantly increased the severity of the infection (P < 0.01), but this increase was only slightly greater than that seen after macrophage elimination alone (Fig. 5A). PMNL depletion alone did not affect the severity of the infection in CBA/CaH mice, nor did macrophage inactivation, except on day 1 (Fig. 3B and 4B). Ablation of both neutrophils and macrophages was required to significantly increase the severity of the infection in CBA/CaH mice (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5B). The increase in severity of the oral infection when both phagocytic cell types were inactivated was more dramatic in CBA/CaH than in BALB/c mice (Fig. 5).

FIG. 3.

Oral infection after PMNL depletion in BALB/c (A) and CBA/CaH (B) mice. Test animals received monoclonal antibody injections prior to C. albicans infection and then at 48-h intervals until day 8. Control mice received no antibody. Bars represent scores (means ± SEM) for a minimum of 10 mice/group. Test mice were significantly different from control mice ( , P < 0.05) using Dunnett's test of the ANOVA.

, P < 0.05) using Dunnett's test of the ANOVA.

FIG. 4.

Oral infection after macrophage inactivation in BALB/c (A) and CBA/CaH (B) mice. Test animals received carrageenan prior to C. albicans infection. Control mice received no treatment. Bars represent scores (means ± SEM) for a minimum of 10 mice/group. Test mice were significantly different from control mice ( , P < 0.01) using Dunnett's test of the ANOVA.

, P < 0.01) using Dunnett's test of the ANOVA.

FIG. 5.

Oral infection after PMNL depletion and macrophage inactivation in BALB/c (A) and CBA/CaH (B) mice. Test animals received monoclonal antibody and carrageenan prior to C. albicans infection. Control mice received no treatment. Bars represent scores (means ± SEM) for a minimum of 10 mice/group. Test mice were significantly different from control mice ( , P < 0.01) using Dunnett's test of the ANOVA.

, P < 0.01) using Dunnett's test of the ANOVA.

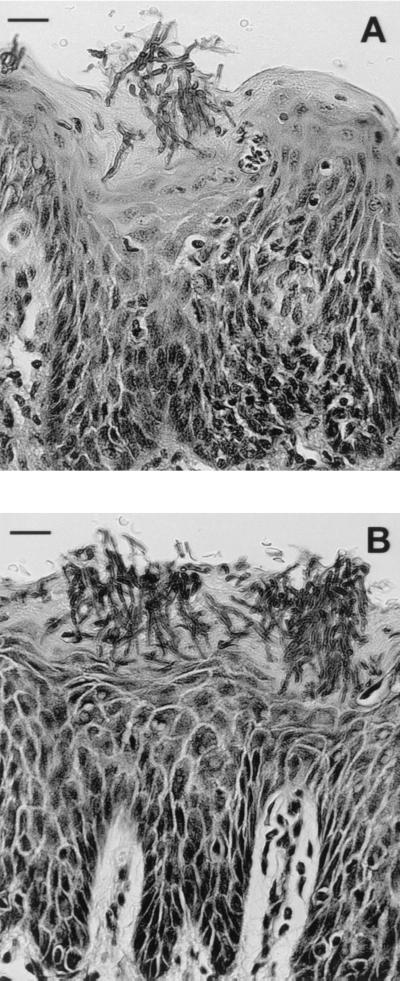

Histopathology of oral tissues following PMNL depletion and macrophage inactivation.

Histopathological examination of oral tissues following neutrophil depletion and macrophage inactivation revealed more abundant Candida hyphae penetrating the keratinized surface epithelium (Fig. 6). CBA/CaH mice (Fig. 6B) were more heavily colonized than BALB/c mice (Fig. 6A). There was evidence of high connective tissue papillae and thickening and blunting of rete ridges. Polymorphonuclear microabscesses were not present, but transmigrating intraepithelial PMNLs were still observed.

FIG. 6.

Histopathological sections of BALB/c (A) and CBA/CaH (B) oral tissue infected with 108 C. albicans yeast cells following PMNL depletion and macrophage inactivation (day 4). Sections show abundant Candida hyphae penetrating the surface epithelium, with the absence of PMNL microabscesses. Sections were stained with periodic acid-Schiff stain. Scale bars, 45 μm.

DISCUSSION

T lymphocytes have been implicated in recovery from systemic (45), gastrointestinal (4, 5, 8, 9), and oral (10, 17) infections with C. albicans. In systemic infection, Th1 cytokines correlate with resistance and Th2 cytokines correlate with chronic disease (45), but less is known about the relative importance and function of the T-cell subsets in oral infection.

In this study, depletion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells significantly decreased the numbers of these cells in the systemic circulation but failed to demonstrate any role for these cell populations in clearance of the yeast from the mucosal surface. Animals treated with the depleting antibodies were no more susceptible to oral challenge than control mice and cleared the infection in a similar fashion. Comparable results have been observed in experimental vaginal candidiasis (18, 19). Systemic administration of anti-CD4 and anti-CD8 antibodies in these studies effectively depleted the cells in systemic circulation but had no effect on the vaginal C. albicans burden in mice after a primary or secondary vaginal inoculation (19). It was suggested that antibodies administered systemically were either unable to reach the mucosa or did not reach the mucosa at high-enough concentrations to achieve a detectable effect (18). However, Fidel et al. were able to demonstrate that intravaginal injection of depleting antibodies resulted in T-cell depletion in both the vagina and the systemic circulation (18). In the present study, subset-specific monoclonal antibodies were injected into the oral mucosae of BALB/c mice prior to C. albicans inoculation. No significant effect on oral colonization was observed in animals depleted of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells, although the duration of infection was slightly prolonged in mice depleted of CD4+ cells.

It is possible that the antibodies used in our experiments were not effective against all T cells present in the oral mucosa, since mucosal T cells are phenotypically and functionally different than those in the periphery (50). Flow cytometric analysis of T cells in oral mucosal epithelium shows that while α/β T cells often predominate, the percentages of γ/δ T cells are always considerably higher than in the periphery (25, 32, 39). Moreover, mucosal α/β T cells are not identical to their systemic counterparts (50). Both γ/δ and α/β T cells may be resident in the oral mucosa, and both may have a role in the clearance of the yeast from the mucosal surfaces (10, 17). In a recent study, mice made deficient for α/β or γ/δ T cells (α-or δ-chain T-cell receptor knockout mice, respectively) were more susceptible to orogastric candidiasis than immunocompetent controls (29). Nevertheless, irradiated mice depleted of CD4+ cells showed an impaired ability to clear the infection compared to that of mice that were irradiated and depleted of CD8+ cells or irradiated controls. This result demonstrated that the circulating CD4+ T cells in mice were able to repopulate the oral mucosa or draining lymph nodes and exert a protective effect against the yeast.

In the present experiments, depletion of CD8+ cells resulted in a slightly accelerated clearance of yeast from the oral cavity, but it remains to be established whether this was due to deleterious activity of the CD8+ cells themselves or to some regulatory interaction with the CD4+ cells. The precise role of CD8+ lymphocytes in host defense against candidiasis has not yet been defined. Activated CD8+ cells have been shown to have the potential to lyse Candida-infected macrophages (48), to reduce tissue damage associated with systemic infection (1), and to have some protective effect against systemic infection, although this potential was masked by the immunopathological activities of CD4+ T cells (13).

In an investigation of the role for IL-2 and IFN-γ in mucosal candidiasis, Cantorna and Balish (5) failed to demonstrate a substantial role for these cytokines in protecting the oral mucosa from candidal infection, although CD4+ T lymphocytes were crucial in preventing candidiasis in this model. Cenci et al. (9) have previously concluded that activation of Th1- but not Th2-like responses may be responsible locally for controlling gastrointestinal candidiasis and generating protective immunity (9). They have also shown that mice deficient for the IFN-γ receptor fail to mount protective Th1-mediated acquired immunity upon mucosal challenge (8). The impaired Th1-mediated resistance correlated with defective IL-12 responsiveness but not IL-12 production. Cenci et al. concluded that IFN-γ was required for development of IL-12-dependent protective Th1-dependent immunity.

IL-12 is produced by phagocytic cells and is known to act on T lymphocytes by inducing proliferation and production of cytokines such as IFN-γ (52–54). In turn, IFN-γ activates macrophages and enhances their phagocytic abilities (35, 37). IL-12 has been demonstrated to play a role in, and is an obligatory factor for, Th1 induction. It acts directly on Th1 lymphocytes, and part of this activity is due to the induction of IFN-γ production by T and NK cells. IL-12 and IFN-γ are known to be involved in natural and acquired aspects of the immune response (52), and it is perhaps some aspect of this interaction that underlies the effector function of CD4+ T cells in the host response to oral candidiasis.

From the data presented in this study and those of others (5, 8, 9), there is little evidence that IL-2, IL-4, or IL-10 plays a significant role in mucosal candidiasis. The production of Th1-type cytokines such as IL-12, IFN-γ, and TNF-α appears to be relevant to the clearance of this yeast from the oral mucosal tissues of infected mice.

The role of innate defense mechanisms against oral candidiasis were examined in BALB/c and CBA/CaH mice by monoclonal antibody depletion of neutrophils and cytotoxic inactivation of macrophages.

It is well established, by both clinical and experimental studies, that either quantitative (3, 27) or qualitative (2, 31) neutrophil defects are a predisposing factor to disseminated candidiasis and that depletion of neutrophils significantly increases the susceptibility to systemic candidiasis (20, 46). Neutrophils provide the first line of defense against systemic candidiasis, but their role in oral candidiasis has not been fully explored. The RB6-8C5 monoclonal antibody is a rat IgG2b reagent that selectively binds to and depletes mature mouse neutrophils and eosinophils but not lymphocytes and macrophages (14, 43). In the present study, depletion of neutrophils in BALB/c, but not in CBA/CaH, mice significantly increased the severity of oral infection.

The other cell type with major anticandidal activity is the macrophage. Macrophages are able to kill C. albicans through several effector pathways, and their candidacidal state can be enhanced by activation with a number of different cytokines. Several techniques have been used to eliminate macrophages, including liposomes containing dichloromethylene diphosphonate, silica, and carrageenan. In our experiments the use of carrageenan was a simple and effective method to eliminate macrophages in order to study their contribution to host resistance against oral candidiasis.

Elimination of macrophages increases susceptibility to systemic candidiasis (23, 27, 40), but few studies have assessed the role of monocytic phagocytes in resistance to mucosal candidiasis. Impairment of macrophage function with poly(I-C) increased the susceptibility of scid mice to disseminated candidiasis of endogenous origin (gastrointestinal tract) (26, 28), but immunocompetent controls were resistant to mucosal candidiasis after poly(I-C) treatment. In fact, interference with both macrophage and neutrophil function was necessary to render these mice susceptible to mucosal infection (28). In the present experiment, concurrent depletion of neutrophils and elimination of macrophages also induced a substantial increase in susceptibility in BALB/c and CBA/CaH mice. Although each treatment alone significantly increased the susceptibility of BALB/c mice, both were required to demonstrate an effect in the CBA/CaH strain. This finding suggests that in CBA/CaH mice either neutrophils or macrophages are capable of maintaining an effective host response but that in BALB/c mice there may be limitations in the production or function of these cells that render them more susceptible to the effects of depletion.

Neutrophils in infected oral tissue are the hallmark of C. albicans infection, and activation of macrophages appears to be necessary for the full expression of resistance to disease. It was expected that depletion of either of these cells would lead to a more pronounced exacerbation of the infection at the mucosal surface. It is possible that each of these phagocytic subsets can compensate for the absence of the other, thereby containing the initial spread and allowing the T cells to exert their functions. Additionally, it must be noted that a significant effect of carrageenan administration is granulocytosis (23). It has been reported that the number of PMNLs in peripheral blood increased after carrageenan administration, possibly explaining the increased resistance of treated mice to systemic candidiasis (23).

It is evident that neutrophils are important effector cells against C. albicans (15) and that, together with macrophages, they are probably responsible for the ultimate elimination of the fungus. However, recent studies of humans (6, 7) and mice (46) suggest that neutrophils are also capable of synthesizing immunomodulatory cytokines such as IL-10 and IL-12. These cytokines are secreted by neutrophils early in infection and are therefore important in the generation of the anticandidal Th-cell response, which in turn modulates the functions of neutrophils. In our work, it is possible that IL-12 production by neutrophils selected a Th1-type response by T cells.

In conclusion, this article emphasizes the importance of CD4+ T lymphocytes in oral candidiasis and supports clinical observations that link oral C. albicans infections to defects in cell-mediated immunity. The data also support the role for Th1-type cytokines and protective immunity in the resolution of oral candidiasis in infected mice. It appears that the clearance of an oral C. albicans infection is dependent on CD4+-T-cell augmentation of monocyte and neutrophil functions exerted by Th1-type cytokines such as IL-12 and IFN-γ.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. C.S.F. was supported by an NH and MRC dental postgraduate research scholarship.

We thank Slavica Pervan for the preparation of the histological samples and Karen Drysdale for the RT-PCR assays.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ashman R B, Fulurija A, Papadimitriou J M. Both CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes reduce the severity of tissue lesions in murine systemic candidiasis, and CD4+ cells also demonstrate strain-specific immunopathological effects. Microbiology. 1999;145:1631–1640. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-7-1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ashman R B, Papadimitriou J M. Susceptibility of beige mutant mice to candidiasis may be linked to a defect in granulocyte production by bone marrow stem cells. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2140–2146. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.2140-2146.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodey G P, Buckley M, Sathe Y S, Freireich E J. Quantitative relationships between circulating leukocytes and infection in patients with acute leukemia. Ann Intern Med. 1966;64:328–340. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-64-2-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cantorna M T, Balish E. Mucosal and systemic candidiasis in congenitally immunodeficient mice. Infect Immun. 1990;58:1093–1100. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.1093-1100.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantorna M T, Balish E. Role of CD4+ lymphocytes in resistance to mucosal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1991;59:2447–2455. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.7.2447-2455.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassatella M A. The production of cytokines by polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Immunol Today. 1995;16:21–26. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassatella M A, Meda L, Gasperini S, D'Andrea A, Ma X, Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12 production by human polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1995;25:1–5. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cenci E, Mencacci A, Delsero G, Dostiani C F, Mosci P, Bacci A, Montagnoli C, Kopf M, Romani L. IFN-gamma is required for IL-12 responsiveness in mice with Candida albicans infection. J Immunol. 1998;161:3543–3550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cenci E, Mencacci A, Spaccapelo R, Tonnetti L, Mosci P, Enssle K H, Puccetti P, Romani L, Bistoni F. T helper cell type-1 (Th1)- and Th2-like responses are present in mice with gastric candidiasis but protective immunity is associated with Th1 development. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1279–1288. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.5.1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chakir J, Cote L, Coulombe C, Deslauriers N. Differential pattern of infection and immune response during experimental oral candidiasis in BALB/c and DBA/2 (H-2d) mice. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1994;9:88–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1994.tb00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cleveland W W, Fogel B J, Brown W T, Kay H E M. Fetal thymic transplant in a case of DiGeorge syndrome. Lancet. 1968;ii:1211–1214. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(68)91694-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cobbold S P, Jayasuriya A, Nash A, Prospero T D, Waldmann H. Therapy with monoclonal antibodies by elimination of T-cell subsets in vivo. Nature. 1984;312:548–551. doi: 10.1038/312548a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coker L A, Mercadal C M, Rouse B T, Moore R N. Differential effects of CD4+ and CD8+ cells in acute, systemic murine candidosis. J Leukoc Biol. 1992;51:305–306. doi: 10.1002/jlb.51.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conlan J W, North R J. Neutrophils are essential for early anti-Listeria defense in the liver, but not in the spleen or peritoneal cavity, as revealed by a granulocyte-depleting monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1994;179:259–268. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamond R D, Clark R A, Haudenschild C C. Damage to Candida albicans hyphae and pseudohyphae by the myeloperoxidase system and oxidative products of neutrophil metabolism in vitro. J Clin Investig. 1980;66:908–917. doi: 10.1172/JCI109958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diamond R D, Haudenschild C C. Monocyte-mediated serum-independent damage to hyphal and pseudohyphal forms of Candida albicans in vitro J. Clin Investig. 1981;67:173–182. doi: 10.1172/JCI110010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elahi S, Pang G, Clancy R, Ashman R B. Cellular and cytokine correlates of mucosal protection in murine model of oral candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5771–5777. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5771-5777.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fidel P L, Jr, Luo W, Chabain J, Wolf N A, Van Buren E. Use of cellular depletion analysis to examine circulation of immune effector function between the vagina and the periphery. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3939–3943. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3939-3943.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fidel P L, Jr, Lynch M E, Sobel J D. Circulating CD4 and CD8 T cells have little impact on host defense against experimental vaginal candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2403–2408. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2403-2408.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fulurija A, Ashman R B, Papadimitriou J M. Neutrophil depletion increases susceptibility to systemic and vaginal candidiasis in mice, and reveals differences between brain and kidney in mechanisms of host resistance. Microbiology. 1996;142:3487–3496. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-12-3487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hestdal K, Ruscetti F W, Ihle J N, Jacobsen S E, Dubois C M, Kopp W C, Longo D L, Keller J R. Characterization and regulation of RB6–8C5 antigen expression on murine bone marrow cells. J Immunol. 1991;147:22–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holub M. Immunology of nude mice. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hurtrel B, Lagrange P H. Comparative effects of carrageenan on systemic candidiasis and listeriosis in mice. Clin Exp Immunol. 1981;44:355–358. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hurtrel B, Lagrange P H, Michel J C. Systemic candidiasis in mice. IL- Main role of polymorphonuclear leukocytes in resistance to infection. Ann Immunol. 1980;131C:105–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itohara S, Farr A G, Lafaille J J, Bonneville M, Takagaki Y, Haas W, Tonegawa S. Homing of a gamma delta thymocyte subset with homogeneous T-cell receptors to mucosal epithelia. Nature. 1990;343:754–757. doi: 10.1038/343754a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jensen J, Vazquez Torres A, Balish E. Poly(1 · C)-induced interferons enhance susceptibility of SCID mice to systemic candidiasis. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4549–4557. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.11.4549-4557.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jensen J, Warner T, Balish E. Resistance of SCID mice to Candida albicans administered intravenously or colonizing the gut: role of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and macrophages. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:912–919. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.4.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jensen J, Warner T, Balish E. The role of phagocytic cells in resistance to disseminated candidiasis in granulocytopenic mice. J Infect Dis. 1994;170:900–905. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.4.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones-Carson J, Vazquez-Torres A, Warner T, Balish E. Disparate requirement for T cells in resistance to mucosal and acute systemic candidiasis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2363–2365. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2363-2365.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klein R S, Harris C A, Small C B, Moll B, Lesser M, Friedland G H. Oral candidiasis in high-risk patients as the initial manifestation of the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:354–358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198408093110602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehrer R I. Measurement of candidacidal activity of specific leukocyte types in mixed cell populations. I. Normal myeloperoxidase deficient and chronic granulomatous disease neutrophils. Infect Immun. 1970;2:42. doi: 10.1128/iai.2.1.42-47.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lundqvist C, Baranov S, Teglund S, Hammarstrom S, Hammarstrom M L. Cytokine profile and ultrastructure of intraepithelial gamma-delta T cells in chronically inflammed human gingiva suggest a cytotoxic effector factor. J Immunol. 1994;153:2302–2312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCarthy G M. Host factors associated with HIV-related oral candidiasis. A review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;73:181–186. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(92)90192-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McCarthy G M, Mackie I D, Koval J, Sandhu H S, Daley T D. Factors associated with increased frequency of HIV-related oral candidiasis. J Oral Pathol. 1991;20:332–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1991.tb00940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morris A G. Interferons. Immunology. 1988;1(Suppl.):43–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murray L J, Lee R, Martens C. In vivo cytokine gene expression in T cell subsets of the autoimmune MRL/Mp-lpr/lpr mouse. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:163–170. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.O'Garra A. Peptide regulatory factors. Interleukins and the immune system 2. Lancet. 1989;i:1003–1005. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92640-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pankhurst C, Peakman M. Reduced CD4+ T cells and severe oral candidiasis in absence of HIV infection. Lancet. 1989;i:672. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poussier P, Julius M. Intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes: the plot thickens. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1185–1189. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.4.1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qian Q, Jutila M A, Van Rooijen N, Cutler J E. Elimination of mouse splenic macrophages correlates with increased susceptibility to experimental disseminated candidiasis. J Immunol. 1994;152:5000–5008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qin S X, Cobbold S, Benjamin R, Waldmann H. Induction of classical transplantation tolerance in the adult. J Exp Med. 1989;169:779–794. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.3.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Regezi J A, Sciubba J J. White lesions. In: Regezi J A, Sciubba JJ, editors. Oral pathology: clinical pathologic correlations. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: W. B. Saunders Company; 1999. pp. 83–121. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rogers H, Unanue E. Neutrophils are involved in acute, nonspecific resistance to Listeria monocytogenes in mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:5090–5096. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.12.5090-5096.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rogers T J, Balish E. The role of activated macrophages in resistance to experimental renal candidiasis. J Reticuloendothel Soc. 1977;22:309–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Romani L. Immunity to Candida albicans: Th1, Th2 cells and beyond. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1999;2:363–367. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(99)80064-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Romani L, Mencacci A, Cenci E, Delsero G, Bistoni F, Puccetti P. An immunoregulatory role for neutrophils in CD4+ T helper subset selection in mice with candidiasis. J Immunol. 1997;158:2356–2362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Romani L, Mencacci A, Tonnetti L, Spaccapelo R, Cenci E, Wolf S, Puccetti P, Bistoni F. Interleukin-12 but not interferon-gamma production correlates with induction of T helper type-1 phenotype in murine candidiasis. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:909–915. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Romani L, Mocci S, Cenci E, Rossi R, Puccetti P, Bistoni F. Candida albicans-specific Ly-2+ lymphocytes with cytolytic activity. Eur J Immunol. 1991;21:1567–1570. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scully C, el Kabir M, Samaranayake L P. Candida and oral candidosis: a review. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1994;5:125–157. doi: 10.1177/10454411940050020101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sim G-K. Intraepithelial lymphocytes and the immune system. Adv Immunol. 1995;58:297–344. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60622-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sohnle P G, Frank M M, Kirkpatrick C H. Mechanisms involved in elimination of organisms from experimental cutaneous Candida albicans infections in guinea pigs. J Immunol. 1976;117:523–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a cytokine at the interface of inflammation and immunity. Adv Immunol. 1998;70:83–243. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60387-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Trinchieri G, Kubin M, Bellone G, Cassatella M A. Cytokine cross-talk between phagocytic cells and lymphocytes: relevance for differentiation/activation of phagocytic cells and regulation of adaptive immunity. J Cell Biochem. 1993;53:301–308. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240530406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trinchieri G, Wysocka M, D'Andrea A, Rengaraju M, Aste-Amezaga M, Kubin M, Valiante N M, Chehimi J. Natural killer cell stimulatory factor (NKSF) or interleukin-12 is a key regulator of immune response and inflammation. Prog Growth Factor Res. 1992;4:355–368. doi: 10.1016/0955-2235(92)90016-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolff S M, Dale D C, Clark R A, Root R K, Kimball H R. The Chediak-Higashi syndrome: studies of host defenses. Ann Intern Med. 1972;76:293–306. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-76-2-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]