Abstract

Background:

Climate change based on temperature, humidity and wind can improve many characteristics of the arthropod carrier life cycle, including survival, arthropod population, pathogen communication, and the spread of infectious agents from vectors. This study aimed to find association between content of disease followed climate change we demonstrate in humans.

Methods:

All the articles from 2016 to 2021 associated with global climate change and the effect of vector-borne disease were selected form databases including PubMed and the Global Biodiversity information facility database. All the articles selected for this short review were English.

Results:

Due to the high burden of infectious diseases and the growing evidence of the possible effects of climate change on the incidence of these diseases, these climate changes can potentially be involved with the COVID-19 epidemic. We highlighted the evidence of vector-borne diseases and the possible effects of climate change on these communicable diseases.

Conclusion:

Climate change, specifically in rising temperature system is one of the world’s greatest concerns already affected pathogen-vector and host relation. Lice parasitic, fleas, mites, ticks, and mosquitos are the prime public health importance in the transmission of virus to human hosts.

Keywords: Climate change, Rising temperature, Vector-borne diseases, Parasitic insects, COVID-19

Introduction

Rapid climate change has weighted long-term effects on humans and natural ecosystems and are overwhelming vector-borne diseases. Rising temperatures favor agricultural pests, diseases and disease vectors (1). Therefore, climate change has already made conditions more conducive to the spread of certain infectious diseases, including Lyme disease, water-borne diseases, and mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue fever (2, 3).

As a medical condition, both fleas and ticks are more common during the warmer months, and malaria is again endemic almost everywhere throughout the year. It is expected that the increase in the number of ticks is due to the fact that winters are generally much warmer than previous years. Climate change most likely determines how and where pathogens appear, including patterns of temperature and precipitation, however, the impending risks are not easy to predict. To help limit the risk of infectious diseases, we should do everything possible to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and limit global warming (4).

In this narrative review, we summarize the type of arthropod-borne diseases face to humans with focusing on the influence of climate change on vector-borne diseases. Moreover, evidence demonstrating the high burden of COVID-19 disease due to potential impacts of climate change are mentioned.

Therefore, we aimed to find the association between content of disease followed climate change we demonstrate in humans.

Methods

All the studies from 2016 to 2021 associated with global climate change and the effect of vector-borne disease were extracted. This short review was conducted through searching databases including PubMed, GBIF and Google scholar. Our last search took place in Nov 2021. In order to include related studies, we used following terms: ‘’ Global Climate Change”, ‘’Vector-borne Diseases”,” Leishmaniasis”, ‘’Mosquitos”, ‘’Ticks”, ‘’Fleas”, ‘’ Global Warming”, ‘’Lice”, ‘’Mites”, ‘’Covid-19” as keywords for titiles or abstracts.

Selection of Studies and Data Extraction:

All articles were separately reviewed by authors, and all evaluated the relevance of each article to the short-review. Fig. 1 shows the information flow of our short-review.

Fig. 1:

The information flow through the phase of short review. Our search was done by using keywords in English. 50 related studies were used between 2016–2021

Results

A growing number of studies confirm that climate change due to air pollutants in particular affects human mortality and the spread of vector-borne diseases (4, 5). Fig. 2 shows the effect of climate change and its negative impact on environmental factors. The accumulation of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, mainly caused by the combustion of fossil fuels, leads to air pollution and heat waves that is disrupting habitual territories and ecosystems. Climate is an important environmental factor for influencing of vector-borne diseases epidemic. Many articles have explored the potential consequences of global climate change, particularly the impact of global warming, on vector-borne diseases (6). Higher average of temperatures as a result of greenhouse gas emissions will increase more severe storms and droughts. Odorless and colorless gas, ozone, carbon monoxide (CO) is mainly produced from automotive exhaust gases, as well as from the production of tools, engines and industrial developments. On the other hand, the increase in water vapor and the formation of ozone on the earth’s surface due to heat waves are linked to a number of health threats. Ozone (O3) is made up of three oxygen atoms in the atmosphere that could have harmful properties if produced in the Earth’s lower atmosphere (7, 8). Along with increasing social sensitivity to mental health complications, global warming, with its impact on the environment, exposes individual health to an increase in communicable diseases, respiratory and allergic disorders (9, 10).

Fig. 2:

The conceivable association of climate change on vector-borne diseases and spread of infectious diseases alongside with other negative impacts on human’s health and environment

The impacts of climate change are likely to be worsen by developing vector-borne viral diseases alongside diseases such as malaria in the tropics and even temperate zones, thus generating extra infectious bites each year. Speaking of the current global warming crisis, coupled with the direct influence of rising temperatures on numerous human health problems such as heat stress and vector-borne diseases (8).

Vector-borne diseases will continue to evolve in a changing world, as they have done throughout history, to continue to plague world health. Among the most climate related diseases, mosquito-borne viral and parasitic diseases are the most worrying. These diseases profoundly limit socioeconomic status and development in countries with the highest infection rates as many of found in the tropics and subtropics area (11). The unequal increase in average nighttime compared to daytime temperatures makes available the ideal temperature for the growth of vector insects and the spread of related diseases (10, 12).

Here, the profound health problem related to the influence of climate change in the onset of arthropod-borne diseases are elucidated.

Vector-borne diseases that put the population at risk in global warming

Vectors are the transmitters of disease-causing organisms; that is, they carry pathogens from one host to another. They are typically species of mosquitoes and ticks capable of transmitting viruses, bacteria or parasites to humans and other warm-blooded hosts, but may also include rodents, which carry the infectious agent from a reservoir to a susceptible host (9, 10). A reservoir, included humans, animals or insects, is the principal habitat in which a pathogen lives and flourishes. Vector-borne diseases such as malaria, dengue fever, Chagas disease, leishmaniasis, trypanosomiasis, schistosomiasis and yellow fever are the infections that are most transmitted by the bite of infected arthropod and cause a significant fraction of the global burden of infectious disease (13–15). Although human leishmaniasis have a variety of clinical range, is the ignored tropical disease, which have a large variety of parasite species, reservoirs and vectors associated in transmission.

The responsible agent the Protoza Leishemania, which has more than 20 species can infect humans and animals via bite of particular species of female sand flies (14). Vector-borne disease cycles are complex systems due to the requisite interactions between arthropod vectors, animal hosts and pathogens that are under the influence of environmental factors that contribute to the variation of disease transmission in complex ways. Arthropod vectors are cold-blooded (ectothermic) and therefore are particularly sensitive to climatic and other environmental factors. Weather effects on vector survival and reproduction rates, vector distribution and abundance; and also influences habitat suitability in addition to year-round biting rates and the reproduction of pathogens within vectors (16–18).

However, climate is only one of many factors influencing vector distribution, such as habitat destruction, land use, pesticide application, and host density. Vector-borne diseases are widespread and transmitted by lice, fleas and hard ticks (ticks and mites), mosquitoes and other vectors that put humans at enormous risk of death (19). Vector borne diseases and their main disease born kinds of them are illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3:

Five main arthropod vectors with their predominant kinds

Lice parasitic insects

Adult body lice are hematophagous ectoparasites with a length of 2.3–3.6 mm that infest people of all races around the world. They lay eggs on clothing and do not live directly on the host, they only take care of them when they feed. Body lice are well known with the prevalence of lice-borne diseases, in which the body louse (Pediculus humanus humanus) infected with the bacterium Rickettsia prowazekii causes epidemic typhus. While endemic recurrent fever and trench fever are spread by human body lice infected with bacteria called Borrelia recurrentis and Bartonella Quintana respectively. Two other lice are the head louse and the crab louse or pubic louse. In the life cycle of body lice, eggs are the most resistant stage to changes in environmental temperatures (17, 20).

Fleas as common external parasites

Fleas are parasitic insects that impact public health through two species, the rat flea Xenopsilla cheopis as a vector of Rickettsia typhi and the cat flea Ctenocephalides felis as a crucial vector of R. felis and sometimes R. typhi. Endemic or flea-borne (murine) typhus caused by the bite of fleas infected with R. typhi . Fleas become infected as they bite reservoir animals such as rats and cats to feed on blood and then spread infections to people while interacting with flea dirt or inhaling infected flea dirt or wiping their eyes. However, flea-borne typhus is less well known and many often infected individuals are confused with viral infections. Fleas will threaten various pets and people as our planet’s climate warms (19, 21).

Mites: insect-like organisms

Acari, a taxon of arachnids, encompasses mites and ticks that identified by the lack of wings and antennae but having four pairs of legs that is vary from the insects. Virtually there are a lot of dissimilar types of mites as much as exist insects that live and grow in various environments. Mites are thoroughly similar to ticks and therefore spread a wide range of infectious microbial diseases. Truthfully, the solitary infectious diseases transmitted by mites are some of which bite or cause irritation to humans as specifically related to asthma, rickettsialpox and scrub typhus. The human being most affected by mites for respiratory disease and the inspiration of asthma, which is the distinct character of the mites (22).

Self-limiting Rickettsia pox disease spread by the bite of an infected mouse mite Liponyssoides sanguineus and caused by the Rickettsia bacterium such as R. akari . One of mites-borne rickettsiosis family known as Orientia tsutsugamushi develops Scrub Typhus with a typhus figure and is transferred to humans from the Trombiculidae mite family (Leptotrombidium deliense and L. akamushi) while feeding on infected rodent hosts. However, cross-infection has sometimes been established between other rodents and humans (22–24).

Ticks as most important vector-borne disease

Ticks are considered to be the most important vector-borne disease that have an emotional impact on health and cause infections and types of disease in humans and other mammals briefly described here (25, 26). Lyme disease, also identified as Lyme borreliosis, is an infectious disease with the Borrelia bacterium spreading from the Ixodes genus of ticks. About a week after the tick bite spot, a red rash or erythema migrans appears as the most common sign of infection along with fever, headache, joint discomfort and neck stiffness, and partial absence of facial movement. (6) The Coxiella burnetii bacterium is responsible for Q fever rarely transmitted to humans by pet tricks. It is commonly mild with signs such as the flu, but it can be a serious illness in people with heart valve complications or a failing immune system (27, 28).

Colorado tick fever, also known as “mountain fever”, is an infectious disease of the Coltivirus that infects hematopoietic cells, mainly erythrocytes and transmitted by the bite of an infected Rocky Mountain wood tick known as Dermacentor andersoni (29).

Tularemia is a human disease known as “rabbit fever” elicited by the bite of the infected dog tick Dermacentor variabilis and the wood tick D. andersoni with Francisella tularensis bacterium. Indications of the disease may include fever, skin ulcers and swollen lymph nodes which also rarely occur pneumonia or throat infections (30). Relapsing fever is a bacterial infection caused by several species of Borrelia spirochetes transmitted to humans by lice or ticks (31). Babesiosis or piroplasmosis is a form of red blood cell infection with very few parasites known as Babesia microti and spread by the black-legged tick I. scapularis . It is thought to be the second largest mammalian shared blood parasite after malaria and often associated with other tick-borne infections such as Lyme disease (32). Ehrlichiosis is transmitted to humans by an infected tick Ambylomma americanum with bacteria from the family Anaplasmataceae, genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma that infect and destroy white blood cells. Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) frequently manifests as meningitis, encephalitis or meningoencephalitis and is caused by the TBE virus infected tick (32–34).

Mosquitoes are important vectors in the transmission of many diseases

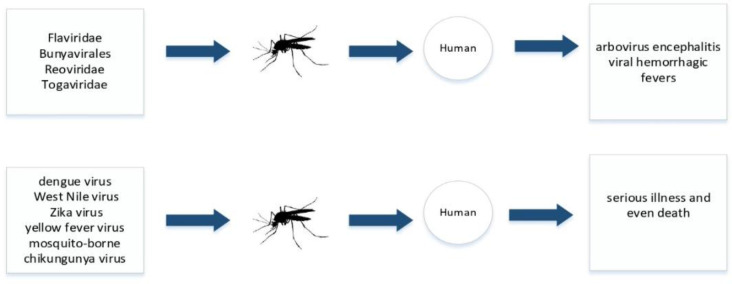

Mosquitoes are of prime public health importance for malaria and mosquito-borne viruses greatly expanded their range of distribution (35, 36). Malaria is a life-threatening disease that occurs via the parasites Plasmodium vivax, P. falciparum and P. ovale of people through the bites of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes (26, 37). However, mosquitoes are widely believed to be emerging infectious such as arbovirus encephalitis and viral hemorrhagic fevers from four main virus groups Flaviviridae, Bunyavirales, Reoviridae, Arboviruses and Togaviridae. Viruses such as dengue virus, West Nile virus, Zika virus, yellow fever virus and mosquito-borne chikungunya virus are responsible for serious illness and even death in humans (Fig. 4) (38–41).

Fig. 4:

Viral agents transmitted to humans through mosquito bites

New challenge of COVID-19 by Climate change

Recent public health problems in the SARS-CoV-2 area have been concentrating into vector-borne diseases for surveillance and prevention. Although there is no confirmation that COVID-19 is capable of spreading via mosquitoes, however, arthropod ectoparasites such as ticks and unnourished cat fleas could potentially play a role in transmitting the virus to their human hosts due to the sequence homology between ectoparasite ACE and human ACE2 protein and its interaction with the viral Spike (42). Furthermore, evolutionary and phylogenetic analyzes of ACE2 among 48 important mammals revealed a potential large array of rodents for SARS-CoV-2. Understanding SARS-CoV-2 animal reservoirs is important for vector-borne COVID-19 community impacted by global climate change.

The role of environmental aspects such as temperature, humidity, and wind speed and air pollution is discussed in recent studies for the transmission of COVID-19. Fig. 5 shows SARSCOV-19 transmission through environmental elements and reaching to the human host.

Fig. 5:

Casual relations of Covid-19 and environmental factors

Air pollution possibly associated with an increased risk of severity and mortality from COVID-19 (43). Even the most recent studies have shown the risk of spreading SARS-COV-2 bioaerosol in the air, in which, infectious bioaerosols can pass up to 6 feet (44). Meteorological parameters such as temperature change and humidity are supposed to be the crucial factors that persuade infectious diseases such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and influenza (45). However, further studies need to clarify that climate change or other environmental factors have arranged for the spread of infectious bio-aerosols. In addition, active measures must be taken to control the source of the infection, block transmission and prevent further spread of COVID-19(46).

Discussion

Climate change poses many risks to human health and increases the threat of emerging diseases in subsequent years (32, 47). Healthcare professionals are increasingly addressing the negative health effects of global climate change and air pollution in their practices, so a rapid response from the government is needed to avoid environmentally damaging activities (48, 49). Current study has shown that climate change has directly generated a promising atmosphere for the boom of numerous bat species, enabling the development of novel coronaviruses and the SARS-CoV-2 strain (32). As a result of the widespread ups and downs of the countryside, the natural habitats of animals are compromised and subsequently increase their interaction with humans by harvesting them the infectious agent transmitted by an arthropod vector from infected reservoir hosts to human or accidental hosts that are primarily pets (41, 50). Therefore, viruses and bacteria along with other infectious agents that trigger the disease, spread more rapidly (31). The COVID-19 pandemic is a case in point to demonstrate how viruses and pathogens move faster r than before and to indicate changes in human behavior. Direct data has not been on climate change persuasion on the extent of COVID-19, however he has been aware that climate change changes the way we communicate to other species on Earth and that the complications to our health and our risk of infections (43). The current association with our nature must be reconsidered in the direction of the sustainable use of existing resources. Producing electricity by burning fossil fuels such as coal, oil and natural gas by increasing the long-term effects associated with air pollution such as chronic asthma, lung failure, stroke, obesity, diabetes and premature death. Reducing air pollution also protects us from the onset of respiratory infections such as coronavirus. To combat climate change, we need to significantly decrease greenhouse gas production by using low-carbon energy bases like wind and solar that keep our lungs healthy. Furthermore, the social and economic challenges associated with water scarcity due to global climate change, especially in areas where the demand for anthropogenesis exceeds supply, must be addressed quickly.

Conclusion

Climate change, specifically in rising temperature system is one of the world’s greatest concerns already affected pathogen-vector and host relation. Lice parasitic insects, Fleas, Ticks and Mosquitos are the principal public health prominence for vector-borne diseases. Therefore, checking, monitoring environmental, and climate changes can help us towards predicting increase of cases involved with vector-born disease. By preventing the vector-born disease’s expansion under climate change conditions, there would be a lot of assistance to further human costs and financial costs of a possible epidemic.

Journalism Ethics considerations

Ethical issues (Including plagiarism, informed consent, misconduct, data fabrication and/or falsification, double publication and/or submission, redundancy, etc.) have been completely observed by the authors.

Acknowledgements

This systematic study was done with the support of the Digestive Disease Research Institute, Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.McDermott-Levy R, Scolio M, Shakya KM, Moore CH. (2021). Factors That Influence Climate Change-Related Mortality in the United States: An Integrative Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 18 (15): 8220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diner RE, Kaul D, Rabines A, Zheng H, Steele JA, Griffith JF, Allen AE. (2021). Pathogenic Vibrio Species Are Associated with Distinct Environmental Niches and Planktonic Taxa in Southern California (USA) Aquatic Microbiomes. mSystems, 6:e0057121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leibovici DG, Bylund H, Bjorkman C, Tokarevich N, Thierfelder T, Evengard B, Quegan S. (2021). Associating Land Cover Changes with Patterns of Incidences of Climate-Sensitive Infections: An Example on Tick-Borne Diseases in the Nordic Area. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 18 (20): 10963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gao H, Wang L, Ma J, Gao X, Xiao J, Wang H. (2021). Modeling the current distribution suitability and future dynamics of Culicoides imicola under climate change scenarios. PeerJ, 9:e12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poursafa P, Kelishadi R. (2011). What health professionals should know about the health effects of air pollution and climate change on children and pregnant mothers. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res, 16:257–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giesen C, Roche J, Redondo-Bravo L, Ruiz-Huerta C, Gomez-Barroso D, Benito A, Herrador Z. (2020). The impact of climate change on mosquito-borne diseases in Africa. Pathog Glob Health, 114:287–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El-Sayed A, Kamel M. (2020). Climatic changes and their role in emergence and re-emergence of diseases. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, 27:22336–22352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rossati A. (2017). Global Warming and Its Health Impact. Int J Occup Environ Med, 8:7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cheng J, Bambrick H, Yakob L, Devine G, Frentiu FD, Toan DTT, Thai PQ, Xu Z, Hu W. (2020). Heatwaves and dengue outbreaks in Hanoi, Vietnam: New evidence on early warning. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 14:e0007997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carnes BA, Staats D, Willcox BJ. (2014). Impact of climate change on elder health. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci, 69:1087–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohamadkhani A, Pourasgari M, Poustchi H. (2018). Significant SNPs Related to Telomere Length and Hepatocellular Carcinoma Risk in Chronic Hepatitis B Carriers. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 19:585–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ng E, Ren C. (2018). China’s adaptation to climate & urban climatic changes: A critical review. Urban Clim, 23:352–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ewing DA, Purse BV, Cobbold CA, White SM. (2021). A novel approach for predicting risk of vector-borne disease establishment in marginal temperate environments under climate change: West Nile virus in the UK. J R Soc Interface, 18:20210049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Akhavan AA, Shirzadi MR, Rassi Y, Khamesipour A, Hanafi-Bojd AA, Vatandoost H. (2019). Conducting International Diploma Course on Leishmaniasis and Its Control in the Islamic Republic of Iran. J Arthropod Borne Dis, 13:234–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR. (2016). Control of Phlebotomine Sand Flies in Iran: A Review Article. J Arthropod Borne Dis, 10:429–444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tahir D, Davoust B, Parola P. (2019). Vector-borne nematode diseases in pets and humans in the Mediterranean Basin: An update. Vet World, 12:1630–1643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Salant H, Mumcuoglu KY, Baneth G. (2014). Ectoparasites in urban stray cats in Jerusalem, Israel: differences in infestation patterns of fleas, ticks and permanent ectoparasites. Med Vet Entomol, 28:314–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Desenclos JC. (2011). Transmission parameters of vector-borne infections. Med Mal Infect, 41:588–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chiuya T, Masiga DK, Falzon LC, Bastos ADS, Fevre EM, Villinger J. (2021). Tick-borne pathogens, including Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever virus, at livestock markets and slaughterhouses in western Kenya. Transbound Emerg Dis, 68:2429–2445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramos JM, Malmierca E, Reyes F, Tesfamariam A. (2008). Results of a 10-year survey of louse-borne relapsing fever in southern Ethiopia: a decline in endemicity. Ann Trop Med Parasitol, 102:467–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammond TT, Hendrickson CI, Maxwell TL, Petrosky AL, Palme R, Pigage JC, Pigage HK. (2019). Host biology and environmental variables differentially predict flea abundances for two rodent hosts in a plague-relevant system. Int J Parasitol Parasites Wildl, 9:174–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wei CY, Wang JK, Shih HC, Wang HC, Kuo CC. (2020). Invasive plants facilitated by socioeconomic change harbor vectors of scrub typhus and spotted fever. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 14:e0007519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seto J, Suzuki Y, Nakao R, Otani K, Yahagi K, Mizuta K. (2017). Meteorological factors affecting scrub typhus occurrence: a retrospective study of Yamagata Prefecture, Japan, 1984–2014. Epidemiol Infect, 145:462–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Valiente Moro C, Chauve C, Zenner L. (2005). Vectorial role of some dermanyssoid mites (Acari, Mesostigmata, Dermanyssoidea). Parasite, 12:99–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stone BL, Tourand Y, Brissette CA. (2017). Brave New Worlds: The Expanding Universe of Lyme Disease. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis, 17:619–629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meredith WH, Eppes SC. (2017). Climate Change:: Vector-Borne Diseases and Their Control; Mosquitoes and Ticks. Dela J Public Health, 3:52–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kersh GJ, Fitzpatrick K, Pletnikoff K, Brubaker M, Bruce M, Parkinson A. (2020). Prevalence of serum antibodies to Coxiella burnetii in Alaska Native Persons from the Pribilof Islands. Zoonoses Public Health, 67:89–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Awaidy SA, Al Hashami H. (2020). Zoonotic Diseases in Oman: Successes, Challenges, and Future Directions. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis, 20:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yendell SJ, Fischer M, Staples JE. (2015). Colorado tick fever in the United States, 2002–2012. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis, 15:311–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andersen LK, Davis MD. (2017). Climate change and the epidemiology of selected tick-borne and mosquito-borne diseases: update from the International Society of Dermatology Climate Change Task Force. Int J Dermatol, 56:252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moradi-Asl E, Jafari S. (2020). The habitat suitability model for the potential distribution of Ornithodoros tholozani (Laboulbene et Megnin, 1882) and Ornithodoros lahorensis (Neumann, 1908) (Acari: Argasidae): the main vectors of tick-borne relapsing fever in Iran. Ann Parasitol, 66:357–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ginsberg HS, Couret J, Garrett J, Mather TN, LeBrun RA. (2021). Potential Effects of Climate Change on Tick-borne Diseases in Rhode Island. R I Med J (2013), 104:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alkishe A, Raghavan RK, Peterson AT. (2021). Likely Geographic Distributional Shifts among Medically Important Tick Species and Tick-Associated Diseases under Climate Change in North America: A Review. Insects, 12(3): 225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilhelmsson P, Jaenson TGT, Olsen B, Waldenstrom J, Lindgren PE. (2020). Migratory birds as disseminators of ticks and the tick-borne pathogens Borrelia bacteria and tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) virus: a seasonal study at Ottenby Bird Observatory in South-eastern Sweden. Parasit Vectors, 13:607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gubler DJ, Clark GG. (1996). Community involvement in the control of Aedes aegypti. Acta Trop, 61:169–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mayer SV, Tesh RB, Vasilakis N. (2017). The emergence of arthropod-borne viral diseases: A global prospective on dengue, chikungunya and zika fevers. Acta tropica, 166:155–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vatandoost H, Hanafi-Bojd AA, Raeisi A, Abai MR, Nikpour F. (2018). Bioecology of Dominant Malaria Vector, Anopheles superpictus s.l. (Diptera: Culicidae) in Iran. J Arthropod Borne Dis, 12:196–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolawole OM, Adelaiye G, Ogah JI. (2018). Emergence and Associated Risk Factors of Vector Borne West Nile Virus Infection in Ilorin, Nigeria. J Arthropod Borne Dis, 12:341–350. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Staji H, Keyvanlou M, Geraili Z, Shahsavari H, Jafari E. (2021). The First Study of West Nile Virus in Feral Pigeons (Columba livia domestica) Using Conventional Reverse Transcriptase PCR in Semnan and Khorasane-Razavi Provinces, Northeast of Iran. J Arthropod Borne Dis, 15:136–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nejati J, Zaim M, Vatandoost H, et al. (2020). Employing Different Traps for Collection of Mosquitoes and Detection of Dengue, Chikungunya and Zika Vector, Aedes albopictus, in Borderline of Iran and Pakistan. J Arthropod Borne Dis, 14:376–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choubdar N, Oshaghi MA, Rafinejad JM, et al. (2019). Effect of Meteorological Factors on Hyalomma Species Composition and Their Host Preference, Seasonal Prevalence and Infection Status to Crimean-Congo Haemorrhagic Fever in Iran. J Arthropod Borne Dis, 13:268–283. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lam SD, Ashford P, Diaz-Sanchez S, Villar M, Gortazar C, de la Fuente J, Orengo C. (2021). Arthropod Ectoparasites Have Potential to Bind SARS-CoV-2 via ACE. Viruses,13(4): 708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Z, Huang BZ, Sidell MA, et al. (2021). Near-roadway air pollution associated with COVID-19 severity and mortality - Multiethnic cohort study in Southern California. Environ Int, 157:106862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eslami H, Jalili M. (2020). The role of environmental factors to transmission of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). AMB Express, 10:92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma Y, Zhao Y, Liu J, et al. (2020). Effects of temperature variation and humidity on the death of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China. Sci Total Environ, 724:138226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu Y, Jing W, Liu J, Ma Q, Yuan J, Wang Y, Du M, Liu M. (2020). Effects of temperature and humidity on the daily new cases and new deaths of COVID-19 in 166 countries. Sci Total Environ, 729:139051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Swei A, Couper LI, Coffey LL, Kapan D, Bennett S. (2020). Patterns, Drivers, and Challenges of Vector-Borne Disease Emergence. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis, 20:159–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eckelman MJ, Sherman JD. (2018). Estimated Global Disease Burden From US Health Care Sector Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Am J Public Health, 108:S120–S122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ahmadnejad F, Otarod V, Fathnia A, Ahmadabadi A, Fallah MH, Zavareh A, Miandehi N, Durand B, Sabatier P. (2016). Impact of Climate and Environmental Factors on West Nile Virus Circulation in Iran. J Arthropod Borne Dis, 10:315–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ajith Y, Dimri U, Madhesh E, et al. (2020). Influence of weather patterns and air quality on ecological population dynamics of ectoparasites in goats. Int J Biometeorol, 64:1731–1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]