Abstract

Background

Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expressions and its modulation are of great interest as being a key receptor for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV2) and the protective arm of the rennin‐angiotensin axis, maintaining cardiovascular homeostasis. However, ACE2 expressions and their modulation in the healthy and disease background are yet to be explored.

Method

We performed a meta‐analysis, extracting the data for ACE2 expression in human subjects with various diseases, including SARS‐CoV2 infection without or with co‐morbidity. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed. Out of 203 studies, 39 met the inclusion criteria with SARS‐CoV2 patients without co‐morbidity, SARS‐CoV2 patients with co‐morbidity, cardiovascular (CVD) patients, diabetes patients, kidney disorders patients, pulmonary disease patients, and other viral infections patients.

Results

Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 expression was significantly increased in all diseases. There was an elevated level of ACE2, especially membrane‐bound ACE2, in COVID‐19 patients compared to healthy controls. A statistically significant increase in ACE2 expression was observed in CVD patients and patients with other viral diseases compared to healthy subjects. Moreover, subgroup analysis of ACE2 expression as soluble and membrane‐bound ACE2 revealed a remarkable increase in membrane‐bound ACE2 in CVD patients, patients with viral infection compared to soluble ACE2 and pooled standard mean difference (SMD) with the random‐effects model was 0.37 and 2.23 respectively.

Conclusion

It was observed that utilizing the ACE2 by SARS‐CoV2 for its entry and its consequence leads to several complications. So there is a need to investigate the underlying mechanism along with novel therapeutic strategies.

Keywords: cardiovascular diseases, membrane‐bound ACE2, RAS, SARS‐CoV2, soluble ACE2

Our review and meta‐analysis substantially add novel knowledge to our understanding of ACE2 expression pattern, its dynamic as soluble and membrane‐bound form. An elevated level of ACE2 in patients with all diseases was observed. Moreover, membrane‐bound ACE2 was remarkably high in patients with SARS‐CoV2 infected patients having co‐morbidities, cardiovascular diseases, and other viral diseases compared to healthy population.

Abbreviations

- ACE2

Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2

- CVD

Cardiovascular

- EC number

Enzyme Commission number

- HPA

Human Protein Atlas

- PCT

Proximal convoluted tubule

- PRISMA

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses

- RAS

Renin‐angiotensin system

- RBD

Receptor‐binding domain

- SARS‐CoV2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SMD

Standard Mean Difference

- TMPRSS2

Transmembrane serine protease 2

1. INTRODUCTION

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV2) is the seventh coronavirus spread all over the globe since December 2019, and the disease is called COVID‐19. Earlier found coronaviruses were SARS‐CoV, MERS‐CoV, SARS‐CoV‐2 HKU1, NL63, OC43, 229 E and were reported to cause mild to severe symptoms. However, SARS‐CoV2 led to unusual pathophysiology pressing the global economy, health at the hardest. 1 , 2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 has a high affinity for angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2; EC number – 3.4.17.23), and ACE2 is another enzyme involved in the renin‐angiotensin system (RAS). The active end product of the RAS cascade is Angiotensin II (AngII), derived from angiotensin I (Ang I), and angiotensin‐converting enzyme (ACE; EC number ‐ 3.4.15.1), commonly found in vascular endothelial cells and lungs, catalyses the process. It is a classical arm of the RAS system. Ang II acts on angiotensin receptors AT1 and AT2. The activation of the AT1 receptors results in vasoconstriction, inflammatory, prothrombotic and arrhythmogenic effects, whereas activation of AT2 receptors antagonize the action of AT1. ACE2 further degrades Ang II into angiotensin 1–7 (Ang‐ (1–7)), and it acts on the MAS receptor. The activation of MAS receptors causes vasodilation, anti‐inflammatory, thrombotic and anti‐arrhythmogenic effects, and it is called a protective arm of the RAS system (Figure S1).

Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 acts as a receptor of the SARS‐CoV2 protein and facilitates virus entry into host cells, as depicted in Figure S2. The S‐protein of SARS‐CoV2 SPIKE protein binds to ACE2 receptors of host cells and activates viral spike glycoprotein and cleavage of a c‐terminal segment of ACE2 by proteases like transmembrane serine protease 2 (TMPRSS2) and FURIN, which express mainly in lung tissues. Followed by the fusion with the ACE2 receptor, it delivers the viral nucleo‐capsid inside the cell for subsequent replication. The S‐protein is responsible for syncytial generation between infected cells and other receptor‐bearing cells. 3 , 4

Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 has a major role in the development of diabetes and in diabetic nephropathy (Figure S3). In pancreatic acini and islet, the distribution of ACE2 is similar to that of ACE, while in the kidney, it is present in the proximal convoluted tubule (PCT) and in the glomerulus. ACE2 is the main target to reduce Ang II expression for treating kidney diseases in diabetic conditions because it is evident that there is a decrease in ACE2 expression associated with albuminuria and glomerular lesions disorder. 5 Ang II is highly expressed in the pancreas with low levels of Ang (1–7), and the expression is several fold high in the pancreas compared to plasma, denoting their role in pancreatic functioning. Blockade of Ang II or angiotensin receptors had been associated with increase blood flow and insulin secretion. Several preclinical and clinical studies reported the restoration of glucose homeostasis with RAS pathway inhibition against the diabetic disease backdrop and improvement in clinical outcome. Attenuated ACE2 levels had also been associated with diabetes. 6 The plausible underlying mechanism would be a reduced ACE2 expression causing an elevation of Ang II proteins, which delays insulin secretion and decreases blood flow to the islets of Langerhans. Thus the use of ACE inhibitors or Angiotensin II antagonists decreases the incidence of type II diabetes mellitus. 6 , 7 , 8

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 attenuates the ACE2 levels, essential for the conversion of Ang II to Ang (1–7). Thus, Ang II accumulates and binds to the angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1R) on the immune cell membrane; this process activates the NF‐κB pathway. It, in turn, induces IL‐6, TNF‐α, IL‐1β, and IL‐10 production. Ang II activates AT1R and regulates mitogen‐activated protein kinases (MAPK) (ERK1/2, JNK, p38MPK) to release the cytokines IL‐1, IL‐10, IL‐12, and TNF‐α. 9

The present review and meta‐analysis were designed with the following objectives.

To determine the expression of ACE2 in various diseases like COVID‐19, COVID‐19 with comorbidity, other viral infections, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, pulmonary diseases and kidney diseases.

To evaluate the ACE2 expression comparing soluble and membrane‐bound ACE2 in all diseases.

To analyse the effect of associated co‐morbidity on the ACE2 expression in COVID‐19.

To determine the correlation between various diseases and disorders concerning ACE2 expression using various statistical methods.

2. METHODS

2.1. Search strategy and selection criteria

The ACE2 expression in patients with SARS‐CoV‐2, other diseases and disorders (cardiovascular diseases (CVD), diabetes, pulmonary disorders, kidney disorders, other viral infections) retrieved from National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). In addition, a search was performed using SCOPUS, WEB OF SCIENCE databases with keywords alone or a combination of them (ACE2, its expression in various diseases, Protein expression of ACE2, mRNA expression of ACE2 in patients having SARS‐CoV‐2, diabetes, pulmonary diseases, CVS, kidney diseases, ACE2 expression in viral infection). Further, the reference list of selected articles was screened as a complementary search. The articles published in the English language were selected. In this study, information on the detection of ACE2 levels either as mRNA or protein using various methods is included. Next, the collected data from different articles were categorized into several groups according to the disease and co‐morbidities associated with the disease. The ACE2 expression is segregated into membrane‐bound ACE2 and soluble ACE2 in circulation. Reporting of the study conforms to broad EQUATOR guidelines. 10 The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed. 11 The protocol was registered in the registry PROSPERO (CRD42022302513).

2.2. Inclusion criteria

The studies that reported ACE2 expression in patients with different diseases were included. 5 , 7 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 Following the removal of duplicate datasets, the unique datasets were collected. All biopsies' studies related to ACE2 expression in various diseases were also included in the study. Articles were initially screened by titles and abstracts, followed by a full article review to identify eligible studies. Original research articles included if they fulfilled the criteria and provided the data of clinical features and outcome of patients having laboratory‐confirmed tests showing the infection, COVID‐19, and other diseases. The studies having healthy and disease subjects were included for analysis. Discordant results were resolved by discussion between the authors of the studies. Studies reporting haematological, biochemistry and serological laboratory tests, as well as COVID‐19 related comorbidities and clinical outcomes, were selected. The study provided usable quantitative data for estimating 95% confidence intervals. Other information about the ACE2 at mRNA and protein levels across human tissues and recorded pathologies were gathered from Human Protein Atlas (HPA) database for reference purpose only.

2.3. Exclusion criteria

We excluded animal studies, review articles, and consensus documents. The exclusion criteria were as follows:

Review articles, abstracts, letters to the editor, clinical trials, animal studies, comments and consensus documents were excluded from the study.

The study did not focus on patients with COVID‐19, diabetes, CVD, Pulmonary diseases, other viral infections or kidney disorders, as well as when the diagnosis was unclear.

Studies that included animal‐based experiments and duplicates of previous publications.

Studies with in vitro cell‐based assays and unpublished studies.

2.4. Data extraction and statistical analysis

Data were extracted from the studies considering key characteristics including author(s), publication year, journal name, country, and type of study, the race of patients, ACE2 expression, either soluble or membrane‐bound, laboratory findings, comorbidities and final clinical outcomes (Table 1 and Table S1).

TABLE 1.

Details of selected studies

| Study | Journal Name | Population | Type of population | Method of detection | Soluble or membrane bound ACE2 (sACE2 or mACE2) | Tissue / expression site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wijnant et al 2020 | Diabetes | 106 | Caucasian | RTPCR (Protein expression) | mACE2 | Lung tissue |

| G.Y. Oudit et al 2009 | European Journal of Clinical Investigation | 20 | Caucasian | RTPCR and Western blot | mACE2 | Autopsy of heart tissue |

| HN Reich et al 2008 | Kidney International | 21 | Caucasian | Immuno‐histochemistry &RTPCR | mACE2 | Renal biopsies |

| Batlle et al 2006 | The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation | 12 | Caucasian | RTPCR | mACE2 | Left ventricular biopsies |

| Purushothaman et al 2013 | Cardiovascular Pathology | 24 | Caucasian | Immunohistochemistry | mACE2 | Arteries |

| Sharif‐Askari et al 2020 | Molecular Therapy: Methods &Clinical Development | 541 | Caucasian | Microarray expression (PBMC) | mACE2 | Lung airway and peripheral blood mononuclear cells |

| Xiao et al 2012 | PLoS ONE | 150 | Caucasian | ELISA (solubleACE2) | sACE2 | Urine |

| Yang et al 2017 | RENALFAILURE | 360 | Asian | ELISA (with HD) | sACE2 | Venous blood samples |

| Guo et al. 2020 | Cellular Physiology | 18 | – | Immunofluorescence (H929andcalu3cells) | mACE2 | Normal and fibrotic lung tissues, normal and failed heart tissue. |

| Hongjing Gu et al 206 | Scientific Reports | 54 | Asian | Western blot and histology | sACE2 | Plasma* |

| Smith et al 2020 | Developmental Cell | Caucasian | RTPCR (Human airway epithelial cells) | mACE2 | Expression studies (Mouse lungs) | |

| Chen et al 2020 | European Society of Cardiology | 55 | Asian | RTPCR | mACE2 | Human heart tissue |

| Goulter et al 2014 | BMC Medicine | 32 | Caucasian | QRTPCR | mACE2 | Human ventricular myocardium |

| Liu H and Zhe zang et al 2020 | European Society of Cardiology | 20 | Caucasian | QRTPCR | mACE2 | Human colorectal tumour and colorectal normal tissues |

| Ramachand et al 2018 | PLoS ONE | 79 | Asian | Fluorescent assay | mACE2 | Fasting blood samples |

| Anguiano et al. 2015 | Nephrol Dial Transplant | 2572 | Caucasian | Fluorescent assay | sACE2 | Plasma |

| Trojanowics et al. 2016 | Nephrol Dial Transplant | 61 | Caucasian | RTPCR&westernblot | mACE2 | Monocytes |

| SE Park et al 2013 | NephrolDialTransplant | 621 | Asian | ELISA | sACE2 | Blood |

| Herman‐Edelstein et al 2021 | CardiovascularDiabetology | 79 | Caucasian | QRTPCR & ELISA | mACE2 | Right atrial tissues |

| MARobert et al 2013 | Nephroldialtransplant | 159 | Caucasian | QUENCHED FLUORESCENCESUBSTRATEBASEDASSAY | sACE2 | Blood |

| Osman et al 2021 | Frontier microbiology | 44 | Caucasian | RTPCR | mACE2 | Blood |

| T E Walters et al 2016 | European society of cardiology | 45 | Caucasian | quenched fluorescence assay | sACE2 | Blood |

| van lier D et al 2021 | Europen respiratory society | 15 | Caucasian | LC–MS | sACE2 | Blood |

| S K Patel et al 2021 | Europen respirtaory journal | 70 | Caucasian | ELISA | sACE2 | Blood plasma |

| Peters et al 2020 | American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine | 409 | Caucasian | RTPCR | mACE2 | Sputum cells |

| G Li et al 2020 | Journal of autoimmunity | 183 | Asian | RTPCR | mACE2 | Data from six independent studies (Lung tissue) |

| L He et al 2006 | Journal of pathology | 5 | Asian | Immunohistochemistry | mACE2 | Lung tissue, heart tissue, etc. |

| Bao et al 2021 | Journal of inflammatory research | 64 | Asian | RTPCR | mACE2 | Lung tissue |

| Tue W Kragstrup et al 2021 | European respiratory journal | 384 | Caucasian | RTPCR | sACE2 | Blood |

| Michal Herman Edelstein et al 2021 | Cardiovascular Diabetology | 79 | Caucasian | RT‐ PCR & immunohistochemistry | mACE2 | Atrial biopsies |

| Elemam et al 2021 | International journal of molecular science | 100 | Caucasian | qRTPCR | sACE2 | Serum |

| Cousele‐Seijas et al 2020 | European Journal of Clinical Investigation | 43 | Caucasian | ELISA | sACE2 | Epicardial and subcutaneous fat biopsies |

We calculated Standard Mean Difference (SMD) for continuous data with a 95% confidence interval (CIs). Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using inconsistency index (I 2) statistics. When I 2 > 50%, a random‐effects model was selected. The p‐value <.05 and I 2 ≥ 50% were considered to have significant heterogeneity. The risk bias analysis was done and presented as a matrix and summary graph. The forest plot was used to assess the overall effect of the included studies. All data were analysed using RevMan software version 5.4.1, The Cochrane collaboration 2020. 44

As ACE2 expression was archived from studies having different methods of ACE2 measurement, the data was subjected to normalization. The ACE2 expression in disease patients was calculated as a fold change compared to healthy subjects, as depicted in Tables S2–S8.

We performed statistical analysis of the transformed and pooled data using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Prism Version 9.2) software. The data were analysed using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis test for multiple variable analysis and comparison. We used a two‐tailed p‐value with a statistical significance threshold of .05. Correlation coefficients were calculated using the Spearman correlation coefficient method for subgroup analysis.

2.5. Assessment of methodological quality

Please see Appendix S1.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search strategy and study design

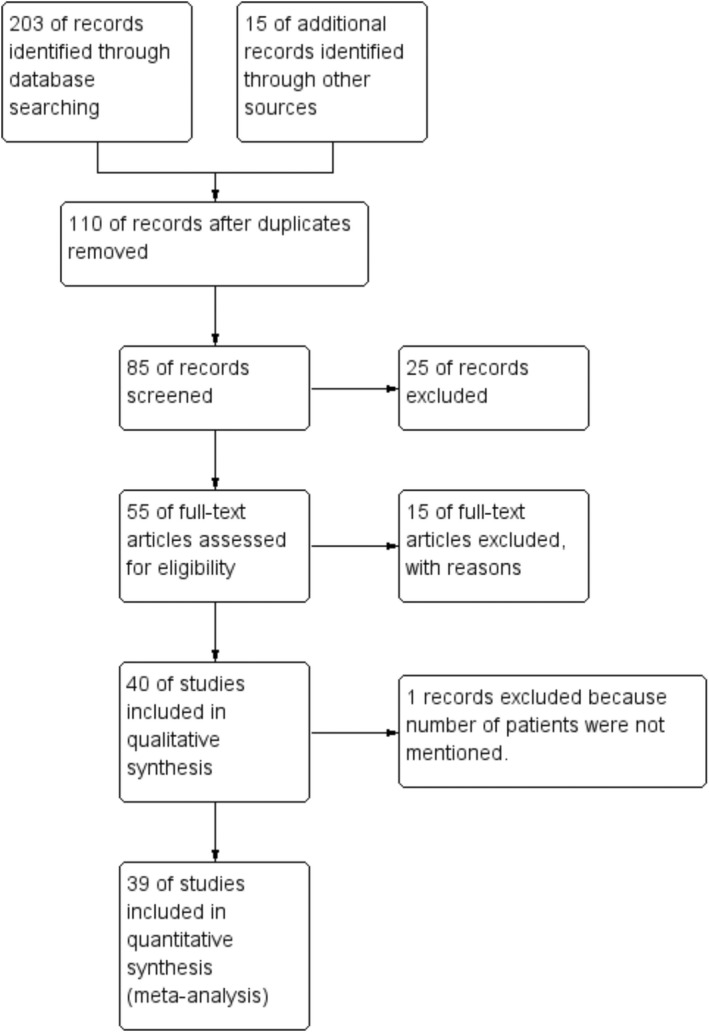

Total 203 studies were identified according to the search criteria. After removing duplicated records, records noncompliant with inclusion criteria, and reviewing abstracts and titles, 55 articles were selected for the study. However, 15 articles did not report the number of healthy or disease subjects, hence those articles were removed. Finally, 39 articles (n = 39) were selected for meta‐analysis, as shown in a flow diagram (Figure 1 and Tables S1 and S2). These studies include 4686 subjects with diseases (COVID‐19, Diabetes, Cardiovascular diseases (CVD), Pulmonary infections, Viral infections, Kidney disorders) and 3040 healthy subjects. [(1–15)].

FIGURE 1.

Studies included in the review and meta‐analysis is depicted using a PRISMA flow chart.

The expression of ACE2 for different diseases and healthy subjects was summarized in Table 1 and Table S1. The populations of the included studies are of Caucasian and Asian origin. The expression of ACE2 was detected with various techniques like RT‐PCR, ELISA, Western blot, and Fluorescent assay, as depicted in Table 1. Of these 39 articles, five articles compared ACE2 expression in COVID‐19 patients, nine articles compared ACE2 expression in cardiovascular disease (CVD), eight articles compared in diabetic patients, four articles compared in pulmonary diseases, three articles compared in kidney disease, five articles in other viral infection and six articles compared in COVID19 patients with either DM or CVD.

The expression of ACE2 data was selected for meta‐analysis, depicted in Table S1. The ACE2 expression for nonparametric statistical analysis was normalized, and fold changes were calculated, and soluble ACE2 is highlighted (Tables S2–S8).

3.2. Meta‐analysis of ACE2 expression in all diseases vs. healthy subjects

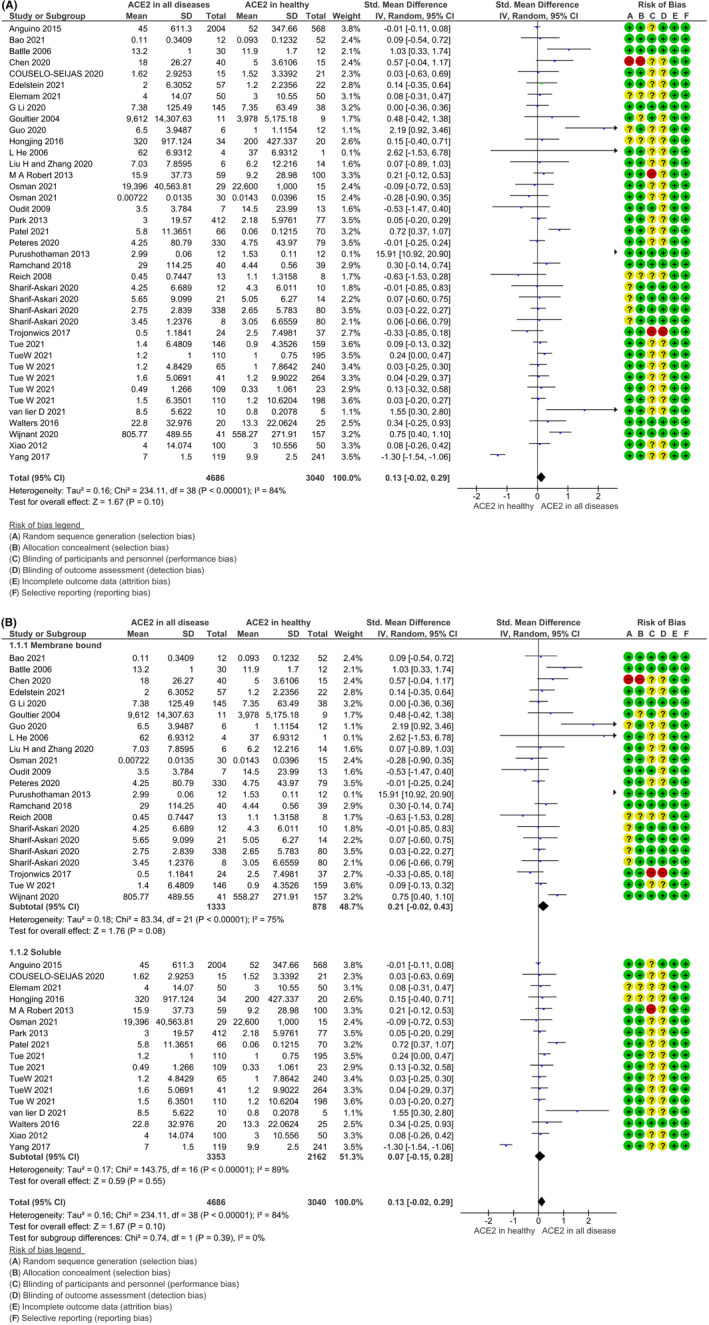

The meta‐analysis of ACE2 expression in all diseases compared with healthy subjects is depicted in Figure 2A. The level of ACE2 was significantly higher in subjects with diseases as compared to healthy subjects, and pooled standard mean difference (SMD) with the random‐effects model was .13, 95% CI: −.02, .29, z = 1.67, p = .10, as shown in Figure 2A. The included studies contributed to high heterogeneity I 2 = 84% with τ2 = .16, Chi2 = 234.11, df = 38, p < .00001.

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot of studies, which measured (A) Total angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) (B) soluble and membrane bound ACE2 in diseases compared to healthy subjects. The overall effect size was presented as the standard mean difference with 95% CI and inverse variance (IV) method. The square (blue colour) represents the sample size and corresponding weightage.

The ACE2 is present in the human body as free circulating ACE2, termed as soluble ACE2, as well as membrane‐bound ACE2. Therefore, we segregated the data into ACE2 soluble and membrane‐bound ACE2 in disease patients and subjected them for analysis to evaluate the predominance of any form in the backdrop of disease, as shown in Figure 2B. The subgroup analysis of ACE2 expression as membrane‐bound ACE2 (mACE2) and soluble ACE2 (sACE2) showed higher membrane‐bound ACE2 in all diseases compared to a soluble form. The pooled standard mean difference (SMD) with the random‐effects model for membrane bound ACE2 was .21, 95% CI: −.02, .43, z = 1.76, p = .008, as shown in Figure 2B. The 75% heterogeneity was observed with included studies.

3.3. ACE2 expression in COVID‐19 without comorbidities and COVID‐19 with co‐morbidities

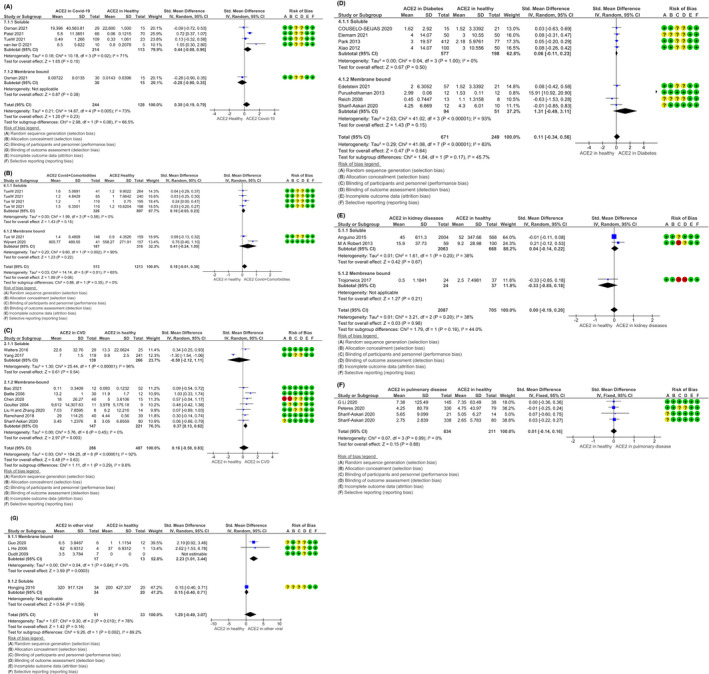

The membrane‐bound and soluble ACE2 expression in COVID‐19 patients without comorbidities were analysed and compared with healthy subjects. The soluble ACE2 expression was higher in subjects with COVID‐19 as compared to healthy subjects, and pooled standard mean difference (SMD) with the random‐effects model was .44, 95% CI: −.08, .96; z = 1.65 (p = .10). The included studies showed high heterogeneity 71% (τ2 = .21, Chi2 = 14.67, df = 4, p = .005, I 2 = 73%) (Figure 3A). The membrane‐bound ACE2 was lower in COVID‐19 patients without any comorbidities (Figure 3A), and pooled standard mean difference (SMD) with the random‐effects model was −.28, 95% CI: −.19, .79; z = .87 (p = .38).

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot of studies, which measured soluble and membrane‐bound angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 in (A) COVID19 patients, (B) COVID19 patients with comorbidities, (C) cardiovascular (CVD) patients, (D) diabetes patients, (E) kidney disorders patients, (F) pulmonary disease patients and (G) patients with other viral infection compared to healthy subjects. The overall effect size was presented as the standard mean difference with 95% CI and inverse variance (IV) method. The square (blue colour) represents the sample size and corresponding weightage.

The membrane–bound and soluble ACE2 levels in COVID‐19 patients with comorbidities (Table S1) were found to be high compared to healthy subjects, as shown in Figure 3B. The pooled standard mean difference for membrane‐bound ACE2 was .41, and 95% CI: −.24, 1.05; z = 1.23 (p = .22). The included studies showed heterogeneity of 90% (τ2 = .2, Chi2 = 9.6, df = 1, p = .02, I 2 = 90%) (Figure 3B). The SMD for soluble ACE2 was .10, 95% CI: −.03, .23; z = 1.43 (p = .15). The included studies showed heterogeneity of 0% (τ2 = .00, Chi2 = 1.99, df = 3, p = .58, I 2 = 0%).

3.4. ACE2 expression in CVD

As shown in Figure 3C, the membrane‐bound ACE2 expression was significantly higher in subjects with CVD as compared to healthy subjects, and pooled standard mean difference (SMD) with the random‐effects model was .37, 95% CI: .13, .62, z = 2.97 (p = .003). Heterogeneity was found to be 0% (τ2 = .00, Chi2 = 5.76, df = 6, p = .45, I 2 = 0%). The soluble ACE2 expression was in favour of healthy than CVD patients and pooled SMD was −.50, 95% CI: −2.12, 1.11, z = .61 (p = .54) with significant heterogeneity and it was 96% (τ2 = 1.30, Chi2 = 25.44, df = 1, p < .00001, I 2 = 96%).

3.5. ACE2 expression in diabetes

The membrane‐bound and soluble ACE2 expression in diabetes patients did not differ significantly compared to healthy subjects (Figure 3D). The pooled standard mean difference (SMD) with the random‐effects model for membrane bound ACE2 was 1.31, 95% CI: −.49, 3.11, z = 1.43, p = .64. Heterogeneity was found to be 93%, with τ2 = 2.63, Chi2 = 41.02, df = 3, p < .00001, as depicted in Figure 3D. The soluble ACE2 SMD was 0, 06, 95% CI: −.11, .23, z = .67, p = .50. Heterogeneity was found to be 0%, with τ2 = 0, Chi2 = .04, df = 3, p < .00001.

3.6. ACE2 expression in kidney diseases

As shown in Figure 3E, the soluble and membrane‐bound ACE2 expression did not change in patients with kidney diseases in comparison to healthy subjects. However, the soluble ACE2 was higher in kidney patients compared to membrane‐bound. The pooled standard mean difference (SMD) with the random‐effects model for soluble ACE2 was .04, 95% CI: −.14, .22; z = .42, p = .67. Heterogeneity was found to be I 2 = 38%, with τ2 = .01, Chi2 = 1.61, df = 1, p = .20. For membrane‐bound ACE2, SMD was −.33, 95% CI: −.85, .18; z = 1.27, p = .21.

3.7. ACE2 expression in pulmonary diseases

The membrane‐bound ACE2 expression did not differ between pulmonary diseases patients and healthy subjects, and pooled standard mean difference (SMD) with the random‐effects model was .01, 95% CI: −.14, .16; z = .15, p = .88. Heterogeneity was found to be 0% (τ2 = .00, Chi2 = .07, df = 3, p = .99, I 2 = 0%) (Figure 3F).

3.8. ACE2 expression in other viral infections

The analysis of membrane‐bound ACE2 levels indicated a difference in patients with a viral infection and healthy subjects, and pooled standard mean difference (SMD) with the random‐effects model was 2.23, 95% CI: −1.01, 3.44, z = 3.59, p = .0003 (Figure 3F). Heterogeneity was found to be I 2 = 0%, with τ2 = .00, Chi2 = .04, df = 1, p = .84. The soluble ACE2did does not show any difference in healthy and disease subjects, as depicted in Figure 3F.

3.9. Multivariate analysis of ACE2 expression in all diseases vs. healthy subjects

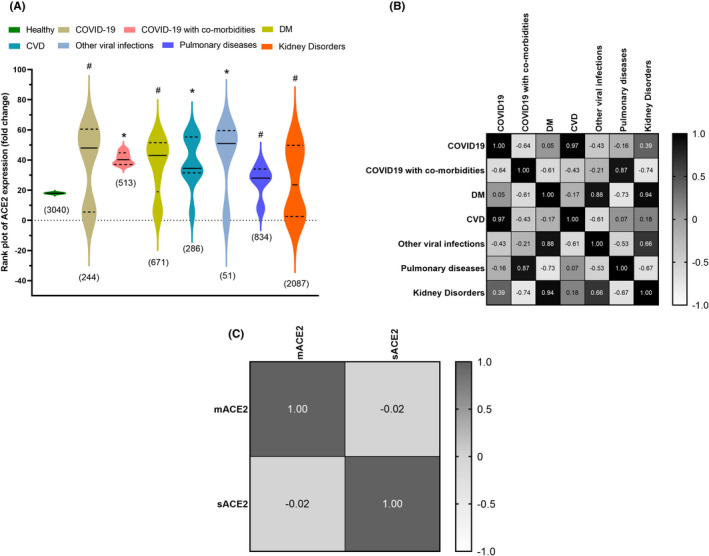

The fold change in total ACE2 expression significantly increased in patients with viral infections, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, pulmonary diseases, and SARS‐CoV2 infection, except for kidney disorders, as shown in Figure 4A. The total ACE2 expression in patients with CVD and viral infections showed statistically significant elevated levels compared to healthy subjects, and these results are in line with meta‐analysis data.

FIGURE 4.

The violin rank plot of angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression (fold change) showed an elevated levels in all diseases except kidney disorders. The numbers in parenthesis indicate the total subjects. The solid (−) and dashed (‐‐) lines indicate the median value and interquartile range, respectively. *p < .05 indicates statistical significance vs healthy subjects and # p > .05 statistically nonsignificant vs healthy subjects. (B, C) The heat map of ACE2 expression in various diseases and their correlation were analysed with the Spearman correlation coefficient method.

Spearman correlation of total ACE expression among different diseases showed a significant positive association. ACE2 expression in COVID‐19 and CVD showed a significant positive association with a correlation coefficient (r) of .97 (Figure 4B). Similarly, ACE2 expression in diabetes, kidney disorders and other viral infections showed a positive association with a correlation coefficient (r) of .94 and .88, respectively. COVID‐199 patients with co‐morbidities and patients with pulmonary diseases showed a positive association for ACE2 expression with a correlation coefficient (r) of .87, as demonstrated in Figure 4A,B. The soluble and membrane‐bound ACE2 were analysed for Spearman correlation and found to have an inverse association with a correlation coefficient (r) of −.02 as shown in Figure 4C.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. ACE2 levels and its significance

Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 is a crucial access point for SARS‐CoV2 in host cells, and the expression of ACE2 and their dynamic as soluble and membrane‐bound ACE2 are of utmost importance, and deliberation on it remains unknown to date. 45 , 46 The computational approach depicted that electrostatic features drives the binding affinity of SARS‐CoV2 towards ACE2. Several changes in the SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor binding domain residue increase the binding affinity of SARS‐CoV‐2 to ACE2. 47 Additionally, the ACE2‐binding ridge in the SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor binding domain has a more compact conformation. The binding of ACE2 to coronavirus includes a series of events that results into the fusion of viral and host cell membrane for entry. It further leads to the dissociation of S1 and S2 proteins of the virus, which prompts the transition of S2 from a metastable pre‐fusion to a more stable post‐fusion state required for membrane fusion. 3 , 48 , 49

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 virus identifies ACE2 as its receptor via receptor‐binding domain (RBD), which is ever‐shifting among standing‐up position for receptor binding and a lying‐down position for immune evasion. 50 Additionally, the spike also required activation by proteolysis at the S1/S2 boundary, so that S1 dissociates and S2 undergoes a dramatic structural change. The cell surface and lysosomal proteases, TMPRSS2 and cathepsin, are necessary for protease activity which will facilitate immediate spread in the host. Upon fusion with the host membrane with a virus, intact ACE2 or its transmembrane domain is internalized with the virus. Spike glycoprotein does not block the catalytical active site of ACE2, thus, the overall process of fusion is independent of the peptidase activity of ACE2. 3 Some other transmembrane proteases are also involved in the process of binding and membrane fusion are disintegrin and metallopeptidase domain 17 [ADAM17], transmembrane protease serine 2 [TMPRSS2], TNF‐converting enzyme. 6 The ADAM17 is a TNF convertase that facilitates the cleavage of ACE2 for ectodomain shedding, while TMPRSS2 cleaves ACE2 to facilitate viral uptake. 3

4.2. Tissue‐specific ACE2 expression

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 is accepted as an airborne transmitted respiratory virus. Therefore, the virus must initially infect the respiratory tract cells. In situ RNA analysis and single‐cell sequencing of the human respiratory tract revealed that ACE2 is highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells and has lesser expression in bronchial epithelial cells and alveolar type 2 (AT2) cells. In vitro studies were consistent with that finding showing upper respiratory tract cells were more permissive to SARS‐CoV‐2 infection than lower respiratory tract cells. 51 Recently, Zhao and colleagues 52 revealed with single cell RNA profiling study that, ACE2 is expressed only in .64% of pulmonary cells, and the majority of the expression is concentrated on AT2 cells (about 83%). Therefore, SARS‐CoV‐2 seems to efficiently utilize AT2 cells for reproduction and spread. The high AT2 expression of ACE2 may be the reason for severe alveolar injury following the initial infection.

Previous studies demonstrated, ACE2 is widely distributed in multiple other tissues, including the heart, vascular smooth muscle cells, kidney, gastrointestinal tract, testis, adipose tissue and brain tissue. ACE2 is expressed mainly in the epithelial cells of these organs. Xu and colleagues performed RNA‐Seq for 14 organs and showed that ACE2 is highly expressed in (from highest to lowest) the colon, gallbladder, heart muscle, kidney, epididymis, breast, ovary, lung, prostate, oesophagus, tongue, liver, pancreas and cerebellum. 53

The same study revealed high ACE2 expression in oral cavity epithelial cells, consistent with the initiation of infection at the upper respiratory tract. Hikmet and colleagues analysed the protein expression profiles in a variety of human tissues. ACE2 was mainly expressed in renal tubules, intestinal enterocytes, cardiomyocytes, vasculature gallbladder, male reproductive cells, ductal cells, placental trophoblasts and the eye. 54

4.3. Membrane‐bound and soluble forms of ACE2, and mechanism of shedding

As a transmembrane glycoprotein enzyme, ACE2 is composed of a short cytoplasmic domain, a transmembrane domain, a catalytic ectodomain and an amino‐terminal signal peptide. Similar to most other transmembrane proteins, ACE2 undergoes proteolytic cleavage from the cell surface to release its catalytic ectodomain part as a soluble form, a process known as ectodomain shedding. Shedding is a key post‐translational modifications mechanism for transmembrane proteins such as ACE2. Therefore, ACE2 can be found as membrane‐bound or as soluble/circulating within the body. 55 Because the catalytic site of ACE2 is located in the ectodomain site, the release of the catalytically active part of the enzyme following shedding can influence the enzymatic activities in the cellular microenvironment, but also can influence distal tissue once the soluble enzyme migrates to distal organs via systemic circulation. 56

To improve therapies, it is important to understand how ACE2 shedding, as well as membrane‐bound and soluble ACE2 levels, affect SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Li and colleagues were the first groups showing that the S1 domain of the SARS‐CoV S‐protein binds efficiently to ACE2 isolated from SARS‐CoV‐permissive Vero E6 cells. 57

When a major portion of the cytoplasmic domain of ACE2 was deleted, there was no effect on S‐driven infection, suggesting that the cytoplasmic domain is not critical for receptor function for infection. Another important finding was that a soluble form of ACE2 could successfully block the association of the S1 domain with the cells. Viral replication was inhibited when the cells were cultured in the presence of an anti‐ACE2 antibody. Hoffmann et al 58 showed that ACE2 expression levels in various cell lines directly correlated with the susceptibility to SARS‐CoV S‐driven infection. They also demonstrated that pre‐incubation of cell cultures with soluble ACE2 ectodomain inhibits SARS‐CoV S‐driven infection in a dose‐dependent manner, further confirming that soluble ACE2 can effectively block the binding of SARS‐CoV S‐protein to membrane‐bound ACE2. These findings directed interest to mechanisms for ACE2 shedding, which would increase soluble ACE2 levels and inhibit viral infection. Lambert and colleagues investigated the involvement of several ADAM family proteins, which largely mediate the shedding of membrane proteins. 58 , 59

In the present meta‐analysis, we observed an elevated level of ACE2 in patients with all diseases, albeit membrane‐bound ACE2 expression is high compared to soluble form ACE2. Further, subgroup analysis of two forms of ACE2 expression revealed an elevated membrane‐bound ACE2 in patients with diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, viral diseases, and SARS‐CoV2 infection with co‐morbidities, whereas relatively low expression of membrane‐bound ACE2 in patients with SARS‐CoV2 infection without co‐morbidities and kidney diseases. The multivariate analysis depicted a statistically significant increase in total ACE2 levels in patients with cardiovascular diseases, and viral infection.

Numerous studies showed the high expression of ACE2 in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), influenza infection and their susceptibility to SARS‐COV2 infection mediated severity. 60 , 61 Similarly, differential levels of expression correlated directly with the signs and symptoms, site of entry, and invasion for SARS‐CoV2 infection. For instance, Chen et al. showed elevated levels of ACE2 in the olfactory neuroepithelium, suggestive of loss of taste and smell. 62 The low expression of ACE2 in the nasal epithelium of children compared to adults or low expression of ACE2 in asthma patients compared to COPD protect them from SARS‐CoV2 infection has been demonstrated by several reports. 60 , 63

The patients with SARS‐CoV2 infection with or without comorbidity have high levels of soluble ACE2, suggesting shedding of ACE2, however, high expression of membrane‐bound ACE2 in comorbid patients with SARS‐CoV2 infection was observed. It could be a plausible underlying reason corroborating the findings of Li and colleagues' data depicting blocking viral entry with soluble ACE2. Therefore, COVID‐19 patients with co‐morbidity are prone to have an infection due to high membrane‐bound ACE2 despite having high levels of soluble ACE2. The investigation of the underlying mechanism for elevated levels of soluble ACE2 in response to SARS‐CoV2 infection is warranted. Next, the soluble form of ACE2 did not show any regulation in diabetic and kidney disease subjects. However, the membrane‐bound ACE2 levels were reduced in SARS‐CoV2 infected and kidney disease patients.

The differential expression of ACE2 and its dynamic in normal physiology and pathophysiology is crucial to decipher its role at the backdrop of SARS‐CoV2 infection.

4.4. Limitations of the study

The limitations of the present meta‐analysis include diverse methods employed for the estimation of the ACE2 levels in the selected studies. Moreover, ACE2 expressions are analysed at transcriptional and translational levels in the included studies, and samples taken for expression studies were also diverse in origin. Hence, for meta‐analysis and multivariate analysis, data were analysed, comparing ACE2 levels in a healthy population included in the respective study. In multivariate analysis, fold change was calculated with respect to healthy population ACE2 levels, and nonparametric analysis was performed.

5. CONCLUSION

Several reports suggested that the patients with co‐morbidity are prone to have SARS‐CoV‐2 infection than age match healthy subjects. The underlying reason could be associated with elevated ACE2 levels in these patients. The dynamic of soluble and membrane‐bound ACE2 did not investigate so far in detail. The measurement of soluble and membrane‐bound ACE2 could delineate a link between the severity and clinical outcome of the patients with co‐morbidity. Interestingly, in hospitalized patients, measuring ACE is the standard method. Our study encourages ACE2 measurements along with ACE in patients with COVID‐19 infection. Moreover, the ACE2 forms (soluble vs. membrane‐bound), their significance, regulation, the expression pattern in various tissue and corresponding diseases are still unexplored. Further investigation would warrant the strategic design of therapeutic targets for emerging multitargeted complex infectious diseases like COVID‐19.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Vandana S. Nikam contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Vandana S. Nikam, Dipanjali Kamthe, Swapnil Sarangakr, Manali Dalvi and Netra Gosavi. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Vandana S. Nikam and Dipanjali Kamthe, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

Figures S1–S4

Tables S1–S10

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are thankful to those who directly or indirectly help in preparing the manuscript.

Kamthe DD, Sarangkar SD, Dalvi MS, Gosavi NA, Nikam VS. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 level and its significance in COVID‐19 and other diseases patients. Eur J Clin Invest. 2023;53:e13891. doi: 10.1111/eci.13891

REFERENCES

- 1. Banu N, Surendra S, Riera L, Riera A. Since January 2020, Elsevier has created a COVID‐19 resource centre with free information in English and Mandarin on the novel coronavirus COVID‐19. The COVID‐19 resource centre is hosted on Elsevier Connect, the company's public news and information. 2020.

- 2. Warner FJ, Guy JL, Lambert DW, Hooper NM, Turner AJ. Angiotensin converting enzyme‐2 (ACE2) and its possible roles in hypertension, diabetes and cardiac function. Lett Pept Sci. 2003;10:377‐385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shang J, Wan Y, Luo C, et al. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS‐CoV‐2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(21):11727‐11734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2003138117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kruse RL. Therapeutic strategies in an outbreak scenario to treat the novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China. F1000Res. 2020;9:72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reich HN, Oudit GY, Penninger JM, Scholey JW, Herzenberg AM. Decreased glomerular and tubular expression of ACE2 in patients with type 2 diabetes and kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008;74(12):1610‐1616. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Verdecchia P, Cavallini C, Spanevello A, Angeli F. The pivotal link between ACE2 deficiency and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. Eur J Intern Med. 2020;76:14‐20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.04.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Batlle D, Soler MJ, Ye M. ACE2 and Diabetes: ACE of ACEs? Diabetes. 2010;59:2994‐2996. doi: 10.2337/db10-1205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gupta R, Hussain A, Misra A. Diabetes and COVID‐19: evidence, current status and unanswered research questions. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2020;74:864‐870. doi: 10.1038/s41430-020-0652-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. El‐Arif G, Khazaal S, Farhat A, et al. Angiotensin II type I receptor (AT1R): The gate towards COVID‐19‐associated diseases. Molecules. 2022;27(7):2048. doi: 10.3390/molecules27072048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Simera I, Moher D, Hoey J, Schulz KF, Altman DG. A catalogue of reporting guidelines for health research. Eur J Clin Invest. 2010;40(1):35‐53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02234.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation andelaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Osman IO, Melenotte C, Brouqui P, et al. Expression of ACE2, soluble ACE2, angiotensin I, angiotensin II and angiotensin‐(1‐7) is modulated in COVID‐19 patients. Front Immunol. 2021;12:625732. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.625732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. van Lier D, Kox M, Santos K, van der Hoeven H, Pillay J, Pickkers P. Increased blood angiotensin converting enzyme 2 activity in critically ill COVID‐19 patients. ERJ Open Res. 2021;7(1):00848‐2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00848-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Patel SK, Juno JA, Lee WS, et al. Plasma ACE2 activity is persistently elevated following SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: implications for COVID‐19 pathogenesis and consequences. Eur Respir J. 2021;57(5):10‐12. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03730-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kragstrup TW, Singh HS, Grundberg I, et al. Plasma ACE2 predicts outcome of COVID‐19 in hospitalized patients. PLoS One. 2021;16:1‐16. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saheb Sharif‐Askari N, Saheb Sharif‐Askari F, Alabed M, et al. Airways expression of SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor, ACE2, and TMPRSS2 is lower in children than adults and increases with smoking and COPD. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2020;18:1‐6. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.05.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yang CW, Lu LC, Chang CC, et al. Imbalanced plasma ace and ACE2 level in the uremic patients with cardiovascular diseases and its change during a single hemodialysis session. Ren Fail. 2017;39(1):719‐728. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2017.1398665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chen L, Li X, Chen M, Feng Y, Xiong C. The ACE2 expression in human heart indicates new potential mechanism of heart injury among patients infected with SARS‐CoV‐2. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116(6):1097‐1100. doi: 10.1093/CVR/CVAA078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goulter AB, Goddard MJ, Allen JC, Clark KL. ACE2 gene expression is up‐regulated in the human failing heart. BMC Med. 2004;2:1‐7. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-2-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu H, Gai S, Wang X, et al. Single‐cell analysis of sars‐cov‐2 receptor ace2 and spike protein priming expression of proteases in the human heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2020;116(10):1733‐1741. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvaa191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ramchand J, Patel SK, Srivastava PM, Farouque O, Burrell LM. Elevated plasma angiotensin converting enzyme 2 activity is an independent predictor of major adverse cardiac events in patients with obstructive coronary artery disease. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):1‐11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bao W, Zhang X, Jin Y, et al. Factors associated with the expression of ace2 in human lung tissue: Pathological evidence from patients with normal fev1 and fev1/fvc. J Inflamm Res. 2021;14:1677‐1687. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S300747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Walters TE, Kalman JM, Patel SK, Mearns M, Velkoska E, Burrell LM. Angiotensin converting enzyme 2 activity and human atrial fibrillation: Increased plasma angiotensin converting enzyme 2 activity is associated with atrial fibrillation and more advanced left atrial structural remodelling. Europace. 2017;19(8):1280‐1287. doi: 10.1093/europace/euw246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Purushothaman KR, Krishnan P, Purushothaman M, et al. Expression of angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 and its end product angiotensin 1‐7 is increased in diabetic atheroma: Implications for inflammation and neovascularization. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2013;22(1):42‐48. doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2012.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Couselo‐Seijas M, Almengló C, M Agra‐Bermejo R, et al. Higher ACE2 expression levels in epicardial cells than subcutaneous stromal cells from patients with cardiovascular disease: Diabetes and obesity as possible enhancer. Eur J Clin Invest. 2021;51(5):1‐10. doi: 10.1111/eci.13463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xiao F, Hiremath S, Knoll G, et al. Increased urinary angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 in renal transplant patients with diabetes. PLoS One. 2012;7(5):e37649. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Park SE, Kim WJ, Park SW, et al. High urinary ACE2 concentrations are associated with severity of glucose intolerance and microalbuminuria. Eur J Endocrinol. 2013;168(2):203‐210. doi: 10.1530/EJE-12-0782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Herman‐Edelstein M, Guetta T, Barnea A, et al. Expression of the SARS‐CoV‐2 receptorACE2 in human heart is associated with uncontrolled diabetes, obesity, and activation of the renin angiotensin system. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20(1):90. doi: 10.1186/s12933-021-01275-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Elemam NM, Hasswan H, Aljaibeji H, Sulaiman N. Circulating soluble ACE2 and upstream microrna expressions in serum of type 2 diabetes mellitus patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(10):5263. doi: 10.3390/ijms22105263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Peters MC, Sajuthi S, Deford P, et al. COVID‐19‐related genes in sputum cells in asthma: relationship to demographic features and corticosteroids. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(1):83‐90. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0821OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li G, He X, Zhang L, et al. Assessing ACE2 expression patterns in lung tissues in the pathogenesis of COVID‐19. J Autoimmun. 2020;112:102463. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2020.102463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Anguiano L, Riera M, Pascual J, et al. Circulating angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 activity in patients with chronic kidney disease without previous history of cardiovascular disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30(7):1176‐1185. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfv025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Trojanowicz B, Ulrich C, Kohler F, et al. Monocytic angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 relates to atherosclerosis in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32(2):287‐298. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfw206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Roberts MA, Velkoska E, Ierino FL, Burrell LM. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 activity in patients with chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(9):2287‐2294. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gft038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Guo J, Wei X, Li Q, et al. Single‐cell RNA analysis on ACE2 expression provides insights into SARS‐CoV‐2 potential entry into the bloodstream and heart injury. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235(12):9884‐9894. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Gu H, Xie Z, Li T, et al. Angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 inhibits lung injury induced by respiratory syncytial virus. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1‐10. doi: 10.1038/srep19840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Smith JC, Sausville EL, Girish V, et al. Cigarette smoke exposure and inflammatory signaling increase the expression of the SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor ACE2 in the respiratory tract. Dev Cell. 2020;53(5):514‐529. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.05.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Oudit GY, Kassiri Z, Jiang C, et al. SARS‐coronavirus modulation of myocardial ACE2 expression and inflammation in patients with SARS. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009;39(7):618‐625. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2009.02153.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Soldo J, Heni M, Königsrainer A, Häring HU, Birkenfeld AL, Peter A. Increased hepatic ACE2 expression in NAFL and diabetes‐a risk for COVID‐19 patients? Diabetes Care. 2020;43(10):e134‐e136. 10.2337/dc20-1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wijnant SRA, Jacobs M, Van Eeckhoutte HP, et al. Expression of ACE2, the SARS‐CoV‐2 receptor, in lung tissue of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2020;69(12):2691‐2699. doi: 10.2337/db20-0669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jacobs M, van Eeckhoutte HP, Wijnant SRA, et al. Increased expression of ACE2, the SARS‐CoV‐2 entry receptor, in alveolar and bronchial epithelium of smokers and COPD subjects. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(2):2002378. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02378-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. He L, Ding Y, Zhang Q, et al. Expression of elevated levels of pro‐inflammatory cytokines in SARS‐CoV‐infected ACE2+ cells in SARS patients: relation to the acute lung injury and pathogenesis of SARS. J Pathol. 2006;210(3):288‐297. doi: 10.1002/path.2067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Epelman S, Shrestha K, Troughton RW, et al. Soluble angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 in human heart failure: relation with myocardial function and clinical outcomes. J Card Fail. 2009;15(7):565‐571. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane collaboration; 2019:1‐694. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Batlle D, Monteil V, Garreta E, et al. Evidence in favor of the essentiality of human cell membrane‐bound ACE2 and against soluble ACE2 for SARS‐CoV‐2 infectivity. Cell. 2022;185(11):1837‐1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yeung ML, Teng JLL, Jia L, et al. Soluble ACE2‐mediated cell entry of SARS‐CoV‐2 via interaction with proteins related to the renin‐angiotensin system. Cell. 2021;184:2212‐2228. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.02.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Xie Y, Karki CB, Du D, et al. Spike proteins of SARS‐CoV and SARS‐CoV‐2 utilize different mechanisms to bind with human. Front Mol Biosci. 2020;7:591873. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.591873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Elrashdy F, Redwan EM. Why COVID‐19 transmission is more efficient and aggressive than viral transmission in previous coronavirus epidemics? Biomolecules. 2020;10:1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ni W, Yang X, Yang D, et al. Role of angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in COVID‐19. Crit Care. 2020;24:422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Lan J, Ge J, Yu J, et al. Structure of the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike receptor‐binding domain bound to the ACE2 receptor. Nature. 2020;581:215‐220. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2180-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Matheson BNJ, Lehner PJ. How does SARS‐CoV‐2 cause COVID‐19? Science. 2020;369(6503):510‐512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhao Y, Zhao Z, Wang Y, Zhou Y, Ma Y, Zuo W. Single‐cell RNA expression profiling of ACE2, the receptor of SARS‐CoV‐2. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(5):756‐759. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202001-0179LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Xu H, Zhong L, Deng J, et al. High expression of ACE2 receptor of 2019‐nCoV on the epithelial cells of oral mucosa. Int J Oral Sci. 2020;12(1):1‐5. doi: 10.1038/s41368-020-0074-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hikmet F, Méar L, Edvinsson Å, Micke P, Uhlén M, Lindskog C. The protein expression profile of ACE2 in human tissues. Mol Syst Biol. 2020;16(7):1‐16. doi: 10.15252/msb.20209610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yalcin HC, Sukumaran V, Al‐ruweidi MKAA. Do changes in ACE2 expression affect SARS‐CoV‐2 virulence and related complications: a closer look into membrane‐bound and soluble forms. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:6703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Iwata M, Greenberg BH. Ectodomain shedding of ACE and ACE2 as regulators of their protein functions. Curr Enzyme Inhibit. 2012;7(1):42‐55. doi: 10.2174/157340811795713756 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Li S, Wang Z, Yang X, Hu B, Huang Y, Fan S. Association between circulating angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 and cardiac remodeling in hypertensive patients. Peptides (NY). 2017;90:63‐68. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2017.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hoffmann M, Kleine‐Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271‐280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Haga S, Nagata N, Okamura T, et al. TACE antagonists blocking ACE2 shedding caused by the spike protein of SARS‐CoV are candidate antiviral compounds. Antiviral Res. 2010;85(3):551‐555. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wark PAB, Pathinayake PS, Eapen MS, Sohal SS. Asthma, COPD and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection (COVID‐19): potential mechanistic insights. Eur Respir J. 2021;58(2):3‐5. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00920-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Schweitzer KS, Crue T, Nall JM, et al. Influenza virus infection increases ACE2 expression and shedding in human small airway epithelial cells. Eur Respir J. 2021;58(1):1‐23. doi: 10.1183/13993003.03988-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chen M, Shen W, Rowan NR, et al. Elevated ACE2 expression in the olfactory neuroepithelium: Implications for anosmia and upper respiratory SARS‐CoV‐2 entry and replication. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(3):1‐9. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01948-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Bunyavanich S, Do A, Vicencio A. Nasal gene expression of angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 in children and adults. JAMA. 2020;323(23):2427‐2429. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1

Figures S1–S4

Tables S1–S10