Abstract

Background

The SARS‐COV‐2 (Covid‐19) pandemic has impacted the management of patients with hematologic disorders. In some entities, an increased risk for Covid‐19 infections was reported, whereas others including chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) had a lower mortality. We have analyzed the prevalence of Covid‐19 infections in patients with mastocytosis during the Covid‐19 pandemic in comparison to data from CML patients and the general Austrian population.

Materials and Methods

The prevalence of infections and PCR‐proven Covid‐19 infections was analyzed in 92 patients with mastocytosis. As controls, we used 113 patients with CML and the expected prevalence of Covid‐19 in the general Austrian population.

Results

In 25% of the patients with mastocytosis (23/92) signs and symptoms of infection, including fever (n = 11), dry cough (n = 10), sore throat (n = 12), pneumonia (n = 1), and dyspnea (n = 3) were recorded. Two (8.7%) of these symptomatic patients had a PCR‐proven Covid‐19 infection. Thus, the prevalence of Covid‐19 infections in mastocytosis was 2.2%. The number of comorbidities, subtype of mastocytosis, regular exercise, smoking habits, age, or duration of disease at the time of interview did not differ significantly between patients with and without Covid‐19 infections. In the CML cohort, 23.9% (27/113) of patients reported signs and symptoms of infection (fever, n = 8; dry cough, n = 17; sore throat, n = 11; dyspnea, n = 5). Six (22.2%) of the symptomatic patients had a PCR‐proven Covid‐19 infection. The prevalence of Covid‐19 in all CML patients was 5.3%. The observed number of Covid‐19 infections neither in mastocytosis nor in CML patients differed significantly from the expected number of Covid‐19 infections in the Austrian population.

Conclusions

Our data show no significant difference in the prevalence of Covid‐19 infections among patients with mastocytosis, CML, and the general Austrian population and thus, in mastocytosis, the risk of a Covid‐19 infection was not increased compared to the general population.

Keywords: mastocytosis, chronic myeloid leukemia, Covid‐19

Novelty Statements.

There are marked differences between hematological malignancies regarding the risk for infection with and outcomes from Covid‐19 infections. So far, no data on the prevalence of Covid‐19 infections in patients with mastocytosis have become available. In this work, we analyzed the prevalence of Covid‐19 in patients with mastocytosis in comparison with patients with CML and matched controls from the general Austrian population. Based on our data, there is no significant difference in the prevalence of patients with mastocytosis, CML, or matched controls from the general Austrian population. Thus, the universal management of mastocytosis patients does not differ from common recommendations to the healthy normal population.

1. INTRODUCTION

In December 2019, a novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐2 = Covid‐19) emerged in China. 1 , 2 Soon later, a pandemic spreading of Covid‐19 was found and till today continues to strain healthcare systems globally. 1 , 2 The clinical course of the disease ranges from asymptomatic course or mild upper respiratory tract illness to severe viral pneumonia leading to respiratory failure or death due to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or multi‐organ failure. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Most patients (>80%) present with mild or moderate symptoms and the majority of cases recover. 8 The most common reported clinical symptoms at presentation are fever and/or chills and dry cough. 9 , 10 , 11 Dyspnea, malaise, fatigue, sputum/secretion, anorexia, myalgia, sneezing, sore throat, and headache were other frequently reported symptoms. 9 , 10 , 11 A severe course of disease associated with a higher case fatality rate due to Covid‐19 more commonly occurs in elderly patients and patients with preexisting comorbidities. 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 Compared to patients aged <30 years, those aged 50–59 years, 60–69 years, 70–79 years, and ≥ 80 years had a 3‐, 5‐, 7‐, 9‐, and 12.5‐fold higher risk for to die from Covid‐19, respectively. 8

In cancer patients, continuous treatment, cytotoxic drugs, glucocorticoids, and other immunosuppressive drugs may play an aggravating role in the course of the disease. 12 , 13 , 14 Indeed, malignancies were found to be a risk factor for Covid‐19 infections. 8 On the other hand, based on meanwhile published overviews, there is growing evidence that the mortality rate during Covid‐19 infections is higher in patients with a history of cancer compared to the general population. 8 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 However, regarding chronic hematologic neoplasms including CML, the hematologic neoplasm usually is completely suppressed after a few weeks of therapy. In this regard, there is no evidence suggesting that chronic‐phase CML patients on a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) are at higher risk of having a more severe form of the viral infection or contracting Covid‐19 compared to the general population.

However, knowledge about the risk of Covid‐19 infections and Covid‐19 related deaths in patients with indolent (chronic) or advanced (aggressive/acute) hematologic neoplasms is limited. 21 , 22 Data from several nation‐wide data collections indicated a higher risk of mortality in patients with high‐risk hematologic neoplasms, including acute leukemia or highly aggressive lymphomas, with a fatality rate ranging between 13.8% and 34%. 23 , 24 , 25 In these neoplasms, the dilemma is that the underlying hematologic disease is by far a more dangerous enemy if intensive treatment is started during a bacterial or viral pneumonia. 26 Recently, serval papers were published on the mortality of Covid‐19 infections in patients with different hematologic neoplasms. Regarding AML, the PETHEMA group collected 108 patients with AML with active disease or in remission. 22 Overall, the mortality in case of a Covid‐19 infection in this cohort was 43.5%. Risk factors were active disease and treatment status. 22 In patients with myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) a higher mortality rate from Covid‐19 infections compared to the general population was observed. 27 In Philadelphia‐negative myeloproliferative neoplasms, a mortality rate of 34% was found. 25 In CML, some evidence suggests that TKIs including imatinib may influence the patient's response to a Covid‐19 infection. 25 Likewise, BCR‐ABL inhibitors may have anti‐viral action and there is ongoing research on the effect of TKIs in pulmonary vascular leak in patients with Covid‐19 pneumonia. Clonal mast cell activation disorders were thought to be associated with strong immunity to the virus 28 ; however, in contrast to CML, there is hardly any published data on mastocytosis regarding the course of Covid‐19.

Approximately, 1 year after the outbreak of the pandemic, vaccines against Covid‐19 became clinically available. While effective antibody concentrations and corresponding protection against severe cases are achieved in the healthy general population, immunocompromised patients represent a risk population in this regard. Indeed, the antibody production after vaccination is critically lower in hematologic patients, especially in those with lymphoid neoplasms. In a study shown by Rotterdam et al., 36% of patients tested negative for vaccine‐related antibodies. 29 However, there were specific concerns in patients with mastocytosis regarding severe adverse reactions. 30 Nevertheless, these have been shown to be rare and broad use of Covid‐19 vaccination in patients with mastocytosis can be recommended, considering known or suspected allergies against components of the vaccine and general and specific safety measures in patients with mastocytosis. 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34

In the present study, we have analyzed the prevalence of PCR‐proven Covid‐19 infections in patients with mastocytosis in the months prior to the availability of specific vaccination. Moreover, the percentage PCR‐proven Covid‐19 was compared between patients with mastocytosis, those with CML and age and sex matched controls of the general Austrian population.

2. PATIENTS AND METHODS

2.1. Patients

Patients were identified by reviewing the local registry of patients with mastocytosis at the Department of Internal Medicine I, Division of Hematology and Hemostaseology of the Medical University of Vienna. Included patients had to be aged ≥18 years on March 1, 2020, diagnosed before March 1, 2020, with mastocytosis as per WHO criteria. 34 Only mastocytosis patients with a follow‐up visit within the last 10 years were included. For comparison, patients with Ph + (BCR‐ABL1+) CML captured in a local registry and seen for a follow‐up visit within the last year were included. The data of the general population of Austria living in Vienna, Lower Austria, and Burgenland (control group) for correlations were obtained from the Federal Ministry for Social Affairs, Health, Care and Consumer Protection, Republic of Austria, and the Agency for Health and Food Safety (AGES) Institute Infectious Disease Epidemiology & Surveillance.

2.2. Procedures

The study was designed as a retrospective cohort study. Information on Covid‐19 infections (proven infection, duration, symptoms, and severity), signs of infection, comorbidities, smoking habits, medication, and regular exercise during the observation period were collected by structured telephone interviews carried out by a physician. The questionnaire that was used as a guideline for the structured interviews is shown in Table S1. This procedure was chosen to comply with the Covid‐19‐related challenges including the lock down by the regulatory authorities, reduction of follow‐up visits for routine check‐ups and long intervals between clinical visits of patients without mastocytosis‐related symptoms or problems. The interviews with the patients with mastocytosis were finalized until December 31, 2020 (i.e. wave one and two of Covid‐19), those with CML patients until May 31, 2021 (wave one, two and three of Covid‐19). The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Medical University of Vienna (EK number: 1356/2020).

2.3. Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the percentage of Covid‐19 infections, severity of Covid‐19 infections, Covid‐19‐like symptoms, comorbidities, or medication. To analyze the difference of age at the time of interview and the duration of the disease until the interview, the Mann–Whitney U test was applied for univariate analysis. Categorical variables were correlated using the Chi‐square test for univariate analysis. For multivariate analysis, a generalized linear model was applied. To calculate the expected prevalence of cases in the general Austria population, a control cohort matched for age, sex, and the area of residence (Vienna, Lower Austria and Burgenland) was used. The statistical evaluation was done by an observed‐expected analysis assuming Poisson counts for the number of cases. Exact Clopper‐Pearson 95% confidence intervals were computed. For the comparison of mastocytosis with CML, we have included only patients with systemic mastocytosis in the mastocytosis cohort since CM and MIS do not have bone marrow involvement and changes.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Patients included in the study

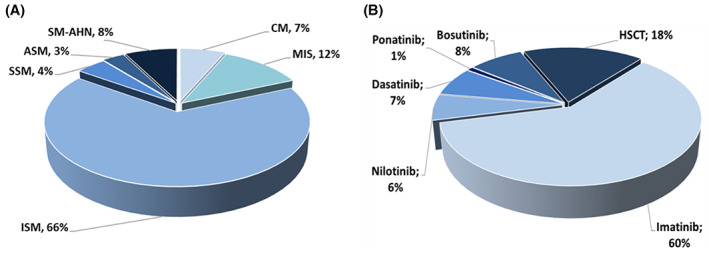

One‐hundred thirteen patients with mastocytosis met the inclusion criteria. Four of them refused to participate, and 17 patients could not be reached (Figure S1). Thus, 92 of them (females, n = 55; males, n = 37) could be included in our study. The median age at the time of interview was 55.5 years (range: 20–83 years; f:m‐ratio: 1:0.67) and the median serum tryptase was 26.15 ng/ml (range 2.6–822 ng/ml). Six (6.5%) patients had cutaneous mastocytosis (CM), 11 (12.0%) mastocytosis in the skin (MIS), 61 (66.3%) indolent systemic mastocytosis (ISM), 4 (4.3%) smoldering systemic mastocytosis (SSM), three (3.3%) aggressive systemic mastocytosis (ASM), and 7 (7.6%) systemic mastocytosis with an associated hematologic neoplasm (SM‐AHN) (Figure 1A). The median duration (range) of disease at the time of interview was 7.1 years (0.5–30 years).

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of mastocytosis patients with different mastocytosis variants (A) and types of directed therapy in our cohort of CML patients (B). (A) shows the relative number of patients of our study cohort in the different diagnostic subgroup of mastocytosis. (B) shows the relative number of patients in each treatment group of CML patients. ASM, aggressive SM; CM, cutaneous mastocytosis; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; ISM, indolent systemic mastocytosis; MIS, mastocytosis in the skin (The term MIS in this figure is used for in adult patients diagnosed with a skin involvement of mastocytosis in whom no bone marrow investigation was performed. Thus, systemic disease was not proven or ruled out); SM‐AHN, SM with associated hematologic neoplasm; SSM, smoldering SM

As control, 113 patients with CML (from 176 CML patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria) were analyzed (Figure S2). Their median age was 61 years (range 21–85 years; f:m ratio: 1:1.3) with a median duration of the disease at the time of the interview of 13.4 (range 2.1–40) years. Ninety‐three of these patients (82.3%) received targeted therapy with TKIs. TKIs used were imatinib (in 68 patients), dasatinib, (in eight patients), nilotinib (in seven patients), bosutinib (in nine patients), and ponatinib (in one patient) (Figure 1B). In 20 patients, a hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) had been performed. The median time since HSCT was 21 years (range: 1–28 years).

3.2. Subjective well‐being, comorbidities, and smoking habits were similar in patients with mastocytosis and those with CML

The majority (83.7%) of our patients with mastocytosis reported to “feel good,” 16.3% replied to feel “neither good nor too bad,” no patient replied to “feel bad.” Problems reported were primarily caused by concomitant disorders including other neoplasms or limb and joint pain (Table 1A). Similarly, most patients with CML 101/113 (89.4%) reported well‐being. To feel “neither good nor too bad” was stated by nine patients (8.0%) and three (2.6%) replied to feel bad. The most frequent reported problems in the CML‐cohort were fatigue, limb and joint pain, and cardiac problems (Table 1B).

TABLE 1.

Concomitant health problems reported from (A) mastocytosis patients, (B) CML patients

| Subtype of mastocytosis | Sex | Age at diagnosis | Age at interview | Duration of disease | Signs and symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A) | |||||

| ISM a | f | 31 | 52 | 20.2 | Dyspnea, chough (post Covid‐19) |

| ISM | m | 38 | 52 | 13.6 | Flew like symptoms |

| ISM | f | 63 | 74 | 11.0 | Night sweats |

| ISM | m | 50 | 61 | 10.9 | Conn syndrome |

| ISM | f | 46 | 51 | 5.7 | General situation |

| ISM a | f | 71 | 82 | 10.3 | Other neoplasm (breast cancer) |

| SSM | f | 48 | 70 | 22.6 | Limb and joint pain |

| SSM | f | 34 | 53 | 18.8 | Limb and joint pain |

| ASM | f | 75 | 76 | 0.8 | Nausea |

| ASM | f | 78 | 78 | 0.4 | Seizure |

| SM‐AHN | m | 56 | 60 | 3.5 | Other neoplasm (leukemia) |

| SM‐AHN | m | 70 | 73 | 2.4 | Cardiac problems |

| SM‐AHN | f | 79 | 82 | 2.2 | Parkinson's disease |

| SM‐AHN | m | 70 | 71 | 0.9 | Pain from a retropharyngeal abscess |

| SM‐AHN | f | 44 | 48 | 4.1 | Other neoplasm (CML) |

| Sex | Therapy | Age at diagnosis | Age at interview | Duration of disease | General conditionss | Signs and symptoms | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (B) | |||||||

| CML | m | Imatinib | 54 | 56 | 2.3 | intermediate | Limb and joint pain |

| CML | f | Imatinib | 64 | 66 | 2.48 | intermediate | Fatigue |

| CML | m | Imatinib | 70 | 73 | 2.1 | intermediate | Limb and joint pain, fatigue, insomnia |

| CML | f | Imatinib | 38 | 58 | 20.45 | intermediate | Sore throat |

| CML | m | HSCT | 23 | 52 | 28.62 | bad | Burnout |

| CML | m | Imatinib | 40 | 57 | 17.42 | bad | Limb and joint pain |

| CML | f | Imatinib | 60 | 77 | 16.48 | intermediate | Breast surgery |

| CML | f | HSCT | 40 | 57 | 17.25 | intermediate | Cardiac disease |

| CML | f | Bosutinib | 67 | 79 | 12.07 | intermediate | Cardiac disease |

| CML | f | Imatinib | 59 | 67 | 8.06 | intermediate | Pruritus, fatigue, limb, and joint pain |

| CML | f | Imatinib | 78 | 85 | 6.95 | intermediate | Impaired ambulatory ability |

| CML a | f | Dasatinib | 45 | 50 | 5.33 | bad | Covid‐19 |

Abbreviations: ASM, aggressive systemic mastocytosis; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; f, female; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; ISM, indolent systemic mastocytosis; m, male; SM‐AHN, systemic mastocytosis with an associated hematologic neoplasm; SSM, smoldering systemic mastocytosis.

Patient with reported Covid‐19 infection.

Comorbidities were reported in 32 patients with mastocytosis (34.8%). Their median age was 64.5 years (range: 27–83 years). The most frequent observed comorbidity seen in 24 patients (26.1%) was hypertension, followed by cardiac disorders (10 patients, 10.9%), diabetes (seven patients, 7.6%), other neoplasms (three patients, 3.3%; i.e., one case with acute myeloid leukemia, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma, and breast cancer each), renal disorders (three patients, 3.3%), and lung disorders (two patients, 2.2%) patients. One patient had liver disease. No comorbidities were reported in 60 patients (median age: 51 years; range 20–82; Figure S3a). The prevalence of cases with comorbidities was similar in the CML cohort. Sixty‐six patients (58.4%; median age 63.5, range 21–85 years) reported comorbidities including hypertension (35 patients, 31%), cardiac disease (27 patients, 23.9%), pulmonary disorders (17 patients, 15.0%), diabetes (15 patients, 13.3%), renal disease (eight patients, 7.1%), and liver disorders (three patients, 2.7%). No comorbidities were seen in 47 patients (median age 57 years, range 33–84 years) (Figure S3b).

The prevalence of smokers in the group of patients with mastocytosis was 28.6% (26/92) and thus higher than in the CML cohort (15.9%; 18/113 patients). Most patients with mastocytosis 67.4% (62/92) performed regular exercise during wave one and two of the Covid‐19 pandemic (Table S2). Similar data were observed in CML (Table S2).

3.3. Signs and symptoms of infection and Covid‐19 infections in patients with mastocytosis

Twenty‐three patients (25%) with mastocytosis reported signs and symptoms of infection during the observation period. The most frequently observed symptom was sore throat in 12 (13.0%) patients, followed by fever in 11 (12.0%), dry cough in 10 (10.9%), dyspnea in three (3.3%), and pneumonia in one (1.1%) case (Figure S4). In 13 patients (56.5%), only one sign or symptom of infection was found, in six patients, (26.1%) two, and in four patients (17.4%), three. The number of patients without signs and symptoms of infection and those that reported one, two, three, or four differed slightly but not significantly among the subgroups of mastocytosis (Table 2). None of our mastocytosis patients was diagnosed with influenza in the observed period.

TABLE 2.

Distribution of cases with or without signs and symptoms of infection among the different subgroups of mastocytosis

| Number of symptoms | n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All pts, n (%) | CM | MIS | ISM | SSM | ASM | SM‐AHN | |

| 0 | 69 (75%) | 5 (83.3%) | 9 (81.8%) | 45 (73.8%) | 2 (50.0%) | 3 (100%) | 5 (71.4%) |

| 1–3 | 23 (25%) | 1 (16.7%) | 2 (18.2%) | 16 (26.2%) | 2 (50.0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (28.6%) |

| Number of symptoms | n | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All pts, n (%) | CM | MIS | ISM | SSM | ASM | SM‐AHN | |

| 1 | 13 (56.5%) a | 0 | 1 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 2 | 6 (26.1%) a | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 3 | 4 (17.4%) a | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Abbreviations: ASM, aggressive systemic mastocytosis; ISM, indolent systemic mastocytosis; n, number of patients; pts, patients; SM‐AHN, systemic mastocytosis with an associated hematologic neoplasm; SSM, smoldering systemic mastocytosis.

Percentage relates to all patients that reported symptoms.

Two (8.7%) of the 23 symptomatic mastocytosis patients were proven to have Covid‐19 by PCR. Both were females and none of them had to be admitted to a hospital. As shown in Figure 2, both were aged above 50 years. Patient 1 was 52 years old and had an ISM with a serum tryptase level of 14.3 ng/ml. She had no known comorbidities and no co‐medication. She reported that the symptoms started in September 2020. After severe cephalea that was described by her as having been “horrible,” she developed asomnia on day 8. This was followed by fever and a further deterioration. The patient was unable to walk, even sitting, and reading in bed was not possible. The recovery was very slow, and she suffered from Post‐Covid‐19 syndrome with fatigue, dyspnea during exercise, and coughing during the nights for several months before improving. Patient 2 was 82 years old and had ISM with a serum tryptase level of 68.5 ng/ml. Following surgery for breast cancer, she received local radiation therapy. Her Covid‐19 infection was detected during a routine check‐up while being on rehabilitation several weeks after the end of radiation. When Covid‐19 was diagnosed, she received anti‐mediator therapy (histamine receptor HR1 & HR2 blockers and a leukotriene antagonist), bisphosphonates, vitamin D3, and calcium‐supplementation. She reported short episodes of sore throat and dry cough, only, and recovered quickly without Covid‐19‐related symptoms after 10 days.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of patients with and without Covid‐19 infection in the different age groups of patients with mastocytosis. In this figure, the number of patients with or without Covid‐19 infections per age group as included in our study is shown. Both patients with PCR‐proven Covid‐19 infection were aged >50 years

At the time of the interview, both patients were in the group reporting to feel “neither good nor too bad.” Patient 1 because of Post‐Covid‐19 syndrome and patient 2 because of fatigue after chemotherapy. There was no significant difference in age or duration of mastocytosis at the time of interview, number of comorbidities, regular exercise, or smoking in the patients with and without Covid‐19 infections.

3.4. Prevalence of Covid‐19 infections in patients with CML

In CML, 27/113 patients (23.9%) reported signs and symptoms of infection. The prevalence did not differ significantly from the data found in patients with mastocytosis. Regarding the symptoms, dry cough was found in 19 (16.8%) patients, sore throat in 12 (10.6%), fever in 10 (8.8%), and dyspnea in five (4.4%) (Figure S5). Six of these patients had a PCR‐proven infection with Covid‐19. All patients were symptomatic (Table 3) but none of them was admitted to a hospital. There were three female and three male patients, and all were younger than 65 years (Figure 3A). Their median age was 47 years (range 21–62 years). This was significantly younger compared to the patients without Covid‐19 infections (median age: 62 years; range: 27–85 years) (Figure 3B, p = .005). One of these patients received imatinib for 2 years and three patients received imatinib for 3 years. One patient received bosutinib for 3 years and the patient with dasatinib received this TKI for two and a half years. No cases of pneumonia or influenza were reported. The median duration of disease until the interview differed also significantly between patients with Covid‐19 infections (median duration: 3.5 years, range: 2.9–6.0 years) and those without Covid‐19 infection (median duration: 14.2 years, range: 2.1–40.3 years) (Figure 3C, p < .001). In line with this observation, the duration of treatment with TKIs was shorter in the group of patients with PCR‐proven Covid‐19 infection compared to those without PCR‐proven Covid‐19 infection. Similarly, the duration of treatment with dasatinib was 3 years in the patient with Covid‐19 infection compared to 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 10 years in those without Covid‐19 infection. As assessed by multivariate analysis together with comorbidities, regular exercise, smoking habits, and TKI, the differences in age and duration of disease at the time of interview remained significant (Table 4). Except one of the patients that had just recovered from Covid‐19, all reported to be well.

TABLE 3.

Correlation between signs and symptoms of infection and proven Covid‐19 infection among patients with CML

| Covid‐19 infection | Signs of infections, n | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| No; n (%) | 86 (80.4%) | 11 (10.3%) | 7 (6.5%) | 3 (2.8%) |

| Yes; n (%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (16.7%) | 4 (66.7%) | 1 (16.7%) |

Note: n, number of patients. p < .001 as assessed by Chi‐square test.

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of patients with and without Covid‐19 infection in patients with CML. The number of patients with or without Covid‐19 infection per age group as included in our study is shown in A. Patients with Covid‐19 infections were found to be younger at the time of interview (B) and had a shorter duration of disease (C). These differences were found to be significant as assessed by Mann–Whitney U test. The dots represent single patients; the bar in the middle, the median; and the whiskers, the interquartile range

TABLE 4.

Summary of the uni‐ and multivariate analysis of potential risk factors for Covid‐19 infections in patients with CML

| Variable | Univariate analysis p‐value | Multivariate analysis p‐value a |

|---|---|---|

| Comorbidities | .957 b | .940 |

| Regular exercise | .618 b | .843 |

| Smoking | .960 b | .582 |

| TKI | .694 b | .619 |

| Age | .007 c , d | .029 d |

| Duration of disease | .001 c , d | .006 d |

Abbreviation: TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

As assessed by a generalized linear model.

As assessed by Chi‐square test.

As assessed by Mann–Whitney U test.

The differences in age and duration of disease at the time of interviewwere significant in uni‐ and multivariate analysis.

The prevalence of Covid‐19 infections differed not significantly among patients treated with different TKIs (Table S3; p > .05). The incidence of Covid‐19 infections was similar when comparing CML patients according to the number of comorbidities, regular exercise, or smoking habits.

3.5. There is no significance difference in the prevalence of Covid‐19 infections among patients with systemic mastocytosis or CML and the general Austrian population

The number of Covid‐19 patients in the systemic mastocytosis cohort was slightly lower when compared to the expected number calculated based on data from the general population for wave one and two. However, the difference was not significant (Table 5). Similarly, the number of CML patients that reported a Covid‐19 infection was slightly lower than the expected numbers for the observation period (wave one to three) in the general population but again differed not significantly (Table 5). These calculations were matched for age, sex, and the area of residence (Vienna, Lower Austria, and Burgenland).

TABLE 5.

Comparison of patients with SM and CML with the general Austrian population

| Group | n | Observed Covid‐19 | Expected Covid‐19 | O/E | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM a | 75 | 2 | 2.67 | 0.75 | 0.09–2.71 |

| CML | 113 | 6 | 7.26 | 0.83 | 0.30–1.80 |

Abbreviations: 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; CML, chronic myeloid leukemia; n, number of patients; O/E, observed to expected ratio; SM, systemic mastocytosis.

For the comparison of mastocytosis with CML, we have included only patients with systemic mastocytosis in the mastocytosis cohort.

4. DISCUSSION

The Covid‐19 pandemic has substantially impacted the management of patients with hematologic disorders. 12 , 13 , 14 , 35 To date, limited data are available on the prevalence of Covid‐19 infections in mastocytosis. In our study, signs and symptoms of infection were found in 25% of the 92 patients with mastocytosis during the observation period and a PCR‐proven Covid‐19 infection was reported in 2.2%. Comorbidities, subtype of mastocytosis, regular exercises, smoking habits, age or duration of disease at the time of the interview did not differ among cases with or without Covid‐19 infection. Similar data were obtained in 113 patients with CML. Of these, 23.9% reported signs and symptoms of infection and 5.3% had a PCR‐proven Covid‐19 infection during the observation period. In CML patients positive for Covid‐19, the median age and the median duration of disease at the time of the interview were significantly shorter compared to patients without Covid‐19 infections. Other clinical findings like comorbidities, the type of TKI, regular exercise, or smoking habits did not differ significantly between CML patients with and without Covid‐19 infections, like in patients with mastocytosis. The prevalence of Covid‐19 infections in both mastocytosis and CML did not differ significantly from the general Austrian population during the respective observation period.

Published data report a higher risk for Covid‐19 infections in patients with certain hematologic neoplasms as compared to the general population or patients with solid tumors. 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 Such diseases were acute leukemia, advanced MDSs, or lymphomas. 22 , 27 , 39 , 40 , 41 In contrast, other hematologic malignancies including myeloproliferative neoplasms might be a protective factor. 42 , 43 In MDS, the majority of patients that recovered from Covid‐19 were lower risk cases according to the revised international prognostic scoring system (IPSS‐R) for MDS. 27 Those MDS patients that deceased were primarily in the higher risk categories of the IPSS‐R. 27 Thus, the risk of a severe course of a Covid‐19 infection seems to correlate with the aggressiveness of the hematologic neoplasm. This could explain why the prevalence and outcome of Covid‐19 in mastocytosis patients did not differ from the general population in this study. Most of our patients were diagnosed with ISM. This subcategory of mastocytosis is known to be an indolent disease with a normal life expectancy. 44 , 45 In line with our results, the Covid‐19‐associated mortality rates in 24 patients with mast cell disorders were similar to the general population as shown in a recently published study. 46

In our patients with CML, the prevalence of Covid‐19 infections did not differ significantly from the general Austrian population as well. Such a low prevalence of Covid‐19 infections among patients with CML was also reported in several other papers. 38 , 39 , 43 , 44 Of note, most of these CML patients were in chronic phase and/or had a stable course in response to TKIs. 43 , 47 , 48 Such a stable clinical course was also observed in the CML cohort analyzed in this study. Most of our patients had a good molecular response to TKIs, and some of them were in complete remission after HSCT. Thus, apart from a low proliferation rate and an indolent clinical course like in patients with mastocytosis, the response to therapy is an important prognostic factor for infections with Covid‐19. Indeed, a high prevalence of patients with advanced CML or patients without complete hematologic response were found in CML patients positive for Covid‐19. 43

Moreover, therapy with TKIs itself might influence the patient's response to a Covid‐19 infection. Several observational studies concluded that CML patients might have a milder course of the infection due to therapy with TKIs. 43 , 47 , 48 Of interest, disease related problems including the need for ICU admission or mechanical ventilation and the Covid‐19 associated mortality were lower in patients with CML under therapy with TKIs compared to matched controls without malignancies. 48 In this regard, an antiviral efficacy or an immunomodulatory effect of TKIs has been discussed. 49 , 50 , 51

Apart from the type of the hematologic neoplasm and the response to therapy, several other variables including non‐hematologic comorbidities, sex, and age have been proposed to be prognostic for the vulnerability to Covid‐19 infections. 8 , 52 , 53 , 54 Indeed, comorbidities were found to be important risk factors for Covid‐19 infection in the general population. 6 , 7 , 8 Little is known on the impact of comorbidities on the risk for Covid‐19 infections in patients with mastocytosis. In our study, one of the two patients with mastocytosis and Covid‐19 had a history of recent breast cancer. In the other patient, no comorbidities including neoplasms were reported. Data from a case‐series on mastocytosis patients with Covid‐19 infections revealed that only one of 24 patients presented with comorbidities. 46 However, this was the very patient that died from Covid‐19. 46 This may indicate that comorbidities increase the risk for Covid‐19 infections and the risk of severe Covid‐19 infections in patients with mastocytosis. To confirm the prognostic value of comorbidities in patients with mastocytosis, data from lager series are needed. Between our CML patients with or without Covid‐19 no significant difference in the prevalence of comorbidities were observed. However, based on a larger patient's cohort comorbidities were found to increase the risk to develop Covid‐19 in CML. 48 Thus, it is tempting to speculate that in both, mastocytosis and CML non‐hematologic comorbidities are risk factors to acquire an infection with Covid‐19.

Sex is another risk factor for a Covid‐19 infection in the general population. 55 In our mastocytosis cohort, PCR‐proven Covid‐19 infections were recorded in two female patients. In the report of Giannetti et al., most patients (13/24) with mastocytosis with Covid‐19 infection were female. This differs from the general population and patients with CML. In the general population significantly more males were found in the cohort of patients with Covid‐19. 55 In patients with CML and Covid‐19, the f:m ratio differs between the published cohorts. 43 , 56 Likewise, in our CML‐patients with Covid‐19 infections 50% were male, like in the report of Bonifacio et al. with 56%. 43 In other studies, the percentage of male CML patients with proven Covid‐19 infection was higher (up to 90%). 43 , 56 Despite these differences among the studies, overall, the f:m ratio reported in CML is closer to the f:m ration in the general population compared to the data reported from the mastocytosis cohorts. Regarding these differences between mastocytosis patients and the general population or CML patients it must be considered that in line with literature, more females were found in our mastocytosis cohort. 57 This female predominance in the study cohort might have contributed to the differences in the f:m ration in comparison to the general population and CML patients.

The risk for Covid‐19 infections increased with age. 8 , 52 , 53 , 54 In line with this observation, the two patients with mastocytosis and a Covid‐19 infection reported in this study were 52 and 82 years of age. Similarly, the majority of mastocytosis patients with Covid‐19 infections reported in the study of Giannetti et al. were aged above 50 years. 46 This data are in line with data from the general population. In contrast, our CML patients with Covid‐19 infections were significantly younger compared to those without Covid‐19. However, Covid‐19 positive CML patients were also more frequently active workers as reported by Bonifacio et al. 43 In this regard, one could speculate, that everyday life circumstances could have contributed to this discrepancy to the general population. To avoid an infection with Covid‐19, elderly retired patients with CML had a better chance to remain in isolation and to avoid contact with other people. In contrast, younger active working patients had to have social contact of some sort. This most probably increased their risk of a Covid‐19 infection.

Together, our data demonstrate that the risk of a Covid‐19 infection in patients with mastocytosis or CML does not differ comparing to the general Austrian population. The characteristics of the patients with mastocytosis and Covid‐19 infections are similar to those of the general population. In CML the prognostic value of sex and age seem to be less pronounced in comparison to the general population.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

IG, PV, and WRS contributed to the study design, data collection and analysis, and drafting of the manuscript. MK performed statistical analyses. SH, GG, MS, and EH contributed to data collection. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of the document.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

IG, SH, MK, GG, MS, EH, PV, and WRS do not have any competing financial interests in relation to the work described.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 Supplementary Information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported “The Medical‐Scientific Fund of the Mayor of Vienna” MA 40‐GMWF‐485930‐2020; Project # COVID057.

Graf I, Herndlhofer S, Kundi M, et al. Incidence of symptomatic Covid‐19 infections in patients with mastocytosis and chronic myeloid leukemia: A comparison with the general Austrian population. Eur J Haematol. 2023;110(1):67‐76. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13875

Funding information Medical‐Scientific Fund of the Mayor of Vienna MA 40‐GMWF‐485930‐2020, Grant/Award Number: COVID057

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Phelan AL, Katz R, Gostin LO. The novel coronavirus originating in Wuhan, China: challenges for global health governance. JAMA. 2020;323(8):709‐710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323:1061‐1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054‐1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinica characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507‐513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lescure FX, Bouadma L, Nguyen D, et al. Clinical and virological data of the first cases of COVID‐19 in Europe: a case series. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:697‐706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zhang Y, Luo W, Li Q, et al. Risk factors for death among the first 80 543 COVID‐19 cases in China: relationships between age, underlying disease, case severity, and region. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;74:630‐638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Karthika C, Swathy Krishna R, Rahman MH, Akter R, Kaushik D. COVID‐19, the firestone in 21st century: a review on coronavirus disease and its clinical perspectives. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021;28:64951‐64966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Korell F, Giannitsis E, Merle U, Kihm LP. Analysis of symptoms of COVID‐19 positive patients and potential effects on initial assessment. Open Access Emerg Med. 2020;12:451‐457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. da Rosa MR, Francelino Silva Junior LC, Santos Santana FM, et al. Clinical manifestations of COVID‐19 in the general population: systematic review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2021;133(7–8):377‐382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liang W, Guan W, Chen R, et al. Cancer patients in SARSCoV‐2 infection: a nationwide analysis in China. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335‐337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. D'Antiga L. Coronaviruses and immunosuppressed patients: the facts during thethird epidemic. Liver Transpl. 2020;26:832‐834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gavillet M, Carr Klappert J, Spertini O, Blum S. Acute leukemia in the time of COVID‐19. Leuk Res. 2020;92:106353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tagliamento M, Agostinetto E, Bruzzone M, et al. Mortality in adult patients with solid or hematological malignancies and SARS‐CoV‐2 infection with a specific focus on lung and breast cancers: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2021;163:103365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lièvre A, Turpin A, Ray‐Coquard I, et al. GCO‐002 CACOVID‐19 collaborators/investigators. Risk factors for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) severity and mortality among solid cancer patients and impact of the disease on anticancer treatment: a French nationwide cohort study (GCO‐002 CACOVID‐19). Eur J Cancer. 2020;141:62‐81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Docherty AB, Harrison EM, Green CA, et al. Features of 20 133 UK patients in hospital with covid‐19 using the ISARIC WHO clinical characterisation protocol: prospective observational cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369:m1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pinato DJ, Zambelli A, Aguilar‐Company J, et al. Clinical portrait of the SARS‐CoV‐2 epidemic in European cancer patients. Cancer Discov. 2020;10(10):1465‐1474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee AJX, Purshouse K. COVID‐19 and cancer registries: learning from the first peak of the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. Br J Cancer. 2021;124(11):1777‐1784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kuderer NM, Choueiri TK, Shah DP, et al. COVID‐19 and cancer consortium. Clinical impact of COVID‐19 on patients with cancer (CCC19): a cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10241):1907‐1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Singh S, Singh J, Paul D, Jain K. Treatment of acute leukemia during COVID‐19: focused review of evidence. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2021;21(5):289‐294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.T, Megías‐Vericat JE, Martínez P, López Lorenzo JL, Cornago Navascués J, Rodriguez Macias G, Cano I, Arnan Sangerman M et al. Characteristics, clinical outcomes, and risk factors of SARS‐COV‐2 infection in adult acute myeloid leukemia patients: experience of the PETHEMA group Palanques‐pastor P. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;22:1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang Q, Berger NA, Xu R. When hematologic malignancies meet COVID‐19 in the United States: infections, death and disparities. Blood Rev. 2020;47:100775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yigenoglu TN, Ata N, Altuntas F, et al. The outcome of COVID‐19 in patients with hematological malignancy. J Med Virol. 2021;93:1099‐1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Vijenthira A, Gong IY, Fox TA, et al. Outcomes of patients with hematologic malignancies and COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of 3377 patients. Blood. 2020;136:2881‐2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Valent P, Akin C, Bonadonna P, et al. Risk and management of patients with mastocytosis and MCAS in the SARS‐CoV‐2 (COVID‐19) pandemic: expert opinions. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;146(2):300‐306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mossuto S, Attardi E, Alesiani F, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 in myelodysplastic syndromes: a snapshot from early Italian experience. Hema. 2020;4(5):e483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rossignol, J. , Ouedrani, A. , Livideanu, C. B. , et al. Absence of severe COVID‐19 In patients with clonal mast cells activation disorders: effective anti‐SARS‐Cov‐2 immune response. A prospective and comprehensive study In France during one year. 2021. bioRxiv.2021.09.01.

- 29. Rotterdam, J. , Thiaucourt, M. , Schwaab, J. , et al. Antibody response to vaccination with BNT162b2, mRNA‐1273, and ChADOx1 in patients with myeloid and lymphoid neoplasms, Oral and Poster Abstracts, ASH Meeting 2021.

- 30. Bonadonna P, Brockow K, Niedoszytko M, et al. COVID‐19 vaccination in Mastocytosis: recommendations of the European competence network on Mastocytosis (ECNM) and American initiative in mast cell diseases (AIM). J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(6):2139‐2144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rama TA, Miranda J, Silva D, et al. COVID‐19 vaccination is safe among mast cell disorder patients, under adequate premedication. Vaccines. 2022;10(5):718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Tuncay G, Bostan OC, Damadoglu E, et al. SARS‐CoV‐2 vaccines are well tolerated in patients with mastocytosis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;128(6):733‐734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lazarinis N, Bossios A, Gülen T. COVID‐19 vaccination in the setting of mastocytosis‐Pfizer‐BioNTech mRNA vaccine is safe and well tolerated. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10(5):1377‐1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Horny HP, Akin C, Arber DA, et al., eds. World Health Organization (WHO) classification of Tumours. Pathology & Genetics. Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. IARC Press; 2016:62‐69. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Levy I, Sharf G, Norman S, Tadmor T. The impact of COVID‐19 on patients with hematological malignancies: the mixed‐method analysis of an Israeli national survey. Support Care Cancer. 2021;14:1‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fillmore NR, La J, Szalat RE, et al. Prevalence and outcome of COVID‐19 infection in cancer patients: a National Veterans Affairs Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113(6):691‐698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang Q, Berger NA, Xu R. Analyses of risk, racial disparity, and outcomes among US patients with cancer and COVID‐19 infection. JAMA Oncol. 2021;7(2):220‐227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Başcı S, Ata N, Altuntaş F, et al. Patients with hematologic cancers are more vulnerable to COVID‐19 compared to patients with solid cancers. Intern Emerg Med. 2021;17:135‐139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Passamonti F, Cattaneo C, Arcaini L, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with COVID‐19 severity in patients with haematological malignancies in Italy: a retrospective, multicentre, cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(10):e737‐e745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vijenthira A, Gong IY, Fox TA, et al. Outcomes of patients with hematologic malignancies and COVID‐19: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of 3377 patients. Blood. 2020;136(25):2881‐2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Roel E, Pistillo A, Recalde M, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of over 300,000 patients with COVID‐19 and history of cancer in the United States and Spain. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30(10):1884‐1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Levy I, Lavi A, Zimran E, et al. COVID‐19 among patients with hematological malignancies: a national Israeli retrospective analysis with special emphasis on treatment and outcome. Leuk Lymphoma. 2021;18:1‐10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bonifacio M, Tiribelli M, Miggiano MC, et al. The serological prevalence of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia is similar to that in the general population. Cancer Med. 2021;10(18):6310‐6316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sperr WR, Kundi M, Alvarez‐Twose I, et al. International prognostic scoring system for mastocytosis (IPSM): a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Haematol. 2019;6(12):e638‐e649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lim KH, Tefferi A, Lasho TL, et al. Systemic mastocytosis in 342 consecutive adults: survival studies and prognostic factors. Blood. 2009;113(23):5727‐5736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Giannetti MP, Weller E, Alvarez‐Twose I, et al. COVID‐19 infection in patients with mast cell disorders including mastocytosis does not impact mast cell activation symptoms. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(5):2083‐2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Başcı S, Ata N, Altuntaş F, et al. Outcome of COVID‐19 in patients with chronic myeloid leukemia receiving tyrosine kinase inhibitors. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2020;26(7):1676‐1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Breccia M, Abruzzese E, Bocchia M, et al. Chronic myeloid leukemia management at the time of the COVID‐19 pandemic in Italy. A Campus CML Survey Leukemia. 2020;34(8):2260‐2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Galimberti S, Petrini M, Baratè C, et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors play an antiviral action in patients affected by chronic myeloid leukemia: a possible model supporting their use in the fight against SARS‐CoV‐2. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sisk JM, Frieman MB, Machamer CE. Coronavirus S protein‐induced fusion is blocked prior to hemifusion by ABL kinase inhibitors. J Gen Virol. 2018;99(5):619‐630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Coleman CM, Sisk JM, Mingo RM, Nelson EA, White JM, Frieman MB. Abelson kinase inhibitors are potent inhibitors of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus fusion. J Virol. 2016;90(19):8924‐8933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kaeuffer C, Le Hyaric C, Fabacher T, et al. Clinical characteristics and risk factors associated with severe COVID‐19: prospective analysis of 1,045 hospitalised cases in north‐eastern France, march 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(48):2000895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Orlando V, Rea F, Savaré L, et al. Development and validation of a clinical risk score to predict the risk of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection from administrative data: a population‐based cohort study from Italy. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0237202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Gude‐Sampedro F, Fernández‐Merino C, Ferreiro L, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic model based on comorbidities to predict COVID‐19 severity: a population‐based study. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50(1):64‐74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zheng Z, Peng F, Xu B, et al. Risk factors of critical & mortal COVID‐19 cases: a systematic literature review and meta‐analysis. J Infect. 2020;81(2):e16‐e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Li W, Wang D, Guo J, et al. COVID‐19 in persons with chronic myeloid leukaemia. Leukemia. 2020;34(7):1799‐1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kluin‐Nelemans HC, Jawhar M, Reiter A, et al. Cytogenetic and molecular aberrations and worse outcome for male patients in systemic mastocytosis. Theranostics. 2021;11(1):292‐303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Supplementary Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.