Abstract

Aims and Objectives

This review aims to synthesize the available evidence of what patients experience when infected with COVID‐19, both in hospital and post‐discharge settings.

Design

This review was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology for qualitative systematic reviews and evidence synthesis. Reporting of results was presented according to the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) checklist.

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) continues to be a public health crisis worldwide. Many patients diagnosed with COVID‐19 have varied levels of persisting mental disorders. Previous studies have reported the degree, prevalence and outcome of psychological problems. Minimal research explored the experience of patients with long COVID. The real‐life experience of patients with COVID‐19 from diagnosis to post‐discharge can deepen the understanding of nurses, physicians and policymakers.

Methods

All studies describing the experience of patients were included. Two authors independently appraised the methodological quality of the included studies using the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research 2020.

Results

This systematic review aggregated patients’ experience of being diagnosed with COVID‐19 in both hospitalized and post‐discharge settings. Finally, 17 studies met inclusion criteria and quality appraisal guidelines. The selected studies in the meta‐synthesis resulted in 12 categories, and further were concluded as five synthesized findings: physical symptoms caused by the virus, positive and negative emotional responses to the virus, positive coping strategies as facilitators of epidemic prevention and control, negative coping strategies as obstacles of epidemic prevention and control, and unmet needs for medical resource.

Conclusions

The psychological burden of patients diagnosed with COVID‐19 is heavy and persistent. Social support is essential in the control and prevention of the epidemic. Nurses and other staff should pay more attention to the mental health of the infected patients both in and after hospitalization.

Relevance to clinical practice

Nurses should care about the persistent mental trauma of COVID‐19 survivors and provide appropriate psychological interventions to mitigate the negative psychological consequences of them. Besides, nurses, as healthcare professionals who may have the most touch with patients, should evaluate the level of social support and deploy it for them. It is also needed for nurses to listen to patient's needs and treat them with carefulness and adequate patience in order to decrease the unmet needs of patients.

Keywords: COVID‐19, experience, mental health, qualitative research, systematic review

What is already known.

COVID‐19, as a disease with high infectivity, is still associated with much uncertainty.

Patients infected with COVID‐19 may have different degrees of anxiety and depression.

COVID‐19 will potentially cause persistent psychological problems.

Some qualitative studies have explored the experience of patients infected with COVID‐19. Although the experience of persistent mental disorders was mentioned, no systematic review has been published.

What this paper adds.

COVID‐19 may have some continued negative psychological impacts (such as stigma).

Insufficient social support is an important obstacle to the prevention and control of the epidemic.

Patients have many unmet needs following medical treatment.

What does this paper contribute to the wider global clinical community?

Patients diagnosed with COVID‐19 may have relatively significant and persistent psychological burden.

At any time during the diagnosis, treatment and recovery, the social support level of COVID‐19 patients should be evaluated and deployed when it is needed.

Nurses should care about the mental health of COVID‐19 patients and survivors and consider providing appropriate interventions or supporting resources to mitigate their psychological burden.

1. INTRODUCTION

In December 2019, a highly infectious severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by a novel coronavirus (SARS‐CoV‐2) hit Wuhan, China, and rapidly spreaded to the world, leading to a public health crisis worldwide. Due to the high infectivity and pathogenicity of the virus, more than 230,000,000 confirmed cases have occurred worldwide due to COVID‐19 (World Health Organisation, 2021).

The process of treatment, being kept in quarantine and complex body symptoms will bring heavy mental burdens for patients (Brooks et al., 2020; Henssler et al., 2021; Naidu et al., 2021). Due to long‐term social isolation (Gupta & Dhamija, 2020; Wu et al., 2021), the uncertainty of the prognosis (Durodié, 2020; Rutter et al., 2020) and feelings of stigma and prejudice all the time (Bagcchi, 2020; Baldassarre et al., 2020), etc, many psychological problems have emerged, continuing beyond the epidemic itself. Several studies have found that the prevalence of depression, anxiety and post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was high, being 45%, 47% (Deng et al., 2021) and 32.2% (Janiri et al., 2021), respectively, compared with the general population in the era of COVID‐19 (Cénat et al., 2021; Hyland et al., 2020). Mental health is crucial to patients' well‐being. Patients with a higher level of depression tend to have poorer outcomes, such as longer lengths of stay and higher hospital readmission rates. Anxiety is associated with sleep disturbances and suicidal behaviour (Sher, 2020). PTSD was proved to connect with multisystem diseases such as cardiovascular disease, auto‐immune disease, cancer‐related disease, and metabolic disease if in a persistent state (Arieh et al., 2017).

Some patients are experiencing symptoms and complications beyond the phase of acute infection. This is called long COVID. The consequences of this emerging health problem are becoming an increasingly significant problem (Venkatesan, 2021). Long COVID can cause symptoms such as fatigue, dyspnoea, muscle pain, cognitive impairment, and sleep disturbances (Crook et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2021). Moreover, many studies have shown that long COVID can affect survivors emotionally. It can decrease the possibility of returning to work (Chopra et al., 2021), increase stress disorders (Crook et al., 2021), lead to the loss of social connections (Torales et al., 2020), and decrease the quality of life (Laurie et al., 2020). Venkatesan (2021) called for more studies enriching the understanding of long‐COVID in order to update guidance, which will be vital to provide evidence‐based care for these patients. Although we found that, in some quantitative studies of patients diagnosed with COVID‐19, the symptoms related to long COVID are reported, the real‐life experience of long COVID is rarely explored using qualitative methods.

Given the severity of the situation, physicians, nurses, psychotherapists, and researchers should attach adequate significance to the mental health of the patients. Quantitative researches on psychological problems of the COVID‐19 epidemic and long COVID have reported the prevalence, outcome and therapy within a biomedical paradigm. However, the meaning of COVID‐19 to an individual is rarely explored. Patients' real‐life experience can help nurses deepen their understanding and ascertain their needs both in physical and psychological aspects. Several studies have explored the experience of patients diagnosed with COVID‐19 using qualitative methods. We conducted a preliminary search of PubMed and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and the search results did not reveal any systematic review and meta‐synthesis of qualitative studies.

2. AIMS

This systematic review was conducted to synthesise and present current evidence from patients diagnosed with COVID‐19. This review will inform nurses and other staff of the subtle changes for patients and inspire responses of the long COVID epidemic.

3. METHODS

This systematic review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (registering number: CRD 42021243402). The Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) checklist (Appendix S1) was used to report the process and results of synthesis, and enhance transparency (Tong et al., 2012). The process of searching for studies was tracked using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) flowchart.

3.1. Search strategy

A systematic search strategy designed by a medical librarian was devised to identify studies reporting on the relevant experience of patients diagnosed with COVID‐19. An electronic search was conducted in 3 Chinese databases (China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), WanFang Data and VIP database) and 4 English databases (CINAHL, PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane Library) from their published up to 18 April 2021.

The query used both subject headings and keywords for each concept. A separate strategy was developed and optimised for each database. Searching terms we used in English databases were as follows: “patient”, “client”, “covid‐19 pandemic*”, “pandemic outbreak”, “disease outbreaks”, “coronavirus”, “epidemic*”, “2019 novel coronavirus disease”, “ncov 2019 disease”, “attitude”, “experience*”, “undergo*”, “view*”, “perception*”, “perspective*”, “feeling”, “thought”, “opinion”, “belie*”, “knowledge”.

Conference proceedings, editorials, commentaries, abstracts only, newsletters, addresses and research protocols were excluded manually. Reference lists of all selected articles were independently screened to identify additional studies left out in the initial search. Searching strategies in each database can be found in Appendix S2.

3.2. Eligibility criteria

The Eligible studies should be in agreement with the following criteria in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Literature inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. Published primary research report | 1. Poor methodological quality (≥5 items are ranked as ‘Unclear’ or ‘No’ using JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Qualitative Research) |

| 2. Participants who were the patients diagnosed with COVID‐19, both in settings of hospitalisation or discharge | 2. Focused on experience regarding an intervention or being a part of the evaluation of the intervention |

| 3. Participants who include doctors, nurses, family members, the finding of patients diagnosed with COVID‐19 can be extracted | 3. Papers published on conference, book, newspaper or other media |

| 4. Focused on patients' s experience, perspectives after being infected with COVID‐19 | 4. Paper only with title and abstract |

| 5. Used an appropriate qualitative method (e.g. phenomenology, grounded theory, ethnography, narrative inquiry, interviews, observations) | |

| 6. Used a mixed method, the qualitative part of which can be extracted | |

| 7. Papers published on journal | |

| 8. English or Chinese as its initial language |

3.3. Selection of studies

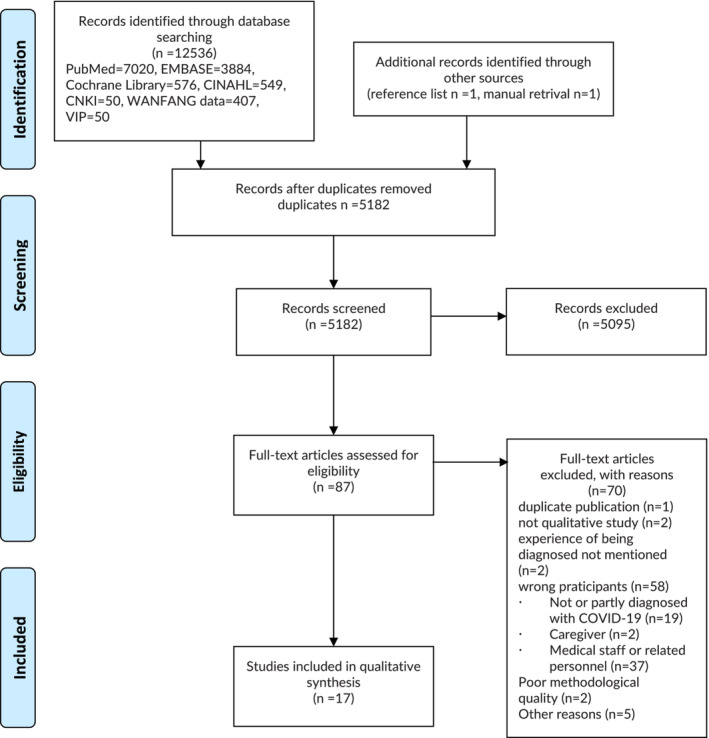

Study selection was performed by applying the eligibility criteria in stages following established guidelines for systematic reviews (Lefebvre et al., 2019). Results of database searches were imported into the reference management software program Endnote X9.3.3. After the removal of duplicates, two reviewers (XT and QM) independently assessed titles, abstracts and full‐text articles to identify the studies that best fulfilled the selection criteria. Any discrepancies were discussed to reach a consensus, with unresolved cases taken to a third reviewer (CJ) to make a final decision. All references to the included articles were searched for additional potentially relevant studies (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The flow diagram of study selection

3.4. Appraisal of methodological quality

Two researchers (XT and QM) independently evaluated the methodological rigour of the included literature following the Checklist for Qualitative Research (Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews) (Lockwood et al., 2015). This checklist includes 10 items, and each item is evaluated with ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unclear’. When the evaluation results conflicted, the third researcher (CJ) decided. A study was included if the item of it achieved a minimum of 60% ‘yes’ to guarantee the study showed acceptable quality. Studies were considered to possess acceptable quality if 60% of items were answered: ‘yes’, to possess good quality if 70%–90% of items were answered ‘yes’, and to have high quality if 100% of items were answered ‘yes’ (Talley et al., 2021).

3.5. Data extraction and synthesis

The JBI meta‐aggregation approach was used to extract and synthesise the data (Lockwood et al., 2015). This approach accurately and reliably presented the findings by the original authors instead of re‐interpreting the studies. Of all the methodologies available for qualitative study synthesis, meta‐aggregation is the most transparent and widely accepted for the construction of high‐quality systematic reviews (Lockwood et al., 2015).

Using this method, the general details of studies were extracted first and included citation details, the author, year, country, the characteristic of the participants, aims, study design and methods of data collection, and methods of data analysis. In the second phase, study findings were extracted, which was a verbatim extract of the author's analytical interpretation of the data followed by an illustration. Then, the plausibility of these findings was rated by two researchers of our team independently. The finding was rated as ‘unequivocal’ if the congruence of the finding and the illustration accompanied was beyond a reasonable doubt, as ‘credible’ if lacking a clear association between them and as ‘unsupported’ if the findings were not supported by the data (Talley et al., 2021).

The process of aggregation involved the synthesis of findings by categorising them through their similarity in meaning. Then, we subjected these categories to further synthesis to generate more comprehensive findings called synthesised findings. Only unequivocal and credible findings were included. Not supported findings did not be presented in the synthesis or the results (Lockwood et al., 2015).

4. RESULTS

4.1. Searching results

The search generated 12,536 papers. We also identified two additional records through reference list (n = 1) and manual retrieval (n = 1). After the removal of duplicates, 5182 papers were screened by reading the title and abstract, and of these, 87 full‐text papers were assessed for eligibility. After the exclusion of 70 papers (reasons were given in Figure 1), a total of 17 papers were included in the final qualitative synthesis.

4.2. Quality appraisal and study characteristics

Study characteristics for the included studies were presented in Table 2. Studies were undertaken in China (n = 11), the UK (n = 2), the United States (n = 1), Denmark (n = 1), Nigeria (n = 1) and Australia (n = 1). The sample size of the participants ranged from 8 to 114. Study designs included phenomenology (n = 11), qualitative descriptive approach (n = 2), qualitative study without specific (n = 3), and mix‐method study (n = 1). Data collection methods included face‐to‐face interviews (n = 6), web‐based or telephone‐based surveys (n = 9), and using both of them (n = 2). Nine kinds of methods of data analysis were mentioned: Giorgi's analysis approach (n = 1), thematic analysis (n = 2), Colaizzi's phenomenological method (n = 7), based on a theoretic framework (n = 1), the van Kaam's method (n = 1), Diekelmann, Allen and Tanner's seven‐step method (n = 1), using the concepts of grounded theory (n = 1), and constant comparative method (n = 1). All 17 eligible studies had acceptable to high quality. One study had acceptable quality; one study had high quality; and the other 15 studies had good quality. The results of the appraisal of the methodological quality of the research were presented in Table 3.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of qualitative studies included

| Study ID, year, Country | Aim | Participants and characteristics (sample size, gender, age, location, setting) | Method (study design and data collection) | Analysis | Themes (subthemes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sun, Chen et al. (2021), China | This study aimed to investigate whether patients with COVID‐19 in China experienced PTG and, if so, what changed for them during the process of PTG. |

N = 40 Male = 24 Female = 16 Age range from 19–68 Education:

Employment:

|

Qualitative descriptive approach; purposive sampling method; in‐depth semi‐structured interview conducted via cell phone or in person using social distancing |

Content analysis approach (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) | Three themes were emerged:

|

| Sun, Zhou, et al. (2021) China | To understand COVID patients' experiences of and perspectives on disclosure of their illness and to explore and describe the factors affecting disclosure decisions among COVID patients in China |

N = 26 Male = 12 Female = 14 Age range 19–56 years Mean age 34 Above college diploma = 20 At a COVID‐designated hospital in Shanghai |

Phenomenology study; Purposive sampling; Semi‐structured interview; In‐depth interview; (carried out by Wechat or Zoom) |

Giorgi's analysis approach (Giorgi, 2009) | Four themes were emerged:

|

| Cervantes, et al. (2021) USA | To describe the experiences of Latinx individuals who were hospitalised with and survived COVID‐19 |

N = 60 Male = 36 Female = 24 Age mean (SD) 48 (12) Latinx adults from low‐income areas In public hospitals in California |

Qualitative study; Purposive sampling; Semi‐structured phone interview; |

Qualitative thematic analysis according to the principles of grounded theory and thematic analysis (Corbin & Strauss, 2014) | Five themes were emerged:

|

| Sun, Wei, et al. (2021) China | To explore the psychology of COVID‐19 patients during hospitalisation |

N = 16 Male = 9 Female = 7 Age: Youth (18‐) 10; Middle‐aged (45‐) 5; Elderly (60‐) 1 In the department of a hospital in Henan province in China |

Phenomenological method; Robust sampling; Semi‐structured interviews (carried out by phone calls or face‐to‐face interviews) |

Colaizzi's phenomenological method (Trice, 1990) | Five themes were emerged:

|

| Missel et al. (2021) Denmark | To gain an in‐depth understanding of the meaning of a COVID‐19 illness trajectory from the patients' perspective |

N = 15 Male = 7 Female = 8 Mean age = 46 (range from 22–67 years old) |

Method of interpretive phenomenology; Convenience sampling strategy; Snowball sampling; Qualitative interview (carried out by telephone) |

Data collection, analysis, and interpretation were inspired by Ricoeur's philosophy, and Merleau‐ Ponty's phenomenology of perception and embodiment has been applied as a theoretical frame | Three themes were emerged:

|

|

Mukhtar et al. (2020) Nigeria |

To explore the experiences of patients with COVID‐19 |

N = 11 Male = 10 Female = 1 Average age = 44.6 Range from 21–70 years old From the major designated COVID‐19 treatment centre in Kano, Nigeria |

Descriptive phenomenological approach; Purposive sampling; Semi‐structured interviews; (carried out by telephone) |

Husserl's descriptive phenomenology, the van Kaam's method (Anderson & Eppard, 1998) | Four themes were emerged

|

| Zhang et al. (2020) China | To explore the uncertainty and experience of COVID‐19 patients who came from foreign countries |

N = 9 Male = 7 Female = 2 Mean age (SD) 30 (17.37) Age range from 19–62 years old Religious beliefs: all are Muslim In the hospital of Gansu province |

Phenomenological approach; Purposive sampling; Semi‐structured interviews; (carried out face to face) |

Colaizzi's phenomenological method | Three themes and eight subthemes were emerged:

|

| Li and Li (2020) China | To study the feeling of COVID‐19 patients |

N = 13 Male = 8 Female = 5 Age range = 37–80 years old |

Phenomenological approach; Convenience sampling; Semi‐structured interviews; In‐depth interviews; (carried out by online video chatting app) |

Colaizzi's phenomenological method | Three themes were emerged:

|

| Chen (2020) China | To explore the psychological feeling of COVID‐19 patients. |

N = 15 Male = 6 Female = 9 Age range = 17–78 years old |

Phenomenological approach; Convenience sampling; Semi‐structured interviews; In‐depth interviews; (carried out by online video chatting app) |

Colaizzi's phenomenological method | Four themes were emerged

|

| Zeng et al. (2020) China | To explore the real feeling and experiences of COVID‐19 patients. |

N = 10 Male = 3 Female = 7 Age range 33–74 years old |

Qualitative method; Thematic analysis; Convenience sampling; Semi‐structured interviews; In‐depth interviews; (carried out face‐to‐face) |

Content analysis (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004) | Three themes were emerged:

|

| Song et al. (2020) China | To study the psychological experience of the patients |

N = 8 Male = 6 Female = 2 Age range from 11–74 years old |

Phenomenological approach; Convenience sampling; Semi‐structured interviews; In‐depth interviews; (carried out face‐to‐face) |

Colaizzi's phenomenological method | Three themes were emerged:

|

| Yu et al. (2020) China | To study the reasons why patients with COVID‐19 tend to be anxious and depressed |

N = 18 Male = 4 Female = 14 Mean age (SD) 56.5 (13.8) age range 30–81 years old |

Phenomenological approach; Convenience sampling; Semi‐structured interviews; In‐depth interviews; (carried out face‐to‐face) |

Colaizzi's phenomenological method | Three themes were emerged

|

| Shaban et al. (2020) Australia | To explore the lived experience and perceptions of patients in isolation with COVID‐19 in an Australian healthcare setting. | N = 11 Male = 7 Female = 4, aged 27–61, Two reported comorbidities; one with hypertension and hypercholesterolemia, and the other with hypercholesterolemia and fatty liver |

Phenomenological approach from a Heideggerian hermeneutical perspective; semi‐structured interview; (carried out face‐to‐face) |

Diekelmann, Allen, and Tanner's seven‐step method (Diekelmann et al., 1989) | Five themes were emerged:

|

| Hao et al. (2020) China | To examine the neuropsychiatric sequelae of acutely ill patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) infection who received treatment in hospital isolation wards during the COVID‐19 pandemic |

N = 10 Gender: Male = 6, female = 4 Mean age = 37.4 Physical symptoms: No symptoms: 4 At least one symptom: 6 |

Mix methods, The qualitative part: semi‐structured interviews using open‐ended questions, face‐to‐face interviews with acutely ill COVID‐19 patients during their hospitalisation in various hospitals in Chongqing, China |

Using the concepts of grounded theory for data analyses |

Three themes were emerged patients' experience of the outbreak of epidemic:

|

| Kingstone et al. (2020) UK | To explore experiences of people with persisting symptoms following COVID‐19 infection, and their views on primary care support received |

N = 24 Gender: Male = 5 Female = 19 Age ranges from 22–68 |

Qualitative methodology of it with semi‐structured interviews Interviews were conducted by telephone or another virtual software (such as Microsoft Teams), according to the preference of the participant snowball sampling |

Thematic analysis (Guest et al., 2011) | Four themes were emerged:

|

| Liu and Liu (2021), China | To describe experiences of hospitalised patients with COVID‐19 following family cluster transmission of the infection and the meaning of these experiences for them |

N = 14 Gender: Male = 7 Female = 7 Age range from 30–73 Four were the index case in the family, while the other 10 contracted the disease from a close family member |

Descriptive phenomenological design Semi‐structured, in‐depth, face‐to‐face interviews were conducted between 1 March–25 March 2020 conducted in a large teaching hospital in Wuhan, China using a combination of convenience, snowball and purposive sampling strategies |

Colaizzi's method (Valle & King, 1978) | Two themes were emerged:

|

| Ladds et al. (2020) UK | To document such patients' lived experiences, including accessing and receiving healthcare, and ideas for improving services |

N = 114 Male = 34 Female = 80 Aged 27–73 years Eighty‐four were White British, 13 Asian, 8 White Other, 5 Black, and 4 mixed ethnicities. Thirty‐two were doctors and 19 other health professionals. Thirty‐one had attended hospital, of whom 8 had been admitted The study was conducted in the UK between May–September 2020 (towards the end of the first wave of the pandemic) |

Qualitative design; Convenience sampling, Snowball sampling 55 individual interviews and 8 focus groups (n = 59) individual interview: All but one interview were conducted by phone or by video using the business version of Zoom one (of a participant who was not comfortable using video) was done by email Phone and video interviews |

Constant comparative method (Glaser, 1965) | Four themes were emerged:

|

TABLE 3.

Methodological quality of qualitative studies (using JBI critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research)

| No of items a | Sun, Chen, et al. (2021) | Cervantes et al. (2021) | Sun, Wei, et al. (2021) | Missel et al. (2021) | Mukhtar et al. (2020) | Zhang et al. (2020) | Li and Li (2020) | Chen et al. (2020) | Zeng et al. (2020) | Song et al. (2020) | Yu et al. (2020) | Shaban et al. (2020) | Hao et al. (2020) | Kingstone et al. (2020) | Liu and Liu (2021) | Ladds et al. (2020) | Sun, Zhou, et al. (2021) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Y b | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 3 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 4 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 5 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 6 | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N |

| 7 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N |

| 8 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 9 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 10 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Total per cent of yes | 80 | 80 | 80 | 90 | 80 | 70 | 80 | 70 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 | 80 | 80 | 90 | 80 | 80 |

1. Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology? 2. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives? 3. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data? 4. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data? 5. Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results? 6. Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically? 7. Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice‐versa, addressed? 8. Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented? 9. Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, and is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body? 10. Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data?

Y = yes, N = no and U = unclear.

4.3. Results of synthesis

Following data extraction, 152 findings were classified as credible or unequivocal, identified from the 17 included studies (Appendix S2), and included in the meta‐aggregation. The findings were aggregated into 12 categories based on the similarity in meanings. From the 12 categories, 5 synthesised findings were developed: physical symptoms caused by the virus; positive and negative emotional responses to the virus; positive coping strategies as significant facilitators of epidemic prevention and control; negative coping strategies as obstacles to epidemic prevention and control from the perspective of the patients; and unmet needs for medical resource. The detailed process of synthesis, the composition of each category, and synthesised findings can be found in the Appendix S2.

4.3.1. Physical symptoms caused by the virus

The epidemic of COVID‐19 has caused many drastic changes for patients. A majority of patients reported that they experienced dyspnoea, headache, dizziness, fever, body weakness, palpitation, pain, nightmares, insomnia, brain fog and dietary changes after being infected (Kingstone et al., 2020; Mukhtar et al., 2020; Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). Their body, once being the source of strength, became weak, limp, and feeble after being infected. They even came to doubt the normal function of their body (Kingstone et al., 2020; Ladds et al., 2020; Missel et al., 2021). Two exemplar quotes follow: ‘I don't feel like eating, I can't sleep, and I have nightmares. My heart is agitated!’ (Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). ‘I got a serious pain in my lungs, and then I got nervous again. I never thought about where my lungs are, but suddenly I could feel them… It emphasizes the seriousness’ (Missel et al., 2021).

4.3.2. Positive and negative emotional responses to the virus

Unpleasant experience in quarantine

Due to the disruption of social connection, loss of time perspective, restrictive visiting of family members and witnessing other patients' death, the completely different treating strategies (Hao et al., 2020; Shaban et al., 2020; Sun, Wei, et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2020), patients in isolation ward usually reported unpleasant experience, which worsened as the duration of hospitalisation increased (Shaban et al., 2020). As a patient stated, ‘…… I had nothing, no windows, no one to talk to. …… We got no interaction.…… I mean, I have never been in jail before, but I would assume that it would be [a] similar experience. A little room’. (Shaban et al., 2020).

Sense of uncertainty of the epidemic

The majority of patients presented a sense of uncertainty to various degrees. The process of diagnosis was full of stress and contradiction. On one hand, patients dreaded the results of CT and viral nucleic acid tests being positive (Sun, Wei, et al., 2021; Zeng et al., 2020). On the other hand, they were factually in desperate need of the ‘best result’ (Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). As a patient said, ‘When the doctor told me the results, I felt my heart in my throat (heart palpitations) (Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). A sense of uncertainty arouse when the diagnosis could not be determined (Liu & Liu, 2021; Zhang et al., 2020)'.

After being diagnosed, the treatment and prognosis became the priority. Some patients were sceptical if the anti‐virus drugs (lopinavir and ritonavir) were used in HIV patients, and if the side effects such as drowsiness, nausea and vomiting would have a lasting effect on themselves (Zhang et al., 2020). Some patients even showed concern about the disease progress and the delay of discharge (Kingstone et al., 2020; Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). Two exemplar quotes were as follows: ‘I'm always worried. I keep asking the doctor about my diagnosis and I get the answer, you will be told when the test results come out (Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). It feels like roulette this virus (Missel et al., 2021)’.

Continuous mental loss and trauma

A lot of unpleasant experience continued throughout the whole illness trajectory, from being diagnosed and hospitalised to post‐discharge and returning to society, rather than fading away with the recovery from the disease (Missel et al., 2021). Rumination on these scenes usually happened during the phase of admission, hospitalisation or post‐discharge. The adverse events they experienced during the epidemic, such as the death of their relatives, brought persistent pain and agony to the patients (Liu & Liu, 2021). Patients expressed their concerns about the prognosis of the disease; they feared if the virus would have any lasting effect on their or their family's future life (Chen, 2020; Li & Li, 2020; Sun, Wei, et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2020).

To some patients, the virus had already caused persistent threats in their daily life (Liu & Liu, 2021). When they were making a recovery from the virus, they were exhausted both physically and mentally. They felt sad, oversensitive and feeble (Kingstone et al., 2020; Missel et al., 2021). They reported that they lost appetite and dyspnoea (Shaban et al., 2020). They even lost their sense of security, and self‐identification, expressing unrest emotions when recovering (Kingstone et al., 2020; Missel et al., 2021; Shaban et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020).

Feelings of stigma and discrimination were common for many patients (Chen, 2020; Hao et al., 2020; Liu & Liu, 2021; Missel et al., 2021; Mukhtar et al., 2020; Shaban et al., 2020; Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). The dominant concern for them was the possibility of the spread of the virus to their family members and friends. They felt guilty, self‐accusatory and sad when they were informed that their family members, neighbours, friends and even passers‐by were infected by them (Chen, 2020; Shaban et al., 2020; Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). Despite this, they never gave up the desire to be understood and respected by others (Chen, 2020). The process of returning to society was thus full of obstacles for some patients. Although not infectious, they still kept themselves indoors for fear that they could still be contagious (Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). When meeting others, what made them unpleasant was that people they met saw them as alienated and persistent stigma as if they had a plague (Chen, 2020; Hao et al., 2020; Liu & Liu, 2021; Missel et al., 2021; Mukhtar et al., 2020; Shaban et al., 2020; Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). As one patient stated: ‘It was strange coming out among other people again … they keep extra distance. There's something wrong… or people have respect for it. But it's a strange feeling…. I understand that they protect themselves, but it feels like you have a plague’. (Missel et al., 2021).

Feelings of powerlessness and despair

The COVID‐19 epidemic generated a sense of powerlessness and despair for many patients. Some immigrant patients felt powerless to cope with the contradiction between self‐protection and fear of financial disruption—the necessity of continuing to work and the desire of exempting themselves from getting infected (Cervantes et al., 2021). A sense of hopelessness was also generated in those who had access to medical help. After witnessing the seriousness of the disease, patients showed a pessimistic attitude towards recovery (Hao et al., 2020; Missel et al., 2021). During the early stage of the epidemic, patients expressed their outrage for their deprivation of privacy (Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). Being isolated in the isolation ward, the decrease in communication, and the dependence for self‐care on others, combined with the separation from loved ones, made patients fall into great despair (Song et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020). Their concerns about the possibility of the disease deteriorating and the dim prospect of recovery could also generate this feeling (Missel et al., 2021; Song et al., 2020). ‘I was scared … I'm 43 years old, can I die? This corona is scary because you are so sick and you have heard that just suddenly, people may die’. (Missel et al., 2021).

Post‐traumatic growth

Many patients presented positive psychological changes as a result of adversity. They finally had cause to rejoice and celebrate when they recovered from the disease (Missel et al., 2021). They showed great appreciation for still being alive (Sun, Chen, et al., 2021; Zeng et al., 2020). The awareness of the importance of their health had been reinforced; their proactive perspective of health care finally led to them developing good habits, such as wearing face masks or handwashing (Sun, Chen, et al., 2021). They showed their appreciation and gratitude for the staff who took care of them during their hospitalisation (Cervantes et al., 2021; Li & Li, 2020; Liu & Liu, 2021;Sun, Wei, et al., 2021; Zeng et al., 2020). They believed the doctor–patient relationship would be more harmonious due to the epidemic. Also, they were thankful to their relatives, friends and government (Sun, Chen, et al., 2021). They tended to embrace life and cherish friendships or family affection (Liu & Liu, 2021; Sun, Chen, et al., 2021; Sun, Wei, et al., 2021; Zeng et al., 2020). They preferentially shifted their thoughts from money and status to spiritual enhancement. They became more willing to help others in need (Li & Li, 2020; Liu & Liu, 2021; Sun, Chen, et al., 2021; Sun, Wei, et al., 2021; Zeng et al., 2020). Going through the COVID‐19 epidemic, the patients reported that they would be more optimistic and braver towards, whatever difficulty they encounter in their future life (Sun, Wei, et al., 2021; Zeng et al., 2020). One exemplar quote was as follows: ‘Family members did not abandon me or give up on me when it was my most difficult time. I am very happy. They are the most important. What is the use of money, power, and status when you do not have a life?’ (Sun, Wei, et al., 2021).

4.3.3. Positive coping strategies as facilitators of epidemic prevention and control

Individual cognitive preparedness

Many patients felt calm and at ease after being informed of the diagnosis with a positive attitude (Chen, 2020; Hao et al., 2020; Shaban et al., 2020; Sun, Wei, et al., 2021; Zeng et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020), although sometimes this process of adaption did not go smoothly at the beginning (Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). They tried their best to adjust themselves, such as diverting their attention, setting achievable goals daily (Hao et al., 2020; Sun, Wei, et al., 2021), and complying with the policy of epidemic prevention (Hao et al., 2020). Some patients tried to convince themselves to obey the arrangement of god (Cervantes et al., 2021; Mukhtar et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Most patients believed in the professional treatment and care provided by staff and the necessity for effective precaution measures against the epidemic (Hao et al., 2020; Mukhtar et al., 2020; Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). Patients appreciated the high standard of medical equipment (Mukhtar et al., 2020; Shaban et al., 2020). Patients felt tied and gradually dependent on the emotional support from staff (Hao et al., 2020; Missel et al., 2021; Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). The provision of protective measures from the government was of critical significance. It not only provided a solid foundation for epidemic prevention and control but also mitigated the stress of people during the epidemic (Hao et al., 2020). One exemplar quote was as follows: ‘The government has exempted the medical expenses of patients suffering from this disease, so that people can concentrate on recovering without worries’. (Hao et al., 2020).

Support from family, community and society

For some patients, family was described as ‘spiritual pillars’. They maintained their power and mental stability through support from their families (Song et al., 2020; Sun, Wei, et al., 2021). Meanwhile, support from family and friends can facilitate the prevention and control of the epidemic (Cervantes et al., 2021; Shaban et al., 2020). Also, the prevention of family members from becoming infected was a principal motivation for seeking medical help (Liu & Liu, 2021). Due to the policy, sense of responsibility, concern about being blamed and the desire to get support, patients often disclosed their infection condition to their family, intimate friends, community, colleagues and school. Consequently, they gained social support from family, friends, neighbours and strangers (Missel et al., 2021; Shaban et al., 2020; Sun, Zhou, et al., 2021.

Some patients were impressed by the community‐initiated measures against the epidemic (Shaban et al., 2020). Also, some patients regarded the information from people of the same ethnic groups as more persuasive (Cervantes et al., 2021). Additionally, some patients stressed the role media played in making people realise the severity of the COVID‐19 epidemic (Shaban et al., 2020). One exemplar quote was as follows: ‘Every day I am happiest when I have video communication with my family. They care about me and encourage me every day’. (Sun, Wei, et al., 2021).

4.3.4. Negative coping strategies as obstacles of epidemic prevention and control

Concealment of diagnosis

Concealment of diagnosis was a vital obstacle to epidemic prevention. Some patients were unwilling to disclose due to the perceived discrimination and concern of family members (Sun, Zhou, et al., 2021). For those who exposed their infected condition, there were costs of disclosure: they experienced discrimination, psychological distress, social isolation and exposure of privacy (Sun, Zhou, et al., 2021). One exemplar quote was as follows: ‘I was afraid to tell others that I had COVID… I can imagine that I would be rejected when others knew my status… To avoid people looking at me with strange eyes, I would not proactively disclose’. (Sun, Zhou, et al., 2021).

Lack of informational support

For patients, reliable information played a critical role in the upcoming plans and preparedness for COVID‐19 (Shaban et al., 2020). They were desperate to acquire knowledge about this strange virus. Although they made tremendous efforts in acquiring up‐to‐date information related to the epidemic (Kingstone et al., 2020), the source of authoritative information they preferred differed. Some patients were selective in choosing information and believed in official forums such as World Health Organisation (WHO). However, some patients regarded the official information, as sometimes misleading. They believed that news issued by governments and authorities was censored strictly to avoid people from being panicked, rather than free discussion and peer support (Ladds et al., 2020), thus being more subjective and sensational. So, they were critical of it (Shaban et al., 2020). The difficulty in accessing accurate information sometimes caused confusion, scepticism and anxiety (Cervantes et al., 2021; Kingstone et al., 2020; Shaban et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). Some felt their actual clinical symptoms were inconsistent with what the media reported (Shaban et al., 2020). One exemplar quote was as follows: ‘Internet support groups, yeah on the Facebook groups that I'm on, I mean, to be honest, I try not to read that group too much because it depresses me, makes me a bit anxious’. (Kingstone et al., 2020).

Difficulty and conflict in transition to sick role

Poor sick role behavioural compliance was also widely reported in studies. Some patients had a problem with sick role transition (Cervantes et al., 2021; Li & Li, 2020; Mukhtar et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Some of them had difficulties in adapting to the role of patients. They regarded COVID‐19 as a negligible and distant threat or ‘rationalised’ it as a conspiracy theory (Cervantes et al., 2021; Kingstone et al., 2020; Mukhtar et al., 2020), partly due to the invisibility of symptoms (Kingstone et al., 2020). They were unwilling to seek medical care (Cervantes et al., 2021; Missel et al., 2021; Mukhtar et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020). Some patients thought the ingrained social norms should be blamed for the poor control of the epidemic (Cervantes et al., 2021). When diagnosed with COVID‐19, they were shocked and suspicious (Hao et al., 2020; Shaban et al., 2020). As a patient said, ‘It was a bit surreal that I got infected by it… I couldn't believe…’ (Shaban et al., 2020).

When admitted to the medical centre, their feelings and emotions were liable to swing between trust, terror, security and isolation (Shaban et al., 2020). However, the rejection or delay of hospitalisation could sometimes be attributed to other reasons. Having no money, some immigrants were unwilling to hospitalise even if the disease deteriorated (Cervantes et al., 2021). Adopting an apathetic and passive attitude was another reason (Cervantes et al., 2021; Missel et al., 2021). On the contrary, some patients paid too much attention to their disease symptoms, worrying about their prognosis all the time (Sun, Wei, et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2020; Zeng et al., 2020). Conflict with the role was also reported in some studies. Some patients reported they lost their chance to assume the responsibility to take care of their families. The imbalance of individual and family well‐being made the patients anxious and shameful (Hao et al., 2020; Liu & Liu, 2021; Yu et al., 2020).

4.3.5. Unmet needs for medical resource

Coldness from staff

Many patients reported their desire for more attention from staff (Chen, 2020; Missel et al., 2021; Shaban et al., 2020). Due to the heavy workload and concerns about being infected, the communication between staff and patients was underestimated on a large scale (Chen, 2020; Missel et al., 2021; Shaban et al., 2020). Patients complained that they could not see the doctor and the nurse's faces due to the requirement for protective equipment, which was annoying (Missel et al., 2021). At the early stage of the outbreak of the epidemic, due to the lack of sufficient evidence about COVID‐19, doctors usually could not recognise symptoms and make the appropriate diagnosis; this weakened the interactions between the doctor and the patients (Kingstone et al., 2020). Patients reported that they just require direct contact with or more concern from the staff. However, the coldness and disregard from them made patients feel hurt and dehumanised (Chen, 2020; Kingstone et al., 2020; Shaban et al., 2020). One exemplar quote follows: ‘Doctors are afraid to come into the room I think, and they spend very little time, which I guess is understandable as well’. (Shaban et al., 2020).

Limited availability and dissatisfaction with healthcare resources

Due to the strong sense of social isolation and the suffocating surrounding of the isolation ward, some patients complained they lacked any effective approaches to relieve their feelings in the isolation centre, which is an unpleasure experience (Song et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020).

Complaints about the availability of healthcare resources such as isolation wards and the distance to the medical centre were made (Ladds et al., 2020). Patients called for better welfare (Cervantes et al., 2021; Chen, 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). They demanded free or less expensive treatment (Cervantes et al., 2021; Chen, 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). Some patients questioned why symptomatic and asymptomatic patients were mixed in the same room (Mukhtar et al., 2020). Some complained about the language barrier with the caregivers (Shaban et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2020). Patient education was also felt to be insufficient (Mukhtar et al., 2020). When discharged from the hospital, they still kept ignorant about the disease. Some patients also complained that their follow‐up service was unsatisfactory (Cervantes et al., 2021; Missel et al., 2021). One exemplar quote was as follows: ‘When I got home, I cried and there I was missing a follow‐up. I know that I have to take responsibility for my own health, but I lacked that anyone still cared for me’. (Missel et al., 2021).

5. DISCUSSION

The COVID‐19 epidemic has been an enormous catastrophe for patients (Cvetković et al., 2020). There was a sense of uncertainty throughout the whole process of being diagnosed, hospitalised and discharged (Durodié, 2020). The epidemic has also caused drastic changes in patients' lives. Our review has revealed the psychological reaction of the patients. In this systematic review, the results implied that quarantine caused many mental problems, such as anxiety and depression, consistent with other studies (Brooks et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2021). In addition, the results implied the reasons leading to the adverse psychological effects in the isolation ward were not confined to demographic characteristics such as age, education and income, as illustrated in other studies (Benke et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020; Tang et al., 2021). Quarantine, as a completely different treatment strategy, was accompanied by many negative experiences (Brooks et al., 2020; James et al., 2019), which is consistent with the experiences of other infectious diseases (Barratt et al., 2011; Siddiqui et al., 2019; Vottero & Rittenmeyer, 2012). These feelings could also arise from, the disruption of time perspectives (Shaban et al., 2020) and restrictive visiting by the family (Hugelius et al., 2021), as indicated in this synthesis.

Many studies we included were conducted in the early stage of the epidemic and they mainly focused on the state of being infected, which made the synthesised findings of this review largely related to the reactions and coping strategies in the acute phase. However, we still thought it could give implications for the long COVID and future research. A significant finding of our review was the psychosocial symptoms of long COVID. The social function of patients was affected to varying degrees. The experience of stigma and discrimination were common in patients and survivors, consistent with previous studies focusing on severe acute respiratory syndromes (SARS) or Ebola disease (James et al., 2019; Lau et al., 2006; Siu, 2008). People surrounding the patients are inclined to show discrimination against them even if they are cured of COVID‐19. Although sometimes, they choose to avoid others for fear of still being infectious. The COVID‐19 pandemic has caused persistent misery for patients (Bagcchi, 2020; Park et al., 2020). Previous studies have stressed the serious consequence of social stigma. Social stigma, once became a common phenomenon, may become an obstacle to the prevention and control of the epidemic—patients or people at risk of getting infected avoid early detection or other healthcare‐seeking behaviour (Des Jarlais et al., 2006; Torales et al., 2020). The stigma and discrimination may also harm the mental health of COVID‐19 survivors and affect their quality of life (Higgins et al., 2021; van Daalen et al., 2021). Additionally, in our systematic review, the results implied that patients were eager to be understood and respected despite being treated unequally. This inspires staff to attach adequate importance to tackling the social stigma derived from COVID‐19. Also, as advised by Bologna et al. (2021), considering that the feeling of stigma is extended to life after discharge, community engagement should be advocated to facilitate a successful return to society. This finding is important to understand the psychosocial problems of long COVID and warrants further examination. It is essential to explore the function of community and how it plays a role in tackling the stigma of patients discharged after COVID infection. This should be considered in updates of long COVID guidelines in future.

After experiencing adversity, some patients presented a positive psychological change. They showed a remarkable increase in their sense of responsibility for their friends, family and society. For example, some patients desired to be ambassadors within their living community. Former patients usually possess adequate information to communicate. This may be helpful in the prevention and control of the virus spread (Cervantes et al., 2021).

We also identify facilitators and obstacles to epidemic prevention based on patients' perspectives in this review. Consistent with Ebola patients, dread and denial were presented in patients when they were informed that they were being infected (James et al., 2019; Shultz et al., 2016). This delayed the manner of seeking medical help and leaded to symptom concealment and the spread of the epidemic. Additionally, factors related to social support seemed to be prominent in epidemic prevention and control. The significance of social support has been illustrated by previous studies (Yang et al., 2020). Informational support was inadequate in our review. As Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO's director‐general said ‘We're not just fighting a pandemic; we're fighting an infodemic (The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2020)’. Similar to previous studies, our studies implied that information from any kind of media can influence people's perspectives on the epidemic (Yang et al., 2020). Social media is a principal source of information. It facilitates the spread of useful information such as diagnosis, treatment and follow‐up procedures. However, it also disseminated fake news, and wrong measures against epidemic prevention, leading to anxiety and, consequently, the spread of the virus (González‐Padilla & Tortolero‐Blanco, 2020). Innovatively, our results implied that patients' preference for media depended not only on demographic characteristics such as gender, educational attainment and occupation (Zhao et al., 2020) but also on the characteristics of media. From the perspective of the patients, official media conveys more authoritative information, but it is sentimental and sometimes subjective because of its political purpose (Shaban et al., 2020). Social media allows free discussion, but it may spread some fake information. The diversity of its sources combined with the contradictory conclusions often makes patients confused, and in some extreme cases, leads to the rejection of quarantine measures (Song et al., 2020). Considering that misinformation travels so fast, strategies should be studied to ensure social media eliminates inaccurate and harmful information (Tasnim et al., 2020). Also, many people cannot discriminate between authentic information and fake information and fail to consider the accuracy and authenticity before sharing on social media (Pennycook et al., 2020). As indicated in one study (Ho et al., 2020), professional knowledge was a protective factor against public anxiety. Though often misunderstood, official media caused the lowest level of anxiety when compared with social media and commercial media (Liu & Liu, 2020). We advise that the information from official media should be promoted, especially when it is related to epidemic prevention and control (Ignacio & Teresa, 2020).

Isolated in the ward for a long time, it is easy for patients to feel alone. Some patients reported they were distressed by the coldness of the staff. Many staffs presented as emotionally and physically exhausted (Lang & Micah Hester, 2021; Luceño‐Moreno et al., 2020; Ruiz‐Fernández et al., 2020), which led to decreasing the ability to feel empathy for others and were unprepared to treat patients adequately. As a result, low satisfaction among patients was reported. Emotional support, crucial to combating loneliness and anxiety (Xiang et al., 2020; Zysberg & Zisberg, 2020), should not be ignored when patients receive treatment. Additionally, accurate and updated information about the epidemic can reduce some negative psychological effects (Wang et al., 2020). Strategies to facilitate communication between patients and staff can enhance the moral and ethical aspects of humanistic care (Mehrotra et al., 2013). This inspires staff to attach adequate significance to daily communication to mitigate the sense of uncertainty. Some methods used in SARS, such as mental health support and care supplied by a multidisciplinary mental health team, could be implemented (Xiang et al., 2020). To acquire a balance between the self‐protection of staff and the emotional support of patients, safe communication channels (such as video calls via Facetime and WeChat app) between patients and staff should be applied. After all, the holistic health of patients is our ultimate goal.

6. CONCLUSION

Psychological trauma caused by COVID‐19 is persistent. Unpleasant experience such as stigma existed for a long time rather than fading away with the recovery of the disease. Long COVID may hinder the return into society and reintegration of normal life of patients who are physically cured and discharged from the hospital. Staff should pay more attention to mental health. Emotional support from nurses, physicians and family members may mitigate the mental burden. Additionally, informational support is crucial in the prevention and control of the epidemic and reliable sources of information related to the epidemic should be promoted.

7. LIMITATIONS

Some limitations of this review should be acknowledged. Firstly, the topic has been widely researched in China, while limited in other countries. For example, in Africa, only one Nigerian study has been published. This indicated the necessity to explore real‐life experiences of patients in these areas considering the impact on different cultural backgrounds. Secondly, the long‐term impact of COVID‐19 is rarely reported in the published qualitative studies; thus, many of the findings were related to the acute phase. More qualitative studies focusing on the experience of long COVID should be conducted in the future. Additionally, although a systematic search was undertaken using appropriate searching strategies, publications not included in these databases could have been omitted. Moreover, due to the language limitation, we only included studies published in English and Chinese. The omittance may lead to information bias.

8. RELEVANCE TO CLINICAL PRACTICE

This review amalgamates the qualitative studies on patients diagnosed with COVID‐19 both in hospitalised and discharged settings. For healthcare professionals, knowing the patients' experiences can help them to plan interventions both physically and psychologically. There are several key messages for clinical practice. First, mental loss and trauma tend to become a persistent state. Healthcare professionals should provide appropriate psychological interventions to mitigate the negative psychological consequences of those patients in a long COVID state. Second, support from family, community and society can cause positive effects on the prevention and control of the epidemic. Nurses, as the healthcare professionals who may have the most touch with the patients, should evaluate the level of social support and redeploy it for the patients. Third, all healthcare professionals should listen to patients' needs and treat them with carefulness and adequate patience in order to decrease the unmet needs of patients.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supporting information

Appendix S1

Appendix S2

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to thank Professor Liu Yang for her expertise and assistance during the early stage of the project.

Zheng, X. , Qian, M. , Ye, X. , Zhang, M. , Zhan, C. , Li, H. , & Luo, T. (2022). Implications for long COVID: A systematic review and meta‐aggregation of experience of patients diagnosed with COVID‐19. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 00, 1–18. 10.1111/jocn.16537

Xutong Zheng and Min Qian contribute to this work equally.

Contributor Information

Xutong Zheng, Email: mmdzxt@outlook.com.

Min Qian, Email: qmbjmu@163.com.

Chenju Zhan, Email: chenjuzhan@yeah.net.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Anderson, J. , & Eppard, J. (1998). Van kaam’s method revisited. Qualitative Health Research, 8(3), 399–403. 10.1177/104973239800800310 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arieh, S. , Israel, L. , & Charles, M. (2017). Post‐traumatic stress disorder. The New England Journal of Medicine, 376(25), 2459–2469. 10.1056/NEJMra1612499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagcchi, S. (2020). Stigma during the COVID‐19 pandemic. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20(7), 782. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30498-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldassarre, A. , Giorgi, G. , Alessio, F. , Lulli, L. G. , Arcangeli, G. , & Mucci, N. (2020). Stigma and discrimination (SAD) at the time of the SARS‐CoV‐2 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6341. 10.3390/ijerph17176341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barratt, R. L. , Shaban, R. , & Moyle, W. (2011). Patient experience of source isolation: Lessons for clinical practice. Contemporary Nurse, 39(2), 180–193. 10.5172/conu.2011.180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benke, C. , Autenrieth, L. K. , Asselmann, E. A. , & Pané‐Farré, C. A. (2020). Lockdown, quarantine measures, and social distancing: Associations with depression, anxiety and distress at the beginning of the COVID‐19 pandemic among adults from Germany. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113462. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bologna, L. , Stamidis, K. , Paige, S. , Solomon, R. , Bisrat, F. , Kisanga, A. , Usman, S. , & Arale, S. (2021). Why communities should be the focus to reduce stigma attached to COVID‐19. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 104(1), 39–44. 10.4269/ajtmh.20-1329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S. K. , Webster, R. K. , Smith, L. E. , Woodland, L. , Wessely, S. , Greenberg, N. , & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes, L. , Martin, M. , Frank, M. G. , Farfan, J. F. , Kearns, M. , Rubio, L. A. , Tong, A. , Matus Gonzalez, A. , Camacho, C. , Collings, A. , Mundo, W. , Powe, N. R. , & Fernandez, A. (2021). Experiences of Latinx individuals hospitalized for COVID‐19. JAMA Network Open, 4(3), e210684. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q. (2020). Psychological experience of patients with COVID‐19: A qualitative study. Modern Hospitials, 20(11), 1685–1689. 10.3969/j.issn.1671-332X.2020.11.036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, V. , Flanders, S. , O'Malley, M. , Malani, A. , & Prescott, H. (2021). Sixty‐Day outcomes among patients hospitalized with COVID‐19. Annals of Internal Medicine, 174(4), 576–578. 10.7326/M20-5661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J. , & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Sage publications. [Google Scholar]

- Crook, H. , Raza, S. , Nowell, J. , Young, M. , & Edison, P. (2021). Long covid‐mechanisms, risk factors, and management. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 374, n1648. 10.1136/bmj.n1648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvetković, V. M. , Nikolić, N. , Radovanović Nenadić, U. , Öcal, A. , Noji, E. K. , & Zečević, M. (2020). Preparedness and preventive behaviors for a pandemic disaster caused by COVID‐19 in Serbia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4124. 10.3390/ijerph17114124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cénat, J. M. , Blais‐Rochette, C. , Kokou‐Kpolou, C. K. , Noorishad, P.‐G. , Mukunzi, J. N. , McIntee, S.‐E. , Dalexis, R. D. , Goulet, M.‐A. , & Labelle, P. R. (2021). Prevalence of symptoms of depression, anxiety, insomnia, posttraumatic stress disorder, and psychological distress among populations affected by the COVID‐19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Psychiatry Research, 295, 113599. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J. , Zhou, F. , Hou, W. , Silver, Z. , Wong, C. Y. , Chang, O. , Huang, E. , & Zuo, Q. K. (2021). The prevalence of depression, anxiety, and sleep disturbances in COVID‐19 patients: A meta‐analysis. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1486(1), 90–111. 10.1111/nyas.14506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais, D. C. , Galea, S. , Tracy, M. , Tross, S. , & Vlahov, D. (2006). Stigmatization of newly emerging infectious diseases: AIDS and SARS. American Journal of Public Health, 96(3), 561–567. 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diekelmann, N. L. , Allen, D. , & Tanner, C. A. (1989). The NLN criteria for appraisal of baccalaureate programs: A critical hermeneutic analysis. National League for Nursing. [Google Scholar]

- Durodié, B. (2020). Handling uncertainty and ambiguity in the COVID‐19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 12(S1), S61–S62. 10.1037/tra0000713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, A. (2009). The descriptive phenomenological method in psychology: A modified Husserlian approach. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 41(2), 269–276. 10.1163/156916210x526079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436–445. 10.2307/798843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- González‐Padilla, D. A. , & Tortolero‐Blanco, L. (2020). Social media influence in the COVID‐19 pandemic. International Brazilian Journal of Urology, 46(suppl 1), 120–124. 10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2020.s121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim, U. H. , & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G. , MacQueen, K. M. , & Namey, E. E. (2011). Applied thematic analysis. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, R. , & Dhamija, R. K. (2020). Covid‐19: Social distancing or social isolation? BMJ, 369, m2399. 10.1136/bmj.m2399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hao, F. , Tam, W. , Hu, X. , Tan, W. , Jiang, L. , Jiang, X. , Zhang, L. , Zhao, X. , Zou, Y. , Hu, Y. , Luo, X. , McIntyre, R. S. , Quek, T. , Tran, B. X. , Zhang, Z. , Pham, H. Q. , Ho, C. S. H. , & Ho, R. C. M. (2020). A quantitative and qualitative study on the neuropsychiatric sequelae of acutely ill COVID‐19 inpatients in isolation facilities. Translational Psychiatry, 10(1), 355. 10.1038/s41398-020-01039-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henssler, J. , Stock, F. , van Bohemen, J. , Walter, H. , Heinz, A. , & Brandt, L. (2021). Mental health effects of infection containment strategies: Quarantine and isolation‐a systematic review and meta‐analysis. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 271(2), 223–234. 10.1007/s00406-020-01196-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, V. , Sohaei, D. , Diamandis, E. P. , & Prassas, I. (2021). COVID‐19: From an acute to chronic disease? Potential long‐term health consequences. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences, 58(5), 297–310. 10.1080/10408363.2020.1860895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, H.‐Y. , Chen, Y.‐L. , & Yen, C.‐F. (2020). Different impacts of COVID‐19‐related information sources on public worry: An online survey through social media. Internet Interventions, 22, 100350. 10.1016/j.invent.2020.100350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh, H.‐F. , & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. , Huang, L. , Wang, Y. W. , Li, X. , Ren, L. , Gu, X. , Kang, L. , Guo, L. , Liu, M. , Zhou, X. , Luo, J. , Huang, Z. , Tu, S. , Zhao, Y. , Chen, L. , Xu, D. , Li, Y. , Li, C. , Peng, L. , … Cao, B. (2021). 6‐month consequences of COVID‐19 in patients discharged from hospital: A cohort study. The Lancet (London, England), 397(10270), 220–232. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32656-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugelius, K. , Harada, N. , & Marutani, M. (2021). Consequences of visiting restrictions during the COVID‐19 pandemic: An integrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 121, 104000. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, P. , Shevlin, M. , McBride, O. , Murphy, J. , Karatzias, T. , Bentall, R. P. , Martinez, A. , & Vallières, F. (2020). Anxiety and depression in the Republic of Ireland during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 142(3), 249–256. 10.1111/acps.13219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignacio, H.‐G. , & Teresa, G.‐J. (2020). Assessment of health information about COVID‐19 prevention on the internet: Infodemiological study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(2), e18717. 10.2196/18717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James, P. B. , Wardle, J. , Steel, A. , & Adams, J. (2019). Post‐Ebola psychosocial experiences and coping mechanisms among Ebola survivors: A systematic review. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 24(6), 671–691. 10.1111/tmi.13226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janiri, D. , Carfì, A. , Kotzalidis, G. D. , Bernabei, R. , Landi, F. , Sani, G. , & Gemelli Against COVID‐19 Post‐Acute Care Study Group . (2021). Posttraumatic stress disorder in patients after severe COVID‐19 infection. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(5), 567–569. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.0109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingstone, T. , Taylor, A. K. , O'Donnell, C. A. , Atherton, H. , Blane, D. N. , & Chew‐Graham, C. A. (2020). Finding the ‘right’ GP: A qualitative study of the experiences of people with long‐COVID. BJGP Open, 4(5), bjgpopen20X101143. 10.3399/bjgpopen20X101143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladds, E. , Rushforth, A. , Wieringa, S. , Taylor, S. , Rayner, C. , Husain, L. , & Greenhalgh, T. (2020). Persistent symptoms after Covid‐19: Qualitative study of 114 “long Covid” patients and draft quality principles for services. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 1–13. 10.1186/s12913-020-06001-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang, K. R. , & Micah Hester, D. (2021). The centrality of relational autonomy and compassion fatigue in the COVID‐19 era. The American Journal of Bioethics: AJOB, 21(1), 84–86. 10.1080/15265161.2020.1850914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau, J. T. F. , Yang, X. , Wong, E. , & Tsui, H. Y. (2006). Prevalence and factors associated with social avoidance of recovered SARS patients in the Hong Kong general population. Health Education Research, 21(5), 662–673. 10.1093/her/cyl064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurie, G. J. , Elli, G. P. , Dineen, L.‐D. B. , Themba, N. , Tamara, F. , Gupta, A. , Rasouli, L. , Zetkulic, M. , Balani, B. , Ogedegbe, C. , Bawa, H. , Berrol, L. , Qureshi, N. , & Aschner, J. L. (2020). Persistence of symptoms and quality of life at 35 days after hospitalization for COVID‐19 infection. PLoS One, 15(12), e0243882. 10.1371/journal.pone.0243882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, C. , Glanville, J. , Briscoe, S. , Littlewood, A. , Marshall, C. , Metzendorf, M.‐I. , Noel‐Storr, A. , Rader, T. , Shokraneh, F. , Thomas, J. , Wieland, L. S. , & Group, on behalf of the C. I. R. M (2019). Searching for and selecting studies. In Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (pp. 67–107). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. 10.1002/9781119536604.ch4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li, F. , & Li, L. (2020). A qualitative study of the psychological experience of COVID‐19 patients. Journal of Qilu Nursing, 26(10), 53–57. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-7256.2020.10.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, C. , & Liu, Y. (2020). Media exposure and anxiety during COVID‐19: The mediation effect of media vicarious traumatization. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4720. 10.3390/ijerph17134720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W. , & Liu, J. (2021). Living with COVID‐19: A phenomenological study of hospitalised patients involved in family cluster transmission. BMJ Open, 11(2), e046128. 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lockwood, C. , Munn, Z. , & Porritt, K. (2015). Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta‐aggregation. International Journal of Evidence‐Based Healthcare, 13(3), 179–187. 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luceño‐Moreno, L. , Talavera‐Velasco, B. , García‐Albuerne, Y. , & Martín‐García, J. (2020). Symptoms of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, depression, levels of resilience and burnout in Spanish health personnel during the COVID‐19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(15), 5514. 10.3390/ijerph17155514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehrotra, P. , Croft, L. , Day, H. R. , Perencevich, E. N. , Pineles, L. , Harris, A. D. , Weingart, S. N. , & Morgan, D. J. (2013). Effects of contact precautions on patient perception of care and satisfaction: A prospective cohort study. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 34(10), 1087–1093. 10.1086/673143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missel, M. , Bernild, C. , Westh Christensen, S. , Dagyaran, I. , & Kikkenborg Berg, S. (2021). The marked body – A qualitative study on survivors embodied experiences of a COVID‐19 illness trajectory. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences., 36, 183–191. 10.1111/scs.12975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar, N. B. , Abdullahi, A. , Abba, M. A. , & Mohammed, J. (2020). Views and experiences of discharged COVID‐19 patients in Kano, Nigeria: A qualitative study. The Pan African Medical Journal, 37(Suppl 1), 38. 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.37.38.26609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidu, S. B. , Shah, A. J. , Saigal, A. , Smith, C. , Brill, S. E. , Goldring, J. , Hurst, J. R. , Jarvis, H. , Lipman, M. , & Mandal, S. (2021). The high mental health burden of “long COVID” and its association with on‐going physical and respiratory symptoms in all adults discharged from hospital. European Respiratory Journal, 57(6), 2004364. 10.1183/13993003.04364-2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, H. Y. , Jung, J. , Park, H. Y. , Lee, S. H. , Kim, E. S. , Kim, H. B. , & Song, K.‐H. (2020). Psychological consequences of survivors of COVID‐19 pneumonia 1 month after discharge. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 35(47), e409. 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennycook, G. , McPhetres, J. , Zhang, Y. , Lu, J. G. , & Rand, D. G. (2020). Fighting COVID‐19 misinformation on social media: Experimental evidence for a scalable accuracy‐nudge intervention. Psychological Science, 31(7), 770–780. 10.1177/0956797620939054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz‐Fernández, M. D. , Ramos‐Pichardo, J. D. , Ibáñez‐Masero, O. , Cabrera‐Troya, J. , Carmona‐Rega, M. I. , & Ortega‐Galán, Á. M. (2020). Compassion fatigue, burnout, compassion satisfaction and perceived stress in healthcare professionals during the COVID‐19 health crisis in Spain. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(21–22), 4321–4330. 10.1111/jocn.15469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, H. , Wolpert, M. , & Greenhalgh, T. (2020). Managing uncertainty in the covid‐19 era. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 370, m3349. 10.1136/bmj.m3349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaban, R. Z. , Nahidi, S. , Sotomayor‐Castillo, C. , Li, C. , Gilroy, N. , O'Sullivan, M. V. N. , Sorrell, T. C. , White, E. , Hackett, K. , & Bag, S. (2020). SARS‐CoV‐2 infection and COVID‐19: The lived experience and perceptions of patients in isolation and care in an Australian healthcare setting. American Journal of Infection Control, 48(12), 1445–1450. 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.08.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher, L. (2020). COVID‐19, anxiety, sleep disturbances and suicide. Sleep Medicine, 70, 124. 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.04.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L. , Lu, Z.‐A. , Que, J.‐Y. , Huang, X.‐L. , Liu, L. , Ran, M.‐S. , Gong, Y.‐M. , Yuan, K. , Yan, W. , Sun, Y.‐K. , Shi, J. , Bao, Y.‐P. , & Lu, L. (2020). Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 3(7), e2014053. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz, J. M. , Althouse, B. M. , Baingana, F. , Cooper, J. L. , Espinola, M. , Greene, M. C. , Espinel, Z. , McCoy, C. B. , Mazurik, L. , & Rechkemmer, A. (2016). Fear factor: The unseen perils of the Ebola outbreak. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 72(5), 304–310. 10.1080/00963402.2016.1216515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui, Z. K. , Conway, S. J. , Abusamaan, M. , Bertram, A. , Berry, S. A. , Allen, L. , Apfel, A. , Farley, H. , Zhu, J. , Wu, A. W. , & Brotman, D. J. (2019). Patient isolation for infection control and patient experience. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, 40(2), 194–199. 10.1017/ice.2018.324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siu, J. Y. (2008). The SARS‐associated stigma of SARS victims in the post‐SARS era of Hong Kong. Qualitative Health Research, 18(6), 729–738. 10.1177/1049732308318372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y. , Ma, J. , & Pang, X. (2020). Qualitative study of psychological experience in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. Journal of Changzhi Medical College, 34(2), 105–108. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-0588.2020.02.006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, N. , Wei, L. , Wang, H. , Wang, X. , Gao, M. , Hu, X. , & Shi, S. (2021). Qualitative study of the psychological experience of COVID‐19 patients during hospitalization. Journal of Affective Disorders, 278(1), 15–22. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, W. , Chen, W.‐T. , Zhang, Q. , Ma, S. , Huang, F. , Zhang, L. , & Lu, H. (2021). Post‐traumatic growth experiences among COVID‐19 confirmed cases in China: A qualitative study. Clinical Nursing Research, 30(7), 1079–1087. 10.1177/10547738211016951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]