Abstract

Objective

The COVID‐19 pandemic has led to greater societal divides based on alignment with vaccine mandates and social distancing requirements. This paper briefly lays out the experiences of individuals in Aotearoa New Zealand related to public health messaging.

Methods

Adults in Aotearoa New Zealand participated in a mixed‐methods study involving a survey (n=1,010 analysed results) and then semi‐structured interviews with a subset of surveyed participants (38 participants). Results were thematically analysed.

Results

Participants highlighted two key areas related to public health messaging, these related to message consistency and the impact of messaging on wellbeing.

Conclusions and public health implications

As the COVID‐19 pandemic continues and further disrupts health service delivery and normal societal functioning, forward planning is needed to deliver more targeted messaging.

Key words: health messaging, COVID‐19, pandemic, Aotearoa New Zealand, public health

In 2020, Aotearoa New Zealand's stringent COVID‐19 policy response was highly regarded worldwide.1, 2, 3 National messaging focussed on ‘staying home’ secure in ‘bubbles’, ‘being kind’ as part of a ‘team of five million’, and ‘going hard and early’ to prevent transmission. This messaging, delivered through the Government's daily press briefings built trust and created support for collective action, partly due to the public health‐led approach.4 These messages were mainly consistent with key crisis communication principles including transparency, timeliness, empathy and clarity.5 However, research undertaken in New Zealand's 2020 stringent level 4 lockdown highlights the negative impact of ineffective health messaging on accessing primary care services in Palmerston North (New Zealand) throughout the pandemic,6 suggesting discrepancies between positive national messaging and the real‐time impact on individuals accessing health services. Similarly, international research highlights health communication challenges during the pandemic.7, 8

We have previously reported on challenges individuals faced interpreting national messages, in the context of accessing primary health care.9 In this paper, we highlight perspectives on public health messaging from research on the health experiences of New Zealand adults (18 years +) during the first nationwide lockdown.

Methods

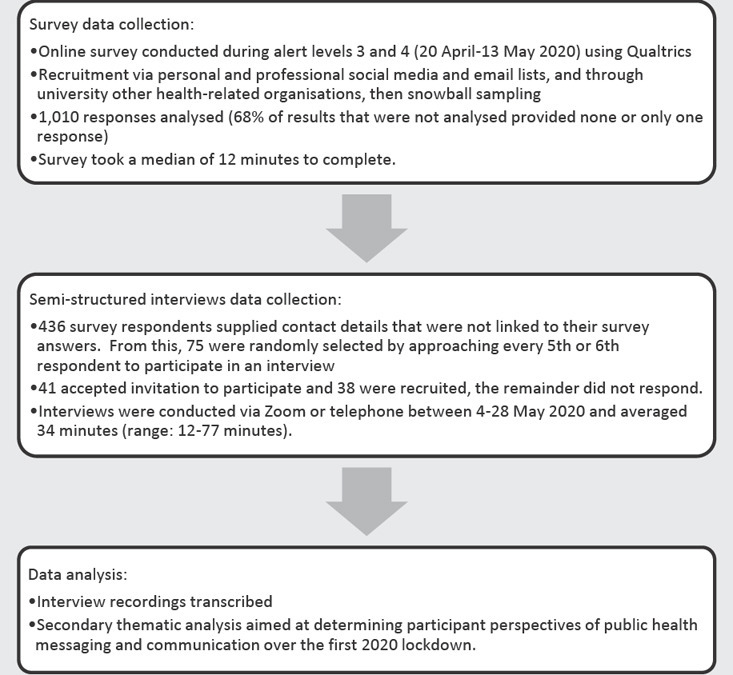

Our mixed‐methods research involved a survey (S) of 1,010 individuals living in Aotearoa who accessed or wanted to access health services during the first lockdown (March‐April 2020) (our earlier work provides detailed survey methods10). We then conducted semi‐structured interviews (I) with 38 survey participants. This paper focuses on open‐ended comments survey and interview participants made around public health communication, and represents a secondary analysis of data. Figure 1 lays out key data collection and analysis steps.

Figure 1.

Data collection and analysis methods.

Results

Participants’ comments focussed on two main areas: (1) message consistency and (2) the impact of information on wellbeing.

Message consistency

Participants described content differences in messaging at the national and local levels. These differences meant individuals were uncertain about how to access health services with localised health service rules imposing additional barriers.

[I am] really confused … [the Government] would have been put (sic) lots of money and resource into sending up these messages nationwide but only have maybe the opposite being told to you in your [geographic] region … It's almost like you have to do a bit more just to get in to see the doctor (Int.34)

Participants also commented on the role of leaders, primarily the Prime Minister (PM) of New Zealand Ms Ardern, and the Director‐General of Health Dr Bloomfield, in delivering these messages. People had trust and confidence in these individuals, but information that was not specific enough adversely influenced an individual's decision making.

Dr Bloomfield say[s], “You should go to your doctor if you think you need to”. But it's that ‘if you think you need to’ … All of those issues are exacerbated by that fact that everyone feels that it's a big scary pandemic out there and so maybe the slight pain in my heart doesn't mean it [is] such a serious [health problem]. (Int.18)

Notably, one survey participant identified the role higher beings play in their lives and the influence this had on their willingness to engage with public health messaging. In turn, this suggests that while consistency is important, there are populations that cannot be reached by messaging.

People like to go with the crowd, listening to the mainstream media ‐ who are constantly shoving the coronavirus down people's throats … it is no wonder people are scared. But not me. God has a plan for my life and that of my family. (S)

Impact on wellbeing

Participants linked messaging to their personal and family wellbeing. One participant reflected on the effect of receiving conflicting information on the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) at work, which impacted how they viewed their personal and family safety.

The different information you were getting from different people saying different things and about different stuff related to PPE, I was more concerned about bringing something home. (Int.22)

Another participant highlighted that messaging to ‘be kind’ influenced community behaviour but may have counterintuitively meant that people did not think they should discuss their distress or seek support.

I think from the PM around being kind, there was such positive messages … But, it doesn't replace the fact that people need to talk about what is going on for them. And how they are coping with probably the isolation. (Int.37)

Alongside directives around social distancing, participants described the importance of having supportive statements around managing what could be perceived as ‘normal’ mental distress during a pandemic. Participants considered campaigns like Equally Well (https://www.ranzcp.org/practice-education/guidelines-and-resources-for-practice/physical-health) and All Right? (https://www.allright.org.nz/about) as facilitating recognition of the importance of maintaining wellbeing. One participant hoped such messaging would change the way distress is generally treated.

It's taken a pandemic for there to be public messaging about the experience of mental distress to be normal … This can be an opportunity for our health care system to actually start to question what it considers illness and what it considers appropriate response. (Int.18)

Discussion

Public messaging in a crisis is a powerful tool to influence a positive collective response; information consistency and impact on wellbeing are key factors for listeners. Our study did not include those aged <18 years and, owing to its snowball sampling method, may not be generalisable to the wider New Zealand population. However, it points to the need to continually evaluate and improve messaging consistency at the national and health system level (a call supported by other New Zealand researchers6) and for different localities to align service access and provision with this information. There is also a need for ongoing public health communication to normalise, and address, mental distress.

These findings remain significant in 2022, as collective approaches have dissipated over time and the country is divided by vaccination/anti‐vaccination rifts7, 11 and previously in 2021 by geographically divided alert levels. Messaging such as ‘be kind’ and ‘we are in this together’ have reduced and there is a lack of targeted countrywide health promotion campaigns including those to promote mental health literacy. Given the influence the pandemic has on expanding inequalities, it is timely to reassess national health promotion messages.

Conclusions and public health implications

The pandemic has had unprecedented effects globally, with growing evidence of its impact on mental health and wellbeing. As its effects continue and further disrupt health service delivery, more targeted public health messaging focused on facilitating continued health care access and personal and community wellbeing are timely.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all survey respondents and interviewees. We also thank our wider team members, professional and personal networks, and colleagues who helped disseminate the online survey. We also acknowledge Drs Janet McDonald and Lynne Russell for interview assistance. Other members of the Primary Care Programme team were involved in obtaining funding from the Health Research Council (ref # 18/667) for this work.

Ethics

This project received Victoria University of Wellington Human Ethics Committee approval (#0000028485).

Acknowledgments

Health Research Council (# 18/667)

Footnotes

The authors have stated they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.O'Brien E, Chang R, Varley K, Tam F, Munoz M, Tan A. The best and worst places to be as winter meets Omicron. Bloomberg Daybreak: Asia. 2021 Aug;10;4:50am. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Economist Intelligence Unit . The Economist; London (UK): 2020. How Well Have OECD Countries Responded to the Coronavirus Crisis? [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hale T, Webster S, Petherick A, Phillips T, Kira B. University of Oxford Blavatnik School of Government; Oxford (UK): 2020. Oxford COVID‐19 Government Response Tracker. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beattie A, Priestley R. Fighting COVID‐19 with the team of 5 million: Aotearoa New Zealand government communication during the 2020 lockdown. Soc Sci Humanit Open. 2021;4(1) doi: 10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacKay M, Colangeli T, Gillis D, McWhirter J, Papadopoulos A. Examining social media crisis communication during early COVID‐19 from public health and news media for quality, content, and corresponding public sentiment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15) doi: 10.3390/ijerph18157986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blake D, Thompson J, Chamberlain K, McGuigan K. Accessing primary healthcare during COVID‐19: Health messaging during lockdown. Kōtuitui: N Z J Soc Sci Online. 2022;17(1):101–115. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Street JRL, Finset A. Two years with COVID‐19: New ‐ and old ‐ challenges for health communication research. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(2):261–264. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2022.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tagliacozzo S, Albrecht F, Ganapati NE. International perspectives on COVID‐19 communication ecologies: Public health agencies’ online communication in Italy, Sweden, and the United States. Am Behav Sci. 2021;65(7):934–955. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Imlach F, McKinlay E, Kennedy J, Pledger M, Middleton L, Cumming J, et al. Seeking healthcare during lockdown: Challenges, opportunities and lessons for the future. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2021 doi: 10.34172/ijhpm.2021.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Officer TN, Imlach F, McKinlay E, Kennedy J, Pledger M, Russell L, et al. COVID‐19 pandemic lockdown and wellbeing: Experiences from Aotearoa New Zealand in 2020. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(4) doi: 10.3390/ijerph19042269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porter N. Covid‐19: Team of five million no more ‐ what life will look like for the unvaccinated. 2021 Stuff.co.nz Nov;27;5:00am. [Google Scholar]