Abstract

Background

Since the start of the global COVID‐19 pandemic in 2019, critical care nurses across the world have been working under extreme levels of pressure.

Aim

To understand critical care nurses' experiences of and satisfaction with their role in the pandemic response across the United Kingdom (UK).

Study Design

A cross‐sectional electronic survey of critical care nurses (n = 339) registered as members of the British Association of Critical Care Nurses. Anonymous quantitative and open‐ended question data were collected in March and April 2021 during the height of the second surge of COVID‐19 in the UK via an online questionnaire. Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics and free text responses were collated and analysed thematically.

Results

There was a response rate of 17.5%. Critical care nurses derived great satisfaction from making a difference during this global crisis and greatly valued teamwork and support from senior nurses. However, nurses consistently expressed concern over the quality of safe patient care, which they perceived to be suboptimal due to staff shortages and a dilution of the specialist skill mix. Together with the high volume of patient deaths, critical care nurses reported that these stressors influenced their personalwell‐being.

Conclusions

This study provides insights into the key lessons health care leaders must consider when managing the response to the demands and challenges of the ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic. COVID‐19 is unpredictable in its course, and what future variants might mean in terms of transmissibility, severity and resultant pressures to critical care remains unknown.

Relevance to Clinical Practice

Future responses to the challenges that critical care faces must consider nurses' experiences and create an environment that engenders supportive teamwork, facilitates excellent nursing practice and effective safe patient care where critical care nursing may thrive.

Keywords: context/policy issues in critical care, critical care nurses, management and organization of ICU, nurse–patient ratio, questionnaire design/survey

What is known about the topic

Since the start of the global COVID‐19 pandemic in 2019, critical care nurses across the world have been working under extreme levels of pressure.

The pandemic has had a significant impact on critical care nurses' mental and physical well‐being.

What this paper adds

Highlights the perceived personal and professional benefits from being part of the COVID‐19 response, as well as the challenges

Nurses expressed concern over the quality of safe patient care which they felt was compromised due to staff shortages, increased workload and dilution of the specialist skills mix

Nurses insights and experiences must be considered when managing the response to the demands and challenges of the ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic

1. INTRODUCTION/BACKGROUND

Since the start of the global COVID‐19 pandemic in 2019, nurses and health care systems across the world have been working under extreme levels of pressure. Morbidity and mortality rates have increased around the world leading to an unprecedented demand for critical care services. 1 Large numbers of registered nurses have also been infected with COVID‐19 and many have died. 2

In addition to coping with an overwhelming number of critically ill patients and a lack of beds and resources, health care staff have had to contend with supply chain failures leading to insufficient personal protective equipment, medication, oxygen supplies and equipment. 3 The pre‐existing global shortage of specialist trained critical care nurses was also made worse by the pandemic and to optimize patient safety, critical care nurses had to dramatically change the way in which they work and deliver care. In the United Kingdom (UK), in contrast to the usual ratio of one nurse to one or two patients, depending on their level of care need, 4 critical care nurses have had to care for up to four, five or sometimes more critically ill patients with support from nurses and health care professionals from other specialities and from other non‐registered staff. 5 This has put tremendous pressure on health care systems and health care professionals alike.

Research findings highlight the negative impact the pandemic has had on registered nurses' mental health andwell‐being. One cross‐sectional survey of registered nurses in China by Leng et al. 6 found evidence of symptoms of stress, with 5.6% of the sample reporting clinically significant Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Reported sources of stress included isolation, shortages of personal protective equipment, physical and emotional exhaustion, intensive workload, fear of being infected, and insufficient work experiences with COVID‐19. A multinational cross‐sectional study by Denning et al., 7 surveying 3537 health care workers also reported that 2364 (67%) screened positive for burnout, 701 (20%) for anxiety and 389 (11%) for depression. Similarly, Şanlıtürk 8 reported 62% of nurses in their cross‐sectional survey (n = 262) had a moderate level of occupational stress. In addition, research findings highlight a range of occupational stressors associated with caring for critically ill patients with COVID‐19 including poor communication with management, high workload and inability to provide adequate care to patients and families, being asked to participate in tasks for which they had not been trained, poor working conditions, shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), fear of being infected with COVID‐19 and lack of availability of testing. 8 , 9 , 10

Despite the significant stressors associated with the COVID‐19 pandemic, research also identifies potential mediating factors to help nurses cope with the challenges of the pandemic. These include high levels of job satisfaction and organizational commitment 11 and the provision of robust organizational support to help health care staff persevere and overcome the unprecedented challenges of COVID‐19. 12 Pagnucci et al. 13 also highlight the importance of togetherness and collaboration as positively influences on nurses' well‐being; alongside effective support, communication and socializing with colleagues.

As the pandemic evolves, nurses continue to work under significant pressure. The longer‐term impact of these extreme levels of stress on individuals' well‐being, and retention and recruitment are as yet unknown. To mitigate the negative impact, it is critical that the rapidity of change in demands on critical care nurses is mirrored by effective and adaptive senior support and leadership. To effectively support the future workforce to face the ongoing demands of the global pandemic, it is essential that we understand nurses perspectives and use these to inform future workforce models.

2. RESEARCH AIM

This study aimed to understand critical care nurses' satisfaction with and experiences of their role in the COVID‐19 pandemic response across the United Kingdom (UK).

Specific objectives were to:

Assess critical care nurses' satisfaction with their role during COVID‐19.

Explore critical care nurses' perceptions of the positive and challenging aspects of their work.

3. DESIGN AND METHODS

This study employed a cross‐sectional electronic survey (e‐survey) design and is reported in accordance with the guidance published by Latour and Tume 14 and the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet (CHERRIES). 15

3.1. Sample, setting and recruitment

All nurses registered as members of the British Association of Critical Care Nurses (BACCN) were invited to participate in this closed e‐survey. The BACCN is a non‐profit organization representing critical care nurses across the UK. No target sample was set. Our aim was to recruit as many BACCN members as possible. There are 1794 members from all regions of the UK, representing all pay bands and nursing roles within critical care (BACCN Membership Report, 2022). 16

After receiving an email invite from the BACCN administrative team, BACCN members who wanted to participate accessed the e‐survey by clicking an online link embedded into the email. The e‐survey was administered utilizing Qualtrics XM software. Participants were able to review and change responses before submitting the completed e‐survey. Only one response per email and Internet Protocol address was allowed. We offered no incentives for participation. This was therefore a convenience sample.

3.2. Data collection

Anonymous data were collected in March and April 2021 during the height of the second surge of COVID‐19 in the UK. An e‐survey was developed from a pre‐existing tool used as part of a service evaluation by staff at the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital 17 With permission from the original research team, the face and content validity of the e‐survey was reviewed by an expert panel of critical care nurse academics and clinicians who agreed minor changes that reflected the general critical care nurse population. The final e‐survey consisted of 18 questions across three domains: eight questions that used a 5‐point Likert scale assessing satisfaction (Cronbach alpha co‐efficient 0.87344), six open‐ended questions and four demographic questions (Data S1).

3.3. Data analysis

Categorical data are presented using frequencies and percentages. Continuous level data were analysed as mean, interquartile range or range, as appropriate. Free text responses to open‐ended questions were collated and analysed thematically utilizing the six‐step framework described by Braun and Clarke. 18 Initial codes identified by LCS and independently reviewed by SB, NC and CP. Initial themes were reviewed and discussed by all authors until a consensus on the final themes was agreed. Qualitative data were stored and managed using NVivo Version 12.

3.4. Approvals

The study was approved by the BACCN Executive Board in line with its guidance for supporting research. Informed consent was obtained and encrypted; anonymous data was stored in a double password‐protected electronic drive.

4. RESULTS

Of the 339 respondents (response rate 17.5%), 233 (69%) completed the e‐survey in full. Forty‐nine (14%) respondents completed the first eight Likert scale questions and the demographic information questions but did not answer the open‐ended questions. Fifty‐six (16%) respondents completed less than four questions of the first Likert scale questions; these responses were not included in the final analysis.

Two hundred and thirty (68%) of the respondents were female, with four people (1%) preferring not to say. Years of experience in critical care ranged from 6 months to 40 years (Mean 16.43 years ± 10.2 years). Table 1 shows respondent demographics.

TABLE 1.

Respondent demographics

| Demographic | n(%) |

|---|---|

| Type of nurse | |

| Adult nurse with university accredited critical care course | 227 (80%) |

| Adult nurse without university accredited critical care course | 47 (17%) |

| Other a | 8 (3%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 230 (68%) |

| Male | 48 (31%) |

| Prefer not to say | 4 (1%) |

| Number of years' experience as a registered nurse | |

| 0–10 years | 96 (35%) |

| 11–20 years | 87 (31%) |

| 21–30 years | 68 (24%) |

| 31–40 years | 31 (10%) |

Other types of nurses included those working in the military, research, outreach and education.

As shown in Figure 1, 195 (69%) of respondents were pleased to be part of the COVID‐19 response team and felt that they had made a difference (236, 84%). However, 48 (17%) reported not being confident that they had provided good care, despite most reporting adequate informal education/ training (222, 79%). Variable responses were reported about whether respondents received adequate support from their seniors, with 78 (27%) disagreeing with this statement. Sixty‐one (22%) also reported not perceiving their contribution to be recognized by others. Many respondents agreed that redeployed colleagues added value to care provision in intensive care with only 31 (11%) disagreeing.

FIGURE 1.

Results of Likert scale questions

5. QUALITATIVE FINDINGS

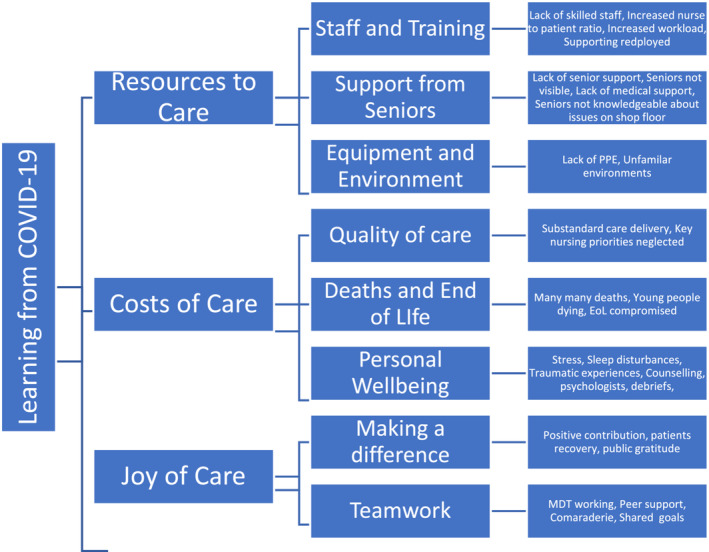

Two hundred and thirty‐three respondents (69%) provided responses to the open‐ended questions at the end of the survey. Many respondents left lengthy and rich accounts of their experiences of the pandemic, which were grouped into three main themes, each underpinned by 2–3 sub‐themes derived from the process of coding (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Qualitative themes, subthemes and codes

6. RESOURCES TO CARE

This theme describes the resources required to provide critical care during the pandemic including staffing, equipment and environmental resources and support from senior and medical staff.

6.1. Staff and training

Respondents reported how challenging they found the lack of skilled staff and increase in patient: nurse ratios, as this made their workload feel unmanageable. Respondent 40 commented, “The high acuity of patients and the low skill mix of staff and too many patients was a daily nightmare”.

Despite the quantitative data revealing that most respondents valued redeployed staff and felt confident in supporting them, qualitative comments suggest that this aspect of their work was also very demanding. Respondent 106 described the challenge of, “working with a lot of staff with no prior level 3 experience and having to provide a lot of support despite being relatively junior myself”. Respondents highlighted that due to the frequent rotation of redeployed staff, there was a continual need for training and upskilling staff. Many respondents called for better staff planning where redeployed staff stayed for longer periods of time with ongoing training so that knowledge and skills are maintained, and competence developed for future surges. However, as respondent 51 highlights, some respondents felt ill‐equipped to support the training needs of redeployed staff due to a lack of leadership skills: “Development isn't just about clinical skills. A lot of our junior staff struggled being leaders, planning tasks and structuring a shift while prioritising what needed to happen to keep patients and staff safe … {they} don't see the bigger picture of running the unit”.

6.2. Support from seniors

As evident from the quantitative data, the perception of support from senior staff was polarized. Some respondents reported great leadership and support from their seniors. For example, respondent 34 stated, “On my unit, there was an exceptional demonstration of leadership. Caring leadership that understood the pressures and responded with empathy”. In contrast, others noted a lack of support from nursing management and a lack of visibility of senior staff in the clinical area. “Managers relocated to covid‐safe workspaces, which unfortunately were inaccessible to staff and meant it was very difficult to check‐in or raise any issues” (Respondent 159). The reported absence of senior staff from clinical areas meant that nurses did not feel as although the senior management completely understood the issues and everyday challenges that they were facing; “I found there was a lack of insight from managers about unrealistic nurse patients ratios and being told to just get on with it,” (Respondent 57) and the support offered was “all lip service” (Respondent 115).

Medical staff were also criticized by a few for not offering more support. Respondents described how some doctors only reviewed patients remotely or, if they visited during the ward round, did not always physically review the patient. These left respondents feeling like they had to lead the care of the patients and make care decisions normally made by the medical team.

6.3. Equipment and environment

Supply of adequate PPE was considered problematic, particularly early in the pandemic. Many respondents commented that the lack of PPE and the threat of diminishing stocks caused great anxiety and stress, with one respondent reporting having to wear shower caps rather than theatre caps. Insufficient stocks of PPE also led to nurses not wanting to take their breaks so as not to have to doff and don and “waste” PPE. This left many nurses in PPE for extended periods of time without adequate meal and toilet breaks. Respondent 67 reported, “When you knew the PPE was getting low we didn't have a break as you just couldn't waste it”.

Caring for patients in unfamiliar environments such as in operating theatres and admissions units and placing additional beds in spaces designed to accommodate just one bed led to a range of reported challenges, highlighted by respondent 23, who said, “There was limited space in surge units especially in theatres and stuff you never knew where anything was”.

7. JOY OF CARE

Reflective of the 69% of respondents who reported being happy to work as part of the COVID‐19 ICU team, this theme describes the positive aspects of working in critical care during the pandemic and includes the sense of making a difference and the value of effective teamwork.

7.1. Making a difference

Many respondents reported valuing the feeling that they were making a difference. Some reported feeling a sense of pride and unity in making such a positive contribution to the pandemic efforts. Respondent 66 commented, “In the midst of chaos, feeling like I was actually doing something helped me.” Respondents derived great joy in caring for very sick patients and seeing them make a slow recovery and subsequently being discharged from critical care; “Seeing patients recover when they were so sick was really rewarding,” (Respondent 19).

7.2. Teamwork

Staff valued working as part of the multidisciplinary team. Respondents valued the comradeship, shared goals and effort. Respondent 25 commented, “The comradeship with my colleagues was amazing”. Respondents also reported a high level of support from their peers within the clinical team; “The team pulling together during the very difficult times” (Respondent 32).

8. COSTS OF CARE

This theme describes some of the negative aspects of caring both from a personal point of view in terms of well‐being but also from the broader perspective in terms of quality of patient care, and death and end of life care.

8.1. Quality of care

Many respondents reported delivering what they felt was substandard nursing care. Respondent 49 commented, “It's been very stressful feeling that you can't provide the 100% care to your multiple level 3 patients as we would in normal circumstances. You feel like you are giving substandard care and that's difficult to deal with knowing that you are trying your utmost to get the patients through the shift”. Many reported instances where key nursing priorities such as pressure area care, oral care and family care were neglected or de‐prioritized. Not being able to deliver the usual standard of care, caused respondents distress. Some reported feeling very sad and demotivated by not being able to give their all; “Not being able to provide adequate care to patients and not allowing visitors. This was awful and conflicted with my morals and personal values” (Respondent 56).

8.2. Death and end‐of‐life care

Respondents reported that the sheer volume of deaths, particularly in younger people caused them a great deal of distress. Caring for patients who were dying without the presence of the patient's family members was considered particularly upsetting. As respondent 106 stated, “What was upsetting was the covid pts dying so quickly especially younger ones, without even their family there.” Many also commented that they felt the quality of end‐of‐life care was compromised due to the lack of family presence.

Respondents also commented that the high volume of deaths was particularly upsetting as they felt the situation was avoidable. Some respondents recounted feeling angry towards the government and members of the public who were breaking the rules and not socially distancing or wearing masks, with respondent 183 lamenting, “it is me that has to hold the hand of a young person dying alone…”.

8.3. Personal well‐being

Participants reported high levels of stress and anxiety, accompanied in some cases by sleep disturbances. Respondent 28 described, “My mental health really suffered ‐ nightmares, stress induced alopecia, so anxious”. Respondent 72 simply stated, “The emotional labour has been tough”, whilst others pointed out how traumatized they felt by the events; “I have psychological trauma” (Respondent 72). Respondent 102 also pointed out how the trauma was similar to that experienced in war zones: “Being ex‐forces and having worked in war zones before helped me cope. I think that really helped as looking at others they were not coping at all they were really traumatised”.

Respondents described how friends, family and their fellow colleagues helped them cope. Some also mentioned accessing formal sources of support such as a critical care psychologist or counselling services provided by their employer. Others mentioned that “check‐ins” with the senior team or hot de‐briefs were helpful in supporting their well‐being.

9. DISCUSSION

The purpose of this survey was to understand experiences of and satisfaction with critical care nurse's role during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Both the quantitative and qualitative data clearly highlight the rewards and challenges of working in critical care. Key findings were that critical care nurses derived great satisfaction from making a difference during this global crisis and greatly valued teamwork and support from senior nurses. However, nurses consistently expressed concern over the quality of safe patient care, which they perceived to be suboptimal due to staff shortages and a dilution of the specialist skill mix. Together with the high volume of patient deaths, critical care nurses reported that these stressors influenced their personal well‐being.

Staff shortages and increased workload during the pandemic were reported as particularly problematic. Nurse‐to‐patient ratios in critical care have historically been significantly lower (1:1 or 1:2) than other clinical areas, reflecting the complexity and acuity of the work. 4 The volume and severity of illness in patients with COVID‐19 meant that the requirement for critical care beds increased exponentially and at great pace. This created a significant workforce shortage causing dilution of critical care nurses in terms of numbers and level of skill mix. 19 Respondents in this study linked the subsequent severely increased nurse‐to‐patient ratios and overall workload to an inability to deliver safe and high‐quality care, resulting in fundamental nursing care being neglected.

The full impact of the increased nurse workload during the pandemic on patient outcomes is yet to emerge, however, Griffiths et al.'s 20 systematic review reported reduced registered nurse staffing and higher workloads frequently leading to missed nursing care and reduced patient safety, reflecting the findings of this study. Lucchini et al. 21 reported a 33% increase in workload measured using the Nursing Activity Score (NAS), from a pre‐pandemic mean norm of 63 to a mean of 84, during the pandemic. A NAS greater than 61 is reported to increase the risk of patient mortality. 21 Reports emerging from the United States also suggest an increase in the number of hospital‐acquired pressure injuries, a nurse sensitive patient safety measure, in patients hospitalized during the pandemic. 22 As further substantive patient outcome data emerges, critical care nurses' concerns about the inability to deliver of high‐quality, safe patient care cannot be ignored and diluting staff skill mix and increasing nurse‐to‐patient ratios is not a sustainable option.

Critical care nurses in this study reported feeling “unsafe” at work. Reasons for this were multi‐factorial, with a lack of PPE, the uncertainty of the journey ahead and the volume of death witnessed daily being key influencing factors. Respondents reported significant mental health and well‐being sequalae, a finding consistent with the wider literature. 6 , 7 , 8 Although COVID‐19 was firstly considered as a physical health crisis, the United Nations 23 pointed out its potential to also become a major mental health crisis. Evidence of this is clear from our findings and the wider published literature.

Team working and camaraderie during the pandemic were reported as largely positive experiences. Critical care nurses in this study felt that, not only had they made a demonstrable difference, but that their role was better understood and valued by colleagues, a finding echoed in other studies. 24 , 25 However, some respondents also reported feeling neglected and undervalued; treated as a commodity with little perceived visibility or support from senior clinical nursing colleagues.

These findings may have ramifications on levels of occupational burnout and staff retention and highlight concerns that highly skilled critical care nurses may leave the speciality and indeed the nursing professional altogether. A systematic review of the literature reported a substantial prevalence of burnout amongst staff working in ICU during the pandemic (range 49.3%–58%) with nurses being at most risk. 26 In addition, the 2021 McKinsey Future of Work in Nursing Survey, 27 reported 22% (n = 400) nurses may leave frontline nursing in the next 12 months citing the strain of COVID‐19 as the key reason.

10. LIMITATIONS

There are several limitations of this study. We only recruited from the population of BACCN members, which may not be representative of the general critical care nurse population especially given the poor response rate. Furthermore, e‐survey data may not reflect practice reality. 14 There may also be a response bias where only those with very positive or very negative experiences responded. This may be especially true for those who were motivated to provide lengthy responses to the open‐ended questions, which may have skewed the results. The e‐survey tool only had face and content validity established prior to its use. This allowed us to expedite the start of this timely study, however, more extensive validation of the tool would have been advantageous.

11. IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE AND RESEARCH

High‐quality mental health is important for the functioning of society under “normal” circumstances, and must therefore be considered as part of the recovery from this pandemic, from both a service delivery and research perspective. In addition to focusing on the clinical nurses, critical care nurse managers will also bear the brunt of the effects of high levels of staff burnout. It is imperative that managers are also provided with adequate resources to mitigate these risks and deal with the unavoidable nursing staff turnover.

The United Nations 23 suggested that mental health support should be made available for all frontline health care workers, a recommendation implemented by many hospitals across the World. Despite the plethora of resources available to the respondents of this survey, the toll on physical and psychological well‐being remains. Further research is needed to identify which resources are most beneficial for whom and under what circumstances. There is also a clear need to co‐ordinate the wide range of currently available resources and to signpost critical care nurses and managers to those most relevant to individual needs. Resources should also be quality assured to avoid poorly designed resources negatively affecting well‐being.

Our findings highlight that further attention to what an appropriate future critical care workforce configuration looks like is also required. The context of critical care is undergoing significant change and during the height of the pandemic, the benefits and challenges of working differently, as a broader multi‐professional team, were realized. As noted by Endacott et al., 28 to ensure patient safety and optimize the retention of critical care nurses, future changes that impact on the role of critical care nursing must be co‐designed and evaluated considering patient, family and staff outcomes.

12. CONCLUSIONS

This study has highlighted that critical care nurses were happy to be part of the COVID‐19 response and felt they made a difference to the pandemic response. Critical care nurses greatly appreciated the teamwork and peer support, however, there were variable reports of support from senior staff. Concerns were raised about the quality and the safety of care provided. Study participants also described how stresses such as shortages of skilled staff, increased workload, supporting redeployed staff, the moral distress of not delivering what was perceived to be good quality care and the great exposure to death and dying influenced their personal well‐being. Health care leaders must consider these insights when managing the response to the demands and challenges of the ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic. COVID‐19 is unpredictable in its course, and what future variants might mean in terms of transmissibility, severity and resultant pressures to critical care remains unknown. It is evident that increasing the workload of critical care nurses by increasing nurse: patient ratios is not sustainable in the long term without an unacceptable compromise on the quality of care and patient safety and the well‐being of critical care nurses. Future responses to the challenges that critical care faces must consider nurses' experiences and create an environment that engenders supportive teamwork, facilitates excellent nursing practice and effective safe patient care where critical care nursing may thrive.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding was received to conduct this study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interest disclosed.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Necessary approvals were granted from the executive board of the British Association of Critical Care Nurses.

Supporting information

Data S1 Supporting information.

Stayt LC, Bench S, Credland N, Plowright C. Learning from COVID‐19: Cross‐sectional e‐survey of critical care nurses' satisfaction and experiences of their role in the pandemic response across the United Kingdom . Nurs Crit Care. 2022;1‐9. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12850

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hetland B, Lindroth H, Guttormson J, Chlan LL. The year that needed the nurse: considerations for critical care nursing research and practice emerging in the midst of COVID‐19. Heart Lung J Acute Crtic Care. 2020;49:342‐343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organization . COVID‐19: Occupational health and safety for health workers Interim guidance [Internet]. Geneva; 2021 Feb. Accessed April 19, 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-HCW_advice-2021-1.

- 3. Turale S, Meechamnan C, Kunaviktikul W. Challenging times: ethics, nursing and the COVID‐19 pandemic. Int Nurs Rev. 2020;67(2):164‐167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine. Guidelines for the Provision of Intensive Care Services (GPICS 2) Intensive Care Medicine. 2019.

- 5. National Health Service . Coronavirus: principles for increasing the nursing workforce in response to exceptional increased demand in adult critical care [Internet] 2020. Accessed April 19, 2022. Available from: www.nmc.org.uk/news/coronavirus/how-we-will-regulate.

- 6. Leng M, Wei L, Shi X, et al. Mental distress and influencing factors in nurses caring for patients with COVID‐19. Nurs Crit Care. 2021;26(2):94‐101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Denning M, Goh ET, Tan B, et al. Determinants of burnout and other aspects of psychological well‐being in healthcare workers during the Covid‐19 pandemic: a multinational cross‐sectional study. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0238666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Şanlıtürk D. Perceived and sources of occupational stress in intensive care nurses during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Intens Critic Care Nurs. 2021;67:103107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bruyneel A, Smith P, Tack J, Pirson M. Prevalence of burnout risk and factors associated with burnout risk among ICU nurses during the COVID‐19 outbreak in French speaking Belgium. Intens Critic Care Nurs. 2021;65:103059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. González‐Gil MT, González‐Blázquez C, Parro‐Moreno AI, et al. Nurses' perceptions and demands regarding COVID‐19 care delivery in critical care units and hospital emergency services. Intens Critic Care Nurs. 2021;62:102966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sharif Nia H, Arslan G, Naghavi N, et al. A model of nurses' intention to care of patients with COVID‐19: mediating roles of job satisfaction and organisational commitment. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(11):1684‐1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goh YS, Ow Yong QYJ, Chen THM, Ho SHC, Chee YIC, Chee TT. The impact of COVID‐19 on nurses working in a university health system in Singapore: a qualitative descriptive study. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(3):643‐652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pagnucci N, Scateni M, de Feo N, et al. The effects of the reorganisation of an intensive care unit due to COVID‐19 on nurses' wellbeing: an observational cross‐sectional study. Intens Critic Care Nurs. 2021;67:103093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Latour JM, Tume LN. How to do and report survey studies robustly: a helpful mnemonic SURVEY. Nurs Crit Care. 2021;26(5):313‐314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E‐surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34. doi: 10.2196/jmir.6.3.e34. Erratum in: doi: 10.2196/jmir.2042. PMID: 15471760; PMCID: PMC1550605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. BACCN (2022). Membership Report. Accessed March 19, 2022. Available at https://www.baccn.org/members/board-resources/march-board-meeting-2022/.

- 17. Papapavlou L, Teixeira J, Dorman B, Nichols J, Bench S. Learning from COVID‐19; a survey exploring nurses' and ODPs' views of caring for general intensive care patients at an elective orthopaedic hospital. Nurs Critic Care. 2021;26(S1):11‐37. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12693?af=R [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77‐101. [Google Scholar]

- 19. UK critical care nursing Alliance . UKCCNA position statement: nurse staffing during COVID‐19 [internet]. London; 2021. [cited 2022 Apr 11]. Accessed March 19, 2022. Available from: https://www.ics.ac.uk/Society/Policy_and_Communications/Articles/Updated_UKCCNA_position_statement.

- 20. Griffiths P, Recio‐Saucedo A, Dall'Ora C, et al. The association between nurse staffing and omissions in nursing care: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2018;74:1474‐1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lucchini A, Iozzo P, Bambi S. Nursing workload in the COVID‐19 era. Intens Critic Care Nurs. 2020;61:61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Polancich S, Hall AG, Miltner R, et al. Learning during crisis: the impact of COVID‐19 on hospital‐acquired pressure injury incidence. J Healthc Qual. 2021;43(3):137‐144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. United Nations . Policy Brief: Covid −19 and the Need for Action on Mental Health. 2020. Accessed March 19, 2022. Available form: https://www.un.org/sites/un2.un.org/files/un_policy_brief-covid_and_mental_health_final.pdf.

- 24. Chen R, Sun C, Chen JJ, et al. A large‐scale survey on trauma, burnout, and posttraumatic growth among nurses during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2021;30(1):102‐116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guttormson JL, Calkin K, McAndrew N, Fitzgerald J, Losurdo H, Loonsfoot D. Critical care Nurses' experiences during the COVID‐19 pandemic: a US National Survey. Am J Crit Care. 2022;31(2):96‐103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gualano MR, Sinigaglia T, Lo Moro G, et al. The burden of burnout among healthcare professionals of intensive care units and emergency departments during the covid‐19 pandemic: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Publ Health. MDPI. 2021;18(15):8172. doi:10.3390/ijerph18158172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berlin G, Lapointe M, Murphy M, Viscardi M. Nursing in 2021: retaining the healthcare workforce when we need it most. McKinsey & Company; 2021. Accessed March 19, 2022. [Internet]. 2021 Available from: www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/nursing-in-2021-retaining-the-healthcare-workforce-when-we-need-it-most [Google Scholar]

- 28. Endacott R, Pearce S, Rae P, et al. How COVID‐19 has affected staffing models in intensive care: a qualitative study examining alternative staffing models (SEISMIC). J Adv Nurs. 2021;00:1‐14. doi: 10.1111/jan.15081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1 Supporting information.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.