Abstract

The coronavirus pandemic (COVID‐19) had detrimental health and economic impacts on communities across the globe. Consequently, public, profit and nonprofit organizations had to quickly adjust to the new situation and adopt new operating strategies and service delivery mechanisms. This study examines a nonprofit food network in Virginia and the impact of COVID‐19 on food bank services and distribution operations. Guided by the adaptive systems approach, this case study utilizes the Federation of Virginia Food Bank (FVFB) and focuses on operational challenges within the network and the impact of the CARES Act. The data obtained from stakeholder interviews and a survey of local and regional providers suggest communication and adaptive management were crucial in the continuation of network operations. Furthermore, understanding the multifaceted needs of vulnerable individuals, beyond nutrition and food insecurity, is important for nonprofit service partners in a network. The study proposes a conceptual framework for effective operations in a nonprofit network during crisis and highlights the need to create collaborative capacity.

Keywords: adaptive management, COVID‐19, nonprofit food network, operational challenges

1. INTRODUCTION

The novel coronavirus pandemic (COVID‐19) detrimentally impacted the economy and community health of the United States, impacting organizations of all types. Nonprofit organizations, which are pivotal in providing services for vulnerable populations, are particularly susceptible to health and human crises like the COVID‐19 pandemic (Center for Disease Control [CDC], 2020; Hu et al., 2014; Kapucu, 2006, 2007; Kapucu et al., 2011). In the wake of COVID‐19, nonprofits in United States had to quickly adjust their operations to the new challenges brought by the pandemic and its cascading impacts. The nonprofit sector adapted its day‐to‐day operations to follow social distancing and health and safety guidelines provided by the CDC, World Health Organization (WHO), and the regulations of their respective state and local governments. However, challenges expanded beyond adapting to CDC health and safety guidelines for front‐line, service‐oriented 501(c)(3) organizations that provide critical services like food and nutrition programs during crises. These include shortfalls in donations and resource availability, volatile job markets, partner agencies shutting down, decreasing volunteer numbers, and disruptions in supply chains, which increased supply costs impacting the ability to deliver services and threatened their sustainability (Johnson et al., 2020; Kulish, 2020; Organization for Economic Co‐operation and Development [OECD], 2020). These challenges were amplified because of the increased need for programs and services (Deitrick et al., 2020; Kim & Mason, 2020).

As the world enters the third year of the global pandemic, it is evident we have learned more about preventive strategies, effective immunization, and treatment. What we have not adequately explored is the impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on the operations of nonprofit organizations. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to examine the impact of COVID‐19 on the operations of a statewide food service nonprofit network and examine operational challenges a large‐scale crisis caused within this network. More specifically, this study seeks to examine activities performed by different nonprofit organizations that work together with other government and for‐profit agencies to fulfill a similar mission. These operational activities include planning, monitoring, and managing service delivery during the COVID‐19 crisis. The study focuses on the Federation of Virginia Food Banks (FVFB), which supports seven regional food banks and is the largest hunger relief network in the Commonwealth (FVFB, 2022). The network has roughly 1560 agency partners and serves around 1 million people annually, making the inquiry into the operation of this network noteworthy.

The research questions of the study are threefold: (1) How did COVID‐19 pandemic impact the operations of food banks within a statewide network? (2) What challenges has COVID‐19 presented to food networks? And (3) Has federal legislation impacted immediate operations in statewide food bank networks? To examine these questions, we used qualitative analysis of information obtained from website analysis, interviews with key stakeholders, statewide survey of local and regional providers, and interviews with partner agencies in a network.

The manuscript is organized as follows. We first review the available information on the impact of COVID‐19 pandemic on food service nonprofits and then proceed with reviewing the empirical literature on nonprofit operations during crisis, governance systems, and adaptive systems and management. Literature on nonprofit governance systems during crisis and adaptive systems and management is relevant in exploring how specific nonprofit organizations and their networks can survive uncertainty (Mosley et al., 2012; Searing et al., 2021). Then the study proceeds with providing background information on the FVFB network and methods of the study. Later, we present results from interviews and a statewide survey. The study concludes with identification of operational challenges for nonprofits and provides practical advice for better response in a future crisis.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

This section of the paper discusses what is known regarding COVID‐19 impacts to food‐oriented nonprofits and the impact of federal legislation, which is relevant for exploring a specific nonprofit food network operations during COVID‐19. This section then investigates literature on governance and operations during crisis and adaptive systems and management relevant to understanding crisis management and nonprofit resiliency. These works provide insight for investigation into governance and communication operations of Virginia's statewide food network.

2.1. COVID‐19 impacts to food service nonprofits

Food banks, or organizations that collect and distribute food to other agencies like food pantries, soup kitchens, and shelters, had to adapt quickly to the pandemic environment and its residual impact. A collaborative survey by Reuters and Charity Navigator found 75% of food banks were affected by the pandemic (Dowdell & Lesser, 2020). This impact is felt by numerous partner agencies as food banks typically distribute more than 70% of their food through local food pantries (Abou‐Sabe et al., 2020). More than half of the food bank nonprofits surveyed by Charity Navigator reduced their programs due to limited availability of volunteers and food supply to meet the increased demand (Dowdell & Lesser, 2020). Although food banks rely on donations for food supplies, the closure of partner organizations, like restaurants, casinos, and hotels, cut off a critical supply source. As a result, nonprofits shifted to purchasing most of their supplies directly, which significantly increased their costs. For example, Feeding America, the largest network of food banks in the United States, projected a shortfall of $1.4 billion within the first few months of the pandemic (Kulish, 2020). The Food Bank for the Heartland in Omaha, a prominent food bank nonprofit in Nebraska that works with over 500 partner agencies, increased its monthly spending on food purchases from $73,000 to $675,000 (Feeding America, 2022; Kulish, 2020). Organizations like Northwest Harvest, a nonprofit organization within Washington state that supports a food network with food banks, meal programs, and needy schools, stated the pandemic increased the need for food assistance from 800,000 to 1.6 million meals, placing immense pressure on food banks (Kulish, 2020). Some estimates are that food insecurity rate jumped from 11%–12% to 38% during 2020 (Wolfson & Leung, 2020). However, the full impact of food insecurity during COVID‐19 is still unknown (Leddy et al., 2020).

Nonprofit organizations also faced challenges associated with the loss of volunteers (Shi et al., 2020). Elderly individuals make up a significant number of volunteers for food banks and the risk of contracting the virus led many to pause or cease their services. Many food banks, as evidenced by the Greater Pittsburgh Community Food Bank, made an appeal for government assistance to offer the National Guard as help in conducting activities, such as packaging and distributing food boxes (Abou‐Sabe et al., 2020). Relying on non‐traditional means of food preparation and government support continue to be important adaptations by food‐serving nonprofits in addressing the increased need caused by the pandemic.

Food banks also responded to the guidelines for reduced contact between individuals (low touch, no touch) and enhanced social distancing. Some organizations shifted to pre‐packaging their groceries as opposed to letting clients pick the groceries or low‐contact drive‐through food distribution centers so consumers could pick up pre‐packaged and boxed non‐perishable foods (Abou‐Sabe et al., 2020; Alam, 2020). Other organizations, such as the City Harvest, introduced mobile markets to transport products closer to their constituents and allowed them to pick up food on foot (Abou‐Sabe et al., 2020). The South Milwaukee Human Concerns organization, a nonprofit with a mission to deliver critical needs to residents through food, clothing, and other essential services, used a model to take orders online and deliver packed goods to the clients via curbside pickup (Meiksins & Jarrin, 2020; South Milwaukee Human Concerns, 2022), like grocery delivery service apps. Other novel operational changes included providing take‐home meals and meal packages from traditional dine‐in services. The change in food distribution is another major adaptation strategy adopted by food banks to ensure both the workers and the clients are protected from exposure and contacts that increase the risk of coronavirus infection.

2.2. Impact of Federal Legislation (CARES act) to nonprofit organizations

To assist in recovery from the pandemic, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES Act) was signed into law in 2020 containing health‐related provisions to curb the virus outbreak in the United States. The $2.2 trillion economic stimulus bill was passed by Congress and signed into law by President Trump as a response to COVID‐19. Some of the provisions within the CARES Act included paid sick leave for employees, insurance coverage for COVID‐19 testing, nutrition assistance, and provisions to assist nonprofits, among other programs. The Paycheck Protection Program was one way the CARES Act helped nonprofits. This program allowed loans for tax‐exempt nonprofits to cover some of their payroll costs. In addition, the CARES Act offered economic injury disaster loans with interests at 2.75% or grants of $10,000, with payment deferral options. Employee reimbursements, payroll tax credits, and industry stabilization funds could also benefit nonprofits. Some of these loans were fully or partially forgivable. The American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) was adopted in 2021 and offered additional support to nonprofits with over 500 employees in the paycheck protection program. However, many of the efforts in the Cares Act and ARPA did not help with urgent community needs due to lengthy application processes, little communication on application statuses, and a lack of guidance on support (Azevedo et al., 2021).

2.3. Governance and operations during crisis

All of the challenges experienced during COVID‐19, like other large‐scale crises, demand robust governance and leadership particularly when they are happening in turbulent social environments characterized by globalization, new technology, political divides, and mediatized communication (Ansell et al., 2021; Ansell & Trondal, 2018; Noor et al., 2021). More specifically, nonprofits are required to have adaptive and flexible leadership structures to strategically adjust operations and programs, adopt new technology and tap into various capacities, reexamine their crisis leadership teams and communication strategies, and revisit their budgets to improve the likelihood of their survival. Robust governance strategies, defined by Ansell et al. (2021), is “the ability of one or more decision makers to uphold or realize a public agenda, function, or value in the face of the challenge and stress from turbulent events and process through the flexible adaptation, agile modification, and pragmatic redirection of governance solutions” (p. 952). This definition suggests organizational governance can respond flexibly and impact policies and practices to meet current conditions. Research on robust governance during turbulence and crisis is emerging in the public and nonprofit sectors, but clearly implies organizations with contingent configurations may navigate crisis like the COVID‐19 pandemic more effectively (McMullin & Raggo, 2020).

Preliminary data from after the initial COVID‐19 onset also proposes nonprofits with financial capacity, or specifically operating reserves, were able to initially manage challenges better when compared to those without. This hinders on the need for developing financial reserves and investing in financial capacity (Kim & Mason, 2020). Partnerships, collaborations, and networks among nonprofits are essential during crisis, especially when there is a limit on financial capacity and a great need to provide critical resources such as food distribution, sheltering, relief funding, family reunification services, and more. Collaborative capacity can also assist organizations in building their financial capacity. Collaborative capacity consists of the conditions needed for effective collaboration in partnerships that lead to community change (Goodman et al., 1998). Hocevar et al. (2006) note collaboration during crises requires teams to create novel and adaptive processes, systems, and protocols to account for hostile, complex, or uncertain events. Clear communication between partners and organizational stakeholders, like the public, is vital during crises when resources are limited and time is essential. Operational shifts require nonprofits to adopt new strategies for collaborating and communicating with their partners and service community. Increased communication allows for the development and exchange of best practices for operations, as well as the unification of voices to give them a stronger influence to lobby for state and federal assistance (Garcia, 2020).

2.4. Adaptive systems and management

Robust nonprofit governance during crises requires adaptive systems and management. Complex adaptive systems are a dynamic framework required for understanding management of extreme events and provides insight for management utilizing adaptive processes (Comfort et al., 2012). Adaptive management is an important strategy within a system aiding food banks in navigating the COVID‐19 crisis and is worthy of closer examination to establish better practices for service‐oriented nonprofits experiencing crisis. Adaptive management surfaced in response to various fragmented institutional arrangements that lead to disintegrated regulation and response, requiring a “learning by doing” approach. It is a formal, deliberate, structured, and systematic process with a key aspect focused on continual learning when faced with uncertainty and change (Antonovici, 2015). Adaptive management requires inclusion of governance, communication, planning, decision implementation, and evaluation of outcomes in the process. These encompass an iterative co‐learning environment among leadership and stakeholders (Kingsford et al., 2017).

Key within adaptive management are stakeholders and their agreement on vision within the system and working closely with stakeholders to meet shared goals (Conallin et al., 2017). In the FVFB, main stakeholder groups are the varying partner agencies in the network, community members including those receiving food and nutrition programs and supplies, and funding partners, such as the government. Collaboration can improve network performance using critical external resources and is vital during crisis, when decisions are made quickly and made in an adaptive system (Ansell & Trondal, 2018; Moynihan, 2009). Communicating with stakeholders during crisis also requires strategic crisis communication, or carefully chosen words and actions which manage information through the crisis situation (Coombs & Holladay, 2011). Communication is an important interface function in a network throughout a crisis (Hyvärinen & Vos, 2015). In the case of FVFB, analyzing communication is required to understand operations during the pandemic onset.

3. STUDY CONTEXT

Utilizing a case study approach, this study focuses on the Federation of Virginia Food Banks (FVFB). The FVFB is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit state association of food banks affiliated with Feeding America and is the largest hunger‐relief network in Virginia. The Federation supports the seven regional Virginia/Washington D.C. food banks in creating partnerships, acquiring resources, sharing data, and raising awareness of food insecurity. At the time of this study, the seven‐member food banks had approximately 1560 local partner agencies with the mission is to grow the collective capacity of Virginia's food banks and engage partners to end hunger in the Commonwealth (FVFB, 2021). The network can be defined as goal‐directed, meaning they exist for a specific purpose and are a formal mechanism for collective action requiring multi‐organizational outcomes (Agranoff & McGuire, 2003; Kilduff & Tsai, 2003; Provan & Milward, 1995; Provan & Kenis, 2008).

In 2019, the Federation's network distributed almost 118 million pounds of food and grocery products through member agencies that directly serve those in need. These agencies operate programs such as soup kitchens, afterschool programs, senior centers, elderly feeding programs, Head Start (a federal school readiness program for low‐income families), transitional housing, mental health programs, homeless and domestic violence shelters, and individual household distribution (FVFB, 2021). Since the Spring of 2020, the network has been on the front lines of service delivery, serving people in unimaginable conditions, amid a food shortage and a 50‐year high for grocery prices. Across Virginia alone, food banks were purchasing at least twice as much food as they did in December 2020, compared to the same time in 2019 (FVFB, 2021).

4. METHODOLOGY

This study takes an inductive; qualitative approach and was conducted in two steps. In the first step, we reviewed the websites of FVFB member organizations and conducted interviews with FVFB regional leaders. In the second step, we administered an online survey to partner agencies. Regarding the review of websites, the study focused on organizations involved in the network and articles from prominent news sources where we searched for terms “FVFB,” “COVID‐19,” “operational challenges,” and “communications,” to search for relevant information on the FVFB operation during COVID‐19. This included messages from organizations to stakeholders (such as blogs, social media, and published online newsletters) on operations and messages from network leaders to partner agencies on resources and partner work. To getter better and more detailed ideas on the communication and operational challenges during COVID‐19 and the impact of CARES Act, we conducted confidential in‐depth, semi‐structured interviews with three of the seven FVFB regional leaders and the FVFB executive director. Due to this exploratory study, the questions for the interviews were broadly focused on the overall impact of the pandemic along with specific impact to communication and coordination within the FVFB network and the Commonwealth of Virginia (see Appendix A). All interviews were either conducted via phone or Zoom, a teleconference software, based on the interviewees comfort level. Each interview lasted approximately 60 minutes and were transcribed.

Utilizing literature on adaptive systems, information on nonprofit pandemic response, as well as initial interview findings, a survey was created for agencies within the network. For question creation, we used information collected from interviews and FVFB websites, blog posts, and the literature review. The survey included Likert‐style questions and open‐ended questions regarding the organization, its collaboration with partner agencies, information gathering, the impact of COVID‐19 to the organization, collaborative capacity, and personal demographics. The survey was supported by FVFB leadership and distributed directly to the seven regional agencies through email by the FVFB leadership. The regional agencies were then asked to send out the survey to their partner agencies in the entire network. In total, there are approximately 1560 partner agencies. This number is an approximate due to COVID‐19's impact on operations, some food banks experienced closures and some pop‐up organizations surfaced. Survey responses were received from 57 agencies for a response rate of 3.6%. A low response rate, in this case, was attributed to COVID‐19 disruptions and closures, organizations being overwhelmed with providing services, as well as the nature of some of the partners being temporary or occasional operating organizations. The survey captured rich information pertaining to network operations from respondents representing different organizations within this network during a crisis and therefore is capable of extrapolating useful lessons for network partners and management.

5. FINDINGS

5.1. Interview findings

Semi‐structured interviews with FVFB leadership and regional leaders were transcribed and reviewed by two researchers and coded for common themes, following Ryan and Bernand's (Ryan & Bernard, 2003) technique for identifying themes in qualitative data: comparing grouping categories, finalizing categories, placing statements in categories, and developing sub‐categories. Five themes emerged and are described below.

5.1.1. Challenges pertaining to operations management

The first emergent theme was challenges in operations management of partner agencies. Often operational changes occurred overnight without time to plan for changes in coordination within the organization or the network. For example, regional offices had to process unexpected challenges of food bank closures among various regular partners along with limited food or cut scheduling and programming. A lack of a robust governance structure among many of these organizations became apparent. Additional operational challenge included a lack of volunteers showing up due to concern over the virus. The following are comments that speak to this theme:

The pandemic has added a complexity [to service delivery] that no one could have anticipated. Each food bank is unique… Volunteers at other food banks are older and that impacted their ability to manage and keep open the food banks during this time. (Respondent, A)

We can't email out the food… and the changes happened overnight. We encouraged our partners to close the doors, but open the parking lots, do drive‐thru…and that is the safest way. Some partners have been able to adapt to a version of a client‐choice model that brings people inside and is much [more] limited. Keeping partners safe and the safety of the folks first and foremost [is most important]. (Respondent, B)

The immediate concern was [partner] agency closures… the community organizations that we partner with to supply food assistance are pantries, but some shelters or food kitchens are considered agencies as well. As a state we were lucky that there were relatively few closures, northern agencies had the most closures. The peninsula food bank had relatively high number, like 30%, due to different challenges and barriers… In VA, we are proud of the way our networks held up and the tremendously long lines of cars compared to other parts of the country. (Respondent, C)

5.1.2. Importance of technology

The use of technology‐assisted the regional offices and FVFB network with many communication challenges related to changes in programming, health and safety guidelines, and closures, and was a prominent theme throughout the interviews. However, word of mouth was still the most valuable communication mechanism for working externally with communities. Many in the service population did, and still do, not have access to technology. Therefore, older and more established forms of communication still had to be used. This theme is seen in the following interview comments:

Word of mouth is still one of the biggest [methods used for information sharing] for notes on the door regarding food drives. We post on media and social media sources, but never underestimate the value of different networks and we share it with folks that come through the door. (Respondent A)

Mostly technology has assisted [with communication and agency feedback]. Some of the agencies use Services Insight to report numbers and we can immediately pull data from that to see their numbers. Newsletters are electronic and on the website. Early on there was good and consistent pulses out to the network of foodbanks to see where folks are at. (Respondent, B)

The biggest hurdles are those clients that have no computers or access to technology. We'll never turn anyone away. Someone can register on‐site with someone to guide them. A lot of folks do have smart phones and that can be something to rely on too during this time. It is web based so nothing to download and smartphone streamlined. We want to bring back a level of choice and dignity to the process. Not quite as specific as an Instacart, but there is a level of choice of what to bring into the household. (Respondent, A)

5.1.3. Importance of communication alignment

Respondents noted the importance of frequent communication and aligning messages across local, regional, and state offices. The state government response established a state feeding task force, which worked with the network. The task force helped to provide continuity of messaging across different levels and supported the network. In addition, nonprofits worked to cross check messages that were being put out with other well‐known networks and organizations, like Feeding America. This is seen in the following comments:

State government response established a state feeding task force. They've been in communication with state agency officials and the nonprofit community and what the challenges were and what was needed. As a result, we've received an influx of MREs through FEMA. (Respondent, C)

Communication [is] at an all‐time high. We are hearing from federal level offices almost weekly. We always make sure our message is aligned with Feeding America and the national network and the Virginia federal of food banks before signing on to a request. [Representatives] are doing a lot of fact‐checking and making sure that message stays clear. Virginia legislators are extremely active and… just passed a food investment initiative that provide incentives that provides structure in food desserts. (Respondent, A)

5.1.4. Understanding of diverse community needs and current environment

It was clear through the interviews and online communication that nonprofits within this service population are often addressing several needs, and often one need is compounded by others. Vulnerable people in the network's service population often have needs beyond nutrition and food security programs. Interviews suggested a focus on a more comprehensive view of needs for the economically distressed during crisis, and a hope that legislative movement could assist with the various needs and social and political environment during this time. These needs are critical for organizations within the network to address. This is seen in the following comments:

COVID has put a spotlight on the degree to which charitable service is fragmented in terms of both within the nonprofit sector and across the public and private sectors. People who are vulnerable to economic distress have multiple needs, it's never just one thing. It has felt like an extraordinary effort to coordinate across state agencies and the private sector just on nutrition programs and food security alone‐ so how we take a more comprehensive view of that, for some of these other needs, is something that needs to be examined. (Respondent, C)

We've seen an increase of legislation to get the minimum wage up to $13 per hour. There is a lot of legislative activity and the General Assembly is back in session. Primarily they've been dealing with social issues like community policing. This is the time to capitalize on the mindset. [An agency representative] has done a couple blogs and highlighted the impact of COVID and the pandemic. Racial disparities is one area that is forthcoming. (Respondent, A)

Because of the social and political climate during COVID‐19, many issues became politicized and constituents fell on one side or the other instead of coming together to reach a quick consensus on stimulus funding and advocacy, food bank closures, and other health and safety guidelines. Even though interviews revealed partisan issues within the network, it seems partners could come to agreement on the importance of nutrition programs for their communities. This is seen in the following comment:

There is a volatile political climate, and everything has turned into a partisan issue… but we all want the same thing. We want our families to be safe and healthy and we want our children to thrive and our elderly to be healthy. And we want access to nutrition information to help build community health. (Respondent, A)

5.1.5. Federal aid impacted network providers differently

The CARES Act impacted assistance provided to the food packaging program, of which access and information varied across partner agencies. The interviewees that brought this up noted the federal assistance was beneficial to certain programs, although it took time for the impact to trickle through to the community.

The CARES Act has also assisted in helping with a food packing program as well to help bring in shelf‐stable food and get out in front of that purchasing. It took two months in the beginning to get the order and receive the food and then it was down to distributing it. (Respondent, B)

5.2. Survey findings

In terms of survey results, the majority of responding agencies identified to be representatives of a food pantry within the network, followed by a partner agency of a food pantry/bank, or food bank (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Organizations represented in survey

| Organization type | Budget size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | ||

| Food bank | 9 | 15.8 | $0–$100,000 | 36 | 65.5 |

| Food pantry | 30 | 52.6 | 2 = $100,001–500,000 | 3 | 5.5 |

| Partner agency of a food bank/food pantry | 13 | 22.8 | 3 = $500,001–$1,000,000 | 4 | 7.3 |

| Other (social service providers, homeless shelters, financial assistance organizations, etc.) | 5 | 8.8 | 4 = $1,000,001–$5,000,000 | 7 | 12.7 |

| Total | 57 | 100 | 5 = $5,000,001+ | 4 | 7.3 |

| 6 = Unsure | 1 | 1.8 | |||

| Total | 55 | 100.1 | |||

In terms of the organizations represented in the survey, the majority were very small, with budgets between 0‐$100,000 for the current fiscal year (2020) (see Table 1) with no full‐time or part‐time staff and heavily reliant on volunteers (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Number of staff and volunteers in organizations represented in survey

| # of part‐time staff | # of full time staff | # of volunteers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 0 | 35 | 62.5 | 34 | 61.8 | 0 | 0 |

| 1–5 | 16 | 28.6 | 9 | 16.4 | 10 | 17.9 |

| 6–10 | 3 | 5.4 | 1 | 1.8 | 10 | 17.9 |

| 11–20 | 1 | 1.8 | 2 | 3.6 | 9 | 16.1 |

| 21–50 | 1 | 1.8 | 6 | 10.9 | 9 | 16.1 |

| Over 50 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 5.5 | 18 | 32.1 |

| Total | 56 | 100.1 | 55 | 100.0 | 56 | 100.1 |

Each question and response from the surveys were examined to extract themes from the qualitative questions within the survey, following the same steps as the interviews.

5.3. Challenges and opportunities presented by COVID‐19

In terms of the challenges and opportunities presented by COVID‐19 to the organization, open‐ended survey responses were grouped into the following themes: dwindling resources (including volunteers) and financial capacity while dealing with an upswing in demand, changes in operations related to pandemic protocols, new and strengthened opportunities for collaboration, and new opportunities for grants, donations, and other financial benefits. The following comments demonstrate the struggle with fewer resources and increased service demands:

With dwindling resources, we determined that we would distribute food to three populations at risk of food insecurity: seniors, children and low‐income families. Within a matter of days, food donations plummeted while our cost to provide a meal skyrocketed from $0.40 to $3.50 overnight. Fundraising events and campaigns were postponed or canceled. Along with a decrease in food and funds, we experienced a surge in need. Approximately 70% of our Partner Agencies were forced to temporarily close their doors to protect the health and well‐being of volunteers, many of whom are seniors. We partnered with three local nonprofit organizations to ensure consistent food access to the most vulnerable populations in our community.

We went from serving 120‐150 households over several shifts per week, to serving 400‐450 households in a day. It was very difficult to access enough food during the first months of the pandemic.

We had issues with getting factual information vs. political information. This itself has led to challenges with staffing. We are 100% Volunteer and lost many of our volunteers due to misinformation that fed a specific narrative.

Issues related to the pandemic and changes in health and safety guidelines also presented challenges to organizations within the network. These included pivoting to drive through or pickup models, providing outdoor food locations, and other outlets of food distribution, in addition to language barriers and serving culturally appropriate foods. Logistics for many of these organizations has also been challenging, showcasing the need for adaptive management during crisis. The following comments demonstrate this finding:

Our large church food pantry had to pivot from a client choice model to a drive‐thru, no‐contact pantry for the pandemic… We also had many cold storage challenges as we sought to serve more people.

Logistics of serving hot meals outside has been challenging. Staffing to protect both volunteers and guests has also been an issue.

Congregate living environment presented many challenges for our service population

In addition to funding, we experienced language barriers (99% of clients speak Spanish) and availability of culturally appropriate foods our clients can/will use.

New opportunities were presented for collaborations within and across the network. This included innovative opportunities for partnering for new service operations, increased partnerships that previously were less established, and working with more diverse groups to better meet the needs of constituents. The following comments demonstrate this finding:

Establishing new, unique community partners to assist in food distribution.

Opportunities have been presented for deepened relationship with existing partners, created new relationships with partners, and created collaboration across organizations within Counties.

Working with a more diverse groups of organizations has provided us with opportunities that we had not explored prior to COVID.

A final theme from challenges and opportunities presented from COVID‐19 was new opportunities for grants, donations, and other financial benefits. While many organizations struggled with losing volunteers and changing operations, many also noted new opportunities for resources including grants and other financial support. This is seen in the following comments:

We have received a few grants that have allowed us to purchase extra food along with expanding our shelving. We have also received a grant to purchase a new freezer. These were accomplished by a person in our church whose insurance company offered those grants along with local stores having grants that you could Apply for.

We've been able to help more clients during this pandemic, both with food and financial help due to financial resources available to us with grant opportunities and cost breaks due to the pandemic.

When asked about what challenges and opportunities were anticipated as the pandemic continues, participants stated an increase in individual needs of food assistance, further uncertainty, and concern over reduced funding. With many individuals still experiencing unemployment, participants expect to see an increase in individuals in need of food assistance, even as the number of COVID‐19 cases eventually decreases. In addition, although levels of giving have been unprecedented during the past year, there is no certainty that donors will continue supporting at these same levels. Many organizations expressed concern over being able to keep up with demand. In addition, organizations are torn over when and how to “return to normal” in terms of operating. Some organizations had overwhelmingly positive responses for drive up food pantries and other operations that responded to health and safety guidelines and hoped to continue this service long term. However, offering these services long‐term requires funding that these organizations are not guaranteed.

5.4. Communicating with regional and state representatives during COVID‐19

Most respondents noted no major impacts to communication with regional and state representatives through COVID‐19. Some stated there was closer contact and reliance on their regional and/or state partners because of the importance of information coming from these larger offices; however, a few respondents stated they felt left in the dark in terms of direction from the state. The following comments demonstrate these findings:

Many of us rely on our partner agencies for information to and from regional and state representatives. We have needed to stay more informed than ever to keep up with guidelines, restrictions and best practices, as these have drastically changed the methods in which we have distributed food into the community. It has also been critical for us to stay informed about various legislative acts that have benefited Virginia food banks.

Our food pantry communicates solely with a certain Food Bank. My contacts are extremely responsive, helpful, and friendly. They are the most important partner in our food pantry.

Regional communication has been excellent. We do not communicate on a state level with the work we do.

5.5. Technology presenting new challenges and opportunities for crisis communication

Survey respondents were asked about how technology presented new opportunities for communication during COVID‐19. Although the vast majority responded positively that technology provided new opportunities, few respondents noted challenges mostly related to lack of access to adequate technology within the organization or the lack of technology their service constituents had access to. These findings are seen in the following comments:

Technology has allowed us to get information out into our community quickly and effectively by posting updates weekly‐‐and sometimes daily‐‐on our website and social media channels, letting our community know pertinent updates about our COVID‐19 response, new distribution locations and practices.

We anticipate challenges with disseminating information because we have a lack of adequate technology at our organization. We need to build a website and it's challenging because we are not equipped with reliable internet or hardware.

Technology has presented challenges for aging food recipients and those who lack cell phones, WIFI or internet access. Again, our difficulty is communicating with our clients due to many not having access to the internet. We found a text messaging service to be the best method to communicate with our clients.

6. DISCUSSION

The COVID‐19 pandemic amplified issues of food insecurity and poverty. Nonprofits working to address food needs faced numerous challenges since the spread of the pandemic in the United States beginning in March 2020. Findings from both the open‐ended survey questions and interviews revealed similar themes in terms of how organizations throughout a food service nonprofit network operated through the COVID‐19 pandemic. In revisiting the first two research questions explored through the data, we find the pandemic significantly impacted nonprofits' operations within this food service network. Leaders within the network noted the challenges in operations management, particularly in working with agencies closing overnight, that impacted their collaborative capacity. It is important that collaborative capacity is continually assessed during crises so nonprofits can respond to new challenges and develop new competencies and solutions, based on the collaborative or network purpose. It appears the FVFB did manage to adapt to new processes and followed a “learning by doing” adaptive management approach, which included two‐way communication with different groups, planning, governance investment, in an iterative, co‐learning environment (Antonovici, 2015; Kingsford et al., 2017). Yet the challenges revealed within and throughout the network inhibited the success of some organizations and caused others to creatively build their capacity through new partnerships. Many nonprofits increased their capacity by partnering with several new organizations to deliver food in innovative ways, often very quickly. These collaborations are likely to persist beyond the pandemic.

In addition, new modes of technology were used to communicate changes within and throughout the network. It became apparent that message alignment and crisis communication was needed across all levels of the network, most importantly for the service population. Crisis communication is a continuous process of producing shared meaning among stakeholders who can work together to prepare, reduce, and respond to threats (Sellnow & Seeger, 2013). Nonprofit organizations must engage in crisis communication planning to help prepare for various crises they will inevitably face (Haupt & Azevedo, 2021; Sisco 2012). Crisis communication and planning is important for emergency‐related services to sustain their mission and meet community needs (Coombs & Holladay, 2002; Haupt & Azevedo, 2021). A key finding in this study was that communicating and understanding the multifaceted needs of vulnerable individuals, in this study defined as those who are food insecure, beyond nutrition and food security, is important for network partners. These needs expanded beyond nutrition and food programs, but to housing, health needs, and financial assistance for other core needs. The FVFB lacked message alignment within their communication strategies, suggesting their crisis communication plans lacked enough development. In addition, the social and political environment impacts communication as well as operations. In this study, those environments included a change in political leadership during a highly divisive election and social justice movements, like the #BlackLivesMatter movement. It was key, in the case of this network, to establish clear goals and objectives to ensure organizations were on the same page for serving their missions. Moving forward, organizations in this network may strengthen operations of the coalition to improve communication challenges while building their capacity.

Public health crises like COVID‐19 present all‐time highs for critical community needs like food and nutrition. It is key for nonprofit food networks to work with public health and emergency services, the United States Department of Agriculture, and other state and national partners to ensure food banks maintain a steady and critical supply of food needed for services they provide. This includes lobbying efforts to support the nonprofit sector to provide additional resources targeted exclusively for nonprofits. Regarding the third research question, the CARES Act was mentioned by many FVFB members as important for relieving financial stress in Virginia food banks caused by COVID‐19. While some strides were made through the CARES Act and American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) to include nonprofit support through the pandemic, these efforts fell short for many nonprofits addressing critical community needs due to resource shortages, lack of knowledge, or competition with local business for support (Azevedo et al., 2021).

The case of the FVFB suggests a need to further explore governance strategies for addressing turbulent issues facing nonprofits, in addition to crisis‐based communication strategies in food service networks and the impact of the CARES Act and ARPA more broadly among nonprofits. Organizations within the FVFB produced shared meaning to respond to the pandemic and community needs. It was clear, due to the number of partner agencies that closed their doors, that several organizations did not have adequate governance and planning for the crises beforehand. An examination of crisis communication strategies is needed to begin planning for future crises. To start, organizations in this study would benefit from action planning to develop the capacity of their specific organization and the network. In addition, individual members can enhance their competencies on crises and communication and continue to consider how financial shocks can impact operations during planning. This study continues to call for more qualitative and mixed methods research into understanding of nonprofit network processes and for work that is traditionally considered using quantitative analysis (Searing et al., 2021).

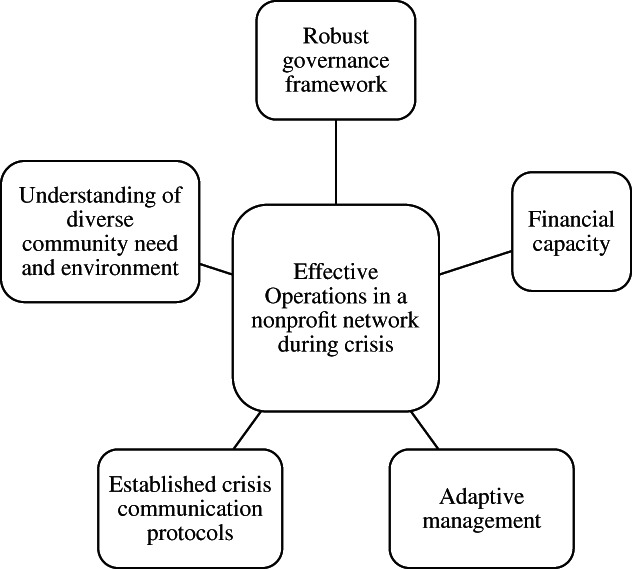

The findings in this study provide insight for creating a conceptual framework for large networks with multiple layers of partnerships to adapt to crisis situations impacting operations, resources, collaboration, and communication more successfully. Within this model, effective operations in nonprofit networks like the FVFB are guided by a robust governance framework, financial capacity, adaptive management, established crisis communication protocols, and understanding of diverse community need and the external environment during crises (see Figure 1). This framework helps to fill in some of the gaps identified in nonprofit literature surrounding nonprofit collaboration and understanding failures in collaborative relationships (Gazley & Guo, 2020). More work is still needed to explore these relationships in more depth and consider comparative work using more robust methodologies.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework for effective operations in a nonprofit network

7. CONCLUSION

While the economy is slowly recovering, those impacted most by the pandemic, including low income and underrepresented groups will feel the ravages of the pandemic in terms of inequality and social mobility for years to come (Dimitrijevska‐Markoski, 2022; Gaynor & Wilson, 2020; Medina & Azevedo, 2021; Sanchez‐Paramo et al., 2021). Findings in this study reveal positive responses from partner agencies within a nonprofit food network on their ability to communicate with partners and other stakeholders and adapt to their current situation during COVID‐19. The organizations within this study found technology can be a challenge but is increasingly important for operations and collaboration, even though traditional means of communication are still important for service populations. There is a need to improve relationships between state and regional partners with local nonprofits and their partners to ensure clear communication and information flow. This works best when there is a positive relationship prior to crisis situations. There is also a persistent need for better understanding of crisis communication between local nonprofits and vulnerable communities.

7.1. Public management and governance implications

There are several lessons learned from this network response to the COVID‐19 pandemic, beyond the importance of crisis communication. Nonprofits have been vitally important community leaders through the pandemic, both in providing immediately relief and programming and also in advocacy (Azevedo et al., 2021). One emerging theme in this network study is the importance of advocacy, both throughout the network and on behalf of the network to state representatives; confirming that network connections with focal actors are important (Dimitrijevska‐Markoski & Nukpezah, 2021). Many organizations in this study benefited from local grants and other state and federal resources from the CARES Act, though some organizations did not have access to these funds and faced great financial need or closed their doors. In the midst of a volatile social and political environment, nonprofit networks can concentrate on effective crisis communication by focusing on the mission and work of a network and agreeing on the importance of the network goals.

This study also suggests we can build resilient nonprofit systems and networks capable of coping with large scale disasters like the COVID‐19 pandemic by investing in collaborative capacity before crises occur, supporting crisis communication planning in nonprofit organizations, clear communication with partners during and post‐crisis, and, most importantly, addressing robust nonprofit governance. This study reaffirms previous findings on the importance of collaboration and collaborative capacity in effectively dealing with crisis (Dimitrijevska‐Markoski et al., 2021; Hocevar et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2014; Kapucu, 2006, 2007; Kapucu et al., 2011). Like its public sector counterpart, more work is needed on nonprofit governance strategies to account for turbulence, in both social environments and crises, where agendas, functions, challenges, and threats can be realized (Ansell et al., 2021; Howlett et al., 2018).

There are also implications for nonprofit leadership studies in building collaborative capacity and diverse crisis planning, which is an area under researched in nonprofit literature. This study begins to scratch the surface in terms of work to explore nonprofit crisis response in a statewide nonprofit network during a large‐scale health and economic crisis like COVID‐19. Nonprofit leaders must be well informed on the importance of collaborative capacity at all levels, including their members, relationships, organizational structure, and programs (Foster‐Fishman et al., 2001). Leaders should ensure there is a collaborative capacity leader who can be flexible enough to address complex problems and create and develop innovative and adaptive solutions.

7.2. Limitations and call for future research

A key limitation within this research is the limited sample of partner agencies that responded to the survey. This is likely due to the timing of the survey in the midst of the pandemic along with agency closures and understaffing. However, bearing in mind the qualitative nature of this study and the detailed nature of the interview and survey responses, the study gleaned a new and richly textured understanding of some of this network's experiences through COVID‐19 (Sandelowski, 1995).

Future work is needed to expand to other nonprofit networks and examine their responses to crises other than COVID‐19. The COVID‐19 crisis is a unique situation that most nonprofits were unprepared for in terms of crisis plans and operations; however, many organizations were able to adapt and adjust quickly to meet the needs of clients. Further, examining governance structures during crisis, within such a network like the FVFB, is a valuable contribution to collaborative governance system research. We call for more work that expands this line of inquiry. This study presented a preliminary conceptual framework, based on limited qualitative data. Additional empirical work is needed to examine the framework proposed in this study.

FUNDING INFORMATION

No funding information is associated with this project.

Supporting information

Appendix A

Appendix B

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors acknowledge Eddie Oliver and the FVFB for assistance throughout the research project in providing interviews, survey distribution, and expert knowledge and insight for the project. In addition, the authors thank Yulin Xu, doctoral student in Penn State's School of Public Affairs, for his work in collecting background information and in assisting with examining emerging qualitative themes for this project. This study received IRB approval from Virginia Commonwealth University.

Biographies

Lauren Azevedo is an Assistant Professor in the School of Public Affairs at Penn State Harrisburg. She conducts research in nonprofit management, capacity building, and social equity.

Brittany “Brie” Haupt is an Assistant Professor in the Homeland Security & Emergency Preparedness department at the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs at Virginia Commonwealth University. Her research focuses on crisis communication, cultural competence and community resilience. Her recent work examines social justice in crisis response and equitable decision‐making for crisis funding distribution.

Tamara Dimitrijevska Markoski is an Assistant Professor of Public Administration in the School of Public Affairs at the University of South Florida. Her research focuses on performance measurement and management, local governments and collaborative governance.

Azevedo, L. , Haupt, B. , & Markoski, T. D. (2022). Operational challenges in a US nonprofit network amid COVID‐19: Lessons from a food network in Virginia. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 33(2), 297–317. 10.1002/nml.21540

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research data are not shared.

REFERENCES

- Abou‐Sabe, K. , Romo, C. , McFadden, C. , & Longoria, J. (2020). COVID‐19 crisis heaps pressure on nation's food banks. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/covid-19-crisis-heaps-pressure-nation-s-food-banks-n1178731 [Google Scholar]

- Agranoff, R. , & McGuire, M. (2003). Collaborative public management: New strategies for local governments. Georgetown University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, H. (2020). Food banks, non‐profits ask for a helping hand as COVID‐19 cuts into operations. CTV News. https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/food-banks-non-profits-ask-for-a-helping-hand-as-covid-19-cuts-into-operations-1.4859340 [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C. , Sørensen, E. , & Torfing, J. (2021). The COVID‐19 pandemic as a game changer for public administration and leadership? The need for robust governance responses to turbulent problems. Public Management Review, 23(7), 949–960. [Google Scholar]

- Ansell, C. , & Trondal, J. (2018). Governing turbulence: An organizational‐institutional agenda. Perspectives on Public Management and Governance, 1(1), 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Antonovici, C. G. (2015). Adaptive management a solution for public administration in transformation. Global Journal on Humanities and Social Sciences, 2, 237–241. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, L. , Bell, A. , & Medina, P. (2021). Community foundations provide collaborative responses and local leadership in midst of COVID‐19. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 32, 475–485. 10.1002/nml.21490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control (CDC) . (2020). Health equity considerations and racial and ethnic minority groups. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/health-equity/race-ethnicity.html

- Comfort, L. K. , Waugh, W. L. , & Cigler, B. A. (2012). Emergency management research and practice in public administration: Emergence, evolution, expansion, and future directions. Public Administration Review, 72(4), 539–547. [Google Scholar]

- Conallin, J. C. , Dickens, C. , Hearne, D. , & Allan, C. (2017). Stakeholder engagement in environmental water management. In Water for the environment (pp. 129–150). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W. T. , & Holladay, S. J. (2002). Helping crisis managers protect reputational assets: Initial tests of the situational crisis communication theory. Management Communication Quarterly, 16(2), 165–186. [Google Scholar]

- Coombs, W. T. , & Holladay, S. J. (Eds.). (2011). The handbook of crisis communication. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Deitrick, L. , Tinkler, T. , Young, E. , Strawser, C. C. , Meschen, C. , Manriques, N. , & Beatty, B. (2020). Nonprofit sector response to COVID‐19. Nonprofit Sector Issues and Trends. 4. https://digital.sandiego.edu/npi-npissues/4 [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrijevska‐Markoski, T. (2022). Reducing COVID‐19 racial disparities: Why some counties make data‐driven decisions and others do not? Public Performance and Management Review. 10.1080/15309576.2022.2101131 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrijevska‐Markoski, T. , Hall, J. , & Azevedo, L. (2021). Implementation drivers of pay‐for‐success projects: The U.S. experience. International Journal of Public Administration. 10.1080/01900692.2021.1973494 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrijevska‐Markoski, T. , & Nukpezah, J. (2021). Determinants of network effectiveness: Evidence from a benchmarking consortium. International Journal of Public Sector Management, p. 1–15. 10.1108/IJPSM-06-2019-0175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dowdell, J. , & Lesser, B. (2020). COVID‐19 crisis strains needy and groups that help them. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-philanthropy-insig-idUSKCN21Y1XS [Google Scholar]

- Feeding America . (2022). Foodbank for the heartland. https://foodbankheartland.org/?gclid=CjwKCAjwsJ6TBhAIEiwAfl4TWF680639yMMQNafu2c8M6H2vkc6-2NF976p8RBYUSrIjQ94ozU_tABoC4joQAvD_BwE

- Foster‐Fishman, P. G. , Berkowitz, S. L. , Lounsbury, D. W. , Jacobson, S. , & Allen, N. A. (2001). Building collaborative capacity in community coalitions: A review and integrative framework. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(2), 241–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FVFB . (2021). Federation of Virginia Foodbanks: Support our mission. Accessed April 2, 2021. https://vafoodbanks.org/support-our-mission/

- FVFB . (2022). Federation of Virginia Foodbanks: About us. Accessed May 13, 2022. https://vafoodbanks.org/about-us/

- Garcia, J. E. (2020). Nonprofit of the year: San Antonia food bank. San Antonio Business Journal. https://www.bizjournals.com/sanantonio/news/2020/11/19/nonprofit-philanthropy-award-san-antonio-food-bank.html [Google Scholar]

- Gaynor, T. S. , & Wilson, M. E. (2020). Social vulnerability and equity: The disproportionate impact of COVID‐19. Public Administration Review, 80(5), 832–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazley, B. , & Guo, C. (2020). What do we know about nonprofit collaboration? A systematic review of the literature. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 31(2), 211–232. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R. M. , Speers, M. A. , McLeroy, K. , Fawcett, S. , Kegler, M. , Parker, E. , … Wallerstein, N. (1998). Identifying and defining the dimensions of community capacity to provide a basis for measurement. Health Education & Behavior, 25(3), 258–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haupt, B. , & Azevedo, L. (2021). Crisis communication planning and nonprofit organizations. Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal, 30, 163–178. 10.1108/DPM-06-2020-0197 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hocevar, S. P. , Thomas, G. F. , & Jansen, E. (2006). Building collaborative capacity: An innovative strategy for homeland security preparedness. In Beyerlein M. M., Beyerlein S. T., & Kennedy F. A. (Eds.), Innovation through collaboration: Advances in interdisciplinary studies of work teams (Vol. 12, pp. 255–274). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. 10.1016/S1572-0977(06)12010-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, M. , Capano, G. , & Ramesh, M. (2018). Designing for robustness: Surprise, agility and improvisation in policy design. Policy and Society, 37(4), 405–421. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Q. , Knox, C. C. , & Kapucu, N. (2014). What have we learned since September 11, 2001? A network study of the Boston marathon bombings response. Public Administration Review, 74(6), 698–712. [Google Scholar]

- Hyvärinen, J., & Vos, M. (2015). Developing a conceptual framework for investigating communication supporting community resilience. Societies, 5(3), 583–597. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, A. F. , Rauhaus, B. M. , & Webb‐Farley, K. (2020). The COVID‐19 pandemic: A challenge for US nonprofits' financial stability. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 33(1), 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kapucu, N. (2006). Public‐nonprofit partnerships for collective action in dynamic contexts of emergencies. Public Administration, 84(1), 205–220. [Google Scholar]

- Kapucu, N. (2007). Non‐profit response to catastrophic disasters. Disaster Prevention and Management, 16(4), 551–561. [Google Scholar]

- Kapucu, N. , Yuldashev, F. , & Feldheim, M. A. (2011). Nonprofit organizations in disaster response and management: A network analysis. European Journal of Economic and Political Studies, 4(1), 83–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kilduff, M. & Tsai, W. (2003). Social Networks and Organizations. London: Sage Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M. , & Mason, D. P. (2020). Are you ready: Financial management, operating reserves, and the immediate impact of COVID‐19 on nonprofits. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 49(6), 1191–1209. [Google Scholar]

- Kingsford, R. T. , Roux, D. J. , McLoughlin, C. A. , & Conallin, J. (2017). Strategic adaptive management (SAM) of intermittent rivers and ephemeral streams. In Intermittent Rivers and ephemeral streams (pp. 535–562). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kulish, N. (2020). ‘Never seen anything like it’: Cars line up for miles at food bank. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/08/business/economy/coronavirus-food-banks.html [Google Scholar]

- Leddy, A. M. , Weiser, S. D. , Palar, K. , & Seligman, H. (2020). A conceptual model for understanding the rapid COVID‐19–related increase in food insecurity and its impact on health and healthcare. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 112(5), 1162–1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullin, C. , & Raggo, P. (2020). Leadership and governance in times of crisis: A balancing act for nonprofit boards. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 49(6), 1182–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medina, P. S. , & Azevedo, L. (2021). Latinx COVID‐19 outcomes: Expanding the role of representative bureaucracy. Administrative Theory & Praxis, 43(4), 447–461. [Google Scholar]

- Meiksins, R. , & Jarrin, S. (2020). Nonprofit food banks and pantries alter program models to respond to COVID. Nonprofit Quarterly. https://nonprofitquarterly.org/nonprofit-food-banks-and-pantries-alter-program-models-to-respond-to-covid/ [Google Scholar]

- Mosley, J. E. , Maronick, M. P. , & Katz, H. (2012). How organizational characteristics affect the adaptive tactics used by human service nonprofit managers confronting financial uncertainty. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 22(3), 281–303. [Google Scholar]

- Moynihan, D. P. (2009). The network governance of crisis response: Case studies of incident command systems. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 19(4), 895–915. [Google Scholar]

- Noor, Z. , Wasif, R. , Siddiqui, S. , & Khan, S. (2021). Racialized minorities, trust, and crisis: Muslim‐American nonprofits, their leadership and government relations during COVID‐19. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 32, 341–364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OECD . (2020). Food supply chains and COVID‐19: Impacts and policy lessons. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=134_134305-ybqvdf0kg9&title=Food-Supply-Chains-and-COVID-19-Impacts-and-policy-lessons

- Provan, K. G. , & Kenis, P. (2008). Modes of network governance: Structure, management, and effectiveness. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18(2), 229–252. [Google Scholar]

- Provan, K. G. , & Milward, H. B. (1995). A preliminary theory of interorganizational network effectiveness: A comparative study of four community mental health systems. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, G. , & Bernard, H. (2003). Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods, 15(1), 85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez‐Paramo, C. , Hill, R. , Mahler, D. G. , Narayan, A. , & Yonzan, N. (2021). Covid‐19 leaves a legacy of rising poverty and widening inequality. WorldBank.org. https://blogs.worldbank.org/developmenttalk/covid-19-leaves-legacy-rising-poverty-and-widening-inequality [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health, 18(2), 179–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searing, E. A. , Wiley, K. K. , & Young, S. L. (2021). Resiliency tactics during financial crisis: The nonprofit resiliency framework. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 32(2), 179–196. [Google Scholar]

- Sellnow, T. L. , & Seeger, M. W. (2013). Theorizing crisis communication (Vol. 5). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. , Jang, H. S. , Keyes, L. , & Dicke, L. (2020). Nonprofit service continuity and responses in the pandemic: Disruptions, ambiguity, innovation, and challenges. Public Administration Review, 80(5), 874–879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisco, H. F. (2012). Nonprofit in crisis: An examination of the applicability of situational crisis communication theory. Journal of Public Relations Research, 24(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- South Milwaukee Human Concerns . (2022). South Milwaukee human concerns: Offering help and hope. https://smhumanconcerns.org/

- Wolfson, J. A. , & Leung, C. W. (2020). Food insecurity during COVID‐19: An acute crisis with long‐term health implications. American Journal of Public Health, 110(12), 1763–1765. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix A

Appendix B

Data Availability Statement

Research data are not shared.