Abstract

The COVID‐19 pandemic had a great impact on the mortality of older adults and, chronic non‐ transmissible diseases (CNTDs) patients, likely previous inflammaging condition that is common in these subjects. It is possible that functional foods could attenuate viral infection conditions such as SARS‐CoV‐2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), the causal agent of COVID‐19 pandemic. Previous evidence suggested that some fruits consumed by Amazonian Diet from Pre‐Colombian times could present relevant proprieties to decrease of COVID‐19 complications such as oxidative‐cytokine storm. In this narrative review we identified five potential Amazonian fruits: açai berry (Euterpe oleracea), camu‐camu (Myrciaria dubia), cocoa (Theobroma cacao), Brazil nuts (Bertholletia excelsa), and guaraná (Paullinia cupana). Data showed that these Amazonian fruits present antioxidant, anti‐inflammatory and other immunomodulatory activities that could attenuate the impact of inflammaging states that potentially decrease the evolution of COVID‐19 complications. The evidence compiled here supports the complementary experimental and clinical studies exploring these fruits as nutritional supplement during COVID‐19 infection.

Practical applications

These fruits, in their natural form, are often limited to their region, or exported to other places in the form of frozen pulp or powder. But there are already some companies producing food supplements in the form of capsules, in the form of oils and even functional foods enriched with these fruits. This practice is common in Brazil and tends to expand to the international market.

Keywords: açai berry, camu‐camu, amazon fruits, COVID‐19, Brazil nuts, cocoa, guarana

Amazonian fruits have bioactive molecules, which present antioxidant activity, modulate inflammatory cytokines and assist in tissue regeneration and functions. Thus, they can help reduce the clinical complications caused by aging and aggravated by COVID‐19, and may even decrease SARS‐COV‐2 infection.

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is a complex respiratory disease caused by the new severe acute respiratory syndrome‐coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), that affects the immune system, producing a systemic inflammatory response, which plays a crucial role in the clinical manifestation (Chen et al., 2020; Chen, Kelley, & Goldstein, 2020; Ye, Wang, & Mao, 2020). The severity of COVID‐19 is related to “cytokine storm syndrome”, maladaptive pro‐inflammatory cytokines response to the virus infection (Ruan, Yang, Wang, Jiang, & Song, 2020; Ye et al., 2020), disruption of the immune system altering the gene expression related to cellular senescence (Zheng et al., 2020), and, also, mitochondrial dysfunction, that increases the oxidative stress at a cellular level (Moreno Fernández‐Ayala, Navas, & López‐Lluch, 2020). Most patients infected are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms of COVID‐19. But around 20% of patients, manifest severe symptoms, presenting high mortality risk (Chen et al., 2021; Chen, Hu, et al., 2020; Chen, Kelley, & Goldstein, 2020; Ye et al., 2020) Patients over 70 years old and carriers of non‐transmissible chronic diseases (NTCDs) are considered patients with high susceptibility to develop the cytokine storm syndrome associated with worsened COVID‐19 symptoms and greatest mortality risk (Annweiler et al., 2020; Ruan et al., 2020).

Age itself is a significant risk factor for developing COVID‐19 and its adverse health outcomes (Chen, Hu, et al., 2020; Chen, Kelley, & Goldstein, 2020) due to strong association with immunosenescence processes that lead to chronic, sterile, low‐grade inflammation states – called inflammaging, and decreasing in the immunocompetence that increase the susceptibility to infections, autoimmune and cancer conditions (Franceschi et al., 2018; López‐Lluch, Hernández‐Camacho, Fernández‐Ayala, & Navas, 2018; Moreno Fernández‐Ayala et al., 2020). The accumulation of mitochondria damaged due to the disruption or malfunction of different nutrient‐sensing mechanisms in cells is one of the hallmarks of aging and the main sources of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that increase oxidative damage during aging and are associated with chronic inflammation and defective immune response to viral infections (López‐Lluch et al., 2018; Moreno Fernández‐Ayala et al., 2020). Some authors consider that immunosenescence and inflammaging states could contribute to hyperinflammatory syndrome triggered by COVID‐19 infection (Müller & Di Benedetto, 2021; Xu, Wei, Giunta, Zhou, & Xia, 2021).

On the other hand, evidence suggests that dietary patterns and individual nutrients can influence immune functions (Zabetakis, Lordan, Norton, & Tsoupras, 2020). Therefore, a balanced intake of macronutrients and micronutrients (i.e., vitamins C and D, selenium, zinc) and phytochemicals such as polyphenols are an ally at this time and may help to modulate immune function, including enhancing defense and resistance to infection, reduction of NCDs (noncommunicable diseases) having a significant impact on an individual's overall health (Calder, Carr, Gombart, & Eggersdorfer, 2020; Wu, Lewis, Pae, & Meydani, 2019; Zabetakis et al., 2020). In this sense, proper nutrition leads to optimal functioning of the immune system and may be associated with better results regarding the prevention and complications of COVID‐19, as well as for other pathogens (Chaari, Bendriss, Zakaria, & McVeigh, 2020; Galmés, Serra, & Palou, 2020).

Brazilian native fruits are unmatched in their variety, but poorly explored resource with the potential to improve human health and wellness (Infante, Rosalen, Lazarini, Franchin, & de Alencar, 2016). Many of these native fruits have biodiversity and are sources of bioactive compounds and sometimes are unknown or little known to consumers (Biazotto et al., 2019). Fruits specimens such as acerola (Malpighia emarginata), cashew apple (Anacardium occidentale), pineapple (Ananas comosus) and taperebá (Spondias mombin), harvested in Amazonian and Northeast regions are rich sources of water‐soluble vitamins (e.g., vitamin C), phytosterols and phenolic compounds(Bataglion, da Silva, Eberlin, & Koolen, 2015). From the Brazilian Savanna (Cerrado) there is mirindiba (Buchenavia tetraphylla), which is also rich source of vitamin C, phenolics, carotenoids and tocopherols (Borges et al., 2022).

The consumption of certain fruits and seeds might help to treat coronaviruses, showing themselves as a potentially effective alternative and complementary therapies due to their diverse range of natural compounds, biological and therapeutic properties (Idrees, Khan, Memon, & Zhang, 2020). Tropical fruit consumption is increasing due to growing recognition of its nutritional and therapeutic value (Rufino, Alves, Fernandes, & Brito, 2011). Some fruits and seeds from the Amazon Biome consumed since the pre‐Columbian period have been studied for their potential bioactive compound's sources such as carotenoids, polyphenols, unsaturated fatty acids, vitamins, and trace elements (Assmann et al., 2021; Cândido, Silva, & Agostini‐Costa, 2015).

Therefore, it is possible that some Amazonian fruits habitually consumed by riverine and indigenous populations could present relevant attenuative proprieties against complications triggered by COVID‐19 infection from biochemical modulations of oxidative and inflammatory metabolism. This hypothesis is based on epidemiological and anthropological investigations suggesting that traditional diets of hunter‐gatherer societies are diverse and nutritious and associated with health and well‐being (Donders & Barriocanal, 2020; Kuhnlein, 2015). A large part of the elements of this Pre‐Columbian diet persists in the riverside and indigenous communities of the Amazon, with emphasis on a great diversity of fruits.

In fact, Brazilian Amazon Region has great biodiversity with about species of edible plants that produce fruits, representing 44% of the diversity of native fruits in Brazil (Serra et al., 2019). Many of these fruits, in addition to being used as nutritional support, are also used in traditional medicine in these communities that are constantly exposed to a large number of pathogens as a result of the tropical environment. Previous studies by our research team in riverine older adults suggested the contribution of some foods in the health and functional fitness maintenance (da Costa Krewer et al., 2011; Maia Ribeiro et al., 2013).

In this context, we reviewed literature data from five Amazonian fruits that have potential mitigating effects on inflammatory and clinical complications associated with COVID‐19 infection.

2. METHODS

The present narrative review compiled and discussed experimental, epidemiological, and clinical data on açai berry (Euterpe oleracea Mart.), Brazil nuts (Bertholletia excelsa), camu‐camu (Myrciaria dubia [Kunth] McVaugh), Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) and guarana (Paullinia cupana). As most Amazonian fruits are still unknown to non‐Amazonian populations, we chose these fruits because they already have some level of worldwide popularity in their use in natural or in the form of supplements. The review used the popular name and/or the scientific name of each fruit to identify: the total number of articles, number of articles written in English, reviews, articles reporting antioxidant, anti‐inflammatory, and anti‐viral activity. A search was also made for articles reporting studies that involved any of these fruits and COVID‐19. Investigations and reviews focusing on antioxidant, anti‐inflammatory and antiviral activity were selected. In this case, previous reviews involving these biochemical and physiological properties often replaced publications cited by them.

3. RESULTS

Initially we performed a quantitative analysis of the number of publications with the five Amazonian fruits analyzed here and, data are summarized in Table 1. We found an expressive number of studies describing antioxidant and anti‐inflammatory effects that could mitigate complications associated with SARS‐CoV2 infection, mainly in subjects carrying inflammaging conditions. However, the number of studies related to the antiviral effect of these fruits was much smaller.

TABLE 1.

Identification of studies published in indexed PubMed journals of Amazonian fruits with potential biochemical proprieties against COVID‐19

| Number of PubMed articles | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | In English | Reviews | |

| Açai (Euterpe oleracea Mart) | 525 | 34 | 511 |

| Anti‐oxidation | 205 | ||

| Anti‐inflammatory/inflamation | 47 | ||

| Antiviral | 4 | ||

| COVID‐19 | 0 | ||

| Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) | 811 | 61 | 780 |

| Anti‐oxidation | 742 | ||

| Anti‐inflammatory/inflamation | 240 | ||

| Antiviral | 7 | ||

| COVID‐19 | 0 | ||

| Camu‐camu (Myrciaria dubia [Kunth] McVaugh) | 516 | 46 | 472 |

| Anti‐oxidation | 58 | ||

| Anti‐inflammatory/inflamation | 45 | ||

| Antiviral | 7 | ||

| COVID‐19 | 0 | ||

| Cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) | 4152 | 304 | 3884 |

| Anti‐oxidation | 583 | ||

| Anti‐inflammatory/inflamation | 124 | ||

| Antiviral | 25 | ||

| COVID‐19 | 3 | ||

| Guaraná (Paullinia cupana) | 384 | 23 | 368 |

| Anti‐oxidation | 64 | ||

| Anti‐inflammatory/inflamation | 18 | ||

| Antiviral | 1 | ||

| COVID‐19 | 0 | ||

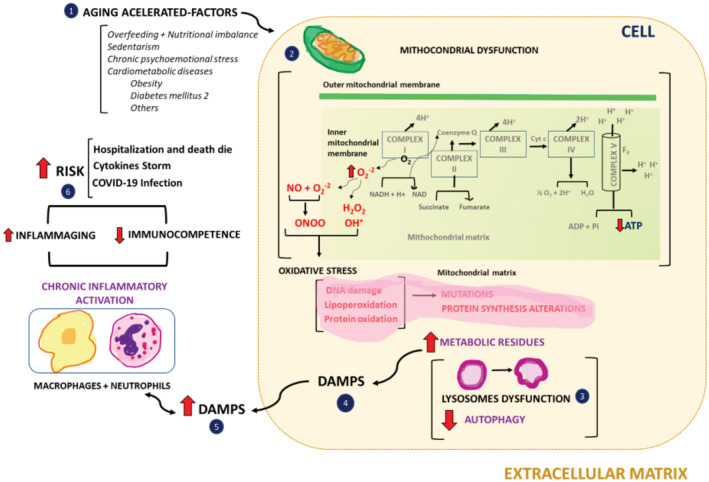

As the citation of many studies are repeated throughout publications, we chose to make a narrative review based on the evidence that such plants could be of interest in attenuation of complications related to COVID‐19, especially in adults and NCTDs patients. To better understand the biological role of these fruits in the attenuation of oxidative‐inflammatory events related to COVID‐19, we organized a figure that schematically identifies the main events related to the maintenance of low‐grade chronic inflammatory states found in older adults and CNTDs (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Main biochemical and cellular events related to establishment of low‐grade chronic inflammatory states common in older adults and chronic‐noncommunicable diseases (CNTDs) patients which could contribute to clinical complications associated with COVID‐19 infection. The numbers in the figure identify the main events related to the establishment of chronic low‐grade inflammation that are described in the text

Figure 1 identifies the following relevant events in inflammaging conditions observed in older adults and NCTDs patients that could be positively modulated by the Amazon fruits analyzed here. (1) Aging accelerating factors contribute to the establishment of mitochondrial dysfunction, which increases the production of oxygen by‐products (especially the superoxide anion) formed in the mitochondrial phosphorylation chain, thus decreasing the efficiency of energy production (ATP); (2) The uncontrolled increase in superoxide anion levels, via decreased efficiency and production of the antioxidant enzyme manganese‐dependent superoxide dismutase (SOD2) or even the low intake of non‐enzymatic antioxidant components present in the diet, contributes to the production of other reactive oxygen species (ROS), in particular hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and the hydroxyl radical (OH+). As H2O2 is highly soluble in membranes, its migration to the cytoplasm can generate reactions with metals (mainly Fe and Zn) increasing OH+ levels, which cause significant damage to the DNA molecule, thus contributing to alterations in protein synthesis. Furthermore, as the superoxide anion has a high affinity for nitric oxide (NO), the reaction of these two molecules has two very relevant consequences. The first one induces an increase in reactive oxygen species, especially peroxynitrite (‐ONOO), which causes lipoperoxidation and extensive protein oxidation in cell structures, and in signaling and functional molecules. The second concerns the depletion of NO, which is a crucial regulatory molecule in several physiological routes, especially vasodilation and the control of the innate inflammatory response to pathogens; (3) In general, enzymatic, and non‐enzymatic antioxidant systems are also affected, contributing to the generation of a state of oxidative stress that produces a large amount of metabolic wastes. In a healthy cell, these wastes are quickly metabolized by lysosomes, by a process known as autophagy. However, oxidative stress also contributes to the generation of lysosomal dysfunction, which causes these residues to accumulate inside the cell and in the extracellular matrix; (4, 5) Due to the altered nature of metabolic residues, they become immunogenic and are now identified as DAMPs (Damage‐associated molecular patterns). DAMPs can activate the inflammatory response by tissue‐resident macrophages, which in turn, recruit a greater number of macrophages and neutrophils. As the generation of DAMPs is continued, the inflammatory response is not resolved, thus establishing a state of low‐grade chronic inflammation; (6). This process leads to the constitution of immunosenescence highly prevalent in the older adult, which has highly relevant consequences against infection by the SARs‐Cov‐2 virus. This is because it increases the risk of viral infection and less responsiveness to immunization and increases the risk of the onset of cytokine storm, which is highly related to hospitalization and death by COVID‐19. For the same motive, patients with cardiometabolic conditions, specially DM2 (Diabetes Mellitus type 2) are very susceptible to COVID‐19.

Data from literature indicates that most of these changes can be partially attenuated or reversed through foods rich in antioxidant, genoprotective, and anti‐inflammatory molecules, including the Amazonian fruits reviewed here.

3.1. Açaí

Açai (Euterpe oleracea Martius, family Arecaceae) is a palm tree that produces deep purple berry fruits (Earling, Beadle, & Niemeyer, 2019). It is one of the most popular functional foods of Amazon and is widely used in the world (Yamaguchi, Pereira, Lamarão, Lima, & Da Veiga‐Junior, 2015). This fruit is a well‐recognize functional food, so‐called a “superfruit “due to its range of phytochemicals mainly flavonoids (31%), followed by phenolic acids (23%), liquids (11%), and anthocyanins (9%) (Chang, Alasalvar, & Shahidi, 2019; Yamaguchi et al., 2015). Açai also presents vitamin C and carotenoids (Chang et al., 2019). These bioactive compounds contains in açai are associated with antioxidant, anti‐inflammatory, antiproliferative, and cardioprotective proprieties (Assmann et al., 2021; Bahadoran, Mirmiran, & Azizi, 2013; Kim, Lee, & Lee, 2011).

It is known that SARS‐CoV‐2 utilizes the angiotensin‐converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors to infect the host cells (Guo et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020). The sites where ACE2 protein is expressed are the regions belonging to type II of alveolar lung cells and enterocytes of the small intestine (Channappanavar & Perlman, 2017; Guo et al., 2020; Zheng et al., 2020), thus, causing, respiratory and intestinal tract infections (Channappanavar & Perlman, 2017). Thus, SARS‐CoV‐2 entry into a host cell involves the binding of a virus protein to the ACE‐2 receptor on the cell surface and fusing the viral envelope to the cell membrane (Guo et al., 2020). Four structural proteins are encoded in all coronaviruses (i.e., spike, nucleocapsid, membrane, and envelope protein), among these, the spike protein is the largest and is required for viral entry into host cells (Casalino et al., 2020). In silico study showed that flavonoid‐based molecules, like the one found in açaí, can bind with high affinity to the spike protein, helicase, and protease sites on the ACE2 receptor used by the coronavirus to infect cells and cause COVID‐19 (Ngwa et al., 2020).

When SARS‐CoV‐2 enters into the host cell, it triggers an immune response against the virus, which, if uncontrolled, may result in pulmonary tissue damage, functional impairment, and reduced lung capacity (Li et al., 2020). Some risk factors and conditions can make people more vulnerable to becoming severely ill with COVID‐19 such as smoking, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and other CNTDs (Ruan et al., 2020). An animal model study compared lung damage in mice induced by chronic (60‐day) inhalation of regular cigarettes smoke and smoke from cigarettes containing 100 mg of hydroalcoholic extract of açai berry stone. The results showed that the presence of açai extract in cigarettes had a protective effect against emphysema in mice, reducing the increase in leukocytes in the damaged tissue, also reducing the enlargement of alveolar space, and increasing the antioxidant enzyme activities such as myeloperoxidase(De Moura et al., 2011).

A clinical trial with 37 individuals with metabolic syndrome (BMI 32.5 ± 6.7 kg/m2) was randomized to consume 325 mL of açai juice or placebo twice a day for 12 weeks. The results showed the açai juice consumption decreased plasma levels of interferon‐gamma (IFN‐γ) and urinary levels of 8‐ isoprostane when compared to the control group (Kim et al., 2018). de Liz et al., (2020) evaluated fasting glucose, lipid profile, and oxidative biomarkers in 30 healthy subjects supplemented with of açai juice or juçara juice (200 mL/day) for 4 weeks and 4 weeks of wash‐out. The results showed that the regular consumption of açai juice had a positive impact on HDL‐cholesterol levels and increased the antioxidant enzyme activities (de Liz et al., 2020). Similar results were observed by Pala et al. (2018) among 40 healthy young female adults consuming 200 g of açai pulp/day for 1 month (Pala et al., 2018).

Dietary deficiencies can induce oxidative stress, affecting an individual's immune response, leading to increased susceptibility to different types of disease, including viral diseases such as COVID‐19 (Zabetakis et al., 2020). Implementing a diet with antioxidant nutrients such as açai may improve the outcome of coronavirus infection, especially in the elderly.

3.2. Brazil nuts

Bertholletia excelsa H.B.K. (Lecythidaceae family), popularly known as Brazil nut, is a tree nut native of the Amazon rainforest and consumed worldwide (Silva Junior et al., 2017). It is a dietary source of a range of phytochemicals as phenolic compounds, gallic acid, ellagic acid, vanillic acid, and catechin (John & Shahidi, 2010; Yang, 2009). These bioactive compounds present antioxidant and anti‐inflammatory activities and are associated with beneficial effects on health (Bahadoran et al., 2013). When compared to other nuts, Brazil nuts have a higher content of selenium (Se), trace minerals like magnesium, copper, zinc, and a low concentration of iron (Cardoso, Duarte, Reis, & Cozzolino, 2017). Nuts, in general, are characterized by high nutritional value, can provide around 20–30 kJ/g being considered nutrient‐dense foods and are recommended as part of a healthy diet (Silva Junior et al., 2017; Yang, 2009).

A study has investigated the effect of foods and nutrients as complementary approaches on the recovery from COVID‐19 in 170 countries. Tree nuts, including Brazil nuts, were considered important contributors to COVID‐19 recovery rates, being one of the most important sources of fats after vegetable oils, with high mono and polyunsaturated fats (MUFA and PUFA) ratios (Cobre et al., 2021). Brazil nuts fatty acid (FA) profile showed that the major FA presents were 18:3n‐3 (α‐linolenic acid) and 18:1 (oleic acid), a predominance of PUFA over MUFA (Afonso Da Costa, Ballus, Teixeira Filho, & Teixeira Godoy, 2011).The α‐linolenic acid (omega‐3) contributes to 7% of total fats in Brazil nuts (Yang, 2009). Brazil nut presents the desired profile of fatty acids regarding the n‐6/n‐3 ratio (Afonso Da Costa et al., 2011), optimizing the bioavailability and metabolism (Garg, Leitch, Blake, & Garg, 2006). Omega‐3 is PUFA, which plays a role in mediating inflammatory processes and immunomodulation for immune systems and can weaken the antiviral response of CD8 T cells and thereby could potentially be used to modulate cytokine responses to viral infection as COVID‐19 (Hathaway et al., 2020).

Brazil nuts are among the richest selenium sources and might be considered an alternative for selenium supplementation (Cardoso et al., 2017). Selenium is an essential micronutrient with antioxidant capacity that aids in different physiological processes such as immune system modulation, heavy metal, and xenobiotic detoxification. One Brazil nut may contain up to 400 μg of selenium, and it has high bioavailability (Cardoso et al., 2017; Thomson, Chisholm, McLachlan, & Campbell, 2008). Depending on its origin, a single Brazil nut could provide from 11% (Mato Grosso nut) up to 288% (Amazon nut) of a daily Se requirement for an adult man (70 μg) (Silva Junior et al., 2017). Stockler‐Pinto, Mafra, Farage, Boaventura, & Cozzolino (2010) & Stockler‐Pinto et al. (2014) performed a study on hemodialysis patients, who have been considered to have higher inflammatory and oxidative plasma levels then healthy subjects. They supplemented the patients with one nut per day for 3 months. The results showed that plasma Se and GPx (Glutathione peroxidase) activity increased, while cytokine (TNF‐α, IL‐6), 8‐Hydroxy‐2′‐deoxyguanosine (8‐OHdG), and 8‐isoprostane plasma levels decreased significantly. They concluded Brazil nut as a Se source plays an important role as an anti‐inflammatory and antioxidant agent (Stockler‐Pinto et al., 2010, 2014). In addition, Brazil nuts present a potential nutrigenetic response, in some antioxidant genes as SOD2 (superoxide dismutase 2) (Schott et al., 2018).

The nutritional status of a patient infected with COVID‐19 must also be considered, as nutritional deficiencies can increase the risk of severe infection, along with oxidative stress and inflammatory status (De Faria Coelho‐Ravagnani et al., 2021; Zabetakis et al., 2020). In this sense, high dense food like Brazil nuts may be considered helping in this battle against COVID‐19.

3.3. Camu‐Camu

Myrciaria dubia (HBK) McVaugh (Myrtaceae), known as camu‐camu, (Yuyama et al., 2002) is an extremely acidic fruit, mostly consumed in the form of processed pulp (Conceição et al., 2019). Nowadays it is easy to find camu‐camu powder available on internet websites. And, the frozen fruit pulp is being exported to Japan, Asia, Europe, and the United States (Castro, Maddox, & Imán, 2018). Camu‐camu is a member of the so‐called group of superfruits, it can potentially play a role in multimodal, integrative approaches to health management (Langley, Pergolizzi, Taylor, & Ridgway, 2015) due to its biological activities that include anti‐inflammatory (Do et al., 2021; Yazawa, Suga, Honma, Shirosaki, & Koyama, 2011), neuroprotective (Azevêdo, Borges, Genovese, Correia, & Vattem, 2015), antioxidant (Rufino et al., 2011), and immunomodulatory activity (Yunis‐Aguinaga et al., 2016).

Camu‐Camu has high nutritional value because of a range of bioactive compounds, such as phenolic compounds, including myricetin‐O‐pentoside and cyanidin‐3‐O‐glucoside being the main compounds in peels, followed by p‐coumaroyl hexoside in the pulp and ellagic acid in the seeds (Conceição et al., 2019). The main flavonoids present are quercetin and kaempferol derivatives (Langley et al., 2015). It also contains other polyphenols as tannins, stilbenes, lignans, and anthocyanins (Conceição et al., 2019). In addition, it also contains such minerals as potassium, sodium, calcium, zinc, magnesium, manganese, and copper (Langley et al., 2015; Zanatta & Mercadante, 2007). The concentration of these compounds will depend on the state of maturity of the plant (Souza, Silva & Aguiar, 2020).

Furthermore, camu‐camu is particularly known for its high vitamin C (1380–1490 mg/100 g pulp and 2050 mg/100 g peel) content (Zanatta & Mercadante, 2007). Humans depend on the diet as a source of vitamin C to prevent vitamin C deficiency disease since they cannot synthesize ascorbic acid (Traber & Stevens, 2011). Vitamin C is essential for life and required for different biological functions, in addition to being a powerful water‐soluble antioxidant molecule (Padayatty et al., 2003; Traber & Stevens, 2011). Immune cells respond to foreign infection by producing large quantities of ROS to destroy invading organisms (Hoang, Shaw, Fang, & Han, 2020), as an antioxidant, vitamin C protects against oxidative stress‐induced cellular damage by scavenging ROS (Halliwell, 1999).

The new‐type coronavirus infection causes an inflammatory cytokine storm in patients (Ye et al., 2020). This over‐production of cytokines (e.g., Interleukin (IL)‐ 1β, IL‐8, IL‐6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)‐α) by the immune system is accompanied by immunopathological changes in the lungs and extrapulmonary organ failures (Channappanavar & Perlman, 2017; Chen, Hu, et al., 2020; Chen, Kelley, & Goldstein, 2020; Ye et al., 2020). Chen, Hu, et al., 2020; Chen, Kelley, & Goldstein, 2020 analyzed via system biology tools the potential of vitamin C from some fruits, among them Myrciaria dubia, in modulating targets and pathways relevant to immune and inflammation responses (Chen, Hu, et al., 2020; Chen, Kelley, & Goldstein, 2020). An in vitro study of ROS high glucose‐induced in keratinocytes showed that camu‐camu has the potential in inhibiting the expression of inflammatory mediators (nuclear factor of activated T‐cells (NFTA) and nuclear factor kappa beta (NF‐kβ)) to regulate the anti‐inflammatory reaction by activating the expression of nuclear factor E2‐related factor 2 (Nrf2). The NF‐kB is a transcription factor that regulates cytokine production, inflammation, and innate immunity, and it is activated by ROS (Karin & Greten, 2005). In biopsies obtained from COVID‐19 patients the suppression of NRF2 antioxidant gene was observed (Olagnier et al., 2020).

Inoue, Komoda, Uchida, and Node (2008) conducted a study on 20 habitual male smokers who have accelerated oxidative stress and inflammatory state. The volunteers were assigned to take daily 1,050 mg of vitamin C tablets or 70 mL of 100% camu‐camu juice containing 1,050 mg of vitamin C for 7 days. The results showed that the camu‐camu group had 8‐OHdG levels, serum total ROS levels, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein (CRP), IL‐6 and IL‐8 levels significantly decreased when compared to the vitamin C group. The authors concluded that camu‐camu presented antioxidative and anti‐inflammatory activities higher than a daily intake of 1,050 mg of vitamin C tablets. Notwithstanding contents of vitamin C tablets were equivalent to camu‐camu juice (Inoue et al., 2008). Besides some claim that the administration of high‐dose vitamin C is a safe and effective therapy for severe cases of respiratory viral infection, such as COVID‐19 (Hoang et al., 2020). A comprehensive literature review on the matter concluded that causality could not be claimed between the administration of pure vitamin C and the improvement of the patients' medical status with COVID‐19 (Milani, Macchi, & Guz‐Mark, 2021).

Evidence has shown that camu‐camu is a versatile berry, with its pulp, seeds, and skin all presenting antioxidant and anti‐inflammatory activities in differing degrees (da Silva et al., 2012; Do et al., 2021; Langley et al., 2015; Rufino et al., 2011; Souza et al., 2020). The biological activities presented by camu‐camu are possible due to the joint effect of its phytochemicals content such as polyphenols (e.g., flavonoids, gallic acid, quercetin, and ellagic acid) and anthocyanins, and minerals such as potassium that increase the in vivo bioavailability of vitamin C (Do et al., 2021; Inoue et al., 2008; Langley et al., 2015). And can be effective in helping to treat COVID‐19 complications in older adults' patients.

3.4. Cocoa

Theobroma cacao L. (family Malvaceae), popularly known as cocoa or cacao, is commonly used to produce and chocolate and cocoa powder (Nabavi, Sureda, Daglia, Rezaei, & Nabavi, 2015). However, it has been used for medicinal purposes in Mesoamerica since 1,000 B.C (Katz, Doughty, & Ali, 2011; Yañez et al., 2021). Genetic classifications divide the types of cocoa into three main groups: Criollo, Forastero Amazonian, and Trinitario (hybrid type) (Beckett, 2008; Motamayor et al., 2008).

Cocoa beans are a rich source of polyphenols as phenolic compounds (12%–18% dry weight) (Ramirez‐Sanchez, Maya, Ceballos, & Villarreal, 2010), belonging to the tannin and flavonoid classes (Efraim, Alves, & Jardim, 2011). For example, cocoa dark powder contains up to 50 mg of polyphenols per gram (Katz et al., 2011). The main flavonoids found in cocoa are epicatechin and catechin (flavan‐3‐ols), and procyanidins (Efraim et al., 2011 Katz et al., 2011; Ramirez‐Sanchez et al., 2010; Ramiro‐Puig & Castell, 2009). The phenolic content depends on the genetic background and geographical origins. Cocoa seeds Forastero Amazonian contain 30%–60% more phenolic compounds than those in the Criollo (de Brito et al., 2001). The cocoa beans also contain several minerals such as magnesium, copper, potassium, iron, and calcium (Steinberg, Bearden, & Keen, 2003).

Flavonoids have a variety of biological activities, including antioxidant anti‐inflammatory, antiplatelet, and immunoregulatory activity (Kim et al., 2011). Studies have supported a protective association between cocoa and/or chocolate consumption against some diseases potentiated by ROS (Katz et al., 2011), including, cardiometabolic disease (Steinberg et al., 2003), diabetes (Ramos, Martín, & Goya, 2017), neurodegenerative diseases (Oñatibia‐Astibia, Franco, & Martínez‐Pinilla, 2017), and cancer (Martin, Goya, & Ramos, 2017). A study analyzed the effect of the intake of a single dose of high‐polyphenols cocoa on gene expression in peripheral mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and conjugated (−)‐epicatechin metabolites in plasma. The results showed that cocoa treatment triggered changes in expression in a group of 98 genes, while 18 genes had the expression modified in the control group. It also suggested anti‐inflammatory effects, decreasing ROS production, leukocyte activation, and calcium mobilization, suggesting anti‐inflammatory effects (Barrera‐Reyes, de Lara, González‐Soto, & Tejero, 2020).

Another study has shown that dark chocolate consumption decreased platelet adhesion 2 hr after intake, serum oxidative stress decreased in 22 heart transplant patients compared with the control group. These results were positively correlated with changes in serum epicatechin concentration. Patients with severe COVID‐19 have been manifesting arterial and venous thrombosis as well as a hypercoagulable state of the blood (Abou‐Ismail, Diamond, Kapoor, Arafah, & Nayak, 2020; John et al., 2021). An in vitro and ex vivo study on the effects of cocoa beverage consumption concluded that cocoa flavanols and their metabolites can modulate the activity of platelets and leukocytes (Heptinstall, May, Fox, Kwik‐Uribe, & Zhao, 2006). Another study, also, has shown that dark chocolate consumption decreased platelet adhesion 2 hr after intake, serum oxidative stress decreased in 22 heart transplant patients compared with the control group. These results were positively correlated with changes in serum epicatechin concentration (Flammer et al., 2007).

Mpro is the main protease of SARS‐CoV‐2, a key enzyme in mediating viral replication and transcription (Jin et al., 2020). A computational study has analyzed the antioxidant capacity and Mpro inhibitory activity of 30 polyphenolic molecules derived from cocoa. Results suggested that the flavonoids isorhoifolin and rutin, all present in Criollo, Trinitario, and Forastero cocoa beans, are antioxidant molecules with the potential to attenuate the SARS‐CoV‐2, which causes COVID‐19 (Yañez et al., 2021). A docking simulation study has shown that plant flavan 3‐ols and proanthocyanidins have inhibitory activity against the Mpro activity. Followed by an in vitro analysis with extracts prepared from cocoa, dark chocolate, and other two plants, which contain these polyphenols, have shown that all extracts inhibited the Mpro activity with an IC50 (half maximal inhibitory concentration) value (Zhu & Xie, 2020).

In addition to polyphenols, T. cacao contains methylxanthine compounds, such as theobromine (2%–3%) and caffeine (0.2%) (Martínez‐Pinilla, Oñatibia‐Astibia, & Franco, 2015), for example, 50 g of dark chocolate contains 250 mg theobromine and 19 mg caffeine (Smit, Gaffan, & Rogers, 2004). Methylxanthines also, are considered key players in the beneficial effects of cocoa. The main action mechanism of theobromine consists of blocking adenosine receptors and inhibiting phosphodiesterases (Martínez‐Pinilla et al., 2015). Evidence data support that chronic lung diseases such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and pulmonary fibrosis may benefit from antagonizing the adenosine receptors treatments (Zhou, Schneider, & Blackburn, 2009). Moreover, the theobromine in respiratory diseases can negatively affect the poly (ADP‐ribose) polymerase‐1, a nuclear enzyme that is poorly inhibited by caffeine but significantly inhibited by theobromine (Geraets, Moonen, Wouters, Bast, & Hageman, 2006). Thus, the immunoregulatory activity of the cocoa beans can be due to the theobromine action in the inhibition of the poly (ADP‐ribose) polymerase‐1 enzyme (Martínez‐Pinilla et al., 2015). Since this enzyme can affect both innate and adaptive immune responses, and it is associated with the pathophysiology of acute and chronic inflammatory diseases (Geraets et al., 2006; Laudisi, Sambucci, & Pioli, 2011).

The progression of COVID‐19 is centered on the loss of the immune regulation between protective and altered responses due to exacerbation of the inflammatory components (García, 2020). In this sense, cocoa could be considered a safe and natural alternative in the treatment or attenuation of COVID‐19.

3.5. Guaraná

Guaraná, Paullinia cupana Kunth. (Sapindaceae), have been used for centuries by Amazonian indigenous tribes as a stimulant in festivals and hunting, aphrodisiac, and medicinal uses (Mendes et al., 2019). It is consumed as a powder obtained from toasted seeds, or it can be taken simply by dissolving the powder in water, alone, or in combination with other herbal medicine (Machado et al., 2021). Guaraná is known for its high amount of caffeine (3.5%–6%) (Pagliarussi, Freitas, & Bastos, 2002). But it, also, contains theobromine and theophylline, and polyphenols mainly catechin, epicatechin, procyanidin A1, procyanidin B2, with a flavan‐3‐ols profile very similar to that of cocoa (Mendes et al., 2019; Pagliarussi et al., 2002). A docking simulation study has shown that plant flavan‐3‐ols and proanthocyanidins can inhibit the activity of the main protease Mpro activity of SARS‐CoV‐2 (Zhu & Xie, 2020).

Evidence has shown that guaraná presents strong antioxidant and radical‐ scavenging properties (Maldaner et al., 2020; Roggia et al., 2020; Santana & Macedo, 2018; Yonekura et al., 2016), protective cellular and anti‐inflammatory properties (Machado et al., 2021), neuroprotective effect (Veloso et al., 2018), and anti‐aging proprieties (Arantes et al., 2018) An epidemiological study reported guaraná habitual consumption by older adult riverine with a lower prevalence of hypertension, obesity, and metabolic syndrome (da Costa Krewer et al., 2011). Yonekura et al. (2016) had shown that small daily doses of guaraná (3 g) can improve oxidative stress markers in healthy subjects (Yonekura et al., 2016).

Oxidative stress is an important contributor to COVID‐19 pathogeneses, and it is associated with activation of the innate immune response and secretion of inflammatory cytokine (Chernyak et al., 2020). SARS‐CoV‐2 infection increased ROS production due to mitochondrial dysfunction. An in vivo study showed that guaraná affects mitochondrial biogenesis positively by upregulating the expression of genes, such as Sirt1, Creb1, Ampka2, Pgc1a, Nrf1, Nrf2, and Ucp1 (Lima, Teixeira, Gambero, & Ribeiro, 2018).

The crosstalk between oxidative stress and activation of proinflammatory cytokines contributes to damage of cellular macromolecules and tissues, as observed in COVID‐19 patients. It is expected that lowering oxidative stress by antioxidants may result in a decreased viral load (Forcados, Muhammad, Oladipo, Makama, & Meseko, 2021). An in vitro study showed that guaraná seed powder extracts were able to inhibit TNF‐ α release in THP‐1 cells (human leukemia monocytic cell line), which is a beneficial effect for treating inflammation‐ related diseases (Machado et al., 2021). The effect of guaraná decreasing IL‐1β, IL‐6, and Ig‐γ levels and increasing IL‐10 levels were observed in an in vitro study with PBMC. The same results were observed in blood cytokine levels in volunteers supplemented with guaraná (da Costa Krewer et al., 2014).

Polyphenols in guaraná seed powder are highly bioaccessible, stable during digestion, and suffer negligible interference from co‐digested macronutrients during intestinal absorption. Hence, the use of extracts is not required to achieve high bioaccessibility and bioavailability of bioactive compounds from guaraná, powder form can be used as a functional food ingredient justifying the potential use of guaraná for a wide range of medicinal purposes (Mendes et al., 2019; Yonekura et al., 2016).

3.6. Final considerations

Until the moment of this review, there is no specific treatment for COVID‐19, other than an attempt to immunize the population with vaccination. Among the patients infected by SARS‐Cov‐2, the elderly are the ones with the worst prognoses since the aging process is associated with dysregulation of the immune system and an increase in the inflammatory‐oxidative state. In addition, they have a nutrient‐poor food intake. However, evidence indicates that one of the keys to dealing with this disease may be directly associated with diet type. A diet that includes more foods rich in nutrients and bioactive compounds can help alleviate and perhaps reduce the symptoms of COVID‐19. In this direction, consumption of the Amazonian fruits açaí, camu‐camu, cocoa, guaraná, Brazil nuts may help to improve COVID‐19 symptoms, as well as reduce the inflammatory‐oxidative state caused by both the infection per se and other morbidities associated with aging. In addition to helping to modulate the immune response. The effect of these fruits is likely to be the synergic effect between its bioactive compounds such as polyphenols, as well as with macro and micronutrients. The consumption of these plants proved to be safe and effective, being possible to purchase either fresh fruit or derived products anywhere in the world.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank National Council for Scientific and Technological (CNPq), and Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Amazonas (FAPEAM), and Support Foundation Institutional Muraki for the financial support.

Manica‐Cattani, M. F. , Hoefel, A. L. , Azzolin, V. F. , Montano, M. A. E. , da Cruz Jung, I. E. , Ribeiro, E. E. , Azzolin, V. F. , & da Cruz, I. B. M. (2022). Amazonian fruits with potential effects on COVID‐19 by inflammaging modulation: A narrative review. Journal of Food Biochemistry, 46, e14472. 10.1111/jfbc.14472

Contributor Information

Maria F. Manica‐Cattani, Email: fernanda18cattani@gmail.com.

Ivana B. M. da Cruz, Email: ibmcruz@hotmail.com.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in PubMed at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.

REFERENCES

- Abou‐Ismail, M. Y. , Diamond, A. , Kapoor, S. , Arafah, Y. , & Nayak, L. (2020). The hypercoagulable state in COVID‐19: Incidence, pathophysiology, and management. Thrombosis Research, 194, 101–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonso Da Costa, P. , Ballus, C. A. , Teixeira Filho, J. , & Teixeira Godoy, H. (2011). Fatty acids profile of pulp and nuts of brazilian fruits Perfil de ácidos graxos de polpa e castanhas de frutas brasileiras. Food Science and Technology, 31, 950–954. [Google Scholar]

- Annweiler, C. , Hanotte, B. , Grandin De l'Eprevier, C. , Sabatier, J. M. , Lafaie, L. , & Célarier, T. (2020). Vitamin D and survival in COVID‐19 patients: A quasi‐experimental study. Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 204, 105771. 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2020.105771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arantes, L. P. , Machado, M. L. , Zamberlan, D. C. , Da Silveira, T. L. , Da Silva, T. C. , da Cruz, I. B. M. , Ribeiro, E. E. , Aschner, M. , & Soares, F. A. A. (2018). Mechanisms involved in anti‐aging effects of guarana (Paullinia cupana) in Caenorhabditis elegans. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 51, e7552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assmann, C. E. , Weis, G. C. C. , da Rosa, J. R. , Bonadiman, B. D. S. R. , De Oliveira Alves, A. , Schetinger, M. R. C. , Ribeiro, E. E. , Morsch, V. M. M. , & Da Cruz, I. B. M. (2021). Amazon‐derived nutraceuticals: Promises to mitigate chronic inflammatory states and neuroinflammation. Neurochemistry International, 148, 105085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevêdo, J. C. S. , Borges, K. C. , Genovese, M. I. , Correia, R. T. P. , & Vattem, D. A. (2015). Neuroprotective effects of dried camu‐camu (Myrciaria dubia HBK McVaugh) residue in C. elegans . Food Research International, 73, 135–141. [Google Scholar]

- Bahadoran, Z. , Mirmiran, P. , & Azizi, F. (2013). Dietary polyphenols as potential nutraceuticals in management of diabetes: A review. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, 12(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrera‐Reyes, P. K. , de Lara, J. C.‐F. , González‐Soto, M. , & Tejero, M. E. (2020). Effects of cocoa‐derived polyphenols on cognitive function in humans. Systematic review and analysis of methodological aspects. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, 75(1), 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bataglion, G. A. , da Silva, F. M. A. , Eberlin, M. N. , & Koolen, H. H. F. (2015). Determination of the phenolic composition from Brazilian tropical fruits by UHPLC–MS/MS. Food Chemistry, 180, 280–287. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.02.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckett, S. T. (Ed.). (2008). Industrial Chocolate Manufacture and Use. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 10.1002/9781444301588 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biazotto, K. R. , de Souza Mesquita, L. M. , Neves, B. V. , Braga, A. R. C. , Tangerina, M. M. P. , Vilegas, W. , Mercadante, A. Z. , & De Rosso, V. V. (2019). Brazilian biodiversity fruits: Discovering bioactive compounds from underexplored sources. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 67(7), 1860–1876. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b05815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges, P. R. S. , Edelenbos, M. , Larsen, E. , Hernandes, T. , Nunes, E. E. , de Barros Vilas Boas, E. V. , & Pires, C. R. F. (2022). The bioactive constituents and antioxidant activities of ten selected Brazilian Cerrado fruits. Food Chemistry: X, 14, 100268. 10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calder, P. C. , Carr, A. C. , Gombart, A. F. , & Eggersdorfer, M. (2020). Optimal nutritional status for a well‐functioning immune system is an important factor to protect against viral infections. Nutrients, 12(4), 1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, B. R. , Duarte, G. B. S. , Reis, B. Z. , & Cozzolino, S. M. F. (2017). Brazil nuts: Nutritional composition, health benefits and safety aspects. Food Research International, 100, 9–18. 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casalino, L. , Gaieb, Z. , Goldsmith, J. A. , Hjorth, C. K. , Dommer, A. C. , Harbison, A. M. , Fogarty, C. A. , Barros, E. P. , Taylor, B. C. , Mclellan, J. S. , Fadda, E. , & Amaro, R. E. (2020). Beyond shielding: The roles of glycans in the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike protein. ACS Central Science, 6(10), 1722–1734. 10.1021/acscentsci.0c01056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro, J. C. , Maddox, J. D. , & Imán, S. A. (2018). Camu‐camu— Myrciaria dubia (Kunth) McVaugh. In Exotic fruits (pp. 97–105). Elsevier. 10.1016/b978-0-12-803138-4.00014-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaari, A. , Bendriss, G. , Zakaria, D. , & McVeigh, C. (2020). Importance of dietary changes during the coronavirus pandemic: How to upgrade your immune response. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, S. K. , Alasalvar, C. , & Shahidi, F. (2019). Superfruits: Phytochemicals, antioxidant efficacies, and health effects–A comprehensive review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 59(10), 1580–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channappanavar, R. , & Perlman, S. (2017). Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: Causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. Seminars in Immunopathology, 39(5), 529–539. 10.1007/s00281-017-0629-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J. , Kelley, W. J. , & Goldstein, D. R. (2020). Role of aging and the immune response to respiratory viral infections: Potential implications for COVID‐19. The Journal of Immunology, 205(2), 313–320. 10.4049/jimmunol.2000380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. , Hu, C. , Hood, M. , Zhang, X. , Zhang, L. , Kan, J. , & Du, J. (2020). A novel combination of vitamin c, curcumin and glycyrrhizic acid potentially regulates immune and inflammatory response associated with coronavirus infections: A perspective from system biology analysis. Nutrients, 12(4), 1193. 10.3390/nu12041193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y. , Klein, S. L. , Garibaldi, B. T. , Li, H. , Wu, C. , Osevala, N. M. , Li, T. , Margolick, J. B. , Pawelec, G. , & Leng, S. X. (2021). Aging in COVID‐19: Vulnerability, immunity and intervention. Ageing Research Reviews, 65, 101205. 10.1016/j.arr.2020.101205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernyak, B. V. , Popova, E. N. , Prikhodko, A. S. , Grebenchikov, O. A. , Zinovkina, L. A. , & Zinovkin, R. A. (2020). COVID‐19 and oxidative stress. Biochemistry (Moscow), 85(12–13), 1543–1553. 10.1134/S0006297920120068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobre, A. F. , Surek, M. , Vilhena, R. O. , Böger, B. , Fachi, M. M. , Momade, D. R. , Tonin, F. S. , Sarti, F. M. , & Pontarolo, R. (2021). Influence of foods and nutrients on COVID‐19 recovery: A multivariate analysis of data from 170 countries using a generalized linear model. Clinical Nutrition, S0261‐5614(21), 00157–6. 10.1016/j.clnu.2021.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conceição, N. , Albuquerque, B. R. , Pereira, C. , Corrêa, R. C. G. , Lopes, C. B. , Calhelha, R. C. , Alves, M. J. , Barros, L. , & Ferreira, I. C. F. R. (2019). By‐Products of Camu‐Camu [Myrciaria dubia (Kunth) McVaugh] as Promising Sources of Bioactive High Added‐Value Food Ingredients: Functionalization of Yogurts. Molecules, 25(1), 70. 10.3390/molecules25010070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cândido, T. L. N. , Silva, M. R. , & Agostini‐Costa, T. S. (2015). Bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of Buriti (Mauritia flexuosa Lf) from the Cerrado and Amazon biomes. Food Chemistry, 177, 313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa Krewer, C. , Ribeiro, E. E. , Ribeiro, E. A. M. , Moresco, R. N. , de Ugalde Marques da Rocha, M. I. , dos Santos Montagner, G. F. F. , Machado, M. M. , Viegas, K. , Brito, E. , & da Cruz, I. B. M. (2011). Habitual intake of guaraná and metabolic morbidities: An epidemiological study of an elderly Amazonian population. Phytotherapy Research, 25(9), 1367–1374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Costa Krewer, C. , Suleiman, L. , Duarte, M. M. M. F. , Ribeiro, E. E. , Mostardeiro, C. P. , Montano, M. A. E. , Ugalde Marques da Rocha, M. I. D. , Algarve, T. D. , Bresciani, G. , & da Cruz, I. B. M. (2014). Guaraná, a supplement rich in caffeine and catechin, modulates cytokines: Evidence from human in vitro and in vivo protocols. European Food Research and Technology, 239(1), 49–57. [Google Scholar]

- da Silva, F. C. , Arruda, A. , Ledel, A. , Dauth, C. , Romão, N. F. , Viana, R. N. , De Barros Falcão Ferraz, A. , Picada, J. N. , & Pereira, P. (2012). Antigenotoxic effect of acute, subacute and chronic treatments with Amazonian camu‐camu (Myrciaria dubia) juice on mice blood cells. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 50(7), 2275–2281. 10.1016/j.fct.2012.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Brito, E. S. , García, N. H. P. , Gallão, M. I. , Cortelazzo, A. L. , Fevereiro, P. S. , & Braga, M. R. (2001). Structural and chemical changes in cocoa (Theobroma cacao L) during fermentation, drying and roasting. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 81(2), 281–288. [Google Scholar]

- De Faria Coelho‐Ravagnani, C. , Corgosinho, F. C. , Sanches, F. L. F. Z. , Prado, C. M. M. , Laviano, A. , & Mota, J. F. (2021). Dietary recommendations during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Nutrition Reviews, 79(4), 382–393. 10.1093/nutrit/nuaa067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Liz, S. , Cardoso, A. L. , Copetti, C. L. K. , de Fragas Hinnig, P. , Vieira, F. G. K. , da Silva, E. L. , Schulz, M. , Fett, R. , Micke, G. A. , & Di Pietro, P. F. (2020). Açaí (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) and juçara (Euterpe edulis Mart.) juices improved HDL‐c levels and antioxidant defense of healthy adults in a 4‐week randomized cross‐over study. Clinical Nutrition, 39(12), 3629–3636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Moura, R. S. , Pires, K. M. P. , Ferreira, T. S. , Lopes, A. A. , Nesi, R. T. , Resende, A. C. , Sousa, P. J. C. , da Silva, A. J. R. , Porto, L. C. , & Valenca, S. S. (2011). Addition of açaí (Euterpe oleracea) to cigarettes has a protective effect against emphysema in mice. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 49(4), 855–863. 10.1016/j.fct.2010.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Do, N. Q. , Zheng, S. , Park, B. , Nguyen, Q. T. N. , Choi, B. R. , Fang, M. , Kim, M. , Jeong, J. , Choi, J. , Yang, S. J. , & Yi, T. H. (2021). Camu‐camu fruit extract inhibits oxidative stress and inflammatory responses by regulating NFAT and Nrf2 signaling pathways in high glucose‐induced human keratinocytes. Molecules, 26(11), 3174. 10.3390/molecules26113174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donders, I. , & Barriocanal, C. (2020). The influence of markets on the nutrition transition of hunter‐gatherers: Lessons from the Western Amazon. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6307. 10.3390/ijerph17176307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earling, M. , Beadle, T. , & Niemeyer, E. D. (2019). Açai berry (Euterpe oleracea) dietary supplements: Variations in anthocyanin and flavonoid concentrations, phenolic contents, and antioxidant properties. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition, 74(3), 421–429. 10.1007/s11130-019-00755-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efraim, P. , Alves, A. B. , & Jardim, D. C. P. (2011). Revisão: Polifenóis em cacau e derivados: Teores, fatores de variação e efeitos na saúde. Brazilian Journal of Food Technology, 14(3), 181–201. 10.4260/bjft2011140300023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flammer, A. J. , Hermann, F. , Sudano, I. , Spieker, L. , Hermann, M. , Cooper, K. A. , Serafini, M. , Lüscher, T. F. , Ruschitzka, F. , Noll, G. , & Corti, R. (2007). Dark chocolate improves coronary vasomotion and reduces platelet reactivity. Circulation, 116(21), 2376–2382. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.713867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forcados, G. E. , Muhammad, A. , Oladipo, O. O. , Makama, S. , & Meseko, C. A. (2021). Metabolic implications of oxidative stress and inflammatory process in SARS‐CoV‐2 pathogenesis: Therapeutic potential of natural antioxidants. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 11, 654813. 10.3389/fcimb.2021.654813 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franceschi, C. , Garagnani, P. , Morsiani, C. , Conte, M. , Santoro, A. , Grignolio, A. , Monti, D. , Capri, M. , & Salvioli, S. (2018). The continuum of aging and age‐related diseases: Common mechanisms but different rates. Frontiers in Medicine, 5, 61. 10.3389/fmed.2018.00061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmés, S. , Serra, F. , & Palou, A. (2020). Current state of evidence: Influence of nutritional and nutrigenetic factors on immunity in the COVID‐19 pandemic framework. Nutrients, 12(9), 1–33. 10.3390/nu12092738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García, L. F. (2020). Immune response, inflammation, and the clinical spectrum of COVID‐19. Frontiers in Immunology, 11, 1441. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg, M. L. , Leitch, J. , Blake, R. J. , & Garg, R. (2006). Long‐chain n− 3 polyunsaturated fatty acid incorporation into human atrium following fish oil supplementation. Lipids, 41(12), 1127–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraets, L. , Moonen, H. J. J. , Wouters, E. F. M. , Bast, A. , & Hageman, G. J. (2006). Caffeine metabolites are inhibitors of the nuclear enzyme poly (ADP‐ribose) polymerase‐1 at physiological concentrations. Biochemical Pharmacology, 72(7), 902–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Y. R. , Cao, Q. D. , Hong, Z. S. , Tan, Y. Y. , Chen, S. D. , Jin, H. J. , Tan, K. , Sen Wang, D. Y. , & Yan, Y. (2020). The origin, transmission and clinical therapies on coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak‐ a n update on the status. Military Medical Research, 7(1), 11. 10.1186/s40779-020-00240-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halliwell, B. (1999). Vitamin C: Poison, prophylactic or panacea? Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 24(7), 255–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hathaway, D. , Pandav, K. , Patel, M. , Riva‐Moscoso, A. , Singh, B. M. , Patel, A. , Min, Z. C. , Singh‐Makkar, S. , Sana, M. K. , Sanchez‐Dopazo, R. , Desir, R. , Fahem, M. M. M. , Manella, S. , Rodriguez, I. , Alvarez, A. , & Abreu, R. (2020). Omega 3 fatty acids and COVID‐19: A comprehensive review. Infection and chemotherapy, 52(4), 478–495. 10.3947/IC.2020.52.4.478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heptinstall, S. , May, J. , Fox, S. , Kwik‐Uribe, C. , & Zhao, L. (2006). Cocoa flavanols and platelet and leukocyte function: Recent in vitro and ex vivo studies in healthy adults. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology, 47, S197–S205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoang, X. , Shaw, G. , Fang, W. , & Han, B. (2020). Possible application of high‐dose vitamin C in the prevention and therapy of coronavirus infection. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance, 23, 256–262. 10.1016/j.jgar.2020.09.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idrees, M. , Khan, S. , Memon, N. H. , & Zhang, Z. (2020). Effect of the phytochemical agents against the SARS‐CoV and some of them selected for application to COVID‐19: A mini‐review. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, 22(4), 444–450. 10.2174/1389201021666200703201458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infante, J. , Rosalen, P. L. , Lazarini, J. G. , Franchin, M. , & de Alencar, S. M. (2016). Antioxidant and anti‐inflammatory activities of unexplored Brazilian native fruits. PLoS One, 11(4), e0152974. 10.1371/journal.pone.0152974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, T. , Komoda, H. , Uchida, T. , & Node, K. (2008). Tropical fruit camu‐camu (Myrciaria dubia) has anti‐oxidative and anti‐inflammatory properties. Journal of Cardiology, 52(2), 127–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Z. , Du, X. , Xu, Y. , Deng, Y. , Liu, M. , Zhao, Y. , Zhang, B. , Li, X. , Zhang, L. , Peng, C. , Duan, Y. , Yu, J. , Wang, L. , Yang, K. , Liu, F. , Jiang, R. , Yang, X. , You, T. , Liu, X. , … Yang, H. (2020). Structure of Mpro from SARS‐CoV‐2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature, 582(7811), 289–293. 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- John, J. A. , & Shahidi, F. (2010). Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa). Journal of Functional Foods, 2(3), 196–209. 10.1016/J.JFF.2010.04.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- John, N. A. , John, J. , Kamblec, P. , Singhal, A. , Daulatabad, V. , & Vamshidhar, I. S. (2021). Patients with sticky platelet syndrome, sickle cell disease and Glanzmann syndrome may promulgate severe thrombosis if infected with Covid‐19. Maedica, 16(2), 268–273. 10.26574/maedica.2021.16.2.268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin, M. , & Greten, F. R. (2005). NF‐κB: Linking inflammation and immunity to cancer development and progression. Nature Reviews Immunology, 5(10), 749–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz, D. L. , Doughty, K. , & Ali, A. (2011). Cocoa and chocolate in human health and disease. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling, 15(10), 2779–2811. 10.1089/ars.2010.3697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. , Simbo, S. Y. , Fang, C. , McAlister, L. , Roque, A. , Banerjee, N. , Talcott, S. T. , Zhao, H. , Kreider, R. B. , & Mertens‐Talcott, S. U. (2018). Acai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) beverage consumption improves biomarkers for inflammation but not glucose‐or lipid‐metabolism in individuals with metabolic syndrome in a randomized, double‐blinded, placebo‐controlled clinical trial. Food & Function, 9(6), 3097–3103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. , Lee, K. W. , & Lee, H. J. (2011). Cocoa (Theobroma cacao) seeds and phytochemicals in human health. In Nuts and seeds in health and disease prevention (pp. 351–360). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhnlein, H. V. (2015). Food system sustainability for health and well‐being of indigenous peoples. Public Health Nutrition, 18(13), 2415–2424. 10.1017/S1368980014002961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langley, P. C. , Pergolizzi, J. V. , Taylor, R. , & Ridgway, C. (2015). Antioxidant and associated capacities of camu camu (Myrciaria dubia): A systematic review. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 21(1), 8–14. 10.1089/acm.2014.0130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudisi, F. , Sambucci, M. , & Pioli, C. (2011). Poly (ADP‐ribose) polymerase‐1 (PARP‐1) as immune regulator. Endocrine, Metabolic & Immune Disorders‐Drug Targets, 11(4), 326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. , Fan, Y. , Lai, Y. , Han, T. , Li, Z. , Zhou, P. , Pan, P. , Wang, W. , Hu, D. , & Liu, X. (2020). Coronavirus infections and immune responses. Journal of Medical Virology, 92(4), 424–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima, N. D. S. , Teixeira, L. , Gambero, A. , & Ribeiro, M. L. (2018). Guarana (Paullinia cupana) stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis in mice fed high‐fat diet. Nutrients, 10(2), 165. 10.3390/nu10020165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López‐Lluch, G. , Hernández‐Camacho, J. D. , Fernández‐Ayala, D. J. M. , & Navas, P. (2018). Mitochondrial dysfunction in metabolism and ageing: Shared mechanisms and outcomes? Biogerontology, 19(6), 461–480. 10.1007/s10522-018-9768-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado, K. N. , de Paula Barbosa, A. , de Freitas, A. A. , Alvarenga, L. F. , de Pádua, R. M. , Gomes Faraco, A. A. , Braga, F. C. , Vianna‐Soares, C. D. , & Castilho, R. O. (2021). TNF‐α inhibition, antioxidant effects and chemical analysis of extracts and fraction from Brazilian guaraná seed powder. Food Chemistry, 355, 129563. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia Ribeiro, E. A. , Ribeiro, E. E. , Viegas, K. , Teixeira, F. , dos Santos Montagner, G. F. F. , Mota, K. M. , Barbisan, F. , da Cruz, I. B. M. , & de Paz, J. A. (2013). Functional, balance and health determinants of falls in a free living community Amazon riparian elderly. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 56(2), 350–357. 10.1016/j.archger.2012.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldaner, D. R. , Pellenz, N. L. , Barbisan, F. , Azzolin, V. F. , Mastella, M. H. , Teixeira, C. F. , Duarte, T. , Maia‐Ribeiro, E. A. , da Cruz, I. B. M. , & Duarte, M. M. M. F. (2020). Interaction between low‐level laser therapy and guarana (Paullinia cupana) extract induces antioxidant, anti‐inflammatory, and anti‐apoptotic effects and promotes proliferation in dermal fibroblasts. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology, 19(3), 629–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M. A. , Goya, L. , & Ramos, S. (2017). Protective effects of tea, red wine and cocoa in diabetes. Evidences from human studies. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 109, 302–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez‐Pinilla, E. , Oñatibia‐Astibia, A. , & Franco, R. (2015). The relevance of theobromine for the beneficial effects of cocoa consumption. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 6, 30. 10.3389/fphar.2015.00030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendes, T. M. N. , Murayama, Y. , Yamaguchi, N. , Sampaio, G. R. , Fontes, L. C. B. , da Silva Torres, E. A. F. , Tamura, H. , & Yonekura, L. (2019). Guaraná (Paullinia cupana) catechins and procyanidins: Gastrointestinal/colonic bioaccessibility, Caco‐2 cell permeability and the impact of macronutrients. Journal of Functional Foods, 55, 352–361. [Google Scholar]

- Milani, G. P. , Macchi, M. , & Guz‐Mark, A. (2021). Vitamin C in the treatment of COVID‐19. Nutrients, 13(4), 1172. 10.3390/nu13041172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Fernández‐Ayala, D. J. , Navas, P. , & López‐Lluch, G. (2020). Age‐related mitochondrial dysfunction as a key factor in COVID‐19 disease. Experimental Gerontology, 142, 111147. 10.1016/j.exger.2020.111147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motamayor, J. C. , Lachenaud, P. , Da Silva, E. , Mota, J. W. , Loor, R. , Kuhn, D. N. , Brown, J. S. , & Schnell, R. J. (2008). Geographic and genetic population differentiation of the Amazonian chocolate tree (Theobroma cacao L). PLoS One, 3(10), e3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, L. , & Di Benedetto, S. (2021). How immunosenescence and inflammaging may contribute to hyperinflammatory syndrome in covid‐19. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(22), 12539. 10.3390/ijms222212539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabavi, S. , Sureda, A. , Daglia, M. , Rezaei, P. , & Nabavi, S. (2015). Anti‐Oxidative Polyphenolic Compounds of Cocoa. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, 16(10), 891–901. 10.2174/1389201016666150610160652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngwa, W. , Kumar, R. , Thompson, D. , Lyerly, W. , Moore, R. , Reid, T. E. , Lowe, H. , & Toyang, N. (2020). Potential of flavonoid‐inspired phytomedicines against COVID‐19. Molecules, 25(11), 2707. 10.3390/molecules25112707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olagnier, D. , Farahani, E. , Thyrsted, J. , Blay‐Cadanet, J. , Herengt, A. , Idorn, M. , Hait, A. , Hernaez, B. , Knudsen, A. , & Iversen, M. B. (2020). SARS‐CoV2‐mediated suppression of NRF2‐signaling reveals potent antiviral and anti‐inflammatory activity of 4‐octyl‐itaconate and dimethyl fumarate. Nature Communications, 11(1), 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oñatibia‐Astibia, A. , Franco, R. , & Martínez‐Pinilla, E. (2017). Health benefits of methylxanthines in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 61(6), 1600670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padayatty, S. J. , Katz, A. , Wang, Y. , Eck, P. , Kwon, O. , Lee, J.‐H. , Chen, S. , Corpe, C. , Dutta, A. , & Dutta, S. K. (2003). Vitamin C as an antioxidant: Evaluation of its role in disease prevention. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 22(1), 18–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagliarussi, R. S. , Freitas, L. A. P. , & Bastos, J. K. (2002). A quantitative method for the analysis of xanthine alkaloids in Paullinia cupana (guarana) by capillary column gas chromatography. Journal of Separation Science, 25(5–6), 371–374. [Google Scholar]

- Pala, D. , Barbosa, P. O. , Silva, C. T. , de Souza, M. O. , Freitas, F. R. , Volp, A. C. P. , Maranhão, R. C. , & de Freitas, R. N. (2018). Açai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) dietary intake affects plasma lipids, apolipoproteins, cholesteryl ester transfer to high‐density lipoprotein and redox metabolism: A prospective study in women. Clinical Nutrition, 37(2), 618–623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez‐Sanchez, I. , Maya, L. , Ceballos, G. , & Villarreal, F. (2010). Fluorescent detection of (−)‐epicatechin in microsamples from cacao seeds and cocoa products: Comparison with Folin–Ciocalteu method. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 23(8), 790–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramiro‐Puig, E. , & Castell, M. (2009). Cocoa: antioxidant and immunomodulator. British Journal of Nutrition, 101(7), 931–940. 10.1017/s0007114508169896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos, S. , Martín, M. A. , & Goya, L. (2017). Effects of cocoa antioxidants in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Antioxidants, 6(4), 84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roggia, I. , Dalcin, A. J. F. , de Souza, D. , Machado, A. K. , de Souza, D. V. , da Cruz, I. B. M. , Ribeiro, E. E. , Ourique, A. F. , & Gomes, P. (2020). Guarana: Stability‐indicating RP‐HPLC method and safety profile using microglial cells. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 94, 103629. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, Q. , Yang, K. , Wang, W. , Jiang, L. , & Song, J. (2020). Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID‐19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Medicine, 46, 846–848. 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rufino, M. S. M. , Alves, R. E. , Fernandes, F. A. N. , & Brito, E. S. (2011). Free radical scavenging behavior of ten exotic tropical fruits extracts. Food Research International, 44(7), 2072–2075. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, A. L. , & Macedo, G. A. (2018). Health and technological aspects of methylxanthines and polyphenols from guarana: A review. Journal of Functional Foods, 47, 457–468. [Google Scholar]

- Schott, K. L. , Assmann, C. E. , Teixeira, C. F. , Boligon, A. A. , Waechter, S. R. , Duarte, F. A. , Ribeiro, E. E. , & da Cruz, I. B. M. (2018). Brazil nut improves the oxidative metabolism of superoxide‐hydrogen peroxide chemically‐imbalanced human fibroblasts in a nutrigenomic manner. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 121, 519–526. 10.1016/j.fct.2018.09.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serra, J. L. , da Cruz Rodrigues, A. M. , de Freitas, R. A. , de Almeida Meirelles, A. J. , Darnet, S. H. , & da Silva, L. H. M. (2019). Alternative sources of oils and fats from Amazonian plants: Fatty acids, methyl tocols, total carotenoids and chemical composition. Food Research International, 116, 12–19. 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.12.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva Junior, E. C. , Wadt, L. H. O. , Silva, K. E. , Lima, R. M. B. , Batista, K. D. , Guedes, M. C. , Carvalho, G. S. , Carvalho, T. S. , Reis, A. R. , Lopes, G. , & Guilherme, L. R. G. (2017). Natural variation of selenium in Brazil nuts and soils from the Amazon region. Chemosphere, 188, 650–658. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.08.158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit, H. J. , Gaffan, E. A. , & Rogers, P. J. (2004). Methylxanthines are the psycho‐pharmacologically active constituents of chocolate. Psychopharmacology, 176(3), 412–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souza, F. das C. do A. , Silva, E. P. , & Aguiar, J. P. L. (2020). Vitamin characterization and volatile composition of camu‐camu (Myrciaria dubia (HBK) McVaugh, Myrtaceae) at different maturation stages. Food Science and Technology, 41(4), 961–966. 10.1590/fst.27120 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg, F. M. , Bearden, M. M. , & Keen, C. L. (2003). Cocoa and chocolate flavonoids: Implications for cardiovascular health. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 103(2), 215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockler‐Pinto, M. B. , Mafra, D. , Farage, N. E. , Boaventura, G. T. , & Cozzolino, S. M. F. (2010). Effect of Brazil nut supplementation on the blood levels of selenium and glutathione peroxidase in hemodialysis patients. Nutrition, 26(11–12), 1065–1069. 10.1016/j.nut.2009.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockler‐Pinto, M. B. , Mafra, D. , Moraes, C. , Lobo, J. , Boaventura, G. T. , Farage, N. E. , Silva, W. S. , Cozzolino, S. F. , & Malm, O. (2014). Brazil Nut (Bertholletia excelsa, H.B.K.) Improves Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Biomarkers in Hemodialysis Patients. Biological Trace Element Research, 158(1), 105–112. 10.1007/s12011-014-9904-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, C. D. , Chisholm, A. , McLachlan, S. K. , & Campbell, J. M. (2008). Brazil nuts: An effective way to improve selenium status. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 87(2), 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traber, M. G. , & Stevens, J. F. (2011). Vitamins C and E: Beneficial effects from a mechanistic perspective. Free Radical Biology and Medicine, 51(5), 1000–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veloso, C. F. , Machado, A. K. , Cadoná, F. C. , Azzolin, V. F. , Cruz, I. B. M. , & Silveira, A. F. (2018). Neuroprotective effects of guarana (Paullinia cupana Mart.) against vincristine in vitro exposure. The Journal of Prevention of Alzheimer's Disease, 5(1), 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, D. , Lewis, E. D. , Pae, M. , & Meydani, S. N. (2019). Nutritional modulation of immune function: Analysis of evidence, mechanisms, and clinical relevance. Frontiers in Immunology, 9, 3160. 10.3389/fimmu.2018.03160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, K. , Wei, Y. , Giunta, S. , Zhou, M. , & Xia, S. (2021). Do inflammaging and coagul‐aging play a role as conditions contributing to the co‐occurrence of the severe hyper‐inflammatory state and deadly coagulopathy during COVID‐19 in older people? Experimental Gerontology, 151, 111423. 10.1016/j.exger.2021.111423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi, K. K. D. L. , Pereira, L. F. R. , Lamarão, C. V. , Lima, E. S. , & Da Veiga‐Junior, V. F. (2015). Amazon acai: Chemistry and biological activities: A review. Food Chemistry, 179, 137–151. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.01.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. (2009). Brazil nuts and associated health benefits: A review. LWT‐Food Science and Technology, 42(10), 1573–1580. 10.1016/j.lwt.2009.05.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yazawa, K. , Suga, K. , Honma, A. , Shirosaki, M. , & Koyama, T. (2011). Anti‐inflammatory effects of seeds of the tropical fruit camu‐camu (Myrciaria dubia). Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology, 57(1), 104–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yañez, O. , Osorio, M. I. , Areche, C. , Vasquez‐Espinal, A. , Bravo, J. , Sandoval‐Aldana, A. , Pérez‐Donoso, J. M. , González‐Nilo, F. , Matos, M. J. , Osorio, E. , García‐Beltrán, O. , & Tiznado, W. (2021). Theobroma cacao L. compounds: Theoretical study and molecular modeling as inhibitors of main SARS‐CoV‐2 protease. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy, 140, 111764. 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, Q. , Wang, B. , & Mao, J. (2020). The pathogenesis and treatment of the ‘cytokine storm’ in COVID‐19. Journal of Infection, 80(6), 607–613. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yonekura, L. , Martins, C. A. , Sampaio, G. R. , Monteiro, M. P. , César, L. A. M. H. , Mioto, B. M. , Mori, C. S. , Mendes, T. M. N. , Ribeiro, M. L. , Arçari, D. P. , & Da Silva Torres, E. A. F. (2016). Bioavailability of catechins from guaraná (Paullinia cupana) and its effect on antioxidant enzymes and other oxidative stress markers in healthy human subjects. Food and Function, 7(7), 2970–2978. 10.1039/c6fo00513f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yunis‐Aguinaga, J. , Fernandes, D. C. , Eto, S. F. , Claudiano, G. S. , Marcusso, P. F. , Marinho‐Neto, F. A. , Fernandes, J. B. K. , de Moraes, F. R. , & de Moraes, J. R. E. (2016). Dietary camu camu, Myrciaria dubia, enhances immunological response in Nile tilapia . Fish & Shellfish Immunology, 58, 284–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuyama, K. , Aguiar, J. P. L. , & Yuyama, L. K. O. (2002). Camu‐camu: um fruto fantástico como fonte de vitamina C1. Acta Amazonica, 32(1), 169–174. 10.1590/1809-43922002321174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zabetakis, I. , Lordan, R. , Norton, C. , & Tsoupras, A. (2020). COVID‐19: The inflammation link and the role of nutrition in potential mitigation. Nutrients, 12(5), 1466. 10.3390/nu12051466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanatta, C. F. , & Mercadante, A. Z. (2007). Carotenoid composition from the Brazilian tropical fruit camu–camu (Myrciaria dubia). Food Chemistry, 101(4), 1526–1532. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y. , Liu, X. , Le, W. , Xie, L. , Li, H. , Wen, W. , Wang, S. , Ma, S. , Huang, Z. , Ye, J. , Shi, W. , Ye, Y. , Liu, Z. , Song, M. , Zhang, W. , Han, J. D. J. , Belmonte, J. C. I. , Xiao, C. , Qu, J. , … Su, W. (2020). A human circulating immune cell landscape in aging and COVID‐19. Protein and Cell, 11(10), 740–770. 10.1007/s13238-020-00762-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, P. , Yang, X. L. , Wang, X. G. , Hu, B. , Zhang, L. , Zhang, W. , Si, H. R. , Zhu, Y. , Li, B. , Huang, C. L. , Chen, H. D. , Chen, J. , Luo, Y. , Guo, H. , Jiang, R.‐D. , Liu, M. Q. , Chen, Y. , Shen, X. R. , Wang, X. , … Shi, Z. L. (2020). A pneumonia outbreak associated with a new coronavirus of probable bat origin. Nature, 579(7798), 270–273. 10.1038/s41586-020-2012-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y. , Schneider, D. J. , & Blackburn, M. R. (2009). Adenosine signaling and the regulation of chronic lung disease. Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 123(1), 105–116. 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2009.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y. , & Xie, D. Y. (2020). Docking characterization and in vitro inhibitory activity of Flavan‐3‐ols and dimeric Proanthocyanidins against the Main protease activity of SARS‐Cov‐2. Frontiers in Plant Science, 11, 601316. 10.3389/fpls.2020.601316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in PubMed at https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/.