Abstract

Context:

Synthetic cannabinoids (SCs) are a structurally heterogenous synthetic class of drugs of abuse. The objective was to describe the incidence of acute respiratory failure in Emergency Department (ED) patients with confirmed SC exposure, and to investigate the association between SC overdose with respiratory failure compared to non-SC overdose.

Methods:

This was an observational cohort of ED patients ≥18 years with suspected cannabinoid overdose between 2015 and 2020 at two tertiary-care hospitals. Patient serum was analyzed via liquid chromatography/quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry using a library with >800 drugs including novel psychoactive substances. The primary outcome was acute respiratory failure.

Discussion:

Of 83 patients with suspected cannabinoid overdose, there were 29 confirmed SC overdoses: 5 F-MDMB-PICA (n = 18) and its metabolite 5OH-MDMB-PICA (n = 16), ADB-FUBINACA (n = 4), AB-CHIMINACA (n = 4), AB-FUBINACA (n = 1), AB-PINACA (n = 1), MDMB-4en-PINACA (n = 1), and 4F-MDMB-BINACA (n = 1). Overall, incidence of acute respiratory failure was 31.3% (95%CI 21.6–42.4). Compared to non-SC overdose, confirmed SC overdose was significantly associated with respiratory failure (25.0% SC vs. 4.2% non-SC, p = 0.05).

Conclusion:

This study demonstrates that SCs are associated with respiratory failure. Since respiratory depression is a potentially lethal adverse effect of SC overdose, future research is warranted.

Keywords: Synthetic cannabinoids, synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists, SCRAs, respiratory failure, naloxone

Introduction

Synthetic cannabinoids (SCs) are a structurally heterogenous synthetic class of drugs of abuse. While the United States has used legislative and regulatory methods to ban specific compounds and their analogues, this drug class remains widely-available. SCs are also known as Synthetic Cannabinoid Receptor Agonists (SCRAs), and have brand names such as ‘Spice’ and ‘K2.’ SCs differ from cannabis in several ways; SC binding affinity for the CB1 receptor ranges from similar to 90 times higher than Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the primary psychoactive compound in cannabis, with full receptor activation [1]. SC’s lack phytocannabinoids that modulate effects at CB1, such as cannabidiol, and binding of non-CB1 receptors varies among SCs.

Various clinical effects have been attributed to SCs, and respiratory depression has been suggested but poorly described. Previous accounts are limited to case reports or uncontrolled case series, some of which have analytical confirmation [2]. The objective was to describe the incidence of acute respiratory failure in Emergency Department (ED) patients with confirmed SC exposure, and to investigate the association between SC overdose with respiratory failure compared to non-SC overdose.

Methods

This was a prospective observational cohort of ED patients ≥18 years with suspected cannabinoid overdose between 2015 and 2020 at two tertiary-care hospitals. All overdoses were prospectively screened, and were excluded if cannabinoid drugs were not suspected based on chart review, or if waste serum was unavailable. Samples were stored at −80 °C prior to analysis, and serum was analyzed via liquid chromatography/quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry using a library with >800 drugs including novel psychoactive substances, 258 parent SC drugs, and 30 SC metabolites. Trained abstractors performed chart review using a standardized tool.

The primary outcome was acute respiratory failure, defined as a composite of (A) intubation, (B) non-invasive positive pressure ventilation, or (C) naloxone administration. Secondary outcomes were adverse cardiovascular events, ED disposition, and in-hospital mortality. Incidence of clinical outcomes were calculated with a 95% confidence interval, and compared using chi-squared test with 5% alpha. This study was approved by the local institutional review board with waiver of consent.

Results

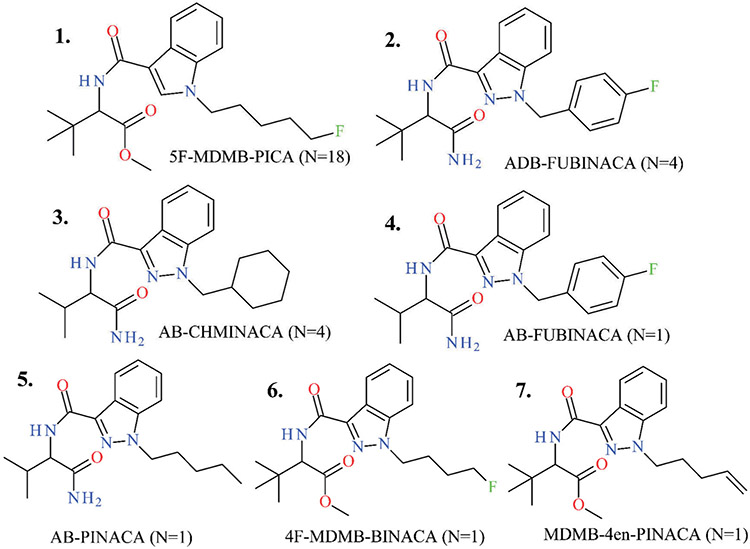

Of 83 total ED patients with suspected cannabinoid overdose, there were 29 confirmed SC overdoses (including 12 sedative and 6 opioid co-exposures), and 54 cases in which SCs were not detected. Confirmed SC drugs are shown in Figure 1 as: 5 F-MDMB-PICA (n = 18) and its metabolite 5OH-MDMB-PICA (n = 16), ADB-FUBINACA (n = 4), AB-CHIMINACA (n = 4), AB-FUBINACA (n = 1), AB-PINACA (n = 1), MDMB-4en-PINACA (n = 1), and 4 F-MDMB-BINACA (n = 1).

Figure 1.

Confirmed Synthetic Cannabinoid drugs in this cohort (N).

ED disposition overall among the 83 cases was 8.4% intensive care unit (ICU), 19.3% non-ICU hospitalization, 6.0% psychiatric admission, and 66.2% discharged. Overall, incidence of acute respiratory failure was 31.3% (95%CI 21.6–42.4), cardiovascular events occurred in 2.4% (95%CI 0.3–8.4), and there were no deaths. Excluding patients with opioid/sedative co-exposure, confirmed SC overdose was significantly associated with respiratory failure (25.0% SC vs. 4.2% non-SC, p = 0.050). Naloxone was administered to 7 of 29 patients with confirmed SC overdose (dose range 0.4–6.0 mg), only 2 of whom had opioid/sedative co-exposure, and was re-administered in two patients, one of whom was confirmed as lacking opioid co-exposure.

Discussion

In this cohort, analytically confirmed SC overdose was significantly associated with acute respiratory failure in patients without opioid/sedative co-exposures, compared with reported cannabinoid overdoses lacking confirmed SC analytes. The P value of 0.05 for this association is fragile, and a larger sample may confirm or refute this finding. While this study confirms the association of SCs with respiratory failure, it has been described previously [3-7]. A prior case series of 22 patients using SCs found that 23% required mechanical ventilation; 7 of these patients had analytically confirmed SC exposures, and co-exposure to other drugs was not recorded [3]. Based on this case series and others, it is clear that many, if not most SC users do not experience respiratory depression; it remains unclear whether the association between SCs and acute respiratory failure is related to specific drug, dose, or patient factors.

The mechanisms of SC respiratory depression are unclear, and may relate to 1) SC effects on CB1, 2) SC effects on non-CB1 receptors, or 3) Interaction between the endocannabinoid and endogenous opioid systems. SC CB1 agonism has been implicated as the mechanism for respiratory depression in several animal studies, including a rat model in which respiratory changes were blocked by a CB1 antagonist, and this was likely centrally mediated [8]. Another possible mechanism is an unclear interaction between the endocannabinoid and endogenous opioid systems. As evidence for these interactions, opioid antagonists have been found to reduce the reinforcing effects of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in monkeys, and to reduce daily cannabis use in regular users [9,10]. Translating animal findings of cannabinoid respiratory effects to humans must be with the understanding that SC potency varies significantly compared to phytocannabinoids, and that assessing respiratory depression in anesthetized animals may not translate to non-anesthetized humans.

Use of naloxone for cannabinoid respiratory depression has been reported in individual cases with mixed results [5-7]. Naloxone has also rarely been used with mixed results as an antidote for overdose of other non-opioid drugs, such as clonidine, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor overdose, and valproate, with unclear benefit and mechanisms. This study was not designed to evaluate efficacy of naloxone for SC overdose, but in this cohort it was used in patients with confirmed SC overdose and no opioid/sedative co-exposure. If naloxone efficacy is found in larger cohorts, it may warrant further study as a treatment for SC-related respiratory depression.

Limitations of this study include convenience sampling of waste specimens, a relatively small sample size, and ethanol was not measured as a potential sedative.

In conclusion, confirmed SC overdose was associated with acute respiratory failure in this sample, which in some cases prompted clinicians to administer naloxone. Given this recreational drug class is repeatedly restricted by public policy as new structural analogues are created, and given respiratory depression is a potentially lethal adverse effect, future research should further examine the association and mechanism of synthetic cannabinoid respiratory failure.

Table 1.

Description of disposition, outcomes, and analytes detected for sedatives and opioids.

| SC confirmed (N = 29) | SC not detected (N = 54) | Total (N = 83) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sedatives detected | 41.4% (N = 12) | 38.9% (N = 21) | 39.8% (N = 33) |

| Sedative analytes detected | Antipsychotics: aripiprazole, haloperidol, olanzapine, risperidone, | Antipsychotics: aripiprazole, chlorpromazine, haloperidol, risperidone, quetiapine | |

| Benzodiazepines: alprazolam, clonazepam, diazepam, midazolam | Benzodiazepines: alprazolam, chlordiazepoxide, clonazepam, lorazepam, midazolam, oxazepam, temazepam | ||

| Other: trazodone | |||

| Other: doxylamine, diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, trazodone, zolpidem | |||

| Opioids detected | 17.2% (N = 5) | 31.5% (N = 17) | 26.5% (N = 22) |

| Opioid analytes detected | Fentanyl, methadone | Codeine, fentanyl, fentanyl analogues, methadone, morphine, oxycodone, tramadol | |

| Emergency Department Disposition | Admit ICU 3.4% (N = 1) | Admit ICU 11.1% (N = 6) | Admit ICU 8.4% (N = 7) |

| Admit non-ICU 3.4% (N = 1) | Admit non-ICU 27.8% (N = 15) | Admit non-ICU 19.3% (N = 16) | |

| Admit psychiatry 0% | Admit psychiatry 9.3% (N = 5) | Admit psychiatry 6.0% (N = 5) | |

| Discharge 93.1% (N = 27) | Discharge 51.9% (N = 28) | Discharge 66.2% (N = 55) | |

| ARF | 27.6% (N = 8) | 33.3% (N = 18) | 31.3% (N = 26) |

| ACVE | 0% | 9.5% (N = 2) | 2.4% (N = 2) |

| Death | 0% | 0% | 0% |

ICU is Intensive Care Unit; ARF is Acute Respiratory Failure; ACVE is Adverse Cardiovascular Event.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported in part by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DA037317 (PI: Manini). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no commercial conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Alves VL, Gonçalves JL, Aguiar J, et al. The synthetic cannabinoids phenomenon: from structure to toxicological properties. A review. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2020;50(5):359–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hermanns-Clausen M, Müller D, Kithinji J, et al. Acute side effects after consumption of the new synthetic cannabinoids AB-CHMINACA and MDMB-CHMICA. Clin Toxicol (Phila)). 2018;56(6):404–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Drenzek C, Geller RJ, Steck A, et al. Severe illness associated with synthetic cannabinoid Use-Brunswick, Georgia, 2013. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2013;62(46):939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Jinwala FN, Gupta M. Synthetic cannabis and respiratory depression. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):459–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Richards JR, Schandera V, Elder JW. Treatment of acute cannabinoid overdose with naloxone infusion. Toxicology Communications. 2017;1(1):29–33. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Jones JD, Nolan ML, Daver R, et al. Can naloxone be used to treat synthetic cannabinoid overdose? Biol Psychiatry. 2017;81(7):e51–e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Alon MH, Saint-Fleur MO. Synthetic cannabinoid induced acute respiratory depression: Case series and literature review. Respir Med Case Rep. 2017;22:137–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Schmid K, Niederhoffer N, Szabo B. Analysis of the respiratory effects of cannabinoids in rats. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2003;368(4):301–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Justinova Z, Tanda G, Munzar P, et al. The opioid antagonist naltrexone reduces the reinforcing effects of Delta 9 tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in squirrel monkeys. Psychopharmacology (Berl)). 2004;173(1-2):186–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Haney M, Ramesh D, Glass A, et al. Naltrexone maintenance decreases cannabis self-administration and subjective effects in daily cannabis smokers. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(11):2489–2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]