Abstract

The recent discovery that the prevalence of cysteine mutations in the NOTCH3 gene responsible for CADASIL was more than 100 times higher in the general population than that estimated in patients highlighted that the mutation location in EGFr-like-domains of the NOTCH3 receptor could have a major effect on the phenotype of the disease. The exact impact of such mutations locations on the multiple facets of the disease has not been fully evaluated. We aimed to describe the phenotypic spectrum of a large population of CADASIL patients and to investigate how this mutation location influenced various clinical and imaging features of the disease. Both a supervised and a non-supervised approach were used for analysis. The results confirmed that the mutation location is strongly related to clinical severity and showed that this effect is mainly driven by a different development of the most damaging ischemic tissue lesions at cerebral level. These effects were detected in addition to those of aging, male sex, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. The exact mechanisms relating the location of mutations along the NOTCH3 receptor, the amount or properties of the resulting NOTCH3 products accumulating in the vessel wall, and their final consequences at cerebral level remain to be determined.

Keywords: CADASIL, phenotype, variability, mutation, NOTCH3

Introduction

Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL) is the most frequent inherited cause of stroke and vascular dementia. 1 The disease is caused by stereotyped mutations of the NOTCH3 gene that encodes a transmembrane receptor of vascular smooth muscle cells and pericytes. 2 These mutations lead to an odd number of cysteine residues within one of the Epidermal Growth Factor-like repeats (EGFr) of the receptor 3 which results in a progressive accumulation of NOTCH3 extracellular domains aggregating with multiple matrix proteins in the wall of arterioles and capillaries.4,5 More than 200 pathogenic NOTCH3 mutations have been identified so far. 6

The hallmark symptoms of CADASIL include attacks of migraine with aura, ischemic stroke events, cognitive decline from subtle dysexecutive symptoms up to severe dementia, seizures and various neuropsychiatric symptoms such as mood or behavior alterations.7–9 In addition to the strong aging effect on disease progression, another major characteristic of the disease is the high variability of clinical presentation and severity among diagnosed patients. This was noticed from the first description of the disease 10,11 and confirmed later repeatedly both between and inside families, up to the sibling level.9,12 The first analyses of large samples of symptomatic CADASIL patients did not reveal any clear impact of the mutational spectrum on this phenotypic variability. 13 Conversely, male sex and cardiovascular risk factors, such as smoking or hypertension were found significantly related to clinical severity.14–16 Recent data suggest that the clinical phenotype may also differ according to the population origin.17,18 At MRI level, the APO E ε4 allele was previously associated with the volume of white matter lesions on MRI. 19

The minimal prevalence of the disease was initially estimated around 2–5 per 100,000 in Europe20,21 with most mutations detected in symptomatic subjects clustering within a hotspot encompassing the EGFr domains from 1 to 6 of the NOTCH3 receptor. 3 Recently, the discovery of an unexpectedly large number of cysteine mutations outside the EGFr 1–6 hotspot in the general population raised the hypothesis that the exact position of the mutation along the gene influences the clinical expression of the disease.22–24 A later stroke onset was reported in patients having NOTCH3 mutations located in EGFr domains from 7 to 34 in comparison with patients having a mutation inside the EGFr 1-6 domains. 25 Recent data even showed that the disease can remain totally silent at a very advanced age in some individuals. 26 In previous large cohorts of patients with a confirmed diagnosis of the disease, the exact phenotypic impact of mutation location in different EGFr domains has not been evaluated precisely on the multiple aspects of the disease.

In the present study, we aimed to describe the phenotypic spectrum of a large clinical population of patients diagnosed with CADASIL, to clarify to what extent the clinical manifestations observed in this sample are representative of those observed in other large cohorts of patients in the literature and to investigate how the location of mutation in different EGFr domains may influence different features of this phenotype in addition to age, gender and vascular risk factors.

Patients and methods

Patients

All patients were recruited between 2003 up to the end of 2020 at the French National Referral Center for rare cerebrovascular diseases in France (www.cervco.fr). The diagnosis of CADASIL was confirmed in all individuals by genetic testing showing a typical NOTCH3 mutation altering the number of cysteine residues. 2 The diagnosis was always obtained after an informed and written consent. Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes and analyzed using two different sequencing techniques according to the date of entry in the cohort. Before 2016, Sanger sequencing methods were used for searching the most frequent pathogenic mutations of the NOTCH3 gene identified so far. After 2016, the Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technique allowing the sequencing of all exons of the NOTCH3 gene was systematically used. 27 In each subject, the EGF domain where the cysteine mutation was located was systematically recorded for the present study. This study was approved by an independent ethics (updated agreement of the Comité d'Evaluation Ethique de l'Inserm or CEEI-IRB-17/388) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in Europa.

Clinical parameters

Clinical data were collected at entry in the cohort study by board-certified neurologists using a standardized questionnaire during individual consultations.

The following information were systematically recorded in each individual: past medical history and hospitalizations, cardiovascular risk factors, history of headache and aura symptoms, all types of ischemic events, seizures, mood disorders, psychiatric disturbances and cognitive complaints. 15 Headache symptoms were classified using the International Classification of Headache Disorders – ICHD3. 28 Migraine with aura (MA) was defined by the occurrence of attacks of migraine with aura or isolated aura. Migraine without aura (MO) was defined by the absence of history of aura. In this study, patients having both attacks of MA and of MO were classified as having MA. Age of migraine onset, migraine frequency during the last two years, headache duration, characteristics of headache and associated symptoms (photo phonophobia, nausea, vomiting) were also recorded. Stroke was defined by a focal neurological deficit of sudden onset associated with an ischemic or hemorrhagic lesion documented on brain imaging. In this study, transient ischemic attacks (TIA) were defined by a focal neurological deficit of sudden onset lasting less than 24 hours and, when available, without any lesion on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The date of stroke onset, detailed symptoms, duration and the type of stroke (ischemic or hemorrhagic) manifestation and location of lesion on imaging data were systematically recorded. The occurrence of episodes of psychiatric manifestations or mood disorders was also evaluated and their date of onset, type of symptoms, use of treatments and/or hospitalization (if any) were systematically recorded.

In each patient, disability was evaluated using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS), 29 Barthel Index, 30 and Instrumental activities of Daily Living (IADL). 31 Cognitive complaints were systematically recorded and all patients were evaluated by an experimented neuropsychologist using a large battery of tests including the Mini-Mental-State Examination (MMSE). 32 Dementia was diagnosed at time of examination based on the DSM-IV criteria. 33

Imaging parameters

MRI data were obtained in each subject at entry in the cohort study and during follow-up using a 1.5 Tesla or 3 Tesla imaging system (General Electric and Siemens). Imaging parameters and sequences used for the study have been repeatedly reported elsewhere.15,34 All lesions were evaluated based on the STRIVE definition criteria. 35 Briefly, white matter hyperintensities (WMH) were assessed on FLAIR images and lacunes on 3D-T1-weighted images. The volume of WMH was measured using the BIANCA method at baseline and expressed as a percentage of the intracranial cavity volume at individual level. 36 The number of lacunes was assessed by an experimented rater as well as the number of microbleeds using validated methods. 37 Lacunes were defined as small cavities with a rounded pattern and a diameter of less than 15 mm, hyperintense on T2-weighted and hypointense on T1-weighted images and distinct from dilated perivascular spaces. Microbleeds were defined as rounded hypointensities of diameter less than 10 mm on susceptibility-weighted images. Finally, the brain volume was calculated based on 3 D-T1-weighted images using validated methods as previously detailed.38,39

Data analysis

Aggregate data from similar cohorts in the literature were also collected. All references containing the term “CADASIL” in titles and abstracts from the PUBMED database and published between 1993 and 2021 were selected. Then, all manuscripts corresponding to original reports written in English were reviewed in details. From 1535 articles, 57 studies corresponded to clinical investigations. Of them, only 14 with at least 50 individuals and reporting at least 3 of the main clinical manifestations of the disease were considered. These cohorts included 51 to 229 patients from Europe (Germany, United Kingdom, Italy), Colombia and Asia (Korea, Japan and China).

Baseline and demographic characteristics of the present cohort were summarized by standard descriptive parameters, e.g., median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables including neurological scores and percentages for categorical variables, unless specified otherwise.

We then assessed the association between the of the NOTCH3 EGFr mutation location (segregating location in domains from 1 to 6 to those in domains from 7 to 34) and various features of the phenotype. Clinical outcomes included a positive history of attacks of migraine with aura, history of stroke, dementia or disability based on the modified Rankin score (<3 or higher), or dependency based on IADL score (6< or higher). Imaging outcomes included the presence of microbleeds, the presence and number of lacunes as well as the degree of atrophy based on BPF measurement.

We first performed supervised analyses, based on each outcome, separately. The nonparametric Wilcoxon test was used continuous outcomes including neurological scores, and the exact Fisher test for categorical outcomes. Multivariable binomial logistic models or linear models were then used to adjust the effect of mutation inside or outside EGF domains from 1 to 6 adjusted on age, sex and cardiovascular risk factors. Multivariable models were fit and factors were selected by the Akaike criterion for defining the final models, forcing the inclusion of EGF domain. We used a multiple imputation method for replacing missing data in the multivariable analyses with predictive mean matching for continuous variables and logistic regression for categorical variables. We did five replicate imputations and used the chained equation method for multiple imputation. 40

We also considered unsupervised analyses, in an attempt to define profiles of severity based on all the outcome measures. Principal component analysis (PCA) was used as a visual tool to assess correlations between the different outcome measures and to display patient profiles. Multiple imputation (MI) was performed to handle missing values on covariates, and the PCA was carried out on the first imputed dataset. Clustering was obtained using the k-means approach. The gap statistic (which compares the total intra-cluster variation for different values of k with their expected values for a distribution with no clustering) was used to determine the optimal number of clusters. Linear relationship between all variables was checked using a matrix scatterplot. No significant outliers were found. Last, given the PCA was mostly performed for data reduction and exploratory purposes, normality of data was not a strict requirement.

All analyses were carried out with the R software, version 4.0.3 (https://www.R-project.org/).

Results

General characteristics of the cohort population

A total of 446 patients from 298 distinct families were included in the cohort study, 197 males and 249 females aged from 24 to 83 years. The mean age at diagnosis was 51 ± 12 years (mean ± SD).

Their main clinical features are summarized in Table 1 with those observed in similar cohorts of the literature. Briefly, 412 patients (93%) experienced typical manifestations of the disease i.e., stroke, TIA, MA, psychiatric symptoms, cognitive impairment, walking difficulties or epilepsy. Hypertension was noticed in 95 (28%) patients, hypercholesterolemia in 168 (49%), active or past smoking in 208 (61%) and diabetes in 23 (6.7%). Nineteen patients of age 61 ± 10 years (4.3%) required assistance in daily living, 16 patients of mean age of 55 ± 9 years (3.7%) patients were institutionalized at time of the study.

Table 1.

Main clinical findings in the largest CADASIL cohorts selected in the literature in addition to the present cohort.

| Authors | Dichgans et al. 1998 9 | Adib Samii et al. 2010 13 | Wang et al. 2011 52 | Zhang et al. 2014 18 | Moreton et al. 2014 56 | Bianchi et al. 2015 57 | Liao et al. 2015 58 | Ueda et al. 2015 59 | Chen et al. 2017 17 | Mukai et al. 2020 60 | Ospina et al. 2020 61 | Shindo et al. 2020 62 | Kim et al. 2020 63 | Min et al. 2022 64 | Our cohort, present |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Germany | GB | China | China | Scotland | Italy | China | Japan | China | Japan | Colombia | Japan | Korea | Korea | France |

| Number of patients | 102 | 200 | 57 | 52 | 105 | 229 | 112 | 51 | 169a | 179 | 90 | 88 | 55 | 142 | 446 |

| Number of families | 29 | 124 | 33 | 14 | 49 | 150 | 95 | – | 179 | – | – | – | – | 298 | |

| Male, n (%) | 42 (41) | 86 (43) | – | 28 (54) | 52 (50) | 117 (51) | 62 (55) | 27 (53) | 97 (45) | 88 (49.2) | 41 (45.6) | 50 (62.5) | 28 (51.9) | 55 (38.7) | 197/249 (44) |

| Mean age at study | 49.7 ± 13 | 47.7 ± 11.4 | 45.6 ± 9.9 | – | – | 57.8 ± 4.7 | 57.2 ± 12 | 50.3 | – | 54.7 ± 10.5 | 36 | – | 52.1 ± 12.5 | 54.7 ± 10 | 53 ± 12 |

| Mean age at diagnosis | – | – | – | – | – | 57.8 ± 14.7 | – | – | 49 ± 9 | – | – | – | – | – | 51 ± 12 |

| Family history of stroke, n (%) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 150 (88.8) | – | 28 (31.8) | – | 87 (61.3) | 235 (53) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | – | 47 (24) | – | – | 13/98 (13) | 82 (36) | 44 (39) | – | – | 40 (23) | 15 (16.6) | 13 (14.8) | 13 (23.6) | 40 (28.2) | 95 (28) |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | – | 127 (68) | – | – | 40/68 (58) | 80 (35) | 20 (18) | – | – | 53 (30.6) | 14 (15.6) | 31 (35.2) | – | 18 (12.7) | 168 (49) |

| Current and ex smoker, n (%) | – | 101 (50) | – | – | 43/90 (47) | 37 (16) | 11 (10) | – | – | 72 40.9 | 30 (33.3) | – | 22 (40.0) | 15 (10.6) | 208 (61) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | – | – | – | – | – | 30 (13) | 16 (14) | – | – | 10 (5.7) | 5 (5.6) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (3.6) | 21 (14.8) | 23 (6.7) |

| Symptomatic, n (%) | 83 (81) | 200 (100) | 57 | 48 (92) | 101 (96) | 229 (100) | – | – | – | – | 36 (40) | – | – | 142 (100) | 412 (93.4) |

| Mean age at symptom onset | 37 ± 13.5 | 33.6 ± 14.1 | 42.7 ± 9 | 42.4 ± 8.9 | – | 48.5 ± 17.1 | 54.1 ± 12.5 | – | 45 ± 9 | 50 ± 10.2 | – | 49.5 | – | 51.2 ± 10 | – |

| Clinical examination, | |||||||||||||||

| – gait ataxia, n (%) | 38 (37) | – | – | – | – | – | 18 (16) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 131 (30) |

| – urinary incontinence, n (%) | 31 (30) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 89 (20) |

| – pseudobulbar palsy, n (%) | 19 (19) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 48 (27.1) | – | 20 (22.7) | – | – | 19 (4) |

| Headache, n (%) | 49 (48) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 18 (32.7) | 57 (40.1) | 299 (67.6) |

| – mean age at onset | 26 ± 8.2 | 29.4 ± 12.7 | – | – | – | – | – | 35.6 ± 12.7 | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| – first manifestation, n (%) | 48 (47) | 134 (67) | 2/33 (6) | 21 (40) | – | 46 (23) | 2 (2) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 131 (29.7)b |

| – Migraine, n (%) | 39 (38) | 150 (75) | – | – | –73 (70) | 95 (42) | 3 (3) | 17 (33) | 50 (32) | 63 (36.4) | – | – | – | 221 (52) | |

| – Migraine with aura, n (%) | 34 (33) | 135 (68) | 3 (5) | – | – | 42 (18) | – | – | 29 (17.2) | – | 39 (43.3) | 12(13.6) | – | 33 (23.2) | 179(40) |

| Stroke or TIA, n (%) | 72 (71) | 102 (52) | 47 (82) | 14 (27) | 64 (61) | 136 (59) | 86 (77) | 35 (69) | 115 (68) | 134 (74.8) | 33 (35.6) | 59 (67) | 34 (61.8) | 87 (61.3) | 235 (53.2) |

| – mean age at onset | 46.1 ± 9 | 46 ± 9.7 | – | – | 52 M/57 F | – | – | 48.5 ± 10.1 | – | 50.3 ± 10 | – | – | – | 54.1 ± 8 | 52 ±10 |

| – first manifestation, n (%) | 47 (46) | 39 (20) | 24/33 (72) | 30 (63) | – | 100 (51) | 64 (57) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 158 (35.8) | |

| Cognitive impairment, n (%) | 49 (48) | – | 34 (60) | – | 50 (48) | – | – | – | – | 94 (54) | – | – | 11 (20.0) | 61 (43) | 191 (43.4) |

| Dementia DSM IV, n (%) | 29 (28) | 34 (16) | – | – | – | 88 (38) | 46 (41) | 16 (31) | 97 (57.4) | – | 14(15.6) | 31 (35.2 ) | – | 42 (9.5) | |

| – mean age at diagnosis | – | 54.6 ± 9.7 | – | – | – | – | – | 57.8 ± 4.7 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 57±11 |

| – first manifestation, n (%) | 6 (6) | 6 (3) | 4/33 (12) | 12 (23) | – | 7 (4) | 19 (17) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 26 (5.9) |

| Psychiatric disturbance, n (%) | 31 (30) | 75 (38) | 4 (7) | 11 (21) | 49 (47) | 111 (48) | 17 (15) | 10 (20) | 56/169 (33) | 37 (21.4) | 30 (33.3) | – | 15 (27.3) | 29 (20.4) | 167 (37.8) |

| – mean age at onset | – | 41 ± 10.2 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 49 ± 13 | |||

| – first manifestation, n (%) | 1 (1) | 17 (9) | 2/33 (6) | – | – | 19 (10) | 4 (4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 29 (6.6) |

| – Depression, n (%) | 4 (4) | 70 (35) | – | – | – | 77 (34) | 11 (10) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 162 (36.3) |

| – Manic episodes, n (%) | 1 (1) | 1 (<1) | – | – | – | – | 1 (<1) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4 (< 1) |

| – Delirium, n (%) | 3 (3) | 2 (<1) | – | – | – | 8 (4) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 (<1) |

| – Schizophrenia, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (<1) | – | – | – | – | 2 (2) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Epileptic seizure, n (%) | 10 (10) | – | – | 1 (2) | 8 (8) | 19 (8) | – | – | – | 12 (6.9) | 0 (0) | 38 (8.6) | |||

| first manifestation, n (%) | – | 2 (1) | – | – | – | 11 (6) | – | – | – | – | – | – | 10 (2.4) |

–: data not available.

aGenetic results obtained in 219 patients but clinical data available in 169 patients.

bMigraine with aura.

Spectrum of clinical and imaging manifestations

Migraine attacks

Two hundred and ninety-nine patients (67.6%) had a history of headache: 179 (40% of the whole cohort) reported attacks of MA or isolated aura, and 42 (9.5% of the whole cohort) had only attacks of MO. Among patients reporting MA, 121 patients (71.6%) had a progressive installation of aura symptoms (‘marche migraineuse’). The most frequent aura symptoms were visual (86.5%) and 114 patients (64.8%) already had more than one symptom of aura. Twenty patients (12%) already experienced aura symptoms lasting more than one hour, and 28 (16.7%) patients had motor symptoms during previous auras. Confusion, drop in vigilance or coma were reported in 15 patients (8.4%) having MA, which was preceded by classical visual and sensitive aura symptoms in 13 of them, and by aphasic aura in 11 of them.

Ischemic events

At entry in the cohort, 235 patients (53.2% of the whole cohort) had a history of stroke, with a mean age at first event of 52 ± 10 years, and a mean number of two previous stroke events per individual. Among this subset of patients, only 174 (74%) had a typical history of lacunar ischemic stroke. Six patients (2.6%) had a history of brain hemorrhage that involved the brainstem in all cases. One hundred and twenty-seven patients having a history of stroke (54%) presented with some residual deficit from previous episodes.

Mood disturbances and psychiatric manifestations

One hundred and sixty-seven patients (37.8% of the whole cohort) already had mood alterations or psychiatric disturbances. The mean age at onset of these manifestations was 49 ± 13 years. In this group, 162 already experienced significant depressive symptoms, 4 already had manic episodes and one had delusional episodes. One hundred and forty-seven patients required medication and 38 required a hospitalization.

Seizures

Thirty-eight patients (8.6% of the whole cohort) reported epileptic seizures; 10 of them (27% of epileptic patients) had partial seizures, 24 patients (65% of epileptic patients) had generalized seizures, 2 patients (5% of epileptic patients) had both and data were not available in one patient.

Cognitive decline

One hundred and ninety one patients of mean age of 57 ± 11 years (43.4% of the whole cohort) had some cognitive complaints at inclusion in the study. Forty-two patients (9.5% of the whole cohort) had dementia according to DSM IV criteria. Beyond 65 years of age, 42.4% of the CADASIL patients had a MMSE score equal or below 24.

Gait and walking difficulties

One hundred and twenty-one individuals (27.4% of the whole cohort) reported some gait or walking difficulties at entry in the study, 89 patients (20.1%) urinary problems, 36 patients (8.1%) swallowing alterations, and 19 patients (4.3%) spasmodic laughing and crying.

Disability and dependency

Considering the whole CADASIL cohort, 267 (60%) patients beyond age of 50 years remained independent for daily life activities and had a Rankin score less than 2. The mean Barthel score at inclusion was 93 ± 19 indicating only a mild dependence (91–100) globally. However, after age of 55 years, a majority of patients presented with some gait difficulties. Moreover, among the 235 patients having had a previous stroke, 86 patients (36.8%) had at least one residual symptom such as walking, urinary or swallowing difficulties and/or pseudobulbar palsy. Patients with a moderate to severe disability at inclusion who required assistance for daily living and walking (Rankin scores 4–5) corresponded to 7% of patients in the age range of 45-65 years, and to 20% of patients over 65 years old (Supplementary data: Figure A).

Main imaging findings

From the whole cohort, 434 CADASIL patients had MRI data at entry in the study. All of them presented with white matter hyperintensities on FLAIR or T2-weighted images, 75% had at least one lacune and 52% presented at least with one microbleed on T2* images or SWI images.

Effects of NOTCH3 mutation location in egf domains on various phenotypic features in addition to the effects of age and vascular risk factors

The exact position of mutation was available from the genetic test in 436 individuals. The spectrum of all mutation locations according to EGF domains of the NOTCH3 gene is summarized in Figure B (Supplementary data). In 283 patients (65%), the pathogenic mutation was located in EGFr domains from 1 to 6, in 153 patients (35%) the mutation was within EGFr domains from 7 to 34. The mutations located in NOTCH3 EGFr domains from 2 to 4 corresponded to the majority of individuals of the cohort (233 patients, 53%). EGFr like domain 25 was the second mutational hotspot (38 patients (8.7%)).

Patients harboring a mutation in NOTCH3 EGFr domains from 7 to 34 were older than individuals with a mutation in EGFr domains from 1 to 6 (mean age: 57 ± 11 and 50 ± 12 respectively (p < 0.0001)). In addition, they were more frequently hypertensive (respectively 32% versus 16%, p < 0.0001) and active or past smokers (60% versus 49.5%, p = 0.038). Other main differences between the two groups are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Main clinical and imaging features in the population according to the location of mutation (univariate analysis, a: yes versus no).

| Location mutation in EGFr like domains | 1–6 | 7–34 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| General characteristicsa | |||

| Age, mean in years (SD) | 50 (12) | 57 (11) | <0.0001 |

| Sex male, n (%) | 132 (46.6) | 60 (39.2) | 0.14 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 6 (16.3) | 9 (32.2) | 0.0001 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 143 (50.5) | 61 (40.1) | 0.038 |

| Hypercholesterolemia, n (%) | 103 (36.4) | 64 (42.1) | 0.24 |

| Clinical outcomes | |||

| Migraine with aura or isolated aurasa, n (%) | 130 (45.9) | 47 (30.9) | 0.002 |

| History of strokea, n (%) | 160 (56.5) | 73 (48.0) | 0.090 |

| mRS score ≥3a, n (%) | 48 (17.1) | 23 (15.2) | 0.62 |

| MMSE Score ≤24, n (%) | 57 (21.5) | 24 (17.4) | 0.33 |

| Dementiaa, n (%) | 35 (12.4) | 7 (4.6) | 0.009 |

| Gait disturbances, n (%) | 73 (25.8) | 48 (31.6) | 0.20 |

| Balance disturbances, n (%) | 83 (29.3) | 48 (31.6) | 0.63 |

| Swallowing difficulties, n (%) | 24 (8.5) | 12 (7.9) | 0.83 |

| Barthel Index <100, n (%) | 57 (20.5) | 25 (16.6) | 0.32 |

| IADL <6: n (%)a | 47 (17.5) | 13 (9.1) | 0.021 |

| Imaging outcomesa | |||

| WMH – median % of ICC (Q1–Q3) | 4 (2–7) | 4 (2;6) | 0.88 |

| ≥1 lacune, n (%) | 219 (79.1) | 118 (78.7) | 0.92 |

| Number of lacunes ≥5, n (%) | 155 (56.0) | 77 (51.3) | 0.36 |

| ≥1 microbleed, n (%) | 86 (31.2) | 69 (45.7) | 0.003 |

| BPF – mean % of ICC (SD) | 81 (5) | 80 (4) | 0.016 |

The effects of the location of NOTCH3 mutation in EGFr domains 1–6 versus 7–34 in addition to that of age, sex, hypertension, smoking and diabetes on the phenotype analyzed using multivariable analyses are presented in Table 3. In univariable analyses, mutation in EGFr domains 1–6 was associated with an increased prevalence of migraine with aura, and dementia. After adjustment on potential predictors, mutation in EGFr domains 1–6 was no longer associated with migraine with aura, whose prevalence was found lower in men or in older individuals. In contrast, mutation location in EGFr 1–6 was found associated with a higher risk of stroke in addition to the deleterious effect of age, male sex, hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. While only age and male sex were found associated with disability measured using the modified Rankin scale dichotomized as no or mild versus moderate or severe, the association of the mutation location with dementia persisted in addition to the effect of age and male sex. Moreover, mutation in EGFr domain 1–6 was found associated with dependency assessed by IADL that was also related to age and hypercholesterolemia.

Table 3.

Effect of the NOTCH3 mutation location in EGFr domains on different clinical outcomes (multivariable analysis).

| Outcomes | Number events | Univariable analyses | Multivariable analyses |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%CI) | OR (95%CI) | ||

| Migraine with aura | 177 | ||

| Mutation in EGFr 1–6 vs 7–34 | 1.90 (1.25 to 2.88) | 1.54 (0.98 to 2.40) | |

| Age | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.98) | ||

| Sex male (y/n) | 0.64 (0.43 to 0.97) | ||

| Hypertension (y/n) | 0.65 (0.38 to 1.11) | ||

| Diabetes (y/n) | 0.42 (0.14 to 1.33) | ||

| Stroke | 233 | ||

| Mutation in EGFr1–6 vs 7–34 | 1.41 (0.95 to 2.09) | 2.11 (1.33 to 3.33) | |

| Age | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.06) | ||

| Sex male (y/n) | 2.43 (1.60 to 3.68) | ||

| Hypertension (y/n) | 2.56 (1.48 to 4.42) | ||

| Hypercholesterolemia (y/n) | 1.63 (1.05 to 2.54) | ||

| mRS score 3–5 (vs 0–2) | 71 | ||

| Mutation in EGFr 1–6 vs 7–34 | 1.15 (0.67 to 1.97) | 1.78 (0.98 to 3.23) | |

| Age (y/n) | 1.09 (1.06 to 1.12) | ||

| Sex male (y/n) | 2.01 (1.16 to 3.49) | ||

| Dementia | 42 | ||

| Mutation in EGFr 1–6 vs 7–34 | 2.9 (1.26 to 6.70) | 4.56 (1.85 to 11.26) | |

| Age | 1.10 (1.06 to 1.14) | ||

| Sex male (y/n) | 2.57 (1.24 to 5.32) | ||

| Diabetes (y/n) | 0.24 (0.03 to 2.02) | ||

| Smoking (y/n) | 0.60 (0.29 to 1.26) | ||

| IADL < 6 | 61 | ||

| Mutation in EGFr 1–6 vs 7–34 | 1.85 (0.98 to 3.47) | 3.55 (1.74 to 7.22) | |

| Age (y/n) | 1.10 (1.07 to 1.14) | ||

| Hypercholeterolemia (y/n) | 2.11 (1.15 to 3.88) |

The results of the identical analysis of imaging markers are presented in Table 4. In univariate analysis, the location of NOTCH3 mutation in EGFr like domains was not found associated with any of the MRI markers. After adjustment, no further association was detected with WMH related to age and hypertension. While the presence of lacunes on MRI was only related to age and male sex, the mutation location was independently associated with a number of lacunes higher than 5 in addition to the effect of age, male sex and hypertension. The presence of microbleeds was related to age, male sex and hypertension. The degree of atrophy was found larger in men and with increasing age.

Table 4.

Effect of the NOTCH3 mutation location in EGFr domains on different MRI parameters (multivariable analysis).

| Outcomes | N subjects or Mean value (SD) | Univariable analysesa Regression coefficient or OR (95%CI) |

Multivariable analysesaRegression coefficient or OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| WMH (% of ICC) | 5.2 (4.2) | ||

| Mutation in EGFr 1–6 vs 7–34 | –0.29 (–1.13 to 0.55) | –0.35 (–1.11 to 0.42) | |

| Age | –0.21 (–0.24 to –0.18) | ||

| Hypertension (y/n) | –0.93 (−1.81 to –0.04) | ||

| Lacunes (y/n) | N = 337 | ||

| Mutation in EGFr 1–6 vs 7–34 | 1.02 (0.63 to 1.67) | 1.58 (0.89 to 2.82) | |

| Age | 1.09 (1.06 to 1.12) | ||

| Sex male (y/n) | 5.82 (3.10 to 10.93) | ||

| N Lacunes 5 | N = 209 | ||

| Mutation in EGFr 1–6 vs 7–34 | 1.06 (0.71 to 1.58) | 1.78 (1.10 to 2.89) | |

| Age | 1.08 (1.06 to 1.10) | ||

| Sex male (y/n) | 4.10 (2.60 to 6.46) | ||

| Hypertension (y/n) | 2.39 (1.37 to 4.17) | ||

| Microbleeds (y/n) | N = 155 | ||

| Mutation in EGFr 1–6 vs 7–34 | 0.54 (0.36 to 0.81) | 0.83 (0.52 to 1.31) | |

| Age (y/n) | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.09) | ||

| Sex male (y/n) | 1.43 (0.92 to 2.22) | ||

| Hypertension (y/n) | 2.23 (1.34 to 3.73) | ||

| BPF (% of ICC) | 80.4 (4.5) | ||

| Mutation in EGFr 1–6 vs 7–34 | 1.08 (0.19 to 1.97) | –0.27 (–1.03 to 0.49) | |

| Age | –0.21 (–0.24 to –0.18) | ||

| Sex male (y/n) | –1.67 (–2.37 to –0.97) | ||

| Hypertension (y/n) | –0.85 (–1.72 to 0.02) |

aRegression coefficient of a linear model in case of a continuous outcome (WMH and BPF), Odds ratio (OR) for binary outcomes (lacunes, Number of lacunes at 5 or above, and microbleeds.

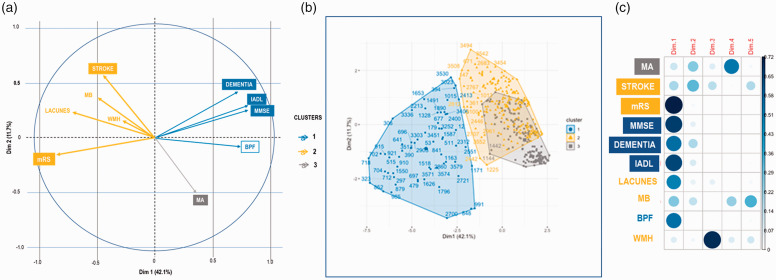

Figure 1 summarizes the main findings obtained with the principal component analysis. It displays the correlations between the different outcome measures, exhibiting three main clusters namely a first cluster (1) where dementia is highly correlated with IADL, MMSE scores to a lesser extent with the BPF value, a second cluster (2) where a past history of stroke was correlated with the modified Rankin Scale (mild versus moderate/severe disability) and to a less extent with the presence of lacunes and microbleeds and a third cluster (3) where the occurrence of migraine with aura is isolated. This allowed defining 3 subsets of patients, of prevalence 60, 214 and 189, respectively. Interestingly, the location of the NOTCH3 mutation in EGF domain 7–34 was observed in 21.4%, 41.1%; and 32.8% respectively (p = 0.016) (Supplementary Table A).

Figure 1.

Principal Component Analysis showing 3 main clusters capturing the largest amount of variance of data from the cohort. A graphic representation of the analysis shows the variability of the main clinical or imaging manifestations of the disease: (a) is a variable correlation plot showing the variables grouped together when they are positively correlated and positioned on opposite sides when they are negatively related, (b) is a 3D-plot showing the 3 clusters obtained with all data and (c) shows the contribution of the different variables to the PCA in the different dimensions.

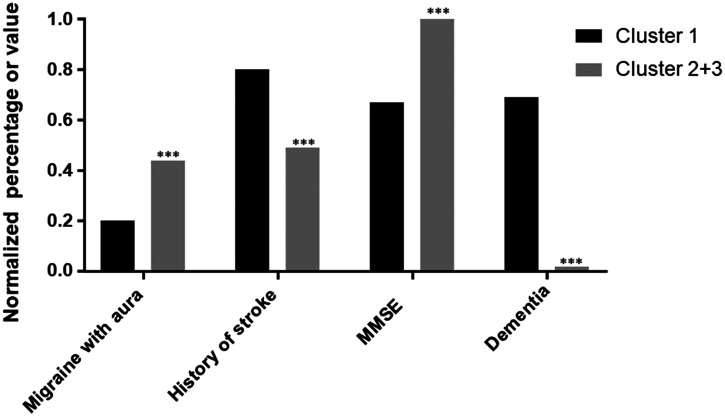

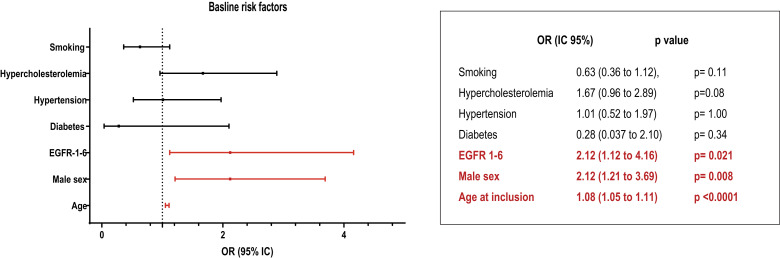

Given the first cluster was distinguished from the others on multiple aspects, we further looked at this subset. Supplementary Table B summarizes the characteristics of those patients. Interestingly, patients from cluster 1 were more likely to be old, men and with EGF domain 1–6 (p = 0.021) than in other clusters, but without any increase in cardiovascular risk factors. Based on a multivariable logistic regression model, such a patient profile was characterized mostly by low cognitive performances at MMSE, a high prevalence of dementia, dependency as measured by IADL and cerebral atrophy measured by BPF (Figure 2). Multivariable analysis limited to the baseline risk factors showed that 3 factors only differed significantly between this cluster and the two others, the location mutation in EGFr domains 1 to 6, male sex and hypertension (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Differences between Cluster 1 compared to Cluster 2 + 3 of main clinical manifestations (p < 0.0001*** after multivariable logistic regression analysis).

Figure 3.

Multivariable analysis limited to the baseline risk factors showing the differences between Cluster 1 and Cluster 2 + 3. Odds ratios were calculated and their exact values and significance are presented.

Spectrum of clinical manifestations in cohorts of more than 50 individuals selected from the literature

Among these cohorts, the male to female ratio was largely variable from 38.7 to 62.5%. Mean age of patients varied from 36 to 57 years. Vascular risk factors were not always detailed but were frequently detected in most studies, 13 to 39% of patients were hypertensive, 12 to 68% had hypercholesterolemia, and 1 to 15% had diabetes, 10 to 50% were smokers. In the vast majority of patients, symptoms were reported in more than 80% of individuals except in a Colombian cohort comprising only 40% of symptomatic patients. Mean age at symptom onset varied from 33 up to 54 years among the different populations. Migraine with aura was reported by 5 to 68% of individuals included in the different cohorts, stroke or TIA from 27 to 82%, mood disturbances by 7 to 48% and cognitive changes by 20 up to 60% of cohort individuals. Depressive episodes were reported with a frequency varying from 4 up to 36% in the different samples.

Discussion

In this large population of 446 consecutive CADASIL cases referred to an expert clinical center, 35% of patients were diagnosed with a typical cysteine mutation outside the EGFr domains like 1 to 6 of the NOTCH3 gene. The main findings of this study is that the mutation location inside or outside this mutational hotspot has a strong impact on the clinical severity of CADASIL patients. A raw analysis of these groups showed first that although patients with mutations in EGFr domains from 7 to 34 were older and twice more frequently hypertensive than the rest of the sample, they were less frequently demented or dependent. Further analysis considering other potential predictors of clinical worsening showed that when a cysteine mutation is detected in EGFr domains from 1 to 6, the prevalence of stroke more than doubles independently of age, male sex and the presence of vascular risk factors. Moreover, an independent association was also found with such a mutation location and dementia or dependency assessed using the level of activities in daily living. Analysis of imaging data suggest that these differences might be mainly driven by a different amount of small infarctions at cerebral level.41,42 The prevalence of cases with a large number of lacunes was higher in patients with mutations located in EGFr 1 to 6 than outside, regardless of any other potential aggravating factor. These results are in line with the earlier stroke onset associated with identical mutation locations already reported in a distinct cohort study. 24

In the present study, we further confirmed these results using a non-supervised statistical approach. PCA analysis showed first that our data were very consistent with our knowledge of the disease. Three clusters were identified. One associated stroke with lacunes that can develop after such clinical events and with the modified Rankin score which mainly reflects motor disability increasing with accumulation of these lesions along disease progression. 43 A much smaller association was found in the same cluster with the amount of white matter hyperintensities. In line, we previously showed that clinical disability and lacunes are actually related only to the development of periventricular white-matter hyperintensities but not to that of juxtacortical white-matter lesions.41,44,45 Another cluster includes only the occurrence of migraine with aura whose prevalence is not linked to the other clinical features. These findings are also in accordance with the total absence of association between migraine with aura and stroke events, disability or cognitive decline in multiple previous studies. 46 Finally, another cluster includes the most severe cases, three out of four of whom already had a stroke or were demented and all had moderate or severe motor disability. The cluster also had the lowest brain volume. After considering all potential confounders, multivariable analysis confirmed the highest clinical severity of this group. The location of mutation inside EGFR domains 1 to 6 was also found independently related to these clinical features. Finally, altogether, our data emphasize that patients with mutation outside these domains would be actually spared such a clinically deleterious course. Further investigations are needed to clarify whether this is simply a matter of a later onset of motor or cognitive deficits due to less severe ischemic insults accumulating at cerebral level contrasting with white-matter lesions of a different origin. Accumulating evidence suggests that NOTCH3 accumulation in the vessel wall might be lower in presence of a mutation in EGFr domains 7 to 34. If these findings obtained using skin biopsies in peripheral vessels are also true at the level of the cerebral microvasculature, our data would support that the development of white-matter lesions and of lacunes would not depend, in the same way, on the amount of extracellular NOTCH3 protein aggregating in the vascular wall. An alternative hypothesis is that the location of mutations in EGFr domains 7–34 is responsible for a slower progression of the underlying cSVD itself along aging, or even for a time lag of several decades in the onset of the disease in some individuals as suggested by recent observations. 47

Our results not only confirm that the mutation location has a strong impact on clinical severity but also that some vascular risk factors can actually modulate the clinical progression in CADASIL. In this study, we observed that the male sex in addition to the age effect was definitely associated with an increased prevalence of stroke events, moderate or severe disability, dementia and functional dependency. This is in line with data already obtained in a limited sample of this cohort 14 as well as, more generally in sporadic small vessel diseases. 48 We also found that any previous history of hypertension was independently associated with the occurrence of stroke manifestations, dementia and dependency as already reported.42,49 We confirmed in parallel that hypertensive patients had more lacunes and microbleeds as already detected.15,42 In the present study, hypercholesterolemia but not smoking was independently associated with the occurrence of stroke and functional dependency in multivariable analysis. Opposite results had been reported in previous cross-sectional 16 and longitudinal analysis data 50 based on other definitions of vascular risk factors and which did not take into account the mutation location as a potential confounding factor. In a single but old study, the severity of atherosclerosis was found possibly related to clinical severity. 51 Thus, aditionnal investigations are needed to confirm whether the cholesterol level may participate to the aggravation of the vascular disease.

This association between the mutation location in addition to the effects of age, male sex, hypercholesterolemia and hypertension was detected in a Caucasian population recruited just after their diagnosis. This sample has many features comparable to those of other European cohorts of the literature. Both the mean age at diagnosis, the proportion of patients having had an ischemic stroke, the frequency of cognitive impairment and that of mood disturbances or depression were relatively close to those reported in other Caucasian cohorts. Only the prevalence of dementia was found lower in our sample, which might be related to different diagnostic criteria. Only in one Italian cohort, an unusual large proportion of psychiatric cases was found remarkable. Conversely, the clinical presentation in our population differs from that observed in Asian cohorts. Particularly, the prevalence of stroke manifestations was lower than the prevalence that can even reach 82% of patients in a cohort from China. 52 Moreover, while the frequency of hemorrhagic stroke was only 2.6% in our patients, a higher prevalence of intracerebral hemorrhages was detected in Asian CADASIL patients that can increase up to 25%. 53 In addition, the proportion of patients with attacks of with aura was much higher in our cohort than in Asian CADASIL patients who were only 5 to 17% to have such typical manifestation of the disease.17,54 The prevalence of WMH in the anterior temporal poles found in most of our patients was also much less frequent in the Asian selected cohorts.52,55 Whether these numerous discrepancies are also related to different mutation positions remains undetermined. A higher proportion of mutations in exon 10 corresponding to EGFr domain 13 of the NOTCH3 gene was previously reported in the Italian cohort with frequent psychiatric symptoms, and a high frequency of mutations located in exon 11 corresponding to EGFr domains 13, 14 and 15 in Asian patients have been previously noticed.17,18,54

The results of this study do not pretend to summarize all possible phenotypic variations related to the multiple positions of the cysteine mutation in the NOTCH3 gene. We are fully aware of multiple potential limitations of such a study, in particular the main one related to major selection biases in a cohort of patients recruited in a single center after their diagnosis and on a voluntary basis. As our recruitment was essentially linked to a medical consultation and most often after the occurrence of neurological manifestations, the number of asymptomatic subjects with silent lesions was largely underrepresented. The centralization of the recruitment in a single referral center reduces the inclusion of the most severely disabled or demented patients who cannot travel long distances. Another limitation is the inclusion of all subjects without actual selection of index patients in our statistical analysis. This selection was not possible since we were not systematically informed about other potential diagnosed cases in the family of each case at entry in the study. Thus, despite the large number of distinct families, we therefore cannot exclude some over-representation of peculiar aspects of the disease due to the lack of complete independence in all our cases. MRI data were also collected with clinical information over almost 20 years. They were first obtained at 1.5 Teslas and later at 3 Teslas and some changes in imaging sequences were unavoidable. Therefore, subtle variations in contrast changes between the brain lesions and the normal tissue were possible throughout the study. On another plan, genetic testing also changed over this long recruitment time. Before 2016, the search for mutations was focused on a limited number of exons of the NOTCH3 gene with only few corresponding to EGFr domains outside the hotspot from 1 to 6. After this date, a high-throughput gene sequencing or NGS techniques allowing the analysis of the entire NOTCH3 gene were possible. The diagnosis might therefore not have been confirmed in a number of patients who were not included in this cohort before 2016. Additional analyses (not shown) revealed however that the phenotypic profiles did not change in our patients according to the mutation location before and after these technical modifications. Another potential limitation is that ApoE genotype was not considered in our analysis although the corresponding allele ε2 might influence the amount of white matter lesions 19 and ε4 the risk of incident dementia. 49 This study has also many strengths. It is one of the world's largest cohorts of patients diagnosed according to standard clinical practice recommendations. 1 The data were collected by an experienced team using standardized clinical parameters and scales from the study onset in 2003. The analysis of the clinical spectrum of patients was accurate and based on multiple detailed information. Brain imaging data were obtained using quantified and validated methods. A detailed analysis of comparative cohorts in the literature shows that the clinical profile of our patients is close to that observed in most samples of similar origin. Finally, different potential predictors of clinical manifestations of the disease have been taken into account at all levels of the analysis.

In summary, our results confirmed that the location of NOTCH3 mutation in different EGFr domains has an indisputable influence on the CADASIL phenotype. They showed that patients with a mutation outside the EGFr domains 1 to 6 have an overall less severe clinical profile and that, conversely, in addition to the mutation location effect, male sex, arterial hypertension and smoking increase the disease severity. Our results also support that this discrepancy might be mainly related to a different development of the most damaging ischemic cerebral tissue lesions according to the mutation location without a clear influence on the extent of white matter hyperintensities. The precise determinants of these genotype-related differences remain to be discovered. A plausible hypothesis is that the accumulation rate of NOTCH3 protein and/or its interaction with other matrix proteins in the vascular wall differs according to the length and/or composition of the extracellular domain accumulating in the vessel wall. Our results also confirm that other risk factors may independently modulate these vascular wall changes and subsequently the clinical progression of the disease.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X221126280 for Phenotypic variability in 446 CADASIL patients: Impact of NOTCH3 gene mutation location in addition to the effects of age, sex and vascular risk factors by Charlotte Dupé, Stéphanie Guey, Lucie Biard, Sokhna Dieng, Jessica Lebenberg, Lina Grosset, Nassira Alili, Dominique Hervé, Elisabeth Tournier-Lasserve, Eric Jouvent, Sylvie Chevret, Hugues Chabriat in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism

Acknowledgements

We warmly thank the team in charge of formatting and cleaning the database Mrs Claire Pacheco (INSERM UMR1153). We thank very much Mr Abbas Taleb for collecting most of information along the cohort study, the team in charge of the neuropsychological assessments particularly Mrs Sonia Reyes, Aude Jabouley, Carla Machado, Helène De Sanctis, Mrs Solange Hello who managed and organized the appointment of multiple family members involved in the study, Mrs Nathalie Gastelier and Fanny Fernandes, the research managers in charge of the Cohort Study. We thank the CADASIL France Association for their help and permanent support.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was funded by the RHU TRT_cSVD project (ANR-16-RHUS-004) and the ARNEVA (Association de Recherche en Neurologie VAsculaire), Hôpital Lariboisiere, France.

Authors’ contributions: Hugues Chabriat, Stephanie Guey and Charlotte Dupé drafted the manuscript and were responsible for the study. Sylvie Chevret, Lucie Biard and Sokhna Dieng were in charge of the statistical analysis. Eric Jouvent and Jessica Lebenberg were in charge of imaging data quantification. Nassira Alili and Dominique Hervé collected and analyzed the clinical data of the cohort. Lina Grosset participated to the assessment of lacunes of patients and to the analysis of imaging data. Elisabeth Tournier-Lasserve was responsible for the genetic study and quality control of genetic results. Hugues Chabriat also obtained the grant for this study.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Jessica Lebenberg https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5403-8288

Hugues Chabriat https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8436-6074

References

- 1.Guey S, Lesnik Oberstein SAJ, Tournier-Lasserve E, et al. Hereditary cerebral small vessel diseases and stroke: a guide for diagnosis and management. Stroke: J Cerebr Circul 2021; 52: 3025–3032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joutel A, Corpechot C, Ducros A, et al. Notch3 mutations in CADASIL, a hereditary adult-onset condition causing stroke and dementia. Nature 1996; 383: 707–10710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Joutel A, Vahedi K, Corpechot C, et al. Strong clustering and stereotyped nature of Notch3 mutations in CADASIL patients. The Lancet 1997; 350: 1511–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kast J, Hanecker P, Beaufort N, et al. Sequestration of latent TGF-beta binding protein 1 into CADASIL-related Notch3-ECD deposits. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2014; 2: 96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monet-Lepretre M, Haddad I, Baron-Menguy C, et al. Abnormal recruitment of extracellular matrix proteins by excess Notch3 ECD: a new pathomechanism in CADASIL. Brain 2013; 136: 1830–1845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutten JW, Haan J, Terwindt GM, et al. Interpretation of NOTCH3 mutations in the diagnosis of CADASIL. Expert Rev Mol Diagn 2014; 14: 593–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chabriat H, Lesnik Oberstein S. Cognition, mood and behavior in CADASIL. Cerebral Circul – Cogn Behavior 2022; 3: 100043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chabriat H, Joutel A, Dichgans M, et al. Cadasil. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 643–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dichgans M, Mayer M, Uttner I, et al. The phenotypic spectrum of CADASIL: clinical findings in 102 cases. Ann Neurol 1998; 44: 731–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tournier-Lasserve E, Iba-Zizen MT, Romero N, et al. Autosomal dominant syndrome with strokelike episodes and leukoencephalopathy. Stroke: J Cerebr Circul 1991; 22: 1297–1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chabriat H, Tournier-Lasserve E, Vahedi K, et al. Autosomal dominant migraine with MRI white-matter abnormalities mapping to the CADASIL locus. Neurology 1995; 45: 1086–1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chabriat H, Vahedi K, Iba-Zizen MT, et al. Clinical spectrum of CADASIL: a study of 7 families. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Lancet 1995; 346: 934–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adib-Samii P, Brice G, Martin RJ, et al. Clinical spectrum of CADASIL and the effect of cardiovascular risk factors on phenotype. Stroke: J Cerebr Circul 2010; 41: 630–634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gunda B, Herve D, Godin O, et al. Effects of gender on the phenotype of CADASIL. Stroke: J Cerebr Circul 2012; 43: 137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Viswanathan A, Guichard JP, Gschwendtner A, et al. Blood pressure and haemoglobin A1c are associated with microhaemorrhage in CADASIL: a two-centre cohort study. Brain 2006; 129: 2375–2383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singhal S, Bevan S, Barrick T, et al. The influence of genetic and cardiovascular risk factors on the CADASIL phenotype. Brain 2004; 127: 2031–2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen S, Ni W, Yin XZ, et al. Clinical features and mutation spectrum in Chinese patients with CADASIL: a multicenter retrospective study. CNS Neurosci Ther 2017; 23: 707–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tan QC, Zhang JT, Cui RT, et al. Characteristics of CADASIL in Chinese Mainland patients. Neurol India 2014; 62: 257–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gesierich B, Opherk C, Rosand J, et al. APOE varepsilon2 is associated with white matter hyperintensity volume in CADASIL. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 199–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Razvi SS, Davidson R, Bone I, et al. The prevalence of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leucoencephalopathy (CADASIL) in the west of Scotland. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005; 76: 739–741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Narayan SK, Gorman G, Kalaria RN, et al. The minimum prevalence of CADASIL in northeast England. Neurology 2012; 78: 1025–1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gravesteijn G, Hack RJ, Mulder AA, et al. NOTCH3 variant position is associated with NOTCH3 aggregation load in CADASIL vasculature. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2022: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rutten JW, Dauwerse HG, Gravesteijn G, et al. Archetypal NOTCH3 mutations frequent in public exome: implications for CADASIL. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2016; 3: 844–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rutten JW, Van Eijsden BJ, Duering M, et al. The effect of NOTCH3 pathogenic variant position on CADASIL disease severity: NOTCH3 EGFr 1–6 pathogenic variant are associated with a more severe phenotype and lower survival compared with EGFr 7–34 pathogenic variant. Genet Med 2019; 21: 676–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rutten JW, Van Eijsden BJ, Duering M, et al. Correction: the effect of NOTCH3 pathogenic variant position on CADASIL disease severity: NOTCH3 EGFr 1–6 pathogenic variant are associated with a more severe phenotype and lower survival compared with EGFr 7–34 pathogenic variant. Genet Med 2019; 21: 1895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hack RJ, Gravesteijn G, Cerfontaine MN, et al. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy family members with a pathogenic NOTCH3 variant can have a normal brain magnetic resonance imaging and skin biopsy beyond age 50 years. Stroke: J Cerebr Circul 2022; 53: 1964–1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maksemous N, Smith RA, Haupt LM, et al. Targeted next generation sequencing identifies novel NOTCH3 gene mutations in CADASIL diagnostics patients. Hum Genomics 2016; 10: 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache S. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia: Int J Headache 2013; 33: 629–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinn TJ, Dawson J, Walters MR, et al. Reliability of the modified Rankin scale. Stroke: J Cerebr Circul 2007; 38: e144. author reply e145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Granger CV, Dewis LS, Peters NC, et al. Stroke rehabilitation: analysis of repeated barthel index measures. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1979; 60: 14–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clemson L, Bundy A, Unsworth C, et al. Validation of the modified assessment of living skills and resources, an IADL measure for older people. Disabil Rehabil 2009; 31: 359–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cockrell JR, Folstein MF. Mini-mental state examination (MMSE). Psychopharmacol Bull 1988; 24: 689–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Association AP. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fourth edition. American Psychiatric Association: American Psychiatric Press Inc, 1994.

- 34.De Guio F, Reyes S, Duering M, et al. Decreased T1 contrast between gray matter and normal-appearing white matter in CADASIL. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014; 35: 72–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol 2013; 12: 822–838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ling Y, Jouvent E, Cousyn L, et al. Validation and optimization of BIANCA for the segmentation of extensive white matter hyperintensities. Neuroinformatics 2018; 16: 269–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ling Y, De Guio F, Jouvent E, et al. Clinical correlates of longitudinal MRI changes in CADASIL. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2019; 39: 1299–1305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O'Sullivan M, Jouvent E, Saemann PG, et al. Measurement of brain atrophy in subcortical vascular disease: a comparison of different approaches and the impact of ischaemic lesions. NeuroImage 2008; 43: 312–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.De Guio F, Duering M, Fazekas F, et al. Brain atrophy in cerebral small vessel diseases: extent, consequences, technical limitations and perspectives: the HARNESS initiative. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2020; 40: 231–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Buuren S. Multiple imputation of discrete and continuous data by fully conditional specification. Stat Methods Med Res 2007; 16: 219–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Viswanathan A, Gschwendtner A, Guichard J-P, et al. Lacunar lesions but not white matter hyperintensities are independently associated with disability and cognitive impairment in CADASIL: a 2-center cohort study. Stroke: J Cerebr Circul 2007; 38: 608–612. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ling Y, De Guio F, Duering M, et al. Predictors and clinical impact of incident lacunes in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Stroke: J Cerebr Circul 2017; 48: 283–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viswanathan A, Gschwendtner A, Guichard JP, et al. Lacunar lesions are independently associated with disability and cognitive impairment in CADASIL. Neurology 2007; 69: 172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.De Guio F, Vignaud A, Chabriat H, et al. Different types of white matter hyperintensities in CADASIL: insights from 7-Tesla MRI. J Cerebr Blood Flow Metab 2018; 38: 1654–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Duchesnay E, Hadj Selem F, De Guio F, et al. Different types of white matter hyperintensities in CADASIL. Front Neurol 2018; 9: 526–20180710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guey S, Mawet J, Herve D, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of migraine in CADASIL. Cephalalgia 2016; 36: 1038–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gravesteijn G, Hack RJ, Mulder AA, et al. NOTCH3 variant position is associated with NOTCH3 aggregation load in CADASIL vasculature. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2022; 48: e12751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jimenez-Sanchez L, Hamilton OKL, Clancy U, et al. Sex differences in cerebral small vessel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurol 2021; 12: 756887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee JS, Ko KH, Oh JH, et al. Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 is associated with the development of incident dementia in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy patients with p.Arg544Cys mutation. Front Aging Neurosci 2020; 12: 591879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chabriat H, Herve D, Duering M, et al. Predictors of clinical worsening in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy: prospective cohort study. Stroke: J Cerebr Circul 2016; 47: 4–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mawet J, Vahedi K, Aout M, et al. Carotid atherosclerotic markers in CADASIL. Cerebrovasc Dis 2011; 31: 246–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Z, Yuan Y, Zhang W, et al. NOTCH3 mutations and clinical features in 33 Mainland Chinese families with CADASIL. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2011; 82: 534–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Choi JC, Kang SY, Kang JH, et al. Intracerebral hemorrhages in CADASIL. Neurology 2006; 67: 2042–2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim YE, Yoon CW, Seo SW, et al. Spectrum of NOTCH3 mutations in Korean patients with clinically suspicious cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. Neurobiology of Aging 2014; 35: 726 e721–726.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tang SC, Lee MJ, Jeng JS, et al. Arg332Cys mutation of NOTCH3 gene in the first known Taiwanese family with cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy. J Neurol Sci 2005; 228: 125–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moreton FC, Razvi SS, Davidson R, et al. Changing clinical patterns and increasing prevalence in CADASIL. Acta Neurol Scand 2014; 130: 197–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bianchi S, Zicari E, Carluccio A, et al. CADASIL in central Italy: a retrospective clinical and genetic study in 229 patients. J Neurol 2015; 262: 134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liao YC, Hsiao CT, Fuh JL, et al. Characterization of CADASIL among the han Chinese in Taiwan: distinct genotypic and phenotypic profiles. PloS One 2015; 10: e0136501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ueda A, Ueda M, Nagatoshi A, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic spectrum of CADASIL in Japan: the experience at a referral center in Kumamoto university from 1997 to 2014. J Neurol 2015; 262: 1828–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mukai M, Mizuta I, Watanabe-Hosomi A, et al. Genotype–phenotype correlations and effect of mutation location in Japanese CADASIL patients. J Hum Genet 2020; 65: 637–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ospina C, Arboleda-Velasquez JF, Aguirre-Acevedo DC, et al. Genetic and nongenetic factors associated with CADASIL: a retrospective cohort study. J Neurol Sci 2020; 419: 117178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shindo A, Tabei K-i, Taniguchi A, et al. A nationwide survey and multicenter registry-based database of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy in Japan. Front Aging Neurosci 2020; 12: 216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim H, Lim Y-M, Lee E-J, et al. Clinical and imaging features of patients with cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy and cysteine-sparing NOTCH3 mutations. PloS One 2020; 15: e0234797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Min J-Y, Park S-J, Kang E-J, et al. Mutation spectrum and genotype–phenotype correlations in 157 Korean CADASIL patients: a multicenter study. Neurogenetics 2022; 23: 45–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-jcb-10.1177_0271678X221126280 for Phenotypic variability in 446 CADASIL patients: Impact of NOTCH3 gene mutation location in addition to the effects of age, sex and vascular risk factors by Charlotte Dupé, Stéphanie Guey, Lucie Biard, Sokhna Dieng, Jessica Lebenberg, Lina Grosset, Nassira Alili, Dominique Hervé, Elisabeth Tournier-Lasserve, Eric Jouvent, Sylvie Chevret, Hugues Chabriat in Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism