Abstract

Rationale

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is characterized by structural remodeling of pulmonary arteries and arterioles. Underlying biological processes are likely reflected in a perturbation of circulating proteins.

Objectives

To quantify and analyze the plasma proteome of patients with PAH using inherited genetic variation to inform on underlying molecular drivers.

Methods

An aptamer-based assay was used to measure plasma proteins in 357 patients with idiopathic or heritable PAH, 103 healthy volunteers, and 23 relatives of patients with PAH. In discovery and replication subgroups, the plasma proteomes of PAH and healthy individuals were compared, and the relationship to transplantation-free survival in PAH was determined. To examine causal relationships to PAH, protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL) that influenced protein levels in the patient population were used as instruments for Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis.

Measurements and Main Results

From 4,152 annotated plasma proteins, levels of 208 differed between patients with PAH and healthy subjects, and 49 predicted long-term survival. MR based on cis-pQTL located in proximity to the encoding gene for proteins that were prognostic and distinguished PAH from health estimated an adverse effect for higher levels of netrin-4 (odds ratio [OR], 1.55; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.16–2.08) and a protective effect for higher levels of thrombospondin-2 (OR, 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74–0.94) on PAH. Both proteins tracked the development of PAH in previously healthy relatives and changes in thrombospondin-2 associated with pulmonary arterial pressure at disease onset.

Conclusions

Integrated analysis of the plasma proteome and genome implicates two secreted matrix-binding proteins, netrin-4 and thrombospondin-2, in the pathobiology of PAH.

Keywords: genome, protein quantitative trait loci, Mendelian randomization, case-control studies

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

The pathobiology of pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is characterized by a complex structural remodeling of pulmonary arteries and arterioles. The underlying biological processes are likely reflected in a perturbation of circulating proteins. Quantifying these changes in relation to inherited genetic variation in patients with PAH holds the promise of distinguishing cause from consequence and informing early molecular drivers of disease development.

What This Study Adds to the Field

This study, to our knowledge, provides the first comprehensive integration of proteomic and genomic data in patients with idiopathic or heritable PAH. We robustly identified plasma proteins that were different between patients and controls and that were associated with prognosis in a multicenter U.K. PAH cohort study. Common genetic variants conferring lifelong higher or lower plasma levels of these proteins served as instruments in Mendelian randomization analysis to infer proteins with a causal relation to PAH. The results suggest that therapeutic approaches to the management of PAH should consider inhibiting netrin-4 activity but support and enhance thrombospondin-2 activity.

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a rare condition characterized by an imbalance of vasoactive factors, inflammation, and disrupted cellular growth, leading to structural remodeling of pulmonary arteries and arterioles, increased resistance to pulmonary blood flow, and premature death from right heart failure (1). In patient registry and national audit databases, around 30–50% of PAH is classified as idiopathic, heritable, or drug-induced, and annual mortality in this group averages 10% (2). Despite common features in the vascular pathology on histological examination, there is evidence of heterogeneity within this patient subgroup, as seen in the individual response to specific drugs, for example, the response to calcium antagonists, and in the emerging underlying genetic architecture (3–5). The use of current therapies and the development of novel drugs would benefit from a better understanding of the molecular drivers of PAH (6).

The circulating proteome is a dynamic assembly at the equilibrium of the influx and efflux of proteins synthesized by tissues and cells across the body. It includes mediators of nonadjacent cell–cell and organ–organ communication, immune response, vascular tone, tissue repair, and fluid or nutrition exchange (7). An imbalance in the circulating proteome is an early hallmark of disease that is detectable in incident patients with PAH (8), and as such, changes in plasma protein levels can be used to explore the molecular drivers of disease. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) of plasma protein levels have identified variability due to common SNPs, establishing protein quantitative trait loci (pQTL) (9–11). Mendelian randomization (MR) analysis of pQTL is a powerful strategy for inferring a causal relationship between change in protein level and disease, particularly if a pQTL is located in proximity to the encoding gene (cis) (12, 13).

Here we report a comprehensive investigation of the plasma proteome of patients with idiopathic and heritable PAH recruited to a multicentre cohort study. From 4,152 annotated proteins, we select those where circulating levels robustly distinguish patients with PAH from healthy controls and where levels are associated with long-term survival. By triangulating these data with cis-pQTL, we reveal two proteins, netrin-4 and thrombospondin-2, that, based on MR analysis, are causally related to PAH.

Methods

Study Participants

Patients with idiopathic or heritable PAH aged 18–65 years (n = 357) were recruited between February 19, 2014, and November 6, 2018 from seven centers participating in the United Kingdom National Cohort Study of Idiopathic and Heritable PAH (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01907295). A subset of 262 patients was resampled at follow-up visits averaging 6 to 32 months apart (25–75% was 10.2–13.6). Unrelated volunteers (n = 103), self-declared as healthy and without a history of cardiovascular or respiratory disease, were recruited over the same period from the same centers. A separate 79 idiopathic or heritable patients with PAH were recruited at diagnosis (incident cases) from the EFORT (Evaluation of Prognostic Factors and Therapeutic Targets in PAH) study in France (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01185730) between January 11, 2011, and December 9, 2013. Relatives of patients with PAH (n = 23) were recruited from Hammersmith Hospital, London, United Kingdom, between February 14, 2012, and August 8, 2018, and from the French DELPHI-2 study between May 5, 2006, and April 7, 2013 (Clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01600898) (14).

The diagnostic criteria for idiopathic and heritable PAH over the course of this study have followed contemporary international guidelines; resting mean pulmonary arterial pressure ⩾25 mm Hg, pulmonary arterial wedge pressure <15 mm Hg, pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) ⩾3 Wood units, and exclusion of known associated diseases. Survival status in the United Kingdom cohort study was censored on March 14, 2020. After a median follow-up of 4.7 years, 65 deaths and 13 transplants had occurred (combined endpoint yielding 78 events).

Plasma samples were collected as previously described (15) with informed consent and research ethics committee approval (13/EE/0203, 17/LO/0563, and 17/LO/0565). Patients were not fasting and were sampled at their routine clinical appointment visits. Plasma samples underwent one freeze–thaw cycle to aliquot 120 μl for the proteomics assay. Clinical and biochemical data were collected within 30 days and 7 days, respectively, of blood sampling.

Plasma Proteome Assay

Proteomic analysis was performed using the SOMAscan version 4 assay (SomaLogic Inc.), and technicians were blinded to patient status. This assay includes 5,284 aptamers; after removal of aptamers for nonhuman/nonprotein targets and quality control (selecting those with stable measurements, defined as <20% coefficient of variance, compared with repeated pooled plasma assay controls), we had measurements for 4,349 aptamers targeting 4,152 distinct proteins for this study. Relative fluorescence units were log10-transformed to normalize protein levels, then residualized for the first two principal components (derived from all 4,349 proteins) by linear regression to correct for population stratification or sample quality differences. Finally, protein levels were standardized to levels in healthy controls for ease of interpretation of results and comparability of proteins (converted to z-scores using the mean and standard deviation in controls).

Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded human lung tissue blocks from idiopathic patients with PAH and unused non-PAH donors (n = 3 each) were sectioned (2 μm thickness), deparaffinized, and rehydrated. For immunohistochemistry, antigen retrieval was achieved through pressure cooking in Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) followed by bovine serum albumin (10%) blocking and anti-netrin–4 antibody incubation (1:25, HPA049832, Lot#R59752, Sigma-Aldrich). Netrin-4 protein expression was visualized via an alkaline phosphatase reaction using the ZytoChem-Plus AP Polymer-Kit (#POLAP-100, Zytomed Systems) and tissue counter-stained with hematoxylin.

Statistical Analysis

Patients and healthy controls were randomized into discovery and replication subgroups in a 2:1 ratio to provide adequately powered subgroups for discovery and replication analysis. Protein levels were compared between patients and healthy controls by logistic regression models, correcting for age and sex. Sensitivity analyses were performed to confirm that protein differences were independent of hemolysis (cell-free hemoglobin as a covariate), anticoagulation therapy (coagulation factor X), or renal function (cystatin-c). These markers were obtained through the same aptamer assay. Prognostic proteins were identified by Cox regression models, correcting for age and sex, with all-cause mortality or lung transplantation included as events (composite endpoint). All comparisons were corrected for multiple testing using the Benjamini-Hochberg method to control the false discovery rate (FDR). A threshold of q < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Whole-genome sequence data were accessed for patients with PAH through the United Kingdom NIHRBR (National Institute for Health Research BioResource) Rare Diseases study (16). A GWAS was performed for protein levels and autosomal variants with a minor allele frequency >1%. Prior to analysis, log-transformed protein levels were additionally adjusted for age, sex, and the first three principal components of genomic data in linear regression models. Residuals were then rank–inverse normalized. Genome-wide association testing was performed using an additive model in linear regression with the SNPTEST software tool (17). To account for multiple testing, we used a conservative Bonferroni-adjusted significance threshold of P < 1.5 × 10−11 (based on the number of aptamers included 5 × 10−8/4,349) for trans-acting loci. For cis-pQTL, which have a higher prior probability of association, we considered loci at the genome-wide significance threshold of P < 5 × 10−8 (10). We defined the cis-region as a ±500 kb window from the transcription start site of the encoding gene.

Additional pQTL were collated from three publicly available protein GWAS (9–11) of the general population and validated in our PAH cohort. Together with pQTL from our own GWAS, these were then pruned for linkage disequilibrium (LD) using European individuals from the 1,000 Genomes phase 3 as reference panel in the PLINK software tool (LD r2 < 0.001 within ±10 Mb) and used for downstream analyses.

In two-sample MR analysis, the lead variants at a given pQTL were used as instrument variables (exposure) and an international GWAS and meta-analysis of PAH as the outcome (4). The PAH GWAS meta-analysis combined genetic information from four separate GWAS comprising 11,744 individuals with European ancestry, including 2,085 cases with idiopathic or heritable PAH (4).

The Wald ratio method was applied to perform the MR analyses if the protein instrument (exposure) consisted only of a single variant, and the random-effects inverse–variance weighted method if two or more independent variants were available as implemented in the TwoSampleMR v0.5.3 R-package (18). Variants of the instrument variables (exposure) and outcome were harmonized on the positive strand, and allele frequencies were used for palindromic variants. We only considered variants that were directly called in the PAH GWAS.

To account for possible confounding through LD (pQTL being coinherited with nearby SNPs unrelated to protein regulation), we performed statistical colocalization and tested the hypothesis of a shared genetic signal as implemented in the coloc v5.1.0 R-package (19). Using the default prior probabilities, a posterior probability >80% was considered highly indicative for the presence of shared causal variants between a protein target and PAH.

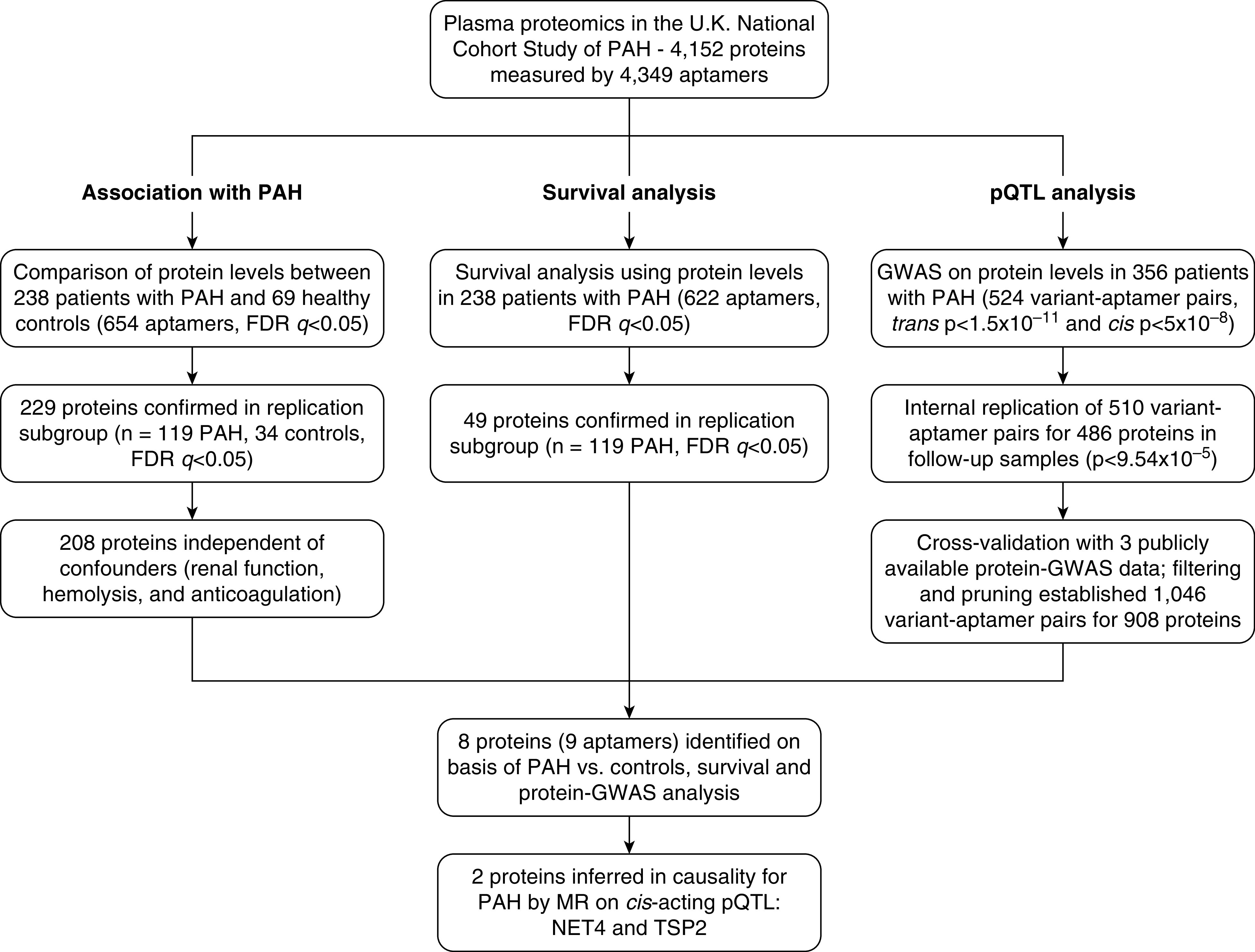

Results

The three analytic workflows used to identify proteins associated with PAH that relate to transplant-free survival and also exhibit genetic control (pQTL) leading to MR analysis are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Proteomics and genomics analytic workflow leading to the Mendelian randomization (MR) studies. FDR = false discovery rate; GWAS = genome-wide association studies; NET4 = netrin-4; PAH = pulmonary arterial hypertension; pQTL = protein quantitative trait loci; TSP2 = thrombospondin-2.

Association with PAH—Differences in the Plasma Proteome Between patients with PAH and Controls

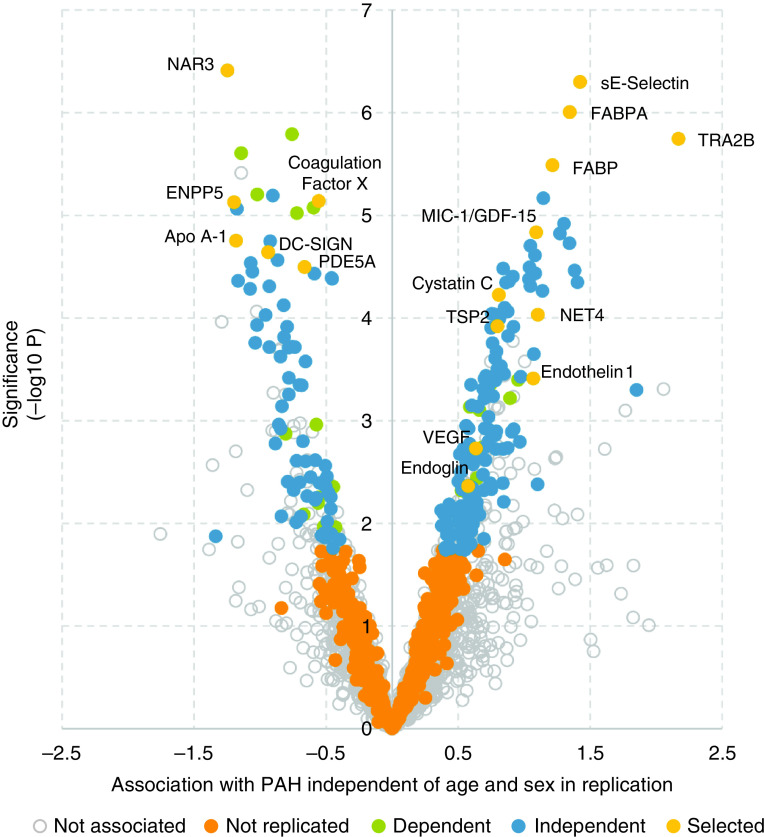

Details of the patients with PAH and healthy subjects that provided plasma samples are given in Table 1. In all, we tested 4,152 proteins (measured by 4,349 aptamers) for association with PAH using logistic regression models in discovery (n = 69 controls and n = 239 patients with PAH) and 654 aptamers in replication (n = 34 controls and n = 119 PAH patients), correcting for age and sex (Table 1). In recognition of the systemic consequences of PAH (20), we excluded 10 proteins associated with impaired renal function (exemplified by elevated cystatin C) and 11 due to anticoagulation treatment (exemplified by suppressed coagulation factor X). None were associated due to hemolysis (exemplified by cellular-free hemoglobin). We identified 208 proteins (measured by 215 aptamers) that were independently associated with PAH (FDR q < 0.05 in both discovery and replication (Figure 2 and Table E1 in the online supplement). Apart from PDE5 inhibitors and circulating PDE5A levels, no strong effect of the use of targeted PAH therapies on these 208 protein levels was observed (additional text in the online supplement and Figure E1).

Table 1.

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics of the Discovery and Replication Cohorts

| Discovery |

Replication |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Controls (n = 69) | Patients with PAH (n = 238) | Healthy Controls (n = 34) | Patients with PAH (n = 119) | ||

| Age at diagnosis/recruitment, yr | 31.7 (28.6–45.2) | 39.1 (30.4–47.9) | 37.0 (25.8–48.3) | 41.9 (33.8–49.5) | |

| Sex, n (%) | Female | 48 (70) | 177 (74) | 24 (71) | 86 (72) |

| Male | 21 (30) | 61 (26) | 10 (29) | 33 (28) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.2 (22.7–31.8) | 27.9 (24.3–31.6) | |||

| Idiopathic PAH, n (%) | 212 (89) | 109 (92) | |||

| Heritable PAH, n (%) | 22 (9) | 10 (8) | |||

| WHO functional class, n (%) | I | 3 (1) | 5 (4) | ||

| II | 45 (19) | 23 (19) | |||

| III | 146 (61) | 69 (58) | |||

| IV | 34 (14) | 16 (13) | |||

| 6-min-walk distance, m | 353 (260–421) | 352 (270–431) | |||

| Mean pulmonary artery pressure, mm Hg | 55 (48–65) | 54 (47–61) | |||

| Mean pulmonary artery wedge pressure, mm Hg | 9 (7–12) | 10 (7–11) | |||

| Mean right atrial pressure, mm Hg | 9 (6–13) | 8 (6–12) | |||

| Cardiac index, L/min/m2 | 2.0 (1.7–2.5) | 2.0 (1.6–2.7) | |||

| Pulmonary vascular resistance, dyn·s·cm−5 | 1,006 (659–1,350) | 817 (576–1,238) | |||

| Time from diagnosis to first sample, yr | 3.5 (1.0–7.9) | 4.4 (2.5–7.8) | |||

| Anticoagulation therapy, n (%) | 178 (75) | 88 (74) | |||

| PDE5 inhibitor, n (%) | 189 (79) | 92 (77) | |||

| Endothelin receptor antagonist, n (%) | 144 (61) | 71 (60) | |||

| Prostacyclin analogue, n (%) | 70 (29) | 27 (23) | |||

| Vasoresponsive CCB, n (%) | 16 (7) | 10 (8) | |||

| Dual therapy, n (%) | 112 (47) | 53 (45) | |||

| Triple therapy, n (%) | 36 (15) | 14 (12) | |||

| Type 1 or 2 diabetes, n (%) | 17 (7) | 11 (9) | |||

| Systemic hypertension, n (%) | 29 (12) | 27 (23) | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 6 (3) | 7 (6) | |||

| Asthma, n (%) | 23 (10) | 15 (12) | |||

| Coronary artery disease, n (%) | 6 (3) | 3 (3) | |||

Definition of abbreviations: BMI = body mass index; CCB = calcium channel blocker; PAH = pulmonary arterial hypertension; PDE = phosphodiesterase; WHO = World Health Organization.

Data are present as numbers with percentage or as median with interquartile range.

Figure 2.

Protein association with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) compared with healthy controls. A volcano plot of aptamers representing 208 independent proteins that met false discovery rate (FDR) (q < 0.05; blue dots) in both discovery and replication analysis. Dependent proteins were no longer associated after correcting for renal function or anticoagulation therapy. “Not replicated” proteins only met FDR in the discovery analysis, and those “Not associated” failed to meet FDR in discovery analysis. “Selected” proteins highlight proteins of interest in the pathology of PAH, which also met “independent” criteria.

Survival Analysis—Circulating Proteins Associated with Prognosis in PAH

Of the 4,152 proteins measured, 49 were associated with transplantation-free survival in Cox regression models adjusted for age and sex in patients with PAH (FDR q < 0.05 in both discovery and replication) (Table E2). This included known prognostic proteins, such as brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and angiopoietin-2 (Table E2).

pQTLs—Circulating Proteins Associated with Common Genetic Variation in patients with PAH

To identify pQTLs, we accessed GWAS data for 356 patients with PAH of European descent in our United Kingdom National PAH cohort (4). We identified 524 gene variants associated with aptamer levels (variant–aptamer pairs) in baseline samples, with a Bonferroni-adjusted significance threshold for trans-acting loci at P < 1.5 × 10−11 (5 × 10−8/4,349) and genome-wide significance P < 5 × 10−8 for cis-acting loci. We replicated 510 (targeting 486 distinct proteins) in separate longitudinal follow-up plasma samples (n = 262) from the same patient population (Bonferroni-adjusted significance P < 9.54 × 10−5 = 0.05/524). The effect sizes of aptamer–variant pairs were stable over time in the follow-up samples (Figure E2), and genomic characteristics of pQTL mirrored those observed in population-based studies (Figure E3).

We crosschecked our pQTL findings in three publicly available protein GWAS, namely the INTERVAL (9), KORA (10), and AGES (11) cohorts. Here, data were available for 393/510 variant–aptamer pairs discovered in our PAH cohort, while 117 variant–aptamer pairs (69 in cis and 48 in trans) identified in our PAH cohort were novel pQTL (additional text in the online supplement). Eighty-one percent (321/393) replicated with a Bonferroni-adjusted level of significance and concordant effect directions (Tables E3 and E4); conversely, from pQTL discovered in the population-based cohorts, we found that 1,377/2,467 (56%) were replicated in our PAH cohort at nominal significance and with concordant effect direction (P < 0.05) (Table E5). In sum, after filtering and pruning, we obtained 1,046 variant–aptamer pairs (660 cis and 386 trans) affecting the plasma levels of 908 distinct proteins in PAH (Figure 1 and Figure E4).

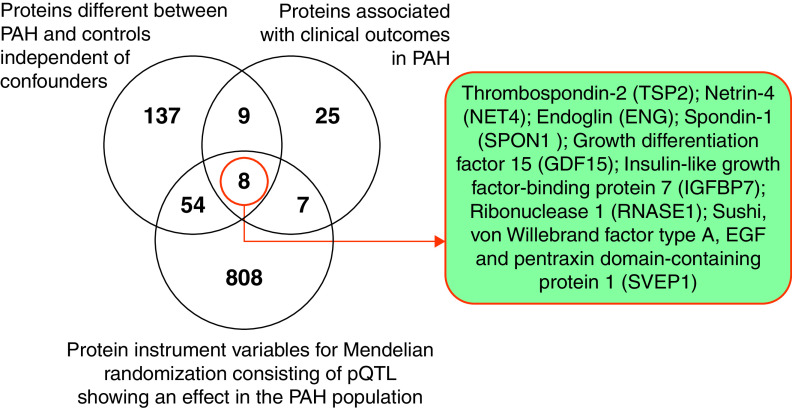

Association of pQTL with PAH

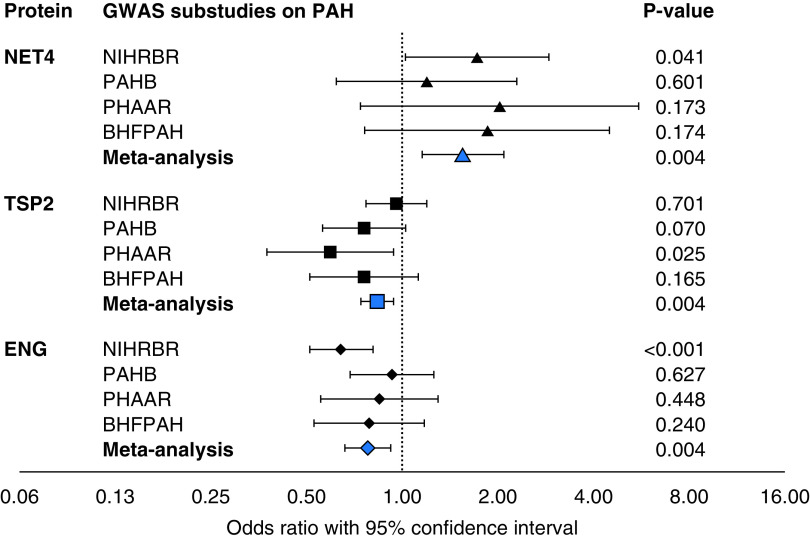

We identified eight proteins (measured by nine aptamers) that satisfied three criteria: they were 1) different between patients with PAH and healthy controls in our case-control comparison; 2) predicted survival in this patient population; and 3) had variant–aptamer pairs with significant effects in PAH as potential instruments for MR analysis (Figure 3). Following MR, three proteins revealed a causal effect on PAH at Bonferroni-adjusted level of significance (P < 0.0056 = 0.05/9); namely, NET4 (netrin-4, encoded by NTN4), TSP2 (thrombospondin-2, encoded by THBS2), and ENG (endoglin, encoded by ENG). MR estimated an adverse effect of higher circulating levels of NET4, while higher circulating levels of TSP2 and ENG were associated with a protective effect on PAH (Table 2). The directionality of MR for all three proteins was consistent across the international GWAS substudies (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Venn diagram shows the overlap between proteins that discriminate patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) from healthy control subjects, proteins associated with prognosis in PAH, and protein instruments for Mendelian randomization studies. pQTL = protein quantitative trait loci.

Table 2.

Results from Mendelian Randomization Studies on Three Circulating Proteins

| Mendelian Randomization Analysis on Risk of PAH* |

pQTL Variant |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein (Encoding Gene) | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | P Value | Genetic Variant | Effect Allele | MAF in PAH GWAS | MAF in gnomAD v2.1.1 | pQTL Location | Variant Mapping | |

| NET4 (NTN4) | 1.55 | 1.16 | 2.08 | 0.0035 | rs17288108 | A | 0.83 | 0.87 | CIS | Missense variant of NTN4 |

| TSP2 (THBS2) | 0.83 | 0.74 | 0.94 | 0.004 | rs73043857 | A | 0.90 | 0.90 | CIS | Intronic to THBS2 |

| Endoglin (ENG) | 0.78 | 0.66 | 0.92 | 0.0042 | rs651007 | T | 0.22 | 0.20 | TRANS | Upstream of ABO gene |

Definition of abbreviations: GWAS = genome-wide association study; MAF = minor allele frequency; NET4/NTN4 = netrin-4; PAH = pulmonary arterial hypertension; pQTL = protein quantitative trait loci; TSP2/THSB2 = thrombospondin-2.

Effect directions in Mendelian randomization analysis were harmonized to increasing circulating protein levels for the ease of comparison.

Figure 4.

A forest plot demonstrating shared effect directions of Mendelian randomization analyses on 3 protein quantitative trait loci performed separately in 4 genome-wide association study (GWAS) substudies on pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) contributing to the GWAS meta-analysis. An odds ratio above 1 indicates an increasing risk for PAH with an increase in protein level. BHFPAH = British Heart Foundation PAH study; NIHRBR = United Kingdom National Institute for Health Research BioResource Rare Diseases study; PAHB = U.S. National Biological Sample and Data Repository for PAH, also known as the “PAH Biobank”; PHAAR = Pulmonary Hypertension Allele-associated Risk study.

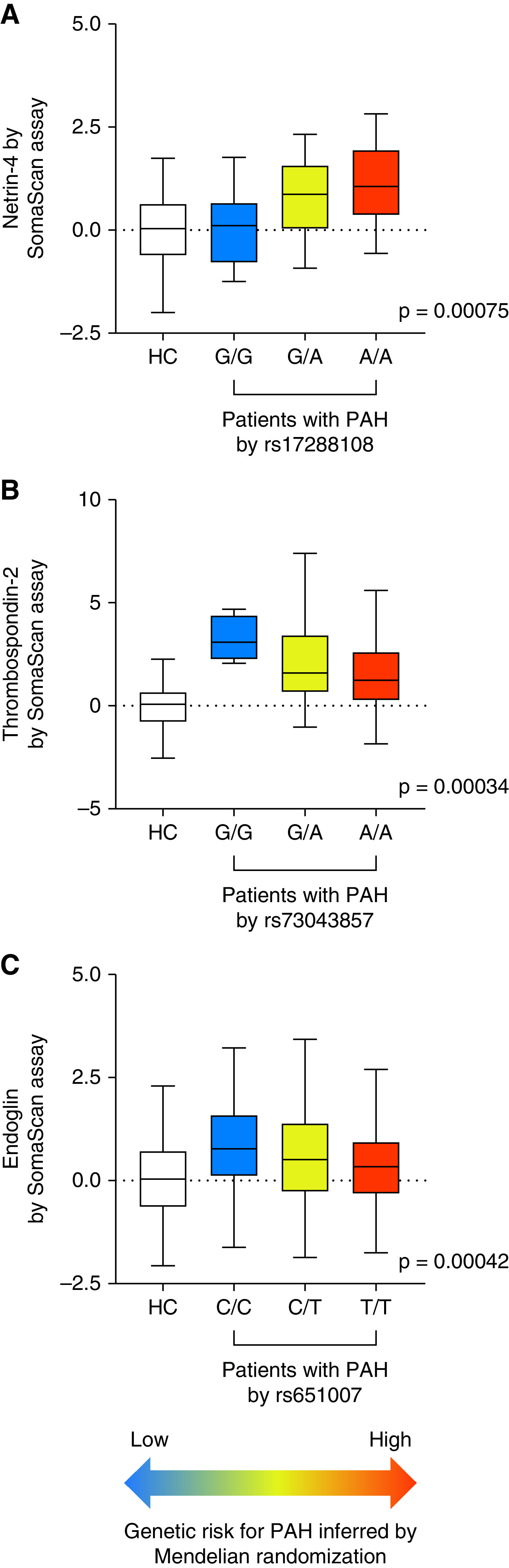

The pQTL for all three proteins, NET4, TSP2, and ENG, were discovered in general population cohorts (9–11) and clearly influenced protein levels in the PAH population (Figure 5). A cis relation is considered to have high biological relevance, is less influenced by horizontal pleiotropy, and indicates the specificity of target quantification (12, 13). While the NET4 and TSP2 pQTL were cis, the pQTL for ENG was in trans and located in proximity to the pleiotropic ABO gene locus (Table 2 and Figure 5). We, therefore, focused on NET4 and TSP2 for downstream analyses. Colocalization of the same causal variant was highly likely between both cis-pQTL and PAH (posterior probability, 96.6% for NET4 and 90.7% for TSP2) (Figure E5) and the lead variants at these two loci, NET4-rs17288108 and TSP2-rs73043857, also associate with respective mRNA levels in arterial vessels (Table E6).

Figure 5.

Genetic risk for pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) inferred from levels of netrin-4 (NET4), thrombospondin-2 (TSP2), and endoglin (ENG) in Mendelian randomization analysis. (A) Box plots of NET4 levels in controls and patients with PAH stratified by genotype at rs17288108, (B) TSP2 levels by genotype at rs73043857, and (C) ENG levels by genotype at rs651007. Protein levels were z-scored to mean and standard deviation in controls for ease of comparison. Color scheme indicates genetic risk for PAH inferred from Mendelian randomization. P values provide the strength of association between protein levels and genotypes in patients with PAH. HC references distribution in healthy controls.

Reproducibility of Protein–PAH Relationships for NET4 and TSP2

The protein quantification of NET4 and TSP2 by aptamer-based measurements was consistent across the seven contributing United Kingdom centers in both patients with PAH and healthy controls. Levels in patients with PAH from each center were above those found in controls with comparable odds ratios (Figure E6 and Table E7). Additionally, levels of both proteins showed similar differences to controls in the French EFORT study comprising 79 incident patients with PAH (Figure E6). The patients with PAH in the EFORT study were slightly older and had a lower mean pulmonary arterial pressure and PVR and a higher confidence interval (CI). In these patients, the plasma levels of TSP2 correlated directly with PVR and right atrial pressure and inversely with cardiac index, while NET4 levels correlated with right atrial pressure (all P < 0.05).

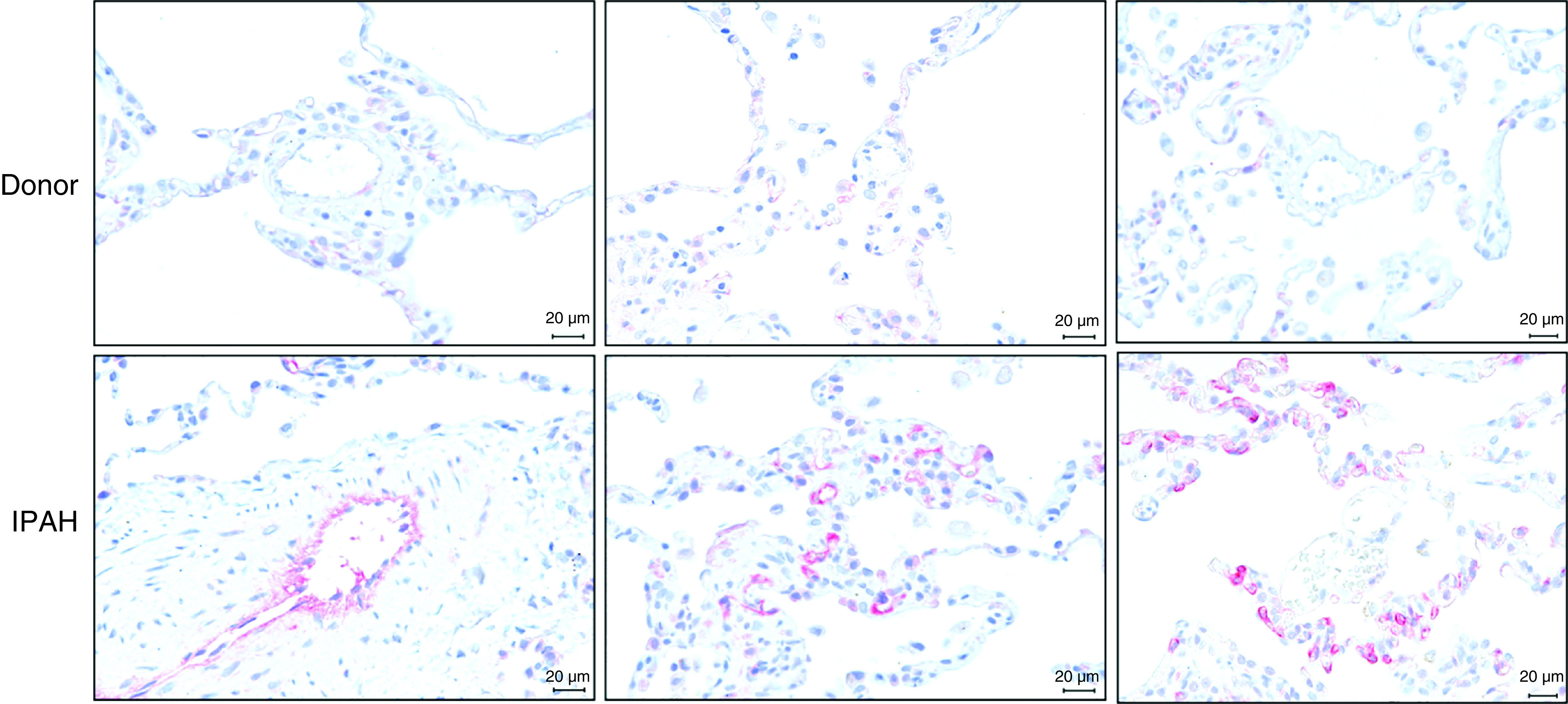

Increased TSP2 expression in microdissected pulmonary arteries has been documented previously in patients with PAH (21). We observed increased immunoreactivity for NET4 in distal pulmonary vessels in lung sections from patients with PAH (Figure 6 and Figure E7).

Figure 6.

Increased NET4 (Netrin-4) protein expression in human idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) lungs. Immunohistochemical NET4 staining in human non-PAH donor (upper panel) and IPAH (lower panel) lung sections, demonstrating increased NET4 protein expression in distal pulmonary vessels of patients with IPAH. n = 3 patients and 3 donors. Scale bars, 20 μm.

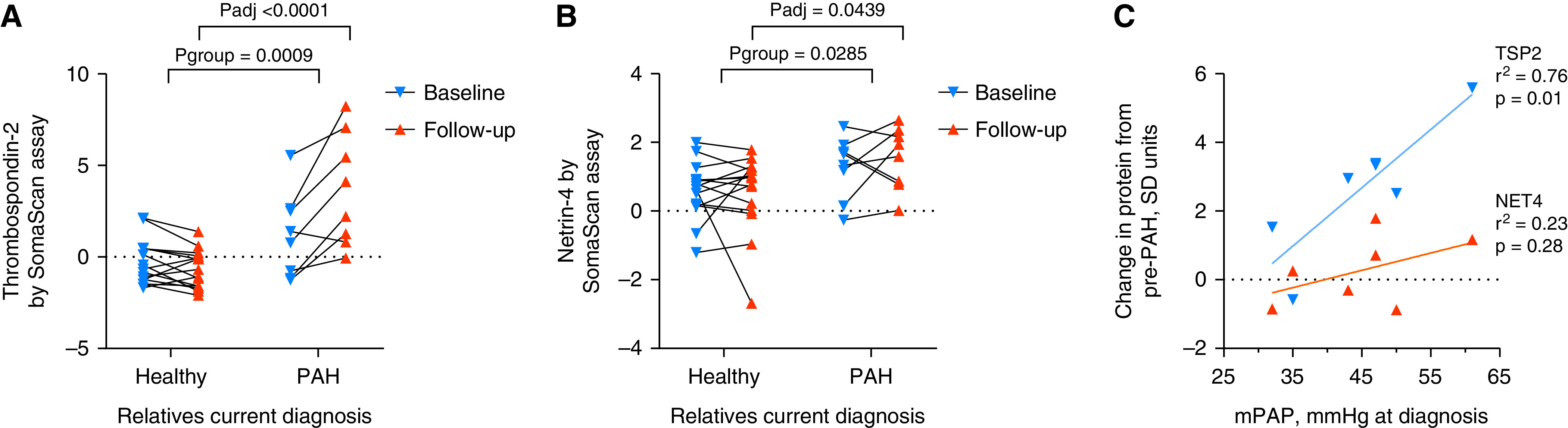

Tracking Development of PAH in Healthy Relatives for NET4 and TSP2

To investigate the role of NET4 and TSP2 during the onset of the disease, we analyzed serial plasma samples from relatives at risk of developing PAH. The relatives (18/23 female, median age 27 years, interquartile range [IQR], 19–43) were resampled after 20 months (IQR, 13–38). Relatives developing PAH (n = 8) had significantly higher levels of NET4 and TSP2 in their follow-up samples compared with relatives who remained healthy at the time of follow-up sampling (n = 15; P < 0.05) (Figure 7). The change in levels of TSP2 from baseline to follow-up samples associated significantly with mean pulmonary arterial pressure at diagnostic catheterization (P = 0.011) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

(A and B) Thrombospondin-2 (TSP2) and netrin-4 (NET4) plasma levels in paired samples from relatives (n = 8) who developed pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) during follow-up compared with those (n = 15) who remained healthy. (C) Relationship of change in protein level from the diagnostic visit to mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) measured at diagnostic catheterization. P values in A and B based on two-way repeated measures ANOVA (Pgroup) with Šídák's multiple comparisons test (Padj). R-squared and P value in C derived from linear regression models.

Discussion

We present a systematic analysis of the plasma proteome in a multicentre cohort of patients with idiopathic or heritable PAH followed over a median of 4.7 years. We identified eight proteins where circulating levels discriminate PAH from health, carry prognostic information, and show genetic control through pQTL in our PAH cohort. MR using these pQTL and an international PAH GWAS meta-analysis suggested three of these as causally related: NET4, TSP2, and ENG. Circulating levels of NET4 and TSP2 are influenced by robust cis-acting pQTL and tracked the onset of PAH in relatives in clinical follow-up. All three proteins, NET4, TSP2, and ENG, are biologically plausible candidates for a role in pulmonary vascular disease.

NET4 is a secreted protein, highly expressed in vascular endothelium and upregulated by laminar shear stress (22). Functionally, it has been shown to modulate angiogenic activity in a variety of experimental models, but an association with pulmonary hypertension is novel (23, 24). Plasma levels were elevated in our patients with PAH an observation supported by increased immunoreactivity in distal pulmonary vessels in lung sections from patients with PAH and associated with a poor prognosis. The consistent directionality in MR analysis and colocalization provide support for a causative association between elevated plasma levels and PAH. Recent structural biology and kinetic binding studies suggest that NET4 does not bind to the canonical receptors in the netrin family (25). Rather, the angiogenic effects of NET4 may depend, at least at higher concentrations, on direct binding to extracellular matrix components, such as laminin γ1 chains in the basement membrane (25, 26) or integrin α6β1, the main receptor for vascular laminins on endothelial cells (27). High-affinity binding of NET4 to laminin could potentially disrupt preexisting laminin networks and impair the integrity of the endothelial basement membrane and vessel wall (25).

TSP2 is a secreted matricellular protein with affinity for both extracellular matrix and cell surface receptors. As a family, thrombospondins have been implicated in a variety of cardiovascular diseases, including pulmonary hypertension (28). Most studies have focused on the role of TSP1 (thrombospondin-1) in pulmonary hypertension, although changes in the expression of TSP2 have been reported in the pulmonary arteries of patients with pulmonary hypertension with interstitial pulmonary fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (21). Loss-of-function mutations in THBS1, which encodes TSP1, have been reported in three families with PAH (29). Raised plasma TSP2 levels, but not TSP1, are associated with a poor prognosis in PAH in our dataset. Previous proteomic studies (using the SomaLogic 1129 protein assay) have observed elevated circulating TSP2 levels in heart failure (30–32). The direction of the relationship in our MR analysis suggests that TSP2 is protective. Indeed, TSP2 has an essential role in maintaining matrix integrity and adaptation to hemodynamic stress (30, 31). While the MR may seem at odds with the relationship of plasma levels to prognosis, an analogy can be found with NT-proBNP/BNP. Elevated levels of NT-proBNP/BNP are associated with a poor prognosis but raised plasma levels are interpreted as an ameliorating compensatory response. Common genetic variation in the locus encoding BNP that showed association with increased circulating BNP levels infers a decreased cardiovascular risk, and recombinant BNP is used as a therapeutic agent in heart failure (33, 34).

Relatives of patients with PAH are at increased risk of developing the condition (14). Plasma levels of NET4 and TSP2 increased in 8 relatives who developed PAH during follow-up but remained stable in 15 who remained healthy at the time of follow-up sampling (median time 20 mo). Genotype data are helpful in identifying relatives at risk of PAH, but disease penetrance is low. The elevation of both NET4 and TSP2 in tandem with the development of disease in previously healthy relatives emphasize these are not markers of late-stage disease and could represent pathways that are likely involved in the pathobiology of PAH at an early stage. As such, these proteins may have utility in the early detection of PAH in people at risk, but a prospective study of such individuals would be needed to evaluate this.

ENG is a homodimeric transmembrane glycoprotein that is strongly expressed on vascular endothelial cells and released upon cleavage of its extracellular domain. Plasma-soluble endoglin levels increase in PAH, and histological studies show increased staining for the protein in the small vessels and plexiform lesions in lungs from patients with PAH (35, 36). Consistent with our findings, others have found that elevated soluble endoglin levels are associated with a poor clinical outcome (35). Loss-of-function mutations in ENG are associated with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia and PAH (37–39); thus, elevated endoglin levels, as with elevated TSP2 and NT-proBNP/BNP, likely reflect an attempt to protect the vascular endothelium as opposed to disrupting it. Levels of ENG associate with the trans-acting and pleiotropic ABO gene locus, which has previously mediated the causal inferences of circulating proteins in common cardiovascular disease (40, 41).

MR studies based on pQTL offer a powerful tool for interpreting the relationship between the plasma level of a protein and the disease; they sits between observational and interventional studies in strength of evidence (9, 10, 40, 41). The use of cis instruments, where the genetic variants are located in proximity to the encoding gene, is less prone to violation of the horizontal pleiotropy assumption than the use of trans instruments and can be referred to as “locus-specific” MR, with the potential to inform druggable protein targets (12, 13). Large-scale pQTL datasets derived from mostly healthy individuals are now publicly available, establishing a catalog of instruments for MR (9–11). We replicated 1,377 pQTL in our PAH cohort, showed the stability of pQTL in follow-up plasma samples, and identified 117 new variant–aptamer pairs. Some, such as a cis-pQTL for STAT3, a target of interest in PAH (42, 43), reached only nominal statistical significance in publicly available databases of healthy volunteers but met threshold significance in PAH. This underscores the potential value of using disease cohorts where homeostatic systems are stressed to identify pQTL and prioritize pathways of interest for drug development.

A criticism of the aptamer assay platform used in this study is that some aptamers may have inherent biases that affect binding properties influencing the detection and measurement of, for example, protein complexes with altered tertiary structure, electric charge, amino acid substitution, or crossreactivity. Proteins with cis-acting pQTL are less exposed to biases regarding the binding specificity as genetic association with a circulating protein to a locus near the respective encoding gene intuitively supports binding specificity. Binding specificity is further supported by the lack of crossreactivity for all three aptamers with homologous proteins (e.g., netrin-1 and thrombospondin-1) and, for TSP2, by correlation of aptamer-based protein quantification (identical aptamer) with antibody-based assays in plasma samples and by mass spectrometry after aptamer-based enrichment from cell lysates (9, 11). The possibility of binding-affinity effects could still occur for a cis-locus through protein-altering variants due to differential binding rather than differences in protein abundance, but the observation that the cis-pQTL for NET4 and TSP2 influences not only protein levels but also gene expression addresses this concern. A further consideration is that, although we adjusted for age and sex in each model, residual confounding through demographic or clinical factors remains a possibility. With the increasing use of large population data, further pQTL will be identified and available as instruments for genetic inference, but access to larger PAH GWAS datasets will also be needed. In the current pooled PAH GWAS dataset, the component substudies shared the direction of effect but lacked the power to replicate the odds ratios and CIs for each genetic instrument; increased cohort sample sizes would address this.

Conclusions

We present the largest analysis of circulating proteins in PAH to date and identified new pQTL revealed by the analyses in disease samples. MR analysis of protein targets advocated strongly by our observational associations suggests that therapeutic interventions that inhibit NET4 activity and augment TSP2 activity may be beneficial in this rare condition. This is supported by serial measurements in relatives at risk for heritable PAH, where changes in NET4 and TSP2 levels reported the onset of the disease.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank all the patients and their families who contributed to this research and the United Kingdom Pulmonary Hypertension Association for their support.

UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) BioResource Rare Diseases Consortium: Southgate L1, Machado RD43, Martin J46, Ouwehand WH50, US Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Biobank Consortium: Pauciulo MW3, Arora A5, Lutz K3, Ahmad F9, Archer SL11, Argula R12, Austin ED13, Badesch D14, Bakshi S15, Barnett C16, Benza R17, Bhatt N18, Burger CD20, Chakinala M21, Elwing J29, Fortin T30, Frantz RP32, Frost A33, Garcia JGN34, Harley J36, He H3, Hill NS37, Hirsch R38, Ivy D39, Klinger J40, Lahm T42, Marsolo K45, Martin LJ3, Nathan SD48, Oudiz RJ49, Rehman Z52, Robbins I53, Roden DM53, Rosenzweig EB54, Saydain G55, Schilz R56, Simms RW57, Simon M58, Tang H34, Tchourbanov AY60, Thenappan T61, Torres F62, Walsworth AK3, Walter RE63, White RJ64, Wilt J65, Yung D66, Kittles R67, UK Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Cohort Study Consortium: Aman J4, Knight J6, Hanscombe KB7, Gall H8, Ulrich A4, Bogaard HJ19, Church C22, Coghlan JG23, Condliffe R24, Corris PA25, Danesino C26, Elliott CG28, Franke A31, Ghio S35, Gibbs JSR4, Houweling AC19, Kovacs G41, Laudes M31, MacKenzie Ross RV44, Moledina S47, Newnham M46, Olschewski A41, Olschewski H41, Peacock AJ22, Pepke-Zaba J51, Scelsi L35, Seeger W8, Shaffer CM53, Sitbon O59, Suntharalingam J44, Treacy C46, Vonk Noordegraaf A19, Waisfisz Q19, Wort SJ4, Trembath RC7, Other independent collaborators: Germain M2, Cebola I4, Ferrer J4, Amouyel P10, Debette S27, Eyries M2, Soubrier F2, Trégouët DA2, (1) Molecular and Clinical Sciences Research Institute, St George's University of London, London, UK. (2) Sorbonne Universités, UPMC, INSERM, Paris, France. (3) Division of Human Genetics, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, Cincinnati, OH, USA. (4) National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, London, UK. (5) Department of Surgery, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. (6) Data Science Institute, Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK. (7) Genetics and Molecular Medicine, King's College London, London, UK. (8) University of Giessen and Marburg Lung Center, Giessen, Germany. (9) University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, USA. (10) University of Lille, Lille, France. (11) Queen's University, Kingston, ON, Canada. (12) Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC, USA. (13) Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA. (14) University of Colorado, Denver, CO, USA. (15) Baylor Research Institute, Plano, TX, USA. (16) Medstar Health, Washington, DC, USA. (17) Allegheny-Singer Research Institute, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. (18) Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. (19) VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, Netherlands. (20) Mayo Clinic Florida, Jacksonville, FL, USA. (21) Washington University, St Louis, MO, USA. (22) Golden Jubilee National Hospital, Glasgow, UK. (23) Royal Free Hospital, London, UK. (24) Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield, UK. (25) University of Newcastle, Newcastle, UK. (26) University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy. (27) University of Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France. (28) Intermountain Medical Center, Murray, UT, USA. (29) University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati OH, USA. (30) Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC, USA. (31) University of Kiel, Kiel, Germany. (32) Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA. (33) Houston Methodist Research Institute, Houston, TX, USA. (34) Department of Medicine, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA. (35) Fondazione IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Pavia, Italy. (36) Center for Autoimmune Genomics and Etiology (CAGE), Cincinnati, OH, USA. (37) Tufts-New England Medical Center, Boston, MA, USA. (38) University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati OH, USA. (39) Health Sciences Center, University of Colorado, Aurora, CO, USA. (40) Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI, USA. (41) Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Lung Vascular Research, Graz, Austria. (42) Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN, USA. (43) University of Lincoln, Lincoln, UK. (44) Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust, Bath, UK. (45) Biomedical Informatics, Cincinnati, OH, USA. (46) Department of Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. (47) Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, UK. (48) Inova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, VA, USA. (49) Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Torrance, CA, USA. (50) Department of Haematology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK. (51) Royal Papworth Hospital, Cambridge, UK. (52) East Carolina University, Greenville, NC, USA. (53) Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, USA. (54) Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. (55) Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA. (56) University Hospital of Cleveland, Cleveland, OH, USA. (57) Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA. (58) University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. (59) University Paris-Sud, Université Paris-Saclay, Le Kremlin-Bicêtre, Paris, France. (60) Ambry Genetics, Aliso Viejo, CA, USA. (61) University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA. (62) University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA. (63) Louisiana State University Health, Shreveport, LA, USA. (64) University of Rochester Medical Center, Rochester, NY, USA. (65) Spectrum Health Hospitals, Grand Rapids, MI, USA. (66) Seattle Children's Hospital, Seattle, WA, USA. (67) City of Hope, Duarte, CA, USA.

Footnotes

A complete list of United Kingdom National Institute for Health Research BioResource Rare Diseases Consortium, United Kingdom Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Cohort Study Consortium, and U.S. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Biobank Consortium members may be found before the beginning of the References.

Supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) through the NIHR BioResource (NIHRBR) Rare Diseases study and the Imperial NIHR Clinical Research Facility. The authors acknowledge the use of BRC Core Facilities provided by financial support from the United Kingdom Department of Health via the NIHR comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre award to Imperial College Healthcare National Health Service (NHS) Trust, Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, and Guy’s and St. Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King’s College London and King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust. Sheffield NIHR Clinical Research Facility award to Sheffield Teaching Hospitals Foundation NHS Trust. The United Kingdom National Cohort of Idiopathic and Heritable Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH) is supported by the NIHRBR, the British Heart Foundation (BHF) (SP/12/12/29836), and the United Kingdom Medical Research Council (MR/K020919/1). The authors also gratefully acknowledge the participation of patients recruited to the US NIH/NHLBI-sponsored National Biological Sample and Data Repository for PAH (also known as PAH Biobank; HL105333). This work was supported in part by the Assistance Publique-Hopitaux de Paris, INSERM, Université, Paris-Sud, and Agence Nationale de la Recherche (Departement Hospitalo-Universitaire Thorax Innovation; LabEx LERMIT, ANR-10-LABX-0033; and RHU BIO-ART LUNG 2020, ANR-15-RHUS-0002). The DELPHI-2 Study was funded by the French Ministry of Social Affairs and Health (PHRC P100175) and supported by the French Pulmonary Hypertension Patient Association (HTaPFrance), Chancellerie des Universités, Legs Poix, France, and a Pulmonary Hypertension Grants Program 2013 from Bayer, and the European Respiratory Society (grant LTRF-2013-1592). L.H. is a recipient of the European Respiratory Society Fellowship (LTRF 2016–6884). C.J.R. is supported by a BHF Intermediate Basic Science Research fellowship (FS/15/59/31839) and Academy of Medical Sciences Springboard fellowship (SBF004\1095). A.L. is supported by a BHF Senior Basic Science Research fellowship (FS/13/48/30453 & FS/18/52/33808). M.R.W. is supported by the BHF Imperial Research Centre of Excellence (RE/18/4/34215). M.R.W., M.B., T.N., R.T.S., and H.A.G. receive funding from German Research Foundation (DFG) SFB1213, project A08, A09, B04, and B09. The popgen 2.0 network is supported by a grant from the German Ministry for Education and Research (01EY1103). W.C.N. is funded by NIH/NHLBI (HL105333). A.A.D. is supported by National Institute of Health/National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NIH/NHLBI R01HL136603). J.H.K. is funded by NIH/NHLBI (R01HL158686 and K01HL143137).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: L.H., C.J.R., J.W., M.H., O.S., M.B., R.T.S., and M.R.W. Data curation: L.H., C.J.R., J.W., M.B., E.M.S., and S.G. Formal analysis and writing of original draft: L.H., C.J.R. and M.R.W. Data acquisition, data interpretation, and writing (review and editing): all authors. L.H., C.J.R., J.W., O.S., M.H., M.B., R.T.S., E.M.S., and M.R.W. have had access to and verified the data used in this article.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202109-2106OC on April 7, 2022

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

Contributor Information

for the U.K. National Institute for Health Research BioResource Rare Diseases Consortium, U.K. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Cohort Study Consortium, and U.S. Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Biobank Consortium:

L Southgate, RD Machado, J Martin, WH Ouwehand, MW Pauciulo, A Arora, K Lutz, F Ahmad, SL Archer, R Argula, ED Austin, D Badesch, S Bakshi, C Barnett, R Benza, N Bhatt, CD Burger, M Chakinala, J Elwing, T Fortin, RP Frantz, A Frost, JGN Garcia, J Harley, H He, NS Hill, R Hirsch, D Ivy, J Klinger, T Lahm, K Marsolo, LJ Martin, SD Nathan, RJ Oudiz, Z Rehman, I Robbins, DM Roden, EB Rosenzweig, G Saydain, R Schilz, RW Simms, M Simon, H Tang, AY Tchourbanov, T Thenappan, F Torres, AK Walsworth, RE Walter, RJ White, J Wilt, D Yung, R Kittles, J Aman, J Knight, KB Hanscombe, H Gall, A Ulrich, HJ Bogaard, C Church, JG Coghlan, R Condliffe, PA Corris, C Danesino, CG Elliott, A Franke, S Ghio, JSR Gibbs, AC Houweling, G Kovacs, M Laudes, RV MacKenzie Ross, S Moledina, M Newnham, A Olschewski, H Olschewski, AJ Peacock, J Pepke-Zaba, L Scelsi, W Seeger, CM Shaffer, O Sitbon, J Suntharalingam, C Treacy, A Vonk Noordegraaf, Q Waisfisz, SJ Wort, RC Trembath, M Germain, I Cebola, J Ferrer, P Amouyel, S Debette, M Eyries, F Soubrier, and DA Trégouët

References

- 1. Humbert M, Guignabert C, Bonnet S, Dorfmüller P, Klinger JR, Nicolls MR, et al. Pathology and pathobiology of pulmonary hypertension: state of the art and research perspectives. Eur Respir J . 2019;53:1801887. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01887-2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: the Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) Eur Heart J . 2016;37:67–119. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gräf S, Haimel M, Bleda M, Hadinnapola C, Southgate L, Li W, et al. Identification of rare sequence variation underlying heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Commun . 2018;9:1416. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03672-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rhodes CJ, Batai K, Bleda M, Haimel M, Southgate L, Germain M, et al. UK NIHR BioResource Rare Diseases Consortium; UK PAH Cohort Study Consortium; US PAH Biobank Consortium Genetic determinants of risk in pulmonary arterial hypertension: international genome-wide association studies and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med . 2019;7:227–238. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(18)30409-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhu N, Pauciulo MW, Welch CL, Lutz KA, Coleman AW, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, et al. PAH Biobank Enrolling Centers’ Investigators Novel risk genes and mechanisms implicated by exome sequencing of 2572 individuals with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Genome Med . 2019;11:69. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0685-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oldham WM, Hemnes AR, Aldred MA, Barnard J, Brittain EL, Chan SY, et al. NHLBI-CMREF workshop report on pulmonary vascular disease classification: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2021;77:2040–2052. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2021.02.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Schwenk JM, Omenn GS, Sun Z, Campbell DS, Baker MS, Overall CM, et al. The human plasma proteome draft of 2017: building on the human plasma peptideatlas from mass spectrometry and complementary assays. J Proteome Res . 2017;16:4299–4310. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rhodes CJ, Wharton J, Ghataorhe P, Watson G, Girerd B, Howard LS, et al. Plasma proteome analysis in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: an observational cohort study. Lancet Respir Med . 2017;5:717–726. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30161-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sun BB, Maranville JC, Peters JE, Stacey D, Staley JR, Blackshaw J, et al. Genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome. Nature . 2018;558:73–79. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0175-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Suhre K, Arnold M, Bhagwat AM, Cotton RJ, Engelke R, Raffler J, et al. Connecting genetic risk to disease end points through the human blood plasma proteome. Nat Commun . 2017;8:14357. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Emilsson V, Ilkov M, Lamb JR, Finkel N, Gudmundsson EF, Pitts R, et al. Co-regulatory networks of human serum proteins link genetics to disease. Science . 2018;361:769–773. doi: 10.1126/science.aaq1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schmidt AF, Finan C, Gordillo-Marañón M, Asselbergs FW, Freitag DF, Patel RS, et al. Genetic drug target validation using Mendelian randomisation. Nat Commun . 2020;11:3255. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16969-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zheng J, Haberland V, Baird D, Walker V, Haycock PC, Hurle MR, et al. Phenome-wide Mendelian randomization mapping the influence of the plasma proteome on complex diseases. Nat Genet . 2020;52:1122–1131. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-0682-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Montani D, Girerd B, Jaïs X, Savale L, Laveneziana P, Lau E, et al. Screening of pulmonary arterial hypertension in BMPR2 mutation carriers. Eur Respir J . 2020;56:4460. doi: 10.1183/13993003.04229-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rhodes CJ, Ghataorhe P, Wharton J, Rue-Albrecht KC, Hadinnapola C, Watson G, et al. Plasma metabolomics implicates modified transfer RNAs and altered bioenergetics in the outcomes of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation . 2017;135:460–475. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Turro E, Astle WJ, Megy K, Gräf S, Greene D, Shamardina O, et al. NIHR BioResource for the 100,000 Genomes Project Whole-genome sequencing of patients with rare diseases in a national health system. Nature . 2020;583:96–102. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2434-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat Genet . 2007;39:906–913. doi: 10.1038/ng2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hemani G, Zheng J, Elsworth B, Wade KH, Haberland V, Baird D, et al. The MR-Base platform supports systematic causal inference across the human phenome. eLife . 2018;7:e34408. doi: 10.7554/eLife.34408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Giambartolomei C, Vukcevic D, Schadt EE, Franke L, Hingorani AD, Wallace C, et al. Bayesian test for colocalisation between pairs of genetic association studies using summary statistics. PLoS Genet . 2014;10:e1004383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rosenkranz S, Howard LS, Gomberg-Maitland M, Hoeper MM. Systemic consequences of pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure. Circulation . 2020;141:678–693. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hoffmann J, Wilhelm J, Marsh LM, Ghanim B, Klepetko W, Kovacs G, et al. Distinct differences in gene expression patterns in pulmonary arteries of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2014;190:98–111. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201401-0037OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zhang H, Vreeken D, Bruikman CS, van Zonneveld AJ, van Gils JM. Understanding netrins and semaphorins in mature endothelial cell biology. Pharmacol Res . 2018;137:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lejmi E, Leconte L, Pédron-Mazoyer S, Ropert S, Raoul W, Lavalette S, et al. Netrin-4 inhibits angiogenesis via binding to neogenin and recruitment of Unc5B. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2008;105:12491–12496. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804008105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lambert E, Coissieux MM, Laudet V, Mehlen P. Netrin-4 acts as a pro-angiogenic factor during zebrafish development. J Biol Chem . 2012;287:3987–3999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.289371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Reuten R, Patel TR, McDougall M, Rama N, Nikodemus D, Gibert B, et al. Structural decoding of netrin-4 reveals a regulatory function towards mature basement membranes. Nat Commun . 2016;7:13515. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Reuten R, Zendehroud S, Nicolau M, Fleischhauer L, Laitala A, Kiderlen S, et al. Basement membrane stiffness determines metastases formation. Nat Mater . 2021;20:892–903. doi: 10.1038/s41563-020-00894-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Larrieu-Lahargue F, Welm AL, Thomas KR, Li DY. Netrin-4 activates endothelial integrin alpha6beta1. Circ Res . 2011;109:770–774. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rogers NM, Sharifi-Sanjani M, Yao M, Ghimire K, Bienes-Martinez R, Mutchler SM, et al. TSP1-CD47 signaling is upregulated in clinical pulmonary hypertension and contributes to pulmonary arterial vasculopathy and dysfunction. Cardiovasc Res . 2017;113:15–29. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvw218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Maloney JP, Stearman RS, Bull TM, Calabrese DW, Tripp-Addison ML, Wick MJ, et al. Loss-of-function thrombospondin-1 mutations in familial pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2012;302:L541–L554. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00282.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wells QS, Gupta DK, Smith JG, Collins SP, Storrow AB, Ferguson J, et al. Accelerating biomarker discovery through electronic health records, automated biobanking, and proteomics. J Am Coll Cardiol . 2019;73:2195–2205. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.01.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Egerstedt A, Berntsson J, Smith ML, Gidlöf O, Nilsson R, Benson M, et al. Profiling of the plasma proteome across different stages of human heart failure. Nat Commun . 2019;10:5830. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-13306-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chan MY, Efthymios M, Tan SH, Pickering JW, Troughton R, Pemberton C, et al. Prioritizing candidates of post-myocardial infarction heart failure using plasma proteomics and single-cell transcriptomics. Circulation . 2020;142:1408–1421. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.045158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Newton-Cheh C, Larson MG, Vasan RS, Levy D, Bloch KD, Surti A, et al. Association of common variants in NPPA and NPPB with circulating natriuretic peptides and blood pressure. Nat Genet . 2009;41:348–353. doi: 10.1038/ng.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Goetze JP, Bruneau BG, Ramos HR, Ogawa T, de Bold MK, de Bold AJ. Cardiac natriuretic peptides. Nat Rev Cardiol . 2020;17:698–717. doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0381-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Malhotra R, Paskin-Flerlage S, Zamanian RT, Zimmerman P, Schmidt JW, Deng DY, et al. Circulating angiogenic modulatory factors predict survival and functional class in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pulm Circ . 2013;3:369–380. doi: 10.4103/2045-8932.110445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Owen NE, Alexander GJ, Sen S, Bunclark K, Polwarth G, Pepke-Zaba J, et al. Reduced circulating BMP10 and BMP9 and elevated endoglin are associated with disease severity, decompensation and pulmonary vascular syndromes in patients with cirrhosis. EBioMedicine . 2020;56:102794. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McAllister KA, Grogg KM, Johnson DW, Gallione CJ, Baldwin MA, Jackson CE, et al. Endoglin, a TGF-beta binding protein of endothelial cells, is the gene for hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia type 1. Nat Genet . 1994;8:345–351. doi: 10.1038/ng1294-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Trembath RC, Thomson JR, Machado RD, Morgan NV, Atkinson C, Winship I, et al. Clinical and molecular genetic features of pulmonary hypertension in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. N Engl J Med . 2001;345:325–334. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200108023450503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chaouat A, Coulet F, Favre C, Simonneau G, Weitzenblum E, Soubrier F, et al. Endoglin germline mutation in a patient with hereditary haemorrhagic telangiectasia and dexfenfluramine associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Thorax . 2004;59:446–448. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.11890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yao C, Chen G, Song C, Keefe J, Mendelson M, Huan T, et al. Genome-wide mapping of plasma protein QTLs identifies putatively causal genes and pathways for cardiovascular disease. Nat Commun . 2018;9:3268. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05512-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mosley JD, Benson MD, Smith JG, Melander O, Ngo D, Shaffer CM, et al. Probing the virtual proteome to identify novel disease biomarkers. Circulation . 2018;138:2469–2481. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dutzmann J, Daniel JM, Bauersachs J, Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Sedding DG. Emerging translational approaches to target STAT3 signalling and its impact on vascular disease. Cardiovasc Res . 2015;106:365–374. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Paulin R, Meloche J, Bonnet S. STAT3 signaling in pulmonary arterial hypertension. JAK-STAT . 2012;1:223–233. doi: 10.4161/jkst.22366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]