Background:

This meta-analysis aimed to identify the accuracy of shear wave elastography (SWE) in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer (EC).

Methods:

We searched the PubMed, Cochrane Library, and chinese biomedical literature database from inception to September 30, 2022. Meta-analysis was conducted using STATA version 14.0 and Meta-Disc version 1.4 software. We calculated summary statistics for sensitivity (Sen), specificity (Spe), positive and negative likelihood ratio (LR+/LR−), diagnostic odds ratio (DOR), and receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curves.

Results:

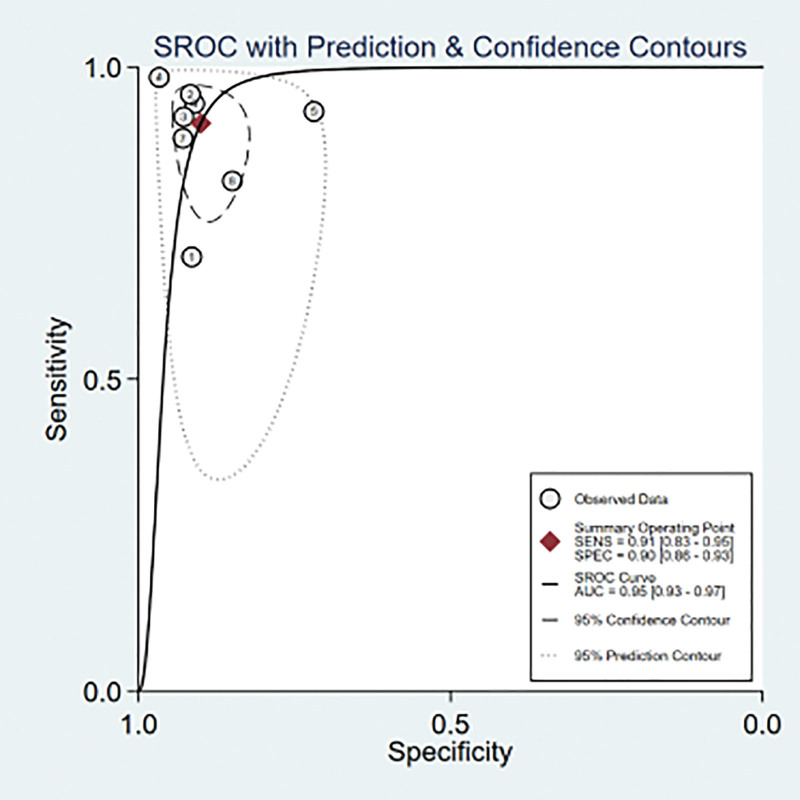

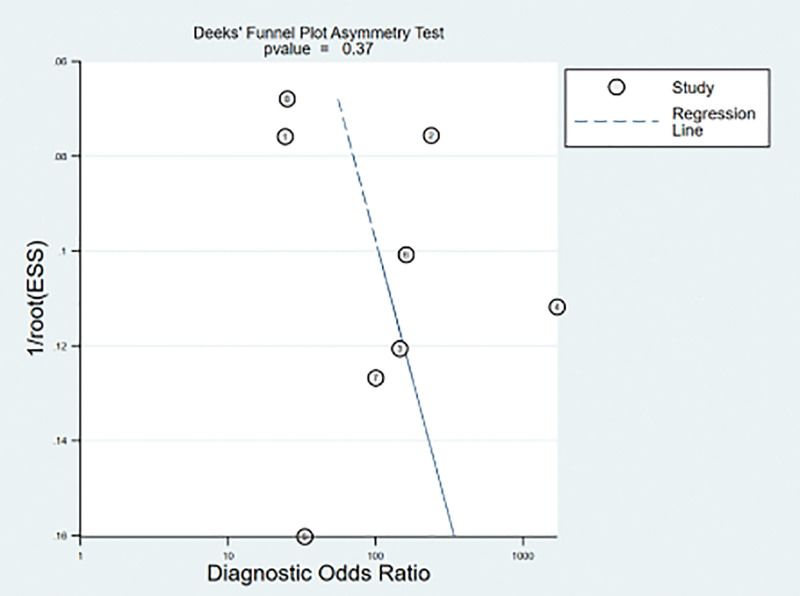

Eight studies that met all the inclusion criteria were included in this meta-analysis. A total of 432 patients with EC and 548 with benign endometrial lesions were assessed. All endometrial lesions were histologically confirmed by SWE. The pooled Sen was 0.91 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.83–0.95); the pooled Spe was 0.90 (95% CI = 0.86–0.93); the pooled LR+ was 9.10 (95% CI = 6.20–13.35); the pooled negative LR− was 0.10 (95% CI = 0.05–0.20); the pooled DOR of SWE in the diagnosis of EC was 90.73 (95% CI = 36.62–804.5). The area under the SROC curve was 0.95 (95% CI = 0.93–0.97). No evidence of publication bias was found (t = 0.98, P = .37).

Conclusion:

Our meta-analysis indicates that SWE may have high diagnostic accuracy in the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant endometrial lesions. Thus, SWE may be a useful tool for the diagnosis of EC.

Keywords: elastography, endometrial cancer, meta-analysis, ultrasound

1. Introduction

Among women, endometrial cancer (EC) was the 6th leading cause of cancer-related deaths in 2020.[1] It is a malignancy that originates in the endometrial gland. With the increase in the average life expectancy of the population and the change in living habits, the incidence of EC has been on the rise in the past decade, seriously threatening the life and health of women.[2] EC has occupied the first place in the incidence of malignancies of female reproductive system in developed countries.

Early diagnosis and timely treatment of EC can significantly improve patient prognosis, which has important clinical significance. At present, the main diagnostic method for clinical EC is vaginal color Doppler ultrasound, which has high diagnostic accuracy but still has limitations.[3] Sonographic elastography is conceptually based on tissue elasticity.[4] Sonographic elastography is used for tissue characterization via the application of compressions owing to elasticity degrees, quantitative measurement of elasticity, and stiffness of compressible tissues in different areas.[5,6] There are different types of elastography, including strain elastography, acoustic radiation force impulse elastography, shear-wave elastography (SWE), and transient elastography (TE).[7–10] In recent years, the development of SWE technology has been very rapid, has been widely studied by clinicians, and has become a hot topic in clinical research. It has achieved good clinical experience and effectiveness in the diagnosis of benign and malignant diseases of the breast, thyroid, liver, kidney, and other organs.[11–14]

Studies have shown that the hardness of endometrial lesions is closely related to their biological characteristics, and elastography technology can be used to directly analyze the hardness of the tissue, providing a new idea in the differential diagnosis of benign or malignant endometrial lesions. However, the sample sizes of these studies were small, and the results have been contradictory. Therefore, the present meta-analysis aimed to assess the diagnostic accuracy of shear wave elastography (SWE) for EC.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature search

We searched the PubMed, Cochrane Library, and chinese biomedical literature database from their inception to September 30, 2022. The following keywords and MeSH terms were used: [“Endometrial Neoplasm” or “Endometrial Carcinoma” or “Endometrial Cancer” or “Endometrium” or “endometrial lesion”] and [“elastography”]. We also performed a manual search to identify potentially suitable articles.

2.2. Selection criteria

The following 4 criteria were required for each study: the study design must be a clinical cohort study or diagnostic test; the study must relate to the accuracy of SWE for the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant endometrial lesions; all endometrial lesions must have been histologically confirmed after SWE; and published data in the 4-fold (2 × 2) tables must be sufficient. If the study did not meet all the inclusion criteria, it was excluded. When the authors published more than 1 study using the same subjects, only the most recent publication or publication with the largest sample size was included.

2.3. Data extraction

Relevant data were systematically extracted from all included studies by 2 researchers using a standardized form. The researchers collected the following data: first author’s surname, year of publication, language of publication, study design, sample size, number of lesions, source of the subjects, gold standard, and diagnostic accuracy. True positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives in the 4-fold (2 × 2) tables were also collected.

2.4. Quality assessment

Methodological quality was independently assessed by 2 researchers using the Quality Assessment of Studies of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS) tool.[15] The QUADAS criteria include 14 assessment items. Each item was scored as “yes” (2), “no” (0), or “unclear” (1). The QUADAS score ranged from 0 to 28, and a score ≥ 22 indicated good quality.

2.5. Statistical analysis

STATA version 14.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX) and Meta-Disc version 1.4 (Universidad Complutense, Madrid, Spain) software packages were used for the meta-analysis. We calculated the pooled summary statistics for sensitivity (Sen), specificity (Spe), positive and negative likelihood ratio (LR+/LR−), and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) curve and corresponding area under the curve were obtained. The threshold effect was assessed using Spearman’s correlation coefficients. Cochran’s Q-statistic and I test were used to evaluate potential heterogeneity between studies. If significant heterogeneity was detected (Q test P < .05, or I test > 50 %), a random effects model or fixed effects model was used. We also performed subgroup and meta-regression analyses to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity. A Sen analysis was performed to evaluate the influence of single studies on the overall estimate. We constructed Begger’s funnel plots and Egger’s linear regression tests to assess publication bias.

2.6. Ethical statement

As a systematic review summarizing the results of previous studies, this study did not require informed consent from patients or the approval of the ethics review committee.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of included studies

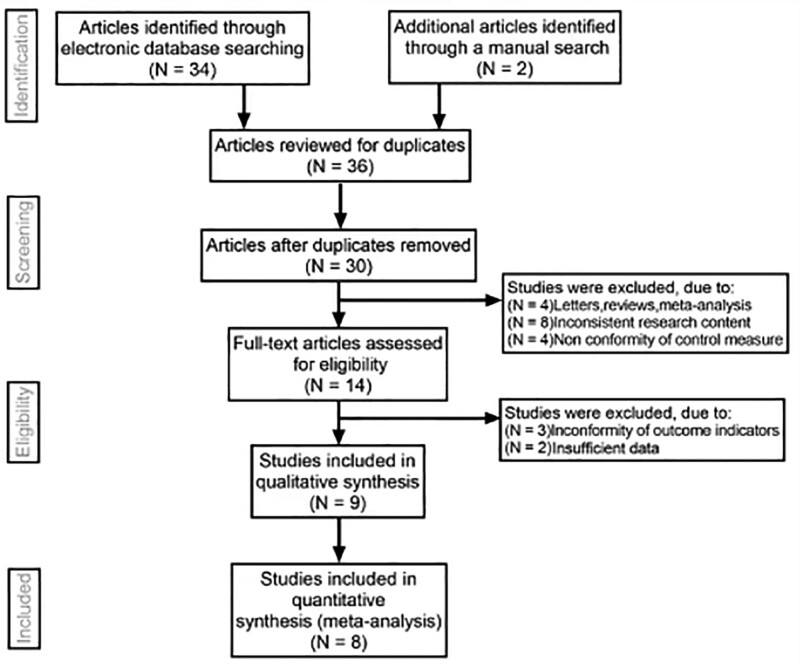

Initially, 36 articles were identified as keywords. We reviewed the titles and abstracts of all articles and excluded 23 articles; full texts and data integrity were also reviewed, and 5 more were excluded. Finally, 8 studies that met all inclusion criteria were included in this meta-analysis.[16–23] Figure 1 illustrates the selection process. A total of 432 patients with EC and 548 with benign endometrial lesions were assessed. The study characteristics and methodological qualities are summarized in Table 1. The QUADAS scores of all included studies were 22.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of literature search and study selection. Eight studies were included in this meta-analysis.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and methodological quality of all included studies.

| First author | Yr | Country | Language | Sample size | Age (Yrs) | Instrument | 2 × 2 table | QUADAS score | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP | FP | FN | TN | ||||||||

| Du YY[16] | 2019 | China | Chinese | 186 | 46.20 ± 8.78 | AixPlorer | 48 | 10 | 21 | 107 | 23 |

| Zhou WL[17] | 2020 | China | Chinese | 175 | 47.79 ± 8.93 | Hitachi Hi Vision900 | 87 | 7 | 4 | 77 | 22 |

| Zhang LY[18] | 2021 | China | Chinese | 80 | 35.31 ± 3.35 | GE LOGIQ E8 | 23 | 4 | 2 | 51 | 22 |

| He DX[19] | 2016 | China | Chinese | 90 | 45.4 ± 4.2 | PHILIPS HDI4000 | 59 | 1 | 1 | 29 | 23 |

| Metin MR[20] | 2015 | Turkey | English | 46 | 57.07 ± 12.16 | GE Logiq E9 | 13 | 9 | 1 | 23 | 24 |

| Ma H[21] | 2021 | China | English | 123 | 55.67 ± 7.40 | AixPlorer | 32 | 8 | 2 | 81 | 25 |

| Chen Z[22] | 2014 | China | Chinese | 63 | 38 ± 2.9 | Hitachi Hi Vision900 | 31 | 2 | 4 | 26 | 24 |

| Che DH[23] | 2019 | China | English | 217 | 46.6 ± 5.9 | GE Voluson E8 | 85 | 17 | 19 | 96 | 23 |

FN = false negative, FP = false positive, QUADAS = the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy studies, TN = true negative, TP = true positive.

3.2. Quantitative data synthesis

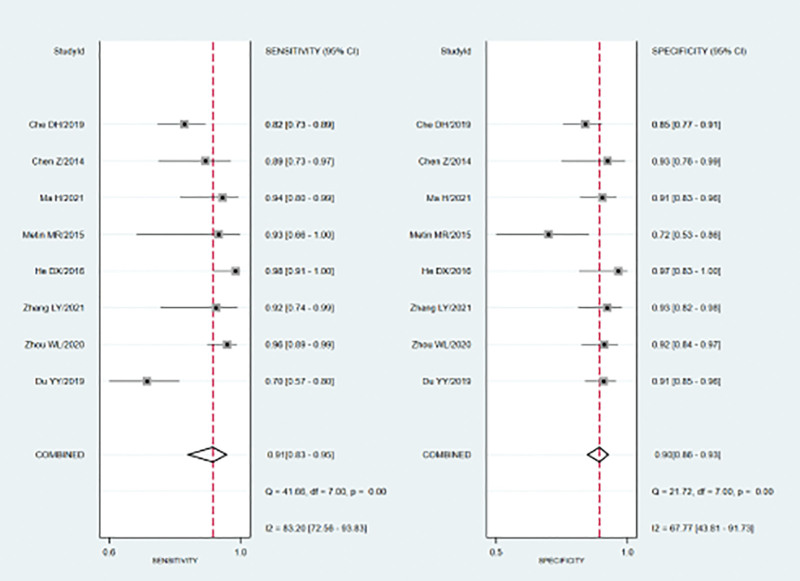

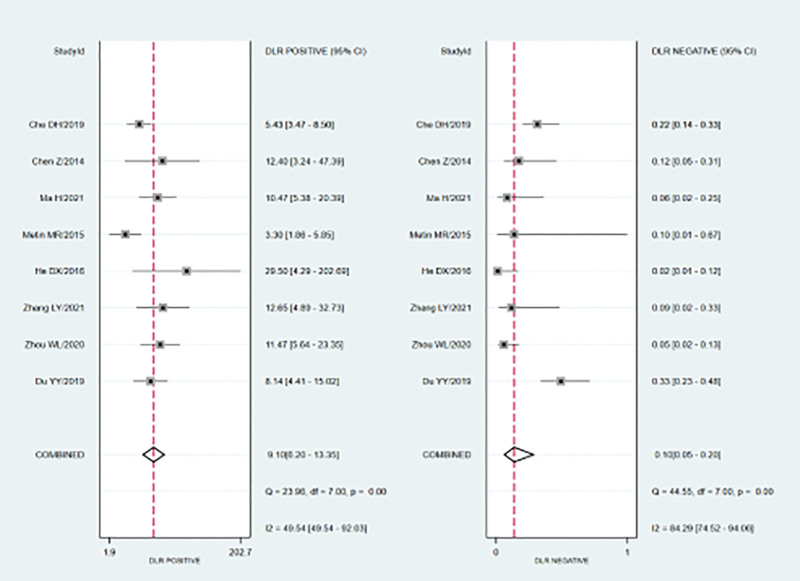

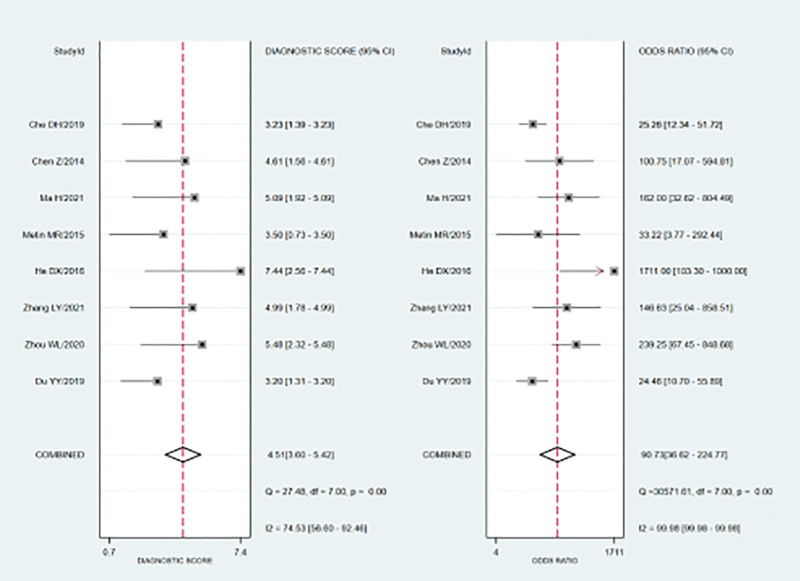

Meta-analysis findings on the accuracy of SWE for the differential diagnosis between benign and malignant endometrial lesions are shown in Table 2. The random-effects model was used because of the obvious heterogeneity among the studies. The diagnostic accuracy of SWE was measured as the pooled Sen, Spe, LR+, LR−, and DOR. Our meta-analysis reveals that the pooled Sen was 0.91 (95% CI = 0.83–0.95); the pooled Spe was 0.90 (95% CI = 0.86–0.93) (Fig. 2). There was no significant correlation (R = 0.310, P = .456) between the Sen and Spe, indicating that there was no threshold effect. In addition, we observed that the pooled LR+ and LR− were 9.10 (95% CI = 6.20–13.35) and 0.10 (95% CI = 0.05–0.20) (Fig. 3), respectively. The pooled DOR of SWE for the diagnosis of endometrial lesions was 90.73 (95% CI = 36.62–804.5) (Fig. 4). The results were plotted as a symmetrical SROC curve, and the corresponding area under the curve was 0.95 (95% CI = 0.93–0.97) (Fig. 5). Subgroup and meta-regression analyses were conducted based on language, instrument type, and sample size to investigate the potential sources of heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses revealed that SWE exhibited high diagnostic performance in different subgroups (Table 2). Meta-regression analysis confirmed that no factor could explain the potential sources of heterogeneity (Table 3). We found no evidence of obvious asymmetry in Begger’s funnel plots (Fig. 6). Egger’s test also did not indicate strong statistical evidence of publication bias (t = 0.98, P = .37).

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of the accuracy of SWE for the diagnosis of endometrial cancer.

| Subgroup | Studies (n) | Sen (95%CI) | Spe (95%CI) | LR+ (95%CI) | LR− (95%CI) | DOR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 8 | 0.91[0.83–0.95] | 0.90[0.86–0.93] | 9.10[6.20–13.35] | 0.10[0.05–0.20] | 90.73[36.62–804.5] |

| Language | ||||||

| Chinese | 5 | 0.89[0.84–0.92] | 0.92[0.89–0.95] | 10.62[7.19–15.69] | 0.09[0.03–0.29] | 130.94[34.38–498.74] |

| English | 3 | 0.86[0.79–0.91] | 0.86[0.80–0.90] | 5.60[3.09–10.17] | 0.14[0.06–0.34] | 46.08[13.84–153.46] |

| Sample size | ||||||

| Large | 4 | 0.85[0.80–0.89] | 0.90[0.86–0.92] | 7.96[5.54–11.42] | 0.14[0.06–0.32] | 60.47[20.24–180.62] |

| Small | 4 | 0.94[0.89–0.97] | 0.89[0.83–0.94] | 9.75[2.82–33.74] | 0.08[0.04–0.18] | 138.55[37.15–516.73] |

| Instrument | ||||||

| AixPlorer | 2 | 0.78[0.68–0.85] | 0.91[0.87–0.95] | 9.14[5.82–14.34] | 0.17[0.03–1.02] | 55.33[8.78–348.80] |

| Hitachi Hi Vision900 | 2 | 0.94[0.88–0.97] | 0.92[0.85–0.96] | 11.67[6.23–21.87] | 0.08[0.03–0.20] | 178.75[63.76–501.14] |

| GE | 3 | 0.86[0.83–0.93] | 0.86[0.80–0.90] | 5.74[2.91–11.33] | 0.11[0.03–0.36] | 59.02[11.94–291.67] |

| PHILIPS HDI4000 | 1 | 0.98[0.91–1.00] | 0.97[0.83–1.00] | 29.50[4.29–202.67] | 0.02[0.01–0.12] | 1711[103.3–1000] |

95% CI = 95% confidence interval, DOR = diagnostic odds ratio, LR = likelihood ratio, Sen = sensitivity, Spe = specificity, SWE = shear wave elastography.

Figure 2.

Forest plots for the sensitivity and specificity of SWE for the diagnosis of endometrial tumors. SWE = shear wave elastography.

Figure 3.

Forest plots for positive likelihood ratio and negative likelihood ratio of SWE for the diagnosis of endometrial tumors. SWE = shear wave elastography.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of DOR of SWE for the diagnosis of endometrial tumors. DOR = diagnostic odds ratio. SWE = shear wave elastography.

Figure 5.

SROC curve for the accuracy of SWE in the diagnosis of endometrial tumors. AUC = area under the curve, SROC = summary receiver operator characteristic, SWE = shear wave elastography.

Table 3.

Meta-regression analyses of potential source of heterogeneity.

| Heterogeneity factors | Coefficient | SE | P value | RDOR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UL | LL | |||||

| Publication yr | 0.207 | 0.2242 | 0.4525 | 1.23 | 0.47 | 3.23 |

| Language | 1.289 | 0.6513 | 0.1865 | 3.63 | 0.22 | 59.80 |

| Instrument | −0.035 | 0.3466 | 0.9291 | 0.97 | 0.22 | 4.29 |

| Sample size | −0.360 | 0.8350 | 0.7080 | 0.70 | 0.02 | 25.34 |

95% CI = 95 % confidence interval, LL = lower limit, RDOR = relative diagnostic odds ratio, SE = standard error, UL = upper limit.

Figure 6.

Begger’s funnel plot of publication bias on the pooled QR. No publication bias was detected in this meta-analysis. QR = qdds ratio.

4. Discussion

Uterine corpus cancer is the sixth most common type of cancer in the female population and the 15th most commonly cancer overall. Most uterine cancers are referred to as EC, which originates from the epithelial lining of the uterine cavity.[24] Early diagnosis and treatment can effectively improve patient prognosis, which has important clinical significance. Transvaginal color Doppler ultrasonography is a simple operation with intuitive, noninvasive, and other advantages, and has become a common method for the clinical diagnosis of EC. Previous studies have usually used transvaginal ultrasound to measure endometrial thickness to screen for EC in patients with abnormal uterine bleeding.[25,26] Despite the high Sen involved in diagnosing EC, transvaginal ultrasound also has a well-defined false negative rate. Measurement of endometrial thickness alone does not detect all ECs.

With the development of ultrasound technology, improving the accuracy of the early diagnosis of EC has become a research hotspot. Studies have shown that the hardness of endometrial lesions is closely related to their biological characteristics, and elastography can directly analyze the hardness of tissues, which provides a new idea for the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant endometrial lesions. SWE is a new elastography technique that can directly reflect the hardness of a tissue by calculating the absolute value of Young’s modulus to quantitatively analyze hardness.[27,28] In clinical practice, such as assessment of fibrosis in chronic liver diseases, thyroid and breast nodule detection, differentiation of pancreatic cystic tumors, classification of benign and malignant lymph nodes, and assessment of muscle stiffness, SWE has shown great potential.[29,30]

Recent studies have revealed that SWE is more accurate than conventional transvaginal ultrasound in detecting and describing endometrial lesions.[21–23] However, each diagnostic imaging examination has its advantages and disadvantages, and no imaging examination is sufficient to accurately diagnose the disease. Therefore, SWE should not replace conventional transvaginal ultrasound but should complement it. Although shear-wave elastography is considered a potentially useful imaging tool, it has not been widely used in clinical practice, and there have been few reports discussing its use in the assessment of endometrial lesions. This controversy may be caused by several factors, including differences in the study design, sample size, number of lesions, diagnostic criteria, and statistical methods. This study aimed to provide a comprehensive and reliable conclusion regarding the accuracy of transvaginal shear-wave elastography in the diagnosis of EC.

In the present meta-analysis, we systematically evaluated the technical performance and accuracy of SWE for the diagnosis of EC. Eight independent studies were included, and a total of 432 patients with EC and 548 patients with benign endometrial lesions were assessed. The pooled Sen, Spe, and DOR of SWE for the diagnosis of EC were 0.91, 0.90, and 90.73, respectively. These results were consistent with the potentially high diagnostic accuracy of SWE for EC, suggesting that SWE may be a good tool for the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant endometrial tumors and could predict the prognosis of patients with EC. The threshold effect is usually interpreted as a sudden and radical change in a phenomenon that often occurs after surpassing the quantitative limit. Our findings showed no significant relationship between Sen and Spe within these studies, providing no evidence of a threshold effect. As heterogeneity existed in the individual studies, subgroup analyses were conducted. Similar results were observed in subgroup analyses. SWE exhibited a high diagnostic performance in different subgroups for the diagnosis of EC, suggesting that differences in language, sample size, and instrument type did not directly influence the diagnostic accuracy of SWE. Furthermore, our results show no direct evidence of publication bias. Collectively, our findings strongly suggest that SWE is a highly accurate and noninvasive tool for the qualitative diagnosis of EC, consistent with previous studies. Despite the demonstrated diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal shear-wave elastography in the diagnosis of EC, our study had certain limitations. First, owing to the relatively small sample sizes and low quality of the included studies, there was insufficient data to assess the accuracy of transvaginal shear-wave elastography. Moreover, the retrospective nature of a meta-analysis can lead to subject selection bias; importantly, the majority of the included studies originated from China, which may adversely affect the reliability and validity of our results.

In conclusion, our meta-analysis suggests that SWE may have high diagnostic accuracy for the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant endometrial diseases. Thus, SWE may be a useful tool for the diagnosis of EC. However, owing to these limitations, further detailed studies are required to confirm the present findings.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the helpful comments on this paper received by our reviewers. We would also like to thank all our colleagues working in the Ultrasound Department of the First Affiliated Hospital to Dalian Medical University.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Yangcheng Liu.

Data curation: Jinyi Bian.

Formal analysis: Jinyi Bian.

Funding acquisition: Yangcheng Liu.

Investigation: Jinyi Bian, Jingnan Li.

Methodology: Yangcheng Liu.

Project administration: Yangcheng Liu.

Resources: Jinyi Bian, Jingnan Li.

Software: Jinyi Bian, Jingnan Li.

Supervision: Jinyi Bian.

Validation: Jinyi Bian.

Visualization: Yangcheng Liu.

Writing – original draft: Jinyi Bian.

Writing – review & editing: Jinyi Bian, Jingnan Li.

Abbreviations:

- CI

- confidence interval

- DOR

- diagnostic odds ratio

- EC

- endometrial cancer

- LR−

- negative likelihood ratio

- LR+

- positive likelihood ratio

- QUADAS

- the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy studies

- Sen

- sensitivity

- Spe

- specificity

- SROC

- summary receiver operating characteristic

- SWE

- shear wave elastography

- TE

- transient elastography

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are publicly available.

This study is supported by Liaoning Natural Science Foundation Project (20170540256) and Liaoning Natural Science Foundation Project (20180550612).

How to cite this article: Bian J, Li J, Liu Y. Diagnostic accuracy of shear wave elastography for endometrial cancer: A meta-analysis. Medicine 2023;102:4(e32700).

Contributor Information

Jinyi Bian, Email: 19863610740@189.cn.

Jingnan Li, Email: 1021176362@qq.com.

References

- [1].Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Doll KM, Winn AN. Assessing endometrial cancer risk among US women: long-term trends using hysterectomy-adjusted analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:318.e1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bouzid A, Ayachi A, Mourali M. Value of ultrasonography to predict the endometrial cancer in postmenopausal bleeding. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2015;43:652–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ophir J, Garra B, Kallel F, et al. Elastographic imaging. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2000;26(Suppl. 1):S23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Garra BS. Imaging and estimation of tissue elasticity by ultrasound. Ultrasound Q. 2007;23:255–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ciledag N, Arda K, Aribas BK, et al. The utility of ultrasound elastography and MicroPure imaging in the differentiation of benign and malignant thyroid nodules. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:W244–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Onur MR, Göya C. Ultrasound elastography: abdominal applications. Turkiye Klinikleri J Radiol Special Topics. 2013;6:59–69. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Cosgrove D, Piscaglia F, Bamber J, et al. EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations on the clinical use of ultrasound elastography. Part 2: clinical applications. Ultraschall Med. 2013;34:238–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Fahey BJ, Nelson RC, Bradway DP, et al. In vivo visualization of abdominal malignancies with acoustic radiation force elastography. Phys Med Biol. 2008;53:279–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Yu H, Wilson SR. Differentiation of benign from malignant liver masses with acoustic radiation force impulse technique. Ultrasound Q. 2011;27:217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Menzilcioglu MS, Duymus M, Citil S, et al. Strain wave elastography for evaluation of renal parenchyma in chronic kidney disease. Br J Radiol. 2015;88:20140714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Shuzhen C. Comparison analysis between conventional ultrasonography and ultrasound elastography of thyroid nodules. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:1806–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gerber L, Fitting D, Srikantharajah K, et al. Evaluation of 2D-shear wave elastography for characterisation of focal liver lesions. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2017;26:283–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Klotz T, Boussion V, Kwiatkowski F, et al. Shear wave elastography contribution in ultrasound diagnosis management of breast lesions. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2014;95:813–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Whiting PF, Weswood ME, Rutjes AW, et al. Evaluation of quadas, a tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Yuanyuan D. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of endometrial lesions by transvaginal real-time shear wave elastography [D] [master's thesis]. Hebei Medical University. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [17].Weili Z. Application value of ultrasound elastography combined with transvaginal color Doppler ultrasound in early diagnosis of endometrial cancer. Henan Med Res. 2020;29:6486–8. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Liuying Z. The efficacy of transvaginal color Doppler ultrasound combined with real-time shear wave elastography in the diagnosis of endometrial cancer. China Minkang Med. 2021;33:106–7. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Daxin H, Haicheng Z, Ying M. Value of transvaginal color Doppler ultrasound combined with elastography in early diagnosis of endometrial cancer. Chinese J Med Phys. 2016;33:1163–7. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Metin MR, Aydin H, Ünal O, et al. Differentiation between endometrial carcinoma and atypical endometrial hyperplasia with transvaginal sonographic elastography. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2016;97:425–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ma H, Yang Z, Wang Y, et al. The value of shear wave elastography in predicting the risk of endometrial cancer and atypical endometrial hyperplasia. J Ultrasound Med. 2021;9999:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhuo C. Study on the predictive value of transvaginal ultrasound combined with elastography in the diagnosis of uterine space occupying lesions [D] [master's thesis]. Zhengzhou University. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Che D, Wei H, Yang Z, et al. Application of transvaginal sonographic elastography to distinguish endometrial cancer from benign masses. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11:1049–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Costa BP, Nassr MT, Diz FM, et al. Fructose-1,6-bisphosphate induces generation of reactive oxygen species and activation of p53-dependent cell death in human endometrial cancer cells. J Appl Toxicol. 2021;41:1050–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Schramm A, Ebner F, Bauer E, et al. Value of endometrial thickness assessed by transvaginal ultrasound for the pre-diction of endometrial cancer in patients with postmenopausal bleeding. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;296:319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Visser NC, Sparidaens EM, van den Brink JW, et al. Long-term risk of endometrial cancer following post-menopausal bleeding and reassuring endometrial biopsy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2016;95:1418–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Therville N, Arcucci S, Vertut A, et al. Experimental pancreatic cancer develops in soft pancreas: novel leads for an individualized diagnosis by ultrafast elasticity imaging. Theranostics. 2019;9:6369–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Dirrichs T, Meiser N, Panek A, et al. Transcranial shear wave Elastography of neonatal and infant brains for quantitative evaluation of increased intracranial pressure. Invest Radiol. 2019;54:719–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Săftoiu A, Gilja OH, Sidhu PS, et al. The EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations for the clinical practice of elastography in non-hepatic applications: update 2018. Ultraschall Med. 2019;40:425–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Dietrich CF, Bamber J, Berzigotti A, et al. EFSUMB guidelines and recommendations on the clinical use of liver ultrasound elastography, update 2017 (long version). Ultraschall Med. 2017;38:e16–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]