Abstract

Background

COVID-19 vaccination was expected to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission, but the relevance of this effect remains unclear. We aimed to estimate the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination of the index cases and their close contacts in reducing the probability of SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Methods

Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection was evaluated in two cohorts of adult close contacts of COVID-19 confirmed cases (social and household settings) by COVID-19 vaccination status of the index case and the close contact, from April to November 2021 in Navarre, Spain. The effects of vaccination of the index case and the close contact were estimated as (1–adjusted relative risk) × 100%.

Results

Among 19,631 social contacts, 3257 (17%) were confirmed with SARS-CoV-2. COVID-19 vaccination of the index case reduced infectiousness by 44% (95% CI, 27–57%), vaccination of the close contact reduced susceptibility by 69% (95% CI, 65–73%), and vaccination of both reduced transmissibility by 74% (95% CI, 70–78%) in social settings, suggesting some synergy of effects. Among 20,708 household contacts, 6269 (30%) were infected, and vaccine effectiveness estimates were 13% (95% CI, −5% to 28%), 61% (95% CI, 58–64%), and 52% (95% CI, 47–56%), respectively. These estimates were lower in older people and had not relevant differences between the Alpha (April-June) and Delta (July-November) variant periods.

Conclusions

COVID-19 vaccination reduces infectiousness and susceptibility; however, these effects are insufficient for complete control of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, especially in older people and household setting. Relaxation of preventive behaviors after vaccination may counteract part of the vaccine effect on transmission.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19 vaccine, Cohort study, Vaccine effectiveness, Close contact, Transmission

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 can be transmitted from an infected person to their close contacts by droplets and air [1], [2], [3]. Since SARS-CoV-2 emerged in December 2019, control measures such as the use of facemasks, physical distancing, contact tracing, and isolation of cases helped to slow the spread [4], [5]. However, maintaining compliance with these measures over time is difficult, and their effects disappear as soon as the measures are suspended.

COVID-19 vaccination has been suggested as a preventive measure with long lasting effects [5]. Several studies found very high effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination in preventing hospital admission and COVID-19 deaths, but effectiveness in preventing mild and asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection was notably lower and declined progressively [6], [7]. Therefore, vaccinated individuals may acquire and transmit the SARS-CoV-2 infection [8], [9]. The effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination in preventing SARS-CoV-2 transmission is crucial information for planning a prudent de-escalation of preventive measures in the environment of highly vulnerable people, following the increase in vaccination coverage [5], [10].

COVID-19 vaccination is expected to reduce SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the population by several mechanisms [11]. COVID-19 vaccines have demonstrated a considerable direct effect in preventing infection among vaccinated people (susceptibility) [7]. Vaccination may also reduce the infectiousness of breakthrough infections [10]. This reduced infectiousness may be related to decreased severity, symptom intensity, infectivity duration, and viral load [12]. Additionally, the indirect effect of the COVID-19 vaccines may reduce SARS-CoV-2 circulation in populations with high vaccination coverage [13].

SARS-CoV-2 transmission may happen in household and other settings, such as social meetings, workplaces, and schools [14], [15]. Close household contacts have been found to have a higher risk of infection than close contacts in other settings, since exposure is usually more intense and repeated in the household [16], [17], [18], [19], [20].

This study aimed to estimate the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination in reducing the infectiousness of index cases, the susceptibility of their close contacts, and the probability of SARS-CoV-2 transmission when both of them are vaccinated.

Material and methods

Study population and design

This study analyzed two prospective dynamic cohorts of adults (≥18 years old) based on the contact tracing of laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases in Navarre, Spain, where the Health Service provides universal health care, free at the point of service. A first cohort included social contacts and a second cohort included household contacts. These cohorts incorporated all adults covered by the Navarre Health Service, who had been close contacts of adult index cases with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection from April to November 2021. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee for Clinical Research of Navarre (PI2020/45), which waived the requirement of obtaining signed consent since the study analyzed an anonymous database.

As a measure of infection control, all laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases were interviewed to identify their close contacts [21]. The index case was the first person who presented SARS-CoV-2 infection in each specific setting and was confirmed by reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) or antigen test. Only one index case per cluster was considered. Close contact of a COVID-19 index case was defined as any person who had face-to-face contact with a confirmed COVID-19 infected individual within 2 m for more than a total of 15 min without personal protection within a timeframe ranging from 2 days before to 10 days after the onset of symptoms of the case, or in the 2 days before to 10 days after the sample which led to confirmation was taken from asymptomatic cases [20], [22]. The same protocol was applied regardless of the contact setting. Close contacts were initially tested by RT-qPCR for SARS-CoV-2 in nasopharynx samples and 10 days after the last contact. A positive antigen test within 5 days from the symptom onset was also considered confirmatory of SARS-CoV-2 infection in symptomatic individuals, because this test had demonstrated very high specificity in these cases. Close contacts with negative antigen tests were retested with RT-qPCR. Contact tracing was registered including information on the index case, the close contact, and the risk exposure; and this information was electronically connected with the databases of laboratory-test results, medical records, and enhanced epidemiological surveillance of COVID-19. Close contacts non-covered by the Navarre Health Service, with a previous positive test for SARS-CoV-2, younger than 18 years, nursing home residents, and those who did not complete the testing protocol or who had been confirmed less than 3 days after the index case diagnosis date were excluded from the present study. This last exclusion pretended to reduce doubts about the directionality of transmission. Each close contact was only included once in the study. During the study period, there was high availability of diagnostic tests and personnel for testing and contact tracing of all confirmed cases.

The close contact variables were age group (18–34, 35–49, 50–59, 60–69, and ≥70 years), sex, major chronic conditions, the month of contact, and contact setting (social or household). Household close contacts were considered those who lived in the same house during the infectivity period of the index case, while the category of social setting included close contacts generated in any activity occurring outside the home, such as social life, workplace, educational settings, and others. The presence of symptoms in the index case was also considered.

The index cases samples with a cycle threshold ≤ 30 were tested by TaqPath™ COVID-19 RT-qPCR kit and TaqMan™ SARS-CoV-2 Mutation Panel (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions to get an approximation of the variant. S-gene target failure by TaqPath was used as a proxy for identifying the Alpha variant [23]. Among samples that tested positive for the S target, a second RT-qPCR (TaqMan) assay was used to detect possible cases of Delta variant (detection of the L452R mutation).

The COVID-19 vaccination campaign started on 27 December 2020 in Spain. Four vaccine products have been used: BNT162b2 mRNA (BioNTech-Pfizer, Mainz, Germany/New York, USA), mRNA-1273 (Moderna, Cambridge, US), ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 (Oxford-AstraZeneca, Cambridge, United Kingdom), and Ad26. COV2-S (Janssen-Cilag International NV, Beerse, Belgium). Vaccination was successively targeted from higher to lower age groups [24]. COVID-19 vaccine doses and date of administration of index cases and their close contacts were obtained from the regional vaccination register, and only registered doses were considered. Each dose was considered potentially effective 14 days after administration. Fully vaccinated people were considered 14 days after the first dose of Ad26. COV2-S or after the second dose of other vaccines.

Statistical analysis

Basic characteristics of both cohorts of close contacts were described. The secondary attack rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection in close contacts was compared by characteristics of the study population of close contacts and by COVID-19 vaccination status of the index case in both contact settings (social and household).

We used Cox regression models to evaluate the vaccine effectiveness in reducing infectiousness, susceptibility and transmissibility between index cases and their close contacts in social and household settings. The same risk period was assigned to everyone in the cohort; therefore, we estimated crude and adjusted relative risks (aRR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). Adjusted models included age group, sex, major chronic condition of close contacts, vaccination status of the index case and the close contact, and month of contact.

To estimate the vaccine effectiveness, we used the combination of the vaccination status (unvaccinated, partially vaccinated, and fully vaccinated) of the index case and the close contact in nine categories. Unvaccinated close contact of an unvaccinated index case was the reference category. Although models included nine categories, to simplify the presentation of results, we only show the estimates of categories with partial vaccination in supplementary material, as this was a transitory status that affected a few subjects. The estimate of the category of fully vaccinated close contacts of unvaccinated index cases was considered as a measure of susceptibility, that of unvaccinated close contacts of fully vaccinated index cases was considered as a measure of infectiousness, and that of fully vaccinated close contacts of fully vaccinated index cases was considered as an indicator of transmissibility. Two periods were considered according to the dominant SARS-CoV-2 variant in the region: from April to June 2021 more than 90% of characterized cases were due to the Alpha variant, and from July to November 2021, more than 90% were due to the Delta variant.

The synergy between the vaccination status of the index case and their close contacts were evaluated by comparing the category of vaccinated contact of an unvaccinated index case with the category of vaccinated close contact of a vaccinated index case. Stratified analyses were performed by age groups (18–59 and ≥60 years), the presence of symptoms of the index case, the variant dominance period, and the variant detected in the index case (Alpha, Delta, and others).

The vaccine effectiveness was estimated as a percentage: (1 − aRR) × 100. P-values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of the close contact cohorts

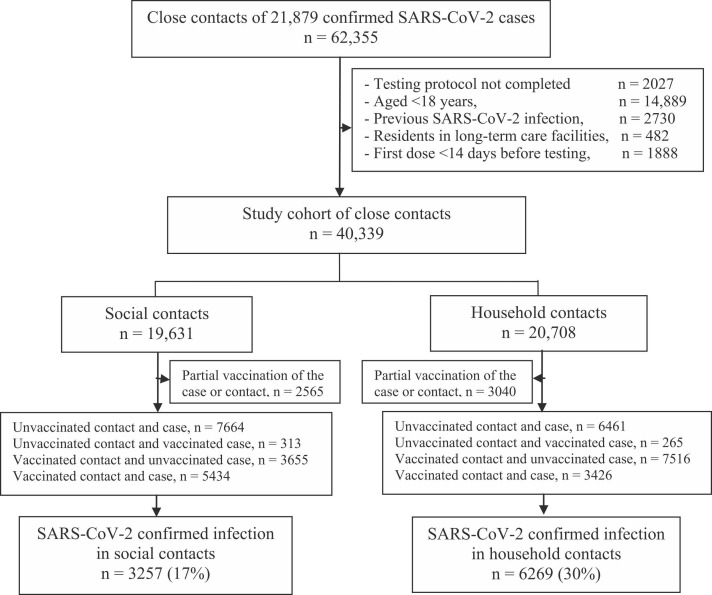

Among a total of 62,355 close contacts of 21,879 index case, 40,339 close contacts met the study inclusion criteria, 20,708 (51%) were close household contacts and 19,631 were close social contacts. As compared to the household contacts, social contacts less frequently were older than 50 years (38% versus 49%) and had received any COVID-19 vaccine (58% vs 67%); however, the close social contacts were more frequently contact of a vaccinated index case (36% vs 23%)( Fig. 1 and Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the cohort study of close contacts for evaluating vaccination effect on SARS-CoV-2 transmission in Navarre, Spain, April to November 2021. Contact means close contact; case means index case. n, number of close contacts under the specific condition.

Table 1.

SARS-CoV-2 infection in social and household close contacts by characteristics of the close contacts and vaccination status of the index case and the close contacts.

| Social contacts |

Household contacts |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables of the study population | Nº | % | Positive | SAR, % | Nº | % | Positive | SAR, % |

| Total | 19,631 | 100 | 3257 | 17 | 20,708 | 100 | 6269 | 30 |

| Age group, years | ||||||||

| 18–34 | 7312 | 37 | 1757 | 24 | 4081 | 20 | 1548 | 38 |

| 35–49 | 4894 | 25 | 619 | 13 | 6559 | 32 | 2184 | 33 |

| 50–59 | 2174 | 11 | 288 | 13 | 2297 | 11 | 708 | 31 |

| 60–69 | 2653 | 14 | 292 | 11 | 6206 | 30 | 1294 | 21 |

| ≥ 70 | 2598 | 13 | 301 | 12 | 1565 | 8 | 535 | 34 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 9508 | 48 | 1692 | 18 | 9754 | 47 | 2922 | 30 |

| Female | 10,123 | 52 | 1565 | 16 | 10,954 | 53 | 3347 | 31 |

| Major chronic condition | ||||||||

| No | 13,768 | 70 | 2350 | 17 | 14,963 | 72 | 4529 | 30 |

| Yes | 5863 | 30 | 907 | 16 | 5745 | 28 | 1740 | 30 |

| Diabetes | 960 | 5 | 140 | 15 | 961 | 5 | 331 | 34 |

| Cancer | 1257 | 6 | 157 | 13 | 1272 | 6 | 354 | 28 |

| Liver cirrhosis | 361 | 2 | 46 | 13 | 389 | 2 | 107 | 28 |

| Renal disease | 508 | 3 | 72 | 14 | 415 | 2 | 130 | 31 |

| Immunodeficiency | 146 | 1 | 17 | 12 | 143 | 1 | 55 | 39 |

| Asthma | 1535 | 8 | 273 | 18 | 1306 | 6 | 423 | 32 |

| COPD | 891 | 5 | 124 | 14 | 930 | 5 | 272 | 29 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 1546 | 8 | 235 | 15 | 1374 | 7 | 414 | 30 |

| Dementia | 85 | 0.4 | 13 | 15 | 72 | 0.3 | 16 | 22 |

| Stroke | 238 | 1 | 33 | 14 | 200 | 1 | 57 | 29 |

| Rheumatic disease | 162 | 1 | 23 | 14 | 198 | 1 | 56 | 28 |

| Severe obesity | 255 | 1 | 39 | 15 | 297 | 1 | 112 | 38 |

| Vaccination status of close contact | ||||||||

| Unvaccinated | 8244 | 42 | 2058 | 25 | 6933 | 33 | 3138 | 45 |

| Partially vaccinated | 1873 | 10 | 201 | 11 | 2397 | 12 | 541 | 23 |

| Fully vaccinated | 9514 | 48 | 998 | 11 | 11,378 | 55 | 2590 | 23 |

| Month of contact | ||||||||

| April | 3712 | 19 | 629 | 17 | 3469 | 17 | 1517 | 44 |

| May | 1513 | 8 | 182 | 12 | 1493 | 7 | 547 | 37 |

| June | 1146 | 6 | 162 | 14 | 957 | 5 | 300 | 31 |

| July | 5639 | 29 | 1347 | 24 | 7636 | 37 | 1523 | 20 |

| August | 2105 | 11 | 271 | 13 | 2805 | 14 | 771 | 28 |

| September | 660 | 3 | 66 | 10 | 565 | 3 | 196 | 35 |

| October | 1036 | 5 | 114 | 11 | 570 | 3 | 242 | 43 |

| November | 3820 | 19 | 486 | 13 | 3213 | 16 | 1173 | 37 |

| Close contact of symptomatic index case | ||||||||

| No | 2324 | 12 | 259 | 11 | 3457 | 17 | 681 | 20 |

| Yes | 17,307 | 88 | 2998 | 17 | 17,251 | 83 | 5588 | 32 |

| Close contact by vaccination status of the index case | ||||||||

| Unvaccinated | 12,631 | 64 | 2511 | 20 | 15,955 | 77 | 4777 | 30 |

| Partially vaccinated | 979 | 5 | 102 | 10 | 853 | 4 | 235 | 28 |

| Fully vaccinated | 6021 | 31 | 644 | 11 | 3900 | 19 | 1257 | 32 |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; SAR, secondary attack rate.

Among close social contacts, 3257 (17%) were confirmed with SARS-CoV-2, while among close household contacts the infection was detected in 6269 (30%). In both settings, the transmission was more frequent in close contacts younger than 35 years and unvaccinated, as well as when the index case was unvaccinated and presented symptoms (Table 1).

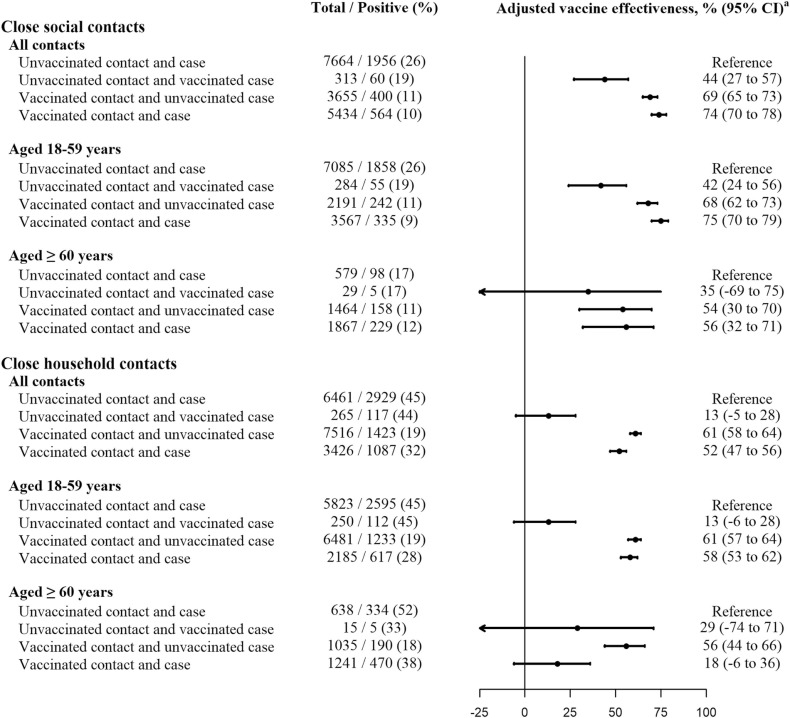

Vaccine effectiveness on SARS-CoV-2 transmission in social settings

The secondary attack rate from unvaccinated index cases to their unvaccinated close social contacts was 26% on average. Vaccination of the index case reduced infectiousness by 44% (95% CI 27–57%), vaccination of the close contact reduced susceptibility by 69% (95% CI 65–73%), and vaccination of both reduced transmissibility by 74% (95% CI 70–78%), suggesting an additional effect of vaccination of both compared to close contact vaccination alone (p = 0.015). These vaccine effectiveness estimates were similar in young adult contacts (42%, 95% CI 24–56%; 68%, 95% CI 62–73%; and 75%, 95% CI 70–79%; respectively), but suggested a lower reduction of susceptibility in contacts older than 60 years (35%, 95% CI −69% to 75%; 54%, 95% CI 30–70%; and 56%, 95% CI 32–71%; respectively) ( Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Effect of COVID-19 vaccination on the SARS-CoV-2 transmission among social and household close contacts, overall and by age of the close contact. Contact means close contact; case means index case. a Vaccine effectiveness adjusted by age groups (18–34, 35–49, 50–69 and ≥70 years), sex, major chronic condition of close contacts, and month of contact.

The presence of symptoms in the index case was associated with higher secondary attack rates, regardless of the vaccination status of the index case and the close contact; however, vaccination of the close contacts appeared to be more protective in contacts of asymptomatic index cases than in contacts of symptomatic index cases (80% vs 68%). For all vaccination statuses, the secondary attack rates in close social contacts increased from the Alpha variant period (April-June) to the Delta variant period (July-November); however, for the same vaccination status, the vaccine effectiveness estimates were similar or slightly higher during the Delta variant period, with 47% reduction of infectiousness, 72% of susceptibility and 76% of transmissibility. Results of the analyses by dominant variant periods were consistent with those considering the variants detected in the index cases ( Table 2 and Supplementary Tables S2 and S3).

Table 2.

Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination on the SARS-CoV-2 transmission among close social contacts.

| Total nº | Positive nº | % | Crude RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI)a | Adjusted VE, % (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contacts of symptomatic index case | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 6715 | 1793 | 27 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 256 | 52 | 20 | 0.76 (0.58–1.00) | 0.57 (0.43–0.76) | 43 (24 to 57) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 3119 | 367 | 12 | 0.44 (0.39–0.49) | 0.32 (0.28–0.38) | 68 (62 to 72) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 5011 | 535 | 11 | 0.40 (0.36–0.44) | 0.26 (0.23–0.31) | 74 (69 to 77) |

| Contacts of asymptomatic index case | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 949 | 163 | 17 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 57 | 8 | 14 | 0.82 (0.40–1.66) | 0.56 (0.27–1.15) | 44 (−15 to 73) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 536 | 33 | 6 | 0.36 (0.25–0.52) | 0.20 (0.12–0.34) | 80 (66 to 88) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 423 | 29 | 7 | 0.40 (0.27–0.59) | 0.18 (0.10–0.32) | 82 (68 to 90) |

| Contacts with major chronic condition | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 1745 | 441 | 25 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 61 | 10 | 16 | 0.65 (0.35–1.21) | 0.46 (0.24–0.88) | 54 (12 to 76) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 1376 | 142 | 10 | 0.41 (0.34–0.49) | 0.28 (0.21–0.37) | 72 (63 to 79) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 1876 | 223 | 12 | 0.47 (0.40–0.55) | 0.29 (0.22–0.38) | 71 (62 to 78) |

| Contacts without major chronic condition | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 5919 | 1515 | 26 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 252 | 50 | 20 | 0.78 (0.59–1.03) | 0.58 (0.43–0.78) | 42 (22 to 57) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 2279 | 258 | 11 | 0.44 (0.39–0.51) | 0.33 (0.28–0.39) | 67 (61 to 72) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 3558 | 341 | 10 | 0.37 (0.33–0.42) | 0.24 (0.20–0.30) | 76 (70 to 80) |

| April to June 2021 | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 4811 | 834 | 17 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 56 | 5 | 9 | 0.52 (0.21–1.24) | 0.56 (0.23–1.36) | 44 (–36 to 77) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 457 | 32 | 7 | 0.40 (0.28–0.58) | 0.41 (0.29–0.60) | 59 (40 to 71) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 30 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| July to November 2021 | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 2853 | 1122 | 39 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 257 | 55 | 21 | 0.54 (0.42–0.71) | 0.53 (0.40–0.71) | 47 (29 to 60) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 3198 | 368 | 12 | 0.29 (0.26–0.33) | 0.28 (0.24–0.33) | 72 (67 to 76) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 5404 | 564 | 10 | 0.27 (0.24–0.29) | 0.24 (0.21–0.29) | 76 (71 to 79) |

| Contacts of index cases infected with the Alpha variant | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 2030 | 328 | 16 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 23 | 5 | 22 | 1.35 (0.56–3.25) | 1.22 (0.50–2.98) | –22 (–198 to 50) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 246 | 19 | 8 | 0.48 (0.30–0.76) | 0.46 (0.28–0.77) | 54 (23 to 72) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 32 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Contacts of index cases infected with the Delta variant | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 585 | 293 | 50 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 101 | 28 | 28 | 0.55 (0.38–0.82) | 0.55 (0.36–0.84) | 45 (16 to 64) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 565 | 58 | 10 | 0.21 (0.16–0.27) | 0.20 (0.14–0.28) | 80 (72 to 86) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 1867 | 184 | 10 | 0.20 (0.16–0.24) | 0.17 (0.12–0.24) | 83 (76 to 88) |

| Contacts of index cases infected with variants other than Alpha and Delta | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 309 | 76 | 25 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 3 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | NA |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 80 | 8 | 10 | 0.41 (0.20–0.84) | 0.57 (0.23–1.42) | 43 (–42 to 77) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 22 | 4 | 18 | 0.74 (0.27–2.02) | 0.87 (0.22–3.44) | 13 (–244 to 78) |

RR: relative risk; VE: vaccine effectiveness; NA: not available; contact means close contact; case means index case.

Relative risk adjusted by age groups (18–34, 35–49, 50–69 and ≥70 years), sex, major chronic condition of close contacts, and month of contact.

Vaccine effectiveness on SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the household

The secondary attack rate from unvaccinated index cases to their unvaccinated close household contacts was 45% on average. COVID-19 vaccination of the index case did not show a significant reduction in the infectiousness (13%, 95% CI −5% to 28%). A moderate preventive effect of transmission (61%, 95% CI 58–64%) was observed in vaccinated close contacts of unvaccinated index cases, while paradoxically, vaccination of both provided a lower reduction of the transmissibility (52%, 95% CI 47–56%; p < 0.001). This vaccine effect in reducing transmission was lower in close contacts older than 60 years (18%, 95% CI −6% to 36%) compared to those aged 18–59 years (58%, 95% CI 53–62%), as well as in close contacts without major chronic conditions (56%, 95% CI 50–61%) compare to those with any of these conditions (40%, 95% CI 28–51%). The paradoxical lower reduction of transmissibility when both, the close contact and the index case, were vaccinated, compared with only vaccinated close contact was mainly observed in contacts older than 60 years (18% vs 56%, p < 0.001) (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Tables S4-S6).

The secondary attack rates were higher in close contacts of symptomatic index cases than in those contacts of asymptomatic index cases, and the effect of the close contact vaccination was higher when the index case was symptomatic (62% vs 49%). The secondary attack rates in close household contacts remained unchanged from the Alpha variant period (April-June) to the Delta variant period (July-November). As compared to vaccinated close contacts of unvaccinated index cases, the vaccination effectiveness in reducing transmission was lower when both were immunized, overall (52% vs 61%, p < 0.001), for symptomatic index cases (53% vs 62%, p < 0.001), and in the Delta variant period (51% vs 62%, p = 0.026) ( Table 3 and Supplementary Table S5).

Table 3.

Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccination on the SARS-CoV-2 transmission among close household contacts.

| Total nº | Positive nº | % | Crude RR (95% CI) | Adjusted RR (95% CI)a | Adjusted VE, % (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contacts of symptomatic index case | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 5372 | 2641 | 49 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 218 | 101 | 46 | 0.94 (0.77–1.15) | 0.84 (0.69–1.04) | 16 (−4 to 31) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 6026 | 1185 | 20 | 0.40 (0.37–0.43) | 0.38 (0.35–0.41) | 62 (59 to 65) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 3076 | 1024 | 33 | 0.68 (0.63–0.73) | 0.47 (0.42–0.52) | 53 (48 to 58) |

| Contacts of asymptomatic index case | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 1089 | 288 | 26 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 47 | 16 | 34 | 1.29 (0.78–2.13) | 1.11 (0.66–1.87) | –11 (–87 to 34) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 1490 | 238 | 16 | 0.60 (0.51–0.72) | 0.51 (0.40–0.66) | 49 (34 to 60) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 350 | 63 | 18 | 0.68 (0.52–0.89) | 0.48 (0.34–0.69) | 52 (31 to 66) |

| Contacts with major chronic condition | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 1537 | 689 | 45 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 64 | 25 | 39 | 0.87 (0.59–1.30) | 0.79 (0.52–1.19) | 21 (–19 to 48) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 2076 | 370 | 18 | 0.40 (0.35–0.45) | 0.40 (0.34–0.48) | 60 (52 to 66) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 1194 | 425 | 36 | 0.79 (0.70–0.90) | 0.60 (0.49–0.72) | 40 (28 to 51) |

| Contacts without major chronic condition | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 4929 | 2240 | 46 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 201 | 92 | 46 | 1.01 (0.82–1.24) | 0.90 (0.72–1.11) | 10 (–11 to 28) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 5430 | 1053 | 19 | 0.43 (0.40–0.46) | 0.39 (0.35–0.43) | 61 (57 to 65) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 2232 | 662 | 30 | 0.65 (0.60–0.71) | 0.44 (0.39–0.50) | 56 (50 to 61) |

| April to June 2021 | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 4483 | 1999 | 45 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 30 | 10 | 33 | 0.75 (0.40–1.39) | 0.76 (0.41–1.41) | 24 (–41 to 59) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 503 | 88 | 18 | 0.39 (0.32–0.49) | 0.38 (0.30–0.47) | 62 (53 to 70) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 32 | 6 | 19 | 0.42 (0.19–0.94) | 0.37 (0.16–0.82) | 63 (18 to 84) |

| July to November 2021 | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 1978 | 930 | 47 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 235 | 107 | 46 | 0.97 (0.79–1.18) | 0.87 (0.71–1.06) | 13 (–6 to 29) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 7013 | 1335 | 19 | 0.41 (0.37–0.44) | 0.38 (0.35–0.43) | 62 (57 to 65) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 3394 | 1071 | 32 | 0.68 (0.62–0.74) | 0.49 (0.44–0.55) | 51 (45 to 56) |

| Contacts of index cases infected with the Alpha variant | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 1760 | 739 | 42 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 16 | 10 | 63 | 1.49 (0.80–2.78) | 1.55 (0.83–2.91) | –55 (–191 to 17) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 337 | 39 | 12 | 0.28 (0.20–0.38) | 0.27 (0.19–0.38) | 73 (62 to 81) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 25 | 6 | 24 | 0.57 (0.26–1.28) | 0.55 (0.24–1.26) | 45 (−26 to 76) |

| Contacts of index cases infected with the Delta variant | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 352 | 182 | 52 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 73 | 32 | 44 | 0.85 (0.58–1.23) | 0.81 (0.55–1.18) | 19 (–18 to 45) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 1165 | 225 | 19 | 0.37 (0.31–0.45) | 0.37 (0.30–0.47) | 63 (53 to 70) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 1042 | 338 | 32 | 0.63 (0.52–0.75) | 0.46 (0.37–0.58) | 54 (42 to 63) |

| Contacts of index cases infected with variants other than Alpha and Delta | ||||||

| Unvaccinated contact and case | 178 | 77 | 43 | 1 | 1 | Reference |

| Unvaccinated contact and vaccinated case | 2 | 1 | 50 | 1.16 (0.16–8.31) | 1.01 (0.14–7.39) | –1 (–639 to 86) |

| Vaccinated contact and unvaccinated case | 145 | 20 | 14 | 0.32 (0.20–0.52) | 0.47 (0.25–0.92) | 53 (8 to 75) |

| Vaccinated contact and case | 14 | 3 | 21 | 0.50 (0.16–1.57) | 0.76 (0.22–2.68) | 24 (–168 to 78) |

RR: relative risk; VE: vaccine effectiveness; contact means close contact; case means index case.

Relative risk adjusted by age groups (18–34, 35–49, 50–69 and ≥70 years), sex, major chronic condition of close contacts, and month of contact.

Discussion

The results demonstrate that COVID-19 vaccination significantly reduces the susceptibility of persons exposed to SARS-CoV-2, and that infected persons who had previously been vaccinated against COVID-19 are less infectious for their close contacts. However, vaccination of both did not show complete synergy and these effects were lower in older people.

In the absence of COVID-19 vaccination, we found a risk of transmission from an infected person to their close social contacts of 26% on average. COVID-19 vaccination reduced the susceptibility of close contact by 69%, and the previously vaccinated infected persons were 44% less infectious for their contacts. Vaccination of the index case and close contact reduced the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in social settings by 74%, slightly less than expected assuming a complete synergy of both vaccination effects.

Although SARS-CoV-2 transmission could happen from asymptomatic index cases, symptomatic cases were more infectious for their close contacts, as previous studies have observed [20], [25], [26]. In the present study, compared to the Alpha variant dominance period, the secondary attack rates within each vaccination category of the index case and contact were higher in the Delta variant period. A consistent finding was seen in the analysis of close contacts of index cases with the L452R mutation characteristic of the Delta variant [27]. Nevertheless, point estimates of effectiveness in preventing transmission by COVID-19 vaccination of the index case or close contact were similar or higher in the Delta variant period and when the Delta variant was detected in the index case, which contrasts with the results of other authors that have described lower vaccine effectiveness against the Delta variant [28]. However, these estimates are consistent with the more rapid decline in viral load observed in vaccinated cases infected by the Delta variant [29].

Compared with social settings, in the household setting, the risk of transmission between unvaccinated persons was higher and the vaccination effects in reducing infectiousness and transmission were lower. The more intense and repeated exposures in close household contacts may result in a higher risk of transmission and a reduced effect of preventive measures [5], [20]. In older people cohabiting, a paradoxical lower preventive effect of the close contact vaccination was observed when the index case was also vaccinated. The lack of a plausible biological explanation suggests that this lower protective effect may be due to an increased risk assumption and relaxation in non-pharmacological preventive measures when the index case and the close household contact were both vaccinated.

Early studies on the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines reported a very low risk of infection in vaccinated people and a low risk of transmission from vaccinated cases [6], [10]. As a result of these findings, the protocols for COVID-19 control proposed relaxer recommendations for vaccinated than unvaccinated close contacts [21], and the population could misunderstand that other preventive measures were no longer necessary among fully vaccinated persons. Since general mandatory measures, such as facemask use or social distancing were maintained in social settings, the relaxation mainly affected household contacts. Further studies have evidenced that the vaccination effect in preventing transmission was only partial and that additional preventive measures are necessary for efficient SARS-CoV-2 transmission control [9], [30].

The mentioned paradoxical decrease in the preventive effect was mainly observed in older close household contacts. In households, compliance to preventive measures is difficult to maintain during continuous exposure and the vaccination status of the other cohabitants is usually well known, so fully vaccinated cohabitants could easily assume relaxation in preventive measures. The consequences of this lower protection are worse in older people due to the lower and less lasting effect of the vaccines [7].

The possible relaxation of preventive measures following vaccination may introduce a bias in studies of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in preventing infections; therefore, the results of studies that do not achieve good control of this bias may underestimate vaccine effectiveness. Furthermore, the subsequent changes in preventive behaviors could hide part of the impact of vaccination on SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

The present results are consistent with previous studies showing that the current vaccination programs are not able to achieve complete control of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, especially in ageing populations [7]. In these cases, complementary preventive measures may be necessary, as social distancing and use of facemasks [8].

The strengths of this study are the prospective open cohort design of close contacts of confirmed cases of COVID-19. The recruitment was based on a contact-tracing protocol, which was the same for all the population and remained unchanged during the study period. As two cohorts were studied, the comparison of their results provides complementary views of the effect of vaccination on SARS-CoV-2 transmission under different conditions. Variables were obtained before the outcome was known. Close contacts were classified according to the test result.

This study may have limitations. Close contacts that did not complete the testing protocol (3.3%; 2027/62,355) were excluded from the analysis; therefore potential selection bias due to loss of follow up would be small. Vaccine effectiveness estimates may be conditioned by the time since vaccination and the circulating SARS-CoV-2 strains during the study period; therefore, these results may not be valid for earlier or later periods [31]. Vaccination coverage varied with age, major chronic conditions, and month, but analyses were adjusted for these variables. Symptomatic patients with positive antigen test were included; however, a previous study found no interference in estimates [7]. People younger than 18 years were excluded because they were not the target population for vaccination during almost the entire study period. The effect of vaccination could be affected by the possible relaxation in preventive measures after vaccination. Although the study population was composed of close contacts of infected cases, we cannot rule out some differential changes in the frequency and intensity of the contact after vaccination. These changes might bias the vaccine effectiveness estimates. The paradoxical results found in old household contacts, but not in other groups, strongly suggest the effect of behavioral changes after vaccination. The effect of partial vaccination on transmission was based on an insufficient number of cases to achieve conclusions. During the study period booster doses were not used and the Omicron variant was not detected; therefore, we cannot conclude on the vaccination effect in these contexts [32]. Other factors such as the time since the last vaccine dose and the vaccine brand may modify the vaccine effect and were not considered in the present study. SARS-CoV-2 sequencing was only available in a part of the index cases; however, the results defined periods of dominance of each variant.

In conclusion, the results support that COVID-19 vaccination significantly reduces the susceptibility of persons exposed to the SARS-CoV-2 and that infected persons vaccinated against COVID-19 are less infectious for their contacts. However, these effects are insufficient for total control of SARS-CoV-2 transmission, since fully vaccinated people may be infected and transmit the infection for their close contacts. Furthermore, these results suggest that relaxation of preventive behaviors may counteract part of the vaccine effect on transmission, especially in older people in the household. Therefore, non-pharmaceutical preventive measures remain relevant around highly vulnerable people even among fully vaccinated individuals, as long as there is evidence of SARS-CoV-2 circulation.

Funding

This study was supported by the Horizon 2020 program of the European Commission (I-MOVE-COVID-19, grant agreement No 101003673), and by the Carlos III Institute of Health with the European Regional Development Fund (COV20/00542, CM19/00154, INT21/00100, and CP22/00016). The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Conflict of interest

All authors have no potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2023.01.017.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

Supplementary material

.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: implications for infection prevention precautions [Internet]. Available in: 〈https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/transmission-of-sars-cov-2-implications-for-infection-prevention-precautions〉.

- 2.Lu J., Gu J., Li K., Xu C., Su W., Lai Z., et al. COVID-19 outbreak associated with air conditioning in restaurant, Guangzhou, China, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1628–1631. doi: 10.3201/eid2607.200764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prather K.A., Marr L.C., Schooley R.T., McDiarmid M.A., Wilson M.E., Milton D.K. Airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;370:303–304. doi: 10.1126/science.abf0521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guidelines for non-pharmaceutical interventions to reduce the impact of COVID-19 in the EU/EEA and the UK. 24 September 2020. ECDC: Stockholm; 2020. 〈https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/covid-19-guidelines-non-pharmaceutical-interventions-september-2020.pdf〉.

- 5.Baden L.R., El Sahly H.M., Essink B., Kotloff K., Frey S., Novak R., et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:403–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haas E.J., Angulo F.J., McLaughlin J.M., Anis E., Singer S.R., Khan F., et al. Impact and effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infections and COVID-19 cases, hospitalisations, and deaths following a nationwide vaccination campaign in Israel: an observational study using national surveillance data. Lancet. 2021;397:1819–1829. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00947-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martínez-Baz I., Miqueleiz A., Casado I., Navascués A., Trobajo-Sanmartín C., Burgui C., et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection and hospitalisation, Navarre, Spain, January to April 2021. Eur Surveill. 2021;26 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.21.2100438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hacisuleyman E., Hale C., Saito Y., Blachere N.E., Bergh M., Conlon E.G., et al. Vaccine breakthrough infections with SARS-CoV-2 variants. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2212–2218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sachdev D.D., Chew Ng R., Sankaran M., Ernst A., Hernandez K.T., Servellita V., et al. Contact tracing outcomes among household contacts of fully vaccinated COVID-19 patients - San Francisco, California, January 29-July 2, 2021. Clin Infect Dis 2021:ciab1042. 10.1093/cid/ciab1042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Prunas O., Warren J.L., Crawford F.W., Gazit S., Patalon T., Weinberger D.M., et al. Vaccination with BNT162b2 reduces transmission of SARS-CoV-2 to household contacts in Israel. Science. 2022;375:1151–1154. doi: 10.1126/science.abl4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mostaghimi D., Valdez C.N., Larson H.T., Kalinich C.C., Iwasaki A. Prevention of host-to-host transmission by SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:e52–e58. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00472-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine-Tiefenbrun M., Yelin I., Katz R., Herzel E., Golan Z., Schreiber L., et al. Initial report of decreased SARS-CoV-2 viral load after inoculation with the BNT162b2 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27:790–792. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01316-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milman O., Yelin I., Aharony N., Katz R., Herzel E., Ben-Tov A., et al. Community-level evidence for SARS-CoV-2 vaccine protection of unvaccinated individuals. Nat Med. 2021;27:1367–1369. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01407-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koh W.C., Naing L., Chaw L., Rosledzana M.A., Alikhan M.F., Jamaludin S.A., et al. What do we know about SARS-CoV-2 transmission? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the secondary attack rate and associated risk factors. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madewell Z.J., Yang Y., Longini I.M., Jr, Halloran M.E., Dean N.E. Factors associated with household transmission of SARS-CoV-2: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.22240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jing Q.L., Liu M.J., Zhang Z.B., Fang L.Q., Yuan J., Zhang A.R., et al. Household secondary attack rate of COVID-19 and associated determinants in Guangzhou, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:1141–1150. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30471-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson H.A., Mousa A., Dighe A., Fu H., Arnedo-Pena A., Barrett P., et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) setting-specific transmission rates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73:e754–e764. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo L., Liu D., Liao X., Wu X., Jing Q., Zheng J., et al. Contact settings and risk for transmission in 3410 close contacts of patients with COVID-19 in Guangzhou, China: a prospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:879–887. doi: 10.7326/M20-2671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogata T., Irie F., Ogawa E., Ujiie S., Seki A., Wada K., et al. Secondary attack rate among non-spousal household contacts of coronavirus disease 2019 in Tsuchiura, Japan, August 2020-February 2021. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:8921. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18178921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martínez-Baz I., Trobajo-Sanmartín C., Burgui C., Casado I., Castilla J. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 infection and risk factors in a cohort of close contacts. Post Med. 2022;134(2):230–238. doi: 10.1080/00325481.2022.2037360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ministerio de Sanidad. Estrategia de detección precoz, vigilancia y control de COVID-19. [Strategy for early detection, surveillance and COVID-19 control]. Madrid: Ministerio de Sanidad; 2021. Spanish. Available from: 〈https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/ccayes/alertasActual/nCov/documentos/COVID19_Estrategia_vigilancia_y_control_e_indicadores.pdf〉.

- 22.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Contact tracing: public health management of persons, including healthcare workers, who have had contact with COVID-19 cases in the European Union –third update, 18 November 2020. Stockholm: ECDC; 2020. Available from: 〈https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/covid-19-contact-tracing-public-health-management-third-update.pdf〉.

- 23.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Methods for the detection and characterisation of SARS-CoV-2 variants – first update. 20 December 2021. Stockholm/Copenhagen; ECDC/WHO Regional Office for Europe: 2021.

- 24.Consejo Interterritorial del Sistema Nacional de Salud. Estrategia de vacunación frente a COVID-19 en España. Actualización 6, 20 abril 2021. Ministerio de Sanidad, Consumo y Bienestar Social. Available from: 〈https://www.mscbs.gob.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/vacunaciones/covid19/docs/COVID-19_Actualizacion6_EstrategiaVacunacion.pdf〉.

- 25.Qiu X., Nergiz A.I., Maraolo A.E., Bogoch I.I., Low N., Cevik M. The role of asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic infection in SARS-CoV-2 transmission-a living systematic review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:511–519. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones T.C., Biele G., Mühlemann B., Veith T., Schneider J., Beheim-Schwarzbach J., et al. Estimating infectiousness throughout SARS-CoV-2 infection course. Science. 2021;373:eabi5273. doi: 10.1126/science.abi5273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Trobajo-Sanmartín C., Martínez-Baz I., Miqueleiz A., Fernández-Huerta M., Burgui C., Casado I., et al. Differences in transmission between SARS-CoV-2 Alpha (B.1.1.7) and Delta (B.1.617.2) variants. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(2) doi: 10.1128/spectrum.00008-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eyre D.W., Taylor D., Purver M., Chapman D., Fowler T., Pouwels K.B., et al. Effect of Covid-19 vaccination on transmission of Alpha and Delta variants. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:744–756. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2116597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singanayagam A., Hakki S., Dunning J., Madon K.J., Crone M.A., Koycheva A., et al. Community transmission and viral load kinetics of the SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) variant in vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals in the UK: a prospective, longitudinal, cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:183–195. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00648-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Gier B., Andeweg S., Backer J.A., Hahné S.J., van den Hof S., de Melker H.E., et al. Vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 transmission to household contacts during dominance of Delta variant (B.1.617.2), the Netherlands, August to September 2021. Eur Surveill. 2021;26 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.44.2100977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braeye T., Cornelissen L., Catteau L., Haarhuis F., Proesmans K., De Ridder K., et al. Vaccine effectiveness against infection and onwards transmission of COVID-19: Analysis of Belgian contact tracing data, January-June 2021. Vaccine. 2021;39:5456–5460. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.08.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monge S., Rojas-Benedicto A., Olmedo C., Mazagatos C., José Sierra M., Limia A., et al. Effectiveness of mRNA vaccine boosters against infection with the SARS-CoV-2 omicron (B.1.1.529) variant in Spain: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;S1473–3099(22):00292–00294. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00292-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material