Abstract

Understanding the extent to which beneficiaries can “realize” access to reported provider networks is imperative in mental health care, where there are significant unmet needs. We compared listings of providers in network directories against provider networks empirically constructed from administrative claims among members who were ages sixty-four and younger and enrolled in Oregon’s Medicaid managed care organizations between January 1 and December 31, 2018. “In-network” providers were those with any medical claims filed for at least five unique Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in a given health plan. They included primary care providers, specialty mental health prescribers, and nonprescribing mental health clinicians. Overall, 58.2 percent of network directory listings were “phantom” providers who did not see Medicaid patients, including 67.4 percent of mental health prescribers, 59.0 percent of mental health nonprescribers, and 54.0 percent of primary care providers. significant discrepancies between the providers listed in directories and those whom enrollees can access suggest that provider network monitoring and enforcement may fall short if based on directory information.

Health insurance plans are required to make accessible a list of all health care providers and facilities with which they have contracted to provide medical care to their members. Patients rely on these lists to make informed choices when selecting health plans or locating in-network providers. State and federal regulators may also use these directories to assess whether health plans are compliant with network adequacy standards. However, studies suggest widespread inaccuracies in provider directories, with growing concerns about “phantom networks,” in which the participating providers do not see patients in a given plan for a variety of reasons.1,2 In essence, such networks may satisfy network adequacy requirements on paper but not in practice, potentially including providers who hold active licenses but are clinically inactive, have moved, or have closed their panels to new patients. A 2018 report by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services found that more than half of provider listings in Medicare Advantage provider directories included at least one inaccuracy,3 matching the findings of other audit and secret shopper studies that found large numbers of duplicate listings, erroneous contact information, and providers who were not in network within primary care and other medical and surgical specialties.4,5

Understanding the extent to which beneficiaries can “realize” access to reported provider networks is particularly important in mental health care. Mental health services are up to six times more likely than general medical services to be delivered out of network,6 and approximately sixteen million US adults report an unmet need for mental health treatment.7 Inaccurate provider directories may result in delayed treatment, discontinuities in care, patient frustration, and the inability to obtain necessary care. A 2018 national survey of mental health consumers with commercial insurance found that a quarter of patients who used provider directories to identify potential providers had encountered directory inaccuracies.8 In another study, published in 2015, only one-third of all psychiatrists listed in a provider directory for a major commercial insurer were reachable by phone, with appointments able to be made for only 26 percent of them.9

Although others have examined the accuracy of provider directories via secret shopper studies and audits,4,5 these studies have largely been in commercial populations, and there is scant evidence in the context of Medicaid. Medicaid is the largest payer for mental health services in the US and is characterized by a high demand for mental health services, low provider participation,9,10 rural facility shortages,11 and populations with disproportionate social and medical complexities and incidence of serious mental illness.12 In addition, the influence of provider networks is potentially greater in the Medicaid program than in commercial insurance, because out-of-pocket payment is often unaffordable and because enrollees are generally limited to contracted providers and do not typically have cost-sharing options for going out of network for nonemergent care.13,14 Limited information about Medicaid directories points to discrepancies similar to those found in commercial directories in the accuracy of provider contact information, practice location, and acceptance of new patients.15,16

In this cross-sectional study we compared provider directory data in Oregon’s Medicaid managed care program with empirically constructed provider networks, using administrative claims data. Medicaid managed care covers more than 80 percent of Oregon’s Medicaid enrollees and about 70 percent of enrollees nationally.17 This research is among the first to use claims data to identify the degree to which provider directories reflect “realized” access to mental health services in Medicaid managed care.

Study Data And Methods

MEDICAID CLAIMS DATA

Oregon’s Medicaid managed care program is run through fifteen coordinated care organizations (CCOs), which cover distinct geographic areas and combine elements of Medicaid managed care organizations and accountable care organizations in how they accept financial risk and pay for care.18–20 We identified members ages sixty-four and younger who were enrolled in Oregon’s Medicaid program between January 1, 2018, and December 31, 2018, regardless of whether the enrollment was continuous. We excluded all dual-eligible (both Medicaid and Medicare) and fee-for-service beneficiaries because of data availability limitations and differences in population, health care needs, service use, claims, and reimbursement.We also excluded the 2 percent of enrollees who switched CCOs during the study period because they moved to a different coverage area.

Based on this member cohort, we then constructed a sample of in-network providers empirically using medical claims data. Providers were considered to be in network for a given CCO if they were associated with any medical claims filed for at least five unique Medicaid beneficiaries enrolled in that CCO during the study period.21 This threshold was chosen for its clinical relevance and tested for robustness using alternative thresholds of one and ten Medicaid beneficiaries. Using information from the National Plan and Provider Enumeration System, we identified the following types of providers: primary care providers, specialty mental health prescribers (psychiatrists and mental health nurse practitioners), and nonprescribing mental health specialists (therapists and counselors, clinical nurse specialists with a mental health focus, psychologists, and social workers). We included primary care providers because they deliver a large share of mental health services.22

PROVIDER DIRECTORY DATA

We obtained 2018 data from the Delivery System Network Provider Capacity Report, a provider directory, for each CCO. CCOs are required by the State of Oregon to submit this report annually to demonstrate compliance with federal and state network adequacy regulations.23 To be included in the report, participating providers must have contracted with CCOs to provide specified services to Medicaid enrollees. Data compiled from provider directories included clinicians’ names, specialties, and types, as well as National Provider Identifier (NPI) records, Medicaid ID numbers, credentialing information, affiliated facility information, and locations. As we did with the claims data, we used National Plan and Provider Enumeration System information to attach provider specialties and types in the directory files.

ANALYSIS

Using both claims and network directory data, we calculated provider-to-enrollee ratios based on in-network providers per CCO. This ratio is commonly used to calculate how many providers are available in a service area;24 state and federal regulators also use it to assess the sufficiency of a provider network. We defined this measure as the total number of in-network providers per 1,000 enrollees, as derived from Medicaid claims.

We then compared provider networks, including numbers and types of providers, reported in the provider directories with networks that we empirically constructed from claims data. We calculated the degree of overlap among providers in directories and claims, using a denominator that included providers whom Medicaid beneficiaries saw according to claims data but who were not listed in directories.

To assess the accuracy of directory reporting, we restricted all subsequent analyses to those providers whom the CCOs listed in their plan directories. Using this denominator, we distinguished two different circumstances: A health plan listed a provider in its directory and claims data reflect that the provider indeed saw the CCO’s patients (“listed and accessed”); or a health plan included a given provider in its directory, but claims data do not reflect that the provider actually saw the CCO’s patients (“listed but not accessed”—that is, “phantom”). We generated a measure of realized access at the CCO level: the percentage of providers in the provider directory files who were also in network based on claims (that is, a ratio of in-network providers by claims to total providers reported in the directory files).

To calculate Medicaid panel size, we identified total patients from the member cohort for which each provider had claims during the study year and then computed a median provider panel size for each CCO. For descriptive purposes, we identified rural or urban status of CCOs based on the percentage of enrollees from the member cohort with rural or urban residence (≥70 percent urban is “urban” and ≤30 percent urban is “rural”; 30–70 percent urban is “mixed”). Analyses were conducted using R, version 4.0.3. The study protocol was reviewed and deemed exempt by the Institutional Review Board at Oregon Health & Science University.

LIMITATIONS

This study had a number of limitations. First, information from the provider directory files is self-reported by CCOs, and data accuracy may vary depending on resources and staffing capacity across organizations. Second, not all mental health providers bill the Medicaid program directly for services. Some providers may be hired as salaried staff by hospitals or clinics (for example, a social worker in a primary care clinic who performs some mental health counseling) or funded through organizational revenue streams or grants. In such cases, although the providers are available to patients, services may be billed under an organizational NPI or might not show up in claims at all. We found that more than 95 percent of evaluation and management claims were associated with an individual rather than an organizational NPI, but we were unable to estimate the share of providers who do not directly bill Medicaid for their services. This may have led to an underestimate of the number of in-network providers that we empirically identified using claims data.

Third, although we used a threshold of five Medicaid beneficiaries in the observation period to identify in-network providers, those seeing fewer Medicaid patients could still be in network and technically available to patients. Fourth, our study was restricted to the state of Oregon and thus is not necessarily generalizable to other states. However, Oregon’s Medicaid managed care program reflects the state of health care delivery in many states, in that there is substantial variability in provider networks and no variability in patient cost sharing.18–20 Our focus on a single state allowed us to study these provider networks within a relatively homogenous administrative setting. Finally, although our definition of in network encompassed all encounters, including telehealth, our study period preceded the COVID-19 pandemic, during which telehealth use expanded significantly.25,26 Further work should examine how telehealth capacity is reflected in provider directories and contributes to meeting network adequacy requirements.

Study Results

Provider directory files included 7,899 unique primary care providers, 722 mental health prescribers, and 6,824 mental health nonprescribers in Medicaid managed care networks in Oregon in 2018. In comparison, based on claims data, there were a total of only 6,502 unique primary care providers, 582 mental health prescribers, and 5,950 mental health nonprescribers in Medicaid managed care networks. The absolute count discrepancies between provider directories and in-network claims providers varied across CCOs, ranging from a handful of providers to differences in the thousands. See online appendix A1 for raw provider counts by CCO.27

On average, provider-to-enrollee ratios were lowest for specialty mental health prescribers, followed by nonprescribing mental health specialists and primary care providers (exhibit 1). Across all provider types, there were significant discrepancies in the provider-to-enrollee ratios calculated from data from provider directories versus those from claims. For example, there were 4.0 mental health prescribers per 1,000 enrollees using provider directory counts versus 0.7 mental health prescribers per 1,000 enrollees using claims data—a discrepancy of more than fivefold.

EXHIBIT 1.

Discrepancies in provider-to-enrollee ratios in coordinated care organizations (CCOs) using provider directory versus claims data in Oregon Medicaid, by provider type, 2018

| Mental health |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care |

Prescribers |

Nonprescribers |

|||||

| CCO | Rural or urban | Directory | Claims | Directory | Claims | Directory | Claims |

| A | Urban | 8.8 | 6.6 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 15.2 | 9.4 |

|

| |||||||

| B | Rural | 132.2 | 20.0 | 12.9 | 1.6 | 48.2 | 9.0 |

|

| |||||||

| C | Rural | 36.6 | 11.8 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 8.1 | 5.3 |

|

| |||||||

| D | Rural | 135.6 | 18.5 | 12.0 | 1.1 | 37.5 | 10.6 |

|

| |||||||

| E | Mixed | 11.1 | 11.2 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 4.9 | 8.3 |

|

| |||||||

| F | Urban | 4.3 | 7.0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 5.0 | 5.0 |

|

| |||||||

| G | Urban | 9.4 | 8.7 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 8.4 | 6.4 |

|

| |||||||

| H | Mixed | 20.2 | 8.9 | 2.7 | 0.9 | 7.3 | 6.1 |

|

| |||||||

| I | Urban | 108.6 | 13.6 | 10.6 | 0.8 | 44.7 | 10.5 |

|

| |||||||

| J | Rural | 28.0 | 7.0 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 9.9 | 6.8 |

|

| |||||||

| K | Rural | 96.8 | 9.8 | 11.1 | 0.6 | 50.3 | 5.1 |

|

| |||||||

| L | Rural | 16.6 | 19.6 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 18.1 | 11.1 |

|

| |||||||

| M | Rural | 3.9 | 6.9 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 4.1 | 4.5 |

|

| |||||||

| N | Mixed | 24.2 | 7.8 | 2.8 | 0.5 | 12.6 | 6.5 |

|

| |||||||

| O | Rural | 5.7 | 7.1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 7.2 | 5.9 |

|

| |||||||

| Overall | —a | 42.8 | 11.0 | 4.0 | 0.7 | 18.8 | 7.4 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of 2018 Medicaid managed care health plan provider directory files and Oregon Medicaid claims data. NOTES The exhibit shows provider-to-enrollee ratios across provider types and CCOs (Oregon’s Medicaid managed care organizations), defined as number of providers per 1,000 enrollees. CCOs are deidentified to preserve anonymity for individual organizations. Provider types were primary care providers, specialty mental health prescribers, and nonprescribing mental health specialists; see the text for providers in each type. Rural or urban status is based on percent of enrollees from the member cohort with rural or urban residence, as defined in the text. Raw provider counts by CCO are in appendix A1 (see note 27 in text).

Not applicable.

Of the full universe of unique providers across both provider directories and claims (not shown), on average, 51.8 percent appeared in a directory but did not see patients in the claims data (range, 10.7–90.3 percent), 32.4 percent were listed in the directory and also recorded claims encounters with patients (range, 7.9–53.6 percent), and 15.7 percent appeared in the claims as seeing patients even though they were not listed in the directory (range, 1.8–37.2 percent).

To assess the accuracy of directory reporting, all subsequent analyses were restricted only to providers whom CCOs listed in directories. These providers typically contracted with multiple CCOs; 61.2 percent of primary care providers contracted with more than one CCO (mean, 3.0), whereas 63.9 percent of specialty mental health prescribers and 36.1 percent of nonprescribing mental health specialists contracted with more than one CCO (mean, 3.0 and 1.8 CCOs, respectively) (data not shown).

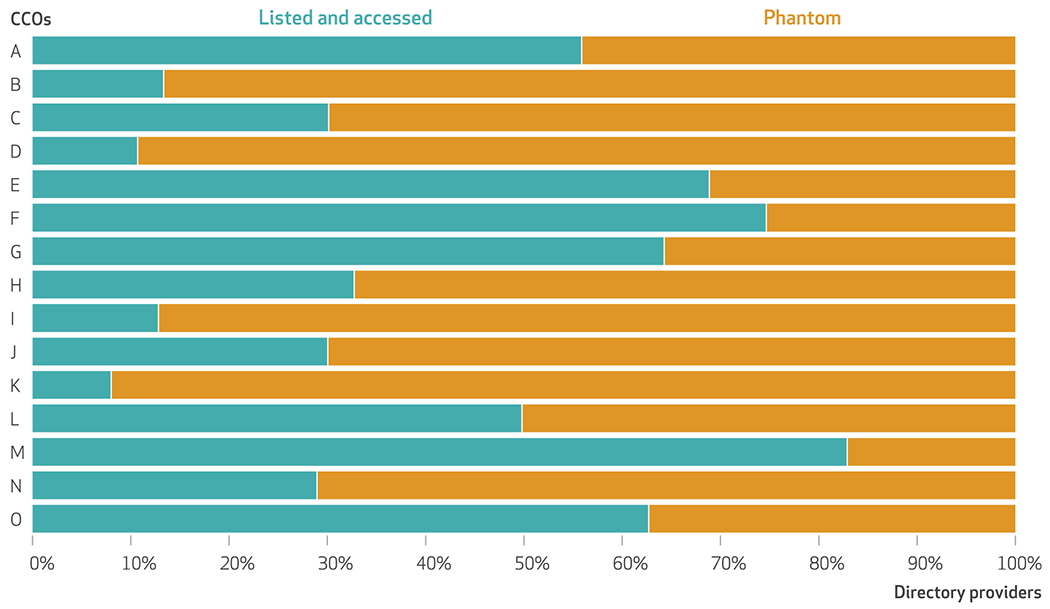

Exhibit 2 shows our comparison of provider directory files and claims data. Of those listed in provider directories, 58.2 percent were “phantom” providers who did not see Medicaid patients in the study period (range, 17.1–91.9 percent). When we stratified by provider type, we found that 67.4 percent of mental health prescribers listed in directories were phantom providers, versus 59.0 percent of mental health nonprescribers and 54.0 percent of primary care providers. Conversely, listed and accessed providers represented 41.8 percent. See appendix A2 for raw counts comparing provider directory and claims data, stratified by provider type.27

EXHIBIT 2. Proportion of plan directory providers that were listed and accessed versus not accessed, or “phantom,” in Oregon Medicaid, by coordinated care organization (CCO), 2018.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of 2018 Medicaid managed care health plan provider directory files and Oregon Medicaid claims data. NOTES This exhibit shows the proportion of all directory-listed providers (primary care providers, specialty mental health prescribers, and nonprescribing mental health specialists; see the text for provider types in each group) that fall into the following categories: a health plan listed a provider in their directory and the provider saw the coordinated care organization’s patients in the claims data (“listed and accessed”); or a health plan included a provider in their provider directory, but the provider did not see that coordinated care organization’s patients in the claims data (“listed but not accessed,” or “phantom” providers). CCOs are Oregon’s Medicaid managed care organizations; they are deidentified to preserve anonymity for individual organizations.

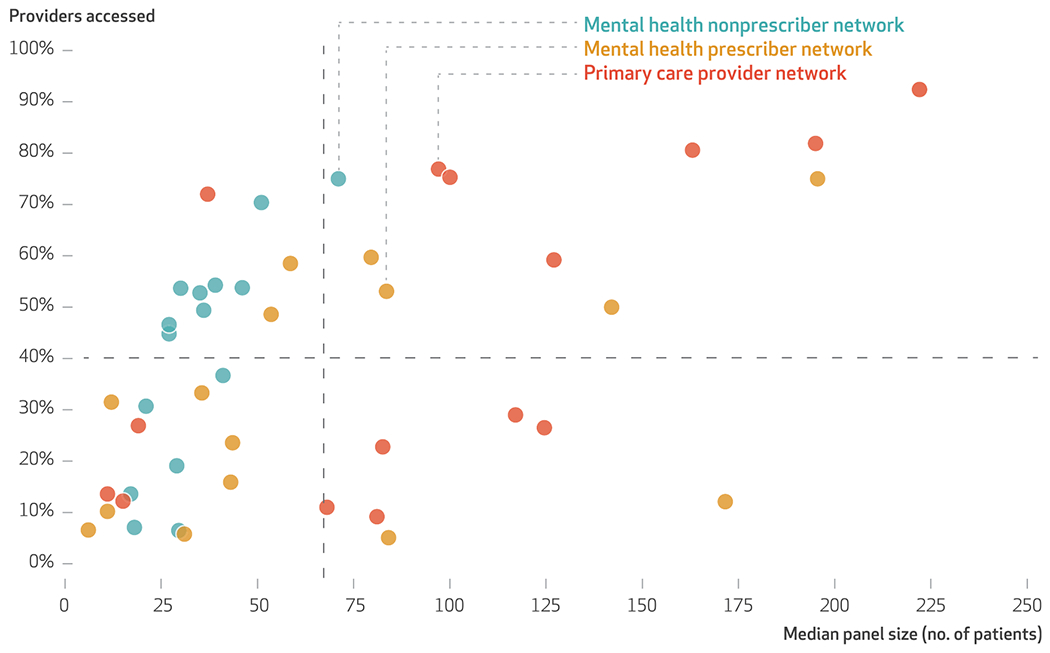

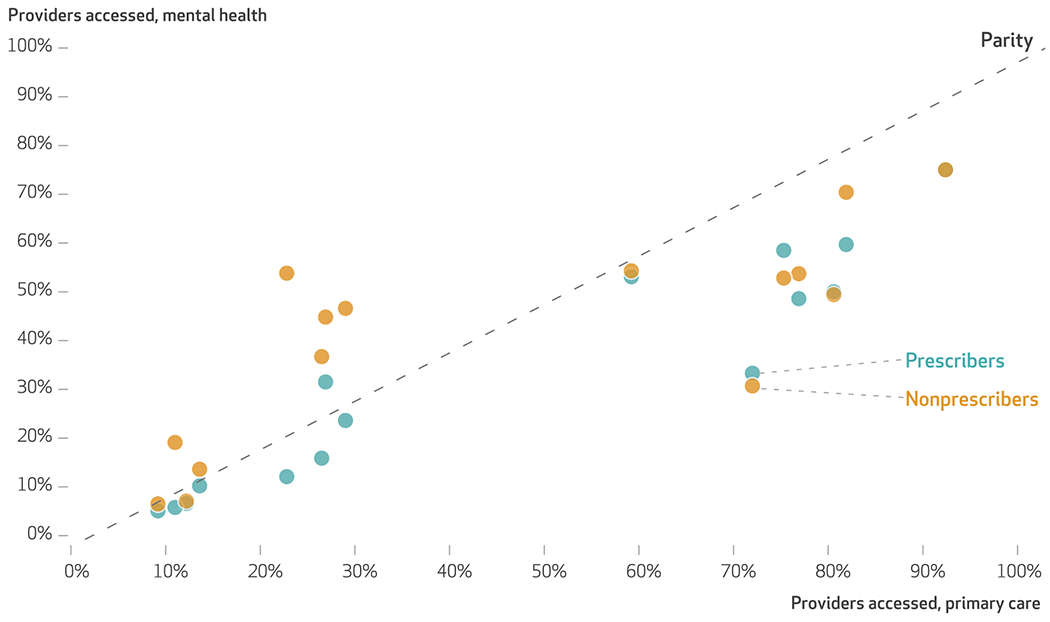

Exhibit 3 shows how the proportion of providers accessed varied across CCOs and by provider type. On average, primary care provider networks had higher realized access (46.0 percent of directory providers were listed and accessed) than networks of mental health prescribers (32.6 percent) and nonprescribing clinicians (41.0 percent). Across all provider types, lower realized access was associated with smaller median patient panel sizes. For mental health prescribers, CCOs had lower access and larger patient panel sizes (median panel size, 70.0) compared with mental health nonprescribers (median panel size, 34.5). CCOs’ networks also typically clustered toward having either relatively lower versus higher access for all provider types, although access to primary care was generally higher than access to specialty mental health providers (exhibit 4).

EXHIBIT 3. Percent of providers accessed versus Medicaid panel sizes for different provider network types in Oregon, by coordinated care organization (CCO), 2018.

SOURCE Authors’analysis of 2018 Medicaid managed care health plan provider directory files and Oregon Medicaid claims data. NOTES This exhibit shows CCO-level plots of “realized access” versus Medicaid panel sizes for different provider network types (primary care, mental health prescribers, and mental health nonprescribers). “Realized access” was defined as the percent of providers in the provider directory files who were also in network based on claims (that is, a ratio of in-network providers by claims to total providers reported in the directory files). Each data point represents a CCO (Oregon’s Medicaid managed care organizations). To calculate Medicaid panel size, we identified total patients from the member cohort for which providers had claims during the study year and then computed a median for each CCO. The dashed lines represent the average median panel size and percent of providers accessed across all CCOs.

EXHIBIT 4. Comparison of realized access across coordinated care organizations (CCO)s in Oregon Medicaid managed care, for mental health providers versus primary care providers, 2018.

SOURCE Authors’analysis of 2018 Medicaid managed care health plan provider directory files and Oregon Medicaid claims data. NOTES This exhibit presents a comparison of “realized access” across provider types. Each data point represents a coordinated care organization (CCO), Oregon’s Medicaid managed care organizations. “Realized access” is defined in the exhibit 3 notes. Any dot on the dashed “Parity” line represents a CCO with parity in realized access between primary care and specified groups of mental health care providers (specialty mental health prescribers and nonprescribing mental health specialists).

Discussion

Prior audit and secret shopper studies have reported frequent inaccuracies in provider directories maintained by health plans and state governments.3,5 Although some studies have tended to focus on unreliable or erroneous contact information and locations when assessing the completeness of provider directories, directories should also accurately reflect the set of providers who are available and accessible to patients in a given plan. This study was among the first to use claims data to evaluate the extent to which listed providers actually see patients. Overall, we found that in 2018, 58.2 percent of primary care and specialty mental health providers in health plan directories, including two-thirds of mental health prescribers, were listed but did not see patients in the plan. We included these providers in our definition of phantom networks—that is, networks in which some listed providers do not see patients for various reasons. Although phantom networks may satisfy network adequacy requirements on paper, they may contribute to delays and disruptions in care8 and place cumulative barriers on patients’ ability to obtain mental health care in a timely manner.28–30 These barriers may be particularly detrimental for Medicaid enrollees, who already face disproportionately high rates of serious mental illness, unmet mental health needs, and socioeconomic disparities in care.12

Our results also suggest that a relatively small set of providers may have an outsize impact on Medicaid patients’ access to mental health care, consistent with a recent study by Avital Ludomirsky and coauthors.31 Based on our analysis of claims data, only a third of mental health prescribers listed in directories provided care to Medicaid patients in 2018. A prior study showed that payer-mix distributions among psychiatrists, psychologists, and advanced practice mental health providers were bimodal: Providers typically care primarily for Medicaid patients or for commercially insured patients, without much overlap between the two populations.32 Along this vein, an underappreciated and understudied aspect of Medicaid provider networks may be the extent to which sets of providers provide high volumes of care; the departure of one of these providers from a given network may have a large impact on access to care. Further, these patterns of care delivery are difficult to monitor via commonly used network breadth measures and even more challenging to regulate using current network adequacy standards.

We also found that phantom networks were larger and realized access was lower among specialty mental health providers than among primary care providers. A recent survey-based study by Abigail Burman and Simon Haeder found that primary care provider directories in California appeared to outperform those of four other specialties in terms of accuracy, although mental health was not among the specialties studied.5 Although scant empirical research has focused on provider directory accuracy specifically for mental health providers, other studies have highlighted challenges specific to mental health care, including low provider supply,24,33,34 low participation in insurance networks,35 and high workforce turnover,36,37 all of which could have contributed to our findings and could make it difficult for health plans to maintain adequate mental health provider networks. It is also possible that health plans have little incentive to make mental health care easier to navigate. Although federal parity laws prohibit health plan designs that dissuade people with high-cost chronic mental health conditions from enrolling, the composition of provider networks is one design element that remains difficult to regulate.38 How the accuracy of provider directory files in mental health care compares with that in other specialties is yet unknown.

Despite our measures being normalized by plan enrollment, we nonetheless found high degrees of variation in our measures across CCOs. Some variation in provider counts is expected, appropriate, and likely driven by geographic constraints; for example, the Mental Health Care Health Care Professional Shortage Areas in Oregon are predominantly located in rural areas, where there is low workforce supply.39 However, it is unclear that discrepancies between theoretical access (via provider directories) and realized access (via claims) should vary on the basis of geography alone. Administrative capacity, including data collection and validation, network monitoring, and enforcement mechanisms, may contribute to some of this variation across managed care organizations.

Along these lines, there are many recognized challenges to maintaining and updating provider directories. Health care providers often alter their affiliations, practice sites, network participation, and licensing affiliations, leading to rapidly changing provider data that can be difficult to track. These challenges may explain, at least in part, our findings of small sets of providers who were seeing patients but were unlisted in directories. Our finding that providers contract with multiple health plans likely compounds the administrative and reporting burdens and resource limitations that mental health organizations face in responding to provider directory updates. A recent industry report found that an average physician practice must respond to directory requests associated with twenty health plan contracts, each through separate platforms, formats, and timelines.40 These administrative burdens are likely exacerbated in mental health organizations, which are more likely than physical health organizations to be smaller practices,41 with fewer staff and resources to address these labor-intensive tasks. Researchers have also cited a lack of provider engagement, inconsistent definitions and standards, and inadequate state and federal enforcement as factors that contribute to systemwide hurdles in addressing this issue.4

As a result, our findings bear important implications for ongoing network adequacy monitoring and regulation efforts. Although network adequacy standards are intended to ensure that patients have access to sufficient numbers and types of providers, there remains significant variation across states and insurers in how network adequacy is defined, measured, and enforced.42 For example, the majority of Medicaid programs use time and distance standards, but these standards can range from fifteen to ninety minutes, or from six to sixty miles of travel from an enrollee’s home to a primary care provider. Timely access standards for primary care range from ten to forty-five days for a routine appointment and from one to four days for an urgent appointment.43

A reliance on provider directories that are often inaccurate or out of date may exacerbate this problem. Our analysis showed that one common measure used by state regulatory agencies and health plans to monitor network adequacy (the provider-to-enrollee ratio) may be artificially inflated by a large magnitude when based on provider directories containing phantom networks. Others have also raised the critique that provider-to-enrollee ratios are inaccurate metrics of access because of providers’ participation in multiple networks.44 Claims data, used alongside secret shopper audits and surveys, have the potential to help generate more complete data on provider availability and accessibility.

Efforts to enforce directory accuracy are ongoing. For example, the federal Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022 includes requirements that insurers establish a meaningful verification process for their provider directories, which replicates provisions already implemented in a number of states.45,46 However, as our results suggest, stronger enforcement alone, without the appropriate tools to lessen the burden of data collection and verification, is unlikely to be a panacea. Further attention from plans, regulators, and policy makers is warranted.

Conclusion

Medicaid is a major payer for mental health care in the US, with enrollees disproportionately likely to have severe and persistent mental disorders as well as complex social and medical needs that exacerbate barriers to care.12 Network adequacy is a mechanism to enable Medicaid beneficiaries with mental illness to access the care they need; however, a true understanding of network adequacy is difficult because of inaccuracies in provider directories, which can be administratively burdensome to review and update. Although limited to one state, our findings suggest significant discrepancies between provider directories and the actual availability of providers. These discrepancies suggest that federal and state efforts to monitor and enforce network adequacy standards might not be accurate if they rely on current network directories. Without fixes, these discrepancies also curtail consumers’ ability to obtain transparent and accurate information on in-network provider coverage. ■

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant No. 1K08MH123624 to Jane Zhu). The National Institute of Mental Health had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Zhu also reports receiving consultant fees from Omada Health and grant support from the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation, and the Oregon Health Authority that are unrelated to this work.

Contributor Information

Jane M. Zhu, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, Oregon

Christina J. Charlesworth, Oregon Health & Science University

Daniel Polsky, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland.

K. John McConnell, Oregon Health & Science University.

NOTES

- 1.Barry CL, Huskamp HA, Goldman HH. A political history of federal mental health and addiction insurance parity. Milbank Q. 2010;88(3):404–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGinty EE, Busch SH, Stuart EA, Huskamp HA, Gibson TB, Goldman HH, et al. Federal parity law associated with increased probability of using out-of-network substance use disorder treatment services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(8):1331–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Online provider directory review report [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2018. 28 Nov [cited 2022 May 19]. [Third year]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/ManagedCareMarketing/Downloads/Provider_Directory_Review_Industry_Report_Round_3_11-28-2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adelberg M, Frakt A, Polsky D, Strollo MK. Improving provider directory accuracy: can machine-readable directories help? Am J Manag Care. 2019;25(5):241–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burman A, Haeder SF. Potemkin protections: assessing provider directory accuracy and timely access for four specialties in California. J Health Polit Policy Law. 2022;47(3):319–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelech D, Hayford T. Medicare Advantage and commercial prices for mental health services. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019; 38(2):262–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health [Internet]. Rockville (MD): SAMHSA; 2021. Oct [cited 2022 May 31]. Available from: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/reports/rpt35325/NSDUHFFRPDFWHTMLFiles2020/2020NSDUHFFR1PDFW102121.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busch SH, Kyanko KA. Incorrect provider directories associated with out-of-network mental health care and outpatient surprise bills. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(6):975–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malowney M, Keltz S, Fischer D, Boyd JW. Availability of outpatient care from psychiatrists: a simulated-patient study in three U.S. cities. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(1):94–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilk JE, West JC, Narrow WE, Rae DS, Regier DA. Access to psychiatrists in the public sector and in managed health plans. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(4):408–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cummings JR, Wen H, Ko M, Druss BG. Geography and the Medicaid mental health care infrastructure: implications for health care reform. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(10):1084–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Access to mental health services for adults covered by Medicaid [Internet]. Washington (DC): MACPAC; 2021. Jun [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: https://www.macpac.gov/publication/access-to-mental-health-services-for-adults-covered-by-medicaid/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garfield R, Hinton E, Cornachione E, Hall C. Medicaid managed care plans and access to care: results from the Kaiser Family Foundation 2017 Survey of Medicaid Managed Care Plans [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2018. Mar 5 [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/report-section/medicaid-managed-care-plans-and-access-to-care-provider-networks-and-access-to-care/ [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Council on Disability. Medicaid managed care for people with disabilities [Internet]. Washington (DC): NCD; 2015. Chapter 1, An overview of Medicaid managed care [cited 2022 May 31]. Available from: https://www.ncd.gov/policy/chapter-1-overview-medicaid-managed-care [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maryland Department of Health. Medicaid managed care organization: network adequacy validation, assessing accuracy of provider directories report [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): The Department; 2018. Feb [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: https://health.maryland.gov/mmcp/healthchoice/Documents/CY%202017%20Assessing%20Accuracy%20of%20Provider%20Directories%20FINAL.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Access to care: provider availability in Medicaid managed care [Internet]. Washington (DC): HHS; 2014. Nov 8 [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-13-00670.asp [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid managed care market tracker [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): KFF; 2019. [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/data-collection/medicaid-managed-care-market-tracker/ [Google Scholar]

- 18.McConnell KJ. Oregon’s Medicaid coordinated care organizations. JAMA. 2016;315(9):869–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McConnell KJ, Chang AM, Cohen DJ, Wallace N, Chernew ME, Kautz G, et al. Oregon’s Medicaid transformation: an innovative approach to holding a health system accountable for spending growth. Healthc (Amst). 2014;2(3):163–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McConnell KJ, Renfro S, Lindrooth RC, Cohen DJ, Wallace NT, Chernew ME. Oregon’s Medicaid reform and transition to global budgets were associated with reductions in expenditures. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(3):451–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charlesworth CJ, Zhu JM, Horvitz-Lennon M, McConnell KJ. Use of behavioral health care in Medicaid managed care carve-out versus carve-in arrangements. Health Serv Res. 2021;56(5):805–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cherry D, Albert M, McCaig LF. Mental health-related physician office visits by adults aged 18 and over: United States, 2012–2014 [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. Jun [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db311.htm [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.State of Oregon. 2019 DSN Provider Capacity Report protocol [Internet]. Salem (OR): Oregon Health Authority; [cited 2022 May 19]. Available for download from: https://www.oregon.gov/oha/OHPB/CCODocuments/CCO-2.0-DSN-Provider-Capacity-Report-Protocol.docx [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrilla CHA, Patterson DG, Garberson LA, Coulthard C, Larson EH. Geographic variation in the supply of selected behavioral health providers. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(6, Suppl 3):S199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chu RC, Peters C, De Lew N, Sommers BD. State Medicaid telehealth policies before and during the COVID-19 public health emergency [Internet]. Washington (DC): Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2021. Jul [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: https://www.aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2021-07/medicaid-telehealth-brief.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu JM, Myers R, McConnell KJ, Levander X, Lin SC. Trends in outpatient mental health services use before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(4):573–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 28.Rowan K, McAlpine DD, Blewett LA. Access and cost barriers to mental health care, by insurance status, 1999–2010. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(10):1723–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walker ER, Cummings JR, Hockenberry JM, Druss BG. Insurance status, use of mental health services, and unmet need for mental health care in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(6):578–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Adults reporting unmet need for mental health treatment in the past year [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): KFF; 2021. [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/adults-reporting-unmet-need-for-mental-health-treatment-in-the-past-year/ [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludomirsky AB, Schpero WL, Wallace J, Lollo A, Bernheim S, Ross JS, et al. In Medicaid managed care networks, care is highly concentrated among a small percentage of physicians. Health Aff (Millwood). 2022;41(5):760–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McConnell KJ, Charlesworth CJ, Zhu JM, Meath THA, George RM, Davis MM, et al. Access to primary, mental health, and specialty care: a comparison of Medicaid and commercially insured populations in Oregon. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(1):247–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Thomas KC, Morrissey JP. County-level estimates of mental health professional supply in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):1315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Health Resources and Services Administration. State-level projections of supply and demand for behavioral health occupations: 2016–2030 [Internet]. Rockville (MD): HRSA; 2018. Sep [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-health-workforce/data-research/state-level-estimates-report-2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benson NM, Myong C, Newhouse JP, Fung V, Hsu J. Psychiatrist participation in private health insurance markets: paucity in the land of plenty. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(12):1232–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukui S, Rollins AL, Salyers MP. Characteristics and job stressors associated with turnover and turnover intention among community mental health providers. Psychiatr Serv. 2020;71(3):289–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brabson LA, Harris JL, Lindhiem O, Herschell AD. Workforce turnover in community behavioral health agencies in the USA: a systematic review with recommendations. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2020;23(3):297–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGuire TG. Achieving mental health care parity might require changes in payments and competition. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016; 35(6):1029–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Mental Health Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) [Internet]. San Francisco (CA): KFF; 2020. [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/mental-health-care-health-professional-shortage-areas-hpsas/ [Google Scholar]

- 40.Council for Affordable Quality Healthcare. The hidden causes of inaccurate provider directories [Internet]. Washington (DC): CAQH; 2019. [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: https://www.caqh.org/sites/default/files/explorations/CAQH-hidden-causes-provider-directories-whitepaper.pdf

- 41.Bauer MS, Leader D, Un H, Lai Z, Kilbourne AM. Primary care and behavioral health practice size: the challenge for health care reform. Med Care. 2012;50(10):843–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu JM, Breslau J, McConnell KJ. Medicaid managed care network adequacy standards for mental health care access: balancing flexibility and accountability. JAMA Health Forum. 2021;2(5):e210280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhu JM, Polsky D, Johnstone C, McConnell KJ. Variation in network adequacy standards in Medicaid managed care. Am J Manag Care. 2022;28(6):294–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haeder SF, Weimer DL, Mukamel DB. Mixed signals: the inadequacy of provider-per-enrollee ratios for assessing network adequacy in California (and elsewhere). World Medical and Health Policy [serial on the Internet]. 2021. Jul 21 [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/wmh3.466

- 45.Keith K New guidance on transparency requirements, advanced explanations of benefits, and more. Health Affairs Blog [blog on the Internet]. 2021. Aug 25 [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/forefront.20210825.604994/full/

- 46.Burman A, Haeder SF. Without a dedicated enforcement mechanism, new federal protections are unlikely to improve provider directory accuracy. Health Affairs Blog [blog on the Internet]. 2021. Nov 5 [cited 2022 May 19]. Available from: 10.1377/forefront.20211102.706419/full/ [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.