Abstract

Background:

Concerns have been raised regarding the impact of time restricted eating (TRE) on sex hormones in women. This study examined how TRE affects sex steroids in premenopausal and postmenopausal women.

Methods:

This is a secondary analysis of an 8-week TRE study (4–6 h eating window) conducted in adults with obesity. Men and perimenopausal women were excluded. Females were classified into two groups based on menstrual status: premenopausal (n = 12), or postmenopausal (n = 11).

Results:

After 8 weeks, body weight decreased in premenopausal women (−3 ± 2%) and postmenopausal women (−4 ± 2%) (main effect of time, P < 0.001), with no difference between groups (no group × time interaction). Circulating levels of testosterone, androstenedione, SHBG did not change in either group (no group × time interaction). DHEA concentrations decreased (P < 0.05) in premenopausal (−14 ± 32%) and postmenopausal women (−13 ± 34%; main effect of time, P = 0.03), with no difference between groups. Estradiol, estrone, and progesterone were only measured in postmenopausal women, and remained unchanged.

Conclusion:

In premenopausal women, androgens and SHBG remained unchanged, while DHEA decreased, during TRE. In postmenopausal women, estrogens, progesterone, androgens, and SHBG did not change, but DHEA was reduced.

Keywords: Intermittent fasting, time restricted eating, female sex hormones, premenopausal, postmenopausal, obesity, weight loss

Introduction

Time restricted eating (TRE) is a form of intermittent fasting that involves eating all food within a specified window (4 to 10 h) and consuming no other food or beverages, with the exception of water, for the rest of the day. The health benefits of TRE in adults with obesity generally include weight loss (1) and improvements in blood pressure and glycemic control (2, 3). However, concerns have been raised regarding the effects of TRE on female hormone metrics. It is understandable that many women are skeptical about starting TRE because it may negatively affect levels of estrogen and other hormones, leading to menstrual cycle irregularities and fertility issues. These concerns largely stem from one rodent study (4). In this study (4), young lean rats underwent 24 h of fasting every other day (only water was consumed during the fasting period). After 12 weeks, serum estradiol increased, LH levels decreased, and disruptions in estrous cyclicity (menstrual cycle) were observed, versus ad libitum fed controls. While these findings are indeed concerning, the female rats were very young (i.e. 3 months old), which corresponds to a human aged 9 years old (5). TRE is not recommended for children under the age of 12 since it has the potential to negatively impact growth (3). Thus, data from this animal study (4), though valuable to the field, does not provide evidence for how fasting may impact sex steroid levels in adult human females.

Unfortunately, human trials examining how intermittent fasting impacts hormonal profile in adult women are very limited (6, 7). Evidence from two clinical trials suggest that TRE and the 5:2 diet (fasting 2 days per week) have little effect on key reproductive hormones in young women (6, 7). However, these findings are limited in that only premenopausal women were assessed. No study to date has examined how TRE, or any other form intermittent fasting, impacts sex hormone levels in postmenopausal women.

In view of these gaps in the literature, we conducted this study to examine how TRE impacts sex hormone levels in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women with obesity. In premenopausal women, we hypothesized that concentrations of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), androstenedione, testosterone, and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) would not change with short-term TRE. Estradiol, estrone, and progesterone were not measured in premenopausal women because the day of each woman’s menstrual cycle was not recorded at time of blood collection in the original study. In postmenopausal women, we hypothesized that concentrations of estradiol, estrone, progesterone, DHEA, androstenedione, testosterone, and SHBG would not change with short-term TRE.

Methods

Subject selection

This study is a secondary analysis of a previously published 8-week trial that examined the effect of 4–6 h TRE on metabolic health in adults in with obesity (8). The experimental protocol was approved by the University of Illinois Chicago Office for the Protection of Research Subjects, and all subjects provided written informed consent. The full protocol has been published previously (8). Briefly, subjects were included if they were female or male; 18–65 years old; BMI 30.0–49.9 kg/m2, and excluded if they had a history of diabetes, were not weight stable, were pregnant, lactating, or smokers. Perimenopausal women (defined as having irregular menses, with differences on cycle length over seven days or amenorrhea until one year) were excluded from the original study (9). For the present analysis, we combined completers from the 4-h TRE group (n = 16) and the 6-h TRE group (n = 19) into one group (n = 35). The male participants were removed (n = 3), leaving a total sample of n = 32. Women were then classified in two groups based on self-reported menstruation pattern (10): premenopausal (regular menses; n = 13), or postmenopausal (absence of menses for over one year; n = 19). Of these subjects, only n = 12 premenopausal women and n = 11 postmenopausal women had enough stored blood samples, so only these women were included in this study.

Time restricted eating protocol

The 4-h TRE group ate ad libitum from 3–7pm each day (4-h eating window) and fasted from 7–3 pm (20-h fasting window). The 6-h TRE group ate ad libitum from 1–7 pm daily (6-h eating window) and fasted from 7–1 pm (18-h fasting window). During the eating window, participants were allowed to eat food as desired. During the fasting window, subjects were instructed to consume only water and energy-free beverages.

Body weight, body composition, diet adherence and physical activity

All outcomes were measured at baseline (pre-intervention) and at week 8. Body weight measurements were taken with subjects wearing light clothing and without shoes using a digital scale (HealthoMeter) at the research center. Fat mass, lean mass, and visceral fat mass were measured by dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA; iDXA, GE). Adherence to the TRE protocol was quantified using a daily adherence log, as described previously (8). Changes in physical activity (steps/d) were assessed over 7 days by a pedometer (Fitbit Alta).

Sex hormone concentrations

Twelve-hour fasting blood samples were collected between 6–9 am. The subjects were instructed to avoid exercise, alcohol, and coffee for 24 h before each visit. Circulating concentrations of total testosterone, androstenedione, SHBG, DHEA, estradiol, estrone, and progesterone were measured by ELISA in duplicate (Alpco). Estradiol, estrone, and progesterone levels were not measured in premenopausal women is since levels of these hormones change over the course of the menstrual cycle, and the day of each women’s cycle was not recorded in the original study.

Statistical analyses

At baseline, differences between premenopausal versus postmenopausal women were tested by an independent samples t-test (continuous variables) or McNemar test (categorical variables). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA with groups (premenopausal women and postmenopausal women) as the between-subject factor and time (baseline and week 8) as the within-subject factor was used to compare changes in dependent variables between the groups over time. When there was a significant main effect but no interaction, post hoc comparisons were performed using Bonferroni’s correction to determine differences between group means. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05. All data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 27, SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

Baseline characteristics

There were no significant differences between the two groups of women at baseline for race, body weight, fat mass, lean mass, height, BMI, or physical activity level (Table 1). However, postmenopausal women were significantly (P < 0.001) older and had greater (P = 0.04) visceral fat mass versus premenopausal women.

Table 1.

Changes in body weight and body composition in premenopausal and postmenopausal women after 8 weeks of time restricted eating

| Variables | Premenopausal women | Postmenopausal women | P-value | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Week 8 | Change | Baseline | Week 8 | Change | Group | Time | Group × Time | |

| n | 12 | 11 | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| Age (y) | 40 ± 8 | 55 ± 4* | -- | -- | -- | ||||

| Race or ethnic group | |||||||||

| White | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Black | 8 | 10 | |||||||

| Asian | 2 | 0 | |||||||

| Hispanic | 1 | 0 | |||||||

| Body composition | |||||||||

| Body weight (kg) | 97 ± 17 | 94 ± 16 | −3 ± 2 | 104 ± 20 | 100 ± 19 | −4 ± 2 | 0.49 | < 0.001 | 0.78 |

| Fat mass (kg) | 48 ± 8 | 46 ± 8 | −2 ± 1 | 51 ± 13 | 48 ± 13 | −3 ± 2 | 0.58 | 0.01 | 1.00 |

| Lean mass (kg) | 51 ± 8 | 50 ± 8 | −1 ± 1 | 50 ± 7 | 49 ± 6 | −1 ± 1 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.74 |

| Visceral fat (kg) | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.0 ± 0.3 | −0.1 ± 0.1 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | −0.2 ± 0.3 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Height (cm) | 164 ± 8 | 164 ± 8 | 0 ± 0 | 164 ± 8 | 164 ± 8 | 0 ± 0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 36 ± 5 | 35 ± 5 | −1 ± 1 | 38 ± 5 | 37 ± 5 | −1 ± 1 | 0.42 | < 0.001 | 0.82 |

| Adherence and activity | |||||||||

| Adherence (days/week) | 6.3 ± 0.5 | 6.2 ± 0.7 | |||||||

| Physical activity (steps/d) | 5926 ± 3412 | 6026 ± 3023 | 100 ± 2506 | 8318 ± 3401 | 7756 ± 2940 | −562 ± 2269 | 0.26 | 0.58 | 0.23 |

Values are expressed as means ± SD P-value: Two-way repeated measures ANOVA with groups (premenopausal women and postmenopausal women) as the between subject factor and time (baseline and week 8) as the within-subject factor.

Significantly different in postmenopausal vs. premenopausal women (Independent samples t-test.

Body weight, body composition, diet adherence and physical activity

Body weight significantly decreased in both groups of women by week 8 (main effect of time, P < 0.001), with no differences between groups (Table 1). Premenopausal and postmenopausal women lost 3 ± 2% and 4 ± 2% of their body weights, respectively. Fat mass and lean mass significantly decreased by week 8 for premenopausal and postmenopausal women (main effect of time, P = 0.01 for both comparisons), with no differences between groups. Visceral fat mass decreased to a greater extent in postmenopausal women when compared to premenopausal women (group × time interaction, P = 0.04). BMI significantly decreased in both groups of women over time (main effect of time, P < 0.001). Adherence to the TRE intervention was high in both groups, and physical activity level did not change over the course of the trial.

Sex hormone levels

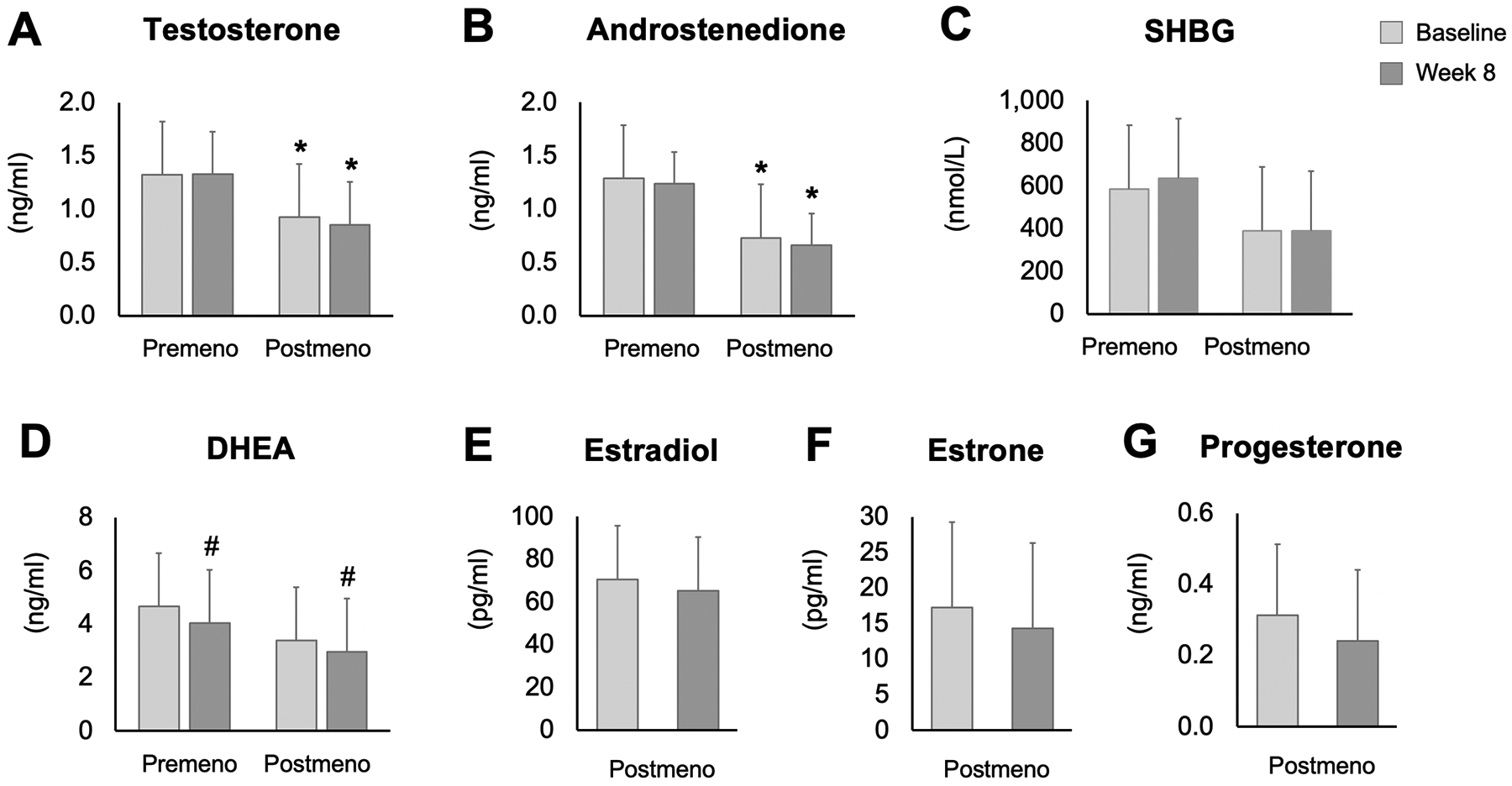

Testosterone and androstenedione concentrations were significantly lower in postmenopausal versus premenopausal women at baseline and week 8 (main effect of group, P = 0.04), and did not change by week 8 in either group of women (Figure 1). SHBG concentrations did not differ between premenopausal and postmenopausal women at baseline and remained unchanged by end of the study. DHEA levels did not differ between the groups of women at baseline. However, after 8 weeks of intervention, DHEA concentrations decreased significantly in both premenopausal (−14 ± 32%) and postmenopausal women (−13 ± 34%; main effect of time, P = 0.03), with no differences between groups. Estradiol, estrone, and progesterone were only measured in postmenopausal women, and did not change from baseline to week 8 of the trial.

Figure 1. Changes in sex hormone levels in premenopausal and postmenopausal women after 8 weeks of time restricted eating.

Values are expressed as means ± SD. SHBG: Sex hormone binding globulin; DHEA: Dehydroepiandrosterone. P-value: Two-way repeated measures ANOVA with groups (premenopausal women and postmenopausal women) as the between subject factor and time (baseline and week 8) as the within-subject factor * Significantly different in postmenopausal versus premenopausal women (main effect of group, P < 0.05). # Significantly different from baseline to week 8 in both groups of women (main effect of time, P < 0.05).

Discussion

The goal of this secondary analysis was to examine how TRE impacts sex hormone levels in women with obesity. Our data suggest that concentrations of testosterone, androstenedione, and SHBG do not change during 8-weeks of TRE in premenopausal or postmenopausal women with 3–4% weight loss. Estradiol, estrone, and progesterone, were only measured in postmenopausal women, and remained unchanged. DHEA, on the other hand, decreased in both groups of women by the end of the trial.

Obesity is linked with higher circulating concentrations of estrogens and androgens, and lower levels of SHBG in both premenopausal and postmenopausal females (11). Weight loss has been shown, though not consistently, to reduce serum concentrations of estradiol (12, 13) and testosterone (13, 14), while increasing SHBG (12, 13, 15, 16). Sex steroid concentrations generally improve with 5–10% weight loss and at least 3 months of lifestyle therapy (12, 13, 14). Maintenance of weight loss for up to 18 months sustains improvements in these circulating sex steroids (17, 18).

Only two studies to date have examined how fasting impacts sex steroid levels in women (6, 7). In a study by Harvie et al (6), levels of testosterone, androstenedione, and prolactin did not change after 24-weeks of the 5:2 diet (2 days of 500 kcal, 5 day of ad libitum eating) in premenopausal women, despite 7% weight loss. Similarly, Li et al (7) observed no change in luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), or testosterone, after 5 weeks of 8-h TRE in premenopausal women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), despite 2% weight loss. In the present study, we also observed no change in testosterone, androstenedione, and SHBG (premenopausal and postmenopausal women) and estrogens (postmenopausal only) with 3–4% weight loss. Taken together, the degree of weight loss achieved with these fasting regimens may not be large enough to modulate these sex steroids in women.

The only hormone that was significantly decreased in our study was DHEA. Reductions in DHEA were demonstrated in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women after 8 weeks of TRE. DHEA is the most abundant steroid hormone in adult women and is mainly produced in the adrenal cortex and ovaries (19, 20). DHEA is a precursor for sex steroids and accounts for ~75% of estrogens formed in premenopausal women (21). Reductions in DHEA may be advantageous in premenopausal women with obesity as they can translate into greater reductions in breast cancer risk (22, 23). However, among postmenopausal women, adrenal DHEA becomes one of the major precursors of estrogens and androgens. A decrease in DHEA among postmenopausal woman can induce sexual dysfunction (24), diminished skin tone (25), and vaginal dryness (26). Although DHEA values decreased in the present study, they were still within the normal range for both premenopausal women (1.12–7.43 ng/ml) and postmenopausal women (0.6–5.7 ng/ml) (27). In view of this, it is possible that the reductions in DHEA in postmenopausal women did not translate into any unfavorable clinical manifestations. However, this would need to be confirmed by a study that directly assesses these outcomes.

Our study is limited in that the sample size was small (n = 23), the intervention was short (8-weeks), and peri-menopausal women were excluded. In addition, certain key hormones (estradiol, estrone, and progesterone) were not measured in premenopausal women since the day of the cycle was not recorded at time of blood collection. This greatly limits our ability to ascertain how TRE impacts reproductive health of younger women. We were also unable to elucidate whether TRE, in the absence of weight loss, has any impact on female sex hormones. These important questions warrant further investigation.

In summary, this secondary analysis suggests that short-term TRE, which produces minimal weight loss (3–4%), has little effect on sex steroid levels in premenopausal or postmenopausal women with obesity. These findings will undoubtedly require confirmation by well-powered RCT that specifically examines the effect of TRE on the hormonal profile of women of various ages.

Importance questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Concerns have been raised regarding the effects of time restricted eating (TRE) on female sex hormone levels.

Unfortunately, human trials examining how intermittent fasting impacts sex steroids in adult women with obesity are very limited.

Accordingly, this study examined how TRE affects sex hormone levels in premenopausal and postmenopausal women.

What are the new findings in your manuscript?

Our data suggest that concentrations of testosterone, androstenedione, and sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) do not change during 8-weeks of TRE in premenopausal or postmenopausal women, with 3–4% weight loss.

Estradiol, estrone, and progesterone, were only measured in postmenopausal women, and remained unchanged.

Dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), on the other hand, decreased in both groups of women by the end of the trial.

How might your results change the direction of research or the focus of clinical practice?

These preliminary data suggest that short-term TRE, that produces mild weight loss, has little effect on sex hormone levels in premenopausal or postmenopausal women.

These findings still require confirmation by well-powered RCT that specifically examines the effect of TRE on sex steroids of women of various ages.

Funding:

National Institutes of Health, NIDDK, R01DK119783

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Trial registration: Clinicaltrials.gov NCT03867773

References

- 1.Patikorn C, Roubal K, Veettil SK, Chandran V, Pham T, Lee YY, et al. Intermittent Fasting and Obesity-Related Health Outcomes: An Umbrella Review of Meta-analyses of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4: e2139558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patterson RE, Sears DD. Metabolic Effects of Intermittent Fasting. Annu Rev Nutr 2017;37: 371–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varady KA, Cienfuegos S, Ezpeleta M, Gabel K. Clinical application of intermittent fasting for weight loss: progress and future directions. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumar S, Kaur G. Intermittent fasting dietary restriction regimen negatively influences reproduction in young rats: a study of hypothalamo-hypophysial-gonadal axis. PLoS One 2013;8: e52416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sengupta P The Laboratory Rat: Relating Its Age With Human’s. Int J Prev Med 2013;4: 624–630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harvie MN, Pegington M, Mattson MP, Frystyk J, Dillon B, Evans G, et al. The effects of intermittent or continuous energy restriction on weight loss and metabolic disease risk markers: a randomized trial in young overweight women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2011;35: 714–727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li C, Xing C, Zhang J, Zhao H, Shi W, He B. Eight-hour time-restricted feeding improves endocrine and metabolic profiles in women with anovulatory polycystic ovary syndrome. J Transl Med 2021;19: 148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cienfuegos S, Gabel K, Kalam F, Ezpeleta M, Wiseman E, Pavlou V, et al. Effects of 4- and 6-h Time-Restricted Feeding on Weight and Cardiometabolic Health: A Randomized Controlled Trial in Adults with Obesity. Cell Metab 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Solomon CG, Hu FB, Dunaif A, Rich-Edwards J, Willett WC, Hunter DJ, et al. Long or highly irregular menstrual cycles as a marker for risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2001;286: 2421–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, Lobo R, Maki P, Rebar RW, et al. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97: 1159–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leeners B, Geary N, Tobler PN, Asarian L. Ovarian hormones and obesity. Hum Reprod Update 2017;23: 300–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedenreich CM, Woolcott CG, McTiernan A, Ballard-Barbash R, Brant RF, Stanczyk FZ, et al. Alberta physical activity and breast cancer prevention trial: sex hormone changes in a year-long exercise intervention among postmenopausal women. J Clin Oncol 2010;28: 1458–1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Campbell KL, Foster-Schubert KE, Alfano CM, Wang CC, Wang CY, Duggan CR, et al. Reduced-calorie dietary weight loss, exercise, and sex hormones in postmenopausal women: randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2012;30: 2314–2326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Monninkhof EM, Velthuis MJ, Peeters PH, Twisk JW, Schuit AJ. Effect of exercise on postmenopausal sex hormone levels and role of body fat: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2009;27: 4492–4499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aubuchon M, Liu Y, Petroski GF, Thomas TR, Polotsky AJ. The impact of supervised weight loss and intentional weight regain on sex hormone binding globulin and testosterone in premenopausal women. Syst Biol Reprod Med 2016;62: 283–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wildman RP, Tepper PG, Crawford S, Finkelstein JS, Sutton-Tyrrell K, Thurston RC, et al. Do changes in sex steroid hormones precede or follow increases in body weight during the menopause transition? Results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012;97: E1695–1704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stolzenberg-Solomon RZ, Falk RT, Stanczyk F, Hoover RN, Appel LJ, Ard JD, et al. Sex hormone changes during weight loss and maintenance in overweight and obese postmenopausal African-American and non-African-American women. Breast Cancer Res 2012;14: R141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duggan C, Tapsoba JD, Stanczyk F, Wang CY, Schubert KF, McTiernan A. Long-term weight loss maintenance, sex steroid hormones, and sex hormone-binding globulin. Menopause 2019;26: 417–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis SR, Panjari M, Stanczyk FZ. Clinical review: DHEA replacement for postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2011;96: 1642–1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang J, Chen LR, Chen KH. The Utilization of Dehydroepiandrosterone as a Sexual Hormone Precursor in Premenopausal and Postmenopausal Women: An Overview. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2021;15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maggio M, De Vita F, Fisichella A, Colizzi E, Provenzano S, Lauretani F, et al. DHEA and cognitive function in the elderly. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2015;145: 281–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tworoger SS, Missmer SA, Eliassen AH, Spiegelman D, Folkerd E, Dowsett M, et al. The association of plasma DHEA and DHEA sulfate with breast cancer risk in predominantly premenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15: 967–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Endogenous H, Breast Cancer Collaborative G, Key TJ, Appleby PN, Reeves GK, Travis RC, et al. Sex hormones and risk of breast cancer in premenopausal women: a collaborative reanalysis of individual participant data from seven prospective studies. Lancet Oncol 2013;14: 1009–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maseroli E, Vignozzi L. Are Endogenous Androgens Linked to Female Sexual Function? A Systemic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Sex Med 2022;19: 553–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makrantonaki E, Schonknecht P, Hossini AM, Kaiser E, Katsouli MM, Adjaye J, et al. Skin and brain age together: The role of hormones in the ageing process. Exp Gerontol 2010;45: 801–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marino JM. Genitourinary Syndrome of Menopause. J Midwifery Womens Health 2021;66: 729–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Samaras N, Samaras D, Frangos E, Forster A, Philippe J. A review of age-related dehydroepiandrosterone decline and its association with well-known geriatric syndromes: is treatment beneficial? Rejuvenation Res 2013;16: 285–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]